Abstract

Blooms of the cyanobacterium Anabaena circinalis are a major worldwide problem due to their production of a range of toxins, in particular the neurotoxins anatoxin-a and paralytic shellfish poisons (PSPs). Although there is a worldwide distribution of A. circinalis, there is a geographical segregation of neurotoxin production. American and European isolates of A. circinalis produce only anatoxin-a, while Australian isolates exclusively produce PSPs. The reason for this geographical segregation of neurotoxin production by A. circinalis is unknown. The phylogenetic structure of A. circinalis was determined by analyzing 16S rRNA gene sequences. A. circinalis was found to form a monophyletic group of international distribution. However, the PSP- and non-PSP-producing A. circinalis formed two distinct 16S rRNA gene clusters. A molecular probe was designed, allowing the identification of A. circinalis from cultured and uncultured environmental samples. In addition, probes targeting the predominantly PSP-producing or non-PSP-producing clusters were designed for the characterization of A. circinalis isolates as potential PSP producers.

Anabaena circinalis is a common planktonic freshwater cyanobacterium, with isolates identified from Europe, North America, Asia, South Africa, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia (2). A. circinalis taxonomy is based on cell shape and size and the location of heterocysts and akinetes along the trichome (2, 5). A. circinalis is often found as mass entangled aggregates or blooms, in the water column or on the water surface. A. circinalis blooms are a major worldwide problem due to their production of a range of toxins, in particular the neurotoxins anatoxin-a and paralytic shellfish poisons (PSPs) (12, 35). In common with other cyanobacteria, A. circinalis blooms can impart tastes and odors to drinking and recreational waters. Cyanobacterial blooms can lead to economic losses through their interference with water treatment processes or closure of waterways to recreational uses (8, 12, 35).

The first neurotoxins to be identified in A. circinalis was anatoxin-a, a tropane-related alkaloid that acts as a powerful depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent (21, 37, 38). More recently, A. circinalis was found to produce members of the PSP family (6, 13). The PSPs are more commonly associated with marine environments, where they are produced by the planktonic dinoflagellates linked with the marine red tides (1). The PSPs can be divided into three groups according to their structure, with each toxin having a differing toxicity. These groups include the highly neurotoxic, nonsulfated saxitoxin (STX) and neosaxitoxin (neoSTX) and their derivatives, the less toxic singly sulfated gonyautoxins (GTXs), and the mildly toxic C toxins (36). STX is the most toxic cyanobacterial toxin, having a 50% lethal dose of 5 μg/kg (6). The PSPs act by blocking neural sodium ion channels, resulting in death through respiratory failure (7). They have been isolated from a wide range of filamentous cyanobacteria species including Aphanizomenon flos-aquae NH-5 (22), Lyngbya wollei (29), and Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (17). PSPs have also been detected in cultures of the bacterium Moraxella sp. (14, 15) and in 40 to 60% of bacteria isolated from dinoflagellate cultures (11).

Although A. circinalis is found worldwide, there is a geographical segregation of neurotoxin production among strains. The reason for the geographical segregation of neurotoxin production by A. circinalis has not been determined. Genetic heterogeneity within A. circinalis, morphological misclassification of isolates, and adaptation of the isolates to specific environmental pressures are possible explanations. Currently, A. circinalis is classified on the basis of morphology. This may not reflect its true population structure, since previous studies have found that the morphological characters used to classify cyanobacteria, including A. circinalis, vary under different culturing conditions (33). In addition, morphological characters do not assist in differentiating potentially toxic and nontoxic A. circinalis isolates.

To determine if the current morphological taxonomy of A. circinalis has molecular support, the 16S rRNA gene was analyzed. Included in the analyses were Anabaena flos-aquae, A. cylindrica, A. solitaria, and A. affinis. From the 16S rRNA gene, the presence of Australian toxic and nontoxic A. circinalis from geographically diverse populations was inferred. In addition, this paper describes the design of specific PCR probes for the identification of A. circinalis in culture and in mixed toxic cyanobacterial blooms. PCR probes were also designed for the identification of A. circinalis isolates as potential PSP producers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and cultivation procedure.

The strains investigated in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains with designations NIES, AWQC or AWT were obtained from the culture collections of the National Institute for Environmental Studies, the Australian Water Quality Centre, and Australian Water Technologies, respectively. Nodularia spumigena NSOR10 was isolated from Orielton Lagoon, Tas, Australia. The cyanobacterial strains were maintained in Jaworsky's medium (13) at 25°C with a light intensity of approximately 1,500 lux (20 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) without aeration or agitation. Cyanobacterial bloom samples were collected from Botany Ponds, Sydney, Australia.

TABLE 1.

Cyanobacterial strains used in this study

| Straina | Country of originb | PSP productionc | Methodsd | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. circinalis AWQC118C | Australia | + | 1, 2 | 4 |

| A. circinalis AWQC131C | Australia | + | 1 | 4 |

| A. circinalis AWQC134C | Australia | + | 1, 2 | 4 |

| A. circinalis AWQC150A | Australia | + | 1, 2 | 4 |

| A. circinalis AWQC173A | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC271C | Australia | − | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC279B | Australia | + | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC306A | Australia | − | 1, 2 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC307C | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC310F | Australia | − | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC323B | Australia | + | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC331C | Australia | − | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC332H | Australia | − | 1 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWQC344B | Australia | + | 2 | P. Baker, personal communication |

| A. flos-aquae AWQC112D | Australia | − | 1 | 4 |

| A. flos-aquae NRC44-1 | Canada | − | 1 | 9 |

| A. flos-aquae NRC525-17 | Canada | − | 1 | 21 |

| A. circinalis AWT001 | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Hawkins, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWT204A | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Hawkins, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWT205B | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Hawkins, personal communication |

| A. circinalis AWT02 | Australia | + | 1, 2 | P. Hawkins, personal communication |

| A. circinalis NIES41 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| A. affinis NIES40 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| A. cylindrica NIES19 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| A. variabilis NIES23 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| A. solitaria NIES80 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| A. circularis NIES21 | Japan | ND | 42 | |

| N. spumigena NSOR10 | Australia | − | 1 | S. I. Blackburn, personal communication |

| C. raciborskii AWT205 | Australia | − | 1 | M. Saker, personal communication |

Species designation as determined by morphology.

Country of original strain isolation.

+, produces PSPs; −, does not produce PSPs; ND, not determined in this study.

Method used to determine toxicity: 1, HPLC; 2, mouse bioassay.

Neurotoxin assays.

PSP toxin assays (Table 1) were performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography and mouse bioassay as described previously (4, 13).

Amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene.

Contaminating heterotrophic bacteria were removed from A. circinalis cultures by filtration through a 3.0-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore, Sydney, Australia). Genomic DNA was extracted from washed cyanobacterial cultures using the XS procedure as described previously (41). Briefly, cell cultures were harvested by centrifugation and the cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of TER (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8], 100 μg of RNase A per ml) and 750 μl of freshly made XS buffer (1% potassium ethyl xanthogenate [Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland], 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 20 mM EDTA [pH 8], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 800 mM ammonium acetate). The tubes were incubated at 70°C for 40 min in a water bath. After incubation, the tubes were vortexed and placed on ice for 30 min. Precipitated cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were carefully transferred to fresh Eppendorf tubes containing 750 μl of isopropanol. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and the precipitated DNA was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g. The DNA pellets were washed once with 70% ethanol, air dried, and finally resuspended in 100 μl of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]).

The 16S rRNA PCR amplification was performed as described previously (28), except that only 2 pmol each of primers 27F1 and 1494Rc (Table 2) was used with 30 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 60 s. The phycocyanin locus was amplified from environmental bloom samples from Botany Ponds using the PCβF and PCαR oligonucleotides (Table 2) as described previously (28).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primera | Sequenceb | Tm(°C)c | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | |||

| 27F1 | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 57 | 27 |

| 530F | GTGCCAGCAGCCGCGG | 69 | 27 |

| 929R | TCC(T/A)CCGCTTGTGCGGGG | 70 | 27 |

| 942F | GGGCCCGCACAAGCGG | 70 | 27 |

| 1494Rc | TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGAC | 56 | 27 |

| A. circinalis specific | |||

| ACB1F | GCTAGTTGGTGGTGTAAGA | 54 | |

| ACB2F | AGGCTTCCTGCCCTGGG | 60 | |

| AC510R | CAATGCCACCTACGGACT | 56 | |

| Phycocyanin PCR | |||

| PCβF | GGCTGCTTGTTTACGCGACA | 50 | 28 |

| PCαR | CCAGTACCACCAGCAACTAA | 50 | 28 |

16S rRNA gene primers are named according to their locus on the E. coli molecule.

5′-to-3′ orientation.

Tm as determined by the nearest-neighbor method.

The 16S rRNA PCR products were precipitated and sequenced as described previously (41). Briefly, Automated BigDye terminator sequencing (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) reactions were performed using 2 μl (∼100 ng) of each PCR product and 10 pmol of each appropriate primer in a half-scale reaction as specified by the manufacturer. Five sequencing reactions were performed for each 16S rDNA product, using the primers 27F1, 530F, 929R, 942F, and 1494Rc (Table 2). Sequencing-reaction products were purified and analyzed as described previously (40).

Phylogenetic analysis.

DNA sequences corresponding to Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene positions 27 to 1494 were aligned using the programs PILEUP (10) and CLUSTAL W (39). The nucleotide alignments were edited by hand to resolve ambiguous alignments and to remove positions with gaps. The 16S rDNA distance tree was reconstructed using the neighbor-joining method with Jukes-Cantor corrections (34) as implemented by CLUSTAL W. The bootstrap confidence levels for the interior branches of the trees were estimated from 1,000 resamplings of the data (10).

A. circinalis-specific PCRs.

PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene sequence corresponding to the E. coli 16S rRNA gene positions bp 27 to 594 (A. circinalis specific), bp 247 to 594 (branch I specific), and bp 202 to 594 (branch II specific) were amplified using the oligonucleotide pairs 27F1 plus AC510R, ACB1F plus AC510R, and ACB2F plus AC510R, respectively (Table 2). The PCR mixture contained 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Biotech International, Perth, Australia), 2.5 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of 10 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 10 pmol of each of the specific primers (Table 2), 10 ng of genomic DNA, and water to a final volume of 20 μl. The reactions were hot started by the addition of 5 μl of water containing 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Biotech International) at the initial 80°C step. Conditions for the A. circinalis-specific (27F1 plus AC510R) PCR were 1 cycle of 80°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 68°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 40 s. Conditions for the branch I-specific (ACB1F plus AC510R) and branch II-specific (ACB2F plus AC510R) PCR were as above except that the annealing temperatures were 64 and 58°C, respectively (Table 2).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences described in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AF247571 to AF247595; C. raciborskii AWT205 has been given accession number AF092504, and N. spumigena NSOR10 has been given accession number AF268014.

RESULTS

The 16S rDNA phylogeny of A. circinalis.

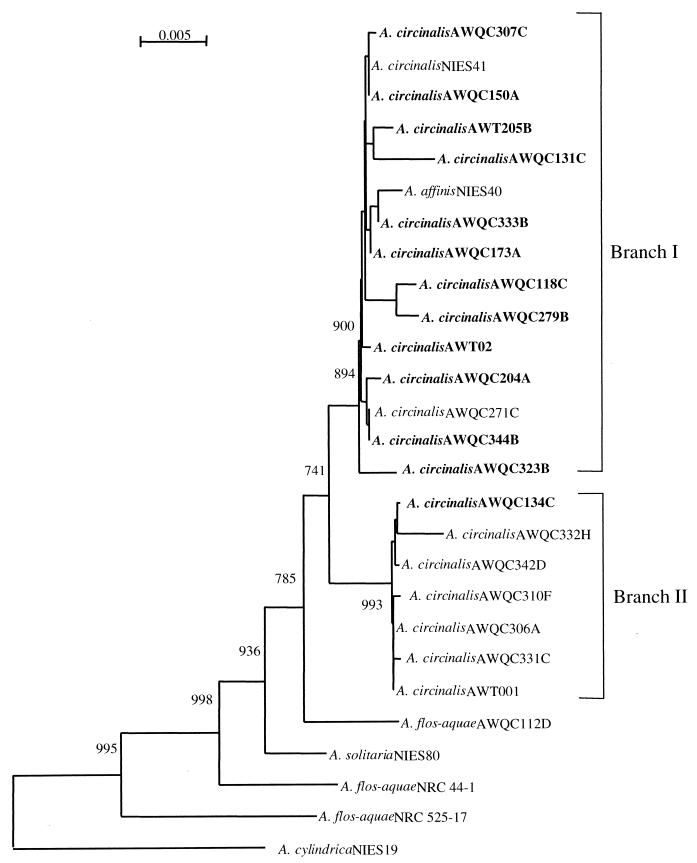

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of 19 toxic and nontoxic A. circinalis strains from geographically diverse locations, 3 A. flos-aquae strains, and single strains of A. affinis, A. solitaria, A. variabilis, Anabaenopsis circularis, and A. cylindrica (Table 1) were determined by PCR amplification and direct sequencing of the region corresponding to the E. coli 16S rRNA gene positions 27 to 1494 (Table 2). The inferred phylogeny was determined (Fig. 1) with A. cylindrica forming the outgroup. In a tree of the Nostocales, A. cylindrica is ancestral to the other lineages within this genus (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

A. circinalis 16S rDNA distance tree. DNA sequences corresponding to the E. coli 16S rRNA gene positions 27 to 1494 were aligned using the programs PILEUP (10) and CLUSTAL W (39). A. circinalis strains in bold were found to produce PSPs as determined by HPLC and mouse bioassay (4; P. Baker, personal communication). Also included were an additional five Anabaena 16S rDNA sequences including A. affinis NIES40, A. solitaria NIES80, and A. flos-aquae AWQC112D, NRC44-1, and NRC525-17. Genetic distances were calculated using the method of Jukes and Cantor, and the phylogenetic was tree reconstructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm of Saitou and Nei (34) as implemented within CLUSTAL W. The root of the tree was determined by using the 16S rRNA gene of A. cylindrica NIES19 as an outgroup. Local bootstrap support for branches present in more than 50% of 1,000 resampling events is indicated at the respective nodes (10).

The alignment of the 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed greater than 98% sequence similarity between all A. circinalis strains. Phylogenetic analysis identified a reliable topology for A. circinalis isolates, with A. circinalis forming a monophyletic cluster within the genus Anabaena with two distinct branches supported by significant bootstrap values. Branch I was found to consist predominantly of PSP-producing A. circinalis, with 12 of the 14 isolates in this branch being PSP producers. The remaining two strains consisted of a nontoxic isolate from Australia and an overseas isolate from Japan, NIES41, whose PSP toxicity status has not been determined. Six of the seven isolates in branch II were found to be nontoxic. The toxic isolate in branch II from Australia, AWQC134C, was found to be highly toxic by high-pressure liquid chromatography and mouse bioassay. There was no correlation between the geographical region of isolation and branching, with northern hemisphere A. circinalis isolates grouping with Australian isolates (Fig. 1). The apparent monophyletic nature of A. circinalis isolates is consistent with the morphological taxonomy of A. circinalis (16); however, the bifurcation of strains within the A. circinalis cluster has not been demonstrated previously. The A. circinalis strains were found to be most closely related to a group of A. flos-aquae isolates from geographically diverse locations, namely, A. flos-aquae 112D from Australia and A. flos-aquae NRC 44-1 and A. flos-aquae NRC 525-17 from Canada (Fig. 1). Interestingly, A. flos-aquae NRC 44-1 and A. flos-aquae NRC 525-17 are also neurotoxic, producing anatoxin-a and anatoxin-a(s), respectively (9, 21). Finally, A. affinis NIES40 clustered with A. circinalis, indicating its possible taxonomic misplacement.

A. circinalis-specific PCR.

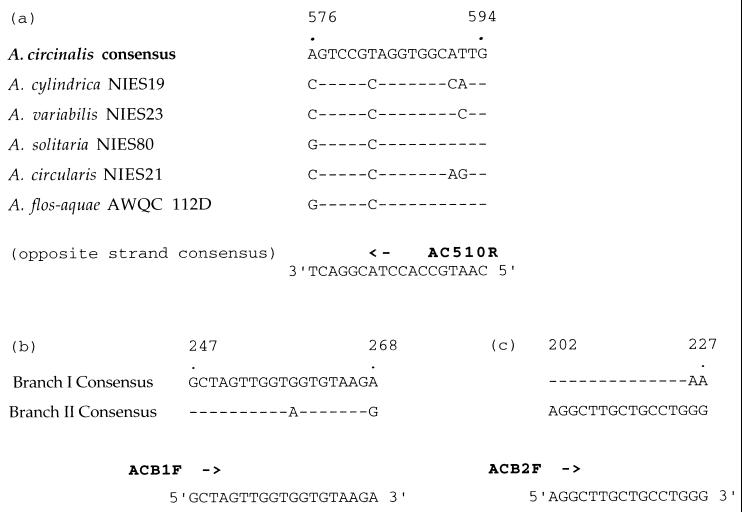

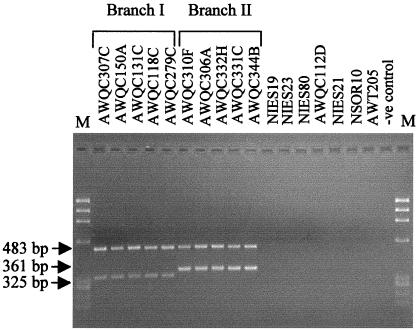

Alignment of the 16S rDNA gene sequences from A. circinalis with A. cylindrica NIES19, A. variabilis NIES23, A. solitaria NIES80, and A. flos-aquae AWQC112D revealed a conserved region unique to A. circinalis (Fig. 2). This conserved region (corresponding to E. coli 16S rRNA gene nucleotide positions 576 to 594) was selected for the design of the A. circinalis-specific oligonucleotide, AC510R. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from A. circinalis isolates using primers 27Fl and AC510R yielded an amplification product of 483 bp. To test the specificity of this primer set, PCR assays were performed using template DNAs isolated from a series of reference strains from three different cyanobacterial genera including Nodularia, Cylindrospermopsis, and Anabaena (Table 1). The A. circinalis-specific amplification product of 483 bp was obtained from all A. circinalis strains, while no amplification product was obtained from A. cylindrica NIES19, A. variabilis NIES23, A. solitaria NIES80, A. flos-aquae AWQC112D, A. circularis NIES21, N. spumigena NSOR10, or C. raciborskii AWT205 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the 16S rRNA-DNA sequences of the bp 576 to 594 region from representatives of different species of cyanobacteria and the consensus sequence of A. circinalis strains (a), the bp 247 to 268 region from the consensus sequence from branch I and branch II A. circinalis strains (b), and the bp 202 to 227 region from the consensus sequence from branch I and branch II A. circinalis strains (c). Oligonucleotides AC510R, ACB1F, and ACB2F were designed on the basis of these sequences. Nucleotide positions correspond to the numbering of the E. coli sequence.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene region using A. circinalis branch I- and branch II-specific oligonucleotide primers. Lanes labeled Branch I and Branch II correspond to the PCR products from the A. circinalis strains; other lanes correspond to the PCR products obtained from the reference strains and to the negative control (-ve control). Amplification with the A. circinalis-specific primer AC510R plus the eubacterial universal primer 27F1 yields a 483-bp product. Amplification with the branch I or branch II primer pairs ACB1F plus AC510R and ACB2F plus AC510R yields 325- and 361-bp PCR products, respectively. The two PCR products from each sample were pooled, and a total of 6 μl was run on a 3% agarose gel in 1× TAE with 100 ng of φX174 HaeIII as DNA marker (lanes M).

Branch I and branch II A. circinalis-specific PCR.

The A. circinalis strains were found to bifurcate into a predominantly toxic cluster and a predominantly nontoxic cluster (Fig. 1). Alignment of the consensus 16S rRNA gene sequence from branch I with that from branch II revealed conserved sequences corresponding to the E. coli 16S rRNA gene at nucleotides 247 to 268 for branch I and nucleotides 202 to 227 for branch II (Fig. 2). These regions were used to design branch-specific A. circinalis probes. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene with ACB1F and AC510R yielded a PCR product of 325 bp for branch I A. circinalis exclusively and no product for branch II A. circinalis (Fig. 3). Similarly, the branch II-specific primer ACB2F with AC510R amplified a product of 361 bp only from branch II isolates and no product from branch I A. circinalis (Fig. 3). Again, no amplification products were detected when template DNAs from A. cylindrica, A. variabilis, A. solitaria, A. flos-aquae, A. circularis, N. spumigena, and C. raciborskii were tested (Fig. 3).

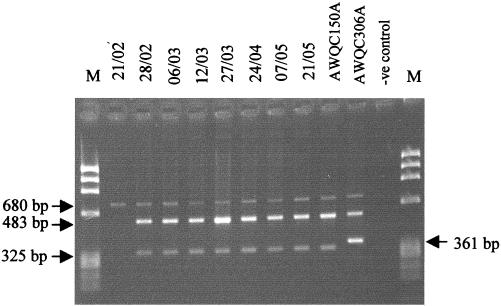

Identification of A. circinalis from bloom samples.

A large neurotoxic and hepatotoxic cyanobacterial bloom event occurred in the Botany Ponds, Sydney, Australia, over the late summer and autumn of 1994. This mixed bloom, dominated by Microcystis and Anabaena species, underwent a number of complex population successions as assessed by microscopy and cyanobacterial toxin data (J. Baker, D. McKay, M. Choice, N. Chandrasena, and P. R. Hawkins, Proc. 4th Int. Conf. Toxic Cyanobacteria, p. 17, 1998). Bloom samples were collected on a weekly to monthly basis, and frozen stocks were stored. Template DNAs, from eight different periods of the bloom, were used to test the A. circinalis-specific PCR as a diagnostic tool. Samples identified as A. circinalis were further characterized using the branch I and branch II probes to determine if periods of high neurotoxicity correlated with periods dominated by branch I A. circinalis strains. The phycocyanin intergenic spacer region was amplified from the template DNAs to test for cyanobacterial DNA and for the presence of possible PCR inhibitors (28). Phycocyanin PCR products of 680 bp were obtained, as expected, from all eight samples (Fig. 4). The A. circinalis-specific PCR produced fragments of 483 bp from seven of the eight samples tested (Fig. 4). This supports microscopic cell counts which found Anabaena dominance over the bloom population during these periods. During these periods, Anabena and Microcystis cell counts ranged from 1.0 × 106 to 0.2 × 106 cells ml−1 and 0.5 × 106 to 0.1 × 106 cells ml−1, respectively. The first sample from which no A. circinalis-specific product was amplified was dominated by Microcystis. In this sample, Microcystis and Anabaena cell counts were 0.1 × 106 and less than 105 cells ml−1, respectively. Further characterization identified the seven A. circinalis samples as branch I members. No amplification products were obtained for any of the eight isolates after amplification with the branch II-specific oligonucleotides ACB2F and AC510R (Fig. 4). Sample collection dates for isolates identified as branch I A. circinalis corresponded to periods of high neurotoxin concentration in the bloom as determined by the mouse bioassay (P. Hawkins, unpublished data).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of 16S rRNA gene using the A. circinalis branch I- and branch II-specific oligonucleotides. Lanes 21/02 to 21/05 correspond to PCR fragments from the environmental bloom samples collected on the dates indicated (day/month). Lanes AWQC105A and AWQC306A correspond to positive controls belonging to branch I and branch II, respectively. Lane -ve control, the negative control. Amplification with the phycocyanin primer pair PCαF plus PCβF yields a 680-bp product. Amplification with the A. circinalis-specific primer AC510R plus the cyanobacterial universal primer 27F1 yields a 483-bp product. Amplification with the branch I or branch II primer pairs ACB1F plus AC510R and ACB2F plus AC510R yields a 325- or 361-bp PCR product, respectively. The three PCR products from each sample were pooled, and a total of 6 μl was run on a 3% agarose gel in 1× TAE with 100 ng of φX174 HaeIII as DNA marker (lanes M).

DISCUSSION

A. circinalis blooms have become a major worldwide problem in aquatic habitats due to their production of toxic secondary metabolites (2, 3, 13, 25, 37, 38). To determine if the geographical segregation of neurotoxin production by A. circinalis was due to genetic heterogeneity of the A. circinalis or to morphological misclassification, the 16S rRNA gene sequences was analyzed. The currently used morphology-based classification is prone to subjective interpretation and cannot differentiate between toxic and nontoxic A. circinalis strains. Consequently, molecular probes able to identify toxic isolates of A. circinalis would be highly valuable.

In this study the 16S rRNA phylogeny of 19 A. circinalis strains, 3 A. flos-aquae strains, and 1 strain each of A. affinis, A. solitaria, and A. cylindrica from geographically diverse populations was examined. The strains included PSP- and non-PSP-producing A. circinalis and nontoxic A. flos-aquae strains from Australia, as well as nontoxic A. solitaria and A. cylindrica from Japan, and toxic A. flos-aquae from Canada. Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rDNA revealed that Australian and non-Australian A. circinalis strains formed a phylogenetically coherent group. Although there was a segregation of toxin production among strains, A. circinalis from Australia did not form a separate genetic population distinct from northern-hemisphere isolates. The localization of PSP production to Australia by A. circinalis may be the result of horizontal acquisition of the phylogenetically widespread PSP biosynthetic pathway by Australian A. circinalis. PSP production may give a selective advantage to Australian strains in some, but obviously not all, ecological niches.

The A. circinalis strains were found to be most closely related to A. flos-aquae isolates from geographically diverse locations, namely, A. flos-aquae 112D from Australia and A. flos-aquae NRC 44-1 and A. flos-aquae NRC 525-17 from Canada. Interestingly, A. flos-aquae NRC 44-1 produces anatoxin-a and A. flos-aquae NRC 525-17 produces anatoxin-a(s), the only other neurotoxin producers analyzed in this study (9, 21). This suggests the existence of a common ancestor of the neurotoxic Anabaena species, with the current A. circinalis PSP producers being a relatively recent divergent population. This finding is consistent with the possible horizontal acquisition of the PSP biosynthetic pathway by Australian A. circinalis. A. circinalis formed a separate cluster from A. flos-aquae based on 16S rDNA sequence analyses, which is in agreement with the morphology-based taxonomy (2). This is interesting considering that in the absence of akinetes, the morphological characteristic used to differentiate A. circinalis from A. flos-aquae is trichome spiral breadth, a character which appears to be phenotypically plastic (4). Isolates with spiral breadth greater than 50 μm are classified as A. circinalis, while isolates with spiral breadth less than 50 μm are described as A. flos-aquae (2).

The A. circinalis cluster formed two distinct clades supported by significant bootstrap values (Fig. 1). Branch I was found to consist predominantly of PSP-producing A. circinalis strains except for one isolate from Australia (AWQC271C) and A. affinis from Japan (NIES40). Branch II was composed of non-PSP-producing A. circinalis isolates with the exception of one isolate from Australia, AWQC134C. Previous biochemical studies tried to identify internal clustering of A. circinalis isolates that was not apparent from morphology; however, they proved unsuccessful (4). Other studies of toxic cyanobacteria have not found phylogenetic separation between toxic and nontoxic isolates of Cylindrospermopsis (43) and Microcystis (D. Tillett and B. A. Neilan, unpublished data). However, the phylogeny of Nodularia did reveal that the toxic species N. spumigena formed a distinct lineage (M. C. Moffitt, S. I. Blackburn, and B. A. Neilan, unpublished data). The presence of a nontoxic strain in branch I and a toxic strain in branch II questions the apparent toxicity-based bifurcation of Australian A. circinalis isolates. These discrepancies could result from toxicity variation of A. circinalis strains according to environmental and culturing conditions (30–32). This, however, seems unlikely since all A. circinalis strains analyzed were cultured under the same conditions. In addition, there are limitations on the techniques currently used to measure toxicity (19, 20, 23, 24), and growth phase regulation of toxin production has been demonstrated (25). A. circinalis grown in culture may also undergo mutations which could affect toxin production, as has been found with Microcystis aeruginosa (Tillett and Neilan, unpublished).

In this study, one A. affinis strain was found to cluster with A. circinalis isolates, suggesting the taxonomic misplacement of this isolate within the genus Anabaena. There are conflicting results about A. affinis (NIES40) forming a genetic population distinct from A. circinalis. Previous phylogenetic studies have found A. affinis to cluster with A. circinalis (26), while others have reported separate clustering of A. affinis and A. circinalis (28). Additionally, A. affinis isolates that could not be morphologically distinguished were found to form two clusters based on G+C content, fatty acid composition, and growth temperature range (18). This issue emphasizes the need for an assay targeting a stable marker, such as the 16S rRNA gene as described in this paper, for taxonomic analysis of A. affinis and A. circinalis.

As a result of this study, PCR primers to conserved regions in the A. circinalis 16S rRNA gene have been designed, allowing the specific molecular identification of A. circinalis (27Fl plus AC510R) (Table 2). Probes to conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene from branch I (ACB1F plus AC510R) and branch II (ACB2F plus AC510R) A. circinalis were also designed, allowing the rapid identification of potential PSP-producing isolates directly from cultured and environmental samples (Fig. 3). The robustness of the A. circinalis-specific and branch I- or branch II-specific probes was evaluated by analyzing environmental bloom samples consisting predominantly of cyanobacteria from the genera Anabaena and Microcystis. With the use of the specific PCRs described, it was possible to identify the presence of A. circinalis in the bloom and to further characterize isolates as potential PSP producers (Fig. 4). The test described here is the first report of a rapid method for the molecular identification of A. circinalis directly from a field sample. This PCR test was sensitive, having a detection limit of 1,000 cells ml−1, and reproducible. Results obtained with the reference strains and the environmental bloom samples validate the specificity of the diagnostic primer pairs for the 16S rDNA sequences of A. circinalis. The data here support the usefulness of the primers for the identification of A. circinalis in an environmental bloom and their characterization as potential PSP producers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council and the Cooperative Research Centre for Water Quality and Treatment.

We thank Wayne W. Carmichael (Department of Biological Sciences, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio) Peter Baker (Australian Centre for Water Quality Research), Martin Saker (James Cook University, Townsville, Australia), Peter Hawkins (Australian Water Technologies, Sydney, Australia), Susan I. Blackburn (CSIRO Marine Laboratories, Hobart, Australia), and Kaarina Sivonen (University of Helsinki) for provision of strains. E. Carolina Beltran thanks Daniel Tillett for his support and encouragement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D M. Red tides. Sci Am. 1994;271:62–68. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0894-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker P. Anabaena circinalis. In: Tyler P, editor. Identification of common noxious cyanobacteria, part 1. Nostocales. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Water Corporation; 1992. pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker P D, Humpage A R. Toxicity associated with commonly occurring cyanobacteria in surface waters of the Murray-Darling basin, Australia. Aust J Mar Freshwater Res. 1994;45:773–786. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker P D, Humpage A R, Steffensen D A. Cyanobacterial blooms in the Murray-Darling basin: their taxonomy and toxicity. Report 8/93. Adelaide, Australia: Australian Centre for Water Quality Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowling L. Occurrence and possible causes of a severe cyanobacterial bloom in Lake Cargelligo, New South Wales. Aust J Mar Freshw Res. 1994;45:737–745. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmichael W W. Cyanobacteria secondary metabolites—the cyanotoxins. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:445–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmichael W W. The toxins of cyanobacteria. Sci Am. 1994;270:78–86. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0194-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmichael W W. Toxins of freshwater algae. In: Tu A T, editor. Handbook of natural toxins, marine toxins and venoms. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1988. pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmichael W W, Biggs D F, Peterson M A. Pharmacology of anatoxin-a produced by the freshwater cyanophyte Anabaena flos-aquae NRC-44-1. Toxicon. 1978;17:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(79)90212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:166–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallacher S, Flynn K J, Franco J M, Brueggemann E E, Hines H B. Evidence for the production of paralytic shellfish toxins by bacteria associated with Alexandrium spp. (Dinophyta) in culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:239–245. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.239-245.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson C E, Smith R V. Freshwater plankton. In: Carr N G, Whitton B A, editors. The biology of cyanobacteria. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1982. pp. 463–489. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humpage A R, Rositano J, Bretag A H, Brown R, Baker P D, Nicholson B C, Steffensen D A. Paralytic shellfish poisons from Australian cyanobacterial blooms. Aust J Mar Freshw Res. 1994;45:761–771. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama M, Ogata T, Sakamoto S, Sato S, Honda T, Miwatani T. Production of paralytic shellfish toxins by a bacterium, Moraxella sp., isolated from Protogonyaulax tamarensis. Toxicon. 1990;28:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(90)90259-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodama M, Ogata T, Sato S. Bacterial production of saxitoxin. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:1075–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komarek J. Modern approach to the classification system of cyanophytes. 4. Nostocales. Arch Hydrobiol Suppl. 1989;82:247–345. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagos N, Onodera H, Zagatto P A, Andrinolo D, Azevedo S M F Q, Oshima Y. The first evidence of paralytic shellfish toxins in the freshwater cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii, isolated from Brazil. Toxicon. 1999;37:1359–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(99)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R. Ph.D. thesis. Tsukuba, Japan: University of Tsukuba; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llewellyn L E, Bell P M, Moczydlowski E G. Phylogenetic survey of soluble saxitoxin-binding activity in pursuit of the function and molecular evolution of saxiphillin, a relative of transferrin. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B. 1997;264:891–902. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llewellyn L E, Moczydlowski E G. Characterization of saxitoxin binding to saxiphillin, a relative of the transferrin family that displays pH-dependent ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12312–12322. doi: 10.1021/bi00206a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahmood N A, Carmichael W W. Anatoxin-a(s), an anticholinesterase from the cyanobacterium Anabaena flos-aquae NRC-525-17. Toxicon. 1987;25:1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(87)90140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood N A, Carmichael W W. Paralytic shellfish poisons produced by the freshwater cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon flos-aquae NH-5. Toxicon. 1986;24:175–186. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(86)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFarren E F. Report on collaborative studies of the bioassay for paralytic shellfish poison. J AOAC Int. 1959;42:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negri A, Llewellin L. Comparative analyses by HPLC and the sodium channel and saxiphillin 3H-saxitoxin receptor assays for paralytic shellfish toxins in crustaceans and molluscs from tropical north west Australia. Toxicon. 1998;36:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negri A P. Effect of culture and bloom development and of sample storage on paralytic shellfish poisons in the cyanobacterium Anabaena circinalis. J Phycol. 1997;33:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neilan B A. Detection and identification of cyanobacteria associated with toxic blooms: DNA amplification protocols. Phycologia. 1996;35:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neilan B A, Jacobs D, Del Dot T, Blackall L L, Hawkins P R, Cox P T, Goodman A E. rRNA sequences and evolutionary relationships among toxic and nontoxic cyanobacteria of the genus Microcystis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:693–697. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neilan B A, Jacobs D, Goodman A E. Genetic diversity and phylogeny of toxic cyanobacteria determined by DNA polymorphisms within the phycocyanin locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3875–3883. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3875-3883.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onodera H, Satake M, Oshima Y, Yasumoto T, Carmichael W W. New saxitoxin analogues from the freshwater filamentous cyanobacterium Lyngbya wollei. Nat Toxins. 1997;5:146–151. doi: 10.1002/1522-7189(1997)5:4<146::AID-NT4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapala J, Sivonen K. Assessment of environmental conditions that favour hepatotoxic and neurotoxic Anabaena sp. strains in culture under light-limitation at different temperatures. Microb Ecol. 1998;36:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s002489900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapala, J., K. Sivonen, R. Luukkainen, and N. S. I. 1993. Anatoxin-a concentrations in Anabaena and Aphanizomenon under different environmental conditions and comparison of growth by toxic and non-toxic Anabaena strains—a laboratory study. J. Appl. Phycol. 5:581–591.

- 32.Rapala J, Sivonen K, Lyra C, Niemela S I. Variation of microcystins, cyanobacterial hepatotoxins, in Anabaena sp. as a function of growth stimuli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2206–2212. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2206-2212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rippka R. Recognition and identification of cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:28–67. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwimmer D, Schwimmer M. Algae and medicine. In: Jackson D F, editor. Algae and man. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1964. p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shantz E J. Chemistry and biology of saxitoxin and related toxins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;479:15–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb15557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivonen K, Himberg K, Luukkainene R, Niemela S I, Poon G K, Codd G A. Preliminary characterization of neurotoxic cyanobacteria blooms and strains from Finland. Toxic Assess. 1989;4:339–352. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens D K, Krieger R I. Effect of route of exposure and repeated doses on the acute toxicity in mice of the cyanobacterial nicotinic alkaloid anatoxin-a. Toxicon. 1991;29:134–138. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90047-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tillett D, Neilan B A. n-Butanol purification of Dye Terminator sequencing reactions. BioTechniques. 1999;26:606–610. doi: 10.2144/99264bm02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tillett D, Neilan B A. Xanthogenate nucleic acid isolation from cultured and environmental cyanobacteria. J Phycol. 2000;35:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe M M, Hiroki M. NIES-collection list of strains, 5th ed. Microalgae and protozoa. Tsukuba, Japan: National Institute for Environmental Studies; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson K M, Schembri M A, Baker P D, Saint C P. Molecular characterization of the toxic cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and design of a species-specific PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:332–338. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.332-338.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]