Abstract

Taking appropriate strategies in response to the COVID-19 crisis has presented significant challenges to the hospitality industry. Based on situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), this study aims to examine how the hotel industry has adopted strategies in shaping customers' experience and satisfaction. A mixed-method approach was employed by analysing 6556 COVID-19 related online reviews. The qualitative findings suggest that ‘rebuild strategies’ dominated most hotels' response to the COVID-19 crisis while the quantitative findings confirm the direct impact of affective evaluation and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction. The results further reveal that hotels' crisis response strategies moderate the effects of affective evaluation and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction. The study contributes to new knowledge on health-related crisis management and expands the application of SCCT in tourism research.

Keywords: Situational crisis communication theory, COVID-19, Customer satisfaction, Crisis response strategy, Online reviews

1. Introduction

The global tourism and hospitality industry has been significantly affected by the unprecedented global outbreak of COVID-19. The hospitality industry has been one of the hardest-hit industries. The American hotel industry has already lost over $38 billion in room revenue since the public health crisis began escalating in mid-February 2020 (AHLA, 2020). Coldwell Banker Richard Ellis (CBRE) projected that the annual occupancy level was 41% for 2020, which could be the lowest on record (Simon, 2020; Apr 24). To handle the health-related crisis, hotels have started taking measures, including furloughs, hotel closures, and staff reduction. Furthermore, hotels have implemented cancellation or rebooking policies and enhanced cleaning protocols to provide a safe and secure environment for employees and guests.

These measures are responding to the COVID-19 outbreak since the negative impacts of the health-related crisis on the hotel industry include not only a decline in revenue margins but also damage to organizational reputation and the downturn of the entire market (Ritchie et al., 2011). “What management says and does after a crisis” to protect organizational reputation refers to a ‘crisis response strategy’ (Coombs, 2007, p. 170). An effective crisis response strategy can help protect an organization's reputational assets and reduce adverse consequences, while an inappropriate response to crises can severely damage its reputation and performance (Ma & Zhan, 2016). Ki and Nekmat (2014) reported that 60.7% of Fortune 500 companies use inappropriate crisis response strategies. As such, a growing number of studies have explored how to best formulate an effective crisis response strategy; however, a consensus has yet to be reached (Dutta & Pullig, 2011; Singh et al., 2020). For example, Dutta and Pullig (2011) noted that the relative effectiveness of crisis response strategies relies on the nature of the crisis, and denial is the most ineffective response strategy in any type of crisis, while Singh et al. (2020) found that denial is the most effective strategy in preventable crises. Among all the studies on effective crisis response strategies, one of the dominant theoretical frameworks is situational crisis communication theory (SCCT). SCCT provides guidance to protect organizational reputation, suggesting that the crisis response strategy used by an organization should match the responsibility attributed to the organization. Nevertheless, extant empirical studies based on SCCT report inconsistent findings regarding the effectiveness of matching crisis response strategies to attributed responsibility, indicating a need for further investigation (Ma & Zhan, 2016).

Crisis management studies in tourism and hospitality have developed to include different types of crises, such as financial crises (Papatheodorou et al., 2010), health-related crises (Liu et al., 2015), and data breaches (Chen & Jai, 2019). These studies focused on the recovery and sustainability of the industry from a macro perspective; however, relatively few studies have investigated individual customers' emotional experiences (Qi & Li, 2021). SCCT contends that emotional experiences are a critical output in a crisis and will influence an individual's behavioural intention (Qi & Li, 2021). However, extant studies remain limited in fully understanding customers' cognitive and emotional experiences and their attitudes during COVID-19 in light of crisis management (Qi & Li, 2021). In addition, the mechanism of how crisis response strategies shape customers' consumption experiences and satisfaction remains unclear. Underpinned by situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), this study attempts to answer two research questions:

-

(1)

What crisis response strategies have been adopted by hotels during the COVID-19 outbreak?

-

(2)

As a moderator, how does a crisis response strategy influence the relationships among hotel customers' affective evaluation, cognitive effort, and satisfaction?

This study has made three significant contributions to the existing crisis management literature in tourism. First, given that extant crisis management studies have predominantly explored crisis response strategies from the organizational perspective, this study innovates in identifying hotels' crisis response strategies from the customer's perspective and highlighting the individual's service experience and attitudes towards crisis response strategies during COVID-19. Second, despite the critical role of crisis response strategies in crisis management (Coombs & Holladay, 2009; Liu et al., 2015), the moderating effect of the crisis response strategy has not been clearly understood in the literature when predicting customer satisfaction. Our study addressed this gap by empirically identifying the impacts of different crisis response strategies on the relationships between cognitive effort/affective evaluation and customer satisfaction. These empirical insights advance our knowledge on the links between affective evaluation/cognitive effort and customer satisfaction. Third, this study challenges the conventional proposition that the organization should match its crisis response strategies to the crisis type (Coombs, 2007). Specifically, our study demonstrates that even though hotels are victims of the COVID-19 pandemic, more accommodative strategies, such as rebuild, are more effective than denial strategies in protecting hotels' reputations and eWoM. Our study highlights that when matching the response strategy to the crisis, organizations should not only consider the level of responsibility for the crisis but also attach importance to customers' expectations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Health-related crises in the tourism and hospitality industry

Tourism is one of the most susceptible sectors to crises and disasters, as it is impacted by many external factors (Pine & McKercher, 2004). The impact of crises on tourism can be complex because they are based on the type, time duration, and scale of the crises (Backer & Ritchie, 2017). Among the numerous studies on different types of crises in tourism, health-related crises have received relatively less academic attention, while they cause significant damage to the hospitality industry (Novelli et al., 2018). Several health-related crises in the last few decades have affected the hospitality industry, including SARS, avian flu, Ebola, H1N1, and most recently COVID-19. The extant literature on health-related crises mainly focuses on examining the impacts of these crises (Chien & Law, 2003; Choe et al., 2021; Kuo et al., 2008), tourists' perceived travel risk (Cahyanto et al., 2016; Bae & Chang, 2021), tourists' expectations and preferences (Hu et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2005), tourists’ behavioural intentions (Bae & Chang, 2021; Lee et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2021), organizational crisis communication (Liu et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2021), and recovery strategies (Henderson & Ng, 2004; Hidalgo et al., 2022; Novelli et al., 2018). Table 1 provides an overview of the main studies on health-related crises in tourism and hospitality.

Table 1.

Studies on health-related crises in tourism and hospitality.

| Author and year | Health-related crisis | Key findings |

|---|---|---|

| Chien and Law (2003) | SARS | The impacts of SARS on the hospitality industry in Hong Kong may be enduring, and the government's intervention and support play a crucial role in the recovery process |

| Henderson and Ng (2004) | SARS | The study provided a set of guidelines for the hospitality industry to cope with health-related crises |

| Wen et al. (2005) | SARS | Tourists are very sensitive to crises, resulting in a long-term effect of SARS on tourists' travel preferences and safety awareness |

| Kuo et al. (2008) | SARS and avian flu | Tourism demand in SARS-infected countries is significantly affected by the number of infected cases, while avian flu-infected countries are not |

| Lee et al. (2012) | H1N1 | Personal nonpharmaceutical interventions fully mediate the relationship between tourists' perception of H1N1 and their behavioural intention, while tourists' desire, perceived behavioural control, and frequency of past behaviour directly impact their behavioural intention |

| Liu et al. (2015) | Bed bugs | Bolstering and enhancing are the predominant crisis response strategies used by hotels during the bed bug crisis, and hotels' response behaviour is related to customers' online ratings |

| Cahyanto et al. (2016) | Ebola | Tourists' perceived susceptibility and risk, as well as their self-efficacy and subjective knowledge, have significant impacts on domestic travel avoidance |

| Novelli et al. (2018) | Ebola | Crisis preparation and planning are important for tourism destinations, and it is also essential to pay attention to crisis communication and tourists' risk perception |

| Choe et al. (2021) | MERS | The study estimated the concrete impacts of MERS on the inbound tourism market in South Korea |

| Hu et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Hotel customers' expectations on social distancing and hygiene have increased during COVID-19, while some other attributes less related to safety are perceived as less important |

| Shin et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Hotels' corporate social responsibility negatively impacts organizational performance and future customers' booking behaviours |

| Hidalgo et al. (2022) | COVID-19 | Effective measures in hotel recovery include labour actions, innovation, and differentiation strategies, as well as market reorientation strategies and official information |

In addition, tourism itself is regarded as a potential vector of health-related crises because as an industry, it brings people into contact with one another from a diverse range of geographical areas (Kuo et al., 2008). Numerous pandemic outbreaks have confirmed the close relationship between tourism and health-related crises (Kuo et al., 2008). For hotels, the reduction in leisure and business tourists negatively impacts hotels' revenue, while enhanced hygiene standards and fee-free cancellations increase hotels' expenses (Sharma et al., 2021). Some recent studies focused on crisis management in the hotel industry in the context of health-related crises (Hidalgo et al., 2022; Lai & Wong, 2020; Wong et al., 2021). However, these studies discussed crisis management broadly from a hotel's perspective, with little attention on the effects of hotels' crisis response strategies on customers' experiences. Therefore, a timely study on how crisis response practices moderate customers' experiences can provide valuable insights for health-related crisis management in tourism and hospitality (Lai & Wong, 2020).

2.2. Crisis response strategy and SCCT

A crisis response strategy refers to “what management says and does after a crisis” to reduce negative affect and avoid undesirable intentions (Coombs, 2007, p. 170). When a crisis occurs, an organization can use crisis response strategies to protect its organizational reputation (Coombs, 2007). Research related to crisis response strategy originated from corporate apologia, which is defined as “a communicative effort to defend the corporation against reputation/character attacks” (Coombs et al., 2010, p. 338). Ware and Linkugel (1973) identified four self-defence strategies under ‘apologia’, including denial, bolstering, differentiation, and transcendence. Benoit (1994) then proposed the image restoration theory, consisting of five strategies: denial, evading responsibility, reducing the offensiveness of the act, taking corrective action, and mortification. Additionally, more strategies have been identified in situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), a primary theoretical framework used to guide crisis response strategies (Coombs et al., 2010). SCCT was developed based on attribution theory and image repair theory (Coombs, 2018) to connect crisis response strategies and different types of crises. At the early stage, Coombs (1995) created a decision tree for crisis managers, with recommended crisis response strategies based on crisis types. Coombs (1998) classified crisis response strategies into 7 categories. The title SCCT was first used in Coombs and Holladay's (2002) work, which examined the key assumption of SCCT and grouped 13 crisis types into three clusters: victim, accidental, and preventable. Further development and revisions to SCCT focused on the conceptualization and categories of crisis types and crisis response strategies (Coombs, 2018).

SCCT provides crisis managers with recommendations for matching crisis response strategies to different crisis types to protect organizational reputation more effectively (Coombs, 2007). One proposition of SCCT is that the more crisis responsibility stakeholders attribute to an organization, the more damage the crisis inflicts upon its reputation (Coombs, 2018). Based on the amount of crisis responsibility attributed to the organization by the stakeholders, SCCT categorizes crises into three groups: victim, accidental, and preventable (Coombs, 2007). Another proposition of SCCT is that organizations should match their crisis response strategies with the extent of their responsibility in a given crisis (Coombs, 2018). SCCT provides three groups of primary response strategies to organizations: denial, diminish, and rebuild (Coombs, 2007). In addition to matching the crisis type with a single crisis response strategy, it is advised to match the crisis type with a combination of several crisis response strategies from the same strategy group (Benoit, 1994; Coombs, 2007). The interaction between crisis types and crisis response strategies is summarized in Table 2 . Notably, the criticisms of SCCT are mostly related to the abovementioned proposition (Jin & Liu, 2010; Wang et al., 2021). These criticisms argue that SCCT ignores the influence of social media crisis communication, which means that other stakeholders cannot attribute responsibility to the organization accurately based on the complex and tendentious information generated on social media (Jin & Liu, 2010; Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, it is difficult for the organization to determine an effective response strategy without accurately capturing the level of responsibility attributed to other stakeholders. In response to these criticisms, Coombs (2018) made revisions to SCCT by extending SCCT to the precrisis phase and suggesting that organizations be cautious with the social media they select to deliver information. Despite the criticisms, SCCT has been widely recognized as one of the dominant theories in organizational crisis communication research and can provide a theoretical foundation for the current study (Coombs, 2018).

Table 2.

Crisis types and crisis response strategies (Coombs, 2007).

| Crisis type | Description of crisis type | Recommended crisis response strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Victim of crisis | Crises driven by external forces beyond organizational control or intent, and weak responsibility is attributed to the organization | Denial (e.g., attacking the accuser, denial, and scapegoating) |

| Accidental crisis | Crises that the organization has little intention and/or ability to prevent, in which a certain but low responsibility is attributed to the organization | Diminish (e.g., excuse and justification) |

| Preventable crisis | Crises that can be highly attributed to an organization's action or inaction | Rebuild (e.g., apology and compensation) |

A majority of studies have empirically supported the propositions that SCCT makes (Coombs & Holladay, 1996; Triantafillidou & Yannas, 2020). In an experimental study, Coombs and Holladay (1996) found that organizational reputation benefits when diminish strategies are matched with accidental crises and when rebuild strategies are used to cope with preventable crises. A study by Triantafillidou and Yannas (2020) also lent support to SCCT by finding that rebuild strategies are most effective in handling racially charged crises, which typically are preventable crises. However, some other studies reported inconsistent findings regarding the interactions between crisis types and response strategies (Ma & Zhan, 2016; Singh et al., 2020; Verhoeven et al., 2012). For example, Verhoeven et al. (2012) found that apology is ineffective both in preventable and accidental crises. Ma and Zhan (2016) further argued that rebuild strategies are not always effective in preventable crises since acknowledging responsibility is viewed as confirmation of the organization's incompetence, which may lead to stronger resistance from consumers. Similarly, an experiment-based study by Singh et al. (2020) also challenged SCCT by suggesting that adopting rebuild strategies in a preventable crisis may lead to a backlash. In the hotel context, several studies have applied SCCT to investigate the effects of different crises and hotels' crisis response strategies on their reputation and customers' perception (Chen & Jai, 2019; Liu et al., 2015; Kapuściński et al., 2021). Liu et al. (2015) found that bolstering and enhancing are the major reputation management strategies that hotels employ to address preventable health-related crises such as bed bugs. Studying the intensifying data breach crises in the hospitality industry, Chen and Jai (2019) found that the level of responsibility customers attribute to a hotel negatively influences customers' trust and revisit intention. They also suggested the importance of proactive disclosure strategies, which may decrease customers' negative perceptions towards the hotel in a data breach crisis. Based on the propositions of SCCT, Kapuściński et al. (2021) found that when hotels use an apology strategy in a preventable crisis, the tone of the apology has a positive effect on organizational attractiveness through the mediator variable account acceptance.

2.3. Affective evaluation and cognitive effort as satisfaction drivers

Customer satisfaction can be defined as an evaluation based on a comparison between customers' actual experiences of products and services and their initial expectations (Oliver, 1980). Customers are satisfied when the products and services meet or exceed their expectations. Given customer satisfaction's critical role in influencing organizational performance and customers' postpurchase behaviour (e.g., revisit intention and loyalty), a large amount of academic attention has been given to customer satisfaction in tourism and hospitality (Deng et al., 2013; Poon & Low, 2005; Zhao et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). Many previous studies have used traditional survey-based approaches to examine the determinants and dimensions of hotel customers' satisfaction (Deng et al., 2013; Poon & Low, 2005). In the last decade, an emerging stream of research has sought to understand hotel customers' satisfaction through online reviews and ratings (Lee et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). For example, Zhao et al. (2019) used online reviews from Tripadvisor.com to investigate the effects of the technical attributes of online reviews and reviewers' involvement on customer satisfaction. The advantages of studying online reviews are that rating scores can directly show overall customer satisfaction, while review texts can reflect customers' cognitive and affective evaluations of products and services (Zhao et al., 2019). According to the tourist satisfaction model proposed by Del Bosque and Martín (2008), both the cognitive system and emotional states are critical elements in the satisfaction formation process. The level of cognitive effort and affective evaluation reflected in the reviews show whether customers' expectations are matched and whether they are satisfied with the actual experience (Lee et al., 2019). Since the outbreak of COVID-19 has altered hotel customers' expectations (Hu et al., 2021), it is a critical time to re-examine hotel customers' satisfaction during the pandemic by elucidating their affective evaluation and cognitive effort as reflected in online reviews.

Affective evaluation is an important factor for understanding customers' experiences and behaviour intentions when studying online reviews (Lee et al., 2019). Affective evaluation refers to customers' emotional responses to their experiences of products and services (Yin et al., 2014). They have either positive or negative affective evaluations of a product or service during the consumption process (Torres & Ronzoni, 2018). To gain a holistic understanding of customers' emotional responses, both positive and negative affects should be investigated (Ou & Verhoef, 2017). Previous hospitality studies have examined the effects of both positive and negative affects on customer satisfaction through a sentiment mining approach using online reviews (Lee et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). Based on online reviews collected from TripAdvisor.com, Lee et al. (2019) found that both positive affect and negative affect are significantly related to hotel customers' satisfaction. The study on peer-to-peer accommodation by Zhu et al. (2020) also suggested that Airbnb guests' positive and negative sentiments are significant predictors of online rating scores. While these studies provide insights into the link between positive and negative affects and satisfaction, crises can inevitably change the dynamics (Yin et al., 2014). Therefore, this study attempts to simultaneously examine the impact of positive affect and negative affect on customer satisfaction during a once-in-a-century global pandemic. We argue that hotel customers’ positive affect leads to higher ratings, while negative affect leads to lower ratings. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1a

Positive affect is positively associated with customer satisfaction.

H1b

Negative affect is negatively associated with customer satisfaction.

Cognitive effort refers to a typical personal cognitive capacity and psychological energy extended on a task (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Previous studies have widely confirmed that cognitive effort is costly in psychic energy and resources, and people have limited cognitive resources (Cai & Chi, 2018; Garbarino & Edell, 1997). Therefore, customers allocate cognitive resources judiciously and tend to conserve their cognitive effort in decision-making and information processing (Garbarino & Edell, 1997). Customers' cognitive effort reflected in online reviews can be explained by the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), a dual-route theory suggesting that the level of involvement predicts an individual's attitude formation (Park et al., 2007; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Customer involvement will be higher if the issue is highly personally relevant (Petty et al., 1983). According to attribution theory, when customers have a negative experience, they are more likely to attribute it internally and be highly involved (Park et al., 2007). Thus, customers are motivated to devote more cognitive effort to describing the negative aspects of the hotel in their online reviews when they are unsatisfied with the negative experience (Zhao et al., 2019). Prior literature also provides empirical support for the negative relationship between cognitive effort and satisfaction (Cai & Chi, 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Lee et al. (2019) found that customers who have negative hotel experiences are inclined to allocate more cognitive effort to writing online reviews, resulting in lower review rating scores. The length of the review can reflect the cognitive effort by the reviewer (Ma et al., 2013). Longer reviews have been found to be negatively associated with customer satisfaction (Zhao et al., 2019). Cai and Chi (2018) also found that restaurant customers' cognitive effort has a significant negative effect on their “satisfaction with the complaint” through affective effort. In addition, the information presented in negative reviews has been found to be more persuasive and informative than in positive and neutral reviews (Filieri et al., 2019; Xu & Li, 2016). When customers are unsatisfied, they tend to use more words and sentences to describe their unsatisfied experiences in detail so that their reviews can be more persuasive (Xu & Li, 2016; Zhao et al., 2019). Thus, logic and analytical words such as because, therefore, and think, which reflect the reviewers' cognitive effort, tend to be used more frequently in negative reviews (Li et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2013). Therefore, we argue that hotel customers tend to give a lower rating when they invest more cognitive effort in their online reviews. The following hypothesis is presented:

H1c

Cognitive effort is negatively associated with customer satisfaction.

2.4. The moderating effect of the crisis response strategy

The important role of crisis response strategy in organizational reputation recovery has been widely examined (Coombs, 2018; Coombs & Holladay, 2009). Organizations adopt crisis response strategies to alleviate stakeholders' negative affect and to prevent negative behavioural intentions such as low satisfaction (Coombs, 2007). The extant literature has also discussed how hotels' crisis response strategies shape customers' attitudes and behaviour intentions under different types of crises (Chen & Jai, 2019; Liu et al., 2015). Liu et al. (2015) suggested that hotels' crisis response behaviour is an important factor influencing customer satisfaction. In addition, research shows that various crisis response strategies have different impacts on customers' experience and satisfaction (Chen & Jai, 2019; Liu et al., 2018). Previous studies have found that customers' affective evaluations and cognitive efforts towards hotel services play a significant role in predicting customer satisfaction (Lee et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). In fact, the relationships between affective evaluation/cognitive effect and customer satisfaction are subject to the hotel's crisis response strategy, which affects the intensity of the aforementioned relationships.

Online reviews and ratings represent hotel customers' satisfaction when evaluating services and products in the hotel. Since hotel customers' affection and cognition can be motivated by their experiences with hotels' response strategies in crisis, customers with experiences of highly accommodative strategies adopted by hotels are more inclined to express more positive affection and hence result in high online ratings of hotels. In other words, the relationship between positive affect and customer satisfaction will be enhanced by highly accommodative strategies such as free cancellation for customers. In contrast, if hotels adopt less accommodative strategies, such as denial strategies that refuse to accept customers’ demands related to the pandemic, customers are more able to have more negative affection and cognitive efforts, and this results in lower online ratings. In sum, we hypothesize that:

H2a

The relationship between positive affect and an increase in customer satisfaction is strengthened when employing a rebuild strategy compared with a denial and diminish strategy.

H2b

The relationship between negative affect and a decrease in customer satisfaction is strengthened when employing a denial strategy compared with a diminish and rebuild strategy.

H2c

The relationship between higher cognitive effort and a decrease in customer satisfaction is strengthened when employing a denial strategy compared with a diminish and rebuild strategy.

3. Research design

3.1. Data collection

Data for this study were obtained from TripAdvisor, the largest travel review platform, which offers more than 860 million reviews with an average of 463 million monthly unique visitors (TripAdvisor, 2020). A Python-based crawler was developed to collect reviews containing the keywords “COVID-19” or “coronavirus” from TripAdvisor worldwide from February to April 2020 to gain a more generalizable set of findings (Liu et al., 2015). The information collected from each review includes the review content and rating, the reviewer's contribution and the helpful votes, average rating and review number of the hotel. To ensure the reliability of the data retrieved by the crawler, we randomly selected 100 reviews to examine them manually and found that the extracted information from TripAdvisor using our self-developed crawler was accurate. Finally, a total of 8402 reviews related to “COVID-19” were obtained. Data cleaning was then performed to reduce the noise in the initial sample. Reviews that were unrelated or contained no actual comment content or missed important information were removed, resulting in 6556 reviews for further analysis.

User-generated data, including that of online reviewers, have been frequently used when accessing informants is difficult (Langer & Beckman, 2005). Our study presents practical difficulties in effectively accessing all the crisis response strategies adopted by hotels from the hotels' perspective because hotels rarely disclose their crisis response strategies on the internet publicly. In addition, the specific strategies the hotels have adopted in practice can be different from what they have disclosed. As such, the online comments from customers can collectively reflect hotels’ responses to the crisis.

Indeed, we are not alone in using consumers' perspectives in assessing organizational behaviour (e.g., Kim et al., 2016; Seo & Lee, 2021). For example, Kim et al. (2016) collected online reviews that contained the keywords “eco-friendly” or “environmentally friendly” to identify hotels' green practices, since many hotels do not publish whether they have green attributes. Therefore, we believe that exploring hotels' crisis response strategies from customers' perspectives is appropriate. Indeed, we believe this is also our methodological innovation: using consumers’ responses to infer organization responses under SCCT in tourism.

3.2. Data operationalization

A mixed-method design combining both qualitative and quantitative components was employed. In the first step, qualitative analysis was conducted using a hybrid deductive–inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006; Zhang et al., 2020). First, data were manually analysed to identify initial codes. Initial codes were then compared and discussed among all the researchers through an iterative process. Afterwards, these themes and codes were compared to the extant literature. Through a number of iterations, themes were identified by merging similar codes with existing codes or developing new codes. The thematic coding result of each review was cross-checked. The most salient and representative quotes were selected as examples to support each theme. An example of the codebook is presented in Appendix 1.

Three main themes emerged: (1) denial strategy, which means the hotel implemented less accommodative strategies and denied its responsibility for the crisis, including strategies of attacking the accuser, denial, scapegoating, and ignoring; (2) diminish strategy, which means the hotel implemented moderate accommodative strategies involving making excuses and providing justification; (3) rebuild strategy, which means the hotel implemented more accommodative strategies including rebuilding and bolstering. A total of 1115 reviews were coded as denial strategy, 140 reviews were coded as diminish strategy, and 5301 reviews were coded as rebuild strategy.

In the quantitative component, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) program was used to measure the key independent variables, including positive affect, negative affect, and cognitive efforts. Based on a text analysis module and a group of predeveloped dictionaries, the LIWC program counts words and determines the percentage comprised of different linguistic categories (e.g., emotions and cognitive process) and produces these as its output (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010). LIWC has been widely adopted in tourism and hospitality studies (Lee et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020), and its validity and reliability have been confirmed (Pennebaker et al., 2015). For this study, we obtained the percentage scores of positive affect, negative affect, and cognitive effort for each review through LIWC.

To isolate the impacts of independent variables, three sets of important control variables were included to control the review level, reviewer level, and hotel level effects. First, the review level effect was captured by the review length, as measured by the word count. Customers are more likely to post reviews with more words and sentences to describe the negative aspects of the hotel compared with their description of the positive aspects (Zhao et al., 2019). Second, the reviewer-level effect is measured by the reviewer contribution and helpful votes as proxies, reflecting the degree of involvement and expertise (Zhao et al., 2019). It is expected that reviewers with high involvement and expertise tend to be more tolerant and rate hotels in a more positive manner (Zhao et al., 2019). Third, the average rating and review number of the hotels were controlled to account for the impact of hotel-level characteristics. The average rating captures the overall reputation of a hotel, while the review number reflects the popularity (Yin et al., 2014). Existing research suggests that both the hotel's average rating and review number are significantly related to customer satisfaction (Lee et al., 2019; Torres & Singh, 2016; Yin et al., 2014). Details of each variable and its measurement are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Variable description and operationalization.

| Variable | Description | Operationalization | Notes | Words in LIWC Dictionary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review Rating | Customers' overall satisfaction score on TripAdvisor.com | Individual review rating for the hotel | Range: [1, 5] | |

| Positive Affect | LIWC output for positive emotion in a review | (# of positive emotion-related words/# of words in a review) × 100 | Range: [0, 100] | 620 (e.g., happy, care, love, joy, etc.) |

| Negative Affect | LIWC output for negative emotion in a review | (# of negative emotion-related words/# of words in a review) × 100 | Range: [0, 100] | 744 (e.g., worried, hate, annoyed, sad, nasty, ugly, etc.) |

| Cognitive Effort | LIWC output for cognitive processes in a review | (# of cognitive process-related words/# of words in a review) × 100 | Range: [0, 100] | 797 (e.g., because, think, know, should, would, maybe, never, always, but, else, etc.) |

| Crisis Response Strategy | Strategies that hotels adopted to cope with the COVID-19 outbreak | Theme coding. Denial posture = 1; Diminish posture = 2; Rebuild posture = 3 | Categorical | |

| Review Length | The length of the review | Number of words in a review | Continuous | |

| Reviewer's Contribution | Cumulative reviews of the reviewer | Number of reviews posted by the reviewer | Continuous | |

| Reviewer’ Helpful Votes | Cumulative helpful votes of the reviewer | Number of total votes received by the reviewer | Continuous | |

| Hotel's Average Rating | Average rating of the hotel | Average score of all the prior review ratings of the hotel | Range: [1, 5] | |

| Hotel's Review Number | Cumulative reviews of the hotel | Hotel's number of reviews | Continuous |

3.3. Model specification and data analysis

First, OLS regression was used to test the main effects of positive affect, negative affect, and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction. The regression model is as follows:

| (1) |

where X i consists of five control variables that may affect customer satisfaction, and ε is an error term.

Second, considering that the moderator in this study is a categorical variable with k = 3 categories, PROCESS was employed to examine the moderating effect of the crisis response strategy. The three categories of crisis response strategies were divided into three groups: (1) denial, (2) diminish, and (3) rebuild. An indicator coding approach was adopted to generate a group coding system, as shown in Table 4 . The first group, “denial”, was selected as the reference group, and two dummy variables D 1 and D 2 were constructed. In this coding system for a three-group categorical variable, D 1 = D 2 = 0 represents all samples in the (1) denial group, D 1 = 1 and D 2 = 0 represent all samples in the (2) diminish group, and D 1 = 0 and D 2 = 1 represent all samples in the (3) rebuild group. Therefore, the significance of the interaction item revealed whether the relationship between the independent variable and customer satisfaction significantly differs among these three crisis response strategies. Specifically, the interaction between the independent variable and D 1 examined the difference between the conditional effects of the independent variable on customer satisfaction with the denial and diminish conditions. Similarly, the interaction between the independent variable and D 2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of the independent variable on customer satisfaction with the denial and rebuild conditions. Given that there are three independent variables in this study, we examined the interaction effects between each independent variable and dummy variables separately, while the other two independent variables were included in the model as covariates. The three regression models for testing the moderating effects are as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where X i consists of the other two independent variables and five control variables, and ε is an error term.

Table 4.

Indicator coding of three groups (Denial as the reference group).

| Group | Indicator |

|

|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | |

| 1 Denial | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Diminish | 1 | 0 |

| 3 Rebuild | 0 | 1 |

Once a significant interaction effect was identified, simple slope tests were performed to interpret the interaction effects. Since denial was selected as the reference group, only differences between slopes of denial and diminish and between denial and rebuild were estimated. To compare the differences between the slopes of diminish and rebuild, the rebuild group was selected as the reference group. Then, the analysis was conducted again with a modified construction of D 1 and D 2 accordingly. As mentioned above, the interaction between the independent variable and D 1 examined whether the relationship between the independent variable and customer satisfaction differed significantly between the rebuild and diminish groups. The modified coding system is shown in Table 5 , and the results of the additional analyses are presented in Table 10, Table 12, Table 14.

Table 5.

Indicator coding of three groups (Rebuild as the reference group).

| Group | Indicator |

|

|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | |

| 1 Rebuild | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Diminish | 1 | 0 |

| 3 Denial | 0 | 1 |

Table 10.

Moderating effect on the relationship between positive affect and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Positive Affect (PA) | 0.3028*** | 0.0082 | 37.0064 | 0.2868 | 0.3189 |

| D1 | −1.2366*** | 0.0725 | −17.0661 | −1.3787 | −1.0945 |

| D2 | −1.4223*** | 0.0512 | −27.7816 | −1.5226 | −1.3219 |

| Interaction Items | |||||

| PE × D1 | −0.0650* | 0.03 | −2.1644 | −0.1239 | −0.0061 |

| PE × D2 | −0.1767*** | 0.0174 | −10.1372 | −0.2108 | −0.1425 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Negative Affect | −0.0925*** | 0.0103 | −8.9937 | −0.1127 | −0.0723 |

| Cognitive Effort | −0.0084* | 0.0034 | −2.4614 | −0.0151 | −0.0017 |

| Review Length | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | −0.2679 | −0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −1.3771 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 1.6093 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1246*** | 0.0223 | 5.5898 | 0.0809 | 0.1683 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000** | 0.0000 | 2.6779 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | 2.8155*** | 0.1059 | 26.5975 | 2.6079 | 3.0231 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Rebuild as the reference group.

PA × D1 and PA × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of positive affect on customer satisfaction in the rebuild and diminish conditions.

Table 12.

Moderating effect on the relationship between negative affect and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Negative Affect (NA) | −0.0209 | 0.0137 | −1.5234 | −0.0477 | 0.0060 |

| D1 | −1.8876*** | 0.1631 | −11.5706 | −2.2075 | −1.5677 |

| D2 | −2.0924*** | 0.0992 | −21.0921 | −2.2869 | −1.8978 |

| NA × D1 | −0.1147** | 0.0369 | −3.1071 | −0.1870 | −0.0423 |

| NA × D2 | −0.1776*** | 0.0222 | −8.0162 | −0.2210 | −0.1341 |

| Positive Affect | 0.2615*** | 0.0070 | 37.2184 | 0.2478 | 0.2753 |

| Cognitive Effort | −0.0138*** | 0.0034 | −4.0362 | −0.0205 | −0.0071 |

| Review Length | −0.0003** | 0.0001 | −2.8737 | −0.0005 | −0.0001 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.7555 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9917 | −0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1303*** | 0.0225 | 5.8053 | 0.0863 | 0.1744 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000* | 0.0000 | 2.3992 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | 1.9676*** | 0.1288 | 15.2718 | 1.7149 | 2.2202 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Rebuild as the reference group.

NA × D1 and NA × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of negative affect on customer satisfaction in the rebuild and diminish conditions.

Table 14.

Moderating effect on the relationship between cognitive effort and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Cognitive Effort (CE) | −0.0058 | 0.0042 | −1.3759 | −0.0142 | 0.0025 |

| D1 | −1.4172*** | 0.1491 | −9.5047 | −1.7096 | −1.1248 |

| D2 | −1.1696*** | 0.0893 | −13.0972 | −1.3447 | −0.9945 |

| CE × D1 | 0.0050 | 0.0144 | 0.3452 | −0.0233 | 0.0333 |

| CE × D2 | −0.0251** | 0.0079 | −3.1635 | −0.0407 | −0.0095 |

| Positive Affect | 0.2638*** | 0.0072 | 36.8854 | 0.2498 | 0.2778 |

| Negative Affect | −0.0937*** | 0.0105 | −8.9168 | −0.1143 | −0.0731 |

| Review Length | −0.0002 | 0.0001 | −1.7300 | −0.0003 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.7980 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 1.0120 | −0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1406*** | 0.0227 | 6.1899 | 0.0961 | 0.1851 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000* | 0.0000 | 2.3378 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | 2.0033*** | 0.1150 | 17.4243 | 1.7779 | 2.2288 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Rebuild as the reference group.

CE × D1 and CE × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of cognitive effort on customer satisfaction in the rebuild and diminish conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables included in the models. The results show that the mean score of the review ratings related to COVID-19 is 3.46, while the mean score of the average hotel review ratings was 4.232. This indicates that customer satisfaction associated with COVID-19 is relatively lower than the hotels’ overall customer satisfaction. Table 7 shows the correlations among all independent variables.

Table 6.

Variable descriptive statistics.

| Dimension | Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Satisfaction | Review Rating | 3.46 | 1.707 | 1 | 5 |

| Review Content | Positive Affect | 5.913 | 3.317 | 0.00 | 10.99 |

| Negative Affect | 1.498 | 1.403 | 0.00 | 13.51 | |

| Cognitive Effort | 9.187 | 3.568 | 0.00 | 27.50 | |

| Crisis Response Strategy | 2.34 | .908 | 1 | 3 | |

| Control Variables | Review Length | 159.26 | 133.145 | 32 | 2250 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 145.36 | 2741.697 | 1 | 126,824 | |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 31.07 | 456.032 | 0 | 21265 | |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 4.232 | .555 | 1.0 | 5.0 | |

| Hotel's Review Number | 2142.22 | 3604.959 | 1 | 43,709 |

Table 7.

Pearson correlations of independent variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Affect | |||||||

| 2. Negative Affect | −0.539** | ||||||

| 3. Cognitive Effort | −0.295** | .0237** | |||||

| 4. Review Length | −0.313** | 0.061** | 0.165** | ||||

| 5. Reviewer's Contribution | 0.019 | −0.032 | −0.033 | 0.033 | |||

| 6. Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.012 | −0.027 | −0.031 | 0.046* | 0.977** | ||

| 7. Hotel's Average Rating | 0.372** | −0.268** | −0.109** | −0.049* | −0.004 | −0.005 | |

| 8. Hotel's Review Number | −0.015 | −0.021 | −0.017 | 0.042* | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.025 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01.

4.2. Regression analysis

Table 8 presents the main effects of positive affect, negative affect and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction while controlling for the length of reviews, reviewer contribution and votes, as well as average review ratings and hotel review number. Model 1 contains only the main independent variables, and Model 2 includes five control variables. As expected, the direct effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction is positive and significant (β = 0.4240, p < .001). The strong relationship between customers’ positive affect and an increase in rating score is thus confirmed, supporting Hypothesis 1a. In contrast, negative affect (β = −0.1737, p < .001) and cognitive effort (β = −0.0233, p < .001) have a negative and significant impact on customer satisfaction. The results indicate that a lower rating score can be expected if the customer expresses more negative affect and cognitive effort in the online review. Hence, Hypotheses 1 b and 1c are supported.

Table 8.

The main effects.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | 0.4240*** | 0.4113*** |

| Negative Affect | −0.1737*** | −0.1713*** |

| Cognitive Effort | −0.0233*** | −0.0221*** |

| Review Length | −0.0003** | |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0002 | |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1595*** | |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000* | |

| R2 | 0.925 | 0.927 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.856 | 0.859 |

| R2 change | 0.856 | 0.003 |

| F change | 4479.018*** | 10.680*** |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

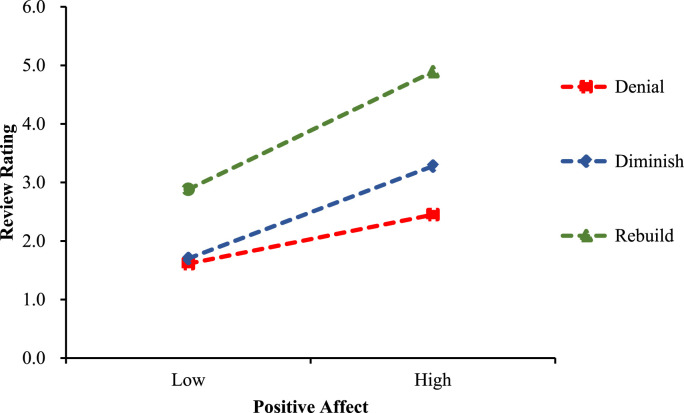

The moderating effects of crisis response strategy on the relationships between positive affect, negative affect, cognitive effort, and customer satisfaction were sequentially investigated. As shown in Table 9 , when denial is the reference group, both interactions between positive affect and D 1 (β = 0.1117, p < .001) and D 2 (β = 0.1767, p < .001) are significant. The supplementary analysis shows that when rebuild is the reference group, the interaction between positive affect and D 1 (β = −0.065, p < .05) is also significant (see Table 10). Specifically, the effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction differs among the three types of crisis response strategies. As presented in Fig. 1 , the positive effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction strengthens from the denial group (β = 0.1262, p < .001) to the diminish group (β = 0.2378, p < .001) to the rebuild group (β = 0.3028, p < .001). Therefore, the effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction is significantly higher in the rebuild group than in the diminish and denial groups. This indicates that hotels using rebuild strategies can have higher customer satisfaction than those that implemented diminish or denial strategies. In addition, the R2 change of the interaction effect is significant (R2 change = 0.0046, p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 2a is supported by the findings.

Table 9.

Moderating effect on the relationship between positive affect and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Positive Affect (PA) | 0.1262*** | 0.0153 | 8.2569 | 0.0962 | 0.1561 |

| D1 | 0.1856** | 0.0678 | 2.7391 | 0.0527 | 0.3185 |

| D2 | 1.4223*** | 0.0512 | 27.7816 | 1.3219 | 1.5226 |

| Interaction Items | |||||

| PE × D1 | 0.1117*** | 0.0327 | 3.4193 | 0.0476 | 0.1757 |

| PE × D2 | 0.1767*** | 0.0174 | 10.1372 | 0.1425 | 0.2108 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Negative Affect | −0.0925*** | 0.0103 | −8.9937 | −0.1127 | −0.0723 |

| Cognitive Effort | −0.0084* | 0.0034 | −2.4614 | −0.0151 | −0.0017 |

| Review Length | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | −.2679 | −0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −1.3771 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 1.6093 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1246*** | 0.0223 | 5.5898 | 0.0809 | 0.1683 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0001** | 0.0000 | 2.6779 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | −7.8099 | .0574 | −135.9853 | −7.9225 | −7.6972 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Denial as the reference group.

PE × D1 and PE × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of positive affect on customer satisfaction in the denial and diminish conditions and the denial and rebuild conditions, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The interaction between positive affect and crisis response strategy on customer satisfaction.

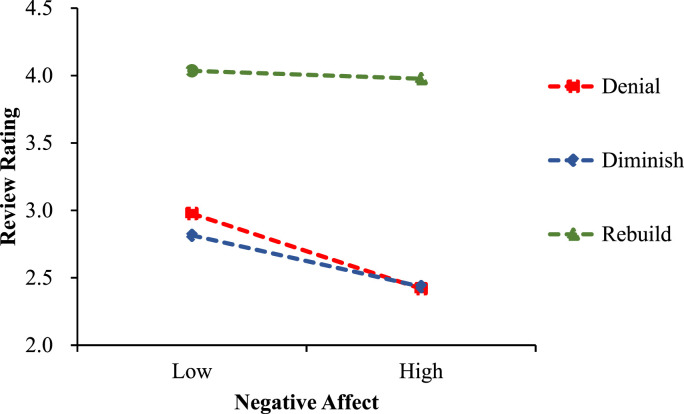

With respect to negative affect, when denial is the reference group, the interaction between negative affect and D 2 (β = 0.1776, p < .001) is significant, but the interaction between negative affect and D 1 (β = 0.0629, p > .05) is not significant (see Table 11 ). It can be concluded that the relationship between negative affect and customer satisfaction differs between the denial and rebuild groups. In addition, when rebuild is the reference group, the supplementary analysis shows that the interaction between negative affect and D 1 (β = −0.1147, p < .01) is significant, revealing that the difference between slopes relating negative affect and customer satisfaction in the rebuild and diminish conditions is significant (see Table 12). As shown in Fig. 2 , the negative effect of negative affect on customer satisfaction strengthened from the rebuild group (β = −0.0209, p > .05) to the diminish group (β = −0.1355, p < .001) to the denial group (β = −0.1985, p < .001), indicating that the effect of negative affect on customer satisfaction was significantly higher in the denial group than in the rebuild and diminish groups. As expected, implementing less accommodative strategies such as denial may reinforce the negative association between hotel customers’ negative affect and their satisfaction. Furthermore, a significant change in R2 of the interaction effect was identified (R2 change = 0.0030, p < .001). Thus, these results support Hypothesis 2 b.

Table 11.

Moderating effect on the relationship between negative affect and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Negative Affect (NA) | −0.1985*** | 0.0175 | −11.3287 | −0.2328 | −0.1641 |

| D1 | 0.2048 | 0.1536 | 1.3330 | −0.0965 | 0.5060 |

| D2 | 2.0924*** | 0.0992 | 21.0921 | 1.8978 | 2.2869 |

| Interaction Items | |||||

| NA × D1 | 0.0629 | 0.0383 | 1.6415 | −0.0122 | 0.1381 |

| NA × D2 | 0.1776*** | 0.0222 | 8.0162 | 0.1341 | 0.2210 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Positive Affect | 0.2615*** | 0.0070 | 37.2184 | 0.2478 | 0.2753 |

| Cognitive Effort | −0.0138*** | 0.0034 | −4.0362 | −0.0205 | −0.0071 |

| Review Length | −0.0003** | 0.0001 | −2.8737 | −0.0005 | −0.0001 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.7555 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9917 | −0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1303*** | 0.0225 | 5.8053 | 0.0863 | 0.1744 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000* | 0.0000 | 2.3992 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | −0.1248 | 0.1076 | −1.1594 | −0.3358 | 0.0863 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Denial as the reference group.

NA × D1 and NA × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of negative affect on customer satisfaction in the denial and diminish conditions and denial and rebuild conditions, respectively.

Fig. 2.

The interaction between negative affect and crisis response strategy on customer satisfaction.

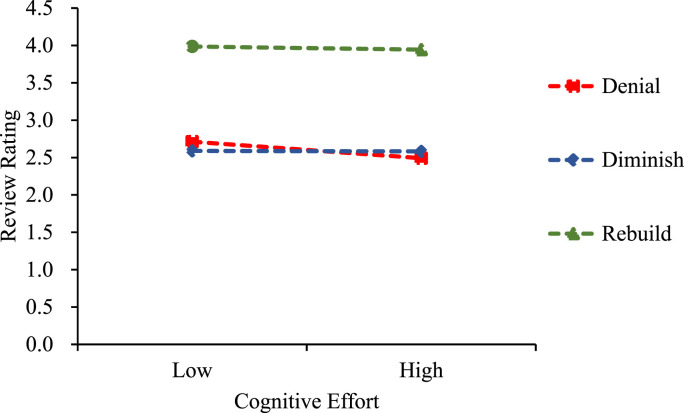

Table 13 shows that when denial is the reference group, interactions between cognitive effort and D1 (β = 0.0301, p < .05) and D2 (β = 0.0251, p < .01) are significant. Specifically, the relationship between cognitive effort and customer satisfaction differs between the denial and diminish conditions, as well as in the denial and rebuild conditions. In contrast, when rebuild is the reference group, the interaction between cognitive effort and D 1 (β = 0.0005, p > .05) is not significant (see Table 14). Thus, the slopes of cognitive effort and customer satisfaction in the rebuild and diminish conditions are not significantly different from each other. Fig. 3 shows that the negative effect of cognitive effort on customer satisfaction is stronger in the denial group (β = −0.0310, p < .001) than in the diminish (β = −0.0008, p > .05) and rebuild groups (β = −0.0058, p > .05). The R2 change of this interaction effect is significant (R2 change = 0.0003, p < .01). These findings suggest that the negative effect of cognitive effort on customer satisfaction can be stronger if a hotel employs a denial strategy than if it employs a diminish or rebuild strategy. As a result, Hypothesis 2c is supported.

Table 13.

Moderating effect on the relationship between cognitive effort and review rating.

| Dependent Variable: Review Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | Bias-corrected 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Cognitive Effort (CE) | −0.0310*** | 0.0067 | −4.6322 | −0.0441 | −0.0179 |

| D1 | −0.2476 | 0.1534 | −1.6143 | −0.5484 | 0.0532 |

| D2 | 1.1696*** | 0.0893 | 13.0972 | 0.9945 | 1.3447 |

| Interaction Items | |||||

| CE × D1 | 0.0301* | 0.0153 | 1.9618 | 0.0000 | 0.0602 |

| CE × D2 | 0.0251** | 0.0079 | 3.1635 | 0.0095 | 0.0407 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Positive Affect | 0.2638*** | 0.0072 | 36.8854 | 0.2498 | 0.2778 |

| Negative Affect | −0.0937*** | 0.0105 | −8.9168 | −0.1143 | −0.0731 |

| Review Length | −0.0002 | 0.0001 | −1.7300 | −0.0003 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Contribution | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.7980 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| Reviewer's Helpful Votes | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 1.0120 | −0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Hotel's Average Rating | 0.1406*** | 0.0227 | 6.1899 | 0.0961 | 0.1851 |

| Hotel's Review Number | 0.0000* | 0.0000 | 2.3378 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Constant | 0.8337*** | 0.1152 | 7.2359 | 0.6078 | 1.0597 |

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Denial as the reference group.

CE × D1 and CE × D2 examined the difference between the conditional effects of cognitive effort on customer satisfaction in the denial and diminish conditions and denial and rebuild conditions, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The interaction between cognitive effort and crisis response strategy on customer satisfaction.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Discussion

This study explores the impacts of hotel customers' affective service evaluation and cognitive effort on their satisfaction in health-related crises and examines how a hotel's strategy moderates such relationships. This study contributes to the crisis management literature in tourism by offering a better understanding of the adoption of response strategies to improve hotel customer satisfaction in a health-related crisis. The results of the qualitative analysis revealed that the three crisis response strategies adopted by most hotels were denial, diminish, and rebuild. According to situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), the three strategies correspond to the three levels (i.e., low, moderate, and high) of crisis responsibility that may be attributed to the hotel (Coombs, 2018; Coombs & Holladay, 2007).

The results from this study indicate that hotel customers' positive affect substantially impacts their online ratings, whereas negative affect and cognitive effort are negatively related to customer satisfaction. These findings highlight the importance of customers' affective evaluations and cognitive effort in driving customer satisfaction (Del Bosque & Martín, 2008; Lee et al., 2019). Both positive affect and negative affect are critical precedents of the customer satisfaction formation process, since customers' emotional responses are elicited by their service experience (Ali et al., 2016; Del Bosque & Martín, 2008). In addition, the absolute value of the direct effect coefficient of positive affect on customer satisfaction is larger than that of negative affect, indicating that positive affect has a more significant impact on customer satisfaction than does negative affect. This finding is different from previous research illustrating that customer satisfaction is more sensitive to negative affect than positive affect (Zhu et al., 2020). A possible explanation is that in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak, customers’ expectation of their hotel experience is lower and therefore easier to satisfy (Mehta et al., 2021). Nevertheless, customers are willing to give a higher rating score if their expectations and emotional needs are met and more positive affect is produced.

Regarding the moderating effect of hotels' crisis response strategies, the results of this study indicate that hotel responses play an important role in the formation process of customers' experience and satisfaction. The effects of positive affect, negative affect, and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction are strengthened by the hotel's crisis response strategy. More specifically, the crisis response strategy positively moderates the positive relationship between positive affect and customer satisfaction, while the crisis response strategy negatively moderates the negative relationship between negative affect and customer satisfaction, as well as that between cognitive effort and customer satisfaction. The more accommodative the strategies a hotel implements in response to COVID-19 are, the stronger the positive affect on customer satisfaction among strategies from denial to diminish to rebuild. These results are consistent with the extant literature, which suggests that highly accommodative strategies such as rebuild and apology are more effective in mitigating customers' negative reactions and protecting organizational reputation than less accommodative strategies such as denial and excuses (Grappi & Romani, 2015).

Previous studies have indicated that organizational reputation benefits most when diminish strategies are paired with accidental crises, while rebuild strategies are best paired with preventable crises (Coombs, 2018; Coombs & Holladay, 1996). However, the outbreak of COVID-19 has been driven by external forces beyond hotels' control, so in many aspects, they are also victims of the crisis and certainly not responsible for it (Coombs, 2007; Kwok et al., 2021). According to SCCT, if an organization determines that it is a victim of the crisis and possesses a low level of responsibility, it may implement less accommodative strategies, including denial and scapegoating (Coombs, 2007). Interestingly, the results of the current study reveal that denial and even diminish strategies are inclined to aggravate the negative effects of customers' negative reactions, resulting in lower satisfaction. In contrast, hotels that implement rebuild strategies can benefit from less negative emotions and higher online ratings, which is of great benefit to the hotel's reputation recovery and electronic word-of-mouth (eWoM).

5.2. Theoretical implications

Our study has made three significant theoretical contributions to extant tourism literature. First, our study contributes to the existing crisis management in tourism literature by identifying hotels' crisis response strategies from the customer's perspective and highlighting the individual's service experience during COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic is a once-in-a-century global crisis, which provides an important and valuable research context for crisis management. Given that extant crisis management studies have predominantly explored crisis response strategies from the organizational perspective, this study innovates in detecting hotels' response strategies by looking into customers' online reviews, which otherwise would be difficult to reveal through traditional methodological approaches (Qi & Li, 2021). As shown in our study, the use of online reviews from customers' perspective is methodological innovative as at the initial stage of the pandemic with unforeseeable uncertainty, hotels rarely disclosed their crisis response publicly. Online reviews with its wide accessibility present a valuable opportunity to collectively approach issues (i.e., crisis response strategies in this study) that are traditionally examined through the organizational perspective in a faster, more effective, and less intrusive manner. In addition, COVID-19 is not only a crisis that requires immediate reaction but is also likely to change consumer behaviour in the long term (Hu et al., 2021). Therefore, the contribution of this research lies in providing a deep understanding of the effects of affective evaluation and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction in the context of this health-related crisis, providing a point of reference for tourism researchers when examining behaviour during similar health-crisis.

Second, despite the critical role of crisis response strategies in crisis management (Coombs & Holladay, 2009; Liu et al., 2015), the moderating effect of the crisis response strategy has not been clearly understood when examining its impacts on customer satisfaction. Our study addressed this gap by empirically examining the impacts of different crisis response strategies on the relationships between cognitive effort/affective evaluation and customer satisfaction. The rebuild strategy has a greater positive influence on the relationship between positive affect and customer satisfaction. In comparison, the denial strategy has a greater negative impact on the effects of cognitive evaluation and negative affect on customer satisfaction. Moreover, unlike prior studies that treat crisis response strategies as certain antecedent of satisfaction or examine the moderating effect of crisis response strategies by choosing certain strategies (Crijns et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018), our study examines crisis response strategies in its entirety as a moderating variable and provide insights into its underlying mechanism. As such, our study's empirical insights advance our knowledge of the moderating effect of crisis responses as a moderating variable but also the links between affective evaluation/cognitive effort and online ratings.

Third, this study not only extends the application of SCCT to tourism and hospitality research in the context of COVID-19 but also adds knowledge to SCCT by challenging its proposition that the organization should match its crisis response strategies to the crisis type (Coombs, 2007). The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically affected the hotel occupancy rate, making hotels additional victims of this health-related crisis (Coombs, 2007; Hidalgo et al., 2022). Nevertheless, our findings suggest that if hotels adopt relatively less accommodative strategies such as denial, as suggested by SCCT, the effect of customers' negative affect on their satisfaction will be stronger. During COVID-19, although customers' expectations of some core hotel attributes (e.g., room, bed, and price) decreased and they were more tolerant and forgiving, they had higher standards for health and safety attributes, such as social distancing and hygiene (Hu et al., 2021). Therefore, this study challenges SCCT by demonstrating that even though hotels are victims of the COVID-19 pandemic, more accommodative strategies such as rebuild are more effective than denial strategies in protecting hotels' reputations and eWoM. Our study highlights that when matching the response strategy to the crisis, organizations should not only consider the level of responsibility for the crisis but also attach importance to customers’ expectations.

5.3. Practical implications

This study provides several important practical insights for hotel practitioners regarding hotels' responses to COVID-19. First, it yields valuable insights for hotel managers on how to take appropriate strategies when health-related crises occur. Crisis response strategies often have a double-edged sword effect on customer satisfaction. Both the denial and diminish strategies negatively affect customer satisfaction, while a rebuild strategy has a significant positive influence on customer satisfaction. If hotel managers determine that a low level of responsibility is attributed to the hotel and refuse to refund or take pandemic prevention measures to save money, it may lead to a drop in online ratings. Although the outbreak of COVID-19 is an external crisis beyond hotels’ control and intent, it may turn into an internal crisis if the hotel overlooks the crisis and refuses to implement more accommodative strategies.

Second, hotel practitioners should note that health-related crises have brought numerous opportunities for the hotel industry. The findings suggest that highly accommodative strategies, including refundable booking fees and flexible cancellation, will strengthen the effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction. However, these highly accommodative strategies depend on the balance between customer satisfaction and hotels' financial constraints. Thus, strategies of future hotel credits or flexible rescheduling present more promising strategies. As shown in the qualitative analysis, proactive responses should be encouraged, which can lead to an increase in customer satisfaction despite all the inconveniences caused by the pandemic. These responses include extra safety measures (e.g., extra cleaning in hotels’ public areas), provision of extra services and amenities for compensation (e.g., small gifts for guests when the gym or restaurant in the hotel is closed) and maintenance of the same service quality to reduce the negative impacts caused by the pandemic.

6. Limitations and future research

This study is not without limitations. First, the way in which guests rate hotels is influenced by their cultural background and social norms. COVID-19 more likely accentuated these differences. A comparative study on hotel guest experience across different types of hotels and different countries during the pandemic is encouraged to advance the topic of this study. In addition, this study treats all hotels as a whole to collectively reflect the crisis response strategies adopted in the hotel industry. Based on the online data in this study, it is practically impossible to categorize online reviews based on the types of hotels and guests. As pointed out by one of the reviewers, different types of hotels could result in different strategies. Future research is encouraged to consider the difference in strategies adopted by different types of hotels. While the LIWC software automatically provides values of positive affect, negative affect, and cognitive effort, the accuracy of the values needs to be carefully examined. Future research that employs a more precise embedded dictionary to generate the values of these variables is promising. The data in this study were collected until the end of April 2020, when the outbreak of COVID-19 was at an early stage—a time of chaos for hotels, with constant changes in travel restrictions, presenting a critical stage in understanding crisis management with uncertainty (Jin et al., 2019; Le & Phi, 2021). With the high uptake of vaccinations worldwide and the return of certainty to travel, future research that compares the different response strategies among various periods of the outbreak can provide additional insights. Last, the crisis response strategies evaluated in this study were taken from the perspective of customers, which may be different from the hotels’ actual strategies. Future research using a survey to investigate the strategies adopted by hotels would be useful.

Author contributions

Meng Yu: Conceived and designed the analysis, Contributed data or analysis tools, Wrote the paper, Other contribution, Supervision on this research, Mingming Cheng: Conceived and designed the analysis, Performed the analysis, Wrote the paper, Other contribution, Supervision on this research, Lin Yang: Contributed data or analysis tools, Wrote the paper, Zhicheng Yu: Conceived and designed the analysis, Collected the data, Contributed data or analysis tools, Performed the analysis, Wrote the paper.

Impact statement

This research shows that hoteliers' denial strategies in response to the impact of COVID-19 on hotels can negatively influence customers satisfaction, despite hotels are also victims of such crisis. In the health-related crisis, the level of responsibilities customers attribute to hotels are different from the level hotels attribute to themselves. Our findings suggest that high accommodation strategies will strengthen the effect of positive affect on customer satisfaction. However, these high accommodation strategies should depend on the balance between customers' satisfaction and hotels’ financial constraints.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Biographies

Meng Yu (Ph.D.), is a lecturer in tourism at Sichuan University, China. Her main research interests are the sharing economy and the application of social network in tourism research.

Dr Mingming Cheng is an Associate Professor in Digital Marketing and Research Lead of the Social Media Research Lab in the School of Management and Marketing at Curtin University, Australia. Mingming's research examines the digital transformation of the tourism industry - new experiences (e.g., Airbnb), new marketing channels (e.g., social media), new technology-savvy markets (e.g., Chinese post-80s tourist market) and more recently, environmental impacts of tourism including carbon footprint. Further information can be found: mingmingcheng.com.

Lin Yang is a master student at the School of Tourism, Sichuan University. Her research interest is event management.

Zhicheng Yu is a master student at the School of Tourism, Sichuan University. His research interests focus on the hospitality industry and peer-to-peer accommodation.

Footnotes

The work presented in this paper was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (72102156) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M673273) provided to Meng Yu.

Appendix 1. Coding scheme

| Themes (Posture) | Definition | Code | Data example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denial posture | |||

| Attack the accuser | The hotel is impolite to the person or group that claims the crisis exists. | impolite and rude attitudes; unethical behaviours; shout at customers; threaten customers; quarrel with customers; hang up on customers; discrimination | Due to COVID-19 I had to cancel … I told him I would have to dispute it on my credit card. At this point he became belligerent. He was yelling at me that he wouldn't do anything. |

| Denial | The hotel denies guests' demands related to the pandemic. | refuse to refund; lack of empathy; refuse to provide help; refuse to answer questions; refuse to clean room; refuse to provide information | La Comtesse cancelled my reservation (understandably) after they closed due to COVID-19. They refused to refund my money. |

| Scapegoat | The hotel states that some person or group outside the hotel is responsible for the crisis. | pass the buck; selfish; evasive; shift the responsibility | The day when the Spanish state announced the state of emergency because of the COVID-19 … All Saturday I was fed with evasive responses promising “to make a decision when the policies of Booking.com are known to us and the manager is talked to …” |

| Ignoring | The hotel neglects to implement pandemic prevention measures and disregards guests' demands by refusing to answer phone calls and emails. | ignore; undervalue; disregard; not sterilized and cleaned | With COVID-19 and the stay-at-home orders, I called to cancel and request a refund … I have called 4 times now and the call center keeps telling me they will submit a request to billing for a call back to explain, however I have received nothing. I was not given a full or partial refund as a high-risk patient who had to cancel their booking due to COVID-19 … In addition to ignoring all my emails, they stated the manager was never available anytime I tried to call up regarding this. |

| Diminish posture | |||

| Excuse | The hotel offers an excuse by providing an explanation for its inability to provide normal service and amenities, as well as free cancellation. | excuse; explain; response | During these 5 nights, I asked for cleaning my room but front desk staff said I cannot go in my room for cleaning due to the coronavirus period … I asked for cleaning my room but front desk staff said I cannot go in my room for cleaning due to the coronavirus period. I am not a quarantine guest!! But they just did this is to avoid cross-infection, what an excuse!!! Unfortunately, we planned a trip to Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic … we asked for our money back … Their response was “the virus was outside of our control and as such I am unable to refund your deposit”. I stayed here for a few days during the COVID-19 pandemic … Food was average, but it was explained that they did not have fresh products because of the lockdown and had many people to feed in these difficult circumstances. |

| Justification | The hotel justifies that the pandemic is not as bad as it may seem, and its actions to mitigate it are reasonable. | guarantee safety to customers; pandemic is not serious | On the grounds that Milan was quarantined because of the new and dangerous coronavirus … On the contrary, with all his boldness, he tries to convince me that everything is okay and there is no reason to worry. |

| Separation | Individuals or departments disconnect themselves from the responsible parties within the hotel. | separation | Horrible amid COVID-19 restrictions … I called everyday the week before our trip and then after the “start” of our trip to try and get a refund. The Manager was never around when we called (which was during their business hours!) and the Manager was the only person able to issue a refund. |

| Rebuild posture | |||

| Compensation | The hotel compensates guests by providing them with additional services or gifts. | upgrade room; compensate; give gifts; prepare a surprise; provide additional service | Coronavirus had set back staffing so they were shorthanded … The desk clerk provided a free bottle of wine for our “troubles” & for us being so understanding. |

| Apology | The hotel expresses regret for inconvenience caused by the pandemic. | apology; sorry; regret | They notified her the mountain got shut down due to COVID-19 30 min after we checked in … Without hesitation Dena talked to me and reassured me about the situation and apologized for everything. |

| Bolstering | The hotel adapts to the pandemic by catering to the guests, including providing free cancellation, quality service, and taking pandemic prevention measures. | free cancellation and reschedule; quality service; ensure safety and hygiene; COVID-19 preventable measure | As COVID-19 is ravaging throughout the world there are few places where we would feel safer than at Hyatt Regency Hua Hin … Home Away from Home and perhaps safer than home, the hotel seems to be taking all possible precautions to keep its guests secure. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the cruise has been cancelled … Despite my having booked a nonrefundable room rate, the hotel did indeed refund my entire fee, without penalty! |

References

- AHLA . 2020. COVID-19's impact on the hotel industry.https://www.ahla.com/covid-19s-impact-hotel-industry [Google Scholar]

- Ali F., Amin M., Cobanoglu C. An integrated model of service experience, emotions, satisfaction, and price acceptance: An empirical analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. 2016;25(4):449–475. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2015.1019172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Backer E., Ritchie B.W. VFR travel: A viable market for tourism crisis and disaster recovery? International Journal of Tourism Research. 2017;19(4):400–411. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]