Abstract

Mortierella alpina was transformed successfully to hygromycin B resistance by using a homologous histone H4 promoter to drive gene expression and a homologous ribosomal DNA region to promote chromosomal integration. This is the first description of transformation in this commercially important oleaginous organism. Two pairs of histone H3 and H4 genes were isolated from this fungus. Each pair consisted of one histone H3 gene and one histone H4 gene, transcribed divergently from an intergenic promoter region. The pairs of encoded histone H3 or H4 proteins were identical in amino acid sequence. At the DNA level, each histone H3 or H4 open reading frame showed 97 to 99% identity to its counterpart but the noncoding regions had little sequence identity. Unlike the histone genes from other filamentous fungi, all four M. alpina genes lacked introns. During normal vegetative growth, transcripts from the two histone H4 genes were produced at approximately the same level, indicating that either histone H4 promoter could be used in transformation vectors. The generation of stable, hygromycin B-resistant transformants required the incorporation of a homologous ribosomal DNA region into the transformation vector to promote chromosomal integration.

The filamentous fungus Mortierella alpina produces up to 50% of its biomass as triacyglycerol, which is rich in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (7, 26). These fatty acids are important both nutritionally and pharmacologically, and there is much interest in developing microbial processes for their production (19, 26). To date, manipulation of M. alpina to produce oils with different fatty acid contents has been carried out by strain mutagenesis (7). The recent isolation of several fatty acid desaturase genes from this fungus has presented the opportunity of using recombinant methods to modify the fatty acid composition of its oil (14, 22, 27, 38). To achieve this goal, a DNA transformation system must be developed for M. alpina, because there are no reports of transformation in this organism.

Efficient transformation vectors usually contain a homologous promoter to drive expression of the selection marker. In the case of the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium (12) and in Tetrahymena thermophila (17), dominant antibiotic resistance markers have been expressed using a strong, homologous histone H4 promoter. Histone H3 and H4 promoters have also been used to express reporter genes in yeast and plants (3, 11). Additionally, a number of fungal histone genes have been characterized (10, 21, 28, 39). Most histone genes are highly expressed, and their regulation is tightly coupled to DNA synthesis during the cell cycle (3, 32). The use of a histone promoter to express selection markers should, however, present no problems in fungal cultures which normally grow asynchronously.

In the present paper, we describe the isolation and characterization of two pairs of histone H3 and H4 genes from M. alpina and the use of one of the histone H4 promoters in a transformation vector to drive expression of the hygromycin B resistance gene. We also report the need to include a homologous ribosomal DNA (rDNA) region in the vector to promote chromosomal integration for the generation of stable transformants. This is the first reported case of transformation in this commercially important fungus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions.

Most of the work described in this paper was carried out with M. alpina strains CBS 224.37 and CBS 528.72 (ATCC 32222), which were obtained from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Baarn, The Netherlands. Other strains used were CBS 210.32, CBS 250.53, and CBS 527.72, all from the CBS culture collection, and CCF 2639, from the Culture Collection of Fungi, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, which was kindly supplied by R. Herbert, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland. Two media used for culturing M. alpina were potato dextrose broth (PDB; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and S2GYE (5% [wt/vol] glucose, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract [Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom], 0.18% [wt/vol] NH4SO4, 0.02% [wt/vol] MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.0001% [wt/vol] FeCl3 · 6H2O, 0.1% [vol/vol] trace elements [Fisher Scientific UK, Loughborough, United Kingdom], 10 mM K2HPO4–NaH2PO4 [pH 7.0]), and growth conditions were as described previously (38). Streptomyces sp. strain no. 6 (16) was obtained from the National Collection of Industrial Bacteria, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, and grown in a chitin-chitosan-containing minimal medium to produce “streptozyme” as described previously (34).

Isolation and analysis of the histone H3–H4 genes.

Degenerate primers H3, 5′-YTSMGSGAYAAYATHCA-3′ (192-fold degeneracy), and H2, 5′-ARSGCRTASACSACRTC-3′ (64-fold degeneracy), were designed after aligning the histone H4 protein sequences of Aspergillus nidulans (P23750 and P23751) (10), Neurospora crassa (P04914) (39), P. chrysosporium (P35058), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (P02309) (28), and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (P09322) (21). They bind to regions of the histone H4 gene which encode LRDNIQ and DVVYAL, respectively, and amplify a 206-bp fragment, H3H2. Standard PCR conditions were used at an annealing temperature of 50°C. The H3H2 fragment was cloned into vector pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and sequenced. 32P-labeled H3H2 was used subsequently to probe Southern blots and to screen a BamHI genomic DNA library from M. alpina strain CBS 528.72, which had been constructed as described previously (38). Positive pBK-CMV (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) phagemid clones were excised in vivo, and their inserts were sequenced. Total RNA was isolated from fungal mycelia using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Poly(A)-containing RNA (0.5 to 5.0 μg) for Northern analysis was enriched from 500 μg of total RNA using Oligotex mRNA minicolumns (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). In this case, total RNA was isolated from freeze-ground mycelia using a method for extracting RNA from yeast cells (24). Total or poly(A)-enriched RNA samples were denatured at 55°C for 15 min in GFM buffer (0.55 M glyoxal, 39% [vol/vol] deionized formamide, 60 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS], 1.5 mM sodium acetate, 0.3 mM EDTA [pH 7.0]) prior to electrophoresis through 1% (wt/vol) agarose gels with 0.24- to 9.5-kb RNA molecular weight (MW) markers (Life Technologies). The histone H4 gene-specific probes P4.1 (91 bp) and P4.2 (194 bp) were amplified by PCR at annealing temperatures of 60 and 58°C, respectively, from genomic clones using primers H4.15 (5′-TCAGCCGCACTCGCAGCTGC-3′) and H4.10 (5′-AGTGTCAAAGAGGGTTCTAT-3′) for P4.1 and primers H4.25 (5′-GACTTGCCCATCGTCGTCCT-3′) and H4.20 (5′-GCATTGCTGCGAGGACAATT-3′) for P4.2. Signals on Northern blots were detected using a Fuji BAS 1500-phosphorimager.

For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), approximately 0.1 μg of poly(A)-containing RNA which had been purified twice through Oligotex mRNA minicolumns (QIAGEN GmbH) was used as a template in a cDNA first-strand synthesis reaction (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) with an anchored oligo(dT)18 primer, CN95 [5′-CTTCTGGATGTGCGTACTCGAGCT(T)18-3′], according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was then carried out with the following gene-specific primers: forward primers H4.11 (5′-ATTTCAAAAAACAGAAAAAC-3′), H4.12 (5′-CAGCCCAAGAAAAAAAATAC-3′), H4.13 (5′-CGCATCCCGCAAACACACAC-3′), and H4.14 (5′-TCACCCAACACTCTCTCAAC-3′) with reverse primer H4.10 for histone H4.1 and forward primers H4.21 (5′-TGTGTGGGCTCGTCTGGAAT-3′), H4.22 (5′-GCCCCTCCCCGACAACACAT-3′), H4.23 (5′-AGGAAAAGAAAAGCACAAAC-3′), and H4.24 (5′-ACACACACACTCACACTCAC-3′) with reverse primer H4.20 for histone H4.2. Primers H4.11 to H4.14 and H4.21 to H4.24 anneal to regions upstream of the respective ATG start codons, while primers H4.10 and H4.20 anneal to the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR). PCR with these primers was carried out at an annealing temperature of 50°C.

Vector construction and transformation of M. alpina.

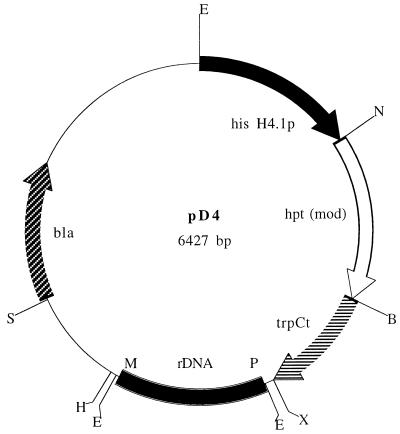

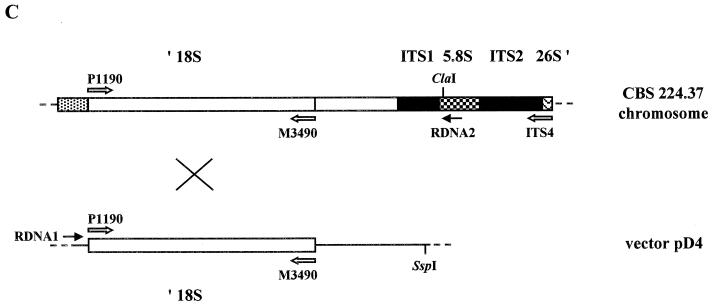

Vectors pAN7-1 (25) and pAN-CCG were kindly supplied by P. Punt, TNO, Zeist, The Netherlands, and J. Springer, ATO-DLO, Wageningen, The Netherlands, respectively. pAN7-1 contained the A. nidulans glyceraldehyde-3′-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpdA) promoter, the Escherichia coli hygromycin B resistance gene (hpt), and the A. nidulans N-(5′-phosphoribosyl)anthranilate isomerase (trpC) transcription terminator. In plasmid pAN-CCG, the Cryptococcus curvatus gpdA promoter drove expression of a modified hygromycin B resistance gene (hptmod) and was derived from vector pANH2-1 (33). A 1-kb fragment containing the M. alpina histone H4.1 promoter region was amplified from a CBS 528.72 histone H3.1–H4.1 genomic clone using forward primer SHG1 (5′-AAGAATTCAAGCGAAAGAGAGATATGAAACA-3′) and reverse primer SHG2 (5′-AACCATGGATTGTTGAGAGAGTGTTGGGTG-3′) at an annealing temperature of 56°C. Primer SHG1 annealed at position −999 to −977 with respect to the histone H4.1 ATG start codon (+1), while primer SHG2 annealed at position −2 to −23. These primers contained EcoRI and NcoI restriction sites (underlined), respectively, which were subsequently used in replacing the C. curvatus gpdA promoter EcoRI-NcoI fragment of pAN-CCG with the M. alpina histone H4.1 promoter to produce vector pAN-MAH. An rDNA region of approximately 1 kb, containing part of the 18S rRNA gene, was amplified from M. alpina CBS 528.72 genomic DNA using forward primer P1190 (5′-CAATTGGAGGGCAAGTCTGG-3′) and reverse primer M3490 (5′-TCAGTGTAGCGCGCGTGCGG-3′) at an annealing temperature of 54°C. Another reverse primer, ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATG-3′), was used with forward primer P3490, whose sequence was complementary to that of M3490, to amplify the rDNA region downstream of P1190–M3490. Primers P1190, M3490, and ITS4 were originally designed from the S. cerevisiae 18S rRNA gene sequence (6, 15) and were kindly supplied by S. James, Institute of Food Research (IFR), Norwich, United Kingdom. The 931-bp P1190–M3490 18S rDNA fragment was cloned into pCR 2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and subsequently inserted as a 1,041-bp XbaI-HindIII fragment into pAN-MAH to create vector pD4 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Map of the M. alpina transformation vector pD4. The 1-kb EcoRI-NcoI M. alpina histone H4.1 promoter fragment from strain CBS 528.72 also contains the histone H3.1 promoter and ORF. The hygromycin B resistance gene is the modified version (hptmod) which lacks the internal EcoRI and NcoI sites that are present in the wild-type gene of pAN7-1 (33). The 700-bp BamHI-XbaI fragment contains the A. nidulans trpC transcription terminator region (trpCt). The positions of the two rDNA primers P1190 and M3490, which were used to generate the M. alpina 18S rDNA fragment, are indicated as P and M, respectively. bla, ampicillin resistance gene. Restriction sites: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NcoI; S, SspI; X, XbaI.

Protoplasts of M. alpina CBS 224.37 were produced by treating 4- to 6-day-old PDB-grown mycelium with “streptozyme” from Streptomyces sp. strain no. 6 (34). Approximately 10 g (wet weight) of mycelium in 15 ml of protoplasting buffer (1 M sorbitol–10 mM NaH2PO4-Na2HPO4 [pH 6.5]) was incubated with 4 ml of filter-sterilized “streptozyme” in 20 mM NaH2PO4–Na2HPO4, pH 6.5, for 1 to 2 h with gentle shaking (60 to 80 rpm) at 25°C. Protoplasts were harvested through sterile polyallomer wool and concentrated by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. After a wash in 50 ml of ice-cold STC buffer (1 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM CaCl2 [pH 7.5]), the protoplasts were resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. A total of 2 × 107 protoplasts in 100 μl of STC buffer were incubated with 5 μg of vector DNA for 25 min at room temperature. A 1.25-ml volume of PEG–CaCl2 (60% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol with an MW of 4,000 to 6,000, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM CaCl2 [pH 7.5]) was added gradually, and the mixture was incubated for a further 20 min at room temperature. PEG was diluted by the addition of 10 volumes of STC buffer, and protoplasts were harvested by centrifugation. Protoplasts were resuspended in 1 ml of STC buffer, and 200 μl of this mixture was embedded in 12 ml of molten (50°C) potato dextrose agar (PDA) containing 1 M sorbitol. Following 2 days' incubation at 12°C, a 12-ml top layer of PDA–1 M sorbitol, containing 200 μg of hygromycin B ml−1, was poured onto each plate, and incubation was continued at 25°C for 5 to 7 days. Putative transformants were transferred onto PDA plates containing 300 to 1,000 μg of hygromycin B ml−1.

Transformants were checked by PCR using the forward primer HYGR1 (5′-AGCGAGAGCCTGACCTATTG-3′) and the reverse primer HYGR2 (5′-TCGAAGTAGCGCGTCTGCTG-3′) at an annealing temperature of 58°C, which generate an internal hptmod fragment of 500 bp. Genomic DNA was isolated from transformants using the modified QIAGEN method described previously (38). The chromosomal rDNA site of integration of plasmid pD4 was verified using the vector-specific forward primer RDNA1 (5′-ACAGGTACACTTGTTTAGAG-3′), which anneals just upstream of the XbaI site in the A. nidulans trpC terminator region, and reverse primer RDNA2 (5′-CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATG-3′). RDNA2 anneals to the 5.8S rRNA gene, which lies downstream of the 18S rDNA region and which is absent in pD4. Primers RDNA1 and RDNA2 were used at an annealing temperature of 54°C and were expected to generate a fragment of 1,569 bp with CBS 224.37 transformants.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The following sequences have been submitted to the EMBL database: 18S–5.8S rDNA regions from M. alpina strains CBS 528.72 (AJ271629) and CBS 224.37 (AJ271630), and histone H3.1–H4.1 genes (AJ249812) and histone H3.2–H4.2 genes (AJ249813) from M. alpina strain CBS 528.72.

RESULTS

Vectors containing heterologous promoters failed to transform M. alpina.

Six M. alpina strains were screened for sensitivity to hygromycin B (100 to 1,000 μg ml−1), but all except CBS 224.37 were resistant to the antibiotic. This strain was sensitive to 100 to 200 μg of hygromycin B ml−1 and was therefore chosen as the most suitable transformation host. Initial experiments using vectors pAN7-1 and pAN-CCG, in which expression of the hygromycin B resistance gene was driven by heterologous gpdA promoters from A. nidulans and C. curvatus, proved unsuccessful (Table 1). The use of a homologous M. alpina promoter was therefore investigated, and the histone H4 promoter was chosen because of previous successes in other organisms (12, 17).

TABLE 1.

Transformation frequencies of M. alpina CBS 224.37 and transformant stability

| Vector | No. of primary transformants per 5 μg of vector DNAa | Maximum hygromycin B resistance level (μg ml−1) | % Stable transformantsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| pAN7-1 | 0 | —c | — |

| 0 | — | — | |

| 0 | |||

| pAN-CCG | 0 | — | — |

| 0 | — | — | |

| 0 | — | — | |

| pAN-MAH | 0 | — | — |

| 2 | 350 | 0 | |

| 0 | — | — | |

| pD4 | 8 | 1,000 | 75 |

| 10 | 1,000 | 70 |

Transformants from two or three independent experiments were selected initially on 100 μg of hygromycin B ml−1, except for pAN-MAH (350 μg ml−1).

Determined following first subculturing on 300 to 1,000 μg of hygromycin B ml−1.

—, not applicable.

Isolation and characterization of the histone H3–H4 gene pairs from M. alpina CBS 528.72.

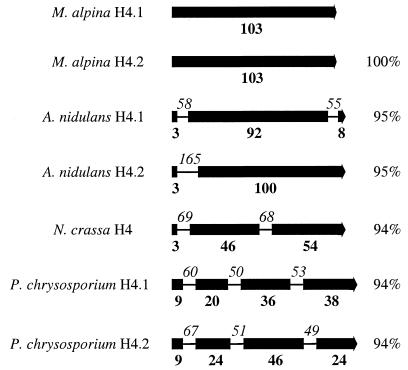

Degenerate oligonucleotide primers were designed from highly conserved regions of fungal histone H4 proteins where sequence degeneracy was minimized. A 206-bp DNA fragment (H3H2) was amplified from M. alpina CBS 528.72 genomic DNA, the predicted translation product of which had about 94% amino acid identity to a number of histone H4 proteins. This fragment was used to probe a Southern blot of genomic DNA from CBS 528.72 which had been digested with a range of restriction enzymes. The BamHI digest gave two strongly hybridizing bands of approximately 7.2 and 4.3 kb and a fainter band of about 9 to 11 kb (data not shown). Subsequently, a BamHI genomic DNA library of CBS 528.72 was screened with probe H3H2, and positive clones were shown to contain one of two inserts. On sequencing, these were found to be 7,139 and 4,257 bp, respectively, and encoded pairs of histone H3 and histone H4 proteins with high amino acid identity (92 to 95%) to histone H3 and H4 proteins from other organisms (Fig. 2). Unlike all other histone genes isolated so far from filamentous fungi, the four M. alpina genes lacked introns.

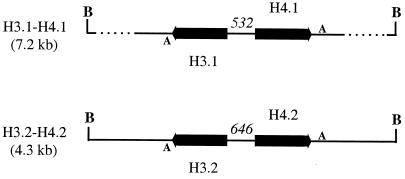

FIG. 2.

Organization of the two pairs of histone H3–H4 genes in M. alpina CBS 528.72. Heavy arrows indicate the position and direction of each ORF. The sizes of the promoter regions in nucleotides are given in italics. A, the consensus poly(A) addition signal AATAAA; B, BamHI site.

The two genomic clones did not contain other histone genes, such as those encoding histone H2A or H2B. The 7.2-kb histone H3.1–H4.1 clone did, however, contain two other genes, one encoding a putative 60S ribosomal protein (rpl27A; EMBL accession number AJ249749) located downstream of the histone H3.1 gene, and the other encoding a putative thioredoxin II-like protein (EMBL accession number AJ249750) located downstream of the histone H4.1 gene. Each gene pair was separated by a promoter region from which the genes were divergently transcribed. This intergenic region was 532 bp for the H3.1–H4.1 gene pair and 646 bp for the H3.2–H4.2 gene pair. The pairs of encoded histone H3 or H4 proteins were identical in amino acid sequence, and their open reading frames (ORFs) shared 93 and 97% DNA sequence identity, respectively. The promoters, 5′-UTRs, and 3′-UTRs of each pair of histone H3 or H4 genes showed much less DNA identity, although there were small stretches of 60 to 85 nucleotides (nt) which were about 75 to 80% identical. RT-PCR analysis of transcripts from the two histone H4 genes with gene-specific primer sets, H4.10 to H4.14 and H4.20 to H4.24, indicated that the putative transcription start point for each gene was 50 to 70 nt upstream of the ATG start codon (data not shown).

Expression of the two histone H4 genes in M. alpina.

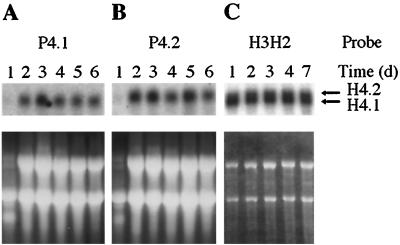

Two histone H4 gene-specific probes, P4.1 and P4.2, were synthesized from the 3′-UTRs of the respective histone H4.1 and H4.2 genes for use in Northern analysis of strain CBS 528.72. Probes P4.1 and P4.2 were 91 and 194 bp, respectively, in size and 75% identical at the DNA level over a 50-bp region. In dot blots, each probe did not cross-hybridize significantly with the opposing histone H4 gene, thus confirming their specificity (data not shown). In Fig. 3A and B, the gene-specific probes detected histone H4 transcripts which differed slightly in size. From analyzing the two genomic DNA sequences and estimating the approximate lengths of the 5′- and 3′-UTRs, the expected transcript sizes for histone H4.1 and H4.2 were 600 and 640 nt, respectively. This agreed with the sizes of the two transcripts measured on Northern blots. When the experiment was repeated using poly(A)-enriched RNA and the H3H2 probe, which had 99 to 100% DNA identity with the histone H4.1 and H4.2 ORFs, both transcripts could be visualized as two closely migrating bands of approximately equal intensity (Fig. 3C). In addition, probe H3H2 hybridized to the same two transcripts from a number of other M. alpina strains, including CBS 224.37 (P. Wongwathanarat and A. T. Carter, unpublished data).

FIG. 3.

Transcription of the two histone H4 genes from M. alpina CBS 528.72. (A and B) Total RNA (20 μg per lane), which had been isolated from PDB-grown cultures harvested on the days indicated, was probed with the histone H4.1 and H4.2 gene-specific 3′-UTR probes P4.1 and P4.2, respectively. (C) Cultures were grown in S2GYE broth, and poly(A)-enriched RNA (approximately 0.5 μg per lane) was probed with the H3H2 histone H4 fragment, which hybridizes to both transcripts. The lower panels show the ethidium bromide-stained gels prior to Northern blotting.

Transformation of M. alpina strain CBS 224.37.

Replacement of the C. curvatus gpdA promoter in pAN-CCG with the homologous M. alpina histone H4.1 promoter in vector pAN-MAH allowed transient growth of two transformants at an antibiotic concentration of 350 μg ml−1 (Table 1). PCR with genomic DNA from these transformants, using the hpt-specific primers HYGR1 and HYGR2, confirmed the presence of the hptmod gene, but subsequent subculturing on media containing hygromycin B showed that they had become sensitive to the antibiotic. This was confirmed by failure to amplify the hptmod fragment from genomic DNA of these transformants grown without hygromycin B selection. The stability of transformants was improved greatly by incorporating a homologous M. alpina rDNA region into pAN-MAH to create plasmid pD4 (Fig. 1). A transformation frequency of 1 to 2 transformants · μg of vector DNA−1 was obtained with pD4, and the majority of these transformants remained resistant to up to 1 mg of hygromycin B ml−1 after several subculturings in the presence of the antibiotic (Table 1). A proportion of pD4 transformants (25 to 30%) still displayed an unstable phenotype under antibiotic selection.

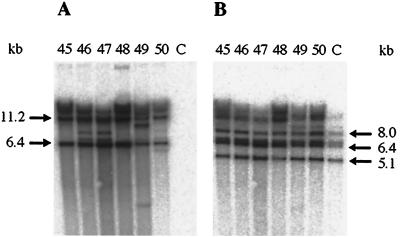

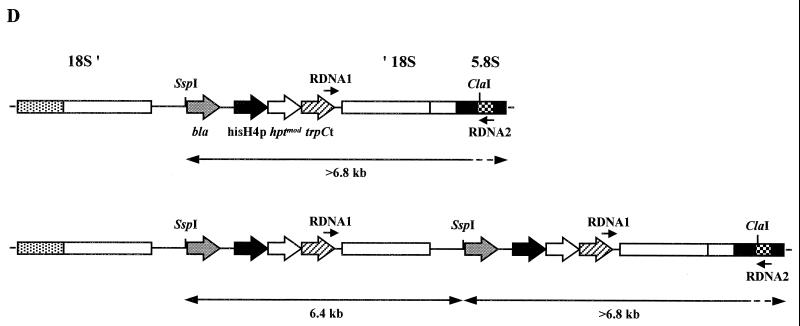

The presence of the hptmod gene in pD4 transformants was confirmed by PCR with primers HYGR1 and HYGR2 and by Southern blotting (Fig. 4). When probed with the HYGR1–HYGR2 hptmod fragment, SspI genomic DNA digests from independent, stable transformants gave very similar, but not identical, hybridization patterns (Fig. 4A). SspI cuts vector pD4 once, near the bla gene (Fig. 1), and does not cut in the 1,899-bp P1190–ITS4 rDNA region of CBS 224.37. The two strongly hybridizing bands of approximately 6.4 and 11.2 kb suggested that two copies of pD4 had integrated in tandem into the chromosome in each transformant (Fig. 4C and D). Probing ClaI digests with the hptmod fragment gave a single, diffuse signal at about 20 kb in each transformant tested (data not shown). ClaI does not cut in pD4 but does cut the P1190–ITS4 rDNA region once in the 5.8S rRNA gene (within primer RDNA2). The untransformed host strain CBS 224.37 displayed no positive signals in PCR with primers HYGR1 and HYGR2 or when probed for the presence of the hptmod gene. All transformants and the untransformed control gave an identical pattern after probing with the P1190–M3490 rDNA fragment (Fig. 4B). For each stable transformant, PCR with the vector-specific primer RDNA1 and the chromosome-specific primer RDNA2 generated a fragment of about 1,600 bp, which, on sequencing, confirmed that pD4 had indeed integrated into at least one of the rDNA loci (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

(A and B) Southern blots showing the presence of integrated pD4 in transformants of M. alpina CBS 224.37, probed with hptmod fragment HYGR1–HYGR2 (A) and rDNA regions, probed with the 18S rDNA fragment P1190–M3490 (B). Genomic DNA (approximately 5 μg) from independent, stable transformants 45 to 50 from one transformation experiment and the untransformed control (lanes C) was digested with SspI. Phosphorimage exposures for panels A and B, 1 h and 10 min, respectively. (C) Diagram of a single-crossover integration event in the 18S rDNA region between the circular vector pD4 and the chromosomal locus of CBS 224.37 (not to scale). Annealing positions of the three rDNA primers, P1190, M3490 and ITS4, and of the two PCR primers, RDNA1 and RDNA2, are indicated. The chromosomal rDNA locus represented shows part of one rDNA repeat unit containing the 3′ end of the 18S rDNA region (′ 18S), the two internal transcribed sequences (ITS1 and ITS2), the complete 5.8S rDNA region, and the extreme 5′ end of the 26S rDNA region (26S ′). (D) Diagram showing the outcome of integration of one or two copies of pD4 into the 18S rDNA region of CBS 224.37 (not to scale). Annealing positions of the two PCR primers, RDNA1 and RDNA2, are indicated. Double-headed arrows indicate predicted SspI Southern fragments hybridizing to the hptmod probe.

DISCUSSION

M. alpina is a commercially important producer of polyunsaturated fatty acid-rich oil, and in this paper we have described the first successful genetic transformation of this zygomycete. Mucor circinelloides was the first member of this fungal group to be transformed (35), and this was followed by similar reports for a number of other zygomycetes (4, 29, 30). High transformation frequencies of up to 104 transformants · μg of vector DNA−1, which are associated with the presence of a plasmid sequence promoting autonomous replication, have been reported for M. circinelloides (2, 35), but a number of integration vectors have also been described (1, 5, 36). In the present study, the transformation frequency of M. alpina was low, and there was no evidence for efficient, extrachromosomal plasmid replication. Indeed, plasmid pAN-MAH only conferred transient antibiotic resistance as a result of failing either to replicate extrachromosomally or to integrate into the chromosome. When a homologous rDNA region was incorporated into the vector, integration into the chromosome was promoted and resulted in stable propagation of the hygromycin resistance phenotype in most cases. The presence of the rDNA fragment in the vector would be expected to increase the chance of homologous integration into the chromosome because, as in other fungi (9, 23), there are probably 150 to 200 tandemly repeated copies of the rDNA locus per haploid genome in M. alpina, with each copy representing a potential integration target.

In S. cerevisiae, rDNA-containing plasmids integrate with only low copy numbers, characteristic of standard yeast integrating vectors, unless the selection marker used has a defective promoter (20). Even in these yeast transformants with amplified, integrated vector copies, the number of different rDNA integration sites is low. In the present study, the rDNA-containing vector pD4 integrated only at a few chromosomal sites in M. alpina, as determined by Southern blotting, and at least one of these was an rDNA locus. The rDNA site of integration was confirmed by sequencing the PCR product obtained with primers RDNA1 and RDNA2, which was generated only in the stable transformants. Probing Southern blots with the P1190–M3490 18S rDNA fragment could not distinguish between pD4 transformants and the untransformed control, but this was most likely due to the much higher copy number of endogenous rDNA repeats swamping out the signal(s) from the 18S rDNA region of the integrated vector. The presence of extrachromosomally replicating plasmid could not be detected in the pD4 transformants when DNA digested with ClaI, which does not cut in the vector, was probed with the hptmod fragment.

This is one of the few examples in which an rDNA fragment has been used to target vector integration in a filamentous fungus. In A. nidulans, incorporation of an rDNA region into plasmids resulted in homologous integration of a proportion of vector molecules at the rDNA locus, but the overall transformation frequency was unaffected (31, 37). A proportion of the M. alpina pD4 transformants (25 to 30%) were unstable, however, and became sensitive to hygromycin due to the failure of plasmid integration or to the loss or rearrangement of the integrated vector, which is a common occurrence in other zygomycete transformation systems (5, 40). The rearrangement of some integrated pD4 molecules may also explain the varied pattern of faintly hybridizing bands observed in the Southern analysis of stable transformants (Fig. 4A).

Two pairs of histone H3 and H4 genes were isolated from M. alpina. Pairs of particular histone genes are common in fungi, but the pairs tend not to be linked as in higher organisms (10, 21; N. J. Belshaw, M. J. C. Alcocer, C. S. M. Furniss, and D. B. Archer, submitted for publication). Exceptions are the histone H2A.2–H2B.2 (HTA2-HTB2) and histone H3.1–H4.1 (HHT1–HHF1) gene pairs of S. cerevisiae (28), which are located on either side of the centromere on chromosome II but are separated by 18.5 kb. Unlike all other histone genes isolated from filamentous fungi, the four M. alpina genes lacked introns (Fig. 5). This is more like the structural organization of histone genes from yeasts and higher organisms, which also lack introns. All other genes described in M. alpina, however, do contain introns (8, 38), some of which are quite large (18; D. A. MacKenzie and A. T. Carter, unpublished data). The significance, if any, of the lack of introns in the M. alpina histone genes has yet to be determined. All four genes contained the consensus poly(A) addition signal AATAAA (13) approximately 100 to 200 nt downstream from the translation stop codon, indicating that these transcripts are probably polyadenylated, in common with all other histone mRNAs from fungi.

FIG. 5.

Intron positions in the histone H4 genes from a number of filamentous fungi. Solid boxes represent the protein coding regions, with the corresponding number of amino acid residues in each region given in boldface below each box. Intron positions are shown as lines, with the size in nucleotides given in italics above each line. The percent amino acid identity of each encoded protein with the M. alpina CBS 528.72 histone H4.1 protein is given on the right.

Analysis of the two intergenic promoter regions for the presence of putative regulatory sequences revealed that both contained AT-rich stretches, which are common in other histone gene promoters, and a number of putative TATA boxes, which are found in some filamentous fungal promoters (13). Transcripts from the two histone H4 genes were produced at approximately the same level during vegetative growth, indicating that either histone H4 promoter could be used in transformation vectors. The presence of the histone H3.1 promoter and ORF in vector pD4 appeared not to affect the efficiency of hpt expression from the histone H4.1 promoter in M. alpina transformants. This was in contrast to the situation in P. chrysosporium, where integrating transformation vectors containing the histone H3 gene in addition to the histone H4 promoter were unable to express antibiotic resistance, probably by a mechanism involving DNA methylation (12).

In conclusion, we have shown that M. alpina can be genetically transformed to hygromycin B resistance. This now offers the prospect of using recombinant methods to modify the fatty acid composition of the oil from this commercially important organism, by overexpressing or deleting genes involved in the biosynthetic pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, by the BBSRC Cell Engineering Link Programme, and by a studentship from the Thai Government to P.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnau J, Strøman P. Gene replacement and ectopic integration in the zygomycete Mucor circinelloides. Curr Genet. 1993;23:542–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00312649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benito E P, Díaz-Mínguez J M, Iturriaga E A, Campuzano V, Eslava A P. Cloning and sequence analysis of the Mucor circinelloides pyrG gene encoding orotidine-5′-monophosphate decarboxylase: use of pyrG for homologous transformation. Gene. 1992;116:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilgin M, Dedeoglu D, Omirulleh S, Peres A, Engler G, Inzé D, Dudits D, Fehér A. Meristem, cell division and S phase-dependent activity of wheat histone H4 promoter in transgenic maize plants. Plant Sci. 1999;143:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmester A. Analysis of the gene for the elongation factor 1α from the zygomycete Absidia glauca. Use of the promoter region for constructions of transformation vectors. Microbiol Res. 1995;150:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0944-5013(11)80035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burmester A, Wöstemeyer A, Wöstemeyer J. Integrative transformation of a zygomycete, Absidia glauca, with vectors containing repetitive DNA. Curr Genet. 1990;17:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai J, Roberts I N, Collins M D. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the ascomycetous yeast genera Brettanomyces, Debaromyces, Dekkera, and Kluyveromyces deduced by small-subunit rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:542–549. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Certik M, Sakuradani E, Shimizu S. Desaturase-defective fungal mutants: useful tools for the regulation and overproduction of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:500–505. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Certik M, Sakuradani E, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Characterization of the second form of NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase gene from arachidonic acid-producing fungus Mortierella alpina 1S-4. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;88:667–671. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(00)87098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cihlar R L, Sypherd P S. The organization of the ribosomal RNA genes in the fungus Mucor racemosus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:793–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehinger A, Denison S H, May G S. Sequence, organization and expression of the core histone genes of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:416–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00633848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman K B, Karns L R, Lutz K A, Smith M M. Histone H3 transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by multiple cell cycle activation sites and a constitutive negative regulatory element. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5455–5463. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gessner M, Raeder U. A histone H4 promoter for expression of a phleomycin-resistance gene in Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Gene. 1994;142:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurr S J, Unkles S E, Kinghorn J R. The structure and organization of nuclear genes of filamentous fungi. In: Kinghorn J R, editor. Gene structure in eukaryotic microbes. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1987. pp. 93–139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y-S, Chaudhary S, Thurmond J M, Bobik E G, Jr, Yuan L, Chan G M, Kirchner S J, Mukerji P, Knutzon D S. Cloning of Δ12- and Δ6-desaturases from Mortierella alpina and recombinant production of γ-linolenic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Lipids. 1999;34:649–659. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James S A, Collins M D, Roberts I N. Use of an rRNA internal transcribed spacer region to distinguish phylogenetically closely related species of the genera Zygosaccharomyces and Torulaspora. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:189–194. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones D. A note on Streptomyces no. 6, a chitosanase-producing actinomycete. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1992;61:79–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00572126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn R W, Andersen B H, Brunk C F. Transformation of Tetrahymena thermophila by microinjection of a foreign gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9295–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi M, Sakuradani E, Shimizu S. Genetic analysis of cytochrome b5 from arachidonic acid-producing fungus, Mortierella alpina 1S-4: cloning, RNA editing and expression of the gene in Escherichia coli, and purification and characterization of the gene product. J Biochem. 1999;125:1094–1103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leman J. Oleaginous microorganisms: an assessment of the potential. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1997;43:195–243. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes T S, Hakkaart G-J A J, Koerts B L, Raué H A, Planta R J. Mechanism of high-copy-number integration of pMIRY-type vectors into the ribosomal DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1991;105:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90516-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto S, Yanagida M. Histone gene organization of fission yeast: a common upstream sequence. EMBO J. 1985;4:3531–3538. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaelson L V, Lazarus C M, Griffiths G, Napier J A, Stobart A K. Isolation of a Δ5-fatty acid desaturase gene from Mortierella alpina. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19055–19059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petes T D. Meiotic mapping of yeast ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid on chromosome XII. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:185–192. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.1.185-192.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper P W. Measurement of transcription. In: Johnston J R, editor. Molecular genetics of yeast. A practical approach. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Punt P J, Oliver R P, Dingemanse M A, Pouwels P H, van den Hondel C A M J J. Transformation of Aspergillus based on the hygromycin B resistance marker from Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;56:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratledge C. Single cell oils—have they a biotechnological future? Trends Biotechnol. 1993;11:278–284. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(93)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakuradani E, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Δ6-Fatty acid desaturase from an arachidonic acid-producing Mortierella fungus—gene cloning and its heterologous expression in a fungus, Aspergillus. Gene. 1999;238:445–453. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith M M, Andrésson O S. DNA sequences of yeast H3 and H4 histone genes from two non-allelic gene sets encode identical H3 and H4 proteins. J Mol Biol. 1983;169:663–690. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suárez T, Eslava A P. Transformation of Phycomyces with a bacterial gene for kanamycin resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:120–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00322453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaya N, Yanai K, Horiuchi H, Ohta A, Takagi M. Cloning and characterization of the Rhizopus niveus leu1 gene and its use for homologous transformation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:448–452. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilburn J, Scazzochio C, Taylor G G, Zabicky-Zissman J H, Lockington R A, Davies R W. Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene. 1983;26:205–221. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trappe R, Doenecke D, Albig W. The expression of human H2A-H2B histone gene pairs is regulated by multiple sequence elements in their joint promoters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1446:341–351. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van de Rhee M D, Graça P M A, Huizing H J, Mooibroek H. Transformation of the cultivated mushroom, Agaricus bisporus, to hygromycin B resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:252–258. doi: 10.1007/BF02174382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Heeswijck R. The formation of protoplasts from Mucor species. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1984;49:597–609. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Heeswijck R, Roncero M I G. High frequency transformation of Mucor with recombinant plasmid DNA. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1984;49:691–702. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada M, Beppu T, Horinouchi S. Integrative transformation of the zygomycete Rhizomucor pusillus by homologous recombination. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:652–657. doi: 10.1007/s002530050743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wernars K, Goosen T, Wennekes L M J, Visser J, Bos C J, van den Broek H W J, van Gorcom R F M, van den Hondel C A M J J, Pouwels P H. Gene amplification in Aspergillus nidulans by transformation with vectors containing the amdS gene. Curr Genet. 1985;9:361–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00421606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wongwathanarat P, Michaelson L V, Carter A T, Lazarus C M, Griffiths G, Stobart A K, Archer D B, MacKenzie D A. Two fatty acid Δ9-desaturase genes, ole1 and ole2, from Mortierella alpina complement the yeast ole1 mutation. Microbiology. 1999;145:2939–2946. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woudt L P, Pastink A, Kempers-Veenstra A E, Jansen A E M, Mager W H, Planta R J. The genes coding for histone H3 and H4 in Neurospora crassa are unique and contain intervening sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:5347–5360. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.16.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanai K, Horiuchi H, Takagi M, Yano K. Preparation of protoplasts of Rhizopus niveus and their transformation with plasmid DNA. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:2689–2696. [Google Scholar]