Abstract

Background:

Data on the impact of residual peri-device leak following left atrial appendage occlusion [LAAO] are limited.

Objective:

to explore the association of peri-device leak with adverse clinical events.

Methods:

We queried the NCDR-LAAO Registry to identify patients undergoing LAAO between January-1st, 2016, and December-31st, 2019. Patients were classified according to leak size on 45+/−14 days echocardiography: (0mm, no leak; >0–5mm, small leak; >5mm, large leak).

Results:

A total of 51,333 patients were included, of whom 37,696 (73.4%) had no leak, 13,258 (25.8%) had small leaks, and 379 (0.7%) had large leaks. The proportion of patients on warfarin at 45-day was higher in the large vs. small or no leak cohort (44.9% vs. 34.4% and 32.4%, respectively, p<0.001). At 6- and 12-month, anticoagulant utilization decreased but remained more frequent in patients with large leaks. Thromboembolic events were uncommon in all groups. However, compared with patients with no leak, those with small leaks had slightly higher odds of stroke/TIA/systemic embolization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.152, 95%CI 1.025–1.294), major bleeding (HR 1.11, 95%CI 1.029–1.120), and any major adverse events (HR 1.102, 95%CI 1.048–1.160). There were no significant differences in adverse events between patients with large leaks and patients with small or no leaks.

Conclusion:

Small (0–5mm) leaks after LAAO were associated with modestly higher incidences of thromboembolic and bleeding events; large leaks (>5mm) were not associated with adverse events although higher proportions of these patients were maintained on anticoagulation. Newer devices with improved seal might mitigate the events associated with residual leaks.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, left atrial appendage, peri-device leak, ischemic stroke

Condensed Abstract:

We queried the NCDR LAAO Registry to compare post-LAAO clinical outcomes stratified by the size of residual leak at 45-day TEE. Peri-device leak was absent in 37,696 (73.4%), small in 13,258 (25.8%), and large in 379 (0.7%). Compared with no leak, patients with small leaks had slightly higher odds of stroke/transient ischemic attacks/systemic embolization (aHR 1.152, 95%CI 1.025–1.294), major bleeding (HR 1.11, 95%CI 1.029–1.120), and any major adverse events (HR 1.102, 95%CI 1.048–1.160). Large leaks were not associated with higher adverse events although a higher proportion of those patients were maintained on anticoagulation at 45-day, 6-month, and 1-year.

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) has emerged as an effective strategy for stroke prevention in selected patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). The safety and efficacy of LAAO has been established through 3 randomized trials and many observational studies (1–3). Nonetheless, certain issues with LAAO remain open, including the incidence of peri-device leak after the closure procedure in real world clinical practice and the outcomes associated with leaks (4,5). Although the incidence of peri-device leak in clinical trials has decreased overtime owing to the growing experience with the procedure and the improved seal with 2nd generation closure devices, the management of post-LAAO leaks remains a clinical conundrum (5–12). This is partially due to the uncertainty about the definition of clinically significant leaks. Current guidelines use an arbitrary cutoff of >5mm to classify leaks as significant vs. non-significant, but cut-offs of >3, ≥3, or ≥5 mm have been also suggested in the literature (10). In addition, data on the association between peri-device leaks and thromboembolic events have been sparse and often contradictory (10–13). Hence, we sought to utilize the largest available LAAO database (NCDR LAAO Registry) to address the open questions surrounding peri-device leaks after LAAO (14). We hypothesized that small leaks (<5 mm) after LAAO are not associated with adverse events during midterm follow up.

Methods:

Data Source:

Participants in this study were patients who were enrolled in the NCDR LAAO Registry. The LAAO Registry has been previously described (14). In brief, the LAAO Registry was launched in 2015 as a collaborative effort between the American College of Cardiology, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Society for Coronary Angiography and Interventions, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and Boston Scientific (14). Since April 1, 2016, US centers performing LAAO were required to submit data on LAAO procedures into this registry to qualify for Medicare reimbursement and most centers submit all LAAO cases. Demographic and clinical data, device implant information, adjudicated in-hospital adverse events during the index hospitalization, discharge medications, and follow-up clinical data were collected using standardized definitions. Data were submitted by participating hospitals using a rigorous data reporting process to ensure complete and accurate submissions. The NCDR programs use a multistage data quality process, including quality checks on submitted data, outlier analysis, and medical record audits. The audit process is conducted annually at randomly selected sites and included 20 sites during the last audit (approximately 5% of sites), with a 93.3% agreement rate between registry-reported data compared with source document review and 100% agreement between billing compared with registry-reported data (14).

Study Population:

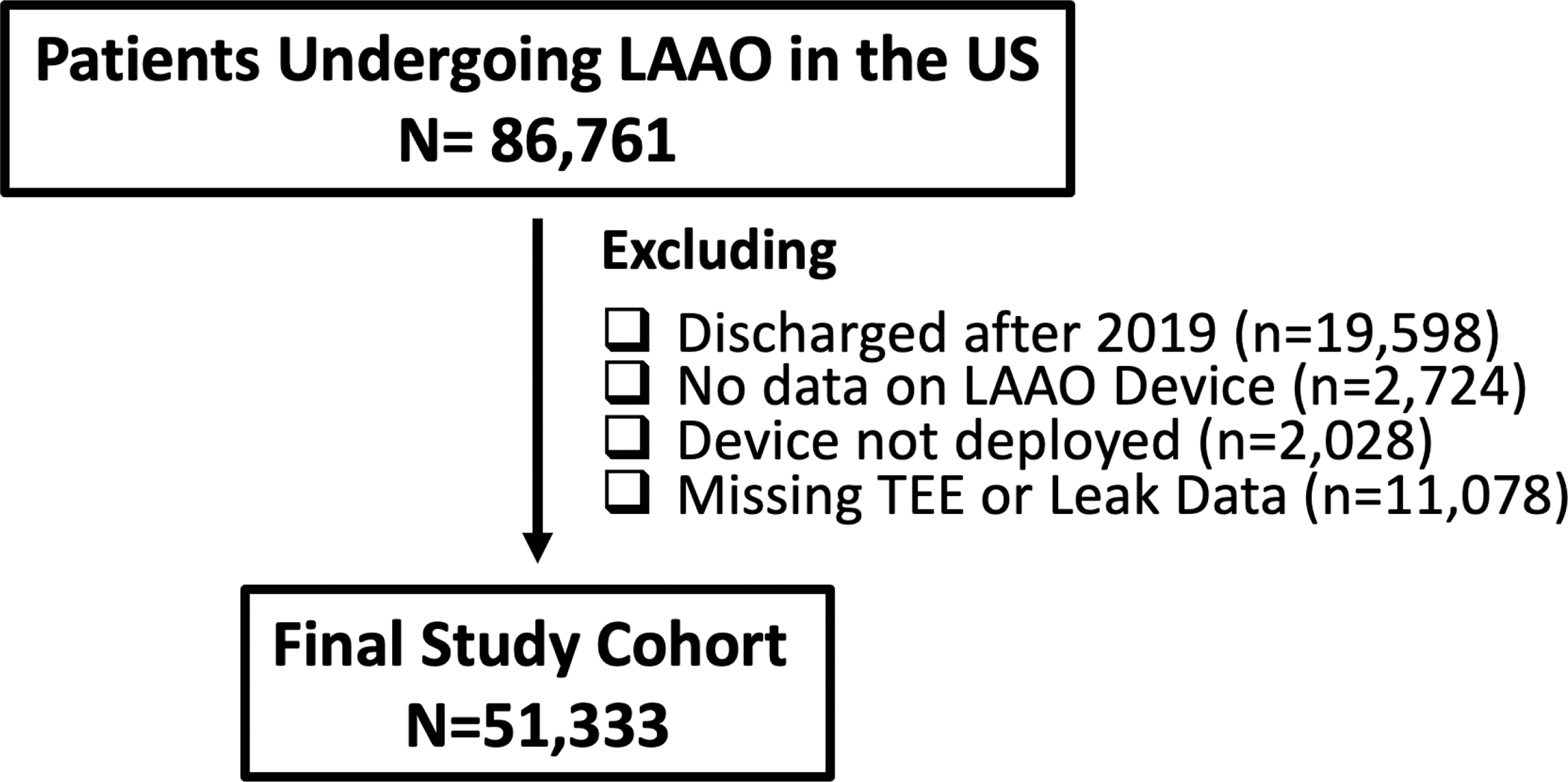

A total of 86,761 patients included in the LAAO Registry were initially screened. We excluded cases not performed between January 2016 and December 2019, those with missing information on device implant, those who did not have an LAAO device implanted, and those who did not undergo transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) in the time window of 45 days +/− 14 days. After these exclusions, 51,333 patients represented the final study cohort (Figure 1).

Figure-1.

Study Flow Chart

Outcomes:

We stratified the study’s population according to their peri-device leak size as reported on 45-day imaging (0 mm ‘no leak cohort’, 1–5 mm ‘small leak cohort’, and >5 mm ‘large leak cohort). While the LAAO registry does not specify how peri-device leaks should be measured, the instruction for use of the Watchman device is usually utilized to guide leak measurements in clinical practice (color Doppler assessment is performed from the device edge to the LAA border at the following approximate TEE angles (0°,45°, 90° and 135°) to measure any residual leak around the device into the LAA).We compared baseline characteristics and antithrombotic medications at discharge, 45-day, 6-month, and 1-year between the 3 groups. The study end points included: (A) A composite of stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), or systemic embolization (SE); (B) Ischemic stroke; (C) Major bleeding defined as access bleeding or hematoma, gastrointestinal bleeding, retroperitoneal bleeding, other non-intracranial bleeding or hemothorax requiring hospitalization and/or causing >2 gram/deciliter decrease in hemoglobin and/or requiring transfusion; (D) Death, and (E) Major adverse event (MAE) which included death; cardiac arrest; ischemic, hemorrhagic or undetermined stroke; TIA; SE; major bleeding; major vascular complication (fistula or pseudoaneurysm requiring intervention), myocardial infarction, pericardial effusion requiring intervention, or device embolization. Data definitions are provided in Supplementary Table-1. These outcomes measures and definitions have been used in prior studies utilizing the NCDR LAAO Registry (14,15). Secondary analyses of the primary endpoint (stroke, TIA, or SE) were also performed comparing (a) patients with any leak vs. those no leak; and (b) comparing patients with >0 but <3mm leaks, 3–5 mm leaks, and >5 mm leaks with patients with no leaks.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS institute; Cary, NC). Baseline demographic and clinical factors are presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and median values and interquartile ranges or mean (SD) values for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test or the t test as appropriate. Missing continuous variables were imputed with the overall median value. For missing categorical variables, the most common category of each variable was imputed.

Follow up clinical events were reported using 2 different methods: First, as a cumulative incidence rate (CIR), and second: as a time to event rate. The total patient/year is calculated by total follow-up days divided by 365, and the CIR is calculated by total counts (numbers of indicators during follow-up visits including death indicator) within 425 days, then divided by total patient years. For example, if a patient had any MAE in his/her 45-day and 180-day follow-up visit, then the number of indicators is 2. However, a single event would have not counted twice, and this is confirmed by the rigorous annual audit process in the LAAO registry. For the time to event rate analyses, we used the Kaplan Meier method to calculate the probability of event-free survival at maximum follow-up. To adjust for differences in baseline characteristics, we built univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. Variables included in the univariate model included race, type of atrial arrythmia, diabetes, history of stroke, history of TIA, fall risk, prior intracranial bleeding, labile international normalized ratio, abnormal liver function, coronary artery disease, pulse, platelets <50,000, albumin level, Creatinine level, CHA2DS2 VASC score components, and antiplatelets/anticoagulants regimen on discharge. All variables with p value <0.10 in the univariate model were included in the multivariate model. The reference group was those with no leak. Hazard ratios [HR] were reported with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Statistical significance was inferred at P≤.05. Yale University Human Investigation Committee approved analysis of this limited dataset derived from the LAAO Registry with waiver of informed consent.

Results:

Baseline clinical profile:

A total of 51,333 patients who underwent LAAO and had a TEE at 45 days +/− 14 days were included in the study, of whom 41.7% were females, and 93.1% were of White race. No peri-device leak was reported in 37,696 patients (73.4%) on 45-day follow up imaging, while 13,258 (25.8%) had small leaks (>0–5 mm), and only 379 (0.7%) had large leaks (>5 mm). Median CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.8 (IQR=1.5), 4.9 (1.5), and 4.9 (1.5) among patients with no, small, and large peri-device leaks, respectively. The corresponding median HAS BLED scores in the 3 groups were 3.0 (IQR=1.1), 3.0 (1.1), and 3.0 (1.1), respectively. There were small but statistically significant differences with regards to demographic, clinical risk factors and hospital characteristics between the groups (Table 1).

Table-1.

Baseline Characteristic of the Study Cohort

| Baseline Characteristic | Leak= 0 mm (N=37,696) | Leak= >0–5 mm (N=13,258) | Leak >5 mm (N= 379) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 22135 (58.7%) | 7678 (57.9%) | 235 (62.0%) | 0.102 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 35207 (93.4%) | 12241 (92.3%) | 347 (91.6%) | <.0001 |

| Black | 1634 (4.3%) | 658 (5.0%) | 21 (5.5%) | 0.007 |

| Asian | 493 (1.3%) | 228 (1.7%) | 7 (1.8%) | 0.002 |

| Hispanic | 1297 (3.5%) | 387 (3.0%) | 15 (4.0%) | 0.014 |

| Insurance payer | ||||

| Private | 23397 (62.1%) | 8561 (64.6%) | 239 (63.1%) | <.0001 |

| Medicare | 32262 (85.6%) | 11471 (86.5%) | 328 (86.5%) | 0.027 |

| Medicaid | 1896 (5.0%) | 664 (5.0%) | 18 (4.7%) | 0.966 |

| State-Specific plan | 293 (0.8%) | 91 (0.7%) | 6 (1.6%) | 0.105 |

| Other | 1799 (4.8%) | 546 (4.1%) | 19 (5.0%) | 0.008 |

| Patient Risk Factors | ||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score; median (IQR) | 4.8 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.5) | <.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 13794 (36.6%) | 5174 (39.0%) | 126 (33.3%) | <.0001 |

| NYHA Class I | 3724 (9.9%) | 1338 (10.1%) | 29 (7.7%) | 0.260 |

| NYHA Class II | 6399 (17.0%) | 2452 (18.5%) | 61 (16.1%) | 0.0003 |

| NYHA Class III | 2753 (7.3%) | 1013 (7.6%) | 29 (7.7%) | 0.434 |

| NYHA Class IV | 169 (0.4%) | 59 (0.4%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.972 |

| Hypertension | 34773 (92.3%) | 12225 (92.3%) | 358 (94.5%) | 0.281 |

| Diabetes | 14299 (37.9%) | 4924 (37.2%) | 130 (34.3%) | 0.109 |

| Stroke | 9069 (24.1%) | 3415 (25.8%) | 104 (27.5%) | 0.000 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 5141 (13.6%) | 1814 (13.7%) | 58 (15.3%) | 0.631 |

| Prior thromboembolic event | 6505 (17.3%) | 2390 (18.0%) | 79 (20.9%) | 0.030 |

| Vascular disease | 18267 (48.5%) | 6417 (48.4%) | 188 (49.6%) | 0.900 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 6913 (18.3%) | 2523 (19.0%) | 75 (19.8%) | 0.173 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4836 (12.8%) | 1794 (13.5%) | 52 (13.7%) | 0.109 |

| Known aortic plaque | 1293 (3.4%) | 449 (3.4%) | 11 (2.9%) | 0.835 |

| HAS-BLED Score; median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.1) | 0.299 |

| Uncontrolled hypertension | 10962 (29.1%) | 3570 (27.0%) | 115 (30.3%) | <.0001 |

| Abnormal renal function | 5129 (13.6%) | 1780 (13.4%) | 53 (14.0%) | 0.86 |

| Abnormal liver function | 1142 (3.0%) | 420 (3.2%) | 11 (2.9%) | 0.71 |

| Prior stroke | 9641 (25.6%) | 3614 (27.3%) | 114 (30.1%) | 0.00 |

| Ischemic stroke | 5546 (57.6%) | 2083 (57.7%) | 58 (50.9%) | 0.35 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 2431 (25.2%) | 952 (26.4%) | 37 (32.5%) | 0.10 |

| Undetermined stroke | 2179 (22.6%) | 800 (22.2%) | 26 (22.8%) | 0.86 |

| Prior bleeding | 26042 (69.1%) | 9455 (71.4%) | 257 (67.8%) | <.0001 |

| Labile INR | 3889 (10.3%) | 1432 (10.8%) | 38 (10.0%) | 0.271 |

| Alcohol use | 2073 (5.5%) | 756 (5.7%) | 28 (7.4%) | 0.202 |

| Antiplatelet medication use | 9949 (26.4%) | 3258 (24.6%) | 92 (24.3%) | 0.000 |

| NSAID | 11649 (30.9%) | 4071 (30.8%) | 112 (29.6%) | 0.803 |

| Other Risk Factors | ||||

| Clinically relevant prior bleeding | 25061 (66.6%) | 9172 (69.3%) | 253 (66.8%) | <.0001 |

| Intracranial | 4191 (11.1%) | 1575 (11.9%) | 65 (17.2%) | 0.000 |

| Epistaxis | 2415 (6.4%) | 825 (6.2%) | 20 (5.3%) | 0.523 |

| Gastrointestinal | 14929 (39.6%) | 5521 (41.6%) | 151 (39.8%) | 0.000 |

| Other | 5629 (14.9%) | 2002 (15.1%) | 41 (10.8%) | 0.069 |

| Indication for occlusion | ||||

| Increased thromboembolic risk | 24184 (64.2%) | 8620 (65.0%) | 235 (62.0%) | 0.129 |

| History of major bleeding | 23357 (62.0%) | 8577 (64.7%) | 242 (63.9%) | <.0001 |

| High fall risk | 13637 (36.2%) | 4614 (34.8%) | 130 (34.3%) | 0.015 |

| labile INR | 3150 (8.4%) | 1087 (8.2%) | 31 (8.2%) | 0.849 |

| Patient preference | 13807 (36.6%) | 4596 (34.7%) | 125 (33.0%) | 0.000 |

| Non-compliance with anticoagulation | 1219 (3.2%) | 431 (3.3%) | 11 (2.9%) | 0.930 |

| Fall risk | 15063 (40.1%) | 5107 (38.6%) | 136 (36.0%) | 0.005 |

| Genetic coagulopathy | 298 (0.8%) | 102 (0.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.503 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 7432 (19.8%) | 2924 (22.1%) | 91 (24.0%) | <.0001 |

| Ischemic | 3692 (9.8%) | 1425 (10.7%) | 42 (11.1%) | 0.006 |

| Non-ischemic | 2617 (6.9%) | 1065 (8.0%) | 33 (8.7%) | <.0001 |

| Restrictive | 42 (0.1%) | 21 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.312 |

| Hypertrophic | 313 (0.8%) | 141 (1.1%) | 7 (1.8%) | 0.007 |

| Other | 800 (2.1%) | 287 (2.2%) | 8 (2.1%) | 0.958 |

| LVEF; mean (SD) | 54.2% (9.9%) | 54.0% (10.3%) | 53.8% (10.5%) | 0.119 |

| Chronic lung disease | 7981 (21.2%) | 2781 (21.0%) | 69 (18.3%) | 0.348 |

| Coronary artery disease | 17710 (47.0%) | 6229 (47.0%) | 171 (45.2%) | 0.788 |

| Sleep apnea | 10214 (27.1%) | 3683 (27.8%) | 108 (28.6%) | 0.269 |

| Atrial fibrillation classification | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 21357 (56.7%) | 6863 (51.8%) | 175 (46.2%) | <.0001 |

| Persistent | 7722 (20.5%) | 2911 (22.0%) | 98 (25.9%) | <.0001 |

| Long standing persistent | 2998 (8.0%) | 1141 (8.6%) | 36 (9.5%) | 0.038 |

| Permanent | 5462 (14.5%) | 2290 (17.3%) | 68 (17.9%) | <.0001 |

| Attempt at AF termination | 15321 (40.7%) | 5622 (42.4%) | 149 (39.4%) | 0.001 |

| Pharmacologic cardioversion | 7550 (49.6%) | 2684 (48.0%) | 82 (55.4%) | 0.040 |

| DC cardioversion | 8343 (54.8%) | 3254 (58.2%) | 91 (61.5%) | <.0001 |

| Catheter ablation | 6183 (40.5%) | 2330 (41.6%) | 67 (45.0%) | 0.216 |

| Surgical ablation | 197 (1.3%) | 77 (1.4%) | 3 (2.0%) | 0.687 |

| Atrial flutter | 5234 (13.9%) | 2070 (15.6%) | 64 (16.9%) | <.0001 |

| Prior structural intervention | 2661 (7.1%) | 1017 (7.7%) | 31 (8.2) | 0.050 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||

| Rural | 3101 (8.2%) | 1178 (8.9%) | 18 (4.7%) | 0.002 |

| Suburban | 10422 (27.6%) | 3697 (27.9%) | 108 (28.5%) | 0.822 |

| Urban | 24173 (64.1%) | 8383 (63.2%) | 253 (66.8%) | 0.093 |

| U.S. Region | ||||

| Northeast | 5991 (15.9%) | 2894 (21.8%) | 91 (24.0%) | <.0001 |

| West | 8196 (21.7%) | 2465 (18.6%) | 76 (20.1%) | <.0001 |

| Midwest | 8584 (22.8%) | 3283 (24.8%) | 97 (25.6%) | <.0001 |

| South | 14904 (39.5%) | 4614 (34.8%) | 115 (30.3%) | <.0001 |

| Patients treated at teaching hospitals | 23445 (62.2%) | 8860 (66.8%) | 272 (71.8%) | <.0001 |

| LAAO procedure volume (Can we remove this?) I think this is important info and prefer to keep | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (65.2) | 54.5 (58.8) | 56.8 (57.8) | <.0001 |

| Median (IQR) | 45.0 (2.0 – 84.0) | 41.0 (0.0 – 79.0) | 46.0 (12.0 – 80.0) | 0.0001 |

NYHA; New York heart association, INR; international normalized ratio, DC; direct current, NSAID; nonsteroidal inflammatory drug use, LV; left ventricular, AF; atrial fibrillation, LVEF; left ventricular ejection fraction, LAAO; left atrial appendage occlusion, SD; standard deviation, IQR; interquartile range

Procedural Characteristics:

Patients with no leaks at follow up had smaller left atrial appendage maximum width before the procedure (21.1±4.2mm) compared with those with small (>0–5mm) and large (>5mm) leaks (22.3±4.3mm and 23.7±4.4mm, respectively; p<0.001). In addition, maximum device margin leak at the end of the procedure was significantly smaller in the no-leak at follow up group (0.1±0.5 mm) vs. the small and large leak at follow up groups (0.2±0.8 and 0.5±1.5 mm, respectively; p<0.001). There were no differences in the use of intracardiac echo, radiation dose, contrast volume or in the occurrence of in-hospital major adverse events between the 3 groups as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2:

Procedural characteristics (among 0 mm; 0 – 5 mm and larger than 5 mm) (secondary)

| 0 mm | (N = 37696) | 0 – 5 mm | (N = 13258) | larger than 5 mm | (N = 379) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||||||

| LAAOrificeMaxWidth | Mean(std) | 21.1 (4.2) | Mean(std) | 22.3 (4.3) | Mean(std) | 23.7 (4.4) | <.0001 |

| Range | 0.0 – 50.0 | Range | 0.0 – 50.0 | Range | 12.0 – 49.0 | ||

| Observations | 36658 (97.2%) | Observations | 12987 (98.0%) | Observations | 368 (97.1%) | ||

| Sedation | |||||||

| minimalseda | N(Yes%) | 61 (0.2%) | N(Yes%) | 15 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.3433 |

| moderatesed | N(Yes%) | 512 (1.4%) | N(Yes%) | 270 (2.0%) | N(Yes%) | 4 (1.1%) | <.0001 |

| deepsedatio | N(Yes%) | 155 (0.4%) | N(Yes%) | 67 (0.5%) | N(Yes%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.3543 |

| generalanes | N(Yes%) | 36895 (97.9%) | N(Yes%) | 12877 (97.1%) | N(Yes%) | 373 (98.4%) | <.0001 |

| Indication for LAAO | |||||||

| Increased thromboembolic risk | N(Yes%) | 24184 (64.2%) | N(Yes%) | 8620 (65.0%) | N(Yes%) | 235 (62.0%) | 0.1286 |

| History of major bleeding | N(Yes%) | 23357 (62.0%) | N(Yes%) | 8577 (64.7%) | N(Yes%) | 242 (63.9%) | <.0001 |

| High fall risk | N(Yes%) | 13637 (36.2%) | N(Yes%) | 4614 (34.8%) | N(Yes%) | 130 (34.3%) | 0.0147 |

| labileINR | N(Yes%) | 3150 (8.4%) | N(Yes%) | 1087 (8.2%) | N(Yes%) | 31 (8.2%) | 0.8486 |

| Patient preference | N(Yes%) | 13807 (36.6%) | N(Yes%) | 4596 (34.7%) | N(Yes%) | 125 (33.0%) | 0.0001 |

| Non-compliance with anticoagulation therapy | N(Yes%) | 1219 (3.2%) | N(Yes%) | 431 (3.3%) | N(Yes%) | 11 (2.9%) | 0.9302 |

| Device ResidualLeak | Mean(std) | 0.1 (0.5) | Mean(std) | 0.2 (0.8) | Mean(std) | 0.5 (1.5) | <.0001 |

| Range | 0.0 – 10.0 | Range | 0.0 – 10.0 | Range | 0.0 – 9.0 | ||

| Observations | 36989 (98.1%) | Observations | 13016 (98.2%) | Observations | 374 (98.7%) | ||

| Guidance Method | |||||||

| Fluoroscopy | N(Yes%) | 34667 (92.0%) | N(Yes%) | 12134 (91.5%) | N(Yes%) | 356 (93.9%) | 0.0929 |

| Intracardia | N(Yes%) | 447 (1.2%) | N(Yes%) | 149 (1.1%) | N(Yes%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.2217 |

| TEE | N(Yes%) | 2132 (5.7%) | N(Yes%) | 831 (6.3%) | N(Yes%) | 19 (5.0%) | 0.0279 |

| Cumulative Air kerma | Mean(std) | 743.2 (1599.1) | Mean(std) | 746.3 (1530.8) | Mean(std) | 933.9 (2431.9) | 0.1035 |

| Range | 1.0 – 50000.0 | Range | 1.0 – 50000.0 | Range | 4.0 – 36875.0 | ||

| Observations | 32026 (85.0%) | Observations | 11314 (85.3%) | Observations | 318 (83.9%) | ||

| Contrast Volume | Mean(std) | 63.0 (47.3) | Mean(std) | 62.6 (46.9) | Mean(std) | 67.9 (47.1) | 0.0996 |

| Range | 0.0 – 751.0 | Range | 0.0 – 636.0 | Range | 0.0 – 320.0 | ||

| Observations | 36498 (96.8%) | Observations | 12754 (96.2%) | Observations | 368 (97.1%) | ||

| Procedure Adjudicated Major Event Occurred | |||||||

| Pericadial effusion | N(Yes%) | 334 (0.9%) | N(Yes%) | 138 (1.0%) | N(Yes%) | 3 (0.8%) | 0.2672 |

| Device Systemic Ebolism | N(Yes%) | 4 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 1 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.9361 |

| Cardiac Arrest | N(Yes%) | 24 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 15 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.178 |

| Myocardial Infarction | N(Yes%) | 15 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 3 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.6193 |

| Ischemic Stroke | N(Yes%) | 32 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 11 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.8503 |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | N(Yes%) | 1 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.8345 |

| Undetermined Stroke | N(Yes%) | 2 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.6964 |

| TIA | N(Yes%) | 10 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 4 (0.0%) | N(Yes%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.9269 |

| major bleeding | N(Yes%) | 510 (1.4%) | N(Yes%) | 193 (1.5%) | N(Yes%) | 3 (0.8%) | 0.4224 |

| major vascular complcation | N(Yes%) | 59 (0.2%) | N(Yes%) | 11 (0.1%) | N(Yes%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.1178 |

Antithrombotic medications:

Upon discharge following the index LAAO admission, 18,231 patients (35.6%) were prescribed aspirin, 6,600 (12.8%) were prescribed a P2Y12 inhibitor, 23,209 (45.2%) were prescribed warfarin, 24,274 (47.3%) were prescribed a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), and 2,453 (4.8%) were not prescribed any antiplatelets or anticoagulants. The proportion of patients who remained on warfarin at the 45-day follow-up visit was significantly higher among patients with large compared with those with small or no leaks (44.9% vs. 34.4% and 32.4%, respectively, p<0.001), with no difference in the rates of remaining on a DOAC between the 3 groups (37.5% vs. 35.5%, and 35.5% in patients large, small, and no leaks, respectively, p=0.72). However, at 6- and 12- months follow up, the use of both warfarin and DOACs declined but remained more frequent among patients with large peri-device leaks (Table 3).

Table-3.

Temporal Trends in Antithrombotic Use in the Study Cohort

| Leak= 0 mm (N=37,696) | Leak= >0–5 mm (N=13,258) | Leak >5 mm (N= 379) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 13171 (34.9%) | 4906 (37.0%) | 154 (40.6%) | <.0001 |

| Warfarin | 16894 (44.8%) | 6127 (46.2%) | 188 (49.6%) | 0.005 |

| DOAC | 17966 (47.7%) | 6148 (46.4%) | 160 (42.2%) | 0.005 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 4916 (13.0%) | 1636 (12.3%) | 48 (12.7%) | 0.115 |

| Bridging anticoagulant therapy | 357 (0.9%) | 127 (1.0%) | 7 (1.8%) | 0.201 |

| None/Other? | 1805 (4.8%) | 626 (4.7%) | 22 (5.8%) | 0.613 |

| 45-day medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 12117 (32.1%) | 4581 (34.6%) | 131 (34.6%) | <.0001 |

| Warfarin | 12206 (32.4%) | 4556 (34.4%) | 170 (44.9%) | <.0001 |

| DOAC | 13383 (35.5%) | 4700 (35.5%) | 142 (37.5%) | 0.721 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 11041 (29.3%) | 3592 (27.1%) | 61 (16.1%) | <.0001 |

| Bridging anticoagulant therapy | 133 (0.4%) | 44 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.905 |

| None | 7913 (21.0%) | 2458 (18.5%) | 42 (11.1%) | <.0001 |

| 180-day medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 8526 (22.6%) | 3416 (25.8%) | 99 (26.1%) | <.0001 |

| Warfarin | 539 (1.4%) | 315 (2.4%) | 65 (17.2%) | <.0001 |

| DOAC | 1368 (3.6%) | 653 (4.9%) | 83 (21.9%) | <.0001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 17557 (46.6%) | 6268 (47.3%) | 94 (24.8%) | <.0001 |

| Bridging anticoagulant therapy | 89 (0.2%) | 29 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.930 |

| None | 27605 (73.2%) | 9081 (68.5%) | 166 (43.8%) | <.0001 |

| 1-year medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 4923 (13.1%) | 1932 (14.6%) | 56 (14.8%) | <.0001 |

| Warfarin | 266 (0.7%) | 132 (1.0%) | 13 (3.4%) | <.0001 |

| DOAC | 847 (2.2%) | 380 (2.9%) | 41 (10.8%) | <.0001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 3946 (10.5%) | 1511 (11.4%) | 55 (14.5%) | 0.001 |

| Bridging anticoagulant therapy | 61 (0.2%) | 32 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.127 |

| None | 31785 (84.3%) | 10874 (82.0%) | 275 (72.6%) | <.0001 |

DOAC; direct oral anticoagulant

Cumulative incidence rates of adverse events:

The CIR of ischemic stroke was low overall but was higher in patients with small leaks (1.61%) compared with those with no leaks (1.39%) and those with large leaks (1.42%). Similarly, the incidence rates of major bleeding, of the composite endpoint of stroke, TIA, or SE, and of the MAE were higher in patients with small leaks compared with those with no or large leaks (Table 4). However, the incidence rate of death was higher in the large leak cohort (7.96%) compared with the no leak (5.97%) or small leak (6.41%) cohorts. After risk-adjustment, small leaks were associated with significantly higher rates of ischemic stroke, ischemic stroke/TIA/SE, and any SAE. The risk adjusted CIR of death, and of major bleeding were not different between patients with small vs. no leaks (Supplementary Table-2).

Table-4.

Incidence Rates of Adverse Events Stratified by Leak Size

| Clinical Outcomes | Leak= 0 mm (N=37,696) | Leak= 0–5 mm (N=13,258) | Leak >5 mm (N= 379) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Stroke | 1.39% (1.27%–1.52%) | 1.61% (1.39%–1.84%) | 1.42% (0.18%–2.66%) |

| Stroke, TIA, or SE | 2.98% (2.80%–3.17%) | 3.49% (3.16%–3.81%) | 3.13% (1.31%–4.94%) |

| Major Bleeding | 7.58% (7.3%–7.86%) | 8.57% (8.07%–9.07%) | 6.82% (4.19%–9.45%) |

| Death | 5.97% (5.72%–6.23%) | 6.41% (5.97%–6.85%) | 7.96% (5.13%–10.78%) |

| Any MAE | 17.43% (17.02%–17.83%) | 19.44% (18.73%–20.15%) | 19.61% (15.46%–23.76%) |

TIA; transient ischemic attack, SE; systemic embolization, MASE: major adverse serious event which included death, cardiac arrest, ischemic, hemorrhagic, or undetermined stroke, TIA, SE, major bleeding, major vascular complication (fistula or pseudoaneurysm requiring fibrin injection, angioplasty, or surgical repair), myocardial infarction, pericardial effusion requiring intervention, or device embolization.

Time-to-event survival analysis:

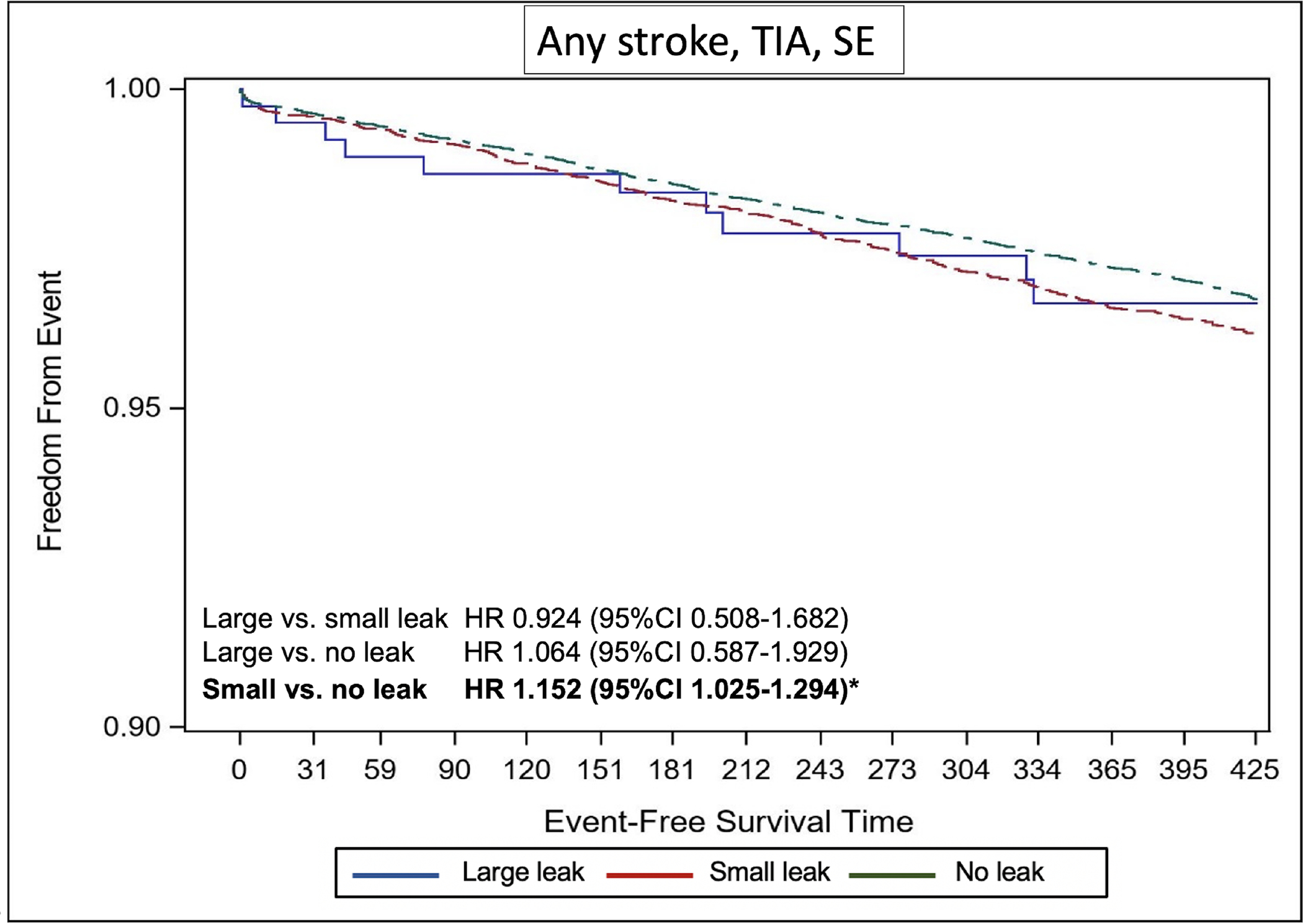

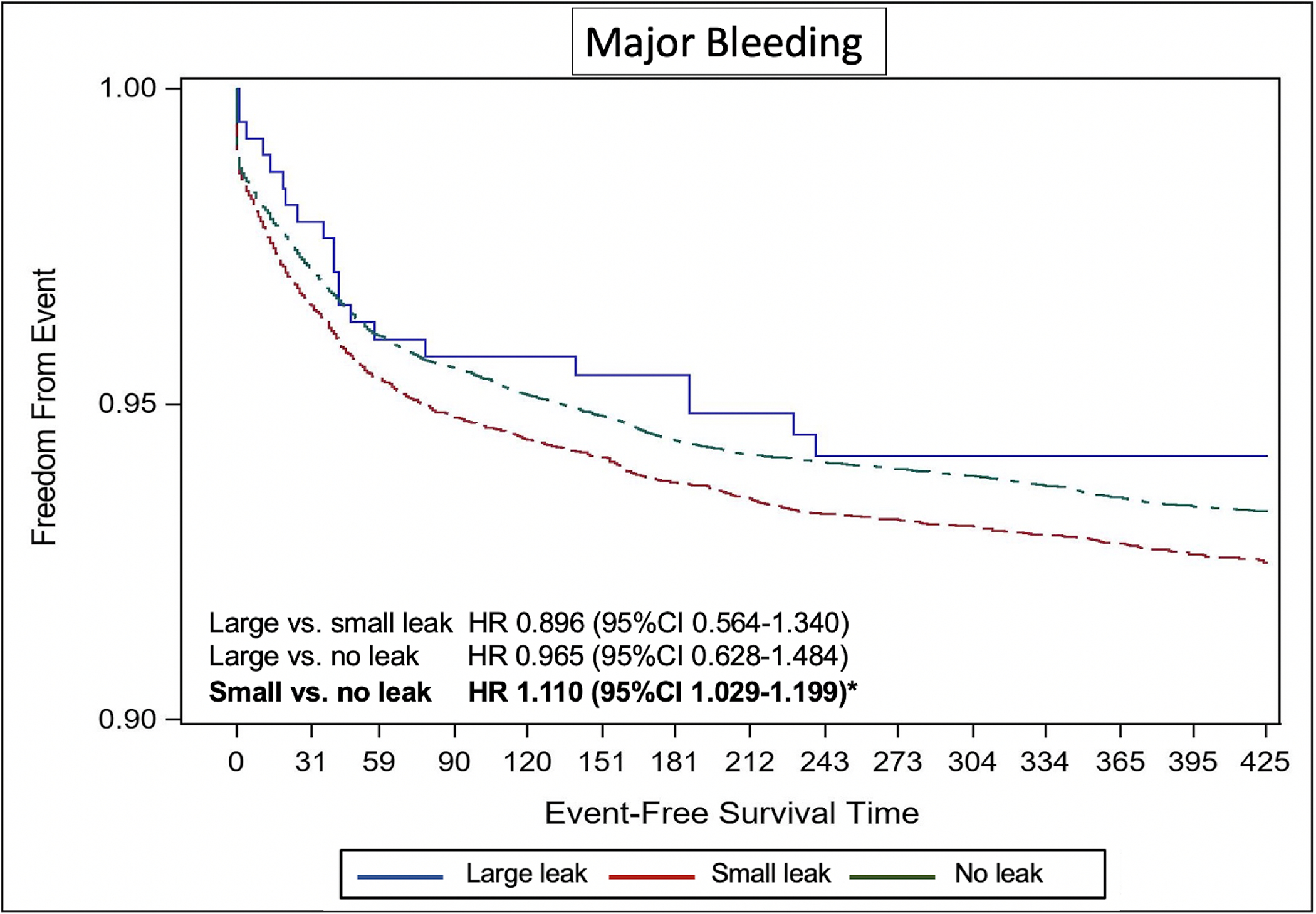

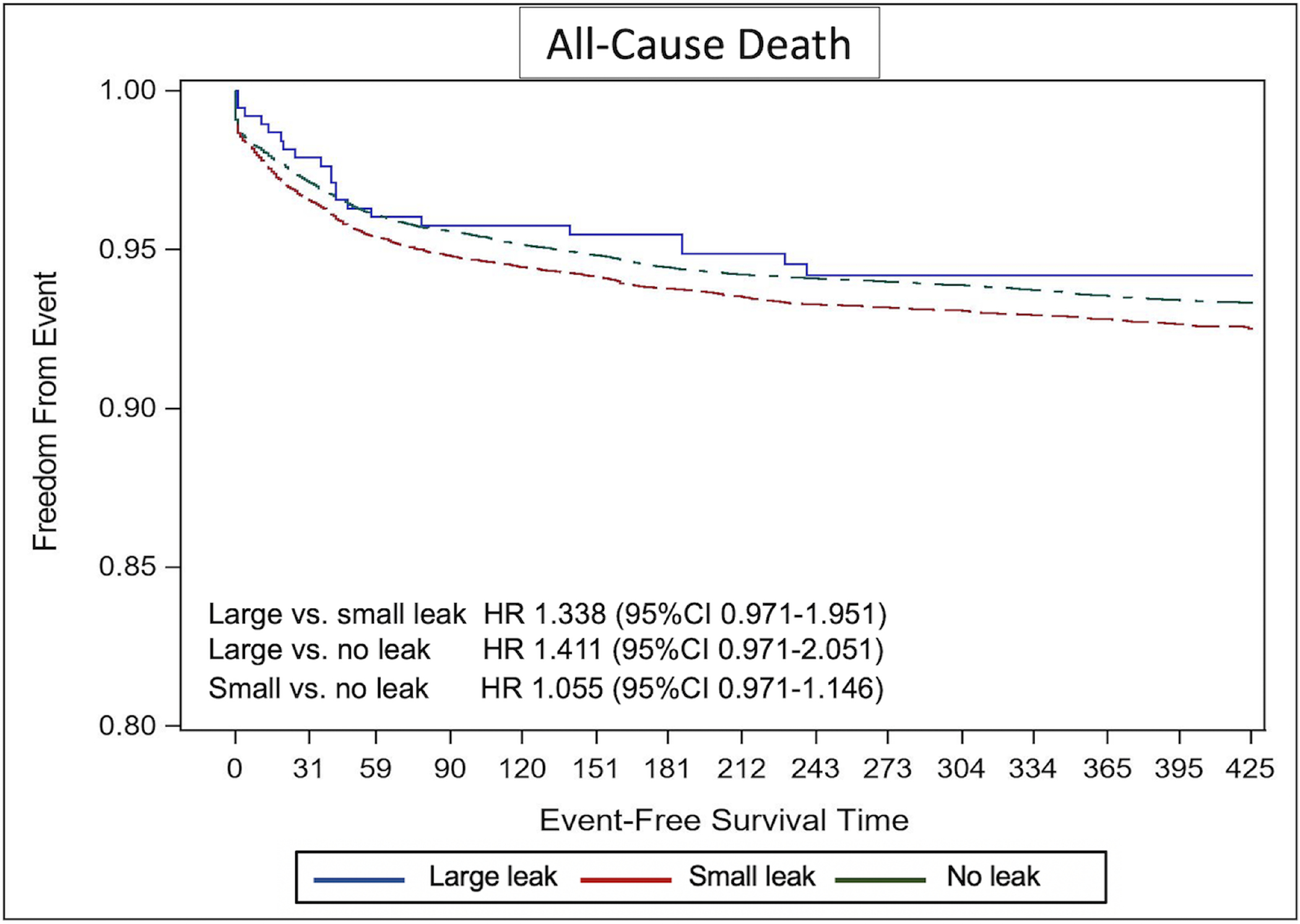

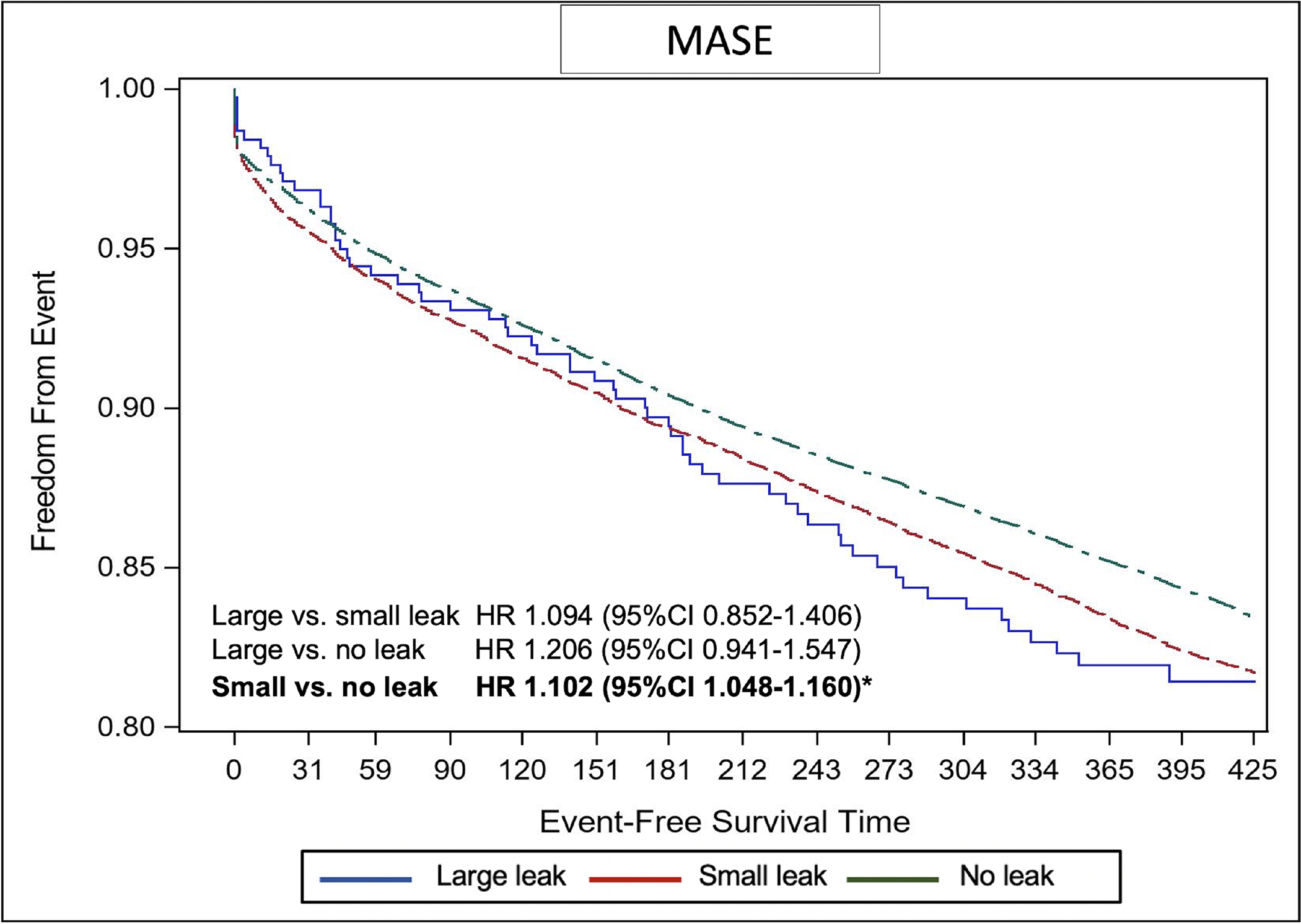

The Kaplan-Meier estimate of stroke/TIA/systemic embolization was significantly higher in patients with small leaks compared with those without leak (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.152, 95%CI 1.025–1.294) (Figure 2). The Kaplan-Meier estimate of any ischemic stroke was higher in the small leak cohort compared with the no leak cohort but did not reach statistical significance (aHR 1.133, 95%CI 0.955–1.343). There was no difference in the risk of any stroke, TIA, or SE between patients with large leaks compared with those with no or small leaks (Figure 2). Similarly, the cumulative probability of major bleeding was significantly higher in the small leak cohort compared with the no leak cohort (aHR 1.11, 95%CI 1.029–1.199), with no significant difference between the large leak cohort and the other 2 cohorts (Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the Kaplan-Meier estimates of death across the 3 groups (Figure 4). However, the risk of any MAE was higher in the small leak group compared with patients with no leak (aHR 1.10, 95%CI 1.048–1.160), (Figure 5); there were no differences for the other groups.

Figure-2.

Kaplan Meier Curves of the Risk of Any Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack, or Systemic Embolization Stratified by Leak Size

Figure-3.

Kaplan Meier Curves of the Risk of Major Bleeding Stratified by Leak Size

Figure-4.

Kaplan Meier Curves of the Risk of Death Stratified by Leak Size

Figure-5.

Kaplan Meier Curves of the Risk of Major Adverse Serious Events Stratified by Leak Size

HR; hazard ratio, CI; confidence interval

Secondary analyses:

(A) When dividing the study cohort to patients with any leaks (N=13,637) vs. those with no leaks (N=37,696), time to event survival analysis showed a higher probability of stroke, TIA, or SE in the latter group (aHR 1.149, 95%CI 1.024–1.290) (Supplementary Figure-1). (B) When dividing the study cohort to 4 subgroups (no leak, leak <3 mm, leak 3–5 mm, and leak >5 mm), time to event survival analysis showed a higher probability of stroke, TIA, or SE in patients with leaks <3 mm compared with those with no leaks (aHR 1.140, 95%CI 1.001–1.297). There were no statistically significant differences between patients with leaks 3–5 mm or patients with leaks >5mm and those with no leaks (Supplementary Figure-2).

Discussion:

There is an enormous variability in the size, shape, and orientation of the LAA in humans. Hence, it was recognized early in the LAAO experience that fixed shape devices may often be associated with incomplete LAA closure due to peri-device leakage. Several studies have then investigated the incidence of peri-device leak and its potential clinical impact (5,7–12,16). However, these studies faced a few challenges including the arbitrary and variable definition of ‘significant’ leak, the lack of standard method of measuring the leaks, and the small number of subsequent events which hindered their ability to draw firm conclusions.

The present study represents the largest analysis to-date dedicated to assessing the prevalence and clinical implications of peri-device leaks after LAAO. Our analysis included >50,000 patients who underwent LAAO in the US between 2016 and 2019 documents 3 key findings: First, 1 in 4 patients had a residual leak on 45-day follow-up imaging after LAAO. However, large leaks (>5 mm) constituted only ~3% of all leaks and 0.7% of all devices implanted. Second, more patients with large leaks remained on anticoagulation at 45-day, 6-month, and 1-year compared with patients with no or small leaks, although most patients were not on anticoagulation by 1-year. Third, there were modest but statistically significant associations between small leaks and thromboembolic and bleeding events. Conversely, although the point estimates suggested a possible association between large leaks and thromboembolic events, this association was not statistically significant. These findings deserve further elaboration.

Incidence of peri-device leak:

The first systematic assessment of peri-device leak comes from the pivotal PROTECT AF (Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) trial. In PROTECT AF, among the 445 patients who underwent TEE at 45-day after LAAO, 182 (40.9%) had peri-device leak (12). The leaks were classified as minor <1 mm (14/182; 7.7%), moderate 1–3 mm (109/182; 59.9%), and severe >3 mm (59/182; 32.4%). The incidence of peri-device leak in subsequent real-world cohorts varied widely between 5%−35% due to various definitions and surveillance protocols (10). With the improved device design, the Watchman FLX device has demonstrated a significantly lower rate of peri-device leak at 45-day in the PINNACLE FLX Trial [small (0–5 mm) leak:17.2%, large (>5 mm leak): 0%] (13). Our analysis showed an ~25% incidence rate of peri-device leak in a large cohort treated with the first-generation Watchman 2.5 device. Considering the commonly used 5 mm cutoff for ‘significant’ leak in clinical practice, we classified leaks to small (0–5 mm) and large (>5 mm) in this study. We found that most leaks (97%) were small.

Medical management of peri-device leak:

Our prospectively collected data illustrates that compared with patients without leaks, those with peri-device leak were less likely to discontinue oral anticoagulation. However, this was only true for patients with large (>5 mm) leaks of whom ~40%, and ~15% remained on an oral anticoagulant at 6-month and 1-year, respectively. Among patients with small (0–5 mm) leaks, only ~7% and 4% remained on an oral anticoagulant at 6-month and 1-year, respectively. Although some patients could have undergone subsequent procedures for leak closure (e.g., coiling, plugging, etc.), these data are not available in the LAAO Registry. Hence, the impact of those potential correction procedures on antithrombotic regimen could not be assessed in this study. Nonetheless, data on interventional management of peri-device leak are limited, and the optimal management of this problem remain uncertain, highlighting the need to address the open question of whether residual leaks indeed confer higher risk of subsequent adverse events (5,7,8,17).

Clinical impact of peri-device leak:

Peri-device leak size was not associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events in the PROTECT AF trial, and in the Amulet Observational Study (11,12). However, these sub-studies were underpowered with only 16 and 7 thromboembolic events recorded during follow-up, respectively. A recent analysis combined data from 3 Food and Drug Administration studies (PROTECT-AF + PREVAIL + CAP2) to assess the long-term impact of peri-device leak in a cohort of 1,054 patients who underwent LAAO with the Watchman 2.5 device (18). In this study, 39.8% and 28.4% of patients had a peri-device leak on 45-day and 1-year TEE, respectively. There was a trend toward an increase in ischemic stroke or SE in patients with any leak at 45 days (5 yr rate 9.2% vs. 6.6%) but this was not statistically significant (p=0.14). However, patients who had a leak at 1-year had a 2-fold increase in ischemic stroke/SE at 5 years compared with those with no leaks (9.9% vs. 5.1%, p=0.008). This study was the first to show an association between peri-device leak, albeit only those detected at 1-year, and subsequent adverse ischemic events.

Our study sought to leverage a large nationwide registry to further address the open questions about peri-device leaks and their clinical impact. Our findings suggest that small leaks detected at 45-day follow up (but not large ones) were associated with a modest increase in thromboembolic events compared with no leak. These findings are in keeping with the recent study by Reddy et al, likely reaching statistical significance due to the large cohort of patients studied (>50,000). Reasons for this association cannot be ascertained in our study due to the nature of the database utilized. Whether this association is mechanistic (small leaks lead to thrombus formation at the leak site and subsequent embolic events) or whether it is related to high-risk features in patients with leaks (? Higher left atrial size, fibrosis, etc.) remain to be studied. With regards to large leaks (>5mm), we speculate that our study may have been underpowered to assess the association between those leaks and subsequent events, considering that large leaks were extremely rare (<1%), and that a large proportion of patients with large leaks were maintained on prolonged courses of oral anticoagulation.

Our findings have important implications on procedural techniques and post-procedural management. Efforts should be made to achieve complete seal of the LAA when possible, to mitigate the risk of future ischemic events. This requires a comprehensive approach that includes adequate pre-procedural imaging, and good understanding of the LAA anatomy, the pros, and cons of the occluder device, and the mechanism of peri-device leak (6,19). Fortunately, second generation devices (e.g., Watchman FLX) are now the available and have been associated with lower incidence of both small and large leaks compared with first-generation devices. Whether leaks after LAAO with the Watchman FLX devices (and others such as the recently approved Amulet device; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) are associated with a similar increase in subsequent ischemic events remain to be studied.

Further studies are also needed to assess the optimal approach to small leaks after LAAO. For instance, does the presence of a 3–4 mm leak require a more prolonged course of anticoagulation? This needs to be carefully considered against the potential increased risk of bleeding in these patients especially given the modest magnitude of increase in thromboembolic events and their very low rates overall. Although there was no increase in bleeding events in patients with large leaks who remained on anticoagulation for a longer period after LAAO, patients with small leaks had more bleeding events than those with no leak. Reasons for this observation are not well understood given the similar medication use profile in patients with small leak compared with those with no leak. It should also be emphasized that more research is needed to determine the optimal detection method for peri-device leak and the optimal surveillances interval considering the large differences in the reported leak incidence and size between TEE and cardiac computed tomography (19,20).

Limitations:

Our study has several limitations. First, the LAAO registry is an observational database and hence the study is subject to the known limitations of observational analyses such as the inability to completely adjust for unmeasured confounders and to make causal inferences. Second, the measurement of peri-device leak is self-reported and is subject to variability in assessment techniques and the possibility of under- or over- estimation of the leak size. Third, data on certain factors that may impact the occurrence of peri-device leak such as LAA size and shape and implant depth are not available in the LAAO Registry. Fourth, post-LAAO anticoagulant and antiplatelets use data are derived from the LAAO standard data collection forms, which likely denotes the prescription of these medications. Whether patients have filled and complied with the prescription remains uncertain. In addition, data on the interventional management of peri-device leak are not available in the LAAO registry. Fifth, the association between peri-device leak and the occurrence of device-related thrombus has been suggested. However, we could not assess this in the current study as there is no standardized follow-up imaging in the LAAO Registry and it is relatively uncommon beyond the 45-day window in US clinical practice. Sixth, this study only includes patients treated with the Watchman 2.5 device. Second generation LAAO devices have become available for commercial use in the US and are reported to have lower rates of peri-device leak which is not assessed in the current study. Furthermore, follow-up was limited to ~1-year. It is possible that a longer term follow up could impact the results and the conclusions of the study similar to what has been documented in the recent study by Reddy et al (18). Finally, although we applied rigorous risk adjustment methodology, the possibility of residual unmeasured confounders could not be completely excluded.

Conclusions:

In a large nationwide cohort of >50,000 patients, large (>5mm) peri-device leaks after LAAO were rare (<1%) and not associated with adverse events. Small leaks (0–5mm) were present in ~25% and were associated with higher thromboembolic and bleeding events during 1-year follow up.

Supplementary Material

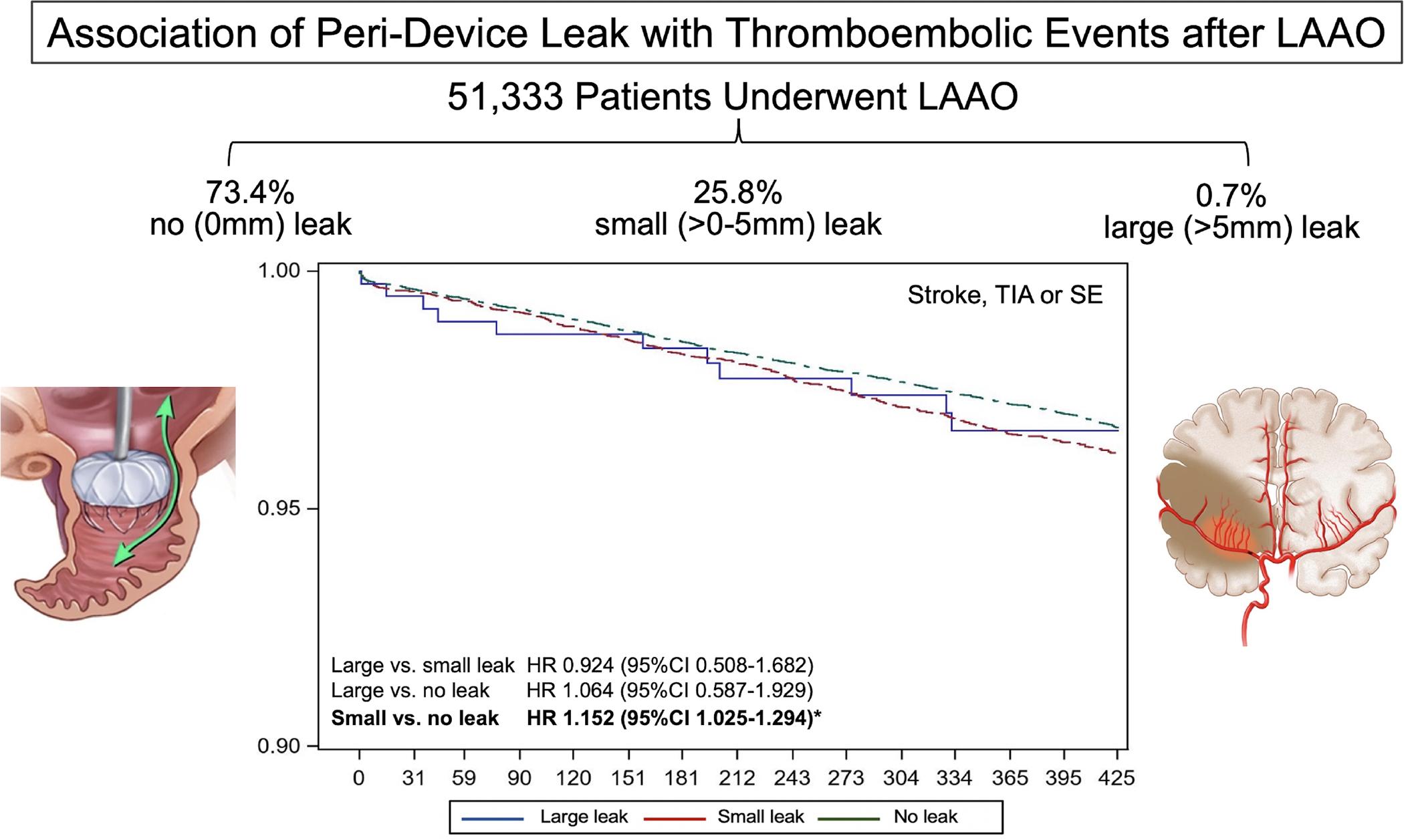

Central Illustration: Association of Peri-Device Leak with Thromboembolic Events after LAAO.

Among >50,000 patients who underwent LAAO in the US (2016–2019), 1 in 4 patients had peri-device leak detected on follow up imaging at 45 days. Majority of leaks were small <5 mm in diameter. Small leaks, however, we associated with a modest increase in the composite endpoint of stroke, TIA, or SE at 1 year follow up.

LAAO; left atrial appendage occlusion, TIA; transient ischemic attack, SE; systemic embolization, HR; hazard ratio.

PERSPECTIVES:

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE 1:

Peri-device leaks are found in 1 of 4 patients on 45 day follow up imaging after left atrial appendage occlusion. However, large leaks (>5mm) remain rare (<1%).

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE 1:

Small leaks (0–5mm) after left atrial appendage closure are associated with a modest increase in thromboembolic and bleeding event rates at 1-year follow up.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 1:

Further studies are needed to determine the prevalence of peri-device leak and their association with adverse events with contemporary generation left atrial appendage occlusion devices.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 2:

Techniques to mitigate and manage peri-device leaks also need to be further investigated.

Disclosures:

The study was funded by a grant from Boston Scientific, the sponsor had no role in the design of the study or the interpretation of the data. Dr. Alkhouli is on the advisory board of Boston Scientific. Dr Freeman received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American College of Cardiology NCDR during the conduct of the study; and personal fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Biosense Webster outside the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- NVAF

non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- LAAO

left atrial appendage closure

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- SE

systemic embolization

- TEE

transesophageal echo

- MAE

major adverse event

- NCDR

National Cardiovascular Data Registry

References

- 1.Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P et al. Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Direct Oral Anticoagulants in High-Risk Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:3122–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S et al. 5-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2964–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes DR, Jr., Alkhouli M, Reddy V. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion for The Unmet Clinical Needs of Stroke Prevention in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:864–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkhouli M, Holmes DR. Remaining Challenges With Transcatheter Left Atrial Appendage Closure. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:2244–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkhouli M Management of Peridevice Leak After LAAO: Coils, Plugs, Occluders, or Better Understanding of the Problem? JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:320–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkhouli M, Chaker Z, Clemetson E et al. Incidence, Characteristics and Management of Persistent Peri-Device Flow after Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. Structural Heart 2019;3:491–498. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piayda K, Sievert K, Della Rocca DG et al. Safety and Feasibility of Peri-device Leakage Closure after LAAO: An International, Multi-center Collaborative Study. EuroIntervention 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Della Rocca DG, Horton RP, Di Biase L et al. First Experience of Transcatheter Leak Occlusion With Detachable Coils Following Left Atrial Appendage Closure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen A, Gallet R, Riant E et al. Peridevice Leak After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Impact. Can J Cardiol 2019;35:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael CE, Friedman PA, Saw J, Pislaru SV, Munger TM, Holmes DR Jr. Residual leaks following percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion: assessment and management implications. EuroIntervention 2017;13:1218–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saw J, Tzikas A, Shakir S et al. Incidence and Clinical Impact of Device-Associated Thrombus and Peri-Device Leak Following Left Atrial Appendage Closure With the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10:391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viles-Gonzalez JF, Kar S, Douglas P et al. The clinical impact of incomplete left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman Device in patients with atrial fibrillation: a PROTECT AF (Percutaneous Closure of the Left Atrial Appendage Versus Warfarin Therapy for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kar S, Doshi SK, Sadhu A et al. Primary Outcome Evaluation of a Next-Generation Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device: Results From the PINNACLE FLX Trial. Circulation 2021;143:1754–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman JV, Varosy P, Price MJ et al. The NCDR Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:1503–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darden D, Duong T, Du C et al. Sex Differences in Procedural Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion: Insights From the NCDR LAAO Registry. JAMA Cardiol 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmann MW, Ince H, Kische S et al. Real-world safety and efficacy of WATCHMAN LAA closure at one year in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy: results of the DAPT subgroup from the EWOLUTION all-comers study. EuroIntervention 2018;13:2003–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhouli M, Chaker Z, Al-Hajji M, Sengupta PP. Management of Peridevice Leak Following Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:967–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy VY HD, Doshi SK, Kar S, Singh S, Gibson D, Price MJ, Natale A, Mansour MC, Sievert H, Allocco DJ, Dukkipati SR. Peri-Device Leak After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: Impact on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes. Circulation 2021;144.33906377 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korsholm K, Berti S, Iriart X et al. Expert Recommendations on Cardiac Computed Tomography for Planning Transcatheter Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:277–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korsholm K, Jensen JM, Norgaard BL et al. Peridevice Leak Following Amplatzer Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion: Cardiac Computed Tomography Classification and Clinical Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.