Abstract

Intracellular bacteria have been found previously in one isolate of the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungus Gigaspora margarita BEG 34. In this study, we extended our investigation to 11 fungal isolates obtained from different geographic areas and belonging to six different species of the family Gigasporaceae. With the exception of Gigaspora rosea, isolates of all of the AM species harbored bacteria, and their DNA could be PCR amplified with universal bacterial primers. Primers specific for the endosymbiotic bacteria of BEG 34 could also amplify spore DNA from four species. These specific primers were successfully used as probes for in situ hybridization of endobacteria in G. margarita spores. Neighbor-joining analysis of the 16S ribosomal DNA sequences obtained from isolates of Scutellospora persica, Scutellospora castanea, and G. margarita revealed a single, strongly supported branch nested in the genus Burkholderia.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi are obligate biotrophs that belong to the order Glomales and develop in close relationship with the roots of about 80% of land plants. Fossil and molecular data have demonstrated that AM fungi are very ancient, dating back to 350 to 400 million years ago (28, 30). The success of AM fungi in evolution is mainly due to their central role in the capture of nutrients from the soil (29). Despite recent breakthroughs in our knowledge of the molecular basis of plant-fungus interactions (1, 12), many aspects of the biology of AM fungi, particularly their genomes, are still obscure due to their biotrophic status, their multinuclear condition, and an unexpected level of genetic variability (13, 15, 17).

A further level of complexity is due to the presence of cytoplasmic structures initially termed bacterium-like organisms (BLOs) that have been found in different AM fungal species (Glomus calidonium, Acaulospora laevis, Gigaspora margarita) by electron microscopy (7, 18, 21, 27). A combined morphological and molecular approach has shown that BLOs in the spores of G. margarita (isolate BEG 34) are true bacteria (6). Amplification of bacterial 16S RNA genes from total spore DNA followed by direct sequencing indicated a homogeneous bacterial population closely related to the genus Burkholderia (6). Attempts to isolate and grow these endobacteria from spores have been unsuccessful so far.

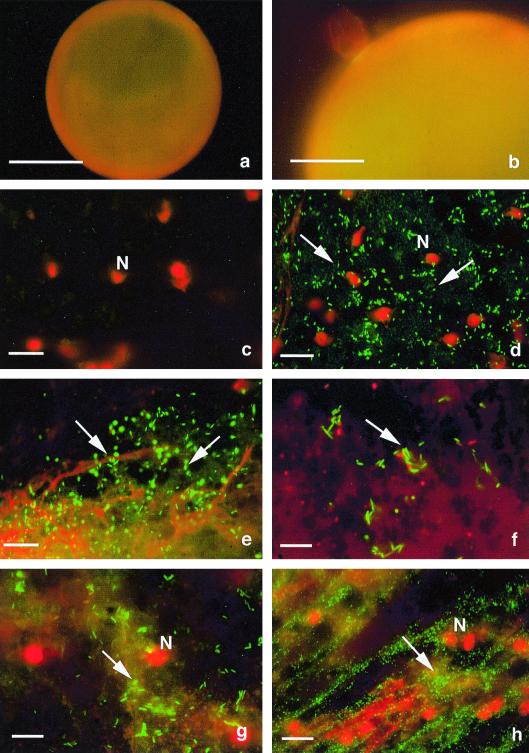

To determine whether intracellular bacteria occur sporadically in individual AM fungal isolates or are a common feature in the family Gigasporaceae, we investigated using morphological and molecular approaches, two more isolates of G. margarita, derived from distant geographic areas, and nine isolates belonging to five other AM species in the genera Gigaspora and Scutellospora (Table 1). Spores were picked with forceps, rinsed five times with sterile filtered distilled water, surface sterilized with 4% chloramine T and 0.04% streptomycin for 30 min, sonicated five times, and then rinsed five times (10 min each) with sterile filtered distilled water. To eliminate the possibility that contaminating bacteria were present on the fungal surface at the end of the sterilization procedure, spores from each of the isolates were stained with a Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes) as previously described (6) and were observed without prior crushing. In all cases, the spore surface was completely free of bacterial contaminants (Fig. 1a and b).

TABLE 1.

AM fungal isolates analyzed in this study

| Species | Origin | Isolatea | Supplier(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G. margarita Becker & Hall | New Zealand | BEG 34 | V. Gianinazzi-Pearson |

| G. margarita Becker & Hall | West Virginia | INVAM WV 205A | J. Morton |

| G. margarita Becker & Hall | Brazil | Personal collection | J. Dodd |

| G. rosea Nicolson & Schenck | Unknown | DAOM 194757b | D. Douds and G. Bécard |

| G. rosea Nicolson & Schenck | United States | BEG 9 | J. Dodd |

| G. rosea Nicolson & Schenck | United States | BEG 9 | V. Gianinazzi-Pearson |

| G. rosea Nicolson & Schenck | Florida | INVAM FL 185 | D. Douds |

| G. gigantea Gedermann & Trappe | Pennsylvania | HC/F E30 | D. Douds |

| G. decipiens Hall & Abbott | Unknown | BEG 45 | C. Leyval |

| S. persica (Schench & Nicol.) Walker & Sanders | Porto Caleri (Rovigo), Italy | HC/F E28 | V. Bianciotto |

| S. persica (Schench & Nicol.) Walker & Sanders | Migliarino (Pisa), Italy | HC/F E09 | V. Bianciotto |

| S. castanea Walker | France | BEG 1 | Biorize |

BEG, European Bank of Glomales; DAOM, Department of Agriculture, Ottawa, Mycology; INVAM, International Culture Collection of Arbuscular and Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi; HC/F, Herbarium Cryptogamicum Fungi, Department of Plant Biology, Turin Italy.

This isolate was originally received as G. margarita, but 18S rDNA and internal transcribed spacer sequence analyses demonstrated that it belongs to G. rosea (5; V. Bianciotto, E. Lumini, J. Morton, L. Lanfranco, and P. Bonfante, unpublished data)

FIG. 1.

Bacterial endosymbionts in the cytoplasm of manually crushed spores of six fungal isolates (e through h) stained with the Live/Dead Baclight kit and observed by using a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope with a View Scan DVC-250 confocal system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). Living bacteria fluoresce bright yellow-green under blue light, while dead bacteria fluoresce red under green light. (a and b) No contaminating bacteria were observed on the external surfaces of sterilized and sonicated spores of G. rosea (a) and G. margarita (WV 105A (b). Bars, 100 μm (a) and 50 μm (b). (c) No bacterial endosymbionts were detected in the cytoplasm of G. rosea BEG 9. Only the fungal nuclei (red masses) are visible. Bar, 10 μm. (d) Cytoplasm of a G. margarita WV 205A spore containing many living rod-shaped bacteria that fluoresce green (arrows) and fungal nuclei (red masses). Bar, 10 μm. (e) Cytoplasm of S. persica HC/F E09 containing numerous rod-shaped bacteria (arrows). The nuclei are broken, and red filaments of chromatin are visible. Bar, 10 μm. (f) Appearance of bacteria in S. persica HC/F E28. Bar, 7 μm. (g) S. castanea BEG 1 cytoplasm. Numerous living bacteria are present between the fungal nuclei. Bar, 7 μm. (h) Cytoplasm of G. gigantea containing a very high number of living bacteria that are smaller and rounder than the bacteria in the other isolates. Bar, 7 μm. N, nuclei.

Localization of endobacteria in AM fungal spores by fluorescence and in situ hybridization.

Fungal cytoplasm was released by crushing spores between a microscope glass slide and a coverslip. Staining with the fluorescent BacLight dye showed that intracellular bacteria were present in 7 of 11 fungal isolates (Fig. 1). The four isolates that did not contain bacteria all belonged to the species Gigaspora rosea (Fig. 1c). The endobacteria mostly fluoresced as green, rod-shaped spots (Fig. 1d, e, f, and g), indicating that they were alive. The bacteria were less numerous in Scutellospora persica HC/F E28 than in the other S. persica isolate (Fig. 1f). A very high number of endobacteria that were more round and smaller were found in the cytoplasm of Gigaspora gigantea (Fig. 1h).

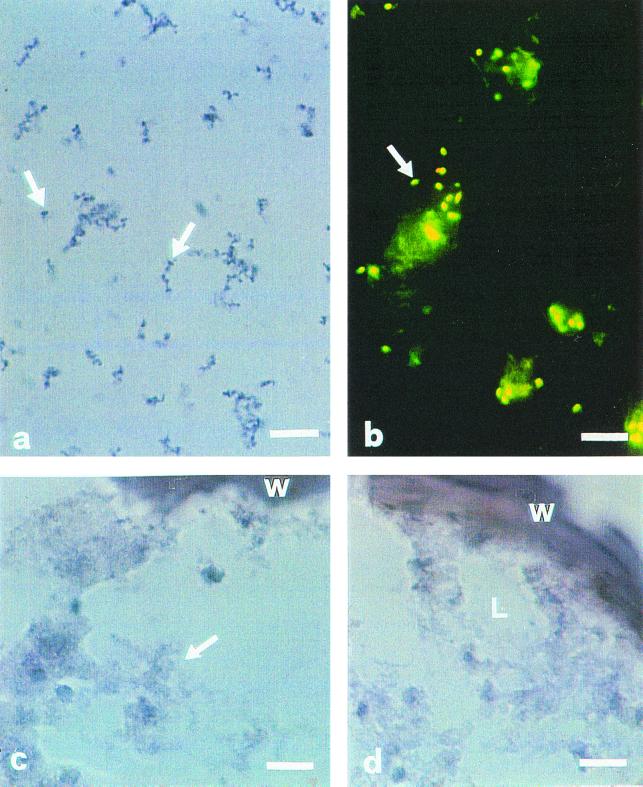

To confirm the identity and location of endobacteria in AM fungal spores, in situ hybridization experiments were performed with three isolates, G. margarita BEG 34 and WV 205A and G. rosea BEG 9. Oligonucleotide probes targeted to 16S rRNAs have been used successfully to detect and identify environmental nonculturable prokaryotes (3) and bacterial endosymbionts of insects (8, 9). The specific protocol described by Fukatsu et al. (9) using digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled probes was followed. A positive signal was obtained with G. margarita BEG 34 and WV 205A after hybridization with the oligonucleotide ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence BLOr, specifically designed for the bacterial endosymbiont of G. margarita BEG 34 (6). Blue rod-shaped spots were especially visible when they grouped together close to the fungal lipid droplets (Fig. 2a). Their shape and size (about 1 μm) corresponded well to those of endobacteria revealed with the fluorescent dye on unfixed spore sections from the same fungal isolates (Fig. 2b). Similar signals were also obtained by using as a probe oligonucleotide EUB338 (2), designed to bind to bacterial 16S rDNA (data not shown). No signal was found in control experiments in which the DIG-labelled probe was omitted (Fig. 2c). None of the probes gave hybridization signals in the cytoplasm of G. rosea (Fig. 2d).

FIG. 2.

In situ hybridization of intracellular symbiotic bacteria in spores of G. margarita BEG 34 and G. rosea BEG 9. BLOr (5′-GTCATCCACTCCGATTATTTA-3′) (6) hybridizes specifically with the 16S rRNA of the G. margarita endosymbiont and was used as probe. (a) In G. margarita a large number of blue rod-shaped spots (diameter, about 1 μm) (arrows) were visible in the fungal cytoplasm. They were especially visible when they grouped together in the cytoplasm. Bar, 10 μm. (b) The shape and position of spots correspond well with those of endobacteria revealed after Baclight kit staining of unfixed spores from the same fungal isolate. Bar, 7 μm. (c) No hybridization signal was obtained when the DIG-labelled probe was omitted. Bar, 10 μm. (d) No hybridization signal was obtained with the cytoplasm of G. rosea when the DIG-labelled BLOr probe was used. Bar, 10 μm. W, spore wall; L, lipid masses.

The in situ hybridization results provide important confirmation of the nature and topology of endobacteria in AM fungi. In fact, AM fungi and bacteria interact at different levels of cellular integration, ranging from apparently loose association through surface attachment to intimate and obligatory endosymbiosis (23). Therefore, the simultaneous presence of bacteria outside and inside the fungal cell requires careful experimental procedures to make sure that PCR amplification is targeted to the endosymbiotic bacterial DNA. The development of in situ protocols should also result in an important tool for investigating bacterial functions related to the expression of specific genes, some of which have been already characterized in the endosymbiotic bacteria of G. margarita BEG 34 (25).

Amplification of endobacterial 16S rDNA with universal and specific primers.

For crude DNA preparation, 10 spore samples were surface decontaminated as described above. Extreme care was taken to avoid subsequent bacterial contamination, and all steps were carried out in a laminar flow hood. DNA was extracted by the protocol described previously (17). Two sets of primers were used: the universal eubacterial 704f-1495r primer pair and the BLOf-BLOr primer pair, specifically designed for the bacterial endosymbiont of G. margarita BEG 34 (6). PCR amplifications were performed in a Hybaid Omnigene thermal cycler with the following parameters: 3 min at 95°C (one cycle); 45 s at 92°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 45 s at 72°C (40 cycles); and 5 min at 72°C (one cycle).

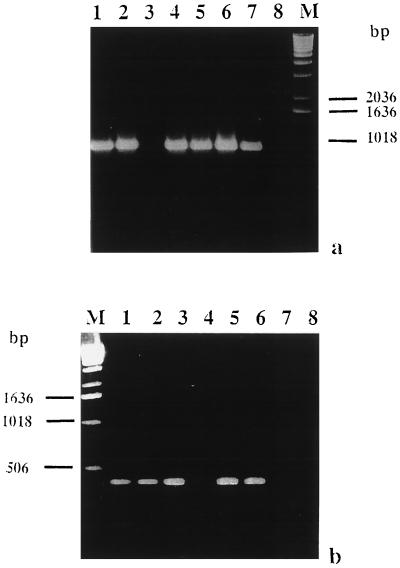

Universal bacterial primers 704f and 1495r were first used to investigate the presence of bacteria inside the AM fungal spores. These primers amplified a DNA fragment of the expected size (about 790 bp) from most isolates (Fig. 3a) Only the DNA in four G. rosea isolates could not be amplified with the universal bacterial primers, although their DNA were successfully amplified with primers for the fungal rDNA genes (data not shown). In addition, the DNA in G. rosea isolates and G. gigantea could not be amplified with primers BLOf and BLOr, whereas an amplified DNA fragment about 400 bp long was obtained from all other DNA samples (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

PCR experiments designed to reveal the presence of endobacteria in spores of different AM fungal isolates when two pairs of primers were used. (a) Agarose (1.2%) gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified with bacterial primers 704f and 1495r when the following templates were used: G. margarita WV 205A (lane 1), G. margarita Brazil isolate (lane 2), G. rosea BEG 9 (lane 3), S. persica HC/F E09 (lane 4), S. castanea BEG 1 (lane 5), G. decipiens (lane 6), G. gigantea (lane 7), and no DNA (lane 8). Lane M contained a 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco BRL). (b) Agarose (1.2%) gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified with primers BLOf and BLOr specific for the endobacteria of G. margarita BEG 34 (6) when the following templates were used: G. margarita WV 205A (lane 1), G. margarita Brazil isolate (lane 2), S. persica HC/F E09 (lane 3), G. rosea BEG 9 (lane 4), S. castanea BEG 1 (lane 5), G. decipiens (lane 6), G. gigantea (lane 7), and no DNA (lane 8). Lane M contained a 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco BRL).

Endobacteria are not a sporadic phenomenon in the Gigasporaceae.

Morphological and molecular analyses demonstrated the presence of endobacteria in the cytoplasm of five of six different fungal species in the genera Gigaspora and Scutellospora. Isolates belonging to the same species were found to be similar in terms of the presence or absence of endobacteria and bacterial number, shape, and 16S rDNA sequences, even when they were derived from distant geographic areas. This was well documented for G. rosea and G. margarita.

The Gigasporaceae comprise two genera and 33 species (http://invam.caf.wvu.edu/Myc_Info/Taxonomy), and our analysis is not representative of the whole family mainly due to difficulties in obtaining spore samples for all species. However, four of the five species in the genus Gigaspora were studied in this investigation. In this genus, different species could have quite distinct features. In Gigaspora, two extreme cases are G. margarita and G. rosea; the former harbors an estimated 250,000 bacteria per spore (6), and the latter harbors none, as also reported by Hosny et al. (14) on the basis of PCR results. G. gigantea also contains endosymbiotic bacteria, but they are different from those found in other Gigaspora species both because of their round shape and because total spore DNA could not be amplified by the specific primers that amplified bacterial DNA from G. margarita and Gigaspora decipiens. These endobacteria are currently under investigation.

In Scutellospora, both species investigated contained rod-shaped endobacteria whose 16S rDNA was amplified with the BLO primers, although some variability in bacterial number was found in the two isolates of S. persica. Successful amplification of bacterial DNA from Scutellospora castanea BEG 1 and Scutellospora gregaria by the BLO primers was reported by Hosny et al. (14). The genus Scutellospora comprises almost 30 species, and analysis of a wider range of species is needed to elucidate if endobacteria are common in this genus.

Endobacterial phylogeny.

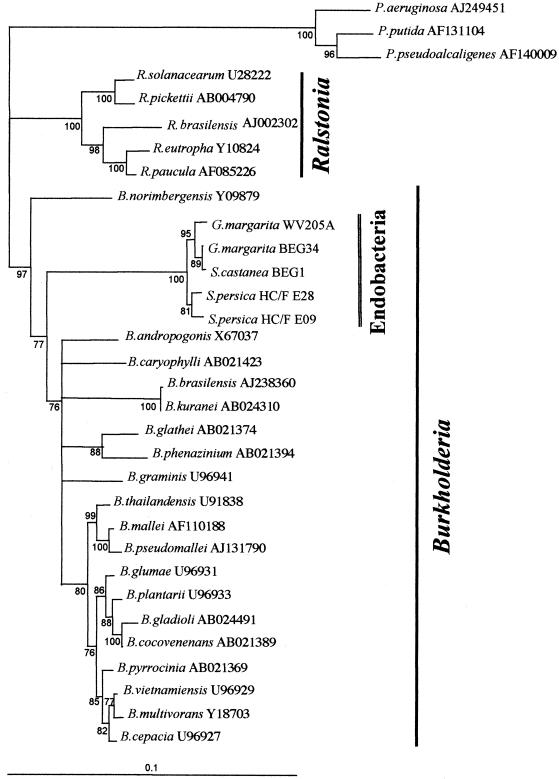

Total spore DNA was amplified by using universal bacterial primers 27f and 1495r to obtain most of the 16S ribosomal gene. Amplified fragments about 1,500 bp long were obtained from S. persica HC/F E28 and HC/F E09, S. castanea BEG 1, and G. margarita WV 205A. They were cloned into the pGEM-T vector, and three different clones were sequenced for each isolate as described by Lanfranco et al. (17). The 16S rDNA sequences obtained in this study were aligned with those of the G. margarita BEG 34 endobacteria (6) and of closely related bacterial species obtained through a BLAST search in which the endobacterial sequences were used as queries.

All new sequences clustered together with the G. margarita BEG 34 endosymbiont (Fig. 4) in a single, well-supported branch. This endosymbiont was originally classified as a sister group of Burkholderia cepacia (6) in the beta subdivision of the division Proteobacteria (32). A more recent comparison of the 16S rDNA sequences of Burkholderia strains has revealed a clear separation into two branches, and a number of species previously assigned to this genus have been reassigned to the genus Ralstonia (16, 33). This taxonomic rearrangement, as well as identification of novel species of Burkholderia, has again raised basic questions concerning the taxonomic position of the endosymbiotic bacteria of the Gigasporaceae. The neighbor-joining tree in Fig. 4 suggests that the closest relatives of the endobacteria that have been sequenced are members of the genus Burkholderia, as they form a well-supported branch nested in this genus that is well separated from Ralstonia.

FIG. 4.

Neighbor-joining tree obtained from alignment of the 16S rDNA of the endosymbionts of G. margarita, S. castanea, and S. persica isolates with the closest bacterial sequences retrieved by a BLAST search. Sequences were aligned by using the ClustalX program (31), and the alignment was edited with GeneDoc (22). Neighbor-joining analysis was performed with the ClustalX program using Kimura's distance method. The branch comprising species in the genus Pseudomonas was used as an outgroup. Branches are shown only when the percentage of bootstrap support (1,000 trials) exceeded 70%.

Some hypotheses concerning the establishment of symbiosis between AM fungi and their endobacteria.

Intracellular symbioses raise fascinating questions about the acquisition of the endosymbionts, the transmission of the endosymbionts, and the evolution of reciprocal adaptations (10). The presence of endobacteria or BLOs in all glomalean families suggests that the ability of AM fungi to establish this type of association appeared very early in evolution.

Margulis and Chapman (19) have discussed the importance of endosymbiosis as an evolutionary mechanism and distinguished between permanent and cyclical endosymbioses; the former remains stable over time, and the latter involves regular reassociation events. The type of relationship between AM fungi and their endobacteria remains an open question that will be more properly addressed by analysis of a wider range of species. However, the observations made so far with members of the Gigasporaceae suggest at least two possible and opposite scenarios.

Related endobacteria were found by sequencing DNA in different isolates belonging to the Gigasporaceae from very distant geographic areas. This situation may be the result of rare bacterial acquisition events during evolution, followed by strictly vertical transmission of endosymbionts (permanent symbiosis) through generations. The asexual reproduction typical of AM fungi and the coenocytic nature of the mycelium in the zygomycetes (26) are factors that could facilitate this type of transmission.

However, an alternative scenario can also be envisaged. The complex situation observed in the Gigasporaceae could be derived from more temporary but frequent associations of AM fungi with free-living soil bacteria (cyclical symbiosis), with AM fungal species selecting their bacterial symbionts from the environment. Different free-living Burkholderia species have been identified in the rhizosphere and the hyphosphere of AM fungi (4) and may represent a reservoir of potential endosymbionts for the AM species harboring this group of bacteria. A physical constraint that would make endocytosis, and thus acquisition of bacteria from the environment, a very rare event in fungi is the cell wall that surrounds the fungal hyphae. However, zygomycetes may represent a special case among fungi since Geosiphon pyriforme, a zygomycete which is ancestral to the Glomales (11), is the only known fungus able to establish cyclical endosymbiotic associations with cyanobacteria (20).

In conclusion, we demonstrated by sequencing that at least three different fungal species in the two genera of the Gigasporaceae harbor in their cytoplasm endosymbiotic bacteria related to each other and closely related to the genus Burkholderia. The occurrence of related endobacteria in different geographic isolates of the same AM fungal species may arise as a result of either permanent or cyclical endosymbiosis based on specific recognition mechanisms. The pattern of distribution of endobacteria in different AM species, together with the recent finding that isolates of G. margarita and G. rosea influence plant growth and plant mineral content to different extents (24), raises intriguing questions about the biological role of these endosymbionts.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the GeneBank database under accession numbers AJ251634 (S. persica HC/F E28), AJ251635 (S. persica HC/F E09), AJ251636 (S. castanea BEG 1), and AJ251633 (G. margarita WV 205A).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to G. Bécard, J. Dodd, D. Douds, C. Leyval, and J. Morton for AM fungal spore samples and to J. Morton for morphological identification of some isolates. We thank M. Girlanda for critical reading of the manuscript and C. Bandi for initial help with sequence alignment.

This research was funded by the EU IMPACT2 project (BIO-CT96-0027) and by the Italian National Council of Research (CNR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht C, Geurts R, Bisseling T. Legume nodulation and mycorrhizae formation; two extremes in host specificity meet. EMBO J. 1999;18:281–288. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Springer N, Ludwig W, Goertz H D, Schleifer K H. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature. 1991;351:161–164. doi: 10.1038/351161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade G, Mihara K L, Linderman R G, Bethlenfalvay G J. Bacteria from rhizosphere and hyphosphere soils of different arbuscular-mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil. 1997;192:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bago B, Bentivenga S P, Brenac V, Dodd J C, Piché Y, Simon L. Molecular analysis of Gigaspora (Glomales, Gigasporaceae) New Phytol. 1998;139:581–588. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianciotto V, Bandi C, Minerdi D, Sironi M, Tichy H V, Bonfante P. An obligately endosymbiotic mycorrhizal fungus itself harbors obligately intracellular bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3005–3010. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.3005-3010.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonfante P, Balestrini R, Mendgen K. Storage and secretion processes in the spore of Gigaspora margarita Becker & Hall as revealed by high-pressure freezing and freeze substitution. New Phytol. 1994;128:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukatsu T, Nikoh N. Two intracellular symbiotic bacteria from the mulberry psyllid Anemoneura mori (Insecta, Homoptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3599–3606. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3599-3606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukatsu T, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi Y. Specific detection of intracellular symbiotic bacteria of aphids by oligonucleotide-probed in situ hybridization. Appl Entomol Zool. 1998;33:461–472. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futuyma D J, Slatkin M. Coevolution. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer; 1983. p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gherig H, Schußler A, Kluge M. Geosiphon pyriforme, a fungus forming endocytobiosis with Nostoc (Cyanobacteria) is an ancestral member of the Glomales—evidence by SSU rRNA analysis. J Mol Evol. 1996;43:71–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02352301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison M J. Molecular and cellular aspects of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:361–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hijri M, Hosny M, Van Tuinen D, Dulieu H. Intraspecific ITS polymorphism in Scutellospora castanea (Glomales, Zygomycota) is structured within multinucleate spores. Fun Genet Biol. 1999;26:141–151. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosny M, van Tuinen D, Jacquin F, Fuller P, Zhao B, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Franken P. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria: how to construct prokaryotic DNA-free genomic libraries from the Glomales. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:425–430. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosny M, Hijri M, Passerieux E, Dulieu H. rDNA units are highly polymorphic in Scutellospora castanea (Glomales, Zygomycetes) Gene. 1999;226:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kersters K, Ludwig W, Vancanneyt M, De Vos P, Gillis M, Schleifer K H. Recent changes in the classification of the pseudomonads: an overview. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:465–477. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanfranco L, Delpero M, Bonfante P. Intrasporal variability of ribosomal sequences in the endomycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:37–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald R M, Chandler M R. Bacterium-like organelles in the vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus caledonius. New Phytol. 1981;89:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margulis L, Chapman M J. Endosymbioses: cyclical and permanent in evolution. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:342–345. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mollenhauer D, Mollenhauer R, Kluge M. Studies on initiation and development of the partner association in Geosiphon pyriforme (Kutz.) v. Wettstein, a unique endocytobiotic system of a fungus (Glomales) and the cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme (Kutz.) Hariot. Protoplasma. 1996;193:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosse B. Honey-coloured sessile Endogone spores. II. Changes in fine structure during spore development. Arch Mikrobiol. 1970;74:146–159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholas K B, Nicholas H B J R, Deerfield D W. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBNEW News. 1997;4:14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perotto S, Bonfante P. Bacterial associations with mycorrhizal fungi: close and distant friends in the rhizosphere. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:496–501. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz-Lozano, J. M., and P. Bonfante. Intracellular Burkholderia strain has no negative effect on the symbiotic efficiency of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita. Plant Growth Regulat., in press.

- 25.Ruiz-Lozano J M, Bonfante P. Identification of a putative P-transporter operon in the genome of a Burkholderia strain living inside the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4106–4109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.4106-4109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders I R. No sex please, we're fungi. Nature. 1999;399:737–739. doi: 10.1038/21544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scannerini S, Bonfante P. Bacteria and bacteria-like objects in endomycorrhizal fungi. In: Margulis L, Fester R, editors. Symbiosis as a source of evolutionary innovation: speciation and morphogenesis. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1991. pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon L, Bousquet J, Lévesque R C, Lalonde M. Origin and diversification of endomycorrhizal fungi and coincidence with vascular land plants. Nature. 1993;363:67–68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith S E, Read D J. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor T N, Remy W, Hass H, Kerp J. Fossil arbuscular mycorrhizae from the early Devonian. Mycologia. 1995;87:560–573. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The ClustalX Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4567–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Yano I, Hotta H, Nishibuchi Y. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov.: proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff, 1973) comb. nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis, 1969) comb. nov. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]