Abstract

Successful organ transplantation between species is now possible, using genetic modifications. This manuscript aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the differences and similarities in kidney function between humans, primates, and pigs, in preparation for pig-allograft to human xenotransplantation. The kidney, as the principal defender of body homeostasis, acts as a sensor, effector, and regulator of physiologic feedback systems. Considerations are made for anticipated effects on each system when a pig kidney is placed into a human recipient. Discussion topics include: anatomy, global kidney function, sodium and water handling, kidney hormone production and response to circulating hormones, acid-base balance, and calcium and phosphorus handling. Based on available data, pig kidneys are anticipated to be compatible with human physiology, despite a few barriers.

Keywords: Kidney, Pig, Renal function, Xenotransplantation

Introduction

A discrepancy exists between the number of patients requiring an organ transplant each year and the number of human organs available for transplantation. Xenotransplantation offers an alternative approach to the organ shortage. The introduction of increasingly sophisticated genetic engineering of the organ-source pig represents a major advance in reducing the immunogenicity of the porcine kidney in primate recipients. Genetically-engineered pig kidney grafts have been successfully transplanted into nonhuman primates (NHPs). With the use of an immunosuppressive regimen based on blockade of the CD40:CD154 costimulation pathway, porcine kidney grafts have functioned well with grossly stable volume status, urine output, and electrolyte levels for several months or even longer than a year.1,2 These preclinical trials suggest that a porcine kidney could function in a human recipient. However, in anticipation of clinical trials, it is important to further define pig kidney function in a human recipient.

In this review, we examine key aspects of kidney function and address potential challenges to xenotransplantation in humans. We initially compare components of renal function and physiologic differences between humans, pigs, and baboons. Baboons are currently a major model for preclinical xenotransplant research so a discussion on baboon renal physiology and observed clinical phenomenon in this in vivo model is also included. We then discuss more thoroughly how pig-to-human renal xenotransplantation may affect different aspects of renal physiology including global function (section 1), salt handling (section 2), water handling (section 3), endocrine function and production (section 4), renal response to hormones (section 5), acid/base balance (section 6), and calcium and phosphorus handling (section 7).

Summary of Potential Physiologic Barriers

Normal laboratory values differ between species (see Table 1). While differences in some areas are minor (e.g., serum sodium, potassium, and bicarbonate levels), others may have physiological significance (see Table 2). For example, pig kidneys see lower hemoglobin levels, which could alter erythropoietin production when transplanted in humans. Serum phosphate levels are 2x higher in pigs than in humans, which could interfere with bone health and hormonal balances between parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, and fibroblast growth factor 23 in human recipients. Lower circulating albumin concentrations in pigs would alter pressure gradients at the glomerulus, which could reduce filtration when pig kidneys are presented with higher albumin concentrations seen in humans. Medical therapies exist for some of the foreseeable differences between pig and human kidney function, and the available data suggest that a pig kidney will function adequately in a human recipient.

Table 1:

Comparison of average values of hematologic, biochemical, and urinary parameters between wild-type pigs, GTKO pigs, baboons, and (male) humans*.

| Test | WT Pig Mean (SD) | GTKO Pig Mean (SD) | Baboon Mean (SD) | Human (Male) Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematology | ||||

| WBC (x10^3/mm3) | 18.6 (6.4) | 15.5 (1) | 10 (1.7) | 4.5-11 |

| RBC (×10^6/mm3) | 6.9 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.4) | 5.1 (0.1) | 4.3-5.9 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10 (1.4) | 12.2 (2.5) | 12.7 (0.3) | 13.5-17.5 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.9 (8.7) | 37.9 (8) | 39.9 (1.3) | 41-53 |

| Platelets (×10^3/mm3) | 507 (156) | 425 (210) | 419 (61) | 150-400 |

| MCV (fL) | 59 (6) | 61.3 (9) | 77 (1) | 80-100 |

| MCH (pg/cell) | 17 (1) | 19.7 (2.3) | 25 (0) | 25.4-34.6 |

| Renal Parameters in Blood Samples | ||||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 143 (4) | 144 (7) | 146 (2) | 136-145 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.3 (1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.5-5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 104.8 (1.9) | 103 (8) | 108 (4) | 95-105 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 11 (0.8) | 10.8 (0.8) | 9.5 (0.5) | 8.4-10.2 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 8.6 (3.2) | 8.8 (1.8) | 4.3 (1.8) | 3.0-4.5 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 29 (4) | 28 (5) | 23 (3) | 22-28 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 12.4 (5.1) | 12.8 (9.9) | 14 (4) | 7-18 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6-1.2 |

| Osmolality | 291 mosm/kg79, 27076 | 275-295 | ||

| Serum pH | 7.48 | 7.35-7.45 | ||

| Hepatic Parameters | ||||

| AST (IU/L) | 40 (6) | 37 (29) | 37 (6) | 8-20 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 58 (17) | 42 (15) | 39 (6) | 8-20 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 263 (349) | 272 (146) | 638 (411) | |

| LDH (IU/L) | 826 (440) | 472 (109) | 284 (6) | 45-90 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 43 (12) | 74 (16) | 39 (18) | |

| Tot Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1-1.0 |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.4) | 6.8 (0.3) | 6.0-7.8 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.6 (0.6) | 3.4 (1.1) | 4.1 (0.3) | 3.5-5.5 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 125-200 (23) | 81 (22) | 103 (18) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 58 (29) | 31 (22) | 60 (8) | 35-160 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 92 (27) | 89 (27) | 96 (7) | 70-110 |

| Coagulation | ||||

| PT (sec) | 11.7 (0.6) | 13.6 (0.5) | 14.3 (1.9) | 11-15 |

| PTT (sec) | 15.5 (1.2) | 34.1 (14) | 32.6 (3.1) | 25-40 |

| D-Dimer (μg/mL) | 0.2 (0.05) | 0.7 (0.8) | ||

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 250 (121) | 190 (33) | ||

| Parameters in Urine Samples | ||||

| Sodium | 25.1 (mmol/L)79 | Varies based on physiology | ||

| Potassium | 87.1 (mmol/L)79 | Varies based on physiology | ||

| Osmolality | 685.9 (mmol/L)79 253 (mOsm/KG H20)76 | 50-1200 (mOsmol/kg H20) | ||

| Creatinine | 0.98 (g/l)79 change to mg/kg/hr | 15-25 mg/kg/hr | ||

| Urea | 17.6 (g/l)79 | Varies based on physiology | ||

| Glucose | <0.1 (g/l) | None | ||

| Proteins | 117 (mg/L)79 | <150 mg/day | ||

| Albumin | 1.68 (mg/dl)20 | 3 ug/min80 | none | |

| pH | 6.1379 | 4.5-8 |

Most of the nonhuman data were averages from several primary sources.81 Hemoglobin levels increase with age in pigs, and adult pigs can have a hemoglobin value of approximately 12g/dl.82 Comprehensive urinary studies in baboons are limited.

WT, wild type; GTKO, galactosltransferase gene knockout ; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH mean corpuscular hemoglobin; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time

Table 2:

Summary of anatomic and physiologic comparisons and potential physiologic barriers between human and pig kidneys based on various aspects of renal function.

| Renal Physiology Component | Comparison and Potential Barrier |

|---|---|

| Anatomy | Gross renal anatomy, including kidney size and vascular configuration, is comparable between humans and pigs. Pigs have fewer nephrons and a lower percentage of long-looped nephrons, and thus have a reduced ability to concentrate urine. |

| Global function | Markers of renal function, including glomerular filtration rate and renal plasma flow, are comparable between humans and pigs. It remains unknown how long these parameters would be stable following kidney xenotransplantation. Pigs also have similar levels of urine albumin, and recent experiments in in vivo models suggest that development of proteinuria is associated with rejection. |

| Sodium handling | Human angiotensin is a poor substrate for pig renin and the clinical impact on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system following xenotransplantation is unknown. Major electrolyte levels, including sodium, potassium, and chloride, are maintained in nonhuman primates (NHPs) with pig kidneys , showing that a homeostatic system is functional. NHPs experience episodes of hypovolemia following xenotransplantation which may result from physiologic differences in renin across species. |

| Water handling | Human antidiuretic hormone (ADH) has a different structure to pig ADH and is less potent in pigs. This may lead to decreased water reabsorption and a reduced ability to concentrate urine after xenotransplantation. |

| Erythropoietin (EPO) production | Pig EPO has a high degree of homology to human EPO, although it is not known if it can activate human EPO receptors. The anemia seen in in vivo models following xenotransplantation could be due to this physiologic difference, although it may be multifactorial. |

| Renal response to hormones | Pig kidney grafts have been shown to grow rapidly after xenotransplantation independent of rejection. This phenomenon is reduced by using kidneys from growth hormone receptor knock-out pigs. Pig kidneys are able to process human growth hormones, catecholamines, and prostaglandins. |

| Acid-base balance | Humans and pigs have comparable blood pH levels, but the composition of metabolites is different as pigs have higher bicarbonate and phosphate levels. While a pig kidney can excrete acid and reabsorb bicarbonate at acceptable rates, it may not excrete as much phosphate, which could lead to an anion-gap acidosis. |

| Calcium/phosphorus handling | Following renal xenotransplantation in NHPs, serum calcium levels rise to high normal values while phosphate levels drop. It remains to be seen how the pig graft will respond to human FGF-23, parathyroid hormone, or vitamin D. |

However, the inability of pig renin to cleave human angiotensinogen may be an important physiologic barrier to successful xenotransplantation. Baboons with life-supporting pig kidney grafts have been reported to experience episodes of hypovolemia, low blood pressures, and increased serum creatinine in the absence of rejection on biopsy, which correct following intravenous fluid administration.3 These baboons do not appear to generate an increased thirst response as their fluid intake is maintained at levels prior to transplant. An impaired renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is one explanation for these findings (see Section 2). Others include reduced response to primate antidiuretic hormone (ADH) on the pig kidney, altered urine concentration from anatomical differences in pig kidney nephron loops (see Section 3), or denervation resulting from bilateral native nephrectomies at the time of transplantation in NHPs.

NHPs have also been observed to be anemic after renal xenotransplantation which could be associated with immunosuppressive therapy, or the clinical state following transplant. However, porcine erythropoietin (EPO) may not be able to adequately stimulate the host bone marrow (see Section 4).

Anatomic Considerations

Pig and human kidneys share similar gross anatomic features and are of comparable sizes. The vascular configuration is similar with the vast majority of pigs having one renal artery and one renal vein per kidney.4–8 Ureteral anatomy is comparable as well.9 Both human and pig kidneys have a multi-papillary architecture with similar calyces and renal pelvis.10 In terms of intraparenchymal architecture, they have similar medullary and cortical structures.10,11

The nephron composition and distribution are similar, though there are fewer long nephron loops in pigs. The ratio of short-to-long loops is 85:15 in humans and 97:3 in pigs.12 Briefly, short-looped nephrons make a 180 degree bend in the outer medulla and long-looped nephrons bend deeper in the inner medulla and thus have greater capacity for concentrating the filtrate.11,12 In addition, pig kidneys have fewer nephrons than human kidneys, and excrete larger volumes of urine.13 This suggests that, overall, pig kidneys have a reduced ability to concentrate urine compared to human kidneys.

Both human and pig kidneys share a simple vasa recta structure, with alternating ascending and descending vascular bundles that surround the loop of Henle and contribute to the countercurrent exchange.10,11,14 Pig kidneys also demonstrate a structural difference where deeper cortical and medullary nephrons return and empty into collecting ducts near the superficial cortex, forming arcade structures not present in human kidneys. It has been proposed that because the pig collecting duct is more superficial, the action of ADH is different than in humans, although the clinical implications of this remain to be determined.9

Section 1: Global Function

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) remains the clinical standard in assessing kidney function.15 When measured in humans, baboons, and pigs, GFRs are similar, each near 130 mL/min per 70 kg.16. Renal blood flow, or how much blood the kidneys receive per minute, is similar between humans and pigs (both approximately 4ml/min/g of kidney).16,17 Pigs have a lower urine osmolality (1080 compared to 1160 mOsm/L in humans) which further support that pig kidneys have less concentrating ability than human kidneys.17

The amount of protein in the urine complements GFR as a biomarker of kidney function. While small amounts of uromodulin (e.g., 150 mg/day) are normally present in urine, the presence of urinary albumin signifies a structural or functional injury to the glomerular filtration barrier along with an overwhelmed capacity to reabsorb albumin in the proximal tubule. Piglets have baseline physiologic proteinuria, but adult pigs have comparable urine protein levels to humans.18–21 Proteinuria observed after allotransplantation is usually associated with a pathological state, including allograft rejection.22 Current experiments involving genetically-modified pig grafts with effective immunosuppressive regimens have not developed proteinuria.2,23,24 This supports the concept that proteinuria can be used as a marker of rejection in xenotransplantation.25 Proteinuira after xenotransplant can be tracked with relative ease using available assays.26

Opportunities for Exploration

The longevity of pig kidney grafts following transplantation remains unknown. Measuring global graft function over time is an important step in transitioning from primate to human recipients. There are multiple reports of NHPs with life-supporting pig kidney grafts surviving for >100 days with a normal serum creatinine, but the GFR has not been directly measured.1 Serum creatinine levels have many limitations in estimating GFR. Principal among the limitations is an insensitive estimate of higher GFRs. Due to the inverse association between serum creatinine levels and GFR, small changes in serum creatinine concentrations (e.g., <0.3 mg/dL) can represent large changes in GFR when baseline serum creatinine levels are low. Xenotransplantation experiments have been performed in NHPs with weights ranging from 7 to 13 kg and muscle masses similar to 5 year old children, where normal serum creatinine levels are low.

The gold standard measurement of GFR is a steady-state measurement of the urinary clearance of inulin. Markers used to estimate GFR (even in an allograft) are not as sensitive to changes in renal function when compared to inulin clearance.27,28 To our knowledge, no inulin clearance studies have been reported after pig-to-NHP kidney transplantation. Any method for measuring or even estimating GFR would need to be validated against the gold standard of classical urinary clearance.29–31

Changes in other markers of global renal function, including tubular secretion, could also be explored. It is important to predict how a pig kidney will process medications in a human recipient, and how this may change over time. In addition, defining normal levels of proteinuria following xenotransplantation would guide postoperative assessments of graft rejection.

Section 2: Sodium Handling

Regulation of electrolyte concentrations and plasma volume are central to the kidney’s role in maintaining homeostasis. Because sodium is the dominant extracellular cation and the primary contributor to plasma osmolality, its extracellular content determines plasma volume. Hormones released in hypovolemic states like angiotensin 2, aldosterone, and catecholamines act on the kidney to increase sodium reabsorption. Hormones released in hypervolemic states, like atrial natriuretic peptide, lead to natriuresis. Considerations of pig graft function include not only intrinsic salt handling along the nephron, but also the ability of the pig kidney graft to respond to physiologic changes in the hormonal regulation of sodium.

The human kidney must reabsorb ~99% of the sodium that has been filtered (see Figure 1). In euvolemic conditions, the proximal tubule reabsorbs 66% of the sodium; however, when hypovolemic, circulating angiotensin 2 and catecholamines increase proximal tubular sodium reabsorption up to 80%. A quarter of filtered sodium is reabsorbed in the thick ascending limb, and sodium reabsorption in this water-impermeable segment of the nephron is critical for generating the osmolar gradient needed to concentrate urine. ADH increases sodium reabsorption in the thick-ascending limb. In the distal convoluted tubule, 4-6% of the filtered sodium is reabsorbed, any decrease in sodium reabsorption here can affect downstream potassium secretion. For this reason, chronically high aldosterone levels upregulate sodium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule, in order to prevent excess urinary potassium losses. The collecting duct is the final nephron segment and accounts for 1-2% of filtered sodium reabsorption. The principal cell in the collecting duct is the main site of action for aldosterone, natriuretic peptides, and ADH.

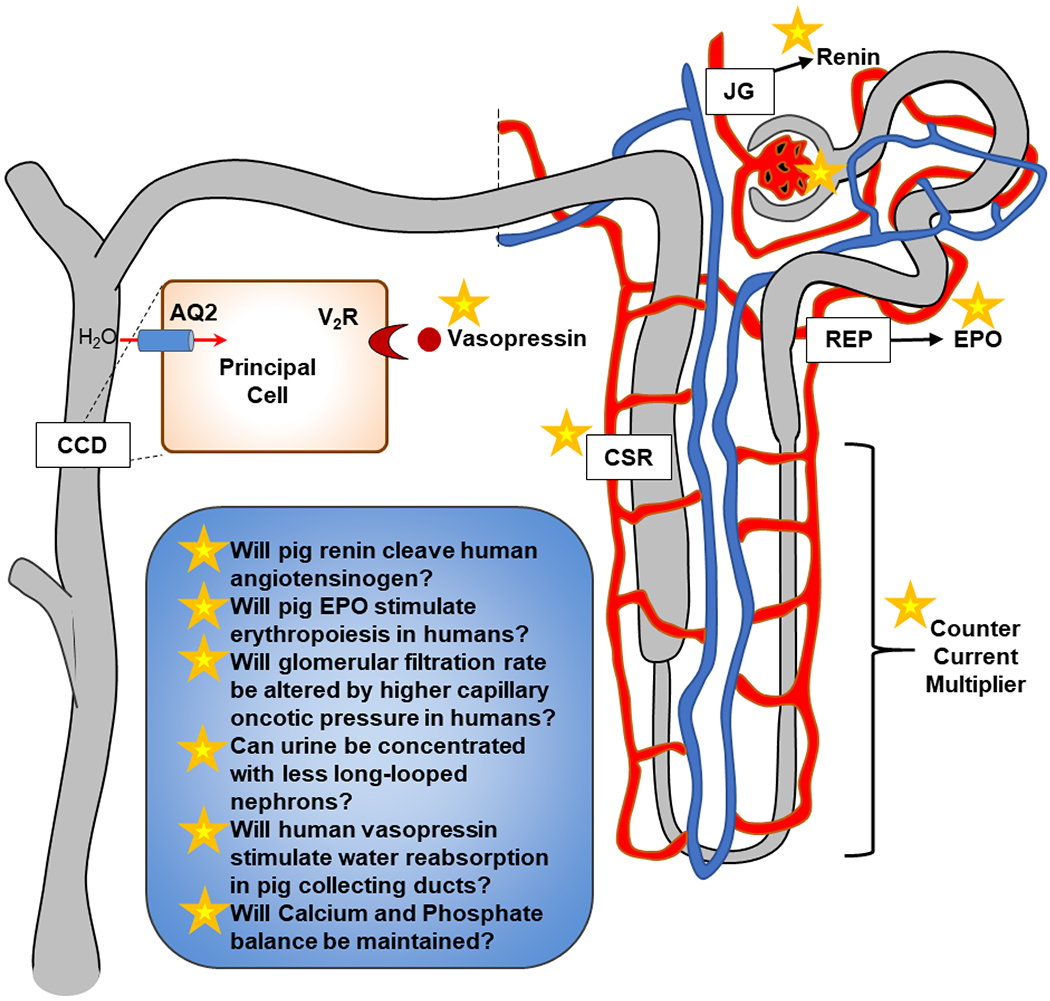

Figure 1: Potential Barriers to Pig Kidney Allograft Function.

JG, juxtaglomerular; REP, renal epo-producing cell; EPO, erythropoietin; AQ2, aquaporin 2; V2R, vasopressin (V2) receptor; CCD, cortical collecting duct; CSR, calcium-sensing receptor

While angiotensin 2, aldosterone, catecholamines (see Section 5), and natriuretic peptides are similar among mammals, small differences in their effects on sodium handling along the nephron can result in clinically relevant changes in homeostasis. Overall, similar serum electrolyte concentrations between humans and pigs, with the exception of a slightly higher serum potassium level in pigs (5.3 vs 4 mEq/L) (Table 1), are reassuring for xenotransplantation. Importantly, major electrolytes levels, such as sodium, potassium, and chloride, are comparable in baboons with pig kidneys to levels prior to transplant (Figure 2).

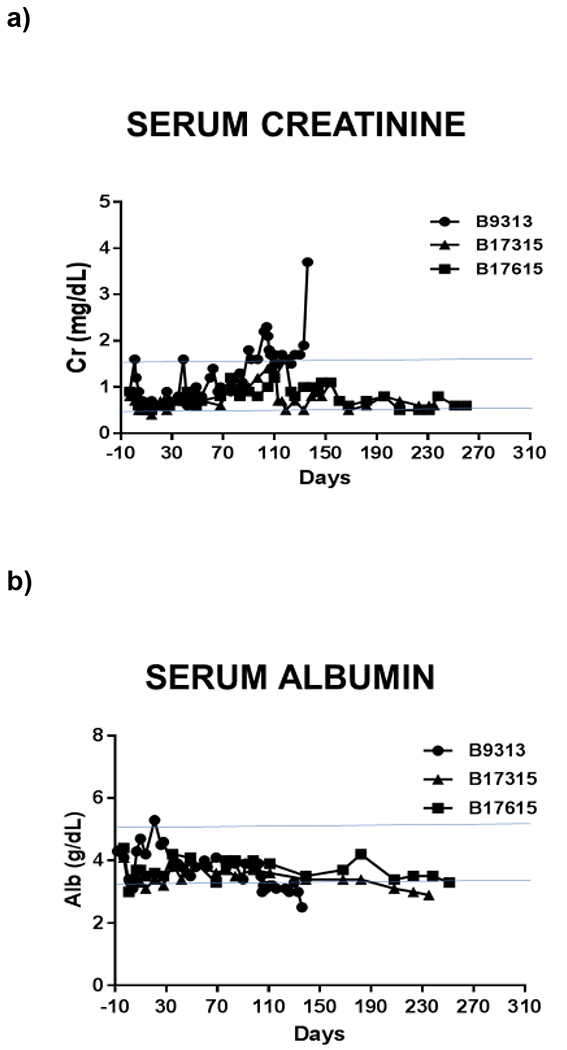

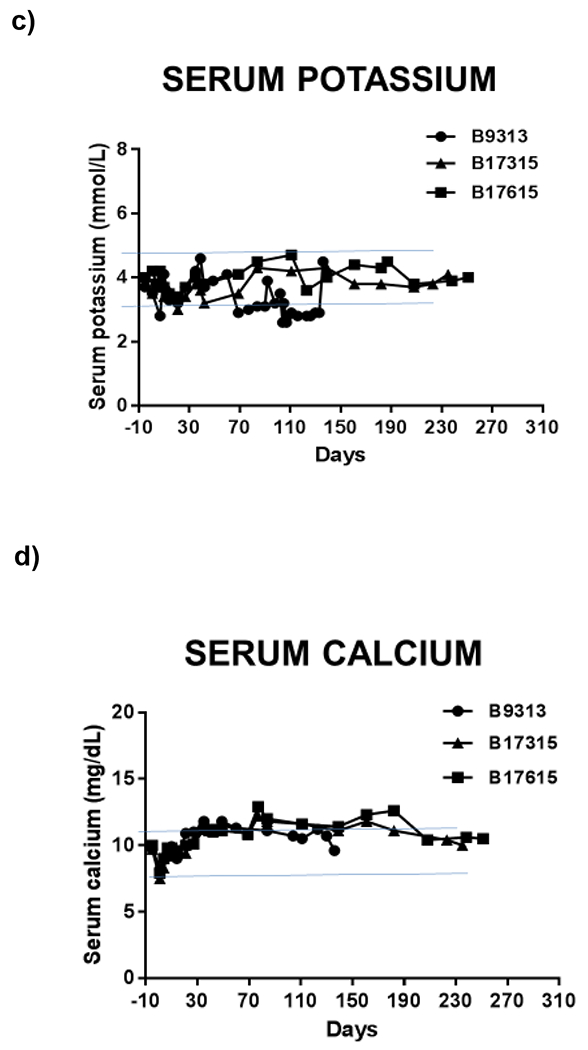

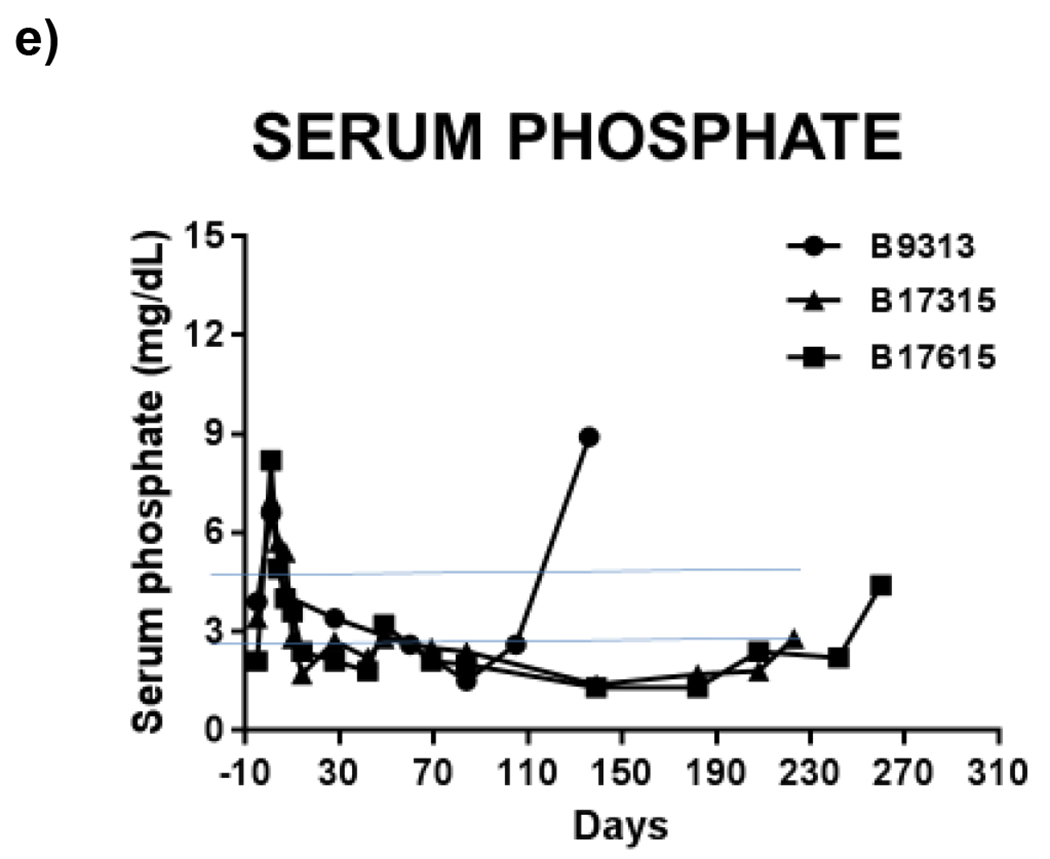

Figure 2: Serum (a) creatinine, (b) albumin, (c) potassium, (d) calcium normalize following renal xenotransplant in a pig-to-baboon model. Hypophosphatemia (e) is also seen following transplant in this model.

These are labeled relative to renal xenotransplantation. Horizontal blue lines represent normal ranges for baboons (Ekser 2012).81

Opportunities for Exploration

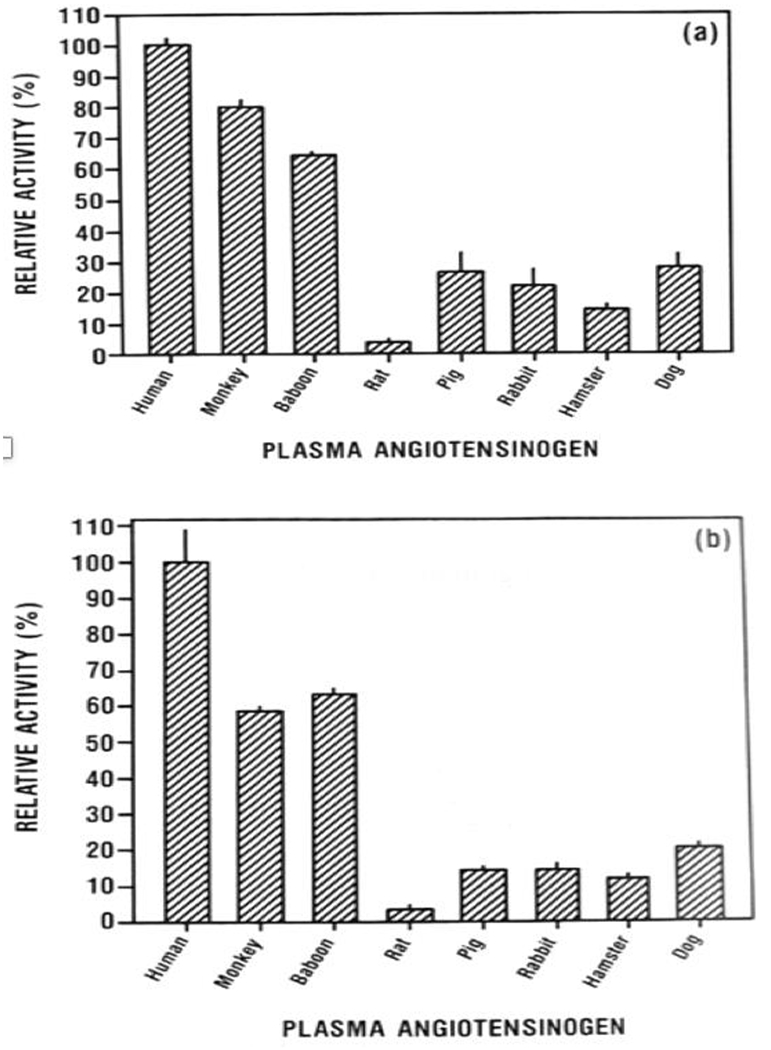

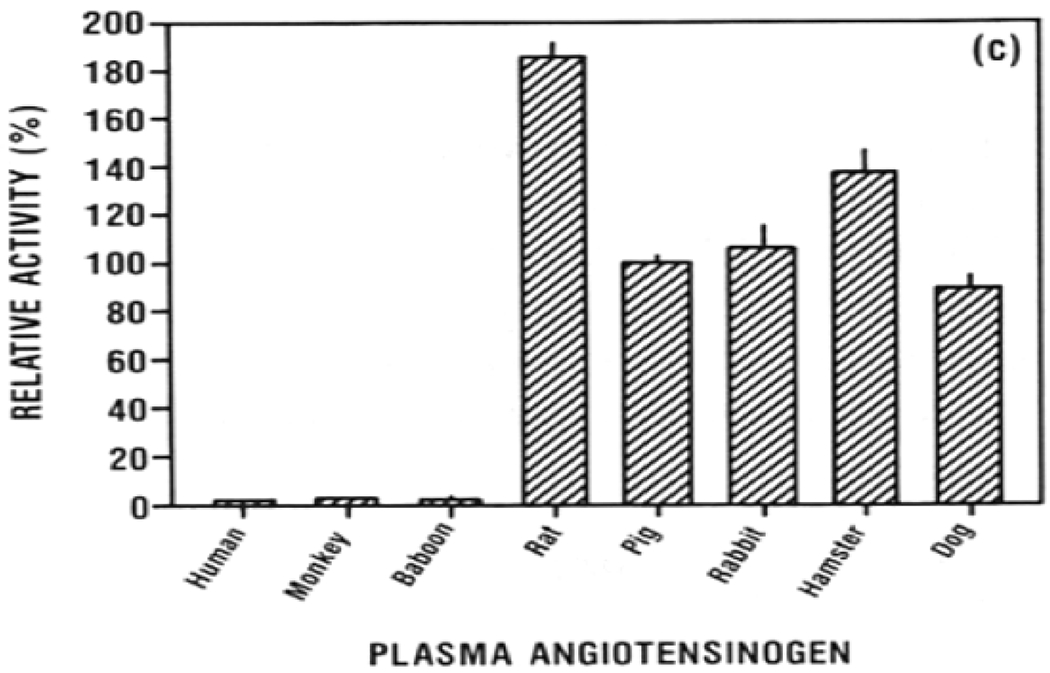

The mechanism behind electrolyte homeostasis in NHPs after xenotransplant is unclear, as the RAAS system may be compromised following transplantation. Plasma renin activity is similar in humans (0.75-4.49 ng/mL/h), baboons (male: 2.4-5.5 ng/mL/h; female: 5.4-14.0 ng/mL/h), and pigs (1.7-2.9 ng/mL/h).3 However, in vitro studies suggest that primate (including baboon and human) angiotensinogen is a poor substrate for porcine renin, given differences in specific key residues32–34 (Figure 3). It is therefore uncertain whether the renin produced in the pig graft will maintain the human RAAS system.

Figure 3: Relative hydrolysis activity of recombinant human renin (a), human kidney renin (b), and porcine kidney renin (c) on angiotensinogen from several different species.

Note that human renin is able to cleave pig angiotensinogen at a low rate but pig renin cleaves human and baboon angiotensinogen at an extremely low rate. This raises the question of whether the RAAS system is preserved following renal xenotransplantation. (Adapted from Evans 199034)

Native kidneys are rarely removed during kidney transplantation surgeries. Residual renin production from the native kidneys is possible, but renin secretion from end-stage kidneys is unlikely to meet physiologic demands, particularly if patients have been requiring dialysis for years. Renal blood flow decreases as kidneys atrophy.35,36

In vivo studies measuring components of the RAAS pathway in NHPs after kidney xenotransplantation would provide insight into porcine renin activity. One additional consideration is the capacity of a pig graft to produce its own angiotensinogen for cleavage. An intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been identified in humans. However, intrarenal RASs are likely modulatory and do not replace the systemic pathway.37 To the best of our knowledge, no in vivo studies have been reported in NHPs with pig kidney grafts that demonstrate the activity of porcine renin in NHPs. If porcine renin is found not to cleave human or NHP angiotensinogen at a clinically significant rate, consideration may need to be given to generating pigs genetically-engineered to express human renin. Decreased porcine renin activity in baboons may be a factor in the reported hypovolemic episodes described above.

Section 3: Water Handling

The kidneys maintain water homeostasis through the ADH system, thirst, and a renal architecture involving selective water permeability and counter-current loops of Henle and vasa recta. ADH is a hormone synthesized in the hypothalamus, and released from the posterior pituitary. Its renal effects are mediated through aquaporin and ADH 2 receptors, and serve to increase the volume of water that is reabsorbed from the glomerular filtrate. ADH is a highly-conserved molecule among primates, with humans having the same arginine ADH peptide structure as most NHPs.38 Pigs, however, produce ADH with lysine in the place of arginine.39 Pig kidneys exposed to arginine ADH still produce an adequate antidiuretic effect, but show decreased urine-concentrating ability.39 When infused into pigs, arginine ADH increases renal blood flow.40 Aquaporin and ADH 2 receptor expression increase with fetal age resulting in the increased urinary concentration capabilities of older pigs which may help determine the optimal age at which pig kidneys should be transplanted.41

ADH also serves to increase the concentration of urea and sodium in the renal medulla by increasing expression of urea transporters and activity of the sodium-potassium-2 chloride cotransporter in the thick ascending limb.42 The increase in medullary solute concentration contributes to the countercurrent exchange, and allows for further urine concentration. If primate arginine ADH generates a less robust response in the pig kidney, then this would decrease the ability of the graft to reabsorb water. Clinically, reduced response to ADH in a pig graft would present as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with associated increased thirst and polyuria.

Section 4: Erythropoietin Production

The kidney performs endocrine functions through the production of renin (Section 2), activation of vitamin D (Section 7), and production of erythropoietin (EPO). Although these pathways are generally well-conserved among mammals, species-specific differences, especially between pig and primate, may affect physiology. EPO is a hormone that stimulates the bone marrow to produce red blood cells (RBCs).43 The main site of EPO production in humans shifts from the liver during fetal development to the kidney after birth. In healthy human adults, renal production of EPO accounts for >90% of circulating EPO.43 While hepatic synthesis of EPO can increase in states of renal failure, this increase is not sufficient to prevent anemia.44 Several groups have reported that baboons develop anemia following pig kidney xenotransplantation, which is treated with exogenous EPO.23,45,46 However, whether the anemia results from the suppressive effect of immunosuppressive therapy on the bone marrow and/or frequent blood draws, or is a direct result of the inability of pig EPO to maintain erythropoiesis, remains uncertain. Despite the fact that porcine EPO has a high degree of homology to human EPO, the need for supplementation in pig-to-NHP renal transplant models suggests that porcine EPO does not adequately stimulate human or NHP erythrogenesis.23,47

Opportunities for Exploration

The mechanism behind the anemia seen in pig-to-NHP models of kidney transplantation is not clear, especially as the NHPs are not anemic prior to transplantation (as are most patients with end-stage kidney disease). We could find no in vitro study that addressed whether porcine EPO could directly activate NHP or human EPO receptors. Nor could we find an in vivo model or clinical study where porcine-derived EPO was used. There is some in vitro evidence to suggest that porcine hematologic growth factors would stimulate a response in human hematopoietic progenitor cells, but robust evidence is lacking.48 Next steps involve in vivo studies aimed at identifying the physiologic compatibility of pig EPO to stimulate primate red blood cell production in the setting of anemia associated with frequent blood draws, immunosuppressive therapy, and renal denervation.

Section 5: Kidney’s Response to Hormones

The kidney is involved in many hormonal pathways that are generally preserved across mammalian species. Individual characteristics of the growth hormone, catecholamine, and prostaglandin pathways as they apply to xenotransplantation are discussed individually below.

Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I

Growth hormone plays an important role in the development and function of the kidney.49 Growth hormone receptors (GHRs) are expressed throughout the nephron. Greater numbers of receptors are present in the proximal segments, thus allowing growth hormone to directly affect electrolyte and mineral reabsorption.50 However, most of the effects of growth hormone on the kidney are mediated through insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) which can increase GFR and renal plasma flow as part of a growth hormone-IGF-1 axis.50–52

The GHR displays directional species-specificity as human GHRs can only be activated by human and NHP (rhesus monkey) growth hormone. However, human growth hormone can activate non-primate GHRs, including pig GHRs.53,54 Pigs that receive exogenous human IGF-1 still experience systemic effects, such as hypoglycemia, and pigs that receive exogenous human growth hormone release-factor still produce porcine growth hormone, indicating that human factors can still produce a response in pigs.55,56

Patients with chronic kidney disease have elevated levels of growth hormone, which may be due to growth hormone insensitivity, and decreased clearance.51,52 This baseline increase in circulating growth hormone levels in the recipient is not seen in pig-to-NHP studies, as the selected NHPs do not have underlying kidney disease. As such, it is unclear how the baseline elevated growth hormone levels in patients with end-stage kidney disease would affect a pig graft.

Opportunities for Exploration

There have been several reports of significant graft hypertrophy occurring in pig-to-NHP transplant models without evidence of rejection.57–59 One group has reported this growth to be detrimental to the graft, either by development of a compartment-syndrome compression of the graft or from cortical ischemia.58,59 The mechanism for growth after transplant is not fully understood, but multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors may play roles.59

A GHR-knockout (GHRKO) pig line has been created.60 These pigs have elevated growth hormone levels, decreased IGF-1 levels, and decreased renal mass.60 In addition, GFR and renal plasma flow are reduced in growth hormone-deficient states due to increased renal arteriolar resistance and low ultrafiltration coefficients which has been reviewed elsewhere.61,62

Catecholamines

Catecholamines, including epinephrine and norepinephrine, have wide-ranging systemic effects on the body through activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Most catecholamines circulate in sulfoconjugated forms, which are inactive versions of the ‘free form’.63 The sulfoconjugated forms are metabolized slowly, and are eliminated in the urine.64 Patients with renal failure have increased levels of free and conjugated catecholamines, but these compounds can be removed by dialysis, or a functioning kidney graft.64–66

In general, humans have higher levels of free catecholamines than pigs, and a higher percentage of conjugated catecholamines.67 However, pig kidneys can process and eliminate epinephrine and norepinephrine at acceptable rates.68 In addition to considering urinary clearance of catecholamines and their metabolites, the action of circulating catecholamines on a pig allograft is not fully known. In humans, high catecholamine levels increase renin release from juxtaglomerular cells, vasoconstrict intrarenal small arteries upstream of the glomerular capillary bed, and enhance sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule by increasing the activity of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger. In vivo studies may be able to identify differences in catecholamine levels between genetically-modified organ-source pigs and NHPs prior to and following xenotransplantation, as well as identify a preserved renal response to hypovolemia.

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are a class of lipid molecules that have varied effects based on the target tissue receptors. The kidney produces prostaglandin E2, F2, D2, I2 (prostacyclin), and thromboxane A2.69 Prostaglandin effects are predominately para-cellular, acting on cells very close to those that synthesize the prostaglandin. Classic renal effects include (i) maintaining afferent arteriolar vasodilation in under-perfused states (via prostacyclin and PGE2), (ii) modulation of renin release (PGE2), and (iii) antagonism of ADH (PGE2).70 After clinical renal allotransplantation, serum PGE2 increased in the setting of increased arginine ADH, which may have been associated with decreased responsiveness of arginine ADH in the collecting ducts.71,72 A PGE2 increase may also be related to kidney graft compensation with associated higher renal plasma flow after kidney transplantation.

PGE2 mediates local renal effects through four different E prostanoid cell-surface receptors (EP1-4) which are expressed in both human and pig kidneys.73 Humans and pigs also have the same enzyme that processes PGE2 (prostaglandin 9-ketoreductase).74 While pig kidneys can produce intrinsic PGE2, it is likely that pig kidneys will also process human PGE2.

Section 6: Acid-Base Balance

In the typical Western diet with animal protein intake, the human kidneys normally excrete 1mEq per body weight in kg of acid each day. The urinary acid excretion is accomplished through a combination of ammonium excretion and titratable acids, which consists predominately of phosphate excretion.75 In pigs, serum bicarbonate levels are higher than in humans, though circulating blood phosphate levels are also higher in pigs than humans, and so the blood pH is similar between humans and pigs.76 (Table 1) Pig kidneys excrete acid with the ability to reabsorb all of the filtered bicarbonate. The primary difference is in the homeostatic balance of titratable acids, like serum phosphates, and possibly sulfates. A pig graft may not excrete as much phosphate as a human allograft, which could lead to an anion-gap acidosis, as well as an imbalance of hormones related to long-term bone health, like vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and fibroblast growth factor 23.

Section 7: Calcium and Phosphorus Handling

A dynamic relationship between the kidneys and bones determines the homeostasis for calcium and phosphorus. This relationship is under hormonal regulation and involves calcium-sensing receptors both inside and outside the kidneys, and phosphorus detection outside the kidneys. The parathyroid hormone (PTH) mobilizes calcium from bone in order to maintain a stable blood calcium level. With the release of calcium from bone, phosphorus is also released. Therefore, PTH acts on the kidney to reabsorb calcium and excrete phosphorus. In order to restore bone calcium and phosphorus, PTH also activates 1-alpha-hydroxylase in the kidney, which converts vitamin D to its active form. The active form of vitamin D results in increased intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. When serum phosphorus levels are high, fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) is released from the bone. FGF-23 is a potent phosphaturic hormone, resulting in increased urinary excretion of phosphate, but also inhibition of 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which also prevents Vitamin D-related intestinal absorption of phosphorus. In addition, the kidney directly senses serum calcium levels through calcium-sensing receptors on the basolateral surface of the thick ascending limb.

This interdependent hormonal relationship between bone, parathyroid gland, and kidney introduces many potential interruptions in normal physiology following pig graft transplantation. For example, will the pig graft respond similarly to signaling from FGF-23, PTH, and Vitamin D? Will pig graft calcium-sensing receptors have similar responses to changes in serum calcium levels? Serum calcium and phosphate levels are higher in pigs then humans, suggesting that differences do exist in homeostasis. Hypophosphatemia has been seen in baboons after pig graft xenotransplantation.2 (Figure 2)

Additional considerations:

Uric Acid

In humans, uric acid is produced as an end-product of purine metabolism, but in lower mammals it is further oxidized by urate oxidase, an enzyme produced by the liver.77 As humans cannot oxidize uric acid, it circulates in the blood in the form of urate and is excreted by the kidney. Pig kidneys have been shown to eliminate uric acid both by filtration and secretion, and so hyperuricemia is not anticipated to be a major problem after porcine renal xenotransplantation.78

Conclusions

Differences exist between pig and human physiology. The potential for a pig kidney to fail to activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, or to not fully respond to anti-diuretic hormone, or to disturb the phosphate balance in a human recipient presents potential barriers to xenotransplantation. However, each of these barriers can be overcome through early identification and management following transplant. We have outlined the major considerations in making a pig kidney compatible with a human, but we remain humble and excited about the unknown in this new era of medicine.

Acknowledgements

Work on xenotransplantation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham is supported in part by NIH NIAID U19 grant AI090959 and in part by Department of Defense grant WB1XWH-20-1-0559. The baboons used in our studies are from the Michale E. Keeling Center, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop, TX, which is supported by NIH grant P40 OD24628-01.

Abbreviations

- ADH

Antidiuretic Hormone

- EPO

Erythropoietin

- ESRD

End-stage Renal Disease

- GFR

Glomerular Filtration Rate

- GH

Growth Hormone

- GHR

Growth Hormone Receptor

- GHRKO

Growth Hormone Receptor Knock Out

- IGF-1

Insulin-like Growth Factor 1

- NHP

Non-human Primate

- RAAS

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

- RAS

Renin-Angiotensin System

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Iwase H, Liu H, Wijkstrom M, et al. Pig kidney graft survival in a baboon for 136 days : longest life-supporting organ graft survival to date. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(4):302–309. doi: 10.1111/xen.12174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwase H, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, et al. Immunological and physiological observations in baboons with life- - supporting genetically engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(2):1–13. doi: 10.1111/xen.12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwase H, Yamamoto T, Cooper DKC. Episodes of hypovolemia/dehydration in baboons with pig kidney transplants: A new syndrome of clinical importance? Xenotransplantation. 2019;26(2):e12472. doi: 10.1111/xen.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez FA, Ballesteros LE, Estupinan HY. Morphological Characterization of the Renal Arteries in the Pig. Comparative Analysis with the Human. Int J Morphol. 2017;35(1):319–324. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaoka A, Koshimizu M, Nakamura S, Matsumura K. Quantitative angiographic anatomy of the renal arteries and adjacent aorta in the swine for preclinical studies of intravascular catheterization devices. Exp Anim. 2018;67(2):291–299. doi: 10.1538/expanim.17-0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira-Sampaio MA, Favorito LA, Sampaio FJB. Pig kidney: Anatomical relationships between the intrarenal arteries and the kidney collecting system. Applied study for urological research and surgical training. J Urol. 2004;172(5 I):2077–2081. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138085.19352.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagetti Filho HJS, Pereira-Sampaio MA, Favorito LA, Sampaio FJB. Pig Kidney: Anatomical Relationships Between the Renal Venous Arrangement and the Kidney Collecting System. J Urol. 2008;179(4):1627–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szymanski J, Polguj M, Topol M, Oszukowski P. Anatomy of renal veins in swine. Med Weter Med Pract. 2015;71(12):773–777. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf JS, Humphrey PA, Rayala HJ, Gardner SM, Mackey RB, Clayman RV. Comparative ureteral microanatomy. J Endourol. 1996;10(6):527–531. doi: 10.1089/end.1996.10.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfeiffer EW. Comparative anatomical observations of the mammalian renal pelvis and medulla. J Anat. 1968;102(2):321–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawata CM, Pannabecker TL. Mammalian urine concentration: a review of renal medullary architecture and membrane transporters. J Comp Physiol B Biochem Syst Environ Physiol. 2018;188(6):899–918. doi: 10.1007/s00360-018-1164-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaissling B, Kriz W. Morphology of the Loop of Henle, Distal Tubule, and Collecting Duct. In: Comprehensive Physiology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011:68–83. doi: 10.1002/cphy.cp080103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thein E, Hammer C. Physiologic barriers to xenotransplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2004;9(2):186–189. doi: 10.1097/01.mot.0000126087.48709.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriz W Structural organization of the renal medulla: comparative and functional aspects. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol. 1981;241(1):R3–R16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.1.R3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz GJ, Furth SL. Glomerular filtration rate measurement and estimation in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1839–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0358-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachs DH. The pig as a potential xenograft donor. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;43(1-3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90135-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkman RL. Of swine and men: organ physiology in different species. In: Xenograft. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier; 1989:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radák Z, Ogonovszky H, Dubecz J, et al. Super-marathon race increases serum and urinary nitrotyrosine and carbonyl levels. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33(8):726–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SK, Seo MH, Ryoo J-H, et al. Urinary albumin excretion within the normal range predicts the development of diabetes in Korean men. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(2):427–433. doi: 10.1016/J.DIABRES.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chade AR, Williams ML, Engel J, Guise E, Harvey TW. A translational model of chronic kidney disease in swine. Am J Physiol Physiol. 2018;315(2):F364–F373. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00063.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wah Loh S, Bourne FJ, Curtis J. Urine protein levels in the pig. Anim Sci. 1972;15(3):273–283. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100011533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaled Shamseddin M, Knoll GA. Posttransplantation Proteinuria: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1786–1793. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01310211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soin B, Smith KG, Zaidi A, et al. Physiological Aspects of Pig-to-Primate Renal Xenotransplantation. Vol 60.; 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00973.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwase H, Klein EC, Cooper DK. Physiologic Aspects of Pig Kidney Transplantation in Nonhuman Primates. Comp Med. 2018;68(5):332–340. doi: 10.30802/AALAS-CM-17-000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah JA, Lanaspa MA, Tanabe T, Watanabe H, Johnson RJ, Yamada K. Review Article Remaining Physiological Barriers in Porcine Kidney Xenotransplantation : Potential Pathways behind Proteinuria as well as Factors Related to Growth Discrepancies following Pig-to-Kidney Xenotransplantation. 2018;2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/6413012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pintore L, Paltrinieri S, Vadori M, et al. Clinicopathological findings in non-human primate recipients of porcine renal xenografts : quantitative and qualitative evaluation of proteinuria. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20(6):449–457. doi: 10.1111/xen.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariat C, Alamartine E, Barthelemy J-C, et al. Assessing renal graft function in clinical trials: Can tests predicting glomerular filtration rate substitute for a reference method? Kidney Int. 2004;65(1):289–297. doi: 10.1111/J.1523-1755.2004.00350.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos J, Martins LS. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in kidney transplantation: Still searching for the best marker. World J Nephrol. 2015;4(3):345–353. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v4.i3.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Acker BAC, Koomen GCM, Arisz L. Drawbacks of the constant-infusion technique for measurement of renal function. Am J Physiol - Ren Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1995;268(4 37-4). doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.4.f543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Florijn KW, Barendregt JNM, Lentjes EGWM, et al. Glomerular filtration rate measurement by “single-shot” injection of inulin. Kidney Int. 1994;46(1):252–259. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orlando R, Floreani M, Padrini R, Palatini P. Determination of inulin clearance by bolus intravenous injection in healthy subjects and ascitic patients: Equivalence of systemic and renal clearances as glomerular filtration markers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(6):605–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00824.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen S, Hirawawa K, Smeby RR, Bumpus FM. Measurement of plasma renin substrate using homologous and heterologous renin. Am J Physiol. 1971;221(5):1476–1480. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.5.1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W, Liang TC. Substrate Specificity of Porcine Renin: P1′, P1, and P3 Residues of Renin Substrates Are Crucial for Activity. Biochemistry. 1994;33(48):14636–14641. doi: 10.1021/bi00252a032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans DB, Cornette JC, Sawyer TK, Staples DJ, de Vaux AE, Sharma SK. Substrate specificity and inhibitor structure-activity relationships of recombinant human renin: implications in the in vivo evaluation of renin inhibitors. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1990;12(2):161–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-8744.1990.tb00089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li LP, Tan H, Thacker JM, et al. Evaluation of Renal Blood Flow in Chronic Kidney Disease Using Arterial Spin Labeling Perfusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khatir DS, Pedersen M, Jespersen B, Buus NH. Evaluation of Renal Blood Flow and Oxygenation in CKD Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):402–411. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell DJ. Clinical Relevance of Local Renin Angiotensin Systems. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5(JUL). doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallis M Molecular evolution of the neurohypophysial hormone precursors in mammals: Comparative genomics reveals novel mammalian oxytocin and vasopressin analogues. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;179(2):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munsick RA, Sawyer WH, Dyke Van HB. The antidiuretic potency of arginine and lysine vasopressins in the pig with observations on porcine renal function. Endocrinology. 1958;63(5):688–693. doi: 10.1210/endo-63-5-688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voelckel WG, Raedler C, Wenzel V, et al. Arginine vasopressin, but not epinephrine, improves survival in uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock after liver trauma in pigs*. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1160–1165. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000060014.75282.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing L, Nørregaard R. Influence of sex on aquaporin 1-4 and vasopressin V2 receptor expression in the pig kidney during development. Pediatr Res. 2016;80(3):452–459. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sands JM, Layton HE. Advances in understanding the urine-concentrating mechanism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:387–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Risør LM, Fenger M, Olsen NV., Møller S. Hepatic erythropoietin response in cirrhosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2016;76(3):234–239. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2015.1137351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lönnberg M, Garle M, Lönnberg L, Birgegård G. Patients with anaemia can shift from kidney to liver production of erythropoietin as shown by glycoform analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;81-82:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams AB, Kim SC, Martens GR, et al. Xenoantigen deletion and chemical immunosuppression can prolong renal xenograft survival. Ann Surg. 2018;268(4):564–573. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cozzi E, Vial C, Ostlie D, et al. Maintenance triple immunosuppression with cyclosporin A, mycophenolate sodium and steroids allows prolonged survival of primate recipients of hDAF porcine renal xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10(4):300–310. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.02014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wen D, Boissel JPR, Tracy TE, et al. Erythropoietin structure-function relationships: High degree of sequence homology among mammals. Blood. 1993;82(5):1507–1516. doi: 10.1182/blood.v82.5.1507.bloodjournal8251507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis TA, Black AT, Kidwell WR, Lee KP. Conditioned medium from primary porcine endothelial cells alone promotes the growth of primitive human haematopoietic progenitor cells with a high replating potential: Evidence for a novel early haematopoietic activity. Cytokine. 1997;9(4):263–275. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammerman MR, Miller SB. Effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I on renal growth and function. J Pediatr. 1997;131(1 II SUPPL.):7–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamenický P, Mazziotti G, Lombès M, Giustina A, Chanson P. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, and the kidney: Pathophysiological and clinical implications. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(2):234–281. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahesh S, Kaskel F. Growth hormone axis in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(1):41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0527-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabkin R, Schaefer F. New concepts: growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I and the kidney. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14(4):270–276. doi: 10.1016/J.GHIR.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu J-C, Makova KD, Adkins RM, Gibson S, Li W-H. Episodic Evolution of Growth Hormone in Primates and Emergence of the Species Specificity of Human Growth Hormone Receptor. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18(6):945–953. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Souza SC, Frick GP, Wang X, Kopchick JJ, Lobo RB, Goodman HM. A single arginine residue determines species specificity of the human growth hormone receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(4):959–963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walton PE, Gopinath R, Burleigh BD, Etherton TD. Administration of Recombinant Human Insulin-Like Growth Factor I to Pigs: Determination of Circulating Half-Lives and Chomatographic Profiles. Horm Res. 1989;31(3):138–142. doi: 10.1159/000181103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Etherton TD, Wiggins JP, Chung CS, Evock CM, Rebhun JF, Walton PE. Stimulation of Pig Growth Performance by Porcine Growth Hormone and Growth Hormone-Releasing Factor. J Anim Sci. 1986;63(5):1389–1399. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.6351389x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soin B, Ostlie D, Cozzi E, et al. Growth of porcine kidneys in their native and xenograft environment. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7(2):96–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah JA, Tanabe T, Yamada K. Role of Intrinsic Factors in the Growth of Transplanted Organs Following Transplantation. J Immunobiol. 2017;02(02). doi: 10.4172/2476-1966.1000122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanabe T, Watanabe H, Shah JA, et al. Role of intrinsic (graft) vs. extrinsic (host) factors in the growth of transplanted organs following allogeneic and xenogeneic transplantation HHS Public Access. Am J Transpl. 2017;17(7):1778–1790. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hinrichs A, Kessler B, Kurome M, et al. Growth hormone receptor-deficient pigs resemble the pathophysiology of human Laron syndrome and reveal altered activation of signaling cascades in the liver. Mol Metab. 2018;11(2018):113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirschberg R, Kopple JD. Effects of growth hormone and IGF-I on renal function. Kidney Int Suppl. 1989;27(1 II SUPPL.):S20–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwase H, Ball S, Adams K, Eyestone W, Walters A, Cooper DKC. Growth hormone receptor knockout: Relevance to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2021;28(2):e12652. doi: 10.1111/xen.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers PJ, Tyce GM, Weinshilboum RM, O’connor DT, Bailey KR, Bove AA. Catecholamine Metabolic Pathways and Exercise Training Plasma and Urine Catecholamines, Metabolic Enzymes, and Chromogranin-A. http://ahajournals.org. Accessed September 14, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Eisenhofer G, Huysmans F, Pacak K, Walther MM, Sweep FCGJ, Lenders JWM. Plasma metanephrines in renal failure. Kidney Int. 2005;67(2):668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cuche JL, Prinseau J, Selz F, Ruget G, Baglin A. Plasma free, sulfo- and glucuro-conjugated catecholamines in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 1986;30(4):566–572. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Musso NS, Deferrari G, Pende A, et al. Free and Sulfoconjugated Catecholamines in Renal Patients.Pdf. Vol 51. Nephron; 1989:344–349. doi: 10.1159/000185320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dousa MK, Tyce GM. Free and conjugated catecholamine pig human.pdf. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988;188(4):427–434. doi: 10.3181/00379727-188-42755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Link L, Weidmann P, Probst P, Futterlieb A. Pig renal handling of epinephrine and norepinephrine.pdf. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1985;405(1):66–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00591099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lote CJ. Renal Prostaglandins and Sodium Excretion. Q J Exp Physiol. 1982;67(3):377–385. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1982.sp002652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fejes Toth G, Magyar A, Walter J. Renal response to vasopressin after inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Am J Physiol. 1977;232(5). doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1977.232.5.f416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pedersen EB, Christensen P, Danielsen H, et al. Relationship between urinary prostaglandin E 2 and F 2α excretion and plasma arginine vasopressin during renal concentrating and diluting tests in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Invest. 1987;17(5):429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1987.tb01138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.El-Sharabasy MMH, El-Naggar MNM. Prostaglandin E2 in Renal Transplant Recipients. Vol 48. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1991:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF02550640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harner A, Wang Y, Fang X, et al. Differential Expression of Prostaglandin E2 Receptors in Porcine Kidney Transplants. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(6):2124–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schieber A, Frank RW, Ghisla S. Purification and properties of prostaglandin 9-ketoreductase from pig and human kidney. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206(2):491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee Hamm L, Nakhoul N, Hering-Smith KS. Acid-base homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2232–2242. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07400715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hannon JP, Bossone CA, Wade CE. Normal physiological values for conscious pigs used in biomedical research. Lab Anim Sci. 1990;40(3):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oda M, Satta Y, Takenaka O, Takahata N. Loss of urate oxidase activity in hominoids and its evolutionary implications. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(5):640–653. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simmonds HA, Hatfield PJ, Cameron JS, Cadenhead A. Uric acid excretion by the pig kidney. Am J Physiol. 1976;230(6):1654–1661. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.6.1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Unger V, Grosse-Siestrup C, Fehrenberg C, Fischer A, Meissler M, Groneberg DA. Reference values and physiological characterization of a specific isolated pig kidney perfusion model. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2007;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-2-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thomson SE, McLennan SV., Kirwan PD, et al. Renal connective tissue growth factor correlates with glomerular basement membrane thickness and prospective albuminuria in a non-human primate model of diabetes: possible predictive marker for incipient diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22(4):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ekser B, Bianchi J, Ball S, et al. Comparison of hematologic, biochemical, and coagulation parameters in α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs, wild-type pigs, and four primate species. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19(6):342–354. doi: 10.1111/xen.12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Klem TB, Bleken E, Morberg H, Thoresen SI, Framstad T. Hematologic and biochemical reference intervals for Norwegian crossbreed grower pigs. Vet Clin Pathol. 2010;39(2):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2009.00199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]