Abstract

Background

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) are widely used for measurement of functional outcomes after orthopaedic trauma. However, PROMs rely on patient collaboration and suffer from various types of bias. Wearable Activity Monitors (WAMs) are increasingly used to objectify functional assessment. The objectives of this systematic review were to identify and characterise the WAMs technology and metrics currently used for orthopaedic trauma research.

Methods

PubMed and Embase biomedical literature search engines were queried. Eligibility criteria included: Human clinical studies published in the English language between 2010 and 2019 involving fracture management and WAMs. Variables collected from each article included: Technology used, vendor/product, WAM body location, metrics measured, measurement time period, year of publication, study geographic location, phase of treatment studied, fractures studied, number of patients studied, sex and age of the study subjects, and study level of evidence. Six investigators reviewed the resulting papers. Descriptive statistics of variables of interest were used to analyse the data.

Results

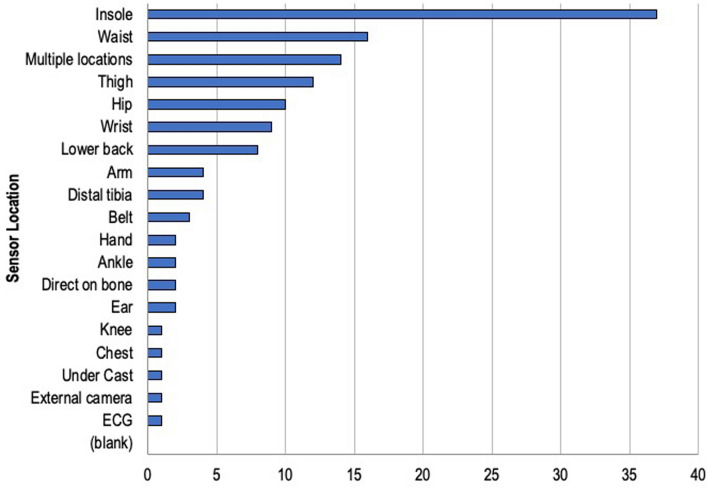

One hundred and thirty-six papers were available for analysis, showing an increasing trend of publications per year. Accelerometry followed by plantar pressure insoles were the most commonly employed technologies. The most common location for WAM placement was insoles, followed by the waist. The most commonly studied fracture type was hip fractures followed by fragility fractures in general, ankle, "lower extremity", and tibial fractures. The rehabilitation phase following surgery was the most commonly studied period. Sleep duration, activity time or step counts were the most commonly reported WAM metrics. A preferred, clinically validated WAM metric was not identified.

Conclusions

WAMs have an increasing presence in the orthopaedic trauma literature. The optimal implementation of this technology and its use to understand patients' pre-injury and post-injury functions is currently insufficiently explored and represents an area that will benefit from future study.

Systematic review registration number

PROSPERO ID:210344.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43465-022-00629-0.

Keywords: Wearable devices, Activity measurements, Orthopaedic trauma, Outcome measurements, Sensors

Introduction

Traumatic injury causes significant disability and restricts patient activity levels, resulting in decreased quality of life and work productivity [1]. One of the primary goals of orthopaedic trauma surgery is to improve patient function and activity level. The evaluation of this recovery progress requires a reliable assessment of these domains [2]. A multitude of clinical scores reported by healthcare providers have been used in the past to evaluate outcomes after orthopaedic trauma surgeries but had limited ability to measure mobility and activity [3]. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have more recently been introduced, complementing clinical scores to better determine the relevant physical function and postoperative activity outcomes [3]. However, despite their wide use, PROMs rely on patient subjective input and collaboration, often fuse domains other than function, and suffer from recall bias and observational bias (assessor, lab environment). As a result, Wearable Activity Monitors (WAMs) are increasingly used to objectify and enrich functional assessment during momentary follow-up or monitor orthopaedic trauma patients outside the lab or clinic continuously in the real-life for days, weeks or months.

To monitor the physical activity of the general consumer, wearable activity monitors (WAMs), such as smartwatches and wristbands, are increasingly being used around the world, with over 170 million systems shipped in 2018 alone [4]. This trend is also reflected in the medical literature, with a yearly increase in publications that report on WAM use [5]. The ability to assess physical activity and function objectively with digital technology represents a significant opportunity in orthopaedic trauma surgery [6]. WAM devices can allow quick, timely, objective, and detailed functional assessment metrics measurement during a brief follow-up in the hospital or laboratory. In addition, patients can be assessed continuously in real-life situations during days, weeks, or months revealing physical activity behaviour patterns. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify and characterise the different WAMs and WAM-based metrics currently used for orthopaedic trauma research and discuss their advantages, limitations, and recommended use.

Methods

Search Method and Strategy

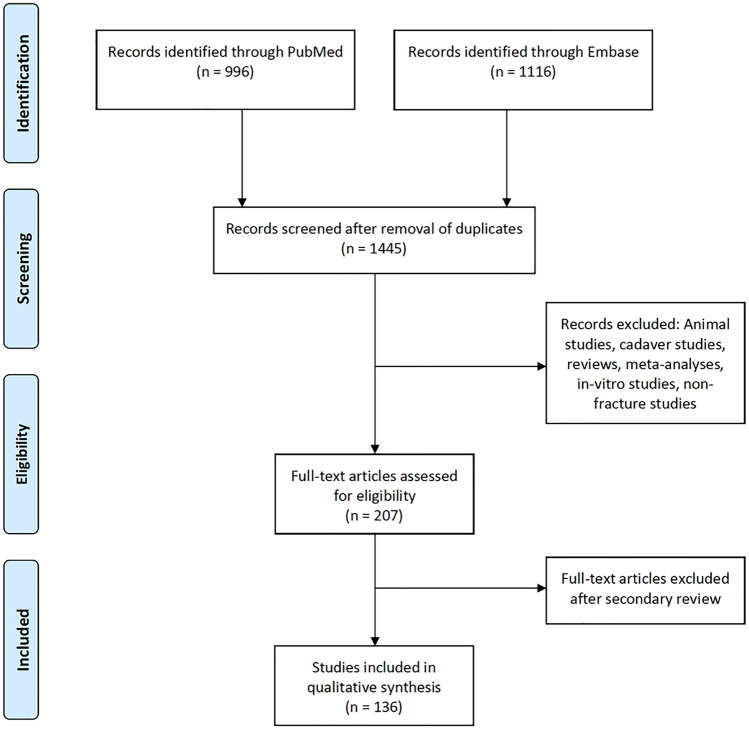

The study protocol was registered in the international prospective register for systematic reviews (PROSPERO)—Study ID:210344. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed throughout the study process[7]. A search for human studies published in English between 2010 and 2019 focused on fracture management and that made use of WAMs was performed in PubMed and Embase search engines. Animal studies, cadaver studies, reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded (Fig. 2). The full search strategy is included in the appendix.

Fig. 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study section process diagram

Study Selection

Six investigators participated in the study selection. Abstracts resulting from the search strategies in PubMed and Embase were distributed among the reviewers, with two reviewers assigned to each abstract. Each of the investigators reviewed their assigned abstracts independently. After the initial review, three of the investigators performed a secondary review of all the selected abstracts. Abstracts that were selected by their two assigned investigators were included in the study. Inclusion or exclusion of abstracts that were selected by only one of the initially assigned investigators was decided after discussion between the three secondary reviewers (Fig. 2).

Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

Prior to the data collection process, three of the investigators decided on the data items to collect and an agreed upon terminology to use when collecting the data. A spreadsheet (Google Sheets, Google, USA) was prepared with all the data items to collect and dropdown menus with the agreed terminology for each data item. Full text versions of selected abstracts were procured and reviewed by six investigators. Two investigators were assigned to each of the papers. Each investigator independently collected the data items and reviewed the collected items by their paired investigators. Discrepancies were decided and agreed upon between the assigned investigators. For each of the selected papers the following data items were collected: Technology used, vendor/product, WAM body location, metrics measured, measurement time period, year of publication, study geographic location, phase of treatment studied, fractures studied, number of patients studied, sex and age of the study subjects, and study level of evidence. Descriptive statistics were obtained using the pivot table feature of the spreadsheet. The data were then presented in a table or chart format.

Results

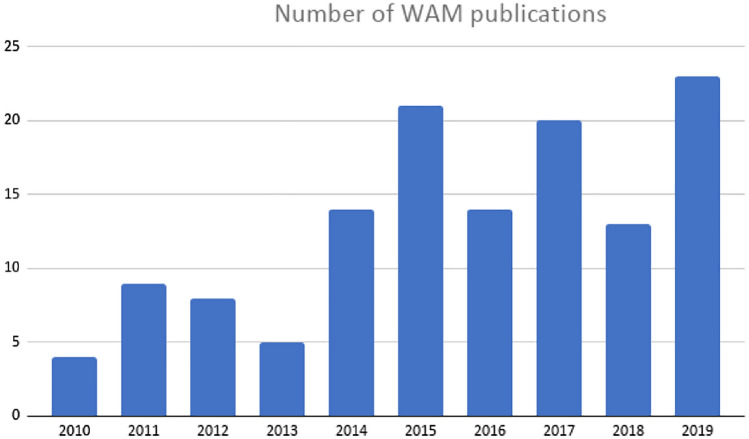

The number of studies related to activity or functional assessment with wearable systems in orthopaedic trauma is increasing yearly (Fig. 1). Our initial search produced 2112 studies, reduced to 1445 studies after removal of duplicates and to 207 studies after application of eligibility criteria. An additional 71 studies were removed after the full text of the studies was reviewed for the second time by three reviewers and determined to not focus on fractures or involve WAMs in a substantial way 136 studies were appropriate for final review (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Yearly number of orthopaedic trauma publications using Wearable Activity Monitors (WAMs)

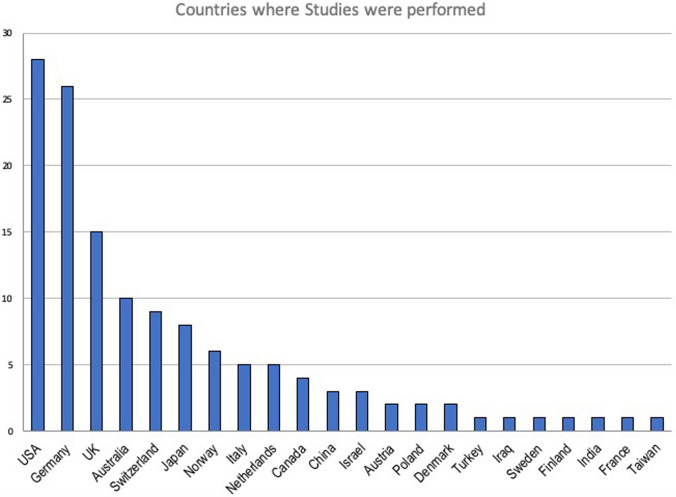

The majority of studies (65%) thus far have been performed locally in 5 countries (Fig. 3)–USA, Germany, United Kingdom, Australia and Switzerland, with substantial WAM research also done in Norway, Denmark and Israel. Most of studies were case series (level 4 evidence), but there were 25 case–control studies (level 3 evidence) and 3 low-quality randomised controlled trials (level 2 evidence). Pre-clinical studies (level 5 evidence) on healthy volunteers, intended for future use on fracture patients, constituted 21.1% of the studies.

Fig. 3.

Countries where orthopaedic trauma WAM studies were performed

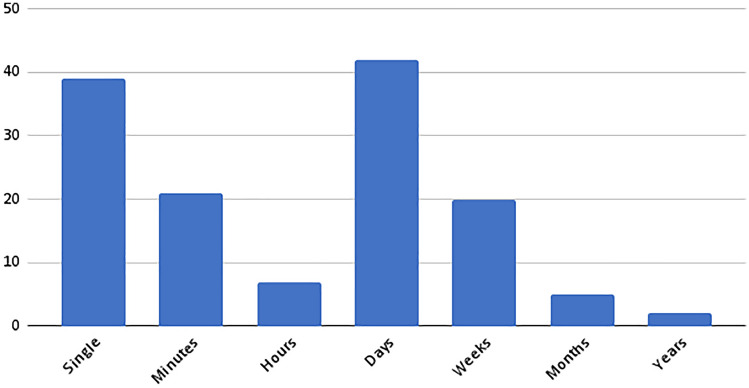

Study sample size was relatively small, with < 10 patients enrolled in 8.3% of the studies, 10–50 patients enrolled in 61% of the studies, and 51–100 patients enrolled in 13.5% of the studies. Studies with 101–500 patients constituted 6.8% of the studies and studies of > 500 patients 10.5%. The study duration was also relatively short, with most studies collecting data over a number of days or as a single measurement such as a functional assessment in the hospital or laboratory settings (Fig. 4). Just over half of the studies measured for day(s) or longer, thus aiming to assess real-world activity behaviour instead of an instrumented short functional test.

Fig. 4.

Location of sensor in orthopaedic trauma WAM studies as they were recorded. Locations such as waist and belt, wrist and arm may be equivalent

The focus of these studies was most commonly fragility fractures, particularly around the hip (Table 1), with the most commonly studied treatment phase being rehabilitation (58.6%) followed by fracture prevention (17.3%).

Table 1.

Primary population studied in fracture studies using Wearable Activity Monitors

| Primary patient population studied | # of studies (n = 136) |

|---|---|

| Hip fractures | 33 |

| Fragility fractures | 21 |

| Ankle and foot fractures | 19 |

| Healthy subjects | 18 |

| Lower extremity fractures | 12 |

| Spine fractures | 8 |

| All fractures | 8 |

| Stress fractures | 7 |

| Tibia fractures | 5 |

| Proximal humerus | 2 |

| Distal radius fractures | 2 |

| Forearm fractures | 1 |

The most common technology used was accelerometery followed by plantar pressure insoles (Table 2). The devices were most commonly placed in the insole, closely followed by the hip/thigh/waist area (Fig. 5) which can be assumed as comparable by usability aspects and algorithmically derivable metrics. The most common metric class to be measured was overall activity level or behavioural (e.g. daily step counts, sleep duration, activity time), followed by kinetic gait parameters (e.g. weight bearing) and metrics derived from accelerations such as intensity counts and raw accelerometery (Table 3). No particularly dominant, preferred, clinically validated WAM metric or one best correlated with fracture healing or rehabilitation status was identified.

Table 2.

Technology used in orthopaedic trauma WAM studies

| WAM technology used | Study # (n = 136) |

|---|---|

| Accelerometer | 62 |

| Plantar pressure | 36 |

| Combined system | 13 |

| Pedometer | 6 |

| Smartphone | 5 |

| Inertial sensor | 3 |

| Accelerometer + force plate | 3 |

| Other | 2 |

| Bend/strain sensor | 2 |

| Video analysis | 1 |

| Heart rate sensor | 1 |

| Accelerometer + temperature | 1 |

| Pedometer/accelerometer | 1 |

WAM wearable activity monitor

Fig. 5.

Measurement period in orthopaedic trauma WAM studies. Single measurements and likely minutes are more a functional test assessed with sensors, then a monitoring activity

Table 3.

Metrics used in orthopaedic trauma WAM studies

| WAM metric used | Study # (n = 136) |

|---|---|

| Activity (derived) | 49 |

| Kinetic gait parameters* | 34 |

| Acceleration (raw) derived | 27 |

| Kinematic parameters ** | 12 |

| Temporal gait parameters *** | 5 |

| Energy expenditure | 3 |

| Fall detection | 2 |

| Video assessment | 1 |

| Orthotic use compliance | 1 |

| Kinetic + temporal parameters | 1 |

| Heart rate | 1 |

*Kinetic Gait Parameters: metrics based on pressure, force and gait (i.e. ground reaction force, centre of pressure, pressure distribution, loading rate, loading integral, etc.)

**Kinematic Parameters: metrics related to skeletal displacements such as joint angles, range of motion, walking speed, step length

***Temporal Gait Parameters: measures that have to do with gait timing (i.e. cadence, cycle time, stance time, swing time, time on feet, double support time, etc.)

Discussion

This study is the first comprehensive review of the use of WAMs in orthopaedic trauma. While WAMs have not yet gained a central role in outcomes measurement in orthopaedic trauma research, it is possible to observe clear trends and common practices.

Publications on Wearable Activity Measurement Devices

The use of WAMs in orthopaedic trauma research is increasing (Fig. 1). However, the quality of research remains low despite this trend, with very few large global multi-centre fracture-related studies that use WAM devices for outcome measurements. Besides using WAMs for remote, objective and patient-centric monitoring of fracture healing and rehabilitation for outcome assessment, WAMs have also been used for monitoring compliance to activity interventions and as an intervention by themselves providing activity feedback towards improving therapy. In one low-quality (level 2) randomised controlled trial of 1321 participants, pedometers were used to monitor and verify compliance to a 12-week physical activity intervention that resulted in significant reductions in falls and fractures in four years [8]. In another randomised trial, 240 hip fracture patients were randomised to receive occupational therapy alone or combined with a WAM and a motion sensor that the therapist could use for feedback [9]. WAM and motion sensor-assisted occupational therapy resulted in significantly better functional improvement [9]. The results of these studies are encouraging and suggest the benefits of incorporating WAM-based assessments for compliance monitoring, as intervention by feedback or outcome measurements into future orthopaedic trauma outcome studies. For unbiased outcome assessment, certain WAMs metrics may need to be blinded to the patient. Future clinical use of WAMs for patient outcome measurement will primarily rely on high-quality research demonstrating benefits to patients and providers alike.

Technologies Used in Orthopaedic Trauma WAM Studies

Contemporary research-grade, clinical-grade and consumer-oriented WAM devices use a myriad of available technologies (Table 2). An analysis focused on each specific wearable technology is thus beyond the scope of this paper and may not be feasible due to rapid market developments. However, this systematic review demonstrates the broader trends and areas of interest in the use of WAMs in orthopaedic trauma research.

Over half of all publications used accelerometry-based technology. Measuring periods were more extended than other WAM technologies and constituted of days and weeks, compared to single time momentary measurements. Accelerometry-based WAMs are also commonly used in other medical fields, such as neurology rehabilitation medicine, and geriatrics [10]. Accelerometry-based wearables are highly available in both the consumer and medical markets. Their availability, ease of use, long measurement times, and relatively low price have made them popular tools with established validity for some acceleration signal analysis algorithms, particularly for more extended measurement periods and in geriatric populations [10]. Accelerometer-based WAMs have also been used to motivate patients to increase their physical activity participation [11]. While this can be used positively towards clinical benefit (e.g. faster recovery) during trauma healing, in certain comparative study designs direct patient feedback of WAM metrics may need to be well controlled. Accelerometers, however, also have limitations. The accuracy of accelerometer derived physical activity metrics such as step counts is dependent on their placement, can vary between systems and is influenced by the patients gait speed [12]. In addition, accuracy is decreased with patients using typical orthopaedic walking aids (crutches and walkers) [13]. Furthermore, homebound patients rarely carry their phone/device around the house, thereby reducing the measurement periods unless dedicated permanently body-worn form factors are used (e.g. belt, watch, sticker).

Plantar pressure measuring systems, primarily instrumented insoles, were the second most common technology used (26% of studies). These systems register the plantar pressures generated by weight-bearing on the insoles, then calculate resulting forces, as well as gait-related timing parameters. Most of these systems can also measure accelerometry-associated parameters through either tri-axial accelerometry or gyroscopes embedded in their design. Plantar pressure sensing WAMs are commonly used in situations that require evaluation of weight-bearing recommendations, pathological plantar pressures, or as input for computer simulations of biomechanical fracture environments [14]. In addition, these WAMs can relay loading information to the patient through feedback loops and influence postoperative weight-bearing behaviour, such as reduce the risk of fracture occurrence through load pattern modification [15].

Interestingly, despite their high prevalence and ability to function as WAMs, smartphones were not commonly used in orthopaedic trauma research. Smartphones were most prevalent in studies involved in remote imaging review [16]. The few studies identified in our review used either the phone's camera system, accelerometer, or video playback to relay training instructions. With more commercially available applications to determine activity and health associated measures on smartphones, their use to determine baseline activity and outcome in the context of injury is likely to increase over the coming years. Variable wear locations and on-body wear time of smartphones are systematic and signal algorithmic challenges that must be overcome.

All other systems were only used in a small percentage of studies. Simple step counting devices in the form of pedometers were used in 5% of the identified literature. They can be used much in the same way as accelerometry to determine the total number of steps over a given time. However, the simple activity measurement of pedometers is much more limited in determining activity than accelerometry [17] which can, e.g. include the distribution of gait event durations, intensity classifications, walking cadence or speed or else.

WAM-Derived Metrics for Orthopaedic Trauma Outcome Assessment

The most prevalent metrics assessed were derived activity parameters, including time spent during gait, time spent at certain activity levels, activity types, and the number of daily steps taken. It is possible to assess derived activity parameters using accelerometry, plantar pressure measuring insoles, inertial measurement units (IMUs), pedometers, smartphones or combined systems. Clinical use of these metrics is possible for outcome assessment, activity encouragement, before or after fracture, decreasing fall risk or fear of falling, and an overall increase in function and health [5]. Current reviews show that commercially available systems are sufficiently accurate for calculating simple derived accelerometry values such as steps but less accurate when calculating detailed energy expenditure and more specific gait parameters under free field conditions. Research grade or clinical grade provides more detailed accelerometer metrics that can determine fall risk, stability and help prevent stress or fragility fractures [18].

The second most common metric assessed were kinetic gait, or ground reaction force parameters, primarily derived from plantar pressure sensing insoles. They are most prevalent in lower extremity fracture studies assessing weight-bearing and plantar pressure characteristics: They have added value when looking at gait pattern changes during injury rehabilitation and gait retraining in foot and ankle conditions, as well weight-bearing issues in more proximal entities [19]. Furthermore, they can serve as input to computer simulations looking at fracture healing and the associated biomechanical boundary conditions [20]. Kinematic parameters concerning joint angles and range of motion were assessed with smartphone cameras, accelerometers, as well as gyroscopes and IMUs [21]. Similar to temporal and spatial gait parameters (e.g. walking speed, step length, step time), they were mainly used in the treatment recovery and rehabilitation phase [22]. Kinetic and Kinematic gait parameters generally have the advantage of allowing comparison of the injured to the normal side (such as ground reaction force, range of motion). However, derived activity and temporo-spatial parameters (such as active/sedentary time, step count, walking speed) require a comparison to baseline (pre-injury) values or the average age-matched values to be appropriately interpreted. These parameter values are often not available for fracture patients, as they are only included into studies after their injury.

Body Location of WAMs in Orthopaedic Trauma Research

In the current review, the most common location for WAM placement was shoe insoles, followed by the waist/thigh/hip area, wrist and lower back (Fig. 5). However, the ideal location of a WAM from a technical (reliability and accuracy of the derived metrics) point of view may not be the ideal location for patient usability (easily accessible and quickly taken on and off). In addition, WAM position also influences the amount of time it can be worn and its ability to communicate with other devices.

The insole position absorbs all of the body's weight and is ideal for measuring kinetic metrics, such as ground reaction forces, plantar pressure, and loading distribution. However, compliance is commonly dependent on using a specific shoe, which is susceptible to wear if prolonged use is required. In this review, only 29% of the studies used insole WAMs for more than a week and 10% for more than a month. Insoles can also be used to measure activity metrics such as step count and temporo-spatial gait parameters such as stride, stance, swing and step time [23].

If taken collectively, the thigh, waist and hip are the most common locations for a fracture-related WAM. Raw accelerometry data was measured and put out more commonly in the waist and hip locations, and in the thigh location, perhaps due to the sensor undergoing larger and faster displacements. While uses for hip and waist WAMs were variable, all thigh located WAMs used accelerometry technology and were implemented in the rehabilitation phase of fracture management (hip fracture in 10 of 12 studies). Taken together, WAMs placed in the waist, lower back, hip and thigh areas are excellent for deriving temporo-spatial and general activity metrics but limited in their ability to measure kinetic parameters [24]. Their accuracy and reliability are relatively high compared to other WAMs; however, they are generally harder to place on patients, and patients are less likely to position the WAMs themselves or be able to take them on and off [25].

According to the current review, WAMs in the wrist location are used much less than the insole and hip/waist area. In the reviewed studies, wrist WAMs most commonly used accelerometry technology to measure either raw accelerometry data or derived activity data over hours to days. The fractures studied with wrist WAMs were typically hip fractures and fragility fractures in general. Interestingly, wrist WAMs were not commonly used for upper extremity fracture studies. In the current review, most upper extremity studies focused on kinematic parameters (e.g. range of motion) obtained in one sitting using variable technologies. Wrist WAMs are very common in commercial-grade activity monitoring and, therefore, may be more acceptable to patients. Additional benefits of the wrist location include ease of use, the ability to take it on and off or keep it on all day (including sleep time) and for several days without needing removal [25]. However, wrist-based measurements may suffer from inaccuracies and are generally limited to temporo-spatial and general activity metrics [12].

Duration of Measurement Using WAMs

WAMs can be used to measure activity over a wide variety of time periods. In the current review, measurement periods varied from a single measurement or a few minutes to years (Fig. 4). When WAM-derived metrics are measured during a very short assessment period (seconds, minutes), they usually objectify a functional test to describe a momentary capacity. When used over short periods (hours to a day), they can be thought of as “activity biopsies”, representing the current ability of the patient to be active in an unobserved situation and can be repeated at various follow-up moments for a longitudinal assessment. However, longer measurement times (days to week(s) and month(s)) give a more complete and accurate assessment of how active the patients are after their surgery in the real life (activity behaviour).

The majority of studies recorded data for days but less than a week. For example, one study used cadence, Metabolic Equivalents (METs), and an activity score monitoring for three days in patients on an orthopaedic rehabilitation ward after a lower extremity injury [26]. Most of these studies derived activity data from accelerometers and pedometers, with various measured metrics, including raw activity data, fall detection, kinetic gait parameters and temporal gait parameters. Study sizes varied, but seven of these recruited > 500 participants.

Studies that used a single activity measurement most commonly measured either kinematic parameters, kinetic gait characteristics utilising insoles, or accelerometry data. Many were small studies examining specific measurements like a smartphone application that measured forearm supination in patients with distal radius fractures, pedobarograms in patients with calcaneus fractures or shoulder range of motion using a smartphone [27]. Studies that used WAMs over periods lasting minutes had a similar profile to the single measurement studies but focused more on patient movement/ambulation. For example, one of these studies compared gait and trunk movement between those with a history of ankle fracture and controls. Another study correlated accelerometry-based gait analysis with fall risk in patients with a recent fracture [28]. The vast majority of studies in the single-measurement and minutes-measurement period groups had < 50 participants, most likely due to the equipment's relative costs and the controlled laboratory conditions under which most took place.

WAM measurements over more extended periods were not common in our review. Only seven publications reported on measurement periods over one month. One of these studies measured hip protector compliance using accelerometry. Two studies from the Nakanojo study group recorded data using an accelerometer/pedometer which looked at continuously collected data on 496 elderly people, with data reported at 5 and 10 years, respectively [29]. The metrics collected in more extended measurement periods tended to be less complex. More work is needed to determine the feasibility, durability, and necessity of long-term monitoring. From a practical perspective, it may not be necessary to continuously record patients for long periods, as this may lead to equipment breakdown and non-compliance. In many cases, longitudinally repeated single time point measurements of short duration (“activity biopsies”) may be more cost-effective and practical.

Fracture Management Using WAMs

The use of WAMs may differ for specific fractures. In this review, WAMs were most commonly for lower extremity fractures, but use in upper extremity and spine fractures was also demonstrated. The most commonly included fracture type was hip fractures followed by ankle and tibial fractures (Table 1). WAMs offer various ways to assess recovery and rehabilitation after hip fractures. For example, hip fracture patients were shown to exceed recommended weight-bearing restrictions [14]. In another study, WAMs demonstrated that partial weight-bearing status reduces postoperative mobility and lowers gait speed [30]. Hip fracture patients were also shown to spend more time in upright positions and have overall better WAM-measured lower limb function early after surgery with additional geriatric care [31].

Insole-based WAM measurement helps measure other lower extremity fracture surgery outcomes (tibia, ankle, foot), such as compliance with weight-bearing restrictions [32] or the evaluation of different post-fracture treatments [33]. During the rehabilitation of calcaneal fractures, a reduction of walking speed and medial plantar loading of the midfoot and forefoot compared to patients with Achilles tendon tears could be found [34]. In addition, changes in gait patterns and restricted function were seen in talar fractures and ankle fractures [35]. These studies suggest that WAMs may help in the future to individualise post-surgery protocols and optimise outcomes.

Activity measurement of the upper extremity is more complex because weight-bearing is not helpful as an outcome parameter. It is also difficult to classify activity into a few dominant types as done for the lower extremity (e.g. lying, sitting, standing, walking). Zucchi et al. showed superior efficacy of volar plate compared to Kirschner wire fixation in terms of ROM improvement in ulnar deviation and supination using IMU (3-axis gyroscope, 3-axis accelerometer, magnetometer) at least 12 months after surgery. In addition, EMG and handgrip strength was tested, which showed increased muscle fatigue in the volar plate group [36]. Another approach for measurement of ROM in patients with distal radius fracture was with a camera wrist tracker, consisting of a webcam-based optical tracking device and a hand-held LED unit. The authors were able to show that this technique provides reliable scores for dynamic wrist extension ROM, and moderately reliable scores for flexion, in people recovering from a distal radius fracture [37]. As the accessibility of inertial systems is limited, Pichonnaz et al. investigated the use of smartphones to evaluate the shoulder function after proximal humerus fractures. They demonstrated that shoulder function score and arm elevation angle measurements using the Smartphone were highly reproducible and highly correlated with the reference system [38].

WAMs were used in various ways in eight studies involving spinal fractures included in this review. In vertebral compression fractures, the range of motion did not change, but velocity and amplitude increased postoperatively and 12 weeks after balloon kyphoplasty [39]. In another study, bone shock absorption damping was lower and postural imbalance was higher in patients with osteoporosis with vertebral fractures than in a similar non-fracture group [40].

Key Insights

In recent years, there has been increased interest in wearable activity measurement devices in orthopaedic trauma outcomes research.

The most common use of WAMs is for monitoring the rehabilitation of lower extremity fractures.

The leading WAM technology is accelerometry, primarily used for measuring step counts, activity, and sleep duration.

The role of WAMs versus PROMs in outcomes research, as well as, the preferred technology and metrics for assessing outcome will need to be explored in future large clinical trials.

Limitations

This work constitutes the first systematic review on the use of wearable devices of functional and physical activity assessment in orthopaedic trauma management. The review has been done according to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and was registered in the PROSPERO registry for systematic reviews [10, 11]. However, this review also has some notable limitations. As is the case with any technology review, the development of new technology often outpaces the speed it takes to create such a review. As a result, this review may not include important new WAM applications that have been published after the review period. Furthermore, while the review was focused on WAM applications for orthopaedic trauma, similar applications for other orthopaedic and non-orthopaedic fields that may be relevant for orthopaedic trauma patients have not been covered in this work. Finally, this review may also suffer from biases such as selection bias, publication bias and English language bias. Although these biases are important, and a few important studies may have been missed, the authors believe that the importance of this first systematic review on the use of WAMs in orthopaedic trauma is primarily to bring attention to this field and promote interest in the use of WAMs in future orthopaedic trauma outcome studies.

Conclusions

WAMs have an emerging presence in the orthopaedic literature and in evaluating outcomes after orthopaedic trauma surgery. Accelerometry followed by plantar force measurements were the most common technologies used, and hip fractures and fragility fractures, in general, were the most commonly studied injuries. Devices were most commonly worn in the insole for a few days and during the rehabilitation phase of treatment, but a wide variety of body locations and measurement times were reported. WAMs can help measure outcomes including providing objective evidence for superior function or physical activity in comparative studies and personalise treatment plans. Future, more detailed and focused, systematic reviews are needed to decide the optimal technology, location, and metrics for a specific fracture management application.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This study was funded by the AO Foundation.

Availability of Data and Materials

Raw data from this work are available on Dryad Digital Repository: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/-Vxhqgfd2VWhBRJMJvlZxP7X-Xb2CgJzf_Ch0qcySVs.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study is a systematic review of the medical literature and is exempt from ethical approval.

Consent to Participate

N/A.

Consent to Publish

N/A.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Davis KA, Fabian TC, Cioffi WG. The toll of death and disability from traumatic injury in the United States—the ‘neglected disease’ of modern society, still neglected after 50 years. JAMA surgery. 2017;152(3):221–222. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothrock NE, et al. Validation of PROMIS physical function instruments in patients with an orthopaedic trauma to a lower extremity. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2019;33(8):377–383. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner GM, et al. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in trauma. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2019;86(2):314–320. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.M. Framingham, (2019) IDC Reports Strong Growth in the Worldwide Wearables Market, Led by Holiday Shipments of Smartwatches, Wrist Bands, and Ear-Worn Devices. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190305005268/en/IDC-Reports-Strong-Growth-in-the-Worldwide-Wearables-Market-Led-by-Holiday-Shipments-of-Smartwatches-Wrist-Bands-and-Ear-Worn-Device. Accessed August 20, 2021.

- 5.T. Strain et al., (2020) Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nature Medicine, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Braun BJ, et al. Finding NEEMO: Towards organizing smart digital solutions in orthopaedic trauma surgery. EFORT Open Reviews. 2020;5(7):408–420. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.200021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris T, et al. Effect of pedometer-based walking interventions on long-term health outcomes: Prospective 4-year follow-up of two randomised controlled trials using routine primary care data. PLOS Medicine. 2019;16(6):e100283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pol MC, Ter Riet G, van Hartingsveldt M, Kröse B, Buurman BM. Effectiveness of sensor monitoring in a rehabilitation programme for older patients after hip fracture: A three-arm stepped wedge randomised trial. Age and Ageing. 2019;48(5):650–657. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimm B, Bolink S. Evaluating physical function and activity in the elderly patient using wearable motion sensors. EFORT Open Reviews. 2016;1(5):112–120. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.160022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickwood K-J, Watson G, O’Brien J, Williams AD. Consumer-based wearable activity trackers increase physical activity participation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7(4):e11819. doi: 10.2196/11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow JJ, Thom JM, Wewege MA, Ward RE, Parmenter BJ. Accuracy of step count measured by physical activity monitors: The effect of gait speed and anatomical placement site. Gait & Posture. 2017;57:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alinia P, Cain C, Fallahzadeh R, Shahrokni A, Cook D, Ghasemzadeh H. How Accurate Is Your Activity Tracker? A Comparative Study of Step Counts in Low-Intensity Physical Activities. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2017;5(8):e106. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kammerlander C, Pfeufer D, Lisitano LA, Mehaffey S, Böcker W, Neuerburg C. Inability of older adult patients with hip fracture to maintain postoperative weight-bearing restrictions. JBJS. 2018;100(11):936–941. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tirosh O, Steinberg N, Nemet D, Eliakim A, Orland G. Visual feedback gait re-training in overweight children can reduce excessive tibial acceleration during walking and running: An experimental intervention study. Gait & Posture. 2019;68:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahl I, Katsman A, Zaidman M, Keshet D, Sigal A, Eidelman M. Reliability of smartphone-based instant messaging application for diagnosis, classification, and decision-making in pediatric orthopedic trauma. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2019;35(6):403–406. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmal H, Holsgaard-Larsen A, Izadpanah K, Brønd JC, Madsen CF, Lauritsen J. Validation of activity tracking procedures in elderly patients after operative treatment of proximal femur fractures. Rehabilitation Research and Practice. 2018;2018:3521271. doi: 10.1155/2018/3521271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice HM, Saunders SC, McGuire SJ, O’Leary TJ, Izard RM. Estimates of tibial shock magnitude in men and women at the start and end of a military drill training program. Military Medicine. 2018;183(9–10):e392–e398. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A. M. Eickhoff, R. Cintean, C. Fiedler, F. Gebhard, K. Schütze, and P. H. Richter, (2020) Analysis of partial weight bearing after surgical treatment in patients with injuries of the lower extremity. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, Sep, p.1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Braun BJ, et al. An individualized simulation model based on continuous, independent, ground force measurements after intramedullary stabilization of a tibia fracture. Archive of Applied Mechanics. 2019;89(11):2351–2360. doi: 10.1007/s00419-019-01582-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reenalda J, Maartens E, Buurke JH, Gruber AH. Kinematics and shock attenuation during a prolonged run on the athletic track as measured with inertial magnetic measurement units. Gait & Posture. 2019;68:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson J, Nordström A, Nordström P. Greater fall risk in elderly women than in men is associated with increased gait variability during multitasking. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2016;17(6):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagos H, et al. Mobile gait analysis via eSHOEs instrumented shoe insoles: A pilot study for validation against the gold standard GAITRite®. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology. 2017;1(5):375–386. doi: 10.1080/03091902.2017.1320434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngoh KJ-H, Gouwanda D, Gopalai AA, Chong YZ. Estimation of vertical ground reaction force during running using neural network model and uniaxial accelerometer. Journal of Biomechanics. 2018;76:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arvidsson D, Fridolfsson J, Börjesson M. Measurement of physical activity in clinical practice using accelerometers. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2019;286(2):137–153. doi: 10.1111/joim.12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peiris CL, Taylor NF, Shields N. Patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for lower limb orthopaedic conditions do much less physical activity than recommended in guidelines for healthy older adults: An observational study. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2013;59(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid S, Egan B. The validity and reliability of DrGoniometer, a smartphone application, for measuring forearm supination. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2019;32(1):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto H, et al. Accelerometry-based gait analysis predicts falls among patients with a recent fracture who are ambulatory: A 1-year prospective study. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2015;38(2):131–136. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shephard RJ, Park H, Park S, Aoyagi Y. Objective Longitudinal Measures of Physical Activity and Bone Health in Older Japanese: The Nakanojo Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017;65(4):800–807. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima K, Anzai E, Iwakami Y, Ino S, Yamashita K, Ohta Y. Measuring gait pattern in elderly individuals by using a plantar pressure measurement device. Technology and Health Care. 2014;22(6):805–815. doi: 10.3233/THC-140856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taraldsen K, et al. Physical behavior and function early after hip fracture surgery in patients receiving comprehensive geriatric care or orthopedic care—a randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014;69(3):338–345. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun BJ, et al. Weight-bearing recommendations after operative fracture treatment—fact or fiction? Gait results with and feasibility of a dynamic, continuous pedobarography insole. International Orthopaedics. 2017;41(8):1507–1512. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus TM, Graf F, Mitternacht J, Döbele S, Stöckle U, Siebenlist S. Vacuum shoe system vs. forefoot offloading shoe for the management of metatarsal fractures. A prospective, randomized trial. MMW Fortschritte de Medizin. 2014;156(1):11–17. doi: 10.1007/s15006-014-2877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albin SR, Cornwall MW, McPoil TG, Van Boerum DH, Morgan JM. Plantar Pressure and Gait Symmetry in Individuals with Fractures versus Tendon Injuries to the Hindfoot. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2015;105(6):469–477. doi: 10.7547/14-073.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbaz A, et al. Lower extremity kinematic profile of gait of patients after ankle fracture: A case-control study. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2016;55(5):918–921. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zucchi B, et al. Movement analysis with inertial measurement unit sensor after surgical treatment for distal radius fractures. Biores Open Access. 2020;9(1):151–161. doi: 10.1089/biores.2019.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SheferEini D, et al. Camera-tracking gaming control device for evaluation of active wrist flexion and extension. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2017;30(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pichonnaz C, et al. Comparison of a dedicated body-worn inertial system and a smartphone for shoulder function and arm elevation evaluation. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:e1205–e1206. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.2133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Druschel C, Schaser K-D, Rohlmann A, Pirvu T, Disch AC. Prospective quantitative assessment of spinal range of motion before and after minimally invasive surgical treatment of vertebral body fractures. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2014;134(8):1083–1091. doi: 10.1007/s00402-014-2035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhattacharya A, Watts NB, Dwivedi A, Shukla R, Mani A, Diab D. Combined measures of dynamic bone quality and postural balance–a fracture risk assessment approach in osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Densitometry. 2016;19(2):154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data from this work are available on Dryad Digital Repository: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/-Vxhqgfd2VWhBRJMJvlZxP7X-Xb2CgJzf_Ch0qcySVs.