Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has triggered a massive research, but still urgent detection and treatment of this virus seems a public concern. The spread of viruses in aqueous environments underlined efficient virus treatment processes as a hot challenge. This review critically and comprehensively enables identifying and classifying advanced biochemical, membrane-based and disinfection processes for effective treatment of virus-contaminated water and wastewater. Understanding the functions of individual and combined/multi-stage processes in terms of manufacturing and economical parameters makes this contribution a different story from available review papers. Moreover, this review discusses challenges of combining biochemical, membrane and disinfection processes for synergistic treatment of viruses in order to reduce the dissemination of waterborne diseases. Certainly, the combination technologies are proactive in minimizing and restraining the outbreaks of the virus. It emphasizes the importance of health authorities to confront the outbreaks of unknown viruses in the future.

Keywords: Virus removal, Wastewater treatment, Membrane, Disinfection

Graphical abstract

Author contributions

All authors have participate to the preparation, writing, and editing of this review manuscript. More specifically, Hussein E. Al-Hazmi wrote first draft, designed water treatment illustration and designed master tables; Hanieh Shokrani and Amirhossein Shokrani provided data from the literature on virual removal strategies and wrote some complementary parts; Karam Jabbour and Otman Abida checked the methodology and framework of the research; Seyed Soroush Mousavi Khadem designed illustrations, provided information for original work from water purification viewpoint, and assisted discussion in the revised manuscript; Shirish H. Sonawane wrote the part on the effect of sonication on the removal of pollutants; Adrián Bonilla-Petriciolet edited the original manuscript and completed some parts; Mohammad Reza Saeb visualized the research objectives and systematically supervised and completed the revision process; Sajjad Habibzadeh and Michael Badawi have conceptualized and supervised this project in addition to their corrections at various stages of the manuscript.

1. Introduction

Wastewater reuse brings about numerous benefits including eutrophication reduction, embodied energy production and carbon footprint reduction (Cornejo et al., 2013; Verbyla and Mihelcic, 2015). To do so, wastewater treatment has been increasingly considered and used as one of the most common strategies for water management, particularly in small cities, because of being cost-effective, its facile construction and operation control (Ahmadi et al., 2021; Aghamirza Moghim Aliabadi et al., 2022a). There is a wide spectrum of pollutants in water resources, likewise a variety of materials and strategies can be used for water reuse (Taghizadeh et al., 2020). In general, diverse contaminants such as organic pollutants, nutrients, microorganisms, ions of heavy metals and organic micropollutants can be found in the greywater, but treatment of greywater makes it possible to remove pathogens and suspended solids in order to increase the quality of water for reuse (Shaikh and Ahammed, 2020). Although environmental parameters of such phenomena are main sources of concerns, they should additionally be seen from the energy consumption angle. In this regard, economic investigations based on circular economy approach and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) are recommended for the individual and combination wastewater treatment methodologies (Hidrovo, 2018; Yoonus and Al-Ghamdi, 2020). The economy of wastewater treatment takes a more serious priority when water quality is of vital importance for reuse like irrigation (Verbyla and Mihelcic, 2015). Over the past half a century, a particular attention has been paid to remove viruses from wastewater to make it safer for irrigation or drinking purposes. For example, since the 1970s the California State Department of Health in the USA has started to establish virus removal by defining the quality and treatment standards for the water discharged into the ponds and rivers as the main harmful sources of human health (Dryden et al., 1979). Commonly, viruses are present in low concentration in the waterborne, as a consequence of the analysis methods used for viruses' detection being complex — a limit on virus concentration not being specified in the national and international regulations during the last centuries (Barczak et al., 2021; Farshchi et al., 2021a; Kordasht et al., 2021). Thus, attention has been gradually directed to a shift from using simple to combination treatment methods. According to Gerba's research (Gerba, 1981), the viruses removal efficiency was obtained ≤50% by the primary treatment, while ≈99% of viruses removal efficiency was achieved by the secondary treatment. Therefore, it could be expected to treat smaller or less detectable viruses by secondary wastewater treatment such as enteroviruses (Saba et al., 2021). The same research group also recommended using tertiary treatment with other processes such as disinfection for the complementary removal of a wider range of viruses (Gerba, 1981).

In parallel with progress in stage-wise virus treatment methodologies, membrane systems have played a critical role in the removal of viral microorganisms. Since the beginning of the current century, there has been a growing interest in the quality water treatment for viral microorganism removal in order to achieve complete protection for the environment and human health from virus lethality (Naranjo et al., 1993; Okoh et al., 2010). Besides, ultrafiltration was found to be the most effective among physical treatments, especially for wastewater reuse. On the other hand, ultrafiltration was far beyond practical in comparison with the microfiltration when highly efficient treatment of water quality was the objective (Chaudhry et al., 2015a; Qiu et al., 2015). In contrast, some reported (Gander et al., 2000) a significant bacteria and virus abundance as a consequence of accumulated microfiltration (MF) and ultrafiltration (UF) membranes. The build-up of viral microorganisms in MF membranes is enhanced by the accumulation of a dynamic layer as well as high turbidity. Consequently, the disinfection process is very important not merely for the European Commission (EC) discharge consents but also for the practical wastewater recycling (Gander et al., 2000). To obtain a long-lasting and practical viral removal, an electrically-enhanced membrane bioreactor (EMBR) has been designed. It is demonstrated that exerting 2.0 V brings about almost 100% removal, against about 20% without using an electrical field (Bosch et al., 2006). Thus, it has been indicated that (Goddard and Butler, 2015) the wastewater treatment should be combined with the primary (physical) process, secondary (biological) process, tertiary (physicochemical) process, and possible by the aid of advanced treatment processes for optimum viral pathogenic removal. On the other hand, some suggested (Kitajima et al., 2014) that the virus abundance and removal efficiency could be utilized as potential indicators of wastewater treatment performance for the water reuse and recycling.

Surface water and urban wastewater are the main sources, both of which mainly contain microbial pathogens that must be diminished to a standard degree to avoid their harm to human health. The results of virus recognition and treatment show that it would be a sort of arduous challenge to get rid of them successfully by a one-step treatment (Sano et al., 2016; Carducci et al., 2020; Ghernaout and Elboughdiri, 2020; Sellaoui et al., 2021). Moreover, due to their low concentration within the aquatic environments, it is necessary to be aware of methods that concentrate them with the aim of adjusting the parameters/conditions for biological investigations (Haramoto et al., 2018). In the same context, the property analysis of water and wastewater can be taken as a tool for early warning, and to alert communities to new infections with viruses (e.g., COVID-19 and its variants). Viral removal efficacy can be measured stage-wise during treatment stages due to the fact that wastewater flow may be reused for irrigation or may join the surface water. It may also play a vital role in public contamination and disease spreading. For example, among different methodologies, algal-based treatment appears capable of eliminating viruses and also reduction, even up to 90%, of toxic chemicals or industrial heavy metals in lab-scale (Umamaheswari and Shanthakumar, 2016; Park et al., 2019). Algae have been examined in wastewater treatment, in conjunction with active microrobots and also for the management of SARS-CoV-2 contaminated water. Zhang et al. (2021) investigated SARS-CoV-2 removal by algae-based microrobot in wastewater. Results revealed that viral spike protein was removed by 95% along with Pseudovirus was removed by 89% — highlighting algae useful for wastewater treatment. Algae-based wastewater treatment mechanisms for virus removal include in the precipitation after virus particles attached to algal biomass, algal nucleic acids and proteins denatured at elevated temperatures. Lesimple et al. (2020) treated activated sludge in a similar manner with Log Removal Value (LRV) of 1–3 pertinent to the type of virus. However, attention was paid to increase the efficiency of treatment by decreasing the number of species to avoid chlorination as a complementary process. Nonetheless, algal treatment can be highly affected by temperature and daylight ratio on a lab-scale (Umamaheswari and Shanthakumar, 2016). Arora and Kazmi (2015) demonstrated that any deviation from the optimal temperature range causes efficacy reduction. Reports demonstrate that the efficient elimination of micropollutants and pathogens using ozonation has led to the reduction in the risks of estrogenic as well as mutagenicity effects on the living organisms (Iakovides et al., 2019). Combination treatment using ozonation in parallel with granular activated carbon (GAC) could successfully decrease the concentration of micropollutants and viruses; thereby minimizing their potential risks on the exposed population and living organisms. Thus, advanced treatment using both mentioned approaches is suggested (Ternes et al., 2017).

So far, some crucial aspects of virus removal processes have been surveyed, reviewed and discussed by a number of research groups (Gerba et al., 2018; Bhatt et al., 2020; Goswami and Pugazhenthi, 2020; Chen et al., 2021b; Kong et al., 2021). Bhatt et al. (2020) focused on the partial wastewater treatment approaches for the removal of viruses, i.e. physical, chemical and biological treatment methods have been overviewed in their review. On the other hand, Chen et al. (2021b) covered in their review virus removal from water based on the membrane technologies and disinfection methods. Despite the aforementioned useful attempts, a kind of classified and consolidated review was deemed to be urgent to cover three main facets. First, abrupt expansion of environmental engineering science necessitates an elaborated review regarding technical membrane filtration and disinfection processes to reach the state-of-the-art in optimal efficient removal of virus-containing water and wastewater. Second, there is lack of correspondence between virus contamination and practical techniques implemented among published reports to postulate possible reasons behind combined biochemical, membrane and disinfection technologies (Chen et al., 2021a; Wu et al., 2021). Such a proactive approach enables one to prevent from virus spread via contamination and transmission via aqueous media, means that health authorities are pertinent to prevention of virus outbreak resulting from detailed data analysis. Third, there is an urgent need for address this gap that classification and discussion of the challenges of combining membrane and disinfection processes for treating viruses in water. Previous reviews were grounded on classification based on the outcomes, while present arduous challenges are mainly arising from processing parameters. Although wastewater treatment systems can function individually, combination systems can increase the efficiency of the process on one hand and make them economically reasonable on the other hand. The ability to understanding the functions of these systems in terms of the efficiently of each process individually or as a multi-stage process is of crucial importance. Such a comparative overview is the main objective of this review. Occasionally, combining systems together or using two separate units, one enables the initial separation with common viruses and the second makes possible to remove smaller viruses or a specified type of virus (due to the higher separation capability of process specific viruses), can help both the manufacture and the economy of this process (Su et al., 2016). Details on methodology of this review are given in section s1 in the supplementary information (SI).

2. Classification and characteristics of viruses

Based on the type of genome, viruses are divided into four main classes, namely single- and double-stranded Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and single and double-stranded Ribonucleic acid (RNA) (Bosch, 1998; Flint et al., 2020). Typically, waterborne viruses are including Adenoviruses, Enteroviruses, Coxsackieviruses, Echoviruses, Hepatitis A viruses, and Caliciviruses (Wong et al., 2012). Moreover, some indicated (Wong et al., 2012) that several kinds of viruses in wastewater are the consequence of virus transmission from human being, such as Coronavirus virus (Meyerowitz et al., 2021). Coronavirus, nowadays the virus type responsible for current pandemic and its worldwide impacts, has been the cause of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), as well as the new Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Carducci et al., 2020; Sellaoui et al., 2021). This kind of virus can be referred to as zoonosis, reverse zoonosis and even animal to animal (Mohapatra et al., 2021). Salivary, aerosols, stool, urine and inanimate objects can be addressed as the most common viral transmission routes (Kampf et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Mohapatra et al., 2021). Fig. 1 shows a schematic of human exposure to virus contamination from different sources by accidental ingestion and inhalation throughout environmental pollution.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of human exposure to virus contamination by accidental ingestion and inhalation throughout environmental pollution, partially adapted from (Ogilvie et al., 2013; Xagoraraki et al., 2014; Fanourakis et al., 2020; Van Gaelen et al., 2020) (Designed by the authors of the present work).

The viruses have different characteristics depending on the various conditions. Numerous reports have indicated that the temperature, light, pH, metal oxides, soil organics, colloidal organic, chemical solution, ionic strength, air-water interface existence of microbiological flora, salinity and ultraviolet (UV) exposure are the most critical factors that affect viral behavior (Bosch et al., 2006; Mohapatra et al., 2021). For instance, the exposure to sunlight can inactivate the poliovirus up to 99% within 21 days, nonetheless, while 52 days is needed in the absence of the sunlight (Bosch et al., 2006). It is worth mentioning that the virus-particle interaction, virus-microorganism interaction, as well as virus-macroinvertebrates are the subjects that are not comprehensively studied. A brief view of virus classification and characteristics is given in section s2 (see also Table S2) in the Supplementary Information (SI).

3. Virus removal by biochemical process

The biochemical process is aimed at treating the organic matter, nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphors, Sulfur, etc.), soluble contaminants (metals, organic compounds, etc.), suspended solids from wastewater and also can work as a virus removal methodology (Al-Hazmi et al., 2019, 2020, 2021). It can be classified as conventional activity sludge (nitrification and denitrification) and anammox based-systems such as nitridation based-anammox and denitridation based-anammox (Feng et al., 2017). Numerous studies report that the biochemical process has succeeded to remove virials pathogens from wastewater. Prado et al. (2019) calculated the efficiency of pathogenic removal in wastewater treatment processes, which is defined as the number of viruses removed from any process and represented by the following Equation:

| (1) |

where and indicate the viable virus number before and after the wastewater process.

According to another research (Osuolale and Okoh, 2017), LRV of Rotaviruses achieved 0.66 in activated sludge system with a 40,000 m3/day flow rate at Eastern Cape, South Africa. Moreover, Polyomaviruses were successfully removed (LRVs = 1.93) by activated sludge as the secondary treatment process (600,000 m3/day) at Cairo, Egypt (Hamza and Hamza, 2018). O'Brien et al. (O'Brien et al., 2017) observed that LRV of Hepatitis A virus ranged 1.93–8.70 × 103 genes copies/L via secondary treatment in full-scale wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) at Kampala, Uganda conventional activated sludge. The biochemical process as secondary treatment removed ≈2.69 × 103 genes copies/L of Astroviruses in WWTP, France (Prevost et al., 2015). Elmahdy et al. (2019) observed that the Adenoviruses removal ranged from 1.22 × 104 to 3.7 × 106 genes copies/L by sewage sludge treatment in wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) with 330,000 m3/day capacity, Egypt. LRVs for Human Adenovirus, JC Polyomavirus, Norovirus I and Norovirus II were 18, 0.64, 0.45 and 0.72, respectively, from wastewater in public health sectors in Lagoon wastewater system by aerated process, at South Catalonia, Spain (Fernandez-Cassi et al., 2016). Delanka-Pedige et al. (2020) successfully removed viruses including Somatic Coliphages (LRVs = 3.13), F-specific coliphages (LRVs = 1.23), Enterovirus (LRVs = 1.05) and Norovirus GI (LRVs = 1.49) in full-scale conventional wastewater treatment plant at Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA using Galdieriasulphuraria (algae). Thus, biological processes can partially perform the virus removal, but require other complementary processes to achieve high efficiency in WWTP. Table 1 shows the various classifications of water and wastewater viruses as well as virus removal efficiency in WWTP.

Table 1.

Classification of water and wastewater viruses as well as virus abundance and removal efficiency in wastewater treatment plant (WWTP).

| Sample/Country | Treatment technology | Virus name | Gene | Virus abundance (i) genes copies/L (ii) Gene equivalents/L |

Log Removal Values |

Quantitative analysis method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influent | Effluent | LRVs | ||||||

| WWTP/Grid, Italy | Separation, primary sedimentation, secondary biological treatment and disinfection | Enteroviruses | s-s RNA | 3.3 × 107 (i) | 7.6 × 106 (i) | 0.63 | RT-PCR, Real-time qPCR | (La Rosa et al., 2010) |

| WWTP/Southern Arizona, USA |

Plant A: conventional activated sludge process Plant B: biological trickling filter process |

Pepper mild mottle virus | s-s RNA | 3.7–4.4 × 106/3.2–9.4 × 106 (i) |

4.6–6.3 × 105 (i) | 0.76–0.99/1.8 ±0.2 |

TaqMan-based qPCR | (Kitajima et al., 2014) |

| WWTP/Arizona, USA | Activated sludge and trickling filter |

Coxsackieviruses | – | 3.24 × 105 (i) | 1.54 × 103 (i) | 2.32 | RT-PCR | (Kitajima et al., 2015) |

| WWTP/France | Primary decantation and biological secondary treatment | Astroviruses | s-s RNA | – | 2.69 × 103 (i) | – | RT-qPCR | (Prevost et al., 2015) |

| WWTP/Kampala, Uganda | Conventional activated sludge method, in summer 2016 |

Hepatitis A virus | s-s RNA | 2.01 × 103–8.39 × 103 (i) |

1.93 × 103–8.70 × 103 (i) |

– | qPCR and quantitative RT-PCR |

(O'Brien et al., 2017) |

| Eastern Cape, South Africa | Activated sludge system with 40,000 m3/day flow rate | Rotaviruses | d-s RNA | 1.2 × 105 (i) | 2.6 × 104 (i) | 0.66 | Quantitative TaqMan real-time PCR |

(Osuolale and Okoh, 2017) |

| WWTP/North Wales, UK | With filter beds for secondary treatment and serves ca. 4000 inhabitants | Norovirus Genotypes GI/GII |

s-s RNA | 8.8 × 104 (i) | 3 × 104 (i) | 0.47 | RT-qPCR | (Farkas et al., 2018) |

| WWTP/Greater Cairo, Egypt | Activated sludge as secondary treatment process with 600,000 m3/day | Polyomaviruses | d-s DNA | 3.9 × 105 (i) | 4.51 × 103 (i) | 1.93 | Real time PCR | (Hamza and Hamza, 2018) |

| Sample/Country | Treatment technology | Virus name | Gene | Virus abundance (i) genes copies/L (ii) Gene equivalents/L |

Log Removal Values |

Quantitative analysis method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influent | Effluent | LRVs | ||||||

| WWTP Egypt |

330,000 m3/day capacity | Adenoviruses | d-s DNA | 4.3 × 105–8.7 × 106 (i) | 1.22 × 104–3.7 × 106 (i) |

– | Real time PCR | Elmahdy et al. (2019) |

| WWTP Japan |

Conventional activated sludge process | SARS-CoV-2 | s-s RNA | – | 2.4 × 103 (i) | – | RT-qPCR | Haramoto et al. (2018) |

| WWTP/P. Alegre, Brazil | An anaerobic stage by the UASB reactor and an aerobic stage through the Unitank® System. | SARS-CoV-2 | s-s RNA | 4.14 × 101–5.23 × 103 (i) | – | – | RT-qPCR | Zaneti et al. (2021) |

| WWTP/Murica, Spain | Untreated wastewater samples | SARS-CoV-2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 log10 (i) | – | – | RT-qPCR | Zaneti et al. (2021) | |

| Raw WWTP/Paris/France | Several major wastewater treatment plants | SARS-CoV-2 | s-s RNA | 3–50 × 103 (ii) | – | – | RT-qPCR | Wurtzer et al. (2020) |

| Raw wastewaters/Germany | Untreated sewage and treated water by ozonation samples | SARS-CoV-2 | Solid phase 25 (i) Aqueous phase 1.8 (i) |

Solid phase 13 (ii) Aqueous phase 8.8 (ii) |

– | RT-qPCR | Westhaus et al. (2021) | |

Abbreviations: qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction, RT-(q)PCR: Reverse Transcriptase-(Quantitative) polymerase chain reaction, ICC-qPCR: Integrated cell culture with quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

4. Virus removal by membrane technology

Over the past 20 years, membrane technology has been one of the emerging technologies of wastewater treatment, almost always in the center of attention of environmentalists (Liu et al., 2022a, 2022b). Materials used in this technology can be mainly grouped in ceramic and polymeric membranes, each of which has its features such as durability, chemical, mechanical and thermal stability, resistance against bacteria, back flushing ability, and cleaning and sterilization easiness (Huang et al., 2021; Nosrati et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). However, there are still challenges associated with membrane technology, especially in conjunction with the cost of optimization and fabrication, selectivity and antifouling properties. Moreover, the improving of the density of packing comes with such concerns. For virus removal, individual or combined systems are used depending on efficiency and cost requirements. Fig. 2 A displays the mechanism of the permeability of water and contaminant removal section in a brief view, while Fig. 2B shows classification of processes in terms of the pore size and contaminant size and type.

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic of transportation of water and removal of pollutants in porous membranes in a pressure-driven filtration process; and (B) Comparison of different membrane technologies (Designed by the authors of the present work).

4.1. Membrane bioreactor

The state-of-the-art membrane technology has created a boom in industrial development and a greater demand for clean water by membranes was felt, which underscored the significance of nonconventional water reservoirs such as wastewater or seawater conversion to fresh and safe water (El Kharraz et al., 2012; Tzanakakis et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021). Membrane bioreactors (MBRs) increase the autonomous sludge residence time (SRT), hydraulic residence time (HRT) as well as the effluent quality (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2018; Bayo et al., 2020). The aforementioned SRT and HRT retention times in an anaerobic digester are identical to solid retention time (SRT) and hydraulic retention time (HRT). The ‘SRT’ is defined as the average time up to which bacteria (solids) are in the anaerobic digester. The ‘HRT’ is similarly defined as the time the wastewater or sludge remains in the anaerobic digester. Another important point in this method is its sustainability compared to other treatment processes (e.g., adsorption, chemical precipitation, ion exchange). Membrane-based processes are environmentally friendly as they rely on the principle of physical separation (Ali et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is possible to use different types of membranes (e.g., polymeric, ceramic) in this method in order to increase its versatility to treat fluids with a broad spectrum of characteristics and properties (Arumugham et al., 2021; Vatanpour et al., 2022b). This is because of the fact that each membrane has its own unique advantages and disadvantages, as well as the ability to provide different results and functions (Zirehpour and Rahimpour, 2016). Moreover, membrane foulants that increase the operational costs and reduce the membrane performance can be categorized as organic, inorganic as well as bio-foulants (Kang and Cao, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016; Upadhyaya et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018).

Different attempts have been conducted to find a satisfying solution for membrane performance acceleration and reducing the fouling percentage (Lee et al., 2018; Esfahani et al., 2019). For example, polyvinylidene fluoride/Ag–SiO2 membrane was designed using noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) methodology, which brought about a drastic anti-biofouling capability (Ahsani et al., 2020). Sathya et al. (2019) explained that the integration of MBR with photocatalysis can be used for virus removal. Additionally, feed composition, activated sludge characteristics, SRT, operation situation, sewage and membrane features, as well as food-to-microorganism (F/M) ratio, can leave a huge trace on treatment quality (Krzeminski et al., 2017; Vergine et al., 2020, 2021). The key factor that accredits the MBR systems from other biological treatment procedures is that these systems have been considered as a robust strategy against pathogens such as Noroviruses, Sapoviruses, Adenovirus, Norovirus GII and Rotaviruses (Chaudhry et al., 2015b; Harb and Hong, 2017; Miura et al., 2018). Based on the pores of membranes, the larger are the pores, the easier viruses pass them through. When the particles are larger than the membrane's pores they will be rejected. Hence, it is critical to design the pores either equal to or smaller than the aimed virus to achieve its removal more efficiently (Gentile et al., 2018; Cecconet et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021). Generally, there are three key stages for virus elimination in these systems: (i) virus adsorption to biofilm, (ii) virus inactivation within liquor phase, and (iii) rejecting back the washed membrane (O'Brien and Xagoraraki, 2020b; Zhu et al., 2021). Virus inactivation takes place when viruses adsorbed by the biofilm membranes are inactivated by membrane as a consequence of degradation or rejection in the aqueous medium. Fig. S3 in SI shows the scheme of MBR system for virus treatment. Table S3 in SI also summarizes the virus removal efficiency from various water and wastewater sources by the MBR system.

4.2. Electrically-enhanced membrane bioreactor (EMBR)

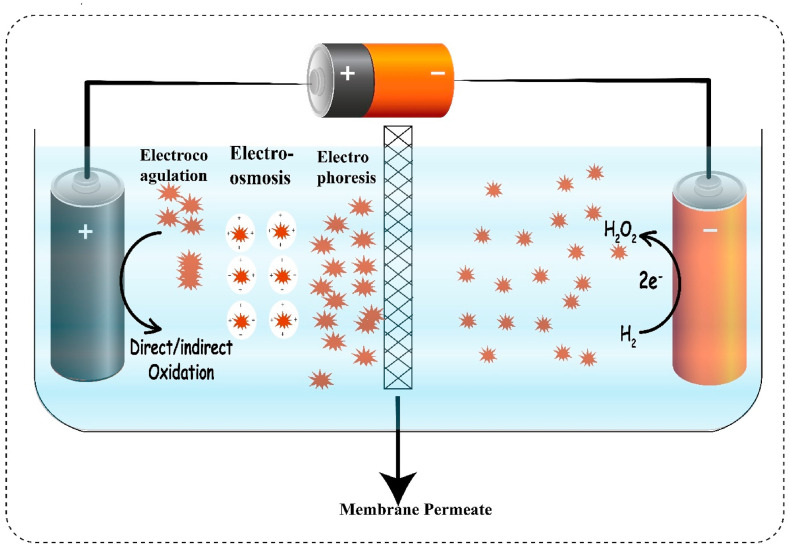

A great deal of effort has been made to reduce the fouling rate in the membrane-based processes, a major challenge for the widespread use of membrane bioreactors (MBRs) that also affects virus removal (Ho et al., 2017). Recently, the use of electricity in electrically-enhanced MBR (EMBR) to suppress membrane fouling has received increasing attention from the research community (Helmi and Gallucci, 2020). The flow of electricity stimulated several electrokinetic processes, including electrophoresis/electrochemical processes and electrocoagulation, which are the main pollution suppression mechanisms used in EMBR. In addition, the use of an active anode is similar to electrocoagulation where cationic coagulants are formed in EMBRs, which can neutralize the charge of fouling and promote floc formation (Amini et al., 2020).

Compared to the traditional MBRs, EMBRs consist of an additional pair of electrodes (anode and cathode) that supplies electricity to the system. In the case of a standalone EMBR, internal electricity is generated when electrons flow from the anode to the cathode through an external resistor. In general, both external power supplies and standalone EMBRs follow the same pollution fouling mechanisms. It is recommended that an EMBR can be located both inside and outside the electric field (Sarkar et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014; Giwa et al., 2019). The advantages and applications of the electroconductive membrane for antifouling have been critically reviewed (Ahmed et al., 2016). On the other hand, a filter membrane can be an external component of a pair of electrodes when the purpose of this configuration is to have multiple zones for different treatment processes (Zhang et al., 2015; Ahmed et al., 2016). Fig. S4 in SI illustrates a diagram of the membrane fouling control mechanism of EMBR. Arrows in boxes indicate increasing (up) or decreasing (down) values of various parameters.

Fig. 3 proposes a simple mechanism for the wastewater treatment by EMBR. Typically, an EMBR with a protective anode has been observed to achieve an increased phosphorus content (up to 40%) and removal of microcontaminants (5–60%) and viruses. In fact, direct anodization, indirect oxidation by the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and electrocoagulation can complement biological processes. Depending on the current density and electrode material (sacrificial or non-sacrificial), the mechanisms of anodization, electrocoagulation, electrophoresis, and/or electro-osmosis serve to suppress the tendency to foul the membrane (Ensano et al., 2016). Therefore, this system contributes to minimize the impact of fouling on process performance including virus removal.

Fig. 3.

Scheme of electrically-enhanced membrane reactor technologies for wastewater treatment (Designed by the authors of the present work).

4.3. Membrane filtration technology

Membrane filtration technology can be assorted into different main classes including microfiltration (MF), summarized in Table S4, ultrafiltration (UF) summarized in Table S5 in SI, nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO). A team of scientists in Japan demonstrated that MF can be a far more effective procedure for Peppermildmottlevirus (PMMoV) treatment in comparison with the slow sand filtration (Sinclair et al., 2018; Canh et al., 2019; Im et al., 2019; Campinas et al., 2021). They reported that the PMMoV removal using MF was from 0.0 to >0.9 log10, which was 2.8 log10 for slow sand filtration (anyways, it was strongly dependent on temperature). The pore size ranging from 1 to 100 nm in this type of membrane can endorse different removal mechanisms such as electrostatic repulsion, attachment as well as size exclusion. It is worth mentioning that based on the reports this kind of treatment is not influenced by the chlorine membrane aging (Kreiβel et al., 2012; Chaudhry et al., 2015a; Gentile et al., 2018; Jacquet et al., 2021). NF has attracted greater attention because of its facile manufacturing and very small pore size ranging in 15–40 nm, which increases its efficacy by size exclusion. In addition to remove viral markers via NF, it does not leave any trace of plasma proteins denaturation. Besides, other reports have shown that NF has the capacity to remove nonenveloped viruses, which are resistant to solvent/detergent treatment (Doodeji and Zerafat, 2018; Singh et al., 2020). The main factors that can affect the efficacy are membrane pore size and virus dimension, the operation pressure, protein concentration as well as volume filtered (Roth et al., 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, RO membrane can be applied for wastewater treatment in areas with restricted access to water with about 85% recovery efficacy for the rejection of salts, pathogens, and chemical contaminants (King et al., 2020). Moreover, the membrane replacement is inevitably required after a certain number of pressurized times (about 4000 times); otherwise, the efficacy diminishes down to below the standard level of virus removal, or using a secondary treatment approach like UV irradiation may be obligatory (Torii et al., 2019b). Thus, a criterion, called replacement frequency, seems to be really critical for this kind of advanced treatment (Torii et al., 2019a; Saadati et al., 2021). The advances in nanotechnology have stirred the interest in the development of nanocellulose-, nanochitin- and generally biodegradable polymer-based virus removal filters focusing mainly on the adsorptive type filters acting via electrostatic interactions rather than size exclusion (Hamed et al., 2016; Nosrati et al., 2022; Shokri et al., 2022).

Fig. 4 shows the application of MF, UF, NF and RO technologies for the different virus's removal in wastewater treatment is compared.

Fig. 4.

Application of microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration and reverse osmosis technologies for the removal of different pollutants (including virus and bacteria) in wastewater treatment (Designed by the authors of the present work).

4.4. Anti-fouling strategy and its impact on virus removal

The membrane fouling is a serious challenge leading to more energy consumption, declining the flux as well as reduction in removal performance (Mirzaie et al., 2021). This phenomenon is not only responsible for the permeability and performance reduction, but also for the energy consumption increase. The deposition of particles, macromolecules and colloids on the membrane surface results in external fouling (Gopakumar et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2017; Gentile et al., 2018; Roth et al., 2020; Jacquet et al., 2021). External fouling commonly referred to as the fouling layer is divided into two types: the crust layer and the gel layer. The crust layer is formed by the deposition of trapped solids on the membrane surface, while the gel layer is mainly formed due to the gelation of colloids and solutes such as clusters of biopolymers and soluble microbial products on the membrane surface (Bosch, 1998; Doodeji and Zerafat, 2018; Seidi et al., 2020a; Singh et al., 2020). Internal fouling occurs due to the precipitation or adsorption of solutes or particles in the internal membrane structure. This type of fouling, also known as pore blockage, results in narrowing or clogging of the membrane pores (Torii et al., 2019a; Saffarimiandoab et al., 2021). Furthermore, the temperature is the factor that changes the cake layer, porosity, fouling rate and sludge stabilization, which strongly affect the treatment process. The microbial community, as well as the morphology of sludge, can also be influenced by temperature all of which change the fouling rate (Gao et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Gurung et al., 2017).

Regardless of the pollutant filtered/removed by membranes, high rate of fouling weakens the efficiency of filtration, which would be the case for virus removal. Since fouling happens irreversibility, removal of bacteria would be stopped afterwards. Modification techniques can affect factors such as the charge, roughness, and/or hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity to enhance the membrane performance. Fig. 5 depicts, in a short view, the miscellaneous techniques along with mechanisms underlying fouling inhibition (Gopakumar et al., 2017; Saffarimiandoab et al., 2021). For instance, a group of scientists indicated that membrane modification techniques enhanced five times in logarithmic scale the removal capability with respect to the naked membranes (Lu et al., 2017). As another example, polysulphone (PSF) known as the most repetitive ultrafiltration chemically stable membrane, was modified by ZrO2, TiO2 and Al2O3 nanoparticles to decrease the fouling rate of the membrane (Lu et al., 2017; Parnicka et al., 2021). Overall, there are several factors affecting the membrane fouling, but mainly they can be counted as: (1) the size of particle or solute; (2) the microstructure of membrane; (3) the interactions between membrane, solute and solvent; and (4) the surface roughness, porosity and other physical properties of the membrane (Liu et al., 2019). Nanoparticles affect the pores and the surface of the membrane, helpful to control the fouling rate of membrane (Marandi et al., 2021; Zarrintaj et al., 2021; Nasrollahi et al., 2022; Vatanpour et al., 2022a). Careful selection of nanoparticles leads to uniformity in the pore size making the membrane controllable for the removal of any contaminants whatever their size. The occurrence of particulate fouling is a function of the membrane surface properties (i.e., morphology and topography), feedwater characteristics (i.e., the type of fouling agents present, their concentrations, and their physicochemical properties such as size and surface charge), the chemistry of feed (i.e., solution pH, ionic strength and charge interactions), as well as the operating conditions (i.e., temperature, pressure, flux and cross-flow velocity (CFV)) (Seidi et al., 2020b; Vatanpour et al., 2021b; Nowosielski et al., 2022). Generally, smoother membranes with enhanced hydrophilic characteristics and lower charge surfaces are less likely to experience particulate fouling. On the other hand, hydrodynamically stressful operating conditions featuring high membrane flux rates and/or low CFV can cause severe membrane damage (Farshchi et al., 2021a; Vatanpour et al., 2021a). For virus removal, however, nanoparticles can be effective where they are used individually, as comprehensively discussed in terms of mechanisms and properties (Ju et al., 2021). Table S6 in SI highlights the mechanism of antifouling performance of nanoparticles frequently used in membrane fabrication, the properties of membraned modified by nanoparticles and also some operating circumstances.

Fig. 5.

Miscellaneous materials/techniques as well as mechanisms controlling fouling in membranes via modification techniques (designed by the authors of the present work).

On the other hand, the membrane fouling of the MBR system can be briefly divided into colloidal fouling, organic fouling, inorganic fouling, and biofouling according to the properties of pollutants (Torii et al., 2019b; King et al., 2020). Combinations of the aforementioned types of fouling commonly occur in MBR. Organic fouling occurs in the MBR when organic molecules such as carbohydrates, humic acids, proteins, polysaccharides and other organic substances are deposited on the membrane (Seidi et al., 2022). Sources of organic molecules that cause organic fouling may be microbial metabolism and/or water supply. Organic substances such as soluble microbial products and extracellular polymers produced by microorganisms are known as major contributors to organic fouling (Kreiβel et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Moreover, in most cases, organic fouling can be associated with organic-inorganic polymers (chelate polymers) formed as a result of the interactions between the metal cations and some functional groups in organic materials (Lu et al., 2017). Inorganic fouling of bioreactor membrane technology (ICBMs) refers primarily to the chemical deposition of inorganic crystals (Carducci and Verani, 2013; Gurung et al., 2017). Chemical reactions between metal cations such as Mg2+, Ca2+, Al3+ and Fe3+ and anions such as OH−, PO4 3−, CO3 2− and SO4 2− result in chemical deposition in scale formation. Biofouling in MBR is caused by the attachment and growth of microorganisms on the membrane surface or pores that occur during long-term operation (Kreiβel et al., 2012; Cornejo et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2015; Meng et al., 2019; Asif and Zhang, 2021; Zhu et al., 2021). Gradually depositing and multiplying microorganisms can significantly reduce the MBR performance (Rosman et al., 2018). It is now important to promote the initial attachment of bacteria and subsequent growth of the membrane surface.

The fouling in MBR process can be of three possible kinds; reversible, irreversible and irrecoverable fouling. Physical cleaning methods such as backwashing and periodic filtration (mitigation) can be used to remove this type of fouling. (Bosch, 1998; Hakizimana et al., 2017; Mameda et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2019). The size of contaminant particles and membrane pore in an independent and/or interrelated manners affect the formation of a thin layer, known as cake layer formation, which is mutually dependent to the blocking (Broeckmann et al., 2006). The formation of such a layer of virus on the surface of membrane considerably governs the removal efficacy of membrane (Yin et al., 2015). Catalytic nano-ceramic membranes are outstanding because of their high stability and antifouling demeanor (Farshchi et al., 2021b). Moreover, physicochemical processes such as ozonation have been used for years as fouling controllers (Meng et al., 2019; Asif and Zhang, 2021). The search for alternatives to combat membrane fouling is paramount to the cost-performance tradeoff of treatment technology for virus removal in water purification.

5. Virus removal by disinfection processes

Pathogen inactivation is a prerequisite for the effective inhibition of disease spread. Disinfection procedures are basically designed to meet this goal (Madaeni et al., 1995; Ghernaout et al., 2020). Although this approach seems promising in terms of virus removal efficiency, the main concern is the formation of disinfection by-products (DBPs) as a consequence of incomplete reaction of the chemicals with either organic or inorganic precursors. Henceforth, it seems necessary to figure out how to eliminate DBPs besides opting for a disinfection method (Collivignarelli et al., 2018; Pichel et al., 2019; Ao et al., 2021). To name but a few critical factors like the type of microorganism in the disinfection process affect the ultimate quality of effluent, the toxicity of the opted disinfectant component, DBPs formation, as well as cost-effectiveness (Srivastav et al., 2020). Although having DBPs seems inevitable, the combination systems can reduce the amount of disinfectant compared to an equivalent individual system. Additionally, the elimination of organic substances that can react with the chlorine and produce DBP is a solution. Some also recommend reduction of the contact time and/or the concentration of chlorine in the distribution system that ensures adequate turnover in the storage tanks and lower the possibility of stagnant water spots. Moreover, reduction of “water age” (the time it takes for the water to be transported from a water resource to a consumer in the water distribution system), can change the spots where chlorine is accumulated or addition of booster chlorination, and the use of a different type of disinfectant are other helpful strategies to reduce a large amount of DBPs (Tryby et al., 2002). Additionally, since long ago, UV radiation, chlorine/chlorine dioxide as well as ozone are the frequent disinfection options (Organization, 2017; Collivignarelli et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the existing techniques not only suffer from DBPs formation but also pathogen regrowth. Similarly, the abovementioned membrane filtration systems have low outcomes compared to the expectations and huge energy consumption (Bodzek et al., 2019). Additionally, they are mostly applicable for centralized systems rather than developing localities. Hence, there is a serious demand for more efficient techniques with higher efficacy, energy effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, facile in centralized areas and enforceable for decentralized systems (Suthar and Gao, 2017).

Using practical nanomaterials (NMs) that activate physical disinfection is a more trustworthy approach, which interacts with the microbial contaminations and inactivate them via inducing disturbance transmembrane electron transfer as well as RNA or DNA oxidization (Sato et al., 2011; Huo et al., 2020). Among miscellaneous NMs, silver nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes as well as titanium dioxide in the nanoscale are preferable due to the fact that they have outstanding electronic and biological features both of which make them more appropriate for disinfection (Huang et al., 2012; Pietroiusti, 2012; Ojha, 2020). According to the reports, the generation of free radicals and cell decomposition are the mechanisms of action that cause disinfection. This is the reason why NMs do not produce significant quantities of DBPs and there is no trace of pathogen regrowth after utilizing them. It is worth reminding that applicability to decentralize is another key factor of NMs-based disinfection (Alvarez et al., 2018; Hodges et al., 2018; Mauter et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019a). Moreover, semiconductor-based photocatalysis is reported as another simple approach to save energy (Marandi et al., 2021). For instance, g-C3N4 based photocatalysis, metal-organic templates, as well as layered hydroxides are promising photocatalysts for virus removal systems. Unfortunately, there is no current option for SARS-CoV and COVID-19 photocatalytic disinfection (Habibi-Yangjeh et al., 2020; Łuczak et al., 2021; Seidi et al., 2021a).

5.1. Chlorination process

Chlorination is a well-known commonly-used disinfection approach for fouling reduction and wastewater viral disinfection, particularly viral genomes (Kong et al., 2021). Although chlorination is a well-known procedure, it has plenty of demerits. To name but a few, DBPs formation, being incapable of treating some specific types of microbes, and having a detrimental effect on some kinds of membranes such as cellulose acetate (CA) membranes can be addressed as disadvantages (Shokri et al., 2022). Albeit some membranes such as polyamide (Papp et al., 2020) ones are reported as far more resistant to chlorine, they suffer from weak treatment efficacy. Additionally, chlorination is a cheap anti-biofouling method in reverse osmosis membranes, but it diminishes the mechanical properties such as ductility and strength over time (Al-Abri et al., 2019). Chlorination is a good option for combinational treatments. For instance, the conjunction of UV treatment with chlorination brings a greatly advanced treatment in order to degrade the micropollutants and to eliminate some bacteria and viruses (Zhang et al., 2019b).

Chlorination can also be performed using hypochlorous acid, sodium hypochlorite, calcium hypochlorite, chloramines, chlorine dioxide as well as dichloroisocyanurate (Furst et al., 2018; Greaves et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2021; Prasert et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022). The inactivation process can be carried out by using chlorine via oxidizing sulfhydryl enzymes, amino acids chlorination, oxygen uptake reduction, as well as DNA synthesis inhibition. Although the chlorination-based systems are really practical, they are more influential on bacteria compared to the viruses. The reason is that the capsid protein denaturation of viruses is somehow resistant, which mainly suffers from byproducts generation, which are sometimes severely toxic and carcinogenic (Wang et al., 2020a; Kataki et al., 2021). Table S7 in SI gives a summary of the virus removal efficiency from various water and wastewater sources using the chlorination process.

5.2. Hydrogen peroxide

Due to the fact that almost all of the chlorine-based disinfectants can produce DBPs depending on the type of compounds and operating conditions, there is a serious demand for alternative biocides like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Luukkonen and Pehkonen, 2017). Several studies have been conducted to compare the efficiency of chlorine-based systems and H2O2. For instance (Piazzoli et al., 2018), designed an experiment to recognize whether the efficiency of UV/free chlorine (UV/HOCl) is more than UV/H2O2. In terms of toxicity and byproducts, UV/H2O2 accelerated the formation of iodoacetic acid, which is reported as a severe toxic compound. Some other scientists believe that combinational treatments with H2O2 can bring about great outcomes for removal of microorganisms. For examples, monochloramine (MCA) combined with H2O2 reported by Yang et al. can pose a significant impact on the bacterial viability within the wastewater after less than 60 min. They demonstrated that the mentioned platform declines the concentration of Denitratisoma and Thauera within the media (Yang et al., 2017). Additionally, inducing a high oxidation effect after utilization of UV/H2O2 is the reason that encourages scientists are focused on such kinds of treatments (Asghar et al., 2015; Gassie and Englehardt, 2017). It is worth stating that a critical demerit of chlorine disinfection is that it may lead to chlorine-resistant bacteria generation (such as Bacillus cereus), which is a threat to human health in further steps. This is another driving force why the alternatives like UV/H2O2 and UV/peroxymonosulfate (UV/PMS) are the topics of numerous new studies (Zeng et al., 2020).

5.3. Ultraviolet irradiation

Although ultraviolet (UV) irradiation has been confirmed by plenty of studies as a robust tool to inactivate the microorganisms within the wastewater, some other aspects of microbial inactivation must be taken into account. One of these aspects is the antibiotic resistance gene (ARG), which is a critical issue. UV is utilized not only for the disinfection as a potent replacement, but also for ARG deterioration. State of the art UV-LEDs possess a higher treatment and energy efficacy in comparison with the classical UV lamps depending on the wavelengths, irradiation continuity, pulse frequencies, duty cycle, as well as the type of microorganism (Umar et al., 2019). Based on the reports, pretreatment with ozone as well as combinational treatment of wastewater can strongly evolve the efficacy of UV treatment (Shi et al., 2021). Some other results demonstrate that PAA-UV/PAA has outstanding outcomes for Escherichia coli (E. coli), Escherichia durians (E. durians) as well as Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) treatment. The same results also indicated that by using this platform no regrowth or minimal regrowth potency occurs after disinfection (Zhang et al., 2020). It is worthy to state that UV irradiation can swiftly shatter antibiotic-resistant bacterium (Prado et al., 2019) and comprehensively eliminate ARGs like vanB (Wang et al., 2020b). Table S8 shows a summary of the virus removal efficiency from various water and wastewater sources using the UV process.

5.4. Ozonation process

Ozone is a strong oxidizer that has been widely utilized for the removal of organic pollutants and microorganisms (Bui et al., 2019; Wang and Chen, 2020). Nonetheless, the toxicity issues remain by its power and organic pollutant mineralization does not occur to a high degree. Some scientists suggest that the hybrid ozonation process which is consisted of two main techniques leads to accelerated hydroxyl radical generation that can affect the toxicity (as the main concern) and efficacy for virus removal (Malik et al., 2020; Wang and Chen, 2020). Catalytic ozonation is another template that has attracted plenty of scholars. The utilization of catalysts (which can be homogeneous and heterogeneous such as metal ions and oxides) brings about concentrated active free radical generation that leads to pollutants degradation promotion and virus elimination, which depended on the pH (Wang and Chen, 2020; Seidi et al., 2021b). However, some investigations suggest that ozonation combined with activated sludge filtration is appropriate to inactivate microbial contamination even to a lower degree than standards required to reuse drinking water in various applications (Alfonso-Muniozguren et al., 2018). Concluding, albeit ozonation can be referred to as a proper alternative for water treatment, there exist some contradictions which can be the topic of further studies.

5.5. Sunlight mediated wastewater disinfection

Complicated sequences of mechanisms (such as exogenous) happen after exposure of contaminated wastewater to sunlight and these sequences can lead to microorganisms’ inactivation (Wilczewska et al., 2022). The rate of inactivation, as well as ultimate microbial concentration, are highly dependent on solar spectral irradiance, the vulnerability of the organisms as well as environmental conditions such as the water quality (i.e., the concentration of other dissolved species) (Nelson et al., 2018; Deshpande et al., 2020). To authentically foresee the effect of environmental conditions on the disinfection process, several models have been proposed, however, there still are some vague mechanistic points that can be the topic of further studies. For example, Moringa oleifera seeds (Papp et al., 2020) with silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) have been reported as a perfect antimicrobial active sunlight mediator for wastewater disinfection with also a great ability of organic material degradation (Mehwish et al., 2021). One interesting study aimed to compare the disinfection result for E. coli, Echovirus and Norovirus show that the dark condition has the ability to eliminate these microorganisms where the disinfection efficacy is far better when the samples are exposed to sunlight (Park et al., 2021). Moreover, these authors demonstrated the highlighted dependency of light wavelength on the outcomes. However, the reality is that the exact mechanism of disinfection within the dark laboratory was ambiguous (Park et al., 2021). Another research group revealed that the treatment of E. coli within the wastewater via sunlight mediation is highly dependent on pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO) as well as sunlight intensity (Chambonniere et al., 2020).

5.6. Advanced oxidation processes

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are emphatically reported as the heart of the wastewater treatments contributing to virus removal. They generate high amounts of free radicals, which make them more efficient. The generation of these radicals can be intensified in the presence of activators such as iron-based materials, light and electricity (Luo et al., 2021). These systems can imply different operational schemes (Fig. S5). To name but a few, plasma activation, AOP-Bioremediation, catalyzed-based as well as membrane-based AOPs are known. This type of water treatment technology is considered energy effective with acceptable compatibility with the existing biological treatment procedures. Nonetheless, they can also face technical challenges such as membrane fouling in the membrane-based AOPs (Miklos et al., 2018; Giwa et al., 2021). Some studies propose that using AOPs combined with hydrodynamic and acoustic cavitation can lead to a higher quality of water treatment. Albeit hydrodynamic can eliminate a wide range of contaminations lonely, it lacks the efficacy to remove different microorganisms. This is why some authors suggest the conjunction of AOPs with other treatment forms such as ozonation, UV as well as hydrogen peroxide treatment that brings more comprehensive disinfection. Additionally, they comment that the treatment process efficacy can be pointed out as a function of temperature, pH and other species dissolved (Gągol et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2021). Several microorganisms are resistant to UV irradiation like Adenovirus. Therefore, the application of hydrogen peroxide or other strong oxidizers with UV irradiation can significantly improve the virus inactivation performance (Bounty et al., 2012). In this direction, Kokkinos et al. have reviewed and analyzed the performance of AOPs for viral removal concluding that a combination of two or more treatments is required to achieve a proper level of virus removal (Kokkinos et al., 2021). UV irradiation and H2O2 are the oxidation process more frequently applied in the literature. However, AOPs intensified with microwave, sonication and electrical fields are alternative technologies to eliminate viruses and other microorganisms in water (Kokkinos et al., 2021).

6. Virus removal by combining technologies

Viruses have higher resistance and stability than other pathogenic microorganisms during wastewater treatment. Moreover, they may stick on the sludge, suspended material and effluent liquid from WWTP and become highly settled. Thus, combinational treatment technologies have been repetitively used for their synergistic effect which strongly enhances the removal efficacy (Ghernaout, 2019). For instance, Microbiological ultrafiltration can eliminate Cryptosporidium and Escherichia coli effectively (Ferrer et al., 2015). However, it has not the capability to remove Noroviruses (Yasui et al., 2016), Adenoviruses (Yin et al., 2015), Rotaviruses (Qiu et al., 2015), and bacteriophages (Ferrer et al., 2015) because of the pore sizes (pores are not small enough). Hybrid-ozone membrane filtration is the most well-known type of hybrid membrane which is a short-cut way to prime the requisites of efficient treatment (Hakizimana et al., 2017; Mameda et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2018; Rosman et al., 2018). Adsorption or coagulation can be utilized to develop hybrid processes to improve virus removal. For instance, the removal of virus by combined coagulation-ultrafiltration process is depended on the acidity, where an optimized pH ∼5.5 can accelerate the removal efficacy (Lee et al., 2017b). Moreover, a combination of membrane technologies with electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs) is utilized for fouling reduction as well as rejecting pollutants and removal of viruses. EAOPs such as electrochemical anodic oxidation, electrocatalysis, as well as electro-Fenton can be used as pre-or post-treatment in conjunction with membrane technologies such as nanofiltration and reverse osmosis (Pan et al., 2019). Additionally, a combination of activated carbon adsorption, coagulation as well as chlorination with reverse osmosis membrane technology can accelerate the virus removal rate up to 99%. The intensification of photocatalysis with hybrid systems can also effectively enhance the virus removal based on the results reported in some studies (Lee et al., 2017a; Oller et al., 2018). To reduce the concentration of viruses and N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a combination of three technologies consisting of ozonation, coagulation, and ceramic membrane filtration process was recommended, which accelerated the operating performance (Im et al., 2018). Fig. S6 shows the effect of combining technologies on the removal performance of viruses and other water pollutants.

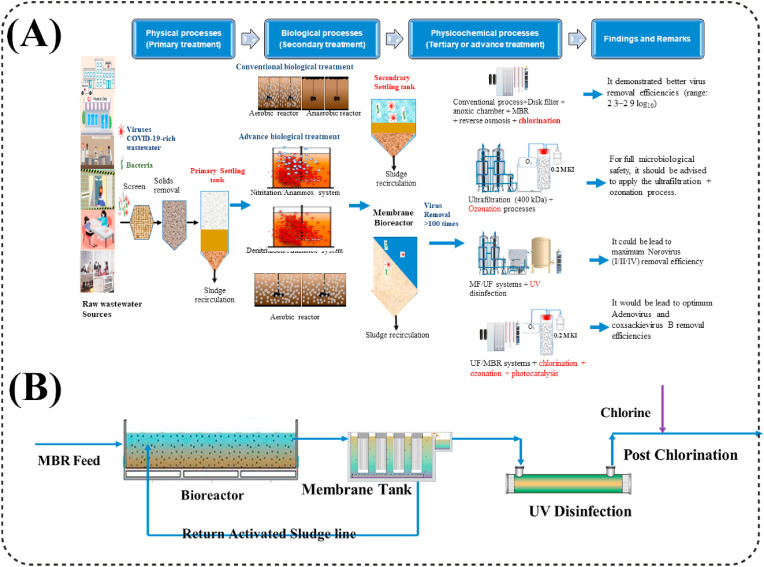

As demonstrated in Fig. 6 A, the wastewater treatment consists of three stages primary (physical), secondary (biological) and tertiary or advanced (physicochemical) stages for viral pathogenic removal. All stages can contribute to remove pathogenic viral in different proportions (i.e., the virus removal efficiency follows the next trend: primary stage < secondary stage < tertiary or advance stage). Prado et al. (2019) demonstrated better virus removal efficiencies (range: 2.3–2.9 log10) by applying combined systems including conventional process, disk filter, anoxic chamber, MBR, reverse osmosis and chlorination. Further, the result of virus particles was (1.0 × 105/mL) after the ultrafiltration process only (Bray et al., 2021). For full microbiological safety (Bray et al., 2021), advised that combined ultrafiltration (400 kDa) and ozonation processes should be applied. Virus removal is generally not effectively by UF and MF, due to their small size. So, it has been suggested that combined MF/UV processes with a photocatalytic membrane for high bacteriophage P22 removal efficiency (LRVs = 5.0 ± 0.7) compared to MF/UV disinfection with a non-photocatalytic membrane (Guo et al., 2015). According to (Chen et al., 2021c), combined MF/UF systems and UV disinfection may lead to maximum Norovirus (I/II/IV) removal efficiency and simultaneously combining UF/MBR systems with chlorination/ozonation/photocatalysis processes would be lead to optimum Adenovirus and coxsackie B virus removal efficiency. In fact, the primary role of disinfectant in the membrane-based purification processes is to enhance water permeation into the membrane. This effect was found to be more probable for thinner membranes. On the other hand, disinfectants leads to lowering the operating lifetime of the membrane (Eslami et al., 2020). Therefore, the operating lifetime of the membrane could be governed by the use of disinfectants and the resulting mechanisms. Functionalization of membranes and/or nanoparticles compensates for such a negative effect. According to experimental investigations the use of disinfectants leads to destabilization of the membranes, such that small viruses might be trapped. Thus, using a complementary process (combination of the use of disinfectant and a complementary process) facilitates the removal of small-size viruses trapped in the porous structure of membranes (Ly and Longo, 2004; Wang and Dea, 2009; Dohare and Trivedi, 2014; Fiani et al., 2020).

Fig. 6.

(A) Schematic of combining three-stage physical, biological, and physicochemical processes in various technologies for virus removal performance in wastewater treatment, partially adapted from (Guo et al., 2015; Bray et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021c) (B) Schematic of combination of MBR and disinfection technologies for efficient virus removal in wastewater treatment (Designed by the authors of the present work).

Auxiliary tools for virus elimination are membrane bioreactors (MBRs) which are becoming common treatment methods. MBRs are effective in treating a wide range of contaminants even at very low levels of pollution (O'Brien and Xagoraraki, 2020a). Typically, a disinfection system acts as a physical barrier for elimination of bacteria and other pathogens, necessitating a complementary disinfection process, such as chlorination or UV radiation, when the detectable limit for bacteria is hard to achieve by MBR (Hai et al., 2014). A simple design of this hybrid process is illustrated in Fig. 6B. It is shown that the disinfection system is put in practice after MBR system. Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) and electrocatalytic membrane reactors (EMRs) have some drawbacks such as their low efficiency of photocatalyst and instability of effluent quality, which limited their application. Nevertheless, virus removal efficiency of PMR has been barely investigated unlike MBR system, which led to some commercialized products (Zheng et al., 2015).

Manufacturing cost of catalytic membrane preparation and modules, limited membrane life time, anomalous nature of chemical reaction processes in some cases as well as the complexity of the process should also be taken into account in development of such processes. Therefore, attention has been directed towards modeling and simulation of processes, to compensate for the low permeability of highly selective (dense) membranes at medium temperatures (Poto et al., 2021). Table 2 compares different processes in terms of their functionality, merits and demerits. It is evident from the table that each process has its strength and weakness, while combined systems are more efficient with relatively lower drawbacks.

Table 2.

Comparison of different single and combinatorial methods in wastewater treatment for virus removal (Chen et al., 2021b).

| Process | LRVs | Major function mechanism | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBR | 1.40–7.10 | Virus attaches to the mix of liquor solids; control by membrane by cake layer; enzymes inactivate viruses | High flux and removal efficiency, less space demand | Removed incompletely dissolved organic matters (<500 kDa); high cost for operation and maintenance |

| MF | 0.70–4.60 | Adsorption significantly by membrane surface or pores; followed by size exclusion | High permeability; low pressure-driven process | Less removal efficiency; humans' health risk potential |

| UF | 0.50–5.90 | Retention by membrane and Adsorption significantly by membrane surface or pores | High permeability and flux; low initial cost and efficiency removal of high molecular weight pollutants | High cost operation and maintenance; high fluctuate removal efficiency |

| NF/RO | 4.10–7.00 | Size exclusion; Electrostatic interactions | High performance and reliability, specific removal of enveloped and nonenveloped viral based only on size-exclusion | High facilities and requirements for high quality removal |

| Chlorination | 1.00–>5.0 | Degradation of protein, nucleic acid and viral capsid | Easy operation, economically method | formation of DBP, corrosive, residual toxicity |

| UV radiation | 0.09–5.00 | Lesions formation in virus genome and degradation of genome and protein cross-link | Without formation of DBP, low contact time, short process and space, without extra chemicals, low sensitivity of pH and temperature | Low efficiency for residual disinfection, high level of energy consumption in UV-LEDs |

| Ozonation | 0.60–7.70 | Formation of free radical from interaction of water and ozone | low contact time, inactivation of viruses | No residual disinfection efficiency, high energy consumption |

| Photocatalysis | 1.00–8.00 | Redox reaction of some reactive species with visible or UV light | Easy preparation, favorable catalytic process, low operation cost, good stability | Detect low quantum yield for a few materials; low efficiency |

| Electrocatalysis | 3.40–5.00 | Redox reaction in electrolysis cell | Applicable for specific viruses | Electricity consumption |

Note that there are other intensified treatment technologies that can be applied to conduct the virus removal from water (Zamhuri et al., 2022). For example (Dular et al., 2016), reported the use of a pulsating hydrodynamic cavitation reactor as a step-in water treatment for the reduction of waterborne enteric viruses. The authors have treated the spiked tap water sample using a Venturi cavitation chamber with a pulsating system (400 passes through the Venturi chamber). Preliminary results of the differences between spiked samples before and after cavitation suggested a promising performance of hydrodynamic cavitation with a 75% reduction in the detected Rota virus genomic RNA achieved with the cavitation treatment of the sample. Table 3 compares nanomaterials used as adsorbent or in the development of membranes for virus removal and their pros and cons.

Table 3.

Comparison nanomaterials for adsorption or membrane process in virus removal and their pros and cons.

| Material Family | Example | Method | Type of Virus removed | pros and cons | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | Granular activated carbon (GAC) | Adsorption | Bacteriophage MS-2 | -ACFC adsorbent was more efficient for virus adsorption than GAC; -Due to its shape, GAC was not the best adsorbent for virus besides both surface areas are comparable - Carbon family is a common family for membrane and adsorption process |

(Powell et al., 2000; Ahmed et al., 2012) |

| Activated carbon fiber composite (ACFC) | |||||

| Poly-N-vinyl carbazole- single-walled carbon nanotube (PVK-SWNT) | Membrane | Bacteria | |||

| MOF | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Adsorption/Membrane | Zika, Dengue, human immune deficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and Japanese encephalitis virus and SARS-CoV-2 | -It has been shown that the textural properties (pore size and volume), crystal morphology and chemical functionality of MOFs can be modulated to obtain specific performances for virus removal; -MOFs-based materials have also been used to develop sensor for detecting Zika, Dengue, human immune deficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and Japanese encephalitis virus with promising results -They induce synergistic properties into nanostructured polymeric membranes |

(Riccò et al., 2018; Gohil and Choudhury, 2019; Rabiee et al., 2022) |

| Zeolite | Zeolite | Adsorption/Membrane | Coronavirus 229 E | -Silver and copper-doped zeolites can induce a significant reduction of the presence of the Coronavirus in water solution after 1 h of treatment; -The functionalization of zeolite via silver and copper, i.e. metals presenting known antibacterial properties, has been shown to be an efficient way to inhibit Coronavirus; -The adsorption mechanism was explained by the surface charge, hydrophobicity and surface properties of pathogens and NPs matrix; -It was shown that the removal efficiency of Fe3O4–SiO2–NH2 NPs over bacteriophage f2 and Poliovirus-1 are more than 97% - It can offer high thermal stability and chemically robust structure |

(Pendergast and Hoek, 2011; Mintova et al., 2015; Mobed et al., 2021) |

| Hybrid nanomaterials | - Silica-decorated TiO2 - Polyvinyl alcohol/Polyacrylic acid/TiO2/Graphene Oxide |

Adsorption/Membrane | Bacteriophage MS-2 | -It was shown that doped-TiO2 including 5% of SiO2 has a 37-fold enhanced viral removal performance compared to pristine TiO2; It shows significant removal percentage for membrane method -It was suggested that this removal approach has the advantage of using low-cost and green materials. |

(Moon et al., 2013; Sellaoui et al., 2021) |

On the other hand, the plant viruses spread by water might wipe out the whole crops, resulting in financial losses and food shortages. Potatovirus Y (PVY) is a serious viral disease that affects other crops (Gong et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022). It was recently discovered that PVY may infect host plants via water, underscoring the need to properly clean recycled water to prevent infectious organisms from spreading. Reclaimed irrigation water has been treated using new environmentally friendly technologies such as hydrodynamic cavitation (HC) (Filipić et al., 2022). They have treated the water samples laced with pure PVY virions with laboratory HC with a sample volume of 1 L. They have noted, after 500 HC passes, or 50 min treatment at 7 bar pressure difference, that the virus can no longer infect plants. In other cases, shorter treatments of 125 or 250 passes were also beneficial. The HC treatment harmed viral particle integrity and resulted in little RNA damage. PVY inactivation by HC was not primarily caused by reactive species such as singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radicals, or hydrogen peroxide, suggesting that mechanical forces are the primary driving mechanism.

Recently, Wierzbicki et al. reported that the use of ultrasound can be beneficial to damage the Coronavirus (Wierzbicki et al., 2021). The construction of a practical geometrical and computational model of the viral shell decorated with spikes, based on the limited information in the literature was reported elsewhere. The fully nonlinear simulation of the forced vibration revealed the true character of the viral response to harmonic waves. It has been shown that harmonic vibration at or below the lowest resonant modes can excite large amplitude vibration of spikes. The associated maximum principal strain in a spike can reach large values in a fraction of a millisecond, which leads to the tearing of the spikes from the shell (Wierzbicki et al., 2021). Another important result reported by the authors is that after a finite number of cycles, the shell buckles and collapses, developing internal contacts and folds with large curvatures and strains exceeding 10%. For the geometry and elastic properties of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, these effects are present in the range of frequencies close to the ones used for medical ultrasound diagnostics.

7. Environmental concerns and challenges

The presence (or the ability to detection) of viral genetic materials in wastewater can be used to monitor the spread and clearance of viruses in communities (Ajiboye et al., 2020; Assadi et al., 2021). Effective wastewater and water treatment are centered to disease control. Detection of viral genetic materials in wastewater requires a virus enrichment step to ensure detection and identification of microorganisms, but the current knowledge state is indeed limited (Sivasankarapillai et al., 2020; Fahimirad et al., 2021). Understanding how viruses are inactivated and/or eliminated in the aquatic environment is also important for assessing risks to human health. The stability of the viral genome in wastewater is unclear. Effective removal techniques can help prevent viruses from entering the environment faster (Lahrich et al., 2021).

All the treatment methods described in this article have different advantages and disadvantages, but we believe that the combination of these systems can overcome their technical and/or economical limitations — thus favoring their potential implementation at a larger scale. Therefore, a few points should be noted correspondingly:

-

1)

Some methods are environmentally friendly and do not use toxic or hazardous chemicals; thus, provide the consumer with drinking water with the highest quality and least possible risks (Gavrilescu et al., 2015).

-

2)

Some methods can be used, integrated and intensified to reduce their operational costs in comparison with conventional disinfection methods, and then by evolving them towards commercialization and making them available to all people all around the world (Ao and Zayed, 2021).

-

3)

Membrane processes can be names as decentralized wastewater treatments with the potential to meet the standard needed for sustainable urban water management with lower resource-intensive and higher cost-effective burdens than the centralized approaches. This review has examined the potential of some technologies in the context of sustainable decentralized sanitation. It is argued that the combination of membrane technology within decentralized systems can satisfy several criteria for sustainable urban water management (Fane and Fane, 2005; Jegatheesan et al., 2021).

-

4)

Since the effectiveness and evaluation of a country's wastewater treatment system cannot be concluded simply, always we need appropriate implementation of virus removal strategies supported by laws, policies, and guidelines. This can be achieved using the most cost-effective and efficient technologies (Akpor, 2011).

-

5)

Semiconductor-based photocatalysis is a potential alternative technology with valuable merits in terms of facility, high efficiency, and energy-saving procedure to inactivate various viruses present in water, air, and foods. To use sustainable resources in the photocatalytic viral inactivation processes, it is highly desired to develop more efficient visible/solar-light-driven photocatalysts to tackle viral issues. Furthermore, magnetically separable materials are also desirable to simplify the separation of utilized photocatalysts from the aquatic systems, which is another bottleneck for the semiconductor-based photocatalytic viral disinfection procedures. Hence, more studies should be conducted to illustrate the potential application of heterogeneous photocatalysis technology to disinfect these viruses. The future scientific studies should be undertaken in the field of heterogeneous photocatalysis processes to gain more insights into the exact potential of this technology in order to tackle the presence of new viruses in water. Consequently, there is no doubt that the heterogeneous photocatalysis viral disinfection technology, with many appealing merits, will be an active research field in the future, which provides effective treatments methods to reduce virus dissemination in the environment via water (Habibi-Yangjeh et al., 2020; Pancielejko et al., 2021).

-

6)

The use of some disinfectants (peracetic acid, performic acid, sodium dichloroisocyanurate, chloramine, chlorine dioxide, benzalkonium chloride) is effective in terms of virucidal properties. However, additional scientific information is needed on the various areas of viral disinfection of wastewater. To combat or reduce the impacts of a virus pandemic, wastewater treatment investigation strategies are required to include regular testing of the effectiveness and dosage of the selected disinfectants, taking into account all factors affecting the viability of the virus, environmental conditions and properties of contaminated wastewater. The qualitative and quantitative components of disinfection techniques and their environmental impacts should also be studied and analyzed in detail to establish the best alternatives (Kataki et al., 2021).

8. Perspectives and future outlook

A number of studies have provided evidence for the abundance of pathogenic viruses in the WWTP, including the novel COVID-19 (Aghamirza Moghim Aliabadi et al., 2022b). Viruses have different resistances compared to the other pathogens and show varying responses to wastewater treatment processes that lead to their persistence and abundance in the waterborne. Thus, a deeper realization of viruses’ characteristics, classification, and behavior in the wastewater treatment processes will provide a guide for future research on virus removal to contribute to mitigating and minimizing the outbreaks of diseases. Therefore, the comprehensive detection and assessment of virus pollution and wastewater treatment process is a fundamental step in this direction. There are some impact factors that should be considered to improve and optimize the virus removal in water treatment:

-

1)

We need to homogenize and standardize the studies and efforts to detect the virus types and classy the wastewater sources through internationalization. For instance, domestic wastewater, industrial wastewater and medical wastewater) that contain different viruses, pathogens and microorganisms can be taken into account for future surveys. In the same context, a large deviation has been identified between the lab-scale experiments and the large-scale application which hardens the verification of treatment efficiencies. Thus, the stability of performance during the long-term operation in the full-scale wastewater system is a key parameter to be analyzed and tested, particularly for the novel methods with the aim of achieving an effective removal of viruses and; thus, avoiding or at least minimizing outbreak disease transmission through aqueous media.

-

2)