Abstract

Microsatellites are repetitive sequences commonly found in the genomes of higher organisms. These repetitive sequences are prone to expansion or contraction, and when microsatellite expansion occurs in the regulatory or coding regions of genes this can result in a number of diseases including many neurodegenerative diseases. Unlike in humans and other organisms, the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum contains an unusually high number of microsatellites. Intriguingly, many of these microsatellites fall within the coding region of genes, resulting in nearly 10,000 homopolymeric repeat proteins within the Dictyostelium proteome. Surprisingly, among the most common of these repeats are polyglutamine repeats, a type of repeat that causes a class of nine neurodegenerative diseases in humans. In this minireview, we summarize what is currently known about homopolymeric repeats and microsatellites in Dictyostelium discoideum and discuss the potential utility of Dictyostelium for identifying novel mechanisms that utilize and regulate regions of repetitive DNA.

Keywords: trinucleotide repeat, neurodegenerative diseases, polyglutamine, microsatellite, Dictyostelium

Introduction

Microsatellites are a universal feature of most organismal genomes, though the prevalence and characteristics of these vary widely between species. These genetic features, sometimes referred to as simple sequence repeats (SSRs), are short tandem repeats composed of 1–6 bp sequences (Ellegren, 2004). SSRs tend to be highly polymorphic and are primarily located within non-coding portions of the genome (Ellegren, 2004). Despite their ubiquity, expansion of microsatellites are known to cause several different diseases. These disease-causing expansions occur in both coding and non-coding regions of the genome, reflecting the wide array of mechanisms by which these microsatellites disrupt normal cellular functions (Ranum and Day, 2002; Orr and Zoghbi, 2007; Brouwer et al., 2009).

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum raises new questions about the function and impact of microsatellites. These questions are raised because the Dictyostelium genome has a massive amount of these features with 11% of its genome composed of SSRs, about a 50-fold enrichment over most other organisms (Eichinger et al., 2005). Interestingly, unlike other organisms that encode mostly dinucleotide repeats, Dictyostelium encodes mostly trinucleotide repeats (Eichinger et al., 2005). The number of tandem repeats of trinucleotides (and hexa-, nona-, etc.) is also extremely high within coding regions resulting in the production of nearly 10,000 proteins that encode SSRs (Eichinger et al., 2005). Surprisingly, unlike in humans, microsatellite expansion within exons does not appear to be detrimental to Dictyostelium (Malinovska et al., 2015; Santarriaga et al., 2015). This raises several questions. How does Dictyostelium maintain genome stability? What are the functional aspects of SSRs? How is protein quality control maintained? Here, we will summarize the current knowledge of SSRs in Dictyostelium and describe the potential for utilizing this unique organism to explore questions in microsatellite biology.

Microsatellite Mutation in Dictyostelium

The expansion and contraction of microsatellites is known to be influenced by both the composition and length of the repetitive sequence, as well as the DNA repair landscape of the cell (Schlötterer and Tautz, 1992; Strand et al., 1993; Sia et al., 1997; Lai and Sun, 2003; Shinde et al., 2003; Tian et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2017). Current models of microsatellite mutation attribute changes in microsatellite length primarily to slippage mutations, a phenomenon in which a newly synthesized DNA strand briefly dissociates during DNA replication but is misaligned after reannealing due to the repetitiveness of the template, resulting in some number of repeats remaining unannealed (Schlötterer and Tautz, 1992; Strand et al., 1993; Sia et al., 1997). This can result in either expansion or contraction of the microsatellite depending on which strand contains the unannealed portion of DNA (Schlötterer and Tautz, 1992; Strand et al., 1993; Sia et al., 1997). It is known that the frequency of slippage mutations occurring is dependent on the length of the repeat unit, the number of repeat units present, and the nucleotide composition of the microsatellite (Sia et al., 1997; Lai and Sun, 2003; Shinde et al., 2003). Also important in slippage mutation is the presence or absence of functional DNA repair, particularly in the mismatch repair pathway, though some have hypothesized that errors in double strand break repair by homologous recombination may also result in changes in microsatellite length (Sia et al., 1997; Richard and Pâques, 2000).

As mentioned previously, the genome of Dictyostelium is highly repetitive with over 11% of its genome being composed of SSRs (Eichinger et al., 2005). The genome is over 75% A + T rich, a value comparable to some other protozoa such as Plasmodium falciparum but far exceeding most other eukaryotes (Eichinger et al., 2005). Some have proposed that this bias is the reason for the notable prevalence of microsatellites in coding regions because it easier for point mutations to result in a codon identical to neighboring codons, thus increasing the likelihood that a region will become prone to slippage mutations (Tian et al., 2011; Scala et al., 2012). Consistent with this, a high rate of 3n indels present in regions without simple sequence repeats were found to occur in Dictyostelium, presumably occurring via slipped strand mispairings (Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). In addition, it was also observed that nearly one-third of indel events occurred in SSRs, primarily in homopolymeric A:T runs (Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). Together these provide one potential explanation for the high number of trinucleotide repeats in Dictyostelium with small repeats potentially being preferentially expanded, resulting in an abundance of SSRs.

Surprisingly, despite having such unusually abundant microsatellites, early studies estimated that Dictyostelium microsatellites tend to accumulate mutations less rapidly than most other eukaryotes (McConnell et al., 2007; Saxer et al., 2012). By these estimates, the low mutation rate would suggest that rapid mutation is not the source of these extensive microsatellites in Dictyostelium, though another possible explanation for the low mutation rates is that expansion and contraction of microsatellites is balanced, thus masking the effects of mutations over several generations (Saxer et al., 2012; Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). In contrast to the early studies, a later study by Kucukyildirim et al. (2020) estimated an indel mutation rate higher than most organisms and attributed this to the high A + T content of the genome. However, in Plasmodium falciparum, a protist with even higher A + T content and lower percentage of the genome composed by SSRs, the indel mutation rate is estimated to be many fold higher than that of Dictyostelium (Hamilton et al., 2017; Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). It is evident from these conflicting findings that more research is needed to uncover the mutational dynamics of SSRs in Dictyostelium.

It is possible that Dictyostelium has evolved highly efficient DNA repair pathways to prevent additional mutations (McConnell et al., 2007; Saxer et al., 2012). Being a soil-dwelling microbe means that Dictyostelium cells come into contact with numerous mutagenic compounds that would select for rigorous DNA repair mechanisms (Deering, 1994). Dictyostelium also require efficient DNA repair mechanisms due to the fact that they are professional phagocytes, a process that exposes the cells to constant challenges from the bacteria consumed (Deering, 1968; Hsu et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009; Pontel et al., 2016). Importantly, Dictyostelium shows evidence of conservation of multiple eukaryotic DNA repair pathways, including some which were once thought to be limited to vertebrate animals (Table 1; Hsu et al., 2006; Pears and Lakin, 2014; Pears et al., 2021). Though much of the research on DNA repair in Dictyostelium has been focused on the processes of homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining (Katz and Ratner, 1988; Hsu et al., 2006, 2011), Dictyostelium also contains several orthologs of genes known to be associated with mismatch repair. However, these have not been extensively studied in Dictyostelium. Given what we know of the relevance of these pathways in microsatellite mutation in other organisms, it is important to consider that there may be insights to be had from studying these processes in an organism such as Dictyostelium that demonstrates remarkably lower microsatellite mutation rates than would be expected of a highly repetitive genome.

TABLE 1.

Orthologs of human and S. cerevisiae DNA repair genes in Dictyostelium.

| Gene name | Dictyostelium gene ID | Human gene ID | Yeast gene ID |

|

| |||

| Homologous recombination | |||

| blm | DDB_G0292130 | HGNC:1058 | YMR190C |

| exo1 | DDB_G0291570 | HGNC:3511 | YDR263C |

| nse1 | DDB_G0279231 | HGNC:29897 | YLR007W |

| rad51 | DDB_G0273139 DDB_G0273611 |

HGNC:9817 | YER095W |

| rad52 | DDB_G0269406 | HGNC:9824 | YML032C |

| smc5 | DDB_G0290919 | HGNC:20465 | YOL034W |

| smc6 | DDB_G0288993 | HGNC:20466 | YLR383W |

| wrn | DDB_G0268512 | HGNC:12791 | YMR190C |

| xpf | DDB_G0284419 | HGNC:3436 | YPL022W |

| xrcc2 | DDB_G0290297 | HGNC:12829 | – |

|

| |||

| Non-homologous end joining | |||

|

| |||

| adprt1A (PARP1) | DDB_G0278741 | HGNC:270 | – |

| adprt2 (PARP2) | DDB_G0292820 | HGNC:272 | – |

| dclre1(Artemis-related) | DDB_G0277755 | HGNC:17660 | YMR137C |

| dnapkcs | DDB_G0281167 | HGNC:9413 | – |

| ku70 | DDB_G0286069 | HGNC:4055 | YMR284W |

| ku80 | DDB_G0286303 | HGNC:12833 | YMR106C |

| lig4 | DDB_G0292760 | HGNC:6601 | YOR005C |

| mre11 | DDB_G0293546 | HGNC:7230 | YMR224C |

| pnkp | DDB_G0281229 | HGNC:9154 | YMR156C |

| rad50 | DDB_G0292786 | HGNC:9816 | YNL250W |

| xrcc4 | DDB_G0278203 | HGNC:12831 | – |

|

| |||

| Mismatch repair | |||

|

| |||

| msh1 | DDB_G0275999 | – | YHR120W |

| msh2 | DDB_G0275809 | HGNC:7325 | YOL090W |

| msh3 | DDB_G0281683 | HGNC:7326 | YCR092C |

| msh4 | DDB_G0283957 | HGNC:7327 | YFL003C |

| msh5 | DDB_G0284747 | HGNC:7328 | YDL154W |

| msh6 | DDB_G0268614 | HGNC:7329 | YDR097C |

| mlh1 | DDB_G0287393 | HGNC:7127 | YMR167W |

| mlh3 | DDB_G0283883 | HGNC:7128 | YPL164C |

| pcna | DDB_G0287607 | HGNC:8729 | YBR088C |

| pms1 | DDB_G0283981 | HGNC:9122 | YNL082W |

| rfc1 | DDB_G0285961 | HGNC:9969 | YOR217W |

Do Simple Sequence Repeats Serve a Function in Dictyostelium?

In recent years, more and more research has been conducted to study the functional aspects of homopolymeric amino acid sequences, low-complexity domains, and prion-like domains within proteins (Alberti, 2017; Alberti et al., 2019; Franzmann and Alberti, 2019b; Lau et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021). While some studies have found evidence for beneficial impacts of having these repetitive domains, research has not yet been conducted to assess the function of any of these features in Dictyostelium. Instead, the research has been focused on looking for evidence of selection acting on these domains through genomic level analysis of SSR distribution and mutational patterns (Eichinger et al., 2005; Saxer et al., 2012; Scala et al., 2012; Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). If SSRs serve a function in Dictyostelium, we would expect to see evidence of selection acting upon them. However, the analyses that have been performed and the conclusions they have drawn have left this question unanswered. There are many arguments for and against the presence of selection acting on SSRs.

One characteristic that favors the idea that selection is in effect is that SSRs within coding regions are often read in frames that disproportionately favor one amino acid. For example, proteins are more likely to homopolymeric runs of asparagine or glutamine than the amino acids that would be produced in the other two reading frames. Furthermore, mutations within these SSRs are often synonymous, indicating that a particular amino acid is favored over alternatives (Eichinger et al., 2005). Polyasparagine and polyglutamine tracts are overrepresented in regulatory factors such as kinases, transcription factors, and RNA binding proteins, indicating that these repetitive regions may play some sort of regulatory role within the cell (Eichinger et al., 2005). Dictyostelium also has a low mutation rate when compared to organisms with similar genome composition, indicating that there may be selection acting to counter the effects of genetic drift in this organism (Kucukyildirim et al., 2020).

In contrast, there is high variation and genetic diversity among amino acid repeats in coding sequences, which is unexpected in protein sequences under purifying selection. Additionally, SSRs in coding regions are equal as variable as SSRs in non-coding regions, indicating that there is not stronger selection occurring as would be expected for a functional protein sequence (Scala et al., 2012). The four amino acids most commonly found in homopolymeric tracts (asparagine, glutamine, threonine, and serine) are all polar and hydrophilic, indicating that they may be more likely to reside on the outer parts of a protein vs. the hydrophobic core (Eichinger et al., 2005; Scala et al., 2012). Low mutation rates may have evolved as a mechanism to protect cells from deleterious expansions or contractions within the genome rather than as a mechanism to preserve function in coding SSRs (Kucukyildirim et al., 2020). It is clear that additional study is required to draw a more definite conclusion on whether selection is acting upon SSRs in Dictyostelium. Additionally, it would be helpful to conduct directly targeted studies on the results of removing the SSRs within some of the proteins they are found in and assessing whether there are effects on fitness.

What Can We Learn From Dictyostelium Microsatellites?

There are several human diseases associated with microsatellite expansion (Ranum and Day, 2002; Orr and Zoghbi, 2007; Brouwer et al., 2009). However, despite the many orthologs of human disease-associated genes and the seeming lack of harmful effects from its highly repetitive genome, relatively little research has been done in Dictyostelium on diseases caused by microsatellite expansion (Myre et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Myre, 2012; Olmos et al., 2020; Haver and Scaglione, 2021). One microsatellite-associated disease that has been modeled in Dictyostelium is Huntington’s Disease. In this disease, expansion of a CAG repeat encodes a homopolymeric polyglutamine tract in the huntingtin protein (HTT) that exceeds beyond a pathogenic threshold and is prone to aggregation (Orr and Zoghbi, 2007). An ortholog of HTT exists in Dictyostelium, and deletion of this protein results in several abnormal phenotypes including deficiencies in chemotaxis, flaws in cytokinesis, and improper cell patterning during multicellular development (Myre et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Bhadoriya et al., 2019). Dictyostelium HTT lacks the polyglutamine tract present in exon 1 of human HTT, instead containing a polyglutamine tract further downstream (Myre et al., 2011). Because of this Dictyostelium may serve as an interesting organism to use in studying the effects of the presence and absence of polyglutamine tracts in the HTT protein. Dictyostelium may also serve as an ideal model to assess the impacts of polyglutamine tract length on protein function, a topic of interest in recent studies (Iennaco et al., 2022).

Furthermore, if there are unknown factors in Dictyostelium that mitigate the deleterious effects of expanded microsatellites, we could gain novel insights on how to alleviate the impact of these in human cells. The proteome of Dictyostelium is rich in proteins with prion-like domains, including homopolymeric polyglutamine and polyasparagine tracts as well as low complexity domains consisting of alternating amino acid residues (Eichinger et al., 2005; Malinovska and Alberti, 2015). However, Dictyostelium has been shown to be resistant to polyglutamine aggregation (Malinovska et al., 2015; Santarriaga et al., 2015). Similarly, Dictyostelium has not been found to suffer deleterious effects from its many polyasparagine-rich or low complexity domains, though these are common features in prion proteins (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012; Franzmann and Alberti, 2019a). This begs the question of how Dictyostelium cells are able to tolerate these usually unstable proteins while other organisms would face protein aggregation and cytotoxicity. Has Dictyostelium evolved novel protein quality control mechanisms to maintain these proteins in a soluble, folded state? While this is largely an unanswered question, some evidence exists for novel mechanisms that suppress polyglutamine aggregation (Santarriaga et al., 2018). Potentially there are other mechanisms also involved in mitigating deleterious effects of these genes such as alternative splicing or gene silencing. Further research is certainly needed to clarify the mechanisms of maintaining protein homeostasis within this organism.

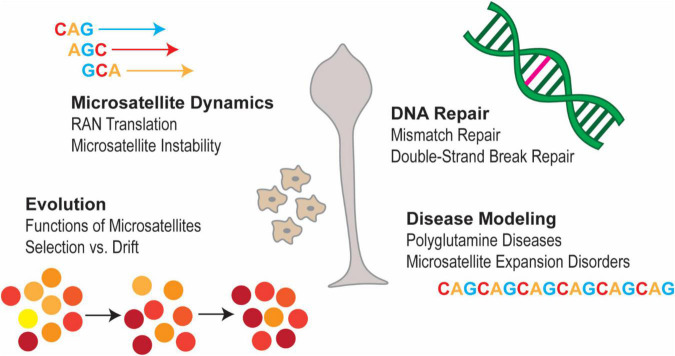

Furthermore, due to its repeat-rich genome Dictyostelium is an interesting organism to investigate cellular phenomena associated with expanded microsatellites in a tractable and easy-to-use organism (Figure 1; Bozzaro, 2013; Pears and Lakin, 2014; Malinovska and Alberti, 2015; Haver and Scaglione, 2021; Pears and Gross, 2021; Pears et al., 2021). Here we can begin to address many questions of relevance to human health. For instance, is there evidence of Repeat Associated Non-ATG (RAN) translation occurring in Dictyostelium? RAN translation is a phenomenon in which transcripts containing certain SSRs can initiate translation without the presence of an AUG start codon (Zu et al., 2011; Cleary and Ranum, 2014). These transcripts can be translated in multiple frames, leading to the production of proteins which vary in length and composition. This process has been implicated in a number of microsatellite-expansion diseases (Zu et al., 2011; Cleary and Ranum, 2014). RAN translation has not yet been studied in Dictyostelium, though given its highly repetitive genome and its experimental tractability, this organism would be an interesting candidate for studying this phenomenon in vivo and may provide unique insight into physiological functions of RAN translation. Additionally, because Dictyostelium is resistant to the deleterious effects of microsatellite expansion (Malinovska et al., 2015; Santarriaga et al., 2015), it provides a unique platform for studying the cellular dynamics of SSRs without cytotoxicity.

FIGURE 1.

Areas to study SSRs in Dictyostelium. Dictyostelium has several unique properties that make it a compelling model in which to study the biology of SSRs. These properties include, but are not limited to, its highly repetitive genome, its genetic tractability, its high degree of genetic conservation with humans and its apparent resistance to the toxic effects of microsatellite expansion. Thus, Dictyostelium presents a unique opportunity to gain insights into the processes that regulate microsatellites and the biological consequences of having these repetitive sequences in the genome.

Another set of processes that would be advantageous to study in Dictyostelium are the various DNA repair pathways responsible for maintaining the integrity of the genome. As mentioned previously, Dictyostelium contains several orthologs to human DNA repair genes (Table 1), including some that are absent in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other model organisms (Hsu et al., 2006; Pears and Lakin, 2014; Pears et al., 2021). Defects in DNA repair, particularly in the mismatch repair pathway, have been implicated in microsatellite mutations in several classes of disease. These include but are not limited to neurodegenerative diseases, in which microsatellites can become expanded and encode aggregation-prone pathogenic proteins, and various cancers, in which microsatellite instability can contribute to hypermutability within malignant growths (Loeb, 1994; Boyer et al., 1995; Karran, 1996; Thomas et al., 1996; Dietmaier et al., 1997; Shah et al., 2010; Jeppesen et al., 2011; Yamamoto and Imai, 2015; Schmidt and Pearson, 2016; Cortes-Ciriano et al., 2017; Baretti and Le, 2018; Maiuri et al., 2019). In cancer, defects in mismatch repair are especially important predictors of efficacy for certain chemotherapeutics and may require special therapies to address (Martin et al., 2010; Li and Martin, 2016). The Dictyostelium genome contains orthologs of several human genes known to be involved in mismatch repair, as well as other DNA repair pathways. However, little to no research has been done on mismatch repair in this organism. Dictyostelium would be a good model for studying these highly conserved processes in a simple and genetically tractable model. In doing so, we could gain vital insights on the genetic and biochemical factors that play a role in eukaryotic mismatch repair, allowing us a better understanding of the mechanisms driving human diseases such as hypermutability in cancer cells and microsatellite expansion in neurodegenerative disorders. There is even potential for discovery of novel DNA repair mechanisms that have evolved in Dictyostelium or have remained undiscovered in higher eukaryotes.

Conclusion

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is unique among eukaryotic model organisms in that it features a highly repetitive genome without being known to demonstrate the deleterious impacts of expanded SSRs. However, several important aspects of microsatellite biology, including instability, behavior, and function have not been widely studied in this organism. Understanding biological processes in organisms with unique biological attributes can provide insights that provide novel insight into how nature has dealt with issues that cause disease in humans. Therefore, utilizing the unique benefits of model organisms such as Dictyostelium is important for expanding our knowledge of the processes driving cellular function.

Author Contributions

FW wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. KS and FW revised and edited the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NS112191 and GM119544 to KS and the Diverse Scientists in Ataxia Predoctoral Fellowship from the National Ataxia Foundation to FW.

References

- Alberti S. (2017). Phase separation in biology. Curr. Biol. 27 R1097–R1102. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S., Gladfelter A., Mittag T. (2019). Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 176 419–434. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baretti M., Le D. T. (2018). DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 189 45–62. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadoriya P., Jain M., Kaicker G., Saidullah B., Saran S. (2019). Deletion of Htt cause alterations in cAMP signaling and spatial patterning in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 18858–18871. 10.1002/jcp.28524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J. C., Umar A., Risinger J. I., Lipford J. R., Kane M., Yin S., et al. (1995). Microsatellite Instability, Mismatch Repair Deficiency, and Genetic Defects in Human Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Res. 55:6063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzaro S. (2013). The model organism Dictyostelium discoideum. Met. Molecular Biol. 983 17–37. 10.1007/978-1-62703-302-2_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer J. R., Willemsen R., Oostra B. A. (2009). Microsatellite repeat instability and neurological disease. Bioessays 31 71–83. 10.1002/bies.080122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary J. D., Ranum L. P. W. (2014). Repeat associated non-ATG (RAN) translation: new starts in microsatellite expansion disorders. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 26 6–15. 10.1016/j.gde.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Ciriano I., Lee S., Park W.-Y., Kim T.-M., Park P. J. (2017). A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat. Commun. 8:15180. 10.1038/ncomms15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering R. A. (1968). Dictyostelium discoideum: a Gamma-Ray Resistant Organism. Science 162 1289–1290. 10.1126/science.162.3859.1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering R. A. (1994). Dictyostelium discoideum, a lower eukaryote model for the study of DNA repair: implications for the role of DNA-damaging chemicals in the evolution of repair proficient cells. Adv. Space Res. 14 389–393. 10.1016/0273-1177(94)90492-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietmaier W., Wallinger S., Bocker T., Kullmann F., Fishel R., Rüschoff J. (1997). Diagnostic Microsatellite Instability: definition and Correlation with Mismatch Repair Protein Expression. Cancer Res. 57:4749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger L., Pachebat J. A., Glöckner G., Rajandream M. A., Sucgang R., Berriman M., et al. (2005). The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435 43–57. 10.1038/nature03481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H. (2004). Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5 435–445. 10.1038/nrg1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann T. M., Alberti S. (2019b). Protein Phase Separation as a Stress Survival Strategy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 11:a034058. 10.1101/cshperspect.a034058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann T. M., Alberti S. (2019a). Prion-like low-complexity sequences: key regulators of protein solubility and phase behavior. J. Biol. Chem. 294 7128–7136. 10.1074/jbc.TM118.001190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Shi X., Wang X. (2021). RNA and liquid-liquid phase separation. Non Coding RNA Res. 6 92–99. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. L., Claessens A., Otto T. D., Kekre M., Fairhurst R. M., Rayner J. C., et al. (2017). Extreme mutation bias and high AT content in Plasmodium falciparum. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 1889–1901. 10.1093/nar/gkw1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haver H. N., Scaglione K. M. (2021). Dictyostelium discoideum as a Model for Investigating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Cellular Neurosci. 15:759532. 10.3389/fncel.2021.759532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D.-W., Gaudet P., Hudson J. J. R., Pears C. J., Lakin N. D. D. N. A. (2006). Damage Signalling and Repair in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Cycle 5 702–708. 10.4161/cc.5.7.2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D.-W., Kiely R., Couto C. A.-M., Wang H.-Y., Hudson J. J. R., Borer C., et al. (2011). DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 124 1655–1663. 10.1242/jcs.081471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iennaco R., Formenti G., Trovesi C., Rossi R. L., Zuccato C., Lischetti T., et al. (2022). The evolutionary history of the polyQ tract in huntingtin sheds light on its functional pro-neural activities. Cell Death Diff. 29 293–305. 10.1038/s41418-021-00914-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen D. K., Bohr V. A., Stevnsner T. (2011). DNA repair deficiency in neurodegeneration. Prog. Neurobiol. 94 166–200. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran P. (1996). Microsatellite instability and DNA mismatch repair in human cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 7 15–24. 10.1006/scbi.1996.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz K. S., Ratner D. I. (1988). Homologous recombination and the repair of double-strand breaks during cotransformation of Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 2779–2786. 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2779-2786.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukyildirim S., Behringer M., Sung W., Brock D. A., Doak T. G., Mergen H., et al. (2020). Low Base-Substitution Mutation Rate but High Rate of Slippage Mutations in the Sequence Repeat-Rich Genome of Dictyostelium discoideum. G3 10 3445–3452. 10.1534/g3.120.401578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y., Sun F. (2003). The Relationship Between Microsatellite Slippage Mutation Rate and the Number of Repeat Units. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20 2123–2131. 10.1093/molbev/msg228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau Y., Oamen H. P., Caudron F. (2020). Protein Phase Separation during Stress Adaptation and Cellular Memory. Cells 9:1302. 10.3390/cells9051302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. K. H., Martin A. (2016). Mismatch Repair and Colon Cancer: mechanisms and Therapies Explored. Trends Mol. Med. 22 274–289. 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman S. W., Chernoff Y. O. (2012). Prions in Yeast. Genetics 191 1041–1072. 10.1534/genetics.111.137760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb L. A. (1994). Microsatellite instability: marker of a mutator phenotype in cancer. Cancer Res. 54 5059–5063. Epub 1994/10/01. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri T., Suart C. E., Hung C. L. K., Graham K. J., Barba Bazan C. A., Truant R. D. N. A. (2019). Damage Repair in Huntington’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotherapeutics 16 948–956. 10.1007/s13311-019-00768-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovska L., Alberti S. (2015). Protein misfolding in Dictyostelium: using a freak of nature to gain insight into a universal problem. Prion 9 339–346. 10.1080/19336896.2015.1099799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovska L., Palm S., Gibson K., Verbavatz J.-M., Alberti S. (2015). Dictyostelium discoideum has a highly Q/N-rich proteome and shows an unusual resilience to protein aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 E2620–E2629. 10.1073/pnas.1504459112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. A., Lord C. J., Ashworth A. (2010). Therapeutic Targeting of the DNA Mismatch Repair Pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 16:5107. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell R., Middlemist S., Scala C., Strassmann J. E., Queller D. C. (2007). An Unusually Low Microsatellite Mutation Rate in Dictyostelium discoideum, an Organism With Unusually Abundant Microsatellites. Genetics 177 1499–1507. 10.1534/genetics.107.076067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myre M. A. (2012). Clues to γ-secretase, huntingtin and Hirano body normal function using the model organism Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biomed. Sci. 19:41. 10.1186/1423-0127-19-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myre M. A., Lumsden A. L., Thompson M. N., Wasco W., MacDonald M. E., Gusella J. F. (2011). Deficiency of Huntingtin Has Pleiotropic Effects in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002052. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos J., Pignataro M. F., Benítez dos Santos A. B., Bringas M., Klinke S., Kamenetzky L., et al. (2020). A Highly Conserved Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Machinery between Humans and Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum: the Characterization of Frataxin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:6821. 10.3390/ijms21186821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (2007). Trinucleotide Repeat Disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30 575–621. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears C. J., Gross J. D. (2021). Microbe Profile: dictyostelium discoideum: model system for development, chemotaxis and biomedical research. Microbiology 167 10.1099/mic.0.001040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears C. J., Lakin N. D. (2014). Emerging models for DNA repair: dictyostelium discoideum as a model for nonhomologous end-joining. DNA Repair 17 121–131. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears C. J., Brustel J., Lakin N. D. (2021). Dictyostelium discoideum as a Model to Assess Genome Stability Through DNA Repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:752175. 10.3389/fcell.2021.752175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontel L. B., Langenick J., Rosado I. V., Zhang X.-Y., Traynor D., Kay R. R., et al. (2016). Xpf suppresses the mutagenic consequences of phagocytosis in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 129 4449–4454. 10.1242/jcs.196337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranum L. P. W., Day J. W. (2002). Dominantly inherited, non-coding microsatellite expansion disorders. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12 266–271. 10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00297-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard G.-F., Pâques F. (2000). Mini- and microsatellite expansions: the recombination connection. EMBO Report 1 122–126. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarriaga S., Haver H. N., Kanack A. J., Fikejs A. S., Sison S. L., Egner J. M., et al. (2018). SRCP1 Conveys Resistance to Polyglutamine Aggregation. Mol. Cell 71 216–28.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarriaga S., Petersen A., Ndukwe K., Brandt A., Gerges N., Bruns Scaglione J., et al. (2015). The Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum Is Highly Resistant to Polyglutamine Aggregation. J. Biolol. Chem. 290 25571–25578. 10.1074/jbc.M115.676247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxer G., Havlak P., Fox S. A., Quance M. A., Gupta S., Fofanov Y., et al. (2012). Whole Genome Sequencing of Mutation Accumulation Lines Reveals a Low Mutation Rate in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS One 7:e46759. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scala C., Tian X., Mehdiabadi N. J., Smith M. H., Saxer G., Stephens K., et al. (2012). Amino Acid Repeats Cause Extraordinary Coding Sequence Variation in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS One 7:e46150. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer C., Tautz D. (1992). Slippage synthesis of simple sequence DNA. Nucleic. Acids Res. 20 211–215. 10.1093/nar/20.2.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. H. M., Pearson C. E. (2016). Disease-associated repeat instability and mismatch repair. DNA Repair 38 117–126. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. N., Hile S. E., Eckert K. A. (2010). Defective Mismatch Repair, Microsatellite Mutation Bias, and Variability in Clinical Cancer Phenotypes. Cancer Res. 70:431. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde D., Lai Y., Sun F., Arnheim N. (2003). Taq DNA polymerase slippage mutation rates measured by PCR and quasi-likelihood analysis: (CA/GT)n and (A/T)n microsatellites. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 974–980. 10.1093/nar/gkg178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia E. A., Kokoska R. J., Dominska M., Greenwell P., Petes T. D. (1997). Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on repeat unit size and DNA mismatch repair genes. Mol. Cell Biol. 17 2851–2858. 10.1128/MCB.17.5.2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M., Prolla T. A., Liskay R. M., Petes T. D. (1993). Destabilization of tracts of simple repetitive DNA in yeast by mutations affecting DNA mismatch repair. Nature 365 274–276. 10.1038/365274a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. C., Umar A., Kunkel T. A. (1996). Microsatellite instability and mismatch repair defects in cancer cells. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. 350 201–205. 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X., Strassmann J. E., Queller D. C. (2011). Genome Nucleotide Composition Shapes Variation in Simple Sequence Repeats. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 899–909. 10.1093/molbev/msq266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Steimle P. A., Ren Y., Ross C. A., Robinson D. N., Egelhoff T. T., et al. (2011). Dictyostelium huntingtin controls chemotaxis and cytokinesis through the regulation of myosin II phosphorylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 22 2270–2281. 10.1091/mbc.e10-11-0926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Imai K. (2015). Microsatellite instability: an update. Archives Toxicol. 89 899–921. 10.1007/s00204-015-1474-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-Y., Langenick J., Traynor D., Babu M. M., Kay R. R., Patel K. J. (2009). Xpf and Not the Fanconi Anaemia Proteins or Rev3 Accounts for the Extreme Resistance to Cisplatin in Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000645. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T., Gibbens B., Doty N. S., Gomes-Pereira M., Huguet A., Stone M. D., et al. (2011). Non-ATG–initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc.Nat. Acad. Sci.U. S. A. 108:260. 10.1073/pnas.1013343108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]