Abstract

Centrilobular emphysema (CLE) and paraseptal emphysema (PSE) are observed in smokers with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm, defined as the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ≥0.7 and FEV1 <80%), but their prevalence and physiological impacts remain unestablished. This multicentre study aimed to investigate its prevalence and to test whether emphysema subtypes are differently associated with physiological impairments in smokers with PRISm.

Both never- and ever-smokers aged ≥40 years who underwent computed tomography (CT) for lung cancer screening and spirometry were retrospectively and consecutively enrolled at three hospitals and a clinic. Emphysema subtypes were visually classified according to the Fleischner system. Air-trapping was assessed as the ratio of FVC to total lung capacity on CT (TLCCT).

In 1046 never-smokers and 772 smokers with ≥10 pack-years, the prevalence of PRISm was 8.2% and 11.3%, respectively. The prevalence of PSE and CLE in smokers with PRISm was comparable to that in smokers with normal spirometry (PSE 43.7% versus 36.2%, p=1.00; CLE 46.0% versus 31.8%, p=0.21), but higher than that in never-smokers with PRISm (PSE 43.7% versus 1.2%, p<0.01; CLE 46% versus 4.7%, p<0.01) and lower than that in smokers with airflow limitation (PSE 43.7% versus 71.0%, p<0.01; CLE 46% versus 79.3%, p<0.01). The presence of CLE, but not PSE, was independently associated with reduced FVC/TLCCT in smokers with PRISm.

Both PSE and CLE were common, but only CLE was associated with air-trapping in smokers with PRISm, suggesting different physiological roles of these emphysema subtypes.

Short abstract

Centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema are observed in 43–46% of smokers with preserved ratio impaired spirometry. Centrilobular emphysema, but not paraseptal emphysema, is closely associated with air-trapping in these smokers. https://bit.ly/3Ky6LDy

Introduction

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), defined as reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) without airflow limitation on spirometry, is increasingly recognised as a major nonobstructive spirometry disorder [1]. The prevalence of PRISm is 7.1–12.5% in adults [2–4] and the presence of PRISm is associated with higher risk of mortality in never- and ever-smokers [2, 4]. In smokers, PRISm is also considered the transitional state to COPD that is characterised by airflow limitation on spirometry and persistent respiratory symptoms [2, 5]. However, the management of smokers with PRISm is still challenging, due to the clinically heterogenous manifestations. Indeed, a subgroup of smokers with PRISm could develop COPD and show greater mortality than smokers with normal spirometry, but other smokers with PRISm could remain clinically stable over time and even return to normal on follow-up spirometry [3, 6]. Therefore, further understanding of clinical features is warranted to improve the outcomes of PRISm.

Computed tomography (CT) is widely used to screen for lung cancer in real-world practice, providing structural information on the airway and parenchyma simultaneously. A prior study showed that radiological abnormalities of the lungs and chest wall such as paraseptal emphysema (PSE), airway wall thickening, diaphragm eventration and smaller transverse internal thoracic diameter are more frequent in smokers with PRISm than those with normal spirometry [7]. Subsequently, the Fleischner Society published a visual classification system for emphysema [8] to describe the localisation of centrilobular emphysema (CLE), PSE and panlobular emphysema on CT. The use of this system has enabled showing that CLE and PSE are common in smokers with and without airflow limitation [9, 10]. Moreover, CLE is associated with airflow limitation, lung hyperinflation and exacerbation frequency, and even mild signs of CLE predict poor prognosis, whereas PSE is less associated with physiological impairments than CLE [10–12]. These results suggest that the differential emphysema subtypes may contribute to the heterogeneous presentations of smokers with PRISm.

Air-trapping predicts adverse respiratory outcome and progression to COPD in smokers without airflow limitation [13, 14] and the ratio of forced vital capacity (FVC) to total lung capacity on CT (TLCCT) as a conceptual surrogate for air-trapping predicts future worsening of symptoms, exacerbation and progression to COPD in smokers with PRISm [15]. However, little is known about the morphological basis on air-trapping in these smokers. Therefore, this study tested the hypothesis that CLE and PSE would differentially affect physiological function in smokers with PRISm. Specifically, the study aimed 1) to explore whether the prevalence of CLE and PSE in smokers with PRISm differs from that in never-smokers with PRISm and smokers with normal spirometry and airflow limitation; and 2) to test whether CLE and PSE are associated with physiological impairments, particularly air-trapping, in smokers with PRISm.

Material and methods

Study design (subjects)

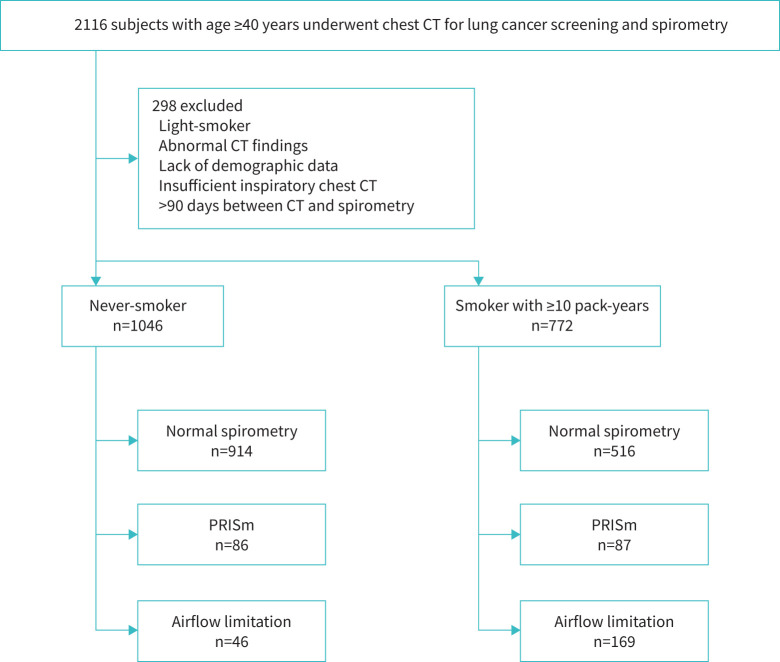

This was a multicentre retrospective study conducted in three hospitals (Tsukuba Medical Center, Kitano Hospital and Takeda Hospital) and a general clinic (Terada Clinic) in Japan. In Japan, hospitals and clinics provide medical checkup programmes in which chest CT scans for lung cancer screening are offered to all adults regardless of smoking status. In this study, we consecutively enrolled never- and ever-smokers aged ≥40 years who underwent inspiratory CT for lung cancer screening and spirometry. Subjects with a history of lung resection, chest CT abnormalities extending to more than one lobe (such as consolidations, atelectasis, tumours, pneumothorax and thoracic deformity), missing information on smoking status or light-smokers (<10 pack-years), >90 days between spirometry and CT scanning or insufficient inspiratory chest CT (defined as FVC>TLCCT [15]) were excluded (figure 1). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committees of Kyoto University Hospital, Tsukuba Medical Center, Kitano Hospital and Takeda Hospital (approval R1660-3 and R2751). Written consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

FIGURE 1.

Study population flow chart. CT: computed tomography; PRISm: preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

CT acquisition, spirometry and TLCCT

All chest CT scans were acquired at full inspiration. Images at 0.5–1.25 mm slice thickness were reconstructed using sharp kernels. Spirometry was conducted without bronchodilator and evaluated in each facility by well-trained technicians according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement [16]. Predicted FEV1 and FVC values were calculated using the LMS (lambda, mu, sigma) method reference equations taking age, gender and height into account [17]. Subjects were classified as having PRISm (FEV1/FVC ≥0.7 and FEV1 <80% predicted), airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC <0.7) or normal spirometry (controls; FEV1/FVC ≥0.7 and FEV1 ≥80% pred). TLCCT was calculated on full inspiratory CT using a Synapse Vincent volume analyser (Fujifilm Medical, Tokyo, Japan), and TLCCT % predicted was calculated based on the predicted values [18]. Air-trapping was assessed by the ratio of FVC to TLCCT, as reported previously [15]. A lower FVC/TLCCT indicates more severe air-trapping. Additionally, validation of FVC/TLCCT as a measure of air-trapping was performed using full inspiratory and end-tidal expiratory CT available from a part of the study population who also participated in a different ongoing prospective airway disease cohort. By using paired inspiratory and expiratory CT, well-established CT markers for air-trapping, including expiratory low attenuation volume percentage, expiratory mean lung density and the ratio of expiratory to inspiratory mean lung density ratio were calculated [19]. In the study, smokers aged ≥40 years underwent a pair of inspiratory and expiratory chest CT scans with written informed consent [20].

Visual CT analysis

Six CT-experienced pulmonologists with ≥5 years’ experience and a chest radiologist with 15 years’ experience performed visual emphysema analysis based on the Fleischner Society classification system [8]. The images were viewed at window width 700 HU and window level −750 HU according to the Fleischner Society's recommendation [8]. CLE was classified as trace, mild, moderate, confluent or advanced destructive, while PSE was classified as mild or substantial [8]. The category of panlobular emphysema was not used in this study, as it is applied to patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency [8]. Before assessing visual emphysema score in the study population, the analysts scored training CT datasets and reviewed substantial discordance to obtain consensus. Each CT scan was assessed by two CT-experienced pulmonologists without knowledge of clinical information and the discordances were adjudicated by a chest radiologist. Further details are provided in the supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

The weighted κ-coefficient was calculated for interobserver variability in the visual emphysema assessments. The severity of CLE (none/trace/mild/moderate/confluent/advanced destructive) was weighted from 0 to 5, and that of PSE (none/mild/substantial) was weighted from 0 to 2. Data are expressed as mean±sd unless indicated. Subjects’ characteristics were compared using Fisher's exact test or Chi-squared test for categorical data and the t-test for continuous variables. The Bonferroni correction method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Additionally, the question of whether the presence of PSE and CLE could affect FVC/TLCCT was explored using multivariable linear regression models that included age, gender, body mass index, smoking pack-years (as a dichotomous variable, <20 or ≥20 pack-years), smoking status, facilities and the presence of PSE/CLE as independent variables. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.0.1 and JMP Pro version 16.1.0. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Interobserver agreement and reliability of air-trapping index

Interobserver agreement for grades of PSE and CLE ranged from moderate to almost perfect. The weighted κ-coefficients for grades of PSE ranged from 0.73 to 0.94 and those of CLE ranged from 0.83 to 0.99 (supplementary table S1). In smokers who also participated in a different prospective study with written informed consent and underwent a pair of inspiratory and expiratory CT scans (n=67), FVC/TLCCT was well correlated with low attenuation volume percentage under −856 HU in expiratory CT, which is an established marker of air-trapping (supplementary tables S2 and S3) [19].

Clinical and radiological characteristics of never-smokers and smokers with normal spirometry, PRISm and airflow limitation

As shown in figure 1, 1818 subjects (1091 male and 727 female) were divided into 1046 never-smokers and 772 substantial smokers (with ≥10 pack-years). Never-smokers and smokers were further classified into those with normal spirometry, PRISm and airflow limitation, and their features are compared in table 1. The prevalence of PRISm and airflow limitation in smokers was higher than that in never-smokers (11.3% versus 8.2% for PRISm and 21.9% versus 4.4% for airflow limitation, respectively). The pulmonary functions of PRISm in smokers did not differ from those in never-smokers. For any lung function category, the prevalence of PSE and CLE was higher in smokers than in never-smokers. This trend is visualised in figure 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of subjects according to lung function categories and smoking history

| Subjects with normal spirometry | Subjects with PRISm | Subjects with airflow limitation | ||||

| Never-smoker | Smoker | Never-smoker | Smoker | Never-smoker | Smoker | |

| Subjects | 914 | 516 | 86 | 87 | 46 | 169 |

| Age (years) | 57.7±10.4 | 57.2±10.7 | 62.4±10.3 | 63.5±10.8 | 66.4±11.0 | 68.1±9.6 |

| Male | 358 (39.2) | 450 (87.2)* | 33 (38.4) | 76 (87.4)* | 24 (52.2) | 150 (88.8)* |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 23.1±3.8 | 24.0±3.3* | 24.2±4.6 | 24.6±3.7 | 24.1±3.2 | 23.4±3.8 |

| Smoking status, current | 0 (0) | 366 (70.9)* | 0 (0) | 57 (65.5)* | 0 (0) | 83 (49.1)* |

| Smoking duration, ≥20 pack-years | 0 (0) | 307 (59.5)* | 0 (0) | 72 (82.8)* | 0 (0) | 147 (87.0)* |

| FVC (% pred) | 97.6±11.7 | 96.8±10.8 | 74.4±8.7 | 73.6±8.4 | 92.8±17.6 | 84.8±18.7* |

| FEV1 (% pred) | 99.7±11.6 | 97.2±10.6* | 73.1±7.3 | 71.8±7.4 | 76.5±16.4 | 66.3±20.1* |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.81±0.05 | 0.79±0.05* | 0.78±0.05 | 0.77±0.05 | 0.64±0.06 | 0.60±0.09* |

| TLCCT (% pred) | 86.9±12.3 | 85.1±11.7* | 74.7±12.3 | 75.5±13.4 | 90.1±13.3 | 91.3±14.0 |

| FVC/TLCCT (%) | 70.4±10.6 | 71.3±9.7 | 61.4±10.5 | 60.3±13.1 | 61.3±11.9 | 55.7±15.0* |

| Prevalence of PSE | 23 (2.5) | 187 (36.2)# | 1 (1.2) | 38 (43.7)# | 2 (4.3) | 120 (71.0)# |

| Prevalence of CLE | 17 (1.9) | 164 (31.8)# | 4 (4.7) | 40 (46.0)# | 5 (10.9) | 134 (79.3)# |

Data are presented as n, mean±sd or n (%). PRISm: preserved ratio impaired spirometry; BMI: body mass index; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; TLCCT: total lung capacity measured by computed tomography; PSE: paraseptal emphysema; CLE: centrilobular emphysema. *: statistically significant (p<0.05) compared to never-smokers within the same lung function category; #: statistically significant (adjusted p<0.05, adjusted by Bonferroni method) compared to never-smokers within the same lung function category. The adjusted p-values comparing PRISm and other lung function categories in smokers were as follows. PSE: versus normal spirometry p=1.00, versus airflow limitation p<0.01; CLE: versus normal spirometry p=0.21, versus airflow limitation p<0.01.

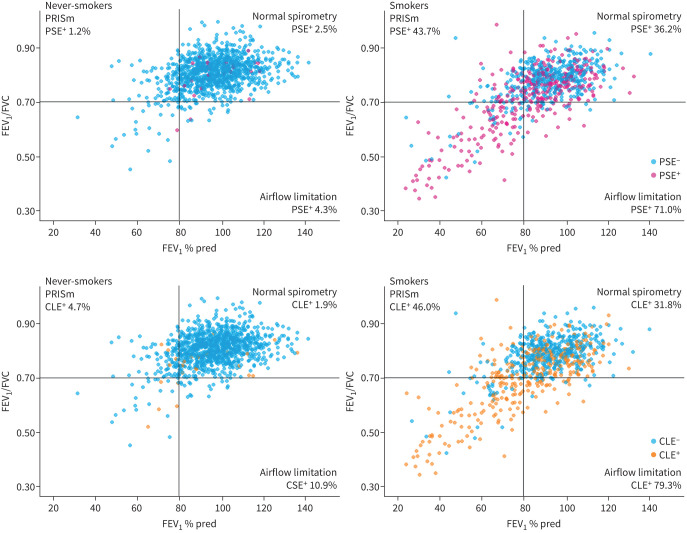

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of emphysema subtypes and lung functions in never-smokers and smokers with ≥10 pack-years undergoing computed tomography lung screening. The horizontal line represents the threshold for airflow limitation (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) 0.70), and the vertical line represents the threshold between mild and moderate airflow limitation (FEV1 80% pred). PRISm: preserved ratio impaired spirometry; PSE: paraseptal emphysema; CLE: centrilobular emphysema.

The prevalence of CLE in never-smokers with airflow limitation was higher than in never-smokers with normal spirometry (10.9% versus 1.9%, p=0.04), while the prevalence of PSE and CLE in never-smokers with PRISm did not differ from that in never-smokers with normal spirometry (PSE 1.2% versus 2.5%, p=1.00; CLE 4.7% versus 1.9%, p=1.00).

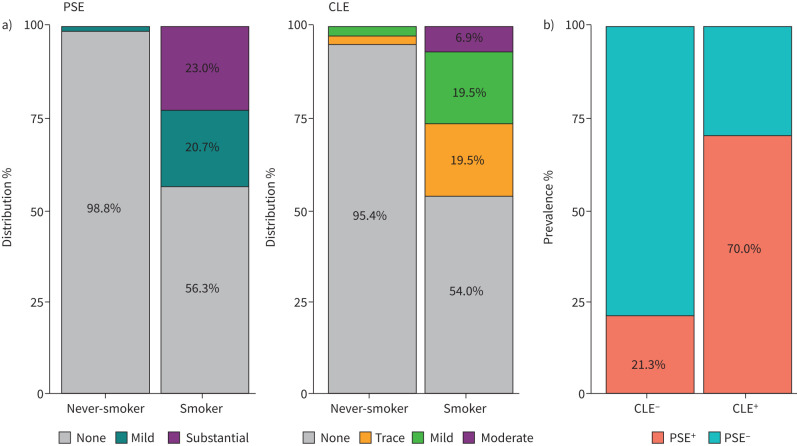

When compared within smokers, the prevalence of PSE and CLE in PRISm was comparable to normal spirometry (PRISm versus normal spirometry: PSE 43.7% versus 36.2%, p=1.00; CLE 46.0% versus 31.8%, p=0.21), but lower than those of airflow limitation (PRISm versus airflow limitation: PSE 43.7% versus 71.0%, p<0.01; CLE 46.0% versus 79.3%, p<0.01). Table 2 and figure 3a show the details of CLE and PSE categories in never-smokers and smokers with normal spirometry, PRISm and airflow limitation. Moreover, as shown in figure 3b, the presence of PSE was significantly associated with the presence of CLE in smokers with PRISm (Chi-squared p<0.01).

TABLE 2.

The distribution of emphysema subtypes in never- and ever smokers according to lung function categories

| Subjects with normal spirometry | Subjects with PRISm | Subjects with airflow limitation | |||||||

| Never-smoker | Smoker | p-value | Never-smoker | Smoker | p-value | Never-smoker | Smoker | p-value | |

| Subjects | 914 | 516 | 86 | 87 | 46 | 169 | |||

| PSE | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| None | 891 (97.5) | 329 (63.8) | 85 (98.8) | 49 (56.3) | 44 (95.7) | 49 (29.0) | |||

| Mild | 10 (1.1) | 63 (12.2) | 1 (1.2) | 18 (20.7) | 2 (4.3) | 21 (12.4) | |||

| Substantial | 13 (1.4) | 127 (24.0) | 0 (0) | 20 (23.0) | 0 (0) | 99 (58.6) | |||

| CLE | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| None | 897 (98.1) | 352 (68.2) | 82 (95.3) | 47 (54.0) | 41 (89.1) | 35 (20.7) | |||

| Trace | 16 (1.8) | 90 (17.4) | 2 (2.3) | 17 (19.5) | 3 (6.5) | 27 (16.0) | |||

| Mild | 1 (0.1) | 49 (9.5) | 2 (2.3) | 17 (19.5) | 1 (2.2) | 42 (24.9) | |||

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 17 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.9) | 1 (2.2) | 39 (23.1) | |||

| Confluent | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (8.3) | |||

| ADE | 0 (0) | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (7.1) | |||

Data are presented as n or n (%), unless otherwise stated. PRISm: preserved ratio impaired spirometry; PSE: paraseptal emphysema; CLE: centrilobular emphysema; ADE: advanced destructive emphysema.

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of emphysema subtypes in preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) according to smoking exposure. a) Emphysema subtypes distribution in PRISm; b) prevalence of coexistence of paraseptal emphysema (PSE) and centrilobular emphysema (CLE) in smokers with PRISm.

Functional impacts of PSE and CLE in smokers with PRISm

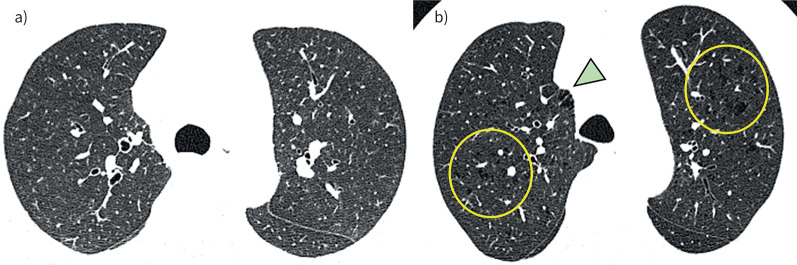

As shown in table 3, when smokers with PRISm were divided into those with and without CLE, TLCCT was higher and FVC/TLCCT was lower in the PRISm smokers with CLE than those without CLE, while FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC did not differ between the two groups. Moreover, as shown in table 4, in multivariable models, the presence of CLE, but not the presence of PSE, was associated with reduced FVC/TLCCT in smokers with PRISm independent of age, sex, body size, pack-years and smoking status. When including CLE, PSE and their interaction term in the same multivariable model, there was no significant interaction between CLE and PSE on FVC/TLCCT (p=0.85). In the model without the interaction term, the presence of CLE was associated with reduced FVC/TLCCT independent of the presence of PSE. Figure 4 shows representative CT images of two smokers with PRISm. No visual sign of emphysema was found in the first case (figure 4a) (FEV1/FVC 0.80, FEV1 73.5% pred and FVC/TLCCT 86.7%), whereas both PSE and CLE were found in the second case (figure 4b) (FEV1/FVC 0.75, FEV1 71.5% pred and FVC/TLCCT 58.9%).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of smokers with preserved ratio impaired spirometry

| CLE absent | CLE present | p-value | |

| Subjects | 47 | 40 | |

| Age (years) | 63.9±10.8 | 63.0±11.0 | 0.71 |

| Male | 40 (85.1) | 36 (90.0) | 0.72 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 25.5±3.8 | 23.5±3.3 | <0.01 |

| Smoking status, current | 29 (61.7) | 28 (70.0) | 0.56 |

| Smoking duration, ≥20 pack-years | 37 (78.7) | 35 (87.5) | 0.43 |

| FVC (% pred) | 74.3±9.0 | 72.7±7.7 | 0.39 |

| FEV1 (% pred) | 73.2±8.1 | 70.3±6.1 | 0.07 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.77±0.04 | 0.76±0.06 | 0.22 |

| TLCCT (% pred) | 72.4±12.5 | 79.2±13.6 | 0.02 |

| FVC/TLCCT (%) | 63.1±12.7 | 57.1±12.8 | 0.03 |

Data are presented as n, mean±sd or n (%), unless otherwise stated. CLE: centrilobular emphysema; BMI: body mass index; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; TLCCT: total lung capacity measured on computed tomography.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable linear regression models for forced vital capacity/total lung capacity measured on computed tomography in smokers with preserved ratio impaired spirometry

| Model: PSE | Model: CLE | Model: PSE+CLE | ||||

| Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

| PSE, presence | −2.84 (−8.24 to 2.58) | 0.30 | −0.30 (−6.07 to 5.46) | 0.92 | ||

| CLE, presence | −6.25 (−13.3 to −1.80) | 0.02 | −6.13 (−11.7 to −0.55) | 0.03 | ||

| Age, per 1-year increase | −0.72 (−1.01 to −0.42) | <0.01 | −0.76 (−1.11 to −0.38) | <0.01 | −0.76 (−1.05 to −0.47) | <0.01 |

| Male sex | −0.22 (−8.35 to 7.91) | 0.96 | 0.73 (−10.9 to 9.29) | 0.86 | 0.73 (−7.26 to 8.71) | 0.86 |

| BMI, per 1-kg·m−2 increase | −0.18 (−0.90 to 0.54) | 0.63 | −0.36 (−0.11 to 0.85) | 0.32 | −0.36 (−1.09 to 0.36) | 0.32 |

| Smoking duration, ≥20 pack-years | −0.78 (−8.44 to 6.89) | 0.84 | −0.92 (−8.54 to 7.17) | 0.80 | −0.83 (−8.32 to 6.65) | 0.83 |

| Smoking status, current | −6.41 (−12.6 to −0.26) | 0.04 | −6.28 (−16.9 to −3.13) | 0.04 | −6.22 (−12.2 to −0.22) | 0.04 |

Each model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking pack-years, smoking status and facilities. PSE: paraseptal emphysema; CLE: centrilobular emphysema.

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of smokers with preserved ratio impaired spirometry emphysema absent or present. a) 61-year-old male; neither PSE nor CLE is present; b) 66-year-old male presenting both PSE (arrowhead) and CLE (circles). Both cases had comparable lung function (forced vital capacity (FVC) 74.7% pred and 79.6% pred, for a) and b), respectively; forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) 73.5% pred and 71.5% pred, for a) and b), respectively; and FEV1/FVC 0.80 and 0.75, for a) and b), respectively), but FVC/total lung capacity measured by computed tomography was lower in case b) than case a) (86.7% and 58.9%, respectively).

Discussion

This large multicentre study showed that PRISm was found in 11.3% of smokers and 8.3% of never-smokers and that the prevalence of PSE and CLE in smokers with PRISm (44.6% and 46.7%) was higher than that in never-smokers with PRISm, comparable to smokers with normal spirometry and lower than smokers with airflow limitation. Furthermore, multivariable analysis demonstrated that the presence of CLE was independently associated with a reduction in FVC/TLCCT in smokers with PRISm. Collectively, these findings suggest that PSE and CLE are common in smokers with PRISm and the presence of CLE, but not PSE, is associated with air-trapping in smokers with PRISm.

Despite increasing recognition of PRISm, appropriate personalised management remains to be established. The difficulty is mainly due to the heterogeneous clinical manifestations of PRISm. Indeed, 25.1–32.6% of patients with PRISm develop COPD, but the rest remain in the PRISm group or even transition to the normal spirometry group over time [2, 3, 6]. A recent longitudinal study showed that increased air-trapping, expressed as a reduced FVC/TLCCT, is associated with increased disease progression in smokers with PRISm [15]. However, no report has examined the morphological changes underlying air-trapping in PRISm. Therefore, the observed association between CLE and FVC/TLCCT in smokers with PRISm substantially extends the previous finding and suggests that a visual CT finding of CLE can be a promising marker to identify high-risk individuals among smokers with PRISm. Since no established treatment is available, future studies should investigate whether bronchodilators can improve air-trapping and prevent COPD development in smokers with PRISm and CLE.

In multivariable analyses, CLE, but not PSE, was associated with FVC/TLCCT in smokers with PRISm. Pathological examinations of smokers’ lungs and COPD lungs have shown that the small airways are a major pathological site in CLE, causing airflow limitation and air-trapping [21–23], whereas the small airways are relatively preserved in PSE [24]. These pathological findings are consistent with a CT study showing that nonemphysematous gas-trapping regions, presumably induced by the small airway disease, are less severe in smokers with PSE than in those with moderate to severe CLE [25]. Therefore, CLE, but not PSE, could develop in association with small airway disease and induce air-trapping in smokers with PRISm.

This study confirmed the applicability of the Fleischner emphysema subtyping system to CT obtained at clinical practices, even outside well-established cohorts. Although quantitative measurements of emphysema have been used especially in research [26], the visual assessment complements quantitative measurements and might be more sensitive in detecting tiny parenchymal changes in smokers without airflow limitation [27].

The prevalence of PSE and CLE in smokers with PRISm did not differ from those with normal spirometry. This is not consistent with a previous report showing that PSE was more prevalent in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease unclassified patients (synonymous with PRISm) than smokers with normal spirometry, while the prevalence of CLE did not differ [7]. Furthermore, the prevalence of PSE and CLE in normal spirometry and PRISm (PSE 36.2% and 43.7%, respectively; CLE 31.8% and 46.0%, respectively) in this study was higher than those reported in the previous report (PSE 17% and 33%, respectively; CLE 22.5% and 27%, respectively). This might be because this study used the Fleischner Society classification system to detect emphysema subtype more accurately and sensitively, including trace CLE, which involved <0.5% of the lung zone [8].

CLE and PSE in never-smokers were also evaluated. Previous studies have shown that airflow limitation is not associated with emphysema on CT in never-smokers [28, 29], but very little is known about emphysema subtypes in never-smokers. Therefore, understanding of the structure–function relationship in never-smokers is expanded by the present data showing that the prevalence of CLE, but not PSE, was higher in never-smokers with airflow limitation than those with normal spirometry, while no difference was found between normal spirometry and PRISm.

This study assessed air-trapping using FVC/TLCCT. Although a previous report established this index as an air-trapping index [15], we also confirmed the validity by showing the close association between FVC/TLCCT and low attenuation volume percentage on expiratory CT using a subgroup of the present study population. It should be noted that TLCCT measured in the supine position is usually lower than TLC measured in the seated position by plethysmography, but TLCCT is well correlated with TLC measured by plethysmography [30, 31]. Therefore, FVC/TLCCT might be a reliable air-trapping surrogate index in daily practice when lung subvolumes such as residual volume and TLC or a pair of inspiratory and expiratory chest CT scans are unavailable.

The study strengths include the variety of facilities, the large sample size, the use of a simple established protocol for visual assessment of emphysema subtypes and the use of double-reading system to minimise interobserver variability. However, there are some limitations. Pulmonary function in the CT lung screening were analysed using pre-bronchodilator spirometry, because post-bronchodilator spirometry is not routinely performed in the lung cancer screening programme. Quantitative assessment of emphysema could not be conducted, because of the variety of CT scanner machines and reconstruction kernels used. There was a sex imbalance between never- and ever-smokers. The retrospective nature of the study may generate selection bias; for example, in relation to the study period of each facility and missing demographic data.

In conclusion, the prevalence of both PSE and CLE on CT in smokers with PRISm was higher than that in never-smokers with PRISm. In smokers with PRISm, the presence of CLE, but not PSE, was associated with air-trapping, suggesting different physiological roles of PSE and CLE. Visual emphysema subtyping on CT with the Fleischner Society classification system can help clinicians understand the pathophysiology of smokers and take a more personalised approach to smokers with PRISm.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00063-2022.SUPPLEMENT (161.1KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflicts of interest: N. Tanabe, S. Sato, T. Oguma and T. Hirai were supported by a grant from FUJIFILM Co., Ltd. FUJIFILM did not have a role in the design or analysis of the study or in the writing of the manuscript. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Support statement: This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science grant 19K08624. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res 2014; 15: 89. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0089-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijnant SRA, de Roos E, Kavousi M, et al. Trajectory and mortality of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901217. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan ES, Fortis S, Regan EA, et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: 1397–1405. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0663OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan ES, Balte P, Schwartz JE, et al. Association between preserved ratio impaired spirometry and clinical outcomes in US adults. JAMA 2021; 326: 2287–2298. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.20939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) . Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD . 2022. www.goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/ Date last accessed: 19 January 2022.

- 6.Wan ES, Hokanson JE, Regan EA, et al. Significant spirometric transitions and preserved ratio impaired spirometry among ever smokers. Chest 2022; 161: 651–661. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SS, Yagihashi K, Stinson D, et al. Visual assessment of CT findings in smokers with nonobstructed spirometric abnormalities in the COPDGene® study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2014; 1: 88–96. 10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2013.0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch DA, Austin JHM, Hogg JC, et al. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2015; 277: 192–205. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh AS, Strand M, Pratte K, et al. Visual emphysema at chest CT in GOLD stage 0 cigarette smokers predicts disease progression: results from the COPDGene study. Radiology 2020; 296: 641–649. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Kaddouri B, Strand MJ, Baraghoshi D, et al. Fleischner Society visual emphysema CT patterns help predict progression of emphysema in current and former smokers: results from the COPDGene study. Radiology 2020; 298: 441–449. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch DA, Moore CM, Wilson C, et al. CT-based visual classification of emphysema: association with mortality in the COPDGene study. Radiology 2018; 288: 859–866. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith BM, Austin JHM, Newell JD, et al. Pulmonary emphysema subtypes on computed tomography: the MESA COPD study. Am J Med 2014; 127: 94.e7–94.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng S, Tham A, Bos B, et al. Lung volume indices predict morbidity in smokers with preserved spirometry. Thorax 2019; 74: 114–124. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortis S, Comellas AP, Bhatt SP, et al. Ratio of FEV1/slow vital capacity of <0.7 is associated with clinical, functional, and radiologic features of obstructive lung disease in smokers with preserved lung function. Chest 2021; 160: 94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortis S, Comellas A, Kim V, et al. Low FVC/TLC in preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) is associated with features of and progression to obstructive lung disease. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 5169. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61932-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota M, Kobayashi H, Quanjer PH, et al. Reference values for spirometry, including vital capacity, in Japanese adults calculated with the LMS method and compared with previous values. Respir Investig 2014; 52: 242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, et al. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 1993; 6: Suppl. 16, 5–40. doi: 10.1183/09041950.005s1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hersh CP, Washko GR, Estépar RSJ, et al. Paired inspiratory-expiratory chest CT scans to assess for small airways disease in COPD. Respir Res 2013; 14: 42. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanabe N, Shimizu K, Terada K, et al. Central airway and peripheral lung structures in airway disease-dominant COPD. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00672–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00672-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim WD, Eidelman DH, Izquierdo JL, et al. Centrilobular and panlobular emphysema in smokers: two distinct morphologic and functional entities. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 144: 1385–1390. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.6.1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo HK, Vasilescu DM, Booth S, et al. Small airways disease in mild and moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 591–602. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30196-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanabe N, Vasilescu DM, Hague CJ, et al. Pathological comparisons of paraseptal and centrilobular emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 803–811. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201912-2327OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park J, Hobbs BD, Crapo JD, et al. Subtyping COPD by using visual and quantitative CT imaging features. Chest 2020; 157: 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatt SP, Washko GR, Hoffman EA, et al. Imaging advances in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Insights from the genetic epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPDGene) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 286–301. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1351SO [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regan EA, Lynch DA, Curran-Everett D, et al. Clinical and radiologic disease in smokers with normal spirometry. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 1539–1549. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan WC, Sin DD, Bourbeau J, et al. Characteristics of COPD in never-smokers and ever-smokers in the general population: results from the CanCOLD study. Thorax 2015; 70: 822–829. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H, Hong Y, Lim MN, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and radiologic measurements in never-smokers with COPD: a cross-sectional study from the CODA cohort. Chron Respir Dis 2018; 15: 138–145. doi: 10.1177/1479972317736293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Donnell CR, Bankier AA, Stiebellehner L, et al. Comparison of plethysmographic and helium dilution lung volumes: which is best for COPD? Chest 2010; 137: 1108–1115. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwano S, Okada T, Satake H, et al. 3D-CT volumetry of the lung using multidetector row CT. Comparison with pulmonary function tests. Acad Radiol 2009; 16: 250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00063-2022.SUPPLEMENT (161.1KB, pdf)