Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an idiopathic long-term relapsing and remitting disorder including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The aim of therapy is to induce and maintain remission. Anti-TNF therapies dramatically improved clinical outcomes but primary failure or secondary loss is a common problem as well as potential side effects potentially limiting efficacy and long-term use. The advent of new targeted agents with the potential for greater safety is welcomed in IBD and offers the potential for different agents as the disease becomes refractory or even combination therapies to maximise effectiveness without compromising safety in the future. More data are required to understand the best positioning in pathways and longer-term safety effects.

Keywords: IBD, CROHN'S DISEASE, ULCERATIVE COLITIS

Introduction

In the past decade, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has emerged as a public health challenge worldwide with westernised nations having a growing incidence and prevalence of both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). In North America and Europe, over 1.5 million and 2 million people suffer from the disease, respectively.1 Both are chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorders of the entire gastrointestinal tract. They usually have a relapsing-remitting course that require lifelong treatment to maintain remission.2

For many years, IBD has been managed with corticosteroids, aminosalicylates and immunosuppressants (ie, thiopurines). The advent of biological therapies (anti-TNF-α agents), which is the current practice, has significantly improved the outcome of patients with IBD in terms of prolonged clinical remission, corticosteroid sparing, achievement of mucosal healing and prevention of disease-related complications. However, primary failure or loss of response to biologics occur in about 50% of patients treated with these drugs. Additionally, recent advances in the management of IBD have led to a paradigm shift in the treatment goals, from targeting symptom-free daily life to shooting for mucosal healing, which eventually calls for new therapeutic strategies. Also, their safety profile, especially the increased risk of infections and cancer has always been a concern for these patients, especially during the COVID-19 era, when our patients are more concerned for immunosuppression than ever.3

Cost-effectiveness had been also important, with a constant effort to decrease the cost and improve the availability of the existing agents. Biosimilars have luckily been proven to show the same efficacy with significantly lower cost.4

The need for intravenous administration in a hospital setting is rather costly for our Health Systems and can become stressful for our patients, especially those shielding during the COVID-19 period or with mobility issues or those with a busy schedule that would not prefer to commit to a scheduled frequent hospital appointment, like students or overseas.3

Easily administered orally or subcutaneous (SC) agents that can be provided from a Homecare Company had become an option and there is an increasing demand for more of these drugs to emerge. This can in turn increase compliance and improve efficacy.

Furthermore, increased understanding of the immunopathology of IBD has led to the development of targeted therapies and has unlocked a new age in IBD management and a hope for customised treatments.2 Ultimately, the need for new effective treatments for such patients has critically emerged as an urgent priority, especially during the COVID-19 period.5

IBD likely results from microbial dysbiosis, genetic and environmental factors that disturb the gut homoeostasis, leading to immune cell activation. CD has an exaggerated predominantly T helper (Th) 1 cell response with high interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-12 and UC mainly Th2 response dominated by the production of IL-5 and IL-13, resulting in tissue damage.6 7

Novel agents target innate and adaptive immune pathways. Adaptive immunity through differentiation of naïve CD4 +cells to effector Th1, Th2, Th17 cells causes chronic inflammation. Diverse therapeutic options are emerging, involving small molecules, apheresis therapy, improved intestinal microecology, cell therapy and exosome therapy. In addition, patient education partly upgrades the efficacy of IBD treatment.8

In this review, the latest progress in IBD treatment is summarised to understand the advantages, pitfalls and research prospects of different drugs and therapies and to provide a basis for the clinical decision and further research of IBD. Several studies with novel drugs have shown promise in IBD including innate cell microbial sensing and toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) modulation, Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT pathway inhibition, selective lymphocyte trafficking inhibitors, anti-integrin therapy, IL-12/23 inhibitors, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1R) selective agonist, miR-124 expression inhibitor, IL-10 inhibitor and PDE-4 inhibitors.7–9

Methods

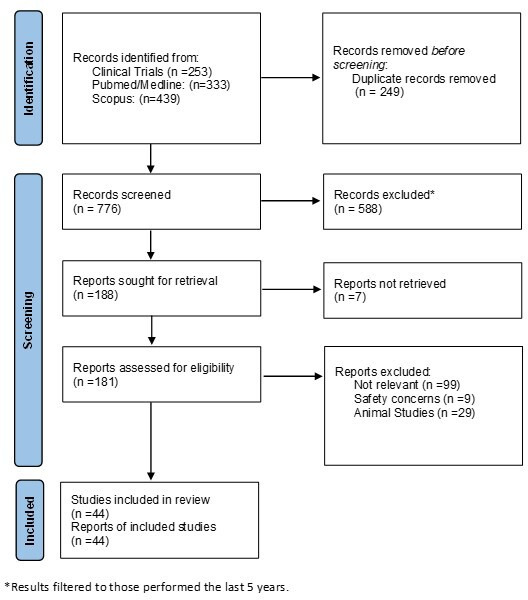

A comprehensive search using four databases, PubMed, Medline, Scopus and ClinicalTrials.gov was performed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method (figure 1). The key words ‘novel’, ‘treatment’, ‘biologics’, ‘IBD’, ‘Crohn’s’ and ‘UC’ were used. Further filtration for the existing studies to include clinical trials, reviews and meta-analysis only was used. The results were limited to those performed on the last 5 years. Animal studies and studies which were discontinued or failed were excluded. Total number of reports included on this review were 44.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Novel therapies

JAK-STAT inhibitors

The JAK family consists of four intracellular proteins (JAK 1,2,3 and tyrosine-kinase TYK2) associated to cytokine receptors, which mediate signal transduction on ligand binding, culminating in activation of transcription factors (STAT proteins) and gene expression via JAK-STAT pathway. JAK inhibitors block multiple signalling pathways interfering with production of cytokines and differentiation of effector T-cells.7 Tofacitinib licensed in UC belongs to this group.

Upadacitinib (UPA) is a selective JAK1 inhibitor. In the U-ACHIEVE phase IIΙ double-blind randomised controlled study (RCT) for moderate to severe UC, significantly higher proportion of patients receiving UPA 45 mg once daily) (26.1%) vs placebo/PBO (4.8%) achieved clinical remission at week 8 (p<0.001). Endoscopic remission was achieved in 13.7% vs 1.3% of placebo(p<0.001). A significant difference in clinical response favouring UPA versus PBO was seen as early as week 2 (60.1% vs 27.3%) and sustained over 8 weeks (79.0% vs 41.6%). The most common adverse effects were acne, creatine phosphokinase elevation and nasopharyngitis with UPA and worsening of UC and anaemia with PBO. Incidence of serious infection was similar between UPA and PBO. Neutropenia and lymphopenia were reported more frequently with UPA vs PBO. No adjudicated gastrointestinal perforation, major cardiovascular AEs, or thrombotic events and no active tuberculosis, malignancy, or deaths were reported.10 11

In U-ACCOMPLISH randomised controlled phase III trial, 8-week UPA 45 mg once daily has induced clinical remission in 33.5% of patients with UC, vs 4.5% of placebo, endoscopic remission in 44% vs 8.3% and histological remission in 36.7% vs 5.8% (p<0.001) induction treatment led to statistically significant improvements in clinical, endoscopic and combined endoscopic-histological endpoints. The treatment was well tolerated, and the safety profile and adverse effect prevalence was comparable with previous studies of UPA with no new safety signals identified.12

In the CD CELEST phase II trial, UPA did not significantly improve clinical remission at week 16 at any dose; however, endoscopic remission at week 12/16 was increased compared with placebo in a dose-dependent manner. Adverse events in both studies were consistent with prior reports including infections, viral reactivation and a case of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis.13 However, in preliminary results from U- EXCEED phase III RCT in patients with CD, 39% of patients achieved remission vs 21% of placebo at week 12.14

Oral JAK1 inhibitor filgotinib 200 mg daily in FITZROY CD phase 2 trial of 174 patients, was superior to placebo for induction of clinical remission (47% at 10 weeks vs 23% placebo group; p=0.0077). In phase 2b/3 SELECTION UC trial, the group receiving filgotinib 200 mg had clinical remission than placebo at week 10 (induction study A 26.1% vs 15.3%, p=0.0157). At week 58, 37.2% of patients given filgotinib 200 mg had clinical remission vs 11.2% placebo (p<0.0001). Clinical remission was not significantly different between filgotinib 100 mg and placebo at week 10 but was by week 58 (23.8% vs 13.5%, p=0.0420). Incidence of serious adverse events/adverse events was similar in both groups. Filgotinib 200 mg was efficacious in inducing and maintaining remission compared with placebo in this study.15 16

Oral brepocitinib and ritlecitinib have completed phase II clinical studies for moderate to severe UC (VIBRATO umbrella study) with primary results suggesting significantly higher proportion of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement (p<0.05) with ritlecitinib 70 mg and 200 mg and brepocitinib 30 mg and 60 mg vs placebo at week 817 (table 1).

Table 1.

JAK-STAT inhibitors

| JAK-STAT inhibitors | ||||||

| Name | Study | UC/Crohns | Mechanism of Action |

Authors | Results | Adverse events |

| Upadacitinib | U-EXCEED (NCT03345836) U-EXCEL (NCT03345849) |

Phase III/Phase III | JAK-1 inhibitor (but with greater selectivity for Jak-1) | Sandborn et al, 202013

Vermeire et al, 2021.12 Danese et al, 202111 |

CD→Clinical Remission in 49% vs placebo (29%) at Week 12 |

Acne, Elevated CPK, Nasopharyngitis, Neutropenia/Lymphopenia |

| U-ACHIEVE U-ACCOMPLISH |

UC→Clinical remission in 26.1% vs 4.8% of placebo and endoscopic remission in 13.7% vs 1.3% at Week 8 |

|||||

| Filgotinib | FITZROY | Phase III/Phase III | JAK1, JAK3 and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor |

Vermeire et al, 201715 | CD→47% achieving clinical remission at Week 10. | Infections Herpes Zoster, PE, Malignancy (Non melanoma skin cancer), Impaired Spermatogenesis |

| SELECTION | Feagan et al, 202116 | UC→Significant clinical remission (26.1%) vs placebo (15.3%) at Week 10 | ||||

| Brepocitinib, ritlecitinib | VIBRATOstudy ClinicalTrials. gov identifier: NCT02958865 | Phase IIB/Phase IIA | Dual TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor, binds to the active site in the catalytic domain |

Sandborn et al, 202117 | CD→Awaited | |

| ClinicalTrials. gov identifier: NCT03395184 | UC→Clinical and endoscopic remission at Week 8 |

|||||

JAK, Janus kinase; PE, Pulmonary Embolism; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Selective lymphocyte trafficking inhibitors

A new SC formulation of vedolizumab (VDZ) has been studied with the benefit of its convenient route of administration for patients who would like to avoid maintenance intravenous infusion therapy. SC administered VDZ was proven to be more effective than intravenous VDZ in Crohn’s patients for both induction and maintenance of remission. In two phase 3 RCTs, VISIBLE 1 and VISIBLE 2, 48.0% of patients receiving VDZ SC vs 34.3% of placebo group were in clinical remission at week 52 (p=0.008). Enhanced clinical response at week 52 was achieved by 52.0% vs 44.8% of patients receiving VDZ SC vs placebo, respectively (p=0.167). Steroid-free clinical remission was achieved in 45.3% of patients receiving VDZ SC vs 18.2% of placebo and 48.6% of anti-TNF-naive patients receiving VDZ SC vs 42.9% of those receiving placebo remained in clinical remission at week 52.

Injection site reaction was the only new safety finding observed for VDZ SC (2.9%). Similarly, in moderately to severely active UC patients, SC VDZ was effective as maintenance therapy in patients, who had a clinical response to intravenous VDZ induction therapy. It had demonstrated a favourable safety and tolerability profile as well. SC VDZ had also been shown to be drastically cost-effective. In TRAVELESS study, 124 patients agreed to transition from intravenous to SC VDZ. There were no statistically significant differences in disease activity scores between baseline and week 12. The most common adverse drug reaction reported was injection site reactions (15%). Based on this cohort, an expected reduction of £572 000 per annum was likely to be achieved.18–21

Etrolizumab is a gut selective monoclonal antibody (mAb) that selectively targets the β7 subunit of both α4β7 and α4E7 integrins.9 The HICKORY phase III study showed 105 mg 4 weekly etrolizumab-induced remission was significantly higher in patients with UC (18.5%) previously treated with anti-TNF agent at week 14 vs placebo (6.3%). There was no significant difference between groups in remission at week 62.22 In a double-blind RCT, the LAUREL study, no significant difference was noted between patients receiving 105 mg etrolizumab 4 weekly vs placebo at eeek 62 between those who reponed at Week 10.23 Similarly in GARDENIA study, in moderately to severely active UC patients, infliximab was used as an active comparator. Although the study did not show statistical superiority for the primary endpoint, etrolizumab performed similarly to infliximab from a clinical viewpoint and no significant difference was noted between patients receiving etrolizumab versus those who were receiving placebo.24

Carotegrast methyl (AJM300) is an oral small molecule inhibitor that targets the α4 subunit of α4β7 and α4β1. In a Japanese phase III double-blind RCT, AJM300 was well tolerated and induced a clinical response(defined as a reduction in Mayo Clinic score of 30% or more and 3 or more, a reduction in rectal bleeding score of 1 or more or rectal bleeding subscore of 1 or less, and an endoscopic subscore of 1 or less) in patients with moderately active UC who had an inadequate response or intolerance to mesalazine, at week 8. Patients receiving AJM300 960 mg three times per day had clinical response versus placebo, 46% vs 21%, respectively (p<0.0003) and endoscopic remission in 14% vs 3% of placebo (p<0.0057) The most common side effect was nasopharyngitis and no serious adverse effects were reported25 (table 2).

Table 2.

Novel selective lymphocyte trafficking inhibitors

| Selective lymphocyte trafficking inhibitors | ||||||

| Name | Study | UC/Crohns | Mechanism of Action |

Authors | Results | Adverse events |

| Vedolizumab subcutaneous | VISIBLE 1 and 2 | Phase III/Phase III | A4b7 inhibitor | Sandborn et al, 202020 | UC→ 46.2% of moderate UC patients who responded to IV VDZ sustained remission. | Reaction at injection site |

| Vermeire et al, 202218 | CD→48% of moderate Crohn’s patients who responded to 2 infusions of VDZ have sustained remission at week 52. |

|||||

| Etrolizumab | HICKORY LAUREL GARDENIA |

Phase III/III | Anti- β7 subunit mAb | Peyrin-Biroulet L et al, 2022.22

Vermeire S et al, 2022.23 Danese et al, 202224 |

UC→Clinical remission (UC patients previously treated with anti-TNF) 18.5% vs 6.3% of placebo at week 14 |

UC flare, Appendicitis, Anaemia |

| Carotegrast Methyl (AJM300) |

Phase III/- | Anti-a4 mAb (a4b7 and a4b1) |

Matsuoka et al, 2022.24 |

UC→Clinical response in 46% of moderately active UC patients and endoscopic remission in 14% at week 8 | Nasopharyngitis | |

IV, intravenous; UC, ulcerative colitis; VDZ, vedolizumab.

IL12/IL23 inhibitors

Mirikizumab, an antibody against the p19 subunit of IL-23, was effective in UC; in a phase 2 RCT, at week 12, 15.9% (p=0.066), 22.6% (p=0.004) and 11.5% (p=0.142) of patients in the 50 mg, 200 mg and 600 mg groups, respectively, achieved clinical remission, cf 4.8% given placebo. Extended doses of mirikizumab (additional 12 weeks) produced a clinical response in up to 50% of patients who did not have a response post-12 weeks induction, most of whom maintained clinical response for up to 52 weeks.26 27 Another CD RCT showed statistically significant endoscopic and clinical response at week 12 for all mirikizumab groups versus placebo (200 mg: 25.8%, p=0.079; 600 mg: 37.5%, p=0.003; 1000 mg: 43.8%, p<0.001; Placebo: 10.9 %).26–28 Several phase 3 UC trials are ongoing including LUCENT 1 (NCT03518086) and LUCENT 2 (NCT03524092).

Risankizumab (RZB) (mAb against p19 subunit of IL23) in a phase II randomised, double-blind study, was more effective than placebo for inducing clinical remission in patients with CD who had failed ≥1 anti-TNF agent (31% vs 15% placebo, p<0.05) at week 12. A phase 2/3 trial for induction (NCT03398148) and a phase 3 study for maintenance treatment (NCT03398135) are ongoing in UC.29 30 In ADVANCE, MOTIVATE and FORTIFY randomised controlled phase III trials, at week 12, significantly greater proportions of patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s receiving RZB 600 mg intravenous achieved clinical remission (54.3% vs 23.8%) and endoscopic response (43.9% vs 13.3%) (p<0.001). At week 12, statistically higher proportions of RZB-treated patients achieved the composite endpoint CDAI clinical remission and endoscopic response, as well as endoscopic remission in the colonic only and ileal–colonic subgroups (p<0.001). At week 52, significantly greater proportions of patients receiving RZB 360 mg SC achieved clinical remission (54% vs 37.1%) and endoscopic response, in the colonic and ileal–colonic subgroups only (p≤0.05). In patients with endoscopic remission after 12 weeks of intravenous RZB sustained endoscopic remission at week 52 vs withdrawal in the colonic and ileal–colonic subgroups (p≤0.01). Results for ileal only CD at week 12 were not promising but were limited by the small number of patients in this subgroup.30 31

Most adverse effects were gastrointestinal in nature with a low rate of opportunistic infections. No deaths, malignancies, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events, latent/active tuberculosis or herpes zoster were reported. Treatment-emergent but none neutralising anti-drug antibodies were developed. One of the patients with maternal use of RZB preconception and during the first trimester had an elective miscarriage because of fetal defects (fetal cystic hygroma and hydrops fetalis) 78 days after RZB was discontinued, however, this was considered by the investigator as having a reasonable possibility of being related to RZB.30

With brazikumab (mAb against the p19 subunit of IL23) in a phase 2a double-blind, placebo-controlled CD trial, 49.2% achieved clinical remission cf 26.7% controls at week 8. The study group were patients with moderate to severe CD who failed anti-TNF treatment. Two infusions at weeks 0 and 4 achieved a higher rate of clinical response at week 8 compared with placebo and continued SC q4 weeks led to ongoing clinical response and remission at week 24. Brazikumab was well tolerated in this study but there was no endoscopic/imaging evaluation. The most common adverse events were headache and nasopharyngitis. Brazikumab is in a CD phase IIb/III (NCT03759288) and a UC phase II/open label extension trial (NCT03616821).32 33

Guselkumab is another human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL23. A phase 2b/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study (NCT04033445, QUASAR) is ongoing in patients with moderately to severely active UC anticipated completion by July 2025.

Combination therapy with guselkumab and golimumab is under investigation in a phase 2a randomised study (NCT03662542, VEGA-moderate to severe UC). GALAXI 1 is a phase II RCT for CD regarding guselkumab. Patients were randomised to guselkumab 200 mg, 600 mg or 1200 mg at weeks 0, 4 and 8; ustekinumab (reference arm) 6 mg/kg intravenous at week 0 and 90 mg SC at week 8; or placebo intravenous. There were significant decreases of Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from baseline in all guselkumab groups cf placebo at week 12 and a higher proportion patients in all guselkumab groups who achieved clinical remission (200 mg: 54%, 600 mg: 56%, 1200 mg: 50%, placebo: 15.7%), clinical biomarker response (200 mg: 54%, 600 mg: 48%, 1200 mg: 42%, placebo: 11.8%) and endoscopic response (200 mg: 36%, 600 mg: 40%, 1200 mg: 36%, placebo: 11.8%). In biological failures, 45.5% (35/77) in the guselkumab group and 12.5% (3/24) with placebo achieved clinical remission at week 12. Rates of adverse effects, mainly infections were similar across all guselkumab groups cf placebo32 34 (table 3).

Table 3.

Novel IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors

| IL12/IL23 Inhibitors | ||||||

| Name | Study | UC/Crohns | Mechanism of action |

Authors | Results | Adverse events |

| Mirikizumab | LUCENT 1 LUCENT II | Phase III/Phase III | antibody against the p19 subunit of interleukin 23 | Sandborn et al, 202228

Sands et al, 202230 |

UC→Clinical remission (22.6% vs 4.8%) at Week 12 compared with placebo with sustained remission. | Nasopharyngitis, UC flare, headache, Gastroenteritis, nausea, Cough, anaemia |

| CD→Clinical and endoscopic remission (43.8% vs 10.9%) at Week 12 |

||||||

| Risankizumab | ADVANCE MOTIVATE FORTIFY | Phase III | Human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 | Ferrante et al, 202130

Bossuyt et al, 2022.31 |

CD→ Clinical remission in 54.3% and endoscopic response (>50% decrease in SES-CD score) in 43.9% at Week 12 |

Infections (opportunistic, fungal), Deranged LFTs, Fetal defects (fetal cystic hygroma and hydrops fetalis in a single case), Hypersensitivity reactions |

| Results not encouraging in patients with ileal disease only. | ||||||

| Brazikumab | Phase II | Human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL23 |

Sands et al, 201733 |

CD→Clinical response (100 point decrease in CDAI score) in 49.2% vs 26.7% of placebo at Week 8. |

Headache, Nasopharyngitis |

|

| Guselkumab | GALAXI-I | Phase II | Human monoclonal antibody against the p19 subunit of IL23 |

Sandborn et al, 202234 | CD→ 56% clinical remission and 40% endoscopic response at Week 12. |

Anaemia, Headache, Nasopharyngitis, Arthralgia, Upper respiratory tract infection, Abdominal pain |

CD, crohn’s disease; CDAI, crohn's disease activity index; LFTs, liver function tests; SES-CD, simple endoscopic score - crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

S1P receptor modulators

S1P is a ligand of G protein coupled receptors (S1P1-S1P5) responsible for controlling the egress of lymphocytes from lymphoid organs. The S1P/S1PR interaction can also result in internalisation of the S1PR which leads to decrease lymphocyte release from the lymphoid tissue into the circulation.35

Ozanimod is a S1P receptor modulator with selective affinity for S1PR1 and S1PR5. A phase III RCT in UC used oral 1 mg Ozanimod in a 10-week induction period with responders followed up to week 52. Incidence of clinical remission was significantly higher among ozanimod group than placebo during induction (18.4% vs 6.0%, p<0.001) and maintenance (37.0% vs 18.5%, p<0.001). Clinical response was significantly higher with ozanimod than placebo during induction (47.8% vs 25.9%, p<0.001) and maintenance (60.0% vs 41.0%, p<0.001). Incidence of infection with ozanimod was similar to placebo during induction and higher than placebo during maintenance. Serious infection occurred in <2%. Elevated liver aminotransferase levels were more common with ozanimod.36–38 Ozanimod has been approved for treatment of moderate to severe UC by FDA and European Commission. In stepstone phase II prospective single-arm CD trial, clinical remission was shown in 39.1%, and response in 56.5% of patients at week 12. Endoscopic and histological improvements were also seen within 12 weeks of initiating ozanimod therapy. Phase 3 placebo-controlled trials have been initiated.39

Etrasimod is an oral S1P receptor modulator with selectivity for S1PR1, S1PR4 and S1PR5. In a phase II UC trial, etrasimod 2 mg showed significantly higher clinical remission vs placebo (33% vs 8.1% of placebo, p<0.001) and endoscopic improvement (41.8% vs 17.8% of placebo, p<0.003). Phase III UC trials are currently recruiting (NCT03996369, NCT03945188, NCT03950232, NCT04176588). A phase II/III CD study is currently recruiting (NCT04173273). Most common adverse reactions were disease worsening, upper respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis and anaemia (table 4).32 40

Table 4.

Novel S1P-Receptor modulators

| Name | Study | UC/Crohns | Mechanism of action |

Authors | Results | Adverse events |

| Ozanimod | TOUCHSTONE TRUE NORTH | Phase III/Phase II | Oral S1P receptor modulator with selective affinity for S1PR1 and S1PR5 | Sandborn et al, 202136 37 | UC→Higher clinical response with Ozanimod in both induction (47.8% vs 25.9%) and maintenance (60% vs 41%) at Week 12. |

Bradycardia, deranged LFTs |

| STEPSTONE | Feagan et al, 202039 | CD→ Clinical response in 56.5% at Week 12 |

abdominal pain, lymphopenia, arthralgia, nausea | |||

| Etrasimod | Phase II/ | Oral S1P receptor modulator with selectivity for S1PR1, S1PR4 and S1PR5 |

Sandborn et al, 202040 |

UC→Clinical remission in 33% vs 8.1% of placebo and endoscopic improvement in 41.8% vs 17.8% at Week 12. |

Upper RT infections, Worsening of Crohn’s, Anaemia, Nasopharyngitis |

CD, Crohn’s disease; LFTs, liver function tests; RT, respiratory tract; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterases (PDE1-PDE11) are a group of intracellular enzymes that catalyse the breakdown of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate. PDE4 catalyses the breakdown of cAMP in multiple cells including T-cells, macrophages and monocytes leading to activation of nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB), promoting proinflammatory effects. Inhibition of PDE4 can lead to suppression of NF-κB, reducing TNF-α mRNA expression and production of nitric oxide and increasing synthesis of anti-inflammatory cytokines.32

Apremilast is an oral small-molecule PDE 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. A phase II RCT involving patients with active UC had shown clinical remission at week 12 by 31.6% of patients in the 30 mg apremilast group and 12.1% of patients in the placebo group (p<0.01). However, only 21.8% with 40 mg apremilast achieved clinical remission at week 12 (p<0.27). Although the primary endpoint of clinical remission was not met, a greater proportion of patients receiving apremilast had improvements in clinical, endoscopic and inflammatory markers at 12 weeks. Most frequent apremilast-associated adverse events were headache and nausea.41

Toll-like receptor 9 inhibitor

Cobitolimod is an oligodeoxynucleotide that binds to Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) on lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells. It activates TLR 9 leading to induction of regulatory T-cells that produce anti-inflammatory IL-10 in addition to suppressing proinflammatory TH-17 cells. Cobitolimod is a topical agent with low systemic absorption.32 A phase IIb RCT (CONDUCT) randomised patients with moderate to severe left-sided UC. The primary endpoint of clinical remission at week 6 was met by the 250 mg of cobatolimod group with 21% vs 7% in the placebo group (p<0.025).42

Micro-RNA-124 agonist

ABX464 is an oral agent that binds with the cap binding complex, allowing specific splicing of anti- inflammatory miR-124 (microRNA-124), modulating the proinflammatory cytokines. A phase II RCT in patients with UC treated with 50 mg of ABX464 found at week 8, 35.0% and 70.0% of patients in the achieved clinical remission and clinical response vs 11.1% and 33.3% in the placebo group. Endoscopic improvement and remission were observed in 50.0% and 10.0% of patients receiving ABX464, respectively, vs 11.1% each for placebo. Maintenance therapy with ABX464 sustained remission and brought additional patients into remission. The trial showed a good safety profile with headache to be the most common adverse effect reported. Phase II trials for CD were announced43 (table 5).

Table 5.

Novel categories in the pipeline

| Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors | ||||||

| Name | Study | UC/Crohns | Mechanism of Action |

Authors | Results | Adverse events |

| Apremilast | Phase II/- | Oral Inhibitor of PDE-4 | Danese et al, 2020.41 | UC->Clinical remission in 31.6% vs 12.1% of placebo. | Headache, nausea | |

| TL9 receptor inhibitor | ||||||

| Cobitolimod | CONDUCT | Phase IIb/- | TL-9 receptor agonist | Atreya et al, 2020.42 |

UC→Clinical remission in 21% vs 7% of placebo at Week 6 | Worsening of UC, pruritus, rash, abdominal hernia, fascia dehiscence, deep vein thrombosis |

| Small molecule inducing MiR-124 | ||||||

| ABX464 | Phase IIa/- | miR-124 expression inhibitor |

Vermeire et al, 202143 |

UC→Clinical remission in 35% vs 11.1% of placebo and endoscopic improvement in 50% at Week 8. |

Abdominal pain, headache, nasopharyngitis | |

PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Anti-TNF agents

A SC formulation of infliximab has recently been shown to be as effective as intravenous infliximab. A recent multicentre cohort study with 181 patients with IBD, majority with Crohn’s already on 8-weekly dosing of intravenous infliximab prior to switching and more than half (59.1%) on concomitant immunomodulatory therapy had shown no significant difference between baseline and repeat measurements at 3, 6 or 12 months for HBI, SCCAI, C reactive protein or FC. IN SC group, median infliximab level increased from a baseline of 8.9 µg/dL (range 0.4–16) to 16.0 µg/dL (range 2.3–16, p<0.001) at 3 months and serum levels stayed stable at 6 months (median 16 µg/dL, range 0.3–17.2) and 12 months (median 16 µg/dL, range 0.3–19.1, both p<0.001 compared with baseline). Treatment persistence, patient acceptance and satisfaction rates with SC CT-P13 were also very high. What is more, patients with perianal CD who were switched from intravenous to SC IFX had high rate of symptom free survival and treatment persistence at 6 months, with comparable efficacy and safety with intravenous Infliximab at 6 months.44 45

Conclusion

In the new COVID-19 era, immunosuppression has become a serious concern for most of our patients and optimising their treatment with tailored therapies has become a necessity to optimise the balance between treating their disease effectively and their concerns, regarding their immunosuppression and vulnerability. Medical practitioners should develop individualised treatment plans based on a comprehensive assessment of the patient. The treatment should be flexible and changed according to the patient’s response. Timely communication and close cooperation between doctors and patients are equally essential to effective treatment strategies.

The new ‘treat to target approach’ although cost-effective and difficult to achieve, has also identified a considerable number of patients who lost response after their treatment. Optimisation of IBD treatment also involves moving to a new category of oral agents in the future, that will not require hospitalisation that is not only stressful for many of our patients but also cost-demanding.9

Although, more clinical data are required on long-term safety, with deepening of the research around IBD pathogenesis, new therapies are coming into view, with a safer adverse effect profile and promising results not only on patients with IBD with mild disease but also for those who are failing one or more biological agents and those who would like to avoid a colectomy at any cost. We still confront with many unresolved challenges regarding efficacy versus safety and more long-term data are required to offer targeted therapies that minimise the risk and optimise outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to writing and reviewing the document.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017;390:2769–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee HS, Park S-K, Park DI. Novel treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Korean J Intern Med 2018;33:20–7. 10.3904/kjim.2017.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan N, Patel D, Xie D, et al. Adherence of Infusible biologics during the time of COVID-19 among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Veterans Affairs cohort study. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1592–4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gulacsi L, Pentek M, Rencz F, et al. Biosimilars for the management of inflammatory bowel diseases: economic considerations. Curr Med Chem 2019;26:259–69. 10.2174/0929867324666170406112304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Troncone E, Marafini I, Del Vecchio Blanco G, et al. Novel Therapeutic Options for People with Ulcerative Colitis: An Update on Recent Developments with Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2020;13:131–9. 10.2147/CEG.S208020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yadav PK, Chen C, Liu Z. Potential role of NK cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011;2011:1–6. 10.1155/2011/348530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahluwalia B, Moraes L, Magnusson MK, et al. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and mechanisms of biological therapies. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018;53:379–89. 10.1080/00365521.2018.1447597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grossberg LB, Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Review article: emerging drug therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;55:789–804. 10.1111/apt.16785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai Z, Wang S, Li J. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a comprehensive review. Front Med 2021;8. 10.3389/fmed.2021.765474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parigi TL, D'Amico F, Danese S. Upadacitinib for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis treatment: hitting the selective JAKpot. Gastroenterology 2021;160:1472–4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, et al. OP24 efficacy and safety of upadacitinib induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from the phase 3 U-ACHIEVE study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:S022–4. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab075.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vermeire S, Danese S, Zhou W, et al. OP23 efficacy and safety of upadacitinib as induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from phase 3 U-ACCOMPLISH study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:S021–2. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab075.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Loftus EV. Efficacy and Safety of Upadacitinib in a Randomized Trial of Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. A Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Upadacitinib (ABT-494) in Participants with Moderately to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease Who Have Inadequately Responded to or Are Intolerant to Conventional and/or Biologic Therapies. ClinicalTrials.gov, 2021. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03345849 [Accessed 9 Nov 2021].

- 15. Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease treated with filgotinib (the Fitzroy study): results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:266–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32537-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feagan BG, Danese S, Loftus EV, et al. Filgotinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (selection): a phase 2B/3 double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2021;397:2372–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00666-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sandborn W, Danese S, Leszczyszyn J, et al. OP33 oral ritlecitinib and brepocitinib in patients with moderate to severe active ulcerative colitis: data from the VIBRATO umbrella study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:S030–1. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab075.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vermeire S, D'Haens G, Baert F, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous Vedolizumab in patients with moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: results from the visible 2 randomised trial. J Crohns Colitis 2022;16:27–38. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schultz BG, Diakite I, Carter JA, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of intravenous vedolizumab vs subcutaneous adalimumab for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2021;27:1592–600. 10.18553/jmcp.2021.27.11.1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sandborn WJ, Baert F, Danese S, et al. Efficacy and safety of Vedolizumab subcutaneous formulation in a randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:562–72. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ventress E, Young D, Rahmany S, et al. Transitioning from intRavenous to subcutAneous VEdolizumab in patients with infLammatory bowEl disease (TRAVELESS). J Crohns Colitis 2021. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab224. [Epub ahead of print: 22 Dec 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Hart A, Bossuyt P, et al. Etrolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis in patients previously treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (HICKORY): a phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:128–40. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00298-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vermeire S, Lakatos PL, Ritter T, et al. Etrolizumab for maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (laurel): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:28–37. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00295-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Danese S, Colombel J-F, Lukas M, et al. Etrolizumab versus infliximab for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (Gardenia): a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:118–27. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00294-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsuoka K, Watanabe M, Ohmori T, et al. AJM300 (carotegrast methyl), an oral antagonist of α4-integrin, as induction therapy for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022. 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00022-X. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Mar 2022]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sandborn WJ, Ferrante M, Bhandari BR, et al. Efficacy and safety of continued treatment with Mirikizumab in a phase 2 trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022;20:105–15. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sandborn WJ, Ferrante M, Bhandari BR, et al. Efficacy and safety of Mirikizumab in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:537–49. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Kierkus J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Mirikizumab in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2022;162:495–508. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noviello D, Mager R, Roda G, et al. The IL23-IL17 immune axis in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: successes, defeats, and ongoing challenges. Front Immunol 2021;12:611256. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.611256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrante M, Feagan BG, Panés J, et al. Long-Term safety and efficacy of Risankizumab treatment in patients with Crohn's disease: results from the phase 2 open-label extension study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:2001–10. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bossuyt P, Bresso F, Dubinsky M, et al. OP40 Efficacy of risankizumab induction and maintenance therapy by baseline Crohn’s Disease location: Post hoc analysis of the phase 3 ADVANCE, MOTIVATE, and FORTIFY studies. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2022;16:i048. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab232.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al-Bawardy B, Shivashankar R, Proctor DD. Novel and emerging therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:651415. 10.3389/fphar.2021.651415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sands BE, Chen J, Feagan BG, et al. Efficacy and safety of MEDI2070, an antibody against interleukin 23, in patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease: a phase 2A study. Gastroenterology 2017;153:77–86. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sandborn WJ, D'Haens GR, Reinisch W, et al. Guselkumab for the treatment of Crohn's disease: induction results from the phase 2 GALAXI-1 study. Gastroenterology 2022;162:1650–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang J, Goren I, Yang B, et al. Review article: the sphingosine 1 phosphate/sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor axis - a unique therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;55:277–91. 10.1111/apt.16741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D'Haens G, et al. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1280–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa2033617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer S, et al. Long-Term efficacy and safety of Ozanimod in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from the open-label extension of the randomized, phase 2 touchstone study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:1120–9. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. William S, Geert D'Haens, Doug W, et al. P025 Ozanimod Efficacy, Safety, and Histology in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis During Induction in the Phase 3 True North Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:S6–7. 10.14309/01.ajg.0000722896.32651.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Danese S, et al. Ozanimod induction therapy for patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease: a single-arm, phase 2, prospective observer-blinded endpoint study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:819–28. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30188-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Zhang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Etrasimod in a phase 2 randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:550–61. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Danese S, Neurath MF, Kopoń A, et al. Effects of apremilast, an oral inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4, in a randomized trial of patients with active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:2526–34. 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Atreya R, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Klymenko A, et al. Cobitolimod for moderate-to-severe, left-sided ulcerative colitis (conduct): a phase 2B randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging induction trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:1063–75. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30301-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vermeire S, Hébuterne X, Tilg H, et al. Induction and long-term follow-up with ABX464 for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: results of phase IIA trial. Gastroenterology 2021;160:2595–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith PJ, Critchley L, Storey D, et al. Efficacy and safety of elective switching from intravenous to subcutaneous infliximab (Ct-P13): a multi-centre cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2022. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac053. [Epub ahead of print: 07 Apr 2022]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith PJ, Storey D, Gregg B. PMO-28 Efficacy of subcutaneous infliximab in perianal crohn’s disease. Gut 2021;70:A91–2. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-BSG.167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]