Abstract

Affective and non-affective psychotic disorders are associated with variable levels of impairment in affective processing, but this domain typically has been examined via presentation of static facial images. We compared performance on a dynamic facial expression identification task across six emotions (sad, fear, surprise, disgust, anger, happy) in individuals with psychotic disorders (bipolar with psychotic features [PBD]=113, schizoaffective [SAD]=163, schizophrenia [SZ]=181) and healthy controls (HC; n=236) derived from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). These same individuals with psychotic disorders were also grouped by B-SNIP-derived Biotype (Biotype 1 [B1]=115, Biotype 2 [B2]=132, Biotype 3 [B3]=158), derived from a cluster analysis applied to a large biomarker panel that did not include the current data. Irrespective of the depicted emotion, groups differed in accuracy of emotion identification (P<0.0001). The SZ group demonstrated lower accuracy versus HC and PBD groups; the SAD group was less accurate than the HC group (Ps<0.02). Similar overall group differences were evident in speed of identifying emotional expressions. Controlling for general cognitive ability did not eliminate most group differences on accuracy but eliminated almost all group differences on reaction time for emotion identification. Results from the Biotype groups indicated that B1 and B2 had more severe deficits in emotion recognition than HC and B3, meanwhile B3 did not show significant deficits. In sum, this characterization of facial emotion recognition deficits adds to our emerging understanding of social/emotional deficits across the psychosis spectrum.

Keywords: emotion, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder with psychotic features

Introduction

Successful human interactions depend in part on non-verbal signals, including the ability to accurately identify facial emotion expressions. Deficits in this crucial function are detectable and consistent in individuals with schizophrenia (SZ) (Kohler et al., 2010; Ruocco et al., 2014), which may contribute to impaired interpersonal functioning (Couture et al., 2006). Such problems appear to precede illness onset, are present in family members at familial risk for schizophrenia (Eack et al., 2010) and persist throughout the course of illness (Comparelli et al., 2013). Facial emotion recognition deficits may therefore be a trait marker (Daros et al., 2014) or vulnerability indicator (Comparelli et al., 2013) for the disorder. Individuals with bipolar disorder also display diminished facial emotion recognition regardless of type (type I vs. type II) (Martino et al., 2011; Summers et al., 2006) and state of illness (manic, psychotic or euthymic) (Rocca et al., 2009; Samame et al., 2012; Thaler et al., 2013a). Studies also indicate that individuals with schizoaffective disorder (SAD) show this impairment (Fiszdon et al., 2007). These common deficits across diagnoses [SZ, SAD, and bipolar disorder with history of psychosis (PBD)] suggest similar dysfunction in underlying neural systems for facial emotion face processing. However, when comparing individuals with SZ and PBD for accuracy at identifyng specific kinds of emotional faces (e.g., sadness, happiness), individuals with SZ appear to show greater impairment across recognition of emotion types such as sadness, fear, and anger relative to patients with bipolar disorder (Goghari and Sponheim, 2013; Ruocco et al., 2014). This may mean differences in neural system alterations between the groups, though the mixed findings on specific emotion recognition deficits in the literature renders it difficult to speculate on what such differences may be and point to a need for more research.

An important caveat of prior studies is that the stimuli are of static faces. Considering the mixed results, a key to advancing our understanding of emotion processing within the psychosis spectrum is to move beyond the use of static face tasks and use dynamic face tasks. Dynamic facial emotion tasks are ecologically valid (Bernstein and Yovel, 2015) and may account for the heterogeneity in the degree and pattern of facial emotion recognition impairment within and across the diagnostic groups. In healthy individuals, dynamic emotional expressions were recognized more accurately than static ones (Darke et al., 2019). In another study involving a small group of individuals with SZ, static and dynamic emotional face recognition tasks assessing only fear and surprise were differentially associated with psychotic symptoms (Johnston et al., 2010).

An additional limitation in prior research was the lack of control for overall cognitive function when comparing facial emotion recognition deficits among diagnostic groups. One study on a large sample of healthy individuals showed that there are shared factors underlying general cognitive function and emotion recognition, especially in terms of processing speed (Mathersul et al., 2009). Previous research in psychiatrically ill groups reported the correlation between facial affect recognition and cognition (Goghari and Sponheim, 2013; Ruocco et al., 2014), but they did not statistically control for such relationships when comparing emotion recognition deficits. Since individuals with SZ have more impaired cognitive function (Hill et al., 2013), this may account for the more extensive deficits across emotions compared to individuals with PBD. A more refined analysis is needed to better understand the emotion recognition pattern within psychosis, including the possibility that SAD occupies a middle ground of impairment between SZ and PBD.

The majority, if not all, of the prior work that compares emotion functions in individuals with psychosis also focuses on differences across the DSM diagnostic boundaries of SZ, SAD, and PBD. The overlap of neurobiology and clinical presentation across these diagnoses has led to a paradigm shift towards a transdiagnostic framework (Insel et al., 2010; Morris and Cuthbert, 2012) and efforts to classify patients based on neurobiological features. The Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network for Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) has contributed to this evidence base and perspective in the area of psychotic disorders. Using a large biomarker database (EEG, eye tracking, and cognition), three clusters (i.e. Biotypes) emerged from a group of individuals with psychosis (diagnoses included SZ, SAD, and PBD) (Clementz et al., 2016; Mothi et al., 2018) that have since been replicated and validated (Clementz et al., 2021). The biotype partition does not respect diagnostic boundaries as every biotype group consisted of a mixed number of SZ, SAD, and PBD probands. Biotype-1 and Biotype-2 show marked deficits on general cognitive ability as measured by the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (Keefe et al., 2004; Keefe et al., 2008). Biotype-1’s defining features are deficient neural activations and slowed response latencies. Biotype-2’s defining features are greater deviation on cognitive tasks that require inhibitory control in sensorimotor performance and excessive nonspecific neural activity. Biotype-3 cases are similar to healthy participants on biomarker features. The heterogeneity of neurobiological functioning within SZ, SAD or PBD may contribute to the mixed findings of specific emotion recognition deficits in prior work, which inspired the current study to examine emotion recognition performance transdiagnostically, across the three Biotypes. Notably, emotion processing features were not considered or used in biotype classification.

Here we aim to address some of the inconsistencies in the literature on emotional face processing deficits in psychosis by comparing performance on a dynamic facial emotion recognition task among (1) three diagnostic groups (i.e. SZ, SAD, and PBD) and (2) three Biotypes to one another and to healthy controls (HC), with data available from the B-SNIP2 study. We focused on the accuracy and latency of recognizing facial emotions and assessed whether these deficits are distinct from generalized cognitive deficits. With respect to diagnostic groups, we expected that each diagnostic group would perform worse than HC and that individuals with SZ would perform significantly worse than the other diagnostic groups, as well as show emotion-specific deficits consistent with Ruocco et al (2014). We further predicted cognition could account for at least some of the emotion processing differences noted. We next compared the sample when organized by BSNIP Biotype group. We expected that Biotype-1 and −2 would perform worse than Biotype-3 and HC, consistent with membership in these groups being determined partly by cognitive ability. Emotion-specific deficits were exploratory for Biotypes, and were conducted to determine if such findings may further refine what distinguishes Biotype groups. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a dynamic versus static dynamic facial emotion recognition task to assess emotion recognition functioning across diagnostic groups as well as the three B-SNIP Biotypes.

Methods

Participants

Study participants included individuals with SZ (n=181), SAD (n=163), PBD (n=113), and HC (n=236) from the B-SNIP2 multisite study (Table 1). Full details on study recruitment and procedures are available in Tamminga et al. (2013) as B-SNIP2 procedures were the same as in B-SNIP1. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses were made at consensus meetings using all available information including findings from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV)(First, 2002) administered by trained clinical raters who held monthly inter-site reliability conference calls (Tamminga et al., 2013). All individuals with psychosis were on stable medication with no major changes in the past 30 days. HC had no history of a psychotic disorder or recurrent mood disorder, and no known close relatives with these disorders. Participants with an available Biotype classification (N=405) were also separated into Biotype groups (B1, B2, B3) using a method reported previously (Clementz et al., 2016; Mothi et al., 2018) (Table 2). Exclusion criteria included: history of head injury with loss of consciousness >10 minutes; pregnancy; positive urine toxicology screen for drugs of abuse on the day of testing; diagnosis of substance abuse in the past 30 days or substance dependence in the past 3 months; history of systemic medical or neurological disorder affecting mood or cognition; or intellectual disability.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for individuals with schizophrenia (SZ), schizoaffective disorder (SAD), psychotic bipolar disorder (PBD) and healthy control (HC) participants.

| SZa (n=181) M (SD) | SADb (n=163) M (SD) | PBDc (n=113) M (SD) | HCd (n=236) M (SD) | Post Hoc† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.1 (11.4) | 40.4 (10.8) | 38.1 (11.6) | 34.4 (12.6) | a, b, c >d |

| WRAT | 90.2 (14.4) | 93.0 (14.8) | 98.0 (14.9) | 99.6 (12.9) | a, b < d, c |

| Male, n (%) | 97 (54) | 71 (44) | 51 (45) | 99 (42) | a > b, c, d |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 49 (27) | 51 (31) | 58 (52) | 94 (40) | c, d > a, b |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 92 (51) | 64 (39) | 28 (25) | 68 (29) | a > b > c, d |

| Other/Hispanic | 40 (22) | 48 (29) | 27 (24) | 74 (31) | - |

| PANSS | |||||

| Positive subscale | 16.9 (6.0) | 18.5 (6.7) | 14.8 (6.2) | - | b > c |

| Negative subscale | 16.0 (6.1) | 16.1 (7.1) | 14.7 (6.5) | - | - |

| YMRS | 9.9 (6.2) | 11.8 (7.3) | 9.7 (8.6) | - | - |

| MADRS | 9.7 (8.6) | 15.1 (10.8) | 15.8 (11.8) | - | a < b, c |

| CPZ equivalents, median (IQR) | 337 (365) | 337 (357) | 237 (327) | - | - |

| Medications with anticholinergic properties, median (IQR) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | - | - |

| Medications | |||||

| Any antipsychotic | 139 (77) | 124 (76) | 78 (69) | 0 (0) | - |

| Any psychotropic | 151 (84) | 142 (87) | 102 (90) | 11 (5) | - |

| Any antidepressant | 73 (41) | 82 (50) | 55 (49) | 4 (2) | - |

| Any mood stabilizer | 34 (19) | 74 (45) | 70 (62) | 3 (1) | c > b > a |

| Lithium | 6 (3) | 20 (12) | 25 (22) | 0 (0) | c > b > a |

| Any anticonvulsant | 28 (15) | 67 (41) | 56 (50) | 3 (1) | c, b > a |

| Anxiolytic/sedatives/hypnotic | 22 (12) | 29 (18) | 35 (31) | 3 (1) | c > a, b |

| Anticholinergic/antiparkinsonian | 33 (18) | 19 (12) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | a, b > c |

| Stimulant | 3 (2) | 6 (4) | 10 (9) | 2 (1) | c > a, b |

| Any analgesic/anti-inflammatory/muscle relaxants | 29 (16) | 49 (30) | 23 (20) | 22 (9) | b > c > a |

Note. WRAT=Wide Range Achievement Test-IV: Reading test; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS=Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale;

Post hoc tests were computed when the omnibus F-test, Kruskal-Wallis, or χ2 was significant at P<0.05; For medication data, group comparisons are only made between diagnostics groups.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by Biotype and healthy control (HC) participants.

| Biotype 1a (n=115) M (SD) | Biotype 2b (n=132) M (SD) | Biotype 3c (n=158) M (SD) | HCd (n=236) M (SD) | Post Hoc† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.6 (10.4) | 40.4 (10.4) | 39.3 (11.9) | 34.4 (12.6) | a, b, c, > d |

| WRAT | 86.8 (13.5) | 91.2 (14.3) | 99.7 (14.2) | 99.6 (12.9) | a , b < c, d |

| Male, n (%) | 99 (42) | 55 (48) | 44 (33) | 91 (42) | c < a, d < b |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 94 (40) | 29 (25) | 43 (33) | 94 (40) | b, c < a, d |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 68 (29) | 60 (52) | 54 (41) | 68 (29) | b > c > a, d |

| Other/Hispanic | 74 (31) | 26 (23) | 35 (26) | 73 (31) | - |

| PANSS | |||||

| Positive subscale | 18.9 (6.7) | 18.1 (7.0) | 14.9 (5.5) | - | a, b > c |

| Negative subscale | 18.7 (6.4) | 16.7 (6.8) | 13.2 (5.6) | - | a, b > c |

| YMRS | 11.7 (7.0) | 11.1 (7.6) | 9.7 (7.5) | - | - |

| MADRS | 15.5 (11.3) | 14.1 (11.0) | 12.0 (10.0) | - | - |

| CPZ equivalents, median (IQR) | 337 (300) | 245 (367) | 337 (370) | - | - |

| Medications with anticholinergic properties, median (IQR) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | - | - |

| Medications | |||||

| Any antipsychotic | 104 (85) | 95 (79) | 111 (69) | 0 (0) | a > c |

| Any psychotropic | 111 (91) | 107 (88) | 137 (85) | 11 (5) | - |

| Any antidepressant | 62 (51) | 58 (48) | 67 (42) | 4 (2) | - |

| Any mood stabilizer | 48 (39) | 46 (38) | 69 (43) | 3 (1) | - |

| Lithium | 14 (11) | 18 (15) | 13 (8) | 0 (0) | - |

| Any anticonvulsant | 41 (34) | 37 (31) | 60 (37) | 3 (1) | - |

| Anxiolytic/sedatives/hypnotic | 28 (23) | 26 (21) | 23 (14) | 3 (1) | - |

| Anticholinergic/antiparkinsonian | 13 (11) | 14 (12) | 23 (14) | 0 (0) | - |

| Stimulant | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 10 (6) | 2 (1) | - |

| Any analgesic/anti-inflammatory/muscle relaxants | 24 (20) | 36 (30) | 30 (19) | 22 (9) | - |

Note. WRAT=Wide Range Achievement Test-IV: Reading test; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS=Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale;

Post hoc tests were computed when the omnibus F-test, Kruskal-Wallis, or χ2 was significant at P<0.05. For medication data, group comparisons are only made between diagnostics groups.

Measures

Emotion Processing and Cognition

The Dynamic Affect Recognition Evaluation Task (DARE) (Bal et al., 2010; Porges, 2016; Porges SW et al., 2007) is a measure of facial affect recognition. Participants view videos of faces (stimuli developed from Cohn-Kanade Action Unit-Coded Facial Expression Database (Cohn et al., 1999) starting with a neutral expression and slowly transitioning into one of the six target emotions (sad, fear, surprise, disgust, anger, happy). The task consists of three phases. In the first phase, six videos are passively viewed (~8 seconds each) to give an example of each affective expression. After each video, a new screen with six emotion labels appeared with the name of the emotion just shown highlighted. In the second phase, six videos were presented, one example of each of the six emotions, to allow the participant to practice the task. This phase could be repeated if needed to ensure understanding of the task requirements. Participants were instructed to push a button as soon as they could identify the emotion being depicted. When the button was pressed, the video stopped, and a new screen appeared with instruction for the participant to select from six emotion labels for the emotion that had been presented. In the third phase (test phase), 36 videos were presented (6 of each emotion) in a randomized order for each participant. As in phase 2, participants press the button and name the emotion from the list presented. The primary outcome measures were percent accuracy for each emotion, and two latency measures: 1) latency to report recognizing the emotion overall, 2) and latency on only correctly identified trials. For cognitive function, the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) Reading Score and BACS battery were administered by certified research assistants. We used the composite score derived from all six BACS subtests to represent global neuropsychological function (Hill et al., 2013; Hochberger et al., 2016; Keefe et al., 2004; Keefe et al., 2008). Direct comparison of BACS among these groups is reported elsewhere in an overlapping sample (Gotra et al., 2020). Our focus here is on whether variance in facial affect processing associates with general cognitive ability.

Clinical Symptoms and Social Function

Clinical symptom assessments were administered by the same trained clinical raters that administered the SCID-IV. Assessments were the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)(Kay et al., 1987), Schizo-Bipolar Scale (SBS) (Keshavan et al., 2011), Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979), and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978). For the PANSS, MADRS, and YMRS, higher scores reflect greater symptoms. On the SBS, higher scores reflect greater similarity to prototypic schizophrenia. Community functioning was assessed with the Birchwood Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (Birchwood et al., 1990); higher scores reflect better functioning.

Medications

A detailed medication history interview was conducted on all participants All prescription and non-prescription medications were classified into pharmacologically-based categories of agents (e.g., antipsychotics, antidepressants, etc). Chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalent doses were computed for each participant to estimate antipsychotic exposure (Andreasen et al., 2010). The estimated anticholinergic potency of each medication was assigned using the updated version of the Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS) which has been previously described (Eum et al., 2017) and used consistently across analyses in B-SNIP (Eum et al., 2021; Eum et al., 2017).

Statistical Analyses

We used propensity score methods to effectively adjust for confounding effects of age, sex, and race/ethnicity (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2); medications were not identified as confounders. Propensity methods were selected over the approach of adjusting for confounding variables using covariates because they simplify analytics to only include the primary predictors in the model. In the overall sample, we used inverse probability weighted (IPW) mixed effects regression analyses (Robins et al., 2000) to examine diagnostic group and Biotype differences on DARE performance. Adding site to the models did not change the pattern of results and therefore was not included as a covariate. Subsequent analyses examining diagnostic group differences added in the BACS composite score as a covariate to determine whether affective processing deficits were significant beyond a generalized cognitive deficit (Hochberger et al., 2016). As the BACS composite was included in the creation of the Biotypes, these analyses were not conducted to examine Biotype differences. Observations were trimmed where the studentized residuals were >|5| to ensure effects were not driven by extreme values (<1% of observations). A false discovery rate (FDR) correction (set at 5%) was completed using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Spearman’s correlations were conducted to examine associations between DARE performance and clinical symptom severity. Significance was defined as P<0.05 (two-sided). Cohen’s d effect sizes of significant effects are reported (small effect = 0.2; medium effect = 0.5; large effect = 0.8)(Cohen, 1992). Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Diagnostic Group Comparisons on DARE Performance

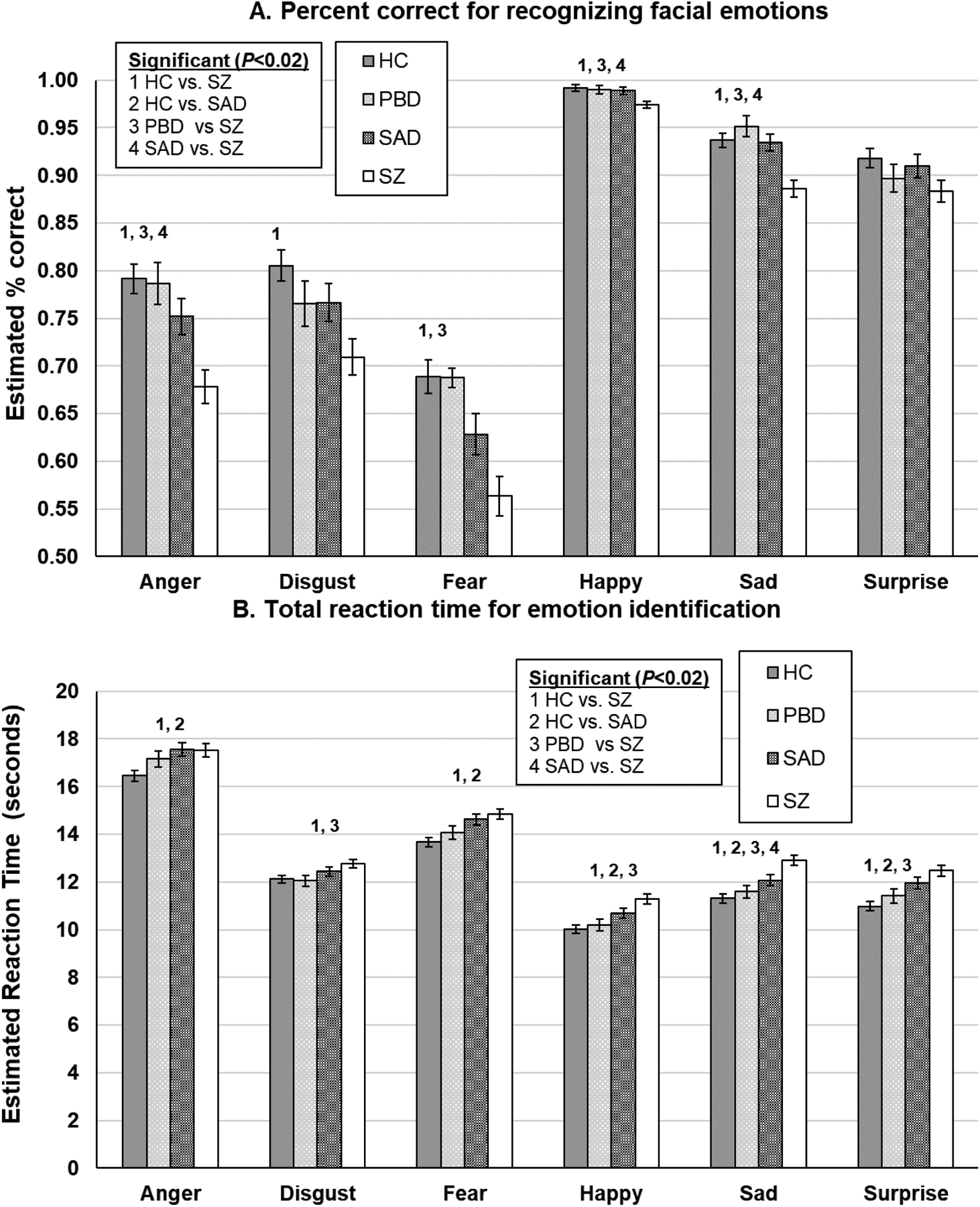

Emotion Recognition Accuracy

Collapsing across all emotions, groups differed in terms of emotional expression recognition accuracy (P<0.0001) with SAD and SZ worse than HC (P’s<0.02). Also, the SZ group demonstrated poorer accuracy compared to the SAD and PBD groups (P<0.0001). The overall pattern of group differences was qualified by a significant group by emotion interaction (P=0.0001). The interaction was being driven by the SZ group showing worse accuracy relative to different sets of other groups for five of the six emotion types (Figure 1a). Specifically, following FDR correction, the SZ group demonstrated greater error identifying sad faces compared to all groups (P’s<0.01). For angry and happy faces, the SZ group demonstrated greater error compared to the HC, PBD, and SAD groups (P’s<0.01). For fear, the SZ group demonstrated greater error compared to the HC and PBD groups (P’s<0.01), and for disgust, the SZ group was worse than only the HC group (P=0.0001). There were no group differences in accuracy of recognizing surprise after FDR correction.

Figure 1.

DARE performance (error bars indicate the standard error of the mean estimates) by diagnostic groups. *Significant P-values were determined using a false discovery rate correction. HC=healthy controls; PBD=psychotic bipolar disorder; SAD=schizoaffective; SZ=schizophrenia.

Reaction Time for Emotion Identification Overall

Groups differed in the speed of responding to emotional expressions when collapsing across all emotion categories (P<0.0001), with the SZ and SAD groups responding slower than the HC group (P’s<0.01). The SZ group was also slower than the PBD group (P=0.003). Thus, although taking more time to consider increasingly apparent emotion features, the SZ and SAD groups were still particularly impaired. The pattern of group differences was qualified by a significant group by emotion interaction (P<0.001; Figure 1b). Following FDR correction, the SZ group was slower to respond to sad faces compared to the HC, PBD, and SAD groups (P’s<0.01), and the SAD group was also slower than the HC group (P=0.009). For angry and fearful faces, the SZ and SAD groups responded slower than the HC group (P’s<0.01). When asked to recognize happy faces, the SZ group responded slower than the HC and PBD groups (P’s<0.01), and the SAD group also responded slower than the HC group (P=0.01). For surprise faces, the SZ group responded slower compared to the HC and PBD groups (P’s<0.01), and the SAD group also responded slower than the HC group (P=0.002).

Reaction Time for Correct Emotion Identification

There were no overall group differences in the reaction time for correct emotion identification (P=0.44); however, there were group differences as a function of emotion (P<0.0001; Figure 1c). Following FDR correction, the SZ group was significantly slower to respond for correct trials to happy, sad, and surprise faces compared to the HC group (P’s<0.01), and the SAD group was also slower to respond than the HC group on happy and surprise faces (P<0.02). Additionally, the SZ group was quicker to respond than the PBD and SAD groups in correct trials of recognizing anger (P’s<0.01). The SZ and SAD groups were also quicker to respond than the HC group in correct trials of recognizing fear (P’s<0.02).

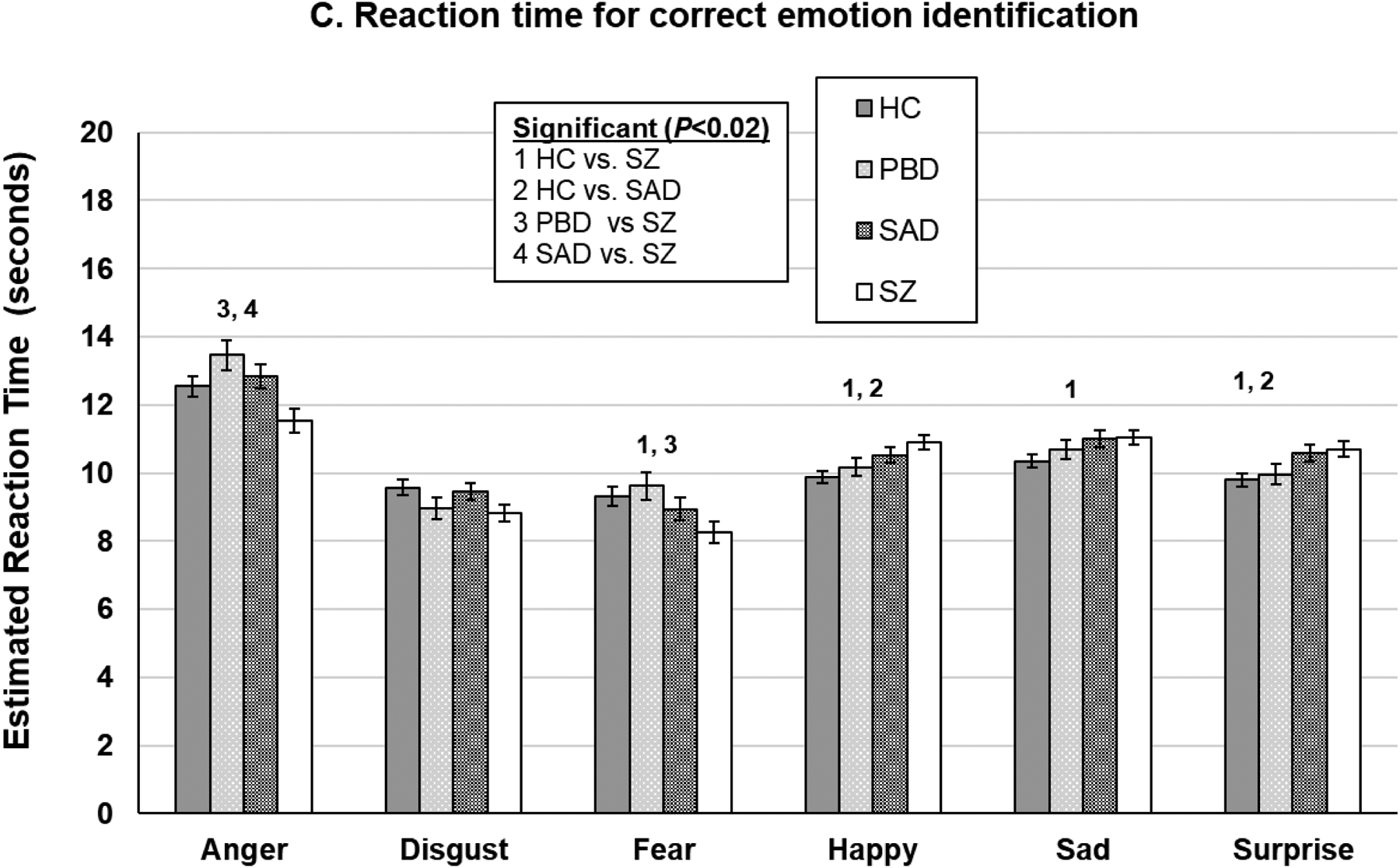

Relation to Generalized Cognitive Deficit

For emotion recognition accuracy, covarying for BACS only eliminated the difference between the SZ and HC groups on happy faces (P=0.04; Figure 2a) and between the SZ and SAD groups on anger, fear, and happy faces (see Supplemental Table 3 for associations between percent accuracy and BACS). Conversely, for total reaction time for emotion identification, covarying for BACS eliminated almost all group differences (Figure 2b). The only differences remaining were that the SZ group was slower than the HC group for sad, happy, and surprise faces (P’s<0.01). The SAD group also remained slower than the HC group for fear (P=0.04). For reaction time for correct trials, covarying for BACS resulted in the SZ group remaining significantly slower than the HC group for happy and surprise faces (P’s<0.05) but quicker on fear faces (P=0.003). The SAD group also remained slower than the HC group for happy faces (P=0.03).

Figure 2.

DARE performance effect sizes before and after accounting for generalized neuropsychological impairment using the BACS. *Significant P-values following a false discovery rate correction. PBD=psychotic bipolar disorder; SAD=schizoaffective; SZ=schizophrenia.

Correlational Analyses with Symptoms

Few correlations were significant between DARE performance metrics and clinical symptoms within each diagnostic group after FDR correction (P<0.02). Among the PBD group only, greater positive symptom severity on the PANSS (P=0.001) and higher burden of manic symptoms (YMRS total score P=0.006) were associated with slower total reaction times (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations between DARE performance (percent correct for recognizing facial emotions, reaction time for emotion identification) and clinical symptoms by diagnostic group and Biotype.

| Diagnostic Group | Biotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBD | SAD | SZ | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Percent correct | ||||||

| PANSS | ||||||

| Negative | −0.13 | −0.16 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Positive | −0.15 | −0.16 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 |

| YMRS | −0.11 | −0.08 | 0.23* | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.00 |

| MADRS | −0.18 | −0.12 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| SBS | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.07 | −0.20 | −0.31*** |

| SFS | −0.12 | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.27** |

| CPZ equivalents | −0.16 | −0.13 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.11 |

| Medications with anticholinergic properties | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.15 | −0.18* | −0.00 | −0.20* |

| RT | ||||||

| PANSS | ||||||

| Negative | 0.21 | 0.21* | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.29* |

| Positive | 0.35** | 0.05 | −0.23* | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| YMRS | 0.30** | −0.02 | −0.25* | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.08 |

| MADRS | 0.23* | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| SBS | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| SFS | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.07 | 0.23* | 0.11 |

| CPZ equivalents | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| Medications with anticholinergic properties | −0.05 | −0.16 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.06 | −0.14 |

Note.

P<0.001;

P<0.01;

P<0.05;

After false discovery rate correction only **/*** are significant. RT=reaction time; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; MADRS=Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale; SBS=Schizo-Bipolar Scale; SFS=Birchwood Social Functioning Scale; PBD=psychotic bipolar disorder; SAD=schizoaffective disorder; SZ=schizophrenia

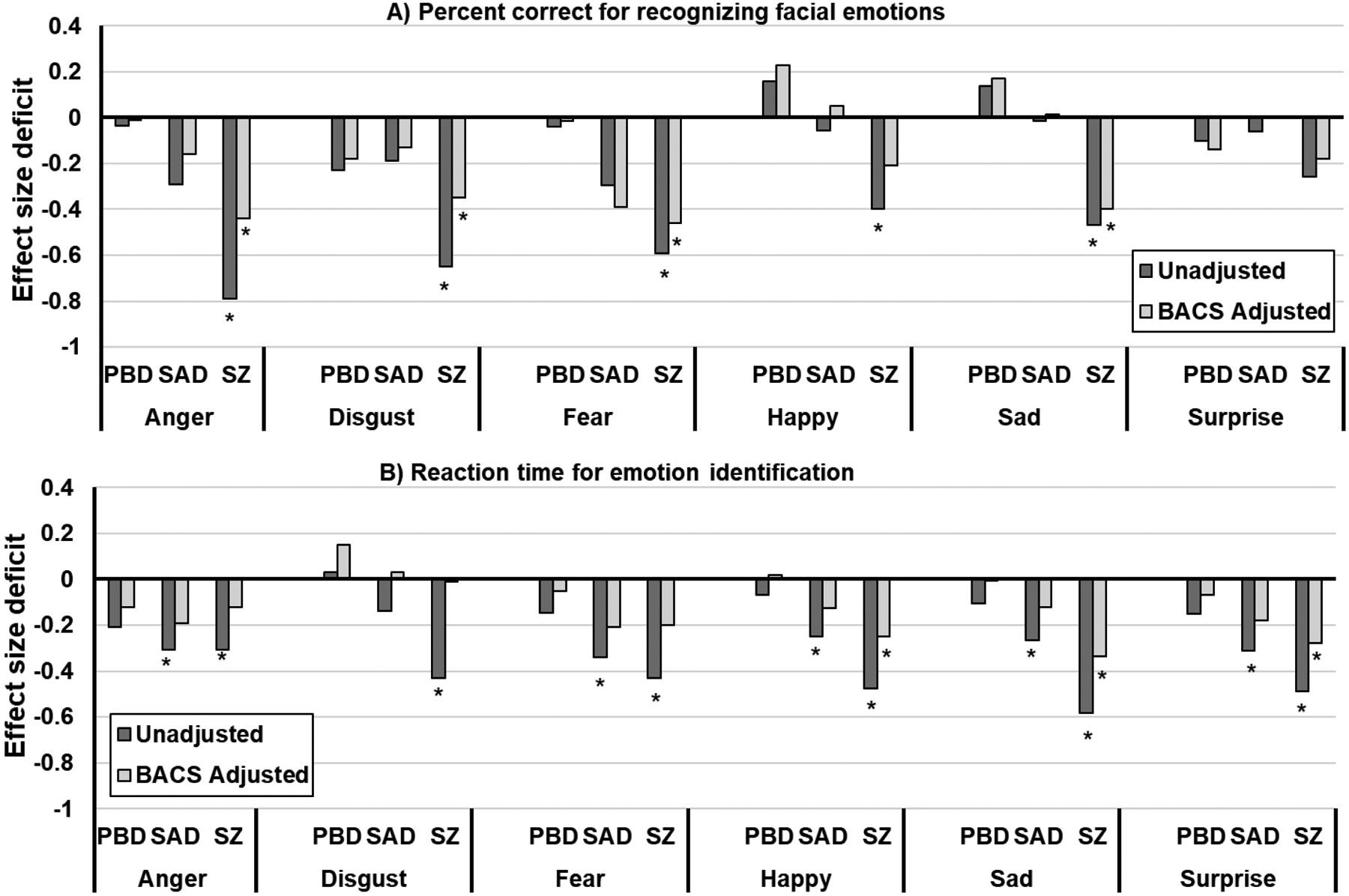

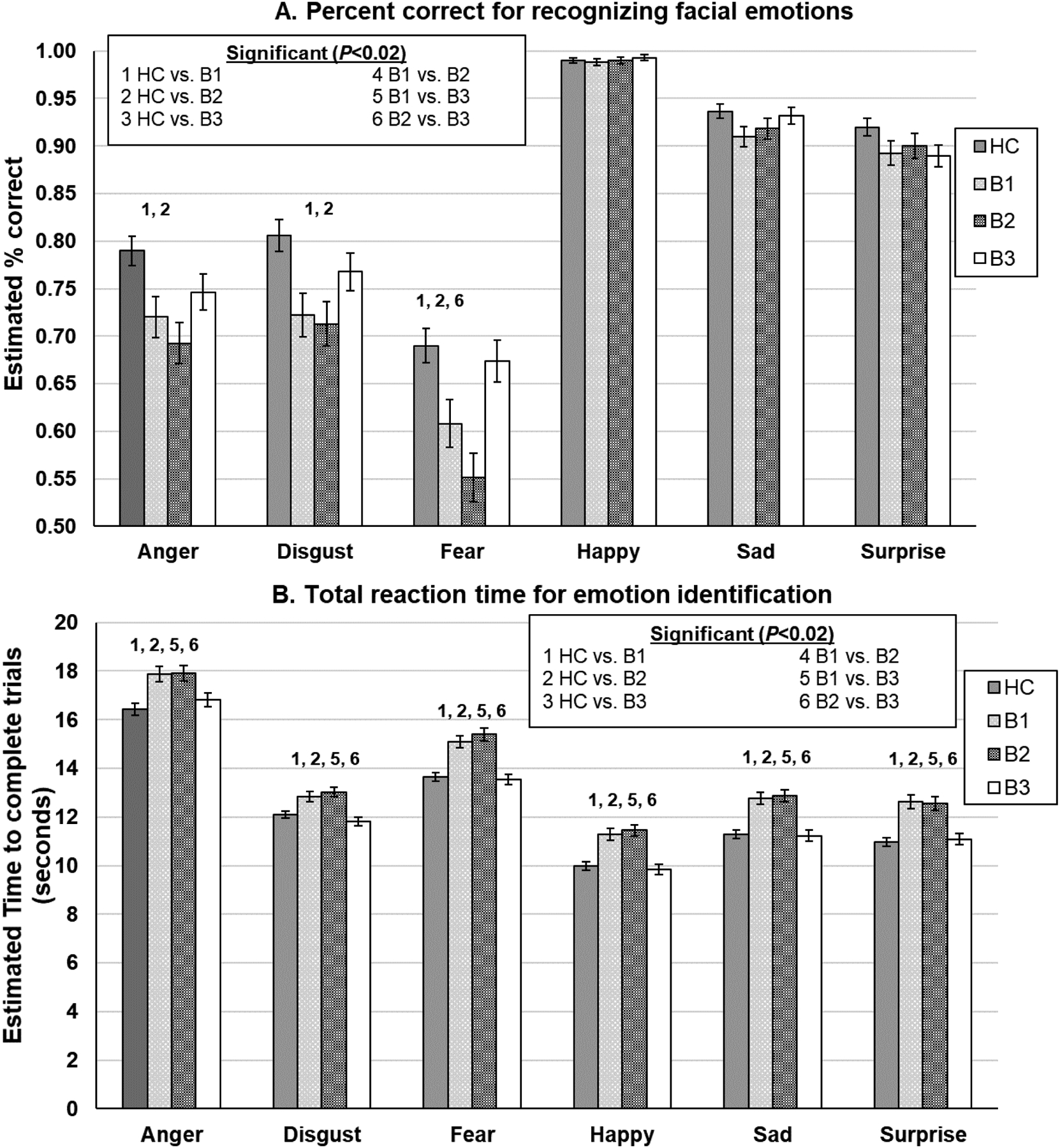

Biotype Comparison on DARE Performance

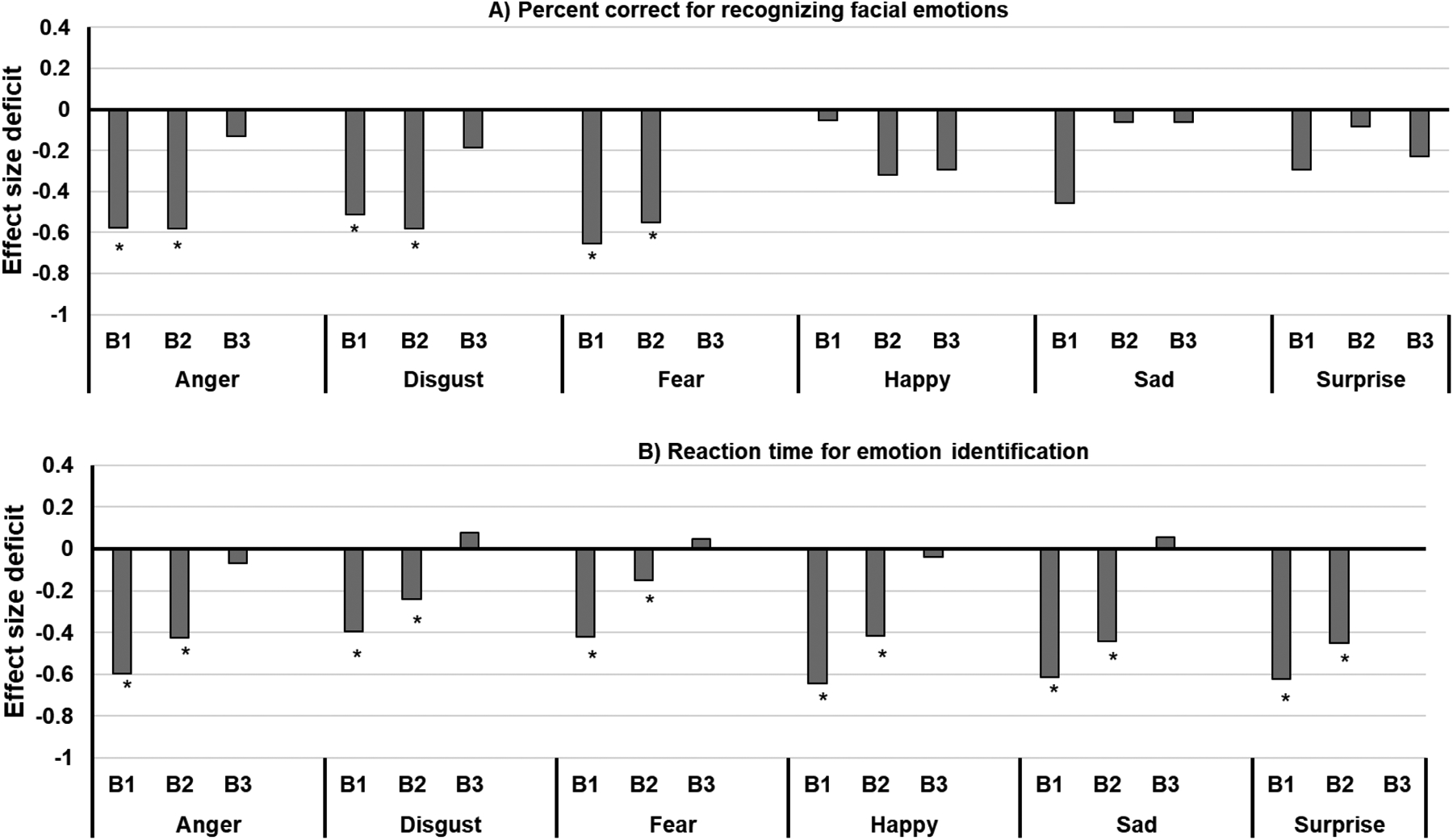

Comparison on Emotion Recognition Accuracy

Biotype groups differed in their correct identification of emotional expressions when collapsing across all emotion categories (P<0.001) with Biotype 1 and 2 correctly identifying fewer emotions than Biotype 3 and HC (P’s<0.05; Cohen’s d1vsHC=−0.65, Cohen’s d2vsHC=−0.45). A different pattern of Biotype group differences emerged as indicated by a significant group-by-emotion category interaction (P=0.0003; Figure 3a; Figure 4a). There were no group differences on correctly identifying happy, sad, or surprise faces. However, compared to HC, Biotypes 1 and 2 demonstrated greater difficulties recognizing anger, disgust, and fear (P’s<0.05). Biotype 2 also demonstrated greater difficulties identifying fear faces compared to Biotype 3 (P’s<0.05).

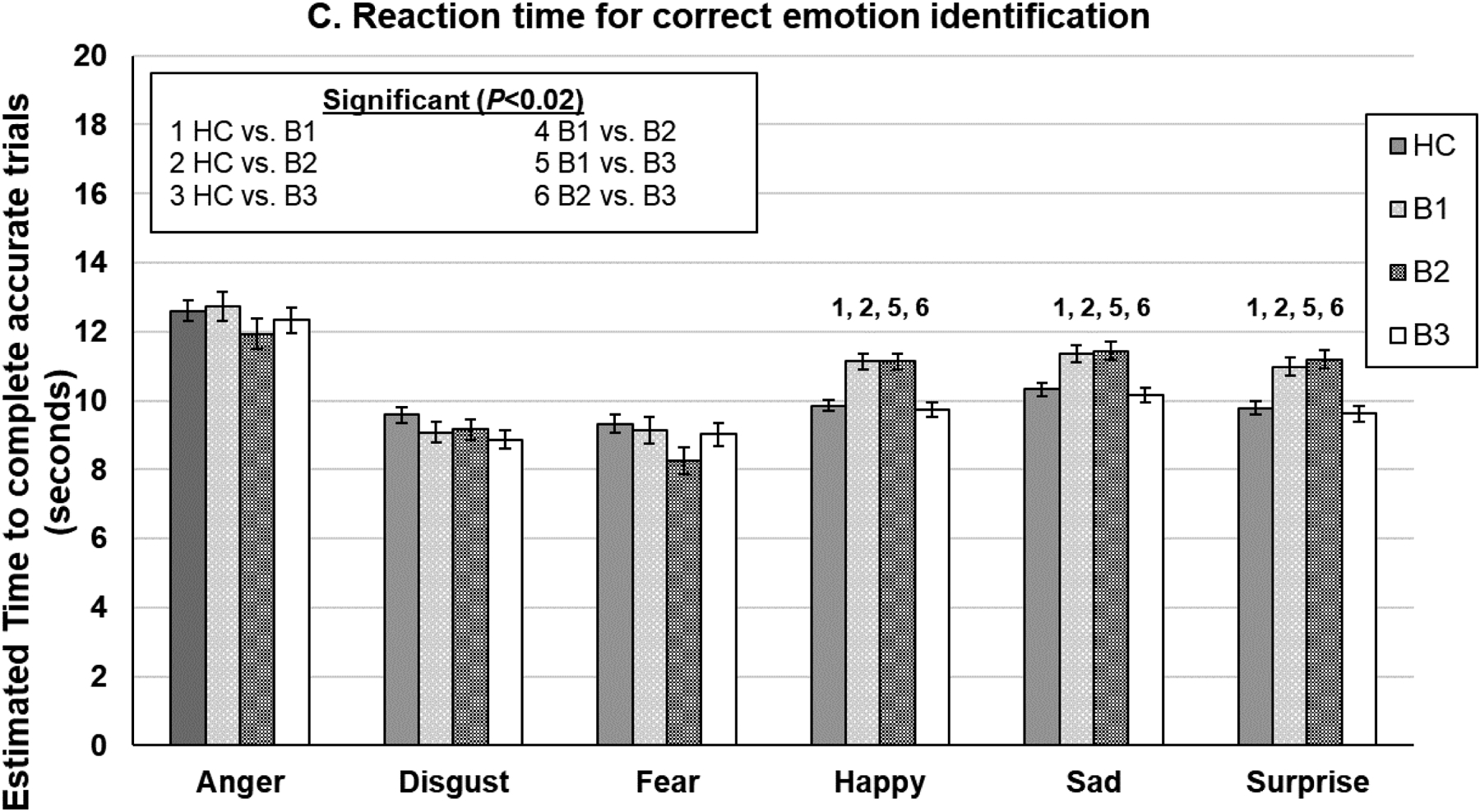

Figure 3.

DARE performance (error bars indicate the standard error of the mean estimates) by Biotype. *Significant P-values were determined using a false discovery rate correction. HC=healthy controls.

Figure 4.

DARE performance effect sizes by Biotype. *Significant P-values following a false discovery rate correction HC=healthy controls; B=Biotype

Reaction Time for Emotion Identification Overall

Groups differed in the speed of identifying emotional expressions when collapsing across all emotion categories (P<0.0001) with Biotypes 1 and 2 responding slower than Biotype 3 (Cohen’s d1vs3=−0.26, Cohen’s d2vs3=−0.36) and HC (P’s<0.0001; Cohen’s d1vsHC=−0.48, Cohen’s d2vsHC=−0.57). The pattern of group differences was qualified by a significant group by emotion interaction (P=0.004; Figure 3b). Although the general pattern was similar across all emotions, the magnitude of group differences differed across emotion (Figure 4b).

Comparison on Reaction Time for Correct Emotion Identification

Groups differed in the speed of responding to emotional expressions when collapsing across all emotion categories (P<0.03) with Biotype 1 and 2 responding slower than Biotype 3 only (P’s<0.05). A different pattern of diagnostic group differences emerged as indicated by a significant group by emotion category interaction (P<0.0001; Figure 3c). Biotypes 1 and 2 were slower to respond than HC and Biotype 3 on happy, sad, and surprise faces (P’s<0.001).

Correlational Analyses with Symptoms

Few correlations were significant between DARE performance metrics and clinical symptoms within Biotype groups after FDR correction (P<0.02) (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study compared facial emotion recognition performance of HC to three psychosis diagnostic groups (SZ, SAD, and PBD) using a dynamic facial recognition task. We found evidence supporting an overall impairment for the SZ group relative to both the HC and to PBD groups, consistent with the other observations of more limited impairment for PBD than SZ. We observed that the SZ group was broadly impaired for accuracy and speed of recognition, while the PBD group did not show significant deficits for either. The SAD group had some deficits with specific emotion subsets relative to the other groups, suggesting a more selective or an intermediate level of impairment. In addition, we explored facial emotion recognition under a transdiagnostic framework by comparing it across the individuals organized into three B-SNIP Biotype groups. We found that the more cognitively impaired Biotype groups - Biotypes-1 and -2 - showed more diminished emotion recognition function compared to Biotype-3 and HC. This is the first study to investigate dynamic facial emotion recognition function both within and beyond the traditional diagnostic boundaries, which offers additional insights on how such deficits appear in psychosis.

The impairment for the SZ group included poorer accuracy and slower speed for all emotional expressions when collapsed. This is consistent with the literature on emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia (Kohler et al., 2010). The impaired accuracy observation replicates our group’s previous report of impaired identification in SZ for all emotions using a static face emotion identification task in an independent sample (Ruocco et al., 2014). We further observed that, except for happy faces, these accuracy deficits were still significant after controlling for general cognitive ability. Hence, the affect recognition inaccuracies appear to be largely independent of well-established general cognitive deficits in SZ (Hochberger et al., 2016; Krabbendam et al., 2005). The relatively low magnitude of correlation between the BACS composite score and emotion recognition accuracy for HC lends support to this interpretation of the functions as showing limited association, a circumstance not apparently altered by the cognitive ability of individuals with SZ. This is consistent with prior reports of facial affect recognition accuracy deficits being relatively unrelated to deficits for non-affective cognitive processing (Barkhof et al., 2015; Chan et al., 2010), such as face perception and identification.

By contrast, when controlling for general cognitive deficit, the slower response time that the SZ group had for almost all emotions was no longer significant, except for happy, sad and surprised faces. For the DARE task, latency scores reflect not only speed, but also the degree of expressiveness faces needed to have for participants to believe they could identify the emotion. Hence, latency scores reflect a mix of sensitivity of facial affect recognition, speed of processing, and decision-making. The BACS composite score is comprised of tests of somewhat overlapping cognitive domains, and so it is not surprising that this measure of general cognitive ability accounted for the majority of the difference between SZ and other groups for DARE latency. However, the slower speed for happy, sad and surprise faces even after accounting for BACS suggests some possible specific deficit for such emotion categories in SZ.

When isolating the reaction time analysis for only correct trials, the SZ group was slower only for the happy, sad and surprise faces, and this was not accounted for by general cognitive deficits. This finding suggests that for individuals with SZ and for a limited group of emotions – happy, sad and surprise - accuracy came at a cost of slower speeds of processing or requirement for a higher strength of facial emotion expressiveness, or a combination of such factors. Interestingly, no such speed-accuracy trade-off was observed for SZ for threatening facial expressions such as disgust, anger and fear. In fact, individuals with SZ even demonstrated a faster speed in correctly recognizing fearful faces than HC. Prior work has suggested increased attentional bias for threatening stimuli in association with paranoia (Kinderman, 1994; Taylor and John, 2004), which may in part explain our observation of more preserved or even enhanced processing for the threatening emotion categories.

Our findings confirmed the notion that SAD and SZ share affect recognition deficits relative to healthy people, and such differences with healthy individuals are not accounted for by general intellectual functioning. However, individuals with SAD have a lesser magnitude of deficit than individuals with SZ (see effect sizes). Individuals with SAD were more accurate than individuals with SZ on sad, angry, and happy faces, though these differences were generally accounted for by cognitive ability. We also observed that while the SAD group performed with less overall accuracy relative to HC across all emotions, effect sizes indicate more substantive deficits for negative, threat-related expressions (fear, anger, disgust), which suggests more dysfunction in or across limbic structures (such as amygdala, insula) where negative/threat emotions are processed (Adolphs R et al., 1999). Finally, we noted that the SAD group had latency deficits, but these were fully accounted for by general cognition, an observation that was not entirely the case for SZ. Our findings are in line with the prior report of the independent B-SNIP1 sample, where groups were distinctive using static emotional faces (Ruocco et al., 2014). One report found that individuals with SZ and SAD had similar patterns of impairment based on recognition accuracy from the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (Fiszdon et al., 2007), but the extent to which such a task is sensitive to similar processes as just facial emotional recogonition is unclear given the broader set of emotion cues in the Bell-Lysaker. These results are interesting in light of speculation that affective disorders and individuals with SAD (arguably an affective illness) may be characterized by greater social-emotional processing abnormality compared to those without affective illness (Ruocco et al., 2014). However, our observations refute this possibility as anything unique to groups with mood disorders, as least in terms of facial affect processing. Rather, SZ appears to have the strongest such impairment and again, the impairment was partly independent of general cognitive deficit for SZ, suggesting SZ is the group where such alterations are the most apparent.

The most surprising findings occurred in the PBD group, who appeared essentially intact for emotion recognition. They had no accuracy and latency deficits relative to HC. However, PBD was the only group with significant clinical associations following FDR correction - slower latency correlated with worse positive symptoms and mania scores in that group only. Hence, their impairments in emotion perception may be more dependent on their current clinical state relative to deficits in schizophrenia spectrum illness. Prior findings on a variety of neurobiological markers have shown PBD to be impaired in a similar pattern as SZ or SAD, but usually to the least degree (Clementz et al., 2016; Tamminga et al., 2013). Here, we show essentially no facial affect recognition impairment in our dynamic facial emotion processing task, which contradicts with several previous studies using static faces (Daros et al., 2014; Ruocco et al., 2014; Thaler et al., 2013a; Thaler et al., 2013b) that found emotion recognition deficits among individuals with PBD relative to HC. We note that the PBD group in the present study had frequent treatment with mood stabilizers and lithium. The possible medication effect on emotion recognition performance has been considered in previous emotion recognition studies, but their impact on task performance remains unclear (Bilderbeck et al., 2017; Hassel et al., 2008; Kucharska-Pietura and Mortimer, 2013; Ruocco et al., 2014). One study showed that the deficits of recognizing certain static emotions did not resolve after treatment for PBD (Daros et al., 2014), and Thaler et al. (2013b) found a significant negative relationship between medication dosage and the audio-visual score on Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test among the PBD group, indicating that participants with worse performance were receiving more medication. However, the authors reported that this relationship was non-linear as individuals achieving high scores had a range of medication doses, and it is unclear whether this is a pharmacological effect or a reflection of an illness severity effect. Regardless, these studies either used a static facial emotion or video clips with audio monologue, which may not predict individuals with PBD’s performance on a dynamic facial emotion task without audio stimuli.

Also of interest was the finding in the emotion recognition performance among the three Biotype groups. Facial emotion recognition patterns largely reflected the characteristics of each Biotype group. The magnitude of the emotion recognition deficits are consistent with the cognitive deficits of the Biotypes: B1 and B2, defined as having reduced cognitive ability, had the most severe emotion recognition impairment, while B3 were almost intact and not surprising had the highest percent of PBD’s. Such a pattern was more evident for latency data: B1 and B2 patients were significantly slower than both HC and B3 patients across every emotion category. For accuracy, both B1 and B2 showed significant deficits in recognizing threatening emotions including anger, disgust, and fear compared to HC, and B2 was worse than B3 in recognizing fearful faces. Though B1 and B2 showed different levels of deficits in inhibitory control (Clementz et al., 2016; Mothi et al., 2018), these groups did not differ within the emotion recognition paradigm. When considering latency for correct trials, the slowness in recognizing threatening faces among B1 and B2 was not significant. Instead, both groups took a longer time correctly recognizing happy, sad, and surprise emotions. It is unclear why B1 and B2 patients take more time in recognizing faces in general but not so in recognizing threatening faces, as research studies in emotion processing in Biotypes are limited. One possible explaination for this discrepancy is that Biotypes have different levels of brain alterations compared to the HC (Clementz et al., 2016; Mothi et al., 2018) or perhaps paranoia-related sensitivity to social threat may contribute to this observation.

There are a few limitations to the current version of the DARE task worth noting. First, participants are not asked to rate their confidence in the accuracy of their responses after each video. Adding this feature to the task may increase its overall clinical utility as greater confidence on social cognition tasks (Penn Emotion Recognition-40, Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test) has been shown to be one of the strongest correlates of social deficits (Pinkham et al., 2018). Moreover, confidence ratings have been found to account for nearly five-fold more variance across tasks than task performance itself (Pinkham et al., 2018) and more strongly correlate with impairments in neuropsychological function than performance on social cognitive tasks in individuals with SCZ (Jones et al., 2020). Second, the current version of the DARE task does not provide a means for assessing response speed variability across harder versus easier items. Other studies demonstrate that individuals with SCZ do not adjust their response times as a function of difficulty in general (Cornacchio et al., 2017). Adding this component into the task may further expand our knowledge in psychosis about the ability to appraise difficulty and adjust effort to the demands placed by social cognitive tasks.

In sum, facial emotion recognition appears to add important information that offers insight into the extent and qualitative features of deficits in the psychosis spectrum. Individuals with PBD, SAD, and SZ showed a slope of progression in emotion recognition deficits, from none to extensive, particularly for accuracy. In terms of Biotype groups, Biotype-1 and Biotype-2 individuals demonstrated more severe emotion recognition deficits, but Biotype 3 was intact, in line with the general neurocognitive characterization of these groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers MH096913, MH096957, MH096942, MH096900; MH077851, MH078113, MH077945, MH077852 and MH077862]. The NIMH had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers MH096913, MH096957, MH096942, MH096900; MH077851, MH078113, MH077945, MH077852 and MH077862]. We would like to thank all of our participants, for without you this work would not be possible.

Conflict of interests:

All authors have declared no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study. Carol A. Tamminga reports the following financial disclosures: American Psychiatric Association - Deputy Editor; Astellas - Ad Hoc Consultant; Autifony - Ad Hoc Consultant; The Brain and Behavior Foundation - Council Member; Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals - Ad Hoc Consultant; Intra-cellular Therapies (ITI, Inc.) - Advisory Board, drug development; Institute of Medicine - Council Member; National Academy of Medicine - Council Member; Pfizer - Ad Hoc Consultant; Sunovion -- Investigator Initiated grant funding. John Sweeney reports the following financial disclosures: Consultant to VeraSci.

Role of Funding Source:

The NIMH had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolphs R, Russell JA, D T, 1999. A Role for the Human Amygdala in Recognizing Emotional Arousal From Unpleasant Stimuli Psychological Science 10(167–71). [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC, 2010. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry 67(3), 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal E, Harden E, Lamb D, Van Hecke AV, Denver JW, Porges SW, 2010. Emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorders: relations to eye gaze and autonomic state. J Autism Dev Disord 40(3), 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhof E, de Sonneville LMJ, Meijer CJ, de Haan L, 2015. Specificity of facial emotion recognition impairments in patients with multi-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn 2(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein M, Yovel G, 2015. Two neural pathways of face processing: A critical evaluation of current models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 55, 536–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilderbeck AC, Atkinson LZ, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Harmer CJ, 2017. The effects of medication and current mood upon facial emotion recognition: findings from a large bipolar disorder cohort study. J Psychopharmacol 31(3), 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S, 1990. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 157, 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Li H, Cheung EF, Gong QY, 2010. Impaired facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 178(2), 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz BA, Parker DA, Trotti RL, McDowell JE, Keedy SK, Keshavan MS, Pearlson GD, Gershon ES, Ivleva EI, Huang LY, Hill SK, Sweeney JA, Thomas O, Hudgens-Haney M, Gibbons RD, Tamminga CA, 2021. Psychosis Biotypes: Replication and Validation from the B-SNIP Consortium. Schizophr Bull. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz BA, Sweeney JA, Hamm JP, Ivleva EI, Ethridge LE, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Tamminga CA, 2016. Identification of Distinct Psychosis Biotypes Using Brain-Based Biomarkers. Am J Psychiatry 173(4), 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, 1992. A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1), 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JF, Zlochower AJ, Lien J, Kanade T, 1999. Automated face analysis by feature point tracking has high concurrent validity with manual FACS coding. Psychophysiology 36(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparelli A, Corigliano V, De Carolis A, Mancinelli I, Trovini G, Ottavi G, Dehning J, Tatarelli R, Brugnoli R, Girardi P, 2013. Emotion recognition impairment is present early and is stable throughout the course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 143(1), 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornacchio D, Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Harvey PD, 2017. Self-assessment of social cognitive ability in individuals with schizophrenia: Appraising task difficulty and allocation of effort. Schizophr Res 179, 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL, 2006. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 32 Suppl 1, S44–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke H, Cropper SJ, Carter O, 2019. A Novel Dynamic Morphed Stimuli Set to Assess Sensitivity to Identity and Emotion Attributes in Faces. Frontiers in psychology 10, 757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daros AR, Ruocco AC, Reilly JL, Harris MS, Sweeney JA, 2014. Facial emotion recognition in first-episode schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychosis. Schizophr Res 153(1–3), 32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Mermon DE, Montrose DM, Miewald J, Gur RE, Gur RC, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS, 2010. Social cognition deficits among individuals at familial high risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 36(6), 1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eum S, Hill SK, Alliey-Rodriguez N, Stevenson JM, Rubin LH, Lee AM, Mills LJ, Reilly JL, Lencer R, Keedy SK, Ivleva E, Keefe RSE, Pearlson GD, Clementz BA, Tamminga CA, Keshavan MS, Gershon ES, Sweeney JA, Bishop JR, 2021. Genome-wide association study accounting for anticholinergic burden to examine cognitive dysfunction in psychotic disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 46(10), 1802–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eum S, Hill SK, Rubin LH, Carnahan RM, Reilly JL, Ivleva EI, Keedy SK, Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Clementz BA, Gershon ES, Keshavan MS, Keefe RSE, Sweeney JA, Bishop JR, 2017. Cognitive burden of anticholinergic medications in psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res 190, 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fiszdon JM, Richardson R, Greig T, Bell MD, 2007. A comparison of basic and social cognition between schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res 91(1–3), 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goghari VM, Sponheim SR, 2013. More pronounced deficits in facial emotion recognition for schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. Comprehensive psychiatry 54(4), 388–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotra MY, Hill SK, Gershon ES, Tamminga CA, Ivleva EI, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Clementz BA, McDowell JE, Buckley PF, Sweeney JA, Keedy SK, 2020. Distinguishing patterns of impairment on inhibitory control and general cognitive ability among bipolar with and without psychosis, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res 223, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel S, Almeida JR, Kerr N, Nau S, Ladouceur CD, Fissell K, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML, 2008. Elevated striatal and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity in response to emotional stimuli in euthymic bipolar disorder: no associations with psychotropic medication load. Bipolar Disord 10(8), 916–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Reilly JL, Keefe RS, Gold JM, Bishop JR, Gershon ES, Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA, 2013. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) study. Am J Psychiatry 170(11), 1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberger WC, Hill SK, Nelson CL, Reilly JL, Keefe RS, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Tamminga CA, Clementz BA, Sweeney JA, 2016. Unitary construct of generalized cognitive ability underlying BACS performance across psychotic disorders and in their first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res 170(1), 156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Sanislow C, Wang P, 2010. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 167(7), 748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston PJ, Enticott PG, Mayes AK, Hoy KE, Herring SE, Fitzgerald PB, 2010. Symptom correlates of static and dynamic facial affect processing in schizophrenia: evidence of a double dissociation? Schizophr Bull 36(4), 680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MT, Deckler E, Laurrari C, Jarskog LF, Penn DL, Pinkham AE, Harvey PD, 2020. Confidence, performance, and accuracy of self-assessment of social cognition: A comparison of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr Res Cogn 19, 002–002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA, 1987. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13, 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L, 2004. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res 68(2–3), 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Harvey PD, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Walker TM, Kennel C, Hawkins K, 2008. Norms and standardization of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). Schizophr Res 102(1–3), 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Morris DW, Sweeney JA, Pearlson G, Thaker G, Seidman LJ, Eack SM, Tamminga C, 2011. A dimensional approach to the psychosis spectrum between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: the Schizo-Bipolar Scale. Schizophr Res 133(1–3), 250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman P, 1994. Attentional bias, persecutory delusions and the self-concept. Br J Med Psychol 67 (Pt 1), 53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ, 2010. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull 36(5), 1009–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krabbendam L, Arts B, van Os J, Aleman A, 2005. Cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Schizophr Res 80(2–3), 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska-Pietura K, Mortimer A, 2013. Can antipsychotics improve social cognition in patients with schizophrenia? CNS Drugs 27(5), 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino DJ, Strejilevich SA, Fassi G, Marengo E, Igoa A, 2011. Theory of mind and facial emotion recognition in euthymic bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Psychiatry Res 189(3), 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathersul D, Palmer DM, Gur RC, Gur RE, Cooper N, Gordon E, Williams LM, 2009. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: II. Core domains and relationships with general cognition. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 31(3), 278–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M, 1979. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134, 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SE, Cuthbert BN, 2012. Research Domain Criteria: cognitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behavior. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 14(1), 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mothi SS, Sudarshan M, Tandon N, Tamminga C, Pearlson G, Sweeney J, Clementz B, Keshavan MS, 2018. Machine learning improved classification of psychoses using clinical and biological stratification: Update from the bipolar-schizophrenia network for intermediate phenotypes (B-SNIP). Schizophr Res. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Harvey PD, Penn DL, 2018. Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation: Results of the Final Validation Study. Schizophr Bull 44(4), 737–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Cohn JF, E B, 2007. The Dynamic Affect Recognition Evaluation. University of Ilinois at Chicago, Brain-Body Center, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Cohn JF, Bal E, Lamb D, Lewis GF, 2016. The Dynamic Affect Recognition Evaluation software, 2.3 ed. Brain-Body Center for Psychophysiology and Bioengineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B, 2000. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11(5), 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca CC, Heuvel E, Caetano SC, Lafer B, 2009. Facial emotion recognition in bipolar disorder: a critical review. Braz J Psychiatry 31(2), 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco AC, Reilly JL, Rubin LH, Daros AR, Gershon ES, Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Hill SK, Keshavan MS, Gur RC, Sweeney JA, 2014. Emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and psychotic bipolar disorder: Findings from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) study. Schizophr Res 158(1–3), 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samame C, Martino DJ, Strejilevich SA, 2012. Social cognition in euthymic bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analytic approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand 125(4), 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers M, Papadopoulou K, Bruno S, Cipolotti L, Ron MA, 2006. Bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: cognition and emotion processing. Psychol Med 36(12), 1799–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Ivleva EI, Keshavan MS, Pearlson GD, Clementz BA, Witte B, Morris DW, Bishop J, Thaker GK, Sweeney JA, 2013. Clinical Phenotypes of Psychosis in the Bipolar and Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, John CH, 2004. Attentional and memory bias in persecutory delusions and depression. Psychopathology 37(5), 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler NS, Allen DN, Sutton GP, Vertinski M, Ringdahl EN, 2013a. Differential impairment of social cognition factors in bipolar disorder with and without psychotic features and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 47(12), 2004–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler NS, Strauss GP, Sutton GP, Vertinski M, Ringdahl EN, Snyder JS, Allen DN, 2013b. Emotion perception abnormalities across sensory modalities in bipolar disorder with psychotic features and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 147(2–3), 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA, 1978. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.