Abstract

U.S. Latino parents can face cultural stressors in the form of acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and a negative context of reception. It stands to reason that these cultural stressors may negatively impact Latino youth’s emotional well-being and health risk behaviors by increasing parents’ depressive symptoms and compromising the overall functioning of the family. To test this possibility, we analyzed data from a six-wave longitudinal study with 302 recently immigrated (<5 years in the United States) Latino parents (74% mothers, Mage = 41.09 years) and their adolescent children (47% female, Mage = 14.51 years). Results of a cross-lagged analysis indicated that parent cultural stress predicted greater parent depressive symptoms (and not vice versa). Both parent cultural stress and depressive symptoms, in turn, predicted lower parent-reported family functioning, which mediated the links from parent cultural stress and depressive symptoms to youth alcohol and cigarette use. Parent cultural stress also predicted lower youth-reported family functioning, which mediated the link from parent cultural stress to youth self-esteem. Finally, mediation analyses indicated that parent cultural stress predicted youth alcohol use by a way of parent depressive symptoms and parent-reported family functioning. Our findings point to parent depressive symptoms and family functioning as key mediators in the links from parent cultural stress to youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. We discuss implications for research and preventive interventions.

Keywords: Latino Families, Cultural Stress, Family Stress, Emotional Well-Being, Health Risk Behaviors

Parental stress is a normative experience that requires parents to balance the demands of their role as a parent (e.g., providing shelter and food) with their access to resources (e.g., employment and financial resources; Deater-Deckard, 2004). Studies have documented the negative effects of parental stress on their children’s emotional and behavioral well-being (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010; Gassman-Pines, 2015; Leon, 2014; Tran, 2014). According to the Family Stress Model (FSM), parental stress may indirectly influence youth’s emotional and health risk behaviors by compromising the emotional well-being of parents, their parenting behaviors, and family relationships (Conger et al., 2010).

Although many parents experience stress, Latino immigrant parents in the United States may face additional cultural stressors caused by navigating multiple cultural contexts and belonging to an ethnic-minority and stigmatized group (Conger et al., 2011; Tran, 2014). Parents’ cultural stressors may negatively affect the emotional and behavioral well-being of Latino adolescents through parents’ emotional distress, which may impact parents’ relationships with and guidance toward their adolescents (Conger et al., 2010).

Understanding the factors that contribute to Latino youths’ emotional and behavioral well-being is critical given that, compared with non-Latino White and Black youth, Latino youth are at elevated risk for symptoms of depression, suicide attempts (CDC, 2014), cigarette smoking, alcohol use (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015), and aggressive and delinquent behavior (Gibson & Miller, 2010). Informed by the FSM and the cultural stress literature, we investigate the impact of Latino parents’ cultural stress on youth’s emotional well-being and health risk behaviors, as mediated by parents’ depressive symptoms and family functioning in the form of parenting and family cohesion.

Parent Cultural Stress, Parent Depressive Symptoms, and Family Functioning

Cultural stress represents a constellation of multiple factors that contribute to the stress experience of Latinos, including acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and a negative context of reception (Schwartz et al., 2015). Acculturative stress represents the pressure to learn a new language, to maintain one’s native language, to balance differing cultural values, and to broker between American and Latino ways of behaving (Torres, Driscoll, & Voell, 2012). Discrimination refers to perceived experiences of unfair or differential treatment, such as receiving poor service in restaurants or being treated unfairly for having an accent (Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008). Perceived negative context of reception refers to immigrants’ perception of their receiving context as less welcoming and as lacking opportunities for immigrants, such as good employment and schools (Schwartz et al., 2014).

Parents’ cultural stressors may lead to parent emotional distress (Conger et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2014), which, in turn, may affect parenting and family relationships (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth, & Szapocznik, 2003). This may be especially true for immigrant Latino parents who move to the United States to better their children’s future (Perreira, Chapman, & Stein, 2006). Once in the United States, parents may feel disillusioned and hopeless about their future (and that of their children) when they find themselves embedded in a social structure that they cannot change and experience cultural stressors (Perreira et al., 2006). Among Latino adults, acculturative stress (Hovey, 2000), discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013), and a negative context of reception (Schwartz et al., 2014) have been associated with elevated symptoms of depression and with compromised family functioning (Gassman-Pines, 2015; Trail, Goff, Bradbury, & Karney, 2012). Moreover, cross-sectional studies with ethnically diverse families have found parents’ experiences with discrimination and acculturative stress to be directly associated with their children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Leon, 2014; Tran, 2014). Among Mexican immigrant families, parents’ workplace discrimination negatively affected parents’ emotional well-being, family functioning, and children’s externalizing behaviors (Gassman-Pines, 2015). These studies suggest that parent cultural stress may lead to worse family functioning and negatively affect the emotional and behavioral well-being of their children, perhaps by contributing to parents’ emotional distress.

The Family Stress Model

The FSM provides a theoretical framework for understanding the indirect pathways by which parent cultural stress may influence youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. The FSM posits that parents’ perceived cultural stress may lead to increased depressive symptoms in parents, which may disrupt parenting behaviors and family relationships. Poor family functioning (i.e., low positive and involved parenting, low family cohesion) may, in turn, contribute to poor youth emotional well-being and elevated health risk behaviors (Conger et al., 2010). Because adolescent development can be influenced by proximal familial factors such as parenting and family relationships, as well as by more distant familial factors such as parent cultural stress and parent emotional distress (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), the FSM provides an ideal framework to investigate direct and indirect paths by which parent cultural stress may affect youth emotional and behavioral well-being. Although the FSM was originally developed to understand how parents’ financial hardships influence parents’ emotional well-being, family processes, and youth outcomes, scholars and researchers have recommended (Jensen, 2012) that scientists bridge universal (e.g., FSM) with culture-specific frameworks (i.e., cultural stress, health, and adolescent development). This is why other researchers have extended the FSM to investigate how experiences of discrimination, English language pressure, and neighborhood risk influence Latino parents’ depressive symptoms, family processes, and youth development (Conger et al., 2011; White, Roosa, Weaver, & Nair, 2009). Most of this prior work, however, has included only one cultural stressor, and tested some aspects of the FSM, but not others (Conger et al., 2011; Gonzales et al., 2011; White, Liu, Nair, & Tein, 2015; White, Roosa, & Zeiders, 2012; White et al., 2009). For example, in a cross-sectional study with Mexican-origin youth and their families, Conger et al. (2011) investigated the influence of parents’ perceived discrimination (but not acculturative/bicultural stress and negative context of reception) on youth academic outcomes and conduct problems (but not mental health and substance use problems) by way of parents’ emotional distress, interparental conflict, and parents’ child management behaviors. However, Conger et al. (2011) did not conduct mediation analyses to determine whether parent emotional distress, interparental conflict, and parents’ child management behaviors explained the link from parents’ discrimination to youth outcomes. In another cross-sectional study, White et al. (2009) examined how parents’ pressure to speak English (but not discrimination and negative context of reception) influenced their parenting by way of parents’ depressive symptomatology, but they did not link these factors to youth outcomes. Overall, these studies suggest that the FSM could be a useful theoretical model for understanding the process by which parent cultural stress may influence youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. Specifically, parent cultural stress may negatively impact parents’ emotional well-being and family functioning (i.e., their parenting and family relationships).

The Current Study

We test an integrative model examining the mechanisms through which Latino immigrant parents’ cultural stress and depressive symptoms influence adolescents’ well-being. Such an integrative model is important because, although separate studies have investigated the influence of cultural stressors on the emotional well-being and health risk behaviors of Latino youth (Schwartz et al., 2015) and adults (Hovey, 2000; Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013), on parenting practices (White et al., 2009), and on family functioning (Conger et al., 2011), these components have not been examined together. Moreover, past research has largely been cross-sectional, providing limited information about the developmental process by which parents’ cultural stress affects youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors and precluding tests of directionality of mediated associations (Conger et al., 2011; White et al., 2015). Further, scholarship on the FSM with Latino families has focused on the role of parent economic or neighborhood stress, with few studies examining the role of parent cultural stress (White et al., 2015).

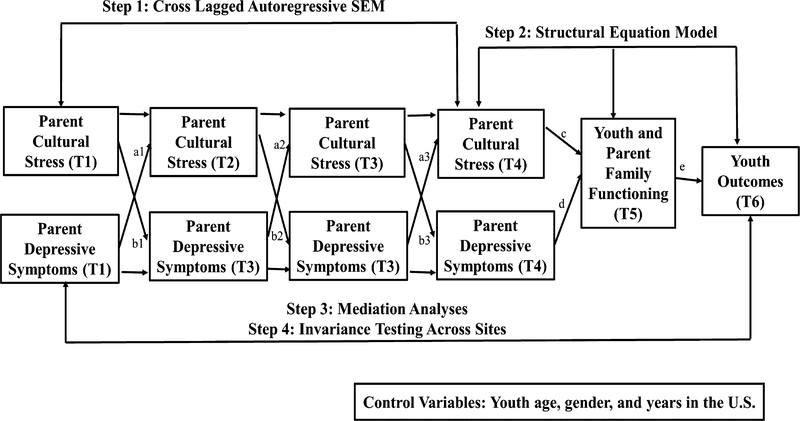

To address these gaps, we combined research and scholarship on cultural stress and the FSM into a unified model and tested the indirect and direct effects of parent cultural stress on adolescent emotional well-being and health risk behaviors using data from a 3-year, six-wave longitudinal study with recently immigrated Latino families (Figure 1). This longitudinal study allowed us to examine the mediating role of parent depressive symptoms and family functioning in the links from parent cultural stress to adolescent health outcomes. First, we established the relationship and directionality between parents’ cultural stress and their depressive symptoms. We did so to determine whether parents with depressive symptoms may be more likely to view their experiences in the United States through a pessimistic lens, possibly contributing to and exacerbating their perceptions of cultural stressors (Conger et al., 2010; Deater-Deckard, 2004). Alternatively, as proposed by the FSM, cultural stress may lead to depressive symptoms in parents (Conger et al., 2010). Thus, identifying the directionality between parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms is important. Knowing which experiences come first can provide insights into how to work with parents to prevent emotional problems and health risk behaviors in youth. Next, we investigated the degree to which parent depressive symptoms and family functioning (youth- and parent-reported parenting and family cohesion) mediated the longitudinal effects of parent cultural stress on a range of youth outcomes. Identifying mediating pathways from parents’ cultural stress to youth outcomes is important because it can further help to identify targets for preventive interventions. We included separate reports of family functioning for adolescents and parents because parents and youth often differ in how they experience family relationships (Larson & Richards, 1994). Moreover, in this study, the correlation between adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning was less than 0.30, suggesting that adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning should be treated as separate constructs. We included a range of youth outcomes for which health disparities exist between Latino and non-Latino White and Black adolescents (CDC, 2014; Gibson & Miller, 2010; Johnston et al., 2015). The inclusion of a range of outcomes allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between parents’ cultural stress and adolescent outcomes. Based on the work reviewed above, we hypothesize the following (Figure 1):

We hypothesized a unidirectional relationship between parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesized that parent cultural stress at Time t (Tt) would predict higher levels of parent depressive symptoms at Time t + 1 (Tt + 1). We tested this hypothesis via a cross-lagged analysis using data collected from the Summer 2010 (T1), the Spring 2011 (T2), the Fall 2011 (T3), and the Spring 2012 (T4).

We also hypothesized that parent cultural stress and depressive symptoms in the Spring 2012 (T4) would predict lower youth- and parent-reported family functioning (i.e., lower positive parenting, lower involved parenting, and lower family cohesion) in the Fall 2012 (T5) as well as youth outcomes in the Spring 2013 (T6).

We further hypothesized that youth- and parent-reported family functioning (i.e., lower positive parenting, lower involved parenting, and lower family cohesion) in the Fall 2012 (T5) would predict youth outcomes in the Spring 2013 (T6). Specifically, we expected low family functioning (i.e., low adolescent-and parent-reported positive parenting, involved parenting, and family cohesion) at T5 (Fall 2012) to be associated with higher levels of T6 (Spring 2013) adolescent depressive symptoms, lower self-esteem, more aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors, and more cigarette and alcohol use.

Finally, we hypothesized that parent depressive symptoms in the Spring 2012 (T4) as well as parent- and youth-reported family functioning (i.e., positive parenting, involved parenting, and family cohesion) in the Spring 2012 (T5) would mediate the effect of parent cultural stress in the Fall 2011 (T3) on youth outcomes in the Spring 2013 (T6).

FIGURE 1. Overview of Analytic Plan.

Note. Prior levels of parent depressive symptoms, parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, and youth outcomes were controlled for in the model although not shown in the figure.

METHOD

Sample

Data came from a six-wave longitudinal study on acculturation, cultural stress, family functioning, and health among recent Latino immigrant families (Schwartz et al., 2014). The sample consisted of 302 adolescent-caregiver dyads from Los Angeles (N = 150) and Miami (N = 152). Only adolescent-caregiver dyads who identified as Latino and had resided in the United States for 5 years or less at baseline were eligible to participate. We deleted nine cases from the sample because the same caregiver did not participate at each of the time points. Among the remaining cases (N = 293), 47% of adolescents were female, and the mean adolescent age at baseline was 14.51 years (SD = 0.88). Each adolescent participated with a primary caregiver (referred to as “parent” in this study; 74% mothers, 22% fathers, 2% stepparents, and 2% grandparents/other relatives). The mean parent age was 41.09 years at baseline (SD = 7.09). About 80% of parents reported an annual income of less than $25,000, and 78.6% had graduated from high school. Miami families were primarily from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), and Colombia (6%). Los Angeles families were primarily from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), and Guatemala (6%). Almost all of the adolescents (98%) and parents (98%) reported Spanish as their “first or usual language”; 82% of adolescents and 87% parents reported “speaking mostly Spanish at home”; and 16% of the adolescents and 11% of parents reported speaking “English and Spanish equally at home.”

Procedures

School selection and participant recruitment

Families were recruited from randomly selected schools in Miami-Dade and Los Angeles Counties (10 schools in Miami, 13 in Los Angeles). We selected schools whose student body was at least 75% Latino. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami, the University of Southern California, and the Research Review Committees for each participating school district.

Assessment procedures

Baseline data were gathered during the Summer 2010, and subsequent data collection occurred during the Spring 2011, Fall 2011, Spring 2012, Fall 2012, and Spring 2013. Assessments were available in Spanish and English and were completed using an audio computer-assisted interviewing system (Turner et al., 1998). Parents provided informed consent for themselves and for their adolescents, and adolescents provided informed assent. Parents received $40 at baseline with incentives increasing by $5 at each subsequent time point. Adolescents received a movie ticket voucher at each time point.

Measures

Unless otherwise specified, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale for all measures, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). We present alpha coefficients at baseline.

Parent cultural stress was treated as a latent variable consisting of discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress at T1–4. Perceived discrimination was measured using the 7-item Perceived Discrimination Scale (Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998; α = .87; Sample item: “How often do people your age treat you unfairly or negatively because of your ethnic background?”). This measure uses a 5-point Likert-type response format ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost always). Perceived negative context of reception was measured with six items (Schwartz et al., 2014; α = .83; Sample item: “I don’t have the same chances in life as people from other countries”). This scale was developed for this study and has been validated with Latina/o parents and adolescents (Schwartz et al., 2014). The scale assesses the degree to which parents felt unwelcomed in their receiving community. Acculturative stress was assessed using 24 items from the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI; Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002), which assesses stress that originates from both United States (sample item: “It bothers me that I speak English with an accent”) and Latino sources (sample item: “I feel pressure to speak Spanish”). Specifically, the MASI assesses acculturative stress that originates from four sources: English competency pressures, Spanish competency pressure, pressure to acculturative, and pressure against acculturation. Parents indicated on a scale, ranging from 0 (Not at all stressful) to 4 (Extremely stressful), the degree to which they experienced each of these acculturative stressors (α = .93).

Parent- and youth-reported family functioning

We obtained parent and adolescent reports of family functioning with parent–adolescent (i.e., parental involvement and positive parenting) and whole-family relational processes (i.e., family cohesion). Parental involvement and positive parenting were assessed using the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996). The parental involvement subscale consisted of 15 items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When was the last time that you talked with your parents about what you were going to do for the coming day?”) and 19 items for parents (α = .79; Sample item: “How many of your child’s friends do you know?”). The positive parenting subscale consisted of nine items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When you have done something that your parents approve of, how often do they say something nice about it?”) and nine for parents (α = .70; Sample item: “When your child has done something that you like or approve of, do you mention it to someone else?”). Family cohesion was measured using the corresponding 6-item subscale from the Family Relations Scale (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). A sample item is “Family members feel very close to each other” (α = .87 for adolescents and .76 for parents). We treated parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning as two separate latent variables each consisting of parental involvement, positive parenting, and family cohesion (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., in press).

Parent and youth depressive symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977; α = .93 for parents and α = .93 for adolescents, sample item: “I felt like crying this week”). Parents and adolescents indicated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree), how depressed they have felt during the past week. We treated parent and youth depressive symptoms as manifest variables.

Adolescent self-esteem was assessed with 10 items (α = .74; Sample item: “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) from the Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale, which has been used with Spanish-speaking populations (Schmitt & Allik, 2005). We treated adolescent self-esteem as a manifest variable.

Adolescent aggressive and rule-breaking behavior were assessed with 32 items from the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2002) and treated as manifest variables. Aggressive behavior was assessed with 17 (α = .93, sample item: “I am mean to others”) and rule-breaking behavior with 15 items (α = .93, sample item: “I break rules at home, school, or elsewhere”). Adolescents rated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Not true) to 2 (Often or very often true), their behavior in the past 6 months.

Adolescent cigarette and alcohol use were assessed with a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 2015). We asked about the frequency of their lifetime and past 90-day cigarette and alcohol use. Because of low base rates and the need to control for prior levels of these behaviors, we created binary variables (1 = Use vs. 0 = Nonuse) at Times 1 and 6. Although it is most common to analyze substance use in the 30 days (Johnston et al., 2015), we conducted analyses using past 90-day cigarette and alcohol use because base rates for past 30-day smoking and drinking were low. We did not include illicit substance use because only eight adolescents reported lifetime use at T6.

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Mplus (version 7.2; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) using a sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) to adjust the standard errors and account for nesting of participants within schools. We evaluated model fit with the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to Little (2013), good model fit is represented by CFI ≥ .95, RMSEA ≤ .05, and SRMR ≤ .06; and adequate fit is represented by a CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .08, and SRMR ≤ .08. We report the χ2 value, but did not use it in interpretation because it tests a null hypothesis of perfect fit, which is rarely plausible in large samples or complex models (Davey & Savla, 2010). To draw directional conclusions, our analyses controlled for prior levels of youth outcomes and all mediating variables (i.e., family functioning; Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

Our analysis proceeded in four steps (Figure 1). In Step 1, we fit a SEM autoregressive cross-lagged model to the first four waves of the data, such that Tt parent cultural stress (latent variable) was allowed to predict parent depressive symptoms at Tt + 1 (paths b); and Tt parent depressive symptoms were allowed to predict Tt + 1 parent cultural stress (paths a). For cultural stress and depressive symptoms, we included autocorrelations between subsequent time points (e.g., Cultural Stress T1 with Cultural Stress T2) to model the stability in each variable over time. Because stationarity, or non-varying cross-lagged paths across time points, is an assumption of autoregressive cross-lagged modeling (Little, 2013), we imposed equality constraints on corresponding autoregressive and cross-lagged paths across time.

In Step 2, we tested a SEM model that led from parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms (T4) to parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning (T5) to youth outcomes (T6). This model included direct effects of parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms (T4) on youth outcomes (T6). We used a robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator because MLR provides odds ratios, which are an intuitive way of interpreting results for categorical variables. In Step 3, we conducted mediation analyses using the full model (Steps 1–3) to test whether parent depressive symptoms and family functioning mediated the effect of parent cultural stress on youth outcomes. In Step 4, we test for site differences in the structural model developed in Step 2.

RESULTS

Step 1: Cross-Lagged Autoregressive SEM

To examine (a) the effect of parent cultural stress on parent depressive symptoms and (b) the effect of parent depressive symptoms on parent cultural stress, we treated cultural stress as a latent variable consisting of parent discrimination, acculturative stress, and negative context of reception (Schwartz et al., 2015). The latent factor model provided good to adequate fit, χ2(30) = 65.59, p < .001; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .064; SRMR = .04, and was associated with metric and scalar longitudinal invariance (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., in press).1 Standardized factor loadings for context of reception, acculturative stress, and discrimination were .61, .41, and .82, respectively.2

The cross-lagged model provided good to adequate fit: χ2(89) = 178.23, p < .001; CFI = .95, RMSEA = .058; SRMR = .06. To evaluate the stationarity assumption, we compared the fit of models with and without equality constraints on corresponding pathways and used the ΔCFI (>.010) and ΔRMSEA (>.010) to decide whether the stationarity assumption should be rejected (Little, 2013). Invariance tests suggested that the stationary assumption could be retained, Δχ2(11) = 25.19, p = .008; ΔCFI = .01; ΔRMSEA = .001. Parent cultural stress at Tt predicted parent depressive symptoms at Tt + 1 (β = .14, p < .001, 95%, CI = .07–.21). Parent depressive symptoms at Tt also predicted cultural stress at Tt + 1, but the effect was small (β = −.02, p = .008, 95% CI = −.04 to −.00) and became nonsignificant in Step 2.

Step 2: Structural Equation Model (SEM)

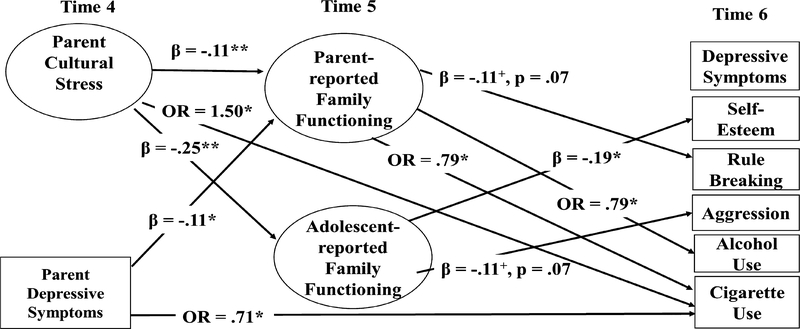

Building on Step 1, we added parent- and youth-reported family functioning at T5 and youth outcomes at T6 to the autoregressive cross-lagged SEM (Figure 1). Parent- and youth-reported family functioning was modeled with separate latent variables consisting of parental involvement, positive parenting, and family cohesion (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., in press). We treated parent- and youth-reported family functioning as separate latent variables because parents and adolescents can perceive the same experiences differently (Larson & Richards, 1994). As such, we aimed at examining how parent- and adolescent-reported functioning had similar relationships with parent cultural stress, parent depressive symptoms, and youth health outcomes.

Because MLR estimation does not provide fit indices with categorical outcomes (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), we first estimated our structural model without the categorical outcomes and included categorical youth outcomes after establishing adequate fit. The model with continuous outcomes fit the data adequately: χ2(162) = 379.59, p < .001; CFI = .929; RMSEA = .068; SRMR = .091.

To rule out alternative explanations for higher symptoms of depression, lower self-esteem, higher aggressive and rule-breaking behavior, as well as higher cigarette and alcohol use, we estimated the model with and without key demographic covariates identified in the literature as predictors of these youth outcomes: age, gender, and years spent in the United States. Standardized path estimates (continuous outcomes), odds ratios (categorical outcomes), and confidence intervals are displayed in Table 1 with and without covariates. Given the similarity of the findings across the two models, results presented below are for the model with covariates. As shown in Figure 2, parent cultural stress (T4) predicted lower adolescent-reported (β = −.25, p < .001, 95% CI = −.38 to −.13) and parent-reported (β = −.11, p < .001, 95% CI = −.17 to −.06) family functioning (T5). Parent depressive symptoms (T4) also predicted parent-reported (β = −.11, p < .05, 95% CI = −.20 to −.02), but not youth-reported family functioning (T5). With regard to youth outcomes (T6), adolescent-reported family functioning (T5) predicted higher self-esteem (β = .20, p < .05, 95% CI = .01–.38) and marginally predicted lower aggression (β = −.11, p = .07, 95% CI = −.23 to .01) (T6). In addition, parent-reported family functioning (T5) predicted a lower likelihood of T6 youth alcohol (OR = .79, p < .05, 95% CI = .65–.96) and cigarette use (OR = .79, p < .05, 95% CI = .65–.95) and marginally predicted lower rule breaking (β = −.11, p = .070, 95% CI = −.22 to .01) (T6). In addition, parent depressive symptoms (T4) predicted lower youth cigarette use (T6) (OR = .71, p < .05, 95% CI = .55–.90); and parent cultural stress (T4) predicted higher cigarette use (T6) (OR = 1.50, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.09–2.06).

Table 1.

Results of Structural Equation Model (Step 2)

| Without Covariates |

With Covariates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictor | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI |

|

| |||||

| Effects of parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms on family functioning | |||||

| Parent family functioning (T5) | Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | −.12** | −.21 to −.03 | −.11* | −.20 to −.02 |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | −14*** | −.21 to −.08 | −.11*** | −.17 to −.06 | |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | .02 | −.09 to .13 | .02 | −.09 to .13 |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | −.32*** | −.44 to −.20 | −25*** | −.38 to −.13 | |

| Effects of family functioning, parent depressive symptoms, and cultural stress on youth outcomes | |||||

| Depressive symptoms (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | .01 | −.09 to .10 | .00 | −.10 to .10 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | −.13† | −.29 to .02 | −.13 | −.31 to .03 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | −.01 | −.15 to .13 | −.01 | −.15 to .13 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | −.04 | −.17 to .08 | −.03 | −.16 to .09 | |

| Self-esteem (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | −.05 | −.12 to .05 | −.03 | −.11 to .06 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | .19* | .01 to .37 | .19* | .01 to .38 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | −.04 | −.12 to .04 | −.04 | −.12 to .05 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | −.07 | −.22 to .08 | −.07 | −.23 to .09 | |

| Rule breaking (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | −.10 | −.22 to .02 | −.11† | −.24 to .01 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | −.08 | −.19 to .04 | −.10 | −.22 to .02 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | −.07 | −.23 to .10 | −.08 | −.23 to .09 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | .01 | −.13 to .16 | .03 | −.11 to .17 | |

| Aggression (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | −.03 | −.10 to .05 | −.04 | −.11 to .03 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | −.09 | −.20 to .02 | −.11† | −.22 to .01 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | −.05 | −.20 to .10 | −.05 | −.19 to .09 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | −.01 | −.16 to .15 | .01 | −.14 to .17 | |

| Alcohol use (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | .61* | .39 to .94 | .79* | .65 to .96 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | .73 | .45 to 1.17 | .86 | .70 to 1.06 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | .69 | .40 to 1.21 | .83 | .63 to 1.10 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | 1.33 | .89 to 1.99 | 1.15 | .93 to 1.42 | |

| Cigarette use (T6) | Parent family functioning (T5) | .56* | .36 to .88 | .79** | .65 to .95 |

| Adolescent family functioning (T5) | .90 | .32 to 2.54 | .97 | .65 to 1.45 | |

| Parent depressive symptoms (T4) | .45* | .22 to .91 | .71** | .55 to .90 | |

| Parent cultural stress (T4) | 2.54* | 1.05 to 6.11 | 1.50** | 1.08 to 2.06 | |

Notes. We controlled for prior levels of parent depressive symptoms, parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, and youth outcomes.

p < .100

p < .050

p < .010

p < .001.

FIGURE 2. Results of Structural Equation Model (Step 2).

Note. Only significant and marginally significant paths are shown. We report standardized path coefficients for continuous dependent variables and odds ratios (OR) for categorical dependent variables. Age, gender, and years in the United States were included in the model in order to rule out competing theoretical explanations. Prior levels of parent depressive symptoms, parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, and youth outcomes were controlled for in the model although not shown in the figure. *p < .05, **p < .001, +p = .05 and p < .10.

Step 3: Mediation Analyses

Next, we examined whether parent depressive symptoms and adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning mediated the effect of parent cultural stress on youth outcomes (Parent Cultural Stress T3 → Parent Depressive symptoms T4 → Family Functioning T5 → Youth Outcomes T6). We used the RMediation package (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011) and included all indirect effects in a single model to avoid Type I error inflation. Results indicate that parent cultural stress (T3) predicted youth alcohol use (T6) through parent depressive symptoms (T4) and parent-reported family functioning (T5) (OR = 1.00, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.00). Parent cultural stress (T4) also predicted lower self-esteem (T6) through adolescent-reported family functioning (T5) (β = −.05, p < .05, 95% CI = −.11 to −.00). In addition, parent-reported family functioning (T5) mediated the link between parent cultural stress (T4) and higher T6 alcohol (OR = 1.03, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.06) and cigarette use (OR = 1.03, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.06). Also, through parent-reported family functioning (T5), parent depressive symptoms (T4) predicted higher T6 alcohol (OR = 1.03, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.07) and cigarette use (OR = 1.03, p < .05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.07).

Step 4: Invariance across Site

Finally, we examined potential variance by location in the SEM model. We compared an unconstrained SEM model (all paths free to vary across site) against a constrained SEM model (each path constrained to be equal) with the likelihood ratio test to evaluate the null hypothesis of equivalent findings across sites. The two models did not differ significantly from each other, Δχ2(32) = 28.93, p = .623, suggesting that our findings were equivalent across site.

DISCUSSION

Latino parents in the United States can face cultural stressors in the form of acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and a negative context of reception (Conger et al., 2011; Leon, 2014; Tran, 2014). According to the FSM, stressors may compromise parents’ emotional well-being, thereby leading to poor family functioning, which in turn, could impact the healthy development of Latino youth (Conger et al., 2010, 2011). In this study, we expanded this model by including an array of cultural stressors. Using longitudinal data on recently immigrated Latino families, we evaluated evidence for the mediated pathway from parents’ cultural stress to youth emotional well-being (self-esteem and symptoms of depression) and health risk behaviors (aggressive and rule-breaking behavior, cigarette and alcohol use) through parents’ depressive symptoms and family functioning. Our findings support the FSM. Parent cultural stress negatively impacted youth emotional well-being, cigarette use, and alcohol use by way of parents’ depressive symptoms and compromised family functioning.

We utilized a model-building approach to test our hypothesized model (Figure 1). Access to longitudinal data allowed us to establish the unidirectional relationship between parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms. As hypothesized, parent cultural stress predicted higher levels of parent depressive symptoms and not vice versa. Prior studies have documented positive associations of cultural stressors with depressive symptoms among Latino adults (Hovey, 2000; Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013; Schwartz et al., 2014) and adolescents (Schwartz et al., 2015). However, few studies have employed longitudinal data. As such, previous studies could not rule out the alternative hypothesis that parents’ depressive symptoms may lead to higher perceptions of cultural stress (Deater-Deckard, 2004). Our study adds to this literature by documenting a unidirectional and temporal effect from parent cultural stress to depressive symptoms.

Next, we tested the temporal associations of parent depressive symptoms and parent cultural stress with youth- and parent-reported family functioning. Consistent with the FSM, we hypothesized that parent depressive symptoms and parent cultural stress would lead to compromised family functioning (Conger et al., 2010). As expected, parent cultural stress predicted worse youth- and parent-reported family functioning. In addition, parent depressive symptoms predicted worse parent-reported (but not youth-reported) family functioning. These findings suggest that depressed parents are more likely to perceive poor family functioning, but parent depressive symptoms did not predict adolescents’ perceptions of family functioning.

Our findings corroborate extant cross-sectional research with Latino families. In one study with Mexican-origin youth and their families (Conger et al., 2011), mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms were associated with more interparental conflict, which in turn was related with worse child management reported by fathers and mothers. In another study with Mexican American families (White et al., 2009), fathers’ depressive symptoms related inversely to paternal warmth, and Raffaelli, Iturbide, Carranza, and Carlo (2014), in a cross-sectional study with youth and mothers from diverse Latino backgrounds, found that family cohesion mediated the relationships between mother and daughter distress. We extend this line of research to recent immigrant Latino families and provide much-needed information about the directionality of the link between parent depressive symptoms and family functioning.

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, low youth-reported (but not parent-reported) family functioning predicted lower youth self-esteem, and low parent-reported (but not youth-reported) family functioning predicted more youth alcohol and cigarette use. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, parents’ depressive symptoms and reports of family functioning mediated the effect of parent cultural stress on youth alcohol use. In addition, youth-reported (but not parent-reported) family functioning mediated the effect of parent cultural stress on youth self-esteem, whereas parent-reported (but not youth-reported) family functioning mediated the effect of parent cultural stress on youth alcohol and cigarette use. Although the mediated effect of parent-reported family functioning in the links from parent cultural stress and youth alcohol and cigarette use was relatively small (probably due to low rates of cigarette and alcohol use), findings suggest that youth-reported family functioning may be a good predictor of youth emotional well-being (self-esteem), whereas parent-reported family functioning might be a good predictor of youth health risk behaviors (cigarette, alcohol use). Although this study does not explain why youth- and parent-reported family functioning differentially affect youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors, gathering data from parents and adolescents may provide more nuanced insights into how family functioning influences youth well-being (Larson & Richards, 1994).

Importantly, our findings suggest that preventive interventions for Latino families may benefit from reducing parent cultural stress or by helping parents use coping strategies to manage these stressors. This could be done by adding coping and stress management exercises to evidence-based interventions such as Familias Unidas (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002) and culturally adapted Parent Management Training—The Oregon Model for Latino immigrants (e.g., Parra Cardona et al., 2012). Equally important are macro-level strategies, such as promoting positive views of Latino families and improving contexts of reception (Dessel, 2010).

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, although this study used data from parents and adolescents, data were self-reported. Second, the factor loading for acculturative stress in the parent cultural stress latent variable was low (.41). However, dropping this variable from the analyses did not modify the results. Third, all families had resided in the United States for 5 years or less. Findings may not generalize to later generation Latino families. Fourth, data were collected in two well-established receiving communities. This study may not reflect the experiences of families in less-established receiving communities (Barrington, Messias, & Weber, 2012). Fifth, the majority of families in Miami came from Cuba (61%), and the majority of families in Los Angeles were Mexican (70%), and our findings may not generalize to other recent immigrant Latino subgroups. Although we utilized self-report measures of parenting that have been validated and used previously with Latina/o parents and adolescents (Schwartz et al., 2013), the use of observational parenting measures could further enhance our understanding of how parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms impacts parenting (Domenech Rodriguez, Donovick, and Crowley, 2009). Finally, we did not measure financial or occupational stress, and our findings may not fully capture Latino parents’ cultural stress (Conger et al., 2010).

This study is one of the first to test and establish the temporal relationship between parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms, and to temporally link these experiences with youth- and parent-reported family functioning, as well as with youth outcomes. Our findings point to parent depressive symptoms and family functioning as key mediators by which parent cultural stress affects youth, highlighting the need for preventive interventions to target parent cultural stress, depressive symptoms, and family functioning.

Footnotes

In a related study using the same data (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., in press), we used a latent growth curve analysis to investigate how parent cultural stress developed over time (T1–4). We also investigated how these parent cultural stress trajectories predicted family functioning at a later time point (T5) and how family functioning (T5), in turn, predicted youth outcomes at T6. On average, parent cultural stress remained the same. Increases in parent cultural stress predicted higher parent-reported family functioning and lower adolescent-reported family functioning. Family functioning, in turn, predicted youth outcomes.

Because the factor loading for acculturative stress was low (.41), we dropped this indicator from the parent cultural stress latent variable, repeated all of the analyses, and replicated the results.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2002). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington C, Messias DKH, & Weber L (2012). Implications of racial and ethnic relations for health and well-being in new Latino communities: A case study of West Columbia, South Carolina. Latino Studies, 10, 155–178. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). [Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2014]. MMWR 2013; 63 (No. SS 4). [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2002). Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 113–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1015420503275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Song H, Stockdale GD, Ferrer E, Widaman KF, & Cauce AM (2011). Resilience and vulnerability of Mexican origin youth and their families: A test of a culturally informed model of family economic stress. In Kerig PK, Schulz MS, Hauser ST, Kerig PK, Schulz MS, & Hauser ST (Eds.), Adolescence and beyond: Family processes and development (pp. 268–286). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, & Savla J (2010). Statistical power analysis with missing data: A structural equation modeling approach. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (2004). Parenting stress. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dessel A (2010). Prejudice in schools: Promotion of an inclusive culture and climate. Education and Urban Society, 42, 407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodriguez MM, Donovick MR, & Crowley SL (2009). Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process, 48, 195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A (2015). Effects of Mexican immigrant parents’ daily workplace discrimination on child behavior and family functioning. Child Development, 4, 1175–1190. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, & Miller HV (2010). Crime and victimization among Hispanic adolescents: A multilevel longitudinal study of acculturation and segmented assimilation. A Final Report for the WEB Du Bois Fellowship Submitted to the National Institute of Justice. Washington, DC: Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RM, Knight GP, Zeiders KH et al. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, & Huesmann LR (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 115–129. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD (2000). Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6, 134–151. doi: 10.1037//1099-9809.6.2.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LA (2012). Bridging universal and cultural perspectives: A vision for developmental psychology in a global world. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00213.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2015). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014. Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, & Carroll RJ (2001). A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, & Richards MH (1994). Divergent realities: The emotional lives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Leon AL (2014). Immigration and stress: The relationship between parents’ acculturative stress and young children’s anxiety symptoms. Student Pulse, 6(3), Retrieved from http://www.studentpulse.com/a?id=861 [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Cortina LM (2013). Towards an integrated understanding of Latino/a acculturation, depression, and smoking: A gendered analysis. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 3–20. doi: 10.1037/a0030951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, Romero A, Gonzales-Backen M, Piña-Watson B et al. (in press). Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth mental health and substance use. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén Copyright. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, & Szapocznik J (2003). Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: An ecodevelopmental, parent-centered approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 469–500. doi: 10.1117/0739986303259355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parra Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K et al. (2012). Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: The need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Family Process, 51, 56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01386.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Chapman MV, & Stein GL (2006). Becoming an American parent overcoming challenges and finding strength in a new immigrant Latino community. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1383–1414. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06290041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, & Santos LJ (1998). Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 937–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Iturbide MI, Carranza MA, & Carlo G (2014). Maternal distress and adolescent well-being in Latino families: Examining potential interpersonal mediators. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, & Garcia-Hernandez L (2002). Development of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment, 14, 451–461. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt DP, & Allik J (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 623–642. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Des Rosiers S, Huang S, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP et al. (2013). Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development, 84, 1355–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE et al. (2015). Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW et al. (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0033391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & MacKinnon DP (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, & Zelli A (1997). Assessment of family relationship characteristics: A measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment, 9, 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Driscoll MW, & Voell M (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 17–25. doi: 10.1037/a0026710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trail TE, Goff PA, Bradbury TN, & Karney BR (2012). The costs of racism for marriage: How racial discrimination hurts, and ethnic identity protects, newlywed marriages among Latinos. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 454–465. doi: 10.1177/0146167211429450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AG (2014). Family contexts: Parental experiences of discrimination and child mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 37–46. doi: 10.1007/s1046-013-9607-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LB, Pleck JH, & Sonsenstein LH (1998). Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science, 280, 867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Liu Y, Nair RL, & Tein JY (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51, 649–662. doi: 10.1037/a0038993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Roosa MW, Weaver SR, & Nair RL (2009). Cultural and contextual influences on parenting in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 61–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Roosa MW, & Zeiders KH (2012). Neighborhood and family intersections: Prospective implications for Mexican American adolescents’ mental health. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 793–804. doi: 10.1037/a0029426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]