Transgender and gender-expansive (TGGE) youth have a gender identity that differs from their sex assigned at birth and often meet criteria for gender dysphoria (GD), the psychological distress due to the mismatch of one’s gender identity from their assigned sex at birth (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). TGGE youth with GD have high rates of co-occurring mental health diagnoses, including social anxiety disorder (de Vries et al., 2011). Social anxiety disorder is the fear of social situations and social evaluation that causes clinically significant impairment (American Psychiatric Association).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) focuses on the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and has been proven to be an effective treatment for social anxiety disorder in children, adolescents, and adults (Albano et al., 1995; Gallagher et al., 2004; Hayward et al., 2000; Khalid-Khan et al., 2007). Despite the documented effectiveness of CBT, there has been sparse research investigating the impact of CBT on TGGE individuals specifically. For TGGE individuals, it has been proposed that tailoring CBT treatment to specific minority groups makes these treatments more effective and acceptable for marginalized groups (Austin & Craig, 2015). These recommendations are aimed to address minority stress theory, which was originally developed using a systems theory approach to explain how structural, economic, and interpersonal factors contributed to mental health disparities among women with minoritized sexual orientations (Brooks, 1981). Minority stress theory posits that being a member of a marginalized or oppressed group exposes individuals to unique, identity-related stressors which may in turn contribute to increased rates of psychopathology among members of that group. It has been applied to conceptualize identity-based stress across diverse samples, including racial minority individuals and TGGE populations (Bockting et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2016; Mustanski et al., 2010; Puckett et al., 2016; Williams, 2018). Meyer (2003) conceptualized these stressors as unique, chronic, and socially mediated across domains through experiences of systematic discrimination and includes chronic exposure to and threat of verbal and physical violence, high rates of homelessness and underemployment, and poor medical care for TGGE people (James et al., 2016). In TGGE youth specifically, the majority report social exclusion, parental rejection, and high levels of discrimination, bullying, and violence (Bauer et al., 2015). As a result, mental health disorder rates for TGGE individuals are high and TGGE individuals experience more anxiety when compared to the general population (Bouman et al., 2016; Carmel & Erickson-Schroth, 2016; Dhejne et al., 2016; Millet et al., 2016). More specifically for TGGE youth, reports of the prevalence of social anxiety disorder range from 9.5% to 31.4%, which is higher than the general population estimate of 7% (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Bergero-Miguel et al., 2016; de Vries et al., 2011).

Distress related to GD may contribute to and exacerbate symptoms of social anxiety disorder. Incongruence between one’s experienced and expressed gender and one’s outward appearance may contribute to general discomfort in social environments where there is a risk of being misgendered or treated as a member of a gender that is incongruent with identity (Galupo et al., 2019). Lived experiences and worries about being misgendered or misperceived may prompt additional social concerns that generalize to a broader range of anxious symptoms, including fear of being evaluated and corresponding avoidance of social situations. Recent research has identified “interruption of social functioning” as a common feature of GD among transgender individuals (Galupo et al., 2020). Social situations can trigger symptoms of dysphoria, including distress related to speaking voice, appearance, and being appraised by strangers. For some, discomfort speaking in social situations or interacting with unfamiliar people due to concerns about gender-related appraisal may appear similar to symptoms of social anxiety. For individuals with both social anxiety disorder and GD, avoidance behavior may serve to reduce anxiety as well as dysphoria and treatment approaches that do not consider both functions may be less effective in addressing maintaining factors for social anxiety.

The experiences of TGGE youth complicate the presentation of social anxiety disorder. The definition of social anxiety disorder assumes that an individual’s worries related to social situations are out of proportion to the true threat (American Psychological Association, 2013). For TGGE youth, anticipatory and in-vivo anxiety are many times not out of proportion to actual threats posed by social encounters or the sociocultural context. Distress related to social interactions and fear of social judgment and discomfort are normative responses to the minority stressors (e.g., discrimination, stigma, marginalization) experienced by TGGE youth. Hendricks and Testa (2012) outline the importance of integrating minority stress for clinical approaches with TGGE clients. Specifically, they recommend that assessment and treatment explicitly discuss minority stress and focus on promoting resilience (Hendricks & Testa, 2012). Further, high levels of internalized transphobia and incongruence of identity appearance are both related to major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder among youth (Chodzen et al., 2019). This suggests that both external and internal minority stressors could impact presentations of social anxiety. As such, it is important to consider the effects minority stress may have on social anxiety when choosing treatment. In particular, recent literature has provided a framework for understanding social anxiety through a minority stress framework in TGGE youth by specifically addressing coping with distal stressors (e.g., being misgendered, being dead-named) and proximal stressors (e.g., negative self-evaluation, internalized transphobia; Coyne et al., 2020; Deloizer et al., 2020).

Evidence suggests that GD may function as a Proximal, internal source of minority stress (Galupo et al., 2020; Lindley & Galupo, 2020). Experiences of GD can increase in response to stressful social situations and avoiding social situations may help decrease gender dysphoria symptoms in a way that contributes to and perpetuates social anxiety. Additionally, high levels of GD are correlated with greater anticipated stigma (Lindley & Galupo). Individuals with greater dysphoria may use social avoidance due to anticipation of discrimination, further demonstrating the importance of adapting existing social anxiety treatment protocols to specifically consider and address the ways in which GD contribute to and interact with social anxiety among TGGE individuals.

When assessing the presentations of GD and social anxiety disorder, there are many situations that might trigger symptoms of both diagnoses. For youth who experience social anxiety and GD, the distress and impairment associated with social fears may be exacerbated by specific worries related to how others interpret their gender based on observable characteristics such as their body shape/size or tone of voice. These youth may fear negative evaluation as well as worry that others will perceive their identity inaccurately or with judgment, leading to experiences of misgendering, bullying, or violence (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006). The authors argue that the interaction of social anxiety and GD calls for a thoughtful approach to treatment that both utilizes evidence-based practices and addresses the experience of minority stress. Current research on evidence-based treatments for social anxiety disorder does not speak to the impact of experiences of minority stress on treatment outcomes. In order to reduce the distress and impairment associated with social anxiety disorder and GD among TGGE individuals, mental health professionals must adapt evidence-based practices to meet the treatment needs of this population.

For cisgender youth with social anxiety disorder, CBT is the gold standard of treatment. Treatment is structured and addresses psychoeducation regarding cognitive restructuring of unrealistic thoughts, problem solving, and exposure-based methods to help children, teens, and adults approach anxiety-provoking situations. The use of a group setting allows teens to have in-vivo practice of social interactions that individual CBT does not provide. Group CBT is an effective treatment for social anxiety disorder in children, adolescents, and adults (Albano et al., 1995; Hayward et al., 2000; Khalid-Khan et al., 2007).

While the need for mental health services for TGGE youth is well-documented, providers do not have a strong basis for systematically adapting services for TGGE youth (Spivey & Edwards-Leeper, 2019). Adaptations may be particularly important for this population given that limited access to gender-affirming and culturally competent care are unique and substantial barriers to care for TGGE youth (Pampati et al., 2021; The Trevor Project, 2021). The guidelines that exist for the treatment of TGGE populations endorse gender affirmative therapy, calling for mental health providers to educate themselves on TGGE health, advocacy, and terminology when providing mental health care to this population (American Psychological Association, 2015; World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011). As a result, researchers are advocating for a gender affirmative model of behavioral health care (Chen et al., 2018; Spivey & Edwards-Leeper, 2019).

Despite the aforementioned recommendations, there are currently no published instances of CBT for TGGE youth with social anxiety disorder (Chen et al., 2018). This paper focuses on the rationale and adaptations of group CBT to meet the unique needs of TGGE youth with social anxiety disorder and co-occurring GD using a descriptive group case study in a clinic setting. Establishing the acceptability of an adapted treatment protocol is an essential first step to ensuring that treatment is gender-affirming. This paper does not reflect a formal research protocol or a full treatment adaptation study; however, this descriptive case study provides an example of how a standard group CBT protocol can be adapted to meet the needs of TGGE youth and provides preliminary evidence for acceptability and client satisfaction.

Group CBT Protocol Adaptation

The aim of this section is to provide an overview of the writers’ approach to adapting an existing EBT approach for implementation with a group of TGGE youth and to provide specific examples of gender-affirming changes to the established protocol to maximize acceptability. The modifications made to the existing treatment protocol for social anxiety were not intended to target symptoms of GD. However, the procedures aimed to consider how symptoms of GD may contribute to social anxiety symptoms and may affect the efficacy and experience of individual components (e.g., exposures, cognitive restructuring) of group therapy for social anxiety.

Intervention

Adaptation Process

The writers adapted and ran the group in a clinical setting, which mirrors the process of many providers who are on the front line of clinical work. While this was not a formal community-based participatory research framework, transgender youth and volunteers within the clinic had input in this adaptation. This intervention was adapted from a researched and standardized group CBT program for social anxiety disorder developed first for adults (Hope et al., 2006) and then adapted for teens where it demonstrated efficacy (Albano et al., 1995; Hayward et al., 2000). In the authors’ clinical setting (a large child psychiatry faculty group practice), there was an existing group using this protocol for both cisgender and TGGE socially anxious youth that was not meeting the needs of TGGE youth. This was revealed through collaboration with two transgender high school students who participated in a CBT group for social anxiety and expressed frustration with the treatment not being adapted for TGGE youth and their unique needs. Of note, both teens did not complete the standard group and left the group prematurely (i.e., before half of the group was completed). They reported that while they felt affirmed by treatment providers, they felt invalidated when asked to restructure their thoughts around microaggressions within the community. Further, they felt that it was difficult to discuss their anxiety with cisgender youth who might not understand their experience. As a result, the authors discussed the importance of meeting the needs of TGGE teens who are socially anxious in the clinic and began a new group specifically for TGGE teens.

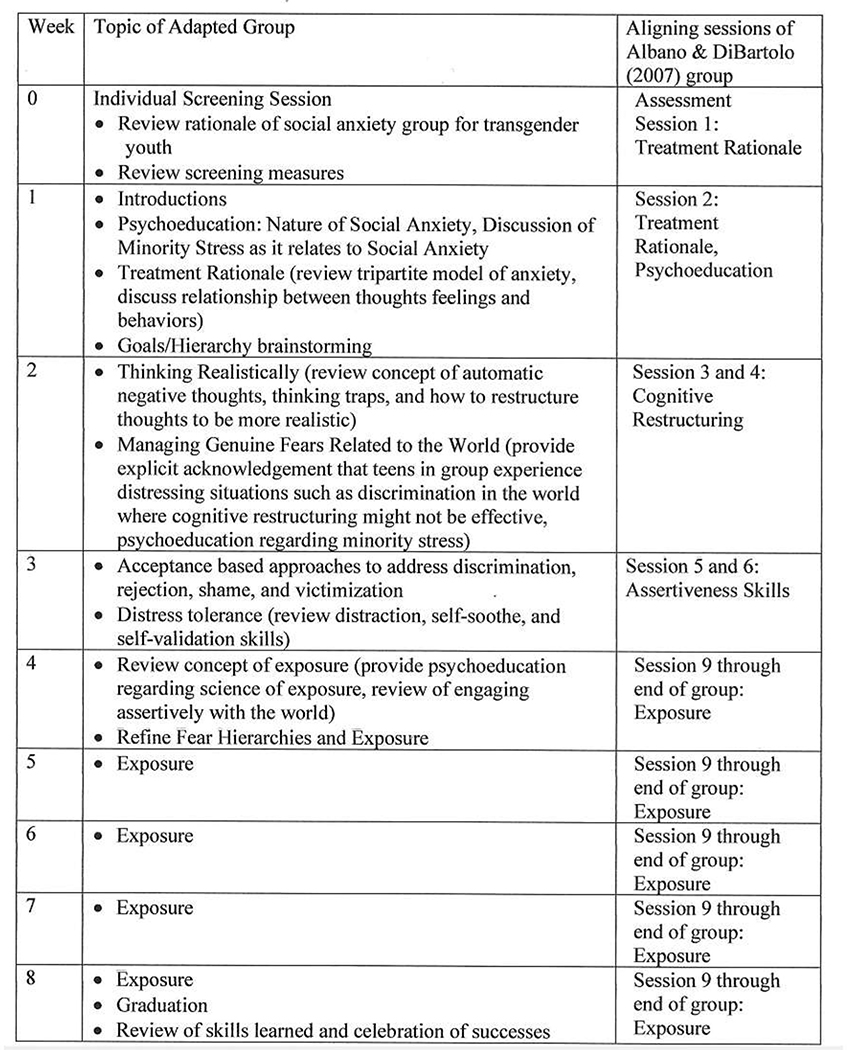

Authors worked with two transgender college summer interns sponsored by the authors who edited the manual to improve protocol acceptability for a group of TGGE teens. The group protocol was condensed into eight sessions to decrease attrition, which was an issue in other CBT groups in the clinic. Figure 1 shows a week-by-week group outline in comparison to the Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Phobia in Adolescents protocol (Albano & DiBartolo, 2007). Information about treatment rationale was provided by group leaders prior to the initiation of the protocol. Therefore, sessions from the original protocol that focused on treatment rationale were removed from the present adaptation. Sessions that focused on assertiveness skills and coping strategies were condensed and modified to target TGGE youth specifically and practiced during in-vivo exposures. Sessions 7 and 8 were also removed as they focused on review of skills and psychoeducation regarding the second half of treatment. Further, to maximize feasibility given the ratio of staff to group members, number of exposure sessions were reduced as each exposure session prescribed at least three exposures for each individual.

Figure 1.

Session by Session Outline of Group. This figure describes the general sessions and structure for each week of the group as well as session overlap with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Social Phobia in Adolescents Group (Albano & DiBartolo, 2007). Homework was reviewed from the week prior and assigned for the following week, each week of the group. Please reach out to first author to learn more about the group protocol.

Adaptation in Group Description

Group leaders explicitly marketed this group as gender-affirming and that group leaders were committed to providing gender-affirming treatment. During the initial assessment, group leaders used gender-affirming language, validated clients’ experiences and identity, and assessed the impact of transgender-specific issues on well-being, as recommended in the literature (Austin & Craig, 2015). Group leaders asked for affirmed name and pronouns at the start of group and during assessment.

Addition of Minority Stress as a Concept

In line with recommendations from prior research groups, the authors also changed the content of the groups to be more gender-affirming (Austin & Craig 2015). Group leaders incorporated minority stress into the group curriculum by explicitly acknowledging and teaching about minority stress theory to help group members better understand their experiences in the world. Clinicians allowed for group discussion about each youth’s experience with minority stress by providing a validating framework around how distal and proximal stressors may impact TGGE youth and how these stressors may contribute to social anxiety (Coyne et al., 2020; Deloizer et al., 2020). Because many participants had similar experiences related to minority distress (e.g., misgendering in school or school ID card not having affirmed name), validation was inherently provided and teens encouraged resilience within one another. Group leaders also facilitated problem solving.

Combination of Cognitive Restructuring and Distress Tolerance

Addressing cognitive distortions within the group was individualized based on the type of thought. In order to address some cognitive distortions, cognitive restructuring was used as an intervention as it would with cisgender youth. Cognitive techniques for these socially anxious thoughts focus on combating thought distortions that lead to the unreasonable fear that people will react to or evaluate an individual negatively.

Acceptance and distress tolerance skills were added to the group to complement cognitive restructuring. This change was made because restructuring cognitions that are feared and potentially realistic outcomes can be perceived as invalidating. TGGE individuals have genuine fears (i.e., a high probability of threat for rejection or violence towards them), and cognitive restructuring may be ineffective or invalidating. To counter this, treatment adaptations allowed time for teaching and practicing distress tolerance skills. These skills helped youth tolerate negative emotions related to realistic fears in the world and included acceptance techniques for group members to be more accepting of themselves. Group leaders taught group members to differentiate between automatic negative thoughts that are realistic outcomes versus unrealistic thoughts and to use distress tolerance and cognitive restructuring, respectively. Group leaders were explicit that it is not necessary for group members to restructure thoughts related to minority stress.

One example of using both cognitive restructuring and distress tolerance follows. One common fear for cisgender and TGGE teens is giving presentations and “being judged for being a loser while giving a presentation in school.” A TGGE teen might think “everyone will think I am a loser,” and at the same time think “they will know that I am transgender” or “they will judge the sound of my voice because I am trans.” By using both cognitive restructuring and distress tolerance, group leaders could coach the group members in generating realistic thoughts related to others not thinking they are “a loser” and use distress tolerance to tolerate worries that others might judge them for being transgender.

In other situations, group leaders could help TGGE group members generate more realistic coping thoughts in situations where someone might misgender them. Coping thoughts might include, “I might be misgendered, and I know how to correct that person” or “I might be misgendered, and I know I can handle it.” At the same time, group leaders could also encourage youth to use distress tolerance skills to reduce pain associated with the experience. An example of a hypothetical situation provided in group to practice both coping thoughts and distress tolerance is shopping in a clothing section associated with a patient’s affirmed gender. Anxious thoughts could include, “I can’t shop in the boy’s section of the store, people will judge me,” and group leaders would help this teen restructure and cope with these thoughts to be more accurate with statements like, “I can shop in the boy’s section, and if someone judges me, I can handle it by using a distress tolerance skill.”

Adaptations Made to Hierarchy Development and Exposures

Hierarchy development focused on information collected during the assessment, including the initial screening session. Each hierarchy was highly individualized based on the individual’s needs and was completed within session and included at least 10 items to address. Group members would list items that are anxiety-provoking and provide both subjective units of distress (SUDS) and avoidance ratings. Group leaders focused on both gender-specific exposure ideas (e.g., using affirmed name and pronouns, using affirmed bathrooms, shopping for and wearing affirmed clothing) as well as non–gender specific social exposures (e.g., presentations, maintaining conversations, ordering at a coffee shop). If a teen needed practice in assertiveness skills, this was also included within exposure preparation. Many exposures that were non-gender-specific also addressed cognitions related to an individual’s tone of voice not aligning with their gender identity or worries that others would judge the individual’s gender presentation. Group leaders and youth collaboratively chose which exposure to complete.

Group leaders led exposures within the clinic and out in the community. Within the clinic, exposures were led in “safe settings” where youth would introduce themselves or talk about their TGGE identity. Youth also practiced correcting one another if pronouns were used incorrectly, and doing so in an assertive way. As youth became less anxious in clinic, group leaders began to engage in real-world practice. Some unique examples included going to a shoe store in the community and asking for shoes of the individual’s affirmed gender, going to a coffee shop and using affirmed name and pronouns to order, and youth role-playing conversations with confederate therapists who acted as teachers or other authority figures. Youth encountered both affirming and nonaffirming individuals in the community, and group leaders processed each exposure with group members to discuss potential use of cognitive restructuring or distress tolerance skills as needed.

Single Group Acceptability Pilot

General Procedure

Authors ran this group at an academic medical center’s clinic. A retrospective chart review was approved by the Institutional Review Board to review group data collected as routine parts of clinical practice. Each group met for 75 minutes once every week for eight sessions. Group length was determined by space availability within the clinic. Services were provided at a fee for service and providers offered a sliding scale for families who could not afford the full fee of the group. Group members completed postmeasures at the end of the group. All group members attended at least six of eight groups (M = 7.00, SD = 0.82).

Therapists

Sessions were conducted by a cisgender licensed psychologist and a cisgender licensed social worker who have expertise in working with TGGE youth, along with two cisgender clinical psychology externs who served as exposure coaches. We invited transgender volunteers to be in the group, though they had a scheduling conflict and did not participate.

Participants

Requirements for group participation were a diagnosis of GD and social anxiety disorder. Rule-outs for participation were autism spectrum disorder and psychosis as these are consistent with rule-outs for the clinic’s social anxiety group for cisgender youth. Eight individuals, ranging from grade 9 to 11, aged 14 through 16, were enrolled in group for treatment of social anxiety disorder during spring 2018 (see Table 1 for demographics). Data only existed for seven of eight individuals who participated in the group, as one participant did not attend the last session or complete measures. All participants identified as transgender and were recruited via listserv, mass email, and word of mouth. Recruitment was aimed towards youth ages 13 through 18 in grades 8 through 12 who experience GD and social anxiety disorder within our in-house clinic and with gender-affirming community health providers. All members of the group met criteria for GD and social anxiety disorder confirmed by clinical interview in the screening session. Participants were also asked about current stressors in their lives related to their gender including family support, school, peers, and places where they are comfortable and not comfortable expressing their gender identity. All participants had other co-occurring disorders and were in individual therapy.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Age, M (SD) | 15 (0.82) | |

| Range: 13–17 | ||

| Assigned Sex at Birth | ||

| Male | 1 (14%) | |

| Female | 6 (86%) | |

| Gender, n | ||

| Transgender Male | 6 (86%) | |

| Transgender Female | 1 (14%) | |

| Race, n | ||

| White | 5 (71%) | |

| Biracial | 2 (29%) | |

| Ethnicity, n | ||

|

|

||

| Latinx 2 (29%) | ||

| Not Latinx 5 (71%) | ||

|

|

||

| Transition Status, n | ||

| Gender Affirming Hormones | 2 (29%) | |

| Social Transition in School | 5 (71%) | |

| Social Transition at Home | 7 (100%) | |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses, n | ||

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 7 (100%) | |

| Gender Dysphoria | 7 (100%) | |

| Co-occurring Diagnosis1, n | 7 (100%) | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 5 (71%) | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 5 (71%) | |

| ADHD | 4 (57%) | |

| PTSD | 1 (14%) | |

| Panic Disorder | 1 (14%) | |

Diagnosis in addition to Social Anxiety Disorder and Gender Dysphoria

Measures

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) was used to measure self-report satisfaction with the group (Larsen et al., 1979). The CSQ-8 is a brief, 8-item validated measure that is on a 4-point Likert-type scale to self-report satisfaction with healthcare services. Participants were asked to rate each item from 1 to 4, with 4 indicating the highest level of satisfaction. Participants rate satisfaction statements including, “How satisfied are you with the amount of help you have received?” Summing the responses yields a single score indicating service satisfaction, with a higher score correlating to higher satisfaction. The CSQ-8 also allows for a comment section on the printed version given to participants. Participants were also verbally asked to write feedback they had about the group on the form.

Acceptability

Preliminary results from the pilot group suggest that the adapted protocol was acceptable and perceived as gender-affirming. Although the sample was limited, there was no attrition across group members, and all members attended at least 75% (6 of 8 sessions) of the groups. Only one participant did not complete the final session, which conflicted with school exams. In assessing acceptability of the group, we looked both at the CSQ-8 scores and at open-ended feedback. CSQ-8 scores were high, with a mean score of 29.5 (SD = 2.40; out of a maximum of 32). No participant rated below a 3 (mostly satisfied) out of 4 (very satisfied) on any item. This indicates that participants were generally satisfied with the care they received. When asked for open-ended feedback and suggestions for improving the acceptability of the group protocol, none of the group members suggested modifications. The few written responses received expressed gratitude and satisfaction with the group. Anecdotally, members also appeared to benefit from social support in the group. Most group members were early for the group and sat together within the waiting room. Many group members commented independently to group leaders that they have built friendships with one another after the group, despite going to different schools. Finally, multiple youth asked to join the group again.

This descriptive case study aims to illustrate an example of an intervention that has been adapted to meet the unique needs of TGGE youth with social anxiety disorder and co-occurring GD using a minority stress framework. This paper aims to highlight the importance of adapting evidence-based treatments for TGGE youth and to present preliminary acceptability of this adapted intervention. Establishing acceptability is an essential first step in adapting gender-affirming treatments, and future research will examine the efficacy of the adapted intervention. Preliminary data yielded promising markers indicative of acceptability, including high rates of group participation and participant satisfaction following the conclusion of the protocol.

Conclusions

It is well documented that there is a need for psychotherapy adaptations for TGGE youth with mental health concerns (Chen et al., 2018; Spivey & Edwards-Leeper, 2019), though there are few published models of this work. We believe that it is important for clinical providers to evaluate ways in which they can adapt treatments to become more affirming by following recommendations of other groups, as this paper has done (Austin & Craig, 2015; Austin et al., 2018). Given preliminary acceptability of the adapted intervention protocol, the treatment should be further refined through a larger open trial to examine both acceptability across a larger, more diverse sample and to examine efficacy of the intervention. Specifically, addressing the unique minority stress factors related to nonbinary youth would also be essential in further adaptation of this group. Nonbinary youth experience unique challenges that are based in society’s deeply rooted sense of the gender binary in restroom labels, sports, and pronouns (Thorne et al., 2019).

Effectively adapting evidence-based practices to meet the needs of marginalized populations requires input from community member participants. This group was adapted after discussions with TGGE youth who were displeased with services that they had been provided in the past. This brings to light the importance of having TGGE voices as part of treatment development and adaptations. Ideally, this work would be done through use of community-based participatory research which involves engaging community members and stakeholders at all stages of the research, including hypothesis generation, adaptation of programming, implementation, and dissemination of information. Future refinement and implementation of the adapted protocol will continue to include input from TGGE individuals. For clinicians working with TGGE youth, it is important to consider ways in which evidence-based practices can be modified to be more gender-affirming. Training clinicians to provide affirming treatment that incorporates a minority stress framework to conceptualize and address the difficulties facing TGGE youth is an important step in closing the treatment gap for this vulnerable population. Concerns about finding an LGBTQ+ competent provider represent a major barrier to treatment for TGGE youth (The Trevor Project, 2020). Clinics that provide gender-affirming care should make efforts to communicate and advertise that they provide affirming care and, if possible, should offer programming specifically to address the unique needs of TGGE youth. Importantly, we advocate for gender-affirming groups that address minority stress and discrimination that TGGE youth experience daily and that allow youth to provide social support to one another.

Footnotes

All authors declare no known conflicts of interest or funding to report.

Contributor Information

Samantha Busa, NYU Langone Health.

Jeremy Wernick, NYU Langone Health.

John Kellerman, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Elizabeth Glaeser, NYU Langone Health.

Kyle McGregor, Main Line Health & Jefferson University.

Julius Wu, New York University.

Aron Janssen, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine.

References

- Albano AM, & DiBartolo PM (2007). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Phobia in Adolescents: Stand Up, Speak Out. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Albano AM, Marten PA, Holt CS, Heimberg RG, & Barlow DH (1995). Cognitive-Behavioral Group Treatment for Social Phobia in Adolescents A Preliminary Study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183(10), 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, & Craig SL (2015). Transgender affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy: Clinical considerations and applications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(1), 21. 10.1037/a0038642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Craig SL, & D’Souza SA (2018). An AFFIRMative cognitive behavioral intervention for transgender youth: Preliminary effectiveness. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(1), 1. 10.1037/pro0000154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, & Hammond R (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: a respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 15, 525. https://doi.org/0.1186/s12889-015-1867-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergero-Miguel T, Garcia-Encinas MA, Villena-Jimena A, Perez-Costillas L, Sanchez-Alvarez N, de Diego-Otero Y, & Guzman-Parra J (2016). Gender Dysphoria and Social Anxiety: An Exploratory Study in Spain. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(8), 1270–1278. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, Crawford JR, Millet N, Fernandez-Aranda F, & Arcelus J (2016). Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 16–26. 10.0.4.56/15532739.2016.1258352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel TC, & Erickson-Schroth L (2016). Mental health and the transgender population. Psychiatric Annals, 46(6), 346–349. 10.3928/00485713-20160419-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Edwards-Leeper L, Stancin T, & Tishelman A (2018). Advancing the practice of pediatric psychology with transgender youth: State of the science, ongoing controversies, and future directions. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 6(1), 73. 10.1037/cpp0000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodzen G, Hidalgo MA, Chen D, & Garofalo R (2019). Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 467–471. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JM, Feinstein BA, Rodriguez-Seijas C, Taylor CB, & Newman MG (2016). Rejection sensitivity as a transdiagnostic risk factor for internalizing psychopathology among gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 259. 10.1037/sgd0000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne CA, Poquiz JL, Janssen A, & Chen D (2020). Evidence-based psychological practice for transgender and nonbinary youth: Defining the need, framework for treatment adaptation, and future directions. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3), 340–353. 10.1080/23794925.2020.1765433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delozier AM, Kamody RC, Rodgers S, & Chen D (2020). Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents: A topical review from a minority stress framework. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 842–847. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, & Cohen-Kettenis PT (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 52(11), 1195–1202. 10.0.4.87/j.1469-7610.2011.02426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, & Arcelus J (2016). Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 44–57. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1115753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HM, Rabian BA, & McCloskey MS (2004). A brief group cognitive-behavioral intervention for social phobia in childhood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(4), 459–479. 10.1016/S0887-6185(03)00027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galupo MP, Pulice-Farrow L, & Lindley L (2020). “Every time I get gendered male, I feel a pain in my chest”: Understanding the social context for gender dysphoria. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 199–208. 10.1037/sah0000189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, & D’augelli AR (2006). Transgender youth: Invisible and vulnerable. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(1), 111–128. 10.1300/J082v51n01_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Varady S, Albano AM, Thienemann M, Schatzberg Henderson LAF (2000). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia in female adolescents: results of a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(6), 721–726. 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460. 10.1037/a0029597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, & Turk CL (2006). Therapist guide for managing social anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. New York: Oxford University Press. Reviewed by: Perkins, A. (2008). Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M (2016). The report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey: National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

- Khalid-Khan S, Santibanez M-P, McMicken C, & Rynn MA (2007). Social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatric Drugs, 9(4), 227–237. 10.2165/00148581-200709040-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, & Nguyen TD (1979). Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(3), 197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley L, & Galupo MP (2020). Gender dysphoria and minority stress: Support for inclusion of gender dysphoria as a proximal stressor. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(3), 265–275. 10.1037/sgd0000439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet N, Longworth J, & Arcelus J (2016). Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in the transgender population: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 27–38. 10.1080/15532739.2016.1258353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS,Garofalo R, & Emerson EM (2010). Mental Health Disorders, Psychological Distress, and Suicidality in a Diverse Sample of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youths. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12). 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampati S, Andrzejewski J, Steiner RJ, Rasberry CN, Adkins SH, Lesesne CA, Boyce L, Grose RG, & Johns MM (2021). "We Deserve Care and we Deserve Competent Care": Qualitative Perspectives on Health Care from Transgender Youth in the Southeast United States. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 56, 54–59. 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Maroney MR, Levitt HM, & Horne SG (2016). Relations between gender expression, minority stress, and mental health in cisgender sexual minority women and men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 489. 10.1037/sgd0000201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spivey LA, & Edwards-Leeper L (2019). Future directions in affirmative psychological interventions with transgender children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–14. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Trevor Project. (2020). 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. Author.

- The Trevor Project. (2021). 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. Author.

- Thorne N, Witcomb GL, Nieder T, Nixon E, Yip A, & Arcelus J (2019). A comparison of mental health symptomatology and levels of social support in young treatment seeking transgender individuals who identify as binary and non-binary. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 241–250. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1452660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR (2018). Stress and the Mental Health of Populations of Color: Advancing Our Understanding of Race-related Stressors. Journal of health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 466–485. 10.1177/0022146518814251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health. (2011). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people, seventh version (Vol.2017). Author. [Google Scholar]