MtGSTF7, a TT19-like GST gene, is activated by the transcription factor LAP1 to determine the accumulation of anthocyanins, but not proanthocyanins in Medicago truncatula.

Keywords: Anthocyanin, glutathione-S-transferase, LAP1, Medicago truncatula, MtGSTF7, proanthocyanidin

Abstract

Anthocyanins and proanthocyanins (PAs) are two end products of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. They are believed to be synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and then sequestered into the vacuole. In Arabidopsis thaliana, TRANSPARENT TESTA 19 (TT19) is necessary for both anthocyanin and PA accumulation. Here, we found that MtGSTF7, a homolog of AtTT19, is essential for anthocyanin accumulation but not required for PA accumulation in Medicago truncatula. MtGSTF7 was induced by the anthocyanin regulator LEGUME ANTHOCYANIN PRODUCTION 1 (LAP1), and its tissue expression pattern correlated with anthocyanin deposition in M. truncatula. Tnt1-insertional mutants of MtGSTF7 lost anthocyanin accumulation in vegetative organs, and introducing a genomic fragment of MtGSTF7 could complement the mutant phenotypes. Additionally, the accumulation of anthocyanins induced by LAP1 was significantly reduced in mtgstf7 mutants. Yeast-one-hybridization and dual-luciferase reporter assays revealed that LAP1 could bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter to activate its expression. Ectopic expression of MtGSTF7 in tt19 mutants could rescue their anthocyanin deficiency, but not their PA defect. Furthermore, PA accumulation was not affected in the mtgstf7 mutants. Taken together, our results show that the mechanism of anthocyanin and PA accumulation in M. truncatula is different from that in A. thaliana, and provide a new target gene for engineering anthocyanins in plants.

Introduction

Anthocyanins and proanthocyanins (PAs) are two classes of flavonoids possessing benefits for human health (Butelli et al., 2008; Lila et al., 2016). In addition, the accumulation of anthocyanins can protect plants against various biotic and abiotic stresses, and provide colourful hues for plants to attract pollinators and seed dispersers (Zhang et al., 2014; Saigo et al., 2020). In forage crops, moderate accumulation of PAs protects ruminant animals from pasture bloat and improves the absorption of essential amino acids in the ruminant’s rumen (Dixon et al., 2005).

The biosynthesis of anthocyanins and PAs shares a common upstream biosynthetic pathway (Dixon et al., 2013). The proteins regulating their biosynthesis, namely the ternary MBW (MYB-bHLH-WD40) protein complexes, are conserved in higher plants. In this complex, the MYB transcription factor plays a crucial role in determining the activation of specific downstream genes to control the spatiotemporal accumulation of anthocyanins and PAs (Albert et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2014; N. Lu et al., 2021). Generally, activation or overexpression of these MYB activators alone, or coupled with a bHLH member, can strikingly promote anthocyanin and PA accumulation (Borevitz et al., 2000; Butelli et al., 2008; Peel et al., 2009; Hancock et al., 2012; Dixon et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2020; N. Lu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). In the model legume M. truncatula, three anthocyanin biosynthetic MYB activators, LAP1, WHITE PETAL1 (WP1) and RED HEART1 (RH1), have been identified to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis by activating anthocyanin biosynthetic genes (Peel et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Among them, WP1 and RH1 specifically regulate anthocyanin accumulation in petal and leaf, respectively (Meng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Constitutively or transiently overexpressing LAP1 could massively induce the ectopic accumulation of anthocyanins in M. truncatula (Peel et al., 2009; Picard et al., 2013; Bond et al., 2016).

Anthocyanins and PAs are believed to be synthesized on the cytoplasmic face of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by a conserved multi-enzyme complex that is anchored by the cytochrome P450 enzyme family members cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) and flavonoid 3´ hydroxylase (F3´H; Winkel, 2004; Zhao and Dixon, 2010), and are finally sequestered into the vacuole to prevent their oxidation in the cytoplasm, and to fulfil their function as pigments (Grotewold and Davies, 2008; Zhao and Dixon, 2010; Zhao, 2015). Compared with the well-studied transcriptional regulation mechanisms, the in vivo sequestration of anthocyanins and PAs is still poorly understood (Zhao, 2015), especially in legume species. Previously, two MULTIDRUG AND TOXIC COMPOUND EXTRUSION (MATE) transporters, Medicago MATE2 and MATE1, had been identified that participate in anthocyanin and PA sequestration (Zhao and Dixon, 2009; Zhao et al., 2011). However, anthocyanins and PAs could still be detected in mate2 and mate1 mutants, indicating that there must be other members collaboratively involved in anthocyanin and PA sequestration (Zhao and Dixon, 2009; Zhao et al., 2011). It has been accepted that two sequential steps, the delivery from the surface of the ER to the surrounding tonoplast, and the transmembrane transport across the tonoplast, are required for plants to eventually sequester anthocyanins into the vacuole (Grotewold and Davies, 2008; Zhao, 2015). To date, two kinds of non-overlapping transport models, vesicle-mediated trafficking and glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-mediated transport, have been proposed to be responsible for the first step of anthocyanin and PA transport (Grotewold and Davies, 2008; Zhao, 2015). Vesicle-mediated trafficking is supported by observations of the presence of anthocyanoplasts in the cytoplasm (Zhang et al., 2006; Poustka et al., 2007; Gomez et al., 2011). The GST-mediated transport model is based on the characterization of BZ2 in maize and the identification of AtTT19 in Arabidopsis thaliana (Marrs et al., 1995; Kitamura et al., 2004). AtTT19 is a plant-specific phi class GST that is necessary for both anthocyanin and PA accumulation (Kitamura et al., 2004). In tt19 mutants, anthocyanin accumulation was not visible, and the seed coat colour was pale at the ripening stage due to the defect of anthocyanin and PA accumulation (Kitamura et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2012). In recent years, several TT19 homologs have been identified and characterized in many plants, all of which are considered to be essential for anthocyanin accumulation (Conn et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Z. Lu et al., 2021). Whether TT19-like GST is recruited to participate in PA accumulation in other plants is still unclear.

In this study, through analysis of previous transcriptomic data, expression pattern detection, phenotypic analysis of knockout mutants, and genetic complementation assays, we demonstrate that MtGSTF7, a TT19-like GST, is necessary for anthocyanin accumulation in the model legume M. truncatula. Finally, we show that LAP1 can bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter to activate its expression, and that MtGSTF7 does not control PA accumulation, as does its Arabidopsis orthologue.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

M. truncatula wild type (WT) R108 seeds were obtained from the Noble Research Institute, Ardmore, OK, USA. The mtgstf7 mutants were ordered from the M. truncatula Tnt1 mutant database (https://medicago-mutant.dasnr.okstate.edu/mutant/index.php) with the numbers NF2357 and NF10672. For greenhouse cultivation, the seeds were gently scarified by rubbing them between two pieces of sandpaper, then transferred to water in petri dishes and placed at 4 °C, in the dark for 3–5 d to allow germination. To obtain sterile plants, the M. truncatula seeds were soaked in concentrated anhydrous sulfuric acid in a 2 ml Eppendorf tube and then shaken for 6–8 min to scarify the seed coat. After removing the H2SO4 and rinsing the seeds with chilled water 3–5 times, 3% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution was added to sterilize the scarified seeds for 8–10 min.

Plants used in this study were grown under controlled greenhouse conditions with a mean temperature of 22 °C, 16 h/8 h photoperiod and suitable humidity. For induced anthocyanin accumulation, 3-day-old seedlings were grown under high intensity light (HL) at an average of 252-270 µmol m-2 s-1 for 4 d. Light under control (CT) conditions was 126-135 µmol m-2 s-1. The light intensity was measured with a Digital Lux Meter (SMART SENSOR, AS813, China).

Comparative analysis of the transcriptomic datasets

The normalized transcriptomic data of Peel et al. (2009) were downloaded from ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/) with the accession number E-MEXP-1854. Firstly, the microarray IDs were converted to V4.0 gene IDs based on the mapping file (Supplementary Table S1). Then, the significant DEGs (differentially expressed genes) induced by LAP1 were screened out based on the log2FC values (FC value = RMALAP1/RMAGUS; RAM is the normalized value analysed by Peel et al., 2009) ≧1 and P value≧0.05; (Supplementary Table S2). The transcriptomic dataset of Bond et al. (2016) was downloaded from (https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2Fs13007-016-0141-7/MediaObjects/13007_2016_141_MOESM1_ESM.xlsx) and the original data were downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with accession number SRP091342. In the released list of significant DEGs by Bond et al., 2016, values for each individual data set were log2-transformed normalized counts (Supplementary Table S3). To avoid the deviation caused by different sequencing and analytical techniques, we used the log2FC values of DEGs for further analysis. The DEG IDs and their corresponding log2FC values in Peel et al. (2009) and Bond et al. (2016) datasets (Supplementary Table S4) were used to plot the Venn diagram and clustering heatmap using the TBtools software (Chen et al., 2020).

Gene expression atlas analysis

Expression atlases of target genes were retrieved from the previously released processed GeneChip Array data (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/files/E-MEXP-1097/E-MEXP-1097.processed.1.zip;Benedito et al., 2008). The corresponding probe IDs of target genes were queried in the mapping file (Supplementary Table S5) and the tissue expression of genes was displayed with the average values of Affymetrix: CHPSignal.

Observation of anthocyanin autofluorescence

Images were captured with a laser scanning confocal microscope (TCS SP8 X, Leica, Germany). Anthocyanin autofluorescence was captured at the emission spectrum between 610–650 nm after excitation at 541 nm.

Pigment extraction, HPLC and measurement of anthocyanins

Accurately weighed tissues were ground into powder in 1.5 ml tubes after freezing in liquid nitrogen, and pigment extraction solution (methanol containing 0.1% HCl) was added. After vortexing and centrifugation, the residues were re-extracted until the supernatants were colourless. The supernatants were pooled as crude extract for the following analysis.

For HPLC analysis, an equal volume of double-deionized water and chloroform was added to the pooled supernatant to remove the chlorophyll. After centrifugation, the aqueous supernatant was dried in a vacuum freeze drier, and the dried samples were resuspended in methanol for HPLC separation. HPLC separation was performed on an Agilent LC1260 infinity II HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, USA) with a reverse phase, Biphenyl, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm column (Phenomenex Kinetex, USA) and elution with solution A (0.2% phosphoric acid) and solution B (acetonitrile) at 1 ml min-1 flow rate. The elution gradient was as follows: 0–2 min, 5–10% solution B; 2–10 min, 10–18% solution B; 10–14 min, 18–20% solution B; 14–18 min, 20–22% solution B; 18–22 min, 22–40% solution B; 22–24 min, 40–100% solution B. The absorbance was detected at 530 nm. To measure the anthocyanin content, cyanidin chloride was used to construct a standard curve and the anthocyanin content was calculated as standard equivalents.

Analysis of PAs

To qualitatively estimate PA content, mature seeds were stained overnight in 0.1% (w/v) DMACA reagent (p-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde dissolved in methanol-3N HCl) and then washed with ethanol: acetic acid (75:25) three times before observation.

The extraction and quantitative detection of PAs were performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2016; Jun et al., 2021). Briefly, about 0.05 to 0.1 g dry seeds were accurately weighed and ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. The powders were extracted four times with 6 ml PA extraction solution (70% acetone/0.5% acetic acid, v/v) by vortexing and sonicating at room temperature (~ 25–30 °C) for 30 min until the residues were white. The residues (containing insoluble PAs) were lyophilized and the pooled supernatants were further extracted three times with equal volumes of chloroform, and twice with hexane. The resulting aqueous phase (containing soluble PAs) was lyophilized and resuspended in 100 µl PA extraction solution.

The soluble PA content was measured by the DMACA method. For this, 1 µl soluble PA was made to react with 0.2% (w/v) DMACA regent, and the absorbance at 640 nm was recorded after 5 min. Epicatechin was used as the standard to construct a standard curve, and the absorbance values were converted into epicatechin equivalents. The insoluble PA content was quantified by the butanol/HCl method as described previously (Pang et al., 2007). Standard curves of epicatechin and procyanidin B1 are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Total RNA extraction, RT–PCR, and qRT–PCR

Total RNA from the infiltrated leaves was extracted to detect the expression of genes in the transient expression assay. The total RNA from different tissues of WT was extracted to detect the tissue expression pattern of MtGSTF7 in M. truncatula. The total RNA from hypocotyls of WT and mtgstf7 mutants was extracted to detect the expression of MtGSTF7 and anthocyanin biosynthesis genes. The total RNA from transgenic G. max hairy roots and leaves was extracted to detect the expression of soybean genes. The total RNA was isolated using an RNA simple Total RNA Kit (Tiangen, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and 2 µg total RNA was subsequently used for reverse transcription. The first-strand cDNAs were reverse transcribed using the HiScript® II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper; R212; Vazyme, China). The cDNAs corresponding to 200 ng RNA were then used as templates for qRT–PCR and RT–PCR. The relative transcript levels of genes were calculated by the 2-∆Ct method. MtACTIN and MtGAPDH were used as internal reference genes for analysing the qRT–PCR data for M. truncatula. AtEF1a and AtACTIN2 was used as internal reference gene for analysing the qRT–PCR data for A. thaliana. GmCONS4 (CONSTITUTIVE GENES 4) and GmACTIN was used as internal reference gene for analysis of the qRT–PCR data in G. max. For RT–PCR, 32 cycles were carried out to detect the gene transcripts. Primer information is listed in Supplementary Table S6.

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

Complete coding sequences and different length MtGSTF7 promoters were amplified from WT cDNA and genomic DNA using Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (P505, Vazyme, China) and purified using the EasyPure Quick Gel Extraction Kit (EG101, TransGen, China). All of the plasmids were constructed using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (C112, Vazyme, China) and all the final constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

For analysis of the sub-cellular localization of MtGSTF7, the MtGSTF7 coding sequence without the stop codon was inserted into the pYS22 vector between the XhoI and KpnI restriction enzymes sites to generate the pro35S::cMtGSTF7-GFP construct. The construct was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 strain to be introduced into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves via the underside of the leaf. The pYS22 vector was used as the positive control. GFP and MtGSTF7-GFP fluorescence was examined using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000, Olympus, Japan).

For complementation of Arabidopsis tt19 mutants, the pCAMBIA3301 vector was digested by NcoI and BstEII (Eco91I), and the complete MtGSTF7 coding sequence was cloned into the linearized vector to generate the pro35S::cMtGSTF7 construct. The construct was then transformed into A. tumefaciens EHA105 strain and introduced into tt19-7 and tt19-8 via the floral dip method. The positive transgenic plants were screened by spraying with 20 mg l-1 Basta and confirmed by PCR analysis.

For genetic complementation of MtGSTF7, a 8070 bp MtGSTF7 genomic sequence (with a 4417 bp native promoter sequence and a 1500 bp 3´ untranslated region) was amplified using the Tks Gflex™ DNA Polymerase (R060, Takara, Japan). The genomic sequence of MtGSTF7 was inserted into the HindIII and Eco91I linearized pCAMBIA3301 vector to construct the proMtGSTF7::gMtGSTF7-3’UTR construct. The construct was then transformed into the A. tumefaciens EHA105 strain for stable transformation into mtgstf7-1, as described previously (Cosson et al., 2006). The positive transgenic plants were confirmed by genotyping and RT–PCR for the presence of MtGSTF7. All primers sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

Transient gene expression in M. truncatula

The complete LAP1 coding sequence was cloned into the pCAMBIA3301 vector to create the pro35S::cLAP1 construct, which was transferred into A. tumefaciens strain EHA105. The primer sequence is listed in Supplementary Table S6. The transformed A. tumefaciens was inoculated into LB liquid medium with 100 µg ml-1 kanamycin and incubated at 28 °C on a shaker overnight to reach OD600 of 1.0 to 2.0. The culture was centrifuged at 4500 ×g for 10 min and the pellet re-suspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM NaCl, 1.75 mM CaCl2, 2 µl Tween-20, 100 mM acetosyringone) to OD600 of 1.0 to 1.2. The third to fifth fully unfolded trifoliate leaves of 3–4 week-old healthy M. truncatula plants were selected for infiltration.

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay

To generate the prey vector AD-LAP1, the complete coding sequence of LAP1 was inserted into the pGADT7.1 vector (Clontech, Japan) between the BamHI and SmaI restriction enzymes sites. To construct the bait vector pABAi-proMtGSTF7, a 1982 bp MtGSTF7 upstream promoter sequence was spliced by overlap extension PCR to remove an 18 bp sequence that presents the BbsI restriction enzyme sites. Subsequently, the spliced sequence was cloned into the pABAi vector (Clontech). The Y1H assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the Matchmaker® Gold Yeast One-Hybrid System (PT4087, Clontech) and the Yeastmaker™ Yeast Transformation System 2 (PT1172, Clontech). Briefly, the bait vector was digested with BbsI and transformed into yeast strain Y1HGold to create the bait reporter strain. After confirmation by PCR, the positive bait reporter strain was grown on SD/-Ura media with different concentrations of Aureobasidin A (AbA) (50, 100, 200 and 300 ng ml-1) to determine the suitable inhibitory concentration. Then, the prey vector was transformed into the positive bait reporter strain to test the bait/prey interactions. The empty pABAi and pGADT7.1 vectors were used as controls. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

A 1924 bp MtGSTF7 upstream promoter sequence was cloned into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector between the PstI and NcoI restriction enzyme sites to create the reporter vector proMtGSTF7::LUC. After sequence confirmation, proMtGSTF7::LUC was transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 that contained the pSoup helper plasmid. The pro35S::cLAP1 and the empty vector pro35S::GUS (pCAMBIA3301) were used as the effector vectors. The A. tumefaciens reporter and effector strains were mixed at a ratio to 1:9 to infiltrate into N. benthamiana leaves, as described previously (Hellens et al., 2005). The luciferase activity was detected 2 d after infiltration. The primers sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

To analyse the luciferase activity, 1 mM D-luciferin, potassium salt (D8390, Solarbio, China) was evenly sprayed on the surface of N. benthamiana leaves. After reaction in the dark for 5–10 min, the fluorescence was captured. For quantitative detection analysis, the activities of firefly and Renilla luciferase were quantified using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (E1910, Promega, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and luminescence values were measured using a multifunctional microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, USA).

Results

MtGSTF7 is activated by LAP1 and its expression correlates with anthocyanin accumulation in M. truncatula

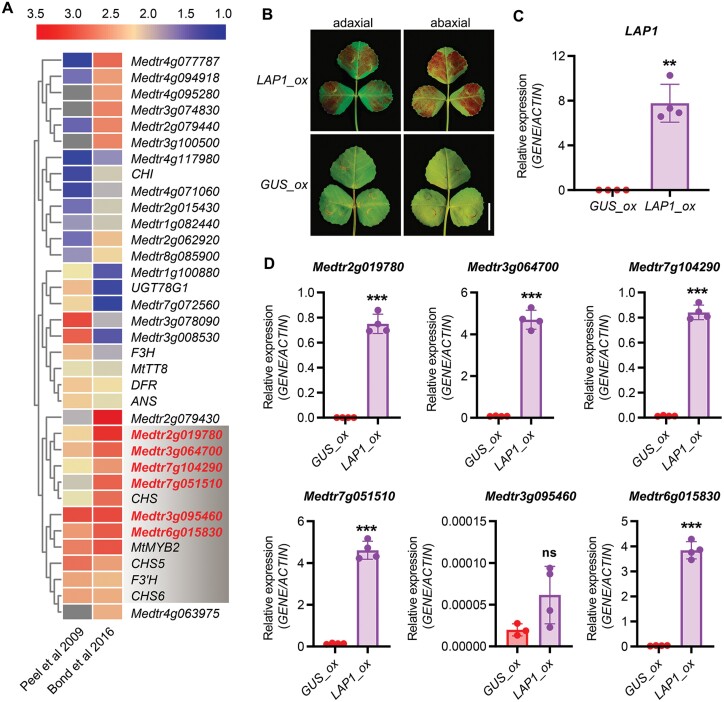

Two independent experiments showed extremely high level accumulation of anthocyanins in leaves overexpressing LAP1 (Peel et al., 2009; Bond et al., 2016), associated with the expression of anthocyanin-related genes. To further screen and identify anthocyanin accumulation-related genes, we compared two previously released transcriptome datasets (Peel et al., 2009; Bond et al., 2016) derived from leaves overexpressing LAP1 and focused on the common DEGs (|log2FC|≧1 and P value≦0.05). According to this comparison, we found 35 DEGs that were shared between these two transcriptomic datasets (Supplementary Fig. S2). A heatmap clustered by log2FC values of 35 common DEGs showed that 14 DEGs were remarkably up-regulated (log2FC≧3) in those two transcriptomic datasets, indicating that all of these genes were greatly induced by overexpressing LAP1 (Fig. 1A; Table 1). Apart from the six biosynthetic genes (CHS5, CHALCONE SYNTHASE 5; CHS6, CHALCONE SYNTHASE 6; CHS, CHALCONE SYNTHASE; F3´H, FLAVONOID 3’-HYDROXYLASE; DFR, DIHYDROFLAVONOL REDUCTASE; and ANS, ANTHOCYANIDIN SYNTHASE), and two transcription factors (TFs) identified previously (MtMYB2 and MtTT8), a further six genes (Medtr2g019780, Medtr3g064700, Medtr7g104290, Medtr7g051510, Medtr3g095460, and Medtr6g015830) caught our attention, and were selected for subsequent analysis (Fig. 1A; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Five common genes are highly induced in LAP1 overexpressing leaves. (A) The clustered heatmap based on the fold change values of 35 common DEGs. Genes in the grey-shaded region were highly induced (log2FC≧3) by overexpressing LAP1. (B) The adaxial and abaxial sides of ecotype R108 WT leaves transiently overexpressing LAP1 (LAP1_ox) and GUS (GUS_ox). The GUS gene was used as a negative control (GUS_ox). The experiment was conducted with three independent repeats with similar results. (C) The relative transcript levels of LAP1 in LAP1_ox and GUS_ox leaves determined by qRT–PCR (**P<0.01, two-tailed Welch’s t-test). The data are mean values ±SD (n=4). Similar results were acquired with two independent biological replicates. (D) The relative transcript levels of genes marked by red letters in the grey-shaded region in (A) verified by qRT–PCR (***P<0.001; ns, P>0.05; two-tailed Welch’s t-test).

Table 1.

The information of genes extremely activated by LAP1 (log2FC≧3 in two transcriptomic datasets).

| Gene IDs | log2FC in Peel et al (2009) | log2FC in Bond et al (2016) | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medtr3g095460 | 7.7006817 | 7.838319394 | nodulin MtN21/EamA-like transporter family protein |

| Medtr3g083910 (CHS5, chalcone synthase 5) | 6.589193019 | 5.260457267 | chalcone and stilbene synthase family protei |

| Medtr5g079670 (MtMYB2) | 6.077671733 | 7.443995756 | myb transcription factor |

| Medtr6g015830 | 5.4169854 | 7.264546709 | malonyl-CoA:isoflavone 7-O-glucoside malonyltransferase |

| Medtr3g083920 (CHS6, chalcone synthase 6) | 5.213524554 | 4.920912433 | chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein |

| Medtr4g109470 (F3’H, flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase) | 5.1542956 | 4.614758629 | flavonoid hydroxylase |

| Medtr3g064700 | 4.695889167 | 7.043531511 | glutathione S-transferase, amino-terminal domain protein |

| Medtr1g022445 (DFR, dihydroflavonol reductase) | 4.3313268 | 3.881723211 | dihydroflavonol 4-reductase |

| Medtr5g011250 (ANS, anthocyanidin synthase) | 4.264772867 | 3.394797924 | leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase-like protein |

| Medtr2g019780 | 4.122005946 | 8.7663448 | auxin-binding protein ABP19b |

| Medtr7g104290 | 3.822662247 | 5.490588201 | UAA transporter family protein |

| Medtr5g007730 (CHS, chalcone synthase) | 3.492184967 | 6.646533624 | chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein |

| Medtr1g072320 (MtTT8) | 3.4294313 | 3.218784057 | bHLH transcription factor |

| Medtr7g051510 | 3.0701301 | 7.023407627 | glycoside hydrolase family 1 protein |

To verify previous transcriptomic data, we transiently overexpressed LAP1 in WT leaves. The results showed that sites around Agrobacterium infection areas turned red compared with the corresponding controls (Fig. 1B, C). Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the transcript levels of Medtr2g019780, Medtr3g064700, Medtr7g104290, Medtr7g051510, and Medtr6g015830 were significantly higher (P<0.001) in leaves overexpressing LAP1 than those in leaves overexpressing GUS (Fig. 1D), suggesting that these five genes are most likely to participate in anthocyanin accumulation.

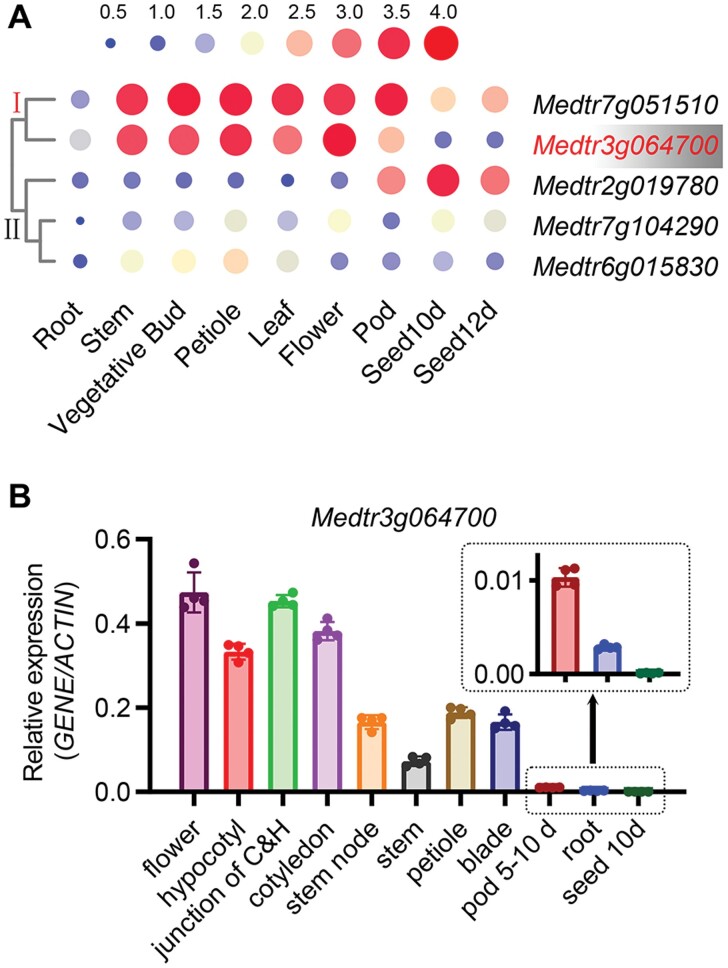

Retrieving the M. truncatula microarray data from the gene expression atlas (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MEXP-1097/ and https://medicago.toulouse.inrae.fr/MtExpress), we found that the expression patterns of the five candidate genes were separated into two obvious clusters (Fig. 2A). Genes in cluster ‘Ⅰ’ showed a high expression in stem, vegetative buds, petiole, leaf, flower and pod, where anthocyanins are usually accumulated (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the Medtr7g051510 in cluster ‘Ⅰ’ also showed a relatively higher expression in seeds where anthocyanins are not accumulated (Fig. 2A). So, we focused on Medtr3g06470 and further verified its tissue expression pattern by qRT–PCR. The result was similar to the microarray data that Medtr3g06470 was expressed at flower, hypocotyl, junction of cotyledon, cotyledon, stem node, stem, petiole blade, and pod where anthocyanins accumulated (Fig. 2B). In root and seeds, the transcript of MtGSTF7 could almost not be detected (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The Medtr3g064700 gene is expressed in anthocyanin accumulating organs. (A) The gene expression atlas of Medtr3g064700, Medtr7g051510, Medtr7g104290, Medtr2g019780, and Medtr6g015830 in different organs of M. truncatula. The normalized expression values were log10 base transformed. The scale is shown at the top. Different sizes and colours in the scale indicate the expression amount. ‘Ⅰ’ and ‘Ⅱ’ show the two different sub-groups clustered by the tissue expression pattern of genes. Genes in cluster ‘Ⅰ’ showed a higher expression in anthocyanin accumulation tissues. (B) The tissue expression pattern of Medtr3g064700 determined by qRT–PCR. Junction of C&H, the junction region of cotyledons and hypocotyl. Two independent biological replicates showed similar results.

MtGSTF7 (Medtr3g064700) is necessary for anthocyanin deposition in M. truncatula

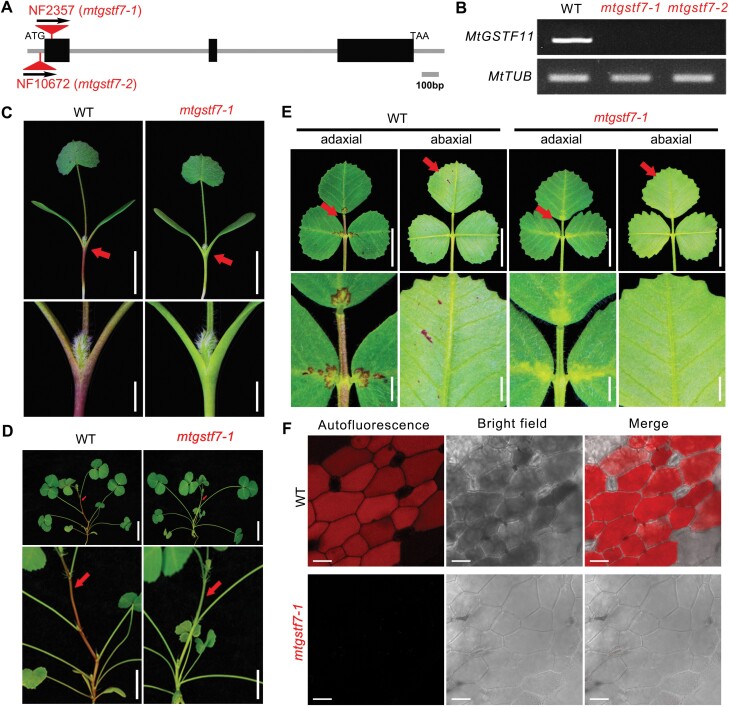

Medtr3g064700 encodes a typical GST protein with a canonical βαβαββα-N-terminal domain and a C-terminal domain composed of an α helix (Supplementary Fig. S3). According to the previously identified GST family members, Medtr3g064700 is named as MtGSTF7 (Hasan et al., 2021). To further functionally characterize MtGSTF7, we used the MtGSTF7 genomic sequence with a partial promoter and with the Tnt1 FSTs (flanking sequence tags) as a query for BLAST analysis in the M. truncatula mutant database (https://medicago-mutant.dasnr.okstate.edu; Tadege et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2019), and successfully isolated two independent Tnt1 insertion lines of MtGSTF7, NF2357 (mtgstf7-1) and NF10672 (mtgstf7-2). According to PCR and Sanger sequencing, we confirmed thatTnt1 retrotransposons were separately inserted in the first exon (45 bp downstream of ATG) and the 5´-UTR (35 bp upstream of ATG) of MtGSTF7 in mtgstf7-1 and mtgstf7-2, respectively (Fig. 3A). Through RT–PCR, we could not detect the full-length transcript of MtGSTF7 in mtgstf7-1 and mtgstf7-2, indicating that mtgstf7-1 and mtgstf7-2 are null mutants (Fig. 3B). Because a similar phenotype was observed between mtgstf7-1 and mtgstf7-2 during the entire developmental period, the mtgstf7-1 mutant allele was used for further analysis in the following studies.

Fig. 3.

Defective anthocyanin accumulation in the mtgstf7-1 mutant. (A) Diagram showing the gene structure of MtGSTF7 and the Tnt1 insertions in mutant alleles. Blank boxes indicate exons and lines between them represent introns. Vertices of red triangles denote Tnt1 insertion sites. Arrows indicate the orientations of Tnt1 insertions. (B) Transcript abundance of MtGSTF7 in WT and two mtgstf7 mutants determined by RT–PCR. The transcript abundance of MtTUB was used as the internal control. (C) Phenotypes of the WT and mtgstf7-1 seedlings. Red arrows indicate the junctions between cotyledon and hypocotyl. Magnified images of junctions are shown in the lower panel. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; lower, 2 mm. (D) Phenotype of 45-day-old plants of WT and mtgstf7-1 mutant. Arrows indicate the red and green stems in WT and mtgstf7-1 mutant, respectively. The magnified images are shown in the lower panel. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; lower, 5 mm. (E) Phenotypes of WT and mtgstf7-1 leaves. Images in the upper panel show the adaxial and the abaxial sides of leaves. Red arrows indicate the spots accumulating anthocyanins in the leaflets, and the magnified images are shown in the lower panel. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; lower, 2 mm. (F) Anthocyanin autofluorescence captured from the adaxial side of WT and mtgstf7-1 mutant leaflets. Scale bars: 25 µm.

In WT seedlings, the junction of cotyledons and hypocotyl, and the bases of cotyledons and petioles are red due to the deposition of anthocyanins (Fig. 3C). However, the anthocyanin depositions were not visible in mtgstf7-1 mutant seedlings (Fig. 3C). The anthocyanin content was decreased sharply so as to be undetectable in extracts from fresh hypocotyls of the mtgstf7-1 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, the disappearance of anthocyanins was also observed in other organs, including leaves, petioles, stems, and even seedpod spines (Fig. 3D, E; Supplementary Fig. S5). Analysis of anthocyanin autofluorescence showed that the deposition of anthocyanins was almost absent in mtgstf7-1 vacuoles (Fig. 3F).

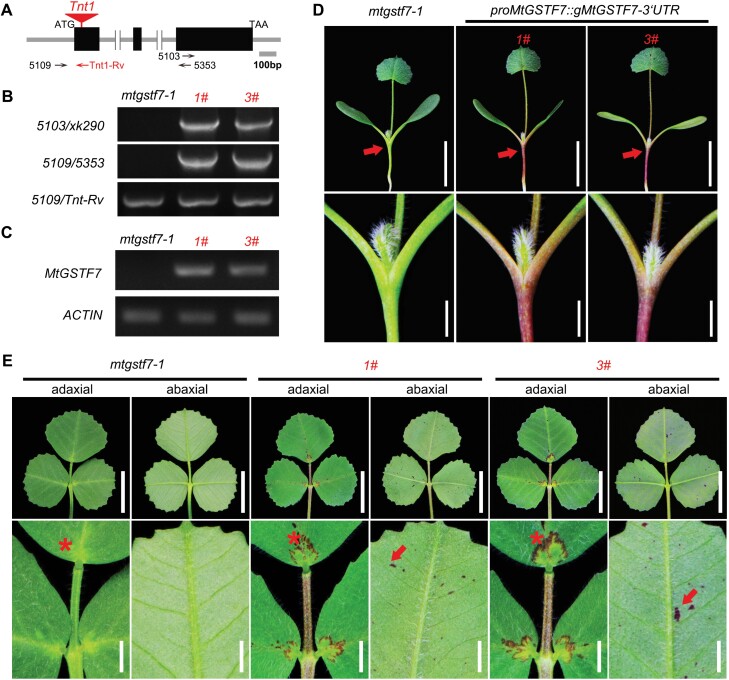

To verify the mtgstf7-1 mutant phenotype, we performed backcrossing and genetic linkage analysis. The segregation ratio of WT: mutants (139:42) in the F2 population was in agreement with Mendel’s law of segregation (Supplementary Table S7). Besides, all 42 isolated mutants showed similar phenotypes with anthocyanin deficiency, and these mutants co-segregated with the homozygous Tnt1 insertion in MtGSTF7 (Supplementary Fig. S6). To test whether MtGSTF7 could complement the mutant phenotype, we performed a genetic complementation experiment by transferring the MtGSTF7 genomic fragment into the mutant background and obtained ten independent transgenic plants. Genotyping and genetic analysis showed that seven of the transgenic lines carried the MtGSTF7 genomic fragment in the mtgstf7-1 genetic background (Fig. 4A, B), and RT–PCR could amplify the entire transcript of MtGSTF7 in these rescued lines (Fig. 4C). The defect of anthocyanin accumulation seen in the mutant was completely recovered in these positive transgenic lines (Fig. 4D, E; Supplementary Fig. S4). On the basis of these results, we conclude that MtGSTF7 is essential for anthocyanin accumulation in M. truncatula.

Fig. 4.

The anthocyanin deficiency of mtgstf7-1 can be completely rescued by MtGSTF7. (A) Diagram showing the MtGSTF7 gene structure and the locations of primers used for genotyping. Arrows indicate the orientations of primers. (B) The genotyping of independent rescued lines. Primer xk290 is a specific reverse primer located in the ProMtGSTF7::gMtGSTF7-3’UTR construct. The locations of other primers are shown in (A). (C) Transcript abundance of MtGSTF7 in mtgstf7-1 and two rescued lines determined by RT–PCR. MtACTIN was used as an internal control. (D) Phenotypes of mtgstf7-1 and two representative independent rescued lines. Red arrows indicate the junctions between cotyledon and hypocotyl, and magnified images are shown in the lower panel. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; lower, 2 mm. (E) Leaf phenotypes of mtgstf7-1 and two independent rescued lines. Images in the upper panel show the adaxial and the abaxial sides of leaves. Images in the lower panel show the magnification of the adaxial side of the leaflet basal region and the abaxial side of the terminal leaflets. Asterisks indicate that the disappearance of anthocyanin deposition on the adaxial side of the leaflets was complemented by introducing the MtGSTF7 genomic sequence into the mtgstf7-1 mutant. Red arrows indicate the scattered spots on the abaxial side of terminal leaflets of rescued lines. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; below, 2 mm.

To test whether mutation of MtGSTF7 affects the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, we checked the expression of anthocyanin-related genes by qRT–PCR. The results showed that the transcript levels of all detected genes in the mtgstf7-1 mutant were not significantly different (P>0.05) from that in WT, except for a slight increase in F3´H transcript (Supplementary Fig. S7), indicating that the anthocyanin biosynthetic process seemed to not be affected by mutation of MtGSTF7.

Ectopic accumulation of anthocyanins is blocked by loss of function of MtGSTF7

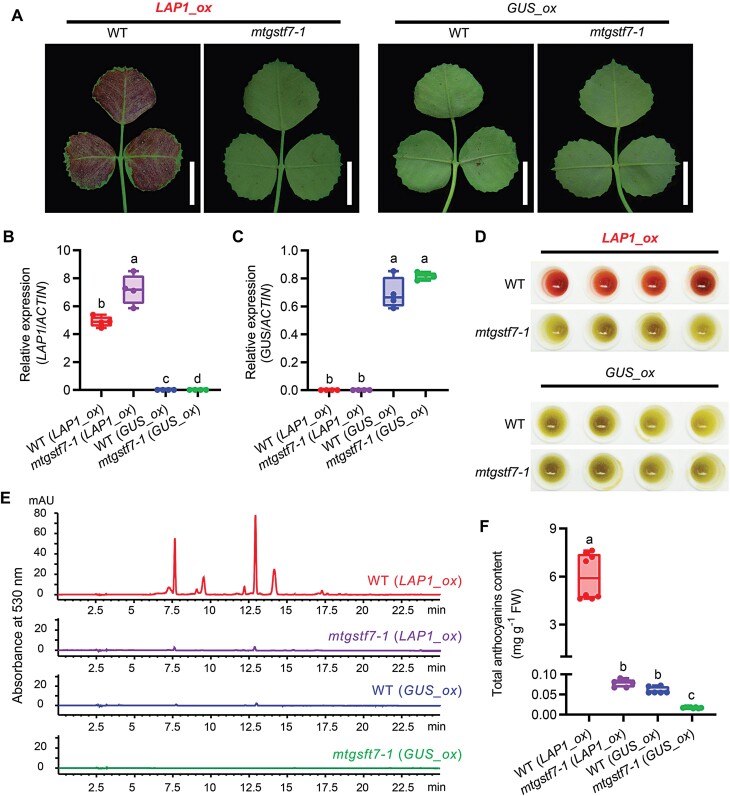

Previous studies demonstrated that transient overexpression of LAP1 in M. truncatula leaves could dramatically induce anthocyanin accumulation (Peel et al., 2009; Picard et al., 2013; Bond et al., 2016). To investigate whether the loss of function of MtGSTF7 affects ectopic accumulation of anthocyanins, we transiently overexpressed LAP1 in WT and mtgstf7-1 leaves. Similar to the previous reports utilizing stable transformation (Pang et al., 2009), the transient overexpression of LAP1 induced a massive accumulation of dark red anthocyanins in the infection areas of WT leaves (Fig. 5A, B; Supplementary Fig. S8A), whereas, in mtgstf7-1 leaves, the infection areas remained green (Fig. 5A-C; Supplementary Fig. S8A). The same conclusion was reached by comparison of the crude extracted leaf pigments (Fig. 5D). Reverse-phase HPLC directly showed that the LAP1-induced anthocyanin content was remarkably reduced in mtgstf7-1 compared with WT (Fig. 5E), by 50–100-fold (Fig. 5F). Quantification of anthocyanin biosynthetic gene transcripts revealed that the transcript abundance of several anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, especially most of the late biosynthesis genes, was higher in mtgstf7-1 mutant overexpressing LAP1 than in WT overexpressing LAP1 (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Taken together, all of these results indicated that loss of function of MtGSTF7 led to the drastic reduction of anthocyanin accumulation.

Fig. 5.

LAP1-induced anthocyanin accumulation depends on MtGSTF7 in M. truncatula. (A) The abaxial sides of WT and mtgstf7-1 leaves that transiently overexpress LAP1 (LAP1_ox). The transient overexpression of GUS (GUS_ox) was used as the negative control. Scale bars: 1 cm. (B) Relative transcript levels of LAP1 in leaves that transiently overexpress LAP1 or GUS. (C) Relative transcript levels of GUS in leaves that transiently overexpress LAP1 or GUS. (D) The pigments extracted from leaves which transiently overexpress LAP1 or GUS. Red colours in the extracts are the results of anthocyanin accumulation and the yellowish-green colours are the chlorophyll. Four independent leaves from different plants were extracted for each experimental group. (E) Reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms of anthocyanins extracted from WT and mtgstf7-1 leaves that transiently overexpress LAP1 and GUS. (F) The total anthocyanin contents of WT and mtgstf7-1 leaves that transiently overexpress LAP1 and GUS. The anthocyanin content was calculated as cyanidin chloride equivalents. FW, fresh weight. The data are mean values ±SD (n=4). Gene transcript levels in (B) and (C) were determined by qRT–PCR. MtACTIN was used as the internal control. The data are mean values ±SD (n=4). Different letters in (B), (C) and (F) donate significant differences (P<0.05; two-way ANOVA tests).

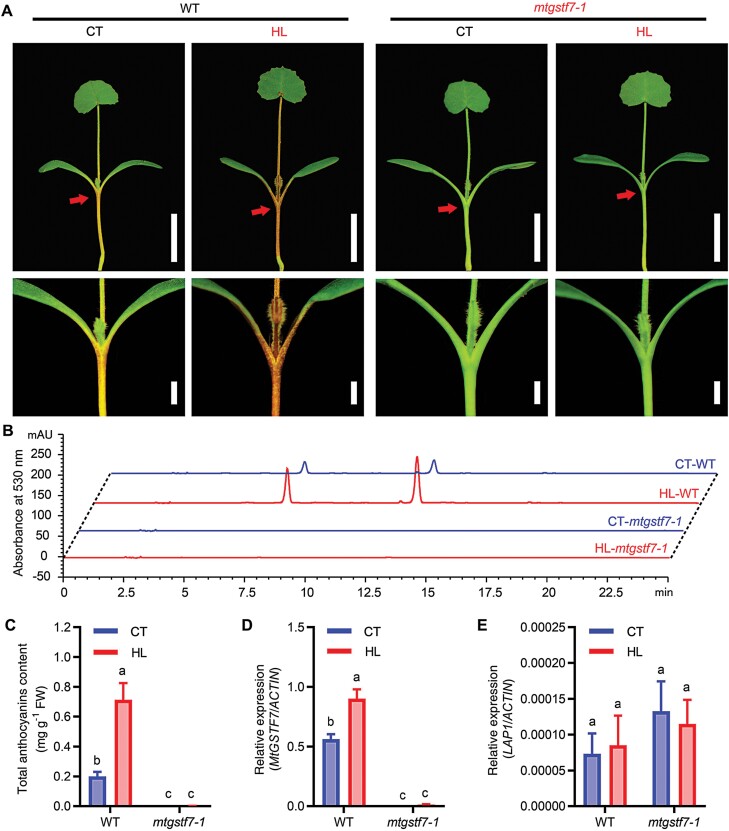

Anthocyanin accumulation can be induced by different abiotic or biotic stresses, such as low temperature, insufficient salt, and high intensity light (Das et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2019). To investigate whether the accumulation of anthocyanins can be induced by stress in the mtgstf7-1 mutant, 3-day-old seedlings of WT and mtgstf7-1 were treated with HL for 4 d. Anthocyanin accumulation was notably increased after treatment by HL stress in WT seedlings (Fig. 6A). The HPLC chromatogram and the quantification of anthocyanin contents revealed that the accumulation of anthocyanins was increased to 3–4 fold in WT under HL stress (Fig. 6B, C). The qRT–PCR results showed that the expression of MtGSTF7 was significantly induced (P<0.01) in WT by HL stress (Fig. 6D). However, in mtgstf7-1, the accumulation of anthocyanins and the expression of MtGSTF7 was barely detected under HL conditions (Fig. 6A-D). The above results demonstrated that MtGSTF7 is activated by HL stress and is essential for anthocyanin accumulation. In comparison with MtGSTF7, the transcript of LAP1 was present at low abundance and was not induced by HL, neither in WT or in mtgstf7-1 (Fig. 6E), indicating that the HL-induced anthocyanin accumulation occurred independent of LAP1.

Fig. 6.

The light-induced accumulation of anthocyanins relies on MtGSTF7. (A) Phenotypes of WT and mtgstf7-1 seedlings in high light conditions. CT, control intensity of lights; HL, high intensity of lights. Red arrows indicate the junctions between cotyledon and hypocotyl (upper panel), and the magnified images are shown in the lower panel. Scale bars: upper, 1 cm; lower, 2 mm. (B) Reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms of anthocyanins extracted from WT and mtgstf7-1 seedlings exposed to different intensity lights. (C) The quantification of anthocyanin contents in WT and mtgstf7-1 seedlings treated under control (CT) and high intensity (HL) light. (D) The relative transcript level of MtGSTF7 in WT and mtgstf7-1 under control (CT) and high intensity (HL) of light. (E) The relative transcript levels of LAP1 in WT and mtgstf7-1 under control (CT) and high intensity (HL) of light. Transcript levels were normalized against MtACTIN. Two independent experiments showed similar results. Different letters denote significant differences between each other (P<0.01, two-way ANOVA tests).

LAP1 can bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter to activate its transcriptional activity

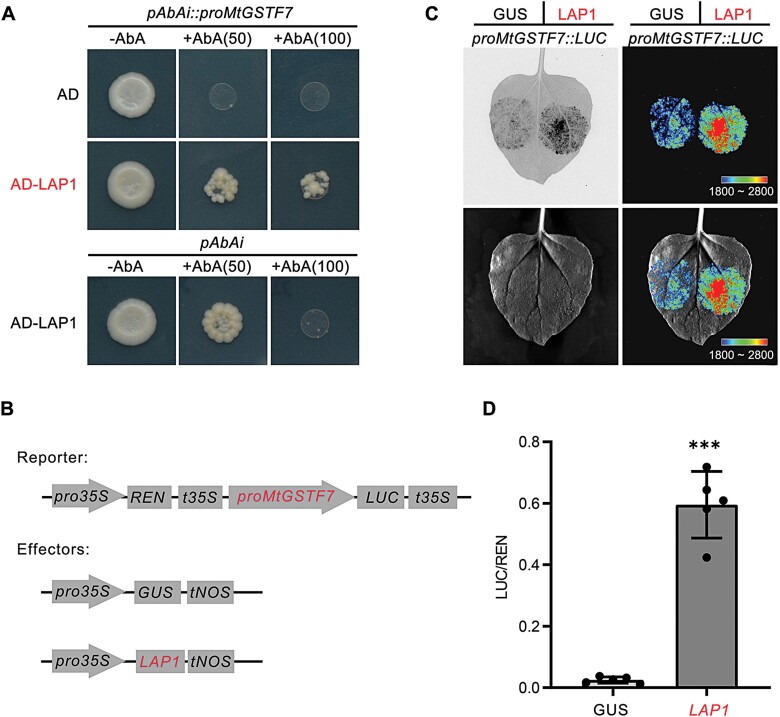

Analysis of the 2.0 kb upstream sequence from the initiation codon of MtGSTF7 in the PlantCARE database (Lescot et al., 2002) showed that six MYB binding sites were present, located at –1902, –1870, –1799, –1220, –334, and –319, respectively. In addition, several phytohormone-responsive elements, light-responsive elements and anaerobic induction elements were also present (Supplementary Table S8). Due to the presence of conserved MYB binding sites, we speculated that the MYB activator LAP1 could bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter. Next, we performed a Y1H assay to detect the interaction of the LAP1 and MtGSTF7 promoter, and the positive Y1H assay supported our speculation that LAP1 can directly bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter in vitro (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

LAP1 can bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter to activate its expression. (A) Yeast-one-hybrid assay showing the interaction of LAP1 and MtGSTF7 promoter. AD represents the empty pGADT7.1 vector. Numbers in brackets indicate the concentration of Aureobasidin A (AbA), ng ml-1. (B) Schematic diagrams showing the reporter and effector constructs used for promoter-luciferase reporter assays. The effector of GUS was used as the negative control. (C) The promoter-luciferase assays showing activation of the MtGSTF7 promoter by LAP1. The upper left image shows the original chemiluminescence picture after 150 s of exposure. The upper right image shows the chemiluminescence image embellished with pseudo-colours. The lower left image shows the monochrome picture of the infiltrated tobacco leaf. The lower right image shows the merged image of the infiltrated tobacco leaf and pseudo-colour picture. Similar results were obtained with five independent biological replicates. (D) The quantitative result of dual-luciferase assays. Ratio of LUC and REN represents the activation efficiency of effectors (GUS and LAP1) when co-transformed with the same reporter. (***P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t-test). The data are mean values ±SD from five independent biological replicates. Four technical replicates were performed for each biological replicate.

To verify whether the binding of LAP1 could induce the transcriptional activity of the MtGSTF7 promoter, a dual-luciferase assay was performed. The results showed that LAP1 could markedly induce the expression of firefly luciferase driven by the MtGSTF7 promoter (Fig. 7B, C), with a LUC/REN (LAP promoter-driven luciferase, compared with Renilla luciferase internal standard) value increased more than 20-fold (Fig. 7D). Taken together, we concluded that LAP1 can bind to the MtGSTF7 promoter to activate its transcriptional activity.

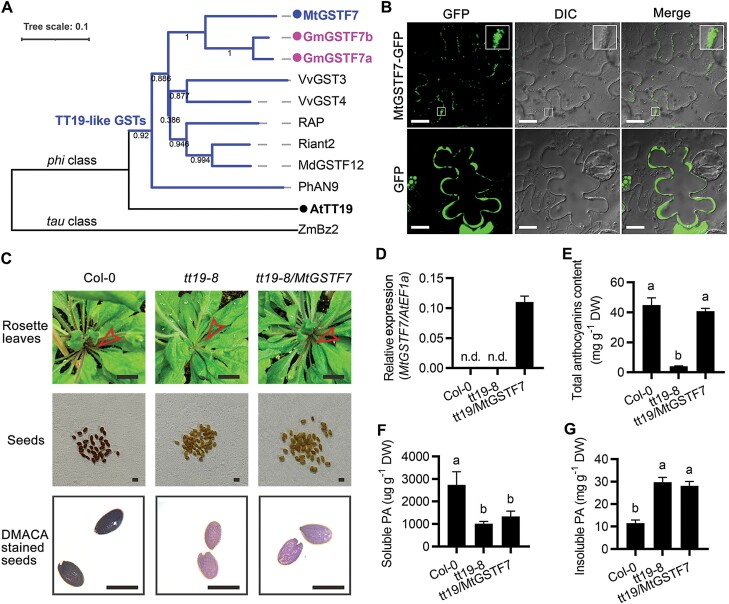

MtGSTF7 can rescue anthocyanin, but not the PA deficiency of Arabidopsis tt19-8 and tt19-7 mutants

In Arabidopsis, AtTT19, a phi GST protein, has been considered as a carrier to transport anthocyanins from the cytosol to the tonoplast (Sun et al., 2012). Due to the fact that MtGSTF7 is a typical GST protein, we hypothesized that MtGSTF7 might be a homolog of AtTT19, functioning in anthocyanin transport. Therefore, we analysed its phylogenetic relationship with AtTT19 and other anthocyanin accumulation related-GSTs, based on the entire protein sequences. The amino acid sequence alignment showed that MtGSTF7 presented a high amino acid similarity to other GSTs related to anthocyanin accumulation (Supplementary Fig. S9). Additionally, MtGSTF7 was clustered into the phi class clade with a group of TT19-like GSTs in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 8A). Subsequent protein sub-localization analysis demonstrated that MtGSTF7 protein localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 8B; Supplementary Fig. S10) similar to other TT19-like GSTs, suggesting that it is a homolog of these proteins that might function in the cytoplasm to facilitate the sequestration of anthocyanins into the vacuole.

Fig. 8.

MtGSTF7 is not involved in PA accumulation in A. thaliana. (A) Phylogenetic tree of MtGSTF7 proteins and other anthocyanin accumulation related-GSTs. MtGSTF7 is the homolog of AtTT19. Neighbor-Joining tree was constructed by the software MEGA 6.06 using the p-distance amino acid substitution model with 1000 bootstrap repetitions, and displayed using the online tool iTOL. The tree scale for branch lengths denotes genetic distance. Bootstrap values are labelled on the middle of the branch. Blue branches indicate TT19-like GSTs clade. (B) The sub-cellular localization of MtGSTF7 in N. bethamiania leaf epidermal cells (upper panels). The sub-cellular location of GFP protein was used as the positive control (lower panels). The MtGSTF7-GFP signal is discontinuous around the cell membrane and the magnified images of the signal in the square areas are presented at the top right corner. Scale bars= 25 µm. (C) Phenotypes of Col-0, tt19-8, and a representative rescued tt19-8/MtGSTF7 transgenic line. Hollow red arrow heads indicate the petiole of rosette leaves. Scale bars: upper=1 cm; central=0.5 mm; lower=0.5 mm. (D) Relative transcript levels of MtGSTF7 in Col-0, tt19-8, and the rescued transgenic line. The gene AtEF1a was used as an internal control. n.d., not detected. (E) The total anthocyanins content of Col-0, tt19-8, and the rescued transgenic line. The anthocyanin content was calculated as C3G (cyanidin-3-O-glucoside) equivalents. DW, dry weight. (F) The soluble PA content of Col-0, tt19-8, and the rescued transgenic line. The soluble PA content was calculated as epicatechin equivalents. (G) The insoluble PA content of Col-0, tt19-8, and the rescued transgenic line. The insoluble PA content was calculated as procyanidin B1 equivalents. Data in (D), (E), (F) and (G) are mean values ±SD (n=3). Different letters in (E), (F) and (G) donate statistically significant differences between each other (P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

In the Arabidopsis tt19-8 (SALK_105779) mutant, both anthocyanin and PA accumulation are defective (Wei et al., 2019). To test whether MtGSTF7 can rescue the phenotypes of tt19-8, we ectopically expressed MtGSTF7 in tt19-8 under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. All independent transgenic lines displayed red rosette leaf petioles similar to those of the WT (Fig. 8C, D), and the anthocyanin accumulation defects were completely rescued in the rosette leaves (Fig. 8E).

In the tt19-8 mutant, the seed coat is pale brown at the ripening stage due to the defect of PA accumulation. After long-term desiccation, the colour turns darker to resemble the WT (Kitamura et al., 2004). In order to harvest the same ripening stage, seeds of Col-0, tt19-8, and rescued lines were germinated at the same time and grown under the same conditions. Unlike complementation by overexpression of AtTT19 (Kitamura et al., 2004), the seed coat colour of all positive transgenic lines was not rescued, with a pale brown coloration at the ripening stage similar to tt19-8 (Fig. 8C). Both DMACA staining assay and PA quantification confirmed that the PA deficiency was not restored by ectopic expression of MtGSTF7 (Fig. 8C, F, G).

To further confirm our results, we also attempted to complement another Arabidopsis tt19 mutant allele, tt19-7, and again, only the anthocyanin defect was restored (Supplementary Fig. S11). Taken together, all the results suggested that, unlike AtTT19, MtGSTF7 assists anthocyanin, but not PA accumulation in A. thaliana.

MtGSTF7 is not recruited to participate in PA accumulation in M. truncatula

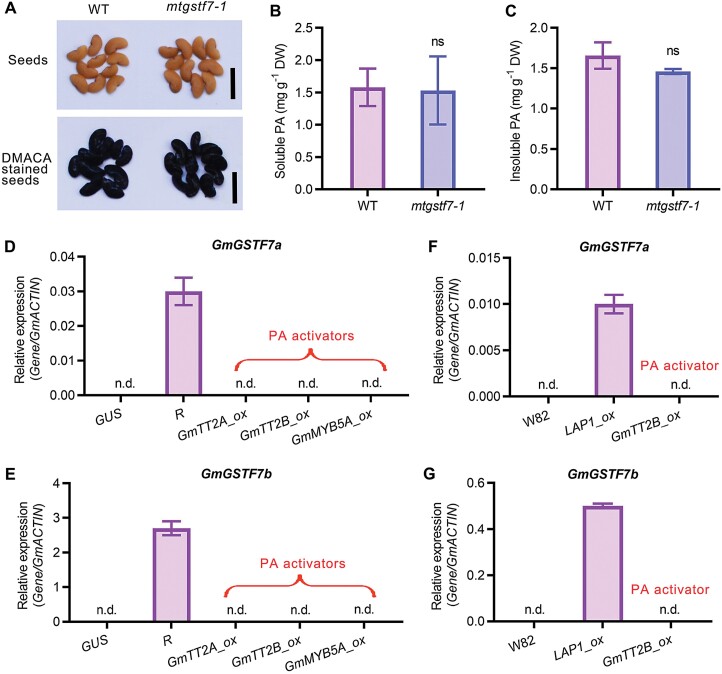

In M. truncatula, PAs in the seed coat reach maximal concentration at around 20 d after pollination (Pang et al., 2007). In contrast to the Arabidopsis tt19 mutants, the seed coat colour of mtgstf7-1 was similar to that of WT (Fig. 9A). To test whether MtGSTF7 participates in PA accumulation, we stained the WT and mtgstf7-1 seeds with DMACA reagent. The stained seeds of mtgstf7-1 showed a similar dark blue colouration to that of WT (Fig. 9A). The quantification results also demonstrated that both soluble and insoluble PA contents were not affected in the mtgstf7-1 mutant (Fig. 9B, C), indicating that MtGSTF7 is not recruited to participate in PA accumulation in M. truncatula.

Fig. 9.

MtGSTF7, and its homologs in soybean, are not responsible for PA accumulation. (A) Phenotype of seeds (upper panel) and DMACA staining of seeds (lower panel) of WT and mtgstf7-1. (B) The soluble PA content of WT and mtgstf7-1 seeds. Scale bars=0.5 cm. (C) The insoluble PA content of WT and mtgstf7-1 seeds. The soluble PA content was calculated as epicatechin equivalents. The insoluble PA content was calculated as procyanidin B1 equivalents. DW, dry weight. Data in (B) and (C) are mean values ±SD (n=4). ‘ns’ above columns denote no statistically significant difference between mtgstf7-1 and WT (P>0.05; unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t-test). (D, E) Relative transcript levels of GmGST7a and GmGSTF7b in G. max hairy roots overexpressing GUS, R, GmTT2A, GmTT2B, and GmMYB5A. Overexpression of GUS was used as the negative control. (F, G) Relative transcript levels of GmGSTF7a and GmGSTF7b in G. max (‘Williams 82’) and transgenic plants overexpressing LAP1 and GmTT2B. Gene transcript levels were determined by qRT–PCR. The GmACTIN gene was used as the internal control. Data are mean values ±SD (n=3). n.d., not detected. GmTT2A, GmTT2B, GmMYB5A are PA activators that induce PA accumulation.

To verify the homologs of MtGSTF7 in soybean, a phylogenetic tree was constructed to analyse the homology of all phi class GSTs in soybean with MtGSTF7 and AtTT19 (Supplementary Fig. S12). The results showed that two homologs of MtGSTF7, namely GmGSTF7a (Glyma.18G043700) and GmGSTF7b (Glyma.11G212900) were present in soybean (Fig. 8A; Supplementary Fig. S12). In our previous study (N. Lu et al., 2021), we observed that GmGSTF7a and GmGSTF7b showed high expression in transgenic hairy roots overexpressing the anthocyanin master regulator R (Supplementary Fig. S13). In contrast, their transcripts were not detected in GmTT2A, GmTT2B and GmMYB5A transgenic lines which accumulated PAs (Supplementary Fig. S13; Supplementary Table S9). A qRT–PCR assay further validated the results (Fig. 9D, E). Besides, the transcript levels of GmGSTF11a and GmGSTF11b were not detectable in W82 (‘Williams 82’) and transgenic soybean overexpressing GmTT2B (Fig. 9F, G), suggesting that these two genes might also play a critical role in anthocyanin accumulation, but are not involved in PA accumulation in soybean.

Discussion

MtGSTF7 plays a critical role in anthocyanin accumulation in M. truncatula

Anthocyanins are synthesized at the surface of the ER, but require to be sequestered into the vacuole to perform their functions (Grotewold and Davies, 2008). In this study, the mutants of a phi class gene, MtGSTF7, exhibited completely green plants with no anthocyanin, similar to that of mtwd40-1 and mttt8 (Pang et al., 2009; Li et al., 2016). However, the transcript levels of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes in mtgstf7 were not significantly different from those in WT (Supplementary Fig. S7), suggesting that the green phenotype is the result of a defect in anthocyanin trafficking, rather than a deficiency in anthocyanin biosynthesis. In addition, the ectopic expression of MtGSTF7 could rescue the anthocyanin deficiency of tt19 mutants (Fig. 8C; Supplementary Fig. S11), demonstrating that MtGSTF7 plays an analogous function with AtTT19 in terms of facilitating anthocyanin transport from ER to the vacuole.

Previous studies have reported that the tonoplast-located transporter MATE2 showed a preferential transport capacity for anthocyanins (Zhao et al., 2011). Anthocyanin content in mate2 seedlings is decreased by 2-3 fold compared with WT (Zhao et al., 2011), whereas the accumulation of anthocyanins in mtgstf7 mutants was almost undetectable. In Arabidopsis, AtTT19 functions prior to the MATE transporter TT12 in PA accumulation (Kitamura et al., 2010). Given that MtGSTF7 is localized in the cytosol (Fig. 8B), it appears that the MATE2-mediated anthocyanin trafficking route might also rely on the function of MtGSTF7. Furthermore, the massive accumulation of anthocyanins induced by overexpressing LAP1 was notably reduced in mtgstf7 (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Fig. S8A), indicating that MtGSTF7 functions in the cytosol to allow the accumulation of anthocyanins in M. truncatula.

Loss of function of MtGSTF7 did not affect the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, even in plants transiently overexpressing LAP1(Supplementary Fig. S8B). However, we could not detect any anthocyanins in mtgstf7 mutants and only detected trace amounts in mtgstf7-1 transiently overexpressing LAP1 (Fig. 5E). A possible explanation is that the synthesized anthocyanins in mtgstf7 mutants might be directly oxidized, degraded or converted to other metabolites in the cytosol. It is reported that the expression of flavanol biosynthetic genes is increased and more flavanols are accumulated in tt19-7 (Sun et al., 2012). In the tt19-8 PAP1-D double mutant line, flavonoids, especially naringenin and quercetin, are significantly increased (Jiang et al., 2020). In the present work, MtFLS is more than 50-fold up-regulated in mtgstf7 compared with WT (Supplementary Fig. S14), indicating the possibility that metabolic flux might be redirected to other flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in mtgstf7 mutants.

Light-induced anthocyanin accumulation mediated by MtGSTF7 is independent of LAP1

Several studies have demonstrated that the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in dicotyledons is conserved, and that the sixth sub-group of MYB TFs plays important roles in anthocyanin accumulation both spatially and temporally (Zhang et al., 2014). In M. truncatula, there are 14 members of the sixth sub-group of MYB TFs (Li et al., 2019), indicating that these paralogs might exhibit functional specialization or redundancy in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Among those paralogs, apart from LAP1 which was identified by reverse genetics, the other three members, WP1, RH1 and RED HEART2 (RH2), have been demonstrated to participate in tissue specific-accumulation of anthocyanins (Peel et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). WP1 is involved in anthocyanin accumulation in petals (Meng et al., 2019), and RH1 and RH2 precisely regulate the red circle anthocyanin leaf marking on the adaxial side (Wang et al., 2021). So, it is very possible that other members of the sixth sub-group of MYB TFs or other TFs might participate in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation, rather than LAP1, which is of low abundance and is not induced by light (Fig. 6F).

Other independent anthocyanin transport mechanisms might be present in M. truncatula flowers

In addition to GST-mediated anthocyanin transport, vesicle trafficking, ER-to-vacuole protein sorting, and microautophagy-mediated anthocyanin transport across the cytosol, have also been proposed (Poustka et al., 2007; Gomez et al., 2011; Chanoca et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been reported that homologs of mammalian membrane protein BTL (bilitranslocase) perform anthocyanin transport in carnation petals and grape berries (Braidot et al., 2008a, b). Although anthocyanins were notably absent in vegetative organs, their deposition in flowers was not affected in mtgstf7-1, suggesting that the anthocyanin transport mechanisms in vegetative organs and flowers are different, and flowers possibly recruit other functionally redundant GST family members, or use other transport mechanisms. It is possible that anthocyanin biosynthesis is spatiotemporally regulated in M. truncatula by different MYB transcription factors, whereby WP1 specifically regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in flowers (Meng et al., 2019). Furthermore, transient overexpression of LAP1 still induced trace amounts of anthocyanin accumulation in mtgstf7. It is therefore reasonable to assume that, although MtGSTF7 facilitates the majority of anthocyanin trafficking across the cytosol, other mechanisms might also function in parallel in M. truncatula.

MtGSTF7 and its homologs in soybean are not recruited to be involved in PA accumulation

In Arabidopsis, AtTT19 is involved in the accumulation of both anthocyanins and PAs (Kitamura et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2012). Mutants of AtTT19, tt19-7, and tt19-8 exhibit anthocyanin and PA-defective phenotypes with green rosette leaves and pale seed coats. In this study, we found that MtGSTF7 could not complement the defective PA phenotypes of tt19-7 and tt19-8. In addition, two null mutants of MtGSTF7 did not affect PA accumulation in M. truncatula. Besides, we did not find MtGSTF7 transcripts in transgenic hairy roots which massively accumulate PAs (Pang et al., 2008; Verdier et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014), suggesting that MtGSTF7 is not recruited for involvement in PA accumulation in M. truncatula. In addition, its homologs in soybean, GmGSTF7a and GmGSTF7b, were also not expressed in PA-enriched transgenic soybean or hairy roots. Taken together, it appears that TT19-like GSTs might not be involved in PA accumulation in legumes.

In a previous report, another mutant, tt19-4, has been characterized, in which a mis-sense mutation in AtTT19 at amino acid 205 (W205L) influenced PA, but not anthocyanin accumulation (Li et al., 2011). According to the protein sequence alignment of all anthocyanin-related GSTs, W205 is conserved in all TT19-like GSTs, including MtGSTF7 (Supplementary Fig. S9). However, MtGSTF7 still could not rescue the PA deficiency of tt19. Therefore, we speculate that, besides W205, other amino acids that are spatially close to W205 might also be required for PA accumulation. Further work is required to address the substrates of TT19-like GSTs, and the functional amino acid residues.

Supplementary data

The following supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. The mapping file for gene IDs of IMGAG V4.0 versus Affymetrix probe sets IDs.

Table S2. The significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in transcriptomic data that was released by Peel et al. (2009).

Table S3. The significant DEGs in transcriptomic data that was released by Peel et al.

Table S4. The details of 35 common DEGs shared between two transcriptomic datasets reported by Peel et al. (2009) and Donna et al. (2016).

Table S5. The details of the expression atlas corresponding to five candidate common genes.

Table S6. List of primer sequences used in this study.

Table S7. The chi-square test of the population from mtgstf7-1 BC1F2 generation.

Table S8. Cis-acting regulatory elements in the MtGSTF7 promoter.

Table S9. FPKM values of Glyma.11G212900 and Glyma.18G043700 in GmMYB5A transgenic hairy roots.

Fig. S1. Standard curves of epicatechin and procyanidin B1 used for analysis of PA content.

Fig. S2. Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from two LAP1 overexpression transcriptomic datasets.

Fig. S3. The analysis of MtGSTF7 protein sequence.

Fig. S4. The anthocyanin content analysis of WT, mtgstf7-1 and the representative rescued lines.

Fig. S5. Phenotype of seed pods in WT and mtgstf7-1 mutant.

Fig. S6. The genetic analysis of the mtgstf7-1 BC1F2 population.

Fig. S7. The transcript levels of anthocyanin regulators and biosynthetic genes in WT and mtgstf7-1 hypocotyls.

Fig. S8. The adaxial side of leaves and the anthocyanin biosynthetic gene transcript levels following transient overexpression of LAP1.

Fig. S9. The amino acid sequence alignment of MtGSTF7 proteins and other anthocyanin accumulation-related GSTs.

Fig. S10. The prediction of transmembrane helices in MtGSTF7 protein.

Fig. S11. MtGSTF7 only complements the anthocyanin defective phenotype of tt19-7.

Fig. S12. Phylogenetic tree of all phi class GST members in G. max and M. truncatula.

Fig. S13. Expression profiles of GmGSTF7s in G. max transgenic hairy roots.

Fig. S14. The relative transcript level of MtFLS in WT and mtgstf7-1.

Fig. S15. Phenotype of flowers in WT and mtgstf7-1 mutant.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Ji-Rong Huang of Shanghai Normal University for kindly providing the mutant seeds of tt19-7. We also thank Hongmei Li of the Service Center for Bioactivity Screening in State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Plant Resources in West China, for patiently adjusting the parameters to capture anthocyanin auto-fluorescence and for kindly providing the Molecular Devices SpectraMax iD3 to analyse the results of dual-luciferase reporter assays. We acknowledge the support of Public Technology Service Center, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We acknowledge the support from GrasslaNZ Technology Limited, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Contributor Information

Ruoruo Wang, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; Yunnan Key Laboratory of Plant Reproductive Adaptation and Evolutionary Ecology and Institute of Biodiversity, School of Ecology and Environmental Science, Yunnan University, Kunming, Yunnan 650500, China.

Nan Lu, BioDiscovery Institute and Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA.

Chenggang Liu, BioDiscovery Institute and Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA.

Richard A Dixon, BioDiscovery Institute and Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA.

Qing Wu, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Yawen Mao, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Yating Yang, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; School of Life Science, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China.

Xiaoling Zheng, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Liangliang He, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Baolin Zhao, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Fan Zhang, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Shengchao Yang, National and Local Joint Engineering Research Center on Germplasm Innovation and Utilization of Chinese Medicinal Materials in Southwest China, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Haitao Chen, Sanjie Institute of Forage, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China.

Ji Hyung Jun, BioDiscovery Institute and Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA.

Ying Li, BioDiscovery Institute and Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA.

Changning Liu, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Yu Liu, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China.

Jianghua Chen, CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, CAS Center for Excellence for Molecular Plant Science, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China; Yunnan Key Laboratory of Plant Reproductive Adaptation and Evolutionary Ecology and Institute of Biodiversity, School of Ecology and Environmental Science, Yunnan University, Kunming, Yunnan 650500, China; School of Life Science, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China.

Elspeth MacRae, New Zealand.

Author contributions

JC, RW, and RAD designed the research; RW and NL accomplished experiments with the help of QW, YY, XZ, LH, BZ, HC, JHJ, YL, YL, and FZ. YM performed the Y1H assay; the HPLC assays were performed with the help of SY; RW analysed the transcriptome data with the help of CL; RW wrote the paper; RAD, CL, and NL edited the paper.

Conflict of interest

All of the authors in this study declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

We acknowledge the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grants of XDA26030301 and XDB27030106), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants of U1702234 and 32070204), the High-end Scientific and Technological Talents in Yunnan Province (Grant 2015HA032), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Grant 202101AW070004), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant 2021395), the National Science Foundation (Grant 703285), the CAS-Western Light ‘Cross-Team Project-Key Laboratory Cooperative Research Project’ (Grant E1XB051) for providing funding support.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and supplementary data published online.

References

- Albert NW, Lewis DH, Zhang H, Schwinn KE, Jameson PE, Davies KM.. 2011. Members of an R2R3-MYB transcription factor family in Petunia are developmentally and environmentally regulated to control complex floral and vegetative pigmentation patterning. The Plant Journal 65, 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedito VA, Torres-Jerez I, Murray JD, Andriankaja A, Allen S, Kakar K, Wandrey M, Verdier J, Zuber H, Ott T, et al. 2008. A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. The Plant Journal 55, 504–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DM, Albert NW, Lee RH, Gillard GB, Brown CM, Hellens RP, Macknight RC.. 2016. Infiltration-RNAseq: transcriptome profiling of Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration of transcription factors to discover gene function and expression networks in plants. Plant Methods 12, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz JO, Xia Y, Blount J, Dixon RA, Lamb C.. 2000. Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. The Plant Cell 12, 2383–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidot E, Petrussa E, Bertolini A, Peresson C, Ermacora P, Loi N, Terdoslavich M, Passamonti S, Macrì F, Vianello A.. 2008a. Evidence for a putative flavonoid translocator similar to mammalian bilitranslocase in grape berries (Vitis vinifera L.) during ripening. Planta 228, 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidot E, Zancani M, Petrussa E, Peresson C, Bertolini A, Patui S, Macrì F, Vianello A.. 2008b. Transport and accumulation of flavonoids in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Plant Signaling & Behavior 3, 626–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelli E, Titta L, Giorgio M, Mock HP, Matros A, Peterek S, Schijlen EG, Hall RD, Bovy AG, Luo J, Martin C.. 2008. Enrichment of tomato fruit with health-promoting anthocyanins by expression of select transcription factors. Nature Biotechnology 26, 1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanoca A, Kovinich N, Burkel B, Stecha S, Bohorquez-Restrepo A, Ueda T, Eliceiri KW, Grotewold E, Otegui MS.. 2015. Anthocyanin vacuolar inclusions form by a microautophagy mechanism. The Plant Cell 27, 2545–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R.. 2020. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Molecular Plant 13, 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn S, Curtin C, Bézier A, Franco C, Zhang W.. 2008. Purification, molecular cloning, and characterization of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) from pigmented Vitis vinifera L. cell suspension cultures as putative anthocyanin transport proteins. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 3621–3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson V, Durand P, d’Erfurth I, Kondorosi A, Ratet P.. 2006. Medicago truncatula transformation using leaf explants. Methods in Molecular Biology 343, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PK, Shin DH, Choi SB, Park YI.. 2012. Sugar-hormone cross-talk in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Molecules and Cells 34, 501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Liu C, Jun JH.. 2013. Metabolic engineering of anthocyanins and condensed tannins in plants. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 24, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Xie D-Y, Sharma SB.. 2005. Proanthocyanidins-a final frontier in flavonoid research? New Phytologist 165, 9–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C, Conejero G, Torregrosa L, Cheynier V, Terrier N, Ageorges A.. 2011. In vivo grapevine anthocyanin transport involves vesicle-mediated trafficking and the contribution of anthoMATE transporters and GST. The Plant Journal 67, 960–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold E, Davies K.. 2008. Trafficking and sequestration of anthocyanins. Natural Product Communications 3, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock KR, Collette V, Fraser K, Greig M, Xue H, Richardson K, Jones C, Rasmussen S.. 2012. Expression of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor TaMYB14 from Trifolium arvense activates proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the legumes Trifolium repens and Medicago sativa. Plant Physiology 159, 1204–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan MS, Singh V, Islam S, Islam MS, Ahsan R, Kaundal A, Islam T, Ghosh A.. 2021. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of glutathione S-transferase family under multiple abiotic and biotic stresses in Medicago truncatula L. PLoS One 16, e0247170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Allan AC, Friel EN, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Templeton MD, Karunairetnam S, Gleave AP, Laing WA.. 2005. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Zhao J, Lai B, Qin Y, Wang H, Hu G.. 2016. LcGST4 is an anthocyanin-related glutathione S-transferase gene in Litchi chinensis Sonn. Plant Cell Reports 35, 831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Chen M, He N, Chen X, Wang N, Sun Q, Zhang T, Xu H, Fang H, Wang Y, et al. 2019. MdGSTF6, activated by MdMYB1, plays an essential role in anthocyanin accumulation in apple. Horticulture Research 6, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Gutierrez-Diaz A, Mukundi E, Lee YS, Meyers BC, Otegui MS, Grotewold E.. 2020. Synergy between the anthocyanin and RDR6/SGS3/DCL4 siRNA pathways expose hidden features of Arabidopsis carbon metabolism. Nature Communications 11, 2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JH, Lu N, Docampo-Palacios M, Wang X, Dixon RA.. 2021. Dual activity of anthocyanidin reductase supports the dominant plant proanthocyanidin extension unit pathway. Science Advances 7, eabg4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Matsuda F, Tohge T, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Yamazaki M, Saito K, Narumi I.. 2010. Metabolic profiling and cytological analysis of proanthocyanidins in immature seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana flavonoid accumulation mutants. The Plant Journal 62, 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Shikazono N, Tanaka A.. 2004. TRANSPARENT TESTA 19 is involved in the accumulation of both anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 37, 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S.. 2002. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 30, 325–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Chen B, Zhang G, Chen L, Dong Q, Wen J, Mysore KS, Zhao J.. 2016. Regulation of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis by Medicago truncatula bHLH transcription factor MtTT8. New Phytologist 210, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu Y, Zhao J, Zhen X, Guo C, Shu Y.. 2019. Genome-wide identification and characterization of R2R3-MYB genes in Medicago truncatula. Genetics and Molecular Biology 42, 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Gao P, Cui D, Wu L, Parkin I, Saberianfar R, Menassa R, Pan H, Westcott N, Gruber MY.. 2011. The Arabidopsis tt19-4 mutant differentially accumulates proanthocyanidin and anthocyanin through a 3’ amino acid substitution in glutathione S-transferase. Plant, Cell & Environment 34, 374–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila MA, Burton-Freeman B, Grace M, Kalt W.. 2016. Unraveling anthocyanin bioavailability for human health. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 7, 375–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Jun JH, Dixon RA.. 2014. MYB5 and MYB14 play pivotal roles in seed coat polymer biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiology 165, 1424–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Wang X, Shulaev V, Dixon RA.. 2016. A role for leucoanthocyanidin reductase in the extension of proanthocyanidins. Nature Plants 2, 16182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Cao H, Pan L, Niu L, Wei B, Cui G, Wang L, Yao JL, Zeng W, Wang Z.. 2021. Two loss-of-function alleles of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene cause anthocyanin deficiency in flower and fruit skin of peach (Prunus persica). The Plant Journal 107, 1320.– . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Rao X, Li Y, Jun JH, Dixon RA.. 2021. Dissecting the transcriptional regulation of proanthocyanidin and anthocyanin biosynthesis in soybean (Glycine max). Plant Biotechnology Journal 19, 1429–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Dai C, Li Y, Feng J, Liu Z, Kang C.. 2018. Reduced anthocyanins in petioles codes for a GST anthocyanin transporter that is essential for the foliage and fruit coloration in strawberry. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 2595–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs KA, Alfenito MR, Lloyd AM, Walbot V.. 1995. A glutathione S-transferase involved in vacuolar transfer encoded by the maize gene Bronze-2. Nature 375, 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Wang Z, Wang YQ, Wang C, Zhu B, Liu H, Ji W, Wen J, Chu C, Tadege M, et al. 2019. The MYB activator WHITE PETAL1 associates with MtTT8 and MtWD40-1 to regulate carotenoid-derived flower pigmentation in Medicago truncatula. The Plant Cell 31, 2751–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Peel GJ, Sharma SB, Tang Y, Dixon RA.. 2008. A transcript profiling approach reveals an epicatechin-specific glucosyltransferase expressed in the seed coat of Medicago truncatula. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105, 14210–14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Peel GJ, Wright E, Wang Z, Dixon RA.. 2007. Early steps in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiology 145, 601–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang YZ, Wenger JP, Saathoff K, Peel GJ, Wen JQ, Huhman D, Allen SN, Tang YH, Cheng XF, Tadege M, et al. 2009. A WD40 repeat protein from Medicago truncatula is necessary for tissue-specific anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis but not for trichome development. Plant Physiology 151, 1114–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel GJ, Pang YZ, Modolo LV, Dixon RA.. 2009. The LAP1 MYB transcription factor orchestrates anthocyanidin biosynthesis and glycosylation in Medicago. The Plant Journal 59, 136–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard K, Lee R, Hellens R, Macknight R.. 2013. Transient gene expression in Medicago truncatula leaves via agroinfiltration. Methods in Molecular Biology 1069, 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poustka F, Irani NG, Feller A, Lu Y, Pourcel L, Frame K, Grotewold E.. 2007. A trafficking pathway for anthocyanins overlaps with the endoplasmic reticulum-to-vacuole protein-sorting route in Arabidopsis and contributes to the formation of vacuolar inclusions. Plant Physiology 145, 1323–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigo T, Wang T, Watanabe M, Tohge T.. 2020. Diversity of anthocyanin and proanthocyanin biosynthesis in land plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 55, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Shahzad B, Rehman A, Bhardwaj R, Landi M, Zheng B.. 2019. Response of phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of polyphenols in plants under abiotic stress. Molecules 24,2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Deng L, Du M, Zhao J, Chen Q, Huang T, Jiang H, Li C-B, Li C.. 2020. A transcriptional network promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato flesh. Molecular Plant 13, 42–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Gill US, Nandety RS, Kwon S, Mehta P, Dickstein R, Udvardi MK, Mysore KS, Wen J.. 2019. Genome-wide analysis of flanking sequences reveals that Tnt1 insertion is positively correlated with gene methylation in Medicago truncatula. The Plant Journal 98, 1106–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li H, Huang JR.. 2012. Arabidopsis TT19 functions as a carrier to transport anthocyanin from the cytosol to tonoplasts. Molecular Plant 5, 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M, Wen J, He J, Tu H, Kwak Y, Eschstruth A, Cayrel A, Endre G, Zhao PX, Chabaud M, et al. 2008. Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. The Plant Journal 54, 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier J, Zhao J, Torres-Jerez I, Ge S, Liu C, He X, Mysore KS, Dixon RA, Udvardi MK.. 2012. MtPAR MYB transcription factor acts as an on switch for proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 1766–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Ji W, Liu Y, Zhou P, Meng Y, Zhang P, Wen J, Mysore KS, Zhai J, Young ND, et al. 2021. The antagonistic MYB paralogs RH1 and RH2 govern anthocyanin leaf markings in Medicago truncatula. New Phytologist 229, 3330–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Wang L, Zhang Y, Ruan L, Li H, Wu L, Xu L, Zhang C, Zhou X, Cheng H, Edwards R.. 2019. A coupled role for CsMYB75 and CsGSTF1 in anthocyanin hyperaccumulation in purple tea. The Plant Journal 97, 825–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel BS. 2004. Metabolic channeling in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 55, 85–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]