Abstract

Cell type identification is a key step toward downstream analysis of single cell RNA-seq experiments. Although the primary objective is to identify known cell populations, good identifiers should also recognize unknown clusters which may represent a previously unidentified subpopulation of a known cell type or tumor cells of an unknown phenotype. Herein, we present MarkerCount, which utilizes the number of expressed markers, regardless of their expression level. MarkerCount works in both reference- and marker-based mode, where the latter utilizes existing lists of markers, while the former uses a pre-annotated dataset to find markers to be used for cell type identification. In both modes, MarkerCount first utilizes the “marker count” to identify cell populations and, after rejecting uncertain cells, reassigns cell type and/or makes corrections in cluster-basis. The performance of MarkerCount was evaluated and compared with existing identifiers, both marker- and reference-based, that can be customized using publicly available datasets and marker databases. The results show that MarkerCount performs better in the identification of known populations as well as of unknown ones, when compared to other reference- and marker-based cell type identifiers for most of the datasets analyzed.

Keywords: Cell type identification, Single-cell RNA-seq, Marker-based identification, Reference-based identification, Cell type markers

1. Introduction

Single-cell RNA-seq technology [1], [2], [3] has enabled the transcriptomic analysis of heterogeneous tissue microenvironments [4], such as the tumor microenvironment, wherein various cell types co-exist. Cell type identification represents an instrumental step in single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Manual annotation can be performed through general work frames for single-cell RNA-seq data analysis, such as Seurat [5], SCRAN [6], SC3 [7], and SCANPY [8], where dimension reduction, clustering, differential gene expression analysis, and marker identification can be performed to manually annotate cell types on a cluster basis.

Automatic pipelines have been developed to facilitate cell type identification and annotation. One approach is marker-based identification, which utilizes lists of known markers for the identification of cell populations. Garnett [9], SCINA [10], and scSorter [11] fall into this class, with several utilizable databases for cell type markers, including Panglao DB [12] and CellMarker DB [13]. Another approach is through the use of reference-based methods, e.g., SingleR [14], scPred [15], scmap [16], CaSTLe [17], and CHETAH [18], which utilize the existing annotation to obtain gene expression profiles of different cell populations to be used for identification.

These tools have sufficient performance for the most part, particularly if all cell types in the test data are already known, i.e., they are present in the reference dataset or their markers are available. However, a good identifier should also be able to successfully identify unknown cell clusters [19], facilitating further study of their transcriptomic characteristics not identified so far. This is a big discrepancy between cell type identification via the general classification approaches, representing an important issue to consider when evaluating cell type identifier performance. This is why other performance measures (such as “correctly unassigned”, “erroneously unassigned”, and “erroneously assigned”) beyond correct and erroneous were introduced to evaluate cell type identifiers [18]. Although most cell type identifiers provide rejection functions to identify unknown clusters, they do not perform satisfactorily [18]. As a matter of fact, there exists a tradeoff between these measures. For example, the “erroneously unassigned” can be reduced by decreasing the rejection threshold. However, the “erroneously assigned” will also increase and vice versa. Another aspect that should be noted is the measurement noise due to an insufficient number of transcript numbers per cell as well as the batch effect caused by different platforms and preprocessing. Most cell type identifiers, especially the reference-based ones, directly utilize the gene expression profiles to train identification models. Gene expression profiles, however, are subject to noise and batch effects, which may compromise performance.

To tackle the above-described problems and improve overall performance, we present MarkerCount, a count-base cell type identifier that supports both marker- and reference-based identification. The overall procedure is shown in Fig. 1, while the detailed description can be found in the Materials and Methods section. Briefly speaking, the processing pipeline of reference-based MarkerCount consists of two steps, (1) selecting markers for given references and (2) identification of cell type utilizing “marker counts” and cluster-wise cell type correction, where the second step can be slightly modified for marker-based identification utilizing the existing cell type markers, e.g., [12], [13]. The key is to set a suitable rejection threshold to determine the “unknown” cell type, which is not present in the set of target cell types. We set a conservative rejection threshold in the normalized marker counts, which potentially yields many “unassigned” cells. To minimize unnecessarily unassigned cells, we reassign cell types by using similarities in their gene expression pattern, i.e., via cluster-basis reassignment.

Fig. 1.

An overview of MarkerCount data processing. MarkerCount operates in both reference-based and marker-based mode. In the former, it requires reference data (a) along with cell type annotation (b) to find makers of each cell type (d), for which the gene-cell type association score (c) is used. In marker-based mode, it uses the existing markers (e). In the test phase, it takes cell type markers and the test data (f) as input. Follwing data processing includes marker counting (g), initial cell type assignment and rejection of unclear cells (h), PCA and clustering (i), as well as the cluster basis reassignment for final identification (j).

Note that, in the current work, the term “cell type” does not follow the strict definition used by biologists. Rather, it may refer to major cell types, such as T cells or B cells, or subpopulations of a major type, such as CD4 T cells or naïve T cells. Most of cell type identifier, even if not all, accept customized list of cell types and their lists of marker genes, which can be quite varied according to specific study objective.

2. Materials and methods

The operation of MarkerCount can be divided into two steps: (1) Find markers for each cell type using reference data and (2) Use markers to identify cell types in test data. As the name suggests, MarkerCount utilizes the number of marker genes that are expressed, regardless of their expression level (transcript count), which can be obtained via the binarized gene expression. The binary expression is used not only to find markers from a given reference (in training phase) but to also obtain the marker counts for initial cell type identification (in test phase).

2.1. Finding markers from reference datasets

Using prior annotation provided with the gene expression matrix, reference cell types are first identified. Let be the set of genes and the gene expression of the th gene in the th cell. We first convert these to binary indicator , which indicates whether the gene is expressed in that cell or not, i.e., if or 0 otherwise. We then compute marker score for cell type as:

| (1) |

where is the set of cells annotated as of type (target cells), and is the complementary set of (non-target cells). is the size of . is simply the occurrence frequency of the th gene in the th cell type. is an hyper-parameter relatively weighing the second term. We set it to 2 in all the experiments. Then, for each cell type , we sort in descending order and select the first genes as its markers. The integer is also a hyper-parameter, which we fixed to 18 for all cell types. The number 18 was chosen, as it showed the best performance for most datasets used in this work. Note that the selection of marker genes is done separately for each cell type, and it is possible for two or more cell types to share common markers. In addition, before comparing the score in (1), one can narrow down the candidate genes by enforcing the condition, for some occurrence frequency threshold , which we opted to set at 0.9 as a heuristic choice. If is close to 1, the number of candidate markers may be too small so that the number of selected markers can be far less than the specified value, . On the other hand, if it is too small, too many markers with a small occurrence frequency in a target cell type can be included. Since most of the references are assumed to contain only a group of cell types, one may obtain unexpected result if is too small, as there are other cell types that have some common markers with a target, but was not in the reference.

2.2. Counting markers

In the test phase, for a given binary expression profile of the th cell, , we obtain the normalized marker count defined as.

| (2) |

where is the set of markers of the th cell type. The cell type is initially determined by taking the maximum of , i.e., , which is accepted if is greater than or equal to the cell type specific rejection threshold, . Otherwise, the cell is marked as ‘unassigned’.

2.3. Obtaining the rejection threshold

The threshold can be obtained in various ways. In this work, we considered two approaches, parametric and non-parametric. In the non-parametric approach, we directly obtain it from ’s. Consider two set of cells for a given rejection threshold , and . The former is the set of cells (in the reference data) of which the true (manually annotated) cell type is , and its normalized marker count is , while the latter is the set of cells identified as the th cell type according to satisfying (1) for all other cell types and (2) . The false positive rate can then be defined as:

| (3) |

where the second term is the true positive rate. The objective is to find such that for a given target FPR, . In the non-parametric approach, one can find by sorting in descending order and find the minimum such that . In the parametric approach, we use a univariate Gaussian mixture model with two components, i.e., for and for . With the relative sizes of and denoted as and , respectively, can be defined as:

| (4) |

The parametric approach is particularly useful for the marker-based operation of MarkerCount, where reference data is not available. Given test data only, one can resort to the bimodal fitting, for which an expectation maximization (EM) algorithm can be used to find for . In reference-based mode, the rejection thresholds for all the cell types are computed in the training phase from the reference data using (3), while, in marker-based mode, it is obtained by (4) applying bimodal fitting to the test data.

2.4. PCA and clustering

Although marker count-based cell type identification works reasonably well, one can improve the identification accuracy by employing cluster basis reassignment. To this end, we first perform dimension reduction via principal component analysis (PCA) with the number of components set at 15 and then perform clustering on the dimension-reduced space. The developed software provides an option to select a clustering algorithm, either a k-means- or GMM (Gaussian mixture model)-based algorithm, for which the number of clusters was set to , similar to Garnett. The user can also provide the cluster labels after performing the clustering by him/herself. Among these options, we used the Gaussian mixture model.

2.5. Cluster basis cell type reassignment

While some clusters have all cells assigned to a cell type, others may not be fully covered or not covered at all. The latter might include unknown cells that do not exist among reference cell types. The former may be a specific cell type that was not fully covered due to a high rejection threshold. In this case, one can reassign cell types to those unassigned cells in a partially covered region in a cluster by cluster fashion. To this end, we first identify cell types that are partially occupying the cluster. With their centroids, covariance matrices and size, we reassign a cell type to those unassigned cells by comparing their distances from the centroids as follows:

| (5) |

where is a dimension-reduced gene expression profile of a cell, are the centroid (mean), covariance matrix, and the relative size of the th cell type that resides in the cluster, respectively, while is a regularization constant, which we set at 0.1 of the average variances. By comparing the weighted Mahalanobis distance in (5) of an unassigned cell from the centroids for the cell types in that cluster, we determine cell type based on the closest one. Reassignment is performed if the portion of unassigned cells is below a certain threshold, say 0.8. This value was chosen as it exhibited the best performance in the range of 0.1–0.9 at 0.1 steps. While more sophisticated methods can be devised, we opted for this rather simple heuristic approach.

Most cell type identifiers, including MarkerCount, utilize clustering and assign cell types on a cluster basis, i.e., all the cells in a cluster are assigned the same label. This means that identification performance can be limited by the clustering resolution. When performing cluster-based annotation, one encounters three cases of correspondence between a cell population and a cluster, i.e., they can be one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-one, with the last case causing errors. Although this problem can be avoided by performing clustering with high resolution settings (with a high number of clusters), cluster number can be also problematic if too high, since statistical profiling of marker gene expression becomes inaccurate if the cluster size is too small. Currently, there are no rules to determine the best clustering resolution. Thus, we need to provide means for resolving this issue. MarkerCount addresses the problem via the following procedure, albeit not completely. Although it was originally devised to fill-out cell types to the rejected cells, it assumes more than one cell populations reside in a cluster and, by using the centroids and covariances of these cell populations within a cluster, two or more cell types can be identified within a cluster. In this way, many-to-one correspondence can be resolved without increasing the clustering resolution too much.

2.6. Reference-based and marker-based operation of MarkerCount

Using the functions described above, the operation of MarkerCount can now be described more succinctly. In the reference-based operation, MarkerCount uses reference data and its annotation to find the best markers for each cell type in the reference. Using these markers, it computes the normalized marker counts and makes an initial prediction of cell types for all the cells in the reference data. As per the initial prediction and the annotated cell type, the rejection thresholds are obtained. The outputs of the training phase consist of marker sets and the rejection threshold for each cell type, which are used for cell type identification in test data.

In the test phase, we first assign cell types to cells whose normalized marker count is above the rejection threshold. Clustering is then performed for the test data, and the distance-based reassignment is applied on a cluster-by-cluster basis. In marker-based mode, on the other hand, we first compute the normalized marker counts for all cells utilizing the existing list of markers. For each cell type in the marker database, bimodal fitting is applied to determine the rejection threshold. One possible problem in the marker-based mode is an uneven number of markers. In this case, cell types with a few markers tend to get higher priority over those with a much larger number of markers. This does not happen in the reference-based mode as we select the same or at least a similar number of markers for each cell type. To handle this problem, we applied the following tricks.

2.7. Resolving uneven numbers of markers

One possible solution is to reselect markers for cell types with a large number of markers. That is, in the first round of cell type assignment, we assign cell types with higher rejection threshold and use the prediction to obtain the score in (1) for all markers and finally reselect markers that have higher scores. This is done only for cell types with a number of markers larger than the desired number, 18, which was determined as the best number in reference-based MarkerCount. This approach, however, solves the problem only partially since there exist cell types having only a few or sometimes only one specific marker. To resolve this problem, we applied penalty weight per cell type according to the number of markers as , where is the number of markers. The penalty weight is multiplied by the normalized marker count before obtaining the rejection threshold. Although these tricks were devised for the case when the existing marker database is used, the best way to avoid such a problem in MarkerCount is to use the same or similar number of markers for each cell type, in which case, the penalty weight will be the same for all the cell types so that it does not affect the MarkerCount performance.

2.8. Dataset and cell type renaming

To properly evaluate and compare performances, we collected eight single cell RNA-seq datasets with manual annotation available. These were four pairs of pancreas [20], [21], peripheral blood [22], [23], lung [24], [25], and tumor [26], [27] datasets, with the latter three containing various immune-related cells. Brief description of the data is summarized in Table 1, with accession numbers. These datasets were chosen since they include cell type annotations. Although some of the datasets contain irrelevant cell types, e.g., cells from mouse and T/Mono doublets in GSE100866, we disregarded these when evaluating identification performance. In lung datasets, ERP114453 contains spleen, esophagus epithelium, and lung parenchyma cells under ischemic conditions, where we used only the last one to cross-evaluate with the other lung dataset, SRP218543. Although lung samples in ERP114453 and SRP218543 were collected for different studies under distinct biological conditions, we still used them, as the majority of cell types are identical. Further, it would be interesting to assess how well reference-based cell-type identifiers work with a reference under different conditions from those in the test data. Except for lung datasets, others were used in the previous work [18] on the development of cell type identification tools.

Table 1.

A summary of datasets used for analysis.

| Data | Reference | Accession | Protocol | Num. of cells total | Num. of Tumor cells | Num. of cell types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas 2K | [20] | GSE84133 | inDrops | 2126 | None | 10 (10) |

| Pancreas 8K | [21] | GSE85241 | CEL-seq2 | 8569 | None | 14 (13) |

| CBMC 8K | [22] | GSE100866 | Drop-seq | 8617 | None | 15 (11) |

| PBMC 68K | [23] | GSE93421 | 10X genomics | 68,579 | None | 11 (6) |

| Lung 29K | [24] | ERP114453 | 10X v2 | 57202* | None | 28 (18) |

| Lung 38K | [25] | SRP218543 | 10X v2 | 114396** | None | 31 (24) |

| Melanoma 5K | [26] | GSE72056 | Smart-seq2 | 4513 | 1251 | 11 (8) |

| HeadNeck 6K | [27] | GSE103322 | Smart-seq2 | 5902 | 2215 | 10 (10) |

The numbers in brackets represent the number of cell types with the renaming we discussed before.

*,** down-sampled by 2 and 3, respectively.

When evaluating the performance of cell type identifiers, we need datasets with the same set of cell populations, hopefully based on the same taxonomy. Unfortunately, however, there exists a debate on the definition of cell types. Not only do the datasets with an available cell type annotation have quite different sets of cell type names, but cell types in marker databases are quite varied with different levels in a taxonomy tree. For example, two tumor datasets and CBMC 8 K used rather broad cell types, such as T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells, while PBMC 68 K used specific types, such as CD8+/CD45RA+ Naive Cytotoxic, CD4+ T Helper2, CD4+/CD45RA+/CD25− Naive T, CD8+ Cytotoxic T, CD4+/CD45RO+ Memory, and CD4+/CD25 T Reg. For the purpose of performance evaluation, we need to rename manual annotation, taking widely accepted taxonomies into account. To this end, we applied different renaming for reference-based and marker-based identifiers. For the former, we renamed the annotation in both reference and test data to a broad type if one of them was annotated using broad cell types. For example, when cross-evaluating blood dataset pair (CBMC 8K and PBMC 68K), we renamed cell types to their corresponding broad cell type, e.g., Naive Cytotoxic, T Helper2, Naive T, Cytotoxic T, Memory T and T Reg were all mapped to one broad type, T cell, to train the models for all the reference-based identifier since CBMC 8K was annotated in broad types.

In marker-based approach, however, we cannot simply do this since the set of cell types in the marker database must also be matched to the datasets. Unfortunately, the two marker databases, Panglao DB and CellMarker DB, have different cell type sets in different levels of the taxonomy tree, e.g., CellMarker DB provides 87 T cell markers along with several specific markers for CD8+, CD4+, and memory T cells, while Panglao DB provides specific cell type names, such as regulatory T cells, Follicular Helper T cell, T Helper cells, and so on. Moreover, these sets of cell types do not match the annotations in datasets. Therefore, in the evaluation of marker-based approaches, we used the set of cell types and their respective list of markers as is when running identifiers. Then, once the cell types are determined (in the cell type names in the marker database used), we renamed the predicted cell types to broad types if necessary.

2.9. Performance criteria

To evaluate performance, we used five performance measures, correct (C), error (E), erroneously assigned (EA), correctly unassigned (CUA), and erroneously unassigned (EUA), similar to criteria in a previous work [18]. These criteria are defined according to (1) whether any valid label was assigned by the identifier or not (i.e., marked as unknown, unclear, or unassigned), (2) whether the assigned label is in the reference or not, and (3) if the label is in the reference cell type, whether the predicted label is the same as the assigned label or not. The detailed definitions of the five measures are as follows:

-

A.

Correct (C) is the portion of cells that have a valid predicted label, one from the reference cell type, and the predicted label is the same as the original assignment.

-

B.

Error (E) is the portion of cells that have a valid predicted label, one from the reference cell type, while the predicted label is different from the original assignment.

-

C.

Erroneously assigned (EA) is the portion of cells that have a valid predicted label, one from the reference cell type, but the original assignment is not in the reference (ideally, the prediction in this case should be “unassigned”).

-

D.

Correctly unassigned (CUA) are cells, whose predicted label is “unassigned”, and the original assignment is not in the reference, e.g., tumor cells.

-

E.

Erroneously unassigned (EUA) are those cells, whose predicted label is “unassigned”, while the original assignment is a valid label existing in the reference, other than “unknown“ or “unassigned”.

Although it is also informative to show precision versus recall, we used these more specific measures to provide better insight into the performance of cell type identifiers.

2.10. Cross-evaluation for the reference-based identification

To show the effectiveness of reference-based cell type identification, we employed cross-evaluation, similar to the cross-validation in statistical/machine learning terminology, i.e., with multiple datasets, one is selected for testing, while others are used as a reference to find cell type markers, and this is repeated by circularly shifting their role in the experiment.

3. Results

For evaluation, we ran MarkerCount in both reference-based and marker-based mode. We compared the obtained results with those yielded via existing reference- [14], [16], [17], [18] and marker-based [9], [10], [11] identifiers using the cell type markers described in [13]. It should be noted that other available software packages for cell type identification include DigitalCellSorter [28], Cell-BLAST [29], scMatch [30], ACTINN [31], SCSA [32], and others, all mentioned in a previous work [19]. However, some of these do not have functions for building custom models via utilizing list of a markers or reference data with annotation. Therefore, we consider only packages which allow one to customize the model with different cell type annotations for reference-based methods or with different lists of markers for marker-based methods.

3.1. Distribution of the primary decision metric: normalized marker count

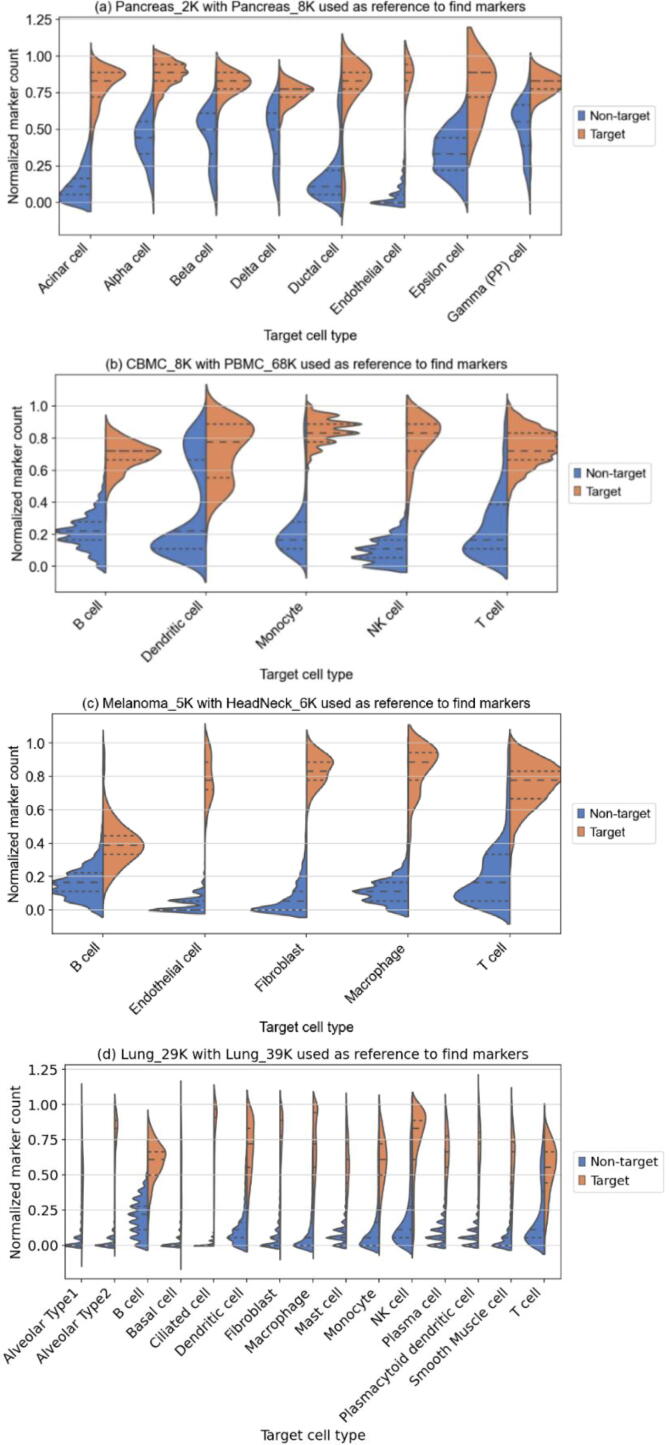

Before performing comparison with existing methods, we first present distribution of the primary decision metric, i.e., the normalized marker counts, in order to obtain deeper insight into the operation of MarkerCount. Fig. 2 shows comparisons between distributions of the normalized marker count for the target cells and the non-target cells in four pairs of single-cell RNA-seq datasets, namely, pancreas, blood, tumor, and lung single-cell data.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of the two distributions of the primary decision metric, that is, the normalized marker counts, for target cells and non-target cells in (a) pancreas, (b) blood (c) tumor, and (d) lung datasets. For many cell types, the target and non-target are largely separable using the normalized marker counts alone. For certain cell types, including beta, delta, epsilon, and gamma cells in the pancreas, dendritic cells in blood and B cells in tumors, as well as T cells in the lung, identification through normalized marker counts alone would yield considerable errors. Taking this into account, MarkerCount sets a rejection threshold for the normalized marker counts conservatively at first and uses cluster-basis cell type reassignment and correction utilizing similarity within a cluster.

Most of the cell populations can be distinguished via the primary metric, while some show large overlap between the two distributions of target cells and non-target cells. In the second violin plot for blood data (b), a large portion of non-dendritic cells have normalized marker counts comparable with those of dendritic cells. These cells were mostly monocytes (based on manual annotation). It can be inferred that they either expressed marker genes of both monocytes and dendritic cells or some of the monocytes subject to manual annotation were actually dendritic cells. Unfortunately, however, we cannot ensure that the latter is true. Regardless of these unclear clusters, we see that most cell types are well clustered in the primary metric and distinguishable from other non-target cell types.

3.2. Reference-based identification

In the reference-based identification, we performed cross-evaluation for each of the four pairs of datasets, i.e., circularly used one as test data and the other as a reference to identify marker genes and to set a rejection threshold on the normalized marker counts. To show the stable performance, we also tested tumor datasets using one of the blood datasets (CBMC 8K or PBMC 68K) as a reference for markers. Note that blood datasets do not contain tumor cells, while there are various tumor cells within the tumor datasets. Ideally, these tumor cells and the cell types not annotated in the reference must be determined as “unknown” or “unassigned”.

Fig. 3 summarizes the results for the five performance criteria mentioned before. The “Ideal” in the first bar is the performance we obtain under the assumption that manual annotation is correct. If correct and the identification is perfect, only C and CUA must exist without any E, EA, and EUA. With imperfect identification, we may have E, EA, and/or EUA, each of which may have different impact depending on the purpose of analysis. Although too much EUA is undesired, E and EA might have a worse impact than EUA in most cases, as one can manually characterize clusters predicted as unknown or unassigned. Roughly speaking, it is desirable that the predicted results are as close to the ideal case (the first bar) as possible. In pancreas, blood, and lung data, there was a very small portion of cells whose type was not in the references while, tumor data contained a large portion of cells that were ideally identified as unknown (or unassigned).

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of the reference-based cell type identification performance between MarkerCount, CHETAH, SingleR, CaSTLe, scmap(cell), and scmap(cluster). (a) Pancreas, (b) peripheral blood (immune system), and (c) tumor tissue. C: Correct, EUA: Erroneously unassigned, E: Error, EA: Erroneously assigned, CUA: Correctly unassigned. The first bar in each figure shows the ideal performance, where CUA accounts for tumor cells and cell types not in the reference. Ideally, these must be predicted as unknown (or unassigned).

For the pancreas and lung data, SingleR performed the best in terms of correct prediction, followed by MarkerCount, scmap(cell), CaSTLe, CHETAH, and scmap (cluster). However, if E and EA are to be as small as possible, scmap(cell), scmap(cluster), or CHETAH perform better than SingleR, MarkerCount, and CaSTLe, even though scmap(cluster) and CHETAH did not assign a cell type for a large portion of cells. In blood data, MarkerCount performed the best in terms of correct prediction. Although scamp(cell) and scmap(cluster) had very small error, their EUAs were too large, and the correct precision was low.

The prediction accuracy in terms of CUA is highlighted in Fig. 3(d) to (f) for tumor datasets with different references. In (e) and (f), we used one of the blood datasets as reference. For all three results, MarkerCount showed the closest pattern to the ideal case with a small portion of E and EA. CHETAH, scmap(cell), and scmap(cluster) yielded less Es than MarkerCount. However, they erroneously assigned most tumor cells to normal cell types. Overall, MarkerCount exhibited better performance than other identification tools for the blood and tumor datasets. Although its performance for pancreas and lung was not the best, it performed reasonably good.

3.3. Marker-based identification

Unlike other reference-based methods, MarkerCount also provides marker-based identification with a slight modification of the test phase. Therefore, we also compared MarkerCount with the existing marker-based methods, including Garnett, SCINA, and scSorter. The marker-based approach requires only lists of cell markers for which we used CellMarker DB [13]. We extracted cell markers for pancreas, lung, blood, and peripheral blood, where the last two were used for the blood datasets and the two tumor datasets. Results for the four pairs of datasets are summarized in Fig. 4. Similar to the comparison of reference-based cell type identifiers, we measured five criteria, namely, C, EUA, E, EA, and CUA. Although scSorter performed slightly better than MarkerCount for pancreas datasets, MarkerCount showed the best performance for all other datasets.

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of the marker-based cell type identification performances of MarkerCount, scSorter, Garnett, and SCINA. (a) Pancreas, (b) peripheral blood, (c) lung, and (d) tumor tissue data from the CellMarker DB. C: Correct, EUA: Erroneously unassigned, E: Error, EA: Erroneously assigned, CUA: Correctly unassigned. The first bar in each figure shows the ideal performance, where CUA accounts for tumor cells and cell types not present in the reference. Ideally, these must be predicted as unknown (or unassigned).

3.4. Precision, recall, and F1 score

The reason we used the five criteria instead of recall and precision (or sensitivity and specificity), is that cell type identification is different from the general classification problem, since we need to identify not only known cell populations (C), but also unknown populations (CUA), where performance in the latter was one of the main advantages of MarkerCount. Although recall and precision are used for binary classification and, in a multinomial case, they are evaluated separately for each class label (cell type), one can define them in a simpler form using the five criteria as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

With these definitions, F1 score can be obtained as: .

Fig. 5 shows comparisons of recall versus precision and the corresponding F1 score of the reference-based methods and the marker-based methods for the four pairs of datasets. In terms of F1 score, MarkerCount was the best in blood and tumor datasets in reference-based mode as well as in blood, lung, and tumor in marker-based mode, confirming its stable performance for various datasets from different tissues and sequencing platforms.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of recall versus precision and F1 scores of reference-based and marker-based methods, respectively. Although MarkerCount is not always the best, it is high-ranked for most of the dataset pairs.

3.5. Qualitative comparison of reference- and marker-based MarkerCount

In Fig. 6, we plotted a Sankey diagram between the manual annotation and the predicted ones for blood and tumor datasets, respectively. A cell population is better identifiable with a larger number of corresponding cells in the reference. Having more cells in the reference data, the corresponding cell type can be well characterized, resulting in a superior set of markers so that one can better identify these cell populations. On the contrary, the identification model for those cell types having a small number of cells in the reference tends to be overfitted to the reference data and may be inappropriate for the test data. Without a doubt, more cells in the reference might lead to better identification performance in most of the reference-based identifiers. The problem of an uneven cell population is inherent. One may combine two or more datasets into one reference set to train the model and improve performance. However, batch effects may compromise this. Most cell type identifiers utilize clustering, and the identification model is fitted on a cluster basis. Problems arise if there are two or more clusters far apart for one cell type due to batch or tissue-specific effects. Another issue to consider is that some cell populations do not have clear cluster boundaries, specifically those from the same progenitors such as monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. As shown in Fig. 6, Fig. 7, some of these cell types were hardly recovered and interchangeably detected. In many cases, they were not well clustered with sufficient separation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Sankey diagram for two datasets analyzed via different reference-based identifiers (two best identifiers for each dataset). Blood data analyzed with (a) MarkerCount and (b) CaSTLe. Tumor data analyzed with (c) MarkerCount and (d) CHETAH. Left side is the manual annotation and right side is the predicted cell types. Those cell types with limited number of cells tend to generate more errors than those with a larger number of cells.

Fig. 7.

A comparison of UMAP plots for tumor (HeadNeck 6K and Melanoma 5K) data analyzed with different reference-based identifiers. (a) Manual annotation, (b) MarkerCount, (c) CHETAH, (d) SingleR, (e) CaSTLe, and (f) scmap(cell). UMAP plots clearly display identification performances. The UMAP plots were computed using a dimension-reduced version of the gene expression matrix.

Compared to the reference-based approach, the marker-based one does not require reference annotation, which is a big advantage compared to the former. However, it highly depends on marker selection, and the best set of markers should be selected taking the specific identification procedures into account. One reason for the high dependency on marker set seems to be the uneven number of cell markers. In the CellMarker database, several subtypes of dendritic cells have hundreds of marker genes while others, e.g., natural killer cells and B cells, have only around ten markers. Such discrepant marker numbers may compromise identification performance, which is why MarkerCount (marker-based mode) reselects markers if too many are provided in marker database. Depending on the specific procedures and algorithm of cell type identifiers, the best set of markers will also be different. “Cell marker” means that it is expressed only in a specific cell type and not expressed at all elsewhere. However, it does not always hold since the definition of cell type can be quite different according to the analytical purpose and application. For example, one application may be required to identify T cells as a whole, while another may be required to identify specific subtypes, such as cytotoxic T cells, memory T cells, helper T cells, and regulatory T cells. Depending on what specific set of cell types are required, different approaches and/or different tools must be used. Fig. 8, Fig. 9 show the Sankey diagram and the UMAP plots similar to those in the reference-based identification experiments. In these figures, we see that specific subtypes are interchangeably identified to other subtypes within the same broader cell type. Having markers of both broad and specific cell types, simultaneous identification of both categories may cause unexpected results, as shown in Fig. 8. As it is also risky to identify specific cell type using only a few markers, a better option is to use hierarchical identification, i.e., identify broad cell types first using many markers and then determine their subtypes using specific markers. The specific hierarchy to be used depends on the specific tissue analyzed.

Fig. 8.

Sankey diagram for tumor and blood datasets with different marker-based identifiers using the CellMarker database. Tumor data analyzed with (a) MarkerCount and (b) SCINA. Blood data analyzed with (c) MarkerCount and (d) scSorter. PBMC 68K analyzed with (e) MarkerCount and (f) Garnett. (a) to (d) were shown in the broad cell types while (e) and (f) were shown in the original cell type names in the manual annotation (left) and the CellMarker database (right). As mentioned, when running marker-based identifiers, we used cell types as provided in the CellMarker database, where makers for specific cell types are provided. After cell types are identified, we renamed the predicted cell types to the respective broad type to evaluate performance. (e) and (f) were shown with the original cell type names in the manual annotation (left) and those in the CellMarker database (right) in order to give insight into the performance for specific cell types.

Fig. 9.

A comparison of UMAP plots for blood (CBMC 8K and PBMC 68K) data with different marker-based identifiers. (a) Manual annotation, (b) MarkerCount, (c) Garnett, and (d) SCINA. The UMAP plots were computed using dimension-reduced version of the gene expression matrix.

4. Discussion

Marker-based and reference-based approaches have their respective advantages and drawbacks. The reference-based approach is useful when annotating new samples with previous annotations at hand. However, since an uneven number of cells for various cell types is inherent, rare cell populations can hardly be identified. Another problem in reference-based identification is the batch effect, especially when the reference is sequenced or processed differently from test data. In our experiments, we had such cases, i.e., in Fig. 3(b), (e) and (f), and we used references obtained via different sequencing technology from test data. Although we employed binarized gene expression in MarkerCount to suppress the batch effect, it is unclear whether the superior performance of MarkerCount in Fig. 3(b), (e), and (f) stems from this feature. Nevertheless, the reference-based MarkerCount exhibited better performance in terms of correct identification of both known and unknown cell types, i.e., both in C and CUA, in most of the experiments we performed. Another advantage of reference-based MarkerCount is that the tool outputs marker genes obtained from the reference data, which can be used to identify new markers for specific cell types of interest.

When using the marker-based approach, cell types and markers must be appropriately defined to obtain a good result. Cell types and taxonomy are not standardized and debating so that researcher should prepare their own list of markers for the specific study and objective. This issue applies to all marker-based approaches, including the marker-based mode of MarkerCount. When using marker-based MarkerCount, it is desired to use the same or similar number of markers for all cell types in order to obtain the best result. In the background experiments for reference-based MarkerCount, we ran MarkerCount with various number of marker genes, and we found that 18 was the optimal number of markers for most of the datasets. Since the marker-based mode uses similar processes to that of the reference-based mode in the test phase, selecting marker genes around this number might yield better results.

Comparing performance between the two approaches, reference-based was superior to marker-based identification. However, this argument cannot be generalized as performance depends on the list of markers (for marker-based) and the reference annotations (for reference-based). In both approaches, one of the key components is clustering and, for proper identification, each cell populations should be well clustered, even though this is not always the case. Although various clustering algorithms, such as partitioning-based, distribution-based, or graph-based clustering, are available, the performance difference between these does not seem not critical. Rather, handling not-clearly-separable sub-populations, such as monocytes, macrophage, and dendritic cells, is a greater issue, which requires further studies in collaboration with experts from different fields of study.

5. Conclusion

MarkerCount exhibited better performance than other tools in identifying both known and unknown cell populations. The latter aspect is especially important when unidentified cell populations, a subpopulation of a known cell type with an unidentified transcriptomic profile, or heterogeneous tumor cells co-existing in a tissue are present. MarkerCount performed best for this purpose. Further, it supports both reference- and marker-based modes for versatile applications and is easily customized with user-defined cell type sets and marker lists or with different annotations for specific study objectives. The reference-based MarkerCount can also be used to identify new markers (by feeding only reference data with manual annotation). Even though this is typically done via differential gene expression analysis, there is a difference between the two approaches. With MarkerCount, the lists of markers are obtained using binarized gene expression, and it provides additional information such as the occurrence frequencies in both target and non-target cell populations, which seems suited for marker identification, since, in the context of cell type identification, “marker” refers to a gene expressed only in a specific cell population, regardless of its expression level. To our best knowledge, no other cell type identifiers provide the above-described functions.

6. Availability of software and datasets

The python code and the example in Jupyter notebook were deposited to Github, available at https://github.com/combio-dku/MarkerCount/tree/master (Project name: MarkerCount, license: GPL 3.0, Operating system(s): Platform independent, Programming language: python 3, other requirement: None). The datasets used in this work can be freely downloaded from the internet: two lung datasets from the human cell atlas, https://www.humancellatlas.org/, and others from the gene expression omnibus https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (GEO). The full codes and datasets for reproducing results are available at figshare and can be downloaded at https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/MarkerCount_cell_type_identification_results/14865918.

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2020R1F1A1066320 and NRF-2021R1A4A5032463).

Authors’ contribution

HK and SY devised the concept and key idea. SY and HK developed the python code of MarkerCount. HK and JL performed experiments. SY guided experiments and data analysis. KK provided interpretation and feedback on the results. All authors wrote, read, and approved the final manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

HanByeol Kim: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Joongho Lee: Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation. Keunsoo Kang: Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Seokhyun Yoon: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Tang F., et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):377–382. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picelli S., et al. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10(11):1096–1098. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolodziejczyk A.A., et al. The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Cell. 2015;58(4):610–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung W., et al. Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15081. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satija R., et al. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lun A.T., McCarthy D.J., Marioni J.C. A step-by-step workflow for low-level analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data with Bioconductor. F1000Res. 2016;5:2122. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9501.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiselev V.Y., et al. SC3: consensus clustering of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Methods. 2017;14(5):483–486. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf F.A., Angerer P., Theis F.J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pliner H.A., Shendure J., Trapnell C. Supervised classification enables rapid annotation of cell atlases. Nat Methods. 2019;16(10):983–986. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0535-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z., SCINA, et al. A semi-supervised subtyping algorithm of single cells and bulk samples. Genes (Basel) 2019;10(7) doi: 10.3390/genes10070531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo H., Li J. scSorter: assigning cells to known cell types according to marker genes. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02281-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzen O, Gan LM, Bjorkegren JLM, PanglaoDB: a web server for exploration of mouse and human single-cell RNA sequencing data. Database (Oxford), 2019. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhang X., et al. Cell Marker: a manually curated resource of cell markers in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D721–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aran D., et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(2):163–172. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alquicira-Hernandez J., et al. scPred: accurate supervised method for cell-type classification from single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1862-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiselev V.Y., Yiu A., Hemberg M. scmap: projection of single-cell RNA-seq data across data sets. Nat Methods. 2018;15(5):359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieberman Y., Rokach L., Shay T. CaSTLe - Classification of single cells by transfer learning: Harnessing the power of publicly available single cell RNA sequencing experiments to annotate new experiments. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Kanter J.K., et al. CHETAH: a selective, hierarchical cell type identification method for single-cell RNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(16) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdelaal T., et al. A comparison of automatic cell identification methods for single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1795-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muraro M.J., et al. A single-cell transcriptome atlas of the human pancreas. Cell Syst. 2016;3(4):385–394 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron M., et al. A single-cell transcriptomic map of the human and mouse pancreas reveals inter- and intra-cell population structure. Cell Syst. 2016;3(4):346–360 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoeckius M., et al. Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat Methods. 2017;14(9):865–868. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng G.X., et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14049. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madissoon E., et al. scRNA-seq assessment of the human lung, spleen, and esophagus tissue stability after cold preservation. Genome Biol. 2019;21(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1906-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reyfman P.A., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1517–1536. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tirosh I., et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352(6282):189–196. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puram S.V., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor ecosystems in head and neck cancer. Cell. 2017;171(7):1611–1624 e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domanskyi S., et al. Polled Digital Cell Sorter (p-DCS): Automatic identification of hematological cell types from single cell RNA-sequencing clusters. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20(1):369. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2951-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Z.J., et al. Searching large-scale scRNA-seq databases via unbiased cell embedding with Cell BLAST. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3458. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17281-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou R., Denisenko E., Forrest A.R.R. scMatch: a single-cell gene expression profile annotation tool using reference datasets. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(22):4688–4695. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma F., Pellegrini M. ACTINN: automated identification of cell types in single cell RNA sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(2):533–538. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao Y., Wang X., Peng G. SCSA: A cell type annotation tool for single-cell RNA-seq data. Front Genet. 2020;11:490. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]