Abstract

Objective:

To analyze distribution of “dramatic”, large treatment effects.

Study Design & Setting:

Pareto distribution modeling of previously reported cohorts of 3,486 randomized trials (RCTs) that enrolled 1,532,459 patients and 730 non-randomized studies (NRS) enrolling 1,650,658 patients.

Results:

We calculated the Pareto α parameter, which determines the tail of the distribution for various starting points of distribution [odds ratiomin (ORmin)]. In default analysis using all data at ORmin ≥1, Pareto distribution fit well to the treatment effects of RCTs favoring the new treatments (p=0.21, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) with best α=2.32. For NRS, Pareto fit for ORmin ≥2 with best α=1.91. For RCTs, theoretical 99th percentile OR was 32.7. The actual 99th percentile OR was 25; which converted into relative risk (RR)=7.1. The maximum observed effect size was OR=121 (RR=11.45). For NRS, theoretical 99th percentile was OR=315. The actual 99th percentile OR was 294 (RR=13). The maximum observed effect size was OR=1473 (RR=66).

Conclusions:

The effects sizes observed in RCTs and NRS considerably overlap. Large effects are rare and there is no clear threshold for dramatic effects that would obviate future RCTs.

Keywords: large or dramatic treatment effects, randomized trials, observational studies, statistical modeling, methodology, FDA

INTRODUCTION

Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain a method of choice to reliably assess effects of health interventions, historically some treatments have been adopted in clinical practice based on non-randomized studies (NRS). Insulin for treating diabetes, penicillin for streptococcal pneumonia, blood transfusion for hemorrhagic shock, or chest tube placement for pneumothorax are examples of treatments accepted in practice without testing in RCTs.1 Typically, these treatments have shown “dramatic effects” (DE)-effects that are considered so large (“dramatic”, “between-the-eyes-treatment effects”2) that they are believed to override the combined effects of the biases and random errors that can affect the results of any study.1 The key assumption for relying on NRS for detecting DE is that such large effects are unlikely to be observed in RCTs.

However, is there a threshold of effects that cannot be derived in RCTs? If such a threshold can theoretically and empirically be derived, we would be in better position to allocate scarce resources, and indeed address the crucial clinical research question: “when RCTs are not necessary?” Here, we aim to derive an empirical DE threshold by re-analyzing large numbers of previously reported RCTs.3-7 We also contrasted thus defined DE with effect sizes observed in datasets of NRS.7,8

METHODS

Foundational principles

Testing in RCTs is based on the principle that the results in each individual trial should be unpredictable: only if there are genuine uncertainties- often referred in the literature as ‘equipoise’, ‘the uncertainty principle’ or ‘the indifference principle” 9- about the relative merits of competing alternative treatments, undertaking a RCT is justifiable. If such uncertainty does not exist, as in case when there is a high likelihood (say, greater than 80-90%10,11) that one treatment is predictably better than the other, scientifically no meaningful results would be generated, it would be unethical to enroll people in such a trial,9 5 ethical committees would likely not approve it10,11 and well-informed patients would likely refuse to participate.5,9 However, this unpredictability of the results at the level of individual trial led to hypothesis that there is a predictable relationship between the uncertainty requirement (the moral principle) on which trials are based and the distribution of treatments effects at the group level of cohort(s) of clinical trials.5,9,12-14 That is, it can be predicted that when overall distribution of all treatment effects is evaluated, the probability of finding that a new treatment is better than a standard treatment is about 50%.5,9,12-14 Empirical analysis of multiple cohorts of RCTs has confirmed that, on average, new treatments appear better than standard ones just over half the time (50-70%, depending on outcome).3-6,15,16 This may reflect the combination of genuine improvements with new treatments and biases favoring new treatments.17.

Theoretical justifications for using Pareto distributions to model treatment effects

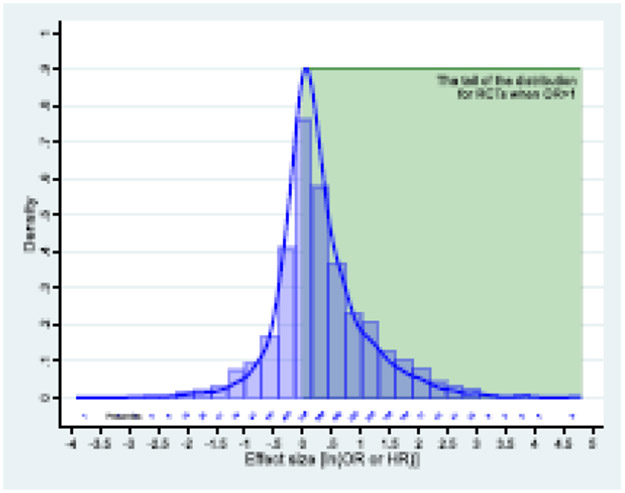

If new treatments are slightly more favored than standard ones, this will result in a skewed distribution of effects with heavy tail (Fig 1).4 Normal distribution would be expected if patients and investigators are truly and equally uncertain among competing treatment alternatives4 and if, additionally, no bias exists favoring new treatments. In reality, however, researchers and funders/manufacturers spend years on developing new treatments, and even though uncertainty requirement prevents them from undertaking a RCT when sufficient uncertainty cannot be claimed, the investigators (and funders) would not proceed with a RCT if they would not “bet” on the treatment they are developing.4

Fig. 1.

a) Effects size observed in 8 cohorts of 3365 randomized trials across different medical fields 3-6 (blue line); the green rectangle represent the zone of large effects- the focus of the study.

The increase in the relative probability of success as function of efforts invested is a form of so called “preferential attachment” process, a mechanism that generates a family of mathematical distributions known as Pareto or power law.18 Thus, we postulated that the power law -an ubiquitous phenomenon that describes a wide range of natural, economic, and social phenomena18 - is the best candidate distribution to investigate DE in RCTs.

The equipoise principle typically does not apply to observational studies; although the investigators still cannot perfectly predict future results, they often have some sense of what they expect to see.9,19 That is, one would expect that NRS would be even more selected for presentation of extreme, highly successful treatments. This means that the preferential attachment mechanism18 is expected to operate in NRS even more forcibly than in RCTs, making Pareto distribution a natural theoretical choice for modeling treatment effects in NRS as well.

Datasets

Databases of RCTs

We have previously assembled a database of 7 cohorts of 1137 consecutive RCTs enrolling 383,778 patients with mean sample size of 372 (range: 20 to 9,869) across different clinical disciplines. 3-6,15,20 Our empirical assessment of distribution of the effect sizes in these trials were consistent with equipoise principle.3-6,15,20 We judged these trials to reflect mostly genuine effects rather than biases.3-6

We also used another published dataset of RCTs from the field of emergency medicine (EM). This dataset was assembled by compiling meta-analyses of clinical trials across the entire field of EM. We excluded 244 RCTs that had used standardized mean difference (SMD) as the metric of choice, and kept for the analysis 2349 RCTs enrolling 1,148,681 patients.7 In total, we had 3486 trials enrolling 1,532,459 patients available for the analysis.

A main difference between the EM set of trials and the other cohorts of trials is that the former was assembled by literature searches while the latter was selected based on the list of all trials provided by funders. Therefore, the EM cohort is possibly affected by publication bias and may also suffer more from other biases, since a larger share of RCTs were small and possibly of questionable quality with predictably larger effect sizes than in our other cohorts. In sensitivity analyses, we separately report on the effect sizes from both cohorts. Throughout the rest of the manuscript we refer to these 7 cohorts as “consecutive cohort” of RCTs vs “literature cohort” of RCTs for the EM trials.

Databases of NRS

An analysis of decisions of regulators to approve treatments for the use in practice based on large effects observed in NRS probably represents the best direct answer to the question “how large are large effects” that people are willing to accept without requiring additional RCTs. To empirically address this question, we have combined the EMA Priority Medicines 21 and the FDA22 Breakthrough Therapy databases of NRS (n=134) that served as the basis for drug approval by these agencies.8 For this analysis, we also reviewed all FDA approvals based on single arm NRS (n=72) made via the Accelerated Approval (AA) pathway 23 since the program was established in 1992 until December 2020. In total, these three databases (“consecutive cohort of NRS”) comprised of 206 NRS and 63,147 patients.

We also considered a separate database of NRS in the field of EM that were included in the EM meta-analyses as described above.7 After excluding 12 NRS that used SMD as the metric of choice, we kept 524 studies with 1,587,511 participants.

Combining all NRS datasets, we had 730 NRS enrolling 1,650,658 patients available for analysis. We also present results separately for the EM dataset and the other datasets. Again, we aim to describe the largest observable effect sizes without necessary distinguishing between the bias and true effects.

Treatment effects

For both RCTs and NRS, we express treatment effects as odds ratios (ORs), although some were hazard ratios. OR>1 indicates improving desirable patient outcomes favoring new treatments over controls. Some studies also reported baseline risk enabling conversion of OR to relative risk (RR).

Modeling distribution of treatment effects

Fig 1 shows the distribution of logarithms of treatment effects in all 3,365 RCTs.3-6,15,16 A kernel density method was used to control for between and within-study variance across all trials as previously described.6 Shapiro-Wilks test confirmed that data significantly deviated from normality (z=10.7; p<0.0001). The power law is only applicable to analysis of the tail of the distributions18,24 i.e., where large effects are plausibly concentrated (Fig 1, green box) (Appendix).

In the power law probability distribution (p(x)= C * x−α) α determines the tail of distribution, and xmin, determines where the “fat tail” starts. Here, x=OR. For α< 3, standard deviation and variance remain mathematically undefined. For α >1, the largest value, Xmax remains unbounded but asymptotically tends to infinity.

Empirical validation of Pareto distribution

As explained, the power law applies only to values greater than some minimum value xmin..18,24 That is, it is the tail of distribution that follows a power law and we need to select that zone of interest (Fig 1).24,25 Different cut-offs for selection of xmin are possible. One approach would be to select OR=2 as xmin based on the beliefs that the minimum ratio of treatment effects between two alternative therapies greater than 2 can be considered large.26 Another would be to select all data for OR>1 i.e., all potentially “successful” treatments. While Pareto distribution fit well for either of these cut-offs in the consecutive cohort of RCTs, for all data combined, the best fit was obtained for ORmin=1, which we selected for our main analysis.

Defining dramatic effects threshold

Our main goal was to attempt to derive a DE threshold. That is, we aimed to find the largest effects (actual maximum and theoretical 99th percentile) that could be detected in RCTs. We then calculated the number of NRS with the effect size exceeding DE as thus defined.

RESULTS

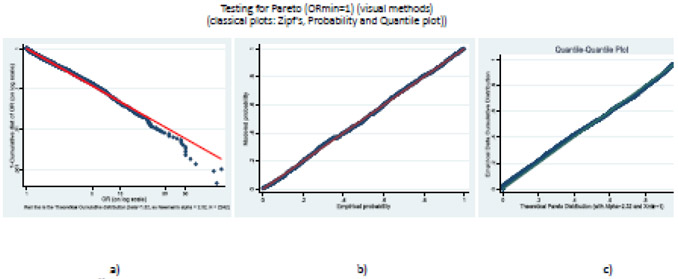

Using the procedure proposed by Clauset et al24 we could not reject the null hypothesis that our data from all RCTs combined are derived from the Pareto distribution for ORmin=1 [Kolmogornov-Smirnov (KS) statistic, D=0.029; p=0.21]. Fig 2 complements this analysis by showing the fit of our empirical data against the theoretical power law distribution employing three standard, widely used graphical techniques:18,24 the Zipf plot based on the classic theoretical considerations discussed earlier (Fig 2a), the Probability Plot comparing empirical with model probabilities (Fig 2b) and the Q-Q plot contrasting the quantiles from our empirical data against the theoretical Pareto distribution (Fig 2c). In all cases, we observed relatively straight lines demonstrating a good fit to the Pareto distribution.

Fig. 2.

Graphical validation of power law distribution (for ORmin=1). a) Zipf’s plot, b) Probability Plot, c) Q-Q plot. The plot compares the empirical versus the modeled cumulative distribution function. The straight lines indicate good fit.

For RCTs, we found best α=2.32. For α < 3, the standard deviation and variance remain mathematically undefined.18 However, the mean is still calculable. The theoretical mean for DE based on RCTs corresponds to OR=4.13 while the actual mean was OR=3.26 based on our data. For α > 1, the largest value, Xmax remains unbounded but asymptotically tends to infinity:18

as n (the number of studies) become larger (see Appendix). The actual maximum in our data corresponded to OR=121.

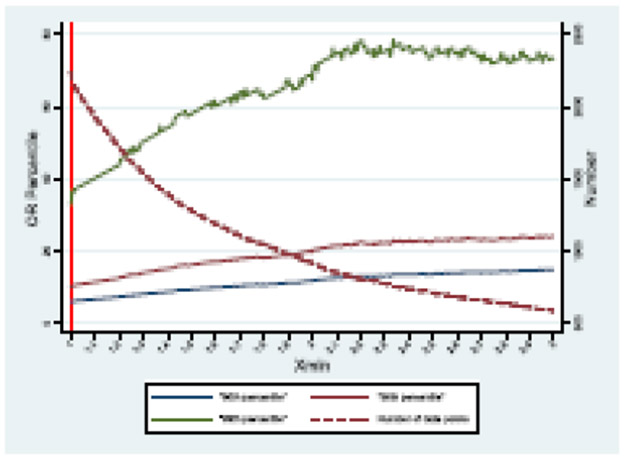

The percentiles are calculable. Fig 3 shows a theoretical distribution of 90-99 percentiles as a function of assumed ORmin and the number of trials above ORmin..

Fig. 3.

A theoretical distribution of 90-99 percentiles as a function of assumed ORmin and the number of trials.

Table 1 summarizes the results of the main analyses. For example, for ORmin=1, we determined the theoretical 99th percentile OR=32.7 vs actual 99th percentile OR=25; the latter converts into RR=7.1 Note that α depends both on ORmin and number of trials (see Appendix), but most differences across different analyses and subgroups were modest. For RCTs, we were able to fit Pareto distribution for both cohorts at ORmin≥1 (n=2242). Data for the consecutive cohort fit Pareto for all ORmin cut-offs but for the literature-based cohort fit was obtained for ORmin≥2.5 (N=650 trials). For both cohorts, α was similar (2.51 vs 2.35).

Table 1.

Pareto distribution parameters: summary of sensitivity analyses

| Study type |

Subgroup | ORmin (trials) |

α | 99th percentile OR (RR)# | Mean OR | Max OR (RR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Actual | Theoretical | Actual | Theoretical | Actual | ||||

| RCTs | All data | 1 (2242) | 2.32 | 32.7 | 25 | 4.125 | 3.26 | undefined | 1211 (11.45) |

| 2.5 (714) | 2.36 | 73.8 | 50 | 9.44 | 7.14 | undefined | 121 (11.45) | ||

| Consecutive cohort | 1 (631) | 3.37 | 6.98 | 25 | 1.72 | 3.26 | undefined | 121 (11.45) | |

| 2.5 (64) | 2.51 | 52.77 | 45.01 | 7.40 | 6.38 | undefined | 452 (15) | ||

| Literature-based cohort | 1 (1611) | NE | NE | 29.76 | NE | 3.8 | NE | 121 (11.45) | |

| 2.5 (650) | 2.35 | 75.75 | 50 | 9.64 | 7.21 | undefined | 121(11.45) | ||

| NRS | All data | 2 (311) | 1.91 | 315.37* | 2943,* (13) | undefined | 21.29* | undefined | 14734,* (66) |

| Consecutive cohort | 2 (132) | 1.55 | 8657* | 7565,* (27) | undefined | 44* | undefined | 14734,* (66) | |

| Literature-based cohort | 2 (179) | 2.75 | 27.79 | 27.59 | 4.66 | 4.52 | undefined | 47.76 (6) | |

RCTs: randomized controlled trials; NRS: non-randomized studies, OR: odds ratio, RR: risk ratio, ORmin: start point of the Pareto distribution (tail). NE-not evaluable (Pareto distribution could not be fit)

corrected for zero events (see methods)

when baseline risk was available, we converted OR into RR;

Topical diclofenac vs placebo for pain control;

- anti-emetics vs placebo for radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (N/V) ;

- d-a-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol-1000 succinate for chronic childhood cholestasis; (to calculate RR we assumed that one patient out of 14 in the control group had response vs 63/66 in the experimental arm)

Reversal of anticoagulation effects of dabigatran in patients who presented with serious bleeding or who required urgent surgery or intervention (original report described none out of 68 patients had reversal in the control group vs 65 out 68 in the experimental group; to calculate RR we assumed that one patient in the control group had reversal);

-this study describes the effect of retinal prosthesis device for retinitis pigmentosa (to calculate RR we assumed that one patient out of 28 in the control group had response vs 27/28 in the experimental arm);

prothrombin complex concentrate vs fresh frozen plasma on rate of INR reversal induced by warfarin. abbreviations: RCT- randomized controlled trials; NRS- nonrandomized studies; see Table 2 for further descriptions of RCTs and NRS that exceeded theoretical dramatic effect threshold.

For NRS, we could not fit Pareto distribution for ORmin=1, but could for ORmin=2 for both the combined data and separately for the consecutive and literature-based cohorts. Unlike for RCTs, where α>2, for NRS we obtained α=1.91, which has no finite means. This was driven primarily by the consecutive NRS cohort, where we found α=1.55, while the literature-based cohort of NRS on EM treatments had α=2.75, which corresponded to a theoretical mean OR=4.66 (actual 4.52).

Overall, less than 1% of treatments tested in RCTs exceeded actual (23/3365) and theoretical (18/2242) 99th percentile effect size. Table 2 displays effect size observed in RCTs and NRS that exceeded our definition of dramatic effect (theoretically predicted 99th percentiles). For all RCTs, 18 studies exceeded the theoretically predicted 99th percentiles of OR=32.7 for ORmin=1. Almost all of these trials (16/18) came from the literature-based cohort. Of note, the large majority of these 18 studies had small sample size and the meta-analytic treatment effect of all RCTs done on the same topic and intervention comparison was typically more modest. This suggests that bias was probably a key driver of these extreme effects.

Table 2.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies (NRS) with treatment effect sizes exceeding the theoretical 99th percentile*

| A) consecutive cohort of RCTs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponsor or First Author and Year of Study |

Experimental Group |

Control Group | Outcome | Sample size (N) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Meta-analysis Odds Ratio** (95% CI) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1993 | Anti-emetics | Placebo | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 174 | OR:7.59(3.74 to 15.38) RR:2.5(1.76 to 3.5) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1994 | Anti-emetics | Placebo | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 164 | OR:7.81(3.75 to 16.23) RR:2.72(1.83 to 4.05) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| UK HTA,1999 | HIV testing (comprehensive discussion) | No intervention | Access to health services | 1513 | OR:7.88 (5.67 to 10.95) RR:5.71 (4.28 to 7.6) |

1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) |

| ECOG,1973 | Active Rx1 | Active Rx2 | Prostate cancer (tumor response) | 51 | OR:7.89 (0.88 to 71.21) RR:6.24 (0.81 to 48.2) |

1.09 (1.06 to 1.11) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1990 | Anti-emetic Rx1 | Anti-emetic Rx2 | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 75 | OR:8.14 (2.52 to 26.28) RR:2.02 (1.32 to 3.07) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1995 | Anti-emetics | Placebo | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 81 | OR:8.91 (2.92 to 27.15) RR:2.67 (1.54 to 4.64) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| UK HTA,1999 | HIV testing (minimal discussion) | No intervention | Access to health services | 1489 | OR:9.01 (6.48 to 12.52) RR:6.24 (4.69 to 8.29) |

1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) |

| UK HTA,1999 | All blood testing (minimal discussion) | No intervention | Access to health services | 1489 | OR:9.67 (6.96 to 13.42) RR: 6.53 (4.92 to 8.66) |

1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1994 | Anti-emetics | Placebo | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 160 | OR:9.89 (4.59 to 21.31) RR:2.87 (1.94 to 4.26) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| UK HTA,1999 | All blood testing (comprehensive discussion) | No intervention | Access to health services | 1515 | OR:10.04 (7.25 to 13.9) RR:6.69 (5.05 to 8.85) |

1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) |

| SWOG,1979 | Active Rx1 | Active Rx2 | Ovarian cancer (tumor response) | 74 | OR:10.38 (3.39 to 31.74) RR:2.4 (1.5 to 3.86) |

1.09 (1.06 to 1.11) |

| MRC,1977 | Neutron radiotherapy | Photon radiotherapy | Head and neck cancer (tumor response) | 133 | OR:13.25 (5.76 to 30.47) RR:3.97 (2.34 to 6.72) |

1.2 (1.04 to 1.11) |

| COG,1997 | Active Rx1 | Active Rx2 | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (incidence of antibody production) | 118 | OR:15.81 (1.94 to 128.6) RR: NA# |

1.09 (1.06 to 1.11) |

| GlaxoSmith, 2000 | Active Rx1 (amprenavir + retrovir + epivir) | Active Rx2 retrovir + epivir + placebo) | HIV (viral response rate) | 232 | OR:19.76 (6.82 to 57.25) RR:12 (4.47 to 32.19) |

2.51 (1.9 to 3.3) |

| UK HTA,2003 | Image guided Hickam line placement | Blind placement | Misplacement rate | 470 | OR:36.88 (4.99 to 272.34) RR:1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) |

1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) |

| GlaxoSmith, 1990 | Anti-emetics | Placebo | Chemo/radiation-induced emesis | 20 | OR:45 (2.01 to 1006.7) RR:15 (0.97 to 231.04) |

1.65 (1.42 to 1.92) |

| B) Literature-based cohort of RCTs | ||||||

| Sponsor or First Author and Year of Study |

Experimental Group |

Control Group | Outcome | Sample size (N) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Meta-analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI)** |

| Jerges-Sanchez 1995 | Thrombolysis | Conventional anticoagulation | Survival in pulmonary embolism | 8 | OR:33.3 (2.5 to 100) RR:8.0 (0.6 to 106.9) |

1.89 (1.14 to 3.12) |

| Thompson 1996 | Oral corticosteroids | Placebo | Treatment success in acute COPD | 27 | OR:33.3 (1.75 to 100) RR:14.9 (0.94 to 233.7) |

2.08 (1.49 to 2.86) |

| Cavus 2011 | Video laryngoscopy | Macintosh direct laryngoscopy | Successful intubation | 150 | OR:33.3 (1.61 to 100) RR:24.0 (1.37 to 421.2) |

2.86 (1.54 to 5.26) |

| Oandasan 1999 | Probiotics | Usual care | Infectious diarrhea recovered within 4 days | 94 | OR:40.5 (5.24 to 312.7) RR:22.0 (3.1 to 156.6) |

3.49 (2.94 to 4.13) |

| Elliot 1979 | Thrombolysis | Conventional anticoagulation | Complete clot lysis (for leg venous thrombosis) | 51 | OR:44.6 (2.51 to 794.1) RR:23.1 (1.44 to 370.2) |

2.11 (1.52 to 2.91) |

| Mathew 1992 | Subcutaneous sumatriptan | Placebo | Migraine relief within 2 hours | 92 | OR:45.0 (9.8 to 206.7) RR:18.6 (4.61 to 75.0) |

8.29 (6.83 to 10.07) |

| S2BMO3 (unpublished) | Subcutaneous sumatriptan | Placebo | Migraine relief within 2 hours | 168 | OR:47.0 (14.1 to 156.0) RR:17.4 (5.66 to 53.3) |

8.29 (6.83 to 10.07) |

| Taylor 2013 | Video laryngoscopy | Macintosh direct laryngoscopy | Successful intubation | 88 | OR:50 (3.57 to 100) RR:36.0 (2.24 to 579.6) |

2.86 (1.54 to 5.26) |

| Christ-Crain 2004 | Procalcitonin-guided treatment | Usual care | No need to use antibiotics in acute asthma | 13 | OR:50 (1.9 to 1313.6) RR:13.3 (0.8 to 223.2) |

4.86 (3.2 to 7.37) |

| Brazel 1996 | Isotonic maintenance fluid | Hypotonic maintenance fluid | Avoiding hyponatremia in ill pediatric patients | 12 | OR:50 (1.49 to 100) RR:5.0 (0.87 to 28.9) |

2.78 (1.96 to 3.85) |

| Peck 2009 | Video laryngoscopy | Macintosh direct laryngoscopy | Successful intubation | 54 | OR:50 (2.86 to 100) RR:26.0 (1.62 to 416.5) |

2.86 (1.54 to 5.26) |

| Beatch 2016 | Vernakalant | Placebo | Conversion to sinus rhythm within 90 minutes for atrial fibrillation | 197 | OR:56.5 (7.66 to 416.5) RR:31.1 (4.4 to 219.6) |

6.83 (5.05 to 9.24) |

| Patterson 1963 | Idoxuridine | Placebo | Complete healing by 7 days for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis | 30 | OR:64.4 (3.48 to 1191.7) RR:19.3 (1.24 to 298.7) |

3.72 (2.44 to 5.69) |

| Woo 2012 | Video laryngoscopy | Macintosh direct laryngoscopy | Successful intubation | 159 | OR:100 (7.14 to 100) RR:54.1 (3.41 to 858.1) |

2.86 (1.54 to 5.26) |

| Goldman 2001 | NSAIDs | Placebo | Pain relief in biliary cholic | 40 | OR: 107.7 (27.46 to 422.2) RR:6.33 (2.22 to 18.1) |

12.83 (6.28 to 26.3) |

| Predel 2004 | Topical diclofenac | Placebo | Clinical success in treating pain | 120 | OR: 121 (45.3 to 323.4) RR:11.45 (4.74 to 25.6) |

2.98 (2.47 to 3.60) |

| C) Consecutive cohort of NRS | ||||||

| Sponsor or First Author and Year of Study |

Experimental Group |

Control Group | Outcome | Sample size (N) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Meta-analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI)** |

| FDA Devices Approval Program,2002 | Enterprise Vascular Reconstruction Device and Delivery System | Self-control (baseline vs 6 months follow-up) | ≥95% occlusion of aneurysm (natural history) (at 6 months follow-up) | 52 | OR:676 (40.1 to 11393) RR:26 (3.79 to 178) |

5.48 (3.35 to 8.97) |

| FDA Devices Approval Program,2013 | Argus II retinal prosthesis system | Self-control: device on vs device off | Object localization (Severe to profound retinitis pigmentosa) | 56 | OR:756 (44.98 to 12705) RR:27.9 (4.07 to 192) |

5.48 (3.35 to 8.97) |

| FDA breakthrough approval,2015 | Idarucizumab | No active treatment | Reversal of anticoagulation effects of dabitragan | 136 | OR1473.3 (149 to 14528) RR:65.9 (9.41 to 461.9) |

4.26 (3.03 to 5.98) |

| B) Literature-based cohort of NRS | ||||||

| Sponsor or First Author and Year of Study |

Experimental Group |

Control Group | Outcome | Sample size (N) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) Relative Risk (95% CI) |

Meta-analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI)** |

| Cartmill 2000 | Prothrombin Complex Concentrate | Fresh Frozen Plasma | Rate of rapid INR reduction for warfarin reversal | 12 | OR:47.7 (1.6 to 1422.7) RR:6.0 (1.0 to 35.9) |

10.8 (6.12 to 19.1) |

theoretical 99 percentile threshold calculated according to Pareto distribution (see Table 1) and trials are listed in the table if their treatment effect is larger than the theoretical 99 percentile for all data with the same design or for the data in the respective cohort of trials with the same design. The theoretical 99 percentile was OR=32.7 for all RCTs data, OR=6.98 for consecutive cohort of RCTs, OR=75.5 for literature-based cohort of RCTs, OR=315.37 for all NRS data, OR=8657 for consecutive cohort of NRS, OR=27.79 for literature-based cohort of NRS)*;

calculated using normal distribution;

NA- no data available to calculate RR. Text in italics refers to the literature-based cohort for ORmin=2.5 for which theoretical 99 percentile threshold was calculated as OR=73.8 (see Table 1).

The effect size exceeding the theoretical DE threshold of OR=32.7 varied from OR=33.3 (RR=8) to OR=121 (RR=11.45). For RCTs at ORmin=2.5, three trials exceeded the theoretical threshold of OR=73.8 with effect sizes ranging from OR=100 (RR=54.1) to OR=121 (RR=11.45). In the consecutive cohort of RCTs, 16 trials exceeded theoretically predicted DE threshold of OR=6.98 (for ORmin=1). The effect size varied from OR=7.59 (RR=2.5) to OR=45 (RR=15) (Table 2).

For all NRS, three studies exceeded the theoretical 99th percentile of OR=315.37. The effect sizes ranged from OR=676 (RR= 26) to OR=1473 (RR=65.9) all based on the FDA approval studies (Table 2). No study exceeded the theoretical DE threshold in the consecutive cohort while one study [OR=47.7 (RR= 6 )] in the literature-based cohort had effect size exceeding the theoretical threshold of OR=27.79 (Table 2).Overall, between 4% (30/730) and 5% (37/730) of NRS displayed effects larger than the actual [OR=25 (RR=7.1)] and the theoretical [OR=32.7] 99th percentile effect displayed in all cohorts of RCTs.

DISCUSSION

We propose that treatment effects sizes adhere to Pareto distribution. Such a distribution may be a direct consequence of the equipoise principle – a scientific and ethical foundational principle of RCTs-4 3-6,15,16 coupled with the mechanism of “preferential attachment”18, which accounts for distribution of the larger treatments effects in the “fatter” part of the Pareto tails.

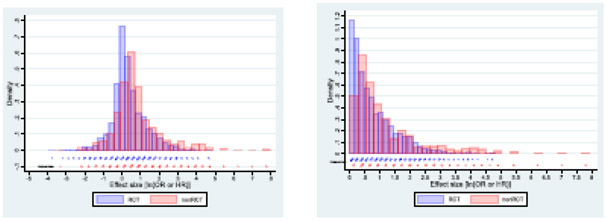

Because RCTs are often complex and expensive to undertake, there is a quest to determine conditions under which NRS and real world evidence can be used instead to generate reliable treatment estimates.1 26,27 The focus has been on finding large effects in the NRS that are believed that could not be observed in RCTs. Here, we provide a formal assessment that a single clear threshold effect size above which RCTs are not necessary is not theoretically determinable. As expected, large (dramatic) effect sizes are rare and are concentrated in the tails of distribution. Empirically we found that there is less than 1 % of the probability that treatment effect in RCTs can exceed OR=25 (RR~ 7) with the largest, maximum effect observed in our data set being OR=121 (RR~12). Similarly, fewer than 5% of NRS displayed effects larger than the actual [OR=25 (RR=7.1)] and the theoretical [OR=32.7] 99th percentile effect displayed in all cohorts of RCTs. However, even in these cases effects were likely heavily biased.

Our analyses suggest that it may be impossible to establish a robust threshold for DE that would obviate further RCTs. Our inferences using Pareto distribution crucially depend on the α value. We determined α=2.32 in the main analysis including all the RCTs data. This is consistent with values of the α parameter found in Pareto distributions describing most other natural and sociological phenomena including frequency of use of words, number of citations to papers, magnitude of earthquakes, net worth of Americans etc.18,24 25 Mathematically, for α<2, means are undefined18; that is, the events for these α values are essentially unforecastable. In fact, a conservative heuristic has been proposed that for all α ≤2.5 means are practically unforecastable as they require more observations that can be obtained in the real world.28 For all NRS, we determined α=1.91 (or even 1.55, when limited to the consecutive cohort), which is also observed in some empirical phenomena such as intensity of wars or solar flare intensity.24For α< 3, the standard deviation and variance also remain mathematically undefined.18 In general, we observed major overlap between effect sizes in RCTs and NRS (Fig 4) even though some NRS from the EMA and the FDA cohorts had huge ORs not observed in RCTs. However, when converted into RR and in consideration with α<2 indicating intrinsically unstable findings, these results would very likely, on repeated studies, fall above as well as below DE threshold. Taken together, the results indicate that it is not possible to predict a threshold above which RCTs would not be required.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of effect sizes in randomized and non-randomizes studies. A) all data, b) restricted to ln(OR)>0 i.e. OR>1

A previous study29 determined that large effects are “vanishingly small, and where they occur they do not appear to be a reliable marker for a benefit that is reproducible and directly actionable.”29 The largest effect observed in that study29 had RR=48.64 (hepatitis B vaccine vs placebo). We also note that the EMA and the FDA approved between 7 to 10% of treatments based on non-RCT comparisons; of these, between 2% and 4% displayed “dramatic” effects21,22, defined as relative risks (RR)>2 26, RR ≥5 30, or RR≥10.1

Our findings are subject to certain limitations. The distribution of reported effects is shaped not only by the genuine effects, but also by biases and selective reporting practices favoring extreme effects. This may be more prominent for emergency medicine trials than the consecutive trials. Most large effects may also be affected by bias particularly because of poor choice of comparator.21 22 Notably, most studies (18/32 RCTs and 3/4 NRS) with effects exceeding DE threshold employed placebo or no intervention as comparators; only one study (N=8) had survival as outcome.

Further examination of each study and each topic assessed by these studies in-depth to identify biases in single studies and in the whole topic could shed additional lights on specific biases that can explain observed findings. The RCTs and NRS compared here came from the same disciplines, but their representation might have been different within specific topics and effects may have been genuinely different in these topics. Our analysis examined studies from mostly two fields, emergency medicine and oncology. Future research may examine if similar patterns are seen also in other disciplines and by sets of studies serving different purposes (e.g. regulatory versus inclusion in systematic reviews).

Eventually, determination whether a particular effect is “dramatic” or not will always have to be judged within a context of basic science, preclinical, clinical testing, and analytic framework - statistical and cognitive-31-33 of the specific treatment under consideration.

Supplementary Material

What is already known on this topic

Distribution of treatment effects is skewed with heavy tails in favor of experimental treatments displaying large, “dramatic” effects.

That is, distribution of treatment effects is not normal, but it is not clear which statistical distribution treatment effects adhere to

Understanding distribution of effects of treatments tested in randomized trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies (NRS) has important implications for testing of new treatments, including answering one of the most important clinical research question of today: “When RCTs are not necessary?”

What this study adds

We found that treatments effects tested in RCTs and NRS adhere to power law (Pareto distribution)

Pareto distribution has important properties most of which is that for certain parameters alpha (<3, which we observed in our study), dramatic, large effect size are undefined and theoretically unforecastable/unpredictable

This means that it is not possible to define dramatic effect threshold above which further RCTs would not be necessary

Effect sizes in RCTs and NRS are indistinguishable/overlap with no indication that larger effects are seen more often in NRS than in RCTs

What is the implication and what should change now?

Search for large effects to obviate the need for RCTs is futile and should be abandoned

Eventually, determination whether a particular effect is “dramatic” or not will always have to be judged within a context of basic science, preclinical, clinical testing, and analytic framework -statistical and cognitive-of the specific treatment under consideration

Acknowledgment

Data sets for this work were obtained with support of the grant by the US National Institute of Health R01CA140408, R01NS044417, R01NS052956, R01CA133594 (Djulbegovic)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

BD conceptualized the study and wrote the first draft; IH developed statistical codes and analyses; AJP collected most data; JPAI revised a paper and proposed additional analyses. All authors contributed to the final draft. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria. BD is the guarantor

Conflict of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest in relation to this paper.

References

- 1.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, McCulloch P. When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise. BMJ. 2007;334(7589):349–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson JK, Hauben M. Anecdotes that provide definitive evidence. Bmj. 2006;333(7581):1267–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Miladinovic B, et al. Treatment success in cancer: industry compared to publicly sponsored randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Soares HP, et al. Treatment success in cancer: new cancer treatment successes identified in phase 3 randomized controlled trials conducted by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored cooperative oncology groups, 1955 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):632–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Glasziou P, Miladinovic B, Chalmers I. Medical research: Trial unpredictability yields predictable therapy gains. . Nature. 2013;500(7463):395–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Glasziou PP, et al. New treatments compared to established treatments in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:MR000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parish AJ, Yuan DMK, Raggi JR, Omotoso OO, West JR, Ioannidis JPA. An Umbrella Review of Effect Size, Bias and Power Across Meta-Analyses in Emergency Medicine. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2021;e-pub , online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djulbegovic B, Razavi M, Hozo I. When are randomized trials unnecessary? A signal detection theory approach to approving new treatments based on non-randomized studies. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djulbegovic B Articulating and responding to uncertainties in clinical research. J Med Philosophy. 2007;32:79–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhaskar R, Bercu B, Djulbegovic B. At what level of collective equipoise does a randomized clinical trial become ethical for the members of institutional review board/ethical committees? Acta Inform Med. 2013;21(3):156–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mhaskar R, Miladinovic B, Guterbock TM, Djulbegovic B. When are clinical trials beneficial for study patients and future patients? A factorial vignette-based survey of institutional review board members. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Djulbegovic B The paradox of equipoise: the principle that drives and limits therapeutic discoveries in clinical research. Cancer Control. 2009;16(4):342–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet. 2000;356:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers I What is the prior probability of a proposed new treatment being superior to established treatments? BMJ. 1997;314:74–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares HP, Kumar A, Daniels S, et al. Evaluation of New Treatments in Radiation Oncology: Are They Better Than Standard Treatments? JAMA. 2005;293(8):970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Soares HP, Wells R, et al. What is the probability that a new treatment for cancer in children will be superior to an established treatment? An observational study of randomised controlled trials conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group. BMJ. 2005;331:1295–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ioannidis JPA. Why most published research findings are false. PLOS Med. 2005;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman MEJ. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf's law. Contemporary Physics. 2005;46:323–351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djulbegovic B Uncertainty and Equipoise: At Interplay Between Epistemology, Decision Making and Ethics. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342(4):282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, Soares H, Wells R, et al. Are experimental treatments for cancer in children superior to established treatments? Observational study of randomised controlled trials by the Children's Oncology Group. Bmj. 2005;331(7528):1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djulbegovic B, Glasziou P, Klocksieben FA, et al. Larger effect sizes in nonrandomized studies are associated with higher rates of EMA licensing approval. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2018;98:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razavi M, Glasziou P, Klocksieben FA, Ioannidis JPA, Chalmers I, Djulbegovic B. US Food and Drug Administration Approvals of Drugs and Devices Based on Nonrandomized Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysisDrug and Device Approvals Based on Nonrandomized Clinical TrialsDrug and Device Approvals Based on Nonrandomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9):e1911111–e1911111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaver JA, Pazdur R. “Dangling” Accelerated Approvals in Oncology. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clauset AR, Shalizi R, Newman MEJ. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Review. 2009;51:661–703. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cirilo P Are your data really Pareto distributed? Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2013;392:5947–5962. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins R, Bowman L, Landray M, Peto R. The Magic of Randomization versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(7):674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins R, Bowman L, Landray M. Randomization versus Real-World Evidence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(4):e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taleb NN, Bar-Yam Y, Cirillo P. On single point forecasts for fat-tailed variables. Int J Forecast. 2020: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2020.1008.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagendran M, Pereira TV, Kiew G, et al. Very large treatment effects in randomised trials as an empirical marker to indicate whether subsequent trials are necessary: meta-epidemiological assessment. BMJ. 2016;355:i5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence-publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rafi Z, Greenland S. Semantic and cognitive tools to aid statistical science: replace confidence and significance by compatibility and surprise. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2020;20(1):244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole SR, Edwards JK, Greenland S. Surprise! American Journal of Epidemiology. 2020;190(2):191–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland S Invited Commentary: The Need for Cognitive Science in Methodology. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2017;186(6):639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.