Abstract

The evolutionary origin of metazoan cell types such as neurons and muscles is not known. Using whole-body single-cell RNA sequencing in a sponge, an animal without nervous system and musculature, we identified 18 distinct cell types. These include nitric oxide–sensitive contractile pinacocytes, amoeboid phagocytes, and secretory neuroid cells that reside in close contact with digestive choanocytes that express scaffolding and receptor proteins. Visualizing neuroid cells by correlative x-ray and electron microscopy revealed secretory vesicles and cellular projections enwrapping choanocyte microvilli and cilia. Our data show a communication system that is organized around sponge digestive chambers, using conserved modules that became incorporated into the pre- and postsynapse in the nervous systems of other animals.

Sponges and evolutionary origins

Sponges represent our distant animal relatives. They do not have a nervous system but do have a simple body for filter feeding. Surveying the cell types in the freshwater sponge Spongilla lacustris, Musser et al. found that many genes important in synaptic communication are expressed in cells of the small digestive chambers. They found secretory machinery characteristic of the presynapse in small multipolar cells contacting all other cells and also the receptive apparatus of the postsynapse in the choanocytes that generate water flow and digest microbial food. These results suggest that the first directed communication in animals may have evolved to regulate feeding, serving as a starting point on the long path toward nervous system evolution. —BAP

Sponges represent a basal animal clade that lack neurons, muscles, and gut (Fig. 1A). They display canals for filter-feeding and waste removal (Fig. 1B and fig. S1) and are composed of three tissues: pinacocytes lining the canals, outer covering, and basal attachment layer (fig. S1, D to I); chambers of choanocytes with microvilli for food capture and motile cilia that drive water flow (fig. S1, J to O); and an inner mesohyl composed of stem, skeletogenic, and other mesenchymal cells. Despite their simple organization, sponges have genes that are usually expressed in neurons or muscles, including components of the pre- and postsynapse (1), and perform whole-body contractions that flush the canal system and expel debris (2). However, cells with integrative signaling functions are yet unknown.

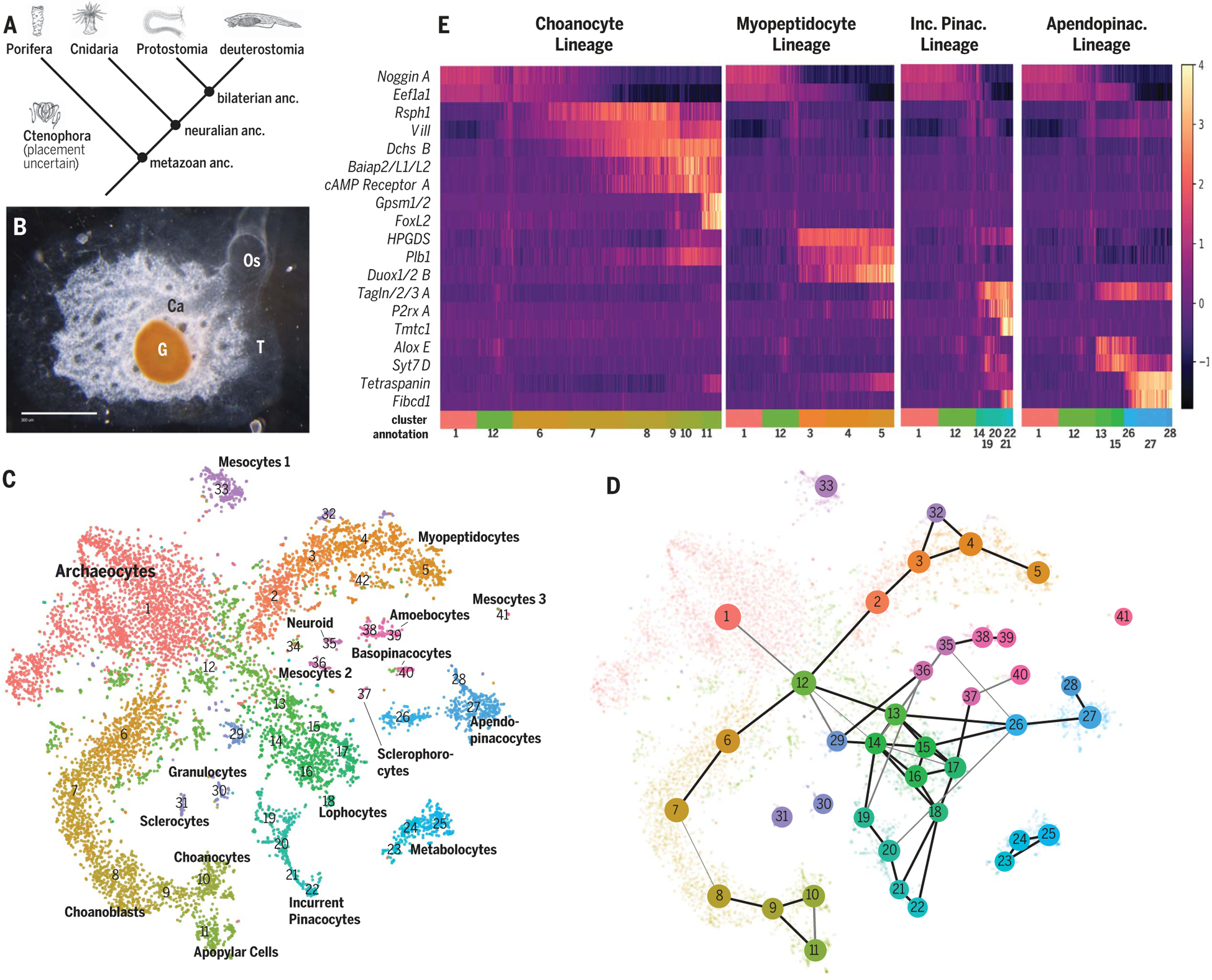

Fig. 1. S. lacustris cell types from whole-body single-cell RNA sequencing.

(A) Animal phylogeny. anc., ancestor. (B) S. lacustris overhead view. Scale bar, 300 mm. Ca, excurrent canals; G, gemmule; Os, osculum; T, epithelial tent. (C) tSNE plot of 10,106 cells colored by 42 clusters. (D) PAGA connectivity plot showing connection strength (edge thickness) and log number of cells in cluster (node diameter). (E) Scaled expression values of differentially expressed markers for PAGA paths. Apendopinac., apendopinacocyte; Inc. Pinac., incurrent pinacocyte.

Spongilla is composed of 18 distinct cell types

Using whole-body single-cell RNA sequencing, we conducted a comprehensive survey of genetically distinguishable cell types in 8-day-old freshwater demosponge Spongilla lacustris. Four capture experiments provided 10,106 S. lacustris cells expressing 26,157 genes (fig. S2, A to C).

Louvain graph clustering resolved 42 cell clusters with distinct expression signatures. Projection into two-dimensional expression space revealed a central cluster from which other clusters emanated (Fig. 1C and fig. S2D). This cluster expressed Noggin, Musashi1, and Piwi-like, demarcating stem cell–like archaeocytes (data S1) (3). We explored developmental relationships using partition-based graph abstraction (PAGA) (Fig. 1D), which assesses the degree of connectivity among clusters (4). This revealed connections along each arm of the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plot and with many isolated clusters, suggesting developmental trajectories from archaeocytes to all other clusters. Supporting this, archaeocyte marker expression decreased with distance from the central cluster (Fig. 1E). Interconnecting clusters exhibited profiles intermediate between archaeocytes and peripheral clusters (Fig. 1E and figs. S4 to S10), with few specific markers (fig. S3A). By contrast, peripheral clusters showed distinctive expression profiles of transcription factors and effector genes (fig. S3 and data S1), which indicates differentiated cell types.

We next imaged cell clusters via single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) of selected marker genes. This resolved spatial relationships of stem cells, developmental progenitors, and differentiated cell types. Probes for the archaeocyte marker Eef1a1 labeled large mesenchymal cells with a prominent nucleolus (fig. S11). Peripheral clusters 10 and 11 identified as choanocytes and apopylar cells by expression of actin-binding Villin and other choanocyte markers (5), whereas intermediate clusters 8 and 9 expressed proliferation markers, including Pcna, representing choanoblasts that often neighbored choanocyte chambers (fig. S11). Following similar strategies, we assigned 18 differentiated cell types (table S1) that represented a comprehensive molecular classification of Spongilla cell types consistent with previous morphological classification (6). For 13 previously described cell types, we use traditional nomenclature, or Greek translations (table S1). Five mesenchymal cell types were previously unrecognized, described here as myopeptidocytes, metabolocytes, and three different mesocytes.

Interrelationships of cell types in sponges

Animal cell types are organized into families, which share expression of regulatory and effector genes and are identified by phylogenetic analysis (7). We first used weighted correlation network analysis to identify gene sets that covary across differentiated cell types (fig. S12A). This revealed 28 distinct gene sets, delineating individual cell types and cell type groups, which hinted at the presence of hierarchical organization. We validated this via a “treeness” score that was estimated for every combination of four cell types (tetrads), with close to 60% of tetrads exhibiting greater hierarchy than expected by chance, which indicated strong support for gene expression hierarchy that is independent of gene set or normalization method (fig. S12, B to D).

We then generated a cell type tree using neighbor-joining tree reconstruction (Fig. 2A), which revealed well-supported clades of differentiated cell types robust to bootstrapping and variable gene sets (fig. S12, E to G). Major cell type clades included extended pinacocyte and choanocyte families, as well as two families of mesenchymal cells, one of which contained amoebocytes and neuroid cells and another of which contained sclerocytes and mesocytes that are enriched for noncoding genes (fig. S3F). Notably, we observed mesenchymal cell types scattered across all families and inter-nested with epithelial cell types. Evolutionary quantitative trait modeling revealed clade-specific genes and expression changes across the cell type tree (fig. S12H and data S1).

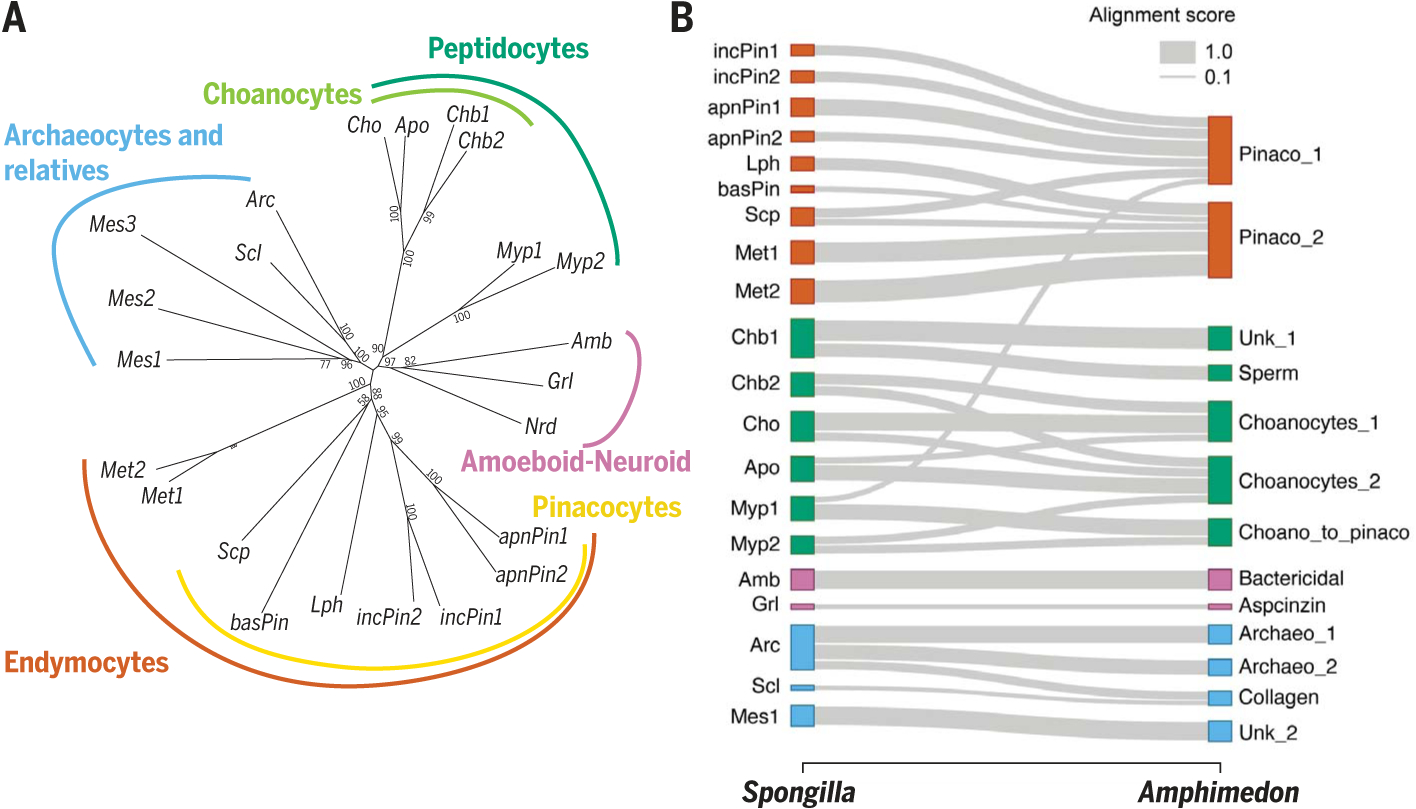

Fig. 2. Spongilla cell type families and single-cell SAMap alignment to Amphimedon.

(A) Spongilla cell type tree with bootstrap support. (B) Sankey plot mapping S. lacustris to adult A. queenslandica cell types. Amb, amoebocytes; Apo, apopylar cells; Arc, archaeocytes; basPin, basopinacocytes; Cho, choanocytes; Grl, granulocytes; incPin, incurrent pinacocytes; Lph, lophocytes; Mes1, mesocytes 1; Mes2, mesocytes 2; Met, metabolocytes; Myp, myopeptidocytes; Nrd, neuroid cells; Scl, sclerocytes; Scp, sclerophorocytes.

Assessing evolutionary conservation of cell types across sponges, we used self-assembling manifold mapping (SAMap) (8) to align Spongilla cells to a smaller single-cell dataset that was collected from adults of the demosponge Amphimedon queenslandica (9), which had a coarse identification of cell types based on expression signatures. We found consistent alignment of cell types within each family (Fig. 2B and fig. S13), albeit with higher resolution of annotated Spongilla pinacocyte- and choanocyte-related cell types. Newly identified Spongilla cell types aligned broadly with Amphimedon pinacocytes, as with metabolocytes, or were called an intermediate“choano-to-pinaco”cluster in Amphimedon, as with myopeptidocytes (Fig. 2B). For several Spongilla cell types, there were no Amphimedon counterparts, possibly because of incomplete cell type assignments in this dataset.

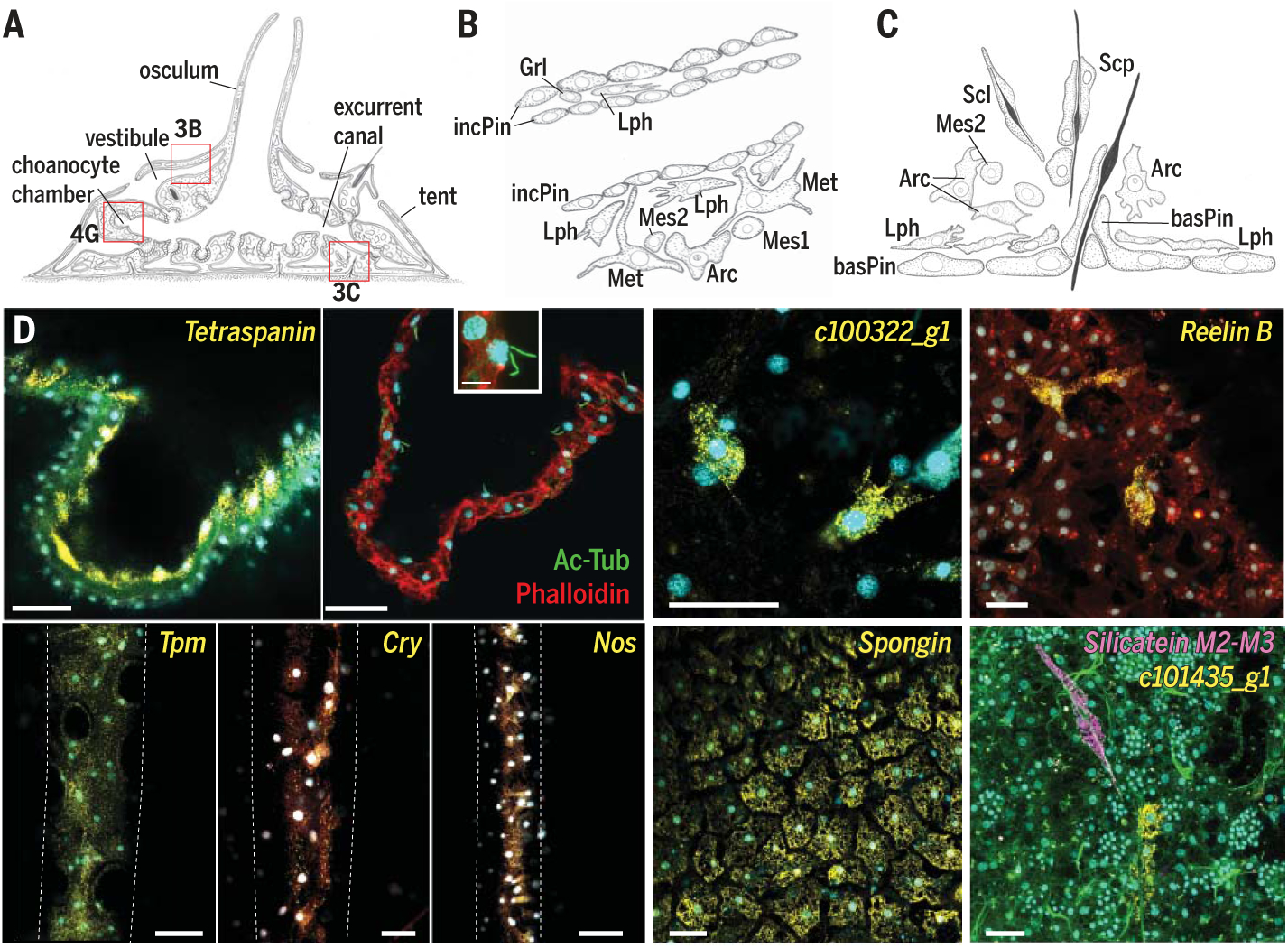

Endymocytes are contractile and respond to nitric oxide signaling

We name each major cell type family to reflect its role within the organism. The family of endymocytes (vδvμα: “lining, clothing”) covers and shapes the sponge body (Fig. 3 and fig. S14). Incurrent pinacocytes constitute both layers of the tent, the vestibule lining, and the outer osculum layer. Apendopinacocytes line the excurrent canals and inner osculum layer. Basopinacocytes make up the basal epithelial layer attached to the substrate. Mesenchymal endymocytes were often found in proximity to pinacocytes and include collagen-secreting lophocytes, sclerophorocytes, and metabolocytes. Gene ontology (GO) analysis for endymocyte-specific markers found strong enrichment for Wnt and transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) signaling and actomyosin-based contractility (figs. S14L and S15 and data S1), which is consistent with pinacocytes mediating whole-body contractions (10). Endymocytes also express contractile-cell master regulators serum response factor (Srf) and Csrp1/2/3 (also known as muscle LIM protein) (11), which suggests a conserved regulatory module for actomyosin contractility (fig. S16).

Fig. 3. Endymocyte cell type family.

(A) Illustration of juvenile S. lacustris. Red boxes outline locations illustrated in other figure panels. (B) Drawing of incurrent pinacocytes (incPin) that make up the tent and vestibule, with adjacent mesenchymal cells: lophocytes (Lph), metabolocytes (Met), archaeocytes (Arc), mesocytes 1 (Mes1), and mesocytes 2 (Mes2). (C) Illustration of spicule production (sclerocytes, Scl), transport (sclerophorocytes, Scp), and anchoring (basopinacocytes, basPin). (D) smFISH of endymocyte markers. incPin, Tpm; apnPin, Tetraspanin; lph, c100322_g1; met, Reelin B; basPin, Spongin; Scp, c101435_g1. Membrane stains Fm-143Fx (red) and CellBrite Fix (green; also possibly stains collagen); nuclei 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain (cyan). Scale bar, 30 μm.

In other demosponges, the signaling molecules γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, and nitric oxide (NO) alter whole-body contractions (12, 13). We found paralogs of the metabotropic GABAB receptor used in distinct endymocytes (fig. S17). Pinacocytes also coexpressed nitric oxide synthase, which catalyzes synthesis of NO, together with the NO receptor Gucy1B2 (fig. S16). In the marine demosponge Tethya wilhelma, NO induces and modulates whole-body contractions (14) but only affected the osculum in the freshwater sponge Ephydatia muelleri (13). During the S. lacustris contraction cycle (fig. S18, A and B, and movie S1), the collapse of osculum and incurrent systems first causes excurrent canals to swell, which subsequently shrink to expel water through the osculum before returning to the resting state. We tested the response to NO by treating juvenile sponges with NOC-12, a donor of NO, and 1H-[1,2,4]Oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), an inhibitor of the NO receptor (fig. S18, C to F, and movies S2 and S3). NO release immediately shrank the incurrent system, including incurrent canals and tent, and expanded the excurrent canals, as during initial stages of the contraction cycle (fig. S18C and movie S2). Subsequently, the incurrent system exhibited short, pulsed movements and returned to resting state only after NO removal (fig. S18C). The subtler effect of ODQ treatment involved expansion of incurrent, and possibly excurrent, canal systems (fig. S18D and movie S3). Serial combinations of NOC-12 and ODQ gave similar results (fig. S18, E and F), establishing a key role of NO in initiating and regulating the contraction cycle in S. lacustris, and possibly ancestrally in demosponges.

Beyond contraction, cell type–specific expression programs indicated endymocyte roles in photo- and mechanosensation, skeleton formation, glucose metabolism, and production of reactive oxygen for defense (fig. S15). Single orthologs of Six and Pax (15) are expressed in a complementary manner (fig. S16), with Six+ incurrent pinacocytes enriched for genes involved in circadian clock entrainment, and the blue-light sensor cryptochrome, which suggests light sensitivity, and PaxB+ apendopinacocytes expressing mechanosensory components and exhibiting short cilia (Fig. 3D and fig. S16). Next, we found basopinacocytes enwrapping spicules anchored at the base of the sponge (Fig. 3C and fig. S14, F and G) and sclerophorocytes forming clusters alongside mature spicules (Fig. 3, C and D, and fig. S14I), similar to SoxB+ spicule “transport cells” in E. muelleri (16). Both are enriched in genes that organize fibrillar collagen, and sclerophorocytes in secretory pathway genes (figs. S15 and S16). Multipolar metabolocytes exhibit wide extensions that may contact pinacocytes (Fig. 3D and fig. S14, J and K). They exhibit manifold metabolic activity (fig. S15), with specific up-regulation of the complete set of enzymes that mediate glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, and specific expression of glycogen phosphorylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase (fig. S16). Metabolocytes also express the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex known to produce reactive oxygen species for bacterial defense (figs. S15 and S16) (17).

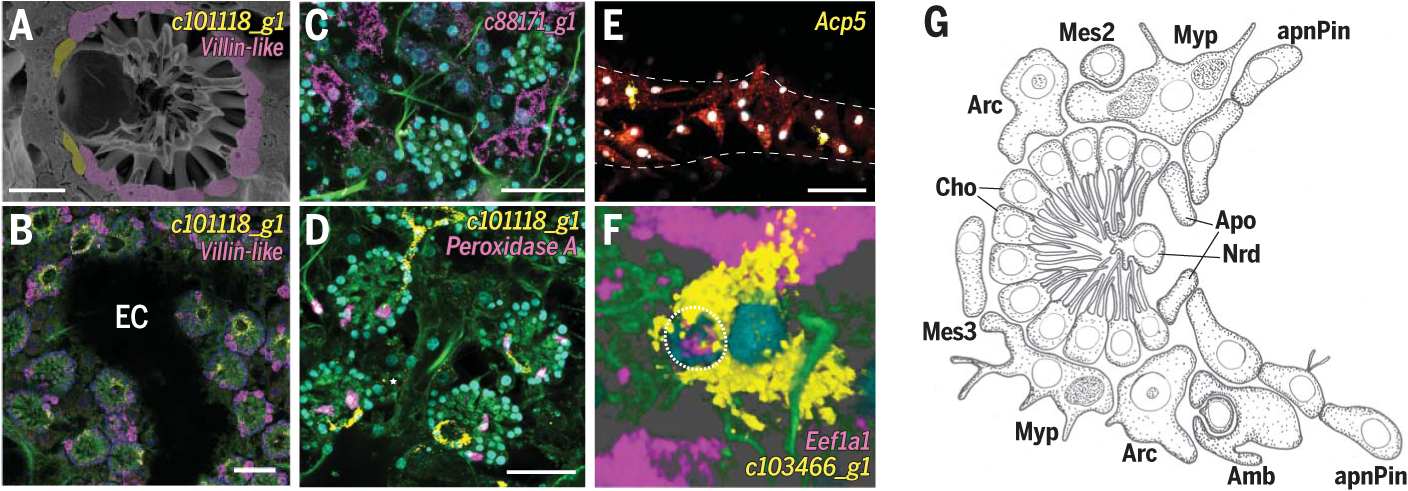

Digestive peptidocytes express “postsynaptic” scaffolding genes

The family of peptidocytes (πέπτειν, “to digest”) share a role in digestion, which is reflected by phagocytic vesicle and lytic vacuole gene expression (figs. S19 and S20). They comprise choanocytes and apopylar cells, which form the excurrent pore of choanocyte chambers (Fig. 4, A, B, D, and G, and fig. S21). Myopeptidocytes are an abundant constituent of the mesohyl (Fig. 4C and fig. S21A) with long projections that contact each other and other cells, including choanocytes. They express actomyosin-based contractility modules (figs. S15 and S19) and three orthologs of Mib2 (fig. S20) that regulates myofiber integrity (18), indicating a possible role for mesohyl in contractions.

Fig. 4. Peptidocyte and amoeboid-neuroid cell type families.

(A) SEM of choanocyte chamber. Scale bar, 10 mm. (B to F) smFISH of neuroid and amoeboid markers: choanocytes (Cho), villin-like; apopylar cells (Apo), c101118_g1; myopeptidocytes (Myp), c88171_g1; neuroid cells (Nrd), Peroxidase A; granulocytes (Grl), Acp5; and amoebocytes (Amb), c103466_g1. Dashed line indicates epithelial tent. Dotted line outlines archaeocyte being engulfed by amoebocyte. Membrane stains Fm-143Fx (red) and CellBrite Fix (green); nuclei DAPI stain (cyan). Scale bars, 30 μm. EC, excurrent canal. (G) Illustration of choanocyte chamber and neighboring mesenchymal cells.

In line with digestion functions (19), choanocytes express the transcription factors Rbpj, Klf5, and NK homeobox 6 (fig. S20 and data S2 and S3) (20), and sorting nexin family members involved in macropinocytosis (figs. S19 and S20), an unregulated form of engulfment (21). The choanocyte subclade is enriched for genes of the receptive/postsynapse complex in animals with neurons (Fig. 5 and fig. S17), including “postsynaptic scaffold” (homer, shank, and Baiap2) and “dystrophin-syntrophin signaling complex” (22). Notably, scaffold genes such as Baiap2 and Eps8 are also active in organizing the actin skeleton of microvilli (22), and the single ortholog of ezrin, radixin, and moesin, known to stabilize the microvillar cytoskeleton, colocalized with F-actin in choanocyte microvilli (fig. S22). These data suggest a role of postsynapse-like scaffolding machinery in the choanocyte microvillar collar.

Fig. 5. Expression of “pre-” and “postsynaptic” genes.

Dot plot showing expression of manually curated synaptic GO terms. Archae., Archaeocytes; rel., relatives.

The amoeboid-neuroid family: A role in cell clearance

The amoeboid-neuroid family comprises three small, tri- or multiangular cell types (Fig. 4, D to G, and fig. S21, B to G). The neuroid cells (23), also called “central cells” (24), associate with choanocyte chambers, whereas amoebocytes and granulocytes are dispersed in the mesohyl. We also observed granulocytes next to tent pinacocytes. Amoebocytes bear long extensions and were seen to engulf other mesohyl cells (Fig. 4F and fig. S21D), which is consistent with a macrophage-like role and classification as “bactericidal” cells in A. queenslandica (9). Family-specific transcription factors suggest a role in innate immunity. Nuclear factor kappa B subunit (NFκB), which controls cellular immune responses, and high mobility group box 1/2/3 (Hmgb1/2/3) (fig. S23) are universal sentinels of the nucleic acid–mediated innate immune response and activate key inflammatory pathways. Furthermore, amoebocytes specifically express the only Nfat ortholog, active in adaptive and innate immunity, and Gata, a conserved determinant of immunocytes (fig. S23) (25). We also noted family-specific expression of engulfment and cell motility (Elmo), which is essential for en gulfing dying cells in worms (26), and the small guanosine triphosphatase Rab21, which is fundamental for phagosome formation (27).

Communication between neuroid cells and choanocytes

Neuroid cells exhibited a secretory profile via up-regulation of the signal peptidase complex (fig. S19) and enrichment for “presynaptic” gene sets (also observed in endymocytes) (Fig. 5 and figs. S24 to S27) (22), suggesting communication via vesicle secretion. Notably, nearly all neuroid cells were associated with choanocyte chambers, with most chambers containing at least one neuroid cell in the middle of the chamber or in its lining (fig. S21, B and C). Corroborating historical descriptions (23, 24), we observed multiple extensions from neuroid cells contacting individual choanocytes (fig. S21B).

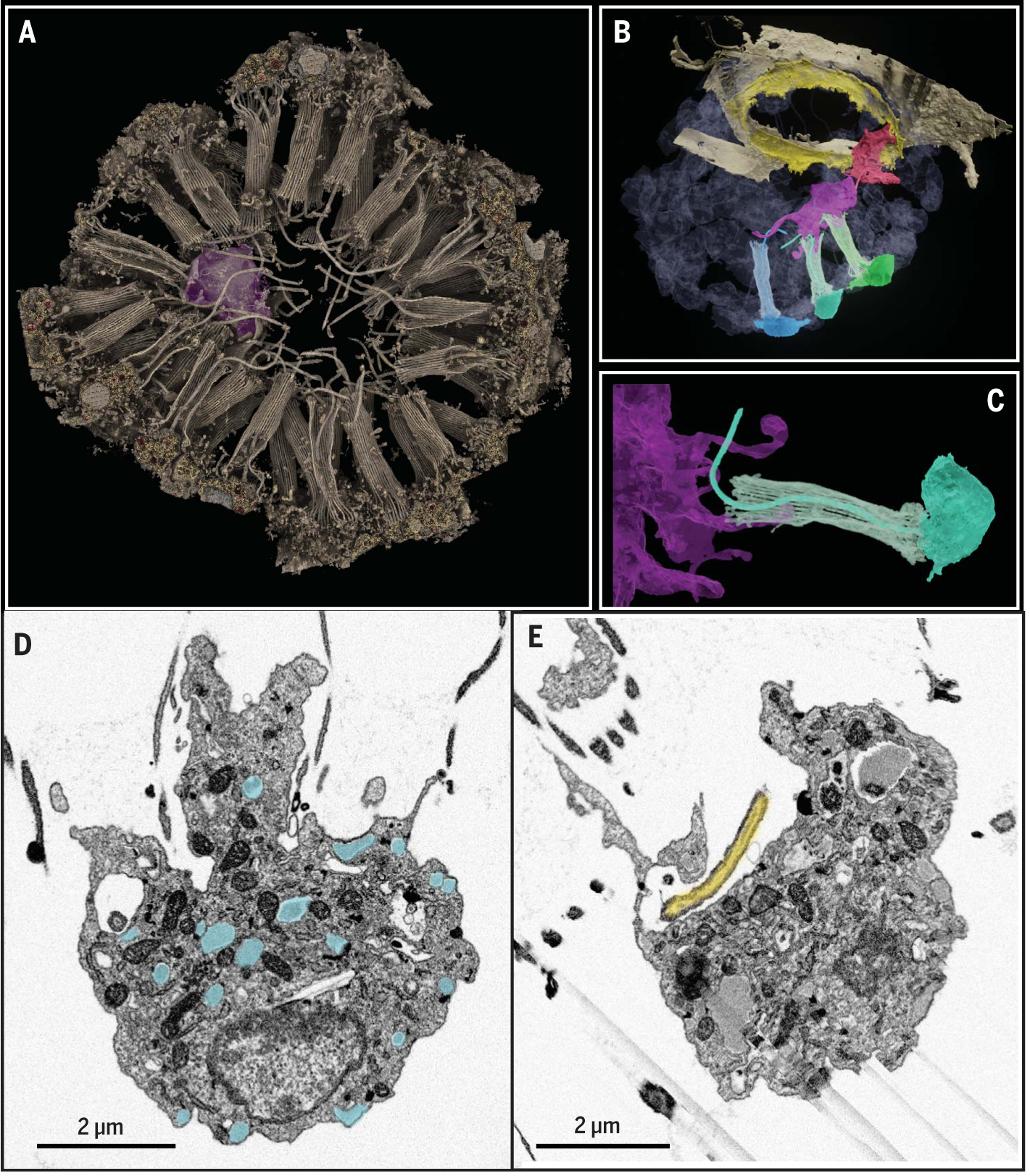

To further characterize neuroid cell interactions, we devised a two-step imaging strategy, correlating confocal light microscopy and laboratory- or synchrotron-based x-ray imaging with focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM). These volumes are publicly accessible via the interactive FIJI plugin MoBIE (materials and methods). First, we acquired a lower-resolution FIB-SEM volume of an entire choanocyte chamber that contained two neuroid cells, identified by light microscopy. Using machine learning, we then segmented the entire volume (Fig. 6, A to C; fig. S28, A to C; and movies S4 and S5) and found one neuroid cell positioned centrally and another near the apopylar pore (Fig. 6, A and B), each with multiple protrusions directed toward different choanocyte collars and nearly always contacting and enwrapping one or more microvilli (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S28, A to C). Occasionally, extensions followed cilia that emerged straight and then bent, in contrast to normal undulatory cilia, which suggested that they may pause beating.

Fig. 6. FIB-SEM of neuroid-choanocyte interactions.

(A) Rendered three-dimensional volume of choanocyte chamber with neuroid cell (violet). (B) Segmented volume showing two neuroid cells (violet and red) contacting cilia and microvillar collars of three choanocytes (blue, turquoise, and green) and apopylar cells (yellow). (C) Segmented neuroid cell (violet) with filopodia extending into the microvillar collar (turquoise). (D) High-resolution FIB-SEM section of neuroid cell 1 with secretory vesicles (cyan overlay). (E) High-resolution FIB-SEM section of neuroid cell 1 forming pocket around tip of choanocyte cilia (yellow overlay).

Second, we captured subcellular details of two additional neuroid cells via high-resolution FIB-SEM. Exploiting the deep penetration of x-rays (fig. S29), we combined the large field of view that was acquired via a laboratory-based x-ray microCT (microscopic x-ray computed tomography) with the smaller, higher-resolution field of view recordable on a synchrotron beam-line. Registration of the synchrotron tomogram to the full sample block enabled precise trimming and acquisition of higher-resolution FIB-SEM data. We term this method correlative x-ray electron microscopy (CXEM). In these volumes, we observed numerous secretory vesicles 50 to 500 nm in size throughout both neuroid cells, including in the cellular protrusions (Fig. 6D and fig. S28D), and two Golgi stacks per cell, each oriented toward the cellular protrusions (figs. S28, E and F). Larger vacuoles represented endolysosomes or phagosomes (fig. S28, G and H) and contained heterogeneous material, including a likely bacterial cell (fig. S28G, arrow), which is consistent with phagocytosis and engulfment gene expression. Lastly, both neuroid cells formed long invaginating pockets that encased cilia tips with shaft-like constrictions (Fig. 6E and fig. S28I). We never observed direct contact between neuroid cells and choanocyte collar or cilia that would have resembled synapses with targeted vesicle release. Together, these observations suggest a dual role for neuroid cells in intercellular communication and in the clearing of bacteria or cellular debris within choanocyte chambers.

Discussion

A notable feature of gene and species evolution is a treelike history of common descent. We observed significant hierarchical organization among differentiated cell type expression programs in Spongilla, which was reflected by transcription factors and functional modules that are shared across subclades in the cell type tree. We propose that this reflects evolutionary relatedness rather than homoplasy (28) and that major sponge cell type families, such as endymocytes and peptidocytes, originated via cell type diversification. These evolutionary lineages are distinct from developmental trajectories, although both histories can be congruent when closely related transcriptional programs arise from the same developmental precursors, as observed in this work.

For endymocytes, our experiments revealed coordination of the contraction cycle via NO signaling, which also triggers endothelial muscle relaxation in vertebrates (29). Endymocyte transcription factor signatures support an evolutionary link between sensory-contractile systems in sponges and other animals. In Spongilla and the calcisponge Sycon ciliatum (30), pinacocytes specifically express the sole sponge ortholog of Msx, which is known to specify sensory ectodermal regions and myocytes in other animals (31). Msx activates atonal, which plays a conserved role in mechanosensory neuron specification (31) and demarcates sponge pinacocytes together with its binding partner Tcf4/E12/47. Most notably, apendopinacocytes and incurrent pinacocytes express the single sponge orthologs of the Pax and Six homeodomain transcription factors, respectively, that also play conserved roles in sensory cell and myocyte specification (15). Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that sensory cells and myocytes arose by division of labor from shared evolutionary precursors that formed sensory-contractile, conducting epithelia in metazoan ancestors (22).

For peptidocytes, our analysis of cellular transcriptomes suggests digestive functions. Peptidocytes specifically express Klf5, which controls cytodifferentiation of intestinal epithelia (32), and choanocytes express Nkx6, Rbpj, and Notch that specify pancreatic cell types and absorptive enterocytes (20). Nkx6 also demarcates pharyngeal and exocrine gland cells in sea anemone (33). Peptidocytes thus may have existed in metazoan ancestors, initially with intracellular digestion as observed in sponges and their unicellular relatives (19) and then acquiring external digestion, first as part of a digestive mucociliary sole and then incorporated into the gut (34).

For neuroid cells, our data suggest communicative functions within choanocyte chambers. Their close physical interaction with choanocyte microvillar collars and cilia, the expression of secretory genes, and the presence of secretory vesicles suggest a coordinative role in feeding, possibly by modulating ciliary arrest. Spongilla is a sponge with open architecture, in which incoming particles are continuously removed to prevent clogging. For this, the neuroid cells may stop water flow, engulf intruding cells and/or debris, and regulate microbial food uptake in response to quality and availability. Homology of neuroid cells to other animal cell types is unclear, as their transcription factor identity suggests no clear affinity other than limited resemblance to innate immune cells.

All three cell type families use conserved neural gene sets. This parallels the wider occurrence of neural modules across epithelial and fiber cells in the simple placozoans (9) and showcases possible parallel routes toward neuron evolution (35). In line with this, the contractile network and neurosecretory network hypotheses envisage the origin of neurons in distinct cellular contexts that resemble endymocytes and peptidocytes (36). Our work thus puts sponges center stage in elucidating nervous system evolution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Advanced Light Microscopy Facility, including S. Schnorrenberg, and the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the EMBL for help with imaging and other support. We also thank G. P. Wagner and A. Dighe for valuable discussions about modeling gene expression on cell type trees, which served as the impetus for designing our quantitative trait modeling method to identify cell-type clade genes.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the European Research Council (BrainEvoDevo 294810 and NeuralCellTypeEvo 788921 to D.A.); by the Marie Curie COFUND program from the European Commission (to J.M.M.); by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 764840 IGNITE (to F.R.); by National Programme for Fostering Excellence in Scientific and Technical Research (grant PGC2018-098073-AI00 MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE; to J.H.-C.); by Severo Ochoa Centres of Excellence Programme from the State Research Agency (AEI) of Spain [grant SEV-2016-0672 (2017-2021) to C.P.C.); by Research Technical Support Staff Aid (grant PTA2019-017593-I / AEI / 10.13039/501100011033 to A.H.-P.); by LMU Munich’s Institutional Strategy LMUexcellent within the framework of the German Excellence Initiative (to G.W.); by the Baden-Wuerttemberg Stiftung (to C.P.); and by the NIH and NSF (grants R01NS114491, 1146575, 1557923, 1548121 and 1645219) and Human Frontiers Science Program (to L.L.M.).

Footnotes

Data and materials availability:

Raw and processed RNAseq datasets generated for this study are available from NCBI GEO (accession number GSE134912). Custom analysis scripts, de novo transcriptome, proteome, and phylome are available on GitLab (https://git.embl.de/musser/profiling-cellular-diversity-in-sponges-informs-animal-cell-type-and-nervous-system-evolution) and archived at Zenodo (37).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Srivastava M et al. , Nature 466, 720–726 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott GRD, Leys SP, J. Exp. Biol 210, 3736–3748 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alié A et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, E7093–E7100 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf FA et al. , Genome Biol. 20, 59–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peña JF et al. , Evodevo 7, 13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissenfels N, Biologie und Mikroskopische Anatomie der Süßwasserschwämme (Spongillidae) (Gustav Fischer, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang C, Consortium FANTOM, Forrest AR, Wagner GP, Nat. Commun 6, 6066 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarashansky AJ et al. , eLife 10, e66747 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebé-Pedrós A et al. , Nat. Ecol. Evol 2, 1176–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickel M, Scheer C, Hammel JU, Herzen J, Beckmann F, J. Exp. Biol 214, 1692–1698 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miano JM, Long X, Fujiwara K, Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 292, C70–C81 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellwanger K, Eich A, Nickel M, J. Comp. Physiol 193, 1–11 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott GRD, Leys SP, J. Exp. Biol 213, 2310–2321 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellwanger K, Nickel M, Front. Zool 3, 7 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera A et al. , Evol. Dev 15, 186–196 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama S et al. , Curr. Biol 25, 2549–2554 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawahara T, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, BMC Evol. Biol 7, 109–121 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrasco-Rando M, Ruiz-Gómez M, Development 135, 849–857 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laundon D, Larson BT, McDonald K, King N, Burkhardt P, PLOS Biol. 17, e3000226–e22 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gopalan V et al. , Cancer Res. 81, 3958–3970 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JTH et al. , PLOS ONE 5, e13763–e13 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arendt D, The Evolutionary Assembly of Neuronal Machinery, Curr. Biol 30, R603–R616 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Ceccatty MP, Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. Biol. Anim 17, 203–288 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiswig HM, Brown MJ, Zoomorphologie 88, 81–94 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartenstein V, Mandal L, BioEssays 28, 1203–1210 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gumienny TL et al. , Cell 107, 27–41 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khurana T, Brzostowski JA, Kimmel AR, EMBO J. 24, 2254–2264 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arendt D, Bertucci PY, Achim K, Musser JM, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 56, 144–152 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer RMJ, Ferrige AG, Moncada S, Nature 327, 524–526 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortunato SAV et al. , Nature 514, 620–623 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, E6352–E6360 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell SM et al. , Dev. Biol 375, 128–139 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinmetz PRH, Aman A, Kraus JEM, Technau U, Nat. Ecol. Evol 1, 1535–1542 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arendt D, Benito-Gutierrez E, Brunet T, Marlow H, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 370, 20150286–20150286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moroz LL, Kohn AB, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 371, 20150041 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arendt D, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 376, 20200347 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musser J, Gitlab repository zip for Profiling cellular diversity in sponges informs animal cell type and nervous system evolution, Zenodo (2021); 10.5281/zenodo.5094890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw and processed RNAseq datasets generated for this study are available from NCBI GEO (accession number GSE134912). Custom analysis scripts, de novo transcriptome, proteome, and phylome are available on GitLab (https://git.embl.de/musser/profiling-cellular-diversity-in-sponges-informs-animal-cell-type-and-nervous-system-evolution) and archived at Zenodo (37).