Abstract

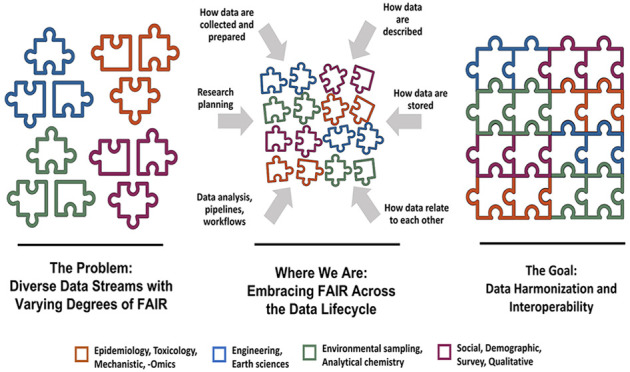

Environmental health sciences (EHS) span many diverse disciplines. Within the EHS community, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program (SRP) funds multidisciplinary research aimed to address pressing and complex issues on how people are exposed to hazardous substances and their related health consequences with the goal of identifying strategies to reduce exposures and protect human health. While disentangling the interrelationships that contribute to environmental exposures and their effects on human health over the course of life remains difficult, advances in data science and data sharing offer a path forward to explore data across disciplines to reveal new insights. Multidisciplinary SRP-funded teams are well-positioned to examine how to best integrate EHS data across diverse research domains to address multifaceted environmental health problems. As such, SRP supported collaborative research projects designed to foster and enhance the interoperability and reuse of diverse and complex data streams. This perspective synthesizes those experiences as a landscape view of the challenges identified while working to increase the FAIR-ness (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) of EHS data and opportunities to address them.

Keywords: Data Integration, FAIR, Environmental Health Sciences, Superfund Research Program, Data Interoperability

Short abstract

Enhancing data interoperability and reuse can accelerate the pace of environmental health sciences research to reveal new insight into protect human health.

Introduction

Environmental health sciences (EHS) span wide-ranging disciplines, including earth sciences, environmental engineering, chemistry, exposure science, biology, toxicology, and epidemiology. Within the EHS community, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program (SRP) was established to meet the mandates of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986. These mandates focus on understanding exposure to hazardous substances and their interactions within the body, and designing and implementing strategies to reduce harmful exposures and protect human health.1

To address these broad, cross-cutting mandates, the NIEHS SRP funds multidisciplinary university-based research centers to disentangle the multifaceted issues related to human and environmental health. For example, SRP grantees strive to understand factors that control how chemicals move and change in the environment and conditions that affect their mobility. They study biotransformation and factors that influence the bioavailability and potential toxicity of these substances. SRP-funded researchers explore the intricate networks of biological mechanisms involved in environmentally induced disease and how exposure to mixtures of contaminants or other stressors may act together to affect health. They also explore critical windows of exposure that may affect susceptibility to environmental exposures and disease throughout life.

While SRP-supported researchers strive to identify solutions to environmental health problems, addressing these challenges is equally complex. For example, to design effective strategies to reduce exposures, researchers must have a detailed understanding of when and how people are exposed to hazardous substances. Similarly, intricate relationships within the human body as a function of age, sex, and the amount of exposure over the lifetime play a role when designing targeted therapies to prevent or treat disease.2 SRP-funded researchers also shed light on the connections between geochemistry, hydrology, meteorology, and microbial biology that affect the use of biological and chemical remediation approaches, providing foundational knowledge and tools to improve strategies to reduce exposures and clean up contaminants in the environment.3

To solve complex environmental health problems, SRP grantees must integrate research across many EHS scientific domains and find new and effective strategies for collaborating and sharing data across disciplines to understand deeper relationships within the larger system.4 This strategy can identify innovative solutions to environmental health problems and open new opportunities to maximize previous and future research investments while advancing science more rapidly and in new areas not previously possible.

Sharing knowledge and data across disciplines, or even across research teams in the same discipline, is not yet common practice, and it is not without significant hurdles. Since SRP-funded centers work in multidisciplinary teams with research spanning many fields under the umbrella of EHS; they are well-positioned to explore how to best integrate data from diverse research domains to address complex environmental health problems.5

In anticipation of the implementation of the NIH Data Management and Sharing Policy,6 SRP supported collaborative projects to foster sharing and reuse of SRP data while clarifying potential challenges. The projects were designed to explore previously unanswerable research questions by combining two or more existing data sets, taking advantage of available ontologies and computational tools when appropriate. From leveraging data across human populations to integrating data across model organisms and sharing environmental microbiome data, each project required key partnerships between subject matter and data science experts.

Collectively, these projects utilized more than 50 data sets from SRP-funded researchers, external collaborators, and state, local, and federal sources, including information on contaminants in environmental and biological samples, health outcomes in populations, changes in genes and proteins, historical land uses and flooding, and more. Detailed descriptions of each of the collaborative team projects, including approaches, outcomes, and lessons learned, can be found in the White Paper “Enhancing the Integration, Interoperability, and Reuse of SRP-Generated Data Through External Use Cases”7 (see Supporting Information Table S-1).

As a microcosm of EHS, we present SRP as a useful case study in identifying barriers and potential solutions for data sharing and integration for the broader community. These projects included researchers who had not previously considered data integration and those already working closely with data scientists, offering wide-ranging perspectives and experiences trying to combine data.

By synthesizing the experiences of these projects, we gained a better programmatic understanding of the data sharing landscape and practical insight into future needs. The purpose of this perspective is to discuss those experiences and place them within the context of the EHS field at large. We further show how challenges identified by SRP scientists throughout the data lifecycle are not isolated, but representative of the wider EHS community.

Why FAIR?

The rapid growth in data volume, variety, and complexity are driving the need for a robust culture of data sharing and open science, which are steadily becoming more mainstream.13,14 This shift will allow researchers to better leverage advances in data science and accelerate the pace of research. By integrating and analyzing data sets across disciplines, new information can be revealed and new solutions identified that were not envisioned when focusing on a narrow research topic.8−12 To harness this potential, more emphasis is needed on understanding how to maximize the reuse of existing scientific data while also adapting how new research is designed and conducted to ensure data is collected with sharing in mind.

The FAIR Data Principles, which suggest data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, emphasize robust data management to support integration and scientific discovery.15 While these principles are becoming more widely adopted, SRP collaborative projects identified many barriers to making data FAIR and to facilitating broader data integration and sharing throughout the entire data lifecycle. Their experiences reflect commonalities with other institutions and initiatives from across a variety of disciplines who have recognized the value of the FAIR principles and sought to implement them—discovering and clarifying the associated barriers along the way—including immunology,16 plant sciences,17 medical research,18 chemistry,19 geosciences,20 computational toxicology,21,22 psychology,23 genomics,24 ecology,25 and human disease.26

What We Learned: Challenges and Recommendations

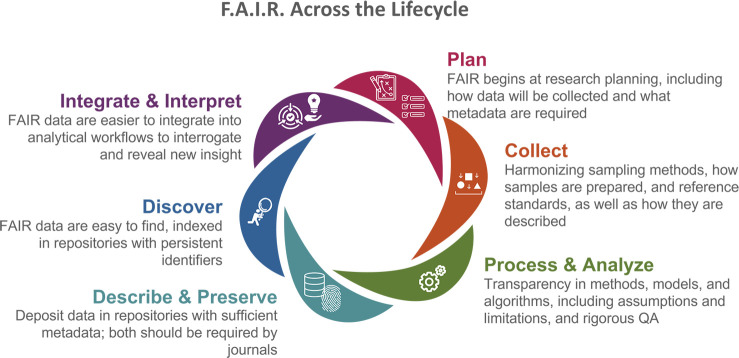

Integrating and reusing data generated from individual research projects, within SRP and across EHS, requires harmonizing data workflows, ensuring consistent and robust practices in data stewardship, and embracing the FAIR principles. This should occur during all phases of the research process, from study planning, data collection, storing, processing, and analysis, through dissemination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

FAIR data principles begin with research planning and extend throughout the data lifecycle to dissemination, sharing, and reuse. Different collaborative teams identified barriers within each of these steps and developed strategies to overcome these challenges (see Table S-1).

How Data Are Collected: Research Planning and Standards

Research planning is critical to setting data up to be FAIR at the outset. This includes an informed strategy about what data and metadata to collect, how it will be collected and described, and approaches for assessing its quality and its management. Like the problem formulation stage used in developing a research study and in the practice of risk assessment,27 investing time and energy in planning up front reduces the need to work backward later. Bringing together diverse perspectives from different subject matter experts and data scientists makes sure the right scientific questions are being asked and appropriate data are being collected, using standardized terms that are consistent and defined, and that all parties understand how the data will be used and analyzed.

Within this realm is the need for researchers to develop more standardized methods for collecting and preparing samples and robust reference standards to enable more direct comparisons across data sets generated by different researchers. This should occur prior to data acquisition and analysis.

Another key aspect of FAIR centers on interoperability, which refers to the harmonization of data structure, formatting, and annotation. Research across domains may be at different stages of readiness for interoperability. For example, due to vested interest within the research community and guiding policies, genomics research, which produces vast quantities of data on genes and their expression, has in many ways set the standard for data sharing and interoperability by utilizing standard data formats.24,28−38 Other fields, such as targeted and untargeted chemical analyses that may use differing instruments, techniques, tools, and data formats, have additional hurdles to overcome to close the gap.39 SRP-funded researchers experienced the variation in readiness for data interoperability firsthand.7 According to the teams, promoting the use of open data formats and analysis tools is one potential solution for preserving data sustainably.

How Data Are Described: Metadata

For data to be usable across disciplines and reusable for other purposes, they must be clearly described. Key information needs to be reported on data collection methods, lab protocols, and data formats. The collaborative projects discovered the importance of robust metadata, fundamental for sharing data across research areas, and a key tool for researchers to replicate data findings. Descriptive metadata provides crucial contextual information, such as versions of software used and statistical approaches, and enables proper reuse. Conversely, inconsistent metadata standards and requirements can hinder efficient sharing, integration, and reuse.

Since machine-readable metadata are essential for machine discoverability of data sets and services, standardized and descriptive metadata are an essential component of increasing data FAIR-ness. Similarly, working backward to reconvert or reannotate data for integration is time-consuming, complex, and often not feasible.7

EHS researchers from different science areas have discussed strategies to standardize the information that is reported for specific types of studies, such as minimum information guidelines or common data elements.40−44 However, broad collaboration among investigators in each field is necessary to agree on those standards, how best to balance utility without placing undue burden, and how to disseminate these standards. Researchers should also engage with repositories and journals that are responsible for data sharing to ensure necessary metadata is required to enable interoperability and reuse.

How Data Relate to Each Other: Ontologies and Knowledge Graphs

Ontologies can facilitate data integration by standardizing the vocabulary used to describe different entities and relationships between them. However, some researchers may not know that these exist, how to find or select the most appropriate ontology, or how to use them. Each area of science may have their own vocabularies, and more specific subdisciplines may lack or have incomplete vocabularies, further complicating their use. When working across disciplines, and therefore vocabularies, term conflicts create a significant hurdle for researchers not familiar with the process of adding and defining terms to ontologies. Even discrete communities within the same scientific discipline may format and describe data differently, pointing to the need for standardizing these processes to integrate data streams. This need has long been recognized45 and remains critical to advancing data sharing and interoperability.46,47

Through their collaborations, SRP teams identified that researchers should work together to standardize terminologies and improve and expand existing ontologies to keep pace with the evolution and complexity of research. For example, on the exposure science side, groups are working to develop aligned terminology to support comparison and interpretation of exposure information that can be used, among other things, to better inform the application of regulatory guidelines across continents.48 Similarly, a new collaborative initiative advancing community development and application of a harmonized language for describing research within EHS is underway.45,49

In parallel to ontologies, the knowledge graph is used to represent a collection of interlinked descriptions of entities that puts data in context while providing a framework for data integration, unification, analysis, and sharing. This approach has been used in other fields, such as for biological networks,50 human environmental health,51,52 and chemical structures.53 This has also been proposed as an intuitive and scalable solution for representing the interconnected complexities of environmental health research and may offer a useful tool for identifying trends and generating new knowledge to inform decision making that protects human health.51,54

More conversations across disciplines will be necessary to move forward with knowledge graphs for EHS that incorporate the temporality of exposures, nonchemical stressors (e.g., psychosocial stress) and other social determinants of health, and how they interplay with biological response. With input from an engaged community, these tools will become more refined and representative of the many areas of science involved in EHS and better capture and visualize the diverse variables involved while helping to uncover the relationships between them and the factors that affect them.

How Data Are Stored: Repositories

Some data types lack existing repositories that are specific to their scientific domain. In these cases, researchers must use generalist repositories that may not collect all the metadata necessary for reusing data or reproducing findings later. While these repositories are incredibly useful, some collaborative teams suggested these resources could be better leveraged if they facilitated unsupervised methods to compile raw data or integrated widgets to allow users to toggle between domain-specific repositories.7 These features may make generalist repositories more powerful to facilitate scientific discovery.

Another consideration is storing and sharing raw versus processed data. While raw data is preferred for reuse and reprocessing, it is large in volume. Researchers and repositories need to consider the balance of data space and what raw data needs to be shared versus made available by request. One solution may be a hierarchical database model for repositories to store raw data more efficiently.

Other issues may be unique to specific data types, and researchers should consider the best strategies for sharing their data. For example, raw image data is quite large and cumbersome to store. Making image files available by request may be useful until repositories capable of storing large image files are more widely available. In these cases, sharing metadata files can let others know the data are available. In situations where data are restricted for security purposes (e.g., personally identifiable information) the metadata would include information about how the data can be accessed and what permissions are needed so researchers may still be able to share some human data through restricted and secure access.

Finally, another overarching challenge for repositories is to ensure these resources continue to evolve to provide value to the scientific community in a way that is sustainable. This requires an active dialogue between researchers as data generators, repositories as data facilitators, and data users. Repositories, researchers utilizing them, and the journals that publish the data should be aware of each other’s technical requirements and how they can be met in a way that considers the needs of data users. Together, these conversations can enable rigor and reproducibility while enhancing the ability to advance scientific questions by integrating and reusing data. This coordination will be instrumental in developing strategies to improve data collection at the outset, a key step in helping to minimize the burden and cost of data curation while maximizing the potential for data reuse.

How Data Are Analyzed and Combined: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) approaches, which automate analyses by making inferences from data and identifying patterns without explicit programming by humans, are providing new opportunities to integrate and analyze large volumes of data. Embracing the FAIR principles makes data more machine-readable, so it can be leveraged for AI/ML and prediction. This will open new doors in characterizing sources of pollution, estimating all exposures across the lifespan, and predicting chemical toxicities, all critical in the context of the vast universe of chemical exposures which currently bog down regulatory decision making.55,56

For example, researchers are leveraging advances in ML to identify biomarkers from cell-based assays that link chemical exposures to the risk of developing diseases more efficiently and effectively, reducing the need for expensive and time-consuming animal or in vivo studies.57

The promise of the advances AI and ML can make is exciting. However, an important limitation is that these tools are only as good as the data they are based on—throughout the entire data lifecycle—the models created to utilize them, and researcher’s understanding of how to select and apply them and interpret their results. Algorithms developed for ML are sometimes not well understood by those using them, which can lead to incorrect or unintentionally biased results.55,56 Underlying data should be independently and critically evaluated.

Just as important to rigor and reproducibility is the need for transparency that describes how AI systems were developed, as well as their assumptions and limitations. To avoid compounding error or bias, insight revealed by these tools should be validated through research findings and include data from more diverse populations and studies.56 These essential principles underpin the ethical application of AI/ML tools.

There is a critical need for collective emphasis on developing robust frameworks for how data will be used, as well as on data curation and storage, scientific computing, and robust training to equip nondata science savvy researchers to apply AI/ML approaches correctly and remove technical barriers so they can fully realize the potential of their data.12,55,58

Vision for the Future: Toward EHS Data Harmonization

Because the SRP science-driven collaborative projects centered on combining existing data to address a scientific research question, they were able to reveal barriers to interoperability and reuse, as well as realistic solutions. Their experiences highlighted the need for improving how data is collected, annotated, and disseminated among the broader EHS research community moving forward.7

Changing the Culture

In all scientific disciplines, including EHS, working with large data sets and sharing data are fast becoming a necessity rather than a novel undertaking reserved for those with data science expertise. This goes hand in hand with the movement toward policies that require data sharing (e.g., ref (6)) and promote ethical data inquiry from diverse perspectives and expanded inclusivity.59,60 Together, these initiatives are changing the culture around research and data.

Data sharing should continue to facilitate reuse to leverage existing research and to accelerate the pace of translating data to knowledge.7 This shift will benefit EHS researchers and promote the development of new tools, technologies, and practices that enable data sharing and integrative analyses, such as pipelines for processing data, community-driven data reporting standards and semantic data models,61 or minimum information checklists62 to ensure necessary metadata are collected.

Discussions are still underway regarding the best strategies to incentivize data sharing,63 such as data or software attributions.64 In the interim, researchers should make their data available in repositories in standardized, nonproprietary formats, with digital object identifiers whenever feasible, and with clear guidelines for use. They should also make software, code, and libraries necessary to analyze the data available as openly as possible and work collaboratively to develop resources and tools for the broader community.13 One proposed idea is a data trust where collaborators can share data in real time, therefore maximizing the data’s potential without the significant lag between publishing and data availability.11

Another facet to changing the research culture involves journals, who often drive what data researchers share. Along with the steady increase in open access publishing,65 journals have increasingly begun to support making underlying data and code available as part of their publishing requirements.66 While many journals are revising author guidelines to include data and code availability, some are currently insufficient for allowing reproducibility, let alone effective integration with other data sets, such as those requiring the data and code be made available only upon request.14,67

For this to be successful, researchers across disciplines, data scientists, journals, and repositories should work together to make interoperability a reality. For example, researchers and data scientists must work together to create robust data management plans, while repositories and journals can collaborate to create the infrastructure and policy requirements needed to ensure necessary metadata is captured and made available.

Protecting Data and People

It is important to recognize that not all data can, or needs to, be shared. Raw data and information necessary to document, support, and validate research findings should be made as widely and freely available as possible while safeguarding and protecting private, confidential, and proprietary data.

Researchers must also acknowledge cultural differences and trust dynamics while designing ethical strategies to sharing data. For example, federal institutes are exploring and identifying new strategies to include and collaborate with American Indian and Alaska Native populations in developing appropriate strategies for management and sharing of Tribal data68 and to consider broader perspectives and considerations that may be important to specific groups facing environmental injustices or stigmas.69

As this is an emerging area, best practices for how to ethically source and protect such data will continue to evolve. This includes safeguarding de-identification of data to prevent re-identification,70 certificates of confidentiality, robust security measures, and new strategies for involving affected communities in the process of deciding how data are protected and used.

Building the Infrastructure and Integrating Expertise

In addition to facilitating the reuse of existing EHS data to maximize the efficiency of research dollars and reveal new insights, funding agencies can support the integration of data management infrastructure to promote interoperability and reusability before data are collected for a research project.6,71−74

This infrastructure fosters data management and integration success by establishing, coordinating, and monitoring steps for collecting, processing, and analyzing data. By creating shared data standards and systems between biomedical, environmental science, and engineering projects, teams are better positioned to exchange and interpret data across disciplines and accelerate the translation of data to knowledge.

Research institutions and funders of research should leverage data scientists, data librarians, and informaticists who bring unique insights to facilitate better data management and sharing practices across research projects and disciplines. These specialists can work together with subject matter experts so unique perspectives and needs can be properly considered. By integrating expertise, teams will be able to create standard reproducible analysis pipelines and apply AI/ML approaches that maximize the potential of research.58 By integrating this expertise within EHS, investigators will have guidance on how to develop and maintain robust data documentation and data management protocols and will therefore produce more reproducible data that can be shared and maintained long-term.75 Together, researchers and data scientists can work together to create user-friendly tools and visualizations that allow scientists and the public to interact with and interrogate data.7

In addition, data science training for principal investigators and graduate and postdoctoral trainees is critical. Beyond the rigorous multidisciplinary training necessary within EHS,76 cultivating data science best practices allows them to plan projects to collect data with the FAIR principles in mind while advancing their research in innovative directions. Similarly, investing in opportunities for trainees empowers them with the tools to become leaders in the next generation of data-savvy researchers.

Building a Community of Practice

Making EHS data FAIR requires a broad array of interconnected and parallel activities to facilitate data integration and analysis. It requires a robust data management infrastructure, data-knowledgeable researchers and skilled data scientists who work together collaboratively, and involvement of repository managers and journal editors to promote specific requirements and incentives for sharing data and metadata. This is a growing area that will continue to accelerate with data sharing policies taking effect (e.g., ref (6)) along with improvements in data analysis, data infrastructure, and computing.

New challenges will continue to arise as scientists seek to combine more diverse types of data to answer more complex research questions. Researchers across EHS can continue to contribute to and use knowledge and data from existing community resources (e.g., refs (21 and 77)) while developing and refining new tools. With input from an engaged community, guiding principles like FAIR can continue to adapt to keep pace with this rapidly evolving area.78

This community of practice ties in with the broader collaborative culture related to open science, which leverages technology to empower the open sharing of data, information, and knowledge within the research community and the public to accelerate scientific discovery and understanding.13,79

By expanding data science initiatives across EHS more broadly and connecting groups across diverse earth and health sciences, such as the Federation of Earth Science Information Partners,80 the Chemistry GO FAIR Implementation Network,81 and the Research Data Alliance,82 there is an opportunity to build and refine a data management and sharing community of practice. These collaborations can address existing challenges in EHS, such as developing new tools to predict how chemicals may affect long-term health and connecting exposures that occur early in life and prior to conception with diseases that manifest much later, as well as new problems as they emerge.83

Biography

Michelle Heacock, Ph.D., received her doctorate from Texas A & M University for her work on the interplay between DNA repair proteins and telomeres. Her postdoctoral work was conducted at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) where she where she focused on the base excision repair pathway and on understanding the causes of cellular toxicity caused by DNA-damaging agents. She is a Program Officer with NIEHS, where she oversees grants that support research in DNA repair and telomere biology, and multiproject grants that span biomedical science and environmental science and engineering for the Superfund Research Program (SRP). She also is the lead for SRP’s data science and sharing initiatives, where she helps to foster activities that focus on increasing the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) of SRP datasets, emphasizing data interoperability and reusability. Dr. Heacock has been with NIEHS since 2007.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.1c08383.

Table S-1 summarizes the collaborative projects described in this Perspective, including their original goals, challenges encountered, and steps toward solutions (PDF)

Author Contributions

# All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission. M.L.H. and A.R.L. contributed equally.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Funding source: National Institutes of Health Funding source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Research funding: Funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- NIEHS . Program mandates: Superfund Research Program; https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/centers/srp/about/program/index.cfm.

- Suk W. A.; Heacock M. L.; Trottier B. A.; Amolegbe S. M.; Avakian M. D.; Carlin D. J.; Henry H. F.; Lopez A. R.; Skalla L. A. Benefits of basic research from the Superfund Research Program. Rev. Environ. Health. 2020, 35 (2), 85–109. 10.1515/reveh-2019-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk W. A.; Heacock M. L.; Trottier B. A.; Amolegbe S. M.; Avakian M. D.; Henry H. F.; Carlin D. J.; Reed L. G. Assessing the economic and societal benefits of SRP-funded research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126 (6), 065002. 10.1289/EHP3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk W. A.; Heacock M.; Carlin D. J.; Henry H. F.; Trottier B. A.; Lopez A. R.; Amolegbe S. M. Greater than the sum of its parts: focusing SRP research through a systems approach lens. Rev. Environ. Health. 2021, 36, 451. 10.1515/reveh-2020-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heacock M. L.; Amolegbe S. M.; Skalla L. A.; Trottier B. A.; Carlin D. J.; Henry H. F.; Lopez A. R.; Duncan C. G.; Lawler C. P.; Balshaw D. M.; Suk W. A. Sharing SRP data to reduce environmentally associated disease and promote transdisciplinary research. Rev. Environ. Health. 2020, 35 (2), 111–122. 10.1515/reveh-2019-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Final NIH Policy for Data Management and Sharing; National Institutes of Health: 2020; https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-21-013.html.

- SRP . White paper: enhancing the integration, interoperability, and reuse of SRP-generated data through external use cases. 2021. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/centers/srp/assets/docs/srp_euc_white_paper.pdf.

- Stingone J. A.; Triantafillou S.; Larsen A.; Kitt J. P.; Shaw G. M.; Marsillach J. Interdisciplinary data science to advance environmental health research and improve birth outcomes. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111019. 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S.; Aga D.; Pruden A.; Zhang L.; Vikesland P. Data analytics for environmental science and engineering research. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55 (16), 10895–10907. 10.1021/acs.est.1c01026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Tong D.; Wei J.; Meyer D. Integrating data to find links between environment and health. Eos 2021, 102, 102. 10.1029/2021EO158802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan V.; Gherardini P. F.; Krummel M. F.; Fragiadakis G. K. A “data sharing trust” model for rapid, collaborative science. Cell. 2021, 184 (3), 566–570. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenkirk M. T.; Reif D. M.; Baker E. S. Multiomic Big Data analysis challenges: increasing confidence in the interpretation of artificial intelligence assessments. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93 (22), 7763–7773. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R.; Bugbee K.; Murphy K. From open data to open science. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, 1. 10.1029/2020EA001562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo L.; Küngas R.; Oras E.; Köster K.; Eenmaa H.; Leijen Ä.; Pedaste M.; Raju M.; Astapova A.; Lukner H.; Kogermann K.; Sepp T. Data sharing practices and data availability upon request differ across scientific disciplines. Sci. Data 2021, 8 (1), 192. 10.1038/s41597-021-00981-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M. D.; Dumontier M.; Aalbersberg I. J.; Appleton G.; Axton M.; Baak A.; Blomberg N.; Boiten J.-W.; da Silva Santos L. B.; Bourne P. E.; Bouwman J.; Brookes A. J.; Clark T.; Crosas M.; Dillo I.; Dumon O.; Edmunds S.; Evelo C. T.; Finkers R.; Gonzalez-Beltran A.; Gray A. J.G.; Groth P.; Goble C.; Grethe J. S.; Heringa J.; ’t Hoen P. A.C; Hooft R.; Kuhn T.; Kok R.; Kok J.; Lusher S. J.; Martone M. E.; Mons A.; Packer A. L.; Persson B.; Rocca-Serra P.; Roos M.; van Schaik R.; Sansone S.-A.; Schultes E.; Sengstag T.; Slater T.; Strawn G.; Swertz M. A.; Thompson M.; van der Lei J.; van Mulligen E.; Velterop J.; Waagmeester A.; Wittenburg P.; Wolstencroft K.; Zhao J.; Mons B. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. K.; Breden F. The adaptive immune receptor repertoire community as a model for FAIR stewardship of big immunology data. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2020, 24, 71–77. 10.1016/j.coisb.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano S.; Julier A. C. M. How FAIR are plant sciences in the twenty-first century? The pressing need for reproducibility in plant ecology and evolution. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2021, 288 (1944), 20202597. 10.1098/rspb.2020.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löbe M.; Matthies F.; Stäubert S.; Meineke F. A.; Winter A. Problems in FAIRifying medical datasets. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2020, 270, 392–396. 10.3233/SHTI200189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles S. J.; Frey J. G.; Willighagen E. L.; Chalk S. J. Taking FAIR on the ChIN: The Chemistry Implementation Network. Data Intell. 2020, 2 (1–2), 131–138. 10.1162/dint_a_00035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkade D.; Shepherd A. Geoscience data publication: practices and perspectives on enabling the FAIR guiding principles. Geosci. Data J. 2021, 00, 1–10. 10.1002/gdj3.120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. J.; Grulke C. M.; Edwards J.; McEachran A. D.; Mansouri K.; Baker N. C.; Patlewicz G.; Shah I.; Wambaugh J. F.; Judson R. S.; Richard A. M. The CompTox Chemistry Dashboard: a community data resource for environmental chemistry. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9 (1), 61. 10.1186/s13321-017-0247-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watford S.; Edwards S.; Angrish M.; Judson R. S.; Friedman K. P. Progress in data interoperability to support computational toxicology and chemical safety evaluation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 380, 114707. 10.1016/j.taap.2019.114707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martone M. E.; Garcia-Castro A.; VandenBos G. R. Data sharing in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73 (2), 111–125. 10.1037/amp0000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood L.; Rowen L. The Human Genome Project: big science transforms biology and medicine. Genome Med. 2013, 5 (9), 79. 10.1186/gm483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman O. J.; Jones M. B.; Schildhauer M. P. Challenges and opportunities of open data in ecology. Science 2011, 331 (6018), 703–705. 10.1126/science.1197962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielian A.; Engle E.; Harris M.; Wollenberg K.; Juarez-Espinosa O.; Glogowski A.; Long A.; Patti L.; Hurt D. E.; Rosenthal A.; Tartakovsky M. TB DEPOT (Data Exploration Portal): A multi-domain tuberculosis data analysis resource. PLoS One 2019, 14 (5), e0217410 10.1371/journal.pone.0217410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC . Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H.; Goto S.; Sato K.; Fujibuchi W.; Bono H.; Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27 (1), 29–34. 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M.; Ball C. A.; Blake J. A.; Botstein D.; Butler H.; Cherry J. M.; Davis A. P.; Dolinski K.; Dwight S. S.; Eppig J. T.; Harris M. A.; Hill D. P.; Issel-Tarver L.; Kasarskis A.; Lewis S.; Matese J. C.; Richardson J. E.; Ringwald M.; Rubin G. M.; Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25 (1), 25–29. 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazma A.; Hingamp P.; Quackenbush J.; Sherlock G.; Spellman P.; Stoeckert C.; Aach J.; Ansorge W.; Ball C. A.; Causton H. C.; Gaasterland T.; Glenisson P.; Holstege F. C.; Kim I. F.; Markowitz V.; Matese J. C.; Parkinson H.; Robinson A.; Sarkans U.; Schulze-Kremer S.; Stewart J.; Taylor R.; Vilo J.; Vingron M. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 2001, 29 (4), 365–371. 10.1038/ng1201-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.; Domrachev M.; Lash A. E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30 (1), 207–210. 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B.; Riemer C.; Hardison R. C.; Burhans R.; Elnitski L.; Shah P.; Zhang Y.; Blankenberg D.; Albert I.; Taylor J.; Miller W.; Kent W. J.; Nekrutenko A. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 2005, 15 (10), 1451–1455. 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi-Tope G.; Gillespie M.; Vastrik I.; D’Eustachio P.; Schmidt E.; Bono B.d.; Jassal B.; Gopinath G. R.; Wu G. R.; Matthews L.; Lewis S.; Birney E.; Stein L. Reactome: a knowledgebase of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, D428–32. 10.1093/nar/gki072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen R.; Sugawara H.; Shumway M. The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D19–21. 10.1093/nar/gkq1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wörheide M. A.; Krumsiek J.; Kastenmüller G.; Arnold M. Multi-omics integration in biomedical research - a metabolomics-centric review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1141, 144–162. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velankar S.; Burley S. K.; Kurisu G.; Hoch J. C.; Markley J. L. The Protein Data Bank Archive. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2305, 3–21. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1406-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd J. B.; Greene A. C.; Prasad D. V.; Jiang X.; Greene C. S. Responsible, practical genomic data sharing that accelerates research. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21 (10), 615–629. 10.1038/s41576-020-0257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH . NIH Genomic Data Sharing Policy; https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-14-124.html.

- Howes L. Chemistry data should be FAIR, proponents say. But getting there will be a long road. C&E News 2019, 97 (35), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kush R. D.; Warzel D.; Kush M. A.; Sherman A.; Navarro E. A.; Fitzmartin R.; Pétavy F.; Galvez J.; Becnel L. B.; Zhou F. L.; Harmon N.; Jauregui B.; Jackson T.; Hudson L. FAIR data sharing: the roles of common data elements and harmonization. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 107, 103421. 10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. A.; Spidlen J.; Boyce K.; Cai J.; Crosbie N.; Dalphin M.; Furlong J.; Gasparetto M.; Goldberg M.; Goralczyk E. M.; Hyun B.; Jansen K.; Kollmann T.; Kong M.; Leif R.; McWeeney S.; Moloshok T. D.; Moore W.; Nolan G.; Nolan J.; Nikolich-Zugich J.; Parrish D.; Purcell B.; Qian Y.; Selvaraj B.; Smith C.; Tchuvatkina O.; Wertheimer A.; Wilkinson P.; Wilson C.; Wood J.; Zigon R.; Scheuermann R. H.; Brinkman R. R. MIFlowCyt: the minimum information about a Flow Cytometry Experiment. Cytometry 2008, 73A (10), 926–930. 10.1002/cyto.a.20623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria M.; Björnmalm M.; Thurecht K. J.; Kent S. J.; Parton R. G.; Kavallaris M.; Johnston A. P. R.; Gooding J. J.; Corrie S. R.; Boyd B. J.; Thordarson P.; Whittaker A. K.; Stevens M. M.; Prestidge C. A.; Porter C. J. H.; Parak W. J.; Davis T. P.; Crampin E. J.; Caruso F. Minimum information reporting in bio-nano experimental literature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13 (9), 777–785. 10.1038/s41565-018-0246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voehringer P.; Nicholson J. R. Minimum information in In Vivo research. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2019, 257, 197–222. 10.1007/164_2019_285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz P.; Kottmann R.; Field D.; Knight R.; Cole J. R.; Amaral-Zettler L.; Gilbert J. A.; Karsch-Mizrachi I.; Johnston A.; Cochrane G.; Vaughan R.; Hunter C.; Park J.; Morrison N.; Rocca-Serra P.; Sterk P.; Arumugam M.; Bailey M.; Baumgartner L.; Birren B. W.; Blaser M. J.; Bonazzi V.; Booth T.; Bork P.; Bushman F. D.; Buttigieg P. L.; Chain P. S. G.; Charlson E.; Costello E. K.; Huot-Creasy H.; Dawyndt P.; DeSantis T.; Fierer N.; Fuhrman J. A.; Gallery R. E.; Gevers D.; Gibbs R. A.; Gil I. S.; Gonzalez A.; Gordon J. I.; Guralnick R.; Hankeln W.; Highlander S.; Hugenholtz P.; Jansson J.; Kau A. L.; Kelley S. T.; Kennedy J.; Knights D.; Koren O.; Kuczynski J.; Kyrpides N.; Larsen R.; Lauber C. L.; Legg T.; Ley R. E.; Lozupone C. A.; Ludwig W.; Lyons D.; Maguire E.; Methé B. A.; Meyer F.; Muegge B.; Nakielny S.; Nelson K. E.; Nemergut D.; Neufeld J. D.; Newbold L. K.; Oliver A. E.; Pace N. R.; Palanisamy G.; Peplies J.; Petrosino J.; Proctor L.; Pruesse E.; Quast C.; Raes J.; Ratnasingham S.; Ravel J.; Relman D. A.; Assunta-Sansone S.; Schloss P. D.; Schriml L.; Sinha R.; Smith M. I.; Sodergren E.; Spor A.; Stombaugh J.; Tiedje J. M.; Ward D. V.; Weinstock G. M.; Wendel D.; White O.; Whiteley A.; Wilke A.; Wortman J. R.; Yatsunenko T.; Glöckner F. O. Minimum information about a marker gene sequence (MIMARKS) and minimum information about any (x) sequence (MIxS) specifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29 (5), 415–420. 10.1038/nbt.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C. J.; Boyles R.; Lawler C. P.; Haugen A. C.; Dearry A.; Haendel M. Laying a community-based foundation for data-driven semantic standards in environmental health sciences. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124 (8), 1136–40. 10.1289/ehp.1510438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temprosa M.; Moore S. C.; Zanetti K. A.; Appel N.; Ruggieri D.; Mazzilli K. M.; Chen K.-L.; Kelly R. S.; Lasky-Su J. A.; Loftfield E.; McClain K.; Park B.; Trijsburg L.; Zeleznik O. A.; Mathé E. A. COMETS Analytics: an online tool for analyzing and meta-analyzing metabolomics data in large research consortia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 147. 10.1093/aje/kwab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Hu H.; Diller M.; Hogan W. R.; Prosperi M.; Guo Y.; Bian J. Semantic standards of external exposome data. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111185. 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer G.; Connolly A.; von Goetz N.; Bessems J.; Bruinen de Bruin Y.; Coggins M. A.; Fantke P.; Galea K. S.; Gerding J.; Hader J. D.; Heussen H.; Kephalopoulos S.; McCourt J.; Scheepers P. T. J.; Schlueter U.; van Tongeren M.; Viegas S.; Zare Jeddi M.; Vermeire T. Towards further harmonization of a glossary for exposure science-an ISES Europe statement. J. Expo Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 2021, 1. 10.1038/s41370-021-00390-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEHS . Environmental Health Language Collaborative; https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/ehlc/index.cfm.

- Pavlopoulos G. A.; Secrier M.; Moschopoulos C. N.; Soldatos T. G.; Kossida S.; Aerts J.; Schneider R.; Bagos P. G. Using graph theory to analyze biological networks. BioData Min. 2011, 4, 10. 10.1186/1756-0381-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecho K.; Bizon C.; Miller F.; Schurman S.; Schmitt C.; Xue W.; Morton K.; Wang P.; Tropsha A. A biomedical knowledge graph system to propose mechanistic hypotheses for real-world environmental health observations: cohort study and informatics application. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9 (7), e26714 10.2196/26714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shefchek K. A.; Harris N. L.; Gargano M.; Matentzoglu N.; Unni D.; Brush M.; Keith D.; Conlin T.; Vasilevsky N.; Zhang X. A.; Balhoff J. P.; Babb L.; Bello S. M.; Blau H.; Bradford Y.; Carbon S.; Carmody L.; Chan L. E.; Cipriani V.; Cuzick A.; Della Rocca M.; Dunn N.; Essaid S.; Fey P.; Grove C.; Gourdine J. P.; Hamosh A.; Harris M.; Helbig I.; Hoatlin M.; Joachimiak M.; Jupp S.; Lett K. B.; Lewis S. E.; McNamara C.; Pendlington Z. M.; Pilgrim C.; Putman T.; Ravanmehr V.; Reese J.; Riggs E.; Robb S.; Roncaglia P.; Seager J.; Segerdell E.; Similuk M.; Storm A. L.; Thaxon C.; Thessen A.; Jacobsen J. O. B.; McMurry J. A.; Groza T.; Köhler S.; Smedley D.; Robinson P. N.; Mungall C. J.; Haendel M. A.; Munoz-Torres M. C.; Osumi-Sutherland D. The Monarch Initiative in 2019: an integrative data and analytic platform connecting phenotypes to genotypes across species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (D1), D704–d715. 10.1093/nar/gkz997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal C. C.; Wang H.. Managing and Mining Graph Data; Springer Science: New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe T. A. M.; Vidler J.; Halsall C.; Hunt N.; Whaley P. A survey of systematic evidence mapping practive and the case for knowledge graphs in environmental health and toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 175 (1), 35–49. 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning to Advance Environmental Health Research and Decisions: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief; The National Academies Press: 2019; https://www.nap.edu/read/25520/chapter/1.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Workshop : Harnessing artificial intelligence and machine learning to advance biomedical research; 2018; https://datascience.nih.gov/sites/default/files/AI_workshop_report_summary_01-16-19_508.pdf.

- Rahman S.; Lan J.; Kaeli D.; Dy J.; Alshawabkeh A.; Gu A. Machine learning-based biomarkers identification from toxicogenomics - bridging to regulatory relevant phenotypic endpoints. J. Hazard Mater. 2022, 423, 127141. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comess S.; Akbay A.; Vasiliou M.; Hines R. N.; Joppa L.; Vasiliou V.; Kleinstreuer N. Bringing Big Data to bear in environmental public health: challenges and recommendations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 31. 10.3389/frai.2020.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Bridge2AI) Grand Challenge Team Building Expo; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & National Institutes of Health: 2021; https://commonfund.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Bridge2AI-June-23%202021-Expo-FINAL-SUMMARY-508.pdf.

- Notice of NIH’s Interest in Diversity; National Institutes of Health: 2019; https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-20-031.html.

- Thessen A.; Grondin C. J.; Kulkarni R. D.; Brander S.; Truong L.; Vasilevsky N.; Callahan T. J.; Chan L. E.; Westra B.; Willis M.; Rothenberg S. E.; Jarabek A. M.; Burgoon L.; Korrick S. A.; Haendel M. A. Community approaches for integrating environmental exposures into human models of disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128 (12), 125002. 10.1289/EHP7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAIRsharing.org . Minimum information about animal toxicology experiments in vivo; https://fairsharing.org/FAIRsharing.wYScsE.

- Devriendt T.; Shabani M.; Borry P. Data sharing in biomedical sciences: a systematic review of incentives. Biopreserv. Biobank 2021, 19 (3), 219–227. 10.1089/bio.2020.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz D. S.; Hong N. P. C.; Clark T.; Muench A.; Stall S.; Bouquin D.; Cannon M.; Edmunds S.; Faez T.; Feeney P.; Fenner M.; Friedman M.; Grenier G.; Harrison M.; Heber J.; Leary A.; MacCallum C.; Murray H.; Pastrana E.; Perry K.; Schuster D.; Stockhause M.; Yeston J. Recognizing the value of software: a software citation guide. F1000Res. 2020, 9, 1257. 10.12688/f1000research.26932.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso M.; Welling P.; Bukvova H.; Nyman L.; Björk B.-C.; Hedlund T. The development of open access journal publishing from 1993 to 2009. PLoS One 2011, 6 (6), e20961 10.1371/journal.pone.0020961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stodden V.; Guo P.; Ma Z. Toward reproducible computational research: an empirical analysis of data and code policy adoption by journals. PLoS One 2013, 8 (6), e67111 10.1371/journal.pone.0067111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stodden V.; Seiler J.; Ma Z. An empirical analysis of journal policy effectiveness for computational reproducibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115 (11), 2584–2589. 10.1073/pnas.1708290115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH NIH Tribal consultation report: NIH draft policy for data management and sharing; 2020; https://osp.od.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/Tribal_Report_Final_508.pdf.

- NIH Data sharing strategies for environmental health science; https://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/assets/docs/data_sharing_strategies_for_environmental_health_science_meeting_report_508.pdf.

- Sweeney L.; Yoo J. S.; Perovich L.; Boronow K. E.; Brown P.; Brody J. G. Re-identification risks in HIPAA Safe Harbor data: A study of data from one environmental health study. Technol. Sci. 2017, 2017, 2017082801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEHS . Data Management and Analysis Cores; https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/srp/data/dmac.cfm.

- Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health: 2019; https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-19-025.html.

- NSF . Dissemination and Sharing of Research Results - NSF Data Management Plan Requirements; https://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/dmp.jsp.

- USGS . Data Management Plans; https://www.usgs.gov/products/data-and-tools/data-management/data-management-plans.

- Choirat C.; Braun D.; Kioumourtzoglou M.-A. Data science in environmental health research. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2019, 6 (3), 291–299. 10.1007/s40471-019-00205-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin D. J.; Henry H.; Heacock M.; Trottier B.; Drew C. H.; Suk W. A. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program: a model for multidisciplinary training of the next generation of environmental health scientists. Rev. Environ. Health. 2018, 33 (1), 53–62. 10.1515/reveh-2017-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin C. J.; Davis A. P.; Wiegers T. C.; King B. L.; Wiegers J. A.; Reif D. M.; Hoppin J. A.; Mattingly C. J. Advancing exposure science through chemical data curation and integration in the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124 (10), 1592–1599. 10.1289/EHP174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M. D.; Dumontier M.; Sansone S.-A.; Bonino da Silva Santos L. O.; Prieto M.; Batista D.; McQuilton P.; Kuhn T.; Rocca-Serra P.; Crosas M.; Schultes E. Evaluating FAIR maturity through a scalable, automated, community-governed framework. Sci. Data 2019, 6 (1), 174. 10.1038/s41597-019-0184-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfle M.; Olliaro P.; Todd M. H. Open science is a research accelerator. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3 (10), 745–748. 10.1038/nchem.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESIP . Earth Science Information Partners; https://www.esipfed.org/.

- Chemistry GO FAIR; https://www.go-fair.org/implementation-networks/overview/chemistryin/.

- RDA . Research Data Alliance for Newcomers; https://rd-alliance.org/about-rda/rda-newcomers.

- Amolegbe S.; Carlin D.; Henry H.; Heacock M.; Trottier B.; Suk W. Understanding exposures and latent disease risk within the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 529. 10.1177/15353702221079620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.