Abstract

This paper aims to describe and analyse progress with domestic HIV-related policies in PEPFAR partner countries, utilising data collected as part of PEPFAR’s routine annual program reporting from U.S. government fiscal years 2010 through 2016.

402 policies were monitored for one or more years across more than 50 countries using the PEPFAR policy tracking tool across five policy process stages: 1. Problem identification, 2. Policy development, 3. Policy endorsement, 4. Policy implementation, and 5. Policy evaluation. This included 219 policies that were adopted and implemented by partner governments, many in Africa. Policies were tracked across a wide variety of subject matter areas, with HIV Testing and Treatment being the most common. Our review also illustrates challenges with policy reform using varied, national examples. Challenges include the length of time (often years) it may take to reform policies, local customs that may differ from policy goals, and insufficient public funding for policy implementation.

Limitations included incomplete data, variability in the amount of data provided due to partial reliance on open-ended text boxes, and data that reflect the viewpoints of submitting PEPFAR country teams.

Keywords: HIV, policy, law, PEPFAR

Introduction

Public policies can significantly improve public health. Examples abound, including smoke-free laws for tobacco control (Levy et al., 2018) and seat belt laws to reduce motor vehicle fatalities. (Lee et al., 2015), Policy, defined here as ‘a law, regulation, procedure, administrative action, incentive, or voluntary practice of governments and other institutions,’ (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019) is one means to affect population health. With regard to HIV/AIDS control, evidence-based policies can directly prohibit certain behaviours such as discrimination on the basis of HIV status or require other actions like provision of HIV treatment to all persons living with HIV (PLHIV). (Government of Mozambique, 2014) HIV – related policies can also be more nuanced. For instance, HIV testing can be increased by policies or guidelines that allow health care providers to routinely initiate HIV testing with patient consent. (Roura et al., 2013) And treatment guidelines can help authorise HIV treatment to be delivered by trained nurses and non-physician clinicians in areas where doctors are scarce, including much of sub-Saharan Africa. (World Health Organization, 2016) In Malawi, a national policy calling for immediate initiation of lifelong Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) upon HIV diagnosis regardless of CD4 count for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) was followed by a seven-fold increase in the number of HIV positive pregnant and breastfeeding women started on ART compared to the period before the policy. (Chimbwandira et al., 2013) Policies can affect the quantity and quality of HIV service delivery, as well as patient health outcomes. Further, according to the report of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, policies on stigma, discrimination, gender, and key populations may, depending on how they are structured, either facilitate or hinder delivery of HIV services. (United Nations Development Programme, 2012)

Global policy on HIV and AIDS underwent a dramatic change in the early 2000s. In the year 2000, less than 1% of HIV positive people in low and middle-income countries had access to life saving ART. (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2015) An HIV diagnosis was a death sentence, unless the patient was one of the fortunate minority to have access to ART. (Broder, 2010) For years, civil society had been mobilising around the world to pressure politicians and global decision-makers for action. In the early 2000s leaders responded with bold steps. In 2002, the multilateral Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria (Global Fund) was established, resulting from a United Nations-led public-private partnership that continues today. The Global Fund has channelled billions of dollars to resource-limited countries to prevent and treat HIV, TB, and malaria, resulting in an estimated 2.4 million lives saved just between 2003 and 2007. (Komatsu et al., 2010) In 2003, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was created by U.S. legislation to support the prevention care and treatment of HIV in resource-limited countries. (United States Congress, 2003) Subsequent legislation expanded PEPFAR’s mandate and financed the largest global health program targeting a specific disease in history. To date, over $70 billion has been spent through PEPFAR (including HIV, TB, and Global Fund contributions). (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017) PEPFAR’s biomedical programs (ART, PMTCT, and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC)) are credited with averting 2.9 million HIV infections and saving an estimated 11.6 million years of life in sixteen African countries between 2004 and 2013. (Heaton et al., 2015) As the afore-referenced study included only certain biomedical interventions, there may be further impact on mortality and morbidity from other PEPFAR funded interventions, such as HIV testing or TB treatment. As of 2018, approximately 23.3 million of the 37.9 million HIV positive people in the world were on ART (WHO, 2018), including over 14.6 million with PEPFAR support (PEPFAR, 2019a). In sum, the policies of donor countries provided for the creation of well-financed entities and programs like the Global Fund and PEPFAR that have helped control HIV and AIDS around the world.

But what about the countries receiving this assistance? Have such nations advanced their own HIV-related policies? This paper aims to describe and analyse advancements in HIV-related policies in PEPFAR partner countries, utilising data collected by PEPFAR since 2010. The prior year, the U.S. government acting through the State Department began entering into multi-year Partnership Framework agreements with PEPFAR partner countries. (PEPFAR, 2009) In all, 22 bilateral Partnership Frameworks were signed, delineating joint plans including over 250 policy reforms to be pursued by partner countries to improve the HIV response. In 2013, the Institute of Medicine published an evaluation of PEPFAR’s first decade and observed that ‘PEPFAR has increasingly supported partner countries in the development of national frameworks, policies, and strategic plans.’ As noted in the evaluation’s program impact logic model, laws and policies, when implemented, can affect service delivery outcomes leading to sustained program and health impacts (Institute of Medicine, 2013).

Since 2010, PEPFAR has required its field staff to report on HIV-related partner country policies. This Policy Tracking Table tool has been completed by PEPFAR field staff in more than fifty countries, to measure HIV-related policy change by partner nations.

As of 2015, PEPFAR also required all annual program planning to include a section on two priority policies, which is documented in the Country Operation Plan (COP) prepared each year. This section outlines the work that PEPFAR will perform in the subsequent year to advance policies critical to successful HIV programming. Activities to support policy advancement are now documented as part of PEPFAR program planning. PEPFAR has emphasised national adoption and implementation of the 2015 WHO Treatment Guidelines that recommend initiating treatment immediately for all PLHIV regardless of CD4 count and recommend differentiated care models for stable patients, but PEPFAR country teams highlight other critical policies as well. Additionally, as of 2014, PEPFAR requires that PEPFAR country teams, together with stakeholders, measure sustainability of the national HIV response through the Sustainability Index and Dashboard (SID) tool that monitors overall sustainability and key elements of policy and governance. The SID tool, completed biennially, is harmonised with the UNAIDS National Commitments and Policies Instrument to reduce the need for primary data collection.

In the present paper, our purpose is to describe HIV-related policy advancements in PEPFAR partner countries.

Methods

The policy stages framework has been articulated in different forms since the 1940s and continues to be employed as a method of measuring policy change. (Hill & Hupe, 2002) The framework facilitates monitoring of a policy by classifying it according to its stage in a cycle, such as: 1. agenda setting, 2. policy formulation, 3. policy adoption, 4. policy implementation, 5. policy evaluation. (Fadlallah et al., 2019). PEPFAR used an adapted version of a policy stages framework to monitor HIV related policies for seven years.

Data were collected as part of PEPFAR’s routine annual program reporting from U.S. government fiscal years 2010 through 2016. PEPFAR’s Annual Program Results reporting instrument included the Policy Tracking Table. One Policy Tracking Table was completed for each policy monitored by PEPFAR country team. The number of policies tracked was largely at the discretion of PEPFAR country teams, although in fiscal year 2016 each country team was asked by PEPFAR headquarters to report on a set of key HIV-related policies, namely those on Test and Treat, Task Shifting, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), differentiated service delivery with multi-month ART prescriptions, and greater involvement of community health workers in HIV services.

All Policy Tracking Tables submitted by PEPFAR field offices to PEPFAR’s headquarters in Washington DC were exported from the FACTSINFO database to Microsoft Excel, which was used for quantitative analysis. The data collection tool uses a five-stage framework to measure policy progress, both quantitatively (e.g. from one stage to the next) and qualitatively (e.g. noting barriers to and facilitators of policy reform). The tool’s five stages summarise the policy cycle: 1. Identify baseline policy issue or problem, 2. Develop policy intervention and document, 3. Official government endorsement of policy, 4. Implement policy, and 5. Evaluation of policy impact on health. Coding of each policy was done according to the policy stage.

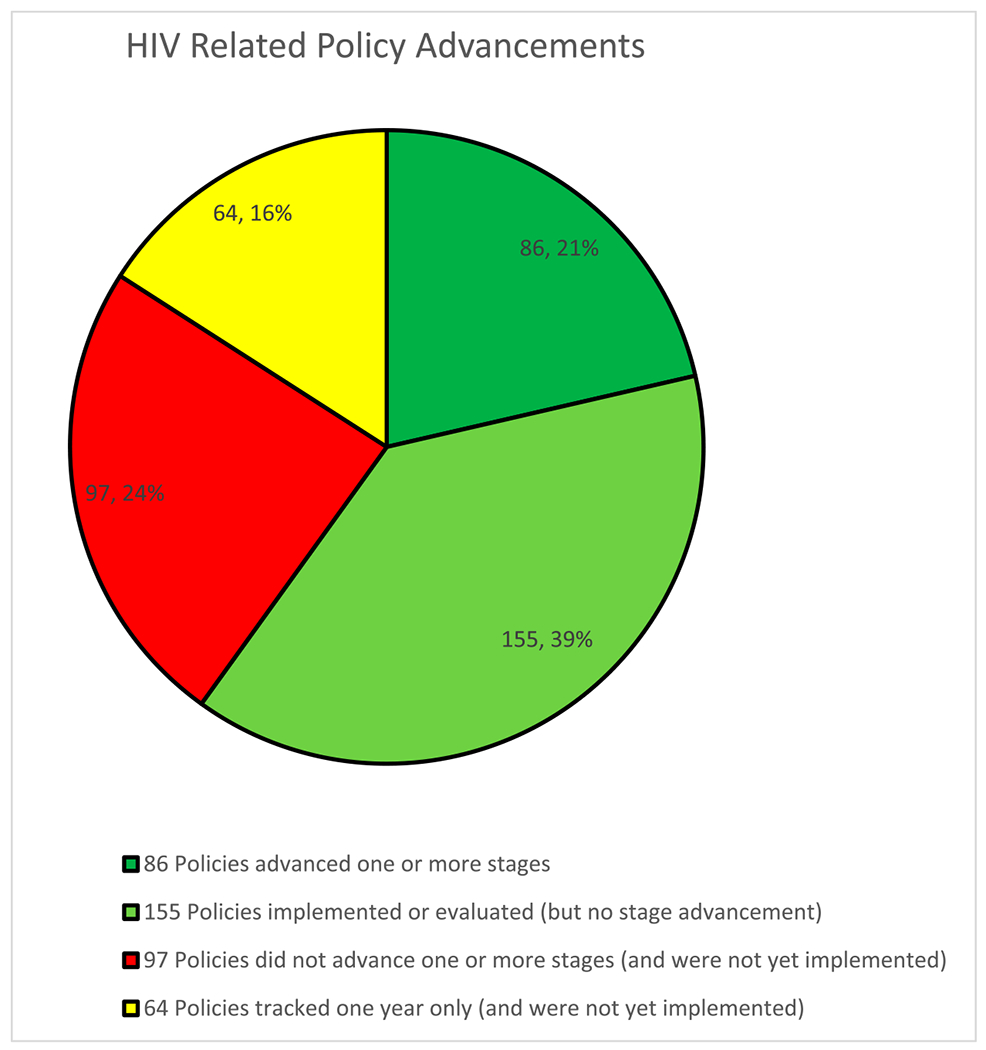

As noted in a previous publication, ‘Similar multi-stage policy development and adoption frameworks, referred to as the heuristic stages, have been discussed at length in the public policy literature.’ (Brewer & DeLeon, 1983; Lane et al., 2016; Lasswell, 1956). Although policy development, adoption, implementation, and evaluation is not necessarily a linear process, the simplification of the policy process into such stages allows for quantitative (albeit imperfect) measurement of advancements. For example, progress may still occur within a stage (e.g. more vigorous implementation of a policy) without progress to the next stage. Such advancements within stages are not captured by looking solely at movement across the five stages employed. Therefore, a color-coding scheme was employed to account for progress not involving advancements across stages. In this scheme, policies that advanced one or more stages across multiple years were coded Dark Green. Policies that did not advance one or more stages across multiple years but were already at one of the advanced stages of implementation or evaluation were coded Light Green. Policies tracked for one year only and which were not yet at the implementation stage were coded Yellow. Lastly, policies that did not advance one or more stages across multiple years and were at the less advanced stages of problem identification, development, or adoption were coded as Red. Figure 1 summarises HIV-related policy advancements using this color-coding scheme for all Policy Tracking Tables reported from 2010 to 2016.

Figure 1.

HIV related policy advancements.

Results

From 2010–2016, 402 policies were monitored for one or more years across more than 50 countries using the PEPFAR Policy Tracking Tables, of which at least 73% (296 policies) were supported by PEPFAR. The types of support provided by PEPFAR included provision of data and conduct of pilot projects to inform policy reform; membership in Technical Working Groups developing policies; convening of stakeholders; increasing policy implementation by disseminating policies and training health workers, patients, and others in policies’ content; procurement of supplies such as added ARVs to implement Test and Treat policies; evaluation of policies; and other means. PEPFAR support of policy advancement is likely underestimated since the Policy Tracking Table only requested a description of PEPFAR support in reporting years 2014–2016, not from 2010–2013.

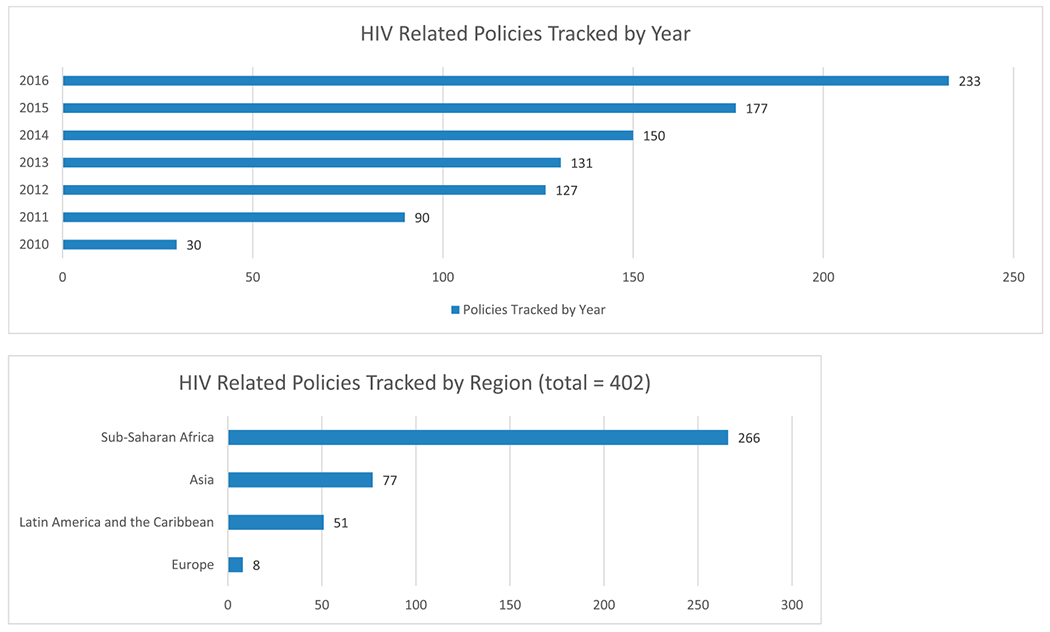

Of these 402 policies, 86 (21%) advanced one or more stages, 155 (39%) were implemented or evaluated but did not advance one or more stages, 64 (16%) were tracked one year only and were not yet at the implementation stage, and 97 (24%) did not advance one or more stages and were not yet at the implementation stage. Thus, 241 policies (60%) either advanced one or more stages or were already at an advanced stage. Figure 1 summarises these HIV-Related Policy Advancements in PEPFAR partner countries. Figure 2 shows that the number of policies tracked increased every year between 2010 and 2016.

Figure 2.

Policies tracked by year and region.

Sub-Saharan Africa was the region with the most policies monitored, 266 out of 402 (66%), followed by Asia with 77 (19%), Latin America and the Caribbean with 51 (13%), and Europe (i.e. Ukraine) with 8 (2%) [Figure 2]. This distribution generally reflects PEPFAR’s geographic focus over this time period. Policies were tracked across a wide variety of subject matter areas, with HIV Testing and Treatment being the most common area, followed by Task Sharing and other Health Workforce policies. The top three subject matter categories and respective number of policies tracked were: HIV Testing and Treatment (98, including 23 Test and Treat policies), Task Sharing and other Health Workforce (62), and Key Populations (30). Other policy subject matter areas tracked included: Children, Primary Health Care, Laboratory, Gender, Stigma and Discrimination, Health Information, HIV Prevention, Finance, Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision, Tuberculosis, HIV Strategic Planning, Supply Chain, Nutrition, Blood Safety, and Military.

Table 1 lists various illustrative policies that were adopted and implemented (including many Test and Treat policies in 2016) by country and year. Table 1 also notes policies that had not been adopted and implemented.

Table 1.

Illustrative HIV-Related Policies adopted and implemented (green) as reported in PEPFAR Policy Tracking Tables from USG FY 2010–2016 One illustrative policy listed per country per year even when multiple were adopted and implemented. Yellow indicates policies tracked but not yet adopted and implemented.

| Country/Region | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | PITC | GBV Law | GBV Law | GBV Law | |||

| Botswana | Health Inspections | Health Inspections | Health Inspections | GBV Law | Age of Testing | Test and Treat | |

| Burma | Test and Treat | ||||||

| Burundi | Test and Treat | ||||||

| Cambodia | Expanded Testing | Test and Treat | |||||

| Cameroon | Task Shifting | ||||||

| Caribbean | Discrimination | Dual Practice | HIV Management | Stigma | Stigma | Test and Treat | |

| Central America | Public ART Funding | ART Access | MARPs | ||||

| Central Asia | Blood Safety | Rapid Testing | Task Shifting | ||||

| China | Test and Treat | ||||||

| Cote d’Ivoire | Task Shifting | ART Guidelines | Multi-Month Rx | ||||

| Dominican Republic | AIDS Law | AIDS Law | Health Professions | Health Professions | Test and Treat | ||

| DRC | Nutrition | Infection Control | Infection Control | Infection Control | |||

| Eswatini | VMMC | Essential Medicines | Human Trafficking | HIV Law | Child Protection | Child Protection | |

| Ethiopia | Condoms | Condoms | Condoms | Test and Treat | |||

| Ghana | Lab Accreditation | Public ART Funding | Public ART Funding | Lab Accreditation | Test and Treat | ||

| Guyana | OVC | Discrimination | |||||

| Haiti | Task Shifting | Nutrition | ART Guidelines | MDR TB | Infection Control | ||

| India | Women | Migrants | Children | PMTCT Option B | Blood Safety | Testing Quality | |

| Indonesia | CSO Funding | CSO Funding | CSO Funding | ||||

| Kenya | VMMC | Testing | Testing | ART Guidelines | Health Workforce | Test and Treat | |

| Laos | PrEP | Test and Treat | |||||

| Lesotho | VMMC | OVC | Medicines Control | TB/HIV | Task Shifting | Task Shifting | Test and Treat |

| Malawi | Child Protection | Nutrition | VMMC | Gender Equity | eHealth | Health Promotion | Test and Treat |

| Mozambique | Blood Service | VMMC | Public ART Funding | Public ART Funding | Test and Treat | ||

| Namibia | Extension Workers | VMMC | Test and Treat | ||||

| Nigeria | Testing | Supply Chain | Task Sharing | Health Information | Task Sharing | ||

| Russia | PHC Integration | ||||||

| Rwanda | Task Shifting | Task Shifting | Task Shifting | Test and Treat | |||

| South Sudan | Test and Treat | ||||||

| Tanzania | EID | Law of the Child | Procurement | GBV | PMTCT Option B+ | Task Shifting | |

| Thailand | Test and Treat | Test and Treat | |||||

| Uganda | HIV Trust Fund | Health Workforce | Decentralization | ||||

| Ukraine | MAT Regulations | MAT Regulations | Laboratory Quality | Test and Treat | |||

| Vietnam | Health Workforce | Joint Procurement | Rapid Testing | MAT | SHI Coverage | ||

| Zambia | ART Guidelines | GBV Law | Gender | HIV/AIDS Strategy | CHWs | Test and Treat | |

| Zimbabwe | Infection Control | Sex Worker Rights | Test and Treat |

Acronyms:

ART = Anti-Retroviral Therapy

CHWs = Community Health Workers

CSO = Civil Society Organization

DR = Dominican Republic

DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo

EID = Early Infant Diagnosis for HIV

GBV = Gender Based Violence

MAT = Methadone Assisted Therapy

MDR TB = Multi Drug Resistant Tuberculosis

OVC = Orphans and Vulnerable Children

PITC = Provider Initiated Testing and Counseling

PMTCT = Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission

PrEP = Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

SHI = Social Health Insurance

VMMC = Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision

Qualitatively, there were many illustrative examples of progress as well as barriers to policy advancement. We selected a few examples of each to convey a sense of the challenges and solutions to policy strengthening.

In Botswana, according to the PEPFAR Policy Tracking Tables, the Test and Treat policy advanced from stage 3 (adoption) in 2015 to stage 5 (evaluation) in 2016. The policy was adopted in 2015, implementation had commenced, and an evaluation was planned in 2016. PEPFAR support to Botswana for the Test and Treat policy included technical guidelines development, cost estimates in partnership with UNAIDS, and additional funding to implement the policy. This support was agreed to in discussions between Botswana’s Ministry of Health and Wellness and PEPFAR’s leadership. Botswana’s Test and Treat policy was developed, passed, and implemented in only one year, as was the case for Test and Treat policies in several other countries between 2015 and 2016. Through 2016, PEPFAR tracked the passage of twenty-three Test and Treat policies, including fifteen in Africa, five in Asia, as well as the Dominican Republic, the Caribbean region, and Ukraine. PEPFAR contributions to development, adoption, and implementation of Test and Treat policies by partner countries included convening stakeholders, participation on Technical Working Groups, provision of health and financial data, formulation of training materials, execution of trainings, and additional funding for implementation contingent on policy adoption. These PEPFAR data correlate well with data from the World Health Organization showing high uptake of Test and Treat policies. (WHO, 2017)

In Kenya, the Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision policy was already at stage 5 (evaluation) when the PEPFAR team began to track its progress in 2011. The policy was passed by the Ministry of Health in 2008, and engagement of political and community leaders was prioritised at the time. (Mwandi et al., 2011) From 2011 to 2015, PEPFAR support was provided for training, monitoring and evaluation, and implementation. During this time, Kenya’s program reached progressively more patients from 330,000 VMMC procedures completed as of 2011 to a cumulative total of 770,000 (more than double) only two years later.

In Nigeria, the Task Sharing policy moved from stage 1 (identification of issues) in 2012 to stage 4 (implementation) in 2016, after passage in 2014 by the National Council on Health. This policy authorises prescription and dispensing of anti-retroviral medication (ARVs) by non-physician clinicians at primary health care sites thus overcoming a major barrier to universal HIV treatment and authorises sharing of many other health care tasks with lower level cadres when appropriate. (Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, 2014) PEPFAR support for Nigeria’s Task Sharing policy included funding policy development meetings with the Federal Ministry of Health, health professional regulatory bodies, and other stakeholders, as well as review of health care workers’ curricula and conduct of trainings to roll out the policy. Adoption of this Federal level policy by Nigeria’s states is noted in the 2016 Policy Tracking Table as necessary for successful implementation.

In Zambia, a noteworthy example of policy implementation was PEPFAR’s translation into local languages of an abridged version of the national Gender Based Violence (GBV) Act. Accompanying the translation was support for community-based education sessions on the GBV Act’s protective provisions.

The Policy Tracking Tables also identified policy reforms that were moving slowly or had stalled. The following examples provide a sense of some of the challenges to reform. In Thailand, coverage of PrEP for key populations (men who have sex with men and transgender people) in national public health insurance was under development during 2015 and 2016. Over the two years, PEPFAR supported this policy process by funding a PreP pilot project, an evaluation to learn from the pilot and inform national scale up, and generation of cost-effectiveness data. A noted barrier to greater use of PrEP was the lack of public funding which required the patient to bear the costs. To address this affordability barrier, Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health has since requested that provincial health offices provide PrEP to those in need. In Mozambique, health financing for universal health care and HIV commodities did not advance beyond stage 2 (development) from 2014 to 2016. PEPFAR supported technical working groups and data generation (e.g. National Health Account) to help advance this policy. PEPFAR tracking data suggest that skepticism of health insurance versus the current norm of publicly delivered services with major donor support may have been a barrier to progress.

Transmission of HIV from older males to adolescent girls and young women is a key issue in sub-Saharan Africa, with 80% of new HIV infections among adolescents aged 15–19 occurring in females. (UNAIDS, 2019). In Malawi and in Tanzania, legal reforms to prohibit minors from marrying (Marriage Age Act and Law of Marriage Act, respectively) did not progress beyond stage 1 (identification of issues). Although Malawi’s Marriage Age Act passed in 2015, it still allowed children to marry with parental consent. Possible reasons for the relative lack of progress include custom (in Malawi, data from 2000 and 2010 show that one of every two girls were married by age 18) and financial interests of the bride’s parents. Civil society organisations in Tanzania have advocated against child marriage since the 1980s and PEPFAR support led to renewed public discussion in both countries. It should be noted that major breakthroughs occurred in both countries after the PEPFAR APR data we reviewed were collected. In 2016, a Tanzanian court ordered the legislature to raise the legal age of marriage to 18 and an appellate decision in 2019 reaffirmed the order. (Adebayo, 2019). In 2017, Malawi passed a Constitutional amendment prohibiting marriage by persons under the age of 18, without exception. (Daniel, 2017)

Discussion

Our review found that hundreds of policies affecting HIV, health services, and human rights were tracked by PEPFAR in over fifty partner countries. From 2010–2016, PEPFAR monitored 219 policies that were adopted and implemented by partner governments (many with PEPFAR support) to improve HIV responses while advancing health systems and human rights. These policies included legislation, regulations, guidelines, and various other normative instruments. Policy implementation was specifically tracked, and well over one hundred policies were found to be at the implementation stage or at the later stage of evaluation. Positive examples of policy implementation included translation and dissemination of a law into local languages, conducting trainings of the health workforce to increase their awareness of and receptivity to new rights and duties, providing actual policy documents and simplified job aides to health facilities, and provision of additional funding to procure ARVs. Challenges noted included lack of partner government resources to disseminate, train people in, and enforce policies. Several policy evaluations were reported, assessing implementation as a basis for future programming. PEPFAR support for policy advancement consisted of financial and technical assistance for policy development, dissemination, training and various other activities and was reported at all stages of the policy process. PEPFAR provided support to most policies it tracked, presumably manifesting a reporting bias towards policies it considered most relevant.

Other studies have assessed the alignment of national policies with global, normative guidance (Verani et al., 2016), analysed the alignment of national policies with clinical practice in health facilities (Dasgupta et al., 2016), or conducted policy surveillance to evaluate policies’ health impacts (Burris et al., 2016). Our study reports on a policy monitoring system used by PEPFAR, a major global donor and technical assistance provider for HIV programs, to track progress and challenges with various HIV related policies across more than fifty countries on four continents. Our findings reinforce the complex challenges inherent in policy reform (Schmitt et al., 2018) and the persistence requisite to monitor and support policy change and improved implementation over time.

Limitations of our review included incomplete data, variability in the amount of data provided due to partial reliance on open-ended text boxes, and data that reflected the viewpoint of PEPFAR country team members responsible for data entry but not necessarily of partner government or civil society counterparts. It should be noted that policies were monitored by PEPFAR teams as required but were not necessarily tracked by partner countries.

Conclusion

PEPFAR’s commitment to monitor HIV-related policy changes is evident by these seven years of data and by its more recent efforts to monitor sustainability factors (including HIV-related policies) through its HIV/AIDS Sustainability Index and Dashboard. (PEPFAR, 2016) Furthermore, PEPFAR has prioritised policies such as HIV index testing and Treat All for support during its annual Country Operational Planning (COP) process. (PEPFAR, 2019b) Moving forward, it is vital to monitor whether the planned activities to advance policy occurred and to evaluate whether and how policy changes are associated with program results or outcomes. Stakeholders may want to periodically review data pertaining to partner country HIV policies, such as the data from PEPFAR reviewed in this manuscript, and from global institutions such as WHO (WHO, 2017), UNAIDS (UNAIDS, 2019), and UNDP (UNDP, 2015), and from partner countries themselves. Our review also illustrates the challenges with policy reform and the time it can take to advance policies. We hope this paper informs policy monitoring and evaluation approaches as an integral part of efforts to prevent and control HIV/AIDS.

Funding

This research was supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the United States Agency for International Development.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adebayo B (2019, October 23). Tanzanian court upholds a law banning child marriage. CNN. https://www.cnn.com. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G, & DeLeon P (1983). The foundations of policy analysis. Dorsey Press. [Google Scholar]

- Broder S (2010). The development of antiretroviral therapy and its impact on the HIV-1/AIDS pandemic. Antiviral Research, 85(1), 1–18. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris S, Hitchcock L, Ibrahim J, Penn M, & Ramanathan T (2016). Policy surveillance: A vital public health practice comes of age. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 41(6), 1151–1173. 10.1215/03616878-3665931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimbwandira F, Mhango E, Makombe S, Midiani D, Mwansambo C, Njala J, & Houston J (2013). Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV — Malawi, July 2011–September 2012. MMWR, 62(8), 148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel A (2017, February 23). Malawi amends Constitution to remove child marriage loophole: children can no longer marry with parental consent. Human Rights Watch Dispatch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/02/23/malawi-amends-constitution-remove-child-marriage-loophole. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta ANZ, Wringe A, Crampin AC, Chisambo C, Koole O, Makombe S, Sungani C, Todd J, & Church K (2016). HIV policy and implementation: A national policy review and an implementation case study of a Rural area of Northern Malawi. AIDS Care, 28(9), 1097–1109. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1168913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadlallah R, El-Jardali F, Nomier M, Hemadi N, Arif K, Langlois EV, & Akl EA (2019). Using narratives to impact health policy-making: A systematic review. Health Research, Policy and Systems, 17(1), 26. 10.1186/s12961-019-0423-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Mozambique. (2014). Law 19 of 2014 Protection of the Person, Worker and Candidate for Employment living with HIV and AIDS. Retrieved August 21, 2017, from http://www.wlsa.org.mz/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/NovaLeiHIV_SIDA.pdf.

- Heaton LM, Bouey PD, Fu J, Stover J, Fowler TB, Lyerla R, & Mahy M (2015). Estimating the impact of the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief on HIV treatment and prevention programmes in Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 91(8), 615–620. 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M, & Hupe P (2002). Implementing public policy: Governance in theory and in practice. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2013). Evaluation of PEPFAR. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2013/Evaluation-of-PEPFAR.aspx.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2017). U.S. Global Health Funding: PEPFAR. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://kff.org/global-health-policy/slide/u-s-global-health-funding-for-the-presidents-emergency-plan-for-aids-relief-pepfar/.

- Komatsu R, Korenromp EL, Low-Beer D, Watt C, Dye C, Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Lyerla R, Garcia-Calleja JM, Cutler J, & Schwartländer B (2010). Lives saved by Global Fund-supported HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria programs: Estimation approach and results between 2003 and end-2007. BMC Infectious Diseases, 10 (1), 109. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J, Verani A, Hijazi M, Hurley E, Hagopian A, Judice N, & Katz A (2016). Monitoring HIV and AIDS related policy reforms: A road map to strengthen policy monitoring and implementation in PEPFAR partner countries. PLoS One, 11(2). Article e0146720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell H (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. Bureau of Governmental Research, College of Business and Public Administration, University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Burghardt LC, Fleegler EW, Nigrovic LE, Meehan WP, & Mannix R (2015). Motor vehicle crash fatalities and seat belt laws. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163, I–33. doi: 10.7326/M14-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Yuan Z, Luo Y, & Mays D (2018). Seven years of progress in tobacco control: An evaluation of the effect of nations meeting the highest level MPOWER measures between 2007 and 2014. Tobacco Control, 27(1), 50–57. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwandi Z, Murphy A, Reed J, Chesang K, Njeuhmeli E, Agot K, Llewellyn E, Kirui C, Serrem K, Abuya I, Loolpapit M, Mbayaki R, Kiriro N, Cherutich P, Muraguri N, Motoku J, Kioko J, Knight N, Bock N, & Sansom SL (2011). Voluntary medical male circumcision: Translating research into the rapid expansion of services in Kenya, 2008–2011. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), Article e1001130. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health. (2014, August). Task-Shifting and Task-Sharing Policy for Essential Health Care Services in Nigeria. Retrieved May 22, 2017, from http://www.health.gov.ng/doc/TSTS.pdf.

- PEPFAR. Guidance for PEPFAR Partnership Frameworks and Partnership Framework Implementation Plans (2009); Next Generation Indicators Reference Guide (2013); Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Indicator Reference Guide (2015). Retrieved May 31, 2017, from https://2009-2017.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/240108.pdf.

- PEPFAR. (2016). Report on the 2016 PEPFAR Sustainability Indices and Dashboards (SIDs). Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Building-a-Sustainable-Future-Report-on-the-2016-PEPFAR-Sustainability-Indices-and-Dashboards-SIDs.pdf.

- PEPFAR. (2019a). Annual Report to Congress. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PEPFAR2019ARC.pdf.

- PEPFAR. (2019b). Fiscal Year 2019 Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) Guidance. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/PEPFAR-Fiscal-Year-2019-Country-Operational-Plan-Guidance.pdf.

- Roura M, Watson-Jones D, Kahawita TM, Ferguson L, & Ross DA (2013). Provider-initiated testing and counselling programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of their operational implementation. Aids (london, England), 27(4), 617–626. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b7048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CL, Curry L, Boudewyns V, Williams PA, Glasgow L, Van Hersh D, Willett J, & Rogers T (2018). Relationships between theoretically derived short-term outcomes and support for policy among the public and decision-makers. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, E57. 10.5888/pcd15.170288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (2015). AIDS by the Numbers. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/AIDS_by_the_numbers_2015_en.pdf.

- UNAIDS. (2019). Global HIV & AIDS Statistics. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- UNAIDS. (2019). Laws and Policies Analytics. http://lawsandpolicies.unaids.org/.

- UNDP. (2012). HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights, and Health. Final Report of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law. http://www.hivlawcommission.org/resources/report/FinalReport-Risks,Rights&Health-EN.pdf.

- UNDP. (2015). HIV and AIDS Legal Environment Assessments. Retrieved May 24, 2017, from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/hiv-aids/legal-environment-assessments.html.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Definition of Policy. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/policy/analysis/process/definition.html.

- United States Congress. (2003). Public Law 108-25. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ25/PLAW-108/publ25.pdf.

- Verani AR, Emerson CN, Lederer P, Lipke G, Kapata N, Lanje S, Peters AC, Zulu I, Marston BJ, & Miller B (2016). The role of the law in reducing tuberculosis transmission in Botswana, South Africa and Zambia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(6), 415–423. 10.2471/BLT.15.156927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed. See Chapter 6.8 Task Shifting and Sharing. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208825/1/9789241549684_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2017. July). Treat All: Policy Adoption and Implementation Status in Countries. Retrieved August 21, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258538/1/WHO-HIV-2017.35-eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global Health Observatory Data. https://www.who.int/gho/hiv/epidemic_response/ART/en/.