Abstract

The relationships and interactions within a methanotrophic-heterotrophic groundwater community were studied in a closed system (shake culture) in the presence of methane as the primary carbon and energy source and with the addition of the pure linear alkylbenzenesulfonate (LAS) congener 2-[4-(sulfophenyl)]decan as a cometabolic substrate. When cultured under different conditions, this community was shown to be a stable association, consisting of one obligate type II methanotroph and four or five heterotrophs possessing different nutritional and physiological characteristics. The results of experiments examining growth kinetics and nutritional relationships suggested that a number of complex interactions existed in the community in which the methanotroph was the only member able to grow on methane and to cometabolically initiate LAS transformation. These growth and metabolic activities of the methanotroph ensured the supply of a carbon source and specific nutrients which sustained the growth of four or five heterotrophs. In addition to the obligatory nutritional relationships between the methanotroph and heterotrophs, other possible interactions resulted in the modification of basic growth parameters of individual populations and a concerted metabolic attack on the complex LAS molecule. Most of these relationships conferred beneficial effects on the interacting populations, making the community adaptable to various environmental conditions and more efficient in LAS transformation than any of the individual populations alone.

A number of microbial communities have been studied in which coexisted heterotrophs and obligate methanotrophs, the latter being the unique group of bacteria able to use methane as the only carbon and energy source (3, 6, 12, 26, 33). Despite the relative ease with which methanotrophic-heterotrophic communities have been isolated from different environments (soils, surface layers of sediments, and natural waters), which suggests their ubiquity in nature, only recently have more intensive studies been undertaken to establish the possible significance of these specific associations in the cycling of elements in the biosphere (16, 20, 26, 34).

In addition to the recognized important role of methane-utilizing bacteria in global carbon and nitrogen cycling (3, 10, 11, 16, 19, 27), there are an increasing number of reports about their cometabolic activities in the transformation of multicarbon compounds (1, 9, 14, 19, 23, 38). These cometabolic activities have been described as “fortuitous metabolism,” suggesting that they are due to the broad substrate specificity of the methane monooxygenase enzyme system, whose primary function is to catalyze the oxidation of methane to carbon dioxide. At present, the high potential of methanotrophs in the transformation of low-molecular-weight halogenated hydrocarbons, ubiquitous and toxic pollutants, has been well recognized (2, 5, 8, 13, 15, 16, 25, 28, 29, 30), while the significance of these bacteria in the transformation of more complex compounds, especially aromatic compounds, still awaits recognition.

Although in some cases transformation of complex organic compounds with methanotrophs involves more extensive or even nonoxidative metabolism, products of transformations catalyzed by methane monooxygenase are usually simply hydroxylated derivatives, suggesting that the role of methanotrophic bacteria is only in the initiation of biodegradative attack (1, 16, 19, 37). On the other hand, oxidative cometabolic transformation has been identified as an important initial step in the degradation of diverse complex substrates (xenobiotics), making the substrates more susceptible to further transformation by heterotrophs (1, 4, 7, 9, 14, 19, 32, 37). It follows that, besides the generally accepted important role of heterotrophic bacteria in the mineralization of complex organic compounds, methanotrophs might also have a significant contribution in at least initiating useful metabolism.

The main objective of this work was to better characterize the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community originating from an aquifer material previously characterized to be efficient in cometabolic transformation of trichloroethylene (17, 18), chlorinated biphenyls (1, 37), and linear alkylbenzenesulfonates (LAS) (21, 22, 24). The specific objective was to study possible relationships and interactions between community members during growth in mineral medium with methane as the only carbon and energy source and during the transformation of 2-[4-(sulfophenyl)]decan (2C10LAS) added as a cometabolic substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation of the community and individual populations.

After isolation from aquifer solids of Moffett Field Naval Air Base, Mountain View, Calif. (17), the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community was stored as a liquid culture at 4°C and subcultured every 6 to 8 weeks in 120-ml sealed serum bottles containing 20 ml of nitrate mineral salts (NMS) medium (39). The headspace was filled with a methane-air gas mixture (30:70), and cultures were incubated in a water bath shaker (180 rpm) at 20°C.

The same shake flask technique and NMS medium without copper were applied to study the growth characteristics of the community and its individual populations as well as for 2C10LAS transformation experiments. To achieve suitable methane and oxygen concentrations, different amounts of CH4 (5 to 20 ml) were injected after the withdrawal of an equal volume of air. Methane and oxygen concentrations were monitored by headspace analyses and the desired conditions (low oxygen, excess methane, or excess of both gases) were maintained by the repeated injection of 5 to 20 ml of CH4 and 5 to 20 ml of O2. Culture growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The experiments were carried out at either 20 or 30°C.

Specific growth rates (μ) of the community and its methanotrophic strain for a particular cultivation period (tn − 1 − tn) were calculated from the following equation:

|

where xn and xn − 1 are the biomass concentration (milligrams [dry weight] liter−1) at times tn and tn − 1, respectively.

For the determination of community structure, separate dilution plating was carried out on solid NMS medium with 1% (wt/vol) electrophoresis-grade agarose (GIBCO-BRL, Paisley, Scotland) and nutrient agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). The same NMS-agarose medium was used for culturing and maintaining the pure methanotroph isolated from the community, while for heterotrophic populations, oligotrophic medium containing low concentrations of peptone, yeast extract, and glucose (PYG) (35) was applied instead of nutrient agar. For the methanotroph, the plates were incubated for 10 to 14 days at 30°C, and for heterotrophs, incubation was for 2 to 4 days at 20, 25, or 30°C. NMS-agarose plates were kept in gas-tight jars under a methane and air atmosphere (50:50). The gas phase was replaced every 3 to 4 days with a fresh methane-air mixture. Both the methanotrophic and heterotrophic isolates were stored at 4°C as liquid cultures, and their purity was checked by several successive platings on solid media.

Characterization of individual community populations.

After isolation and confirmation of purity, individual populations were further characterized for their nutritional and physiological properties using the methods discussed by Stanier et al. (36) and by Palleroni and Doudoroff (31). In all testing, the NMS medium (39), solidified with 1.5% Noble agar that was essentially free of impurities (Difco Laboratories), was used as a basal medium, and the selected organic compound as the carbon and energy source was added at a concentration of 0.1%. For nutritional screenings of heterotrophic bacteria, oligotrophic media containing low concentrations of peptone and yeast extract (PY) or PYG (35) were also used.

For cross-growing experiments in which growth stimulation and inhibition effects between community populations were studied, the inoculum was prepared by using a 1-week-old shake flask culture of the methanotrophic strain Met 1 (in early stationary growth phase) and the individual heterotrophs grown on solid PYG medium. Suspensions (OD600, approximately 2.5 to 2.8) were prepared either in NMS medium (for the experiments with individual populations) or in sterile MilliQ water (Millipore, Molsheim, France) (for the experiments with individual population lysates). To facilitate autolysis, suspensions were incubated for 48 h at 37°C and afterwards were filter sterilized (0.22-μm pore diameter; Millipore). Prepared suspensions or autolysates (1 ml) were added to 20 ml of the methanotrophic culture diluted with NMS medium (OD600, 0.1), giving a proportion of methanotrophs to individual heterotrophs of approximately 50:50.

Reagents.

Natural gas containing 98.5% methane was donated by INA Naftaplin (Zagreb, Croatia), and oxygen (Universal Medical) was obtained from MG Croatia Plin (Zagreb, Croatia). All chemicals used for the growth media were of analytical grade, and those used for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis were of HPLC grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Pure (98%) 2C10LAS was donated by EAWAG (Dübendorf, Switzerland).

Headspace analyses.

Methane and oxygen concentrations during growth of the community or during cross-feeding experiments with the methanotrophic and heterotrophic populations were monitored by headspace analyses using a Fisher-Hamilton gas partitioner equipped with a thermal conductivity detector as described previously (22).

2C10LAS analyses.

For quantitative determination of 2C10LAS during transformation, reversed-phase HPLC was used by employing an octylsilica column, 250 by 4.4 mm (inner diameter), 5 μm (Supelcosil LC-18; Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, Pa.), under isocratic conditions. The eluent used was 38 to 42% (vol/vol) acetonitrile containing 10 g of sodium perchlorate per liter. Spectrofluorimetric detection was applied at an excitation wavelength of 230 nm and an emission wavelength of 295 nm.

RESULTS

Growth characteristics of the groundwater community and individual members.

To better evaluate the metabolic activity and possible interactions within the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community originating from an aquifer material, a series of experiments was performed in which the growth kinetics of the community and its methanotrophic member (strain Met 1) were compared. The obtained results (Table 1) illustrated that the groundwater community was capable of stable growth in shake flasks under various experimental conditions (different methane and oxygen concentrations and different temperatures). The general observation was that although it originated from groundwater where the temperature does not exceed 15°C, the community grew faster at higher temperatures (30°C). In accordance with decreased oxygen concentrations relative to the atmosphere in its natural habitat, this community showed a preference for low oxygen concentrations (3 to 5%), and the fastest growth (μ = 0.55 ± 0.03 day−1 [mean ± standard deviation]) was achieved when excess methane (10 to 15%) was maintained in the headspace (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Growth characteristics of the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community and its methanotrophic strain

| Initial headspace concn (%)

|

Growth

rate/daya

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community

|

Methanotroph

|

||||

| CH4 | O2 | 20°C | 30°C | 20°C | 30°C |

| 4.5 | 19.0 | 0.35 ± 0.03 (1) | 0.42 ± 0.03 (1) | 0.27 ± 0.05 (6) | 0.32 ± 0.06 (3) |

| 8.7 | 18.5 | 0.38 ± 0.02 (1) | 0.40 ± 0.04 (0.5) | 0.27 ± 0.06 (5) | 0.30 ± 0.07 (4) |

| 19.4 | 15.5 | 0.36 ± 0.04 (1) | 0.44 ± 0.02 (0.5) | 0.30 ± 0.05 (3) | 0.34 ± 0.07 (2) |

| 20.2b | 14.8 | 0.45 ± 0.03 (0.5) | 0.55 ± 0.03 (0.5) | 0.38 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.45 ± 0.06 (1) |

Average specific growth rate (mean ± standard deviation of three replicates) during the log phase. Data in parentheses indicate lag period in days.

After the first injection, CH4 (20 ml) and O2 (10 ml) were repeatedly injected to maintain low O2 (3 to 5%) and excess CH4 (10 to 15%) concentrations.

Another general observation was that when cultured under various conditions, the groundwater community was a stable association consisting of one obligate methanotroph and four heterotrophs. One additional heterotrophic population was occasionally observed, especially when the community was cultured under conditions optimal for its growth in shake flasks (CH4, 10 to 15%; O2, 3 to 5%). Evaluation of the community structure (Table 2) showed that most of the enriched communities harvested in the early stationary phase were dominated by the methanotroph, which, depending on methane and oxygen concentrations (CH4, 4.5 to 19.4%; O2, 15.5 to 19%), represented 50 to 85% of the total population. When cultured under low oxygen (3 to 5%) and excess methane (10 to 15%) concentrations, where optimal growth of the community was achieved, an even higher proportion of methanotrophs (approximately 90% of the total population) was obtained. The results presented in Table 2 also illustrate that among the heterotrophs, two species dominated and the remaining three species formed a small proportion of the total heterotrophic population. The community structure was surprisingly stable under different methane and oxygen concentrations, and only the relative proportions of the dominant heterotrophic populations were changed significantly by changing the incubation temperature.

TABLE 2.

Structure of the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community enriched under different methane and oxygen concentrations at 30°Ca

| Initial headspace concn

(%)

|

Compositionb (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | O2 | Met 1 | Het 1 | Het 2 | Het 3 | Het 4 | Het 5 |

| 4.5 | 19.0 | 50–60 | 45–55 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 35–45 | |

| 8.7 | 18.5 | 60–65 | 55–65 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 30–40 | |

| 19.4 | 15.5 | 65–85 | 50–60 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 25–35 | 1–5 |

| 20.2c | 14.8 | 80–90 | 45–55 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 35–45 | 5–10 |

Similar results were obtained at 20°C; only the relative proportions of the dominant heterotrophic populations changed significantly (Het 4 increased to approximately 55 to 70% and Het 1 decreased to approximately 20 to 35%).

Expressed as the proportion of the total population for the methanotroph (Met 1) and as the relative proportion of the heterotrophic population for individual heterotrophs (Het 1 through 5). At least three replicate plates with 100 to 150 colonies on NMS-agarose medium (for the methanotroph) or on nutrient agar (for heterotrophs) were evaluated.

After the first injection, CH4 (20 ml) and O2 (10 ml) were repeatedly injected to maintain low O2 (3 to 5%) and excess CH4 (10 to 15%) concentrations.

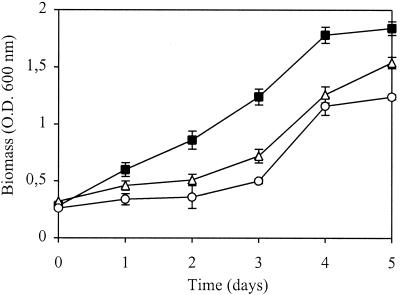

Comparative growth kinetics experiments performed with the methanotroph (strain Met 1) as a single culture showed that, similar to the community, this strain preferred the conditions of low oxygen concentrations (3 to 5%) and higher temperatures (30°C) over the conditions prevailing in the natural habitat (Table 1). However, under the same experimental conditions, its specific growth rate (μ = 0.45 ± 0.06 day−1) as a single culture was lower than when strain Met 1 was grown as part of the community (μ = 0.55 ± 0.03 day−1). To explore whether an accumulation of metabolites of methane oxidation may be one of the reasons for the impaired growth rate, further experiments with strain Met 1 were performed in which methanol (0.2 or 2.0 mmol liter−1) was added as a supplementary carbon source. Since the growth of strain Met 1 was typically suppressed in the presence of methanol, even at a lower concentration (0.2 mmol liter−1) and especially under conditions where its optimal growth was achieved (Fig. 1), the hypothesis of a self-inhibitory growth effect due to methanol as a product of methane oxidation seems very likely.

FIG. 1.

Growth of the methanotroph (strain Met 1) in the presence of methanol as a supplementary carbon source under microaerobic conditions (O2, 3 to 5%) with excess methane (CH4, 10 to 15%) at 30°C. Symbols: ■, control (without methanol); ▵, methanol at 0.2 mM; ○, methanol at 2 mM. The data are means ± standard deviations from triplicate bottles.

Some general nutritional and physiological properties of the isolated heterotrophic populations relevant for the evaluation of possible relationships and interactions within the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community are summarized in Table 3. It is evident that only one heterotroph (Het 3) exhibited the capability to grow on NMS medium, while all other heterotrophs required the addition of a carbon source and grew well on oligotrophic media (PY and PYG) containing low concentrations (0.025%) of peptone, yeast extract, and glucose. None of the heterotrophs was able to use methane as the only carbon and energy source. These results suggested that when cultured in NMS medium with methane as the only carbon and energy source, the presence of all heterotrophs except strain Het 3 was dependent on the growth and metabolic activity of the methanotroph. Furthermore, despite some similarities among the heterotrophs (all of them are obligately aerobic and chemo-organotrophic), individual heterotrophs differed according to their growth factor requirements, utilization of methanol as the only carbon source, and preferences of nitrogen sources, which suggested their different metabolic activities in the community.

TABLE 3.

General nutritional and physiological characteristics of heterotrophic community populationsa

| Characteristic | Het 1 | Het 2 | Het 3 | Het 4 | Het 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth on: | |||||

| Rich medium (NA)b | + | + | + | − | + |

| Oligotrophic mediac | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mineral medium (NMS) | − | − | + | − | − |

| Optimal temp (°C) | 30–32 | 28–30 | 28–30 | 20–25 | 28–30 |

| Growth factor requirements | |||||

| Vitaminsd | − | − | + | + | + |

| Amino acidse | + | + | − | + | + |

| Utilization of carbon sources | |||||

| Methanol | + | − | − | + | + |

| Formate | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acetate | + | + | + | − | − |

| Utilization of nitrogen sources | |||||

| NO3− | + | − | + | + | − |

| NH4+ | + | + | + | + | + |

| Urea | + | + | + | + | + |

| LAS transformation | − | − | − | − | − |

| C10SPCf transformation | + | + | + | − | − |

Three strains were tentatively identified as members of the genera Blastobacter (Het 1), Pseudomonas (Het 2), and Xanthobacter (Het 3), and two unidentified strains (Het 4 and Het 5) showed similarities to prosthecate bacteria (24).

NA, nutrient agar (Difco).

PY agar and PYG agar.

Biotin, folic acid, and thiamine hydrochloride.

Vitamin-free Casamino Acids (Difco).

C10SPC, sulfophenyldecanoic acid (a LAS intermediate).

Growth stimulation and inhibition effects between community populations.

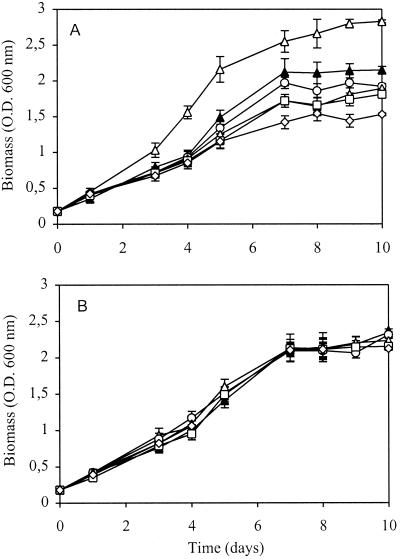

To study possible interactions based on the modification of growth activities of individual community populations, a series of experiments was carried out by cross-growing the methanotrophic strain in the presence of individual heterotrophs and their lysates. Some of the obtained results are presented in Fig. 2. It is evident that when grown under microaerobic conditions and with excess methane (O2, 3 to 5%; CH4, 10 to 15%), only one heterotroph (unidentified strain Het 4) stimulated the growth of strain Met 1, while the other heterotrophs suppressed its growth (Fig. 2A). Similar experiments performed under aerobic conditions (O2, 15 to 18%; CH4, 15 to 18%) (results not presented) showed that all heterotrophs stimulated the growth of strain Met 1. In contrast, none of the filter-sterilized autolysates of the heterotrophic strains stimulated the growth of strain Met 1 under either microaerobic (Fig. 2B) or aerobic conditions (results not presented). These results suggested that the growth of the methanotrophic strain may not be dependent on specific substances (nutrients or growth factors) excreted by the heterotrophs; however, it was affected by their growth and metabolic activities. Most of these heterotrophic activities stimulated the growth of the methanotrophic strain, while the suppressed growth under microaerobic conditions suggested that some negative relationships (competition for nutrients and oxygen) may also exist between the community populations.

FIG. 2.

Growth of strain Met 1 in the presence of individual heterotrophic members (A) and their lysates (B). Experimental conditions are the same as for Fig. 1. Symbols: ▴, control (strain Met 1 alone); ▵, Met 1 and Het 4; ○, Met 1 and Het 5; ▿, Met 1 and Het 1; □, Met 1 and Het 3; ◊, Met 1 and Het 2. The data are means ± standard deviations from triplicate bottles.

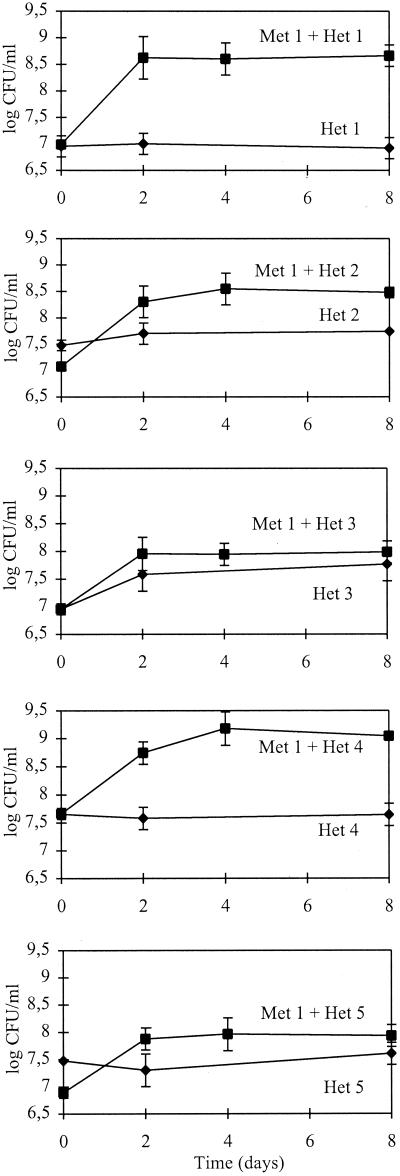

Significantly stimulated growth of four of the five heterotrophs (i.e., all except strain Het 3) in the presence of either strain Met 1 (Fig. 3) or its lysate (results not presented) suggested that the most probable role of the methanotrophic strain when grown in the community may be in providing the heterotrophs with a carbon source or specific nutrients necessary for growth in mineral medium with addition of methane as the only carbon source.

FIG. 3.

Growth of individual heterotrophs (Het 1 through 5) in the presence of the methanotroph (strain Met 1). The initial concentration of Met 1 was 5 × 108 CFU/ml. For comparison, growth curves of individual heterotrophic populations in NMS medium are also shown. The data are means ± standard deviations from triplicate bottles.

LAS transformation activity of the groundwater community and its individual populations.

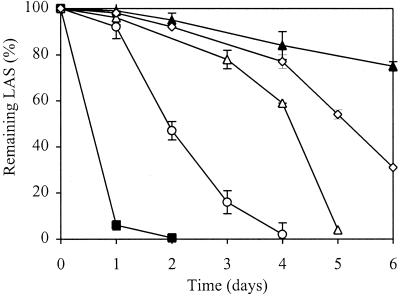

To explore the hypothesis of concerted metabolic activity of individual community populations on complex organic LAS compounds that was suggested in previous studies (21, 22, 24), further comparative transformation experiments with a pure LAS congener, 2C10LAS, were performed with the original six-member groundwater community, its methanotrophic strain (Met 1) as a pure culture, and two-member reconstructed communities containing strain Met 1 and one of the heterotrophic strains known to possess the enzyme system for β-oxidation (Het 1, Het 2, and Het 3). The results (Fig. 4) confirmed the previous observation of fast 2C10LAS transformation with the original community (within 1 day) and very slow 2C10LAS disappearance (within 20 days) with the methanotroph as a pure culture. Furthermore, although slower than with the original community, LAS disappearance with all reconstructed communities (Met 1 and Het 1, 5 days; Met 1 and Het 2, 7 days; and Met 1 and Het 3, 4 days) was faster than LAS disappearance with the methanotroph as a single culture; this finding supported the hypothesis of combined metabolic attack on the complex LAS molecule.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of 2C10LAS transformation (determined by reversed-phase-HPLC) by the original six-member groundwater community, two-member reconstructed communities, and the methanotroph as a single culture. Symbols: ■, original community; ○, Met 1 and Het 3; ▵, Met 1 and Het 1; ◊, Met 1 and Het 2; ▴, Met 1 alone. The data are means ± standard deviations from triplicate bottles; in some cases, the standard deviations were too small to illustrate.

DISCUSSION

The results presented in this work and previous papers (22, 24) showed that the groundwater community was a tight association containing one obligate methanotroph (strain Met 1) and, depending on experimental conditions, four or five heterotrophic strains (Het 1 through 5), possessing different metabolic activities. Based on cell morphology, the resting stages formed, the intracytoplasmic membranes, and some physiological characteristics, strain Met 1 was tentatively identified as a type II methanotroph. This was confirmed by further characterization, including the determination of fatty acid methyl ester profiles and 16S rRNA analyses, which suggested the similarity of strain Met 1 with the most studied and characterized type II methanotroph, Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (37). On the basis of the nutritional, morphological, and physiological characteristics of the isolated heterotrophic populations presented here and discussed in a previous paper (24), three of the heterotrophs were tentatively identified as members of the genera Blastobacter (Het 1), Pseudomonas (Het 2), and Xanthobacter (Het 3), while two still-unidentified strains (Het 4 and Het 5) showed similarities to prosthecate bacteria.

In addition to the previously reported efficiency in cometabolic transformation of trichloroethylene (17, 18) and chlorinated biphenyls (1, 37), the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community also exhibited the capability to transform LAS (21, 22, 23). This metabolic activity was evaluated on the basis of intensive transformation studies of commercial LAS and pure LAS congeners in the presence or absence of methane as the primary carbon and energy source. The methanotrophic-heterotrophic community exhibited transformation activity on different LAS molecules under various environmental conditions (aerobic and microaerobic), with or without methane addition. The main proposed mechanism was the initiation of LAS transformation on the alkyl side chain by ω-oxidation, followed by the shortening of the chain by β-oxidation. Further experiments, in which possible LAS transformation activities of individual community members were determined, suggested that only strain Met 1 had the capability of LAS transformation (24). The failure of this strain to transform sulfophenyldecanoic acid as the product of ω-oxidation and the observed ability of three heterotrophic strains (Het 1, Het 2, and Het 3) to transform this first LAS intermediate by β-oxidation suggested that the methanotroph could be involved in the initiation of LAS transformation, and some of the heterotrophs could be involved in the continuation of LAS transformation. This hypothesis of metabolic cooperation between community populations for LAS transformation was further supported by the results presented in Fig. 4, which illustrated faster LAS disappearance with the original six-member community and two-member reconstructed communities than with the methanotroph as a single culture.

Possible interactions within methanotrophic-heterotrophic community.

Stable growth characteristics of the six-member groundwater community (Table 1), with almost regular appearance of all populations under various conditions (Table 2), illustrated the capacity of the community to self-regulate in response to changing environmental conditions. This also suggested that the groundwater community was structured on specific relationships between the obligate methanotroph and the heterotrophs, with their different nutritional requirements and metabolic activities. Furthermore, unstable growth characteristics (occasionally prolonged [1 to 5-days] lag phase, or oscillations in the growth rate) and impaired specific growth rates of strain Met 1 when grown as a single culture compared to its growth in the community (Table 1) suggested interactions which conferred beneficial effects on the interacting populations. Thus, the most likely explanation for stimulated growth of strain Met 1 in the community may be that the heterotrophs removed self-inhibitory organic compounds excreted by the methanotroph. This is likely, since obligate methanotrophs are known to be sensitive to amino acids and products of methane oxidation (16, 33), and growth of strain Met 1 was found to be inhibited by methanol added as a supplementary carbon source (Fig. 1). In addition, three of the five isolated heterotrophic strains (Het 1, Het 4, and Het 5) were able to use methanol and all heterotrophs used formate, both of which are products of methane oxidation (Table 3). The accumulation of self-inhibitory products excreted by the methanotroph may be less expected in an open system, but according to the available literature (15, 16, 30), much faster growth of methanotrophs is achieved in an open system than in a closed system, typically with accumulation of methanol as an intermediate of methane oxidation.

Another possible explanation for the faster and more stable growth of the methanotrophic strain in the community rather than as a single culture is that specific substances (nutrients or growth factors) excreted by the heterotrophs affected the methanotroph's growth. This explanation is less probable, since none of the filter-sterilized autolysates of the heterotrophs showed growth stimulation of this strain under either microaerobic or aerobic conditions.

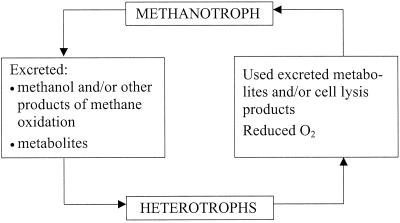

The most probable beneficial relationships between strain Met 1 and the heterotrophs, when grown in the community in the presence of methane as a carbon and energy source, are summarized in Fig. 5. The methanotroph, the only member able to oxidize methane, excreted methane oxidation products and metabolites which may be used by heterotrophs as a carbon source or as growth factors. The heterotrophs in turn removed excreted organic compounds which may be inhibitory for the methanotroph. Thus, the removal of excreted compounds from culture liquid may be mutually beneficial for the methanotroph and heterotrophs. Another probable beneficial effect of the heterotrophs may be in reducing oxygen tension, thus making more favorable conditions for growth of the methanotrophic strain, which preferred microaerobic conditions (3 to 5% O2 in the headspace).

FIG. 5.

General scheme of the probable beneficial effects within the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community when grown in NMS medium with the addition of methane as the only carbon and energy source.

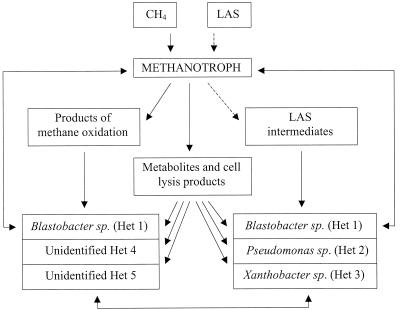

The scheme presenting the most likely beneficial interactions within the methanotrophic-heterotrophic groundwater community (Fig. 5) seems rather simple. However, in this community, in which one obligate methanotroph and four or five heterotrophs of different nutritional and metabolic capabilities coexist, a number of interactions and relationships might exist between the populations which enable their remaining in the community under conditions favorable only for the growth of the methanotroph. The situation was much more complex when the groundwater community was cultured in the presence of both methane as a primary substrate and LAS as a cometabolic substrate. In this case, as schematically presented in Fig. 6, along with the products of methane oxidation there were also LAS intermediates, which may cause additional nutritional and growth modification relationships between the community populations. Although the relationships and interactions between individual populations are not yet fully understood, it can be proposed that the methanotroph, as the only member able to oxidize methane and cometabolically initiate LAS transformation, excreted methane oxidation products and LAS intermediates which may serve as carbon sources or growth factors for the heterotrophs. Based on the nutritional and physiological characteristics of individual heterotrophic populations (Table 3), the products of methane oxidation might theoretically sustain the growth of all five heterotrophs, since they were able to use formate and at least three of them (Het 1, Het 4, and Het 5) were able to use methanol as their carbon source. On the other hand the growth of the three heterotrophic populations (Het 1, Het 2, and Het 3) capable of transforming sulfophenyldecanoic acid may be sustained by LAS intermediates, suggesting their possible involvement in the continuation of LAS transformation.

FIG. 6.

Scheme of possible interactions within the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community in the presence of methane as the carbon source and LAS as a cometabolic substrate. →, substrate utilization associated with growth; →, cometabolic transformation not linked to growth.

A general conclusion which can be drawn from the results of this study is that in the six-member methanotrophic-heterotrophic community, a number of complex interactions may exist between community populations. The most probable interactions are those based on the provision of specific nutrients, the removal of inhibitory compounds, the mutual modification of basic growth parameters, and the metabolic cooperation for the combined attack on complex LAS molecules. Most of these relationships, some of which are obligatory and reciprocal for the interacting populations, confer beneficial effects, making the community stable and adaptable to various environmental conditions and more efficient in LAS transformation than any of the individual populations alone. In addition to these mutually beneficial effects, some negative interactions (competition for oxygen and/or nutrients) may also exist within this specific and complex groundwater community under particular environmental conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Croatian Ministry of Science and Technology.

We are grateful to Angela S. Lindner from the Department of Environmental Engineering Sciences, University of Florida, for her valuable cooperation in the characterization of the methanotrophic-heterotrophic community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adriaens P, Grbić-Galić D. Cometabolic transformation of mono- and dichlorobiphenyls and chlorohydroxylic phenyls by methanotrophic groundwater isolates. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:1325–1330. doi: 10.1021/es00056a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Cohen L. Application of methanotrophic bacteria for the bioremediation of chlorinated organics. In: Murrell J C, Kelly D P, editors. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Andover, United Kingdom: Intercept Press, Ltd.; 1993. pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral J A, Archambault C, Richards S R, Knowles R. Denitrification associated with groups I and II methanotrophs in a gradient enrichment system. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony C. The biochemistry of methylotrophs. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Ltd.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aziz C E, Georgiou G, Speitel G E. Cometabolism of chlorinated solvents and binary chlorinated solvent mixtures using M. trichosporiumOB3b PP358. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;65:100–107. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19991005)65:1<100::aid-bit12>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman J P, Jiménez L, Rosario I, Hazen T C, Sayler G S. Characterization of the methanotrophic bacterial community present in a trichloroethylene-contaminated subsurface groundwater site. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2380–2387. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2380-2387.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brusseau G A, Bulygina E S, Hanson R S. Phylogenetic analysis and development of probes for differentiating methylotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:626–636. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.626-636.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H L, Alvarez-Cohen L. Transformation capacities of chlorinated organics by mixed cultures enriched on methane, propane, toluene, or phenol. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;45:440–449. doi: 10.1002/bit.260450509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colby J, Stirling D I, Dalton H. The soluble methane monooxygenase of Methylococcus capsulatus(Bath). Its ability to oxygenate n-alkanes, n-alkenes, ethers, and alicyclic, aromatic and heterocyclic compounds. Biochem J. 1977;165:395–402. doi: 10.1042/bj1650395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad R. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO) Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:609–640. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.609-640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Visscher A, Dirk T, Boeckx P, Van Cleemput O. Methane oxidation in simulated landfill cover soil environments. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33:1854–1859. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunfield P F, Liesack W, Henckel T, Knowles R, Conrad R. High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1009–1014. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1009-1014.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ensley B S. Biochemical diversity of trichloroethylene metabolism. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:283–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox B G, Lipscomb J D. Methane monooxygenase: a novel biological catalyst for hydrocarbon oxidation. In: Reddy C C, Hamilton G A, Madyastha M K, editors. Biological oxidation systems. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 367–388. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox B G, Froland W A, Jollie D R, Lipscomb J D. Methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b. Methods Enzymol. 1990;188:191–202. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)88033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:439–471. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry S M, Grbić-Galić D. Effect of mineral media on trichloroethylene oxidation by aquifer methanotrophs. Microb Ecol. 1990;20:151–169. doi: 10.1007/BF02543874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry S M, Grbić-Galić D. Influence of endogenous and exogenous electron donors and trichloroethylene oxidation toxicity on trichloroethylene oxidation by methanotrophic cultures from a groundwater aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:236–244. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.236-244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins I J, Best D J, Hammond R C. New findings in methane-utilizing bacteria highlight their importance in the biosphere and their commercial potential. Nature. 1980;286:561–564. doi: 10.1038/286561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes A J, Owens N J P, Murrell J C. Detection of novel marine methanotrophs using phylogenetic and functional gene probes after methane enrichment. Microbiology. 1995;141:1947–1955. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-8-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hršak D. Biodegradation of undecylbenzenesulphonate by mixed methane-oxidizing culture. Environ Pollut. 1995;89:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(94)00073-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hršak D, Grbić-Galić D. Biodegradation of linear alkylbenzene-sulphonates (LAS) by mixed methanotrophic-heterotrophic cultures. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;78:487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hršak D. Cometabolic transformation of linear alkylbenzene-sulfonates by methanotrophs. Water Res. 1996;30:3092–3098. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hršak D, Begonja A. Growth characteristics and metabolic activities of the methanotrophic-heterotrophic groundwater community. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:448–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.853505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen D, Grobben B G, Witholt B. Toxicity of chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons and degradation by methanotrophic consortia. In: Neijssel O N, Van der Meer R R, Luyben K C, editors. Proceedings of the 4th European Congress on Biotechnology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Biomedical Press; 1987. pp. 515–518. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen S, Ovreas L, Daae F L, Torsvik V. Diversity in methane enrichment from agricultural soil revealed by DGGE separation of PCR amplified 16S rRNA fragments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;26:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancinelli R L. The regulation of methane oxidation in soil. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:581–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarty P L. Bioengineering issues related to in-situ remediation of contaminated soils and groundwater. In: Omenn G S, editor. Environmental biotechnology: reducing risks from environmental chemicals through biotechnology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 143–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFarland M J, Vogel C M, Spain J C. Methanotrophic cometabolism of trichloroethylene (TCE) in a two stage bioreactor system. Water Res. 1992;26:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldenhuis R, Janssen D B. Degradation of trichloroethylene by methanotrophic bacteria. In: Murrell J C, Kelly D P, editors. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Andover, United Kingdom: Intercept Press, Ltd.; 1993. pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. Some properties and taxonomic subdivisions of the genus Pseudomonas. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1972;10:73–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry J J. Microbial cooxidations involving hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:59–72. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.1.59-72.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slater J H, Lovatt D. Biodegradation and the significance of microbial communities. In: Gibson D T, editor. Microbial degradation of organic compounds. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1984. pp. 439–484. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith K S, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E. Methane and trichloroethylene oxidation by an estuarine methanotroph, Methylobactersp. strain BB5.1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4617–4620. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4617-4620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staley J T. Prosthecomicrobium and Ancalomicrobium: new prosthecate freshwater bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:1921–1942. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.5.1921-1942.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanier R Y, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;43:159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson-Lindner A. Methanotrophic oxidation of substituted aromatic compounds: a mechanistic approach to biodegradation and quantitative structure-activity relationships. Ph.D. thesis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan J P, Dickinson D, Chase H A. Methanotrophs, Methylosinus trichosporiumOB3b, sMMO, and their application to bioremediation. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1998;24:335–373. doi: 10.1080/10408419891294217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whittenbury R, Phillips K C, Wilkinson J F. Enrichment, isolation, and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;24:225–233. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]