Abstract

The molecular basis of interindividual clinical variability upon infection with Staphylococcus aureus is unclear. We describe patients with haploinsufficiency for the linear deubiquitinase OTULIN, encoded by a gene on chromosome 5p. Patients present episodes of life-threatening necrosis, typically triggered by S. aureus infection. The disorder is phenocopied in patients with the 5p- (Cri-du-Chat) chromosomal deletion syndrome. OTULIN haploinsufficiency causes an accumulation of linear ubiquitin in dermal fibroblasts, but TNF-receptor NF-κB-signaling remains intact. Blood leukocyte subsets are unaffected. The OTULIN-dependent accumulation of caveolin-1 in dermal fibroblasts — but not leukocytes — facilitates the cytotoxic damage inflicted by the staphylococcal virulence factor α-toxin. Naturally elicited antibodies against α-toxin contribute to incomplete clinical penetrance. Human OTULIN haploinsufficiency underlies life-threatening staphylococcal disease by disrupting cell-intrinsic immunity to α-toxin in non-leukocytic cells.

One-line summary

OTULIN haploinsufficiency underlies life-threatening staphylococcal disease by disrupting cell-intrinsic immunity to α-toxin.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major bacterial pathogen with a global impact on human health (1). Individuals with staphylococcal disease may present a range of superficial (folliculitis, cellulitis, abscesses) to severe (e.g. necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections and necrotizing pneumonia, with or without septicemia) manifestations (1). Most individuals carry S. aureus asymptomatically on their skin and in their nostrils for long periods of their lives, but only a minority develop life-threatening staphylococcal disease. Severe disease has a poor prognosis, owing to its rapid invasive course (2–5). Acquired risk factors for staphylococcal disease include surgery and intravascular devices (1). Life-threatening staphylococcal disease can also result from single-gene inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) (6). Disorders affecting phagocyte development or function, such as severe congenital neutropenia, chronic granulomatous disease, and leukocyte adhesion deficiency, confer a predisposition to staphylococcal disease (6, 7). Disorders of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) and interleukin (IL)-1R nuclear factor-kappa B (TIR-NF-κB) pathway (8–12) and of IL-6- and STAT3-dependent immunity (13–17) have also been identified in patients suffering from severe staphylococcal disease. All these defects preferentially affect innate, myeloid immunity, but, collectively, they account for only a small proportion of cases (18). Most cases of severe staphylococcal disease remain unexplained, because they strike otherwise healthy individuals with no detectable phagocyte defect (2, 19). Here, we aimed to elucidate human genetic and immunological etiologies of life-threatening staphylococcal disease.

Results

Genome-wide enrichment in rare OTULIN variants

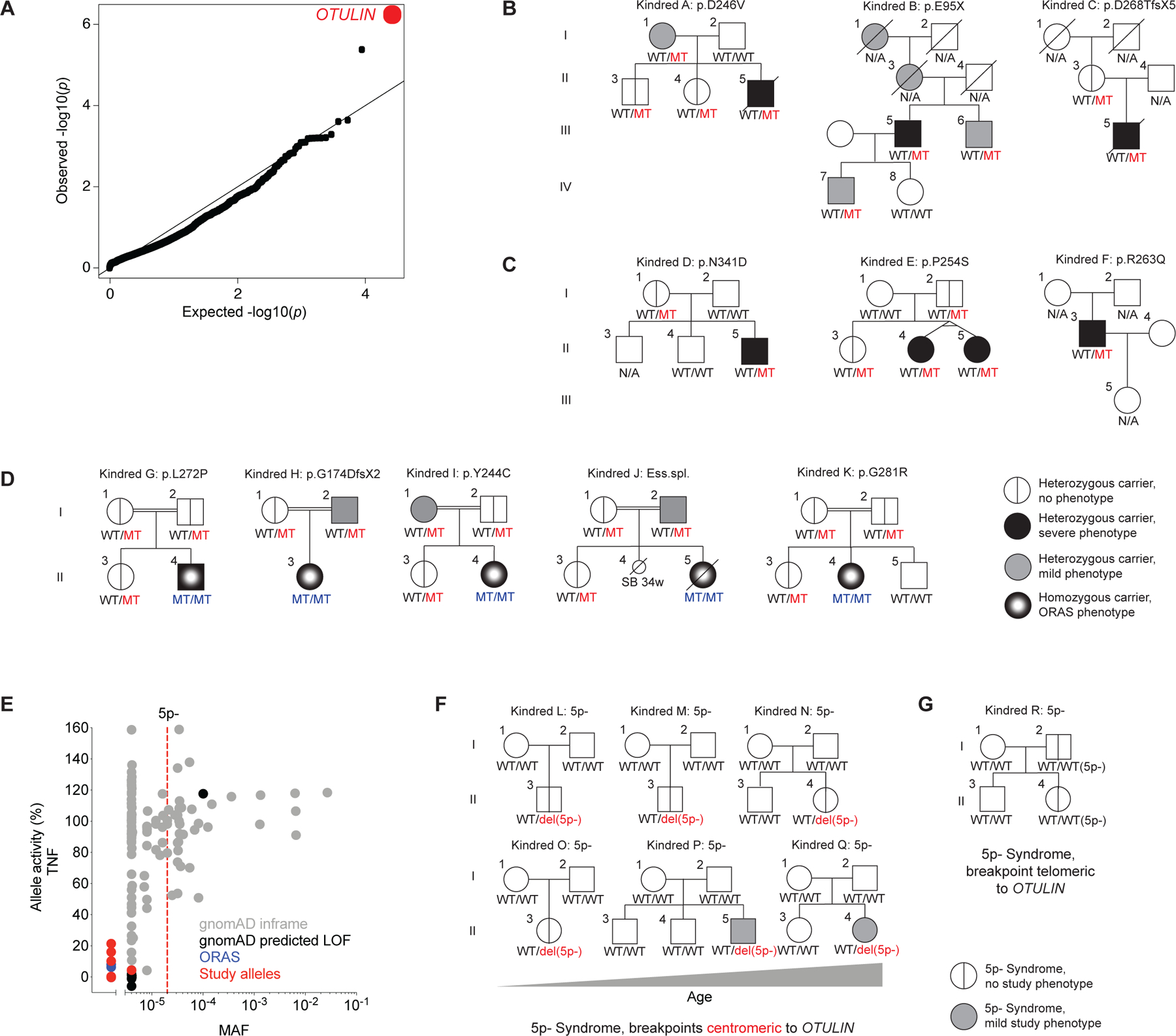

Given the severity of their disease, we hypothesized that there would be at least some genetic homogeneity in our cohort of patients with unexplained life-threatening staphylococcal disease. We sequenced the exomes of the N=105 index cases. Given the rarity of severe staphylococcal disease in otherwise healthy individuals, and assuming a dominant mode of inheritance, we hypothesized that the disease-causing variants would be very rare (minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1x10−5) (20). We also prioritized variants predicted to be deleterious (combined annotation-dependent depletion score (CADD) > mutation significance cutoff (MSC)) (21–23). We performed the same analysis on N=1,274 control exomes from patients with mycobacterial diseases (including individuals with Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease or with tuberculosis), which rarely overlap with staphylococcal disease (24). After adjusting for ethnicity by principal component analysis (PCA), we used the results of these two analyses to test the null hypothesis that variants of a given gene were not specific to staphylococcal disease. OTULIN was the only gene satisfying the threshold for statistical significance on a genome-wide level with a P-value of 5.74x10−7 (Figure 1A, Tables S1, 2). We repeated our analysis for OTULIN, adding 2,504 individuals from the 1,000 Genomes Project (25) to our control dataset (26); none of these individuals had developed life-threatening infections with S. aureus. The enrichment in OTULIN variants was even stronger (P=3.85x10−8) in this analysis, indicating that very rare variants of this gene were found specifically in patients with severe staphylococcal disease.

Figure 1. OTULIN haploinsufficiency and its molecular characterization.

(A) Genome-wide enrichment in rare, predicted deleterious variants in the cohort of N=105 patients with severe staphylococcal disease, relative to N=1,274 patients with mycobacterial disease. (B) Pedigrees of the kindreds presenting severe necrotizing staphylococcal disease and carrying heterozygous mutations of OTULIN. (C) Pedigrees of the kindreds carrying heterozygous mutations of OTULIN and presenting necrosis triggered by other etiologies. (D) Pedigrees of the kindreds of ORAS probands carrying biallelic mutations of OTULIN. (E) Functional population genetics based on minor allele frequencies (MAFs) reported in the gnomAD database and the NF-κB inhibitory capacity of the OTULIN variants, as assessed with a luciferase reporter system in transiently transfected HEK293T cells stimulated with TNF (datapoints represent the mean of N=4–5 per variant). (F) Pedigrees of the kindreds of the 5p- syndrome probands carrying deletions with a breakpoint centromeric to OTULIN. The patients are shown in ascending age order (left to right, top to bottom). (G) Pedigree of the 5p- syndrome kindred with probands carrying a deletion with a breakpoint telomeric to OTULIN. WT: wild-type allele; MT: mutant allele; LOF: loss of function. See also Figure S1 and Table S1, S2.

The patients carry heterozygous OTULIN variants

The linear deubiquitinase OTULIN is a negative regulator of inflammation (27, 28). In humans, biallelic OTULIN mutations cause a potentially fatal early-onset autoinflammatory condition called OTULIN-related autoinflammatory syndrome (ORAS) (29–33). Closer inspection revealed that the signal for genetic homogeneity in the cohort of patients with severe staphylococcal disease was driven by three probands carrying heterozygous variants of OTULIN (Figure 1B): one missense (p.D246V), one nonsense (p.E95X), and one frameshift (p.D268TfsX5) variant. In each of these probands, the clinical hallmark of disease following infection with S. aureus was life-threatening necrosis of the skin and/or lungs (Figure S1A; SM). Based on the extreme inflammatory responses to infection with S. aureus in these patients, we investigated the possibility of other triggers generating similar disease. We identified three additional kindreds with very rare heterozygous missense variants of OTULIN (p.N341D, p.P254S, and p.R263Q) (Figure 1C). The probands of these kindreds presented severe diseases triggered by infectious and unknown etiologies (Figure S1B; SM). The clinical course of disease in patients with no documented infection suggests that low-grade infections, or non-infectious triggers, might induce an inflammatory phenotype similar to that of patients with documented S. aureus infection (Figure S1A, B; SM). In total, we identified six very rare variants in seven patients from six kindreds (Figure S1C). These seven patients did not carry variants fitting the known modes of inheritance for any of the 430 genes already implicated in IEIs (7, 34). In most patients, the first episode of disease occurred during adolescence (SM). Clinical data indicated a degree of phenotypic heterogeneity in the index cases, but with the skin and/or lungs consistently affected in all cases (Figure 1B, C, S1A, B; SM). One third of the heterozygous relatives (three of the nine for whom data were available) expressed a related but milder phenotype, the other six carriers being apparently healthy (Figure 1B, C; SM). We then hypothesized that the parents of the patients with biallelic OTULIN deficiency reported in previous studies (29–32), who themselves carried deleterious OTULIN alleles in the heterozygous state, might present phenocopies of the disorder observed in the patients of our cohort. One third of the parents (three of the 10) did, indeed, express the phenotype (Figure 1D; SM). Thus, very rare heterozygous mutations of OTULIN confer predisposition to severe necrosis of the skin and lungs, typically, but not exclusively, after infection with S. aureus, with variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance.

OTULIN is subject to negative selection

The severity of disease in the probands carrying very rare heterozygous OTULIN variants suggests that this gene is subject to evolutionary forces acting at the population level. Indeed, the f parameter score for OTULIN is 0.36, indicating that this gene is under negative selection (Figure S1D) (35). Moreover, the consensus score for negative selection (CoNeS) for OTULIN is −0.78, within the reported range for genes underlying IEIs with both autosomal dominant (AD) and autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance (Figure S1E) (36). OTULIN has a LoFtool score of 0.115, suggesting that it does not tolerate haploinsufficiency (37). Predicted loss-of-function (pLOF) OTULIN variants are very rare in the general population, with a cumulative MAF of 1x10−4 (Figure S1F) (20). Consistent with the negative selection pressure acting on OTULIN, the alleles of the patients were found to be either ultra-rare or private (Figure S1F) (20). These population genetics parameters indicate that heterozygous pLOF variants of OTULIN are disadvantageous for the individual. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the very rare variants for which enrichment was detected in the patients studied are causal for the life-threatening necrosis of the skin and/or lungs triggered by S. aureus infection.

The OTULIN alleles of the patients are severely hypomorphic or amorphic

We overexpressed the cDNAs corresponding to the OTULIN alleles of the patients in HEK293T cells. The truncated cDNAs of the patients were loss-of-expression, whereas the missense cDNAs of the patients and cDNAs corresponding to two OTULIN alleles commonly found in the general population (20) were expressed at normal levels (Figure S1G). No in-frame re-initiation was observed for truncated alleles from the patients (Figure S1H). We then assessed the deubiquitinase activity of the products of the alleles from the patients, and their capacity to inhibit NF-κB-signaling. Consistent with published findings in overexpression systems, some, but not all the protein products of the alleles concerned were defective for the linear deubiquitination of NEMO in the presence of LUBAC (Figure S1I) (32, 33). We assessed the capacity of the gene products to regulate receptor signaling, by investigating the functional consequences of the OTULIN alleles of the patients for NF-κB inhibition following stimulation with TNF in a cellular signaling system. All the alleles from patients were severely hypomorphic or amorphic (Figure S1J). By contrast to the alleles of the patients, the two alleles common in the general population (20) were found to be isomorphic (Figure S1J). The apparent differences between the two overexpression systems may reflect different impacts of the various OTULIN alleles on ubiquitin binding capacity (27, 32, 33). We then performed functional tests for all the other OTULIN coding sequence variants reported in public databases (N=120) (20). The cumulative MAF of amorphic and hypomorphic OTULIN alleles (with <25% wild-type levels of NF-κB-signaling inhibitory activity) in the general population was 6x10−5 (Figure 1E). The greater rarity of amorphic and hypomorphic OTULIN alleles than of pLOF variants highlights the importance of experimental validation for pLOF variants. Thus, the rare OTULIN variants found in the patients are deleterious and AD OTULIN deficiency predisposes the patients to disease.

Autosomal dominant OTULIN deficiency acts via haploinsufficiency

We tested the genetic mechanism of AD OTULIN deficiency and found no negative dominance for the alleles expressed by the patients (Figure S1K). This implies that the genetic mechanism underlying AD OTULIN deficiency is haploinsufficiency. OTULIN is located on the short arm of chromosome 5. Depending on the breakpoint, almost all individuals with 5p- syndrome — the most common chromosomal deletion syndrome in humans, also known as Cri-du-Chat syndrome — are haploinsufficient for OTULIN by definition (38–40). The prevalence of 5p- syndrome is ~1 in 50,000 live births, similar to the cumulative MAF for amorphic and hypomorphic OTULIN alleles (Figure 1E) (41). Respiratory tract infections are one of the principal causes of hospitalization in individuals with 5p- syndrome, and pneumonia is amongst the commonest causes of death in these individuals (40, 42–44). We recruited six 5p- syndrome patients with a breakpoint centromeric to OTULIN (Figure 1F, S1L). Expressivity was variable and penetrance was incomplete, but one third of these OTULIN haploinsufficient 5p- syndrome patients (two of six) presented an age-dependent phenocopy of the disorder observed in patients with heterozygous OTULIN mutations (Figure 1F; SM). We also identified two individuals from a multigeneration kindred affected by 5p- syndrome with an extremely rare breakpoint telomeric to OTULIN (Figure 1G, S1L) (38). Both these individuals carried two copies of OTULIN and did not display the phenotype studied here (SM). The clinical similarities between patients with heterozygous OTULIN mutations and those with 5p- syndrome suggest a common mechanism of predisposition to infection due to haploinsufficiency for OTULIN.

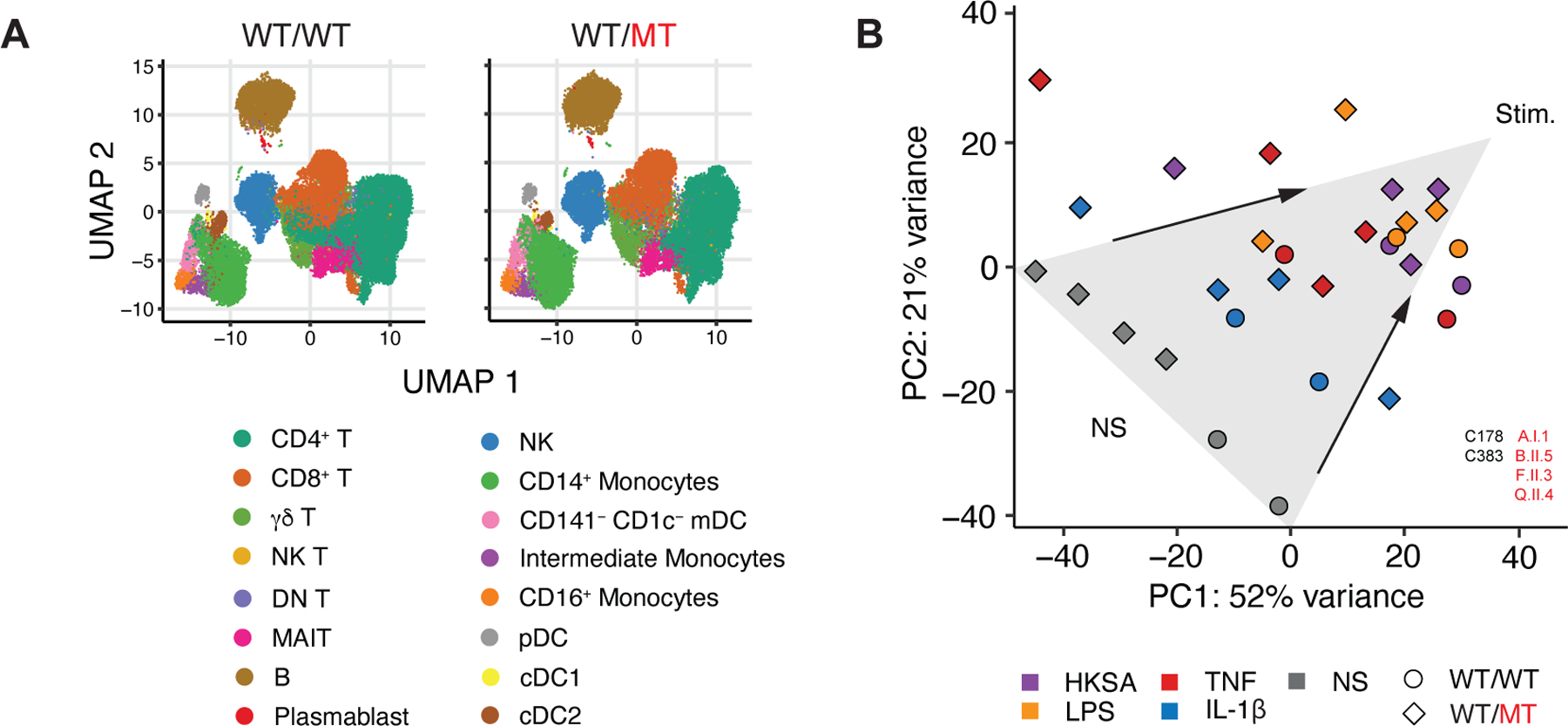

Immunological characterization of OTULIN-haploinsufficient PBMCs

The autoinflammatory features seen in ORAS patients are largely driven by abnormally high levels of NF-κB activation in myeloid cells (29, 30, 33). We thus investigated whether patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency presented any related immunological disturbances. OTULIN expression in monocytes differed between patients and healthy controls (Figure S2A). Routine immunological tests performed in diagnostic laboratories (including assessments of leukocyte differentiation and oxidative burst capacity — deficiencies of which are known to confer a predisposition to staphylococcal disease (6, 7)) revealed no explanatory defects in patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency (SM). We thus looked for more subtle immunological features, by testing PBMCs from the patients by mass cytometry (cytometry by time-of-flight, CyTOF) (45) and RNA sequencing. In comparisons with healthy controls, we observed no differences in the abundance of leukocyte subsets or in the expression of lineage markers (Figure 2A, S2B–D). The development of myeloid and lymphoid subsets in patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency was, therefore, apparently normal. At baseline, we observed a complex transcriptional signature not associated with NF-κB-driven inflammation in the PBMCs of the patients (Figure 2B, S2E). This difference between the patients and healthy controls disappeared following stimulation (Figure 2B). Both at baseline and after stimulation, the PBMCs of the patients had a capacity to secrete various cytokines, including TNF and IL-1β, similar to that of PBMCs from healthy controls (Figure S2F). We detected no defect of IL-6 production (Figure S2F), deficiencies of which are known to be associated with staphylococcal disease (6). Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed a contribution of CD14+ monocytes to the transcriptional signature in the PBMCs of the patients relative to healthy controls (Figure S2G, H). However, consistent with their capacity to produce normal amounts of TNF and IL-1β (Figure S2I), the amounts of phosphorylated P65 in CD14+ monocytes from the patients were normal both at baseline and following stimulation (Figure S2J). The CD14+ monocytes of patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency, thus, did not appear to be functionally affected. Finally, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived macrophages from patients had normal oxidative burst and phagocytic capacities relative to healthy controls (Figure S2K, L). These observations suggest an absence of overt immunological disturbance in patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency, contrasting with the autoinflammatory markers described in ORAS patients (29–33).

Figure 2. OTULIN haploinsufficiency does not impair the hematopoietic immune system.

(A) Aggregate uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with autosomal dominant OTULIN deficiency and healthy controls, as assessed by cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF). (B) Principal component (PC) analysis plot of the transcriptional profile of PBMCs at baseline and after incubation with various stimuli, in comparison with healthy controls. Arrows have been added for visual support of the direction of variance after stimulation. NS: not stimulated; HKSA: heat-killed S. aureus. See also Figure S2.

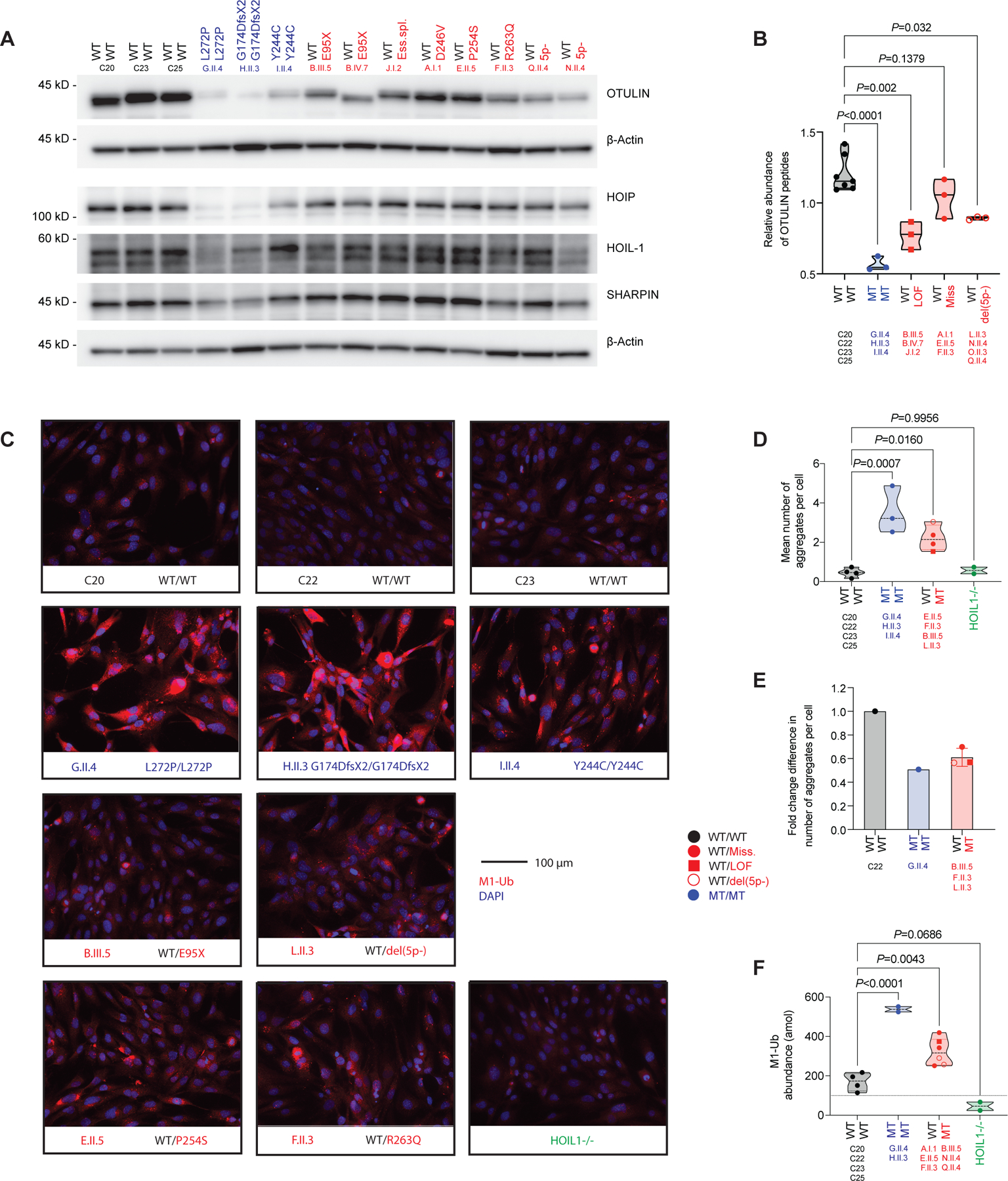

OTULIN gene dosage-dependent accumulation of linear ubiquitin in fibroblasts

We next performed a biochemical characterization of the non-hematopoietic compartment in the patients and assessed the levels of OTULIN expression in primary dermal fibroblasts (PDFs). OTULIN mRNA levels varied (Figure S3A, B), but the levels of the corresponding protein were low in the patients and depended on the nature of the mutation (Figure 3A, B). OTULIN haploinsufficiency led to an accumulation of aggregates containing linear ubiquitin (M1-Ub) in immortalized fibroblasts from patients, including 5p- syndrome patients with a breakpoint centromeric to OTULIN (Figure 3C, D, S3C). These aggregates were sensitive to treatment with exogenous OTULIN (Figure S3D), and their accumulation was rescued by genetic complementation with wild-type OTULIN (Figure 3E, S3E). We used a combination of an M1-Ub-selective tandem Ub-binding entity (TUBE) and absolute quantification (AQUA) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to assess M1-Ub levels in immortalized fibroblasts from the patients. M1-Ub levels were much higher in the cells of both ORAS and OTULIN-haploinsufficient patients than in those of healthy controls and HOIL1-deficient patients (Figure 3F) (46). Thus, OTULIN haploinsufficiency and recessive deficiency result in the cellular accumulation of M1-Ub in a gene dosage-dependent manner.

Figure 3. OTULIN gene dosage-dependent accumulation of M1-Ub in fibroblasts.

(A) Expression of OTULIN, HOIP, HOIL-1, and SHARPIN in primary dermal fibroblasts (PDFs). (B) Relative abundance of OTULIN peptides in PDFs, as determined by mass spectrometry analysis (median). (C) Accumulation of aggregates containing M1-Ub in immortalized fibroblasts, as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Representative images. (D) Quantification of the aggregate accumulations seen in (D) (median). (E) Quantification of aggregates containing M1-Ub in immortalized fibroblasts after rescue with wild-type OTULIN, as compared with cells rescued with an empty virus (mean ±SD). (F) Abundance of M1-Ub, as determined by AQUA-MS/MS analysis of immortalized fibroblasts (median). Statistical significance was calculated by ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. See also Figure S3.

Normal TNF-receptor signaling in OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts

In the PDFs of ORAS patients, expression of the components of the linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) decreases to compensate for recessive OTULIN deficiency (Figure 3A) (29, 30, 32). This compensatory mechanism impaired TNF-receptor signaling in immortalized fibroblasts from ORAS patients (Figure S3F). By contrast, OTULIN haploinsufficiency did not lead to a loss of LUBAC expression in PDFs (Figure 3A), or to impaired TNF-receptor signaling (Figure S3F) or IL-6 and IL-8 secretion (Figure S3G). Indeed, no differential transcription patterns were evident in the patients’ PDFs after stimulation with TNF (Figure S3H). The impairment of early NF-κB activation sensitizes PDFs from ORAS and LUBAC-deficient patients to TNF-induced apoptotic cell death under stress conditions (29, 46). However, consistent with their normal LUBAC expression, PDFs from patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency were not susceptible to stress-induced apoptosis upon exposure to TNF (Figure S3I). Thus, the functional dysregulation of TNF-receptor signaling via NF-κB is limited to fibroblasts displaying a recessive OTULIN deficiency.

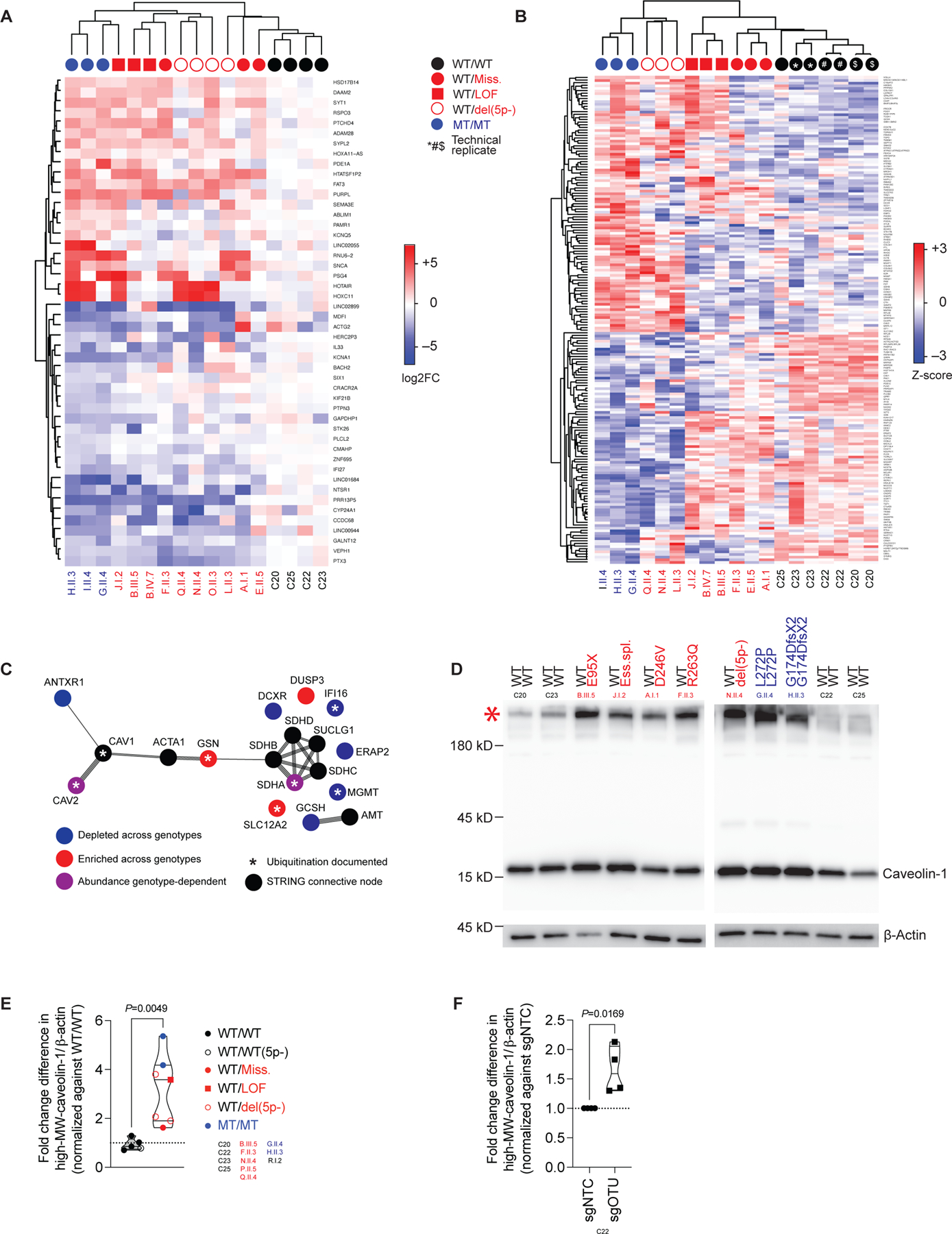

Global dysregulation of transcription in OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts

The presence of a biochemical phenotype in the absence of an immunological phenotype following stimulation in OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts led us to investigate transcriptional homeostasis in resting PDFs from the patients. Consistent with the gene dosage-dependent accumulation of M1-Ub in immortalized fibroblasts, this approach revealed a continuous genotype-dependent transcriptional phenotype in the basal state (Figure 4A). Despite an absence of functional consequences of OTULIN haploinsufficiency (Figure S3F–I), specific gene-set enrichment analyses of the resting transcriptome revealed a subtle signal for TNF-receptor signaling via NF-κB (Figure S4A). These analyses also revealed a transcriptional signature affecting various other cellular processes relative to cells from healthy controls (Figure S4A) (47). The affected processes included the MYC and E2F transcription factor systems and the G2M cell cycle checkpoint system, the gene sets for these systems displaying a partial overlap (Figure S4B). These findings indicate a global dysregulation of transcription in resting OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts.

Figure 4. OTULIN-dependent accumulation of caveolin-1 in fibroblasts.

(A) Transcriptional profile of unstimulated primary dermal fibroblasts (PDFs), as assessed by RNA sequencing, expressed as log2-fold changes (FC) relative to the mean value for controls. Genes satisfying the threshold for statistical significance in comparisons of ORAS patients to controls are shown. (B) Proteomic profiles of unstimulated PDFs, as assessed by mass spectrometry on whole-cell lysates, expressed as Z-scores. Genes satisfying the threshold for statistical significance in comparisons of ORAS patients to controls are shown. (C) STRING analysis of the cluster of proteins with differential abundances in various genotypes identified in (B). (D) Accumulation of SDS-resistant high-MW caveolin-1-containing complexes in PDF-whole cell lysates (WCLs). (E) High-MW caveolin-1-containing complex intensities relative to β-actin intensities in PDF-WCLs, normalized against the mean value of healthy controls (datapoints indicate the mean of N=2 replicates per patient, median per group). (F) High-MW caveolin-1-containing complex intensities relative to β-actin intensities in PDF-WCLs treated with an sgRNA pool targeting OTULIN (sgOTU), normalized against the mean value in those treated with a non-targeting control sgRNA (sgNTC) (median, N=4). The statistical significance of differences was assessed in Student’s t-tests. See also Figure S4.

Accumulation of caveolin-1 in OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts

The observed patterns of transcription could not be explained by the known function of OTULIN as a linear deubiquitinase. We thus hypothesized that OTULIN haploinsufficiency affects cellular homeostasis posttranslationally, in an as yet unknown manner. The proteome of the resting PDFs from the patients displayed a continuous cellular phenotype, consistent with the transcriptome (Figure 4B, S4C). Focusing on this continuous proteomic phenotype, we observed a pattern of differential abundance for a cluster of 11 proteins including caveolin-2 and gelsolin (Figure S4D–F). A STRING-interaction network analysis of this protein cluster identified a node connecting caveolin-2 and gelsolin: caveolin-1 (Figure 4C). Conventional techniques revealed the accumulation of SDS-resistant high-molecular weight (MW) caveolin-1-containing complexes (48, 49) in PDFs from the patients in comparison with those from healthy controls (Figure 4D, E). We analyzed caveolin-1 immunopurification products (IPs) from PDF whole-cell lysates (WCLs) from one healthy control and one patient with recessive OTULIN deficiency by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Validating the STRING-interaction network (Figure 4C), both sets of caveolin-1 IPs also contained caveolin-2, whereas gelsolin was detected in the OTULIN-deficient sample only (Figure S4G). Caveolin-1 levels vary between cell types and are highest in structural cells, such as fibroblasts (50, 51). By contrast to our observations for PDFs, caveolin-1 was barely detectable in hematopoietic cells and the abundance of caveolin-1 in monocytes did not differ between OTULIN haploinsufficient patients and healthy controls (Figure S4H). We detected no accumulation of caveolin-1-containing complexes in PDFs from the 5p- syndrome patient carrying two copies of the OTULIN gene relative to healthy controls (Figure 4E, S4I). However, as in PDFs from the patients, caveolin-1 accumulated as a high-MW complex in an isogenic OTULIN-knockout PDF cell line (Figure 4F; Figure S4J). Thus, OTULIN haploinsufficiency results in a selective accumulation of high-MW caveolin-1 in PDFs.

Lysine-63-linked polyubiquitination of caveolin-1

The differences in gelsolin abundance in PDFs were attributed to differences in GSN transcription, but no differential transcription was detected for CAV1 and CAV2 (Figure S5A). Caveolin-1 is a key component of cell membrane microdomains, in which it acts as a scaffold for other proteins and receptors (47, 52). A signal for plasma membrane disturbance was detected at the proteomic but not transcriptional level in the patients’ PDFs (Figure S5B), suggesting a posttranslational role for OTULIN in the regulation of caveolin-1 expression in PDFs. Caveolin-1 is decorated with ubiquitin (48, 49, 53). We hypothesized that OTULIN haploinsufficiency and recessive deficiency affect the ubiquitination status of caveolin-1. We found that caveolin-1 IPs from PDF-WCLs from one healthy control and one patient with recessive deficiency of OTULIN contained a high-MW ubiquitin-containing complex (Figure S5C). We then used LC-MS/MS to characterize the ubiquitination profiles of purified caveolin-1 in solution, in the high-MW complex fraction, and in the monomeric fraction. Lysine-48-linked polyubiquitin (K48-Ub) chains were conjugated to the high-MW caveolin-1-containing complex regardless of genotype (Figure S5D). We detected no M1-Ub in any of the caveolin-1 IP fractions (Figure S5C, D). Instead, the high-MW caveolin-1-containing complex was abundantly decorated with lysine-63-linked polyubiquitin (K63-Ub) chains in the OTULIN-deficient sample, but not in the healthy control (Figure 5A, S5C) (49). No other branched polyubiquitin linkages were detected in the caveolin-1 IP fractions. The remaining unmodified ubiquitin was probably conjugated as a monomer to caveolin-1 (Figure S5D) (53). The OTULIN-dependent accumulation of caveolin-1 complexes modified with K63-Ub but not M1-Ub chains indicates crosstalk between OTULIN and other ubiquitin ligases and/or hydrolases.

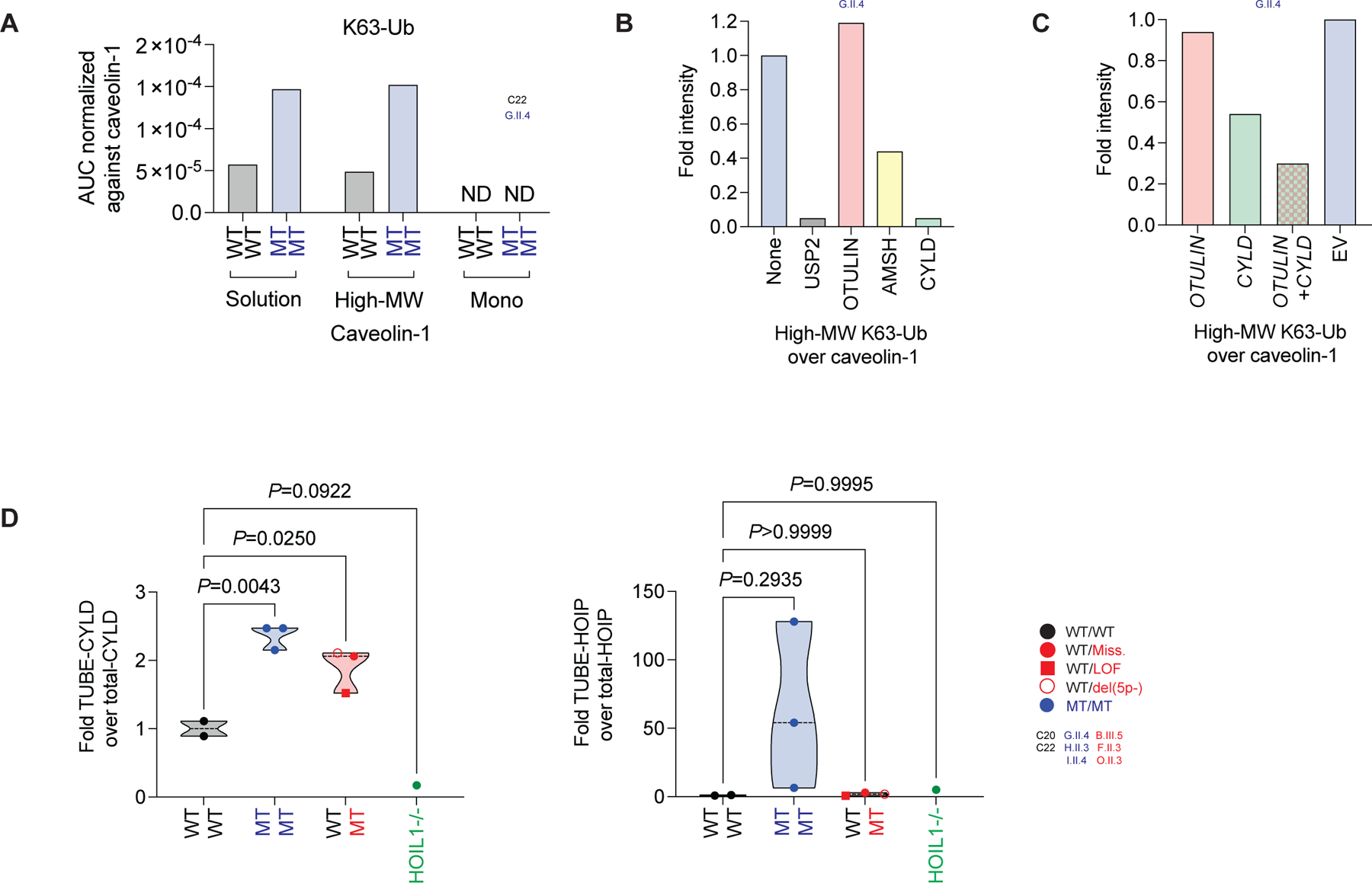

Figure 5. Polyubiquitination of caveolin-1.

(A) Analysis of K63-Ub on caveolin-1 by LC-MS/MS on purified caveolin-1 from primary dermal fibroblast (PDF) whole cell lysates (WCLs). Caveolin-1 was analyzed in solution, in the high-molecular weight (MW) complex fraction, and in the monomeric (Mono) fraction. (B) High-MW K63-Ub complex intensities relative to caveolin-1 intensities in recombinant deubiquitinase-treated purified caveolin-1 from PDFs. (C) High-MW K63-Ub complex intensities relative to caveolin-1 intensities in purified caveolin-1 from PDFs after rescue with CYLD and/or OTULIN. (D) Intensities of CYLD and HOIP bound to M1-Ub, as detected in TUBE pull-downs from immortalized fibroblasts, relative to intensities of total CYLD and HOIP, respectively. Statistical significance was calculated by ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. See also Figure S5.

CYLD binds linear ubiquitin

We characterized the crosstalk between OTULIN and K63-Ub chains, by treating purified caveolin-1 from one ORAS patient with a panel of recombinant deubiquitinases. Consistent with the respective specificities of the various hydrolases, the K63-linked polyubiquitination of high-MW caveolin-1 was reduced by treatment with recombinant CYLD but not OTULIN (Figure 5B, S5E). Similarly, the overexpression of CYLD but not OTULIN in PDFs from a patient with ORAS rescued the K63-linked polyubiquitination of high-MW caveolin-1 (Figure 5C, S5F). Unexpectedly, a stronger rescue was observed when both CYLD and OTULIN were overexpressed (Figure 5C, S5F). Caveolin-1 colocalized with K63-Ub and, to some extent, with M1-Ub aggregates in PDFs (Figure S5G). We used a combination of TUBE and high-input AQUA-MS/MS in immortalized fibroblasts to identify proteins bound to M1-Ub. We detected LUBAC components (Figure S5H), which are known to be decorated with M1-Ub (29). We also identified caveolin-1 and CYLD as possibly binding to M1-Ub (Figure S5H), and used cells from a HOIL1-deficient patient to validate specificity (46). The detection of caveolin-1 was not specific (Figure S5I), consistent with the absence of M1-Ub in the caveolin-1 IP (Figure 5A, S5C, D). We confirmed the specific binding of CYLD to M1-Ub in an OTULIN gene-dosage dependent manner (Figure 5D, S5I). The M1-Ub-bound CYLD-species had a higher MW than that for the total CYLD-pool (Figure S5I), suggesting posttranslational modification. We identified no Gly-Gly ubiquitination signature sites on CYLD by proteomic approaches, suggesting that the posttranslational modification is not ubiquitination itself and that the binding of CYLD to M1-Ub is non-covalent. Unlike an OTULIN gene-dosage effect, M1-Ub-bound HOIP was detected in cells from ORAS patients only (Figure 5D, S5I, J). These data reveal a direct, LUBAC-independent but OTULIN-dependent binding of M1-Ub to CYLD.

Colocalization of caveolin-1 with S. aureus α-toxin

Caveolin-1 clusters in membrane microdomains (52) and has been reported to colocalize with a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10) (54). ADAM10 is a cell surface receptor used by the staphylococcal virulence factor α-toxin (54, 55). α-toxin is a pore-forming cytotoxin triggering ADAM10-mediated cell death in a process facilitated by caveolin-1 (56). We hypothesized that the OTULIN-dependent caveolin-1 accumulation in the PDFs from the patients would contribute to the adverse outcomes of their disease. We thus investigated the cellular kinetics of α-toxin binding. Following its addition to PDFs, α-toxin colocalized with both ADAM10 and caveolin-1 (Figure 6A, S6A, B). ADAM10 and caveolin-1 were colocalized to some extent in the presence or absence of toxin binding (Figure 6A, S6A, B). The patients’ PDFs displayed moderately higher levels of α-toxin binding than cells from healthy controls (Figure 6B, S6C). This observation could not be explained by differential ADAM10 expression at baseline (Figure S6D, E). However, after α-toxin binding, the expression of ADAM10 at the cell surface was greater in PDFs from patients than in those from healthy controls (Figure S6F). These data suggest a role for caveolin-1 in retaining ADAM10 at the surface of the cell when OTULIN-haploinsufficient fibroblasts are exposed to α-toxin (57, 58).

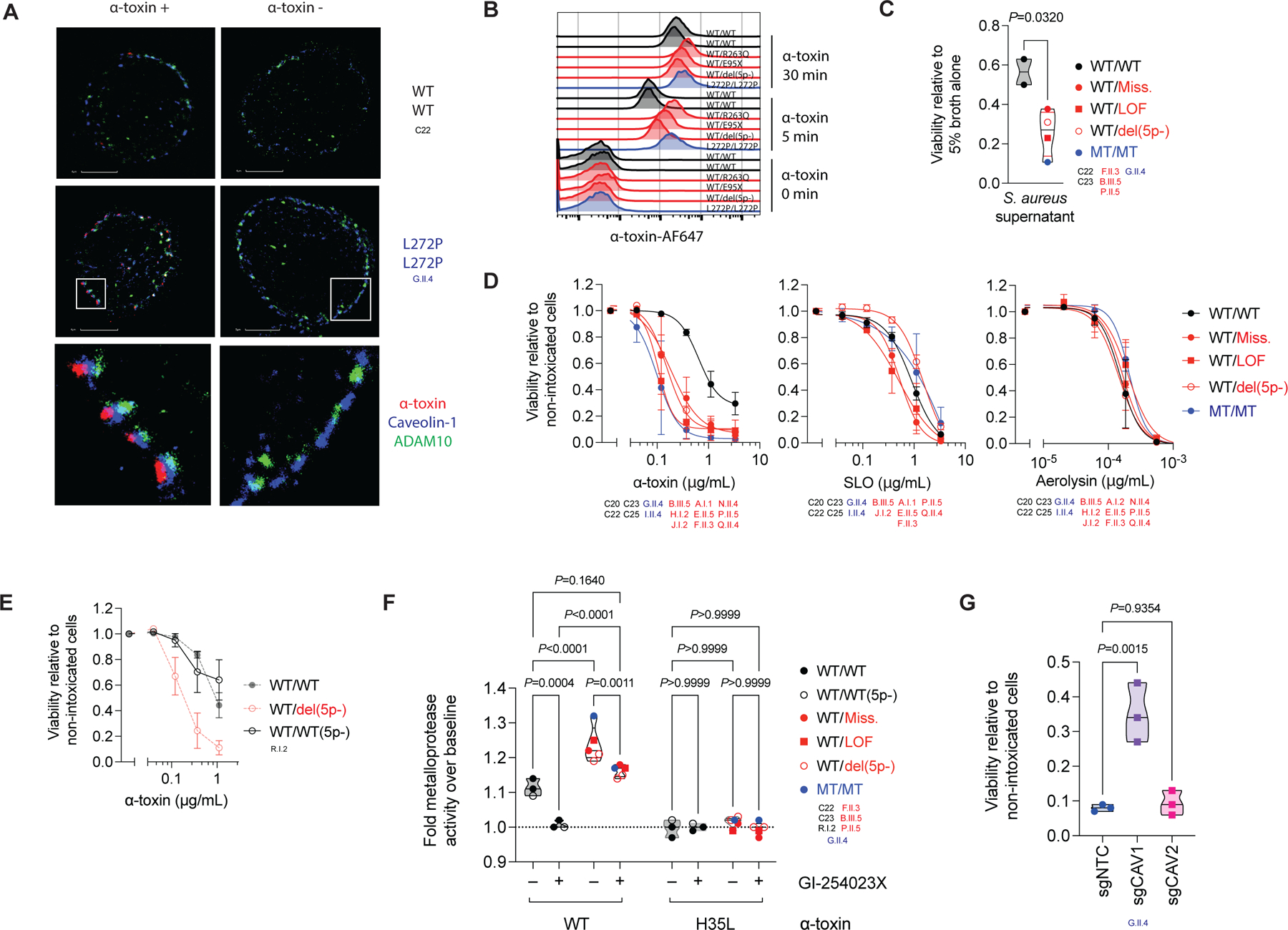

Figure 6. OTULIN haploinsufficiency impairs intrinsic immunity to α-toxin in fibroblasts.

(A) Colocalization of α-toxin with ADAM10 and caveolin-1 in primary dermal fibroblasts (PDFs), visualized in high-resolution images acquired by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy, after 30 minutes of incubation in the presence or absence of α-toxin. (B) Binding of α-toxin in PDFs, as detected by flow cytometry. (C) Viability of PDFs following 2.5 h of incubation with culture supernatant from S. aureus (datapoints indicate the mean of N=3 replicates per patient, median per group). (D) Viability of PDFs following 24 h of incubation with recombinant microbial toxins (N=2–4 per group, mean ±SD per group). (E) Viability of PDFs from a 5p- syndrome patient with a breakpoint telomeric to OTULIN following 24 h of incubation with recombinant α-toxin, superimposed on that for healthy controls and 5p- patients with a breakpoint centromeric to OTULIN from panel (F) (N=3, mean ±SD). (F) Cell-surface metalloprotease activity in PDFs induced by wild type α-toxin (WT) or a toxoid mutant (H35L) following the treatment of cells with an ADAM10 inhibitor or carrier (datapoints indicate the mean of N=3 replicates per patient, median per group). (G) Viability of OTULIN-deficient PDFs treated with an sgRNA pool targeting CAV1 (sgCAV1), CAV2 (sgCAV2), or a non-targeting control sgRNA (sgNTC) following exposure to α-toxin (0.12 μg/mL; N=3, median). The statistical significance of differences was assessed in Student’s t-tests (C), or by ANOVA with Bonferroni (F) or Dunnett (G) post hoc corrections for multiple comparisons. See also Figure S6.

OTULIN haploinsufficiency impairs intrinsic immunity to α-toxin

We hypothesized that OTULIN haploinsufficiency confers a predisposition to α-toxin-induced cell death in the PDFs of the patients. Indeed, these cells displayed an enhanced susceptibility to S. aureus culture supernatant-elicited cytotoxicity (Figure 6C). This cytotoxicity was antagonized by prior treatment of the supernatant with α-toxin-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (Figure S6G), indicating a major contribution of α-toxin to cytotoxicity in these cells. OTULIN genotype-dependent susceptibility to α-toxin was confirmed with recombinant α-toxin (Figure 6D, S6H). The absence of a particular phenotype following the treatment of cells from patients with streptolysin O (SLO) and aerolysin — microbial toxins produced by other bacteria and not requiring specific proteinaceous host-cell surface receptors (59) — indicates a specific susceptibility of the OTULIN-haploinsufficient PDFs from patients to α-toxin (Figure 6D, S6H). Normal susceptibility to α-toxin was observed in PDFs from a 5p- syndrome patient carrying two copies of the OTULIN gene, confirming the OTULIN-dependence of the phenotype (Figure 6E, S6I). α-toxin elicited higher levels of cell surface metalloprotease activation in PDFs from the patients than in those of healthy controls (Figure 6F) (55). Again, a 5p- syndrome patient carrying two copies of the OTULIN gene behaved like controls (Figure 6F). Activity levels were correlated with ADAM10 levels following α-toxin binding (Figure S6J). Prior treatment of the PDFs with an ADAM10-selective inhibitor blocked α-toxin-induced metalloprotease activation completely in controls, but activation levels in patients were decreased only slightly, to those in untreated controls (Figure 6F). Moreover, to various extents, ADAM10 inhibition protected the patients’ PDFs against α-toxin cytotoxicity (Figure S6K). Prior treatment with cyclodextrin, a chemical product disrupting caveolin-1-enriched membrane microdomains (60), protected PDFs from the patients against α-toxin-induced cytotoxicity (Figure S6K). The susceptibility of an OTULIN-deficient PDF cell line was partially rescued by knocking out CAV1 but not CAV2 (Figure 6G, S6L), further supporting a facilitating role of caveolin-1 in α-toxin cytotoxicity (54). Consistent with the low levels of caveolin-1 in hematopoietic cells from the patients, these cells displayed no OTULIN-dependent susceptibility to α-toxin (Figure S6M). Murine PDFs, unlike their human counterparts, were resistant to α-toxin-elicited cell death regardless of Otulin genotype (Figure S6N). Thus, OTULIN haploinsufficiency results in a human-specific cell-intrinsic susceptibility of non-hematopoietic cells to the major S. aureus virulence factor, α-toxin.

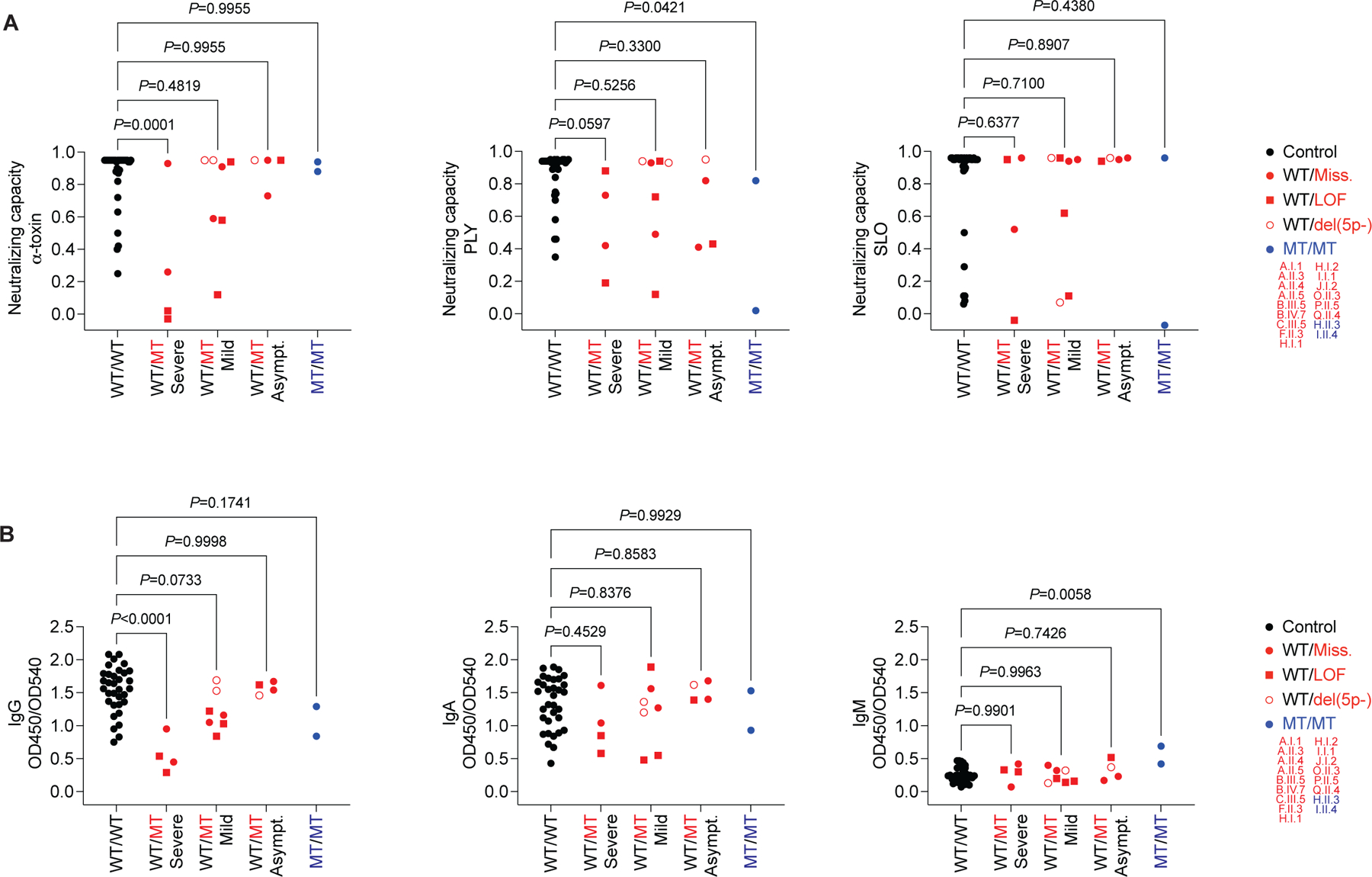

α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies rescue OTULIN haploinsufficiency

Colonization and infection with S. aureus elicit α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies in an age-dependent manner (61). We hypothesized that α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies in the plasma of adult symptomatic and asymptomatic heterozygotes might contribute to the incomplete clinical penetrance of OTULIN haploinsufficiency (Figure 1B–D, F) (12). Routine measurements of immunoglobulin levels and vaccine responses revealed no defects in the patients (SM). Plasma α-toxin-neutralizing capacity in asymptomatic carriers was similar to that of healthy controls, whereas this capacity was significantly lower in patients (õne fifth that in healthy controls; Figure 7A, S7A). The lower neutralizing capacity in the patients was specific for α-toxin, because the plasma of the patients neutralized SLO and pneumolysin normally (Figure 7A, S7A). In healthy controls, plasma α-toxin-neutralizing capacity was largely driven by IgG (Figure S7B). In patients, anti-α-toxin IgG levels were significantly lower than those in healthy controls, whereas IgA and IgM levels were unaffected (Figure 7B, S7C, D). The anti-α-toxin IgG levels in asymptomatic carriers were like those of healthy controls (Figure 7B, S7C, D) (61). Similar observations were made following correction for sample-specific total IgG levels (Figure S7E). Thus, naturally elicited α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies can rescue OTULIN haploinsufficiency in vivo, thereby contributing to incomplete penetrance.

Figure 7. α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies rescue OTULIN haploinsufficiency.

(A) Capacity of plasma at a dilution of 1:300 to neutralize the hemolytic activity of α-toxin (20 ng/mL), pneumolysin (PLY, 0.67 ng/mL), and streptolysin O (SLO, 42 ng/mL) in rabbit erythrocytes. (B) Anti-α-toxin immunoglobulin levels in plasma at a dilution of 1:750. We analyzed plasma from adult patients, relatives, and controls. The statistical significance of differences was determined by ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. See also Figure S7.

Discussion

We tested the hypothesis that some patients from our cohort with severe staphylococcal disease suffered from IEIs. Using an unbiased approach, we detected a genome-wide enrichment in very rare, deleterious heterozygous OTULIN variants in the cohort. We identified haploinsufficiency for OTULIN as a genetic etiology of severe staphylococcal disease. AR OTULIN deficiency results in life-threatening autoinflammation, manifesting early in life as ORAS (29–32). By contrast, patients with AD OTULIN deficiency typically presented with severe disease triggered by S. aureus infections. Most of the patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency experienced their first episode of disease during adolescence. Necrosis was a clinical hallmark of disease in the probands. Some patients were not diagnosed with S. aureus infections, suggesting that low-grade infectious or, perhaps, non-infectious triggers might be at work. AD OTULIN deficiency is clinically expressed in a tissue-specific manner because the skin and/or lungs are the affected organs in all patients. The pedigrees reported in our study displayed variable degrees of penetrance and expressivity. Such observations are common in situations of haploinsufficiency (62, 63). We show that naturally elicited α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies can rescue OTULIN haploinsufficiency and we suspect that declining levels of such antibodies may contribute to recurrent episodes of severe staphylococcal disease in some patients. We estimate the clinical penetrance of AD OTULIN deficiency at about 30%. This estimate of clinical penetrance mirrors our findings for individuals with 5p- syndrome. It is difficult to establish causal relationships between individual genes and specific phenotypes in patients with chromosomal deletion syndromes. Clinical manifestations of a monogenic disorder in a chromosomal deletion syndrome have also been reported for GATA3 haploinsufficiency (64). Our observations suggest that the study of rare IEIs can help to clarify phenotypes seen in individuals with more common chromosomal abnormalities.

In ORAS patients, autoinflammation results from the defective downregulation of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory signaling in hematopoietic cells, particularly those of the myeloid lineage (29–32). OTULIN deficiency causes a gene dosage-dependent accumulation of M1-Ub, but OTULIN haploinsufficiency is both clinically and biochemically silent for TNF-induced signaling events, instead causing a predisposition to infection. The apparent paradox of autoinflammation and immunodeficiency within the spectrum of clinical phenotypes of OTULIN deficiency is also observed in patients with HOIL1 and HOIP deficiencies, which greatly decrease the levels of M1-Ub (46, 65). The combination of autoinflammation and immunodeficiency in HOIL1 and HOIP deficiencies highlights the complex role of LUBAC in maintaining the cell type-specific balance between inflammation and immunity. Inflammation is regulated by two other deubiquitinases in addition to OTULIN: A20 and CYLD. Phosphorylated A20 preferentially cleaves K63-Ub in cells (66, 67). CYLD hydrolyzes K63-Ub and M1-Ub (68). AD A20 deficiency causes an autoinflammatory condition resembling Behçet’s disease (69), whereas AD CYLD deficiency results in cylindromatosis of the skin (70). AR HOIL1, HOIP, and OTULIN deficiencies and AD A20 deficiency are systemic disorders. Conversely, AD OTULIN and CYLD deficiencies result in tissue-specific disease. OTULIN and CYLD bind HOIP in a mutually exclusive manner (71). The detection of CYLD bound to M1-Ub reveals another, LUBAC-independent, layer of crosstalk between the two deubiquitinases. CYLD activity and specificity were recently shown to be regulated by phosphorylation and ubiquitin-binding CAP-Gly domains (72). We speculate that, with insufficient amounts of OTULIN, phosphorylated CYLD primed for activity towards K63-Ub is quenched by M1-Ub. The accumulation of caveolin-1 in dermal fibroblasts observed in patients with OTULIN deficiency probably results from disruption of the polyubiquitination of this molecule.

Human OTULIN haploinsufficiency is an inborn error of cell-intrinsic immunity to S. aureus infection. Staphylococcal disease displays a remarkable organ tropism, affecting the skin and lungs in particular (1). Tissue barrier disruption is a hallmark of severe staphylococcal disease (73). α-toxin is a key staphylococcal virulence factor that contributes to severe disease (73–76) and can injure non-hematopoietic cells (54, 73, 77, 78). The mechanism underlying the impairment of staphylococcal immunity in OTULIN haploinsufficiency is reminiscent of that involved in cell-intrinsic immunodeficiencies conferring susceptibility to viral infections (79–81). In the absence of sufficient levels of α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies, susceptibility to staphylococcal disease in patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency is driven by a defect of cell-intrinsic immunity to the α-toxin of the pathogen. In patients with OTULIN haploinsufficiency, caveolin-1 accumulates specifically in non-hematopoietic cells. Caveolin-1 clusters with α-toxin and the retention of ADAM10 at the surface of the patients’ cells predisposes these cells to α-toxin-induced cell death (82, 83). Caveolin-1 accumulation is observed in the cells of patients with either bi- or monoallelic OTULIN deficiencies. The late-onset infectious phenotype in patients with AD OTULIN deficiency may be overshadowed by the early-onset severe autoinflammatory manifestations in ORAS or compensated for by the presence of α-toxin-neutralizing antibodies. Consistent with this view, we also identified a pediatric homozygous carrier of a moderately hypomorphic OTULIN variant with an infectious phenotype indistinguishable from that of our haploinsufficient probands, with no autoinflammatory features. This work provides a direct demonstration of a defined host characteristic predisposing humans to adverse events elicited by a specific bacterial virulence factor.

S. aureus is a pathogen of paramount significance in human health (1). In the face of a globally emerging epidemic of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains (18), innovative strategies for treating and preventing infection are needed (84). In the presence or absence of documented S. aureus infections, OTULIN-haploinsufficient patients with severe necrosis may benefit from combined antibiotic and steroid therapy, together with α-toxin-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (85). Despite clear public health needs, no effective S. aureus vaccine has yet been approved (86). Humans are the main reservoir of S. aureus, and the pathogen is highly adapted to its human host (77, 78). Mice are naturally resistant to S. aureus infection (87). The principal mechanistic differences in hematopoietic immunity to staphylococcal infections between humans and mice have been characterized (77, 78). By contrast, the mechanisms of cell-intrinsic immunity in non-hematopoietic cells have been little studied in either humans or mice (80, 88–90). Staphylococcal virulence factors, such as α-toxin, are considered potential targets for strategies aiming to treat and prevent infection (77, 78). For many of these virulence factors, and cytotoxins in particular, one or more aspects of the interaction with the host are human-specific (78, 91). Murine ADAM10 can interact with α-toxin (55). However, OTULIN haploinsufficiency reveals a layer of human specificity at the interface between α-toxin and its human non-hematopoietic target cells. OTULIN haploinsufficiency demonstrates the contribution of S. aureus toxins to the pathophysiology of severe disease in humans. The experiment of Nature described here identifies a mechanism of human cell-intrinsic immunity to S. aureus infections and highlights the potential for interfering with the staphylococcal α-toxin for treating and preventing disease (85, 92).

Materials and methods

Human subjects

Informed consent was obtained from each patient, in accordance with local regulations, and a protocol for research on human subjects was approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) of Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM, protocol C10–16) and The Rockefeller University (protocols JCA-0698 and JCA-0695).

Whole-exome sequencing, breakpoint determination, and variant enrichment analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood. Whole-exome sequencing and breakpoint determinations are detailed in the SM. A gene-based enrichment analysis was performed on the cohort of 105 patients with severe staphylococcal disease, together with 1,274 individuals with Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD) or suffering from tuberculosis (TB) as controls. Rare variants (MAF < 1x10−5 in the gnomAD database (20)) predicted to be damaging (combined annotation-dependent depletion score (CADD) > mutation significance cutoff (MSC) (21)) were retained (Table S1) (23). The proportions of individuals with rare damaging variants in the cohort and the controls were compared by logistic regression with likelihood ratio tests (Table S2). The first five principal components of the PCA were systematically included in the logistic regression model to account for the ethnic heterogeneity of the cohorts, as previously described (93). Genes were then tested under a dominant genetic model. Four carriers, three of whom carried heterozygous variants, were identified amongst the cases. No carriers were identified amongst the controls. We then performed the same analysis again, but with the addition of 2,504 individuals from 1,000 Genomes Project phase 3 (25) to our control dataset (26).

Cell culture

Primary dermal fibroblasts (PDFs) were obtained from skin biopsy specimens and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) (Gibco) unless otherwise specified. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% HI-FBS unless otherwise specified. Immortalized fibroblasts were generated by transformation with SV40 as previously described (94) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS. HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS.

Generation of OTULIN constructs, transfection, transduction, and nucleofection

The human canonical OTULIN cDNA open reading frame clone was amplified from pCMV6-Entry FAM105B (OriGene) and inserted into the pCMV6-AN-Myc-DDK-tagged vector (OriGene) or pLentiIII-UBC (Abmgood). Site-directed mutagenesis to generate the OTULIN variants present in the patients was performed by a modified overlap-extension PCR-based method (95). All constructs were validated by Sanger sequencing. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected in the presence of Lipofectamine LTX (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For lentiviral transductions, semi-confluent HEK293T cells were cotransfected with OTULIN, GAG, POL, and ENV plasmids. The supernatant was collected at 48 hours and 72 hours and concentrated with a Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech). A ten-fold dilution (by volume) of the lentivirus preparation was added to semi-confluent immortalized fibroblasts plated on six-well plates. Transduced cells were selected with puromycin (Invitrogen). PDFs were mixed with gene knockout kit V2 single guide RNA pools (Synthego) in the presence of TrueCut Cas9 protein V2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), or with pCMV6 expression vectors, and nucleofected with the basic nucleofector kit for primary mammalian fibroblasts (Lonza) on a Nucleofector 2b device (Lonza).

NF-κB inhibition assay and linear deubiquitinase assay

HEK293T cells in 96-well plates were transiently cotransfected with pCMV6 vectors containing the OTULIN cDNA variants, the NF-κB firefly luciferase plasmid pGL4.32, and the Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRLTK) as an internal control. The cells were stimulated, 24 hours after transfection, by incubation with 20 ng/mL TNF in minimal medium (1% FBS) for an additional 24 hours. The ratio of firefly-to-Renilla luciferase expression was assessed with the Dual-Glo Luciferase assay (Promega) on a bioluminescence plate reader. Data were normalized against the inhibitory activity of cells transfected with a vector encoding the OTULIN reference cDNA. For linear deubiquitination assays, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pCMV6 vectors containing the OTULIN cDNA variants, HOIL-1, HOIP, SHARPIN and linear ubiquitin (UbK0) and harvested after 48 hours. Whole-cell lysates (WCLs) were prepared with WCL buffer A (Table S4). For immunoprecipitation, anti-M1-Ub antibody was added and the lysates were incubated overnight at room temperature. Dynabeads™ Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) beads were added to the samples, which were then incubated for one hour at room temperature. The beads were then washed with WCL buffer A (Table S4) and resuspended in 2 x NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with DTT. The antibodies used are described in Table S3.

Reverse transcription and PCR

Total RNA was extracted from transiently transfected HEK293T cells or from PDFs with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription was performed with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and random hexamers. Quantitative PCR was performed with the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The following TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used: OTULIN (Hs01113237_m1); GUSB (Hs00939627_m1); GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1).

Whole-cell lysates, SDS-PAGE, and western blotting

Transiently transfected HEK293T cells were harvested and lysed in whole cell lysate (WCL) buffer B (Table S4). PDFs were synchronized by incubation in DMEM containing 1% FBS for 24 h before trypsin treatment and were then lysed in WCL buffer C (Table S4) with sonication to clear the supernatants. Immortalized fibroblasts were stimulated with 10 ng/mL TNF and lysed in WCL buffer D (Table S4). Monocytes were obtained from freshly thawed PBMCs with the Pan Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and lysed in WCL buffer C (Table S4) with sonication to clear the supernatants. Laemmli buffer (BioRad) supplemented with DTT was added to the clarified lysates. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE transferred onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked by incubation in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% BSA and incubated overnight with the primary antibody, followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Intensity analyses were performed with ImageStudioLite (LI-COR). The antibodies used are described in Table S3.

Cytometry by time-of-flight

Freshly thawed PBMCs were incubated with Fc block and then with a panel of metal-conjugated antibodies, as described elsewhere (96). The antibodies used are described in Table S3. Batch-integrated unsupervised clustering analysis was conducted with the iMUBAC pipeline (45). The analysis included 29 adult controls (nine studied in replicate) and nine pediatric controls (all under the age of 18 years) studied across seven batches of experiments, four patients with heterozygous mutations of OTULIN and two 5p- patients studied in two batches of experiments. Clusters were identified manually and renamed based on their marker expression patterns.

Flow cytometry

Freshly thawed PBMCs were rested for 3 hours and were then stimulated for 90 minutes with 20 ng/mL TNF (R&D Systems) or 1 ng/mL LPS (InvivoGen). The reaction was stopped by washing the cells with PBS, and the cells were then subjected to live/dead staining. Cells were subsequently stained with surface markers and washed. They were then permeabilized and stained with Phosflow Perm Buffer (BD) or Intracellular Staining Perm Wash Buffer (BioLegend). PDFs were synchronized by incubation in DMEM supplemented with 1% HI-FBS for 24 hours and were then harvested by trypsin treatment. The fibroblasts were stained, fixed and acquired on a LSR-Fortessa cytometer (BD). All flow cytometry results were analyzed with FlowJo (version 10). The antibodies used are described in Table S3.

Cytokine detection

PDFs were synchronized by incubation in DMEM supplemented with 1% HI-FBS for 24 hours before stimulation. At steady state and after 6 hours of stimulation with 20 ng/mL TNF (R&D Systems), supernatants were harvested, and the levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were assessed with the IL-6 and IL-8 Human ELISA kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Freshly thawed PBMCs were left unstimulated or stimulated with 20 ng/mL TNF (R&D Systems), 10 ng/mL IL-1β (R&D Systems), HKSA (heat-killed S. aureus; MOI: 10; InvivoGen), or 1 ng/mL LPS (InvivoGen) for 6 hours. Supernatants were harvested, and chemokines and cytokines were detected with LEGENDPlex Human Inflammation Panel 1 (BioLegend).

Induced pluripotent stem cells

The generation and culture of iPSCs, their differentiation into macrophages, and the phagocytosis and H2O2 production assays are described in the SM.

Transcriptional and proteomic analyses

Transcriptional analyses in PDFs and PBMCs, single-cell RNA-sequencing on PBMCs, and global proteomics analyses of PDFs are described in the SM.

Caveolin-1 immune purification from whole-cell lysates

PDFs were synchronized by incubation in DMEM containing 1% HI-FBS for 24 hours and were then harvested by trypsin treatment. Cell pellets were lysed in WCL buffer C (Table S4) with sonication to clear the supernatants. Cleared WCLs were incubated overnight at 4°C with Protein A Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) conjugated to the monoclonal anti-caveolin-1 antibody or an isotype control. The samples were then eluted from the beads with 50 mM glycine, pH 2. The antibodies used are described in Table S3. The immunopurification products (IPs) were then split into portions for loading onto a gel or direct in-solution proteomic analyses, as described in the SM.

Deubiquitination of purified caveolin-1

Caveolin-1 IPs were treated with recombinant deubiquitinases as described elsewhere (97). Briefly, immunopurified caveolin-1 was incubated with deubiquitinases at 37°C for 30 minutes. Recombinant USP2, AMSH, and OTULIN (UbiCREST Deubiquitinase Enzyme Set, R&D Systems) were used at a final concentration of 1x. Recombinant His-CYLD (R&D Systems) was used at a final concentration of 1 μM. Purified polyubiquitin chains were deubiquitinated by incubating tetra-M1-, K48- and K63-Ub chains (R&D Systems) at a concentration of 3 μM with deubiquitinases. Following the enzymatic reactions, sample buffer containing DTT was added, and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, as described above.

Linear ubiquitin-selective tandem Ub-binding entity assay

For M1-Ub pulldown, immortalized fibroblasts were lysed in WCL buffer E (Table S4) containing FLAG-tagged M1-Ub-selective tandem Ub-binding entity (TUBE) (LifeSensors). Supernatants were cleared by centrifugation and incubated with Anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads (Sigma Aldrich) for 2 hours at 4°C. The beads were washed with WCL buffer E (Table S4), and resuspended in 1 x Laemmli buffer without reducing agent. For M1-Ub quantification, we used an input of ~0.5 mg per sample. For the identification of peptides bound to M1-Ub, we used an input of ~2 mg per sample. M1-Ub quantification and the identification of peptides bound to M1-Ub by means of absolute quantification (AQUA) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) are described in the SM. For western-blot analyses, beads were resuspended in sample buffer containing DTT and samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, as described above.

Immunofluorescence assays

Immortalized fibroblasts were cultured on glass coverslips for the staining of M1-Ub, K63-Ub, and caveolin-1. The cells were fixed in methanol, blocked by incubation with 1% BSA and incubated overnight with primary antibodies and CellMask™ deep red plasma membrane stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by secondary antibodies and DAPI. Specimens were examined either with an Imager Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, for M1-Ub aggregate number quantifications) or a LSM800 laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, for caveolin-1 and M1-Ub or K63-Ub colocalization experiments). The numbers of ubiquitin aggregates per cell were quantified using CellProfiler (http://www.cellprofiler.org/). Nuclei and cell boundaries were segmented to identify OTULIN-positive cells and to attribute M1-Ub-positive aggregates to parental cells. Immunofluorescence deubiquitination and competition assays are described in the SM. For α-toxin colocalization and binding experiments, PDFs were synchronized by incubation in DMEM containing 1% HI-FBS for 24 hours before trypsin treatment. PDFs were incubated with 10 µg/mL α-toxin-Cys-AF647, washed, and then fixed with methanol. After incubation with antibodies and DAPI, cells were seeded in a slide chamber. Images were acquired on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) and NanoImager (ONI). In parallel, the cells were recorded on a FACS Verse flow cytometer (BD). Confocal images were analyzed with Image J Fiji software and the JACoP colocalization analysis plugin (98). The antibodies used are described in Table S3.

Cell viability assays

PDFs were plated in a microtiter plate and synchronized in DMEM containing 1% HI-FBS and 25 mM DMEM for 24 hours and were then incubated for 2.5 hours with 5–10% crude bacterial culture supernatant or for 24 hours with recombinant toxins, or with 100 ng/mL TNF (R&D Systems) plus 1 μM BV6 (ApexBio) at 37°C, under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Bacterial supernatants were neutralized by incubation for 15 minutes in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS plus 100 μg/mL monoclonal antibodies (92, 99). PBMCs and iPSC-derived macrophages were incubated with α-toxin for 2 hours and 24 hours, respectively, at 37°C, under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For the inhibition of α-toxin cytotoxicity, PDFs were treated for 1 hour with 20 μM GI-254023X (R&D Systems) or DMSO before adding 1.1 μg/mL α-toxin, or for 2 hours with 1 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma) followed by washing and the addition of 1.1 μg/mL α-toxin. Viability was assessed with the CellTiterGlo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) and expressed relative to cells not incubated with the toxin or supernatant. Four-parameter non-linear regression analyses were performed to obtain half-maximum effective concentrations (EC50). The expression of recombinant toxins and the generation of bacterial culture supernatant are described in the SM.

Metalloprotease activity assays

PDFs were plated in a microtiter plate and synchronized by incubation in DMEM containing 1% HI-FBS and 25 mM DMEM for 24 hours. They were then treated for 1 hour with 20 μM GI-254023X (R&D Systems) or DMSO before the addition of 3.3 μg/mL wild-type or H35L-toxoid α-toxin. After 2 hours of incubation at 37°C, under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2, cells were washed with 25 mM Tris (pH 8), and 10 μM Mca-PLAQAV-Dpa-RSSSR-NH2 Fluorogenic Peptide Substrate (R&D Systems) was added. After incubation for 30 minutes, fluorescence intensity was measured on a monochromator-based microplate reader and expressed relative to cells not incubated with the toxin.

Mice

The generation and use of Otulin-haploinsufficient mice is described in the SM.

Anti-α-toxin immunoglobulins

The capacity of the plasma to neutralize microbial toxins was assessed with rabbit erythrocytes, as described in the SM. Pooled plasma was depleted of IgG with HiTrap Protein G HRP columns (GE Healthcare). Anti-α-toxin immunoglobulin levels were measured by ELISA, as described in the SM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their families, and the US 5p- Syndrome Society for their trust and collaboration. We thank Martijn van Aartrijk, Selket Delafontaine, Mikko Muona, Emmanuelle Jouanguy, Yelena Nemirovskaya, Mark Woollett, Marjan Wassenberg, Marc Bonten, Suzan Rooijakkers, Kok van Kessel, and Jos van Strijp for their assistance and support. We thank the Flow Cytometry and Genomics Resource Centers at The Rockefeller University.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (UL1TR001866 to The Rockefeller University), the Sackler Center for Biomedicine and Nutrition at the Center for Clinical and Translational Science at The Rockefeller University and the Shapiro-Silverberg Fund for the Advancement of Translational Research (to A.N.S.), NIH P01AI061093 (to J.-L.C.), the Square Foundation, the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-IAHU-01), the Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID), the French Foundation for Medical Research (EQU201903007798), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the St. Giles Foundation, The Rockefeller University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the Paris Cité University, the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (P30CA016087 to the NYU Langone’s Rodent Genetic Engineering Laboratory), the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation and the International PhD program of the Imagine Institute (to A-L.N.), the David Rockefeller Graduate Program (to M.O.), the New York Hideyo Noguchi Memorial Society (to M.O.), the Funai Foundation for Information Technology (to M.O.), the Honjo International Scholarship Foundation (to M.O.), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship award (LACEY19FO, to K.A.L.), the William C. and Joyce C. O’Neil Charitable Trust (to T.B.), the Memorial Sloan Kettering Single Cell Sequencing Initiative (to T.B.), the Hospital Research Funds at the Pediatric Research Center at the Helsinki University Hospital (to M.R.J.S.), the Foundation for Pediatric Research of Finland (to M.R.J.S.). C.W. serves as a member of the European Reference Network for Rare Immunodeficiency, Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases (739543). The work was supported in part by the ERC Start grant IMMUNO (ERC-2010-StG_20091118, to A.L.), the VIB Grand Challenges (to A.L., S.H-B., R.S.), the KU Leuven BOFZAP start-up grant (to S.H-B.), National Fund for Scientific Research senior clinical investigator fellowships (1805518N, to R.S.; and G0B5120N, to I.M.), National Fund for Scientific Research grants (G0E8420N and G0C8517N, to I.M.), a KU Leuven C1 grant (to I.M.), and the ERC Start grant MORE2ADA2 (ERC-2020-StG_ 948959, to I.M.). I.M. is a member of ERN-RITA. D.B. is supported by the NIH (R01 AI148963) and a founder of Lab11 Therapeutics, Inc. The S. aureus work in the Torres laboratory is funded by the NIH (R01 AI099394, R01 AI105129, R01 AI121244, R01 AI137336 and R01 AI140754, to V.J.T). V.J.T. is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. A.N.S. was supported in part by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant No. 789645), the Dutch Research Council Talent Program (NWO Rubicon grant No. 019.171LW.015, partially non-stipendiary), and the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO Long-Term Fellowship grant No. ALTF 84-2017, non-stipendiary).

Footnotes

Competing interests: V.J.T. is an inventor on patents and patent applications filed by New York University, which are currently under commercial license to Janssen Biotech Inc. Janssen Biotech Inc. provides research funding and other payments associated with the licensing agreement. D.B. is a founder of Lab11 Therapeutics Inc. None of the other authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

Data and material availability: Plasma, cells, and genomic DNA are available from J-L.C. under a material transfer agreement with The Rockefeller University. The materials and reagents used are almost exclusively commercially available and nonproprietary. Raw RNA sequencing data have been deposited to the NCBI BioProject database and are available under project number PRJNA818002. Proteomic data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository and are available with dataset identifier PXD032727. All other data are available in the main text or in the SM.

References and notes

- 1.Lowy FD, Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339, 520–532 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillet Y et al. , Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 359, 753–759 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidron AI, Low CE, Honig EG, Blumberg HM, Emergence of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 as a cause of necrotising community-onset pneumonia. Lancet Infectious Diseases 9, 384–392 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lina G et al. , Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 29, 1128–1132 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenesch F et al. , Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis 9, 978–984 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boisson B, The genetic basis of pneumococcal and staphylococcal infections: inborn errors of human TLR and IL-1R immunity. Hum Genet 139, 981–991 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangye SG et al. , The Ever-Increasing Array of Novel Inborn Errors of Immunity: an Interim Update by the IUIS Committee. J Clin Immunol 41, 666–679 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picard C et al. , Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with IRAK-4 deficiency. Science 299, 2076–2079 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picard C et al. , Clinical features and outcome of patients with IRAK-4 and MyD88 deficiency. Medicine (Baltimore) 89, 403–425 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picard C, Casanova JL, Puel A, Infectious diseases in patients with IRAK-4, MyD88, NEMO, or IκBα deficiency. Clin Microbiol Rev 24, 490–497 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Bernuth H et al. , Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science 321, 691–696 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel L et al. , Human Adaptive Immunity Rescues an Inborn Error of Innate Immunity. Cell 168, 789–800.e710 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puel A et al. , Recurrent staphylococcal cellulitis and subcutaneous abscesses in a child with autoantibodies against IL-6. J Immunol 180, 647–654 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwerd T et al. , A biallelic mutation in IL6ST encoding the GP130 co-receptor causes immunodeficiency and craniosynostosis. J Exp Med 214, 2547–2562 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Béziat V et al. , A recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome by disruption of ZNF341-dependent STAT3 transcription and activity. Sci Immunol 3, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minegishi Y et al. , Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature 448, 1058–1062 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer S et al. , Loss of the interleukin-6 receptor causes immunodeficiency, atopy, and abnormal inflammatory responses. J Exp Med 216, 1986–1998 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLeo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF, Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375, 1557–1568 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shallcross LJ, Fragaszy E, Johnson AM, Hayward AC, The role of the Panton-Valentine leucocidin toxin in staphylococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 13, 43–54 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karczewski KJ et al. , The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itan Y et al. , The mutation significance cutoff: gene-level thresholds for variant predictions. Nat Methods 13, 109–110 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kircher M et al. , A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 46, 310–315 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P et al. , PopViz: a webserver for visualizing minor allele frequencies and damage prediction scores of human genetic variations. Bioinformatics 34, 4307–4309 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Notarangelo LD, Bacchetta R, Casanova JL, Su HC, Human inborn errors of immunity: An expanding universe. Sci Immunol 5, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auton A et al. , A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boisson-Dupuis S et al. , Tuberculosis and impaired IL-23-dependent IFN-γ immunity in humans homozygous for a common TYK2 missense variant. Sci Immunol 3, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keusekotten K et al. , OTULIN antagonizes LUBAC signaling by specifically hydrolyzing Met1-linked polyubiquitin. Cell 153, 1312–1326 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivkin E et al. , The linear ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinase gumby regulates angiogenesis. Nature 498, 318–324 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damgaard RB et al. , OTULIN deficiency in ORAS causes cell type-specific LUBAC degradation, dysregulated TNF signalling and cell death. EMBO Mol Med 11, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damgaard RB et al. , The Deubiquitinase OTULIN Is an Essential Negative Regulator of Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Cell 166, 1215–1230.e1220 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabavi M et al. , Auto-inflammation in a Patient with a Novel Homozygous OTULIN Mutation. J Clin Immunol 39, 138–141 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Q et al. , Biallelic hypomorphic mutations in a linear deubiquitinase define otulipenia, an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 10127–10132 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zinngrebe J et al. , Compound heterozygous variants in OTULIN are associated with fulminant atypical late-onset ORAS. EMBO Mol Med, e14901 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bousfiha A et al. , Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019 Update of the IUIS Phenotypical Classification. J Clin Immunol 40, 66–81 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eilertson KE, Booth JG, Bustamante CD, SnIPRE: selection inference using a Poisson random effects model. PLoS Comput Biol 8, e1002806 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rapaport F et al. , Negative selection on human genes underlying inborn errors depends on disease outcome and both the mode and mechanism of inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fadista J, Oskolkov N, Hansson O, Groop L, LoFtool: a gene intolerance score based on loss-of-function variants in 60 706 individuals. Bioinformatics 33, 471–474 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X et al. , High-resolution mapping of genotype-phenotype relationships in cri du chat syndrome using array comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Hum Genet 76, 312–326 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lejeune J et al. , [3 CASES OF PARTIAL DELETION OF THE SHORT ARM OF A 5 CHROMOSOME]. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci 257, 3098–3102 (1963). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niebuhr E, The Cri du Chat syndrome: epidemiology, cytogenetics, and clinical features. Hum Genet 44, 227–275 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerruti Mainardi P, Cri du Chat syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 1, 33 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mainardi PC et al. , The natural history of Cri du Chat Syndrome. A report from the Italian Register. Eur J Med Genet 49, 363–383 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seger R et al. , Defects in granulocyte function in various chromosome abnormalities (Down’s-, Edwards’-, Cri-du-chat syndrome). Klin Wochenschr 54, 177–183 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkins LE, Brown JA, Nance WE, Wolf B, Clinical heterogeneity in 80 home-reared children with cri du chat syndrome. J Pediatr 102, 528–533 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogishi M et al. , Multibatch Cytometry Data Integration for Optimal Immunophenotyping. J Immunol 206, 206–213 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boisson B et al. , Immunodeficiency, autoinflammation and amylopectinosis in humans with inherited HOIL-1 and LUBAC deficiency. Nat Immunol 13, 1178–1186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subramanian A et al. , Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayer A et al. , Caveolin-1 is ubiquitinated and targeted to intralumenal vesicles in endolysosomes for degradation. J Cell Biol 191, 615–629 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato M, Konuma R, Sato K, Tomura K, Sato K, Fertilization-induced K63-linked ubiquitylation mediates clearance of maternal membrane proteins. Development 141, 1324–1331 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uhlén M et al. , Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thul PJ et al. , A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 356, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rothberg KG et al. , Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell 68, 673–682 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim W et al. , Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell 44, 325–340 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilke GA, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Role of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 13473–13478 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inoshima I et al. , A Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxin subverts the activity of ADAM10 to cause lethal infection in mice. Nat Med 17, 1310–1314 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seilie ES, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxins: The interface of pathogen and host complexity. Semin Cell Dev Biol 72, 101–116 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moreno-Càceres J et al. , Caveolin-1 is required for TGF-β-induced transactivation of the EGF receptor pathway in hepatocytes through the activation of the metalloprotease TACE/ADAM17. Cell Death Dis 5, e1326 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan EM et al. , Epidermal growth factor receptor exposed to oxidative stress undergoes Src- and caveolin-1-dependent perinuclear trafficking. J Biol Chem 281, 14486–14493 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dal Peraro M, van der Goot FG, Pore-forming toxins: ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 77–92 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zidovetzki R, Levitan I, Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768, 1311–1324 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu Y et al. , Prevalence of IgG and Neutralizing Antibodies against Staphylococcus aureus Alpha-Toxin in Healthy Human Subjects and Diverse Patient Populations. Infect Immun 86, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]