Highlights

-

•

Economic hardship (job status, money to buy food) is a determinant of food security.

-

•

Some demographics (education, household size) are determinants of food security.

-

•

Food access has been affected by COVID-19 and impacts food security.

-

•

COVID-19 has exacerbated determinants of food security (i.e., economic hardships)

-

•

Public health should use the social ecological model to address determinants of food security.

Abbreviations: SEM, Social Ecological Model; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; P-EBT, Pandemic-Electronic Benefit Transfer

Keywords: Food security, COVID-19 pandemic, Social Ecological Model, Safety net interventions

Abstract

This paper examines risk factors influencing food insecurity during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in a state in the U.S. heavily impacted by it and offers recommendations for multi-sector intervention.

The U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey was analyzed to evaluate the impacts of COVID-19 on food security in Massachusetts from April 2020 through March 2021 using a study sample of 57,678 participants. Food security was defined as a categorical variable (food security, marginal food security, low food security, very low food security) and binary variable (food security and food insecurity). Known or suspected factors that contribute to it, such as childcare, education, employment, housing, and transportation were examined in multivariate logistic regression models. Data imputation methods accounted for missing data.

Sociodemographic characteristics, including lower education level and living in a household with children, were determinants of food insecurity. Another factor that influenced food insecurity was economic hardships, such as unemployment, being laid off due to COVID-19, not working due to concerns about contracting or spreading COVID-19, or not having enough money to buy food. A third factor influencing food insecurity was food environment, such as lack of geographic access to healthy foods. Some of these factors have been exacerbated by the pandemic and will continue to impact food security. These should be addressed through a comprehensive approach with public health efforts considering all levels of the social ecological model and the context created by the pandemic.

1. Introduction

Food insecurity is a multi-faceted issue, influenced by a variety of environmental and personal determinants that requires a comprehensive solution. (USDA, 2021) Numerous local and national programs and policies within the U.S. aim to change the availability and accessibility of foods for vulnerable populations. (Clay et al., 2018) Even with these efforts, food insecurity increased among certain populations, such as Black and Hispanic people, households with children, and single-parent households over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2020).

Food security is a combination of a person’s access to sufficient food at all times, knowledge to make appropriate food choices, and availability of resources (i.e., money) to obtain and purchase nutritious foods. (Savoie-Roskos et al., 2016, USDA, 2021) It is complicated to measure because it is usually self-reported, people perceive survey questions differently, and stigma surrounds food insecurity. (USDA Food Insecurity, 2021) Food insufficiency occurs when a household sometimes or often does not have enough food to eat. (USDA Food Insecurity, 2021) Food insufficiency is tracked for surveillance and intervention efforts and often used as a proxy for food insecurity. While the definition of food security focuses on a household’s ability to acquire food, the definition of food insufficiency encompasses the total availability of adequate food for consumption, regardless of how it is acquired. (USDA Food Insecurity, 2021) These concepts overlap considerably so surveillance efforts that categorize people as food secure also categorize them as food sufficient. While food security is a more precise measure, food sufficiency is easier to collect and interpret so it has been used in COVID-19 surveillance.

COVID-19 has exacerbated many of the well-documented determinants of food insecurity in the U.S. at all levels (individual, interpersonal, community, institution, society/policy) of the social ecological model (SEM). (Decker and Flynn, 2018, Kilanowski, 2017, Hernandez, 2015, Hunger Poverty in America - Food Research Action Center. Published, 2020) The SEM is a model that shows the impact of the interaction between the charactistics of all five levels on health. (Kilanowski, 2017) Among households in which one member lost a job or source of income due to COVID-19, 59% were food insecure, while in households in which more than one member lost a job or source of income, 72% were food insecure. (Wolfson and Leung, 2020) Unemployment rates in the U.S. increased sharply at the beginning of the pandemic from 3.5% in February 2020 to 15% in April 2020. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021) Since then, the rate of unemployment has declined to 4.6% but the rate of decline has been more rapid for certain populations. (Wolfson and Leung, 2020).

Disaster situations, including pandemics, hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes, disproportionately impact those most at risk for experiencing food insecurity. () These emergency situations cause disruptions in food supply chains, closure of food stores, depleted financial resources, limited public transportation, mental health issues, unavailability of food, housing insecurity, and fewer job opportunities. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021, Clay and Ross, 2020) Even in non-pandemic times, safety net assistance programs exist, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), food banks, food pantries, soup kitchens, school-based programs, and assistance for seniors. (Fan et al., 2021, Online, 2021) Despite this, accessibility of these programs still remains an issue. Although 12% of the U.S. population received SNAP benefits in 2019, one in six eligible people did not. (xxxx, Access, 2021).

The U.S. Census Bureau launched the Household Pulse Survey, (Bureau UC Measuring Household Experiences, 2021) a publicly available dataset that allows for examination of the impacts of COVID-19 in the U.S. and by state, to understand how Americans have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first four months of the pandemic, food insecurity in the U.S. increased by 26%. (Ohri-Vachaspati et al., 2021) Massachusetts had the greatest increase (47%) across the U.S. in food insecurity in the beginning of the pandemic. In 2019, 1 in 12 people in Massachusetts were food insecure, 1 in 8 people in 2020, and 1 in 10 people in 2021. (Levels et al., 2021).

Understanding the determinants of food insecurity allows for targeted approaches, especially with the shift caused by the pandemic on factors most influential, such as economic hardship and food environment, warranting novel solutions to address food insecurity. This paper examined the Household Pulse Survey data for Massachusetts to understand which determinants of food insecurity within the broader factors have an influence on food insecurity. We hypothesized that certain determinants that have been heavily influenced by COVID-19, including economic harship, living in a food environment that does not offer adequate access to food, and being a part of specific demographic groups (i.e., people of color, single parents), have an impact on food security. Recommendations, organized by the levels of the SEM, are proposed for a multi-pronged approach that can eliminate the burden caused by food insecurity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

The U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey was released in March 2020 and is a 20-minute online survey asking households about the social and economic effects of COVID-19. (Bureau UC Household Pulse Survey Data Tables, 2021) This study focuses specifically on questions related to food insecurity; as measured through food insufficiency, and known or suspected factors that contribute to it, such as childcare, education, employment, housing, and transportation. (Decker and Flynn, 2018, Makelarski et al., 2017) Given this study was based on a publicly available anonymized database, it was exempt from ethical compliance.

2.2. Data collection procedures

To date, the Household Pulse Survey has been administered in several phases throughout the pandemic. (USDA, 2021) In the first phase, data was collected and released weekly; in all subsequent phases, data was collected and released every two weeks. (Census Bureau, 2021) Survey data is publicly available after collection. Data for this study reflects responses from phases encompassing April 23, 2020 through March 1, 2021 – approximately one year after the start of COVID-19.

Households were sampled from the Census Bureau’s Master Address File and supplemented by the Census Bureau Contact Frame, which has been the Census Bureau’s sampling strategy since 2013. These were used to produce a sufficiently large enough sample accounting for no response with sampling rates determined at the state level. Households received the survey by email or text; while yielding lower response rates than expected (3.8% versus 5%), it allowed for implementation efficiency, reducing cost and increasing timeliness of response. Survey questions were constructed in consultation with nine independent subject-matter experts and cognitive tested with recommendations informing revisions to future phases of the survey. The surveys were administered via the Census Bureau’s online data collection platform (Qualtrics). (Fields et al., 2020).

2.3. Study Sample

The Household Pulse Survey randomly samples people based on their zip code. (Census Bureau, 2021) Data is available at the national and state level. Analyses were restricted to Massachusetts residents resulting in 57,678 survey participants over the study period.

2.4. Variable Definitions

The outcome of interest was food insecurity, which was measured through food insufficiency. Food insecurity is typically measured through ten questions describing food eaten in the household in the past 12 months, while food insufficiency is measured in a single question that asks respondents to describe the food eaten in their household in the past seven days and is commonly used as a proxy for food insecurity. In consultation with the USDA’s Economic Research Service, the questions on food sufficiency were constructed to align with questions on other surveys to address food insecurity during the pandemic. (Fields et al., 2020) Food insecurity was defined by the question that asked participants if they often did not have enough to eat, sometimes did not enough to eat, had enough but not always the kinds of foods they wanted to eat, or had enough of the kinds of food they wanted to eat within the last seven days. (USDA, 2021, Household and Tables, 2021) The study explored this as a categorical variable [food security (enough of the kinds of food the household wanted to eat), marginal food security (enough food to eat, but not always the kinds of food the household wanted to eat), low food security (sometimes not enough to eat), and very low food security (often not enough to eat)] (USDA, 2021, Census Bureau, 2021) and a binary variable [food secure (having “enough of the kids of food I/we wanted to eat” and “enough, but not always the kinds of foods I/we wanted to eat”) or food insecure (“sometimes not enough to eat” and “often not enough to eat”)]. (USDA, 2021, Census Bureau, 2021).

Demographic characteristics examined included sex, race/ethnicity, age (calculated based on date of birth and survey completion), education level, marital status, household size, and number of children in the household. Employment status was characterized as “work for pay” (i.e., employed), “loss of employment,” and “expecting loss of employment,” with unemployment defined by combining the latter two categories. For those who “work for pay,” the survey asked for type of employment and telework status; for those not working, the survey asked for reasons for not working in the last 7 days. Other determinants explored included receiving SNAP benefits, taking fewer trips to the grocery store in the last 7 days, and receiving free meals or groceries in the last 7 days, while participants were asked questions on access and affordability of food over the next four weeks including being able to afford enough food for children and where those free meals/groceries were accessed (i.e., school programs, food pantries/food banks, religious institutions, soup kitchens, home delivered meals, friends and family).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Weekly and bi-weekly phase data was combined into a single dataset. Per protocols used by the U.S. Census Bureau and relayed to the study team in direct correspondence, and after descriptive statistics were conducted, data imputation was conducted on all missing outcome and exposure variables of interest using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm with chained equations where the data was imputed across 20 datasets. Analyses were performed across all 20 imputed datasets and the results were combined to provide inferential statistics. (Allison, , 2012, Enders, , 2010, Allison, 2005).

Descriptive analyses were conducted on demographic characteristics and determinants and significance was examined across food security status using Wald’s chi-square test with an alpha level of 0.05. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess variables associated with the dichotomous food security outcome. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to control for known and suspected covariates in adjusted analyses for the categorical food security outcome. Variable selection in the multivariable models was a combination of 1) variables shown to be associated with the outcome (p-value threshold of 0.05), and 2) potential confounding variables based on prior knowledge of the outcome variable. Certain variables were removed from the multivariable analysis due to collinearity with other variables in the model (assessed using a VIF threshold of 10) and potential reverse causality problems, determined by knowledge of the outcome variable, which would make it difficult to interpret the measure of effect. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Findings

A variety of variables were assessed across food security status including for demographic characteristics (Table 1) and economic and food-related characteristics (Table 2). The majority of Massachusetts survey participants were younger than 60 years old (64.6%); female (59.2%); not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (92.8%); White (86.4%); and, had no children in their household (66.7%) (Table 1). Younger people experienced food insecurity at higher proportions, with nearly one-quarter of 30–49 year olds experiencing very low food security. The highest proportion of food secure people had a graduate degree (40.4%) and the highest proportion of very low food secure people had some college (28.1%). Most food secure and marginal food secure people were married (61.6% and 50.9%, respectively) while the majority of low food secure and very low food secure people were never married (36.1% and 42.8%, respectively). The majority of food secure people lived in a two-person household (38.9%) while the majority of very low food secure people lived in a one-person household (24%). The proportion who reported being food secure decreased across the three phases of survey administration.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for a sample of survey respondents in Massachusetts to the Census Household Pulse Survey, March 2020-March 2021 (n = 57678)1.

|

Food Security2 (n = 39134) n (%) |

Marginal Food Security2 (n = 12620) n (%) |

Low Food Security2 (n = 2086) n (%) |

Very Low Food Security2 (n = 467) n (%) |

Total1 (n = 54307) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category3 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 18–29 | 2868 (7.3) | 1099 (8.7) | 241 (11.6) | 54 (11.6) | 4262 (7.8) | |

| 30–39 | 6887 (17.6) | 2409 (19.1) | 456 (21.9) | 109 (23.3) | 9861 (18.2) | |

| 40–49 | 7034 (18.0) | 2466 (19.5) | 503 (24.1) | 117 (25.0) | 10,120 (18.6) | |

| 50–59 | 7672 (19.6) | 2619 (20.8) | 461 (22.1) | 105 (22.5) | 10,857 (20.0) | |

| 60–69 | 8148 (20.8) | 2499 (19.8) | 330 (15.8) | 59 (12.6) | 11,036 (20.3) | |

| 70+ | 6525 (16.7) | 1528 (12.1) | 95 (4.6) | 23 (4.9) | 8171 (15.1) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||||

| Male | 16,340 (41.8) | 4650 (36.9) | 760 (36.4) | 168 (36.0) | 21,918 (40.4) | |

| Female | 22,794 (58.3) | 7970 (63.2) | 1326 (63.6) | 299 (64.0) | 32,389 (59.6) | |

| Ethnicity4 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 37,073 (94.7) | 11,342 (89.9) | 1630 (78.1) | 351 (75.2) | 50,396 (92.8) | |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 2061 (5.3) | 1278 (10.1) | 456 (21.9) | 116 (24.8) | 3911 (7.2) | |

| Race4 | ||||||

| White | 34,745 (88.8) | 10,391 (82.3) | 1432 (68.7) | 338 (72.4) | 46,906 (86.4) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 1371 (3.5) | 889 (7.0) | 328 (15.7) | 50 (10.7) | 2638 (4.9) | |

| Asian | 2079 (5.3) | 747 (6.0) | 91 (4.4) | 16 (3.4) | 2933 (5.4) | |

| Multiracial | 939 (2.4) | 593 (4.7) | 235 (11.3) | 63 (13.5) | 1830 (3.3) | |

| Education | <0.0001 | |||||

| Less than high school | 97 (0.3) | 97 (0.8) | 53 (2.5) | 24 (5.1) | 271 (0.5) | |

| Some high school | 277 (0.7) | 198 (1.6) | 103 (4.9) | 18 (3.9) | 596 (1.1) | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 2670 (6.8) | 1472 (11.7) | 445 (21.3) | 110 (23.6) | 4697 (8.7) | |

| Some college | 4739 (12.1) | 2630 (20.8) | 586 (28.1) | 131 (28.1) | 8086 (14.9) | |

| Associate’s degree | 2636 (6.7) | 1310 (10.4) | 293 (14.1) | 58 (12.4) | 4297 (7.9) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 12,921 (33.0) | 3646 (28.9) | 406 (19.5) | 77 (16.5) | 17,050 (31.4) | |

| Graduate degree | 15,794 (40.4) | 3267 (25.9) | 200 (9.6) | 49 (10.5) | 19,310 (35.6) | |

| Marital Status | <0.0001 | |||||

| Married | 24,106 (61.6) | 6428 (50.9) | 667 (32.0) | 107 (22.9) | 31,308 (57.7) | |

| Widowed | 1724 (4.4) | 598 (4.7) | 85 (4.1) | 27 (5.8) | 2434 (4.5) | |

| Divorced | 4422 (11.3) | 2043 (16.2) | 453 (21.7) | 96 (20.6) | 7014 (12.9) | |

| Separated | 498 (1.3) | 332 (2.6) | 118 (5.7) | 35 (7.5) | 983 (1.8) | |

| Never married | 8214 (21.0) | 3137 (24.9) | 752 (36.1) | 200 (42.8) | 12,303 (22.7) | |

| Unknown5 | 170 (0.43) | 82 (0.65) | 11 (0.53) | 2 (0.43) | 265 (0.5) | |

| Household Size | <0.0001 | |||||

| 1 person | 6321 (16.2) | 2179 (17.3) | 381 (18.3) | 112 (24.0) | 8993 (16.6) | |

| 2 people | 15,180 (38.9) | 4113 (32.6) | 552 (26.5) | 92 (19.7) | 19,937 (36.7) | |

| 3 people | 6809 (17.4) | 2450 (19.4) | 421 (20.2) | 91 (19.5) | 9771 (18.0) | |

| 4 people | 6926 (17.7) | 2192 (17.4) | 341 (16.4) | 75 (16.1) | 9534 (17.6) | |

| 5 people | 2669 (6.8) | 1055 (8.4) | 202 (9.7) | 46 (9.9) | 3972 (7.3) | |

| 6 + people | 1229 (3.1) | 631 (5.0) | 189 (9.1) | 51 (10.9) | 2100 (3.9) | |

| Number of Children in Household | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 26,761 (68.4) | 8061 (63.9) | 1132 (54.3) | 255 (54.6) | 36,209 (66.7) | |

| 1 | 5462 (14.0) | 2078 (16.5) | 434 (20.8) | 88 (18.8) | 8062 (14.8) | |

| 2 | 5166 (13.2) | 1684 (13.3) | 322 (15.4) | 71 (15.2) | 7243 (13.3) | |

| 3 | 1392 (3.6) | 607 (4.8) | 137 (6.6) | 23 (4.9) | 2159 (3.9) | |

| 4 | 271 (0.7) | 133 (1.1) | 40 (1.9) | 15 (3.2) | 459 (0.8) | |

| 5 | 82 (0.2) | 57 (0.5) | 21 (1.0) | 15 (3.2) | 175 (0.3) | |

| Phase of Survey Administration | <0.0001 | |||||

| Phase 1 (April 23, 2020 – July 21, 2020) | 18,966 (48.5) | 6805 (53.9) | 924 (44.3) | 172 (36.8) | 26,867 (49.5) | |

| Phase 2 (August 19, 2020 – October 26, 2020) | 9244 (23.6) | 2840 (22.5) | 525 (25.2) | 134 (28.7) | 12,743 (23.5) | |

| Phase 3 (October 28, 2020 – March 29, 2021) | 10,924 (27.9) | 2975 (23.6) | 637 (30.5) | 161 (34.5) | 14,697 (27.1) | |

Analyses were conducted using frequencies and Wald’s chi-square statistical test, significance = 0.05.

1. Descriptive analyses were conducted before data imputation. Missing values (n = 3371) are due to missed questions in the outcome variable (i.e., food security status).

2. Definitions include: food security (enough of the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); marginal food security (enough, but not always the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); low food security (sometimes not enough to eat); very low food security (often not enough to eat).

3. Age categories derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, 2019.

4. Ethnicity and race categories were determined by the categories listed on the Census Pulse Household Survey.

5. Unknown responses indicate the survey respondent left the response for that question blank on the survey.

Table 2.

Economic and food-related characteristics by food security status for a sample of survey respondents in Massachusetts to the Census Household Pulse Survey, March 2020 – March 2021 (n = 57678)1.

|

Food Security2 (n = 39134) n (%) |

Marginal Food Security2 (n = 12620) n (%) |

Low Food Security2 (n = 2086) n (%) |

Very Low Food Security2 (n = 467) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS | |||||

| Loss of employment3 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 13,102 (33.5) | 6649 (52.7) | 1498 (71.8) | 354 (75.8) | |

| No | 25,985 (66.4) | 5948 (47.1) | 587 (28.1) | 111 (23.8) | |

| Unknown4 | 47 (0.1) | 23 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Expecting loss of employment3 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 6893 (17.6) | 4733 (37.5) | 1191 (57.1) | 290 (62.1) | |

| No | 32,161 (82.2) | 7840 (62.1) | 890 (42.7) | 172 (36.8) | |

| Unknown | 80 (0.2) | 47 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | |

| Any work for pay/profit5 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 25,721 (65.7) | 7154 (56.7) | 906 (43.4) | 149 (31.9) | |

| No | 13,377 (34.2) | 5446 (43.2) | 1173 (56.2) | 315 (67.5) | |

| Unknown | 36 (0.1) | 20 (0.2) | 7 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | |

| Employment Type6 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Government | 3238 (12.6) | 1041 (14.6) | 115 (12.7) | 22 (14.8) | |

| Private company | 14,437 (56.1) | 3959 (55.3) | 529 (58.4) | 90 (60.4) | |

| Non-profit organization | 4852 (18.9) | 1262 (17.6) | 145 (16.0) | 14 (9.4) | |

| Self-employed | 2578 (10.0) | 671 (9.4) | 70 (7.7) | 16 (10.7) | |

| Family business | 363 (1.4) | 115 (1.6) | 24 (2.7) | 4 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 253 (1.0) | 106 (1.5) | 23 (2.5) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Main source for not working for pay/profit 7,8 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Did not want to be employed | 597 (4.5) | 102 (1.9) | 9 (0.8) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Sick with coronavirus symptoms | 99 (0.7) | 108 (1.9) | 40 (3.4) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Caring for someone with coronavirus symptoms | 23 (0.2) | 23 (0.4) | 9 (0.8) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Caring for children not in school/daycare | 588 (4.4) | 401 (7.4) | 125 (10.7) | 34 (10.8) | |

| Caring for an elderly person | 125 (0.9) | 91 (1.7) | 17 (1.5) | 9 (2.9) | |

| Concerned about getting/spreading coronavirus | 394 (3.0) | 392 (7.2) | 139 (11.9) | 41 (13.0) | |

| Retired | 6925 (51.8) | 1594 (29.3) | 107 (9.1) | 19 (6.0) | |

| Employer experienced reduction of business or furlough due to pandemic | 926 (6.9) | 542 (10.0) | 115 (9.8) | 26 (8.3) | |

| Laid off due to pandemic | 723 (5.4) | 514 (9.4) | 148 (12.6) | 34 (10.8) | |

| Employer closed temporarily during pandemic | 749 (5.6) | 521 (9.6) | 124 (10.6) | 30 (9.5) | |

| Employer went out of business during pandemic | 82 (0.6) | 81 (1.5) | 33 (2.8) | 18 (5.7) | |

| Other reason | 1680 (12.6) | 819 (15.0) | 244 (20.8) | 67 (21.3) | |

| I was concerned about getting or spreading the coronavirus | 356 (2.7) | 224 (4.1) | 59 (5.0) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Unknown | 110 (0.8) | 34 (0.6) | 4 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Telework 9 | <0.0001 | ||||

| At least one adult substituted typical work with telework | 11,973 (59.4) | 2656 (45.7) | 282 (24.3) | 40 (13.6) | |

| No adults substituted typical work with telework | 5192 (25.7) | 2125 (36.5) | 588 (50.6) | 163 (55.3) | |

| No change in telework | 2421 (12.0) | 815 (14.0) | 231 (19.9) | 80 (27.1) | |

| Unknown | 582 (2.9) | 219 (3.8) | 61 (5.3) | 12 (4.1) | |

| FOOD ENVIRONMENT AND ACCESS | |||||

| Receiving benefits from SNAP9 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 762 (3.8) | 767 (13.3) | 400 (35.0) | 121 (41.7) | |

| No | 19,208 (95.5) | 4958 (86.1) | 733 (64.1) | 167 (57.6) | |

| Unknown | 147 (0.7) | 34 (0.6) | 11 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Fewer trips to the grocery store due to pandemic in the last 7 days9 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 13,981 (69.3) | 4947 (85.1) | 963 (82.9) | 225 (76.3) | |

| No | 6088 (30.2) | 847 (14.6) | 182 (15.7) | 67 (22.7) | |

| Unknown | 99 (0.5) | 21 (0.4) | 17 (1.5) | 3 (1.0) | |

| People in household receive free groceries or a free meal in the last 7 days | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 1500 (3.8) | 1115 (8.9) | 341 (16.5) | 83 (18.0) | |

| No | 37,497 (95.9) | 11,360 (90.7) | 1715 (82.9) | 372 (80.7) | |

| Unknown | 85 (0.2) | 56 (0.5) | 12 (0.6) | 6 (1.3) | |

| Locations where people in household received free groceries or a free meal in the last 7 days8, 10 | |||||

| Free meals through the school or other programs for children | 715 (47.7) | 498 (45.0) | 149 (44.4) | 25 (30.9) | 0.0178 |

| Food pantry or food bank | 259 (17.3) | 343 (31.0) | 121 (36.0) | 41 (50.6) | <0.0001 |

| Home delivered meal service (ex. Meals on Wheels) | 84 (5.6) | 68 (6.1) | 26 (7.7) | 8 (9.9) | 0.2429 |

| Church, synagogue, temple, mosque, or other religious organization | 92 (6.1) | 106 (9.6) | 46 (13.7) | 15 (18.5) | <0.0001 |

| Shelter or soup kitchen | 6 (0.4) | 14 (1.3) | 14 (4.2) | 8 (9.9) | <0.0001 |

| Other community program | 307 (20.5) | 232 (21.0) | 68 (20.2) | 19 (23.5) | 0.9186 |

| Family, friends, neighbors | 296 (19.8) | 267 (24.1) | 110 (32.7) | 28 (34.6) | <0.0001 |

| The children were not eating enough because we just couldn’t afford enough food in the last 7 days8, 11 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Often true | N/A | 38 (1.1) | 74 (10.0) | 64 (38.3) | |

| Sometimes true | N/A | 437 (13.2) | 383 (51.6) | 55 (32.9) | |

| Never true | N/A | 2804 (84.4) | 275 (37.1) | 46 (27.5) | |

| Unknown | N/A | 45 (1.4) | 10 (1.4) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Why did you not have enough to eat?8,12 | |||||

| Couldn't afford to buy more food | N/A | 3297 (26.3) | 1620 (78.3) | 384 (83.3) | <0.0001 |

| Couldn’t get out to buy food | N/A | 1604 (12.8) | 375 (18.1) | 105 (22.8) | <0.0001 |

| Afraid to go or didn’t want to go out to buy food | N/A | 4327 (34.5) | 501 (24.2) | 112 (24.3) | <0.0001 |

| Couldn't get groceries or meals delivered to me | N/A | 1003 (8.0) | 210 (10.2) | 69 (15.0) | <0.0001 |

| The stores didn’t have the food I wanted | N/A | 6518 (52.0) | 399 (19.3) | 84 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

Analyses were conducted using frequencies and Wald’s chi-square statistical test, significance = 0.05.

1. Descriptive analyses were conducted before data imputation. Missing values are due to missed questions in the outcome variable (i.e., food security status).

2. Definitions include: food security (enough of the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); marginal food security (enough, but not always the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); low food security (sometimes not enough to eat); very low food security (often not enough to eat).

3. These variables were combined in subsequent analyses to indicate “not working”.

4. Unknown responses indicate the survey respondent left the response for that question blank on the survey.

5. Respondents who answered “yes” to working for pay received the question asking for the type of work. Respondents who answered “no” to working for pay received the question asking for the main source for not working.

6. This question was only asked for people who responded that they did work for pay in the previous question.

7. This question was only asked for people who responded that they did not work for pay in the previous question.

8. This question was “select all that apply” and proportions may equal greater than 100% indicating multiple responses were selected.

9. This question was not asked in Phase 1 of the survey.

10. This question was asked only of people who reported receiving a free meal or food within the last 7 days.

11. This question was asked only of people who indicated that the children in the household could not afford enough to eat.

12. This question was not asked of people who indicated food sufficiency in the last 7 days and based on the definition of “food secure” would not have values for this question.

The proportion of participants who experienced loss of employment or who were expecting loss of employment increased across food security levels with 75.8% of very low food secure people experiencing loss of employment compared to 33.5% of food secure people and 62.1% and 17.6% expecting loss of employment, respectively (Table 2). The proportion that experienced loss of employment increased as food security decreased. Of those who were employed, across all food security categories the majority worked in a private company followed by government or non-profit organization. The main reasons people who experienced low or very low food security did not work for pay or profit, aside from other unspecified reasons, were caring for children (10.7% and 10.8%, respectively), concern about spreading or contracting COVID-19 (11.9% and 13.0%, respectively), laid off due to the pandemic (12.6% and 10.8%, respectively), or their employer temporarily closed due to the pandemic (10.6% and 9.5%, respectively). These relationships were consistent across phases (data not shown).

The proportion of people receiving SNAP benefits in low and very low food secure people was low with 35.0% and 41.7%, respectively receiving these benefits. Across all food security categories, the majority of participants reported fewer trips to the grocery store due to the pandemic and the majority across food security categories also reported not receiving a free meal or food in the last 7 days. Even still, almost one-fifth of low (16.5%) and very low food secure (18.0%) people reported receiving a free meal or food from a variety of sources. The majority of low and very low food secure people reported that it was sometimes or often true that their children were not eating enough because they could not afford food (61.6% and 71.2%, respectively) with the most common reasons being that they could not afford or were afraid to go out to buy more food.

3.2. Adjusted Models

In adjusted models, those aged 40–49 had 1.54 (1.31, 1.82) times the odds of food insecurity compared to those aged 18–29; those who were Hispanic had 1.62 (1.44, 1.82) times the odds of food insecurity compared to non-Hispanic people; and, being Black or a combination of races put people at higher odds of food insecurity compared to White people (2.26 and 2.38, respectively). Additionally, participants who had education less than or some high school had 7.96 (6.37, 9.94) times the odds of food insecurity compared to those who had a graduate degree after adjusting for other predictors. Being widowed, divorced, separated or never married, or divorced resulted in increased odds of food insecurity than those who were married. Living in a household with 5 or 6 or more individuals was associated with increased odds of food insecurity (OR = 1.20 and 1.86, respectively). Those who were not working for pay or profit had 2.53 times the odds of food insecurity compared to those working for pay or profit after adjusting for all other predictors (p-value < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted associations of determinants of food insecurity (binary and categorical) for a sample of survey respondents in Massachusetts to the Census Household Pulse Survey, March 2020 – March 2021 (n = 57,678)1.

|

Binary Food Insecurity Adjusted Odds Ratio3 (95% CI) p-value |

Categorical Food Insecurity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Marginal Food Security2 Adjusted Odds Ratio3 (95% CI) p-value |

Low Food Security2 Adjusted Odds Ratio3 (95% CI) p-value |

Very Low Food Security2 Adjusted Odds Ratio3 (95% CI) p-value |

||

| Age Categories | ||||

| 18–29 (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 30–39 | 1.46 (1.24, 1.72) <0.0001 |

1.85 (1.31, 2.62) 0.0005 |

1.53 (1.28, 1.83) <0.0001 |

1.22 (1.11, 1.33) <0.0001 |

| 40–49 | 1.54 (1.31, 1.82) <0.0001 |

1.92 (1.34, 2.76) 0.0004 |

1.58 (1.31, 1.90) <0.0001 |

1.15 (1.05, 1.27) 0.0030 |

| 50–59 | 1.21 (1.02, 1.45) 0.0297 |

1.45 (0.99, 2.13) 0.0548 |

1.21 (0.99, 1.46) 0.0582 |

1.07 (0.97, 1.17) 0.1816 |

| 60–69 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) 0.0032 |

0.63 (0.40, 0.97) 0.0371 |

0.75 (0.61, 0.93) 0.0077 |

0.92 (0.83, 1.02) 0.1128 |

| 70+ | 0.26 (0.20, 0.33) <0.0001 |

0.21 (0.12, 0.37) <0.0001 |

0.23 (0.17, 0.30) <0.0001 |

0.64 (0.57, 0.72) <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| Female | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) 0.0625 |

0.92 (0.76, 1.12) 0.4277 |

0.96 (0.87, 1.06) 0.3841 |

1.10 (1.05, 1.15) <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity4 | ||||

| No, not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| Yes, of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 1.62 (1.44, 1.82) <0.0001 |

2.01 (1.57, 2.57) <0.0001 |

1.83 (1.61, 2.09) <0.0001 |

1.36 (1.26, 1.47) <0.0001 |

| Race4 | ||||

| White, alone (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| Black, alone | 2.26 (1.99, 2.58) <0.0001 |

1.78 (1.30, 2.43) 0.0003 |

3.04 (2.64, 3.52) <0.0001 |

1.66 (1.51,1.81) <0.0001 |

| Asian, alone | 1.16 (0.94, 1.43) 0.1603 |

1.00 (0.60, 1.67) 0.9987 |

1.38 (1.10, 1.73) 0.0054 |

1.38 (1.27, 1.52) <0.0001 |

| Any other or combination | 2.38 (2.04, 2.77) <0.0001 |

2.85 (2.10, 3.86) <0.0001 |

2.92 (2.46, 3.47) <0.0001 |

1.60 (1.43, 1.78) <0.0001 |

| Education Level4 | ||||

| Less than or some high school | 7.96 (6.37, 9.94) <0.0001 |

9.01 (5.70, 14.24) <0.0001 |

11.34 (8.79, 14.62) <0.0001 |

2.55 (2.17, 3.01) <0.0001 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 5.71 (4.85, 6.71) <0.0001 |

6.09 (4.27, 8.68) <0.0001 |

7.52 (6.27, 9.01) <0.0001 |

2.22 (2.05, 2.40) <0.0001 |

| Some college | 4.45 (3.82, 5.19) <0.0001 |

4.53 (3.22,6.37) <0.0001 |

6.00 (5.06, 7.12) <0.0001 |

2.29 (2.15, 2.44) <0.0001 |

| Associate’s degree | 4.77 (4.02,5.67) <0.0001 |

4.51 (3.05, 6.67) <0.0001 |

6.31 (5.21,7.64) <0.0001 |

2.14 (1.98, 2.32) <0.0001 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.82 (1.56, 2.13) <0.0001 |

1.45 (1.01, 2.09) 0.0433 |

2.03 (1.71, 2.42) <0.0001 |

1.28 (1.21, 1.35) <0.0001 |

| Graduate degree (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| Marital Status4 | ||||

| Now married (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| Widowed | 2.28 (1.82, 2.86) <0.0001 |

4.18 (2.61, 6.69) <0.0001 |

2.26 (1.75, 2.92) <0.0001 |

1.33 (1.19, 1.48) <0.0001 |

| Divorced | 2.85 (2.51, 3.23) <0.0001 |

4.25 (3.15, 5.73) <0.0001 |

3.31 (2.88, 3.80) <0.0001 |

1.66 (1.55, 1.77) <0.0001 |

| Separated | 3.71 (3.02, 4.56) <0.0001 |

7.64 (5.05, 11.57) <0.0001 |

4.40 (3.46, 5.60) <0.0001 |

1.94 (1.68, 2.25) <0.0001 |

| Never married | 2.40 (2.13, 2.71) <0.0001 |

4.03 (3.06, 5.30) <0.0001 |

2.44 (2.14, 2.78) <0.0001 |

1.31 (1.23, 1.39) <0.0001 |

| Household Size | ||||

| 1 person household (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 2 person household | 0.88 (0.77, 1.00) 0.0513 |

0.62 (0.46, 0.83) 0.0012 |

0.96 (0.83, 1.11) 0.5806 |

1.00 (0.93, 1.07) 0.9908 |

| 3 person household | 1.05 (0.91,1.21) 0.5285 |

0.95 (0.70, 1.29) 0.7439 |

1.17 (0.997, 1.38) 0.0551 |

1.18 (1.09, 1.27) <0.0001 |

| 4 person household | 0.98 (0.84, 1.14) 0.7743 |

0.91 (0.65, 1.26) 0.5578 |

1.06 (0.89, 1.26) 0.5342 |

1.10 (1.02, 1.20) 0.0205 |

| 5 person household | 1.20 (1.00, 1.44) 0.0462 |

1.22 (0.83, 1.78) 0.3205 |

1.37 (1.12, 1.68) 0.0025 |

1.28 (1.16, 1.41) <0.0001 |

| 6 + person household | 1.86 (1.54, 2.24) <0.0001 |

2.27 (1.56, 3.30) <0.0001 |

2.18 (1.76, 2.69) <0.0001 |

1.47 (1.31, 1.66) <0.0001 |

| Any work for pay/profit | ||||

| Yes (ref) | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| No | 2.53 (2.32, 2.77) <0.0001 |

4.59 (3.73, 5.65) <0.0001 |

2.75 (2.49, 3.04) <0.0001 |

1.58 (1.51, 1.66) <0.0001 |

Analyses were conducted using binomial and multinomial logistic regression, significance = 0.05.

1. Analyses were conducted after data imputation to account for missing values.

2. Definitions include: food security (enough of the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); marginal food security (enough, but not always the kinds of food I/we wanted to eat); low food security (sometimes not enough to eat); very low food security (often not enough to eat).

3. Adjusted analyses were controlled for the other variables in the table.

4. Categories were determined by the categories listed on the Census Pulse Household Survey.

Categorical food security increased with certain determinants. Those who were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish race consistently had increased odds of having marginal food security (OR = 2.01, p-value < 0.0001), low food security (OR = 1.83, p-value < 0.0001) or very low food security (OR = 1.36, p-value < 0.0001) after adjusting for other predictors (p-value < 0.0001). While the odds of food insecurity did not increase consistently across levels, being Black or a combination of races put people at significantly higher odds of food insecurity (OR = 2.26, p-value < 0.0001 and OR = 2.38, p-value < 0.0001, respectively) and across all categories compared to Whites after adjusting for all other predictors. In addition, lower education levels resulted in greater odds of low food security than higher education levels (Table 3).

Those who were not working for pay/profit had significantly increased odds of having marginal food security (OR = 4.59, p-value < 0.0001), having low food security (OR = 2.75, p-value < 0.0001) and having very low food security (OR = 1.58, p-value < 0.0001) after adjusting for all other predictors (OR = 4.59, 2.75, and 1.58, respectively) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

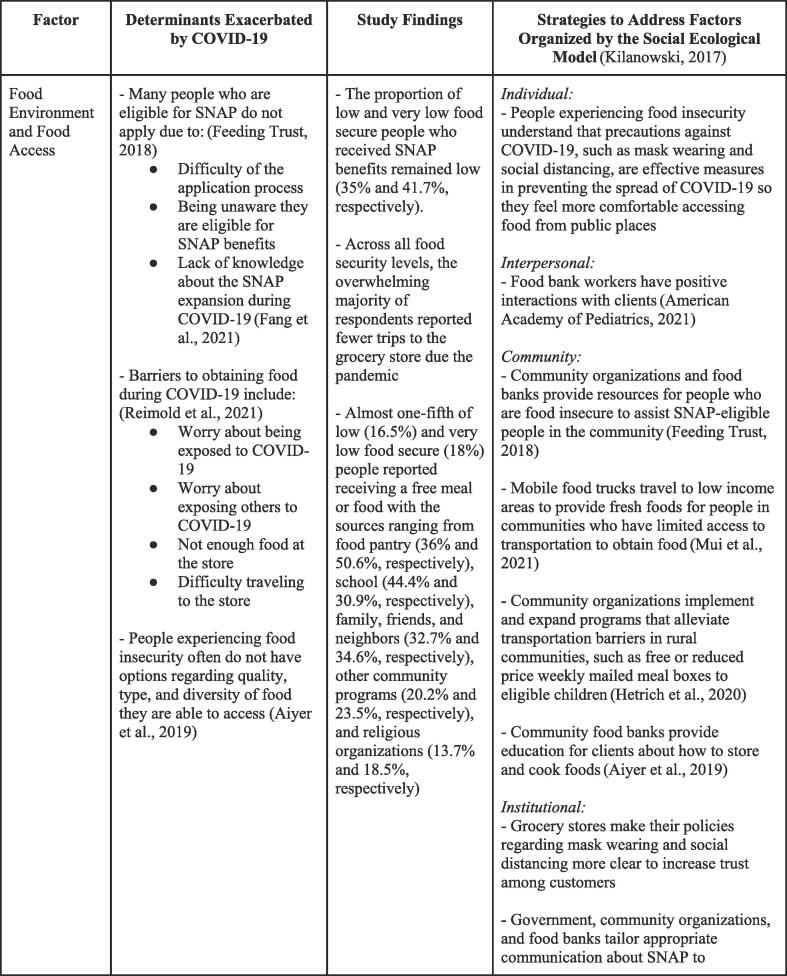

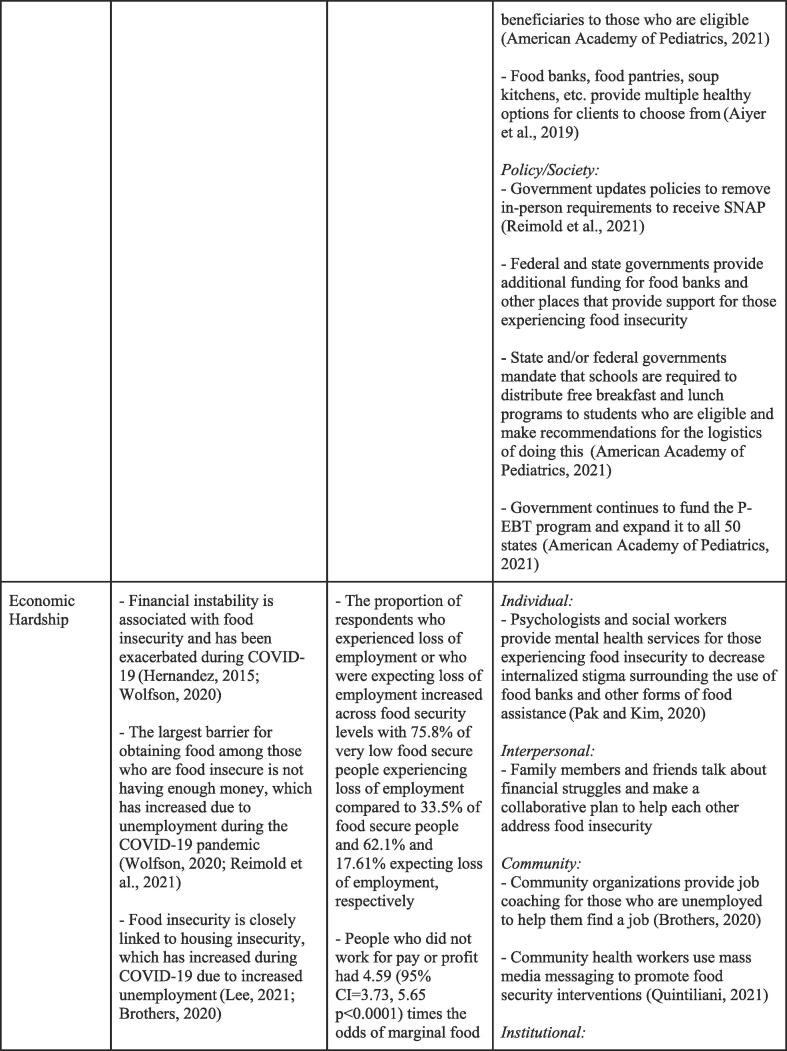

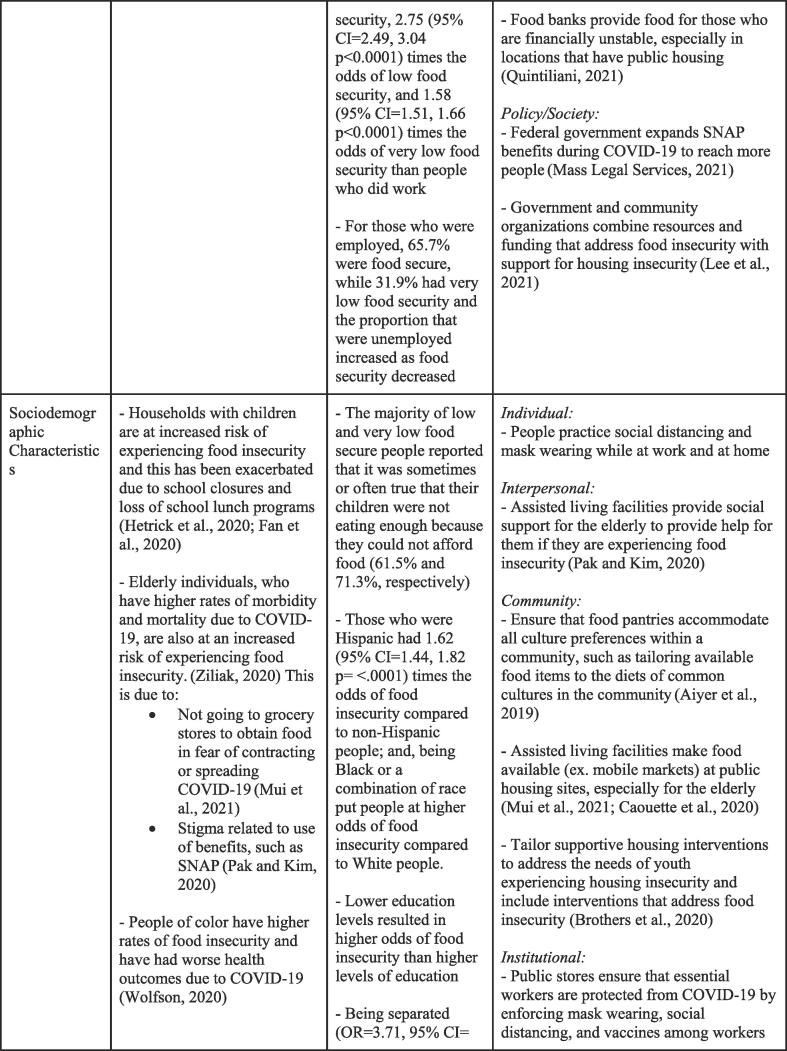

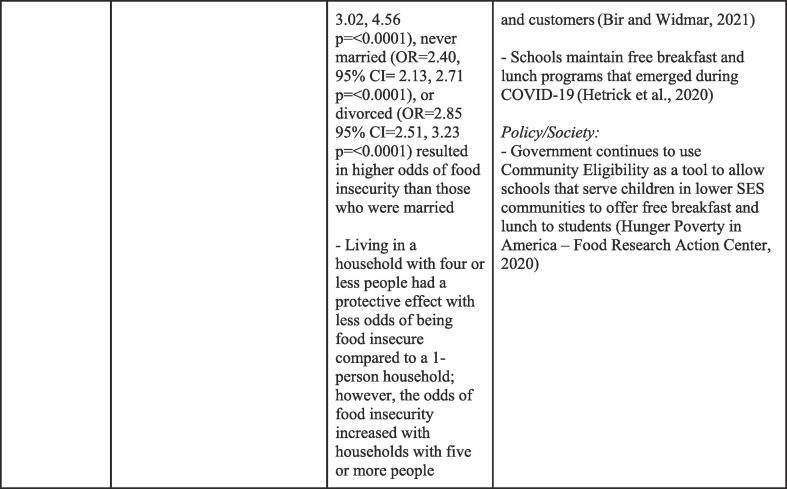

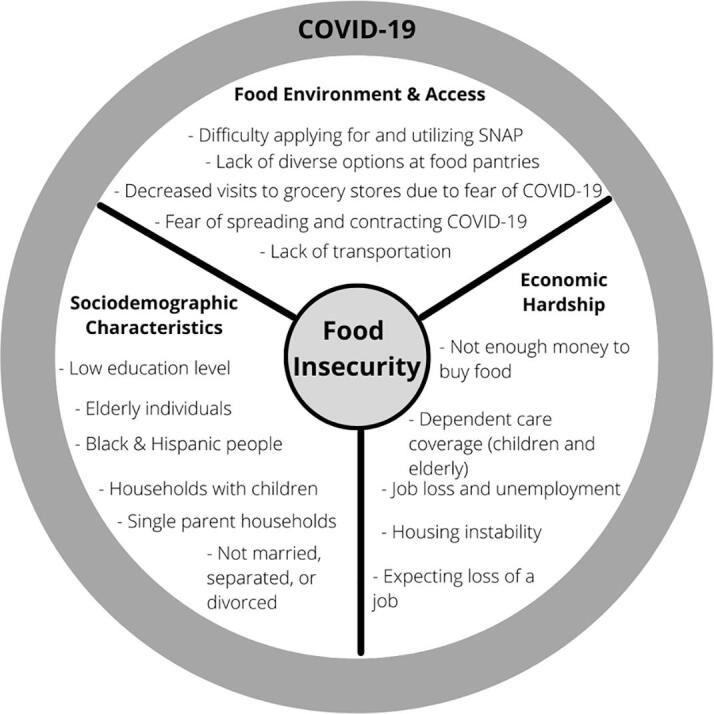

Understanding the determinants of food insecurity is essential for creating better policies and programs, especially as the pandemic progresses and its long-term impacts are realized. Determinants affecting food insecurity during COVID-19 occur at all levels of the social ecological model (SEM) and can be organized by broader factors including food environment and access, economic hardship, and sociodemographic characteristics. (Kilanowski, 2017) This study aims to 1) understand some of the most immediate determinants within these factors, and 2) highlight best practices for intervention at all levels of the SEM and within the context of COVID-19 (Fig. 1), guided by these findings and evidence in the field. The importance of this is paramount given 4.4% of people in Massachusetts were food insecure in this study with recent projections indicating even larger proportions of food insecure people in Massachusetts (9.9%). (Little and Rubin, 2002).

Fig. 1.

Determinants influencing food insecurity during COVID-19 organized by food environment & access, economic hardship, and sociodemographic characteristics.

During the pandemic, there have been barriers to accessing food and challenges with applying for and receiving SNAP benefits. (Feeding America, 2021) Consistent with the literature, this study found that during the first year of the pandemic, there was a proportion of those who had low or very low food security who were receiving SNAP benefits remained low (35% and 41.7%, respectively). While services exist, there is a need to promote existing services, such as SNAP, at the local and national level through more targeted and tailored communication about SNAP benefits to those eligible to increase utilization (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example strategies by level of the Social Ecological Model to address factors and determinants of food insecurity exacerbated during COVID-19.

To further promote food access and alleviate transportation barriers, community organizations can deliver meals directly to or near people’s homes (ex. mobile markets and home food delivery programs). (Food Trust, 2019) The successful government-funded program, Pandemic-Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT), allows states to provide funds directly to households with children who lost access to school lunch programs during COVID-19 to reduce food insecurity and improve nutritional uptake in children. (Mui et al., 2022) While invaluable, many food banks do not provide culturally-relevant food options for clients. Effective community-based strategies to improve resources and support for food pantry clients include increasing the diversity of available foods and providing education about storage and preparation (Fig. 2). (Hetrick et al., 2020) Future studies should explore transportation barriers and the impact on accessing food, particularly as access to and comfort with public transportation may change with the pandemic (Aiyer et al., 2019).

In our study, people experiencing economic hardship during COVID-19, such as loss of employment, were more likely to experience very low food security. This finding is consistent with other literature, which shows that prior to the pandemic, financial instability was associated with food insecurity and that during the pandemic, food insecurity increased due to higher rates of unemployment. (Hernandez, 2015, Wolfson and Leung, 2020) This study also found that not having enough money and being afraid to go out to buy food are often reported as the primary reasons people experience food insecurity (Table 2) (Aiyer et al., 2019). Other factors related to economic hardship include housing instability, transportation barriers, job loss, and unemployment (Decker and Flynn, 2018, Reimold et al., 2021). While not exhaustive, some example strategies to address economic hardship include job coaching for those who are unemployed, increasing food access at public housing sites, addressing food insecurity and housing instability together, and expanding SNAP benefits (Fig. 2) (Lee et al., 2021, Reimold et al., 2021, Quintiliani et al, Mass Legal Services. It’s time to FINALLY close the Massachusetts “SNAP Gap” and expand Common Apps in, 2021).

Households with children, youth, elderly people, people with disabilities, and people of color are more likely to experience food insecurity than those who do not belong to those groups (Brothers et al., 2020, Fan et al., 2021, Wolfson and Leung, 2020, Hernandez, 2015, Mass Legal Services. It’s time to FINALLY close the Massachusetts “SNAP Gap” and expand Common Apps in, 2021). In this study, living in a household with five or more people, being Black, having a lower education level, or being unmarried were sociodemographic determinants impacting food insecurity (Table 3). Many people who are in these demographic groups experienced worse impacts from COVID-19. (Wolfson and Leung, 2020) Some strategies to address these determinants include food pantries providing culturally appropriate food and services and addressing the needs of youth experiencing housing and food insecurity (Mass Legal Services, 2021). This study found that caring for children was one of the major reasons why people experiencing very low food security were unable to work during COVID-19 (10.8%), compared to those who were food secure (4.4%) (Table 2). When physicians screen their patients for food insecurity, they should also inquire about childcare needs and connect parents to services that can help address the barriers to affordable childcare. (Ziliak, 2021) Schools should also maintain free breakfast and lunch programs that may have been interrupted due to COVID-19 to ensure that children who receive food from school do not lose those meals (Fig. 2) (Ziliak, 2021, Aiyer et al., 20192019, Mass Legal Services. It’s time to FINALLY close the Massachusetts “SNAP Gap” and expand Common Apps in, 2021). For elderly people who may experience mobility issues that impact their ability to go to grocery stores or carry groceries back to their homes, home delivery meal programs are an effective intervention (Fig. 2) (Food Trust, 2019).

Determinants can be addressed through intervention including individualized programs, community-based efforts, and national policies. Some of these services are already in place, but a more thorough understanding of the context resulting from the pandemic will allow interventions to promote maximum utilization, to be tailored to meet the needs of the most vulnerable populations, and to successfully expand to other areas that can benefit from these approaches. Evidence-informed strategies focused on one or more levels of the SEM (Fig. 2) to address the myriad of factors of food insecurity will achieve the most advantageous outcomes.

This study illustrates that there is still an ongoing and urgent need to address food insecurity in normal and emergency situations, such as COVID-19. Understanding the factors affecting this issue – whether through new studies or examination of ongoing surveys and surveillance – is essential to finding solutions through comprehensive and sustainable approaches. While this paper highlights some examples of those strategies, there are many others that should be explored with the understanding of the new context resulting from the pandemic. As public health responds to food insecurity during and in the aftermath of the pandemic, it is critical to create interventions that target populations most at risk and that address multiple levels of the SEM due to the interconnected individual and environmental determinants of food insecurity.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Eva Nelson, Email: ehnelson@bu.edu.

Candice Bangham, Email: cbangham@bu.edu.

Shagun Modi, Email: shagunm@bu.edu.

Xinyang Liu, Email: xinyangl@bu.edu.

Alyson Codner, Email: codnera@bu.edu.

Jacqueline Milton Hicks, Email: jnmilton@bu.edu.

Jacey Greece, Email: jabloom@bu.edu.

References

- USDA. Food Insecurity: Key Statistics and Graphs.; 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx.

- Clay L., Papas M., Gill K., Abramson D. Factors Associated with Continued Food Insecurity among Households Recovering from Hurricane Katrina. IJERPH. 2018;15(8):1647. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory C, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020.; 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298_summary.pdf?v=3911.8.

- Savoie-Roskos M., Durward C., Jeweks M., LeBlanc H. Reducing Food Insecurity and Improving Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Farmers’ Market Incentive Program Participants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2016;48(1):70–76.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA. Food Insecurity Measurement.; 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx#measurement.

- Hernandez D. The impact of cumulative family risks on various levels of food insecurity. 2015;50:292-302. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049089X14002312. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Decker D., Flynn M. Published online; RIMJ: 2018. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease: Addressing Food Access as a Healthcare Issue. http://www.rimed.org/rimedicaljournal/2018/05/2018-05-28-cont-decker.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunger & Poverty in America - Food Research & Action Center. Published 2020. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://frac.org/hunger-poverty-america.

- Kilanowski J.F. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. Journal of Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):295–297. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2017.1358971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Leung C.W. Food Insecurity During COVID-19: An Acute Crisis With Long-Term Health Implications. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(12):1763–1765. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics The Employment Situation - November 2021 2021 U.S Department of Labor https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

- Clay L.A., Ross A.D. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity Following Hurricane Harvey in Texas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(3):762. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA ERS - SNAP Online. Published 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2021/july/online-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap-purchasing-grew-substantially-in-2020/.

- Fan L., Gundersen C., Baylis K., Saksena M. The Use of Charitable Food Assistance Among Low-Income Households in the United States. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2021;121(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. A Closer Look at Who Benefits from SNAP: State-by-State Fact Sheets. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-closer-look-at-who-benefits-from-snap-state-by-state-fact-sheets#Massachusetts.

- Bureau UC. Access and Eligibility for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Varies County by County. Census.gov. Published 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/02/demographic-snapshot-not-everyone-eligible-for-food-assistance-program-receives-benefits.html.

- Bureau UC. Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Census.gov. Published 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/householdpulsedata.

- Ohri-Vachaspati P., Acciai F., DeWeese R.S. SNAP participation among low-income US households stays stagnant while food insecurity escalates in the months following the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Insecurity Remains Well Above Pre-Pandemic Levels. The Greater Boston Food Bank. Published April 1, 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.gbfb.org/2021/04/01/food-insecurity-remains-well-above-pre-pandemic-levels/.

- Bureau UC. Household Pulse Survey Data Tables. Census.gov. Published 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html.

- Makelarski J.A., Abramsohn E., Benjamin J.H., Du S., Lindau S.T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Two Food Insecurity Screeners Recommended for Use in Health Care Settings. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1812–1817. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey Published 2021 https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/Phase_3-2_Household_Pulse_Survey_FINAL_English_SKIPS_081821.pdf.

- Fields JF, Hunter-Childs J, Tersine A, Sisson J, Parker E, Velkoff V, Logan C, and Shin H. Design and Operation of the Household Pulse Survey, 2020 2020 U.S Census Bureau.

- Allison, Statistics and Data Analysis; SAS Global Forum: 2012. Handling Missing Data by Maximum Likelihood. [Google Scholar]

- Allison (2005). Imputation of Categorical Variables with PROC MI. SUGI 30 Proceedings – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania April 10-13, 2005.

- Enders, The Guilford Press; 2010. Applied Missing Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Single Imputation Methods. In: Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2002:59-74. doi:10.1002/9781119013563.ch4.

- 29.America. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Food Trust 2019 http://thefoodtrust.org/uploads/media_items/closing-the-houston-snap-gap.original.pdf.

- Mui Y., Headrick G., Raja S., Palmer A., Ehsani J., Pollack Porter K. Acquisition, mobility and food insecurity: integrated food systems opportunities across urbanicity levels highlighted by COVID-19. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25(1):114–118. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick R.L., Rodrigo O.D., Bocchini C.E. Addressing Pandemic-Intensified Food Insecurity. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J.N. Aiyer M. Raber R.S. Bello A. Brewster E. Caballero C. Chennisi C. Durand M. Galindez K. Oestman M. Saifuddin J. Tektiridis R. Young S.V. Sharma A pilot food prescription program promotes produce intake and decreases food insecurity Transl Behav Med. 9 5 2019 2019 922 930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reimold A.E., Grummon A.H., Taillie L.S., Brewer N.T., Rimm E.B., Hall M.G. Barriers and facilitators to achieving food security during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.Y., Zhao X., Reesor-Oyer L., Cepni A.B., Hernandez D.C. Bidirectional Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Housing Instability. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2021;121(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L.M. Quintiliani J.A. Whiteley J. Zhu E.K. Quinn J. Murillo R. Lara J. Kane Examination of Food Insecurity, Socio-Demographic, Psychosocial, and Physical Factors among Residents in Public Housing Ethn Dis 31 1 159 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mass Legal Services. It’s time to FINALLY close the Massachusetts “SNAP Gap” and expand Common Apps in 2021 ! | Mass Legal Services. Published 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.masslegalservices.org/content/its-time-finally-close-massachusetts-snap-gap-and-expand-common-apps-2021.

- Brothers S., Lin J., Schonberg J., Drew C., Auerswald C. Food insecurity among formerly homeless youth in supportive housing: A social-ecological analysis of a structural intervention. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;245 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziliak J.P. Food Hardship during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Great Recession. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2021;43(1):132–152. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

Further reading

- Bir C., Widmar N.O. Societal values and mask usage for COVID-19 control in the US. Prev Med. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mass.gov. COVID-19 Community Impact Survey. https://www.mass.gov/info-details/covid-19-community-impact-survey.

- Screen and Intervene: A Toolkit for Pediatricians to Address Food Insecurity. Food Research and Action Center; 2021. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/FRAC_AAP_Toolkit_2021.pdf.

- Fang D.i., Thomsen M.R., Nayga R.M., Yang W. Food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a survey of low-income Americans. Food Sec. 2022;14(1):165–183. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak T.-Y., Kim G. Food stamps, food insecurity, and health outcomes among elderly Americans. Preventive Medicine. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauouette S., Boss L., Lynn M. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. AJN. 2020;120(6):24–36. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000668732.28490.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]