Abstract

Achieving optimal health for all requires confronting the complex legacies of colonialism and white supremacy embedded in all institutions, including health care institutions. As a result, health care organizations committed to health equity must build the capacity of their staff to recognize the contemporary manifestations of these legacies within the organization and to act to eliminate them. In a culture of equity, all employees—individually and collectively—identify and reflect on the organizational dynamics that reproduce health inequities and engage in activities to transform them. The authors describe 5 interconnected change strategies that their medical center uses to build a culture of equity. First, the medical center deliberately grounds diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts (DEI) in critical theory, aiming to illuminate social structures through critical analysis of power relations. Second, its training goes beyond cultural competency and humility to include critical consciousness, which includes the ability to critically analyze conditions in the organizational and broader societal contexts that produce health inequities and act to transform them. Third, it works to strengthen relationships so they can be change vehicles. Fourth, it empowers an implementation team that models a culture of equity. Finally, it aligns equity-focused culture transformation with equity-focused operations transformation to support transformative praxis. These 5 strategies are not a panacea. However, emerging processes and outcomes at the medical center indicate that they may reduce the likelihood of ahistorical and power-blind approaches to equity initiatives and provide employees with some of the critical missing knowledge and skills they need to address the root causes of health inequity.

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

—Audre Lorde, 1984 1

Despite more than 30 years of health care system-based efforts to advance equity, 2 health disparities persist and have even worsened in some cases. 3 Racial disparities in health care persist and have been difficult to eradicate because the interventions that health care organizations have devised to address them too often ignore structural dynamics, which are the historical, economic, political, social, and cultural forces that produce inequities. 4 In health care, the legacies of colonialism and white supremacy manifest as reluctance to identify racism as a root cause of racial health inequities, 5 an overreliance on the cultural formulations of health problems at the expense of structural formulations, 6 and overemphasis on individual biology and lifestyle rather than historical, social, and political determinants of health. 7 These legacies are present in patient–provider interactions, health care team dynamics, operational processes, clinical education, and community relations.

The staggering disproportionate burden of COVID-19-related infections and deaths among African Americans, American Indians, and Latinos 8,9 has exposed the consequences of ignoring the structural conditions that shape health. This disproportionate burden provides an ongoing reminder that achieving the “full potential for health and well-being across the life span” 10 for all requires confronting the complex legacies of colonialism and white supremacy embedded in all institutions, including health care institutions. These legacies not only include the state-sponsored exclusion of people of color from opportunities to be safe from violence and to obtain quality education or optimal health 11,12 but also the widespread cultural acceptance of hierarchy and individualism, which influence health care delivery. Workplaces often perpetuate the idea that exercising power and control over others, rather than collaboration and mutually empowering relationships, is the only way to achieve safety and productivity. 13 Moreover, the American discourse of individualism produces a deeply held belief that all peoples are able to act independently and have the same opportunities for success. 11,14 Within this discourse, failing to obtain wealth and health, for example, is implicitly seen as a reflection of an individual’s character and choices unrelated to centuries of policies like slavery and redlining, 15 which have allowed White people to accumulate wealth and health over generations. Consequently, health care organizations committed to health equity must build the capacity of their staff to recognize the contemporary manifestations of these legacies within the organization and to act to eliminate them.

The University of Chicago Medicine’s (UCM’s) Culture of Equity

Health equity refers to “everyone [having] a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. Achieving this requires removing obstacles to health—such as poverty and discrimination and their consequences, which include powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay; quality education, housing, and health care; and safe environments.” 16 At the UCM, we see health care quality as one factor contributing to health inequities that we can modify. 17 We aim to advance health equity by transforming the UCM into a more equitable, diverse, and culturally and linguistically competent organization that eliminates disparities in patient and employee outcomes across populations, as measured by stratified performance metrics. 18 Thus, we focus our efforts on improving the health of marginalized groups. 16

We hypothesize that advancing health equity requires fostering a culture of equity 19 in which all employees—individually and collectively—identify and reflect on the organizational dynamics that reproduce health inequities and engage in activities to transform them. Yet, health care organizations, like the society in which they exist, struggle to tell the truth about societal and organizational histories even as the United States witnesses the devastating effects of the pandemic on communities of color. 5,6,20 Until health care and other institutions do so, building a culture of equity and repairing the harms of colonialism and racism are Sisyphean efforts. Moreover, while evidence suggests that organizational culture is critical for the success of equity interventions, a recent scoping review of 14 inequity reduction frameworks revealed that none of them offer detailed steps for how to build such a culture. 21

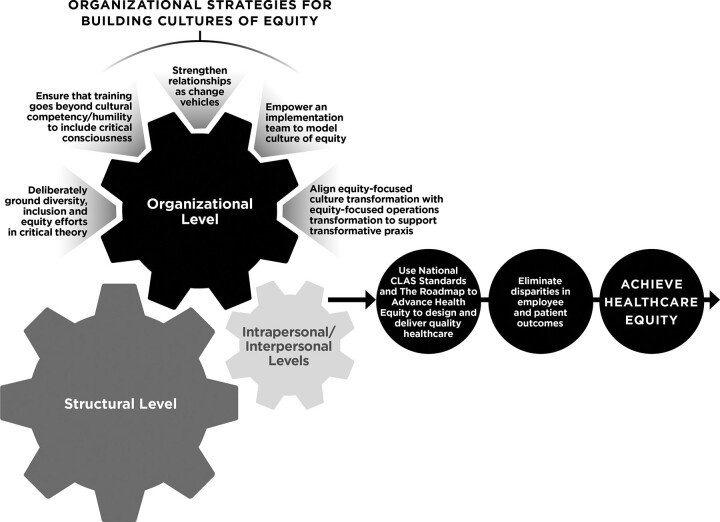

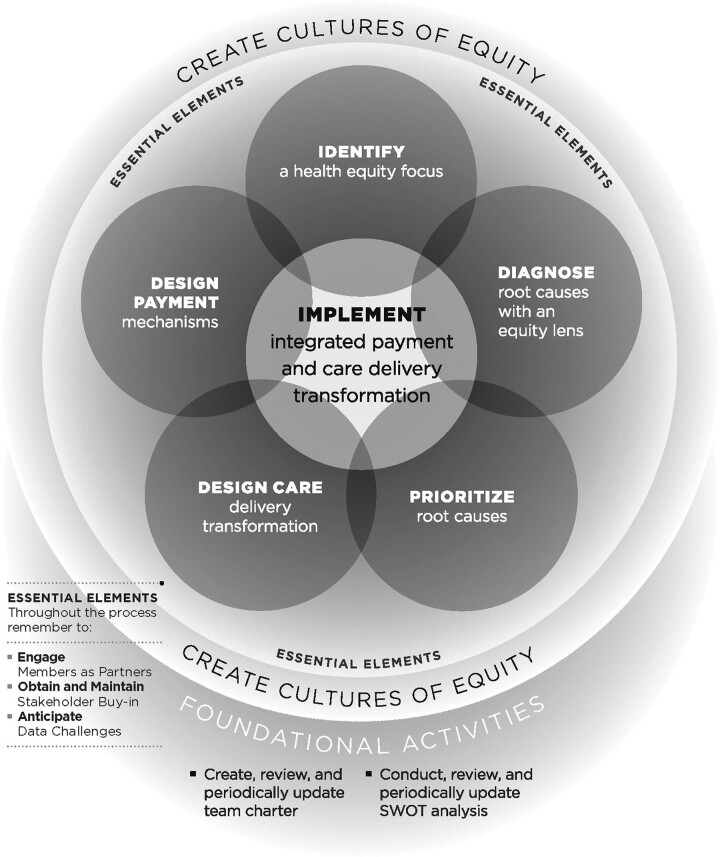

To build a culture of equity at the UCM, we rely on a theory of change, which includes 5 interconnected strategies: (1) deliberately ground diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in critical theory, (2) ensure that training goes beyond cultural competency and humility to include critical consciousness, (3) work to strengthen relationships so they can be change vehicles, (4) empower an implementation team that models a culture of equity, and (5) align equity-focused culture transformation with equity-focused operations transformation to support transformative praxis (Figure 1). These 5 interconnected change strategies are not a panacea. However, they may reduce the likelihood of ahistorical and power-blind approaches to equity initiatives, providing employees with some of the critical missing knowledge and skills they need to address the root causes of health inequity, as demonstrated by some of the UCM’s emerging processes and outcomes (see below and Table 3). Before we describe the 5 strategies, we emphasize that building a culture of equity within an organization is only one component of successful equity initiatives. Figure 2 depicts the Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation’s Roadmap to Advance Health Equity, which also informs the UCM’s approach. The roadmap’s components include, among others, creating a culture of equity, diagnosing root causes with an equity lens, designing care delivery transformations to address those root causes, and supporting them with tailored payment mechanisms. 22–24

Figure 1.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) theory of change. Racism and other forms of oppression operate at the intrapersonal/interpersonal, organizational, and structural (i.e., the historical, economic, political, social, and cultural) levels. Changes at each level are critical to achieving health equity. The figure depicts 5 strategies that can help health care organizations build a culture of equity that can begin to undermine legacies of racism, colonialism, and other intersecting systems of oppression (structural level) embedded in the organization while creating conditions that support change among individual employees (intrapersonal/interpersonal level). In doing so, the organization builds a foundation for effective implementation of tools like the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care 17 and the Roadmap to Advance Health Equity 22–24 that can contribute to the elimination of health care disparities and ultimately to health equity. Simultaneously, historically grounded intersecting systems of oppression hinder organizational and individual transformation, creating inherent tension in the system. Working within this tension can stimulate the innovation necessary for system transformation. Therefore, it is vital to view organizational DEI efforts as complex long-term initiatives requiring careful implementation and evaluation. Copyright © 2021 by the Department of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, University of Chicago Medicine. Reprinted with permission.

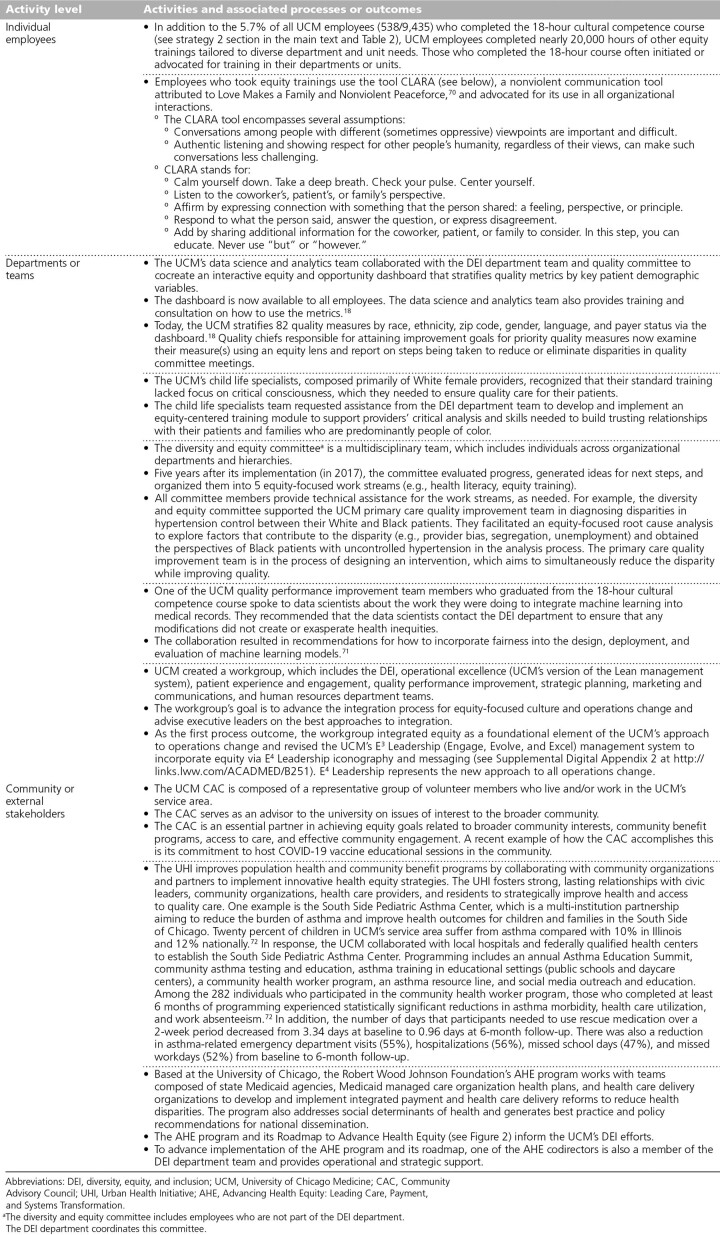

Table 3.

Examples of DEI Change Efforts and Associated Processes or Outcomes at UCM

Figure 2.

The Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation’s Roadmap to Advance Health Equity. 19,22–24 This roadmap informs the University of Chicago Medicine’s approach to creating a culture of equity. The model is composed of multiple components and stipulates that a culture of equity will support, inform, and sustain all equity-focused work of an organization and increase the chances of success. Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation is a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation based at the University of Chicago. Abbreviation: SWOT, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Copyright © 2021 by Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation Program, University of Chicago, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Reprinted with permission.

The UCM Context

The UCM, located on Chicago’s South Side—the population of which is predominantly Black (77%) and experiences poverty (53%) 25—hired its first chief DEI officer in 2012. This action, together with the development of an enterprise-wide, multiprong, multiyear DEI strategic plan and the allocation of resources for its implementation, represented a major turn from numerous fragmented initiatives by individual researchers and departments. The chief DEI officer used the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care, 17 a blueprint with 15 action steps that health care organizations need to take to advance health equity, to integrate a new DEI department into the existing UCM Urban Health Initiative. This step reflected the understanding that advancing health equity requires coordinated actions in the UCM’s internal and external environments. The Urban Health Initiative administers the UCM’s population health and community benefit programs to address complex health needs in South Side communities through community-building initiatives such as Chicago Anchors for a Strong Economy, community health research such as South Side Health & Vitality Studies, and free and low-cost health care services and community-based medical education. Simultaneously, the DEI department focuses on internal organizational change through integrating an equity lens into all aspects of organizational operations. The DEI department team, which initially (i.e., in 2013) included the chief DEI officer, the DEI department director, and 2 consultants, has grown to 21 staff from diverse disciplines (including nursing, education, public administration, psychology, medicine, residency, and chaplaincy) who focus on education, health literacy, quality, and operations as of 2022.

Building the UCM Culture of Equity: 5 Change Strategies

Below we describe the 5 interconnected change strategies (which were also noted above) that undergird the UCM’s efforts to build a culture of equity, highlighting our progress and challenges we have encountered.

Strategy 1: Deliberately ground DEI efforts in critical theory

Efforts to build organizational capacity to address racism and other forms of oppression through changing the organizational culture can easily fail unless they integrate critical theory, an umbrella term for a number of theories including critical race, feminist, and postcolonial theories, 4,26 into change frameworks. 27 Critical theory, which questions the dominant forms of thinking by challenging normative and assumed power relations, 4 has informed our understanding of health inequities as avoidable systematic differences in health and health care caused by unjust structural conditions. 16 Since health disparities are a result of social injustice (e.g., a racialized or gendered phenomenon that emerges in the context of social hierarchies that grant access to economic, political, and social power based on race or gender), they cannot be solved with a power-neutral approach. Critical theory directs us to understand social problems like health inequities by analyzing the systems of power that produce and reproduce them, forcing us to transcend individualist and ahistorical 4 perspectives that hinder accurately diagnosing the root causes of health disparities. In addition to illuminating social problems through analyzing power relations, critical theory seeks to eliminate them through praxis—a process of reflection and action based on critical analysis. 28 Relatedly, it posits that cultural, institutional and organizational, and interpersonal dynamics maintain unjust structures, suggesting that shifting the interactions and processes within an organization can begin to alter the structure. Inherent in this idea is the sense of possibility that employees can become change agents and that their actions can contribute to organizational and social change.

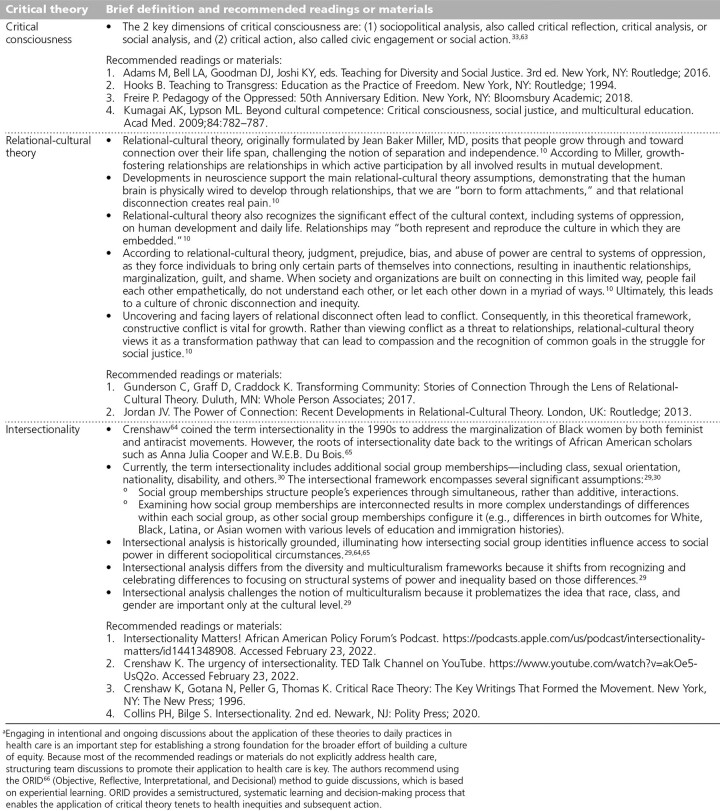

We primarily use 3 critical theories—intersectionality, relational-cultural theory, and critical consciousness (Table 1)—to inform and evaluate our culture and operations change. Intersectionality posits that historically grounded intersecting systems of oppression (e.g., racism, classism) structure people’s experiences and health through simultaneous, rather than additive, interactions (e.g., differences in health care and birth outcomes for White, Black, Latina, or Asian women with different levels of education and immigration histories). 29,30 Relational-cultural theory posits that relationships may “both represent and reproduce the culture in which they are embedded.” 10,13 The current social context normalizes dominant–subordinate relationships and overemphasizes individualism, influencing how health care team members treat each other, conceptualize inequities, and interact with patients and the community. 13 For instance, in health care teams, community health and social workers, who typically have the most connection with patients and use the social determinants of health framework in practice, can significantly improve quality of care and eliminate disparities 31,32; however, they typically have the least amount of power within the health care team. Finally, developing critical consciousness, the ability to analyze social conditions and engage in individual or collective action to reduce inequities, provides a mechanism for change. 33 Together, intersectionality, relational-cultural theory, and critical consciousness inform the remaining 4 change strategies that we use to build a culture of equity.

Table 1.

Definitions of 3 Critical Theories—Critical Consciousness, Relational-Cultural Theory, and Intersectionality—and Recommended Readings or Materials on Eacha

Strategy 2: Ensure that training goes beyond cultural competency and humility to include critical consciousness

Since beginning our DEI efforts in 2012, we have prioritized the development of critical consciousness among all employees, which includes: (1) understanding patients and health care team members in a social and historical context, (2) recognizing societal problems impacting health, and (3) acting to remove barriers to health. 34 We were concerned that traditional approaches to cultural competence and humility often overemphasize implicit bias and exclude information about the nature of the unjust power structures that cause health disparities. 6,34,35 We also wanted our training process to disrupt the often unquestioned power hierarchies embedded in clinical education and practice. 36 Therefore, we used critical pedagogy, 33 which emphasizes education as a practice of freedom 37 and rejects the idea that students learn best by consuming ideas presented by experts. 33 As learning shifts from a lecture-based approach to discussion and analysis, participants transform from objects (adapted to the current unjust hierarchical structures) to self-determining subjects (with the capacity to make choices and change their realities).

Initially, 24 vice presidents, directors, and faculty in formal leadership positions participated in a 3-day residential workshop in 2013 facilitated by the National Conference for Community & Justice of Metropolitan St. Louis. We selected these participants because of the commitment they demonstrated to DEI through their actions and their having a significant sphere of influence due to their position. The aim was to foster their critical consciousness and prepare them for the collective action needed to facilitate broad organizational change. The participants explored how intersecting systems of oppression shaped their experiences using intergroup dialogue. 38 This methodology deepens participants’ relationships through carefully planned, sequentially structured, and facilitated activities that increase in difficulty, intensity, and intimacy. 38 Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 (at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B250) describes the training process used at the workshop. Through this experience, participants became more willing to be accountable for their role in systems that produce health inequities. One immediate action they took was to support the development and implementation of an 18-hour in-person cultural competence course that is open to all UCM employees and is consistent with critical pedagogy principles.

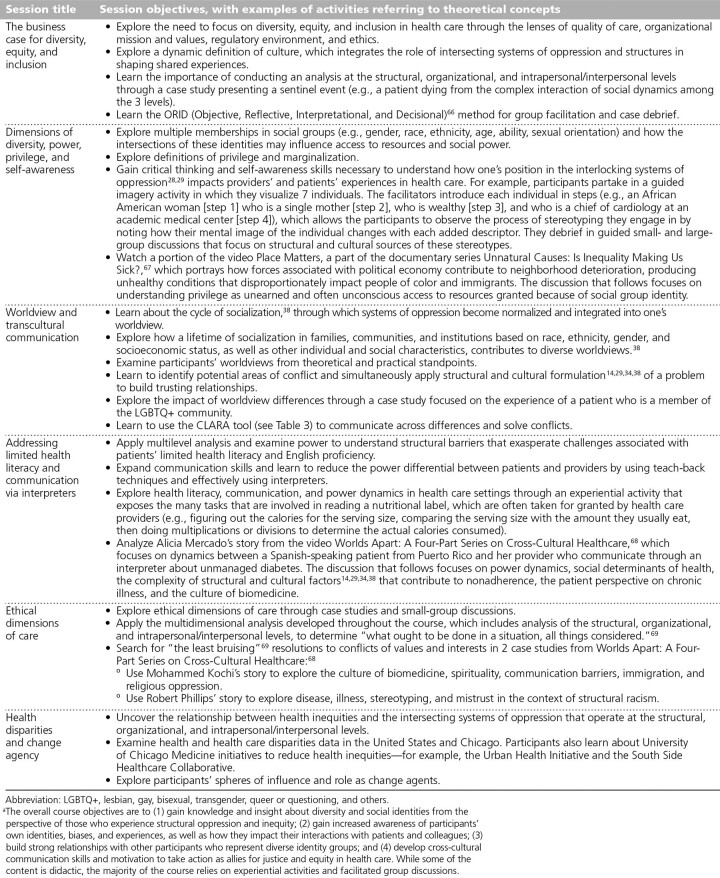

The 18-hour course (Table 2) provides an antioppressive framework and builds skills and knowledge to advance DEI in health care settings. Since the course was implemented in 2014, 538/9,435 (5.7%) employees have completed it. Participants include clinical and nonclinical staff, faculty, and trainees. The 6 sessions of the course build the participants’ capacity to listen deeply, be honest, and disagree, while engaging in critical analysis of oppressive power relations. 38 Because this work is often discomforting, we discuss psychologically brave spaces, which emphasize courage and risk taking in conversations about injustice over the illusion of safety. 39 We use mutually agreed-on process norms and normalize discomfort as necessary for developing critical consciousness. 38 Most importantly, participants begin to experience that a shift in organizational culture from a “power over” to a “power with” model is possible and beneficial for their sense of agency, which motivates them to build that culture with colleagues, patients, and the community.

Table 2.

Voluntary 18-Hour In-Person Cultural Competence Course Open to All University of Chicago Medicine Employeesa

Participation in our trainings, including the 18-hour course, is typically voluntary, which minimizes resistance. In addition to the 18-hour course, we delivered nearly 20,000 hours of equity training tailored to diverse department and unit needs with frontline staff, middle management, and leadership by working with those who were willing. This approach to training, combined with the other 4 change strategies, advances critical consciousness at the organizational level. We have reached thousands of employees who have subsequently led change within their spheres of influence by bringing training to their teams or initiating other projects. For example, supporting critical consciousness among administrative leaders led to the eventual integration of equity in the UCM Vision 2025 strategic plan, board reports, and executive incentives. At different levels of the organization, employee-led resource groups developed a more equitable parental leave policy for all hospital employees and the first sponsor-protégé model to address the underrepresentation of Black women in leadership positions. Table 3 provides other examples of change efforts and associated processes or outcomes, including several that were initiated by employees who completed the 18-hour cultural competence course. When resistance to training arises, we listen to, build relationships with, and engage with the concerned parties to cocreate solutions (see strategy 3 below). For example, we learned from physicians early on that another top-down mandated training would generate resistance and undermine our equity goals. Instead, we engage physicians to cocreate trainings. We are currently codeveloping training on collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data with physicians, and those physicians are leading efforts to ensure that their peers receive this training.

Strategy 3: Work to strengthen relationships so they can be change vehicles

According to relational-cultural theory, healthy development over a person’s life span occurs in the context of quality relationships that support mutual development. Growth-fostering relationships are evidenced by (1) feelings of zest or energy, (2) increased sense of worth, (3) increased awareness of the self and others, (4) the ability to take action both in relationships and outside of them, and (5) the desire for more connection. 9 These types of relationships challenge socially constructed notions of separation and independence, which hinder employees’ agency to confront interpersonal and organizational dynamics that foster inequity. 13 Therefore, one of our main equity strategies is to build and strengthen growth-fostering relationships. For example, our 18-hour cultural competence course intentionally draws participants from all organizational levels, departments, and units, creating cohorts who not only occupy different social identity intersections (e.g., ethnicity, sexual orientation) but also hold different levels of organizational power (e.g., transport workers, nurses, physicians, vice presidents). We introduce nonviolent communication skills, which attend to connection even during conflict by deemphasizing winning (power over) and emphasizing deep understanding (power with; see Table 3). Through dialogue, participants begin to agree on what needs to be done even if they interpret events differently. 40 Still, the mixed cohorts require careful attention to power dynamics to ensure that the learning space is simultaneously radically inclusive and psychologically brave. The facilitators, who have extensive experience with critical pedagogy, use intergroup dialogue methodology (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B250) as an evidence-informed approach 38 to sequence the course content and engage participants in developing shared process norms.

Regular opportunities for others in the organization to cocreate with our DEI department are foundational as we build equity leaders and synergy across the organization. We identify influencers whose jobs do not formally include DEI efforts but who explicitly value DEI. We then provide opportunities for them to develop relationships and a shared understanding of health equity through trainings, retreats, meetings, and initiatives. Our DEI department also engages in strategic initiatives across the organization. All DEI department team members have completed Lean, patient experience, and human resources leadership trainings and take part in other departments’ projects. Through these actions, the DEI department team deliberately brings critical analysis into processes across the organization and amplifies the work of other departments whose efforts contribute to a culture of equity, further disrupting individualism and strict hierarchical dynamics.

Strategy 4: Empower an implementation team that models a culture of equity

One of the most important aspects of our work has been the idea that our DEI department team must embody the culture we want the UCM to develop. To that end, the DEI department team needs to believe that “what we practice at a small scale can reverberate to the large scale.” 41 To ensure this, the chief DEI officer carefully selected DEI department team members who articulated approaches to health equity that were consitent with the critical tradition, but who occupy different social positions based on their intersecting social identities, including professional backgrounds. The DEI department team had protected time during the first 2 years of the initiative (2013–2015) to engage in full-day bimonthly retreats with an external facilitator. During the retreats, the team deepened their critical analysis by discussing readings and materials (see Table 1), engaging each other’s diverse perspectives, learning how to have a productive conflict, and strengthening relationships. The DEI department team members are organizers who seek to “transform the system, transform the consciousness of the people working for the organization, and, in the process, transform their own consciousness.” 42 Listening deeply to peers, marginalized voices, and criticisms and seeing “the beauty of [the] people with whom [they] work, without romanticizing or idealizing them” 42 are key. The DEI department team models how to transform relationships and the hierarchical structure through trainings and meetings facilitation. The team members exemplify a growing capacity to analyze the world using a critical theoretical lens, act, take accountability, and work across and within the groups they occupy. 43 Simply put, the DEI department team embodies the culture the organization is aiming to achieve.

Strategy 5: Align equity-focused culture transformation with equity-focused operations transformation to support transformative praxis

Health care equity efforts require complex fundamental changes in the structure, culture, and operations of an organization. 44,45 Five years after beginning (i.e., in 2017), we evaluated our organization-wide equity initiative to understand the uptake of equity-focused practices, as well as implementation facilitators and barriers. 46,47 Using implementation theory and a convergent mixed methods design, we conducted semistructured key informant interviews (n = 40), surveys of diversity and equity committee members from across the organization (n = 40), and a survey of mid-management (n = 105). We assessed the social network, the organizational culture type, and the extent to which employees felt that they had the support, skills, incentives, commitment, and intention to focus on equity in their everyday practices. The preliminary evaluation (companion paper in preparation) revealed that critical pedagogy raised organizational critical consciousness. Employees recognized inequities and were motivated to create solutions. However, the evaluation also illuminated barriers to advancing health equity: (1) professional silos, (2) leaders who were not involved with the initial efforts struggling to translate equity awareness and desire into actions, and (3) a predominantly top-down hierarchical culture. These findings confirmed that, in complex organizational settings, supporting employees’ praxis to achieve health equity must include a focus on concrete actions to integrate equity into daily work.

As a result of the evaluation, the chief DEI officer and the vice president of operational excellence made integration of equity-focused culture and operations change a shared annual goal. They flattened the organizational hierarchy and began eliminating professional and team silos by tasking a 7-department workgroup with advancing the integration process for equity-focused culture and operations change and advising the executive leaders on the actions they needed to take to advance integration. The workgroup included their teams and the patient experience and engagement, quality performance improvement, strategic planning, marketing and communications, and human resources teams. Principles of relational-cultural theory, such as sharing ownership of the integration goal between 2 executive leaders and a 7-department workgroup, building growth-fostering relationships in meetings, and formally embracing conflict as vital for growth via their operating agreement, allowed these departments to find common ground and begin developing a shared equity-focused culture and operations change framework. Table 3 describes the group’s first shared outcome, which includes iconography and messaging (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B251) for the new leadership management system that includes equity as a foundational element of all operations change.

Evidence of Progress

As of 2022, we have been using the DEI theory of change (Figure 1) for 10 years, have accomplished multiple process outcomes, and are beginning to see outcomes consistent with our DEI strategic goals (see Table 3). Our annual operating plan integrates DEI goals into our people, patients, and quality and safety pillars (e.g., “Build, attract, and retain a diverse and inclusive workforce that is representative of [our] patients and the community”). 48 We also use human resource metrics to gain insight into culture change. For example, we added several subscales from the Diversity Engagement Survey 49 to our annual employee engagement survey, which we collectively use as a diagnostic and benchmarking tool to assess our progress. Our employee engagement and inclusion scores increased from 2013 to 2019. Furthermore, we now stratify 82 quality measures by race, ethnicity, zip code, gender, language, and payer status and make that information available to the entire organization via an interactive equity and opportunity dashboard. 18 In 2018, the UCM also reopened a level 1 adult trauma center, an outcome of a synergy between sustained community activism and new responsive leadership. Chicago’s South Side, previously described as a trauma desert, has a high burden of firearm injury. 50 A recent study demonstrates that the trauma center reopening has been associated with transport time reductions along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines. 50

Measuring the impact of DEI efforts on patient outcomes is critical. However, ameliorating and eliminating root causes of health inequities is a complex endeavor. Organizations should carefully consider the applicability of the measures they choose to evaluate the progress of equity-focused initiatives. Many measures (e.g., return on investment, reduced costs) associated with the contemporary economic zeitgeist and traditional biomedical health perspectives 15,51 ignore the potential impact of culture change and the lengthy timelines needed to align equity-focused initiatives across policy sectors. Such measures may create barriers for the long-term visionary, courageous, and experimental efforts needed to achieve health equity. Health care institutions must commit to building infrastructure and overcoming structural barriers associated with providing quality care to patients experiencing social disadvantage. Thus, it is critical that evaluation criteria do not result in prematurely dismissing initiatives that have the potential for long-term impact.

Concluding Reflections

Colleagues often ask about organizational resistance, especially given the theoretical approach to our work that may appear abstract, impractical, and costly. Persistent health care inequities have been difficult to eradicate because the interventions to address them often use the same cultural and organizational processes that create and sustain them. Health care organizations may begin their equity work with operational changes that the National CLAS Standards 17 or the Roadmap to Advance Health Equity 22–24 recommend (see the right-hand side of Figure 1). For example, ensuring easy access to interpreters; providing plain language materials; or stratifying patient data by race, ethnicity, and other social group identities may be good starting points for many organizations. Yet, they must also realize that even these actions ultimately aim to address problems rooted in unequal power distribution at the intrapersonal/interpersonal, organizational, and structural levels. Organizations must invest in critical pedagogy and growth-fostering relationships based on mutual empathy and accountability. Doing so helps employees dialogue about how unjust structures shape their and their patients’ lives, enabling them to develop a shared understanding of how to reshape these structures. Employees also require implementation training to translate their critical insights into concrete organizational actions. However, processes to change organizational culture and operations must rely on frameworks that place social justice at the center. Otherwise, these processes will uphold the structural dynamics that are at the root of the problem they are seeking to solve.

We expect to meet resistance and work with it when it does emerge as we use the 5 strategies to build a culture of equity, knowing that productive conflict is necessary for growth. Uprooting injustice that is deeply embedded in societal and organizational dynamics is a challenging and long-term process. 52 Thus, assessing readiness for organizational change is essential. Leaders committed to critical theory can ensure that adequate resources and time are allotted for this approach. However, there is an inherent tension in applying critical theory to practice in institutional settings, which can lead to institutions coopting emancipatory ideas in such a way that they end up maintaining the status quo. 53 For instance, while medical education increasingly includes content on the social determinants of health, it often positions the content as something to know about rather than as something to try to change. 54 Similarly, institutions adopting a depoliticized approach to trauma-informed care invest significant efforts to promote employee behaviors that support recovery, which matters, but rarely acknowledge that trauma is racialized and gendered and thus requires structural interventions to eliminate. 55 We encourage DEI department teams to work within this tension and address it directly when it arises. Engaging in reflexivity, making the critical theoretical foundation of the organizational change work explicit, and inviting critique from those working within the critical theoretical tradition outside of the institution, especially community members and activists, can potentially reduce the risk of cooptation. Working within the tension also catalyzes the innovation necessary for developing new tools that can “dismantle the master’s house.” 1,56,57

Comprehensive organizational efforts like ours are costly. At the same time, that cost is necessary to eliminate the overwhelming moral and economic costs associated with structural racism, including preventable medical expenses, illnesses, and premature deaths that disproportionately affect communities of color. 58,59 The 5 change strategies we describe here are an investment in building an inclusive and just academic health system that can attract and retain diverse talent capable of delivering quality health care. 60 In addition to fulfilling our regulatory and legal obligations, evidence suggests that diverse groups with relevant knowledge in an inclusive environment outperform homogeneous groups. 61,62 Compared with homogeneous groups, diverse groups are better at solving complex problems, making predictions, innovating, and succeeding financially. 62 In other words, there are direct benefits to the organization’s operations and overall performance in addition to advancing health equity. The resources required to implement the 5 strategies are a necessary investment to fulfill our mission, which is “to provide superior health care in a compassionate manner, ever mindful of each patient’s dignity and individuality,” 48 and realize our vision to become “an eminent academic health system at the forefront of discovery, advanced education, clinical innovation, and transformative health care” 48 without variation in patients’ experience and outcomes.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank Lisa Sandos, manager, Health Literacy Program, Department of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, University of Chicago Medicine, and Shane Desautels, independent health literacy consultant, for their ongoing contributions to integrating the strategies presented in this article into organizational health literacy efforts. They also thank Grant Schexnider, graphic designer and principal, GSC/Grant Schexnider Creative, Inc., who helped them translate the complex theory of change described in the article into simplified visual representations. They also thank Matthew Bakko and 2 anonymous reviewers whose generous and constructive feedback significantly improved the article.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B250 and http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B251.

Funding/Support: M.H. Chin was supported in part by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation Program (78826), and the Merck Foundation Bridging the Gap: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes Care National Program. S.C. Cook was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation Program (78826). S. Spitzer-Shohat was supported in part by a Rivo-Essrig Fellowship from the Department of Population Health, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Previous presentations: The authors presented a workshop about one of the strategies described in this article at the 11th Annual Association of American Medical Colleges Integrating Quality Conference: Getting on Track to Achieve Health Equity, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 6–7, 2019.

Contributor Information

Scott C. Cook, Email: scook1@bsd.uchicago.edu.

Sivan Spitzer-Shohat, Email: sivan.spitzer-shohat@biu.ac.il.

James S. Williams, Jr, Email: James.Williams@uchospitals.edu.

Brenda A. Battle, Email: Brenda.Battle@uchospitals.edu.

Marshall H. Chin, Email: mchin@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu.

References

- 1.Lorde A. The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In: Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press; 1984;110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke AR, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, et al. Thirty years of disparities intervention research: What are we doing to close racial and ethnic gaps in health care? Med Care. 2013;51:1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2019 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr19/index.html. Published December 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 4.Paradis E, Nimmon L, Wondimagegn D, Whitehead CR. Critical theory: Broadening our thinking to explore the structural factors at play in health professions education. Acad Med. 2020;95:842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb Hooper M, Napoles AM, Perez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323:2466–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saenz R, Garcia MA. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on older Latino mortality: The rapidly diminishing Latino paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76:e81–e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed February 23, 2022. [PubMed]

- 8.Bonilla-Silva E. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 5th ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunbar-Ortiz R. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan JV. Relational–cultural theory: The power of connection to transform our lives. J Hum Counsel. 2017;56:228–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiAngelo RJ. Why can’t we all just be individuals?: Countering the discourse of individualism in anti-racist education. InterActions UCLA J Educ Inform Stud. 2010;6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, Acker J, Plough A. What is health equity? Behav Sci Policy. 2018;4:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdfs/EnhancedNationalCLASStandards.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 18.Connolly M, Selling MK, Cook S, Williams JS, Chin MH, Umscheid CA. Development, implementation, and use of an “equity lens” integrated into an institutional quality scorecard. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:1785–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peek ME, Vela MB, Chin MH. Practical lessons for teaching about race and racism: Successfully leading free, frank, and fearless discussions. Acad Med. 2020;95(12 suppl):S139–S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer-Shohat S, Chin MH. The “waze” of inequity reduction frameworks for organizations: A scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:604–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson AC, O’Rourke E, Chin MH, Ponce NA, Bernheim SM, Burstin H. Promoting health equity and eliminating disparities through performance measurement and payment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook SC, Goddu AP, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, McCullough KW, Chin MH. Lessons for reducing disparities in regional quality improvement efforts. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(suppl 6):s102–s105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chin MH. Advancing health equity in patient safety: A reckoning, challenge and opportunity. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.University of Chicago Medicine. Community health needs assessment: 2018-2019. https://issuu.com/communitybenefit-ucm/docs/ucm-2019-chna. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- 26.Bohman J. Critical theory. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory. Published March 8, 2005. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 27.Kotter JP. Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2. Published May–June 1995. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 28.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen ML, Collins PH. Why race, class, and gender still matter. Andersen ML, Collins PH, eds. In: Race, Class & Gender: An Anthology. 9th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2007;1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Revised, 10th Anniversary. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care Into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/integrating-social-needs-care-into-the-delivery-of-health-care-to-improve-the-nations-health. Accessed February 23, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: An overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 50th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84:782–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dao DK, Goss AL, Hoekzema AS, et al. Integrating theory, content, and method to foster critical consciousness in medical students: A comprehensive model for cultural competence training. Acad Med. 2017;92:335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manca A, Gormley GJ, Johnston JL, Hart ND. Honoring medicine’s social contract: A scoping review of critical consciousness in medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95:958–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams M, Bell LA, Goodman DJ, Joshi KY. eds. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arao B, Clemens K. From safe spaces to brave spaces. In: The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections From Social Justice Educators. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2013;135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wheatley MJ, Kellner-Rogers M. Bringing life to organizational change. J Strategic Performance Meas. 1998;2:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown AM. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mann E. Playbook for Progressives: 16 Qualities of the Successful Organizer. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love BJ. Developing a liberatory consciousness. In: Readings for Diversity and Social Justice. 4th ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2018;610–615. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beer M, Nohria N. Cracking the code of change. Harv Bus Rev. 2000;78:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferlie E, Waldorff SB, Pedersen AR, Fitzgerald L, Lewis PG. Managing Change: From Health Policy to Practice. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.University of Chicago Medicine. University of Chicago Medicine Annual Operating Plan FY 2021. Unpublished.

- 49.Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: The diversity engagement survey. Acad Med. 2015;90:1675–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbasi AB, Dumanian J, Okum S, et al. Association of a new trauma center with racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access to trauma care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:97–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotter JP, Schlesinger LA. Choosing strategies for change. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2008/07/choosing-strategies-for-change. Published July–August 2008. Accessed March 17, 2022. [PubMed]

- 53.Lok J. Why (and how) institutional theory can be critical: Addressing the challenge to institutional theory’s critical turn. J Manag Inquiry. 2019;28:335–349. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: A path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Birnbaum S. Confronting the social determinants of health: Has the language of trauma informed care become a defense mechanism? Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40:476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin MH. New horizons—Addressing healthcare disparities in endocrine disease: Bias, science, and patient care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e4887–e4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chin MH. Uncomfortable truths—What Covid-19 has revealed about chronic-disease care in America. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1633–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ayanian JZ. The costs of racial disparities in health care. Harvard Bus Rev. 2015;93:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 59.LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the economic burden of racial health inequalities in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vela MB, Chin MH, Peek ME. Keeping Our Promise—Supporting trainees from groups that are underrepresented in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:487–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Page SE. The Diversity Bonus: How Great Teams Pay Off in the Knowledge Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dixon-Fyle S, Dolan K, Hunt V, Prince S. Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters. New York, NY: McKinsey & Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

References cited only in tables

- 63.Hooks B. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43:1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murphy Y, Hunt V, Zaijicek AM, Norris AN, Hamilton L. Incorporating Intersectionality in Social Work Practice, Research, Policy, and Education. Washington, DC: NASW Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stanfield RB. The Art of Focused Conversation: 100 Ways to Access Group Wisdom in the Workplace. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fortier JM, Smith LM, Stange E, Strain TH. directors. Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick? [DVD]. San Francisco, CA: California Newsreal; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grainger-Monsen M, Haslett J. Worlds Apart: A Four-Part Series on Cross-Cultural Healthcare [DVD]. Boston, MA: Fanlight Productions; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 69.University of Chicago Medicine, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Department. Cultural Competence Course Curriculum: Session 5, Ethics Module by Dr. Doug Brown. Unpublished.

- 70.Oregon Institute of Peace. OPI de-escalation and bystander intervention training the trainers. https://orpeace.us/?p=272. Published June 7, 2017. Accessed February 23, 2022.

- 71.Rajkomar A, Hardt M, Howell MD, Corrado G, Chin MH. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Urban Health Initiative, University of Chicago Medicine. South Side Pediatric Asthma Center: The Coleman Foundation Grantee Final Report. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Medicine; 2020. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.