Abstract

Study Objectives:

Clinical and population health recommendations are derived from studies that include self-report. Differences in question wording and response scales may significantly affect responses. We conducted a methodological review assessing variation in event definition(s), context (i.e., work- versus free-day), and timeframe (e.g., “in the past 4 weeks”) of sleep timing/duration questions.

Methods:

We queried databases of sleep, medicine, epidemiology, and psychology for survey-based studies and/or publications with sleep duration/timing questions. The text of these questions was thematically analyzed.

Results:

We identified 53 surveys with sample sizes ranging from 93 to 1,185,106. For sleep duration, participants reported nocturnal sleep (24/44), sleep in the past 24-hours (14/44), their major sleep episode (3/44), or answered unaided (3/44). For bedtime, participants reported time into bed (19/47), first attempt to sleep (16/40), or fall-asleep time (12/47). For wake-time, participants reported wake-up time (30/43), the time they “get up” (7/43), or their out-of-bed time (6/43). Context guidance appeared in 18/44 major sleep duration, 35/47 bedtime, and 34/43 wake-time questions. Timeframe was provided in 8/44 major sleep episode duration, 16/47 bedtime, and 10/43 wake-time questions. One question queried the method of awakening (e.g., by alarm clock), 18 questions assessed sleep latency, and 12 measured napping.

Conclusion:

There is variability in the event definition(s), context, and timeframe of questions relating to sleep. This work informs efforts at data harmonization for meta-analyses, provides options for question wording, and identifies questions for future surveys.

Keywords: Sleep research, survey research, research methods, sleep assessment, circadian rhythm

1. Introduction

Public health recommendations for sleep duration and timing usually rely partially on self-reported data [1], [2]. There are multiple potential limitations of self-reported data, including information and recall biases, and inaccuracies in calculating intervals (e.g., between sleep onset and wakening) or estimating times (e.g., length of time to fall asleep); all of these can vary by demographic factors and health conditions [3], including sleep disorders such as insomnia [4]. The specific wording used to collect information about sleep timing and duration also affects responses: for example, asking for sleep duration directly (e.g., “How many hours did you sleep last night?”) versus indirectly (i.e., asking for sleep and wake clock times) may produce different values of sleep duration [5]. Week-to-week and night-to-night variability in sleep parameters, if not assessed in the question wording, may also pose a challenge to accurate reporting of these metrics.[6] Sleep is a multi-dimensional construct, with duration and timing as key components [7]. In this paper, we focus on documenting variation in self-reported questions assessing sleep duration and timing.

Survey designers interested in measuring sleep domains must carefully balance several factors as they develop or select self-reported sleep duration and/or timing questions for surveys and diaries. First, designers must consider event definition(s). For example, bedtime may be assessed by asking a participant to report when they “go to bed” or, alternatively, when they “fall asleep.” If a participant goes to bed but then reads or watches television before initiating sleep, asking this individual when they “go to bed” and using this as the marker of sleep onset will overestimate sleep duration. On the other hand, individuals may have difficulty knowing the precise time they fall asleep, and their perceived sleep quality might bias such responses. Second, designers must consider context. Sleep timing and duration have been shown to vary significantly between work/school and free days [8], [9], so it is optimal to capture context with separate questions where possible. Third, survey designers must consider timeframe. Whereas some surveys may ask participants to report sleep duration and/or timing on a “typical night,” others ask for sleep duration and/or timing in a specified timeframe (e.g., “in the past 4 weeks”). Responses may not be comparable between study participants who may consider different reference periods as they make their response. Finally, the survey designer must balance the detail/depth of information sought with other survey constraints (e.g., the number of questions asked may influence survey completion rate). Therefore, considering the potential effects of variations in event definition(s), timeframe, and context of questions is critical in queries on sleep duration and timing.

We conducted a methodological review to document the variation in event definition(s), context (i.e., work-versus free-day), and timeframe of sleep timing and duration questions. Goals of this work were to identify the prevailing approaches to self-reported sleep duration and/or timing questions; to document the variation in event definition(s), context, and timeframe across questions that collect information on sleep duration and timing; consider the implications of these question text variations; and to highlight options for survey and diary designers to consider. This work should support future efforts to standardize questions pertaining to sleep duration and timing and thus enable meta-analyses across studies to improve understanding of sleep’s role in health and safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying sources

We conducted a methodological review of questions measuring sleep duration and timing in adults. Methodological studies report on the design, conduct, analyses, or reporting of primary or secondary research [10]. With the help of a medical librarian, the lead author (RR) developed a search strategy for the present study that aimed to identify all available literature that used surveys or questionnaires to measure sleep duration and/or timing (detailed in Appendix). With regard to sleep duration, we were interested in both questions that measured sleep duration directly (e.g., “How many hours do you typically sleep on a free night?”) and questions that are pertinent to the measure of sleep duration, including sleep latency (e.g., “Approximately how long does it take you to fall sleep”). Sleep latency was included in this methodological review of sleep duration as some researchers choose to ask participants the time they go to bed, which may not be the time they start sleeping. Therefore, assessing sleep latency is important in some cases for ascertaining a precise estimate of sleep duration. We also reviewed nap questions because some researchers may be interested in 24-hour sleep, which would include nap episodes.

The search resulted in over 6,000 published articles in a single search engine (i.e., PubMed). When the number of articles is sufficiently large, as is the case in our study, a sample can be expected to provide comparable results to a review including all available articles [10]. Therefore, to identify a sufficiently large set of articles for the present review, we (i) identified databases and repositories managed by organizations in sleep, medicine, epidemiology, and psychology that maintain lists of sleep duration and/or timing questionnaires and studies that have employed such instruments; (ii) reviewed a textbook of sleep questionnaires; and (iii) used other publications known by the authors. We downloaded and then qualitatively analyzed and categorized the relevant questions from these sources and their wording.

2.2. Identifying relevant sleep duration and/or timing question

We identified six databases or repositories that include sleep, medicine, epidemiology, and psychology disciplines, and were managed by academic or professional institutions (details and links in Appendix): the Sleep Research Society (SRS); the National Sleep Research Resource (NSRR); the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan (ICSPR); the American Psychological Association Health and Psychological Instruments (HAPI); the American Thoracic Society (ATS); and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

For each database or repository, we searched for studies with questions measuring sleep duration and timing. ICSPR, ATS, and HAPI had search tools that we used to identify relevant studies; we used the following search term to identify relevant studies: “sleep,” “sleep duration,” “sleep timing,” “bedtime,” “wake time,” “bed,” “wake,” “woke up,” “alarm clock,” “asleep,” and “nap.” For databases without a search tool, each study in the database was individually reviewed for relevant sleep-related questions by RR and MFW.

The studies identified using the above procedures were cross-referenced in two additional steps to ensure our list was comprehensive. First, RR and MFW reviewed a textbook containing more than 100 sleep surveys for sleep duration and timing questions and included appropriate surveys from this source [11]. Second, an expert team (EBK, CAC, SFQ, SR, LKB) reviewed the list of studies that emerged from all the above steps and identified additional missing studies that were added to our review.

2.3. Coding

Coding the set of questions proceeded in two broad phases: (1) eligibility screening and (2) coding the questions for event definition(s), context, and timeframe cues.

To assess eligibility, the exact text of questions assessing sleep duration and timing from each study were extracted and reviewed by two independent coders (RR and MFW). First, the coders searched questions for eligibility in one of the broad sleep duration and timing domains including: sleep duration; bedtimes; wake times and/or method of waking; sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep); and naps. The coders removed questions that measured domains that did not specifically pertain to the duration or timing of sleep (e.g., about sleep quality or sleep difficulty); questions asking individuals for their preferred amount of sleep as opposed to their actual sleep; and questions that asked participants to report the number of hours of sleep after which they are able to wake up and feel refreshed. Finally, surveys that targeted children and adolescents or were not in English were removed. If two studies used the same wording, both references were retained. There were no discrepancies among coders on eligibility criteria.

After ensuring eligibility, the coders worked independently to code the question wording in a series of iterative steps informed by the constant comparative method of qualitative inquiry [12]. In the first step, the coders independently reviewed a random set of 20 questions. The coders met to discuss a preliminary codebook, which detailed the sleep duration and timing domains (i.e., sleep duration; sleep timing; sleep latency; and naps) and sub-domains (e.g., distinguishing within sleep duration between 24-hour sleep, nocturnal, and major sleep episode). The preliminary codebook was reviewed by the full author team. After approval from the full author team, the coders proceeded to code 20 questions at a time, compare their codes, then code another 20 questions until all questions were coded.

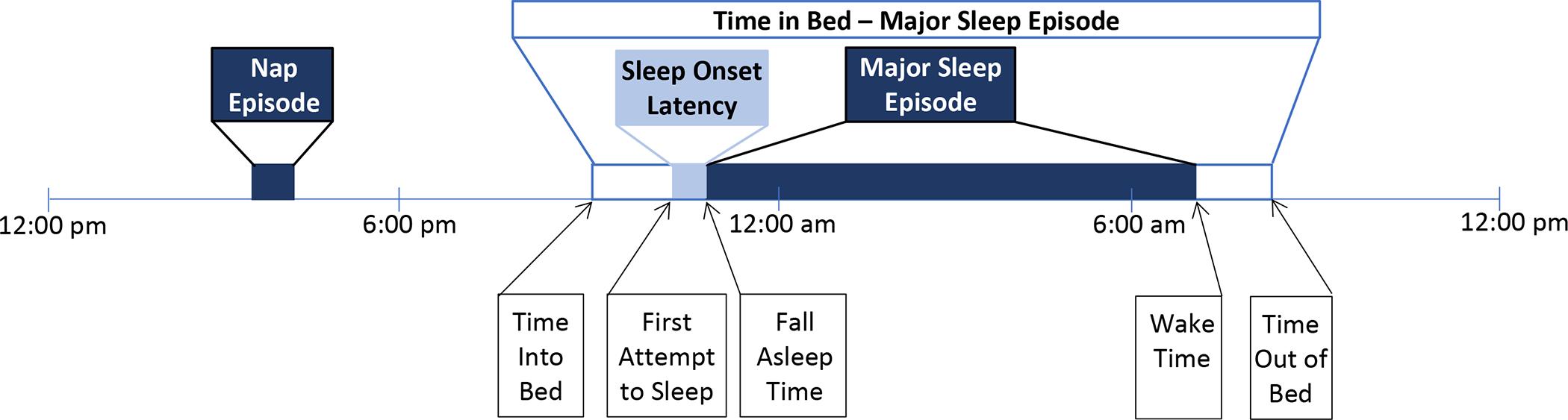

For sleep duration, we were interested in questions assessing total sleep across the 24-hour day, nocturnal sleep, and/or the major sleep episode (i.e., the longest period of time after falling asleep until the time sleep ends and the person chooses to remain awake); questions assessing naps or periods of sleep that were less than four hours; and questions assessing sleep latency. For sleep timing, we were interested in questions assessing bedtimes, wake times, and sleep latency. Question text of “what time do you go to bed” and “what time do you get out of bed,” was classified as time in bed while text of “what time did you fall asleep” and “what time did you wake up” was classified as the major sleep episode (Figure 1) [13].

Figure 1: A graphical display of terminology used in this report for measuring sleep duration and sleep timing.

Notes.

Items in black font refer to event times (e.g., time into bed) while items in blue font refer to durations (dark blue: sleep onset latency; light blue: sleep durations or time spent with the intention to sleep).

The diagram represents a sleep schedule with a nap lasting approximately 45 minutes at approximately 3:30pm, first attempt to sleep at approximately 10:30pm and a fall asleep time of 10:45pm. This schedule also outlines a wake time of approximately 7:00am and a time out of bed at approximately 7:30am.

This review distinguishes between studies with different “event definitions” of sleep, such as nocturnal and 24-hour sleep. For instance, a researcher interested in capturing 24-hour sleep may combine nap and major sleep episode durations.

Coders first separated all the questions into the above-detailed sleep domains, then applied appropriate codes to summarize the approaches (i.e., event definition, context, timeframe) taken in each question. For event definitions, coders identified content present in the questions that directed the participant and were supplemental to the clear, primary purpose of the question. For example, “How many hours of sleep do you get?” would not be coded as featuring additional event definition(s), whereas the question “How many hours of sleep do you get at night (this may be different than the time you spend in bed)?” would be coded as featuring additional event definition (e.g., detail to subtract time in bed not sleeping). For context, coders identified questions that asked participants to distinguish between work- and free-day sleep duration and sleep timing-related responses. Questions that provided any context cues would be categorized as distinguishing between work- and free-day sleep duration and/or timing. For example, some surveys only ask one question about sleep duration on weekdays, which would be categorized as representing context cues. Finally, coders identified questions that provided participants with guidance on the timeframe they should report on their sleep. For example, the question “In the past 4 weeks, how many hours have you slept at night?” provides participants with timeframe input to guide their sleep duration and/or timing response. The codebook in included in Supplemental Information. The exact wording of all questions coded is included in Tables 2–5. Results of the coding procedure are reported by domain. In each section summarizing the questions by domain, we report the number of questions that featured the various event definitions, context cues, and timeframe considerations out of the total number of questions in each domain.

Table 2.

Sleep duration questions

| Category | Study | Question Wording [Response Scale] | Event Definition | Context | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-hour sleep | American Time Use Survey: Arts Activities | How long did you spend? -Sleeping (The length of time a respondent spent on an activity, during a specified 24 hour period) [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | I would like to ask you a few questions about your sleep patterns. On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? Think about the time you actually spend sleeping or napping, not just the amount of sleep you think you should get. | Include naps | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa [HAALSI] | Over the past 4 weeks, how many hours do you think you actually slept each day? This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed. | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past 4 weeks | |

| 24-hour sleep | National Health Interview Study (NHIS) | On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 1) National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) |

Since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, how much time did you spend sleeping? [HH:MM] | Since time spoke yesterday | ||

| 24-hour sleep | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) Parent Study | How many hours of sleep do you typically get each day? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

On workday or weekdays, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one day?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Workday or weekday | |

| 24-hour sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

On weekends or non-workdays, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one day?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Weekend or non-workday | |

| 24-hour sleep | Nurse’s Health Study | On average, over a 24-hour period, do you sleep: [<5 hours; hrs; 6 hrs; 7 hrs; 8 hrs; 9 hrs; 10+ hours] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, PSED I | For the last typical day off, please indicate how much time (within a quarter of an hour) was devoted to each daily activity: Sleeping [HH:MM] | Day off | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, PSED I | For the last typical work day, please indicate how much time (within a quarter of an hour) was devoted to each daily activity: Sleeping. [HH:MM] | Work day | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Sinai Community Health Survey | I would like to ask you about your sleep pattern. On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | UK Biobank | About how many hours sleep do you get in every 24 hours? (please include naps) [HH:MM] | Include naps | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Cleveland Family Study (CFS) | How many total hours of actual sleep do you get in a 24-hour period (including naps)? [5 hours or less; 6 to 6.9 hours; 7 to 7.9 hours; 8 to 8.9 hours; 9 to 9.9 hours; 10 to 10.9 hours; 11+ hours] | Include naps | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | How many hours of sleep do you usually get at night on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Weekday or workday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | How many hours of sleep do you usually get at night on weekends or your non-work days? [HH] | Weekend or non-work day | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | How many hours do you usually sleep per night? I sleep [HH] hours per night | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Cancer Prevention Study I | How many hours of sleep do you usually get a night? [HH:MM] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Cancer Prevention Study II | On the average, how many hours do you sleep each night? [HH:MM] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey | On average, how many hours of sleep do you usually get on a typical weeknight. [HH:MM] | Weeknight | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey | On average, how many hours of sleep do you usually get on a typical weekend. [HH:MM] | Weekend | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Medical outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) | On average how many hours did you sleep each night during the past 4 weeks? [HH:MM] | Past 4 weeks | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Mexican National Halfway Health and Nutrition Survey | In general, how many hours do you sleep daily during the night from Monday to Friday?” [HH] | Monday to Friday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | MrOS Sleep Study (MrOS) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get each night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed.)” [HH:MM] | Exclude non-sleep time | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | How much sleep usually get at night on weekdays or workdays? [HH:MM] | Weekday or workday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2003 Sleep and Aging |

On a weekday, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Weekday | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits and Styles |

On days you do not work or on weekends, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Not work or weekend | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain | On work nights or weeknights? [HH:MM] | Work or week nights | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

On non-work nights or weekend nights? [HH:MM] | Not work or weekend night | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

On school nights/worknights or weeknights, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | School nights/worknights or weeknights | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

On non-school nights/nights you do not work or weekend nights, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Non-school nights/nights you do not work or weekend nights | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed.) [HH:MM] | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Sleep Disorders Questionnaire | How many hours of sleep do you get at night, not including time spent awake in bed? | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Study of Osteoporotic Fracture | On most nights, how many hours do you sleep each night? [HH:MM, rounded to the nearest 30 minutes] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed.) [HH:MM] | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2): Biomarker Project, 2013–2014 | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed.) | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation – 2011 Sleep and Technology |

How many hours not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Women’s Health Initiative | About how many hours of sleep did you get on a typical night during the past 4 weeks? [5 or less; 6 hours; 7 hours; 8 hours; 9 hours; 10 or more hours] | Past 4 weeks | ||

| Major sleep episode | Framingham Heart Study | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or work days? [HH:MM] | Work or weeknights | ||

| Major sleep episode | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Weekdays or workdays | ||

| Major sleep episode | Jackson Heart Study | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Work days | ||

| Not specified | Family Exchanges Study Wave 2, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | How many hours a night do you typically sleep? [HH:MM] | |||

| Not specified | Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) | Hours of sleep ___ [HH:MM] | |||

| Not specified | SLEEP-50 | I sleep __ hours, mostly __ to ___. [HH] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | American Time Use Survey: Arts Activities | How long did you spend? -Sleeping (The length of time a respondent spent on an activity, during a specified 24 hour period) [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | I would like to ask you a few questions about your sleep patterns. On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? Think about the time you actually spend sleeping or napping, not just the amount of sleep you think you should get. | Include naps | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa [HAALSI] | Over the past 4 weeks, how many hours do you think you actually slept each day? This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed. | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past 4 weeks | |

| 24-hour sleep | National Health Interview Study (NHIS) | On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 1) National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) |

Since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, how much time did you spend sleeping? [HH:MM] | Since time spoke yesterday | ||

| 24-hour sleep | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) Parent Study | How many hours of sleep do you typically get each day? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

On workday or weekdays, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one day?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Workday or weekday | |

| 24-hour sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

On weekends or non-workdays, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one day?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Weekend or non-workday | |

| 24-hour sleep | Nurse’s Health Study | On average, over a 24-hour period, do you sleep: [<5 hours; hrs; 6 hrs; 7 hrs; 8 hrs; 9 hrs; 10+ hours] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, PSED I | For the last typical day off, please indicate how much time (within a quarter of an hour) was devoted to each daily activity: Sleeping [HH:MM] | Day off | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, PSED I | For the last typical work day, please indicate how much time (within a quarter of an hour) was devoted to each daily activity: Sleeping. [HH:MM] | Work day | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Sinai Community Health Survey | I would like to ask you about your sleep pattern. On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | UK Biobank | About how many hours sleep do you get in every 24 hours? (please include naps) [HH:MM] | Include naps | ||

| 24-hour sleep | Cleveland Family Study (CFS) | How many total hours of actual sleep do you get in a 24-hour period (including naps)? [5 hours or less; 6 to 6.9 hours; 7 to 7.9 hours; 8 to 8.9 hours; 9 to 9.9 hours; 10 to 10.9 hours; 11+ hours] | Include naps | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | How many hours of sleep do you usually get at night on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Weekday or workday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | How many hours of sleep do you usually get at night on weekends or your non-work days? [HH] | Weekend or non-work day | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | How many hours do you usually sleep per night? I sleep [HH] hours per night | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Cancer Prevention Study I | How many hours of sleep do you usually get a night? [HH:MM] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Cancer Prevention Study II | On the average, how many hours do you sleep each night? [HH:MM] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey | On average, how many hours of sleep do you usually get on a typical weeknight. [HH:MM] | Weeknight | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey | On average, how many hours of sleep do you usually get on a typical weekend. [HH:MM] | Weekend | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Medical outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) | On average how many hours did you sleep each night during the past 4 weeks? [HH:MM] | Past 4 weeks | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Mexican National Halfway Health and Nutrition Survey | In general, how many hours do you sleep daily during the night from Monday to Friday?” [HH] | Monday to Friday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | MrOS Sleep Study (MrOS) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get each night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed.)” [HH:MM] | Exclude non-sleep time | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | How much sleep usually get at night on weekdays or workdays? [HH:MM] | Weekday or workday | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2003 Sleep and Aging |

On a weekday, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Weekday | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits and Styles |

On days you do not work or on weekends, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night?” [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Not work or weekend | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

On work nights or weeknights? [HH:MM] | Work or week nights | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

On non-work nights or weekend nights? [HH:MM] | Not work or weekend night | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

On school nights/worknights or weeknights, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | School nights/worknights or weeknights | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

On non-school nights/nights you do not work or weekend nights, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | Non-school nights/nights you do not work or weekend nights | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spent in bed.) [HH:MM] | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Sleep Disorders Questionnaire | How many hours of sleep do you get at night, not including time spent awake in bed? | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Study of Osteoporotic Fracture | On most nights, how many hours do you sleep each night? [HH:MM, rounded to the nearest 30 minutes] | |||

| Nocturnal sleep | Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed.) [HH:MM] | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2): Biomarker Project, 2013–2014 | During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed.) | Exclude time in bed not sleeping | Past month | |

| Nocturnal sleep | National Sleep Foundation – 2011 Sleep and Technology |

How many hours not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night? [HH:MM] | Exclude naps | ||

| Nocturnal sleep | Women’s Health Initiative | About how many hours of sleep did you get on a typical night during the past 4 weeks? [5 or less; 6 hours; 7 hours; 8 hours; 9 hours; 10 or more hours] | Past 4 weeks | ||

| Major sleep episode | Framingham Heart Study | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or work days? [HH:MM] | Work or weeknights | ||

| Major sleep episode | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Weekdays or workdays | ||

| Major sleep episode | Jackson Heart Study | How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or workdays? [HH] | Work days | ||

| Not specified | Family Exchanges Study Wave 2, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | How many hours a night do you typically sleep? [HH:MM] | |||

| Not specified | Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) | Hours of sleep ___ [HH:MM] | |||

| Not specified | SLEEP-50 | I sleep __ hours, mostly __ to ___. [HH] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | American Time Use Survey: Arts Activities | How long did you spend? -Sleeping (The length of time a respondent spent on an activity, during a specified 24 hour period) [HH:MM] | |||

| 24-hour sleep | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | I would like to ask you a few questions about your sleep patterns. On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period? Think about the time you actually spend sleeping or napping, not just the amount of sleep you think you should get. | Include naps |

Notes: A blank cell indicates that this component is not present in the question.

Table 5.

Napping Questions

| Category | Study | Question Wording [Response Scale] | Event Definition | Context | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naps | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos | During a usual week, how many times do you nap for 5 minutes or more? [none; 1 or 2 times; 3 or 4 times; 5 or more times] | Nap frequency (defined as 5 mins) | Usual week | |

| Naps | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | During the past week, on how many days did you nap for 5 minutes or more? [never; 1 or 2 days; 3 or 4 days; 5 or more days] | Nap frequency (defined as 5 mins) | Past week | |

| Naps | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | During the past week, on how many days did you nap for an hour or two? [never; 1 or 2 days; 3 or 4 days; 5 or more days] | Nap frequency (defined as 1–2 hours) | Past week | |

| Naps | Sleep Disorders Questionnaire | How many daytime naps (asleep for 5 minutes or more) do you take on an average working day? [1.) None 2.) One 3.) Two 4.) Three or four 5.) Five or more] | Nap frequency minutes (defined as 5 minutes or longer) | Working day | |

| Naps | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | How often do you sleep naps at daytime? [1: never or less than once per week; 2: less than once per week; 3: on 1–2 days per week; 4: on 3–5 days per week; 5: daily or almost daily] | Frequency of any nap | Per week | |

| Naps | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | If you sleep a nap, how long does it last for? My naps usually last for about [HH:MM] | Duration of nap | ||

| Naps | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | How often do you “make time” in your schedule for a regular nap or “siesta” in the afternoon? [Never or rarely; Sometimes; Often; Every day or almost every day] | Frequency of any nap | ||

| Naps | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | When you do nap in the afternoon, how long do you sleep? [HH:MM] | Duration of nap | ||

| Naps | Study of Osteoporotic Fracture | Do you take naps regularly? [Yes; No; Don’t know] | Frequency of any nap | ||

| Naps | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | How many days per week do you usually nap? [___] | Frequency of any nap.................................................................... | Per week | |

| Naps | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | On average, how many hours do you nap each time? [a) Less than 1 hour; b) At least 1 hour but no more than 2 hours; c) More than 2 hours] | Duration of nap | ||

| Naps | Women’s Health Initiative | Did you nap during the day? [Yes; No] | Frequency of any nap |

Notes: A blank cell indicates that this component is not present in the question. The sentence case (e.g., all capitals) is displayed as represented on the survey.

After coding of questions was complete, the author team of LKB, SFQ, CAC, SR and EBK, who are expert sleep researchers and clinicians with extensive experience in sleep research and clinical practice, held two round table discussions to develop a set of considerations for future research and a set of recommendations for future researchers and survey designers. The discussion began with an initial conversation about the key findings from the present study. The coders took notes during the discussion, then prepared a document summarizing the round table discussion. The experts critiqued the document, reviewed each other’s comments, and then agreed upon the final set of considerations.

3. Results

Our search yielded 53 studies assessing sleep duration and/or timing. Sample sizes of the studies ranged from 93 to 1,185,106 [14]. Approximately one third of studies in our sample (37%) measured only one of the five identified domains, 21% measured 2 domains, 31% measured 3 domains, 12% measured 4 domains, and 2% of studies measured all five domains (Table 1). One hundred and sixty-four unique questions were identified.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sleep timing and duration questions in each of the reviewed surveys.

| Survey/Study | Sample Size | Number of Questions per Domain | Total Domains Assessed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Duration†‡ | Bedtime† | Wake time† | Sleep Latency† | Nap† | |||

| American Time Use Survey: Arts Activities[15] | 191,558 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES)[16] | 1,204 | 2N:W/F | 2W/F | 2W/F | 3 | ||

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)[17] | 350,000 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ)[18] | 2,202 | 1N | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2 | 5 |

| Biennial Media Consumption Survey[19] | 3,002 | 1W/F | 1 | ||||

| Cancer Prevention Study I[20] | 1,051,038 | 1N | 1 | ||||

| Cancer Prevention Study II[14] | 1,185,106 | 1N | 1 | ||||

| CBS News Monthly Poll[21] | 1214 | 1W/F | 1 | ||||

| Cleveland Family Study (CFS)[22] | 735 | 124h | 2W/F | 2W/F | 3 | ||

| Family Exchanges Study Wave 2, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 1,734 | 1U | 1W/F | 1 | 3 | ||

| Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study | 1,945 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2 | |||

| Food Attitudes and Behavior Survey[23] | 3,397 | 2 N:W/F | 1 | ||||

| Framingham Heart Study | 14,000 | 1M:W/F | 1 | 2 | |||

| Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa | 6,281 | 124h | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Health Interview Survey, 2020[24] | 116,000 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| HeartBEAT (Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment) Study[25] | 281 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2 | |||

| Hispanic Community Health Study[26] | 16,000 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 1 | 3 | ||

| Jackson Heart Study[27| | 5,306 | 1M | 1 | 2 | |||

| Korean General Social Survey (KGSS)[28] | 2,000 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Mexican National Halfway Health and Nutrition Survey[29] | 11,653 | 1N:W/F | 1 | ||||

| Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) | 551 | 1N | 1 | 2 | |||

| Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE)[30] | 1,031 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ)[31] | 500 | 2 W/F | 2W/F | 3W/F | 3 | ||

| MrOS Sleep Study[32] | 2,911 | 1N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | 2,237 | 1M | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)[33] | 10,122 | 2N:W/F | 2W/F | 2W/F | 1 | 4 | |

| National Health Interview Study (NHIS)[24] | 26,000 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) Parent Study[34] | 1300 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits[35] | 1,010 | 224h:W/F | 2W/F | 2 W/F | 3 | ||

| National Sleep Foundation: 2003 Sleep and Aging[36] | 1,506 | 1N:W/F | 1W/F | 2 | |||

| National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits [37] | 1,506 | 1 N:W/F | 1W/F | 1W/F | 1 | 4 | |

| National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology[38] | 1,508 | 2N:W/F | 1W/F | 1W/F | 3 | ||

| National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain[39] | 1,029 | 2 N:W/F | 2W/F | 2W/F | 3 | ||

| National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: Wave 2 and Partner Data Collection[40] | 3,377 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2 | 3 | ||

| Nurse’s Health Study[41] | 280,000 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, PSED I[42] | 1,261 | 2 24h:W/F | 1 | ||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[43] | 148 | 1N | 1 W/F | 1W/F | 1 | 4 | |

| Sinai Community Health Survey[44] | 1,699 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| SLEEP-50[45] | 699 | 1U | 1 | ||||

| Sleep Disorders Questionnaire (SDQ)[46] | 519 | 1N | 1W/F | 2 | |||

| Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS)[47] | 4,080 | 1U | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS)[48] | 131 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y)[48] | 131 | 4W/F | 4W/F | 2W//F | |||

| Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ)[49] | 257 | 6W/F | 6W/F | 1 | 3 | ||

| St. Mary’s Hospital Sleep Questionnair[50] | 93 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 1 | 3 | ||

| Study of Osteoporotic Fracture (SOF)[51] | 9,704 | 124h | 3 | 2 | |||

| Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN)[52] | 2,679 | 1N | 1W/F | 1 | 3 | ||

| Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2)[53] | 382 | 1N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| The Common Cold Project[54] | 1,415 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Twin Cities Metropolitan Area 2000 Travel Behavior Inventory | 3,890 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| UK Biobank[55] | 500,000 | 124h | 1 | ||||

| uMCTQ[56] | 213 | 2W/F | 2W/F | 2 | |||

| Women’s Health Initiative[57] | 161,809 | 1N | 1 | 2 | |||

Notes:

In the sleep duration column, superscript is used to distinguish between survey questions that measured 24-hour sleep (24h), a nocturnal sleep episode (N), the major sleep episode (M), or not specified (U).

In all sleep domain columns, superscript is used to distinguish between survey questions that differentiated sleep duration and timing factors between work and free days (W/F). If these context cues are not present, there is no superscript notation.

Blank indicates that the component was not present in the survey.

For annual surveys, the sample reported is the most recent year of data collection.

All sample sizes are those reported in the published studies describing the methods or primary results of the study.

3.1. Sleep Duration (Table 2)

We identified 44 questions assessing sleep duration. We distinguish between questions that measured nocturnal sleep (e.g., “How many hours do you usually sleep per night?”), 24-hour sleep duration (e.g., “On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period?”) and major sleep episode (e.g., “How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period)?”). Among the 44 questions measuring sleep duration, 24 questions asked participants to report nocturnal sleep, 14 questions asked participants to report their sleep in the past 24 hours, three questions asked participants to report their major sleep episode, while three questions were unclear or unspecified (e.g., “I sleep __ hours”).

Sixteen duration questions provided respondents with event definition details. Specifically, 3 questions asked participants to include naps in their sleep duration responses (e.g., United Kingdom, UK, Biobank: “About how many hours sleep do you get in every 24 hours? Please include naps”) [55], while 7 questions asked participants not to include naps (e.g., National Sleep Foundation 2003 Sleep and Aging Survey: “On a weekday, how many hours, not including naps, do you usually sleep during one night?”) [36], and 6 surveys asked participants to subtract time spent in bed not sleeping from sleep duration calculations (e.g., the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire: “How many hours of sleep do you get at night, not including time spent awake in bed?”) [46].

Among the sleep duration questions, 18 asked participants to distinguish between work- and free-day sleep (e.g., Framingham Heart Study: How much sleep do you usually get at night (or your main sleep period) on weekdays or work days?”)[58] and 8 questions asked participants to report their sleep in a specific timeframe (e.g., the Medical outcomes Study Sleep Scale: “On average how many hours did you sleep each night during the past 4 weeks?”) [59].

3.2. Bedtime and Wake Time and/or Method of Waking (Table 3)

Table 3.

Sleep timing questions

| Category | Study | Question Wording [Response Scale] | Event Definition | Context | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedtime | Cleveland Family Study | During the PAST MONTH, what TIME (on average) have you gone to bed on weekdays (first closed eyes in attempt to fall asleep)” [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekday | Past month |

| Bedtime | Cleveland Family Study | During the PAST MONTH, what TIME (on average) have you gone to bed on weekends (first closed eyes in attempt to fall asleep)” [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekend | Past month |

| Bedtime | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | What time do you usually go to bed and start trying to fall asleep? On weekdays or work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekdays or work days | |

| Bedtime | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | What time do you usually go to bed and start trying to fall asleep? On weekends or days off? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekends or days off | |

| Bedtime | Health and Aging in Africa | Over the past 4 weeks, what time did you usually turn the lights off to go to sleep? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Past 4 weeks | |

| Bedtime | Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study | What time do you usually go to bed in the evening (turn out the lights in order to go to sleep) on WEEKDAYS? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekday | |

| Bedtime | Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study | What time do you usually go to bed in the evening (turn out the lights in order to go to sleep) on WEEKENDS? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Weekend | |

| Bedtime | Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS) | [During the previous week] What time did you try to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Attempt to sleep | Previous week | |

| Bedtime | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKDAYS during the previous week (Sunday night through Friday Morning)] What time did you try to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Attempt to sleep | Previous week | |

| Bedtime | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKENDS during the previous week (Friday night through Sunday Morning)] What time did you try to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Attempt to sleep | Previous week | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a workday or school day, what is your earliest GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Work or school day | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a workday or school day, what is your latest GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Work or school day | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a workday or school day, what is your usual GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Work or school day | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a day off (e.g., weekend), what is your earliest GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Day off or weekend | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a day off (e.g., weekend), what is your latest GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Day off or weekend | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD NIGHT TIME as the time at which you are finally get in bed trying to fall asleep). On the night before a day off (e.g., weekend), what is your usual GOOD NIGHT TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Attempt to sleep | Day off or weekend | |

| Bedtime | Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) | At what time do you fall asleep? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | ||

| Bedtime | uMCTQ | On WORKDAYS I normally fall asleep at __:__ AM/PM (this is NOT when you get into bed!) | Fall asleep time | Workday | |

| Bedtime | uMCTQ | On WORK-FREE DAYS I normally fall asleep at __:__ AM/PM (this is NOT when you get into bed!) | Fall asleep time | Work-free | |

| Bedtime | Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment Study | At what time do you usually FALL ASLEEP on weekdays or your work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Workday or weekday | |

| Bedtime | Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment Study | At what time do you usually FALL ASLEEP on weekends or your non-work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Non-work day or weekend | |

| Bedtime | Twin Cities Metropolitan Area 2000 Travel Behavior Inventory | What time did<THEY>go to sleep up on<THEIR>travel day? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Travel day | |

| Bedtime | The Common Cold Project | Time went to sleep last night? [HH:MM]am/pm | Fall asleep time | Last night | |

| Bedtime | Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) | At about what time did you go to sleep yesterday? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Yesterday | |

| Bedtime | Biennial Media Consumption Survey | On a regular weeknight, what time do you usually go to sleep? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Weeknight | |

| Bedtime | Family Exchanges Study Wave 2, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | What time did you go to sleep last night? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Last night | |

| Bedtime | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | At what time do you usually FALL ASLEEP on weekends or your non-workdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Weekend | |

| Bedtime | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | At what time do you usually FALL ASLEEP on weekdays or your workdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Fall asleep time | Weeknight | |

| Bedtime | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On nights before workdays, I go to bed at ______ o clock … | Time into bed | Workday | |

| Bedtime | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On nights before free days, I go to bed at _______ o clock | Time into bed | Free day | |

| Bedtime | MrOS Sleep Study (MrOS) | During the past month, what time have you usually gone to bed at night? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Past month | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

At what time do you usually go to bed on nights before workdays or weekdays? [12:00am; 12:01–4:49am; 5:00am–5:29am; 5:30–5:59am; 6:00am–6:29am; 6:30–6:59am; 7:00–7:29am; 7:30–7:59am; 8:00–8:29am; 8:30–8:59am; 9:00–9:29am;9:30–9:59am;10:00–10:59am;11:00–11:59am;12:00–5:59pm;6–11:59pm] | Time into bed | Before workday or weekday | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

At what time do you usually go to bed on nights you do not work the next day or weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Not work the next day or weekend | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2003 Sleep and Aging |

At what time do you usually go to bed on weeknights? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Weeknight | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits |

At what time do you usually go to bed on nights you do not work the next day or weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Not work the next day or weekend | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

What time do you usually go to bed? [HH:MM]am/pm | Time into bed | ||

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain | Go to bed on work days or weekdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Workday or weekday | |

| Bedtime | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

Go to bed on non-work days or weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Non-work day or weekend | |

| Bedtime | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | During the past month, what time have you usually gone to bed at night? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Past month | |

| Bedtime | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos | The following two questions refer to the times you get in and out of bed in order to sleep (not including naps). What time do you usually go to bed? On weekdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Weekday | |

| Bedtime | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos | The following two questions refer to the times you get in and out of bed in order to sleep (not including naps). What time do you usually go to bed? On weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Weekend | |

| Bedtime | Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS) | [During the previous week] What time did you get in bed, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time into bed | Previous week | |

| Bedtime | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKDAYS during the previous week (Sunday night through Friday Morning)] What time did you get in bed, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time into bed | Weekdays | Previous week |

| Bedtime | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKENDS during the previous week (Friday night through Sunday Morning)] What time did you get in bed, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time into bed | Weekend | Previous week |

| Bedtime | Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2) | During the past month, when have you usually gone to bed at night? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time into bed | Past month | |

| Bedtime | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | At what time do you usually go to bed (in order to sleep) during the working week? [HH:MM] | Time into bed | Working week | |

| Bedtime | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | At what time do you usually go to bed (in order to sleep) during free days? [HH:MM] | Time into bed | Free days | |

| Wake time | MrOS Sleep Study (MrOS) | During the past month, when have you usually gotten up in the morning?” [HH:MM am/pm] | Get up | Past month | |

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits and Styles |

At what time do you usually get up on days you do not work or weekends?” [HH:MM am/pm] | Get up | Non-work day or weekend | |

| Wake time | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On workdays... I have to get up at ________ o clock | Get up | Workdays | |

| Wake time | Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2) | During the past month, when have you usually gotten up in the morning? [HH:MM am/pm] | Get up | Past month | |

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits |

Thinking about your usual non-workday or weekend, please answer the following questions. At what time do you usually get up on days you do not work or weekends? [12:00am; 12:01–4:49am; 5:00am–5:29am; 5:30–5:59am; 6:00am–6:29am; 6:30–6:59am; 7:00–7:29am; 7:30–7:59am; 8:00–8:29am; 8:30–8:59am; 9:00–9:29am;9:30–9:59am;10:00–10:59am;11:00–11:59am;12:00–5:59pm;6–11:59pm] | Get up | Non-workday or weekend | Past 4 weeks |

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2002 Adult Sleep Habits | At what time do you usually get up on days you work or on weekdays? [12:00am; 12:01–4:49am; 5:00am–5:29am; 5:30–5:59am; 6:00am–6:29am; 6:30–6:59am; 7:00–7:29am; 7:30–7:59am; 8:00–8:29am; 8:30–8:59am; 9:00–9:29am;9:30–9:59am;10:00–10:59am;11:00–11:59am;12:00–5:59pm;6–11:59pm] | Get up | Work or on weekday | |

| Wake time | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | During the past month, what time have you usually gotten up in the morning? [HH:MM] | Get up | Past month | |

| Wake time | Health and Aging in Africa | Over the past 4 weeks, what time did you usually get out of bed? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time out of bed | ||

| Wake time | Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) | What time do you usually get out of bed in the morning on WEEKDAYS? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time out of bed | Weekday | |

| Wake time | Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) | What time do you usually get out of bed in the morning on WEEKENDS? [HH:MM am/pm] | Time out of bed | Weekend | |

| Wake time | Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS) | [During the previous week] On average, what time did you get out of bed for the day? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time out of bed | Previous Week | |

| Wake time | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKDAYS during the previous week (Sunday night through Friday Morning)] On average, what time did you get out of bed for the day? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time out of bed | Weekday | Previous Week |

| Wake time | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKENDS during the previous week (Friday night through Sunday Morning)] On average, what time did you get out of bed for the day? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Time out of bed | Weekend | Previous Week |

| Wake time | Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) | At what time do you wake up? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | ||

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2011 Sleep and Technology |

What time do you wake up” [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | ||

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

Wake up on work days or weekdays?” [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Workday or weekday | |

| Wake time | National Sleep Foundation: 2015 Sleep and Pain |

Wake up on non-work days or weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Non-work day or weekend | |

| Wake time | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos | The following two questions refer to the times you get in and out of bed in order to sleep (not including naps). What time do you usually wake up? On weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekend | |

| Wake time | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos | The following two questions refer to the times you get in and out of bed in order to sleep (not including naps). What time do you usually wake up? On weekdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekday | |

| Wake time | HeartBEAT (Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment) Study | At what time do you usually WAKE UP on weekdays or your work days?” [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekday or work day | |

| Wake time | HeartBEAT (Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment) Study | At what time do you usually WAKE UP on weekends or your non-work days?” [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekends or non-work days | |

| Wake time | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | At what time do you usually WAKE UP on weekends or your non-work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekends or non-work days | |

| Wake time | Apnea Positive Pressure Long-Term Efficacy Study (APPLES) | At what time do you usually WAKE UP on weekdays or your work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekdays or your work days | |

| Wake time | Cleveland Family Study | What time do you did you wake up from your usual sleep on weekdays? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekday | |

| Wake time | Cleveland Family Study | What time do you did you wake up from your usual sleep on weekends? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekend | |

| Wake time | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On free days (please only judge normal free days, ie, without parties etc) I normally wake up at _______ o clock | Wake time | Free day | |

| Wake time | uMCTQ | On WORKDAYS I normally wake up at __:__ AM/PM (this is NOT when you get out of bed!) | Wake time | Workday | |

| Wake time | uMCTQ | On WORK-FREE DAYS when I don’t use an alarm I normally wake up at __:__ AM/PM (this is NOT when you get out of bed!) | Wake time | Work-Free day | |

| Wake time | Twin Cities Metropolitan Area 2000 Travel Behavior Inventory | Wake onset: What time did<TIIEY>wake up on<TIIIER>travel day? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | ||

| Wake time | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | What time do you usually wake up? On weekdays or work days? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekdays or work days | |

| Wake time | National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): | What time do you usually wake up? On weekends, or days off? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Weekends, or days off | |

| Wake time | CBS News Monthly Poll | What time do you usually wake up on a typical Sunday morning? [before 6am; between 6am and 659am; between 7am and 759am; between 8 and 859 am; between 9 and 959am; between 10 and 1059am; 11am or later; Work nights so sleep all day] | Wake time | Sunday morning | |

| Wake time | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | At what time do you usually wake up during the working week? [HH:MM] | Wake time | Working week | |

| Wake time | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | At what time do you usually wake up during free days? [HH:MM] | Wake time | Free days | |

| Wake time | Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS) | [During the previous week] What time was your final awakening, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Wake time | Previous week | |

| Wake time | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKDAYS during the previous week (Sunday night through Friday Morning)] What time was your final awakening, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Wake time | Weekdays | Previous week |

| Wake time | Split Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKENDS during the previous week (Friday night through Sunday Morning)] What time was your final awakening, on average? [HH:MM AM/PM] | Wake time | Weekend | Previous week |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a work day or school day, what is your earliest GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Work or school day | |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a work day or school day, what is your latest GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Work or school day | |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a work day or school day, what is your usual GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Work or school day | |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a day of (e.g., a weekend), what is your earliest GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Free or weekend day | |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a day of (e.g., a weekend), what is your latest GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Free or weekend day | |

| Wake time | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | (Please think of GOOD MORNING TIME as the time at which you finally get out of bed and start your day). Before a day of (e.g., a weekend), what is your usual GOOD MORNING TIME? [HH:MM am/pm] | Wake time | Free or weekend day |

Notes: A blank cell indicates that this component is not present in the question. The sentence case (e.g., all capitals) is displayed as represented on the survey.

We identified 47 distinct questions assessing bedtime. Nineteen questions asked participants to report “time got into bed” (e.g., Munich Chronotype Questionnaire: “On nights before free days, I go to bed at [ ] o clock …?”) [31], 12 questions asked participants their fall asleep time (e.g., Korea General Social Survey: “At about what time did you go to sleep yesterday?”) [28], and 16 questions asked participants when they first attempt to fall asleep (e.g., Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study: “What time do you usually go to bed in the evening (turn out the lights in order to go to sleep)?”) [60]. Sixteen questions asked participants to report their usual bedtimes in a specified timeframe (e.g., the MrOS Sleep Study: “During the past month, what time have you usually gone to bed at night?”) [32]. Thirty-five questions asked participants to distinguish between work- and free-day bedtimes (e.g., National Sleep Foundation 2002 Adult Sleep Habits: “At what time do you usually go to bed on nights before workdays or weekdays?”) [35].

We identified 43 distinct questions assessing wake times. Regarding event definitions, 30 questions asked participants to report the time they wake up (e.g., Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire: “At what time do you usually wake up during the working week?”) [18], while 7 questions assessing wake times asked participants to report the time they “get up” (e.g., National Sleep Foundation – 2005 Adult Sleep Habits and Styles: “At what time do you usually get up on days you do not work or weekends?”)[37] and 6 questions asked participants to report their out-of-bed time (e.g., the Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey: “On average, what time did you get out of bed for the day? [HH:MM AM/PM]”) [48]. Thirty-four of the wake time questions asked participants to distinguish between work- and free- days (e.g.: Heart Biomarker Evaluation in Apnea Treatment study: “At what time do you usually WAKE UP on weekends or your non-work days?”). Ten questions provided participants with a timeframe within which to report their wake times (e.g., Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an In-Depth Community in South Africa: “Over the past 4 weeks, what time did you usually get out of bed?”) [61].

We found one question that asked participants to report their method of waking (i.e., by an alarm clock; the uMCTQ: “On WORK-FREE DAYS when I don’t use an alarm I normally wake up at __:__ AM/PM (this is NOT when you get out of bed!)”) [31].

3.3. Sleep Latency (Table 4)

Table 4.

Sleep Latency Questions

| Category | Study | Question Wording [Response Scale] | Context | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Latency | Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) | During the past month, how long (in minutes) has it usually taken you to fall asleep each night? [MM] | Past month | |

| Sleep Latency | National Sleep Foundation: 2005 Adult Sleep Habits and Styles | How long, on most nights, does it take you to fall asleep? [HH:MM] | ||

| Sleep Latency | Framingham Heart Study | How long does it usually take you to fall asleep at bedtime? [HH:MM] | ||

| Sleep Latency | Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA 2) | During the past month, how long (in minutes) has it taken you to fall asleep at night? | Past month | |

| Sleep Latency | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | How long does it usually take to fall asleep at bedtime? | ||

| Sleep Latency | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On nights before workdays it takes me _______ mins to fall asleep | Work | |

| Sleep Latency | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On nights before free days it takes me _____ mins to fall asleep | Free | |

| Sleep Latency | Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) | On nights before free days I generally fall asleep after no more than ______ min | Free | |

| Sleep Latency | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | How long (in minutes) has it taken you to fall asleep each night? | ||

| Sleep Latency | Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ) | On most nights, how long, on average does it take you to fall asleep after you start trying? ______________ minutes | ||

| Sleep Latency | St Mary’s Hospital Sleep Questionnaire | How long did it take you to fall asleep last night? [HH:MM] | Last night | |

| Sleep Latency | Medical outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS) | How long did it take you to fall asleep during the past 4 weeks? [1: 0–15minutes; 2: 16–30minutes; 3: 31–45 minutes; 4: 46–60 minutes; 5: More than 60 minutes] | Past 4 weeks | |

| Sleep Latency | Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS) | [During the previous week] How long did it take you to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM] | Past week | |

| Sleep Latency | Split-Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKDAYS during the previous week (Sunday night through Friday Morning)] How long did it take you to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM] | Weekdays | Past week |

| Sleep Latency | Split-Week Self-Assessment of Sleep Survey (SASS-Y) | [On WEEKENDS during the previous week (Friday night through Sunday Morning)] How long did it take you to go to sleep, on average? [HH:MM] | Weekends | Past week |

| Sleep Latency | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | How long time (how many minutes as an average) do you stay awake in bed before you fall asleep (after lights off)? During the working days it takes me about [MM] minutes before I fall asleep. | Work | |

| Sleep Latency | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) | How long time (how many minutes as an average) do you stay awake in bed before you fall asleep (after lights off)? During free time it takes me about [MM] minutes before I fall asleep. | Free | |

| Sleep Latency | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | How long does it usually take you to fall asleep at bedtime? |

Notes: A blank cell indicates that this component is not present in the question. The sentence case (e.g., all capitals) is displayed as represented on the survey. Sleep latency questions were all similarly defined, therefore there is no “Event Definition” column.

We identified 18 distinct questions assessing sleep latency. The event definition for latency was uniform across questions (e.g., “minutes to fall asleep”). Seven sleep latency questions asked participants to distinguish between work- and free-day sleep latency (e.g., Munich Chronotype Questionnaire: “On nights before workdays, it takes me ___mins to fall asleep”) and 7 asked participants to report their sleep latency in a specific timeframe (e.g., Sleep Heart Health Study: “During the past month, how long (in minutes) has it usually taken you to fall asleep each night?”) [47].

3.4. Napping (Table 5)

We identified 12 distinct napping questions. Among the napping questions, three asked participants to report the number of naps that were “5 minutes or longer” while 1 question asked participants to report the number of naps that were “an hour or two.” Regarding context, one question asked participants to report work- versus free-day napping (e.g., Sleep Disorders Questionnaire: “How many daytime naps (asleep for 5 minutes or more) do you take on an average working day?”);[46] Five provided participants with a timeframe, such as the past week (e.g., National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: “During the past week, on how many days did you nap for 5 minutes or more”) [40].

4. Discussion

In this methodological review we identify 164 questions from 53 studies that measure sleep duration and/or timing via self-report. The specific aim of this review is to identify the prevailing approaches to self-reported sleep duration and/or timing questions and to document the variation in questions that collect information on sleep duration and timing. The overarching goal of this review is to highlight question options for future survey and diary designers to consider.

We report several primary findings regarding question wording for self-reported sleep duration and/or timing. First, we document significant semantic variation in the event definitions in each question. Across questionnaires, sleep duration is measured using a variety of approaches, including single item questions regarding estimated total time asleep (e.g., during the night or across the 24-hour day) or potentially derived from differences in times reported for bedtimes or sleep onset times and wake times. While it is not possible from the current literature to easily assess the impact of differences in wording on outcomes, there are individual studies that suggest that wording differences can substantially influence estimates of sleep duration. For example, Jackson and colleagues reported that (when compared to actigraphy-derived metrics), self-reported “average” sleep duration resulted in an underestimation of sleep by approximately 30 minutes, while sleep duration based on reported bed and wake times over-estimated sleep by 45 minutes [62].

Sleep timing question text related to bedtimes also varied widely. Questions most commonly asked participants to report the time they “get into bed;” this wording can result in over-estimation of sleep duration, especially if the participant spends time in bed reading or watching television before sleeping. While the limitation of asking a participant the time they “get into bed” may be addressed by also asking about estimated sleep latency, both healthy sleepers and those with insomnia, vary widely in their ability to accurately report sleep latency, and those with perceived problems with sleep quality may particularly over-estimate sleep latency, resulting in differential bias [63], [64]. Asking about time “going to sleep” similarly may be biased by information recall bias, especially among individuals with perceived poor sleep quality.

We also report important differences in assessment of wake times, including the time a person “wakes up” versus “gets out of bed.” Some questions simply asked when a participant typically “gets up,” which could be interpreted as either wake time or time out of bed. These small semantic nuances may have important implications for participant responses. Asking a participant when they “get out of bed” is likely to overestimate sleep duration, particularly if a participant spends an extended amount of time in bed after waking but before getting out of bed (e.g., to check their emails and other content on their mobile phones), and may be appropriate for scoring time in bed. On the other hand, a question that asks a participant when they “wake up” may be more appropriate for researchers interested in capturing sleep duration as opposed to time in bed.

We were surprised to see only one question address the method of awakening. Information about whether the awakening is spontaneous – and therefore sleep ended for internal physiological reasons, rather than externally imposed (e.g., an alarm clock, other person, pet, pain, noise) – may be important for some outcomes. It is also not known how a person who uses the “snooze bar “ on an alarm clock (i.e., to go back to sleep and have the alarm sound later) may respond to a question that asks the time they “woke up:” such a person could respond with their first wake time or the last time they awoke after falling asleep again once or multiple times.

Second, we document significant variation in context and timeframe cues. Despite the prevalence with which sleep schedules vary between work- and free-days (contributing to ‘social jetlag’[9] and its adverse cardiometabolic consequence[65]–[68]), these context cues were frequently absent in the questions. Another distinction is the way different days of the week were described. In some surveys, participants were asked to report their sleep on a “weekday” versus “weekend,” which may not yield expected results for individuals who work on weekends. Furthermore, for some people non-work days may not be entirely “free” days that allow more choice in sleeping timing and duration because of family, social, or other obligations. Therefore, researchers interested in sleep on a true “free” day may choose to ask participants to report sleep duration and/or timing on days they wake without an alarm, other external stimulus, or obligation. Distinguishing between work and free day sleep allows for estimation of social jetlag, which increases risk of adverse outcomes [9], [65]–[67], [69]. Night-to-night variability of sleep timing, which is also a risk factor for adverse outcomes [70], [71], cannot be calculated from these one-time surveys, but can be from sleep diaries or logs, which are discussed below.

Very few questions asked participants to report on their sleep in a specific timeframe, such as “In the past week, how many hours did you spend sleeping?” Instead, most questions asked how much individuals “usually sleep.” These language variants are important because behavioral research states that individuals are handicapped in their ability to report on an abstract time period, and the quality of responses increases dramatically when participants are provided with a specific time period, such as the prior week or month [72]. This is in accordance with recency bias, which refers to the fact that recall accuracy wanes as time increases between the time at which an event transpired and the time an individual is asked to recall the event [73]. In comparison, the nutrition literature has critiqued even 24-hour recall of dietary intake as susceptible to reporting biases, arguing in favor of immediate recall using a diary method [74]. Moreover, nutrition research has documented wide day-to-day variation in meal timing within individual by week, but stability of meal timing across months, suggesting that day-to-day variations may be obscured by monthly measurements [75]. Daily sleep diaries (paper or electronic versions), although more burdensome than surveys, may overcome some of the limitations of questions administered at single time points [76]. Nevertheless, a limitation of diaries, due to the high participant burden, is that some individuals forget or neglect to enter their sleep responses promptly and instead either leave items blank and/or complete some or all responses at a later time which would be expected to have decreased accuracy. Future research may consider ways of overcoming these limitations, such as designing new and novel technologies for capturing diary data and sending notifications to users when data are missing.