Abstract

Objective

To identify and synthesize original research on contraceptive user values, preferences, views, and concerns about specific family planning methods, as well as perspectives from health workers.

Study design

We conducted a systematic review of global contraceptive user values and preferences. We searched 10 electronic databases for qualitative and quantitative studies published from 2005 to 2020 and extracted data in duplicate using standard forms.

Results

Overall, 423 original research articles from 93 countries among various groups of end-users and health workers in all 6 World Health Organization regions and all 4 World Bank income classification categories met inclusion criteria. Of these, 250 (59%) articles were from high-income countries, mostly from the United States of America (n = 139), the United Kingdom (n = 29), and Australia (n = 23). Quantitative methods were used in 269 articles, most often cross-sectional surveys (n = 190). Qualitative interviews were used in 116 articles and focus group discussions in 69 articles. The most commonly reported themes included side effects, effectiveness, and ease/frequency/duration of use. Interference in sex and partner relations, menstrual effects, reversibility, counseling/interactions with health workers, cost/availability, autonomy, and discreet use were also important. Users generally reported satisfaction with (and more accurate knowledge about) the methods they were using.

Conclusions

Contraceptive users have diverse values and preferences, although there is consistency in core themes across settings. Despite the large body of literature identified and relevance to person-centered care, varied reporting of findings limited robust synthesis and quantification of the review results.

Keywords: Contraception, Health worker preferences, Patient preferences, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Understanding the values and preferences of contraceptive users is an important component of good healthcare practice at clinical, community, and health system levels, and can ultimately support contraceptive users in identifying and using a method that suits their needs and enables them to meet their family planning goals. Choice—or rather, optimizing choice—is a fundamental principle that guides efforts to strengthen the quality of family planning and contraceptive services [1]. At the clinical level, health workers will be better equipped to work with clients to meet each individual's reproductive health needs if they have an understanding of user values and preferences. Community-level support for contraceptive use, which may include awareness and access through local health workers and pharmacists, media campaigns, and large-scale training and information activities, will benefit from greater understanding of the range of values and preferences. At the health system level, service providers will be better able to respond to unmet need for family planning and empower individuals to access and use preferred contraceptive methods if they are attuned to what end-users value and prefer.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use [2] and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use [3] guidelines present information on the safety of various contraceptive methods in the context of specific health conditions and personal characteristics, and how to safely and effectively use a particular method once a person is deemed medically eligible. WHO's guideline development process [4], considers the values and preferences of end-users of contraception and health workers—the individuals and populations affected by the intervention—within the review and development of these guidelines. To inform updated versions of these guidelines, we conducted a systematic review using systematic search, screening, and data abstraction methods to examine values and preferences for all of the contraceptive methods covered. In this manuscript, we present our overall findings from the global review [5,6]. Additional papers in this series detail values and preferences for specific populations of contraceptive end-users and health workers [7–11].

2. Methods

We conducted this review according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [12]. We previously published a detailed description of the methods for the review [6].

Briefly, we searched 10 electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, Scopus, LILACS, WHO Global Health Libraries, Ovid Global Health, Embase, and POPLINE), secondary-searched several relevant review articles [[13], [14], [15], [16]–17], and asked experts in the field to identify articles published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 1, 2005 and July 27, 2020. Articles had to present primary data (qualitative or quantitative) on contraceptive clients’ or health workers’ values, preferences, views, or concerns regarding the contraceptive methods considered within the WHO's Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use guidelines. To keep the review as broad as possible, we set no restrictions based on language of publication, country/setting, or study design. We searched using key terms for contraception and contraceptive methods, values and preferences, and elimination of irrelevant studies (such as animal studies) and adapted terms for each of the 10 databases.

We first conducted title/abstract screening, then secondary screening in duplicate with discrepancies resolved by discussion and consensus. Inclusion in the global review was determined after full-text review in duplicate. We abstracted data using standardized forms developed specifically for this project, gathering information on: citation, location, target population, study design, sample size, key quantitative or qualitative results, and study rigor (using the Evidence Project Risk of Bias tool [18] for quantitative findings and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative research checklist [19] for qualitative findings). We iteratively coded themes that encapsulated values and preferences of end-users and health workers, and we ranked themes by frequency of mention. We summarized coded results narratively to capture main findings related to values and preferences. Due to the large number of included articles, we generally do not include citations to individual articles in the results presented below; instead, we only cite specific papers when providing illustrative quotes or statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

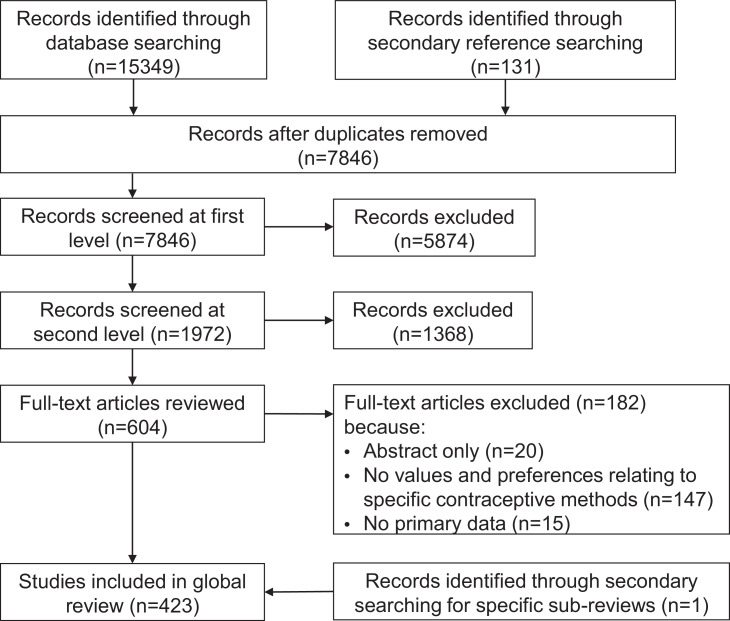

We identified 15,349 potential articles through our search process and an additional 131 through secondary reference searching of included articles, relevant reviews, and specific population subanalyses (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, we screened the titles/abstracts of 7846 articles and reviewed the full text of 604 articles. Ultimately, 423 articles reporting data from 412 studies met our inclusion criteria. Below, we present an overview of findings from this global review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart presenting the search and screening process for the contraceptive values and preferences global review 2005-2020.

3.2. General characteristics of included studies

Summary characteristics of the included articles are provided in the study description table, organized by geographic WHO region (Tables 1A–1F). The Contraceptive Health Research of Informed Choice Experience (CHOICE) study, a large European multicountry study, was reported in 10 articles [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]–29], and the Contraceptive CHOICE study on long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods in Missouri, the United States of America (USA), was reported in 4 articles [[30], [31], [32]–33]. The 410 studies (reported in 423 articles) included 463,048 participants; individual study sample sizes ranged from 10 (a qualitative study on intrauterine devices (IUDs) in the United Kingdom [34]) to 70,016 (a cross-sectional analysis of a national household survey in India [35]).

Table 1B.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Hashim 2012 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.012 | Egypt: Mansoura | Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Jamali 2014 | 10.4103/2231-4040.143025 | Iran | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Kariman 2014 ARABIC | sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=364280 | Iran: Zahedan | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Rahmanpour 2010 | PMID: 21381574 | Iran: Zanjan | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Rahnama 2010 | 10.1186/1471-2458-10-779 | Iran: Tehran | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Shirvani 2008 FARSI | hayat.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=169 | Iran: Ghaemshahr | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Baram 2020 | 10.1080/13625187.2019.1699048 | Israel | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Romer 2009 | 10.3109/13625180903203154 | Multicountry: Austria; Bulgaria; Estonia; France; Germany; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Jordan; Latvia; Lebanon; Lithuania; Malta; Netherlands; Poland; Russia; Spain; Ukraine | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Xu 2014 | 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.019 | Multicountry: China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Korea, Thailand | Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Lendvay 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.002 | Multicountry: Kenya: Nairobi; Pakistan: Sindh, Punjab | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Azmat 2012 | ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi? article=1895&context=pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs | Pakistan: Punjab, Sindh | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Naqaish 2012 | PMID: 23855088 | Pakistan: Islamabad | General (female), Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Nishtar 2013 | 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p84 | Pakistan: Kirachi: Nasir Colony and Chakra Goth | Young people (mixed gender), Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| Karim 2015 | 10.12669/pjms.316.8127 | Saudi Arabia: Riyadh | General (female) | Quantitative |

Table 1C.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO European Region 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodner 2011 | 10.1007/s00404-010-1368-6 | Austria: multiple sites | Young people (female), General (female) | Quantitative |

| Egarter 2012 | 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.12.003 | Austria: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Stoegerer-Hecher 2012 | 10.3109/09513590.2011.588751 | Austria | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Merckx 2011 | 10.3109/13625187.2011.625882 | Belgium | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Benčić 2014 CROATIAN | PMID: 26285466 | Croatia: Zaprešić | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Fait 2011a | 10.2478/s11536-011-0062-9 | Czech Republic | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Kikalova 2014 CZECH | N/A | Czech Republic: Olomouc, Palacky University | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Tiihonen 2008 | 10.2165/1312067-200801030-00004 | Finland | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Amouroux 2018 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0195824 | France | General (male), Providers | Quantitative |

| Jost 2014 FRENCH | 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2014.04.008 | France | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Brucker 2008 | 10.1080/13625180701577122 | Germany | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Oppelt 2017 | 10.1007/s00404-017-4373-1 | Germany | General (female), Providers | Quantitative |

| Schramm 2007 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.03.014 | Germany | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Buhling 2014 | 10.3109/13625187.2014.945164 | Germany | Providers | Quantitative |

| Tsikouras 2014 | 10.1007/s00404-014-3181-0 | Greece | Previously had abortions | Quantitative |

| Sweeney 2015 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0144074 | Ireland: Galway | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Shilo 2015 | 10.1111/jsm.12940 | Israel | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Cagnacci 2018 | 10.1080/13625187.2018.1541080 | Italy | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Crosignani 2009 | 10.1186/1472-6874-9-18 | Italy: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Di Giacomo 2013 | 10.1111/jocn.12432 | Italy | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Franchini 2017 | 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.004 | Italy | Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Gambera 2015 | 10.1186/s12905-015-0226-x | Italy | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sabatini 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.022 | Italy: Bari | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Tafuri 2010 | 10.3109/13625180903427683 | Italy: Apulia | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Vercellini 2010 | 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.071 | Italy: Milan | Other special medical conditions, Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Zeqiri 2009 | PMID: 20380116 | Kosovo: Kosova | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Čepuliene 2012 | PMID: 23128463 | Lithuania | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Crosby 2013 | 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008120 | Multicountry (online): mostly USA; Australia; Canada; New Zealand; United Kingdom; Western Europe | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2017 | 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01180.x | Multicountry: Argentina; Canada; Chile; Finland; France; Hungary; Mexico; Netherlands; Norway; Sweden; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2012 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.002 | Multicountry: Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Korea, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom | Providers | Quantitative |

| Hooper 2010 | 10.2165/11538900-000000000-00000 | Multicountry: Australia; Brazil; France; Germany; Italy; Russia; Spain; United Kingdom; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Apter 2016 | 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.02.036 | Multicountry: Australia; Finland; France; Norway; Sweden; United Kingdom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Schultz-Zehden 2006 | 10.2165/00024677-200605040-00006 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Czech Republic; Denmark; Finland; France; Germany; Hungary; Iceland; Netherlands; Norway; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; United Kingdom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Bitzer 2012 | 10.1080/13625180902968856 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Czech Republic; Israel; Netherlands; Poland; St Petersburg/Moscow in Russia; Slovakia; Sweden; Switzerland; Ukraine | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Bitzer 2013 | 10.3109/13625187.2011.637586 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Czech Republic; Israel; Netherlands; Poland; St Petersburg/Moscow in Russia; Slovakia; Sweden; Switzerland; Ukraine | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Egarter 2013 | 10.1186/1472-6874-13-9 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Czech Republic; Israel; Netherlands; Poland; St Petersburg/Moscow in Russia; Slovakia; Sweden; Switzerland; Ukraine | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Ahrendt 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.004 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Denmark; France; Germany; Italy; Norway; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Urdl 2005 | 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.01.021 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Finland; France; Germany; Hungary; Netherlands; Poland; South Africa; Switzerland | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Nappi 2016 | 10.3109/13625187.2016.1154144 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; France; Italy; Poland; Spain | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Borgatta 2016 | 10.1080/13625187.2016.1212987 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Germany; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Romer 2009 | 10.3109/13625180903203154 | Multicountry: Austria; Bulgaria; Estonia; France; Germany; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Jordan; Latvia; Lebanon; Lithuania; Malta; Netherlands; Poland; Russia; Spain; Ukraine | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Jakimiuk 2011 | 10.3109/09513590.2010.538095 | Multicountry: Belgium; Bulgaria; France; Ireland; Italy; Poland; Romania; Russia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Short 2009 | 10.2165/00044011-200929030-00002 | Multicountry: Belgium; Czech Republic; Estonia; France; Germany; Hungary; Latvia; Lithuania; Malta; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Mansour 2014 | 10.2147/IJWH.S59059 | Multicountry: Brazil; France; Germany; Italy; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Fait 2018 | 10.7573/dic.212510 | Multicountry: Czech Republic; Poland; Romania; Russia; Slovakia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Fait 2011b CZECH | PMID: 21838148 | Multicountry: Czech Republic; Slovakia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Fait 2011c CZECH | PMID: 21649999 | Multicountry: Czech Republic; Slovakia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Heikinheimo 2014 | 10.1093/humrep/deu063 | Multicountry: Finland; France; Ireland; Sweden | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Wiegratz 2010 | 10.3109/13625187.2010.518708 | Multicountry: Germany; Austria | Providers | Quantitative |

| Lopez-del Burgo 2013 | 10.1111/jocn.12180 | Multicountry: Germany; France; Sweden; Romania; United Kingdom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Haimovich 2009 | 10.1080/13625180902741436 | Multicountry: Germany; France; United Kingdom; Spain; Italy; Russian Federation; Estonia; Latvia; Lithuania; Austria; Czech Republic; Denmark; Norway; Sweden | general (female), Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Festin 2016 | 10.1093/humrep/dev341 | Multicountry: Thailand, Brazil, Singapore, Hungary | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Loeber 2017 | 10.1080/13625187.2017.1283399 | Netherlands | Previously had abortions | Mixed methods |

| Roumen 2006 | 10.1080/13625180500389547 | Netherlands | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Banas 2014 | 10.3109/01443615.2013.817982 | Poland | General (female), Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Zgliczynska 2019 | 10.3390/ijerph16152723 | Poland (online) | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Bombas 2012 | 10.3109/13625187.2011.631622 | Portugual: multiple sites | Providers | Quantitative |

| Costa 2011 | 10.3109/13625187.2011.608441 | Portugual: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Larivaara 2010 | 10.1080/09581590903436895 | Russia: St. Petersburg | Providers | Qualitative |

| Lete 2007 | 10.3109/13625187.2016.1174206 | Spain: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Lete 2008 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.11.009 | Spain: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Lete 2016 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.04.014 | Spain | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2011 | 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.11.022 | Sweden: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Kilander 2017 | 10.1080/13625187.2016.1238892 | Sweden | Providers | Qualitative |

| Bitzer 2009 | 10.3109/13625187.2013.819077 | Switzerland: Basel, Bern, Zurich | Providers | Quantitative |

| Merki-Feld 2007 | 10.3109/13625187.2011.630114 | Switzerland | General (female), Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Merki-Feld 2010 | 10.3109/13625187.2010.524717 | Switzerland: Zurich | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Merki-Feld 2012 | 10.3109/13625187.2014.907398 | Switzerland: multiple sites | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Merki-Feld 2014 | 10.1080/13625180701440180 | Switzerland: Zurich | General (female), Young people (female), Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Asker 2006 | 10.1783/147118906776276170 | United Kingdom: England: Birmingham | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Altiparmak 2006 TURKISH | N/A | Turkey: Manisa | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Ciftcioglu 2009 | 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05024.x | Turkey | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Eskicioglu 2017 | 10.12891/ceog3291.2017 | Turkey | Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Kahramanoglu 2017 | 10.5603/GP.a2017.0115 | Turkey: Istanbul | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Kursun 2014 | 10.3109/13625187.2014.890181 | Turkey | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Ortayli 2005 | 10.1016/s0968-8080(05)25175-3 | Turkey | General (male) | Qualitative |

| Ozturk Inal 2017 | 10.4274/jtgga.2016.0180 | Turkey: Meram | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Yanikkerem 2006 | 10.1016/j.midw.2005.04.001 | Turkey: Manisa | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Bracken 2014 | 10.3109/13625187.2014.917623 | United Kingdom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Cheung 2005 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.010 | United Kingdom: England: London | Young people (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Free 2005 | 10.1080/08870440412331337110 | United Kingdom | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Glasier 2008 | 10.1783/147118908786000497 | United Kingdom: Scotland: Edinburgh, Glasgow | General (female), Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Heller 2017 | 10.1111/aogs.13178 | United Kingdom: Scotland: Edinburgh and surrounding area | Other special medical conditions, Pregnant | Quantitative |

| Hoggart 2013 | 10.1016/s0968-8080(13)41688-9 | United Kingdom: England: London | Young people (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Kane 2009 | PMID: 19416603 | United Kingdom: England: Lincolnshire | General (female), Young people (female) | Mixed methods |

| Lakha 2005 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.002 | United Kingdom: Scotland: Edinburgh | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Lowe 2019 | 10.1080/13625187.2019.1675624 | United Kingdom: England: Birmingham, Solihull | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Moses 2010 | 10.3109/13625180903414483 | United Kingdom: England: Leicestershire and Rutland | Vasectomies | Quantitative |

| Newton 2014 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100956 | United Kingdom: England: London | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Okpo 2014 | 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.08.012 | United Kingdom: Scotland | Young people (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Rosales 2012 | 10.3109/01443615.2011.638998 | United Kingdom | General (female), Previously had abortions | Quantitative |

| Say 2009 | 10.1783/147118909787931780 | United Kingdom: England: Newcastle upon Tyne | Young people (female) | Mixed methods |

| Seston 2007 | 10.1007/s11096-006-9068-9 | United Kingdom: England: North West | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Stephenson 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.03.014 | United Kingdom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Umranikar 2008 | ijsw.tiss.edu/greenstone/collect/ijsw/index/assoc/HASH0182/026f5b23.dir/doc.pdf | United Kingdom: England: Southamptom | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Verran 2015 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100764 | United Kingdom: England: West Midlands | General (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Walker 2012 | 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.291 | United Kingdom | General (mixed gender) | qualitative |

| Wellings 2007 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.05.085 | United Kingdom | Providers, General (mixed gender) | quantitative |

| Williamson 2009 | 10.1783/147118909788708174 | United Kingdom: Scotland | Young people (female) | qualitative |

Table 1D.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO Region of the Americas 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alves 2008 Portuguese | 10.1590/s0034-71672008000100002 | Brazil: Sao Paulo | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Fernandes 2006 Portuguese | old.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0104-42302006000500019&script=sci_abstract&tlng=en | Brazil: Sao Paulo: Campinas | Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Ferreira 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.012 | Brazil: Sao Paulo: Campinas | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gurgel Cosme de Nascimento 2017 Portuguese | 10.15446/rsap.v19n1.44544 | Brazil: Caraubas: West Potiguar | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Heilborn 2009 | 10.1590/S0102-311X2009001400009 | Brazil: Rio de Janeiro State | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Hoga 2013 | 10.1016/j.srhc.2013.04.001 | Brazil: Sao Paolo | General (male), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Machado 2013 | 10.3109/09513590.2013.808325 | Brazil | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Marchi 2008 | 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00572.x | Brazil: Sao Paulo: Campinas | Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| Scavuzzi 2016 | 10.1055/s-0036-1580709 | Brazil: Pernambuco | General (female), Nulliparous | Quantitative |

| Telles Dias 2006 | 10.1007/s10461-006-9139-x | Brazil: Belem, Salvador, Sao Jose do Rio Preto, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Itajai | General (mixed gender), Special social conditions, PLHIV | Mixed methods |

| Choi 2010 | 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34571-6 | Canada: British Columbia | Providers | Quantitative |

| Nguyen 2011 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.01.002 | Canada: Ontario: Kingston (online) | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Skakoon-Sparling 2019 | 10.1080/00224499.2019.1579888 | Canada: Ontario | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Toma 2012 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.05.005 | Canada | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Wiebe 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.001 | Canada: Vancouver | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Wiebe 2010 | 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34477-2 | Canada: British Columbia | Nulliparous | Mixed methods |

| Wiebe 2012 | PMID: 23152475 | Canada: British Columbia | Providers | Mixed methods |

| Weisberg 2005b | 10.3109/13625187.2013.853034 | Canada | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gomez Sanchez 2015 Spanish | 10.1007/s10995-017-2297-9 | Colombia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Pomales 2013 | 10.1111/maq.12014 | Costa Rica: San Jose | General (male), Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| van Dijk 2013 | 10.1016/j.jana.2012.10.007 | Dominican Republic: Santiago, Puerto Plata | Special social conditions, General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Cremer 2011 | 10.1089/jwh.2010.2264 | El Salvador: La Paz, San Vicente, Cuscatlan, Cabanas | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Cravioto 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.001 | Mexico | Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Juarez 2011 | 10.1080/17441692.2011.581674 | Mexico: Mexico City: Gustavo A. Madera, Iztapalapa | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Crosby 2013 | 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008120 | Multicountry (online): mostly USA; Australia; Canada; New Zealand; United Kingdom; Western Europe | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Crosby 2008 | 10.1007/s10935-013-0294-3 | Multicountry (online): mostly USA; Canada | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2017 | 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01180.x | Multicountry: Argentina; Canada; Chile; Finland; France; Hungary; Mexico; Netherlands; Norway; Sweden; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2012 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.002 | Multicountry: Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Korea, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom | Providers | Quantitative |

| Hooper 2010 | 10.2165/11538900-000000000-00000 | Multicountry: Australia; Brazil; France; Germany; Italy; Russia; Spain; United Kingdom; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Borgatta 2016 | 10.1080/13625187.2016.1212987 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Germany; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Yam 2007 | 10.1363/ifpp.33.160.07 | Multicountry: Barbados; Jamaica: Kingston metro area | Providers | Quantitative |

| Todd 2011 | 10.1007/s10461-010-9848-z | Multicountry: Brazil: Rio de Janiero; Kenya: Kericho; South Africa: Soweto | PLHIV | Qualitative |

| Mansour 2014 | 10.2147/IJWH.S59059 | Multicountry: Brazil; France; Germany; Italy; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Coffey 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.017 | Multicountry: Mexico: Cuernavaca; South Africa: Durban; Thailand: Khon Kaen | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Mack 2010 | 10.1363/3614910 | Multicountry: Nicaragua: Managua; El Salvador: San Salvador and San Miguel | Special social conditions, Providers | Mixed methods |

| Festin 2016 | 10.1093/humrep/dev341 | Multicountry: Thailand, Brazil, Singapore, Hungary | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Cartwright 2020 | 10.12688/gatesopenres.13045.2 | Multicountry: unspecified | Young people (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Yarris 2016 | 10.1080/17441692.2016.1168468 | Nicaragua: Matagalpa | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Jennings 2011 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.011 | Peru: Lima, Piura | General (female), Providers | Quantitative |

| Ortiz-Gonzalez 2014 | PMID: 25244880 | Puerto Rico: San Juan | Young people (female), Pregnant | Quantitative |

| Agénor 2020 | 10.1363/psrh.12128 | USA: MA: Boston | Young people (male), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Akers 2010 | 10.1089/jwh.2009.1735 | USA: PA: Pittsburgh | Providers | Qualitative |

| Amico 2016 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.012 | USA: NY: NYC: Bronx | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Anderson 2014 | 10.1363/46e1814 | USA: CA: San Francisco | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Arteaga 2016 | 10.1080/00224499.2015.1079296 | USA: CA: San Francisco Bay Area | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Bachorik 2015 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.08.002 | USA: NY: New York City | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Baldwin 2016 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.006 | USA: OR | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Benfield 2018 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.017 | USA: NY | Providers | Quantitative |

| Best 2014 | 10.1363/46E0114 | USA: IN: Indianapolis | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Borrero 2009 | 10.1007/s11606-008-0887-3 | USA: PA: Pittsburgh | General (female), Other special medical conditions | Qualitative |

| Callegari 2017 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.178 | USA | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Campo 2010 | 10.1080/03630242.2010.480909 | USA: (unspecified) rural midwestern state | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Carr 2018 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.008 | USA: NM | Pregnant, Postpartum, Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Chapa 2012 | 10.2147/PPA.S30247 | USA: TX: Dallas | General (female), Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Coleman-Minahan 2019 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.08.011 | USA: TX | General (female), Special social conditions, Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Corbett 2006 | 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00114.x | USA: (unspecified) southern coastal city | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Creinin 2008 | 10.1097/01.AOG.0000298338.58511.d1 | USA: multiple sites (Boston, New York, Norfolk, Baltimore, Portland, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Madison) | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Dehlendorf 2010 | 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.021 | USA: CA: San Francisco | Previously had abortions | Quantitative |

| Dehlendorf 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.012 | USA: CA: San Francisco | General (female) | Qualitative |

| DeMaria 2019 | 10.1186/s12905-019-0827-x | USA: (unspecified) southeastern coastal region | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| DeSisto 2018 | 10.1186/s40834-018-0073-x | USA: GA | Postpartum, Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Diedrich 2015 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.025 | USA: MO: St. Louis | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Donnelly 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.012 | USA: ME, NH, VT | General (female), Providers | Quantitative |

| Downey 2017 | 10.1016/j.whi.2017.03.004 | USA: CA: San Francisco Bay Area | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Edelman 2007 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.02.005 | USA: OR: Portland; GA: Atlanta | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Epstein 2008 | 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.007 | USA: CA: San Francisco | Young people (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Espey 2014 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.018 | USA: NM: Albuquerque | Nulliparous | Quantitative |

| Fan 2016 | 10.1007/s10508-016-0816-1 | USA: PA: Pittsburgh | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Fennell 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.012 | USA: CT, MA, NC, NJ, RI, VA | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Fleming 2010 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020 | USA: CA | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Foster 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.025 | USA: multiple sites (St. Louis, New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Salt Lake City) | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Friedman 2015 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.02.015 | USA: NY: New York City | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Frost 2008 | 10.1363/4009408 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Galloway 2017 | 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.006 | USA: SC: Spartanburg, Horry | Young people (mixed gender), Nulliparous | Qualitative |

| Garbers 2013 | 10.1089/jwh.2013.4247 | USA: NY: New York City | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gilliam 2009 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.05.008 | USA: IL: Chicago | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Gollub 2015 | 10.1080/13691058.2015.1005672 | USA | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Gomez 2014 | 10.1363/46e2014 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gomez 2015 | 10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.011 | USA | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Gomez 2017 | 10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.011 | USA | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Goyal 2017 | 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001926 | USA: TX | Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Gubrium 2011 | 10.1007/s13178-011-0055-0 | USA: MA: 3 cities in western region | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Hall 2016a | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.007 | USA | General (female), Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Hall 2016b | 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101046 | USA: NY: Ithaca | General (female), Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| He 2016 | 10.1089/jwh.2016.5807 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Hensel 2012 | 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02700.x | USA | General (male) | Quantitative |

| Higgins 2008 | 10.1363/psrh.12025 | USA: GA: Atlanta | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Higgins 2015 | 10.1111/jsm.12375 | USA | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Higgins 2017 | 10.1363/47e4515 | USA: WI: Dane County | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Hodgson 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.011 | USA: CT: New Haven | General (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Holt 2006 | 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.281 | USA: CA: Northern region | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Hoopes 2015 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.011 | USA: WA | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Hoopes 2018 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.11.008 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.11.008. Epub 2017 Dec 1. | USA: CO | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Howard 2013 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.07.013 | USA: MO: Kansas City | Postpartum, Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Hubacher 2015b | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.11.006 | USA: NC | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Hubacher 2017 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.033 | USA: NC | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Jackson 2016 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.010 | USA | General (female), Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Kaller 2020 | 10.1186/s12905-020-0886-z | USA: CA: San Francisco | Women seeking emergency contraception, Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Kavanaugh 2013 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.10.006 | USA | Young people (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Kimport 2017 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.009 | USA: CA: San Francisco Bay Area | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Lamvu 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.007 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Latka 2008 | 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.2.160 | USA: NY: New York City | Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Lehan Mackin 2015 | 10.1177/0193945914551005 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Lessard 2012 | 10.1363/4419412 | USA: multiple sites (St. Louis, Chicago, Little Rock, Seattle, Philadelphia, Oakland) | Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Levy 2014 | 10.1016/j.whi.2014.10.001 | USA: CA: 6 San Francisco Bay Area clinics | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Lewis 2012 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.08.003 | USA: IL: Chicago | postpartum, Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Madden 2010 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002 | USA: IL | Providers | Quantitative |

| Madden 2015 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.051 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Mantell 2011 | 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.65 | USA: NY: New York City | Providers | Qualitative |

| Marshall 2016 | 10.1363/48e10116 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Marshall 2017 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.004 | USA: CA: Oakland | General (female) | Qualitative |

| McLean 2017 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.08.010 | USA: CA: San Francisco Bay Area | General (female), Providers | Mixed methods |

| McNicholas 2012 | 10.1016/j.whi.2012.04.008 | USA: (unspecified) urban site | Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Melo 2015 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.08.001 | USA: CO | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Melton 2012 | 10.1363/4402212 | USA: UT: Salt Lake City | Women seeking emergency contraception | Quantitative |

| Merkatz 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.05.015 | USA: MO: St. Louis | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Michaels 2018 | N/A | USA: IA | Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Miller 2011 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.06.005 | USA: PA | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Minnis 2014 | 10.1363/46e1414 | USA: CA: San Francisco | Young people (female) | Mixed methods |

| Modesto 2014 | 10.1093/humrep/deu089 | USA: CA: San Francisco | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Munsell 2009 | print.ispub.com/api/0/ispub-article/9991 | USA: TX: Galveston | Providers | Quantitative |

| Nelson 2017 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.010 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Nettleman 2007 | 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.10.019 | USA | General (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Nguyen 2017 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.002 | USA | Providers | Quantitative |

| Paul 2020 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1266 | USA: (unspecified) mid-west region | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Payne 2016 | 10.1111/jmwh.12425 | USA: (unspecified) southeastern | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Peipert 2011 | 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad | USA: MO: St. Louis | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Philliber 2014 | 10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.001 | USA: CO, IA | Providers | Quantitative |

| Potter 2014a | 10.1097/aog.0000000000002136 | USA: NY: school- based health centers (SBHCs) and community health center | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Potter 2014b | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039 | USA: TX: El Paso, Austin | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Potter 2017 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.011 | USA: TX: Odessa, Austin, Edinburg, Dallas, Houston, El Paso | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Powell-Dunford 2011 | 10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.006 | USA | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Raifman 2018 | 10.1016/j.whi.2017.07.006 | USA: MI, MO, NJ, UT | general (female) | Quantitative |

| Rey 2020 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.01.010 | USA: VT | General (female), PWID | Quantitative |

| Rocca 2007 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.024 | USA: CA: San Francisco Bay Area | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Roe 2016 | 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.012 | USA: PA (online) | Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Rubin 2010 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.001 | USA: NY: NYC: Bronx | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Rubin 2015 | 10.1089/jwh.2009.1549 | USA: NY: NYC: Bronx | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Sanders 2014 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0199724 | USA | Young people (male) | Quantitative |

| Sanders 2018 | 10.1007/s10461-013-0422-3 | USA: UT: Salt Lake City | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sangi-Haghpeykar 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.010 | USA: TX: Houston | General (female), Previously had abortions | Quantitative |

| Sangraula 2017 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.11.004 | USA: NY: NYC: Uptown Manhattan, Lower Bronx | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Sastre 2015 | 10.1080/13691058.2014.989266 | USA: FL: Miami-Dade County | General (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Shih 2013 | 10.1177/1557988312465888 | USA: CA: San Francisco | General (mixed gender), Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| Sittig 2020 | 10.1016/j.whi.2019.11.003 | USA: PA (online) | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Spies 2010 | 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.005 | USA | Young people (female), General (female) | Qualitative |

| Stanek 2009 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.003 | USA: OR | Women seeking abortion services | Quantitative |

| Stanwood 2009 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.020 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Stein 2020 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.01.004 | USA: NY: NYC: Bronx | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Stewart 2007 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.06.001 | USA: CA: San Francisco | Young people (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Straten 2016 | 10.1007/s10461-016-1299-8 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sulak 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.07.001 | USA | Providers | Quantitative |

| Sundstrom 2015 | 10.1080/10410236.2016.1172294 | USA: SC: Charleston | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Sundstrom 2016 | 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018650 | USA | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Tanner 2008 | 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.017 | USA: IN: Indianapolis | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Teal 2012 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.001 | USA: CO | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Terrell 2011 | 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.02.003 | USA: IN: Indianapolis | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Thorburn 2006 | 10.1300/J013v44n01_02 | USA: CA | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Tung 2012 | 10.1080/07448481.2012.663839 | USA | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Turok 2016 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.01.009 | USA: UT: Salt Lake City | Women seeking emergency contraception | Quantitative |

| Tyler 2012 | 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39 | USA: multiple sites | Providers | Quantitative |

| Venkat 2008 | 10.1007/s10900-008-9100-1 | USA: NY: NYC | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| von Sadovszky 2008 | 10.1016/j.whi.2008.01.004 | USA | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Walker 2019 | 10.1080/03630242.2012.728190 | USA: CA: Northern region | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Werth 2015 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.003 | USA: MO: St. Louis | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Weston 2012 | 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.094 | USA: IL: Chicago | Young people (female), Postpartum | Qualitative |

| Whitaker 2008 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.04.119 | USA: PA: Pittsburgh | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| White 2013 | 10.1016/j.whi.2013.05.001 | USA: TX: El Paso | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Whittaker 2010 | 10.1363/4210210 | USA: PA: Philadelphia | Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Woo 2015 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.09.007 | USA: MD: Baltimore | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Xu 2011 | 10.2147/ijwh.s57470 | USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Yee 2010 | 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.014 | USA: IL: Chicago | Young people (female), Postpartum | mixed methods |

Table 1E.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO South-East Asia Region 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zafar 2006 | 10.1111/j.1447-0578.2006.00132.x | Bangladesh: Tangail District: Kalihati sub-district | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Ahuja 2019 | 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_676_19 | India : Patiala, Punjab Province | Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Das 2015 | 10.1071/SH15045 | India: Delhi | General (female), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Hall 2008 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101046 | India: Maharashtra | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Jain 2016 | 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16545.7516 | India: New Delhi | Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Khokhar 2005 | moam.info/determinants-of-acceptance-of-no-scalpel-vasectomy-medind_59d916e41723dd4e6be7785f.html | India: New Delhi | Vasectomies | Quantitative |

| Meenakshi 2020 | 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1012_19 | India: Jodhpur, Rajasthan | Providers | Quantitative |

| Neeti 2010 | nihfw.org/Publications/pdf/HPPI_33(1),2010.pdf | India: Delhi: Central district | general (female) | Qualitative |

| Patra 2015 | 10.1108/ijhrh-06-2014-0010 | India | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Rizwan 2014 | 10.7860/jcdr/2014/8278.4714 | India: northern | General (male), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Sharma 2018 | pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/sea-185340 | India: east Delhi | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sherpa 2013 | PMID: 24971113 | India: Karnataka: Udupi District: Moodu Alevoor village | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sood 2015 | ijmch.org/home/indian-journal-of-maternal-and-child-health-volume-17-april—december-2015 | India: Punjab, Amritsar | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Thulaseedharan 2018 | 10.2147/oajc.s152178 | India: Trivandrum district, Kerala | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Valsangkar 2012 | 10.4103/0970-1591.102704 | India: Karimnagar district, Andhra Pradesh | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Spagnoletti 2019 | 10.1080/17441730.2019.1578532 | Indonesia: Yogyakarta | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Titaley 2017 | 10.1016/j.midw.2017.07.014 | Indonesia: East Java, Nusa Tenggara Barat Provinces | Providers | Qualitative |

| Brunie 2019 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0216797 | Multicountry: India: New Dehli; Nigeria: Ibadan | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Cartwright 2020 | 10.12688/gatesopenres.13045.2 | Multicountry: unspecified | Young people (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Coffey 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.017 | Multicountry: Mexico: Cuernavaca; South Africa: Durban; Thailand: Khon Kaen | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Cover 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.007 | Multicountry: India: Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh; Uganda: Kampala | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Festin 2016 | 10.1093/humrep/dev341 | Multicountry: Thailand, Brazil, Singapore, Hungary | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Hooper 2010 | 10.2165/11538900-000000000-00000 | Multicountry: Australia; Brazil; France; Germany; Italy; Russia; Spain; United Kingdom; USA | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Machiyama 2018 | 10.1186/s12978-018-0514-7 | Multicountry: Kenya: Nairobi, Homa Bay; Bangladesh: Matlab | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Xu 2014 | 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.019 | Multicountry: China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Korea, Thailand | Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Sapkota 2016 | 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00122 | Nepal: Kapibastu | General (female), General (male) | Mixed methods |

| Shrestha 2014 | 10.3126/kumj.v12i3.13718 | Nepal: Kathmandu: Dhulikhel | General (mixed gender), Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Santibenchakul 2016 | 10.5372/1905-7415.1003.485 | Thailand: Bangkok | General (female) | Quantitative |

Table 1A.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO African Region 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaan 2014 | 10.2989/16085906.2014.952654 | Botswana | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Ajong 2018 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0202967 | Cameroon: Biyem-Assi | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Thomson 2012 | 10.1186/1471-2458-12-959 | Democratic Republic of the Congo: Idjwi Island | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Alene 2018 | 10.1186/s12905-018-0608-y | Ethiopia: Amhara | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Asfaw 2014 | 10.1186/1471-2458-14-566 | Ethiopia: Addis Ababa | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Belda 2017 | 10.1186/s12913-017-2115-5 | Ethiopia: Oromia Regional State, Bale Eco-Region | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Both 2015 | 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.06.005 | Ethiopia: Addis Ababa | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Davidson 2016 | 10.1007/s10995-016-2018-9 | Ethiopia | General (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Endriyas 2018 | 10.1186/s12884-018-1731-3 | Ethiopia: Southern Nations, Nationalities and People's Region | General (female), Providers | Mixed methods |

| Gebremariam 2014 | 10.1155/2014/878639 | Ethiopia: Tigray: Adigrat Town, Tigray | General (mixed gender), Providers | Qualitative |

| Keith 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.010 | Ethiopia: Oromia Region (rural and peri-urban) | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Tsehaye 2011 | 10.1155/2013/317609 | Ethiopia: Tigray Region: Shire Indaselassie Town | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Weldegerima 2008 | 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.10.001 | Ethiopia: Fogera District: Woreta | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Adu 2018 | 10.4314/gmj.v52i4.3 | Ghana: Central Region | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Agyei-Baffour 2015 | 10.1186/s12978-015-0022-y | Ghana: Kumasi | General (male) | Mixed methods |

| Krakowiak-Redd 2011 | PMID: 22574499 | Ghana: Kumasi | General (female) | Quantitative |

| L'Engle 2011 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2011-0077 | Ghana: Accra | Women seeking emergency contraception | Qualitative |

| Opare-Addo 2011 | PMID: 21987939 | Ghana: Kumasi | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Osei 2014 | 10.1363/4013514 | Ghana: Accra | General (mixed gender), Previously had abortions | Qualitative |

| Rominski 2017 | 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00281 | Ghana: Kumasi, Accra | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Staveteig 2017 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0182076 | Ghana: greater Accra | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Teye 2013 | PMID: 24069752 | Ghana: Asuogyaman District | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| van der Geugten 2017 | 10.1007/s12119-017-9432-z | Ghana: Bolgatanga municipality | Young people (mixed gender), General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Hubacher 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.03.001 | Kenya: Nairobi | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Hubacher 2015a | 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.01.009 | Kenya: Nairobi | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Keesara 2017 | 10.1080/13691058.2017.1340669 | Kenya: Nairobi | Postpartum | Qualitative |

| Mayhew 2017 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4514-2 | Kenya | PLHIV | Mixed methods |

| Ndegwa 2014 | PMID: 26859013 | Kenya: Embu | Pregnant | Quantitative |

| Newmann 2013 | 10.1155/2013/915923 | Kenya: Nyanza Province: Migori, Rongo, Siba districts: government-run HIV care and treatment clinics and patient support centers | Providers, PLHIV | Mixed methods |

| Odwe 2020 | 10.1016/j.conx.2020.100030 | Kenya: Homa Bay County | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Patel 2014 | 10.1089/apc.2014.0046 | Kenya: Nyanza Province: Kisumu East, Nyatike, Rongo, and Suba districts | PLHIV, General (male) | Qualitative |

| Roxby 2016 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101233 | Kenya: Nairobi | General (mixed gender), PLHIV, Pregnant | Qualitative |

| Ruminjo 2005 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.04.001 | Kenya: Nairobi, Riruta, Thika | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Shabiby 2015 | 10.1186/s12905-015-0222-1 | Kenya: Naivasha (rural), Mbagathi (urban) districts | PLHIV, Postpartum, General (female) | Quantitative |

| Shapley-Quinn 2019 | 10.2147/IJWH.S185712 | Kenya: Kisuma; South Africa: Soshanguve | General (female) | Qualitative |

| RamaRao 2018 | 10.1111/sifp.12046 | Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal | Postpartum | Mixed methods |

| Chipeta 2010 | 10.4314/mmj.v22i2.58790 | Malawi: Mangochi district: Lungwena, Makanjira | General (mixed gender), Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Haddad 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.08.006 | Malawi: Lilongwe | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Haddad 2014 | 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.026 | Malawi: Lilongwe | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| O'Shea 2015 | 10.1080/09540121.2014.972323 | Malawi: Lilongwe | General (female), PLHIV, Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Brunie 2019 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0216797 | Multicountry: India: New Dehli; Nigeria: Ibadan | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Burke 2014a | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.009 | Multicountry: Senegal: Mbour, Thies, and Tivaouane; Uganda: Mubende, Nakasongola | Providers | Qualitative |

| Burke 2014b | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.022 | Multicountry: Senegal; Uganda | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Callahan 2019 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0217333 | Multicountry: Burkina Faso; Uganda | General (female), General (male), Providers | Mixed methods |

| Cartwright 2020 | 10.12688/gatesopenres.13045.2 | Multicountry: unspecified | Young people (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Chin-Quee 2014 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100687 | Multicountry: Kenya: Nairobi; Nigeria: Lagos | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Coffey 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.017 | Multicountry: Mexico: Cuernavaca; South Africa: Durban; Thailand: Khon Kaen | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Cover 2013 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.007 | Multicountry: India: Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh; Uganda: Kampala | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Lendvay 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.002 | Multicountry: Kenya: Nairobi; Pakistan: Sindh, Punjab | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Machiyama 2018 | 10.1186/s12978-018-0514-7 | Multicountry: Kenya: Nairobi, Homa Bay; Bangladesh: Matlab | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Montgomery 2010a | 10.1007/s10461-009-9609-z | Multicountry: South Africa: Durban, Soweto; Zimbabwe: near Harare | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Nel 2016 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0147743 | Multicountry: Kenya; Malawi; South Africa; Tanzania | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Todd 2011 | 10.1007/s10461-010-9848-z | Multicountry: Brazil: Rio de Janiero; Kenya: Kericho; South Africa: Soweto | PLHIV | Qualitative |

| Tolley 2014 | 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00147 | Multicountry: Kenya (peri-urban and urban sites); Rwanda (rural, peri-urban, and urban sites) | General (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Urdl 2005 | 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.01.021 | Multicountry: Austria; Belgium; Finland; France; Germany; Hungary; Netherlands; Poland; South Africa; Switzerland | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Woodsong 2014 | 10.1111/1471-0528.12875 | Multicountry: Malawi: Lilongwe; Zimbabwe: Harare | General (mixed gender), Providers | Qualitative |

| Mayaki 2014 | 10.1080/02646838.2014.888545 | Niger | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Aisien 2010 | PMID: 20857796 | Nigeria: Edo State: Benin-City | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Egede 2015 | 10.2147/PPA.S72952 | Nigeria: Ebonyi State: Abakaliki | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Ezugwu 2019 | 10.1002/ijgo.13027 | Nigeria: Enugu | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Iyoke 2014 | 10.2147/PPA.S67585 | Nigeria: Enugu | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Lanre-Babalola 2015 | proquest.com/scholarly-journals/dynamics-knowledge-use-preference-birth-control/docview/1709681040/se-2?accountid=11752 | Nigeria: Ibadan | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Okunlola 2006 | 10.1080/01443610600613516 | Nigeria: Ibadan | General (female), Young people (female) | Quantitative |

| Olajide 2014 | PMID: 25022145 | Nigeria: Osun State; primary and secondary schools | Young people (mixed gender), Other special medical conditions | Quantitative |

| Orji 2005 | 10.1080/13625180500331259 | Nigeria: Southwest | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Sodje 2016 | 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.05.005 | Nigeria: Edo, Delta, Anambra, Ebonyi, Abia states | Postpartum | Quantitative |

| Sunmola 2005 | 10.1080/09540120412331319732 | Nigeria: Ibadan | Young people (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Ujuju 2011 | 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00900.x | Nigeria: Katsina state: Rimi, Katsina, Kaita; Enugu state: Nkanu West, Enugu East, Igbo-Etiti | Providers, General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Kestelyn 2018 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0199096 | Rwanda: Kigali | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Shattuck 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.003 | Rwanda | General (mixed gender), Vasectomies | Quantitative |

| Leye 2015 FRENCH | PMID: 26164961 | Senegal: Diourbel region: Mbacke district | General (female) | Mixed methods |

| Crede 2012 | 10.1186/1471-2458-12-197 | South Africa: Cape Town: Khaylitsha and Mitchell's Plain | Postpartum, PLHIV | Quantitative |

| de Bruin 2017 | 10.1080/09540121.2017.1327647 | South Africa | Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Harries 2019 | 10.1186/s12978-019-0830-6 | South Africa: Western Cape | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Joanis 2011 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.002 | South Africa: Durban | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Laher 2009 | 10.1007/s10461-009-9544-z | South Africa: Soweto | PLHIV | Qualitative |

| Mahlalela 2016 | 10.11564/30-2-873 | South Africa: Durban | general (female) | Qualitative |

| Morroni 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.005 | South Africa: Western Cape Province | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Ndinda 2017 | 10.3390/ijerph14040353 | South Africa: Kwa-Zulu-natal (rural) | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Schwartz 2016 | 10.1177/0956462415604091 | South Africa: Johannesburg | General (mixed gender), PLHIV | Qualitative |

| Smit 2006 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.019 | South Africa: KwaZulu-Natal: Durban | General (female), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Mathenjwa 2012 | 10.3109/13625187.2012.694147 | Swaziland: Lavusima | special social conditions | Qualitative |

| Ziyane 2006 | 10.4102/hsag.v11i1.213 | Swaziland | Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Bunce 2007 | 10.1363/3301307 | Tanzania: Kigoma Region | Vasectomies, General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Cooper 2019 | 10.1111/mcn.12735 | Tanzania: Mara, Kagera | General (mixed gender), Postpartum, Providers | Qualitative |

| Rusibamayila 2016 | 10.1080/13691058.2016.1187768 | Tanzania: Kilombero District | General (mixed gender), Providers | Qualitative |

| Sato 2020 | 10.1080/26410397.2020.1723321 | Tanzania: Arusha Region | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Sheff 2019 | 10.1186/s12978-019-0836-0 | Tanzania: Kilombero, Rufiji, and Ulanga | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Akol 2014 | 10.9745/ghsp-d-14-00085 | Uganda: multiple sites | Providers, General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Byamugisha 2010 | 10.3109/00016341003611220 | Uganda: Kampala | Women seeking emergency contraception | Quantitative |

| Cover 2017 | 10.1363/3919513 | Uganda: Gulu district, Mubende | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Higgins 2014 | 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790 | Uganda: Rakai District | Young people (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Kabagenyi 2016 | 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.78.6613 | Uganda: Mpigi, Bugiri (rural) | General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Kakaire 2016 | 10.3109/13625187.2016.1146249 | Uganda: Kampala | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Lester 2015 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.002. Epub 2014 Dec 12.; ID: 106 | Uganda: Kampala | Pregnant | Quantitative |

| Mbonye 2012 | 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009357 | Uganda: Central region (rural, semi-urban, and urban) | PLHIV, General (mixed gender) | Mixed methods |

| Nattabi 2011 | 10.1186/1752-1505-5-18 | Uganda: Gulu health facilities | Special social conditions, PLHIV | Mixed methods |

| Paul 2016 | 10.3402/gha.v9.30283 | Uganda: Central region (rural, semi-urban, and urban) | Providers | Qualitative |

| Polis 2014 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.008 | Uganda: Rakai | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Wanyenze 2013 | 10.1186/1471-2458-13-98 | Uganda: Kampala | PLHIV | Qualitative |

| Montgomery 2010b | 10.1186/1758-2652-13-30 | Zimbabwe: Epworth | General (female) | Quantitative |

| van der Straten 2010 | 10.1783/147118910790290966 | Zimbabwe: Harare | Young people (female) | Mixed methods |

| van der Straten 2012 | 10.1007/s10461-012-0256-4 | Zimbabwe: Harare: peri-urban township | General (female) | Mixed methods |

Table 1F.

Summary characteristics of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review which were conducted in countries in the WHO Western Pacific Region 2005-2020

| Author year | DOI | Location | Population | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateson 2016 | 10.1111/ajo.12534 | Australia: New South Wales: Queensland | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Dixon 2014 | 10.3109/13625187.2014.919380 | Australia | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Garrett 2015 | 10.1186/s12905-015-0227-9 | Australia | Young people (female), Providers | Qualitative |

| Inoue 2017 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101132 | Australia: New South Wales | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Kelly 2016 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101356 | Australia: New South Wales: Sydney | Providers | Qualitative |

| Knox 2012 | 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.025 | Australia | General (female), Providers | Quantitative |

| Knox 2013 | 10.2165/11598040-000000000-00000 | Australia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Larkins 2007 | 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01025.x | Australia: New South Wales: Queensland | Young people (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Mills 2006 | 10.1080/07399330600629468 | Australia | General (female) | Qualitative |

| Olsen 2014 | 10.1186/1472-6874-14-5 | Australia | PWID | Qualitative |

| Ong 2013 | 10.1363/4507413 | Australia: Victoria | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Philipson 2011 | 10.1089/jwh.2010.2455 | Australia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Russo 2020 | 10.1080/13691058.2019.1643498 | Australia: Victoria: Melbourne | Special social conditions, General (mixed gender) | Qualitative |

| Watts 2014 | 10.1093/jrs/feu040 | Australia: Victoria: Melbourne | Providers, Young people (female), Pregnant | Qualitative |

| Weisberg 2005a | 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30462-5 | Australia: New South Wales: Queensland; South Australia | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Weisberg 2013 | 10.3109/13625187.2013.777830 | Australia | General (female), providers | Quantitative |

| Weisberg 2014 | PMID: 16113711 | Australia: New South Wales | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Wigginton 2016 | 10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101184 | Australia | Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Wong 2009 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.021 | Australia: Victoria | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Thyda 2015 | 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000635 | Cambodia: Chhouk Sar | PLHIV | Quantitative |

| Hou 2010 | 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.09.020 | China: Guandong Province: Enping City | Special social conditions | Quantitative |

| Nian 2010 | PMID: 21073077 | China: Sichuan Province | Providers, General (mixed gender), Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| Cartwright 2020 | 10.12688/gatesopenres.13045.2 | Multicountry: unspecified | Young people (mixed gender), Special social conditions | Mixed methods |

| Crosby 2013 | 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008120 | Multicountry (online): mostly USA; Australia; Canada; New Zealand; United Kingdom; Western Europe | General (mixed gender) | Quantitative |

| Festin 2016 | 10.1093/humrep/dev341 | Multicountry: Thailand, Brazil, Singapore, Hungary | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Gemzell-Danielsson 2012 | 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.002 | Multicountry: Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Korea, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom | Providers | Quantitative |

| Xu 2014 | 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.019 | Multicountry: China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Korea, Thailand | Menstrual Issues | Quantitative |

| Roke 2016 | 10.1071/HC15040 | New Zealand | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Rose 2011 | 10.1089/jwh.2010.2658 | New Zealand: Wellington | Women seeking abortion services, Young people (female) | Qualitative |

| Terry 2011 | 10.1177/0959353511419814 | New Zealand | Vasectomies | Qualitative |

| Gupta 2017 | 10.1111/ajo.12596 | Papua New Guinea: Madang Island, Milne Bay (mainland) | General (female) | Quantitative |

| Lee 2019 | 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.3.173 | South Korea | Providers | Quantitative |

| Park 2011 | 10.2147/IJWH.S26620 | Vietnam: Thai Nguyen, Khanh Hoa, Vinh Long provinces | General (female) | Quantitative |

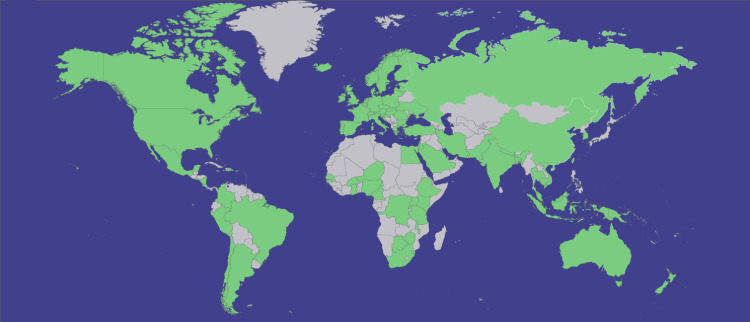

Studies were conducted in 93 countries (Fig. 2). Fifty-one articles reported data from multiple countries, mostly in Europe; 10 articles were from the 11-country European CHOICE study. All 6 WHO regions1 were represented: the African Region (AFRO) (n = 103), the Region of the Americas (PAHO) (n = 172), the South-East Asia Region (SEARO) (n = 27), the European Region (EURO) (n = 99), the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) (n = 14), and the Western Pacific Region (WPRO) (n = 34). A plurality of articles reported studies that took place in the USA (n = 139), followed by the United Kingdom (n = 29) and Australia (n = 23). Most articles reported studies that were primarily conducted in high-income countries (n = 250), but studies were also conducted in upper-middle (n = 67), lower-middle (n = 78), and low- (n = 44) income countries as classified by the World Bank. (Note: numbers do not add to 423 because of studies taking place in multiple countries.)

Fig. 2.

Countries where studies presenting primary data on contraceptive values and preferences were conducted. Sources were published between January 2005 and July 2020. Green indicates data available; gray, data not identified.

While most articles presented quantitative findings (269/423, 63%), 121 (29%) used qualitative methods, and 34 (8%) used mixed- or multimethods. A range of study designs and methods were used: the most common quantitative design was cross-sectional surveys (n = 190), followed by qualitative in-depth interviews (n = 116) and focus group discussions (n = 69); however, prospective cohort studies, randomized trials, and other observational designs were also represented. The mixed/multimethods studies generally involved a cross-sectional quantitative survey with additional qualitative analysis of open-ended survey responses or additional data collection from focus group discussions or in-depth interviews.

3.3. Risk of bias varied by study design.

We generally found that studies involving qualitative analyses presented the 9 rigor domains assessed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist. Cross-sectional studies generally did not include comparison groups (22%); of those which did, only a few compared across sociodemographic characteristics (16%) or outcomes (5%). Studies employing quantitative analyses sometimes followed participants over time (36%), used a control or comparison group (39%), or compared outcomes pre- and postexposure to a contraceptive method (19%). Quantitative studies rarely randomly selected participants for assessment (15%) or randomly allocated participants to the intervention or control arm (if applicable) (14%). Of quantitative studies that followed participants over time (n = 90), 55 (61%) had a follow-up rate of 80% or more. Of quantitative studies including a control or comparison group (n = 106), 35 (33%) compared groups across sociodemographic characteristics and 6 (5%) compared groups on outcome measures at baseline.

The articles explored the values and preferences of contraceptive users in the general female population (n = 220), general male population (n = 10), general population (not disaggregating between male and female participants) (n = 44), women with specific reproductive health experiences (n = 52), adolescents and young adults (n = 76), people living with HIV (n = 22), sex workers (n = 6), transmasculine individuals (n = 1), people who inject drugs (n = 2), and those living in humanitarian contexts (n = 4), as well as perspectives of health workers (n = 53) (Table 2). (Note: numbers do not add to 423 because some articles included perspectives from multiple population groups.) Separate systematic reviews examining the values and preferences of women with specific reproductive health experiences (i.e., pregnant, postpartum, seeking emergency contraception, or seeking abortion) [9], adolescents and young adults [7], people living with HIV [10], other end-users in specific circumstances (i.e., sex workers, transmasculine individuals, people who inject drugs, and those living in humanitarian contexts) [8], and health workers [11] are published in this same journal issue.

Table 2.

Number of articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review that provide data on different populations 2005-2020

| Population category | Number of articlesa (% out of 423 total included articles) |

|---|---|

| General population | |

| Female contraceptive users | 220 (52%) |

| Male contraceptive users | 10 (2.4%) |

| Both male and female (not disaggregated by gender) | 44 (10.4%) |

| Women with specific reproductive health experiences | |

| Women who are nulliparous | 4 (0.9%) |

| Women who are pregnant | 7 (1.7%) |

| Postpartum women | 23 (5.4%) |

| Women seeking abortion services | 7 (1.7%) |

| Women seeking emergency contraception | 5 (1.2%) |

| Women who previously had abortion(s) | 6 (1.4%) |

| Adolescents and young adults | |

| Female young people | 55 (13%) |

| Male young people | 2 (0.5%) |

| Both male and female (not disaggregated by gender) | 19 (4.5%) |

| People in specific social conditions or humanitarian settings | |

| People living with HIV | 22 (5.2%) |

| Sex workers | 6 (1.4%) |

| Transmasculine individuals | 1 (0.2%) |

| People who inject drugs | 2 (0.5%) |

| Those living in humanitarian contexts | 4 (0.9%) |

| Health workers | 53 (12.5%) |

Studies that reported any findings on contraceptive values and preferences for this specific population group. Note that studies often reported data for multiple population groups, so percentages do not add up to 100.

Included articles mentioned end-users' and health workers’ values and preferences related to all of the methods covered by WHO's guidelines, including male condoms (n = 161), female condoms (n = 41), oral contraceptive pills, i.e., combined oral contraceptive pills (n = 204) and progestogen-only pills (POP) (n = 105), intrauterine devices (IUD) or hormone-releasing intrauterine systems (IUS) (n = 221), implants (n = 139), injectable contraceptives (n = 140), diaphragm (n = 37), vaginal ring (n = 82), transdermal patch (n = 74), male sterilization or vasectomy (n = 39), female sterilization or tubal ligation (n = 72), fertility awareness-based methods (e.g., rhythm method, calendar method) (n = 64), emergency contraception (n = 42), withdrawal (n = 67), and other contraceptive methods, including abstinence, lactational amenorrhea method, and other (often unspecified) traditional methods (n = 42).

3.4. Commonly reported values among contraceptive users

Contraceptive users across geographic regions and population subgroups consistently prioritized several thematic issues (Table 3). Overall, people wanted choice: they desired a range of options from which to choose, especially since different people preferred different methods at different times for different reasons.

Table 3.

Common themes related to values and preferences, listed in order of frequency, described by articles included in the contraceptive values and preferences global systematic review 2005-2020

| Values and preferences themes | Number of articles (% out of 423 total included articles) |

|---|---|

| Side effects and safety | 246 (58.2%) |

| Method effectiveness/reliability | 191 (45.2%) |

| Ease, duration, or frequency of use | 179 (42.3%) |

| Noninterference in sex and partner relations | 141 (33.3%) |

| Effects on menstruation | 83 (19.6%) |

| Cost/affordability | 71 (16.8%) |

| Control and autonomy | 67 (15.8%) |

| Private, discreet, or covert use | 50 (11.8%) |

Side effects and safety was the most commonly reported issue (mentioned in 246 articles) when considering contraceptive methods. Contraceptive users and health workers were concerned about pain. They desired minimal side effects or adverse events (relating to changes in libido, bleeding, menstrual cycles, acne, weight gain, etc.); if these were unavoidable, they wanted to be able to anticipate, manage, and tolerate side effects. Women often asked how commonly used contraceptive methods were, and how safe or healthy they were.

Method effectiveness and reliability were the next most commonly reported (mentioned in 191 articles), especially for preventing pregnancy (e.g., “security in not getting pregnant” [36], “having had a false alarm [about pregnancy] in the past” [37]), but also for providing dual protection against HIV and other STIs [38]. Women in some studies expressed interest in contraceptive methods that were effective, despite experiencing uncomfortable side effects like vomiting or diarrhea. Participants expressed varying acceptability levels for percent efficacy—or conversely, varying tolerance levels for likelihood of contraceptive failure.

Ease and duration/frequency of use (mentioned in 179 articles) was also very important. Many people desired contraceptive methods that were comfortable or convenient to use. Conversely, others expressed fears of the contraceptive method “falling off” [39] or forgetting to use or administer it. One hundred forty-four articles mentioned accessibility as a factor in their contraceptive preference, considering logistical issues in getting advice on, obtaining, maintaining, or changing contraceptive methods. Reversibility was very important to current and hypothetical contraceptive users (mentioned in 73 articles), both in terms of duration of contraceptive effectiveness and frequency of use (whether taken once a day, administered weekly or monthly or longer, or a permanent contraceptive method) and how difficult it was to start, switch, or stop the contraceptive method (e.g., stop taking a daily oral contraceptive pill versus getting an IUD removed). Women preferred choosing a method that “they are in control of stopping” [40]. For many women, it was important that they be able to resume fertility immediately after discontinuation or at least that using a contraceptive method for a period of time would not “affect the ability to have children in the future” [41].

A contraceptive method's noninterference in sex and partner relations was valued as well, mentioned in 141 articles. Contraceptive users often reported considering whether they or their partner(s) could feel the contraceptive method/device during intercourse, and how the contraceptive method affected the spontaneity, pleasure, and frequency of sex. Partner's influence towards women's contraceptive choice was also highlighted, where oftentimes “[m]en's disapproval over contraceptive use restricted preferences for women” [42], particularly in low- and middle-income countries regarding “non-natural” or hormonal contraceptives. Even in the USA, though, young women mentioned using withdrawal because of their male partners, though it “did not align with their own contraceptive desires,” since using a condom would imply lack of trust or relationship intimacy and they were embarrassed about using withdrawal as a contraceptive method [43].

Women were concerned about the impact of hormonal contraceptives on menstruation (mentioned in 83 articles), whether they desired regular menstrual cycles (to alleviate dysmenorrhea) or amenorrhea (to stop menstrual bleeding altogether for a specified time) or pain relief during menses; for example, a multimethod study in the US found contraceptive choice linked to menstrual control, suppression, and symptoms [44]. Some preferred “natural” or “nonartificial” nonhormonal methods in order to retain menstruation as a tangible symbol of health and fertility [45].

Cost—the financial burden to pay for the contraceptive method itself and the services of a health worker, in addition to time and transport/distance—was important to users (reported in 71 articles). Two-thirds of the mentions of cost/affordability/accessibility appeared in articles originating from the USA and other high-income countries, with two-thirds of such articles (29/45, 64%) discussing LARCs. However, among articles that ranked the contraceptive attributes that end-users considered important, cost/affordability usually ranked below effectiveness and side effects.

In 67 articles, people expressed the desire to have a sense of control and autonomy over contraceptive decision-making or usage. For example, one article noted that users wanted to make the choice of birth control method that was “right for them when given the proper information and options” [36]. In choosing a contraceptive method, women also considered whether they needed a health worker to insert/remove or administer the method or if they could self-administer—and what training or education was needed prior to use (e.g., demonstration, training, supervision, product storage, waste management).