Abstract

The GGGGCC (G4C2) repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the most common genetic cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Dysregulated DNA damage response and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been postulated as major drivers of toxicity in C9ORF72 pathogenesis. Telomeres are tandem-repeated nucleotide sequences that are located at the end of chromosomes and protect them from degradation. Interestingly, it has been established that telomeres are sensitive to ROS. Here, we analyzed telomere length in neurons and neural progenitor cells from several induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines from control subjects and C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. We found an age-dependent decrease in telomere length in two-month-old iPSC-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 carriers as compared to control subjects and a dysregulation in the protein levels of shelterin complex members TRF2 and POT1.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells; motor neuron differentiation; telomeres; C9orf72; Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Frontotemporal dementia

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are two neurodegenerative diseases that share common genetic and pathogenic features. The GGGGCC (G4C2) repeat expansion in the chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) is the most common familial form of ALS and FTD (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). As we began to explore the mechanisms that drive disease pathogenesis in C9ORF72 repeat expansion, we found that DNA damage and the DNA damage response (DDR) have a central role in disease pathogenesis. Increases in DNA damage and dysregulation of DNA repair pathways have been reported in several in vitro and in vivo models of C9ORF72-related ALS/FTD (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2016; Farg et al., 2017; Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2019; Maor-Nof et al., 2021; Szebényi et al., 2021). Strikingly, we and others have found that reducing levels of P53, a key regulator of genome instability, can rescue neuronal death in C9ORF72 neurons (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2019; Maor-Nof et al., 2021). Interestingly, reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to DNA damage in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons from C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2016), and there is evidence that ROS can trigger telomere attrition (Guan et al., 2015).

Telomeres are DNA-protein complexes located at the end of mammalian chromosomes. Their main function is to protect DNA from degradation. Telomere structure consists of TTAGGG repeated nucleotide sequences associated with 6 proteins that form the shelterin complex: TRF1, TRF2, POT1, RAP1, TPP1 and TIN2 (Penev et al., 2022). The shelterin complex provides protection to chromosome ends by binding to double- and single-stranded DNA to prevent the activation of the DDR. TRF1 and TFR2 bind to double-strand telomere DNA, and POT1 binds to single-strand telomere DNA (Markiewicz-Potoczny et al., 2021). Dysregulation of shelterin complex proteins can leave unprotected chromosome ends prone to telomere attrition (Miller et al., 2012).

Telomere attrition has been analyzed in other neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). For instance, a study that compared 260 PD patients to 270 age-matched controls found shorter leucocyte telomere length in PD patients (Wu et al., 2020). Shortened telomere length has also been reported in AD patients as compared with age-matched controls (Scarabino et al., 2017). Dhillon et al. showed that ApoE4 homozygous AD patients have shorter telomeres compared to controls (Dhillon et al., 2020). Telomere analysis of patients with Huntington’s disease and FTD showed telomere attrition (Kota et al., 2015). Nonetheless, most of these analyses have been conducted in blood cells and brain sections with a mixture of different neuronal populations. To date, there are no studies that analyze telomere length in neuronal populations.

Here we analyzed telomere length and the expression levels of shelterin complex members TRF1, TRF2 and POT1, in iPSC-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers and healthy controls. This analysis was performed at different stages of motor neuron (MN) differentiation from iPSCs, including neuroepithelial cells (NEP), motor neuron progenitors (MNPs), and post-mitotic MNs. We chose this model because MNs are a disease-relevant neuronal population and their differentiation protocol is well-characterized and produces highly pure MN populations. We found differential regulation in the levels of shelterin complex members and a decrease in telomere length in differentiated 2-month-old MNs, indicating that C9ORF72 repeat expansion-induced telomere attrition can further contribute to genome instability.

Materials and Methods

Motor Neuron Differentiation From iPSC Lines

In this study we used 3 control iPSC lines: 37L20, 35L5 and 35L11, with ages at biopsy between 45 and 56 years-old (two males and one female), and 3 lines from C9ORF72 carriers: 40L3, 16L14 and 42L11, with ages at biopsy between 39 and 59 years-old (two males and one female), All lines have been fully characterized and published previously (Zhang et al., 2013; Freibaum et al., 2015; Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2016). Motor neurons were differentiated as described previously (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2019). Briefly, iPSCs were plated and expanded in mTSER1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies) in Matrigel-coated wells. Twenty-four hours after plating, the culture medium was replaced with neuroepithelial progenitor (NEP) medium, DMEM/F12, neurobasal medium at 1:1, 0.5X N2, 0.5X B27, 0.1 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma), 1X Glutamax (Invitrogen), 3 μM CHIR99021 (StemCell technologies), 2 μM DMH1 (Tocris Bioscience), and 2 μM SB431542 (StemCell technologies). After 6 days, NEPs were dissociated with accutase, split 1:6 into Matrigel-coated wells, and cultured for 6 days in motor neuron progenitor induction medium (NEP with 0.1 μM retinoic acid and 0.5 μM purmorphamine, both from Stem Cell technologies). Motor neuron progenitors were dissociated with accutase to generate suspension cultures. After 6 days, the cultures were dissociated into single cells, plated on laminin-coated plates/coverslips in motor neuron differentiation medium containing 0.5 μM retinoic acid, 0.1 μM purmorphamine, and 0.1 μM Compound E (Calbiochem). Post-mitotic motor neurons were cultured up to two months and analyzed at 1 month, 1.5 months, and 2 months.

Western Blot Analysis

Human iPSCs, NEP, MNP, and MN cultures were lysed with Pierce™ RIPA Buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Protein lysates (25 µg) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted to detect the expression of specific proteins using the primary antibodies listed in Table 1 and incubated overnight at room temperature. Membranes were then washed with TBS-T and incubated with appropriate anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IR-Dye secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences). Membranes were imaged with an Odyssey® DLx Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and images were analyzed by Image Studio (LI-COR Biosciences). Equal loading was evaluated by assessing beta-actin levels.

TABLE 1.

List of antibodies used for western blot in this study.

| Antibody | Source sp. | Vendor | Catalogue No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRF2 | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotech | sc-52968 |

| POT1 | Rabbit | Proteintech | 10581-1-AP |

| β-Actin | Rabbit | Abclonal | AC038 |

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from iPSC cells and iPSC-derived motor neurons were isolated using PureLink™ RNA Mini Kits (Invitrogen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were measured with a NanoDrop™ One Microvolume UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and reverse transcribed to synthesize cDNA by SuperScript™ IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions using C1000 Thermal Cycler (Biorad). cDNA (10 ng) was used for quantitative real-time PCR by SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystem) in a QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System using the primers listed in Table 2. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene and Ct values for each gene were normalized to that of GAPDH. Relative expression was analyzed by the 2 delta-delta Ct method.

TABLE 2.

List of primers used in this study.

| qPCR primers | Primer Sequences (5’ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| POT1 forward | TCAGATGTTATCTGTCAATCAGAACCT |

| POT1 reverse | TGTTGACATCTTTCTACCTCGTATAATGA |

| TRF1 forward | GCTGTTTGTATGGAAAATGGC |

| TRF1 reverse | CCGCTGCCTTCATTAGAAAG |

| TRF2 forward | GACCTTCCAGCAGAAGATGCT |

| TRF2 reverse | GTTGGAGGATTCCGTAGCTG |

| GAPDH forward | TGCACCACCACCTGCTTAGC |

| GAPDH reverse | GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG |

| TEL forward | CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT |

| TEL reverse | GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT |

| 36B4 forward | CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC |

| 36B4 reverse | CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA |

| hTERT forward | GCCGATTGTGAACATGGACTACG |

| hTERT reverse | GCTCGTAGTTGAGCACGCTGAA |

Telomere Length Quantification

We performed telomere length quantification by qPCR as previously described by (Chuenwisad et al., 2021). Briefly, we performed genomic DNA extraction from iPSC, NEP, MNP, and MN using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific). We used 15 ng of genomic DNA with the primers listed in Table 2. We considered the ratio of copy number of telomeric repeat to the number of a single-copy gene, in this case the 36B4 gene, which encodes a ribosomal protein. The telomere-to-single copy gene (T/S) ratio give us an estimate of telomere length.

Assessment of Telomerase Activity

Telomerase activity was measured by using the telomerase activity quantification qPCR assay kit (ScienCell, CA) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, equal number of cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer, provided by manufacturer, supplemented with HaltTM Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and β-mercaptoethanol. This step released the native telomerase enzyme from cells in an ex-vivo condition. 0.5 μL cell lysates were then incubated with appropriate amount of 5X telomerase reaction buffer, from the kit, and nuclease free water. This reaction was performed in C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Biorad) at 37°C for 3 h followed by an inactivation step at 85°C for 10 min. Finally, to measure the telomere production by ex-vivo telomerase qPCR was performed in QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem), according to manufacturer’s instruction, using supplied 2X GoldNStart TaqGreen qPCR master mix and telomere primer set. Relative telomerase activity was calculated by 2−ΔCt method as per manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunostaining

Human iPSCs, NEP, and MNP cultures from controls and C9ORF72 carriers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The cells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 min and incubated using the primary antibodies anti Oct4 1:500 (abclonal; cat#A7920), Sox1 1:200 (R&D systems; cat#AF3369), Olig2 1:500 (R&D systems; cat#AF2418), ChAT 1:200 (Millipore; cat#AB144P) and TUJ1 1:1000 (abclonal; cat# A17913), overnight at 4°C. Cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488, 568, and 647 at a 1:500 dilution for 2 h at room temperature, and washed with PBS and incubated with Hoechst for 5 min.

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal images from iPSC, NEP, MNP, and MN were acquire with a Leica DM6 upright laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Images were processed with Leica LAS AF software.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism version 9.1 (La Jolla, CA). Two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction were applied to analyze differences between two means. Significant differences among multiple means were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Null hypotheses were rejected at p > 0.05.

Results

Analysis of Telomere Length and the Expression of Telomere Maintenance Proteins During Motor Neuronal Differentiation

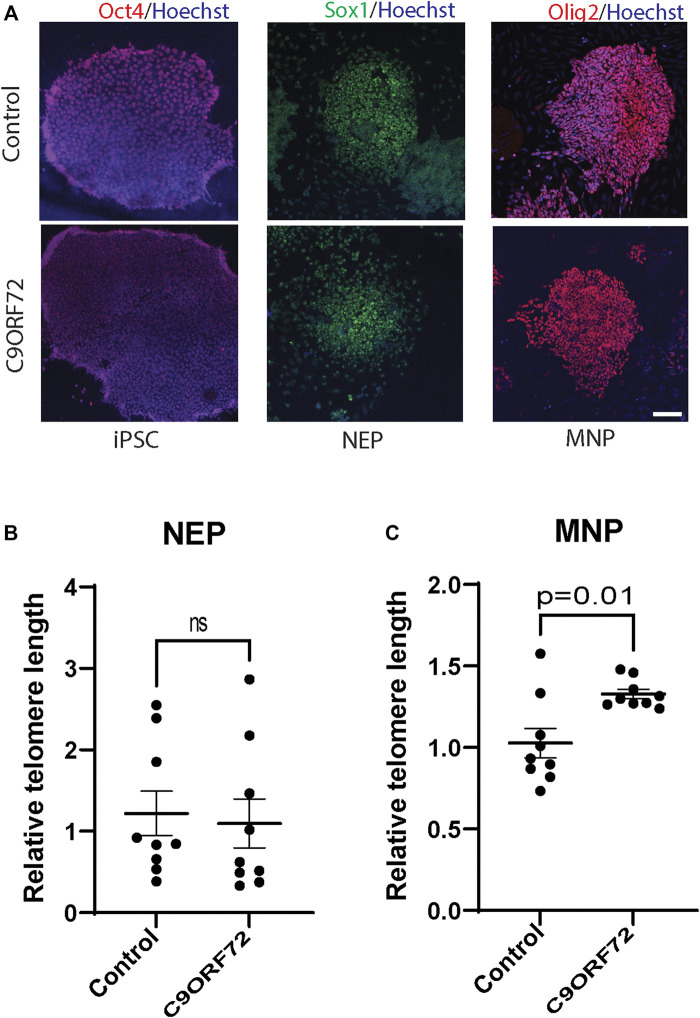

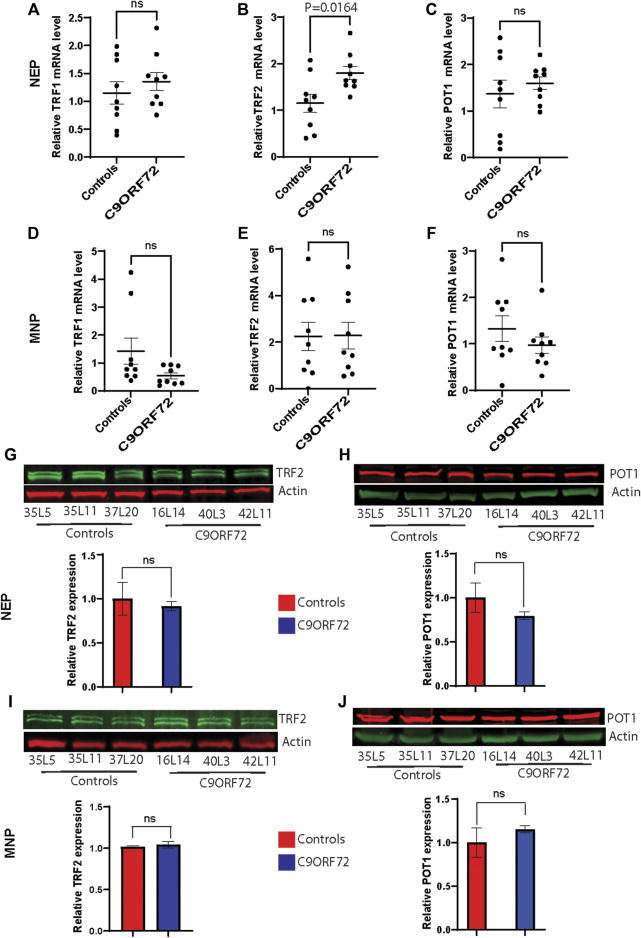

To determine whether there were differences in telomere length during differentiation of iPSCs into MNs (Figure 1A), we used iPSC lines from 3 control subjects and 3 C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. These lines were fully-characterized and published previously (Zhang et al., 2013; Freibaum et al., 2015; Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2016). When we analyzed telomere length in NEP, we found no significant differences between controls and C9ORF72 carriers (Figure 1B), on the other hand we found a significant increase in telomere length in MNP from C9ORF72 as compared with controls (Figure 1C p = 0.01). Then, we analyzed the relative mRNA expression of the telomere maintenance genes TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 at different stages of the MN differentiation protocol. When we analyzed NEP, we found no significant differences in TRF1 or POT1 mRNA levels. However, TRF2 mRNA levels were significantly higher in NEP from C9ORF72 carriers (Figures 2A–C; p = 0.0164). For MNP, there were no significant differences between controls and C9ORF72 carriers (Figures 2D–F). In addition we quantified TRF2 and POT1 protein levels by western blot and we did not find a significant difference between controls and C9ORF72 carriers in the NEP stage (Figures 2G,H) or the MNP stage (Figures 2I,J). These data suggest that C9ORF72 repeat expansion induces differential TRF2 mRNA expression, in NEP but not at the protein level, and a slight but significant difference in telomere length in MNP.

FIGURE 1.

Telomere length analysis during the differentiation of iPSCs to MNs from controls and C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. Representative images of control and C9ORF72 (A) iPSCs, NEP, and MNP. Telomere length quantification in (B) NEP and (C) MNP, from 3 controls and 3 C9ORF72 iPSC lines, from 3 independent differentiations. Two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was applied. ns, not significant. Scale bar = 20 µm.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of the expression of telomere maintenance genes during the differentiation of iPSCs to MNs from controls and C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. qPCR analysis to compare expression levels (A) TRF1, (B) TRF2 and (C) POT1 transcripts in NEP and levels of (D) TRF1, (E) TRF2 and (F) POT1 in MNP from 3 control subjects and 3 C9ORF72 carriers, from 3 independent differentiations. Western blot analyses to compare protein levels of (G) TRF2 and (H) POT1 in NEP and protein levels of (I) TRF2 and (J) POT1 in MNP, from 3 controls and 3 C9ORF72 iPSC lines, Two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was applied. ns, not significant.

Age-dependent Telomere Attrition and Shelterin Complex Dysregulation in C9ORF72-Derived MN

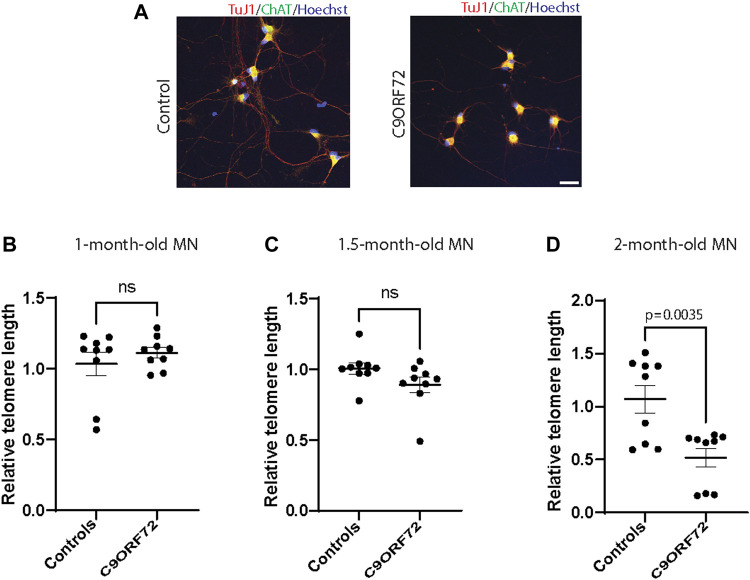

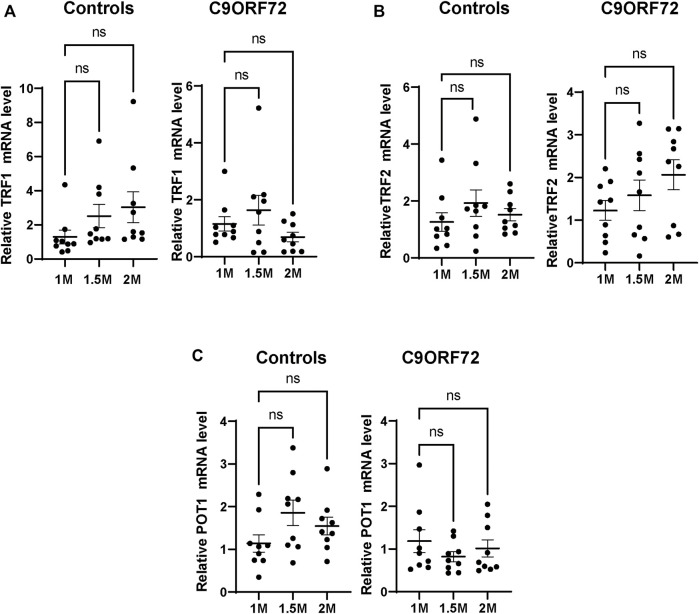

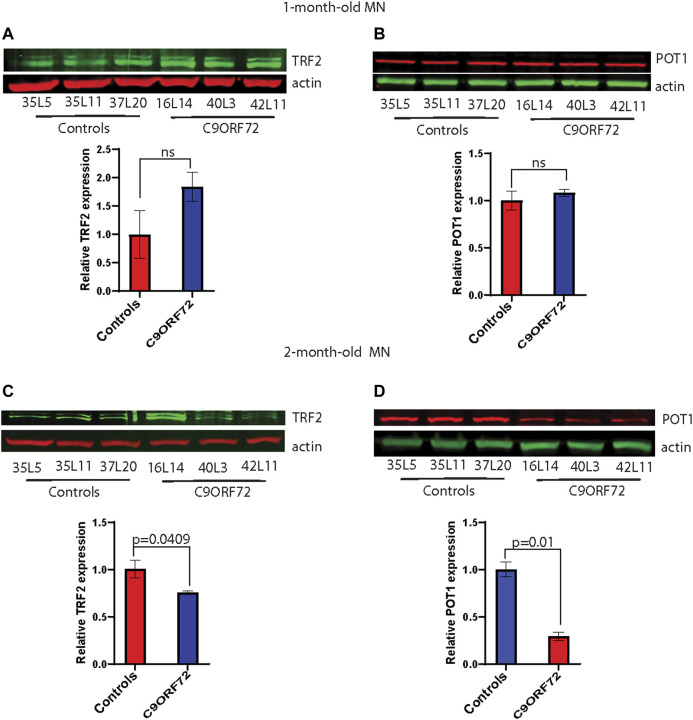

Next, we analyzed telomere length in post-mitotic MNs differentiated from iPSCs (Figure 3A). There were no significant differences in telomere length between controls and C9ORF72 in 1-month and 1.5 month-old MNs (Figures 3B,C). However, in 2-month-old MNs, there was a decrease in telomeric length (Figure 3D; p = 0.0035), which is consistent with the age-dependent increase in DNA that we and others have reported previously (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2016; Farg et al., 2017). To test whether the telomere attrition observed in the C9ORF72 MNs was associated with a dysregulation in the levels of shelterin complex members, we analyzed the mRNA levels of TFR1, TRF2, and POT1 in iPSC-derived MNs from control subjects and C9ORF72 carriers at different time points: 1 month, 1.5 months, and 2 months. TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 mRNA expression were not significantly different between C9ORF72 and control neurons at any of the time points analyzed (Figures 4A–C). On the other hand, when we analyzed TRF2 and POT1 protein levels, we found no difference between controls and C9ORF72 carriers in 1-month-old MNs (Figures 5A,B), when we analyzed 2-month-old, we found a decrease in TRF2 and POT1 levels in MNs from C9ORF72 carriers as compared to controls (Figures 5C,D), indicating that the G4C2 repeat expansion induced a dysregulation in the expression of key shelterin complex members.

FIGURE 3.

Age-dependent telomere attrition in MNs from C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. (A) Representative images from control and C9ORF72 iPCS-derived MN cultures. qPCR analyses of telomere length quantification in postmitotic MNs at (B) 1, (C) 1.5, and (D) 2 months. A one-way ANOVA was applied to compare MNs at 1 month, 1.5 months, and 2 months, from 3 controls and 3 C9ORF72 iPSC lines. ns, not significant. Scale bar = 20 µm.

FIGURE 4.

mRNA expression of telomere maintenance genes in MNs from C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. qPCR analysis of the relative levels of (A) TRF1, (B) TRF2 and (C) POT1, mRNA. A one-way ANOVA was applied to compare iPSC-derived MNs at 1 month, 1.5 months, and 2 months from 3 control subjects or 3 C9ORF72 carriers from 3 independent differentiation experiments. ns, not significant.

FIGURE 5.

Decreased protein levels of TRF2 and POT1 in 2 month-old-motor neurons. Western blot analyses of (A) TRF2, (B) POT1 in 1-month-old-motor neurons and (C) TRF2, (D) POT1 in 2 month-old-motor neurons from 3 controls and 3 C9ORF72 carriers. Two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was applied to western blot data.

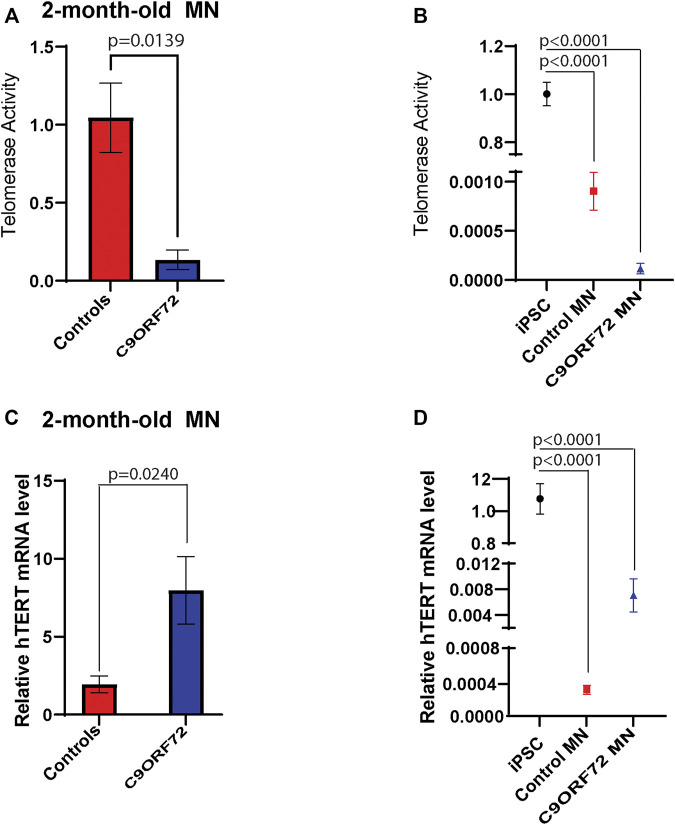

Telomerase Activity and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase mRNA Levels Motor Neurons

During differentiation, telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) levels and telomerase activity are decreased as compared to stem or cancer cells that are actively dividing. In post-mitotic cells, TERT and telomerase levels are low or undetectable. Here we analyzed telomerase activity and hTERT mRNA levels in control and C9ORF72 iPSC-derived MNs. We found a significant decrease in telomerase activity in 2-month-old C9ORF72 MNs as compared to controls (Figure 6A; p = 0.0139), It is important to note that telomerase levels in MNs were significantly lower as compared to iPSCs (Figure 6B; p < 0.0001). When we analyzed hTERT mRNA levels 2-month-old MNs, we found significantly higher hTERT mRNA levels in C9ORF72 MN as compared to controls (Figure 6C; p = 0.0240). Similar to telomerase activity, we found lower levels of hTERT mRNA in MNs as compared to iPSCs (Figure 6D p < 0.0001).

FIGURE 6.

Telomerase activity and hTERT mRNA levels in 2 month-old-motor neurons. qPCR analyses of relative levels of telomerase activity in (A) 2 month-old iPSC-derived MNs from 3 control and 3 C9ORF72 carriers, (B) relative levels of telomerase activity in iPSC lines and 2 month-old iPSC-derived MNs from 3 control and 3 C9ORF72 carriers. qPCR analysis of the relative levels of hTERT in (C) 2-month-old iPSC-derived MNs from 3 control subjects or 3 C9ORF72 carriers, (D) relative levels of hTERT in iPSC lines and 2 month-old iPSC-derived MNs from 3 control and 3 C9ORF72 carriers. Two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction to compare between controls and C9ORF72 MNs and a one-way ANOVA to compare iPSC to iPSC-derived MNs cultures.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to analyze telomere length and shelterin complex expression in iPSC-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 expansion carriers. There is an abundance of evidence that links telomere attrition to neurodegenerative disease (Honig et al., 2006; Scheffold et al., 2016; Guo and Yu, 2019; Nudelman et al., 2019). However, most of these studies have been performed using blood cells or postmortem brain samples (Lukens et al., 2009; Guan et al., 2015). To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzed telomere length in patient-derived iPSC-derived neurons from C9ORF72 repeat expansion carriers. In this study, we benefited from a well-characterized differentiation method that produces NEP, MNP, and highly pure MN populations. First, we analyzed telomere length during motor neuron differentiation and we found no differences in telomere length in NEP between controls and C9ORF72 carriers. Interestingly, when we analyzed MNP, which is the next differentiation stage, we found an increase in telomere length in C9ORF72 carriers as compared to controls. Subsequently, we analyzed the expression of shelterin complex genes and we only found a significant increase in TRF2 mRNA levels on NEP from C9ORF72 carriers. TRF1 and POT1 levels remained unchanged in NEP. There were no differences in TRF1, TRF2 and POT1 mRNA levels at MNP stage. When we analyzed protein levels of TRF2 and POT1, we did not find differences at either the NEP or MNP stage, suggesting that the C9ORF72 repeat expansion induces TRF2 mRNA differential expression but this difference is not reflected at the protein levels, since protein levels remain the same at NEP and MNP in controls and C9ORF72 carriers.

When we analyzed post-mitotic motor neurons at different time points, we found a trend towards a decrease in telomere length in C9ORF72 neurons in 1-month-old and 1.5-month-old MNs when compared to controls. By two months, we saw a significant decrease in telomere length in C9ORF72 MNs. Telomere length has been evaluated in FTD patients with mixed results due to the fact that different sets of samples and subjects with different forms of dementia have been analyzed. For instance, a study that analyzed blood leukocytes from 53 patients with FTD found that telomere length was increased (Kim et al., 2021). However, that study analyzed patients with different dementia variants, including FTD with behavioral variant, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, nonfluent/agrammatic, and only 3 patients with ALS/FTD. On the other hand, a study that analyzed 70 dementia patients found shorter telomeres as compared with controls (Kota et al., 2015). For this reason, we aimed to study telomere length in a disease-relevant and well-characterized neuronal population.

The concerted action of shelterin complex proteins insulates telomeres and avoids DDR reading the linear portion of the chromosome ends as DNA breaks. Our analysis on the expression of shelterin complex members showed no differences in TRF1, TRF2, or POT1 mRNA levels in iPSC-derived MNs at any of the time points analyzed or between control and C9ORF72 conditions. Interestingly, when we analyzed protein levels, we found decreases in TRF2 and POT1 levels in two-month-old MNs. There is evidence of a relationship between shelterin complex dysregulation and telomere shortening. TRF2 levels were found to be decreased in patients with AD (Wu et al., 2019). In addition, treatment with agents that induce ROS reduces levels of POT1 in HK-2 cells (Chuenwisad et al., 2021). Moreover, the decreases in TRF2 and POT1 levels cause unprotected chromosomes to trigger the DDR. We and others have found an increase in the DDR in C9ORF72 neurons, which could be a result of telomere attrition.

During differentiation, TERT levels and telomerase activity are decreased as compared to stem cells that are actively dividing cells. In post-mitotic cells, TERT levels and telomerase activity are low or undetectable (Greenberg et al., 1998). In this study, we analyzed telomerase activity and hTERT mRNA levels in control and C9 iPSC-derived MNs, and we found a significant increase in hTERT mRNA levels in C9ORF72 as compared to controls. It has been reported previously that under metabolic or oxidative stress conditions, TERT levels are increased in neurons (Kang et al., 2004) and astrocytes (Baek et al., 2004). Interestingly, oxidative stress induces TERT protein shuttling from the nucleus to mitochondria and is able to decrease ROS (Ahmed et al., 2008). On the other hand, we found a decrease in telomerase activity in 2-month-old C9ORF72 MNs as compared to controls. It is worth noting that hTERT levels and telomerase activity are significantly lower in MNs as compared to iPSCs, with decreases of 100 and 1000 fold, respectively. For this reason, it will be interesting to explore the non-canonical functions of hTERT in neurons.

It has been demonstrated that the telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n can form G-cuadruplexes (G4). Interestingly, telomere G4 structure formation has been associated with genome instability since it can create mutations and recombination events in cancer cells (Kosiol et al., 2021). The DNA and RNA sequences from the G4C2 repeat in the non-coding region of C9ORF72 can form G4 structures (Fratta et al., 2012), suggesting that G4 structure may also be a contributor to genomic instability in C9ORF72 neurons. Moreover, G4 structures have been identified in many diseases, including progressive myoclonus epilepsy type 1, spinocerebellar ataxia, and other neurodegenerative diseases (Simone et al., 2015). For this reason, it will be interesting to therapeutically target this structure since there are over a thousand small-molecule ligands that can bind to G4 structures (Campbell et al., 2008), and may be valuable as future therapies.

Most of our knowledge on telomere biology comes from studies on dividing cells. However, several studies have shown telomere shortening in non-dividing cells like neurons (Lukens et al., 2009) and muscle cells (Chang et al., 2018). The consequences of telomere attrition in post-mitotic cells is still poorly understood, and it will be of interest to gain more insight into the role of telomere shortening in non-dividing cells like neurons, since this will help to illuminate the causes of neurodegeneration in ALS/FTD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Significance Statement

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are two fatal neurodegenerative diseases that unfortunately have no cure. Therefore, gaining insight into the mechanisms that drive degeneration in ALS and FTD will provide important tools to target and develop therapeutic interventions. We have previously found an increase in DNA damage and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in neurons reprogramed from patients with the C9ORF72 mutation, which is the most common form of familial ALS and FTD. There is evidence of telomere degradation in neurodegenerative diseases, and it is well-established that telomere erosion can cause cell death or senescence. However, the evidence is inconclusive in neurodegenerative disorders, since the studies that evaluated telomere length have been performed in postmortem tissues or blood cells. Here, we analyzed telomere length in patient-derived motor neurons from C9ORF72 carriers, a disease-relevant neuronal type. We found reduced telomere length in mature neurons and dysregulation of the expression of telomere-associated proteins on C9ORF72 neurons as compared to control subjects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fen-Biao Gao from UMass Chan Medical School for the iPSC lines used in this study. We thank Dr. Chris Nelson for helping to edit this manuscript. We thank the Alzheimer’s Association for 2018-AARFD-592264 awarded to RL-G.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

RL-G Designed the experiments; HR and SA performed experiments; RL-G, SA, and MD-H analyzed data; RL-G wrote the paper with input from MD-H and SA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be interpreted as potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ahmed S., Passos J. F., Birket M. J., Beckmann T., Brings S., Peters H., et al. (2008). Telomerase Does Not Counteract Telomere Shortening but Protects Mitochondrial Function under Oxidative Stress. J. Cell Sci 121, 1046–1053. 10.1242/jcs.019372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S., Bu Y., Kim H., Kim H. (2004). Telomerase Induction in Astrocytes of Sprague-Dawley Rat after Ischemic Brain Injury. Neurosci. Lett. 363, 94–96. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N. H., Parkinson G. N., Reszka A. P., Neidle S. (2008). Structural Basis of DNA Quadruplex Recognition by an Acridine Drug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6722–6724. 10.1021/ja8016973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. C. Y., Chang A. C. H., Kirillova A., Sasagawa K., Su W., Weber G., et al. (2018). Telomere Shortening Is a Hallmark of Genetic Cardiomyopathies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9276–9281. 10.1073/pnas.1714538115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuenwisad K., More-Krong P., Tubsaeng P., Chotechuang N., Srisa-Art M., Storer R. J., et al. (2021). Premature Senescence and Telomere Shortening Induced by Oxidative Stress from Oxalate, Calcium Oxalate Monohydrate, and Urine from Patients with Calcium Oxalate Nephrolithiasis. Front. Immunol. 12, 696486. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.696486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M., Mackenzie I. R., Boeve B. F., Boxer A. L., Baker M., Rutherford N. J., et al. (2011). Expanded GGGGCC Hexanucleotide Repeat in Noncoding Region of C9ORF72 Causes Chromosome 9p-Linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon V. S., Deo P., Chua A., Thomas P., Fenech M. (2020). Shorter Telomere Length in Carriers of APOE-Ε4 and High Plasma Concentration of Glucose, Glyoxal and Other Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs). J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1894–1898. 10.1093/gerona/glz203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farg M. A., Konopka A., Soo K. Y., Ito D., Atkin J. D. (2017). The DNA Damage Response (DDR) Is Induced by the C9orf72 Repeat Expansion in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 2882–2896. 10.1093/hmg/ddx170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratta P., Mizielinska S., Nicoll A. J., Zloh M., Fisher E. M. C., Parkinson G., et al. (2012). C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Repeat Associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia Forms RNA G-Quadruplexes. Sci. Rep. 2, 1016. 10.1038/srep01016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freibaum B. D., Lu Y., Lopez-Gonzalez R., Kim N. C., Almeida S., Lee K.-H., et al. (2015). GGGGCC Repeat Expansion in C9orf72 Compromises Nucleocytoplasmic Transport. Nature 525, 129–133. 10.1038/nature14974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg R. A., Allsopp R. C., Chin L., Morin G. B., Depinho R. A. (1998). Expression of Mouse Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase during Development, Differentiation and Proliferation. Oncogene 16, 1723–1730. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J.-Z., Guan W.-P., Maeda T., Guoqing X., Guangzhi W., Makino N. (2015). Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Show Increased Oxidative Stress Markers and Somatic Telomere Length Shortening. Mol. Cell Biochem 400, 183–187. 10.1007/s11010-014-2274-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Yu H. (2019). Leukocyte Telomere Length Shortening and Alzheimer's Disease Etiology. Jad 69, 881–885. 10.3233/jad-190134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig L. S., Schupf N., Lee J. H., Tang M. X., Mayeux R. (2006). Shorter Telomeres are Associated With Mortality in Those With APOE ε4 and Dementia. Ann. Neurol. 30, 181–187. 10.1002/ana.20894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. K., Putnam L., Dufour J., Ylostalo J., Jung J. S., Bunnell B. A. (2004). Expression of Telomerase Extends the Lifespan and Enhances Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells. Stem Cells 22, 1356–1372. 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.-J., Koh S.-H., Ha J., Na D. L., Seo S. W., Kim H.-J., et al. (2021). Increased Telomere Length in Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia Syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 428, 117565. 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosiol N., Juranek S., Brossart P., Heine A., Paeschke K. (2021). G-quadruplexes: a Promising Target for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer 20, 40. 10.1186/s12943-021-01328-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota L. N., Bharath S., Purushottam M., Moily N. S., Sivakumar P. T., Varghese M., et al. (2015). Reduced Telomere Length in Neurodegenerative Disorders May Suggest Shared Biology. Jnp 27, e92–e96. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13100240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gonzalez R., Lu Y., Gendron T. F., Karydas A., Tran H., Yang D., et al. (2016). Poly(GR) in C9ORF72 -Related ALS/FTD Compromises Mitochondrial Function and Increases Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons. Neuron 92, 383–391. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gonzalez R., Yang D., Pribadi M., Kim T. S., Krishnan G., Choi S. Y., et al. (2019). Partial Inhibition of the Overactivated Ku80-dependent DNA Repair Pathway Rescues Neurodegeneration in C9ORF72 -ALS/FTD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 9628–9633. 10.1073/pnas.1901313116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens J. N., Van Deerlin V., Clark C. M., Xie S. X., Johnson F. B. (2009). Comparisons of Telomere Lengths in Peripheral Blood and Cerebellum in Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimer's & Demen. 5, 463–469. 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.05.666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor-Nof M., Shipony Z., Lopez-Gonzalez R., Nakayama L., Zhang Y.-J., Couthouis J., et al. (2021). p53 Is a central Regulator Driving Neurodegeneration Caused by C9orf72 Poly(PR). Cell 184, 689–708. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz-Potoczny M., Lobanova A., Loeb A. M., Kirak O., Olbrich T., Ruiz S., et al. (2021). TRF2-mediated Telomere protection Is Dispensable in Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nature 589, 110–115. 10.1038/s41586-020-2959-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. S., Balakrishnan L., Buncher N. A., Opresko P. L., Bambara R. A. (2012). Telomere Proteins POT1, TRF1 and TRF2 Augment Long-Patch Base Excision Repair In Vitro . Cell Cycle 11, 998–1007. 10.4161/cc.11.5.19483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman K. N. H., Lin J., Lane K. A., Nho K., Kim S., Faber K. M., et al. (2019). Telomere Shortening in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Cohort. Jad 71, 33–43. 10.3233/jad-190010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penev A., Markiewicz-Potoczny M., Sfeir A., Lazzerini Denchi E. (2022). Stem Cells at Odds with Telomere Maintenance and protection. Trends Cell Biol. 10.1016/j.tcb.2021.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton A. E., Majounie E., Waite A., Simón-Sánchez J., Rollinson S., Gibbs J. R., et al. (2011). A Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in C9ORF72 Is the Cause of Chromosome 9p21-Linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarabino D., Broggio E., Gambina G., Corbo R. M. (2017). Leukocyte Telomere Length in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Exp. Gerontol. 98, 143–147. 10.1016/j.exger.2017.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffold A., Holtman I. R., Dieni S., Brouwer N., Katz S.-F., Jebaraj B. M. C., et al. (2016). Telomere Shortening Leads to an Acceleration of Synucleinopathy and Impaired Microglia Response in a Genetic Mouse Model. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 4, 87. 10.1186/s40478-016-0364-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone R., Fratta P., Neidle S., Parkinson G. N., Isaacs A. M. (2015). G-quadruplexes: Emerging Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases and the Non-coding Transcriptome. FEBS Lett. 589, 1653–1668. 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szebényi K., Wenger L. M. D., Sun Y., Dunn A. W. E., Limegrover C. A., Gibbons G. M., et al. (2021). Human ALS/FTD Brain Organoid Slice Cultures Display Distinct Early Astrocyte and Targetable Neuronal Pathology. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1542–1554. 10.1038/s41593-021-00923-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Han D., Zhang J., Li X. (2019). Expression of Telomere Repeat Binding Factor 1 and TRF2 in Alzheimer's Disease and Correlation with Clinical Parameters. Neurol. Res. 41, 504–509. 10.1080/01616412.2019.1580456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Pei Y., Yang Z., Li K., Lou X., Cui W. (2020). Accelerated Telomere Shortening Independent of LRRK2 Variants in Chinese Patients with Parkinson's Disease. aging 12, 20483–20492. 10.18632/aging.103878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Almeida S., Lu Y., Nishimura A. L., Peng L., Sun D., et al. (2013). Downregulation of microRNA-9 in iPSC-Derived Neurons of FTD/ALS Patients with TDP-43 Mutations. PLoS One 8, e76055. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.