Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that haloperidol biotransformation occurs with participation of the CYP2D6 isoenzyme. The CYP2D6 gene is highly polymorphic, which may contribute to differences in its activity and in the haloperidol biotransformation rates across different individuals, resulting in variable drug efficacy and safety profiles.

Purpose

The study aimed to investigate the correlation of the 1846G> A polymorphism of CYP2D6 gene with the efficacy and safety rates of haloperidol in patients with alcoholic hallucinoses.

Material and methods

One hundred male patients received 5–10 mg/day haloperidol by injections for 5 days. The efficacy and safety assessments were performed using the validated psychometric scales PANSS, UKU, and SAS. For genotyping, the real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed.

Results

We revealed no statistically significant results in terms of haloperidol efficacy in patients with different genotypes (dynamics of the PANSS scores: (GG) −13.00 [−16.00; −11.00], (GA) −15.00 [−16.75; −13.00], p = 0,728). Our findings revealed the statistically significant results in terms of treatment safety evaluation (dynamics of the UKU scores: (GG) 8.00 [7.00; 10.00], (GA) 15.0 [9.25; 18.0], p < 0.001; dynamics of the SAS scores: (GG) 11.0 [9.0; 14.0], (GA) 14.50 [12.0; 18.0], p < 0.001.

Conclusion

These results suggest that genotyping for common CYP3A variants might have the potential to guide benzodiazepine withdrawal treatment. The effect of of the 1846G>A polymorphism of CYP2D6 gene on the safety profile of haloperidol was demonstrated in a group of 100 patients with alcoholic hallucinoses.

Keywords: CYP2D6, pharmacogenetics, personalized medicine, alcoholic hallucinosis, haloperidol

Introduction

Alcoholic hallucinosis is a complication of chronic alcohol abuse characterized by an acute onset of auditory and/or visual hallucinations that occur either during or after a period of heavy alcohol consumption.1 Typically, it presents with acoustic verbal hallucinations, delusions, and mood disturbances arising in clear consciousness.2 Prevalence estimates from 0.4% to 12% have been reported in various studies.3 As a result, globally alcoholic hallucinosis is considered either a rare or an underdiagnosed condition.4 Alcoholic hallucinosis develops acutely, usually after a period of abstinence lasting from a few hours to a week or longer—in most cases, within two days following the last drink. In contrast to delirium tremens, the preceding drinking spree can at times be much shorter, sometimes no longer than a week.5

Due to the vivid psychotic symptoms, in-patient treatment of alcoholic hallucinosis is usually required. Treatment with antipsychotics is generally necessary, sometimes combined with tranquilizers. Usually, haloperidol is administered in a dose of 5–10 mg per day.6

Haloperidol is a high potency first-generation (typical) antipsychotic and one of the most frequently used antipsychotic medications used worldwide.7 Being a typical antipsychotic, haloperidol exerts its action predominantly through the strong dopamine D2 receptor antagonism, particularly within the mesolimbic and mesocortical systems of the brain. Haloperidol improves psychotic symptoms and states that are caused by an over-production of dopamine.8 However, it should be noted that haloperidol, like all antipsychotics, frequently causes extrapyramidal motor disorders due to the striatal D2 receptor blockade, which disrupts the effective treatment and reduces safety of the therapy. Major extrapyramidal adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with the use of haloperidol include Parkinsonian symptoms, akathisia, and dystonia.9 It also possesses noradrenergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic blocking action which is associated with various ADRs.10

Haloperidol undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver with less than 1% of the parent drug excreted in urine.11 The genetically polymorphic enzyme cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 contributes to the biotransformation of haloperidol.12 The human CYP2D6 gene belongs to chromosome 22q13.1 and contains 12 exons. It is highly polymorphic—to date, more than 100 allelic variants and many sub-variants of the CYP2D6 gene have been reported.13 Although CYP2D6 is only 2–4% of the total CYP content in the liver,14 it is responsible for the metabolism of at least 25–30% of currently approved pharmaceuticals.15

A single nucleotide polymorphism (rs3892097; 1846G >A) in the CYP2D6 gene results in a functionally deficient variant of the enzyme (the so-called CYP2D6*4 isoform). Currently, it is believed that this is a frequent CYP2D6 variant leading to a deficiency in enzyme activity and it is believed to result in a poor metabolizer status.16

Categorization of the CYP2D6 metabolizer status is based on the assessment of CYP2D6 activity, which allows for determining the metabolizer type.17 Individuals are categorized into four phenotype groups, poor metabolizers (PMs), ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs), normal metabolizers (NMs, (formerly extensive metabolizers), and intermediate metabolizers (IMs).18 Currently available evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines for drugs affected by genetic variation use the categories listed to provide clinicians with guidance on specific drugs for adjusting doses or switching drugs that are expected to cause ADRs in patients with certain CYP2D6 metabolizer status.19

A study by Sychev et al. (2016) investigating the correlation between the CYP2D6 activity and the efficacy and safety rates of haloperidol in patients with alcohol use disorder revealed that carriers of the GA CYP2D6*4 genotype had higher SAS (Simpson-Angus Scale for Extrapyramidal Symptoms) and UKU (Udvald for Kliniske Undersogelser Side Effect Rating Scale) scores in comparison with the carriers of the GG genotype.20 In 2016, Šimić et al. described a case of a 66-year-old male Caucasian who received 1 mg of haloperidol orally and rapidly developed severe iatrogenic extrapyramidal symptoms. It was due to the introduction of ciprofloxacin which was a trigger for the development of ADR due to inhibition of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 poor metabolizer status of the patient.21 A manuscript by Kawanishi et al. (2002) describes a case of a 71-year-old-woman with treatment-resistant schizophrenia who underwent six hospitalizations. She received various antipsychotics (haloperidol up to 12 mg per day, chlorpromazine to 250 mg per day, levomepromazine to 75 mg per day, and thioridazine up to 30 mg per day) with no effect. A genetic study revealed CYP2D6 gene duplication resulting in excessive CYP2D6 activity which may have contributed to treatment resistance in this case.22 Thus, in general, recent studies show that personalized dose selection based on pharmacogenetic testing contributes to improving the efficacy and safety of therapy.23

The objective of our study was to evaluate the effect of 1846G>A polymorphism of the CYP2D6 gene on the efficacy and safety of haloperidol in patients with alcoholic hallucinoses.

Material and Methods

The study involved 100 hospitalized male patients (average age —41.40 ± 14.40 years) diagnosed with an alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations (F10.52, according to ICD-10). Haloperidol in injections at a dose of 5–10 mg/day was prescribed to this cohort of patients for 5 days for the treatment of acute hallucinatory symptoms. Haloperidol was administered upon the admission of a patient to the emergency department. In addition to haloperidol, all patients received minimal standard therapy for 5 days, which included infusions and ion-containing solutions, as well as vitamins (see Table 1). Prescriptions were made in accordance with the national clinical guidelines for the therapy of alcohol-induced psychotic disorder.

Table 1. Minimal Standard Therapy.

| Medications | Average daily dose |

| Sodium chloride solution 0.9% + potassium chloride 10% + magnesium sulfate 25% | 800 mL |

| Thiamine hydrochloride solution 5% | 100 mg |

| Pyridoxine hydrochloride solution 5% | 100 mg |

Biomaterial collection was performed on days 1 and 6 of treatment after haloperidol administration.

The inclusion criterion was the diagnosis of alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations (F10.52, according to ICD-10). Exclusion criteria were creatinine clearance values <50 mL/min, creatinine concentration in plasma >1.5 mg/dL (133 mmol/L), bodyweight less than 60 kg or greater than 100 kg, age of 75 years or more, presence of any other psychotropic medications in the treatment regimen, presence of chronic psychotic disorders, and presence of any contraindications for haloperidol use.

Each patient signed an informed consent to voluntarily participate in the study. The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Protocol No. 14 of October 27, 2020).

For genotyping, venous blood samples were collected into VACUETTE® (Greiner Bio-One, Austria) vacuum tubes on day 6 of haloperidol therapy. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs3892097 (CYP2D6*4) was analyzed by real-time PCR using “Dtlite” DNA amplifiers (DNA Technology, Moscow, Russia) on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time System with CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and the “SNP-screen” sets (Syntol, Moscow, Russia). In every set, two allele-specific hybridizations were used, which allowed simultaneous determination of both alleles of the respective SNP using two fluorescence channels.

To assess haloperidol efficacy, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used.24 The safety profile was evaluated using the UKU25 and SAS26 scales. Patients were examined on days 1 and 6 of haloperidol therapy.

Statistical analysis was performed in Statsoft Statistica v. 10.0 (Dell Statistica, Tulsa, OK, USA). The normality of sample distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test and was taken into account for selecting parametric or non-parametric tests. The differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (power above 80 %). Two samples of continuous independent data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-tests with further correction of the obtained p-value using the Benjamin-Hochberg test, due to the multiple comparison procedure. Research data are presented in the form of the median and interquartile range (Me [Q1; Q3]).

Results

The CYP2D6 genotyping by polymorphic marker 1846G>A (rs3892097) performed on 100 subjects revealed the following results. The number of patients carrying the GG genotype was 70 (70). The number of patients with the GA genotype was 30 (30%). There were no carriers of the AA genotype found.

Further study included a comparison of the therapy efficacy and safety rates in major allele carriers (main group) and minor allele carriers (comparison group).

The results of data analysis performed for psychometric assessments (PANSS) and side-effect rating scales (UKU and SAS) on days 1 and 6 in patients who received haloperidol can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Data from the Psychometric Assessments and Side-Effect Rating Scales in Patients who Received Haloperidol, on Days 1 and 6 of the Study.

| Scale | GG (N = 70) | GA (N = 30) | P* |

| Day 1 | |||

| PANSS | 14.50 [13.00; 18.00] | 16.00 [15.00; 18.00] | 0.017 |

| SAS | 0 [0; 0] | 0 [0; 0] | > 0.999 |

| UKU | 0 [0; 0] | 0 [0; 0] | > 0.999 |

| Day 6 | |||

| PANSS | 1.00 [1.00; 2.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 2.75] | 0.006 |

| SAS | 11.00 [9.00; 14.00] | 14.50 [12.00; 18.00] | < 0.001 |

| UKU | 8.00 [7.00; 10.00] | 15.00 [9.25; 18.00] | < 0.001 |

Note: p* – p-value obtained in Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction (based on the results of Mann-Whitney U test).

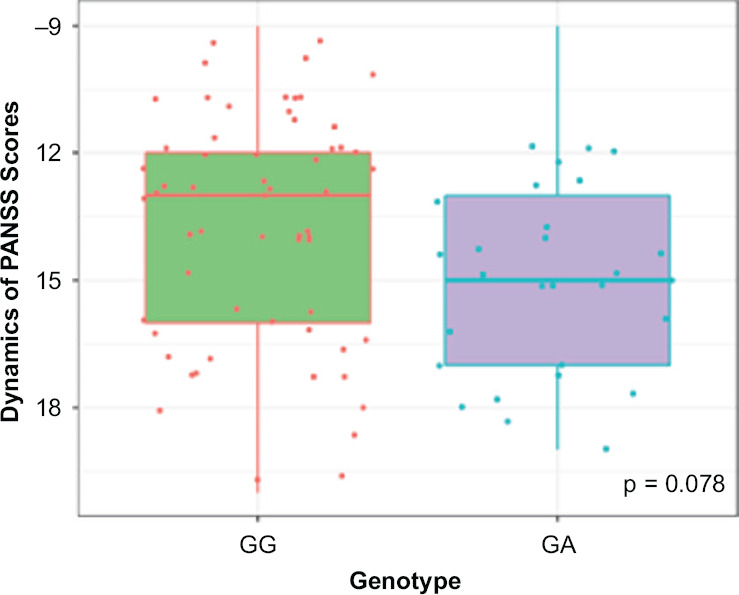

We compared the dynamics of changes in positive PANSS scale scores in patients with different genotypes (Figure 1). Statistical analysis of the clinical efficacy profile data obtained for the patients with different CYP2D6 genotypes by polymorphic marker 1846G>A (rs3892097) revealed no statistically significant differences: (GG) −13.00 [−16.00; −11.00], (GA) −15.00 [−16.75; −13.00], p = 0.078.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of Changes in Positive PANSS Scale Scores Across Patients with different CYP2D6 Genotypes by the Polymorphic Marker 1846G>A (rs3892097)

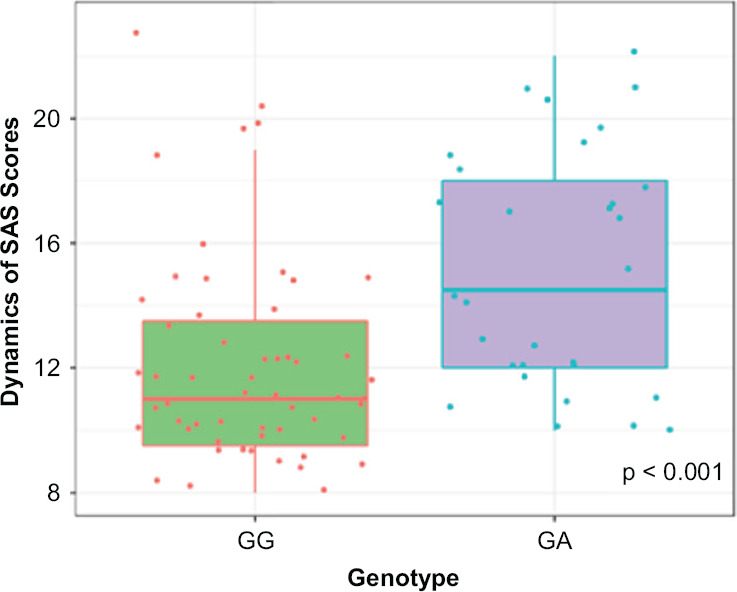

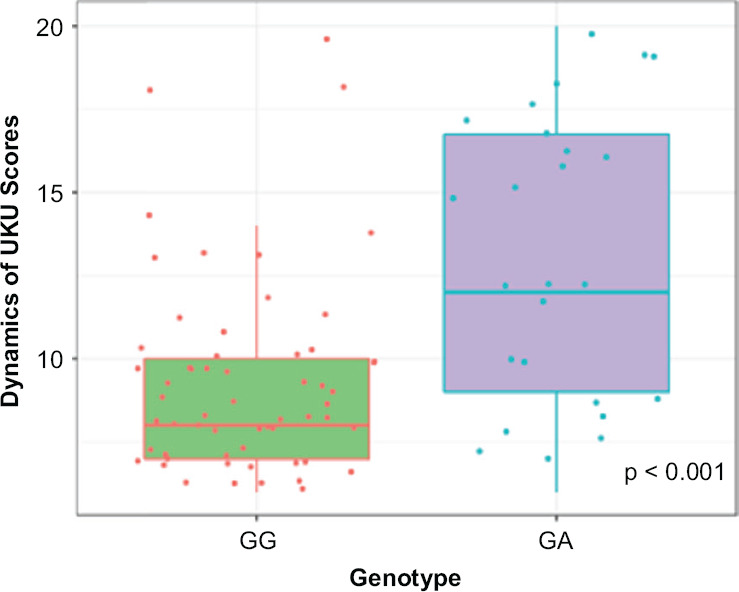

Figures 2–3 show the dynamics of changes in SAS and UKU scores in patients carrying different genotypes. Statistical analysis of the clinical safety profile data obtained for the patients with different CYP2D6 genotypes by polymorphic marker 1846G>A (rs3892097) revealed significant differences:

Figure 2.

Dynamics of Changes in SAS Scale Scores across Patients with Different CYP2D6 Genotypes by the Polymorphic Marker 1846G>A (rs3892097)

Figure 3.

Dynamics of Changes in UKU Scale Scores Across Patients with different CYP2D6 Genotypes by the Polymorphic Marker 1846G>A (rs3892097)

• in SAS scale scores: (GG) 11.00 [9.00; 14.00], (GA) 14.50 [12.00; 18.00], p < 0.001;

• in UKU scale scores: (GG) 8.00 [7.00; 10.00], (GA) 8.00 [7.00; 10.00], p < 0.001.

Therefore, the study revealed no statistically significant differences in the efficacy of haloperidol therapy in patients with acute alcoholic hallucinoses carrying different CYP2D6 genotypes by the polymorphic marker 1846G>A (rs3892097). Meanwhile, a statistically significant difference in safety profile (as assessed by the UKU and SAS scales) was found. The dynamics were more obvious in the group of patients with the GA genotype compared with the carriers of the GG genotype. This is probably due to the fact that patients with GA genotype have a lower rate of haloperidol biotransformation and elimination, which is most likely due to low CYP2D6 activity. This leads to a more pronounced suppression of dopamine receptors in the central nervous system and to an increased risk of dose-dependent ADRs and their pronounced manifestation (acute dystonia, dyskinesia).

Discussion

The obtained data coincide with the results of a previous study demonstrating an increase in the ADRs incidence in patients treated with haloperidol since therapy safety is higher in carriers of the GA genotype than in carriers of the GG genotype.27 Subsequently, after obtaining the results of therapeutic drug monitoring, we will be able to address the problem of the effects of CYP2D6 genetic polymorphisms on changes in haloperidol concentration more accurately and, accordingly, obtain information on the effect of the studied polymorphism on the efficacy and safety of haloperidol.

It is worth noting that our study had a number of limitations, namely: all patients were males; only 1846G>A polymorphism of the CYP2D6 gene was included in the study; there were no homozygous carriers of the minor allele revealed; we did not assess the steady-state concentration of haloperidol.

The results of our study should be taken into account when prescribing haloperidol to patients with alcoholic hallucinosis since it will increase the efficacy of haloperidol therapy and reduce the risk of ADRs. The starting dose of haloperidol should be reduced by 25% in patients with the GA genotype by polymorphic marker 1846G>A, and homozygous GG carriers should be prescribed haloperidol at a standard therapeutic dose. According to the existing DPWG guideline on haloperidol pharmacogenetics, a 50% reduction in the starting dose is recommended for mutant homozygotes.28 Our study revealed a deterioration in haloperidol safety profile in heterozygous patients. Therefore, adjustment of the haloperidol starting dose is needed. However, it is likely that dose correction should be not as pronounced as in the existing recommendations for homozygous patients.

Conclusion

Our study conducted on 100 patients with acute alcoholic hallucinoses demonstrated that CYP2D6 polymorphism may impair the safety of haloperidol therapy. This should be taken into account when administering haloperidol to such patients in order to reduce the risk of adverse reactions and pharmacoresistance.

Footnotes

Funding Information

This work was supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 22-15-00190, https://rscf.ru/project/22-15-00190/).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Contributor Information

AA Parkhomenko, Parkhomenko, Postgraduate student in the Department of Addiction Medicine, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

MS Zastrozhin, Zastrozhin, PhD, M.D., Postdoctoral Fellow, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA..

VYu Skryabin, Skryabin, PhD, M.D., head of clinical department, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia; Associate professor of addiction psychiatry department, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

VA Ivanchenko, Ivanchenko, laboratory assistant, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia..

SA Pozdniakov, Pozdniakov, researcher of the laboratory of genetics and fundamental studies, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia..

VV Noskov, Noskov, laboratory assistant, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia..

IA Zaytsev, Zaytsev, laboratory assistant, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia..

NP Denisenko, Denisenko, PhD in Medicine, Head of the Department of Personalized Medicine, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

KA Akmalova, Akmalova, Researcher in the Department of Molecular Medicine, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

EA Bryun, Bryun, PhD, M.D., professor, president, Moscow Research and Practical Centre on Addictions of the Moscow Department of Healthcare, Moscow, Russia; head of addiction psychiatry department, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

DA Sychev, Sychev, corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of Russia, M.D., PhD, professor, rector, head of clinical pharmacology and therapy department, Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia..

References

- 1.Perme B, Vijaysagar KJ, Chandrasekharan R. Follow-up study of alcoholic hallucinosis. Indian J Psychiatry . 2003;45:244–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhat PS, Ryali V, Srivastava K, Kumar SR, Prakash J, Singal A. Alcoholic hallucinosis. Ind Psychiatry J . 2012;21(2):155–157. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.119646. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordaan GP, Emsley R. Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder: A review. Metab Brain Dis . 2014;29(2):231–243. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9457-4. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narasimha VL, Patley R, Shukla L, Benegal V, Kandasamy A. Phenomenology and Course of Alcoholic Hallucinosis. J Dual Diagn . 2019;15(3):172–176. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2019.1619008. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surawicz FG. Alcoholic Hallucinosis: A Missed Diagnosis: Differential Diagnosis and Management. Can J Psychiatry . 1980;25(1):57–63. doi: 10.1177/070674378002500111. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Millas W, Haasen C. Treatment of alcohol hallucinosis with risperidone. Am J Addict . 2007;16(3):249–250. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375269. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dold M, Samara MT, Li C, Tardy M, Leucht S. Haloperidol versus first-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015;1:CD009831. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009831.pub2. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeman P, Kapur S. Schizophrenia: more dopamine, more D2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2000;97(14):7673–7675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohno Y, Kunisawa N, Shimizu S. Antipsychotic Treatment of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD): Management of Extrapyramidal Side Effects. Front Pharmacol . 2019;10:1045. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01045. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman S, Marwaha R. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Haloperidol. StatPearls [Internet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudo S, Ishizaki T. Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet . 1999;37(6):435–456. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937060-00001. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockmöller J, Kirchheiner J, Schmider J, Walter S, Sachse C, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Roots I. The impact of the CYP2D6 polymorphism on haloperidol pharmacokinetics and on the outcome of haloperidol treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther . 2002;72(4):438–452. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.127494. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopisankar MG. J. Med. Hum. Genet . 2017;18:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmhg.2017.03.001. CYP2D6 pharmacogenomics. Egypt. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, He MM, Liu H, Wrighton SA, Wang L, Guo B, Li C. Comparative metabolic capabilities and inhibitory profiles of CYP2D6.1, CYP2D6.10, and CYP2D6.17. Drug Metab Dispos . 2007;35(8):1292–1300. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015354. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams IS, Gatchie L, Bharate SB, Chaudhuri B. Biotransformation, Using Recombinant CYP450-Expressing Baker’s Yeast Cells, Identifies a Novel CYP2D6.10A122V Variant Which Is a Superior Metabolizer of Codeine to Morphine Than the Wild-Type Enzyme. ACS Omega . 2018;3(8):8903–8912. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00809. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anwarullah, Aslam M, Badshah M, Abbasi R, Sultan A, Khan K, Ahmad N, von Engelhardt J. Further evidence for the association of CYP2D6*4 gene polymorphism with Parkinson’s disease: a case control study. Genes Environ . 2017;39:18. doi: 10.1186/s41021-017-0078-8. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nofziger C, Turner AJ, Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, Agúndez JAG, Black JL, Dunnenberger HM, Ruano G, Kennedy MA, Phillips MS, Hachad H, Klein TE, Gaedigk A. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2D6. Clin Pharmacol Ther . 2020;107(1):154–170. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1643. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caudle KE, Dunnenberger HM, Freimuth RR, Peterson JF, Burlison JD, Whirl-Carrillo M, Scott SA, Rehm HL, Williams MS, Klein TE, Relling MV, Hoffman JM. Standardizing terms for clinical pharmacogenetic test results: consensus terms from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Genet Med . 2017;19(2):215–223. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.87. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor C, Crosby I, Yip V, Maguire P, Pirmohamed M, Turner RM. A Review of the Important Role of CYP2D6 in Pharmacogenomics. Genes (Basel) . 2020;11(11):1295. doi: 10.3390/genes11111295. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sychev DA, Zastrozhin MS, Smirnov VV, Grishina EA, Savchenko LM, Bryun EA. The correlation between CYP2D6 isoenzyme activity and haloperidol efficacy and safety profile in patients with alcohol addiction during the exacerbation of the addiction. Pharmgenomics Pers Med . 2016;9:89–95. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S110385. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Šimić I, Potočnjak I, Kraljičković I, Stanić Benić M, Čegec I, Juričić Nahal D, Ganoci L, Božina N. CYP2D6 *6/*6 genotype and drug interactions as cause of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms. Pharmacogenomics . 2016;17(13):1385–1389. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0069. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawanishi C, Furuno T, Kishida I, Matsumura T, Kosaka K. A patient with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and cytochrome P4502D6 gene duplication. Clin Genet . 2002;61(2):152–154. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610211.x. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Westrhenen R, Aitchison KJ, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Jukić MM. Pharmacogenomics of Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Treatment: How Far Have We Got and Where Are We Going. Front Psychiatry . 2020;11:94. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00094. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull . 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl . 1987;334:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl . 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zastrozhin MS, Ryzhikova KA, Avdeeva ON, Sozaeva ZA, Grishina EA, Sychev DA, Savchenko LM, Guschina YS, Lepakhin VK. Relationship between polymorphism of the CYP2D6 gene and efficacy and safety profile of haloperidol in patients with alcohol addiction. 2016;2(58):41–44. Journal of Volgograd State Medical University. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annotation of DPWG Guideline for haloperidol and CYP2D6. Available at: https://api.pharmgkb.org/v1/download/file/attachment/DPWG_May_2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]