Abstract

Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease describes the backflow of acidic stomach content towards the larynx and is associated with symptoms such as cough, throat clearing and globus. It is a common presentation in primary care and the sequelae of symptoms that arise from the disease often present in ear, nose and throat clinics. Assessment and examination of patients presenting with reflux symptoms includes questionnaires, as well as direct visualisation of the pharynx and larynx, and takes a multidisciplinary team approach. Treatment options include lifestyle modification, medical therapy and in some specialist centres, surgical management to address the multitude of symptoms associated with the disease.

Keywords: GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE, OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX

Key points.

Common ear, nose and throat (ENT)-related laryngopharyngeal symptoms include cough, persistent sore throat, hoarseness, globus and repetitive throat clearing.

Multiple assessment tools can be used to assess the severity and impact of laryngopharyngeal reflux: Reflux Symptom Index, Reflux Finding Score, Voice Handicap Index and Complex Reflux Symptom Score.

Thorough examination using flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy±oesophagoscopy is useful in confirming the diagnosis although there is no gold-standard investigation.

ENT complications of reflux include upper oesophageal strictures, laryngeal granulomas and glottic and subglottic stenoses and strictures.

The mainstay of management includes lifestyle advice and medical therapy. Surgical management of reflux-related sequelae are available; in specialist centres, some procedures can be performed under local anaesthetic.

Multidisciplinary teams consisting of otolaryngologists working alongside general practitioners, speech and language therapists and gastroenterologists are imperative for effective management.

Introduction

Persistent throat symptoms comprising cough, discomfort, hoarseness, sensation of a lump (globus), repetitive throat clearing, rhinorrhoea and postnasal drip, are among the most common presentations to primary and secondary care clinics.1 In middle-aged women, globus alone has an estimated prevalence of 6% and in the UK, throat symptoms account for at least 5% of referrals to ear, nose and throat (ENT) departments.2

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD UK English, GERD US English)3 has an approximate prevalence of 20% in the Western world.4 GORD is defined as the backflow of stomach content towards the oesophagus with resultant inflammation and erosion. Symptoms include acid regurgitation and heartburn, as well as extraoesophageal symptoms such as cough, laryngitis, dental erosion and asthma.5 Similarly, the backflow of acidic stomach content into the larynx and pharynx is known as laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPR). The association between reflux disease and throat symptoms is well recognised (if poorly characterised) and one UK survey showed that over 50% of British otolaryngologists use proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in its management.6 This does not accord with a recently published randomised controlled trial (RCT) looking into effectiveness of PPIs for throat symptoms. The study concluded that there was no difference between the two groups after treatment with placebo versus lansoprazole. Patient selection was based on the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI), a debateable, but widely used, diagnostic tool for LPR (patients with no reflux symptoms can score high on the RSI).7 Moreover, traditional methods for diagnosing GORD do not reliably diagnose LPR. Since there is no reliable diagnostic tool for LPR, empirical reflux treatment is likely to continue until a valid and reliable means of diagnosing LPR emerges.2 Meanwhile, national guidance has been issued recommending that PPIs be avoided in suspected LPR, unless there is clear evidence of concurrent GORD or other compelling evidence, such as positive oesophageal physiology tests/oesophagogastroscopy. It must be noted that the commonly associated throat symptoms of LPR may also be attributed to other irritable insults, including alcohol consumption, smoking and aeroallergens, to name but a few. Laryngeal hypersensitivity syndrome (LHS) is a more recently recognised diagnosis that may be caused by LPR. Further discussion around LHS is out of the remit of this review, but it is the authors’ opinion that this area will be one of great research interest in the future.

Sequelae of reflux

The most commonly recognised symptoms associated with LPR include chronic cough, globus, throat pain, excessive throat clearing, voice fatigue and dysphagia. In some cases, the sequelae of chronic inflammation due to reflux into the larynx can result in significant dysphonia. The main sequelae that arise from LPR are hypothesised to be secondary to chronic inflammation caused by refluxing of gastric contents.8

‘Red flag’ symptoms (such as persistent pain or hoarseness) that would channel patients into the fast-track ‘2-week wait’ pathway in the UK for suspected head and neck malignancy overlap with those of LPR, a far commoner problem.8 Thus, the condition may be identified fairly quickly in many people as a product of this process.

Granulomas

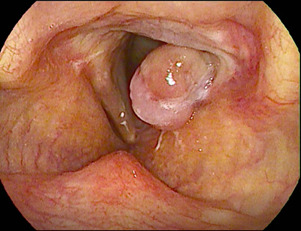

Complications may include granulomas, most commonly at the posterior end of one vocal cord, as well as much less commonly in the supraglottis and subglottis. When present on the vocal cords, granulomas can cause abnormal or poor adduction of the cords resulting in a rough voice quality, voice fatigue and difficulty in projecting.8 In rare, extreme, cases, airway obstruction can occur (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left vocal cord granuloma.

Laryngeal scarring, strictures and sulci

Chronic refluxing of gastric contents is thought to play a part in scarring of the glottis and sub-glottis. This can subtly affect the mobility of the vocal cords causing dysphonia.8

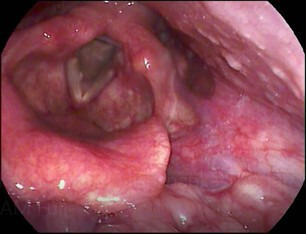

Polyps and cysts

Vocal cord inflammatory polyps and cysts are common abnormalities with some levels 3 and 4 evidence of association with reflux. Contralateral damage to the other cord from contact can occur, with ‘kissing lesions’ and possibly haemorrhage on either side. It is further believed that cysts can burst, leaving subsequent scarring and sulci (axial grooves) of the cords9 (see figure 2). Other causes of sulci are also hypothesised, such as congenital and traumatic.

Figure 2.

Right anterior vocal cord polyp.

Chronic cough

Irritation of the larynx may lead to a persistent dry cough and hypersensitivity.8 Hypersensitivity is characterised by a decreased cough and throat symptom threshold to various noxious and non-noxious stimuli for example, cold drinks, cold air, aerosols.10 A small study has shown that in patients with chronic cough and LPR who have not previously been treated, the expected improvement after initiating reflux treatment is 60% at 3 months. In 10% of patients, complete resolution of cough was reported by 4 months.10

Laryngitis

A persistent feeling of sore throat without evidence of an acute viral, fungal or bacterial infection is a common complication of LPR.8 The pain can result from a combination of active inflammation and reactive muscle tension (internal and external), and both require attention. It is worth considering muscle tension dysphonia (anxiety related) and candida as differentials.

Upper oesophageal strictures, webs and spasms

Oesophageal narrowing can occur, producing classical symptoms of choking, sticking, tightening, spasm or regurgitation when swallowing.8 There is various terminology used to describe oesophageal narrowing, including oesophageal webs, bars and strictures. It most commonly affects the cricopharyngeal area at the upper oesophagus where the cricopharyngeus muscle can spasm and hypertrophy in the presence of chronic inflammation.8 Such problems are often associated with synchronous uncontrolled GORD which requires MDT management with gastroenterology.

Sinusitis

The relationship between reflux and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is controversial. A few research papers have found that pepsin A levels have a higher expression in the nasal mucosa of patients with CRS, suggesting a correlation between LPR and CRS.11

Chronic otitis media with effusion

Some of the literature shows that the prevalence of otitis media is higher in patients with LPR than those without.12 One study demonstrated that Eustachian tube dysfunction was more likely to be associated with low nasopharyngeal pH and a higher Reflux Finding Score (RFS). The pathogenesis is not well understood but the association between LPR and otitis media may be due inflammation of the mucosal lining of the eustachian tube and middle ear, leading to oedema and obstruction of the outflow and drainage of middle ear mucus. Since there is no barrier stopping the influx of naso/oro or laryngopharynx secretions into the eustachian tubes, anatomically this may explain the spread of acid in the laryngopharynx and eustachian tube resulting into inflammation in the middle ear (otitis media).13

Risk factors

The following risk factors are associated with an increased risk of LPR: alcohol consumption, tobacco use, dietary salt content, spicy food, chocolate and caffeine intake, going to sleep within 2 hours of food consumption, obesity and stress5 (see table 1). Studies have also demonstrated a link with structural abnormalities, such as laryngeal or oesophageal spasm and stenosis.14 Associations of LPR with comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, chronic lung disease and irritable bowel syndrome all have some research support.4 14 LPR may alter the upper aerodigestive tract flora and there are reports of association with altered bowel flora also (eg, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth).15 There is tentative data supporting a genetic predisposition to GORD.4

Table 1.

Risk factors for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease

| Risk factor category | |

| Food and drink | Alcohol, salt, chocolate, caffeine, spicy food, carbonated drinks, high fat foods. |

| Lifestyle | Tobacco use, stress, sleeping close to eating. |

| Medical comorbidities | Obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic lung disease, irritable bowel syndrome. |

| Structural | Oesophageal spasm and stenosis. |

Assessment tools

A comprehensive history is paramount to assess for a patient’s oesophageal symptoms, including heartburn and reflux. In addition, the RSI,7 RFS,16 Voice Handicap Index (VHI),17 (or shortened version VHI-10), and Complex Reflux Symptom Score (CReSS)1 can be used as part of the assessment to quantify a patient’s physical symptoms and severity of LPR. These scoring questionnaires are useful screening tools, helpful in establishing the nature of a patient’s reflux symptoms, as well as the self-perceived impact of their symptoms on their quality of life. They have all been used in trials to investigate the use of PPIs to treat persistent throat symptoms.1

Reflux symptoms index

The RSI (table 2), designed in 2002 by Belafsky et al, 14 comprises a nine-item self-reported questionnaire whereby a patient is asked to rate (0, no impact to 5, severe impact) LPR-associated symptoms and how they have impacted their lives over the preceding month. The maximum score is 45; a score of greater than 13 is considered a reliable diagnostic indicator for LPR and these patients often proceed to laryngoscopic examination to further quantify their LPR using the RFS.13

Table 2.

Reflux Symptoms Index

| Reflux Symptom Index | 0=no problem 5=severe problem |

| 1. Hoarseness or a problem with your voice | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. Clearing your throat | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. Excess throat mucous or postnasal drip | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. Difficulty swallowing food, liquids or pills | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5. Coughing after you ate or lying down | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 6. Breathing difficulties or choking episodes | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 7. Troublesome or annoying cough | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 8. Sensations of something sticking in your throat or a lump in your throat | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 9. Heartburn, chest pain, indigestion or stomach acid coming up | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Total |

Reflux Finding Score

The RFS comprises an eight-item index, designed to score patients based on endoscopic findings;scores range from 0 to 26, with a score of 11 or more generally considered to be diagnostic for LPR.14 (table 3)14

Table 3.

Reflux Finding Score

| Findings | Score |

| Subglottic oedema | 0=absent 2=present |

| Ventricular obliteration | 2=partial 4=complete |

| Erythema/hyperaemia | 2=arytenoids only 4=diffuse |

| Vocal fold oedema | 1=mild 2=moderate 3=severe 4=polypoid |

| Diffuse laryngeal oedema | 1=mild 2=moderate 3=severe 4=obstructing |

| Posterior commissure hypertrophy | 1=mild 2=moderate 3=severe 4=obstructing |

| Granuloma/granulation of tissue | 0=absent 2=present |

| Thick endolaryngeal mucous | 0=absent 2=present |

Comprehensive Reflux Symptom Score

The CReSS comprises a 34 reflux symptom score, combing elements of the RSI and the Gastro-Oesophageal Symptom Assessment Scale.1

Voice Handicap Index

The VHI is a subjective scoring system that evaluates the psychosocial impact of voice disorders on a patient’s quality of life. The shorter more commonly used 10-item index questionnaire, VHI-10 (a truncated version of the thirty-item VHI) is scored between 0 and 40 with a higher score indicating a more significant voice-related handicap (table 4).15

Table 4.

Voice Handicap Index (VHI)

| VHI-10 statement | Score |

| 1. My voice makes it difficult for people to hear me | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 2. I run out of air when I talk | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 3. People have difficulty understanding me in a noisy room | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 4. The sound of my voice varies throughout the day | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 5. My family has difficulty hearing me when I call them throughout the house | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 6. I use the phone less often than I would like to | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 7. I’m tense when talking to others because of my voice | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 7. I’m tense when talking to others because of my voice | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 8. I tend to avoid groups of people because of my voice | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 9. People seem irritated with my voice | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| 10. People ask ‘What’s wrong with your voice?’ | 0 1 2 3 4 |

0=never 1=almost never (occasionally) 2=sometimes 3=almost always 4=always.

Examination

Examination for LPR begins with a general assessment of the patient’s voice and objective voice assessment for example, the GRBAS score18 (grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia, strain). Each parameter is graded from 0 to 3 based on severity.16 Objective observation signs, such as, cough or throat clearing can be an indicator of reflux.

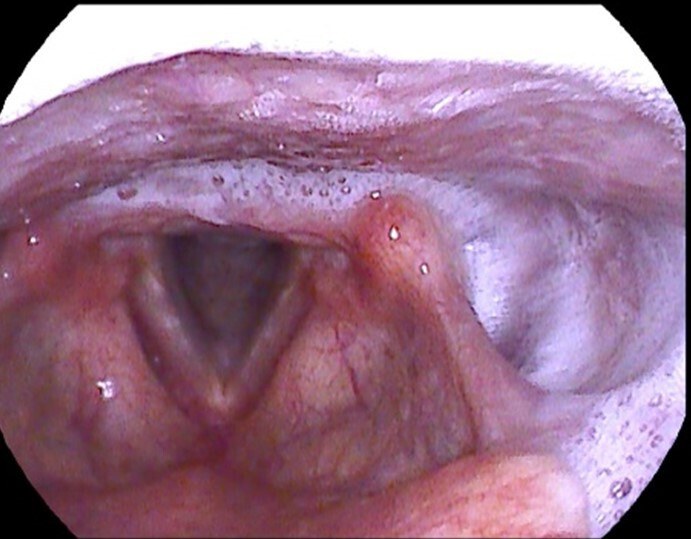

Flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy is then performed to directly view the pharynx and larynx. Common findings include a dry pharyngeal mucosal lining with thick secretions or mucous and a cobblestone appearance of the mucosa. The vocal cords, arytenoid cartilages and supraglottic structures often appear oedematous and erythematous with a typical inflamed appearance. Specifically focusing on the posterior glottis, patients can display thickening and oedema particularly in the interarytenoid region (see figures 3 and 4). This oedema can extend into the sub-glottis causing narrowing. Granulomas can present in the glottic, subglottic or supraglottic region. Depending on the size and position of a vocal cord granuloma, the cords may have restricted movement and adduction may be impaired.8 Compensation and tension of the supraglottis and laryngeal muscles can also result.19

Figure 3.

Signs of LPR: inflammation, erythema, arytenoid oedema, cobbled stone appearance of posterior pharyngeal wall. LPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux disease.

Figure 4.

Posterior glottic secretions (refluxate) causing posterior glottic oedema.

Access to videostroboscopy is not universal in ENT clinics, but in specialist voice centres it is often used to assess the vocal cords more closely and can produce high-definition images and assessment of the mucosal waves of the vocal cords. This allows for identification of smaller or more subtle changes in the larynx. It also gives the clinician more information on functional voice in real time, examining abduction and adduction of the cords and coordination of the larynx as a whole, while the patient phonates. Images and videos can be recorded and shown to the patient to inform them on the disease process and used for comparison in future consultations.20

Evaluation of the postcricoid area and upper oesophagus can be performed with a high-quality digital flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscope. Signs may include erythema, oedema and frothy gastric fluid contents at the upper oesophageal opening. Flexible transnasaloesophagoscopy (TNO: performed without sedation in the ENT clinic or combined with other procedures in theatre) is rapidly spreading and highly valuable procedure in ENT clinics.21 This uses a longer and wider diameter scope with a channel for insufflation, suction and instrumentation. With topical local anaesthetic, it is passed into the oesophagus down to the stomach, where retroflexion can be used to identify hiatus hernia. Common findings in reflux disease include oesophagitis, ulceration, strictures, webs or narrowing (Shatzki’s ring).21 Signs of eosinophilic oesophagitis (oesophageal asthma, causing dysphagia) can coexist with classical reflux (oedema, stricture, presence of rings known as trachealisation).21 Careful examination looking for gastric inlet patches, particularly in the proximal oesophagus is also key.22 It is important that ENT surgeons performing TNO have a close working relationship with their local gastroenterology department for support with diagnoses and joint management.

Investigations

Investigations for patients with LPR are usually limited to physical examination and flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy. However, there is a role for further investigation in chronic or severe cases or in patients with additional symptoms. Persistent dysphagia in people with other risk factors for cancer, for example age over 40, smokers, family history of cancer, warrants urgent referral for endoscopic examination of the upper digestive tract on a 2-week wait pathway.

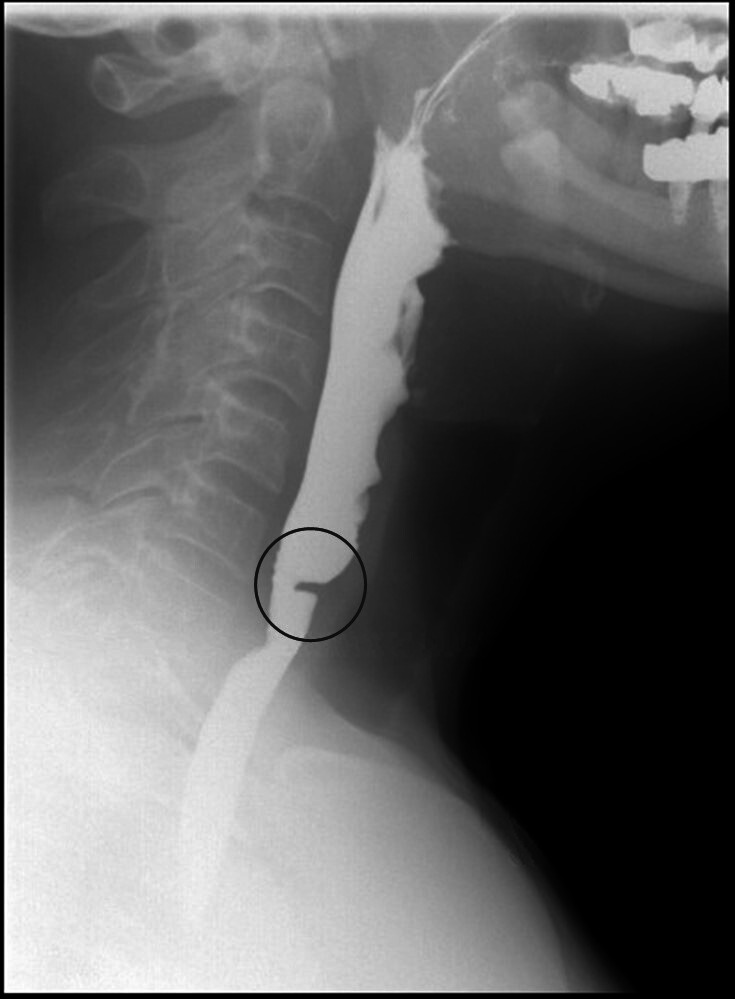

In patients who have dysphagia, particularly upper oesophageal symptoms such as food ‘sticking’, choking sensations, regurgitation or tightness, and an oesophogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) has ruled out cancer, a barium swallow or video-fluoroscopy (more detailed study of oral and pharyngeal phases of swallow) can be helpful.23 It is important to note that subtle strictures or webs can have a seemingly disproportionate impact on symptoms (see figure 5) and if these are suspected, direct inspection with oesophagoscopy is required.

Figure 5.

Barium swallow demonstrating oesophageal web.

In refractory, chronic or severe cases, referral to gastroenterology for pH, high resolution impedence-manometry, Helicobater pylori testing and OGD is indicated.8

Management

Lifestyle advice

Patient education is vital for patients to make informed lifestyle choices and modifications. Avoiding common triggers such as caffeine, carbonated drinks, alcohol, spicy or high fat foods can alone be transformative.19 Triggers are patient specific and recommending symptom and dietary diaries can be useful in making links with triggers and symptoms. Smoking cessation or reduction is imperative and sources of assistance should be accessed where required.24 Adequate hydration, stress reduction and weight loss are also advised.25 Patient information leaflets can be a helpful adjunct in clinic as an aide memoire for patients to take home.

Medical management

The mainstay of medical therapy is with alginate-based medicines, such as Gaviscon Advance if throat symptoms alone, or with the addition of PPIs if related to GORD.25 The majority of patients referred to ENT clinics in secondary care for LPR will be experiencing moderate to severe ENT-related symptoms and/or have sequelae of the disease. ENT specialists meet patients at various points along their disease process with huge variation in previous management. For moderate to severe cases, the literature, up until recently, has advocated for a trial of PPI (Lansoprazole 30 mg two times per day, taken 30 min before meals) for 3 months, followed by review.8 However, O’Hara et al have questioned such liberal use of PPI’s without robust trial support.1 In addition, sodium alginate with potassium bicarbonate (Gaviscon Advance or equivalent, 10mls, 20 min after meals and before bedtime) can be trialled.25 Regular review is vital in order for doses to be reduced or PPIs stopped if there is no improvement. Refractory cases may need referral to gastroenterology for further investigation and potentially upper gastrointestinal (GI) intervention to help treat the reflux reaching the laryngopharynx.

In response, Watson et al completed a double blinded RCT (TOPPITS trial)1 2 looking into the effectiveness of PPIs for the treatment of throat symptoms and suspected LPR. Its comparison of Lansoprazole versus placebo did not show any significant difference in outcome and therefore has called into question conventional wisdom on how to manage these patients. Some criticisms of the trial have been raised, however. First, there was no gold standard investigation for LPR (24 hours pH impedance monitoring) and the scoring systems used such as the RSI and RFS (see above) are not specific for LPR alone.26 In addition, not all throat symptoms are caused by acid reflux. A patient without LPR may have a significant score and/or throat symptoms due to a variety of other pathologies and consequently included in the study. Furthermore, selection for the trial included patients with an RSI above 10, whereas ‘abnormal’ was set by the score developers as greater than 13.7 This may have skewed the results negatively towards the benefits of PPIs for those with a true diagnosis. It is therefore important to establish the diagnosis of reflux with more certainty if treatment is to be effective and we should be cautious to completely dismiss the use of PPIs for patients, some of whom may benefit. National guidance based on the trial results (and similar precedents) is likely to reduce PPI prescription for uncomplicated LPR dramatically.

Surgical management

Some patients with persistent reflux that fails drug therapy, may be referred for evaluation of surgical management, for example, patients with diagnosed hiatus hernia may benefit from fundoplication. Antireflux surgery (including various forms of fundoplication and devices such as EsophyX and LINX) for GORD presents alternatives and adjuncts to long-term antireflux medication, for those with refractory symptoms.27 There are stringent criteria for such surgery, outside the scope of this paper. Endoscopic techniques, such as EsophyX, may be performed by interventional upper GI physicians and are minimally invasive. However, laparoscopic surgery under upper GI surgeons (fundoplication, LINX and others) are thought to have better long-term effectiveness.6 27 These would be used following proof of classic GORD through both OGD and 24 hours pH-impedance testing, but their place in assisting extraoesophageal symptoms alone, as with PPIs, is presently controversial. More trials are required.

There are, however, multiple procedures that can be performed to treat the sequelae and complications of chronic reflux.

Oesophageal strictures

Balloon dilation is the mainstay of surgical management for oesophageal strictures, webs and narrowing resulting in dysphagia. This can be carried out under general anaesthetic with rigid pharyngoscopy and oesophagoscopy followed by balloon dilatation and can also be carried out by GI physicians under local anaesthetic with or without sedation. However, delivering the balloons via TNO or flexible gastroscopes provides better views and control with less risk than with rigid oesophagoscopes and is increasingly replacing the latter.21 For small strictures, occasionally passing a rigid oesophagoscope through the upper oesophagus is sufficient in stretching the narrowed area. In specialist tertiary centres this can be performed trans-nasally with topical local anaesthetic in clinic. A flexible oesophagoscope/TNO is passed into the oesophagus down to the stomach with gentle insufflation. The scope is then withdrawn to the area of maximal narrowing (usually the cricopharyngeal area). A guidewire is passed down a port on the scope and a balloon passed over the guidewire using a Seldinger technique. The balloon is inflated for 60–120 s usually to a range of 12–20 mm, depending on the size of the patient and tightness of stricture/spasm. The procedure is generally well tolerated and avoids the need for general anaesthetic or sedation.28

Laryngeal granulomas

Inflammatory granulomas or lesions are conservatively managed if they do not obstruct the airway. Maximal antireflux therapy is advised and speech and language therapy (SLT) is required to reduce secondary muscle tension. For refractory and symptomatic granulomata, botulinum toxin is sometimes injected into the thyroarytenoid-lateral cricoarytenoid complex to avoid forceful adduction (and thus traumatic granuloma generation) of the vocal process.29 If these methods fail, in-office laser (eg, Trublue, KTP) is possible. Otherwise, excision using microlaryngoscopy under general anaesthetic, using microlaryngeal instruments and/or laser may be used. Specimens are sent for histological analysis to confirm the diagnosis. Care needs to be taken to preserve the vibrating mucosal surfaces and superficial lamina propria of the vocal cords. Voice therapy postoperatively is a useful adjunct to improve voice quality and promotion of abduction of the vocal cords.29

Glottic webs, scarring and subglottic stenosis

Chronic reflux has been associated with glottic scarring, particularly in the posterior glottis and interarytenoid area. Similarly, in severe cases, subglottic stenosis can occur. In these cases, a variety of techniques can be used under general anaesthetic with microlaryngoscopy. Cold steel, CO2 laser, corticosteroid injections and balloon dilatation can all be used in conjunction. Consideration must be made to avoid the creation of new scar tissue and a balance must be struck when improving the airway versus improving voice. Occasionally splints may be used to prevent scarring of the glottis post-operatively and allow for healing.28

Multidisciplinary team

There can be uncertainties and complexity in managing patients with suspected LPR, particularly when the diagnosis is not obvious. Working as part of a multidisciplinary team is crucial to ensure the correct investigations and management is carried out. For ENT specialists, working alongside SLT is imperative. Patients particularly struggling with voice symptoms or dysphagia may be referred for therapy and SLT therapists are trained in advising patients appropriately and providing support with promotion of abduction of vocal cord exercises, prevention of harsh glottic attacks, suppression of cough and throat clearing by sniffing and promotion of deep swallows with sips of water. For those with hypersensitivity in the absence of objective reflux, this is particularly helpful.

Conclusion

LPR is a common, if enigmatic, diagnosis in ENT clinics, either due to associated ENT-related symptoms or its complications. The mainstay of management includes patient education on lifestyle modification together with medical therapy with alginate-based medicines, with or without PPIs in patients with concurrent GORD or refractory symptoms. Planned review of medical therapy to assess effectiveness and severity of symptoms is important in order to assess the need for secondary care intervention and further investigation. For refractory and complex cases, an MDT approach is necessary with referral and further investigation by gastroenterology, GI physiologists and imaging. The role of endoscopic or laparoscopic antireflux procedures for extraoesophageal reflux symptoms is unclear and needs more trials. For both laryngeal and upper oesophageal complications, there are ENT procedures that can be effective. Procedures such as TNO and in-office laser/injection, can now be carried out under local anaesthetic in clinic, techniques available at an increasing number of ENT centres nationally and internationally.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB and CW wrote the article with contributions and edits from NW, MB and YK.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1. O'Hara J, Stocken DD, Watson GC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2021;372:m4903. 10.1136/bmj.m4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watson G, O'Hara J, Carding P, et al. TOPPITS: trial of proton pump inhibitors in throat symptoms. study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:175. 10.1186/s13063-016-1267-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon consensus. Gut 2018;67:1351–62. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dent J, et al. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2005;54:710–7. 10.1136/gut.2004.051821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zuckerman MJ, Carrion AF. Gastro-Oesophageal reflux disease, 2022. BMJ Best Practice. Available: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/82 [Accessed 23 Feb 2022].

- 6. Karkos PD, Benton J, Leong SC, et al. Trends in laryngopharyngeal reflux: a British ENT survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264:513–7. 10.1007/s00405-006-0222-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Massawe WA, Nkya A, Abraham ZS, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease, prevalence and clinical characteristics in ENT department of a tertiary hospital Tanzania. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;7:28–33. 10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Postma GN, Halum SL. Laryngeal and pharyngeal complications of gastroesophageal reflux. GI Motility 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saran M, Georgakopoulos B, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Larynx Vocal Cords. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535342/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeakel H, Balouch B, Vontela S, et al. The relationship between chronic cough and laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Voice 2020;7. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ren J-jun, Zhao Y, Wang J, et al. PepsinA as a marker of laryngopharyngeal reflux detected in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;156:893–900. 10.1177/0194599817697055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karyanta M, Satrowiyoto S, Wulandari DP. Prevalence ratio of otitis media with effusion in laryngopharyngeal reflux. Int J Otolaryngol 2019;2019:1–3. 10.1155/2019/7460891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brunworth JD, Mahboubi H, Garg R, et al. Nasopharyngeal acid reflux and Eustachian tube dysfunction in adults. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2014;123:415–9. 10.1177/0003489414526689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice 2002;16:274–7. 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riordan SM, McIver CJ, Wakefield D, et al. Small intestinal mucosal immunity and morphometry in luminal overgrowth of indigenous gut flora. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:494–500. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope 2001;111:1313–7. 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, et al. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. Laryngoscope 2004;114:1549–56. 10.1097/00005537-200409000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Webb AL, Carding PN, Deary IJ, et al. The reliability of three perceptual evaluation scales for dysphonia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2004;261:429–34. 10.1007/s00405-003-0707-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGarey PO, Barone NA, Freeman M, et al. Comorbid dysphagia and dyspnea in muscle tension dysphonia: a global laryngeal musculoskeletal problem. OTO Open 2018;2:2473974X1879567. 10.1177/2473974X18795671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Casiano RR, Zaveri V, Lundy DS. Efficacy of videostroboscopy in the diagnosis of voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:95–100. 10.1177/019459989210700115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanyaolu LN, Jemah A, Stew B, et al. The role of transnasal oesophagoscopy in the management of globus pharyngeus and non-progressive dysphagia. Annals 2016;98:49–52. 10.1308/rcsann.2015.0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rusu R, Ishaq S, Wong T, et al. Cervical inlet patch: new insights into diagnosis and endoscopic therapy. Frontline Gastroenterol 2018;9:214–20. 10.1136/flgastro-2017-100855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Furlow B. Barium swallow. Radiol Technol 2004;76:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuo C-L. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: an update. AOHNS 2019;3. 10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2019.00094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martinucci I, de Bortoli N, Savarino E, et al. Optimal treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2013;4:287–301. 10.1177/2040622313503485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watson NA, Kwame I, Oakeshott P, et al. Comparing the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux between the reflux symptom index, clinical consultation and reflux finding score in a group of patients presenting to an ENT clinic with an interest in voice disorders: a pilot study in thirty-five patie. Clin Otolaryngol 2013;38:329–33. 10.1111/coa.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Narsule CK, Wee JO, Fernando HC. Endoscopic management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:S74–9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sokol H, Adolph TE, Sami SS. The microbiota: an underestimated actor in radiation-induced lesions? Gut 2018;67:1–24. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pham Q, Campbell R, Mattioni J, et al. Botulinum toxin injections into the lateral cricoarytenoid muscles for vocal process granuloma. J Voice 2018;32:363–6. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]