Abstract

Adaptive immune components are thought to exert nonoverlapping roles in antimicrobial host defense, with antibodies targeting pathogens in the extracellular environment and T cells eliminating infection inside cells1,2. Reliance on antibodies for vertically transferred immunity from mothers to babies may explain neonatal susceptibility to intracellular infections3,4. Here we show pregnancy-induced post-translational antibody modification enables protection against the prototypical intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes (Lm). Infection susceptibility was overturned in neonatal mice born to preconceptually primed mothers possessing Lm-specific IgG or upon passive transfer of antibodies from primed pregnant, but not virgin, mice. While maternal B cells were essential for producing IgG that mediate vertically transferred protection, they were dispensable for antibody acquisition of protective function, which instead required sialic acid acetyl esterase (SIAE)5 to deacetylate terminal sialic acid residues on IgG variable region N-linked glycans. Deacetylated Lm-specific IgG protected neonates via the sialic acid receptor CD226,7, which suppressed B cell IL-10 production to unleash antibody-mediated protection. Consideration of the maternal-fetal dyad as a joined immunological unit unveils newfound protective roles for antibodies against intracellular infection and fine-tuned adaptations to enhance host defense during pregnancy and early life.

Infection remains a leading cause of neonatal mortality8. While antibodies broadly defend against infection, they are thought to offer limited protection against pathogens residing inside cells, which are primarily targeted by T cells1,2. Division of labor between adaptive immune components may explain why newborn babies that rely on vertically transferred maternal antibodies are especially susceptible to intracellular infections4. The intracellular niche is exploited by many pathogens that cause perinatal infection including the Gram-positive bacterium Lm which rapidly gains access to the cell cytoplasm using the pore-forming toxin listerolysin O (LLO), thereafter spreading from the cytoplasm of one cell to another via ActA-mediated actin polymerization9,10.

Vertically transferred immunity primed by natural infection, vaccination, or commensal colonization of mothers dictates the adaptive immune repertoire of neonates8,11. Inadequate acquisition of protective maternal antibodies in premature or formula-fed infants increases infection risk12. However, since protective immunity against Lm and other intracellular pathogens has primarily been defined using passive transfer to and from adult recipients13–15, relevance to vertically transferred protection of neonates remains uncertain. Shared susceptibility between human babies and neonatal mice to Lm infection was exploited to probe how changes unique to the maternal-fetal dyad control immunity against intracellular infection.

Pregnancy Enables Antibody Protection

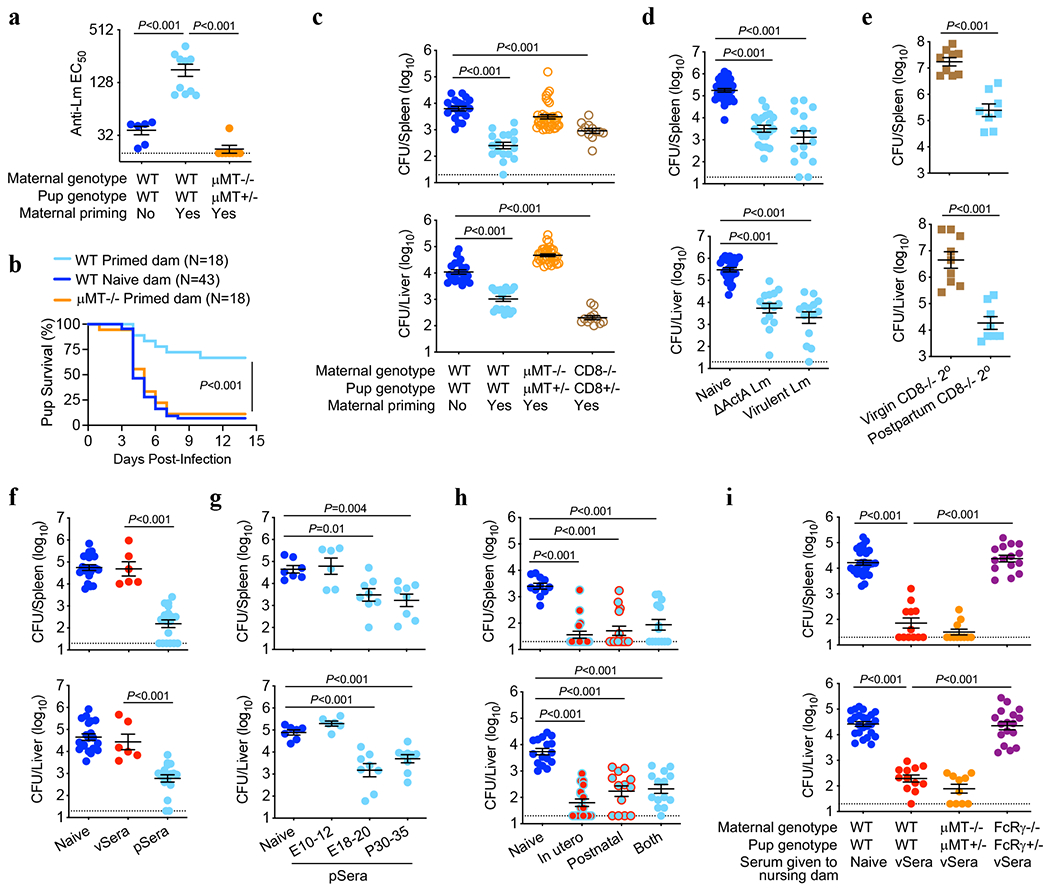

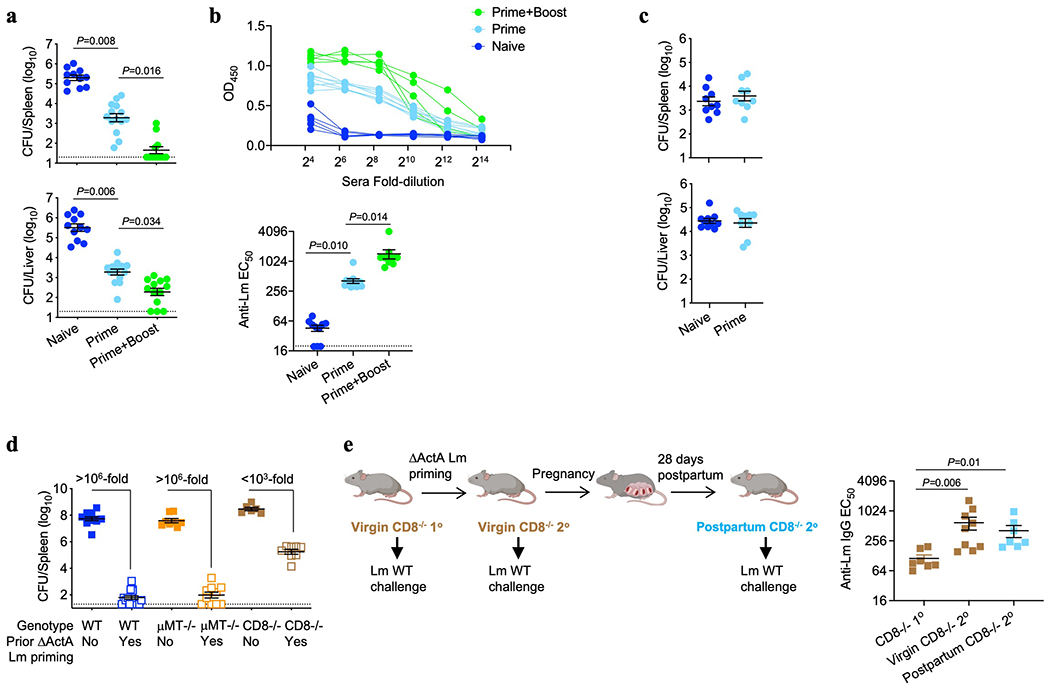

To investigate vertically transferred immunity against intracellular infection, susceptibility of neonatal mice born to preconceptually primed Lm immune mothers was evaluated. To eliminate the possibility of vertically transferred infection, attenuated ΔActA Lm, which is rapidly cleared yet retains immunogenicity even in immunocompromised mice9,10, was used to prime virgin female mice. Upon virulent Lm infection, neonatal mice born to primed mothers, compared with controls born to naive mothers, possessed elevated anti-Lm IgG titers that paralleled enhanced survival and significantly reduced bacterial burdens in the spleen and liver (Fig. 1a–c). Analogous experiments evaluating pups born to B cell-deficient (μMT−/−) or CD8 T cell deficient (CD8−/−) primed mothers revealed a surprising requirement for maternal B cells, but not CD8 cells, in vertically transferred immunity against Lm infection (Fig. 1a–c). WT males sired pregnancy generating phenotypically WT offspring (μMT+/− and CD8+/−), excluding susceptibility differences from neonatal B or T cell deficiency. Resistance to Lm infection was enhanced in pups possessing higher titer anti-Lm IgG born to boosted mothers (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Vertically transferred immunity also occurred with maternal preconceptual virulent Lm infection (Fig. 1d) and was specific to Lm since neonatal mice born to ΔActA Lm-primed dams showed equal susceptibility to the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (Extended data Fig. 1c). Therefore, maternal B cells are critical mediators of vertically transferred immunity extending to intracellular infection.

Fig. 1. Anti-Lm antibodies acquire protective function during pregnancy.

(a-c) Anti-Lm IgG titers (a), survival (b) and bacterial burdens (c) in neonatal mice infected with virulent Lm born to WT, μMT−/− or CD8−/− female mice primed with attenuated ΔActA Lm one week prior to mating or naive WT control mice without preconceptual priming. (d) Bacterial burden in neonatal mice infected with virulent Lm born to WT female mice primed with ΔActA Lm or virulent Lm 3 weeks prior to mating. (e) Bacterial burden 3 days after secondary challenge of ΔActA Lm-primed virgin female CD8−/− adult mice or preconceptually ΔActA Lm-primed CD8−/− female mice 3 weeks post-partum. (f) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred sera from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin (vSera) or pregnant mice in late gestation through early postpartum (pSera). (g) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred sera from preconceptual ΔActA Lm-primed mice harvested during the indicated pregnancy or postpartum time points. (h) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice cross-fostered within 12 hours after birth by naive or ΔActA Lm-primed dams. (i) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice nursed by WT, μMT−/−, or FcRγ−/− mice administered vSera on the day of delivery and 3 days later. Pups were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons (a, c, d, f, g, h, i), unpaired t-test (e), or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (b). Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Given these counterintuitive roles for humoral compared with cellular immune components in vertically transferred anti-Lm immunity, we verified the importance of CD8 T cells and non-essential role of B cells for Lm protection in primed adult virgin mice1,2,13–15 (Extended Data Fig. 1d). Interestingly, CD8-mediated immunity could be bypassed by pregnancy, given significantly reduced Lm susceptibility in primed post-partum CD8−/− mothers compared with primed virgin females each containing similar anti-Lm antibody titers (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1e). Pregnancy-enabled antibody-mediated protection was confirmed by showing reduced Lm susceptibility in neonates passively transferred sera from Lm-primed pregnant and postpartum dams (pSera), but not sera from primed virgin mice (vSera), despite increased antibody titer (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2a). Protective antibodies emerged in late pregnancy since sera harvested from preconceptually primed mice in late gestation (E18-20) or postpartum (P30-35) were similarly efficacious, whereas sera from mid-gestation (E10-12) donor mice were non-protective (Fig. 1g). Cross-fostering studies demonstrated transfer of protective Lm-specific IgG regardless of in utero or postnatal acquisition via breastfeeding with similarly reduced neonatal Lm susceptibility (Fig. 1h, Extended Data Fig. 2b).

Efficient breastmilk transfer of maternal antibodies was exploited to further investigate whether pregnancy enabled protection via de novo antibody production or post-translational modification of pre-existing antibodies. Remarkably, anti-Lm IgG in vSera became protective when indirectly transferred to pups via WT or μMT−/− nursing dams, dissociating protective antibody conversion from maternal B cells (Fig. 1i, Extended Data Fig. 2c). However, maternal Fcγ receptors (FcγR), broadly required for leukocyte-mediated antibody effector functions16,17, were essential, since pups nursed by FcRγ−/− dams passively transferred vSera remained susceptible, despite anti-Lm IgG transfer through breastmilk (Fig 1i, Extended Data Fig. 2c). WT males again sired pregnancy generating phenotypically WT (μMT+/− and FcRγ+/−) offspring. Antibody acquisition of protective function requiring maternal FcγR was recapitulated in vitro, as incubating vSera with splenocytes from pregnant WT, but not pregnant FcRγ−/− mice, enabled protection upon passive transfer to neonatal recipients (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Thus, while maternal B cells are essential for producing antibodies that mediate vertically transferred immunity, they are dispensable for pregnancy-induced acquisition of protective function, which instead relies on modification of pre-existing anti-Lm IgG and FcγR-bearing maternal cells.

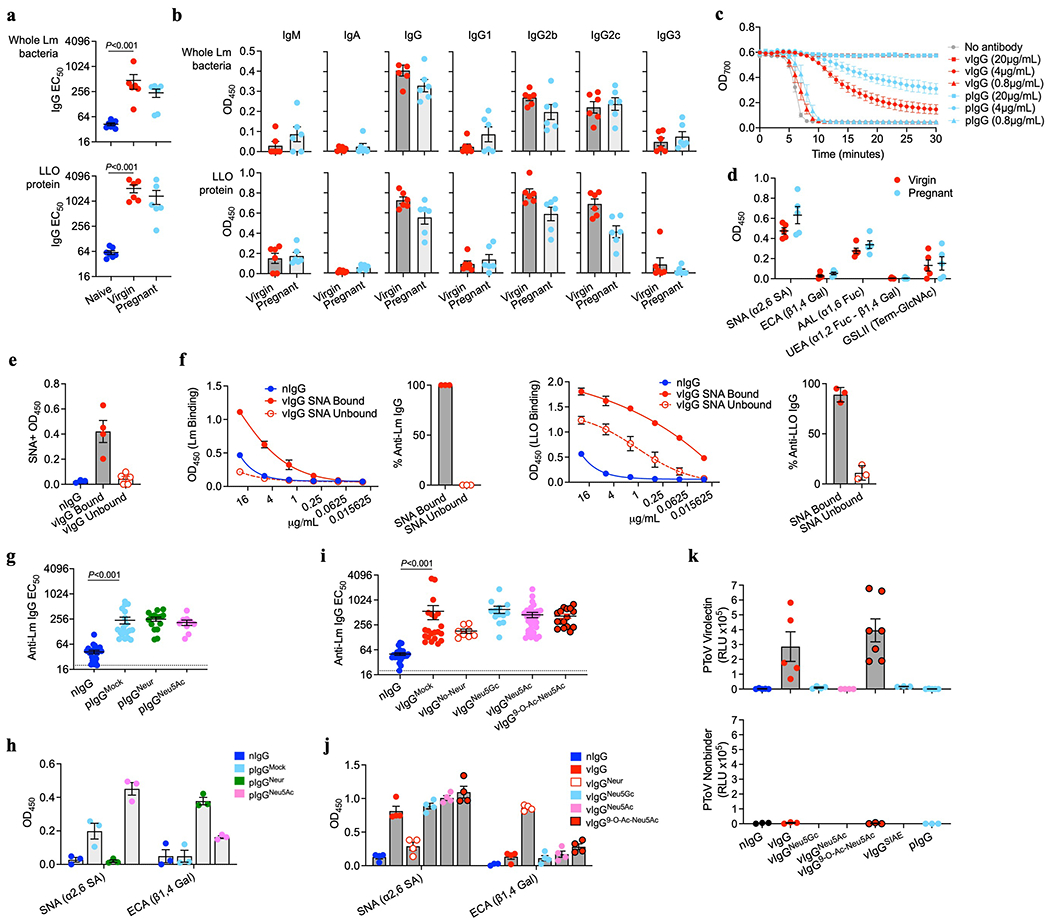

Pregnancy Deacetylates IgG Sialic Acid

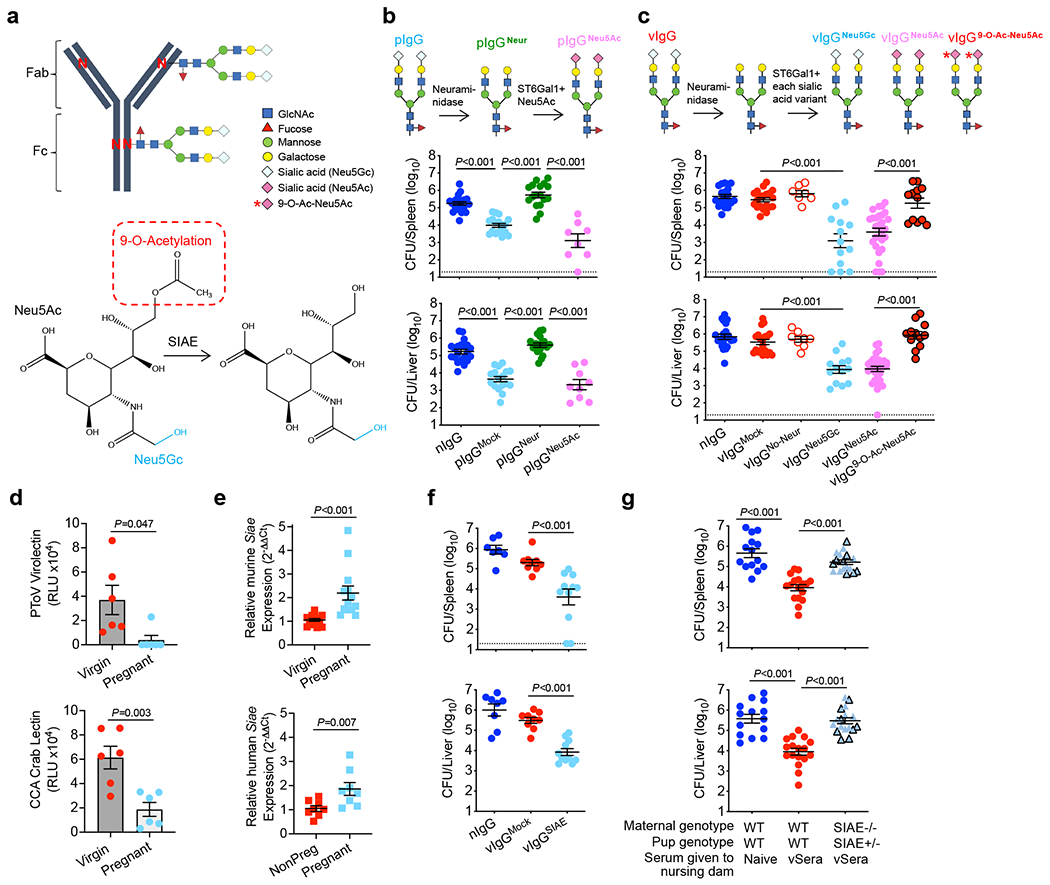

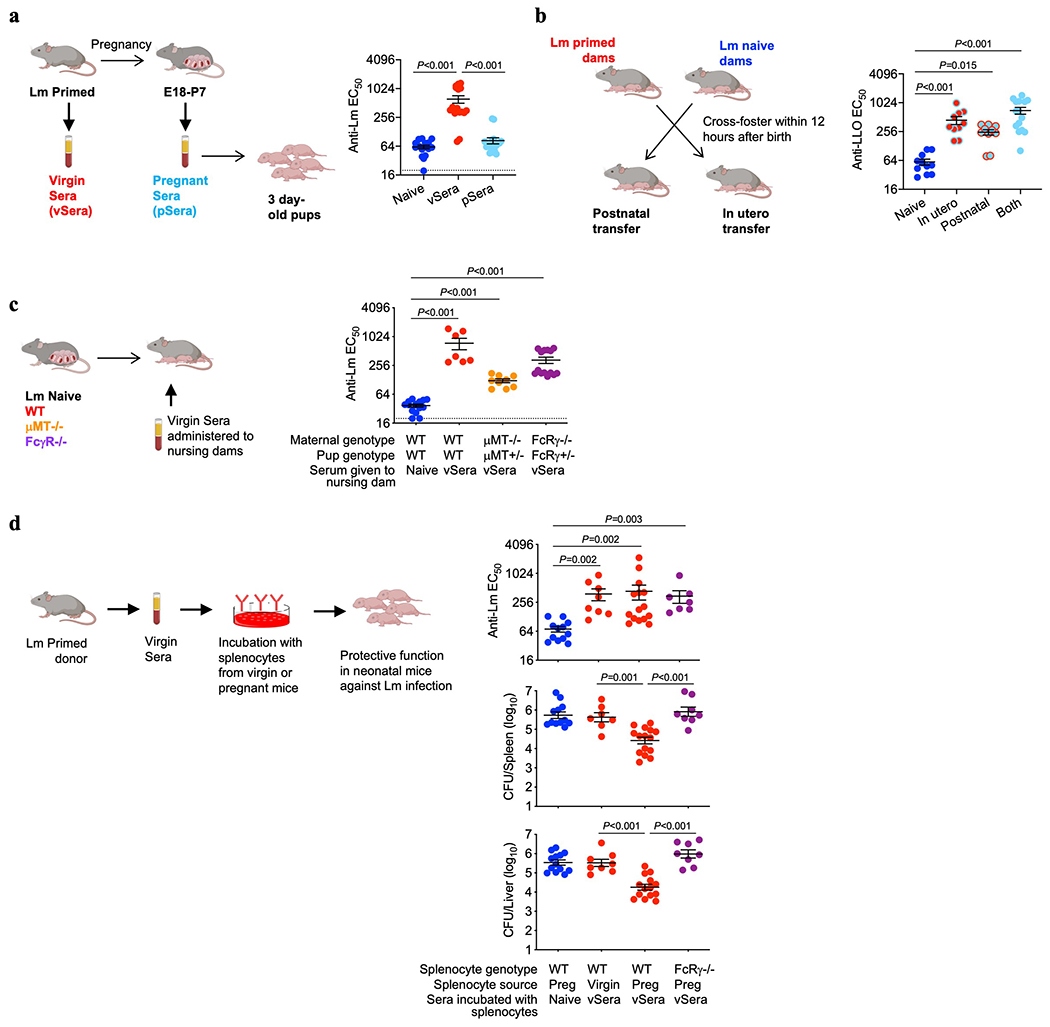

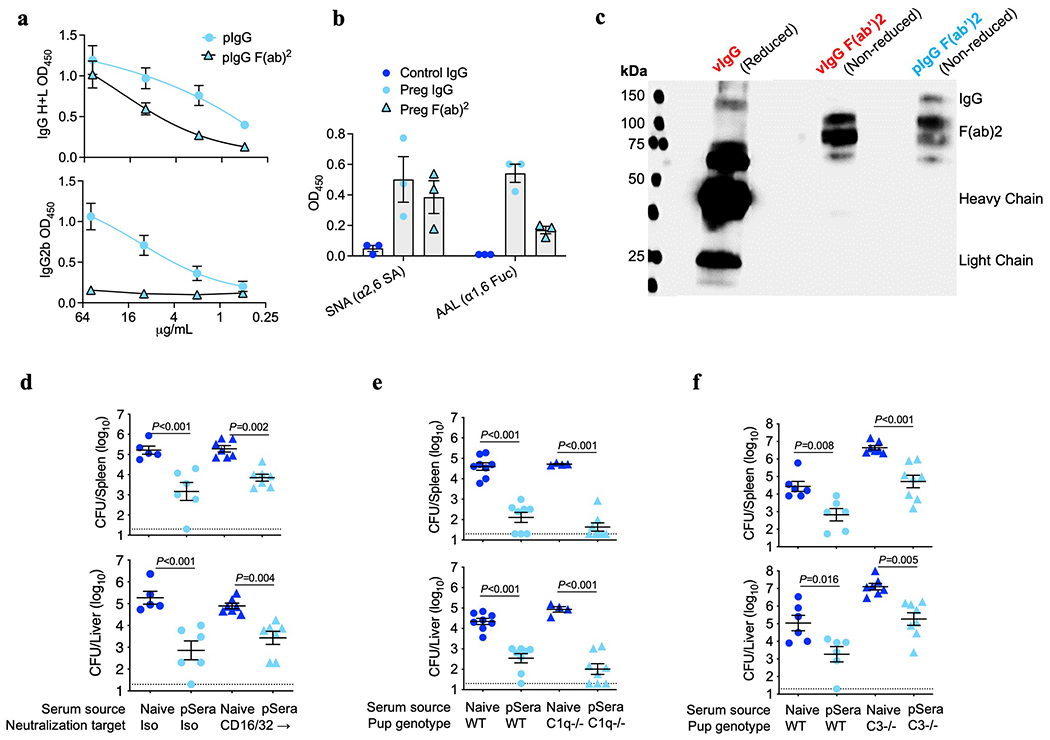

IgG purified from Lm-primed virgin (vIgG) and preconceptually primed pregnant/postpartum (pIgG) mice was compared to determine the molecular features responsible for discordant protection against intracellular infection. Pregnancy altered neither the overall titer nor level of individual antibody isotypes with specificity to Lm-bacteria or purified LLO protein, with predominant accumulation of IgG2 (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). vIgG and pIgG similarly reduced LLO-induced hemolysis, indicating no difference in functional neutralization (Extended Data Fig. 3c). vIgG and pIgG binding to a panel of carbohydrate-specific lectins showed similar patterns of N-linked glycosylation, an important post-translational IgG modification, with predominant terminal α2,6-linked sialic acid (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3d). SNA lectin-fractionization, which preferentially binds IgG with sialylated Fab region N-glycans18, revealed that >90% of anti-Lm IgG contains sialic acid (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f).

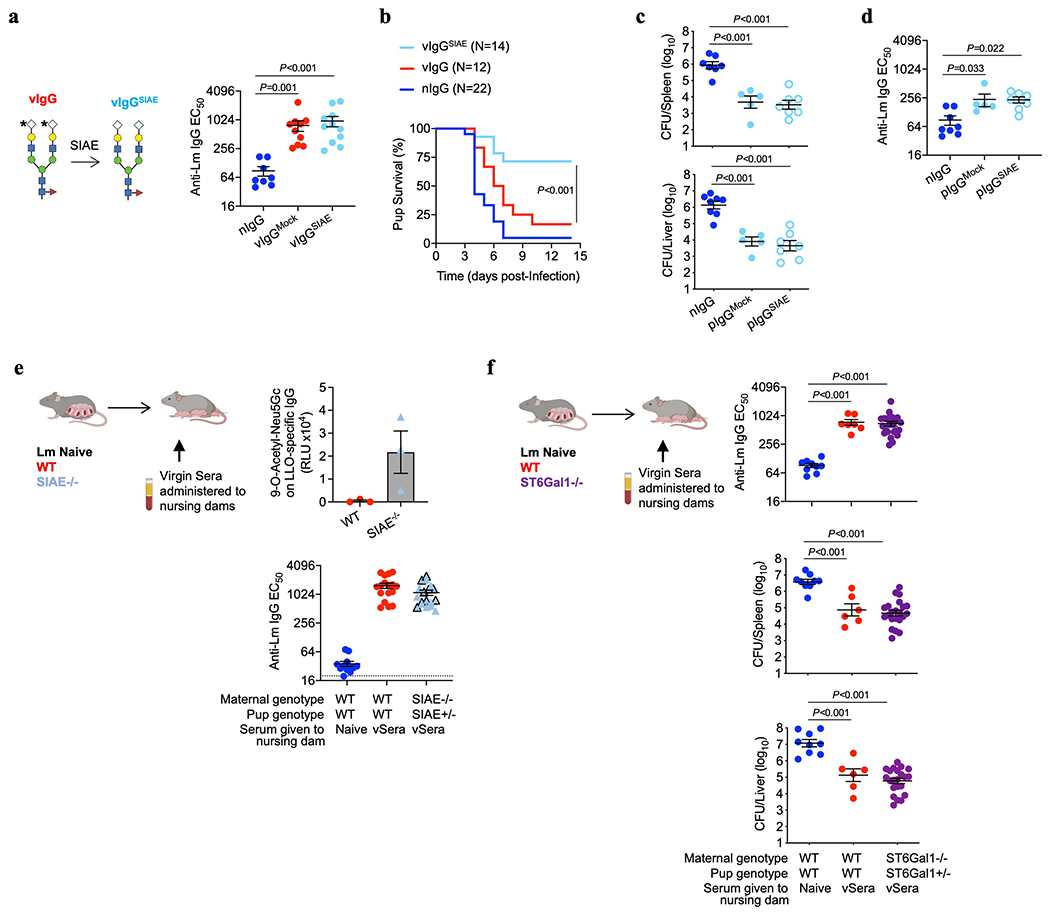

Fig. 2. SIAE deacetylates anti-Lm IgG sialic acid enabling antibody-mediated protection.

(a) IgG N-linked glycosylation schematic including sialic acid variants and SIAE activity. (b) IgG from naive (nIgG) or preconceptual ΔActA Lm-primed pregnant/postpartum (pIgG) mice was glycoengineered to remove existing sialic acid with neuraminidase (pIgGNeur) followed by resialylation with ST6Gal1 plus CMP-Neu5Ac (pIgGNeu5Ac). Bacterial burdens after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice following transfer of indicated pIgG preparations. (c) IgG recovered from naive (nIgG) or ΔActA Lm-primed virgin (vIgG) mice, treated with neuraminidase, then resialylated with each sialic acid variant using ST6Gal1 plus CMP-sialic acid donors. Bacterial burdens after Lm infection in neonatal mice following transfer of indicated vIgG preparations. (d) PToV virolectin and CCA lectin detection of 9-O-Acetyl-Neu5Gc in virgin compared with pregnant LLO-specific IgG. (e) Relative Siae expression in splenocytes from virgin and late gestation (E18-20) pregnant mice, or in PBMCs from non-pregnant (NonPreg) versus pregnant women (12-32 weeks gestation). (f) Bacterial burden after Lm infection in neonatal mice administered SIAE- or mock-treated vIgG. (g) Bacterial burden after Lm infection in neonatal mice nursed by WT or SIAE−/− (black outline, exon3−/−; no outline, exon3/4−/−) mice administered vSera on the day of delivery and 3 days later. Pups were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, and where indicated, 24 hours after antibody transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment (b, c, e-g), or representative data from >3 independent experiments (d). Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups were determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons (b, c, f, g) or unpaired t-test (d, e). Dotted lines, limit of detection.

The functional importance of sialic acid was evaluated by neuraminidase digestion, demonstrating desialylation completely abolished pIgG-mediated protection against neonatal Lm infection (Fig. 2b). Reciprocally, protection was fully restored by ST6 β-galactosidase α2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6Gal1) addition of sialic acid in the form of acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 3g,h). Interestingly, vIgG did not acquire protective function by adding Neu5Ac without neuraminidase pre-treatment (Fig. 2c), suggesting sialic acid molecular variants19 could be responsible for the differential protection between vIgG and pIgG. Porcine torovirus hemagglutinin-esterase (PToV) lectin with specificity for 9-O-acetylated sialic acid20,21 displayed sharply reduced binding to LLO-specific IgG from pregnant compared with virgin mice (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 3k). Cancer antennarius (CCA) lectin with specificity for 9-O and 4-O-linked acetylation22 showed similar differences (Fig. 2d), whereas neither vIgG nor pIgG bound to mouse hepatitis virus hemagglutinin-esterase lectin with 4-O-acetylated sialic acid specificity20,21, indicating selective 9-O-acetylation of sialic acid on Lm-specific IgG from virgin compared with pregnant mice. Importantly, vIgG acquired protective function following native sialic acid replacement with Neu5Ac (the predominant human variant due to CMAH inactivation23) or glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc, the predominant murine sialic acid24), but not 9-O-acetylated sialic acid (9-O-Ac-Neu5Ac) (Fig. 2c), with similar titers of anti-Lm IgG transferred to neonates and staining with multiple lectins confirming precise sialylation with each glycoform (Extended Data Fig. 3i–k). Thus, 9-O-acetylation of N-glycan terminal sialic acid residues renders antibodies nonprotective against Lm infection.

Sialic acid acetyl esterase (SIAE) removes 9-O-acetylation from sialic acid (Fig. 2a), with polymorphisms linked with autoimmunity and pregnancy complications5,25. We found pregnancy-induced SIAE upregulation amongst leukocytes in both mice and women (Fig. 2e), suggesting conserved regulation of sialic acid acetylation during pregnancy. Importantly, SIAE removal of 9-O-acetylation from vIgG, confirmed with PToV lectin staining (Extended Data Fig. 3k), reduced bacterial burdens and enhanced survival after transfer into neonatal mice (Fig. 2f; Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). Comparatively, protective potency of pIgG was not further enhanced by SIAE treatment (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d), indicating optimal deacetylation during pregnancy. Two independently generated strains of SIAE-deficient mice (exon 3 and exon 3/4 deletion) each verified that maternal SIAE is essential for converting non-protective acetylated IgG present in vSera to the protective deacetylated form (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 4e), whereas retained protective conversion of vSera in ST6Gal1−/− mice indicates anti-Lm IgG is not de- and then resialylated (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Thus, SIAE-mediated sialic acid deacetylation of antibodies during pregnancy unleashes their protective function against intracellular infection.

Acetylation Localizes to the Fab Region

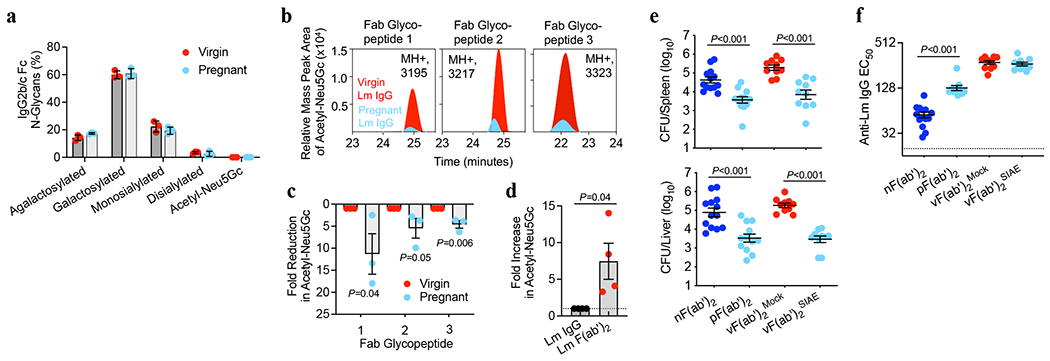

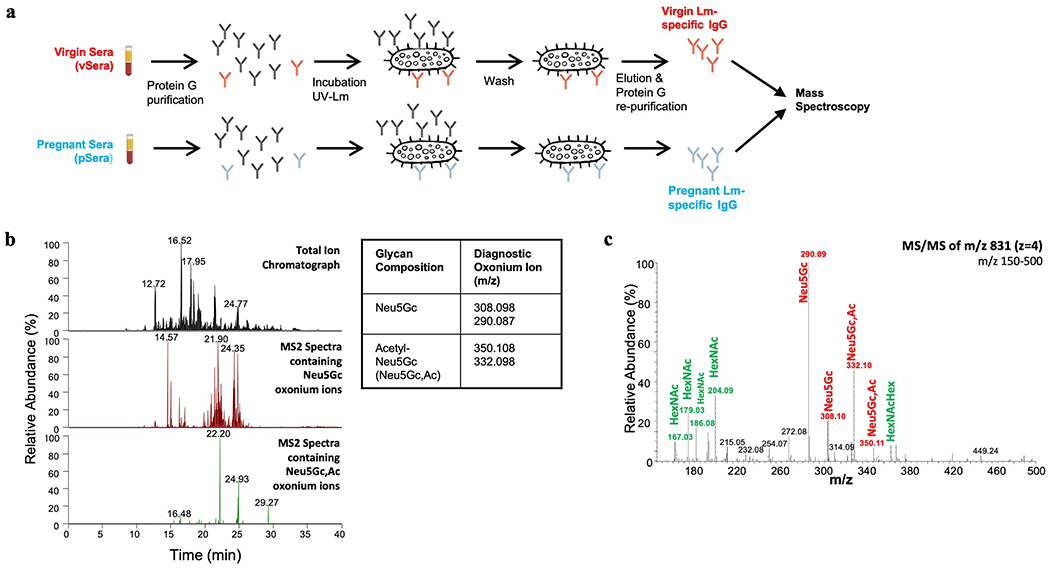

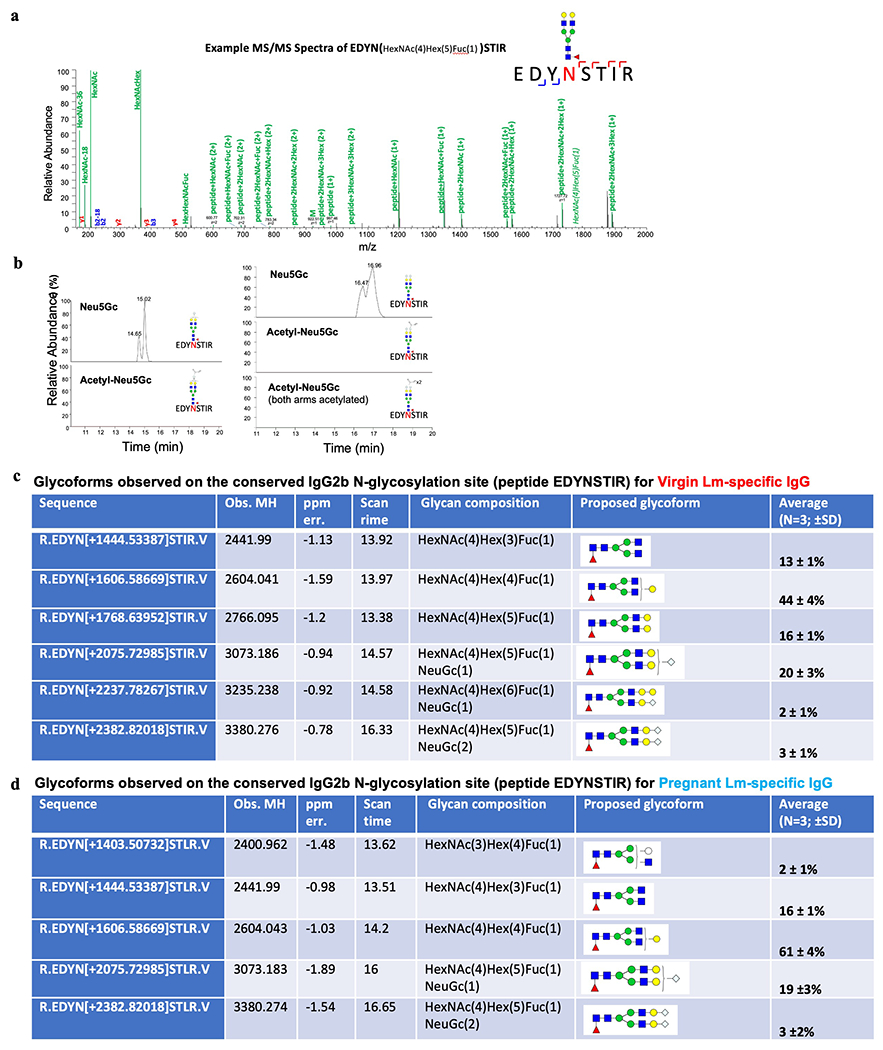

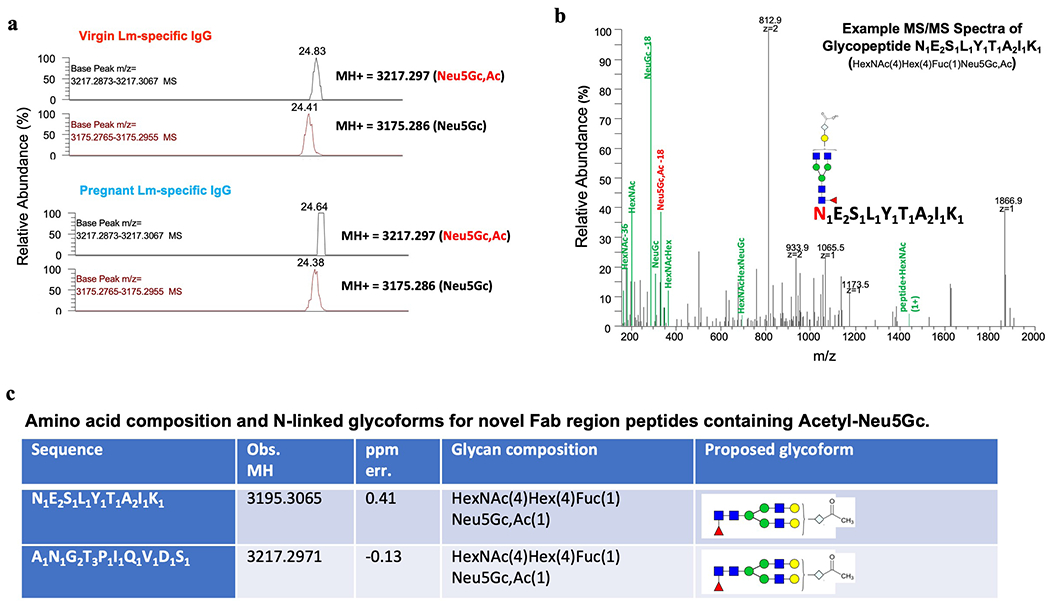

Tandem mass spectrometry on purified Lm-specific IgG from virgin and pregnant mice was performed to confirm sialic acid acetylation and its location based on oxonium ion signatures26 (Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). Glycopeptide mapping revealed the absence of acetylation on conserved Fc region N-linked glycans, with only 20-25% of IgG2 Fc containing any sialic acid, all in the form of Neu5Gc (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 6). Instead, biantennary N-glycans containing acetylated Neu5Gc (Acetyl-Neu5Gc) were identified in three unique glycopeptides, each demonstrating a 42 Dalton mass increase over Neu5Gc, corresponding to addition of a single acetyl group and excluding derivation from other acetylated biomolecules (Extended Data Fig. 7). Importantly, these glycopeptides from pregnant compared with virgin Lm-specific IgG contain 5 to 10-fold less Acetyl-Neu5Gc (Fig. 3b,c), consistent with prior results utilizing PToV and CCA lectin staining for 9-O-Acetyl-Neu5Gc (Fig. 2d, Extended Data 3j,k).

Fig. 3. Acetylated sialic acid localizes to Fab N-glycans.

(a) Percentage IgG2 conserved Fc N-glycan sites with each indicated glycoform. (b) Relative mass peak area for Acetyl-Neu5Gc determined by tandem mass spectroscopy oxonium ion filtering on three unique Fab glycopeptides from Lm-specific IgG purified from virgin or pregnant mice. (c) Fold-reduction in Acetyl-Neu5Gc for each Fab glycopeptide in pregnant compared with virgin Lm-specific IgG described in panel b. (d) Fold increase in Acetyl-Neu5Gc after pepsin treatment for Fab glycopeptides relative to untreated full-length IgG. (e, f) Bacterial burdens (e) and anti-Lm F(ab’)2 titers (f) after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred pepsin-treated IgG from: naive mice [nF(ab’)2], pregnant/postpartum Lm-primed mice [pF(ab’)2], or virgin Lm-primed mice [vF(ab’)2] treated with SIAE to remove acetylation from sialic acid residues. Pups were infected with virulent Lm 4 days after birth, 24 hours after F(ab’)2 transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Mass spectroscopy experiments were performed 3-4 times using purified IgG pooled from virgin or pregnant mice and data from each replicate experiment is shown (a-d). For infection and anti-Lm titers, each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment (e, f). Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons (e, f) or unpaired t-test (c, d).

We reasoned that 9-O-acetylation localizes to terminal sialic acid residues in the polymorphic Fab variable region since acetylated sialic acid was neither present on the conserved Fc glycosylation site nor found to originate from variable region immunoglobulin genes containing germline-encoded N-linked glycosylation sites27. Fab glycosylation was confirmed by finding retained α2,6-linked sialic acid and diminished α1,6-linked fucose on Lm-specific F(ab’)2 fragments (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b), lectin blot demonstrating α2,6-linked sialic acid on the ~100kDa F(ab’)2 fragments (Extended Data Fig. 8c), and increased ratio of acetylated to non-acetylated Neu5Gc on Lm-specific F(ab’)2 fragments compared with full length IgG by mass spectroscopy (Fig. 3d). Functional consequences of Fab 9-O-acetylation were verified by showing pIgG-derived F(ab’)2 fragments, as well as SIAE-deacetylated vIgG-derived (Fab’)2 fragments, each sharply reduced susceptibility to Lm infection (Fig. 3e,f). Antibodies from pregnant mice retained protection in anti-FcγR antibody-treated and complement deficient mice (Extended Data Fig. 8d–f), reaffirming that Fc-mediated functions in neonates are dispensable. Therefore, pregnancy expands antibody-mediated protection against intracellular infection via IgG-Fab variable region sialic acid deacetylation.

CD22-Dependent Inhibition of B10 Cells

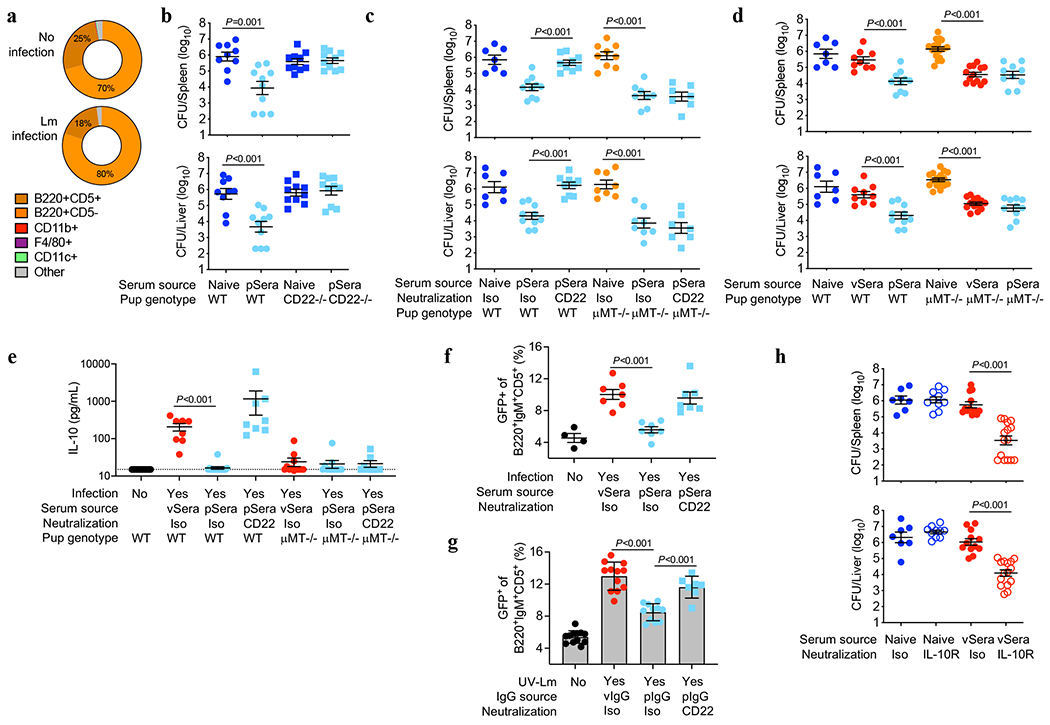

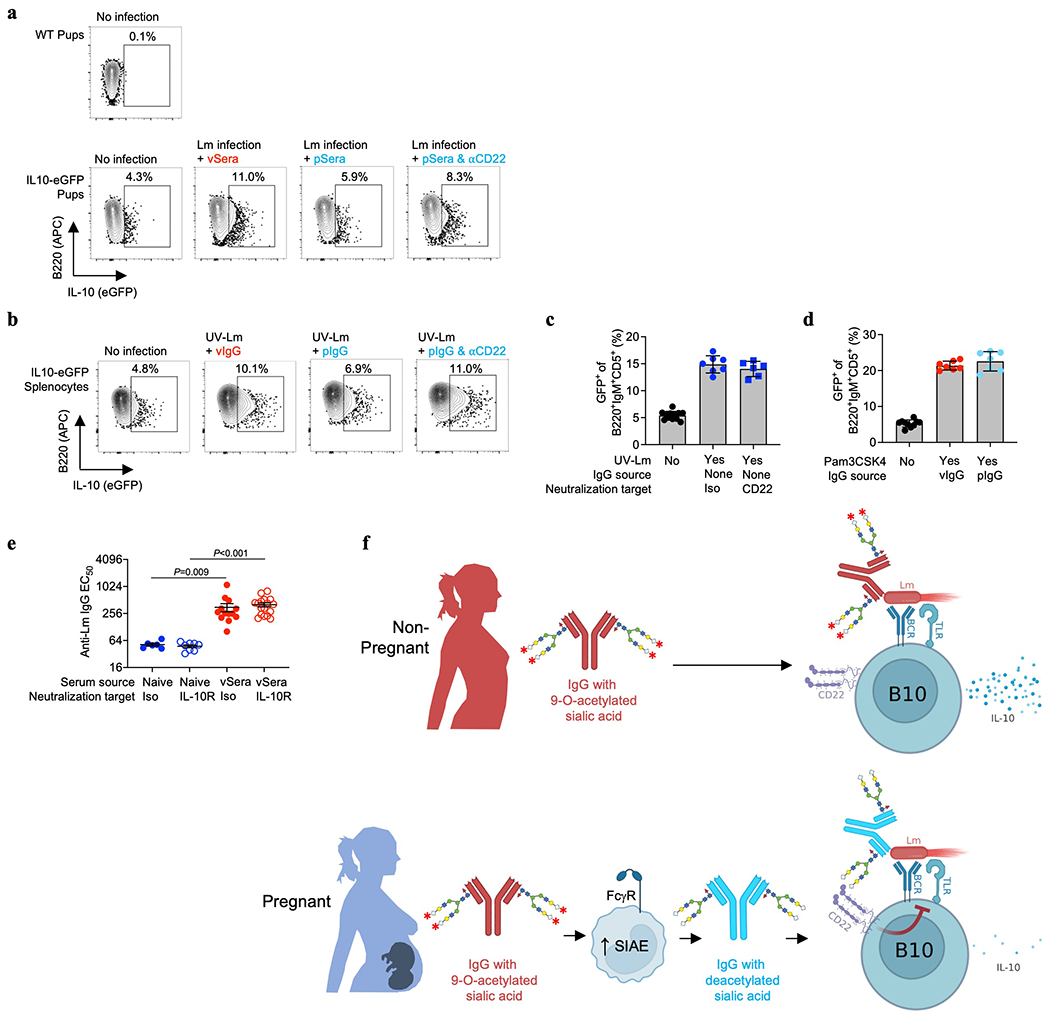

Since 9-O-acetylation masks sialylated ligands for the Siglec CD22, which is primarily expressed by B lymphocytes and blunts their activation6,7,23,28, we investigated whether pregnancy-deacetylated IgG stimulates CD22-dependent inhibition of B cells. In agreement, ≥95% of CD22+ cells were B lymphocytes (both B220+CD5− B-2 and B220+CD5+ B-1a cells) in naive and Lm-infected neonates (Fig. 4a), and CD22 was essential for pSera protection, shown using CD22-deficient mice or WT mice administered CD22-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). Conversely, CD22 neutralization failed to override pSera protection in μMT−/− pups (Fig. 4c), confirming the importance of CD22 expression on B cells. Given the lower affinity of Neu5Ac-compared with Neu5Gc-containing ligands for murine CD2229,30, dependence on this Siglec for protection by vIgG engineered to express Neu5Ac was confirmed using both CD22-deficient mice and neutralizing antibody (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e). Furthermore, vSera, which provides no defense in WT mice, efficiently protected μMT−/− pups (lacking all B cells) and CD19−/− pups (lacking only B-1a cells31,32), confirming B cell suppression of anti-Lm antibody protective function (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 9f–h).

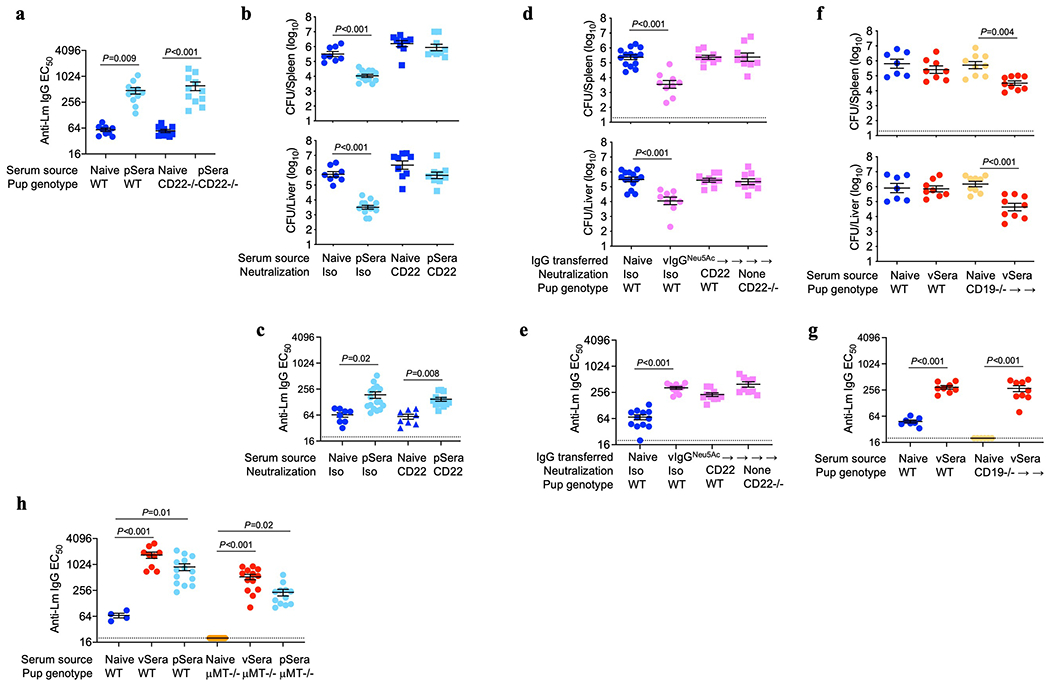

Fig. 4. Deacetylated anti-Lm antibodies protect via CD22-mediated suppression of B cell IL-10 production.

(a) CD22+ cell distribution amongst neonatal splenocytes 72 hours after Lm infection compared with uninfected controls. (b) Bacterial burden after Lm infection of WT or CD22-deficient neonatal mice transferred sera from ΔActA Lm-primed pregnant/postpartum (pSera) or naive mice. (c) Bacterial burden after Lm infection of WT or μMT−/− neonates administered pSera or naive sera, along with anti-CD22 or isotype control antibodies. (d) Bacterial burden after Lm infection of WT or μMT−/− neonates administered sera from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin mice (vSera), pSera, or naive sera. (e) Serum IL-10 levels 72 hours after Lm infection in WT or μMT−/− neonates administered vSera or pSera, plus CD22 neutralization . (f) B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocyte GFP expression 72 hours after Lm infection in neonatal IL10-eGFP reporter mice administered vSera or pSera, plus CD22 neutralization, compared with uninfected mice. (g) GFP expression by B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocytes from IL10-eGFP neonates stimulated with UV-inactivated Lm in the presence of vIgG or pIgG, plus CD22 neutralization. (h) Bacterial burden after Lm infection in neonates administered vSera or naive sera, along with anti-IL10 receptor or isotype control antibodies. Neonatal mice were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, 24 hours after antibody transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Pie charts show representative data from one of 3 independent experiments, averaged across 5 mice per group (a). Each symbol represents the data from an individual mouse (b-f, h) with graphs showing data combined from at least 3 independent experiments with 3-5 mice per group per experiment, or cells in an individual well under unique stimulation conditions combined from 4-5 independent experiments (g). Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between groups determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted line indicates limit of detection.

B lymphocyte subsets producing the immune-suppressive cytokine IL-10 enhance Lm susceptibility33–35. In agreement, Lm induced high serum IL-10 levels in WT, but not μMT−/−, pups treated with vSera, while IL-10 in WT mice was drastically reduced with administration of pSera and reversed with CD22-neutralization (Fig. 4e). Use of IL-10 reporter (Vert-X) mice verified activation of B220+IgM+CD5+ IL-10 producing B cells (B10 cells)31,32, which exhibited CD22-dependent suppression by pSera (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 10a). Neonatal B10 cell stimulation in vitro by UV-inactivated Lm demonstrated similar CD22-dependent inhibition by pIgG, but not vIgG (Fig. 4g, Extended Data Fig. 10b,c). Collectively, these results highlight an essential role for CD22 in deacetylated anti-Lm IgG suppression of neonatal B10 cells. Importantly, pIgG specifically repressed Lm activation of B10 cells since it had no effect on agonistic stimulation through TLR2, the main receptor required for innate Lm sensing36 (Extended Data Fig. 10d). The in vivo necessity of IL-10 in overriding protection by anti-Lm IgG was confirmed using IL-10 receptor blockade, which enabled protection by vSera (Fig. 4h, Extended Data Fig. 10e), phenocopying results observed in μMT−/− and CD19−/− pups (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 9f). Thus, absence of IL-10 or inhibitory B lymphocytes bypasses functional impairment of acetylated virgin anti-Lm IgG, whereas pregnancy deacetylates antibodies enabling CD22-mediated inhibition of B10 cells, enabling protective immunity against Lm intracellular infection.

DISCUSSION

The foundational immunological tenet that humoral and cell-mediated adaptive immunity play non-overlapping functions is largely based on Lm infection experiments demonstrating that convalescent serum from mice with resolved infection cannot transfer protection to naive recipient mice, whereas protection is readily transferred with donor splenocytes containing T cells1,2,13–15. However, these passive transfer studies exclusively using virgin adult animals likely have limited relevance to the unique susceptibility of newborn babies relying on vertically transferred immunity. By considering the maternal-fetal dyad as a joined immunological unit, and the only biological context where immune components are naturally transferred between individuals, unexpected protective roles for Lm-specific antibodies are revealed. Expanded scope of antibody-mediated protection is likely especially important in the neonatal period with immature T cell-mediated immunity.

A key distinction for Lm-primed IgG is the ability to become protective following N-glycan sialic acid deacetylation. Protection occurred despite low-level vertical transfer of polyclonal maternal antibodies, therefore operating through mechanisms distinct from those previously shown for neutralizing anti-LLO monoclonal antibody clones that protected only at very high titer37. Indeed, both pregnancy- and ex vivo enzymatically-deacetylated IgG protect against Lm via Fab region sialic acid interaction with the Siglec CD22, which negatively regulates B cell transmembrane signaling through BCR and TLRs by recruitment of the intracellular phosphatases SHP-1 and SHIP6,7,23. IgM and IgG containing sialylated N-glycans have previously been shown to bind to CD22 on B cells38,39. We demonstrate that anti-Lm IgG engineered to express either Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc are both protective, despite Neu5Ac’s lower affinity relative to Neu5Gc for ligand binding to murine CD2229,30. Thus, engagement with sialylated antibodies likely relies on receptor clustering to increase avidity, especially given CD22 reorganization near the BCR during B cell activation40. Importantly, CD22 binding to sialylated ligands is uniformly silenced by acetylation28, consistent with our results demonstrating anti-Lm IgG from virgin mice and glycoengineered vIgG expressing 9-O-acetylated sialic acid are both nonprotective.

We further show that CD22 selectively inhibits IL-10 production by B cells, which are known to promote Lm susceptibility33–35. B10 cells are a regulatory subset of B-1a cells, and are activated through BCR or TLR interactions31, and our findings of suppressed activation by deacetylated pIgG is consistent with CD22 inhibition of both these activating receptors6,41. Lm-specific IgG may bridge activating B10 receptors and CD22 through bivalent IgG simultaneously binding Lm and CD22 via deacetylated Fab sialic acid (Extended Data Fig. 10f). Therefore, a key adaptation employed by Lm to evade antibodies is through activation of B10 cells, since IL-10 suppresses bactericidal activity in macrophage and other antigen-presenting cells31,32,35. These results fundamentally expand mechanisms of antibody-mediated protection to include intracellular pathogens, which previously were thought to rely primarily on extracellular neutralization or Fc receptor binding42.

Our results also raise important new questions about immunological consequences associated with sialic acid deacetylation. SIAE polymorphisms have been linked with autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis and type I diabetes mellitus5. Additionally, CD22 polymorphisms are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus43. These observations plus our own data suggest that high affinity self-reactive antibody clones may be acetylated as a means to prevent autoimmunity through decreased CD22 binding, at the expense of antimicrobial immunity. Sialic acid acetylation also reduces activity of human neuraminidases44, which may fine-tune antibody half-life and optimize embryogenesis, since forced expression of sialic acid-deacetylating enzymes in mice is associated with tissue-specific developmental defects45. Expansion of maternal B cells with fetal specificity is actively suppressed via CD22 during murine pregnancy46, and increased placental SIAE expression during human pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia25 together suggest that modulation of sialic acid acetylation may promote fetal tolerance. Acetylated sialic acid is also the target for several viral attachment proteins20, and therefore SIAE upregulation during pregnancy may decrease infection susceptibility. Important areas for future study include evaluating how SIAE and sialic acid receptors control development, and reciprocally, how expression of these molecules is developmentally regulated.

Neonatal susceptibility to intracellular infections, despite these pregnancy-induced antibody modifications, may reflect inadequate maternal pathogen exposure, especially considering serotype diversity of common intracellular pathogens. For example, congenital cytomegalovirus infection risk is ~20-fold increased for women with primary infection compared with secondary infection during pregnancy47, and especially by maternal reinfection with a serologically distinct CMV strain48. Similarly, HSV resistance in neonates is associated with maternal type-specific antibodies49. For Lm, the relatively high seroprevalence in women50, together with expanded range of protection by Lm-specific antibodies we now demonstrate, likely explains the disproportionately small incidence of neonatal infection. In the broader context, consideration of the maternal-fetal dyad as a joined immunological unit unveils newfound protective roles for antibodies against intracellular infection8,42, highlighting precise fine-tuning of host defenses to mitigate vulnerability during pregnancy and in early life.

METHODS

Mice

Inbred C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute or generated by in-house breeding. μMT−/− (002288), CD8−/− (002665), FcRγ−/− (002847), CD22−/− (006940), CD19Cre/Cre (CD19−/−, 006785), IL10-eGFP (Vert-X, 014530), C1q−/− (031675) and C3−/− (029661) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock number). ST6Gal1−/− mice have been described51. SIAE−/− mice were generated by the CCHMC Transgenic Animal and Genome Editing Core by constructing a SIAE-deficient allele via a dual sgRNA CRISPR/Cas9. Briefly, three sgRNAs (target sequences: #1 CCTGAGCTTAGCCACAAATG, #2 CATGCAGATGACTGTTTCAC and #3 GAACCAAATTCAGGGGCTAC) were selected, according to the on- and off-target scores from the web tool CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net)52 and chemically synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The sgRNA pairs (#1 and #2) and (#1 and #3) were used to delete exon 3 and exons 3/4 of Siae, respectively. To prepare the ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP) for each targeting, we incubated the sgRNA pair (40 ng/μL per sgRNA) and Cas9 protein (120 ng/μL; IDT) in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher) at 37°C for 15 min. The zygotes from super-ovulated female mice on the C57BL/6J genetic background were electroporated with 7.5μL RNP on a glass slide electrode using the Genome Editor electroporator (BEX; 30V, 1millisecond width, and 5 pulses with 1sec interval). Two min after electroporation, zygotes were moved into 500μL cold M2 medium (Sigma), warmed up to room temperature, and then transferred into the oviductal ampulla of pseudopregnant CD-1 females. Pups were born and genotyped by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at 25°C, ambient humidity, a 12 hour day/night cycle, with free access to water and a standard chow diet. Females between 8 and 12 weeks of age were used for all experiments. For some experiments, timed mating was performed by synchronized introduction of males to breeding cages. For experiments examining immunodeficient maternal mice, females were mated with WT males to generate heterozygous, immunocompetent offspring. Mice were checked daily for birth timing. Neonatal mice were evaluated from birth (cross-fostering experiments), or between 3-4 days of age as described. Neonates from the same litter were divided amongst groups for individual experiments. For cross foster experiments, pups were switched between nursing dams within 12 hours of birth. For survival experiments, mice were sacrificed when moribund. Adult mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation. Neonates were sacrificed via decapitation. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center.

Bacteria and infections

Listeria monocytogenes (wildtype strain 10403s or attenuated ΔActA DPL-1942) was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium at 37°C, back diluted to early logarithmic phase (optical density 600nm 0.1) and resuspended in sterile PBS as described53,54. Female mice were preconceptually primed with ΔActA Lm 107 CFU injected intravenously (i.v.). For some experiments, a second injection was given 2-3 weeks later. Mice were mated 5-7 days after priming. For virulent infection, adult mice were inoculated i.v. with a dose of 2x104 CFU per mouse, except Fig. 1d where mice received 105 CFU. Neonatal mice were infected with 50-100 CFU intraperitoneally (i.p.). For fungal infections, neonatal mice were infected i.p. with 106 CFU of Candida albicans (strain SC5314) grown in YPAD media as described55. The inoculum for each experiment was verified by spreading a diluted aliquot onto agar plates. To assess susceptibility after infection, mouse organs (spleen and liver) were dissected and homogenized in sterile PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 to disperse the intracellular bacteria, and serial dilutions of the organ homogenate were spread onto agar plates. Colonies were counted after plate incubation at 37° C for 24 hours.

Serum harvest and IgG purification

For phlebotomy, adult mice were bled 200μL via submandibular bleed or via cardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice. For neonates, blood was collected after decapitation. To harvest serum, the blood was allowed to clot at room temperature and then spun at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Serum was removed and then heat inactivated (56°C for 20 min). Sera were collected separately and pooled from several Lm-primed mice. Sera from Lm-primed virgin mice (vSera) were collected starting 2-weeks after the last dose of ΔActA Lm. Sera from preconceptually Lm-primed pregnant mice (pSera) were collected starting from late gestation (~E18) to post-partum day 7 (P7). Adoptive sera transfers were accomplished via i.p. injection in adults (200μL volume) or neonates (50μL volume). For breastmilk transfer of antibodies, nursing dams were injected with vSera when pups were P0 and P3.

Sera containing anti-Lm antibodies were purified over Protein A columns per manufacturer instructions (Abeam, catalog no. 109209) to obtain the IgG-containing fraction. Purified IgG was concentrated and dialyzed to PBS using the Amicon® Ultra Pro Purification System (Millipore, ACS510024). Protein G spin columns (Thermo, 89953) were utilized to isolate IgG from individual mice. IgG from naïve mice was purified from sera or commercially available (Sigma, I5381). Neonates were transferred 50-75μg purified Lm-immune IgG.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

For evaluating Lm-specific antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), flat-bottom, high-binding, 96-well enzyme immunoassay (EIA)/radioimmunoassay (RIA) plates (Costar) were coated with nearly confluent log-phase Lm 10403S and allowed to dry overnight under UV light. Alternatively, plates were coated with recombinant LLO toxin at 1 μg/mL for at least 24 hours. Coated plates were then blocked with 3% milk. All wash steps were performed in triplicate with PBS + 0.05% Tween-20. Serum from each mouse was diluted 1:10 or 1:20 and then 1:4 serial dilutions were performed followed by staining with the following biotin-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies: rat anti-mouse IgG (eBioscience, 13-4013-8), rat anti-mouse IgM (eBioscience, 13-5890-1589), rat anti-mouse IgA (eBioscience, 13-5994-82), rat anti-mouse IgG1 (BD Pharmingen, cat. no. 553441), rat anti-mouse IgG2b (BD Pharmingen, 553393), rabbit anti-mouse IgG2c (Invitrogen, SA5-10235), and rat anti-mouse IgG3 (BD Pharmingen, 553401). Each secondary antibody was used at 1:1,000 dilution. Plates were developed with streptavidin-peroxidase (BD Bioscience, 554066) using o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride as a substrate and measuring absorbance at 450 nm (A450) as described 56. Antibody titers were quantified as EC50 (the point of 50% maximum OD450) using a nonlinear second order polynomial in Prism (GraphPad).

To detect N-glycans, LLO-coated plates were utilized to avoid staining endogenous glycans present on Lm bacteria. Plates were blocked with a carbohydrate-free blocking buffer (VectorLabs, SP-5040-125). Purified IgG was added at 0.1-0.2mg/mL final concentration and then biotinylated lectins (from VectorLabs, except where noted) with defined carbohydrate specificity were used as secondary probes: SNA (terminal α2,6 Sialic Acid, 8μg/mL), ECA (β1,4 Galactose, 20μg/mL), AAL (α1,6 Fucosβ1,N-GlcNAc, 20μg/mL), UEA (α1,2 Fucose, 20μg/mL), GSL-II (terminal GlcNAc, 20 μg/mL), CCA (9-O-acetylated and 4-O-acetylated sialic acid, EY Labs: BA-7201-1, 10μg/mL). Enzymatically deactivated hemagglutinin esterase from mouse hepatitis virus (MHV, 4-O-acetylated sialic acid) and Porcine Torovirus (PToV, 9-O-acetylated sialic acid) fused to human IgG1 Fc, and their non-binding mutants, were produced as previously described57 and used at 1 μg/mL to probe for acetylated sialic acid variants. Streptavidin-peroxidase was then added to bind biotinylated lectins, while mouse anti-human IgG1-perioxidase (Southern Biotech, 9054-05) was used to detect Fc fusion lectins. Most lectins were detected using o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride as a substrate and absorption at 450nm was measured. For the MHV, PToV and CCA lectins, signal was developed using SuperSignal ELISA Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo, 37075) and lumens were measured using the Synergy Neo2 plate reader (BioTek). IL-10 was detected from mouse serum according to manufacturer’s instructions (R&D, DY417) using SuperSignal ELISA Femto Substrate with an assay dynamic range of 3-1600 pg/mL.

LLO neutralization assay

vIgG or pIgG at various dilutions were pre-incubated with LLO toxin (2.5 nM in PBS) on ice in a 96-well plate for 15 min before the addition of 4x106 sheep erythrocytes (Rockland Labs, R406-0050). Triton X-100 (0.05%) and PBS served as positive and negative controls for hemolysis, respectively. Samples were transferred to a spectrophotometer at 37° C and the absorbance (700 nm) was measured at 60 sec intervals for 30 min.

SNA Lectin Fractionation

1.5mL of SNA-agarose (Vector Labs, AL-1303-2) was added to a column (Bio-Rad, #732-6008). Agarose was washed with 10 mL of buffer (20mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, pH 7.2) and then 1mg of vIgG diluted into 500uL total volume added to the column, which was allowed to drain through via gravity. The flow through plus 5mL of wash were collected as the unbound fraction. 3mL of Glycoprotein Eluting Solution (VectorLabs, ES-2100-100) was applied to collect the bound fraction. Both fractions were then concentrated and buffered exchanged to PBS before downstream analysis.

IgG enzyme treatments

Purified IgG was treated with neuraminidase (NEB, P0720L, 1μL per 25μg IgG, pH 5.5) to remove sialic acid and then the enzyme was functionally inactivated by incubation at 55°C for 10 min. IgG was then separated from neuraminidase by size exclusion chromatography (100kDa MWCO) before being resialylated using murine ST6Gal1 (Creative Biomart, St6gal1-7036M, 1μg per 20μg IgG, pH 7.0) plus 2.5mM CMP-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-Neu5Ac, Calbiochem, 5052230001), CMP-glycolylneuraminic acid (CMP-Neu5Gc, Chemily, 98300-80-2) or CMP-9-O-Acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-9-O-Ac-Neu5Ac) as substrate. The latter was produced by custom synthesis with structural conformation verified by NMR and MS with >95% purity among CMP-sialic acid conjugates based on HPLC (BOC Sciences, www.bosci.com). As a control, vIgG without neuraminidase pre-treatment before ST6Gal1 addition of Neu5Ac was included (referred to as vIgGNo-Neur in Fig. 2). IgG N-glycan sialic acid deacetylation was accomplished by treating IgG with sialic acid acetyl esterase (SIAE, Creative Biomart, SIAE-15119M, 1μL per 40μg IgG, pH 8.0). Glycosylation modifying enzyme reactions were performed at 37°C for 20-24 hours, except SIAE-mediated deacetylation which occurred for 42 hours, and success was confirmed by lectin staining. To generate F(ab’)2 fragments, IgG was treated with pepsin (Thermo, 44988) at pH 4.0, 37°C for 3 hours and purified by Protein A and size exclusion chromatography (50kDa MWCO) then buffer-exchanged to PBS. Successful cleavage of Fc was confirmed via mass spectroscopy, lectin blots and ELISA with IgG subtype specific secondary antibodies.

SNA lectin blots

2-4μg of IgG or F(ab’)2 fragments were diluted in Laemmli sample buffer, electrophoresed in 4-20% SDS-PAGE Tris/Glycine gels (Biorad, 4561094) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, IPVH09120) using a semi-dry blotter (Novex). Membranes were blocked in 100% Superblock/TBS (Thermo, 37545) plus 0.05% Tween-20 and then incubated overnight at 4°C with 2μg/mL biotinylated SNA lectin in 10% Superblock/TBS plus 0.05% Tween-20. TBS-T was used to wash membranes. Neutralite Avidin-HRP (Southern Biotech, 7200-05) was used for detection. Lectin blots were developed using SuperSignal West Pico Plus chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo, 34580) and imaged using Image Studio Lite V5.2 on a LI-COR C-DiGit Blot Scanner.

Lm-specific antibody isolation

Serum from virgin or pregnant mice was buffer exchanged into 20mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 150mM NaCl using a HiPrep 26/10 Desalting 53mL column (Cytiva) and run over a HiTrap Protein G HP 1mL column (Cytiva) to capture antibodies. Antibodies were eluted with 100mM glycine pH ~2 into tubes containing sufficient Tris to neutralize the pH. UV-inactivated Lm (UV Stratalinker 2400, Stratagene, 6 min total treatment) was centrifuged at 4,000rpm for 5 min to pellet the bacteria. Then, Lm pellets were resuspended in 20M NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 150mM NaCl. The pellets were washed by centrifuging for another 5 min, pouring off the supernatant, then resuspending with fresh buffer. Bacteria were washed a total of 3 times, then the final pellet from 2-8L of Lm was resuspended with 2.5mL of virgin- or pregnant-derived, Protein G-purified antibodies at ~0.1-0.2 mg/ml. This mixture was incubated for 30 min with gentle shaking at room temperature. The bacteria were again centrifuged for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet containing Lm and Lm-specific antibodies was washed with 10mL of buffer by resuspension, then centrifuged for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded before adding 2.5mL of buffer containing 2M MgCl2 to elute the Lm-specific antibodies from the bacteria. The mixture was incubated with shaking for another 5 min and centrifuged. The supernatant containing Lm-specific antibodies was collected and buffer-exchanged using a HiPrep 26/10 Desalting 53mL column to remove the MgCl2. The antibodies were again purified using a HiTrap Protein G HP 1mL column, then buffer exchanged back into 20mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 150mM NaCl during concentration of the antibodies for downstream applications.

Mass spectroscopy

Water (Honeywell), acetonitrile (ACN;Fisher) and formic acid (FA; Sigma) were all of LC-MS grade. All other chemicals were of laboratory analytical reagent grade. Samples were reduced, alkylated, then digested into peptides. A solution containing ~20μg of the protein solution in 50mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4) was reduced in a solution of 5mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 45°C for 45 min, a solution of iodoacetamide (IAA) was added to bring the solution to 15mMand then incubated at room temperature in the dark for 45 min. A second aliquot of DTT was then added to the solution to quench the remaining IAA. Trypsin or Chymotrypsin (Promega, Sequencing Grade) was added to the solution and allowed to digest for 16 hours. The digestion was stopped by briefly heating the solution to 100°C for 5 min before cooling. The digested material was then injected for LC-MS.

LC-MS/MS was performed on an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) coupled to a Ultimate RSLCnano 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) and equipped with an nanospray ion source. Prepared samples were injected to the separation column (Acclaim PepMap 100 75μm x 15cm). The separation was performed in a linear gradient from low to high acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. Mass spectrometry was carried out in the positive ion mode where a full MS spectrum was collected at high resolution (120,000) and data dependent MS/MS scans of the highest intensity peaks following higher-energy C-trap dissociation (HCD) fragmentation were collected in the Orbitrap. HCD fragments corresponding to sialic acid oxonium ions were then subsequently fragmented a second time with electron-transfer higher-energy collision dissociation (EThcD) fragmentation. The LC-MS/MS data were analyzed using Byonic (version 4.0) software search and glycopeptide annotations were screened manually for b and y ions, glycan oxonium ion, and neutral losses. Quantification of peak intensities were calculated manually with the instrument software (Xcalibur, version 4.2) based on deconvoluted spectra. Manual sorting of MS/MS fragmentation to search for oxonium ions consistent with acetyl-glycolylneuraminic acid (Acetyl-Neu5Gc or Neu5Gc,Ac) was also conducted with the instrument software using a 5ppm range of mass error, which is consistent with MS/MS data collected in the Orbitrap for this instrument.

RNA isolation and qPCR

For mice, spleen RNA was extracted from virgin or pregnant females at late gestation (E18-20). For humans, informed consent was obtained prior to collection of peripheral blood specimens from study volunteers. Specimens from pregnant (12-32 weeks of gestation) women were collected through prospective studies investigating pregnancy-associated immunological changes in collaboration with Dr. Michal A. Elovitz (University of Pennsylvania), and specimens from non-pregnant volunteers provided in a de-identified fashion through Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Translational Core Laboratories Cell Processing core under institutional review board (IRB) approved protocols (University of Pennsylvania IRB protocol 833333; CCHMC IRB protocols 2020-991). Mononuclear cells were freshly isolated over Ficoll-Hypaque gradients. Frozen buffy coats from non-pregnant and pregnant patients were thawed and total RNA isolated using the RNAaqueous-4PCR kit (Invitrogen, AM1914). cDNA synthesis was performed using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, N808234) with an Oligo-d(T)16 nucleotide reverse transcription primer. qPCR reactions were set up using the Taq Man Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4444556). qPCR was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using exon-spanning TaqMan probes (Thermo Fischer) for mouse β-Actin (Mm04394036_g1), mouse SIAE (Mm00496036_m1), human RPL13A (Hs03043885_g1), or human SIAE (Hs00405149_m1). SIAE gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene and fold increase calculated using the 2ΔΔCt method.

In vivo antibody blockade

To block receptors in vivo, 3-day old mouse pups were injected with one of the following purified monoclonal antibodies (BioXcell) or appropriate isotype controls: anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (2.4G2, 100μg/pup), anti-mouse CD22 (Cy34.1, 100μg/pup), anti-mouse IL-10R (1B1.3A, 100μg/pup). Blocking antibodies were given simultaneously with anti-Lm antibodies, and neonatal mice were infected with Lm the following day.

In vitro B cell stimulation assay

Neonatal spleens from IL10-eGFP mice were pressed between sterile glass slides to obtain a single cell suspension, RBCs were lysed, and then cells were filtered over nylon mesh to remove debris. UV-inactivated Lm (20μg/mL final concentration) or the TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4 (InvivoGen, 100ng/mL) were preincubated with IgG from naïve mice, vIgG or pIgG (250μg/mL) for 1hr at RT. 106 splenocytes were then added to individual wells of a 96-well plate and UV-inactivated Lm + IgG were added. Anti-mouse CD22 (clone Cy34.1), or mouse IgG1 isotype control, was included in some wells at 2μg/mL. Incubation proceeded at 37°C for 20hr before analysis of GFP expression via flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies specific for mouse cell surface antigens were purchased from BioLegend. The following antibodies (clone, cat #,) were used at 1:200 final dilution: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2, 103211), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, 100409), anti-CD8a (53-6.7, 100709), anti-CD11b (M1/70, 101209), anti-CD11c (N418, 117316), anti-CD45.2 (104, 109821), anti-CD22 (OX-97, 126109/126105), anti-CD5 (53-7.3, 100607), anti-IgM (RMM-1,406513). Single cell suspension of neonatal splenocytes was first stained with Fixable Viability Dye (eBiosciences, 65-0863-14) and then stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies in the presence of Fc block (anti-CD16/32). Data were acquired on a BD FACS Canto using BD FACS Diva software (version 9) and analyzed using FlowJo (version 10).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The number of individual animals used per group are described in each individual figure panel or shown by individual data points that represent the results from individual animals. Statistical tests were performed using Prism (GraphPad) software. The unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compared differences between two groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons was used to evaluate experiments containing more than two groups. Differences in survival between groups of mice were compared using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Limits of detection for each assay are denoted by a dotted horizontal line.

Graphics

Graphical depictions including illustrations and summary model were created using content from BioRender.com

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: Pregnancy enables antibody mediated protection against Lm infection.

(a, b) Bacterial burden (a) and anti-Lm IgG titer (b) in neonatal mice infected with virulent Lm born to WT naive mice or mice preconceptual primed with ΔActA Lm once or twice 2 weeks apart. (c) C. albicans fungal burden in neonatal mice born to WT female mice primed with attenuated ΔActA Lm one week prior to mating or naive control mice. Pups were infected with virulent C. albicans 3 days after birth, with enumeration of pathogen burden 48 hours post-infection. (d) Bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection with virulent Lm in adult WT, μMT−/− or CD8−/− mice with or without ΔActA Lm priming 4 weeks prior. (e) Anti-Lm IgG titer in adult CD8−/− mice 3 days after primary Lm infection compared with secondary challenge of ΔActA Lm-primed virgin female mice or preconceptually ΔActA Lm-primed CD8−/− female mice 3 weeks post-partum. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 2:

Anti-Lm antibodies acquire protective function during pregnancy through maternal FcγR-expressing cells. (a) Anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice 72 hours after virulent Lm infection that were transferred sera from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin (vSera) or sera from late gestation/early post-partum (pSera) mice. (b) Cross-fostering schematic and anti-Lm IgG titer in each group of neonatal mice 72 hours after virulent Lm infection. (c) Anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice nursed by WT, μMT−/−, or FcRγ−/− mice administered vSera on the day of delivery and 3 days later. (d) Anti-Lm IgG titers and bacterial burdens after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice administered vSera that had been incubated with splenocytes from virgin or pregnant (E18) WT or FcRγ−/− mice for 48 hours. Pups were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, 24 hours after antibody transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 3: Lm-specific IgG titer, subclass distribution, neutralization efficiency, and lectin staining profile comparisons in virgin compared with pregnant mice.

(a) IgG titers against UV-inactivated Lm bacteria or purified LLO protein for WT female pregnant/postpartum mice preconceptually primed with ΔActA Lm, ΔActA Lm-primed virgin mice, or naive control mice. (b) OD450 for each antibody isotype or subclass in sera from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin or pregnant mice. All sera diluted 1:100. Background subtracted from staining using naive sera. (c) LLO-induced hemolysis of sheep erythrocytes in media containing anti-Lm IgG from virgin (vIgG) or late gestation/early postpartum pregnant (pIgG) mice. (d) Relative vIgG and pIgG binding to each lectin with defined carbohydrate-specificity for LLO-specific IgG. (e,f) SNA-agarose fractionation of sialylated (SNA Bound) compared with non-sialylated (SNA Unbound) anti-Lm vIgG. SNA lectin staining confirmed successful separation (e). Lm- and LLO-specific IgG was titered from each fraction (f). (g, h) Anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice transferred each type of enzymatically-treated pIgG (g). Lectin staining to confirm de- and resialylation of pIgG: SNA signal indicates presence of terminal sialic acid and ECA signal indicates presence of galactose uncovered by terminal sialic acid removal (h). (i-k) Anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice transferred glycoengineered vIgG (i). SNA and ECA Lectin staining to confirm de- and resialylatoin of vIgG with sialic acid variants (j). PToV virolectin probe for 9-O-acetylated sialic acid and PToV with mutated binding site (nonbinder) demonstrating specificity for vIgG resialylated with each sialic acid variant or deacetylated with SIAE treatment (k). Representative data from at least 2-3 independent experiments (a-f) or combined data from 3 independent experiments with 3-5 mice per group per experiment (g-k) are shown. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 4: Deacetylated sialic acid on Lm-specific IgG enables antibody-mediated protection.

(a, b) Anti-Lm IgG titer 72 hours post-infection (a) and survival in neonatal mice transferred SIAE- or mock-treated anti-Lm IgG from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin mice (b). (c, d) Bacterial burden (c) and anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice infected with virulent Lm transferred SIAE- or mock-treated anti-Lm IgG from preconceptual ΔActA Lm-primed late gestation/early postpartum mice (d). (e) CCA lectin detection of 9-O-Acetyl-Neu5Gc on LLO-specific IgG obtained 72 hours after transferring sera from virgin ΔActA Lm-primed mice (vSera) to WT or SIAE KO postpartum recipients on the day of delivery and 3 days later (top). Anti-Lm IgG titer in neonatal mice nursed by these females 72 hours post-infection with virulent Lm (bottom). (f) Anti-Lm IgG titers (top) and bacterial burdens (bottom) in virulent Lm infected neonatal mice nursed by WT or ST6Gal1 KO mice administered vSera as described in panel (e). Pups were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, 24 hours after antibody transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons (a, c, d, f), or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (b). Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 5: Oxonium ion searches for sialic acid modifications.

(a) Schematic for purification of Lm-specific IgG from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin and pregnant mice for mass spectroscopy analysis. (b) Oxonium ion m/z used to search for sialic acid variants. Diagnostic ions were filtered through the MS/MS spectra to select glycopeptides containing Acetyl-Neu5Gc (Neu5Gc,Ac). Example spectra shown for virgin Lm-specific IgG. (c) MS/MS fragmentation for the low mass region (150-500) demonstrating sialic acid variants. All presented m/z are z=1. Experiment was performed in triplicate with representative data shown.

Extended Data Fig. 6: Glycoforms on IgG2 Fc conserved region N-glycans do not contain acetylated sialic acid.

Lm-specific IgG from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin and pregnant mice was subjected to trypsin or chymotrypsin digestion and then LC-MS/MS analysis. (a) Representative MS/MS fragmentation from the conserved N-linked glycosylation site at position 183 on the Fc region of IgG2b/c (glycopeptide EDYNSTIR). (b) Extracted ion chromatograph of EDYNSTIR with the observed sialic acid (Neu5Gc) glycoforms and the absence of Acetyl-Neu5Gc, which was confirmed for the entire length of the LC-MS run. (c, d) All glycoforms with observed masses for N-glycans on the conserved Fc region of IgG2b/c for virgin (c) and pregnant (d) Lm-specific IgG. Experiment was performed in triplicate with representative (a, b) and combined (c, d) data shown.

Extended Data Fig. 7: Acetylated sialic acid localizes to the IgG Fab variable region.

(a) Extracted ion chromatograph showing m/z corresponding to Acetyl-Neu5Gc (Neu5Gc,Ac) and m/z of the same glycopeptides containing Neu5Gc. Examples of two individual glycopeptides are shown. (b) Representative MS/MS fragmentation of glycopeptide N1E2S1L1Y1T1A2I1K1 demonstrating presence of Acetyl-Neu5Gc (Neu5Gc,Ac). (c) For Fab glycans, the exact amino acid position and sequence are unknown, and shown are potential amino acid compositions given the observed mass size. Experiment was performed in triplicate with representative (a, b) and combined (c) data shown .

Extended Data Fig. 8: Fc-mediated functions are dispensable for antibody-mediated protection against Lm.

(a) Presence of IgG heavy (H) and light (L) chains or IgG2b Fc for pF(ab’)2 confirming efficient Fc removal after pepsin digestion. (b) Lectin staining for pF(ab’)2 compared with full-length pIgG for anti-LLO antibodies showing Fab glycosylation. SNA binds α2,6-linked sialic acid residues, while AAL binds α1,6-linked fucose. (c) SNA lectin blot comparing full-length IgG under reducing conditions to separate heavy and light chains, with purified F(ab’)2 fragments under non-reducing conditions, demonstrating preserved SNA lectin staining. (d) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred sera from preconceptual ΔActA Lm-primed pregnant/postpartum (pSera) or naive control mice, along with anti-CD16/32 blocking or isotype control antibodies. (e, f) Bacterial burden after virulent Lm infection in neonatal WT, complement C1q-deficient mice (e) or complement C3-deficient (f) transferred pSera or sera from naive mice. Pups were infected with virulent Lm 3-4 days after birth, 24 hours after antibody transfer, with enumeration of bacterial burden 72 hours post-infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Gel is representative of results from 3 independent experiments each with similar results (c). Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 9: Deacetylated anti-Lm antibodies protect via CD22-mediated suppression of B cell IL-10 production.

(a) Anti-Lm antibody titers in neonatal WT or CD22-deficient mice transferred sera from ΔActA Lm-primed pregnant/postpartum (pSera) or naive mice. (b, c) Bacterial burden (b) or anti-Lm IgG titers (c) after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred pSera or sera from naive mice along with anti-CD22 blocking or isotype control antibodies. (d, e) Bacterial burden (d) or anti-Lm IgG titers (e) after virulent Lm infection in neonatal mice transferred vIgG glycoengineered to express Neu5Ac. Neonates received either isotype control mAb or anti-CD22 mAb, or were CD22 deficient. (f, g) Bacterial burden (f) and anti-Lm IgG titers (g) after virulent Lm infection in WT or CD19−/− neonatal mice transferred vSera or sera from naive mice. (h) Anti-Lm IgG titers in neonatal WT or μMT−/− mice transferred sera from ΔActA Lm-primed virgin (vSera) or pSera. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments each with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons. Dotted lines, limit of detection.

Extended Data Fig. 10: Deacetylated anti-Lm antibodies protect via CD22-mediated suppression of B cell IL-10 production.

(a) Representative FACS plots showing GFP expression by B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocytes 72 hours after virulent Lm infection in neonatal IL10-eGFP reporter mice administered vSera or pSera along with anti-CD22 neutralizing or isotype control antibodies, compared with no infection control mice. (b) Representative FACS plots showing GFP expression by B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocytes from IL10-eGFP reporter mice stimulated with UV-inactivated Lm for 20 hours in the presence of vIgG or pIgG plus anti-CD22 neutralizing antibody or isotype control. (c) GFP expression by B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocytes from IL10-eGFP reporter mice after UV-Lm stimulation plus anti-CD22 neutralizing antibody or isotype control without anti-Lm IgG. (d) GFP expression by B220+IgM+CD5+ splenocytes from IL10-eGFP reporter mice stimulated with the TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4 in the presence of vIgG or pIgG. (e) Anti-Lm antibody titers in neonatal mice transferred vSera or sera from naive mice along with anti-IL10 receptor blocking or isotype control antibodies. (f) Model of pregnancy-induced deacetylation of anti-Lm antibodies that unleash their protective function by overriding IL-10 production by B10 cells via CD22. Each symbol represents the data from cells in an individual well under unique stimulation conditions combined from 4-5 independent experiments (c, d), or individual mice (e) with graphs showing data combined from at least 2 independent experiments with 3-5 mice per group per experiment. Bar, mean ± standard error. P values between key groups are shown as determined by one-way ANOVA adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

J.J.E. is supported by NIH grant F32AI145184 and the Child Health Research Career Development Award Program through K12HD028827. S.S.W. is supported by DP1AI131080, R01AI120202, R01AI124657 and U01AI144673, the HHMI Faculty Scholar’s Program (grant #55108587), Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the March of Dimes Foundation Ohio Collaborative. A.L.S is supported by NIH grant T32DK007727. P.A. is supported by R24GM137782 at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center. The Eclipse mass spectrometer used in the glycan analysis was supported by GlycoMIP, a National Science Foundation Materials Innovation Platform funded through Cooperative Agreement DMR-1933525. A.B.H. is supported by R01GM094363 and R01AI162964. We thank Fred D. Finkelman for helpful discussions; Michal A. Elovitz, Carolyn Lutzko, Lorraine Ray, Megan Reynolds, Lisa Trump-Durbin, and the CCHMC Cell Processing core for providing de-identified human peripheral blood specimens.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Competing Interests

A patent on antibody sialic acid modification has been filed by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital with J.J.E. and S.S.W. as inventors (PCT/US2022/018847). A.B.H. has equity in Chelexa BioSciences, LLC and in Hoth Therapeutics, Inc., and he serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Hoth Therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed in this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). Source data are provided with this paper. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD033357.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins FM Cellular antimicrobial immunity. CRC Crit Rev Microbiol 7, 27–91, doi: 10.3109/10408417909101177 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackaness GB Resistance to intracellular infection. J Infect Dis 123, 439–445, doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.4.439 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht M & Arck PC Vertically Transferred Immunity in Neonates: Mothers, Mechanisms and Mediators. Front Immunol 11, 555, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00555 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins JR & Bakardjiev AI Pathogens and the placental fortress. Curr Opin Microbiol 15, 36–43, doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.11.006 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surolia I et al. Functionally defective germline variants of sialic acid acetylesterase in autoimmunity. Nature 466, 243–247, doi: 10.1038/nature09115 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark EA & Giltiay NV CD22: A Regulator of Innate and Adaptive B Cell Responses and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol 9, 2235, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02235 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahajan VS & Pillai S Sialic acids and autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev 269, 145–161, doi: 10.1111/imr.12344 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kollmann TR, Marchant A & Way SS Vaccination strategies to enhance immunity in neonates. Science 368, 612–615, doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9447 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chávez-Arroyo A & Portnoy DA Why is Listeria monocytogenes such a potent inducer of CD8+ T-cells? Cell Microbiol 22, e13175, doi: 10.1111/cmi.13175 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radoshevich L & Cossart P Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 32–46, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.126 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchant A et al. Maternal immunisation: collaborating with mother nature. Lancet Infect Dis 17, e197–e208, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30229-3 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fouda GG, Martinez DR, Swamy GK & Permar SR The Impact of IgG transplacental transfer on early life immunity. Immunohorizons 2, 14–25, doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1700057 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufmann SH, Hug E & De Libero G Listeria monocytogenes-reactive T lymphocyte clones with cytolytic activity against infected target cells. J Exp Med 164, 363–368, doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.363 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop DK & Hinrichs DJ Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. The influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J Immunol 139, 2005–2009 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mielke ME, Ehlers S & Hahn H T-cell subsets in delayed-type hypersensitivity, protection, and granuloma formation in primary and secondary Listeria infection in mice: superior role of Lyt-2+ cells in acquired immunity. Infect Immun 56, 1920–1925, doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1920-1925.1988 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruhns P & Jönsson F Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol Rev 268, 25–51, doi: 10.1111/imr.12350 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony RM, Wermeling F & Ravetch JV Novel roles for the IgG Fc glycan. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1253, 170–180, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06305.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Bovenkamp FS, Hafkenscheid L, Rispens T & Rombouts Y The Emerging Importance of IgG Fab Glycosylation in Immunity. J Immunol 196, 1435–1441, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502136 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traving C & Schauer R Structure, function and metabolism of sialic acids. Cell Mol Life Sci 54, 1330–1349, doi: 10.1007/s000180050258 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langereis MA et al. Complexity and Diversity of the Mammalian Sialome Revealed by Nidovirus Virolectins. Cell Rep 11, 1966–1978, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.044 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srivastava S et al. Development and applications of sialoglycan-recognizing probes (SGRPs) with defined specificities: exploring the dynamic mammalian sialoglycome. bioRxiv, 2021.2005.2028.446202, doi: 10.1101/2021.05.28.446202 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravindranath MH, Higa HH, Cooper EL & Paulson JC Purification and characterization of an O-acetylsialic acid-specific lectin from a marine crab Cancer antennarius. J Biol Chem 260, 8850–8856 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crocker PR, Paulson JC & Varki A Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 255–266, doi: 10.1038/nri2056 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krištić J et al. Profiling and genetic control of the murine immunoglobulin G glycome. Nat Chem Biol 14, 516–524, doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0034-3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai S et al. Transcriptional profiling of human placentas from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia reveals disregulation of sialic acid acetylesterase and immune signalling pathways. Placenta 32, 175–182, doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.11.014 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medzihradszky KF, Kaasik K & Chalkley RJ Characterizing sialic acid variants at the glycopeptide level. Anal Chem 87, 3064–3071, doi: 10.1021/ac504725r (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melo-Braga MN, Carvalho MB, Emiliano MC, Ferreira & Felicori LF New insights of glycosylation role on variable domain of antibody structures bioRxiv, 10.1101/2021.04.11.439351 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sjoberg ER, Powell LD, Klein A & Varki A Natural ligands of the B cell adhesion molecule CD22 beta can be masked by 9-O-acetylation of sialic acids. J Cell Biol 126, 549–562, doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.549 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blixt O, Collins BE, van den Nieuwenhof IM, Crocker PR & Paulson JC Sialoside specificity of the siglec family assessed using novel multivalent probes: identification of potent inhibitors of myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Biol Chem 278, 31007–31019, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304331200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brinkman-Van der Linden EC et al. Loss of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in human evolution. Implications for sialic acid recognition by siglecs. J Biol Chem 275, 8633–8640, doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8633 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tedder TF B10 cells: a functionally defined regulatory B cell subset. J Immunol 194, 1395–1401, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401329 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanaba K et al. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity 28, 639–650, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horikawa M et al. Regulatory B cell (B10 Cell) expansion during Listeria infection governs innate and cellular immune responses in mice. J Immunol 190, 1158–1168, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201427 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CC & Kung JT Marginal zone B cell is a major source of Il-10 in Listeria monocytogenes susceptibility. J Immunol 189, 3319–3327, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201247 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu D et al. IL-10-Dependent Crosstalk between Murine Marginal Zone B Cells, Macrophages, and CD8α. Immunity 51, 64–76.e67, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.011 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres D et al. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for optimal control of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect Immun 72, 2131–2139, doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2131-2139.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edelson BT, Cossart P & Unanue ER Cutting edge: paradigm revisited: antibody provides resistance to Listeria infection. J Immunol 163, 4087–4090 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Séïté JF et al. IVIg modulates BCR signaling through CD22 and promotes apoptosis in mature human B lymphocytes. Blood 116, 1698–1704, doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261461 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adachi T et al. CD22 serves as a receptor for soluble IgM. Eur J Immunol 42, 241–247, doi: 10.1002/eji.201141899 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller J et al. CD22 ligand-binding and signaling domains reciprocally regulate B-cell Ca2+ signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 12402–12407, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304888110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawasaki N, Rademacher C & Paulson JC CD22 regulates adaptive and innate immune responses of B cells. J Innate Immun 3, 411–419, doi: 10.1159/000322375 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casadevall A Antibody-based vaccine strategies against intracellular pathogens. Curr Opin Immunol 53, 74–80, doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.04.011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatta Y et al. Identification of the gene variations in human CD22. Immunogenetics 49, 280–286, doi: 10.1007/S002510050494 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunter CD et al. Human Neuraminidase Isoenzymes Show Variable Activities for 9-O-Acetyl-sialoside Substrates. ACS Chem Biol 13, 922–932, doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00952 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varki A, Hooshmand F, Diaz S, Varki NM & Hedrick SM Developmental abnormalities in transgenic mice expressing a sialic acid-specific 9-O-acetylesterase. Cell 65, 65–74, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90408-q (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzuto G et al. Establishment of fetomaternal tolerance through glycan-mediated B cell suppression. Nature 603, 497–502, doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04471-0 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fowler KB et al. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med 326, 663–667, doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203053261003 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M & Britt WJ Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med 344, 1366–1371, doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441804 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown ZA et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA 289, 203–209, doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.203 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freitag IGR et al. Seroprevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in HIV infected pregnant women from Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis 25, 101635, doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101635 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hennet T, Chui D, Paulson JC & Marth JD Immune regulation by the ST6Gal sialyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 4504–4509, doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4504 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haeussler M et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol 17, 148, doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1012-2 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Way SS, Kollmann TR, Hajjar AM & Wilson CB Cutting edge: protective cell-mediated immunity to Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of myeloid differentiation factor 88. J Immunol 171, 533–537, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.533 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elahi S et al. Immunosuppressive CD71+ erythroid cells compromise neonatal host defence against infection. Nature 504, 158–162, doi: 10.1038/nature12675 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shao TY et al. Commensal Candida albicans Positively Calibrates Systemic Th17 Immunological Responses. Cell Host Microbe 25, 404–417 e406, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.004 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner LH et al. Preconceptual Zika virus asymptomatic infection protects against secondary prenatal infection. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006684, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006684 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wasik BR et al. Distribution of O-Acetylated Sialic Acids among Target Host Tissues for Influenza Virus. mSphere 2, doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00379-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed in this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). Source data are provided with this paper. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD033357.