Abstract

Background and Objective

Additive manufacturing of nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs using 3D printing technology presents a viable alternative to address the immediate shortage problem of standard flock-headed swabs for rapid COVID-19 testing. Recently, several geometrical designs have been proposed for 3D printed NP swabs and their clinical trials are already underway. During clinical testing of the NP swabs, one of the key criteria to compare the efficacy of 3D printed swabs with traditional swabs is the collection efficiency. In this study, we report a numerical framework to investigate the collection efficiency of swabs utilizing the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approach.

Methods

Three-dimensional computational domain comprising of NP swab dipped in the liquid has been considered in this study to mimic the dip test procedure. The volume of fluid (VOF) method has been employed to track the liquid-air interface as the NP swab is pulled out of the liquid. The governing equations of the multiphase model have been solved utilizing finite-volume-based ANSYS Fluent software by imposing appropriate boundary conditions. Taguchi's based design of experiment analysis has also been conducted to evaluate the influence of geometric design parameters on the collection efficiency of NP swabs. The developed model has been validated by comparing the numerically predicted collection efficiency of different 3D printed NP swabs with the experimental findings.

Results

Numerical predictions of the CFD model are in good agreement with the experimental results. It has been found that there prevails huge variability in the collection efficiency of the 3D printed designs of NP swabs available in the literature, ranging from 2 µl to 120 µl. Furthermore, even the smallest alteration in the geometric design parameter of the 3D printed NP swab results in significant changes in the amount of fluid captured.

Conclusions

The proposed framework would assist in quantifying the collection efficiency of the 3D printed designs of NP swabs, rapidly and at a low cost. Moreover, we demonstrate that the developed framework can be extended to optimize the designs of 3D printed swabs to drastically improve the performances of the existing designs and achieve comparable efficacy to that of conventionally manufactured swabs.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal swabs, Additive manufacturing, 3D printing, COVID-19, Computational fluid dynamics (CFD), Volume of Fluid method, Taguchi method

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has significantly affected the human race worldwide [1,2]. The health care system of many countries is already overwhelmed due to this ongoing pandemic. The mortality rate due to COVID-19 has already surpassed the 5.7 million mark globally and the overall cases are close to 400 million [3]. For slowing the transmission of the virus, there is an unprecedented need for a high number of testing and contact tracing along with other public health measures such as social distancing and masking. Importantly, one of the crucial factors for COVID-19 testing is minimizing the test result turnaround time so that people testing positive could be advised to self-isolate and a timely contact tracing can be done for all close contacts. This is extremely critical to slow the spread of the pandemic and develop an appropriate COVID-19 response strategy. A nasopharyngeal (NP) swab is one of the most critical components of the COVID-19 testing kit [4]. NP swabs are flexible narrow sticks with a bristled end that is covered with absorbing materials such as nylon, rayon, cotton, polyester, etc. For collecting the specimen, generally, the NP swab is inserted through the nostril along the floor of the nasal passage until either the resistance is met or the inserted depth is equivalent to one-half the distance from the nostril to the front of the ear. The swab is then gently rubbed and rolled to absorb secretions, and withdrawn, and immediately placed in the vial containing the transport medium. The ongoing pandemic has significantly dented the global supply chain of NP swabs, along with other medical supplies, thus posing massive challenges for conducting adequate COVID-19 tests to mitigate and suppress the spread of virus. This ongoing problem of shortage in medical supplies and conventional NP swab manufacturing supply chain interruptions have motivated the scientific community to explore the 3D printing (additive manufacturing) techniques as a possible solution to fill some of the gaps and address the utmost need for large-scale production of NP swabs for COVID-19 detection [4], [5], [6], [7].

3D printing of NP swabs can be thought of as a local rapid short-term response to resolve the swab shortage crisis and meet supply chain needs. The key advantages of design and 3D printing of NP swabs are: (a) simplicity (if the multistep process of applying flock is avoided), (b) the widespread availability and use of 3D printing capacity in biomedical devices and biocompatible material applications, and (c) ability to rapidly iterate prototypes [8,9]. Once the NP swab has been produced using 3D printing technology, it still needs to go through a rigorous clinical trial process to demonstrate its efficacy. Some of the preliminary results of 3D printed NP swabs are quite discouraging, which suggests that conventional swabs outperform the 3D printed swabs [8,9]. The current limitations of the 3D printed NP swabs include inferior quality of the collected samples, inadequate clinical specimens, inappropriate materials (e.g., too sticky or brittle), inappropriate designs (e.g., sharp heads), patient discomfort particularly among kids, and limited mechanical stability, to name a few [4,[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. It is noteworthy to mention that most of these limitations are directly linked to the huge variability in mucus rheology and nasal cavity geometries in the target population. Thus, there is an urgent need of addressing the existing design issues of the 3D printed NP swabs to make them clinically efficient for COVID-19 detection and to prevent outbreaks.

Several geometrical designs have been recently proposed for 3D printed NP swabs and their clinical trials are already underway [17]. The rigorous steps associated with preclinical testing of the 3D printed design of NP swabs along with the associated testing parameters and acceptance criteria have been presented in [8]. The comparative design review of NP swabs has been presented in [9]. This study also highlights the design constraints and objectives for the rapid fabrication of NP swabs using 3D printing techniques. Usually, the preclinical testing of 3D printed design of NP swabs involves evaluation of mechanical performance (i.e., head and neck flexibility, durability/strength), sample collection efficiency (uptake/release and viral RNA recovery), and other preclinical metrics (i.e., PCR compatibility, physical abrasion) [8,16]. Computational modeling and simulations could significantly assist in evaluating some of these metrics, rapidly and inexpensively. Some studies could be found in the literature, quantifying and optimizing the mechanical performances of 3D printed geometric designs of NP swabs using computational approaches [18], [19], [20]. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no numerical study available in the literature that quantifies the sample collection efficiency of these swabs, which is one of the key criteria to compare the efficacy of 3D printed NP swabs with traditional swabs. Thus, in the present study, we aim to develop a numerical framework to investigate the collection efficiency of NP swabs using the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approach. A CFD based analysis has been conducted to quantify the collection efficiency of recently reported 3D printed geometric designs of NP swabs available in the literature, as well as new novel designs of our lab. Utilizing the design of experiments approach, we also report a case study conducting parametric analysis for quantifying the relative influence of geometric design variables on the collection efficiency of NP swabs. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) has also been conducted on the selected design to quantify the ranking and contribution of critical geometric design variables on the collection efficiency of the swab. Such analysis would significantly assist in optimizing the geometric designs of 3D printed NP swabs to drastically improve the sample collection efficiency of the existing designs and achieve comparable efficacy to that of traditional swabs.

2. Mathematical modeling

This section provides the details of the considered geometric design of 3D printed NP swabs, along with the mathematical and computational framework adopted to conduct the CFD based analysis for evaluating the collection efficiency of different NP swabs. The experimental details related to 3D printing of NP swabs and dip test procedure have also been presented in this section.

2.1. Geometric designs of NP swabs

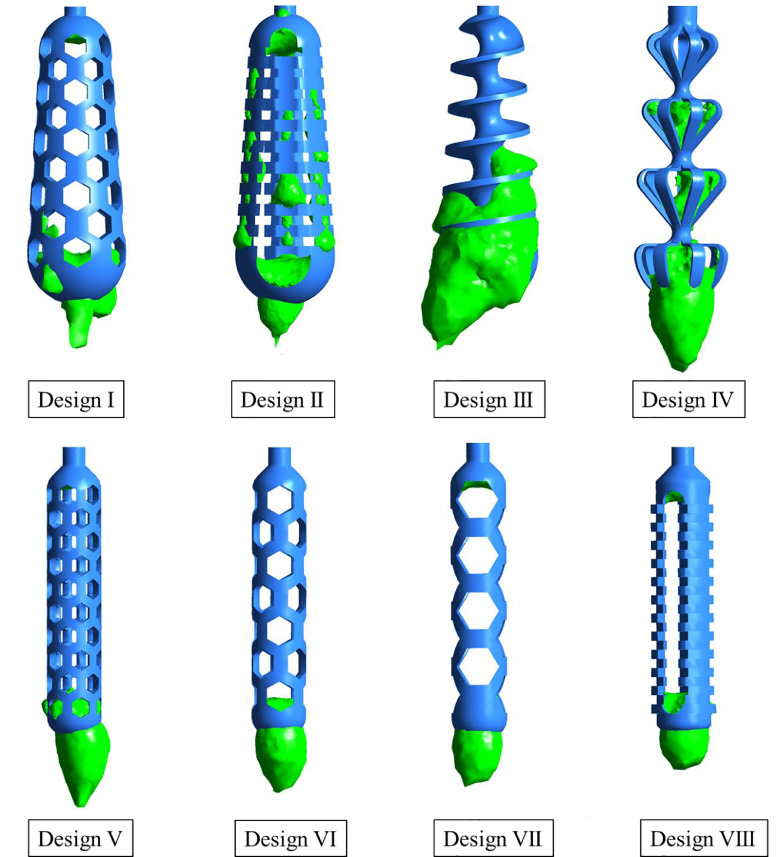

The focus of the present study is to provide a numerical platform to evaluate the efficacy of 3D printed NP swabs on the sample collection/retention metrics. We investigated the 3D designs geometries of the NP swabs that have received significant attention and are based on the open-source 3D printed swab consortium [17]. Fig. 1 shows the heads of the different designs of 3D printed NP swabs. It is noteworthy to mention that designs I to VIII are developed at the FAMES Lab of Indiana University, IX-X are Abiogenix designs, XI-XIII are Fanthom designs, XIV is USF Health design and XV-XIX are Wyss designs. Notably, in this study, we included the open-source designs of 3D printed NP swabs for which the CAD files were available and these include designs of Harvard's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, University of Washington, Stanford University, MIT and the United States Army, and Indiana University [8,9,16,17]. Apart from these designs available in the literature, we also report and consider three novel geometric designs of 3D printed NP swabs developed by our research group that met the FDA-approved design requirements and are shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 1.

Geometric designs of the heads of 3D printed NP swabs available in the literature. I–VIII: FAMES Lab designs, IX–X: Abiogenix designs, XI–XIII: Fanthom designs, XIV: USF Health design, XV–XIX: Wyss designs. (This figure is reproduced with permission from [9]).

Fig. 2.

Geometric designs of the heads of 3D printed NP swabs proposed by our research group.

2.2. CFD based model

During preclinical testing of the NP swabs, the most common method to quantify the collection efficiency is the dipping test. In this procedure, the fluid absorbed by the swab is evaluated by dipping the head of a swab in the centrifuge tube filled with water or fluid that mimics the human mucus [9,15,21]. The tube is weighted both before and after removing the swab. The weight of absorbed fluid by the swab is then calculated as a difference between the tube weight before immersion and after removal of the swab. In the present study, we develop a numerical model to simulate this dipping test procedure for quantifying the collection efficiency of 3D printed geometric designs of NP swabs. Importantly, a multiphase flow model has been developed using the Finite Volume Method (FVM) embedded in ANSYS – FLUENT® code version 2019R2 whereby the geometric input of STEP file was created by Autodesk® Fusion 360. The liquid-air interface has been tracked using the volume of fluid (VOF) method [22].

The governing equations for transient, incompressible, laminar flow are the coupled momentum and continuity equations that are shared by the liquid and gas phases and are given by:

| (1) |

where ρ is the density, u is the velocity vector, p is the pressure, I is the identity matrix, µ is the viscosity, ∇u is the velocity-gradient tensor, superscript T is the transpose of a tensor, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and F s is the surface tension force acting at the liquid-air interface. The momentum equation is dependent on the ρ and µ of the mixture by volume-fraction averaging as:

| (2) |

where the indices l and g denote the liquid and gas phases, respectively. ϕ is the volume-fraction (0 ≤ ϕ ≤ 1) that is governed by the simple advection equation as:

| (3) |

ϕ = 0 and 1 corresponding to regions accommodating only one phase, and any value between 0 and 1 represents the free liquid-air interface. The movement of this free surface for the two-phase flow is represented using the geometric reconstruction (piecewise-linear scheme) [23]. The surface tension force (F s) acting at the liquid-air interface has been evaluated using the continuum surface force (CSF) model proposed by Brackbill et al. [24] as:

| (4) |

where σ is the surface tension coefficient, ρ is the volume-averaged density computed using Eq. (2), ρ l and ρ g are the liquid and gas densities, respectively, κ is the radius of curvature and is expressed in terms of the unit normal vector n as:

| (5) |

When coupled with the Navier–Stokes equations, the volume fraction ϕ (x, y, z, t) is used to determine the position of the free boundary interface using Eq. (3). Fig. 3 presents the schematic of the computational model developed for conducting the dip test of the NP swab. As shown in Fig. 3, during the dip test, the head of the nasopharyngeal swab is inserted into the tube filled with fluid along the center axis to avoid any contact with the tube walls. After a few seconds, the swab is gently withdrawn vertically upward and the decrease in the weight of fluid in the tube represents the amount of fluid absorbed by the swab. Thus, from a numerical perspective, this problem involves a fluid-structure interaction (FSI) with a two-phase flow where a rigid solid (swab) moves in a quiescent fluid (comprising of water and air). A multiphase (VOF) method has been used to solve the transient problem of fluid captured by the moving swab. A grid independence study has been performed to determine the optimal number of mesh elements that would result in a mesh-independent solution. The mesh refinements were carried out using the capture volume convergence criterion, i.e. mesh was progressively refined until the absolute error for capture volume is less than 0.1% compared to the previous mesh size. All simulations have been conducted on a Dell Precision 7920 Tower workstation with 96 GB RAM and 2.20 GHz Intel® Xeon® processors.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of the dip test of the NP swab.

2.3. Design of experiments

A design of experiments based case study has been reported to quantify the influence of different geometric design parameters on the collection efficiency of the 3D printed NP swabs. More precisely, we used Taguchi's method which provides an economical and robust alternative to the full factorial design approach that explores all the possible combinations to identify relations of design parameters. Taguchi's method has been widely applied in the manufacturing system, thermal and fluid flow, mechanical component design, biological sciences, process optimization, etc. [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. The NP design for performing the Taguchi analysis and the selected factors has been shown in Fig. 4 . In particular, three controllable factors (k) were considered, viz., ring/rod thickness, inner rod diameter, and spacing. The selected factors have been further divided into three levels (N) (i.e. low, medium, and high), as presented in Table 1 . Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array has been used for investigating interactions of the above-mentioned parameters at different levels that only require conducting 9 experiments (simulations), as presented in Table 2 . According to Taguchi's philosophy, a statistical measure of the quality characteristics is evaluated by the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio. Importantly, the output (or response) of each Taguchi experiment is converted into the S/N ratio to measure the quality characteristics deviating from the desired values. Further, depending on the desired output, three approaches are available: smaller-the-better, larger-the-better, and nominal-the-better. Since the present study involves maximizing the capture volume, thus, the larger-the-better category has been implemented whereby the S/N ratio is given by:

| (6) |

where Vi represents the collection volume of the experiment (simulation) i in Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array, n is the number of values in each experimental condition (refer to Table 2). The results of the response variable (i.e., collection volume) have been obtained utilizing ANSYS – FLUENT® software. The obtained response for each experiment number of the Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array has been further analyzed in Minitab® statistical software. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) statistical method has also been used to quantify the ranking and percentage contribution of each controllable factor on the collection volume of the NP swab.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of NP swab (highlighting selected design parameters) used for performing design of experiment analysis.

Table 1.

Controllable design parameters and their corresponding levels.

| Parameter level | Ring/rod thickness (mm) | Inner rod diameter (mm) | Spacing (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (low) | 0.3 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Level 2 (medium) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Level 3 (high) | 0.5 | 1.1 | 2 |

Table 2.

Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array.

| Exp. No. | Ring/rod thickness (mm) | Inner rod diameter (mm) | Spacing (mm) | Capture volume (µl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.6 | 57.5730 |

| 2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 42.8105 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2 | 29.1186 |

| 4 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 47.8139 |

| 5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2 | 35.5866 |

| 6 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 38.180 |

| 7 | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 36.740 |

| 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 47.030 |

| 9 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1 | 39.890 |

2.4. Experimental setup for dipping test

A swab dip test was utilized to measure the volume retained from each swab design after 3D printed on a Form3 (Formlabs®) with clear material. The swabs were then washed in 99% Iso-propyl for 5 minutes, dried for 20 minutes, rewashed with 99% Iso-propyl for 5 minutes and left to dry for 24 hours. The swabs were then cured without heat, only UV in a Formlab curing station to prevent deformation on the microstructures for 10 minutes. The dip test was constructed with a vial of water on an analytical scale and tared. The swab was slowly submerged to cover the head fully into the water and removed slowly; the weight displayed on the scale was recorded as the volume adhered to the swab. Fig. 5 illustrates the experimental set-up used in this study for performing the dip tests on the different NP swabs designs.

Fig. 5.

Photographic view of experimental set-up utilized to perform dip tests.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental results

The capture volume obtained for different designs of 3D printed NP swabs (presented in Figs. 1 and 2) during the dipping test has been tabulated in Table 3 . As evident from Table 3, there prevails a huge variability (between 2-120 µl) in the captured volume for different designs of 3D printed NP swabs. Design II outperforms all the other designs and captures the highest volume owing to the highest head volume and heavy reliance on the surface tension to hold the fluid within the hollow reservoir of the head. A recent experimental study has reported the volume of water absorbed by four commercially available conventional swabs during dip test, viz., (i) FLOQSwabs: flocked swabs made of nylon (Copan Italia S.p.A, Italy), (ii) rayon swabs (Copan Italia S.p.A, Italy); (iii) dacron swabs (Copan Italia S.p.A, Italy); and (iv) BBL Culture Swabs: swabs composed of polyurethane foam (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) [21]. The absorbed volume of water during the dip test for these conventional NP swabs ranges between 50-150 µl [21]. It is noteworthy to mention that the experimental results presented in Table 3 for different designs of 3D printed NP swabs are also consistent with those recently reported in [9].

Table 3.

Experimental results for dip test of different designs of NP swabs.

| Design | Capture volume (µl) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 52.04 ± 10.20 |

| 2 | 120.46 ± 4.08 |

| 3 | 91.10 ± 15.28 |

| 4 | 30.56 ± 9.56 |

| 5 | 13.08 ± 2.07 |

| 6 | 25.04 ± 2.93 |

| 7 | 43.66 ± 7.06 |

| 8 | 51.76 ± 8.08 |

| 9 | 13.33 ± 0.91 |

| 10 | 10.78 ± 1.24 |

| 11 | 3.05 ± 0.73 |

| 12 | 14.38 ± 3.27 |

| 13 | 22.16 ± 2.55 |

| 14 | 22.20 ± 1.59 |

| 16 | 4.70 ± 0.95 |

| 17 | 2.86 ± 0.81 |

| 18 | 11.88 ± 3.24 |

| 19 | 43.38 ± 5.36 |

| A | 9.30 ± 2 |

| B | 45.62 ± 8.18 |

| C | 42.5± 8.11 |

3.2. CFD based numerical simulations of 3D printed designs of NP swabs

In this section, we will report the CFD based analysis of different 3D printed NP swabs in terms of their collection efficiency during the dip test. Importantly, the CFD based analysis has been conducted on the Fames Lab designs (I-VIII), Abiogenix designs (IX-X), Fanthom designs (XII-XIII), and the novel designs reported by our research group, i.e., designs (A-C). The heads of these NP swab designs have been shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The numerical results obtained for different designs of the 3D printed NP swabs using CFD based modeling have been reported in Fig. 6 . The results obtained from experimental tests have also been included in Fig. 6 to provide a direct comparison between the experimentally measured and numerically predicted values of capture volume for the designs for which we have both the CAD and STL files. As evident from Fig. 6, the numerical predictions are in good agreement with the experimental findings. This lends great confidence in the results derived from the developed CFD based model. The pictorial representation of fluid captured for different designs of 3D printed NP swabs has been presented in Figs. 7 and 8 . The performance of the considered designs can be divided into four subcategories based on their capture volume (V): (a) best (V ≥ 60 µl), (b) good (40 ≤ V < 60 µl), average (20 ≤ V < 40 µl), and (d) worst (V < 20 µl). The capture volume is maximum and exceeds 100 µl (or mg) for designs II and III. The NP swab designs that lie in the good category are designs B, VIII, VII, I and C. Designs IV, VI and XIII lie in the average category. Furthermore, the capture volume for rest of all designs is less than 20 µl (or mg). It is noteworthy to mention that the relatively higher capture volume of FAMES Lab design I-IV is directly linked to their higher head volume (> 200 mm3) enabling them to hold a higher volume of fluid. For the rest of all designs, the head volume is ≤ 100 mm3.

Fig. 6.

Comparison between experimentally measured and numerically predicted values of the capture volume for different 3D printed designs of NP swab.

Fig. 7.

Pictorial representations of the fluid retained by the NP swab designs I-VIII by the FAMES Lab.

Fig. 8.

Pictorial representations of the fluid retained by the NP swab designs IX-X by Abiogenix, XII-XIII by Fanthom, and A-C by our research group.

3.3. Case Study: Design of Experiments Approach

Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array has been utilized to indicate which design variable has the greatest influence on the collection efficiency of the 3D printed NP swab. Different experiments (simulations) associated with Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array have been tabulated in Table 2. The capture volume associated with each corresponding experiment has been computed utilizing the VOF model developed in ANSYS – FLUENT® software as presented in section 2.2. The outcome of each experiment in terms of capture volume has also been presented in Table 2. The mean effect plots for S/N ratios of three controllable parameters (i.e., ring/rod thickness, inner rod diameter, and spacing) corresponding to the associated level have been presented in Fig. 9 . As is evident from Fig. 9, the ring/rod diameter of the NP swab has a very negligible influence on the capture volume. Furthermore, the capture volume decreases with the increase of both inner rod diameter and spacing. The pictorial representation of fluid captured for different experiments of Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array during dip test has been presented in Fig. 10 . Among the 9 experiments, the maximum capture volume has been obtained for Exp. 1 (= 57.57 µl) owing to the absence of inner rod and minimum value of spacing that would have enhanced the capillary filling of the NP swabs. The minimum capture volume has been obtained for Exp. 3 (= 29.12 µl) that could be attributed to the higher level of spacing and inner rod diameter. The variation of capture volume of NP swabs for different experiments of Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array has been presented in Fig. 11 . As depicted in Fig. 11, significant variation prevails in the attained capture volume during dip test, clearly highlighting the impact of geometric design parameters on the collection efficiency of the NP swabs.

Fig. 9.

Main effects plot for S/N ratio of different controllable parameters considered in the case study.

Fig. 10.

Pictorial representations of the fluid captured by the NP swab for different geometric configurations of Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array.

Fig. 11.

Variation of capture volume of NP swabs for different experiments of Taguchi's L9 orthogonal array.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) has also been conducted to quantify the ranking and contribution of the selected controllable factors on the collection efficiency of the 3D printed NP swab. The percentage contribution of the selected controllable factors on the collection volume has been presented in Fig. 12 . As evident from Fig. 12, the spacing parameter has the highest contribution (56.17 %) on the collection efficiency of the NP swab, followed by inner rod diameter that accounts for 33.64 %. The ring/rod thickness has the least effect on the collection efficiency and accounts for just 2.2 %. The pooled error has a contribution of 7.99 % and accounts for the combined factors or interaction effects with low magnitude during the design of experiment analysis.

Fig. 12.

Evaluation of percentage contribution of different controllable parameters on the collection efficiency of the NP swab using ANOVA.

4. Limitation and Future Scope

In the present study, we reported a numerical framework to evaluate/compare the collection efficiency of different 3D printed designs of NP swabs during the pre-clinical stage. The dip test procedure was computationally simulated to quantify the fluid absorption on the NP swabs. However, the reported analysis has several limitations. First and foremost is the basic assumption that the collection efficiency of the NP swabs is only dependent on the absorption of fluid. Importantly, the release of the fluid and viral RNA recovery are the two other most important metrics that can significantly affect the efficacy of the swabs from a clinical perspective. However, for 3D printed designs made of the same material, the release and viral RNA recovery would be somehow related to the absorption of the fluid, i.e., the more the absorption of fluid on the NP swab, the more would be the probability of fluid release and RNA/protein recovery. This won't be the case for the conventional swabs made with different materials (such as Dacron, polyurethane foam, rayon, or nylon). Another major limitation of this study is the consideration of water as a fluid for testing the absorption on the NP swabs. From a clinical perspective, the fluid collected during the COVID-19 testing from the nasopharynx is mucus, not water. However, the dip tests utilizing water are the most commonly employed technique for pre-clinical screening of the swabs based on fluid absorption. The proposed numerical framework can be easily extended to compare the collection efficiency of the 3D printed NP swabs utilizing mucus, which is a non-Newtonian fluid that displays shear-thinning characteristics. Furthermore, the proposed framework can also be extended to simulate the actual clinical procedure of COVID-19 testing for quantifying the mucus collection on the different designs of the 3D printed NP swabs utilizing patient-specific nasal anatomical models that can be generated from CT or MRI scans. These patient-specific models can be further utilized to evaluate and include the effect of other critical metrics, such as fluids release, virus recovery, etc. Thus, future studies are warranted for integrating these critical clinical aspects in the proposed numerical framework that would significantly assist in improving and optimizing the designs of the 3D printed NP swabs.

5. Conclusion

We have presented a CFD based model to quantify the capture volume of the 3D printed designs of the NP swabs. A comparative analysis has been conducted to evaluate the collection efficiency of the 3D printed NP swabs available in the literature. The numerical validation of the CFD model has been done by conducting the dip test experiments on 3D printed geometric designs in our lab. Design of experiments based case study has also been presented to compute the influence and contribution of different design parameters on the collection efficiency of NP swabs. Although the present study is based on modeling the dip test experiments with water, future studies will be based on modeling the mucus as a non-Newtonian viscoelastic fluid. We believe that the proposed computational framework would provide a low-cost and fast alternative to quantify the collection efficiency of the 3D printed geometric designs of NP swabs. This would not only assist in improving the performance of the existing designs of 3D printed swabs to have comparable efficacy with the conventional swabs but would also provide a route to future innovations in novel biomedical products.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Prof. Alexander Gumennik and Dr. Louis A. van der Elst, Fibers and Additive Manufacturing Enabled Systems (FAMES) Laboratory, Indiana University, USA for sharing the CAD/STL files of the different 3D printed NP swabs shown in Fig. 1. SS and GN acknowledge support from NSERC Alliance COVID-19 554501 - 20.

References

- 1.Martin A., et al. Socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on household consumption and poverty. Economics of disasters and climate change. 2020;4(3):453–479. doi: 10.1007/s41885-020-00070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicole M., et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus and covid-19 pandemic: A review. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.JHU.edu. [cited 2022 Feb 4]; Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 4.Ford J., et al. A 3D-printed nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 diagnostic testing. 3D printing in medicine. 2020;6(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s41205-020-00076-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chee J., et al. Using 3D-printed nose models in nasopharyngeal swab training. Oral Oncology. 2021;113 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S., Prakash C., Ramakrishna S. Three-dimensional printing in the fight against novel virus COVID-19: Technology helping society during an infectious disease pandemic. Technology in Society. 2020;62 doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams E., et al. Pandemic printing: a novel 3D-printed swab for detecting SARS-CoV-2. Medical Journal of Australia. 2020;213(6):276–279. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callahan C.J., et al. Open development and clinical validation of multiple 3D-printed nasopharyngeal collection swabs: rapid resolution of a critical COVID-19 testing bottleneck. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2020;58(8) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00876-20. e00876-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Elst L.A., et al. Rapid Fabrication of Sterile Medical Nasopharyngeal Swabs by Stereolithography for Widespread Testing in a Pandemic. Advanced engineering materials. 2020;22(11) doi: 10.1002/adem.202000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker S.J., et al. 3-Dimensional Printed Alternative to the Standard Synthetic Flocked Nasopharyngeal Swabs Used for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Testing. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;73(9):e3027–e3032. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandjean Lapierre S., et al. Clinical evaluation of in-house-produced 3D-printed nasopharyngeal swabs for covid-19 testing. Viruses. 2021;13(9):1752. doi: 10.3390/v13091752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta K., Bellino P.M., Charness M.E. Adverse effects of nasopharyngeal swabs: Three-dimensional printed versus commercial swabs. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2021;42(5):641–642. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manoj A., et al. 3D printing of nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 diagnose: Past and current trends. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021;44:1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oland G., Garner O., de St Maurice A. Prospective clinical validation of 3D printed nasopharyngeal swabs for diagnosis of COVID-19. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2021;99(3) doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tay J.K., et al. Design and clinical validation of a 3D-printed nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 testing. MedRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tooker A., et al. Performance of three-dimensional printed nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 testing. Mrs Bulletin. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1557/s43577-021-00170-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnaout, R.Covidswab. Github.2020 [cited 2021 June 15]; Available from: https://github.com/rarnaout/Covidswab.

- 18.Arjunan A., et al. 3D printed auxetic nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 sample collection. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2021;114 doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y., Mercader A., Lueth T.C. Design of 3D-printable nasopharyngeal swabs in Matlab for COVID-19 testing. Transactions on Additive Manufacturing Meets Medicine. 2020;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S., et al. Design of a low-cost miniature robot to assist the COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab sampling. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics. 2020;3(1):289–293. doi: 10.1109/TMRB.2020.3036461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zasada A.A., et al. Vol. 10. AMB Express; 2020. pp. 1–6. (The influence of a swab type on the results of point-of-care tests). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirt C.W., Nichols B.D. Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries. Journal of computational physics. 1981;39(1):201–225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filali A., Khezzar L., Mitsoulis E. Some experiences with the numerical simulation of Newtonian and Bingham fluids in dip coating. Computers & Fluids. 2013;82:110–121. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brackbill J.U., Kothe D.B., Zemach C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. Journal of computational physics. 1992;100(2):335–354. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asfaw B.A., et al. Optimization of compound-specific chlorine stable isotope analysis of chloroform using the Taguchi design of experiments. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2020;34(23):e8922. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis R., John P. Application of Taguchi-based design of experiments for industrial chemical processes. Statistical approaches with emphasis on design of experiments applied to chemical processes. 2018:137. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamil M., Ng E.Y.K. Ranking of parameters in bioheat transfer using Taguchi analysis. International Journal of Thermal Sciences. 2013;63:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalid M., Peng Q. Investigation of printing parameters of Additive Manufacturing process for sustainability using Design of Experiments. Journal of Mechanical Design. 2021;143(3) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadeghifam A.N., et al. Assessment of the building components in the energy efficient design of tropical residential buildings: An application of BIM and statistical Taguchi method. Energy. 2019;188 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S., Repaka R. Parametric sensitivity analysis of critical factors affecting the thermal damage during RFA of breast tumor. International Journal of Thermal Sciences. 2018;124:366–374. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S., Repaka R., Al-Jumaily A. Sensitivity analysis of critical parameters affecting the efficacy of microwave ablation using Taguchi method. International Journal of RF and Microwave Computer-Aided Engineering. 2019;29(4):e21581. [Google Scholar]