Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous nanometer-ranged particles that are released by cells under both normal and pathological conditions. EV cargo comprises of DNA, protein, lipids cargo, metabolites, mRNA, and non-coding RNA that can modulate the immune system by altering inflammatory response. EV associated miRNAs contribute to the pathobiology of alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, acetaminophen-induced liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In context of liver diseases, EVs, via their cargo, alter the inflammatory response by communicating with different cell types within the liver and between liver and other organs. Here, the role of EVs and its associated miRNA in inter-cellular communication in different liver disease and as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target is reviewed.

Keywords: biomarkers, exosomes, extracellular vesicles, inflammation, liver damage, microRNA

1|. INTRODUCTION

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous membranous vesicles that are produced by most of the cell types in both steady state and in diseased conditions. EVs is a broad term used to describe different sized vesicles including exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, which are released by donor cells through distinct biogenesis pathways.1 Exosomes are small particles and range from 30 to 100 nm and are the most well-studied and characterized subpopulation of EVs; in comparison, microvesicles range in size from 100 to 1000 nm.2

Exosomes originate as inter-luminal vesicles (ILVs) that are formed by the inward budding of the early endosomal membranes.3,4. When early endosomes comprising of ILVs mature to late endosomes, they are multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These MVBs are either recycled and degraded by lysosomes or transported to the plasma membrane where they fuse with the membrane and release their contents into the extracellular milieu. This process of releasing exosome content is well orchestrated and requires proteins involved in vesicular trafficking (i.e., Rab5, RAB27a, RAB27b, and RAB35) and cytoskeleton dynamics (i.e., cortactin, actin-related protein complex).

In contrast, microvesicles are formed by the outward budding of the plasma membrane.5 Although little is known about the mechanism of microvesicle biogenesis, several studies have highlighted the crucial role of plasma membrane curvature in the release of microvesicles.5 In addition, key cytoskeletal proteins (including those involved in the Rho signaling pathway), actin motor proteins, and GTP-binding protein ARF6 are central to the formation of microvesicles.5

Cells undergoing apoptosis release vesicles known as apoptotic bodies which range in size from 500 to 2000 nm and are generated by the blebbing of the plasma membrane.6 Recently, a non-membranous structure < 50 nm has been isolated by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation and was termed “exomere”.7 Our biological understanding of exomeres is still at its infancy, and further exploration is needed. In this review, we use the term “extracellular vesicles” (EVs) as a collective term for exosomes and microvesicles, unless a specific subpopulation is described.

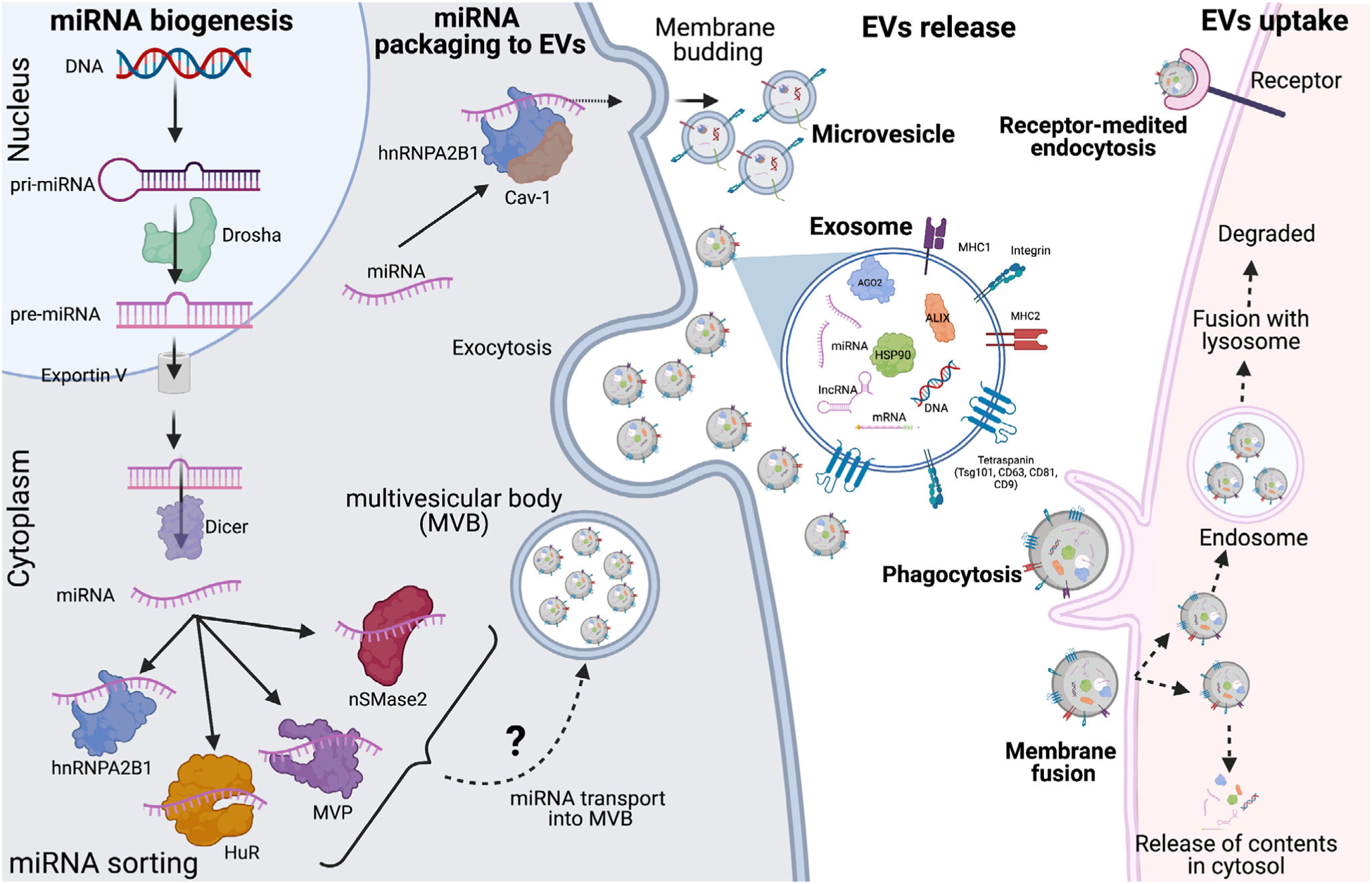

The cargo of EVs includes multiple proteins and molecules (i.e., mRNA, microRNA, DNA, cytokines, and phosphoproteins).3 EVs are often considered a snapshot of the physiological condition of the donor cell as they can modulate the recipient cell function and respond to physiological and pathological conditions. One of the most well-studied EV cargo groups is microRNAs (miRNA). miRNA are 18–24 nucleotide, small non-coding RNA. They are transcribed from DNA by RNA polymerase II or III to a primary transcript known as pri-mRNAs (Fig. 1). pri-miRNA is then cleaved by Drosha–DGCR8 complex to precursor (pre)-miRNA which is then exported to the cytoplasm via exportin-5.8 In the cytoplasm, DICER, along with other proteins, cleaves pre-miRNA to form mature miRNA. The functional strand of miRNA along with argonaute-2 is then loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) thus, in turn regulating gene expression8 (Fig. 1). miRNA has been shown to regulate various signaling pathways and modulate biological pathways such as innate immune responses, inflammation, cell death pathways, and more. Several miRNAs have even been implicated in inflammatory responses including miR-155, miR-21, miR-132, miR-146a, and let-7 and some have been explored in the context of liver disease.9 miRNAs packaged into the EVs modulate gene expression and function in the recipient cells. Indeed, circulating EVs with miRNA cargo have gained interest as potential biomarkers in pathological conditions.

FIGURE 1.

miRNA biogenesis, sorting into extracellular vesicles and Inter-cellular communication. miRNA is transcribed from DNA by RNA polymerase II or III into primary miRNA. Inside the nucleus, it is converted from primary miRNA to precursor-miRNA by Drosha and exported to cytosol by exportin V. In the cytosol, DICER process the pre-miRNA into mature miRNA. Different RNA-binding proteins and membrane proteins then bind to miRNA based on specific sequences in the miRNA or the secondary structure of miRNA and sort them into EVs. Donor cell releases EV via exocytosis in extracellular milieu. Recipient cells take up the released EVs by three different mechanisms. First, by direct fusion with the plasma membrane. Second, by phagocytosis and/or micropinocytosis and lastly be receptor-mediated endocytosis. Engulfed EVs can release their content directly into the cytosol or can end up in endosome. Endosomes containing EVs later is fused with lysosomes and its contents are degraded

In this review, we will discuss miRNA packaging into EVs by RNA-binding proteins and membrane proteins; EV-associated miRNA in mediating inter-cell communication; the relevance to alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, fibrosis, acetaminophen-induced liver injury, viral hepatitis, and liver cancer; the role of EV-associated miRNA in inter-organ communication; and finally, the potential of EVs as biomarkers and in therapeutics.

2|. MIRNA PACKAGING INTO EXTRACELLULAR VESICLES

Prior literature has outlined the packaging of small RNA (including miRNA, vault RNA, t-RNA, and snoRNA) into extracellular vesicles cargo. However, miRNA, more than other small non-coding RNAs, has been extensively explored. At the time of this writing, databases such as ExoCarta and Vesiclepedia (http://microvesicles.org) comprise thousands of entries for different classes of exosomal proteins and RNA, specifically mRNA and non-coding RNA.10,11 With increasing advances in technology and bioinformatic tools, our knowledge of the RNA packaged into EVs is ever expanding. However, there is still much to decipher regarding how these RNAs are destined into specific EVs. Indeed, there is a particular lack of sufficient literature about the sorting of miRNAs into EVs in the context of the liver. Nevertheless, in this section, we discuss reports regarding the role of RNA-binding proteins and membrane protein in sorting specific miRNA into the EVs under different physiological conditions (Fig. 1).

2.1|. RNA-binding proteins

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), as the name suggests, bind to specific RNA molecules and aid in facilitating their stability and guiding their sorting into the extracellular vesicles. Some of the notable examples of RBPs include heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, Y-box protein 1, human antigen R (HuR), Argonaute (AGO2), MEX-3 RNA-binding family member C (MEX3C), and Major vault protein (MVP).

2.1.1|. Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) are multifaceted RNA binding proteins that are involved in pre-mRNA processing (i.e., splicing, mRNA exporting, stability, and translation).12 The hnRNP family has 6 members: hnRNPA2B1, hnRNPC1, hnRNPG, hnRNPH1, hnRNPK and hnRNPQ. These have been shown to be associated with EVs or involved in the sorting of miRNA.13,14 Among them, the role of hnRNPA2B1 in sorting specific miRNA into EVs has been extensively explored. A previous study by Villarroya-Beltri and colleagues showed that sumoylation of hnRNPA2B1 promotes its interaction with miRNA that possess a GGAG/UGCA motif at the 3′ end (i.e., miR-198 and miR-601) and facilitates the sorting of these miRNAs into EVs.15 Furthermore, O-GlcNacylation of hnRNPA2B1 promotes binding to AGG/UAG motifs which, in turn, helps with the sorting of miRNAs into microvesicles (MV) instead of exosomes.16 Another recent study established a negative correlation between hnRNPA2B1 and miR-503 sorting into the extracellular vesicles from endothelial cells. Here, the authors showed that the knockdown of hnRNPA2B1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) led to increased expression of miR-503 in EVs. They further showed that miR-503 lacks any previously known motif for hnRNPA2B1 binding.17

hnRNPC1, another member of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, has shown to promote the sorting of miR-30d in EVs during embryonic adhesion to the endometrium.18,19 Furthermore, evidence also shows the direct binding of hnRNPC1 with miR-30d, which implies the packaging of miR-30d into EVs is dependent on hnRNPC1.18

Furthermore, another recent study demonstrated the packaging of hnRNPH1 mRNA into exosomes isolated from the serum of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), chronic hepatitis B, and liver cirrhosis patients.20 However, the miRNA packaged into EVs associated with hnRNPH1 has not yet been reported.

Another member of the hnRNP family, Synaptotagmin-binding Cytoplasmic RNA Interacting Protein (SYNCRIP) also known as hnRNPQ plays a role in the selective packaging of miRNA in EVs. A study by Santangelo et al. showed that hnRNPQ selectively packages miR-3470a and miR-194–2–3p in EVs.21 The authors further show that hnRNPQ specifically binds to the GGCU consensus motif present in these miRs and promotes the packaging of miRs into the EVs. Moreover, they validated hnRNPQ-dependent miRNA sorting into EVs and determined a process unique from hnRNPA2B1-dependent miRNA sorting. This function appears facilitated by an N-terminal unit for RNA recognition (NURR) domain in the hnRNPQ, which associates with the GGCU sequence present within miR-3470 and other exosome-associated miRNAs.22 In the context of the liver, miR-3470a plays an important role in liver regeneration, and miR-194–2–3p has been linked to HCC.23,24 This may imply a potential role of hnRNPQ in sorting miRNA specifically in different liver pathology.

2.1.2|. Y-box binding protein 1

Y-Box Binding Protein 1 (YBX-1) is an RNA-binding protein and there is vast literature available regarding its role in DNA repair, mRNA splicing, mRNA transport, and translation. Its role in various diseases and development has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.25 In short, YBX-1 is involved in sorting miR-133 and miR-223 into human endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes (EPC) upon hypoxia/reperfusion (H/R) and HEK293T cells derived EVs, respectively.26,27 In a study by Lin and colleagues, a clear down-regulation of YBX-1 led to a decrease in the number of miR-133 in EPC-derived exosomes; however, overexpressing YBX-1 lead to increased miR-133 in EPC-EVs.26 In another study, YBX-1 was specifically able to sort miR-223, but “not” miR-190 (a miRNA not associated with EVs), into the EVs. Although the exact mechanism of sorting remains unknown, it may be dependent on the secondary structure of RNA.27

2.1.3|. Argonaute

Argonaute 2 (Ago2) plays a role in miRNA biogenesis where along with GW182 it binds to the stable strand of the miRNA and loads them into the RISC complex. Recent studies have shown Ago2 packaging into EVs, specifically into the exosomes (along with miRNAs that prevent their degradation by RNase).28 Cha et. al have shown that Ago2 specifically sorts let-7a, miR-100, and miR-320a into EVs and that this sorting is dependent on upstream signaling by the KRAS-MEK-ERK pathway.28,29 Phosphorylation of Ago2 at serine 387 by KRAS-MEK-ERK signaling prevents the Ago2 association with endosomes and, in turn, inhibits the sorting of miRNA into EVs. Furthermore, knockdown of Ago2 led to decreased amounts of Let-7a and miR-100 in EVs isolated from Ago2-KD cells; in contrast, there was no change in the cellular level of these miRNA.28 These results suggest that Ago2 binding to miRNA can not only stabilize and prevent the degradation of miRNA but also helps the selective sorting of miRNAs in EVs.

2.1.4|. Human antigen R

Human antigen R (HuR) is a well-explored RNA-binding protein and is involved in mRNA splicing, mRNA stability, and transport.30 In one of the studies, the authors have shown that HuR promotes the packaging of miR-122 in Huh7 cells derived EVs upon cellular stress such as amino acid depletion. They also reported that HuR competes with Ago2 in binding to miR-122 and causes the unloading of miRNA from Ago2. Furthermore, ubiquitination of HuR promotes the release of miR122 on MVBs that further destines the packaging of miRNA into the EVs.31 The second study showed the role of HuR in packaging miR-1246 into the EVs in gastric cancer.32

2.1.5|. MEX-3 RNA-binding family member C

MEX-3 RNA-binding family member C (MEX3C) is an RNA-binding E3 ubiquitin ligase that is known to play a role in antiviral immunity.33 MEX3C is present in the EVs isolated by hepatocytes and by 3 different hepatocarcinoma cell lines (HKCI-C3, HKCI-8, and MHCC97L).34 In a study by Lu et. Al., a new role of MEX3C in miRNA sorting in the EVs was reported. They showed that MEX3C interacts with adaptor-related protein complex 2 (AP-2), a receptor known to be involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis.35 This association with endosomes further accentuates the sorting of miR-451a into the EVs as endosomes later lead to the generation of MVBs and thus play a significant role in EV biogenesis. Furthermore, down-regulating MEX3C or AP-2 leads to a decrease in the level of miR-451a in the EVs with no change on the cellular level.35 MEX3C association with Ago2 was demonstrated through immunoprecipitation, but the implication of this interaction with miRNA sorting in the EVs was not explored.35

2.1.6|. Major vault protein

Major vault protein (MVP) is a 100 kDa ribonucleoprotein that belongs to the vault mass protein complex. This vault mass comprises of MVP, vault poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (vPARP), telomerase-associated protein 1 (TEP1), and untranslated short vRNA.36 MVPs have been detected in the EVs from different cancer cell lines including hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells.37–39 Along with their detection in EVs isolated from hepatocytes, human breast milk, platelets, and B-cells, they have also been implicated in many other bodily fluids.34,40,41 The role of MVP in regulating miRNA sorting into EVs has been described in detail by Teng et al.42 This team profiled miRNA in exosomes derived from 3 different colon cancer types including primary mouse colon cancer, liver metastasis of colon cancer, and naive colon tissues.42 Their results indicated that tumor suppressor miR-193a was packaged into the EVs by interaction with MVP. Furthermore, knockout of MVP lead to miR-193a accumulation in the EV donor cells instead of EVs themselves. The authors also found that exosomal miR193a directly correlated with aggressive forms of colon cancer.42

2.2|. Membrane proteins

2.2.1|. Caveolin-1 (cav-1)

Caveolae are a small invagination of 50–100 nm present in the plasma membrane and are made up of a membrane protein known as caveolin-1 (cav-1), which plays an imperative role in signal transduction and membrane trafficking.43 Cav-1 is involved in the miRNA sorting into the microvesicles.16 Furthermore, cav-1 tyrosine 14 (Y-14) phosphorylation after noxious stimuli, in particular, promotes interaction with hnRNPA2B1 and RNA binding proteins, and traffics the complex of cav-1 and hnRNPA2B1 directly into microvesicles.16 Since hnRNP2B1 has been described as one of the regulators of miRNA sorting into EVs, it is implicated in the indirect role of cav-1 in miRNA sorting. Cav-1, Y-14 phosphorylation has also been implicated in promoting the O-GlcNAcylation of hnRNPA2B1, which is an important post-translational modification of hNRNPA2B1 (see above), to sort miR-17 and miR-93 into microvesicles.16 Furthermore, microvesicles from endothelial cells comprising of cav-1, hnRNPA2B1, miR-17, and miR-93 complex activate lung Mϕs and elicit innate immune responses by promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β.16 These findings indicate that Cav-1 may play a role in EV biogenesis and miRNA packaging in conjunction with other miRNA sorting proteins.

2.2.2|. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2

Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) is a hydrolase enzyme that is involved in the generation of lipid ceramide by hydrolyzing the membrane lipid sphingomyelin. nSMAse2 is involved in various cellular functions such as cell growth, apoptosis, and inflammation.44 The role of ceramides in EV biogenesis has been well established: nSMase promotes the biogenesis and release of EVs in an ESCRT-independent manner45 The role of nSMase 2 in sorting specific miRNA into the cargo of EVs was first reported in cancer progression and metastasis. Here, the authors showed a direct role of nSMase-2 in sorting miR-16 and miR-146a into the EVs, as inhibiting nSMase 2 either with a chemical inhibitor (GW4869) or by siRNA lead to reduced secretion of miR-16 and miR146a in EVs. Furthermore, overexpression of nSMase2 increased the amounts of these miRNAs in EVs.46 A follow-up study showed that nSMase 2-mediated release of EVs from 4T1 breast xenografts packaged miR-210 into EVs which promoted angio-genesis and migration in recipient endothelial cells.47 These results indicate that nSMase can sort specific miRNA in EVs by enhancing ceramide generation. In non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatocytes-derived ceramide enriched EVs are pro-inflammatory and promote Mϕ chemotaxis.48 However, the role of both nSMase 1 and 2 in sorting miRNAs in EVs in the context of various liver diseases has yet to be elucidated.

2.2.3|. Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4 and Alix

The vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4 (Vps4A) (along with 4 different protein complexes) is a part of the Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery: ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, ESCRT-III, and Vps4.49 Earlier studies have shown that ESCRT-I and ESCRT-II are involved in sorting of cargo while ESCRTI-II complex and Vps4A are necessary for releasing the exosomes by inducing membrane scission50 In cancer cells having a low expression of Vps4, over-expression of Vps4 retained tumor suppressor miRNAs (i.e., miR-122–5p, miR-33a-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-193a-3p, miR-16–5p, and miR-29b-3p) in the cells. However, EVs released by Vps4 overexpressing cells were enriched in oncomiRs (i.e., miR-27b-3p and miR-92a-3p). These results indicate a direct involvement of Vps4 in sorting specific oncomiRs into EVs; however, the exact mechanism needs to be elucidated.51,52

Alix, part of the previously mentioned ESCRT machinery, is involved in the biogenesis of EVs and is also a part of the exosomal cargo.53 A recent study outlined the mechanistic details of how Alix (along with lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA) and ESCRT III-dependent pathways) promote the sorting and delivery of tetraspanins in EVs.54 Alix is also involved in the packaging of miRNAs within EVs released by human liver stem-like cells (HLSCs).55 EVs released from HLSCs were not only enriched in Alix but also had Ago2 (as shown by immunoprecipitation experiments). In addition, this association of Alix and Ago2 helped in sorting of miR-24, miR-31, miR-125b, miR-99b, miR-221, miR-16, and miR-451 in HLSC-derived EVs. Furthermore, knockdown of Alix significantly decreased the copies of these miRNA into the EVs, suggesting a direct involvement of Alix in miRNA sorting into the EVs.55

Table 1 summarizes the list of RNA binding protein and membrane proteins involved in miRNA sorting in extracellular vesicles. Considerable research over the last few years has outlined various mechanisms by which miRNAs are sorted into the EVs. However, there is still much work to be done to understand the specifics of this sorting in greater detail. The presence of multiple proteins in EVs cargo (such as Alix, Ago2, and Cav-1) raises the possibility of the orchestration of proteins sorting the miRNA into the EV in a systemic manner. However, “how” the presence of these proteins affects each other and the associated sorting mechanisms, is not known. Indeed, the possibility that cells secrete miRNAs in EVs to dispose of them cannot be ruled out. Systemic studies and increased advances in the EV field would help us to understand details, in the future.

TABLE 1.

List of RNA binding proteins and membrane proteins involved in sorting miRNAs into extracellular vesicles

| Name of the protein | Mechanism | miRNA sorted | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA binding proteins | |||

| hnRNPA2B1 | Sumyolation and binding to GGAG/UGCA motif | mirR-198, miR-601 | 15 |

| hnRNPA2B1 | O-GlcNacylation and binding to AGG/UAGmotif | miR-17, miR-93 | 16 |

| hnRNPC1 | Not known | miR-30d | 18 |

| SYNCRIP/hnRNPQ | Binding to GGCU motif | miR-3470, miR-194–2–3p | 21 |

| Y-box binding protein 1 | Not known | miR-133 and miR-223 | 26,27 |

| AGO2 | Phosphoryaltion at Serine 387 by KRAS-MEK-ERK signaling pathway | Let7a and miR-100 | 28,29 |

| HuR | Competing with Ago2 and promoting its packaging | miR-122 | 31 |

| MEX3C | Its direct binding with AP-2 | miR-451a | 35 |

| MVP | Not known | miR-193a | 42 |

| Membrane proteins | |||

| Cav-1 | Binds along with hnRNPA2B1 | miR-17 and miR-93 | 16 |

| nSMAse2 | ESCRT independent pathway of EV release | miR-16, miR-146a and miR-210 | 46,47 |

| Vps4A | ESCRT dependent pathway of EV release | miR-122, miR-33a, miR-34a, miR-193a, miR-16, miR-29b, miR-27b and miR-92a | 52 |

| Alix | Is a part of ESCRT machinery and binds directly to Ago2 for miRNA sorting | miR-24, miR-31, miR-125b, miR-99b, miR-221, miR-16 and miR-451 | 55 |

3|. ROLE OF EVS AND ASSOCIATED MIRNA CARGO IN CELL-CELL COMMUNICATION AND IN MODULATING LIVER PATHOBIOLOGY

EVs can be produced by almost every type of cell in the liver including hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs), KCs (Kupffer cells), and the repertoire of immune cell populations such as Mϕs, neutrophils, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and T and B-cells.56 Several studies have shown a dynamic crosstalk between the different cell types in the liver, both within the immune cell compartment and between immune and parenchymal cells, facilitated by EVs. In this sub-section, we further describe how the EV-associated miRNA and other cargo molecules promotes this crosstalk and contribute to inflammation and other liver pathological conditions (Fig. 2).

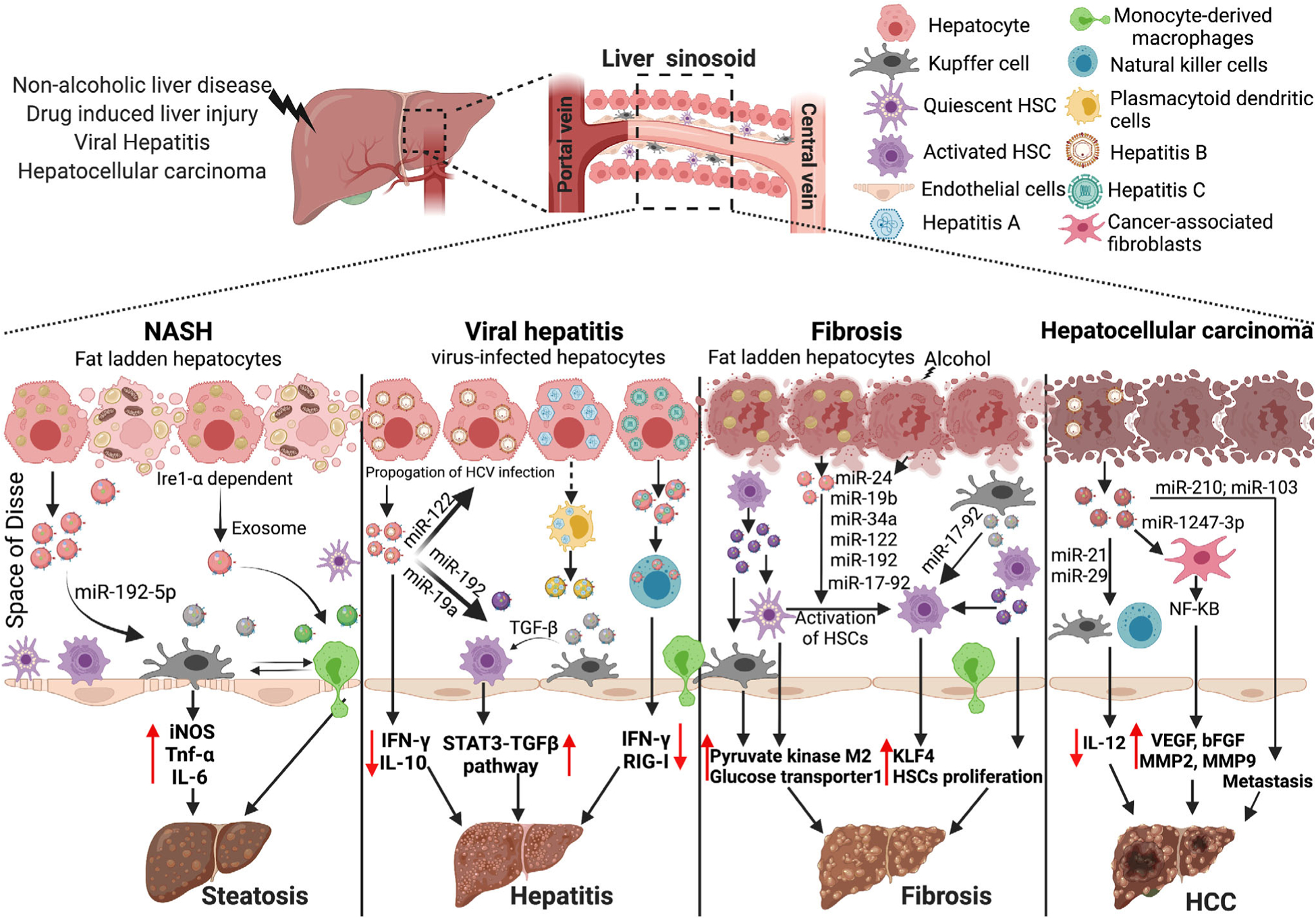

FIGURE 2.

EVs-miRNA in the physiopathology of liver diseases. EVs and EVs-associated miRNA promotes the pathogenesis of various liver disease and different stages. In non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatocyte-derived EVs are enriched in miR-192–5p and when taken up by Mϕs induce production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In viral hepatitis, miR-122 enriched hepatocyte-derived EVs help in propagation of hepatitis-B virus, and miR-192 enriched hepatocyte-derived EVs activated hepatic stellate cells. During fibrosis, hepatocyte-derived EVs enriched in miR-24, miR-19b, miR-34a, miR-122, miR-192, and miR-17–92 lead to activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSC). EVs from activated HSC also promote the proliferation of HSC and in turn promote fibrosis. In hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatoma-cell derived EVs enriched in miR-210 and miR-103 promote pro-tubulogenesis in endothelial cells and metastasis in endothelial cells, respectively. KLF4, Kruppel-like factor 4; HSC, hepatic stellate cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor

Once the miRNA and other biological moieties are packaged into the EVs, they are released into the extracellular milieu. The cargo of EVs reflects the physiological state of the donor and, after their successful uptake by the recipient cell, modulates its functional response to the stimuli or growth factors and thus alters their homeostasis and/or affects their physiological status. The eventual fate of the released EV cargo and the mechanism by which EVs target and deliver their content to the recipient cells still warrants further studies. Generally, the first step in this process is targeting of the recipient cells and subsequent binding to the surface of the recipient cell. The second step involves the uptake of the EVs via clathrin-dependent and -independent pathways, and their fate in the acceptor cells that finally culminate in the delivery of effector signal molecules to the recipient cells. These steps have been discussed and reviewed in detail elsewhere56,57 and will be discussed here briefly.

It is worthwhile to mention here that, there is a lack of well-defined stepwise processes by which recipient cells are targeted by EVs. Nevertheless, several studies have indicated that a diverse variety of recipient cells can take up EVs from a donor cell. For instance, it has been observed that both hepatic stellate cells and Mϕs can take up the EVs derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes (which can modulate their function).58

Wide varieties of cellular receptors are involved in the binding of EVs to the recipient cells such as tetraspanins, integrins, lipids, T-cell immunoglobulin, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components.56 Nazarenko et.al have shown that exosomal tetraspanins can interact with the integrins on the cell surface of the recipient cells which further facilitates the docking and uptake of EV cargo by recipient cells.59 Another study has shown the importance of integrins in directing cancer-cell derived EVs to different organs to develop pre-metastatic niche.60 EVs with integrins α6 and β5 subunits were found in Kupffer cells (KCs) in the liver, while EVs with integrins β3 were detected in the CD31-positive endothelial cells of the brain suggesting that EVs can specifically target the recipient cells.60 The lipid components of EVs can also promote the binding to the recipient cells. For instance, EVs enriched in phosphatidyl serine (PS) are taken up by Mϕs. The significance of PS in this scenario is reiterated by reduction in EVs uptake by Mϕs when PS is blocked by annexin V.61

Once EVs bind to the cell surface of the recipient cells, they remain at the plasma membrane and elicit an immune response, (i.e., dendritic cell-derived EVs harboring major histocompatibility complex can activate T-cells).62 Furthermore, EVs are also internalized by clathrin-dependent or clathrin-independent endocytosis. Clathrin-independent pathways involve macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and cav-1 dependent endocytosis63 (Fig. 1). Following internalization, EVs deliver their cargo inside the cells in several ways. Depending on the internalization route, it is most likely EVs end up in the endosomes and get degraded by lysosomes64 (Fig. 1). However, in certain cases internalized EVs escape the lysosomal degradation and release their contents into the cytosol of the recipient cell. By extension, in pathological conditions in which lysosomal function is dysregulated (such as in alcoholic liver disease), contents of the internalized EVs are released in the cytosol.65

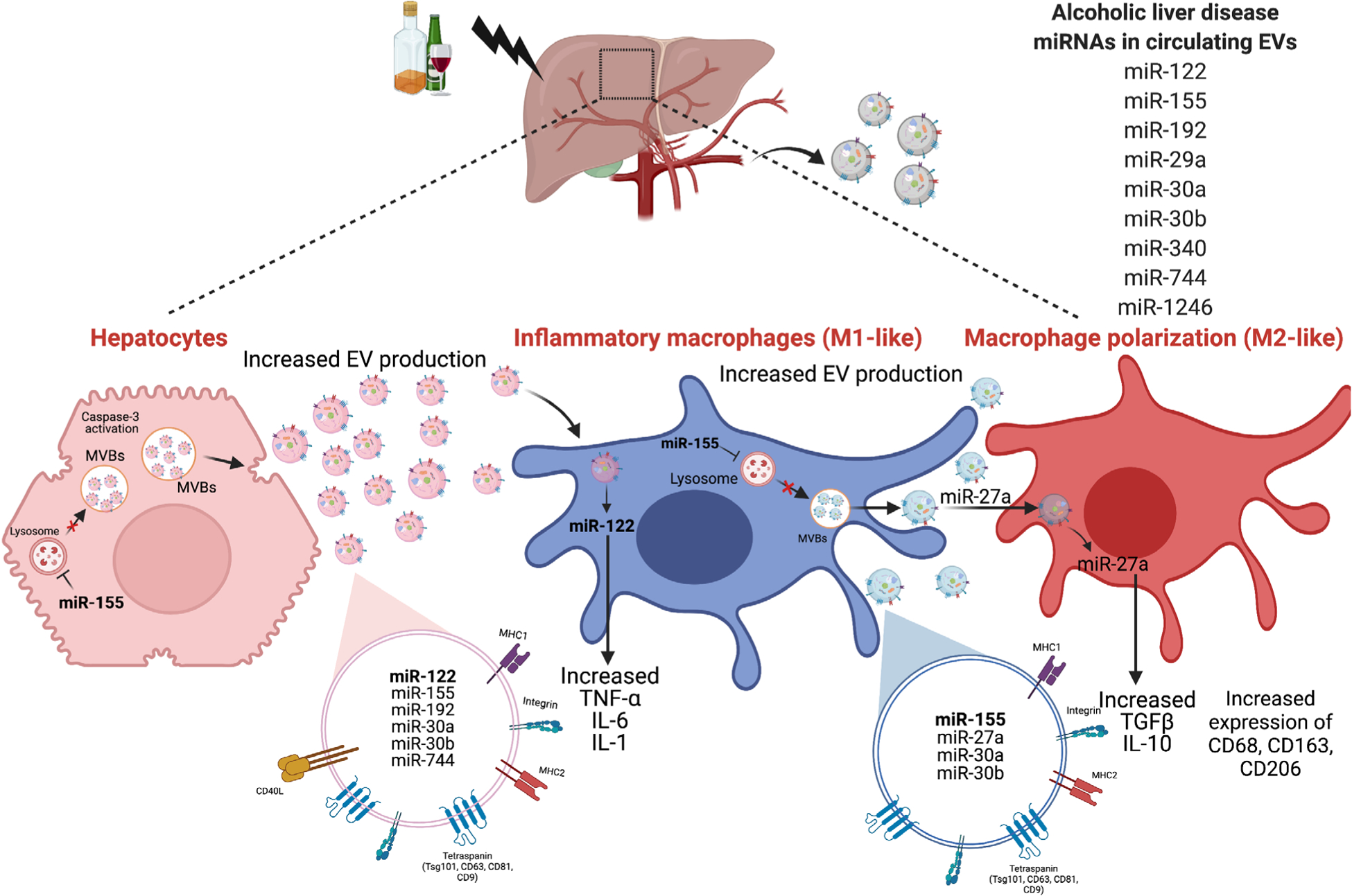

3.1|. Role of EVs and their associated miRNA in alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a multifactorial liver disease in which heavy alcohol consumption leads to a wide spectrum of pathological phenotypes ranging from steatosis, hepatitis, and fibrosis/cirrhosis followed by hepatocellular carcinoma.66 Patients afflicted with ALD have elevated levels of circulating EVs in serum compared to healthy controls. This observation is recapitulated in murine models of alcohol-induced steatohepatitis where ALD mice have an increased number of EVs compared to control mice.67 This increase in EVs positively correlates with increased liver damage as measured by the Alanine transaminase (ALT) levels (a liver enzyme that is released into the bloodstream after excessive liver damage).67 Furthermore, assessment of the cargo of the EVs isolated from the serum of alcohol-fed mice shows a significant increase in the level of miR-122, miR-192, miR-30a, miR-744, miR-1246, and miR-30b compared to pair-fed control mice (Fig. 3). Similar findings were obtained in human alcoholic hepatitis (AH) plasma samples where EVs appear enriched with miR-192 and miR-30a.67 Another study that used a gastric infusion model of alcohol for developing ALD identified an enrichment of let7f, miR-29a, and miR-340 in EVs derived from the blood of the mice.68 miR-155, an inflammiR was also present in the EVs obtained from 2 liver injury murine models: alcohol-induced liver injury and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9/4 ligand-induced inflammatory cell-mediated liver damage.69 A recent study demonstrated that alcohol-induced miR-155 disrupts the autophagic flux in both hepatocytes and Mϕs by inhibiting mechanistic targets of rapamycin (mTOR) and Ras homolog enriched in the brain (Rheb), and lysosomal associated proteins (LAMP) 1 and 2. Mechanistically, inhibition of LAMP1 and LAMP2 proteins cause lysosomal dysfunction which leads to increased EV production and subsequent release from hepatocytes and Mϕs.65 Some in vitro studies have also shown that alcohol leads to increased EV production by different liver cell types (liver packages unique cargo and can be taken up by other liver cells). In a related study, hepatocyte-derived EVs enriched with hepatocyte-specific miRNA (i.e., miR-122), were shown to be taken up by the myeloid cells (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Extracellular vesicles and their role in pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol-induced liver injury increases EVs in circulation containing different miRNAs such as miR-122, miR-192, miR-155, miR-30a. Alcohol injury causes hepatocytes to release increased levels of EVs via activation of cell death pathways such as apoptosis and dysregulating lysosomal function. Alcohol-induced hepatocytes derived EVs are enriched in miRNA-122 and activate pro-inflammatory phenotypes in Mϕs. Alcohol also causes increased EV release from Mϕs via lysosomal dysregulation. These EVs, when taken up by naïve monocytes, induce M2 Mϕ phenotypes. MVB, multivesicular bodies

Momen-Heravi et al. recently showed that myeloid cells that inherently have a negligible amount of miR-122 expression display high levels of miR-122 after taking up hepatocyte-derived EVs. In addition, they showed a significant reduction in heme oxygenase1 levels which sensitizes myeloid cells to LPS and enhances proinflammatory cytokine production.70 Wang et al. also reported a correlation between ER stress and alcohol-induced liver injury. In a murine model of alcohol-induced liver injury, an endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) inhibitor 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) attenuated the level of miR-122 level in serum-EVs and in turn led to decreased liver damage.71

Alcohol also induces the production of EVs in primary human monocytes and THP-1 monocytic cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. EVs isolated from alcohol-exposed monocytes facilitated the polarization of naïve monocytes into M2 Mϕs as marked by increased expression of CD206, CD163, IL-10, and increased phagocytic activity. miRNA profiling of EVs has revealed an increase in the level of M2-polarizing miRNA, miR-27a, in alcohol-treated monocytes. Furthermore, treating naive monocytes with control EVs overexpressing miR-27a polarized naive monocytes toward M2 Mϕs.72 Proteomic analysis of the EV cargo isolated from alcohol-fed mice has also shown the presence of a unique signature for proteins involved in inflammation, cell movement, and development, as compared to control EV cargo. When EVs isolated from ALD mice were transferred to healthy mice, elevated iMCP-1 levels became apparent. In addition, they also depicted an increase in proinflammatory M1 Mϕs, concomitant with reduction in anti-inflammatory M2 Mϕs. In vitro, ALD-EVs increased TNFα and IL-1β production in Mϕs.73 Alcohol-treated hepatocytes also show an enrichment of the CD40 ligand (CD40L) which were packaged into the EVs in a caspase-3 dependent manner. Hepatocyte derived EVs with CD40L have been shown to induce proinflammatory responses in Mϕs.74 A recent study also showed that EVs isolated from alcohol-exposed hepatocytes have mitochondrial dsRNA that, when taken up by KCs, leads to TLR3 activation and release of IL-1β followed by IL-17A production in γδ T cells.75

These results indicate that increased ALD-EVs in circulation mediate inter-cell communication to promote inflammation and subsequent progression of alcoholic liver disease.

3.2|. Role of EVs and their associated miRNA in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Previous studies in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease have reported on the circulating EV population (both exosomes and microvesicles).76 EVs from high-fat diet fed mice, when injected into control mice fed on chow diet, lead to increased liver damage and an accumulation of immature myeloid cells.77 EVs released from the lipotoxic hepatocytes and their effect on immune cells has been greatly explored in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).78–81 Hirsova et al. showed that hepatocyte-derived lipotoxic EVs were released through the ligand-independent activation of death receptor 5 (DR5) and rho-associated, coiled-coil-containing protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) pathways. Additionally, these EVs were enriched in the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), which causes activation of DR5 on Mϕs and, in turn, stimulates the NF-κB pathway to induce production of IL-6 and IL-1β.78 Another study showed the involvement of unfolded protein response sensor inositol-requiring protein 1- (IRE1) in release of lipotoxic EVs from hepatocytes which recruited monocyte-derived Mϕs to the liver and promoted inflammation in NASH.79 Furthermore, in a study conducted on mouse models and isolated hepatocytes, extracellular release of lipotoxic EVs enriched in C-X-C motif ligand 10 (CXCL10) was observed. This phenomenon was likely mediated by mixed lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) and has been reported to promote Mϕ chemotaxis.81 A recent study also showed that EVs derived from lipotoxic hepatocyte are enriched in integrin β1 (ITGβ1), which contributes to liver inflammation by promoting monocyte adhesion.80 Non-coding RNAs are also known to be associated with EVs released from lipotoxic hepatocytes.76,82,83 Indeed, mice fed on choline Deficient L-Amino Acid (CDAA) or on high-fat diet show high levels of miR-122 and miR-192 in the EVs obtained from their blood.76 Furthermore, these hepatocyte-derived lipotoxic EVs are also enriched in miR-192–5p and, when taken up by Mϕs, causes activation of Rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mammalian target of rapamycin) and results in increased expression of iNOS, TNF-α and IL-682 (Fig. 2).

Overall, the release of lipotoxic hepatocyte EVs through multiple mechanisms promotes pro-inflammatory phenotypes in recipient immune cells and contributes to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

3.3|. Role of EVs and their associated miRNA in viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a non-enveloped virus that hijacks host endosomal machinery and packages virions into the exosome-like vesicles known as eHAV. A recent study by Jiang et al. showed that pX, a structural protein of HAV, interacts directly with the ALIX protein of the ESCRT machinery to promote the secretion of HAV into the exosomes.84 Furthermore, Costafreda et al. recently reported the involvement of phosphatidylserine receptor HAVCR1 and the cholesterol transporter NPC1 in delivering the cargo of HAV exosomes to the cytosol.85 Another study showed that HAV infected plasmacytoid dendritic cells may release HAV that has been packaged into exosomes, which would enable the virus to escape host immune surveillance.86,87

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has also been shown to result in an increase of circulating EVs comprising of HBV nucleic acids and HBV proteins.88 Indeed, when HBV enriched EVs were taken up by natural killer (NK) cells, the interaction impaired the HBV cytolytic activity and their ability to produce IFN-γ. There was also a decrease in the expression of viral recognition receptor retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) on NK cells, which dampened the anti-viral response and increased HBV persistence. A study by Li et. al. revealed that IFN-α led to the induction of resistance to HBV infection by transferring the antiviral response from liver non-parenchymal cells (LNPCs) to HBV-infected hepatocytes through EVs.89 A follow-up study reported that EVs from IFN-α-treated Mϕs or responders of polyethylene glycol (PEG) linked IFN-α (pegIFN-α) treatment, when added to HBV-infected hepatocytes, inhibited HBV replication and transcription via miR-193a-5p, miR-25–5p, and miR-574–5p, suggesting that EV associated miRNA can promote an anti-viral state.90

Hepatitis C virus exploits the EVs biogenesis machinery to promote its spread. Viral particles packaged in the EVs escape immune surveillance and hijack the host immune system for its own propagation. A previous study by Bukong et. al. showed the presence of HCV viral RNA in EVs isolated from Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected patients and HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells.91 Interestingly, reticulon-3 appears to modulate packaging of replication-competent HCV RNA into EVs.92 Furthermore, HCV RNA in the EVs was associated with Ago2, HSP90, and miR-122.91,93 Inhibiting HSP90 (or loading miR-122 inhibitor into the exosomes) prevented the spread of HCV to naïve uninfected cells, thus implicating the role of miR-122 and HCV RNA EVs in the propagation of HCV infection91,93 (Fig. 2). Hepatocyte-derived HCV RNA containing EVs, when taken up by HSCs, promote the expression of fibrotic genes. Authors showed that the presence of miR-19a in these hepatocyte-derived HCV-EVs promoted fibrosis by targeting SOCS3 which, in turn, led to the activation of the STAT3- TGF-B signaling pathway94 (Fig. 2). A recent study also showed the horizontal transfer of miR-192 from hepatocyte-derived HCV-EVs to HSCs where they promoted transdifferentiation of HSC into myofibroblasts via TGF-B1 up-regulation.95 Wang et al. showed that EVs from HCV-infected hepatocytes containing HCV-RNA regulate the differentiation of monocytic myeloid cells into myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) by inhibiting miR-124 in monocytic myeloid cells.96 Finally, an increase of MDSCs both increases T follicular regulatory (TFR) differentiation and IL-10 production and decreases T follicular helper cells (TFH) and IFN-γ production, which contribute to HCV persistence.96

3.4|. Role of EV and their associated miRNA in drug-induced liver injury

In acetaminophen-induced liver injury, the number of circulating EVs enriched in miRNAs and specific proteins is increased.69 A study by Cho et al. demonstrated that EVs from a murine model of acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury could induce the expression of hepatic pro-inflammatory genes and apoptosis-related proteins in the recipient APAP-naïve mice.97 Furthermore, these EVs were enriched with miR-122, miR-192, and miR-155.98 Additionally, in a rat model of acetaminophen-induced liver injury and in primary human hepatocytes, an increase in circulating EVs was observed that were also enriched in miR-122 and albumin mRNA.99 In another study, miRNA profiling was performed in the EVs isolated from the sera of rats either after administration of APAP or thioacetamide, both of which induce liver injury. An enrichment of miRNAs-122a-5p, 192–5p, and 193a-3p was observed in the case of APAP-induced liver injury, which suggests an injury-specific signature of miRNAs.100

3.5|. Role of EVs and their associated miRNA in liver fibrosis

Alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease culminates in liver fibrosis, which is marked by the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Several miRNAs have been shown to regulate liver fibrosis (including miR-21, miR-122, miR-155, and miR-208) both directly and indirectly.101–104 EVs isolated from lipotoxic hepatocytes or from the sera of ALD mice models activate HSCs,105–107 and EVs isolated from lipotoxic hepatocytes, when cultured along with HSCs, induce increased pro-fibrotic gene expression in HSCs compared to control EVs. Notably, these EVs were preferentially enriched in miR-24, 19b, 34a, 122, and 192.107 HSCs cultured in the presence of alcohol have reportedly displayed a significant increase in the expression of miR-17–92 cluster and the down-regulation of miR-19b, which promotes fibrotic gene expression and subsequent activation of HSCs.105 Furthermore, when treated with alcoholic hepatitis-hepatocyte derived EVs (AH-HC-EVs), HSC activation leads to the up-regulation of 20 miRNAs (including miR-27a and miR-181) as demonstrated by miRNA sequence analysis.106 EV-associated miR-103–3p released from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated Mϕs, and promoted HSCs proliferation and activation by targeting Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4).108 Hepatic stellate cells are also activated by the EVs released by other HSCs. Chen et. al showed that cellular integrin αvβ3, integrin α5β1, and heparan sulfate proteolgycans (HSPG) help the HSC-derived EVs to specifically target delivery of the EV cargo to HSC.109 In fact, EVs secreted by activated HSCs, when taken up by quiescent HSCs and liver nonparenchymal cells (i.e., KCs, and LSECs), modulate the metabolism of liver by delivering glycolysis-related proteins, glucose transporter 1, and pyruvate kinase M2 through their cargo.110 Furthermore, EVs derived from endothelial cells also activate HSCs and promote fibrosis via sphingosine1 phosphate.111,112 A recent study by Gao et al. showed that HSCs released platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-alpha (PDGFRα) enriched EVs in an Src homology 2 domain tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2)-dependent manner. Furthermore, SHP2 inhibited HSC autophagy via activation of mTOR signaling and promoted the release of profibrogenic EVs.113 Interestingly, quiescent HSC-EVs appear to have high levels of twist related protein 1 (TWIST1). TWIST-1 regulates the expression of miR-214 and miR-199a-5p which, in turn, decreases the mRNA levels of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) and suppresses fibrogenic signaling in HSCs.114,115

3.6|. Role of EVs and their associated miRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma

EVs regulate the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in a myriad of ways. EVs from HCC cells can promote the growth and metastasis of cancer cells, increase angiogenesis, promote epithelialmesenchymal transition (EMT), and modulate the immune response in the cancer.116 A study by Costa-Silva et al. reported that EVs can form a premetastatic niche. Their study emphasizes that EVs derived from pancreatic cancer can be taken up by KCs or HSCs and promote subsequent formation of a pro-fibrotic environment conducive for liver metastasis.117 Furthermore, EVs released by CD90+ liver cancer cells were enriched in lncRNA H19 that promotes angiogenesis in the endothelial cells and increases their cell-cell adhesion properties.118 Another study by He et al. profiled exosomal RNA and protein from different HCC cell lines and observed the presence of several protooncogenes and S100 family proteins. They also suggested that EVs from HCC cell lines could increase the MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion from immortalized hepatocyte line (MIHA) and thus contribute to the enhanced migratory and invasive capabilities.34

Several miRNAs have been well characterized and associated with the progression of HCC at different stages and pathways. Several have also been correlated with patient prognosis and may be potential biomarkers. For instance, in HCC, the expression of nSMase1, was significantly down-regulated which directly correlated with poor long-term survival of HCC patients.119 The reduced expression of nSMase1 leads to an increased sphingomyelin to ceramide ratio. Furthermore, if the ratio of sphingomyelin to ceramide was restored by overexpressing nSMase1, suppressed HCC cell growth actually promoted apoptosis of tumor cells.119

HBV infection is one of the leading causes of HCC progression and in HCC patients, there is a down-regulation of Vps4 that correlates with increased susceptibility to hepatitis B viral infection, increased tumor size, and metastasis. Indeed, a study by Wei et, al. showed that when cancer cells have low expression of Vps4, and are incubated with self-derived EVs, an increase in cell growth and a significant increase in cell migration and invasive capacity became apparent.52 Interestingly, HCC cells infected with HBV lead to an increased number of EVs enriched in miR-21 and miR-29, which inhibits IL-12 production in both Mϕs and dendritic cells120–122 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the decrease in IL-12 prevents the function of NK cells and abolishes the clearance of cancer cells. Zhou et al. showed that HCC derived EVs promote miR-21-mediated development of normal HSCs into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF). They further showed that miR-21 down-regulates PTEN in HSC which leads to activation of PDK1/AKT signaling. These CAFs can further support the growth and progression of the cancer by stimulating the production of pro-angiogenic cytokines such as VEGF, MMP2, MMP9, bFGF, and TGF-β123 (Fig. 2). Another study implicated miR-1247–3p in the EVs derived from HCC cells in the conversion of normal fibroblasts to CAFs.124 Authors showed that EVs from high metastatic HCC cells lead to the activation of NF-κB signaling which promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, further promoting the migration of liver cancer to the lungs.124 miRNA associated with EVs derived from HCC cells also promotes tumor angiogenesis. Indeed, high levels of EVs-associated miR-210 in the sera of HCC patients directly correlate with higher micro-vessel density in HCC tissue. Mechanistically, EV-associated miR-210 inhibits SMAD4 and STAT6, which promotes pro-tubulogenesis in endothelial cells in vitro.125 Another study by Fang et al. showed that hepatoma-cell derived EVs with miR-103 promotes metastasis in endothelial cells by directly targeting the protein involved in junctions, such as VE-Cadherin (VE-Cad), p120-catenin (p120), and zonula occludens 1.126

Finally, HCC-EV associated miR-25 plays a role in epithelialmesenchymal transition (EMT) as shown by Wang et. al. Indeed, mir-25 accomplishes this by inhibiting the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha (RhoGDI1), which results in overexpression of Snail (a key mediator of EMT), and promotes the migration potential of cancer cells.127 A recent study highlighted the role of HCC-EVs in escaping anti-tumor immunity. The authors showed endoplasmic reticulum stress induces HCC to release EVs enriched in miR-23a-3p that inhibits PTEN expression and leads to constitutively active Akt and high PDL1 expression in Mϕs. The increase in PDL-1 expression inhibits T-cell function and facilitates the tumor cells to evade the immune system.128 These results indicate the various mechanisms by which EV-associated miRNAs can modulate different aspects of HCC pathogenesis.

4|. EV ASSOCIATED MIRNA AND THEIR ROLE IN INTER-ORGAN COMMUNICATION WITH LIVER

Patients with liver disease commonly experience systemic abnormalities. There is evidence supporting the occurrence of crosstalk between the liver and other organs during alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease.129 For instance, alcohol consumption disrupts the intestinal epithelium and causes endotoxin accumulation in the portal circulation, which plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease.130 Recent studies have explored the potential role of EVs as carriers of messenger cargo that facilitate inter-organ communication under different pathological conditions. Povereo et al. demonstrated that EVs released by lipotoxic-hepatocytes promote migration and tube formation in an endothelial cell line, a prerequisite for angiogenesis.83 Furthermore, inhibition of caspase 3 prevents the proangiogenic activity of these microvesicles. The authors also showed that ectoenzyme vanin-1 (VNN1) on the EV surface interacts with lipid rafts on endothelial cells and facilitates the angiogenic effects.83 A recent study further strengthens the phenomenon of crosstalk between EVs derived from lipotoxic hepatocyte and cardiovascular disease.131 Indeed, the presence of miR-1 in the cargo of hepatocyte-derived EVs promotes endothelial inflammation via KLF4 suppression and NF-κB activation, which in turn promotes atherogenesis.131 Similarly, another study showed that EVs from ethanol-treated endothelial cells promote vascularization in alcohol-naïve endothelial cells. This phenomenon is mediated by up-regulated expression of proangiogenic long non-coding RNAs MALAT1 and HOTAIR and down-regulated expression of anti-angiogenic miRNA-106b.132

Liver injury is also detrimental to the lungs, as it is associated with the promotion of pulmonary inflammation. Increased miR-122 in circulation after an acute liver injury is taken up by alveolar Mϕs via TLR7 and leads to activation of inflammatory responses. Furthermore, TLR7-KO or mutated miR-122 binding sequence on TLR7 attenuates the inflammatory response in alveolar Mϕs, suggesting a direct role of hepatic miR-122 in pulmonary dysfunction.133 Recently, adipose tissue was identified as a target for hepatocyte-derived EVs.134 Interestingly, this study suggested that EVs released by the liver in response to short-term lipid accumulation promote adipogenesis, whereas increased lipid load for a longer duration causes induction of adipose lipogenesis. The release of EVs was Rab27A-dependent and more importantly dependent on Rab27A post-translation modification of geranylgeranylation by geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS). Moreover, liver-adipose tissue crosstalk may be mediated by hepatocyte EVs enriched in miR-122, let-7e-5p, miR-31–5p, and miR-210–3p.134 Indeed, a recent study showed that miR-130a-3p in hepatic EVs improve abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in adipose cells. Mechanistically, miR-130a-3p decreases expression of PH Domain and Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein Phosphatase 2 (PHLPP2) that, in turn, activates the AKT-GLUT4 signaling pathway in adipose cells.135 Overall, these studies suggest an exciting avenue regarding how EV cargo modulates inter-organ crosstalk and contributes to disease pathogenesis.

5|. EV MIRNA AS POTENTIAL BIOMARKERS IN LIVER DISEASES

The identification of biomarkers is beneficial for detecting and monitoring disease at early stages. Various liver diseases are assessed by either measuring the level of hepatic enzymes (such as ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), or by using invasive techniques (i.e., liver biopsy). Liver biopsy is considered the standard method for both diagnosis and delineating the stage of liver disease. However, its invasive nature and the lack of suitable alternatives warrant the need for devising non-invasive diagnostic techniques.

EVs are released by all liver cells and are stably present in biological fluids such as serum, plasma, and urine. Furthermore, the release of EVs to the extracellular milieu is a dynamic process that is altered throughout the progression of pathobiological conditions. Therefore, the exploration of EVs as non-invasive biomarkers seems lucrative. Indeed, researchers have a unique opportunity to use EVs in longitudinal studies to understand disease progression in clinical settings. As described above, different miRNAs are associated with EVs under different liver conditions and have been investigated in detail as potential biomarkers. In ALD, miR-155 and miR-122 are increased in the sera of alcohol-fed mice and in patients with AH.67 Another exosome-associated miRNA, miR-192, was used as a prognostic marker for ALD. Based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, EV miRNA-192 can be used with an accurate diagnostic test of 0.95 (P < 0.001) in discriminating liver disease from healthy controls.67 Furthermore, a recent study by Sherawat et. al identified EV sphingolipid cargo as a prognostic performance biomarker for AH.136 Similarly, in NASH, a recent study identified the cell source of EVs in circulation and observed an increase in hepatocyte derived EVs in the progression of murine models of NASH.137 Furthermore, proteomic analysis of EVs of cirrhotic NASH identified 7 proteins specifically enriched in EVs of NASH patients that may be capable of serving as potential biomarkers.138 In acetaminophen-induced liver injury, Schmelzle et al. showed that CD133-positive microvesicles are selectively increased in patients with liver injury compared to healthy controls, suggesting the potential application of CD133 as a biomarker for APAP-liver injury.139 Two independent studies have also demonstrated the association of miR-122 in protein-rich fractions of plasma (and not in EV-rich fractions) after APAP-induced liver injury, suggesting the exclusion of miR-122 from EVs may also distinguish APAP-induced liver injury from other liver damage.69,140 In HCC, various EV-associated miRNAs are associated with the prognosis of the disease. In a study by Sohn et al., miRNA profiling of serum EVs from patients with cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection, and HCC revealed a unique signature of EV-miRNA including miR-18a, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-224, which were exclusively up-regulated in HCC patients compared to patients with cirrhosis or CHB.141 Another study by Sugimachi et al. identified a direct correlation between decreased levels of EV-associated miR-718 and patients with recurrent HCC after liver transplantation. Indeed, miR-718 suppresses tumor growth and its decreased level in EVs may be used as a potential biomarker to characterize patients with chances of tumor recurrence.142 Table 2 summarizes the potential miRNA and protein-based biomarkers in different liver pathobiology.

TABLE 2.

List of Extracellular vesicle miRNA cargo and protein cargo as a potential biomarker in different liver disease

| Liver disease | Species | Biofluid Source | EV cargo | Levels of cargo | EV subtype | EV isolation method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Mice | plasma | miR-let7f, miR-29a, miR-340 | Increased | Exosomes and microvesicles | ultracentrifugation | 68 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Mice/human | Serum/plasma | miR-155 miR-122 miR-192 |

Increased | Exosomes | Exoquick/precipitation-based method | 67 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Mice | Serum | CD40L, Hsp90 | Increased | Exosomes | Exoquick ultracentrifugation | 73,74 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Human | plasma | Sphingolipids | Increased | Exosomes | ultracentrifugation | 136 |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | Mice | Serum | miR-122 miR-192 |

Increased | Microvesicles | ultracentrifugation | 76 |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | Mice | Serum | CXCL-10 | Increased | Exosomes | ultracentrifugation | 81 |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | Human and Mice | plasma | Ceramides and sphingosine-1-phosphate | Increased | Exosomes | Differential ultracentrifugation | 48 |

| Hepatitis C | Human | Serum | miR-122, miR-134, miR-424–3p, miR 629–5p | Increased | Exosomes | Exoquick | 91,93,156 |

| Drug-induced liver injury | Rat/Mice | Serum | miR-122 miR-192 miR-193a |

Increased | Exosomes | Exoquick | 98,100 |

| Liver fibrosis | Mice | Serum | miR-214 miR199a |

DecreasedIncreased | Exosomes | PureExo Exosome Isolation Kits ultracentrifugation | 114,115 |

| Liver fibrosis | Mice | Serum | CCN2 | Decreased | Exosomes | PureExo Exosome Isolation Kits | 114 |

| HCC | Human | Serum | miR-21 miR-29 |

Increased | Exosomes | Differential ultracentrifugation | 123 |

| HCC | Human | Serum | miR-18a, miR-221, miR-222, miR-224 | Increased | Exosomes | Exoquick | 141 |

| HCC | Human | Serum | miR-718 | Decreased | Exosomes | ultracentrifugation | 142 |

Utilizing EVs in molecular diagnostics is challenging because it requires the standardization of EV isolation protocols and the characterization of biological fluids. Furthermore, establishing stage-specific and liver disease-specific unique cargo signatures is required for the application of EVs in future molecular diagnosis and personalized medicine.

6|. THERAPEUTICAL POTENTIAL OF EVS IN LIVER DISEASE

Extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes, have gained tremendous interest for their therapeutic potential in various processes such as regeneration, Ag presentation, and immunotherapy.143 There are distinct properties of EVs that make them ideal candidates to be used for therapeutics including the availability to isolate from varied sources; the presence of lipid bilayers (which protects the cargo from degradation by enzymes); less immunogenicity; and the ability to carry a wide variety of cargo (that includes miRNA, silencing RNA (siRNA), proteins, and other biologically active agents).143 The use of EVs for therapeutics has a wide spectrum: from using the secretome or purified EVs from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), injecting engineered EVs which are preloaded with miRNA and/or siRNA, to isolating EVs from the bio-engineered cells that can package specific molecules in the EVs in high number.144 In this section, we discuss the available literature in the context of the liver from the above-mentioned range of usage of EVs as therapeutics.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived EVs, because of their immunomodulatory property, possess healing and regenerative effects in several diseases such as myocardial145 ischemia/reperfusion injury, kidney injury, and liver injury.146,147 In the liver, MSC-derived EVs alleviate the progression of CCL4-induced liver fibrosis. MSC-EVs exert their hepatoprotective effect by increasing the expression of proliferation proteins (PCNA and cyclin D1).148 Recently, studies have explored the role of EVs obtained from different sources (including human liver stem cell (HLSCs) derived EVs, EVs from healthy hepatocytes, and EVs from the serum of healthy controls) as therapeutics for attenuating liver fibrosis in pre-clinical models.145,149,150 Human liver stem cell (HLSCs) derived EVs, when injected into murine models of NASH, are taken up by the liver and attenuate liver fibrosis and inflammation.145 Healthy hepatocyte-derived EVs and serum-derived EVs, when used as an intervention in the CCL4-induced liver fibrosis model, cause a reduction in fibrosis and potentiate reduced hepatocyte cell death and inflammation.149,150

Some recent studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of EVs packaged with specific miRNA in preventing liver fibrosis and autoimmune hepatitis.151,152 Indeed, bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cell (BMSCs)-derived EVs are abundant in miR-223 and can reverse liver injury in murine models of autoimmune hepatitis. Mechanistically, BMSCs-EVs loaded with miR-223 down-regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines, NLRP3 and caspase-1, and are thus beneficial in reducing liver injury.152 In another study, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) were engineered to package miR-181–5p in their EVs. ADSCs-EV loaded with miR-181–5p down-regulated Stat3 and Bcl-2 in recipient cells and activated autophagy, which lead to reduced activation of hepatic stellate cells and, by extension, ameliorated liver fibrosis.151 Another interesting therapeutic application of EVs is their ability to deliver antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) to target organs. Indeed, Bala et. al. showed that in vitro B-cell derived EVs loaded with a synthetic miR-155 mimic and an miR155 inhibitor, are taken up by both Mϕs and hepatocytes. The miR-155 synthetic mimic and inhibitor were functionally active and effectively decreased TNF-α production in Mϕs upon stimulation. Furthermore, when B-cell derived EVs loaded with miR-155 mimic were injected into the miR-155 KO mice, there was an accumulation of miR-155 in plasma, more so in the liver, followed by adipose tissue, lung, muscle, and kidney.153 Recently, Zhang et. al reported that RBC-EVs are phagocytosed by Mϕs in a C1q-dependent manner and accumulate in the liver after intravenous injection. Furthermore, RBC-EVs with miR-155 ASO protect the mice from acute liver failure by increasing the M2 Mϕ population.154

EVs can also be selectively enriched in biologically active molecules by engineering the cells producing EVs. A recent study engineered human umbilical cord perivascular cells (HUCPVCs) to produce Insulin Growth Factor like-1 by using adenovirus. Indeed, HUCPVCs-IGF-1-derived EVs reduced collagen deposition and decreased gene expression of the fibrogenic related molecules. They also promoted the anti-inflammatory phenotype of hepatic Mϕs and attenuated liver fibrosis.155 However, there are some caveats to using EVs as therapeutics: challenges of EV yield, stability, targeting and uptake by specific cell type; and increased delivery of cargo content. Future research in this field may pave a way for overcoming these challenges and improve the targeted delivery of EVs, making them a stronger therapeutic candidate in the future.

7|. CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Extracellular vesicles comprise different biologically active cargo molecules including DNA, protein, lipids, and small non-coding RNAs. EVs act as important mediators of cell-cell communication, but the exact mechanism by which EVs target specific cells, the miRNAs that are packaged into them, and the target pathways that affect their uptake in recipient cells and subsequent signaling cascades are still under investigation. EVs alter the immune response in recipient cells and play an important role in the progression and pathogenesis of liver diseases. Finally, circulating EVs promote inter-organ crosstalk and contribute to systemic abnormalities. Specific EV cargo under different diseased conditions and stages provides invaluable information and should be investigated as EV-based diagnostic methodologies. Using engineered EVs to express certain ligands or exploiting them for delivering nucleic acid and drugs make EVs an important potential therapeutic target.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Olivia Potvin for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Gyongyi Szabo is the Editor-in-Chief of Hepatology Communication. She also consults for Allegran, Ainylam, Arrow, Durcet Corporation, Generon, Glympse Bio, Terra Firma, Quest, Pandion Therapeutics, Surrozen, and Zomagen. She has received grants from Gilead, Genfit, Intercept, Novartis, SignaBlok, and Shire. She holds intellectual property rights with Up to Date. The co-authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations:

- Ago2

argonaute

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AP-2

adaptor-related protein complex 2

- APAP

acetaminophen

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotides

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMSCs

bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells

- CAF

cancer associated fibroblasts

- Cav-1

caveolin-1

- CCN2

connective tissue growth factor

- CD40L

CD40 ligand

- CDAA

choline deficient L-amino acid

- CXCL10

C-X-C motif ligand 10

- DR5

death receptor 5

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial mesenchymal transition

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- ERK

extracellular signal-related kinase

- ESCRT

endosomal sorting complexes required for transport

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- H/R

hypoxia/reperfusion

- HAV

hepatitis A virus

- HBV

hepatitis B Virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HLSCs

human liver stem-like cells

- hnRNP

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- HuR

human antigen R

- ILVs

interluminal vesicles

- IRE1

inositol requiring protein-1

- KCs

Kupffer cells

- KLF4

Kruppel-like factor 4

- KRAS

Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- LAMP

lysosomal associated proteins

- LBPA

lysobisphosphatidic acid

- LSECs

liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

- MDSCs

myeloid derived suppressor cels

- MEK

mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MEX3C

MEX-3 RNA-binding family member C

- miRNA

microRNA

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cells

- mTOR

mechanistic targets of rapamycin

- MVBs

multivesicular bodies

- MVP

major vault protein

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- nSMase 2

Neutral sphingomyelinase 2

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PHLPP2

PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase 2

- PS

phosphatidyl serine

- Rheb

Ras homolog enriched in brain

- RIG-1

receptor retinoic acid inducible gene-I

- RISC

RNA induced silencing complex

- ROC

receiver operating characteristics

- ROCK1

Rho-associated, coiled-coil containing protein kinase-1

- SHP-2

Src homology 2 domain tyrosin phosphatase 2

- TEP1

Telomerase- associated protein 1

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- VNN1

Vannin 1

- Vps4A

Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4

- YBX-1

Y-Box binding protein 1

REFERENCES

- 1.Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding CV, Heuser JE, Stahl PD. Exosomes: looking back three decades and into the future. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo G, Momen-Heravi F. Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:455–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoorvogel W, Kleijmeer MJ, Geuze HJ, Raposo G. The biogenesis and functions of exosomes. Traffic. 2002;3:321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caruso S, Poon IKH. Apoptotic Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: more Than Just Debris. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:332–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabo G, Bala S. MicroRNAs in liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bala S, Szabo G. MicroRNA Signature in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:498232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalra H, Simpson RJ, Ji H, et al. Vesiclepedia: a compendium for extracellular vesicles with continuous community annotation. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, et al. ExoCarta: a Web-Based Compendium of Exosomal Cargo. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreyfuss G, Kim VN, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groot M, Lee H. Sorting Mechanisms for MicroRNAs into Extracellular Vesicles and Their Associated Diseases. Cells. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabbiano F, Corsi J, Gurrieri E, Trevisan C, Notarangelo M, D’agostino VG. RNA packaging into extracellular vesicles: an orchestra of RNA-binding proteins?. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;10:e12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villarroya-Beltri C, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Sánchez-Cabo F, et al. Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Li C, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Otterbein LE, Jin Y. Caveolin-1 selectively regulates microRNA sorting into microvesicles after noxious stimuli. J Exp Med. 2019;216:2202–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pérez-Boza J, Boeckx A, Lion M, Dequiedt F, Struman I. hnRNPA2B1 inhibits the exosomal export of miR-503 in endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:4413–4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaguer N, Moreno I, Herrero M, González M, Simón C, Vilella F. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C1 may control miR-30d levels in endometrial exosomes affecting early embryo implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2018;24:411–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vilella F, Moreno-Moya JM, Balaguer N, et al. Hsa-miR-30d, secreted by the human endometrium, is taken up by the preimplantation embryo and might modify its transcriptome. Development. 2015;142:3210–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Dong X, Chen Y, Wang X. Serum exosomal hnRNPH1 mRNA as a novel marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;56:479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santangelo L, Giurato G, Cicchini C, et al. The RNA-Binding Protein SYNCRIP Is a Component of the Hepatocyte Exosomal Machinery Controlling MicroRNA Sorting. Cell Rep. 2016;17:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobor F, Dallmann A, Ball NJ, et al. A cryptic RNA-binding domain mediates Syncrip recognition and exosomal partitioning of miRNA targets. Nat Commun. 2018;9:831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schug J, Mckenna LB, Walton G, et al. Dynamic recruitment of microRNAs to their mRNA targets in the regenerating liver. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, et al. MicroRNA-194 acts as a prognostic marker and inhibits proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting MAP4K4. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:12446–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eliseeva IA, Kim ER, Guryanov SG, Ovchinnikov LP, Lyabin DN. Y-box-binding protein 1 (YB-1) and its functions. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2011;76:1402–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin F, Zeng Z, Song Y, et al. YBX-1 mediated sorting of miR-133 into hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced EPC-derived exosomes to increase fibroblast angiogenesis and MEndoT. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shurtleff MJ, Temoche-Diaz MM, Karfilis KV, Ri S, Schekman R. Y-box protein 1 is required to sort microRNAs into exosomes in cells and in a cell-free reaction. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mckenzie AJ, Hoshino D, Hong NH, et al. KRAS-MEK Signaling Controls Ago2 Sorting into Exosomes. Cell Rep. 2016;15:978–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cha DJ, Franklin JL, Dou Y, et al. KRAS-dependent sorting of miRNA to exosomes. Elife. 2015;4:e07197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simone LE, Keene JD. Mechanisms coordinating ELAV/Hu mRNA regulons. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukherjee K, Ghoshal B, Ghosh S, et al. Reversible HuR-microRNA binding controls extracellular export of miR-122 and augments stress response. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1184–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y, Wang Z, Zhu X, et al. Exosomal miR-1246 in serum as a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchet-Poyau K, Courchet J, Hir HL, et al. Identification and characterization of human Mex-3 proteins, a novel family of evolutionarily conserved RNA-binding proteins differentially localized to processing bodies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He M, Qin H, Poon TCW, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma-derived exosomes promote motility of immortalized hepatocyte through transfer of oncogenic proteins and RNAs. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:1008–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu P, Li H, Li N, et al. MEX3C interacts with adaptor-related protein complex 2 and involves in miR-451a exosomal sorting. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berger W, Steiner E, Grusch M, Elbling L, Micksche M. Vaults and the major vault protein: novel roles in signal pathway regulation and immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H, Li M, He R, et al. Major Vault Protein Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through Targeting Interferon Regulatory Factor 2 and Decreasing p53 Activity. Hepatology. 2020;72:518–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szaflarski W, Sujka-Kordowska P, Pula B, et al. Expression profiles of vault components MVP, TEP1 and vPARP and their correlation to other multidrug resistance proteins in ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan Y-K, Zhang H, Liu P, et al. Proteomic analysis of exosomes from nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell identifies intercellular transfer of angiogenic proteins. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1830–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Admyre C, Johansson SM, Qazi KR, et al. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J Immunol. 2007;179:1969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buschow SI, Balkom BWM, Aalberts M, Heck AJR, Wauben M, Stoorvogel W. MHC class II-associated proteins in B-cell exosomes and potential functional implications for exosome biogenesis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teng Y, Ren Yi, Hu X, et al. MVP-mediated exosomal sorting of miR-193a promotes colon cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campos A, Burgos-Ravanal R, González M, Huilcaman R, Lobos González L, Quest A. Cell Intrinsic and Extrinsic Mechanisms of Caveolin-1-Enhanced Metastasis. Biomolecules. 2019;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shamseddine AA, Airola MV, Hannun YA. Roles and regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 in cellular and pathological processes. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17442–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Hagiwara K, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Ochiya T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-dependent exosomal transfer of angiogenic microRNAs regulate cancer cell metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10849–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakazu E, Mauer AS, Yin M, Malhi H. Hepatocytes release ceramide-enriched pro-inflammatory extracellular vesicles in an IRE1alpha-dependent manner. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:233–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colombo M, et al. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5553–65. Pt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maity S, Caillat C, Miguet N, et al. VPS4 triggers constriction and cleavage of ESCRT-III helical filaments. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaau7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akrap I, Thavamani A, Nordheim A. Vps4A-mediated tumor suppression upon exosome modulation?. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei J-X, Lv Li-H, Wan Y-Le, et al. Vps4A functions as a tumor suppressor by regulating the secretion and uptake of exosomal microRNAs in human hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 2015;61:1284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hurley JH, Odorizzi G. Get on the exosome bus with ALIX. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:654–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larios J, Mercier V, Roux A, Gruenberg J. ALIX- and ESCRT-III-dependent sorting of tetraspanins to exosomes. J Cell Biol. 2020;219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iavello A, Frech VSL, Gai C, Deregibus MC, Quesenberry PJ, Camussi G. Role of Alix in miRNA packaging during extracellular vesicle biogenesis. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:958–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Niel G, D’angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malhi H Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;317:G739–G749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nazarenko I, Rana S, Baumann A, et al. Cell surface tetraspanin Tspan8 contributes to molecular pathways of exosome-induced endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1668–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen T-L, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]