Keywords: acute kidney injury, heat stress, heat waves, kidney function

Abstract

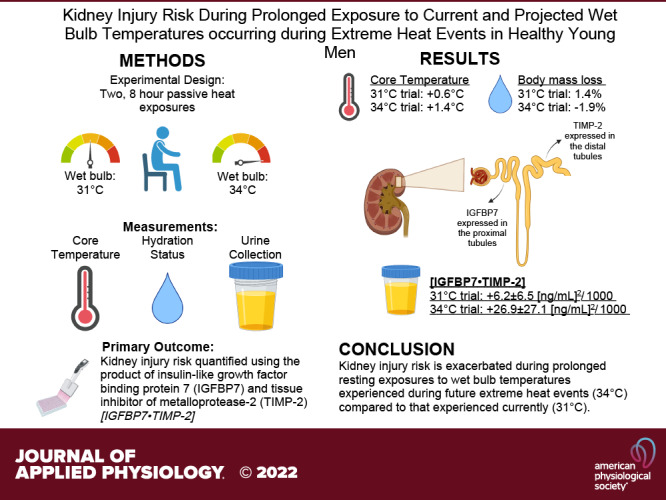

Wet bulb temperatures (Twet) during extreme heat events are commonly 31°C. Recent predictions indicate that Twet will approach or exceed 34°C. Epidemiological data indicate that exposure to extreme heat events increases kidney injury risk. We tested the hypothesis that kidney injury risk is elevated to a greater extent during prolonged exposure to Twet = 34°C compared with Twet = 31°C. Fifteen healthy men rested for 8 h in Twet = 31 (0)°C and Twet = 34 (0)°C. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2), and thioredoxin 1 (TRX-1) were measured from urine samples. The primary outcome was the product of IGFBP7 and TIMP-2 ([IGFBP7·TIMP-2]), which provided an index of kidney injury risk. Plasma interleukin-17a (IL-17a) was also measured. Data are presented at preexposure and after 8 h of exposure and as mean (SD) change from preexposure. The increase in [IGFBP7·TIMP-2] was markedly greater at 8 h in the 34°C [+26.9 (27.1) (ng/mL)2/1,000) compared with the 31°C [+6.2 (6.5) (ng/mL)2/1,000] trial (P < 0.01). Urine TRX-1, a marker of renal oxidative stress, was higher at 8 h in the 34°C [+77.6 (47.5) ng/min] compared with the 31°C [+16.2 (25.1) ng/min] trial (P < 0.01). Plasma IL-17a, an inflammatory marker, was elevated at 8 h in the 34°C [+199.3 (90.0) fg/dL; P < 0.01] compared with the 31°C [+9.0 (95.7) fg/dL] trial. Kidney injury risk is exacerbated during prolonged resting exposures to Twet experienced during future extreme heat events (34°C) compared with that experienced currently (31°C), likely because of oxidative stress and inflammatory processes.

NEW AND NOTEWORTHY We have demonstrated that kidney injury risk is increased when men are exposed over an 8-h period to a wet bulb temperature of 31°C and exacerbated at a wet bulb temperature of 34°C. Importantly, these heat stress conditions parallel those that are encountered during current (31°C) and future (34°C) extreme heat events. The kidney injury biomarker analyses indicate both the proximal and distal tubules as the locations of potential renal injury and that the injury is likely due to oxidative stress and inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Extreme heat events (e.g., heat waves) pose an imminent threat to public health (1, 2), particularly given the projected rise in mean temperatures throughout the world, including in the United States (3). The frequency, intensity, duration, and geographical area of extreme heat events are anticipated to precede rises in global temperatures (4). Recent evidence indicates that the top causes of excess hospital admissions during extreme heat events are 1) fluid and electrolyte disturbances (e.g., dehydration) and 2) kidney injury, which often occurs secondary to dehydration (5, 6). Extreme heat event severity is predicted to worsen such that wet bulb temperatures (Twet) in many locations across the globe could approach 34–35°C, the limit of thermal compensability (i.e., the threshold at which autonomic temperature regulation is not sufficient to achieve heat balance) during resting conditions (3, 7, 8). Notably, however, although Twet during current extreme heat events approaches (but rarely exceeds) ∼31°C (3), this relatively lower Twet has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and many more hospitalizations (9), many of which are due to kidney injury (5, 6).

Elevations in Twet can bring about hyperthermia (i.e., an increase in core body temperature) and dehydration (i.e., a hypovolemic and hyperosmotic state caused by sweating and/or inadequate fluid intake) (10). Our laboratory has identified that hyperthermia and/or dehydration increase the risk of developing kidney injury during physical work in the heat in young, healthy adults (6, 11–14). In the context of conducting controlled human subject laboratory-based studies, kidney injury risk is perhaps best examined utilizing a panel of urinary biomarkers [e.g., neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), etc.], which enable investigation of the renal pathophysiological consequences of hyperthermia and/or dehydration (6, 14). This approach avoids the limitations associated with more traditional clinical assessments of kidney injury that are invalid during heat stress and/or body water depletion (e.g., serum creatinine- and urine flow rate-based measurements) (6, 14). Notably, to date, the product of urinary markers of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2) ([IGFBP7·TIMP-2]) is the only US Food and Drug Administration-approved biomarker with an indication for assessing kidney injury risk in clinical practice (6, 15). By employing this urinary kidney injury biomarker approach, the primary purpose of the present study was to examine risk of kidney injury during prolonged resting exposure to conditions that closely parallel the current Twet [i.e., 31°C (3)] and projected Twet [i.e., 34°C (3)] experienced during extreme heat events. We tested the hypothesis that an 8-h resting exposure to a Twet of 31°C without access to fluids increases [IGFBP7·TIMP-2] and that increases in [IGFBP7·TIMP-2] are further exacerbated during exposure to a Twet of 34°C.

A secondary purpose of the present study was to examine the mechanisms by which prolonged extreme resting heat exposure increases kidney injury risk. The increased risk of kidney injury during heat exposure is believed to be initiated by hyperthermia- and/or dehydration-mediated reductions in kidney blood flow that, in the presence of an increased demand for sodium reabsorption (an ATP dependent process), create an oxygen supply-demand mismatch in the renal tubules (16, 17). Indeed, rodent models of heat stress-induced kidney injury have identified that oxidative stress is likely mediated by a reduction in functional mitochondrial mass within the kidneys, thereby disrupting ATP generation via oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport chain activity (18). The subsequent ATP depletion results in a relative renal ischemia and activation of inflammatory pathways (6). Therefore, we also tested the hypothesis that the increase in kidney injury risk would be contributed to by renal oxidative stress and inflammation.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University at Buffalo. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki, except for registration in a database. Before participating in any study-related activities, each subject was fully informed of the experimental procedures and possible risks before providing informed written consent. A portion of the data presented here was previously published in a manuscript that tested a unique hypothesis (10).

Subjects

Fifteen healthy men participated in the study, and subject characteristics are presented in Table 1. All subjects self-reported to be nonsmokers, not taking medications, and free of any known cardiovascular, metabolic, neurological, or renal diseases. Additionally, subjects were not heat acclimated and self-reported to regularly engage in physical activity.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Age, yr | 23 [20, 32] |

| Height, cm | 179 [166, 198] |

| Weight, kg | 84.5 [59.5, 134.4] |

| Body surface area, m2 | 2.0 [1.7, 2.7] |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.0 [21.6, 34.3] |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 63 [48, 76] |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 117 [104, 126] |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75 [62, 94] |

Subject characteristics and anthropometrics collected during the screening visit. Values are presented as mean [min, max].

Study Design

Subjects visited the laboratory on three occasions separated by at least 7 days to minimize any potential carryover effects. The first visit involved screening and familiarization, and the second and third visits were experimental trials. The experimental trials differed only with regard to the ambient conditions and consisted of 8 h of seated exposure to warm and very humid environments. In one condition Twet was 31 (0)°C [dry bulb temperature: 32 (0)°C, relative humidity: 95 (2)%], and in the other condition Twet was 34 (0)°C [dry bulb temperature: 35 (0)°C, relative humidity: 96 (2)%] The experimental trials were completed in a randomized order, and subjects were blinded to the experimental condition. All experimental trials were completed throughout the calendar year in Buffalo, NY, a climate that has been shown to induce minimal heat acclimatization (19).

Subjects avoided exercise, alcohol, and caffeine for at least 12 h before arrival at the laboratory, and all subjects were instructed to eat a light meal ∼2 h before arriving. Upon arrival, subjects provided a urine sample by completely voiding their bladder in a collection urinal. Euhydration, defined as a urine specific gravity (USG) ≤ 1.020 (20), was confirmed [31°C: 1.010 (0.006) and 34°C: 1.009 (0.006); P = 0.22]. After urine collection, subjects drank 250 mL of cool tap water to promote urine production over the subsequent 60 min. Subjects then sat and rested for 60 min. During this rest period, a baseline venous blood sample was obtained. After 60 min, subjects voided their bladder in a separate collection urinal to establish a baseline urine flow rate over this 60-min period. After this baseline urine sample, the preexposure data were recorded in a temperate thermal environment [dry bulb temperature: 26 (1)°C; 39 (14)% relative humidity], after which the 8-h exposure commenced, with the data collected as indicated below.

Subjects wore a standard uniform of long pants, a short-sleeved cotton t-shirt, and athletic shoes at all times. The estimated insulation of the clothing ensemble is 0.47 clo (21). Both experimental trials commenced in the morning (between 0800 and 0900) and took place at the same time of day to control for circadian effects. Subjects remained seated on a mesh chair throughout the duration of each trial. Subjects were not allowed to eat or drink at any time during the experimental trials.

Instrumentation and Measurements

Dry bulb temperature and relative humidity were measured (Kestrel 3000 Weather Meter; Kestrel Instruments, Boothwyn, PA) every 10 min and are presented as mean (SD) across each 8-h trial. Height and body mass were measured with a stadiometer and scale (Sartorius, Bohemia, NY). Nude body mass was measured before and after exposure.

Core temperature was measured via a telemetry pill that each subject swallowed ∼90 min before each experimental trial (HQ Inc., Palmetto, FL). The timing of ingestion was chosen to ensure that the temperature pill stayed within the gastrointestinal tract throughout the entire duration of each experimental trial (∼10-h period), which could not be guaranteed if subjects ingested the pill the recommended 6–8 h before data collection. Core temperature data were recorded every 10 min and are presented at preexposure and at 4 and 8 h in the present study. This approach provides a valid measure of core temperature when drinking is prohibited (22). Mean skin temperature was measured continually as the weighted average of 12 thermochron iButtons (Maxim Integrated, San Jose, CA) with the following equation: (0.07 · forehead) + (0.14 · forearm) + (0.5 · dorsal hand) + (0.07 · lower leg) + [0.13 · (shin + calf)/2] + [0.19 · (hamstring + anterior thigh)/2] + [0.35 · (chest + abdomen + subscapular + lower back)/4] (23). Mean skin temperature is presented as 5-min averages at preexposure and at 4 and 8 h during each experimental trial.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured manually in duplicate. Mean arterial pressure was calculated as diastolic pressure plus one-third pulse pressure and is reported at preexposure and at 4 and 8 h during each trial. Heart rate was recorded continuously from a standard heart rate monitor (Polar Electro, Bethpage, NY) and is reported at preexposure and at 4 and 8 h during each trial.

Venous blood and urine samples were collected preexposure and 4 and 8 h into each trial. This sample interval was chosen because it would have been unlikely that subjects could micturate more often during exposure to these conditions without fluid replacement. Urine samples were collected by subjects completely voiding their bladder into a collection urinal. There were a few instances where subjects were unable to provide a urine sample at the 4 and 8 h time points because of the prolonged dehydration without fluid replacement. Therefore, the numbers of samples (i.e., n) for all parameters from urine samples are reported for each trial and time point (31°C trial: preexposure n = 15; hour 4 n = 15; hour 8 n = 14; 34°C trial: preexposure n = 15; hour 4 n = 14; hour 8 n = 13), unless otherwise reported. Urine specific gravity was measured in duplicate with a refractometer (ATAGO Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Hemoglobin was measured in duplicate with the Hemopoint H2 (Alere, Orlando, FL), and hematocrit was measured in triplicate by microcentrifugation. Plasma and urine osmolality were measured in duplicate via freezing-point depression (model 3250; Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA). Serum and urine electrolytes (i.e., sodium and potassium) were measured in duplicate with an electrolyte analyzer (EasyLyte Plus; Medica Corporation, Bedford, MA). All sample analyses and assays were completed by a single trained technician (T.B.B.), except for interleukin-17a, which was completed by J.C.M. In all instances, sample dilutions were customized for each subject and each assay kit to ensure that all concentrations were within the accuracy ranges of the assay kits. Serum creatinine [Creatinine Serum Detection Kit; Eagle Bioscience, Inc., Nashua, NH; intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV): 1.7 (2.6)%; interassay CV: 3.1 (1.9)%] and urine creatinine [Creatinine Parameter Assay Kit; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN; intra-assay CV: 1.0 (0.6)%; interassay CV: 0.6 (0.2)%] and serum uric acid [Uric Acid Assay Kit; Eton Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA; intra-assay CV: 0.7 (0.6)%; interassay CV: 2.0 (0.3)%] and urine uric acid [Uric Acid Assay Kit; Eton Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA; intra-assay CV: 0.6 (0.4)%; interassay CV: 3.5 (0.7)%] were measured with standard colorimetric assays.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) was measured in the urine with a commercially available human NGAL ELISA kit [RayBiotech Life, Peachtree Corners, GA; intra-assay CV: 3.2 (2.8)%; interassay CV: 9.4 (3.6)%]. NGAL was measured in the urine to allow for comparison of the magnitude of general renal tubular injury across trials (6, 14, 24). Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) was measured in the urine with human KIM-1 ELISA kits [RayBiotech Life, Peachtree Corners, GA; intra-assay CV: 4.1 (6.7)%; interassay CV: 4.7 (2.2)%]. KIM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is upregulated in the proximal tubule cells during kidney injury (6, 25, 26). Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2) were measured in the urine with separate commercially available human IGFBP7 [RayBiotech Life, Peachtree Corners, GA; intra-assay CV: 5.4 (4.0)%; interassay CV: 5.7 (1.5)%] and TIMP-2 [RayBiotech Life, Peachtree Corners, GA; intra-assay CV: 0.8 (0.6)%; interassay CV: 2.1 (1.2)%] ELISA kits. IGFBP7 and TIMP-2 are proteins that induce G1 cell cycle arrest in renal epithelial cells during kidney injury (6, 14, 15). IGFBP7 is preferentially secreted in the renal proximal tubules and TIMP-2 in the distal tubules after damage to the glomeruli and/or renal tubules (6, 27, 28). The product of urinary IGFBP7 and TIMP-2 ([IGFBP7 · TIMP-2]) was the primary dependent variable. [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] has a US Food and Drug Administration-approved indication for assessing kidney injury risk in clinical practice (6, 15). Collectively, the employed kidney injury biomarker panel was selected on the basis of previous work from our laboratory (6, 11, 12, 14), and its aggregate findings allow for the examination of both general kidney injury risk (e.g., [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2]) and the potential anatomical location of kidney injury (e.g., distal vs. proximal tubules) (6, 14).

To examine the potential etiology underlying kidney injury risk (6), both inflammatory and oxidative stress markers were measured from serum, plasma, and/or urine samples. Interleukin-17 (IL-17a) was measured in the plasma with a S-PLEX Human IL-17a Kit [K151C3S-Series; Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD; intra-assay CV: 8.8 (6.4)%]. Because of sample and resource limitations, IL-17a was measured at preexposure and 8 h in plasma samples from 10 subjects who were randomly selected. Plasma IL-17a is a proinflammatory cytokine expressed after ischemic kidney injury in both rodent models and critically ill patients diagnosed with acute kidney injury (29, 30), which promotes tissue damage in part by neutrophil activation (31). Interleukin-18 (IL-18) was also measured in the urine with human IL-18 kits [Abcam, Cambridge, MA; intra-assay CV: 2.6 (2.9)%; interassay CV: 5.8 (1.7)%]. IL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine that increases with ischemic or nephrotoxic kidney injury that occurs after tubular injury (32, 33). Liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) was measured in the urine with human L-FABP ELISA kits [Abcam, Cambridge, MA; intra-assay CV: 0.9 (0.5)%; interassay CV: 1.9 (0.1)%]. L-FABP is prophylactically expressed in the proximal tubules to protect against oxidative stress in the presence of hypoxia (34–37). Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) was measured with human TBARS Assay Kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) in the serum [intra-assay CV: 1.8 (2.9)%; interassay CV: 16.2 (14.5)%] and urine [intra-assay CV: 4.2 (6.3)%; interassay CV: 7.5 (3.5)%]. TBARS is a nonspecific marker of lipid peroxidation following oxidation of polyunsaturated lipids by free radicals, which can cause renal tissue damage (38). Note that the number of subjects and samples for each trial and time point for urinary TBARS differed from other urinary markers because of inadequate remaining sample volume before commencing the assay (preexposure: 31°C n = 13, 34°C: n = 14; 4 h: 31°C n = 14, 34°C n = 14; and 8 h: 31°C n = 13, 34°C n = 12). Finally, thioredoxin-1 (TRX-1) was measured with human TRX-1 Assay kits (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in the serum [intra-assay CV: 9.8 (11.4)%; interassay CV: 11.9 (11.4)%] and urine [intra-assay CV: 8.1 (8.2)%; interassay CV: 5.5 (3.2)%]. Serum TRX-1 is an effective marker for detecting conditions of excessive oxidative stress (e.g., heart failure) (39), whereas urine TRX-1 is specifically elevated in kidney injury mediated by oxidative stress and/or hypoxia, primarily from proximal tubular epithelial cells, and positively correlates with the severity of tubular injury (40). Note that the n for each trial and time point for urinary TRX-1 differed from other urinary markers because of inadequate remaining sample volume before commencing the assay (preexposure: 31°C n = 13, 34°C n = 14; 4 h: 31°C n = 14, 34°C n = 14; and 8 h: 31°C n = 13, 34°C n = 12).

Data and Statistical Analysis

Percent changes in body mass were calculated as the difference between postexposure and preexposure nude body mass divided by preexposure body mass multiplied by 100. Percent changes in plasma volume were estimated with standard equations by Dill and Costill (41). Urine flow rates were calculated over a 1-h period (i.e., preexposure baseline urine flow rate described above) and over 4-h periods from preexposure to hour 4 and 4 to 8 h during each trial. The precisely timed urine flow rates allow for the accurate calculation of substrate clearance, excretion, and normalization of urinary kidney injury biomarkers. Creatinine clearance was calculated as the quotient of urine and serum creatinine concentration multiplied by urine flow rate. The fractional excretions of sodium and potassium were calculated from concentrations of sodium and potassium in the plasma and urine and from the change in serum and urine creatinine concentrations (6). Osmolar clearance was calculated as the quotient of osmolality of the urine and plasma multiplied by urine flow rate. Free water clearance was calculated as the difference between urine flow rate and osmolar clearance (42). All urinary kidney injury makers (NGAL, IGFBP7, TIMP-2, KIM-1, IL-18, L-FABP, TBARS, and TRX-1) were normalized to urine flow rate as has been proposed previously (6). Urinary kidney injury markers were also normalized to urine concentration (i.e., osmolality and creatinine) (6, 11, 12, 14) and are presented in Supplemental Table S1 (available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6456210), but the conclusions drawn were not affected by normalization method.

Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as individual values, absolute mean (SD), and/or as a mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval. Two-tailed t tests were used to analyze the differences in environmental conditions (i.e., dry bulb temperature, relative humidity, wet bulb temperature, and water vapor pressure) between 31°C and 34°C. Thermoregulatory, hemodynamic, hydration, kidney function, and kidney injury variables were analyzed with a repeated-measures mixed-effects model (trial × time). Notably, the mixed-effects model can accommodate any missing values. After visual inspection of predicted and actual residuals (i.e., QQ plots), it was identified that the urinary kidney injury markers were not normally distributed. Therefore, all statistical inference of urinary kidney injury makers was done after log transformation before statistical analyses, which normally distributed the data. Urinary kidney injury markers are presented numerically and graphically as raw values, but the statistical analyses reflect the log transformed data. When applicable, the Geisser–Greenhouse correction was applied if sphericity could not be assumed. Pearson correlations were used to examine relations between the change in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] from preexposure to 8 h and changes in urinary and circulating markers of oxidative stress and inflammation over this same time period in both trials. If a significant interaction or main effect was found (43), post hoc analyses were completed with Šídák’s multiple comparisons tests. All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 8; La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was set a priori at P ≤ 0.05, and actual P values are reported where possible.

RESULTS

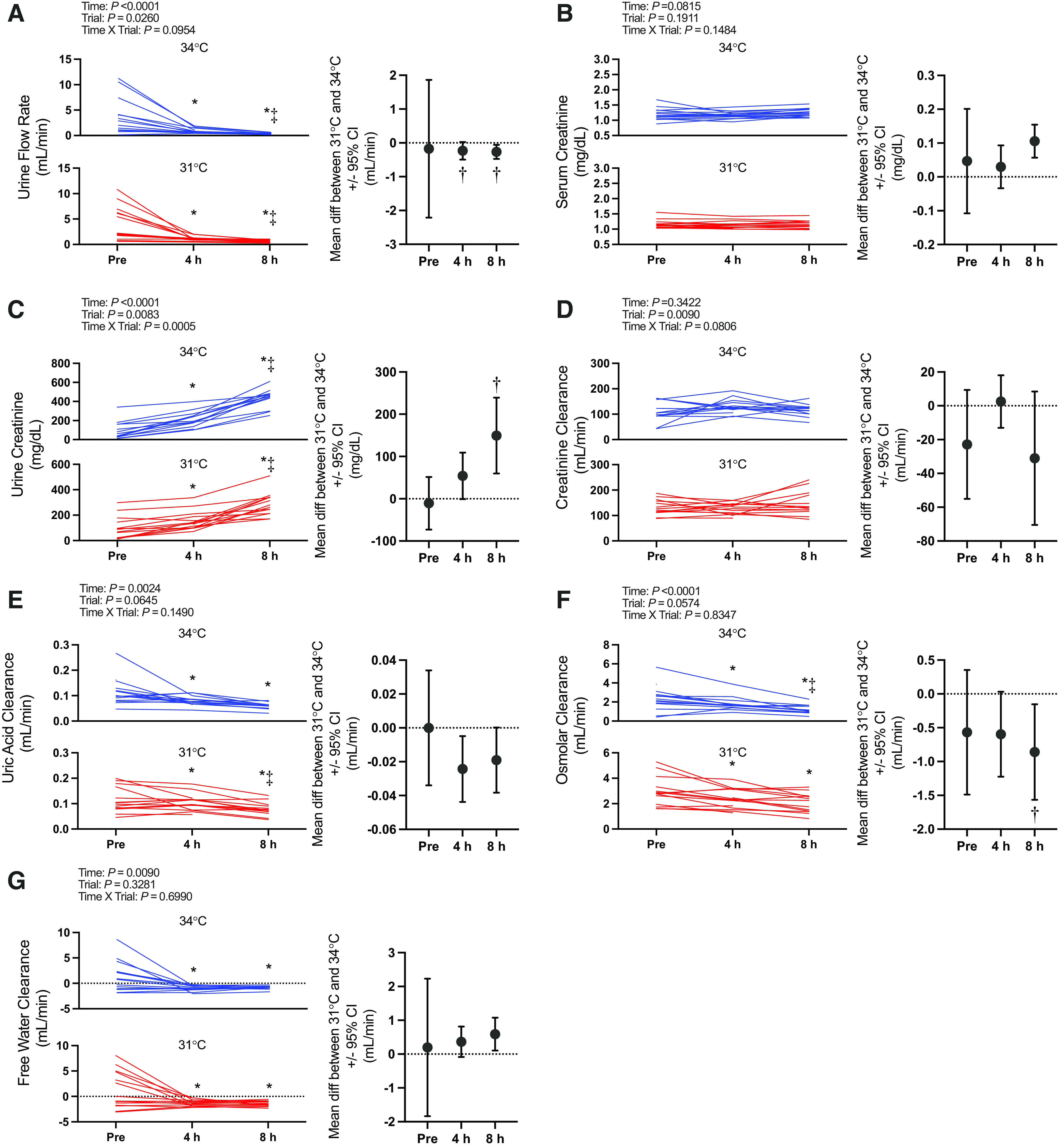

Core temperature, mean skin temperature, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure data are presented in Table 2. Briefly, core temperature increased in both the 31°C and 34°C trials (P < 0.0001) but to a greater extent in the 34°C trial at both 4 h [+1.1 (0.4)°C vs. +0.5 (0.3)°C; P < 0.0001] and 8 h [+1.4 (0.4)°C vs. +0.6 (0.3)°C; P < 0.0001]. All hydration data are presented in Table 3. Briefly, both trials elicited moderate dehydration, which is reflected by body mass loss in both trials (P < 0.001) but to a greater extent after 8 h in the 34°C trial compared with the 31°C trial [−1.9 (0.5)% vs. −1.4 (0.4)%; P = 0.002). All kidney function data are presented in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 (i.e., clearance and excretion, respectively).

Table 2.

Thermoregulation and hemodynamics

| Parameter | 31°C |

34°C |

Mixed-Effects Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pren = 15 | 4 hn = 15 | 8 hn = 15 | Pren = 15 | 4 hn = 15 | 8 hn = 15 | Time | Trial | Time × trial | |

| Core temperature, °C | 36.9 (0.3) | 37.4 (0.3)* | 37.5 (0.2)* | 36.9 (0.3) | 38.0 (0.3)*† | 38.2 (0.4)*‡† | <0.0001 | 0.0010 | <0.0001 |

| Mean skin temperature, °C | 32.8 (0.6) | 34.9 (0.4)* | 34.6 (0.7)* | 32.6 (0.6) | 36.1 (0.8)*† | 35.7 (1.0)*† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 92 (7) | 88 (8)* | 87 (7)* | 89 (5) | 85 (9)* | 82 (9)*† | 0.0023 | 0.0035 | 0.6351 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70 (7) | 74 (11) | 77 (9)* | 68 (10) | 97 (21)*† | 111 (20)*‡† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Values are presented as mean (SD). Thermoregulatory and hemodynamic data were measured every 60 min but are reported at preexposure (Pre) and 4 h and 8 h into each exposure. Data were analyzed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial), and exact P values are reported. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc analyses were completed with Šídák’s multiple comparisons tests. *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05); †different from 31°C (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Hydration markers

| Parameter | 31°C |

34°C |

Mixed-Effects Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 4 h | 8 h | Pre | 4 h | 8 h | Time effect | Condition effect | Interaction | |

| ΔBody mass, % | 0.0 (0.0) | −0.6 (0.3)* | −1.4 (0.4)*† | 0.0 (0.0) | −0.8 (0.6)* | −1.9 (0.5)*‡† | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.008 |

| Blood samples | |||||||||

| Subjects, n | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |||

| ΔPlasma volume, % | 0.0 (0.0) | −3 (7) | −4 (6) | 0.0 (0.0) | −9 (8)* | −9 (5)* | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Plasma osmolality, mosmol/kgH2O | 285 (4) | 283 (2) | 284 (2) | 284 (4) | 284 (3) | 285 (3) | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.23 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 142 (3) | 143 (2)* | 145 (2)* | 143 (2) | 144 (3) | 145 (2)*‡ | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.49 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 4.1 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.3) | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.91 |

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | 5.6 (2.2) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.9 (0.7) | 4.8 (0.9) | 5.0 (0.9) | 4.8 (0.8) | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Urine samples | |||||||||

| Subjects, n | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 13 | |||

| Urine specific gravity | 1.010 (0.007) | 1.016 (0.006) | 1.023 (0.004)*‡ | 1.009 (0.006) | 1.016 (0.007)* | 1.032 (0.018)*‡ | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Urine osmolality, mosmol/kgH2O | 450 (312) | 666 (207)* | 929 (121)*‡ | 366 (315) | 666 (242)* | 959 (129)*‡ | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.11 |

| Urine sodium, mmol/L | 51 (49) | 76 (50) | 108 (60)*‡ | 39 (48) | 62 (37) | 49 (36)† | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.005 |

| Urine potassium, mmol/L | 30.9 (20.9) | 57.4 (25.1)* | 98.3 (32.1)*‡ | 21.9 (20.5) | 57.8 (30.2)* | 120.1 (39.5)*‡ | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| Urine uric acid, mg/dL | 3.8 (3.3) | 1.1 (0.4)* | 0.6 (0.3)* | 3.7 (3.5) | 0.8 (0.5)* | 0.3 (0.2)*‡ | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.28 |

Values are presented as mean (SD). Hydration markers were measured from blood and urine samples collected at preexposure (Pre) and 4 h and 8 h into each exposure. Data were analyzed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial), and exact P values are reported. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc analyses were completed with Šídák’s multiple comparisons tests. *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05); †different from 31°C (P < 0.05).

Figure. 1.

Markers of kidney function: urine flow rate (A), serum (B) and urine (C) creatinine, and creatinine (D), uric acid (E), osmolar (F), and free water (G) clearance. Left: variables are presented as individual values for the 34°C trial (blue lines) and the 31°C trial (red lines). Values are presented at preexposure (Pre; 31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 15), 4 h (31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 14), and 8 h (31°C: n = 14, 34 °C: n = 13). y-Axes for each trial are different to enhance clarity. All statistical analyses were completed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial). The linear mixed model table is shown. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc multiple comparisons were completed with Šídák’s tests. Right: the mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval (CI). *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05); †different from 31°C (P < 0.05).

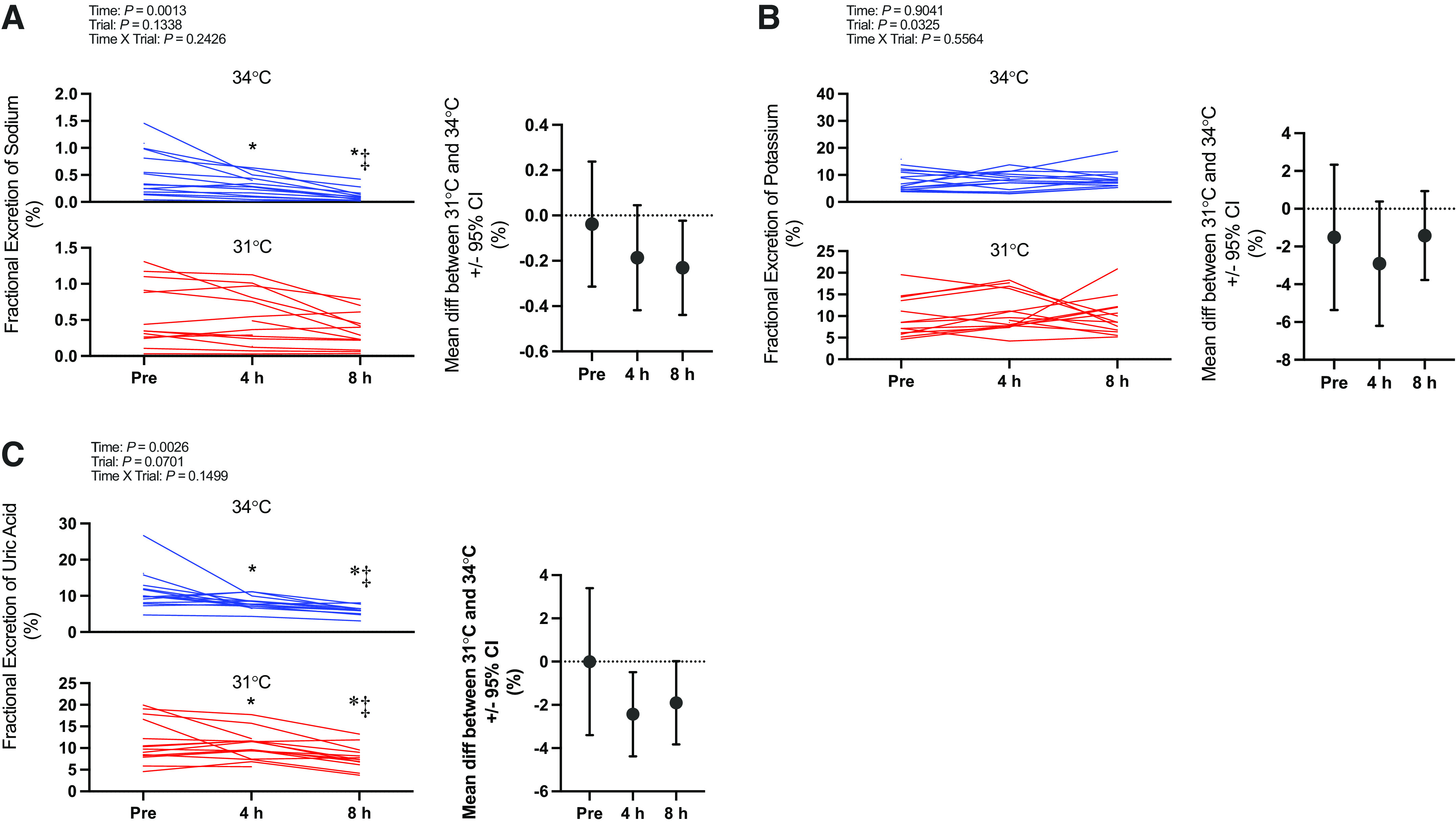

Figure. 2.

Markers of kidney function: fractional excretion of sodium (A), potassium (B), and uric acid (C). Left: variables are presented as individual values for the 34°C trial (blue lines) and the 31°C trial (red lines). Values are presented at preexposure (Pre; 31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 15), 4 h (31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 14), and 8 h (31°C: n = 14, 34°C: n = 13). y-Axes for each trial are different to enhance clarity. All statistical analyses were completed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial). The linear mixed model table is shown. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc multiple comparisons were completed with Šídák’s tests. Right: the mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval (CI). *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05).

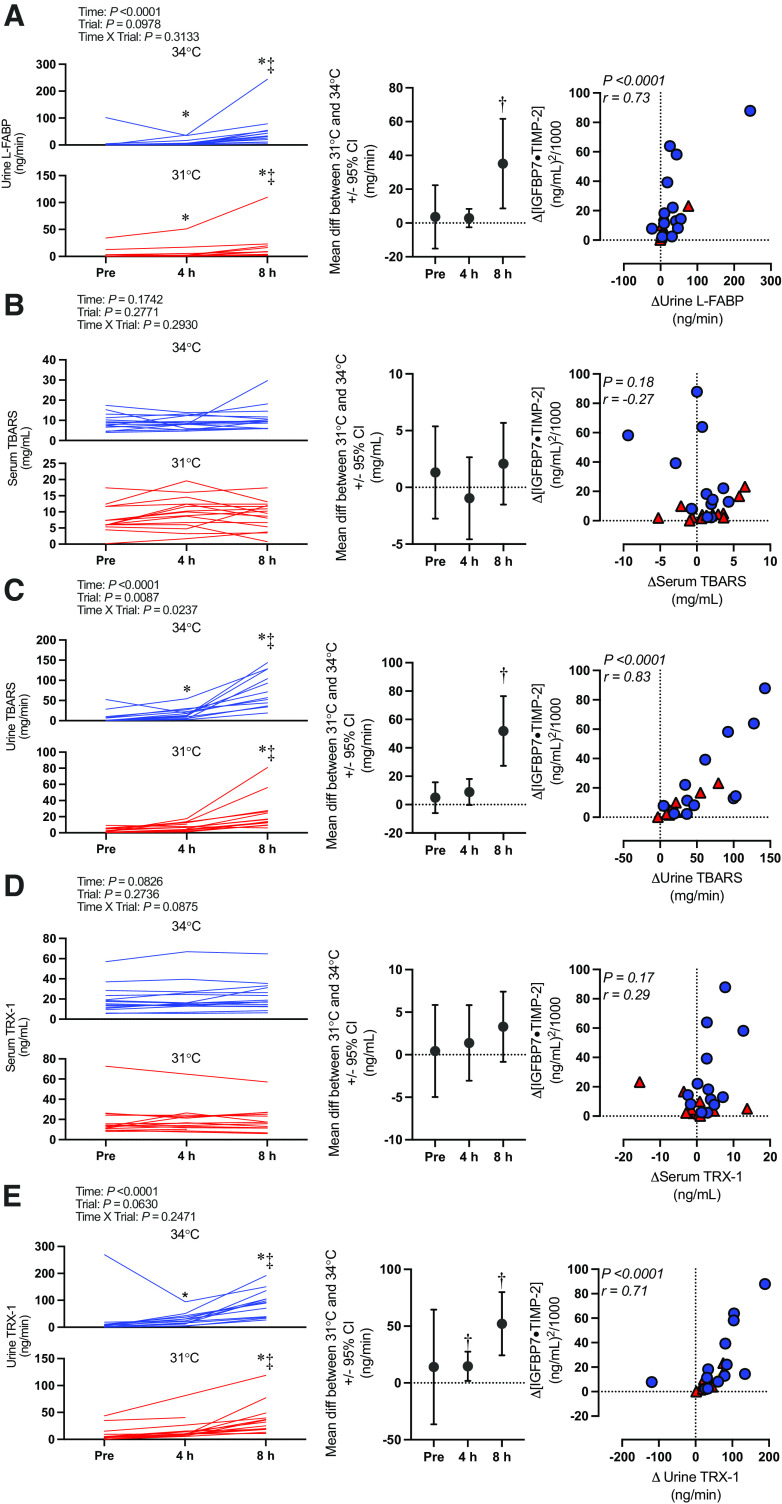

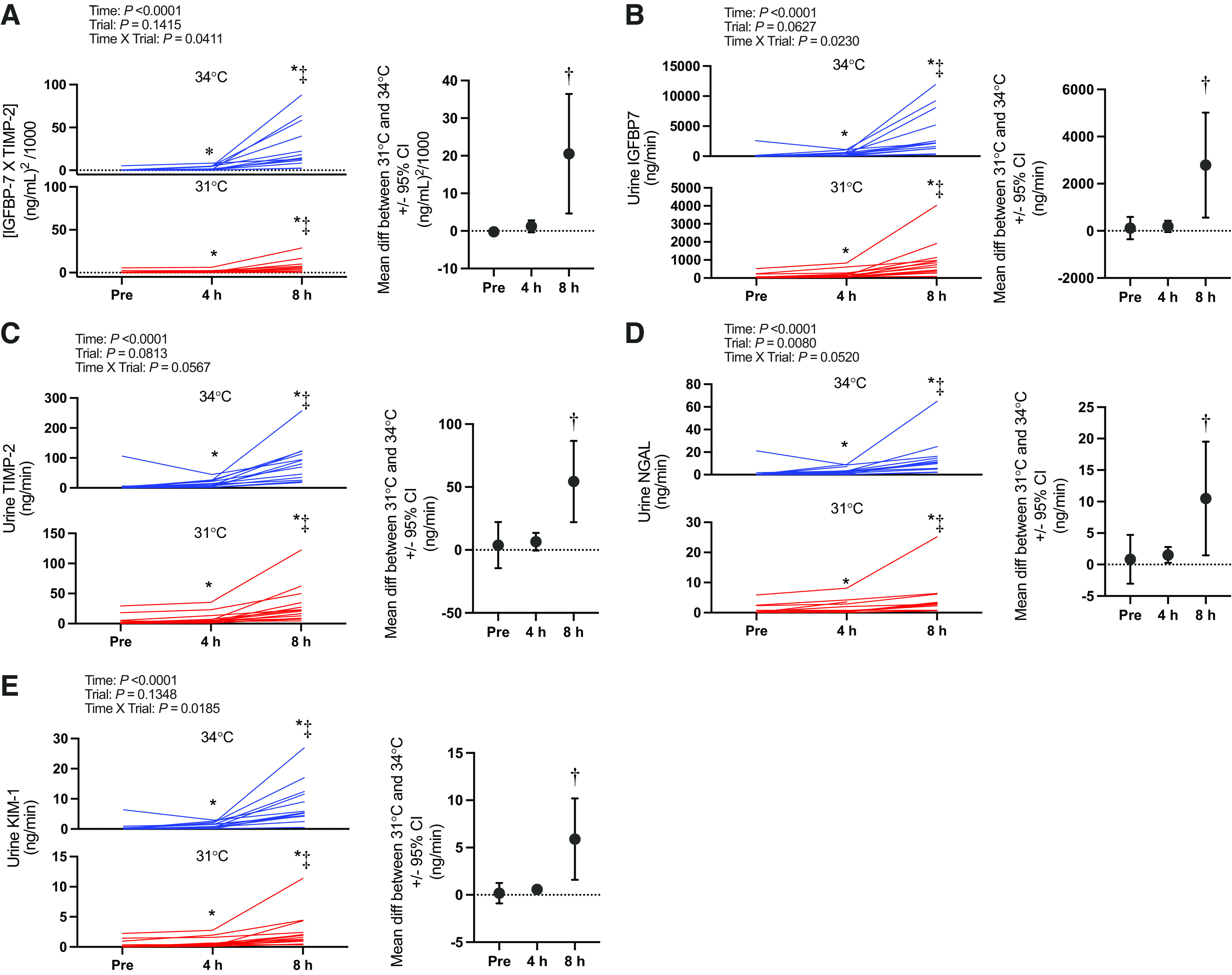

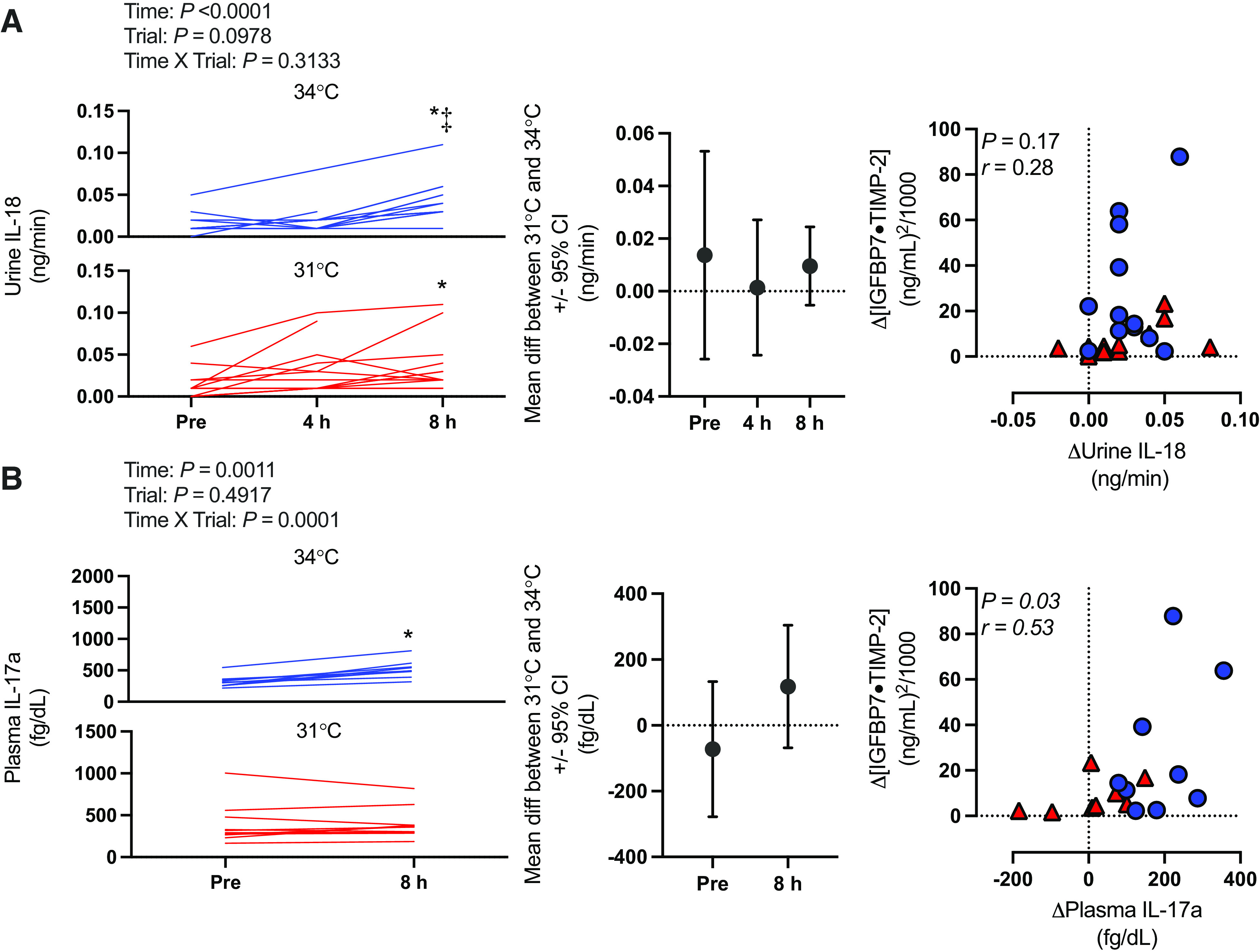

Kidney injury marker data (i.e., [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2], IGFBP7, TIMP-2, NGAL, and KIM-1) are presented in Fig. 3. Briefly, there was an interaction effect (time × trial) for [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] (P = 0.0411). [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] increased over time in both the 34°C and 31°C trials (P ≤ 0.0001). However, this increase was markedly greater at 8 h in the 34°C [+26.9 (27.1) (ng/mL)2/1,000] compared with the 31°C [+6.2 (6.5) (ng/mL)2/1,000] trial (P = 0.0024). Etiological mechanisms of kidney injury are presented in Fig. 4 (i.e., oxidative stress markers urine L-FABP, TBARS, TRX-1, and serum TBARS and TRX-1) and Fig. 5 (i.e., inflammatory markers urine IL-18 and plasma IL-17a).

Figure. 3.

Kidney injury biomarker panel: [insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) · tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2)] (A) and urine IGFBP7 (B), TIMP-2 (C), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL, D), and kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1, E). Left: urinary biomarkers normalized to urine flow rate presented as individual values for the 34°C trial (blue lines) and the 31°C trial (red lines). Values are presented at preexposure (Pre; 31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 15), 4 h (31°C: n = 15, 34°C: n = 14), and 8 h (31°C: n = 14, 34 °C: n = 13). y-Axes for each trial are different to enhance clarity. All statistical inference was completed after data were log transformed and analyzed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial). The linear mixed model table is shown. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc multiple comparisons were completed with Šídák’s tests. Right: the mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval (CI). *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05); †different from 31°C (P < 0.05).

Figure. 4.

Etiological mechanisms of kidney injury: biomarkers of oxidative stress. Left: absolute serum and urinary biomarkers normalized to urine flow rate presented as individual values for the 34°C trial (blue lines) and the 31°C trial (red lines). Values are presented at preexposure (Pre), 4 h, and 8 h. n for each variable and time point is reported within the text. y-Axes for each trial are different to enhance clarity. All statistical inference was completed after data were log transformed and analyzed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial). The linear mixed model table is shown. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc multiple comparisons were completed with Šídák’s tests. Center: the mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval (CI). Right: correlation between the change in biomarkers of oxidative stress and change in kidney injury risk (i.e., [insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) · tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2)]). Data were analyzed (Pearson r) with both 34°C (blue circles) and 31°C (red triangles) combined, and exact P value and r value are shown. L-FABP, liver-type fatty acid binding protein; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TRX-1, thioredoxin-1. *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05); †different from 31°C (P < 0.05).

Figure. 5.

Etiological mechanisms of kidney injury: inflammatory markers. Left: absolute plasma and urinary biomarkers normalized to urine flow rate presented as individual values for the 34°C trial (blue lines) and the 31°C trial (red lines). Values are presented at preexposure (Pre), 4 h, and 8 h for urine interleukin 18 (IL-18) and at Pre and 8 h for plasma interleukin 17a (IL-17a). n for each variable and time point is reported within the text. y-Axes for each trial are different to enhance clarity. All statistical inference was completed after data were log transformed and analyzed with a repeated-measures linear mixed model (time × trial). The linear mixed model table is shown. If a significant interaction or main effect was found, post hoc multiple comparisons were completed with Šídák’s tests. Center: the mean difference between 31°C and 34°C ± 95% confidence interval (CI). Right: correlation between the change in biomarkers of inflammation and change kidney injury risk (i.e., [insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) · tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2)]). Data were analyzed (Pearson r) with both 34°C (blue circles) and 31°C (red triangles) combined, and exact P value and r value are shown. *Different from Pre (P < 0.05); ‡different from 4 h (P < 0.05).

Finally, absolute and normalized (i.e., to osmolality and creatinine) values of all kidney injury markers are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

DISCUSSION

In support of our hypothesis, we observed an increase in kidney injury risk (i.e., [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2]) after 8 h of exposure in both the 31°C and 34°C trials (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the risk of kidney injury was exacerbated at 8 h in the 34°C compared with the 31°C trial. Core temperature and body mass loss were greater after 4 h in the 34°C trial (Tables 2 and 3, respectively), which likely mediated the greater risk of kidney injury observed in the 34°C trial. The increased kidney injury risk was observed to be anatomically located in both the proximal and distal tubules, as evidenced by independent increases in urinary IGFBP7 (Fig. 3B) and TIMP-2 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the etiology of this kidney injury risk is likely primarily caused by the development of oxidative stress localized to the kidneys, as demonstrated by increases in urinary L-FABP, TBARS, and TRX-1 in the absence of differential changes in serum TBARS and TRX-1 (Fig. 4).

Risk of Kidney Injury

The primary findings from the present study corroborate our previous work examining the risk of kidney injury following physical work in the heat (12). We previously demonstrated that the highest risk of kidney injury is observed with a combination of hyperthermia and dehydration following 2 h of physical work in the heat (12). Interestingly, we report similar findings between the two studies despite markedly different experimental protocols (i.e., duration, Twet, and exercise vs. rest) but similar magnitudes of hyperthermia (i.e., ∼2°C increase in core temperature) and dehydration (i.e., ∼2% body mass loss) (12). This supports that this risk of kidney injury during heat stress is a function of both the magnitude of hyperthermia and dehydration and likely the duration of exposure. To this latter point, the magnitude of the increase in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] in the present study [average peak increase: ∼27 (ng/mL)2/1,000] was higher than that of our previous work [average peak increase: ∼10 (ng/mL)2/1,000] (12). Moreover, this difference in the overall risk of kidney injury was mediated by an elevation of both IGFBP7 and TIMP-2 in the present study, whereas TIMP-2 was not elevated in our previous study despite increases in IGFBP7 (12). To our knowledge, this is the first laboratory-controlled observation in humans that heat stress exposure can increase kidney injury risk in both the proximal and distal tubules (28). Notably, the lower magnitude of hyperthermia and dehydration in the 31°C trial did not completely ameliorate the risk of kidney injury. Rather, we still observed in a rise in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] over the 8-h exposure. These findings corroborate epidemiological data indicating that the risk of kidney injury is elevated during extreme heat events (1, 44) and indicate that the heat stress does not need to be uncompensable to increase the risk of kidney injury during an extreme heat event.

The increased risk of kidney injury during heat exposure has been speculated to be caused by a reduction in kidney blood flow (45–47). During passive heat stress, there is a redistribution of blood flow away from the kidneys to maintain blood pressure under conditions where skin blood flow is markedly increased (6), which is primarily mediated by increases in sympathetic nervous system activation. Furthermore, evidence from animal models indicates that reductions in renal blood flow during heat stress are predominantly occurring in cortical regions, causing localized ischemia (48, 49). The reduced oxygen delivery is exacerbated by efforts to promote fluid conservation during hyperthermia and dehydration, as sodium reabsorption is an ATP-dependent process, resulting in the depletion of ATP in the renal cortex (18, 50–52). This low-ATP environment is believed to increase the susceptibility of the renal tubules to injury, which likely occurs after increased oxidative stress and inflammation (16, 17). Under such conditions, L-FABP is prophylactically expressed in the tubules to protect against oxidative stress occurring subsequent to hypoxemia (6, 14). Therefore, we interpret that the rise in L-FABP observed during prolonged heat stress, which is strongly correlated with the rise in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] (Fig. 4A), indicates that the observed kidney injury is mediated by the development of oxidative stress in the renal tubules. This is further supported by our observations that urinary TBARS, a nonspecific marker of lipid peroxidation following oxidation of polyunsaturated lipids by free radicals (38), and urinary TRX-1, a redox-regulating protein that is secreted to the extracellular space in response to oxidative stress (39, 40), were elevated in both trials but to a greater extent in the 34°C trial at 8 h (Fig. 4, C and E). Notably, increases in both urinary TBARS and urinary TRX-1 were strongly correlated with increases in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] (Fig. 4, C and E). Moreover, serum TBARS and serum TRX-1 did not change over time in either trial or differ between trials (Fig. 4, B and D), and there were no relations between the increase in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] and increases in the circulating oxidative stress markers (Fig. 4, B and D), suggesting that the increased oxidative stress was localized to the kidneys. Together, these findings support that kidney injury risk in the context of extreme prolonged heat stress is contributed to by oxidative stress.

It is particularly interesting that we did not observe parallel rises in urinary IL-18 that would support a role of activation of inflammatory pathways (6, 14). That said, clinical data indicate that urinary IL-18 does not increase after ischemic or nephrotoxic kidney injury until ∼6 h after tubular injury (32, 33). Thus, it may be that we did not observe a rise in urinary IL-18 during the 8-h heat exposure because of the timing of urine sample collection (see Considerations). This speculation is supported by our observation of elevations in plasma IL-17a, which was elevated at 8 h in the 34°C trial but not in the 31°C trial (Fig. 5B). Plasma IL-17a is a proinflammatory cytokine expressed after ischemic kidney injury (29, 30), which promotes tissue damage in part by neutrophil activation (31). More importantly, expression of plasma IL-17a is elevated in patients with acute kidney injury and potentially modulates the progression from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease (30). It is important to note that we did not observe differential plasma IL-17a values between trials. However, it is possible that we may have been underpowered to observe this pairwise difference because of the comparatively low number of subjects for this analysis (n = 10). This possibility is highlighted by post hoc analyses demonstrating a greater rise in plasma IL-17a in the 34°C trial [+199 (90) fg/dL] versus the 31°C trial [+9 (96) fg/dL; P = 0.0002] when the data obtained at 8 h are presented as a change from preexposure. Moreover, we also observed a modest correlation between the increase in plasma IL-17a and the change in [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2] (Fig. 5B). Therefore, it is likely that inflammatory pathway activation contributes to the increased kidney injury caused by prolonged extreme heat exposure. However, more robust evidence is required.

Uric acid has been identified as a potential modulator of kidney injury risk during heat stress (6). That is, elevations in uric acid (i.e., hyperuricemia), a prooxidant, increase kidney injury risk. Notably, hyperuricemia has been shown to occur during exercise heat stress in laboratory studies (11, 12) and in outdoor laborers (53), both situations that elevate the risk of kidney injury. In the kidneys, elevations in endogenous uric acid production increase the demand for intracellular ATP in the renal proximal tubules (54) and can independently decrease kidney blood flow (55) and have been suggested to augment the pathophysiological processes described above (6, 14). Serum uric acid (Table 3) did not change in the present study, which is contrary to our previous work (12). However, urine uric acid, excretion, and clearance were not measured in our previous work, so we could not previously make any inference about renal handling of uric acid. Thus, the present study uniquely demonstrates that uric acid clearance and the fractional excretion of uric acid (Fig. 2C) declined during each trial. Such observations indicate that there was likely not endogenous production of uric acid in the kidneys, which could occur as the result of fructokinase activity secondary to endogenous production of fructose (via the polyol-fructokinase pathway) (50) or through consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages (6, 11, 14, 56). Indeed, a role for the polyol-fructokinase pathway in the elevation in kidney injury risk in the present study is unlikely because this pathway is activated by plasma hyperosmolality but no changes in plasma osmolality were observed here.

Kidney Function

The present study did not likely elicit kidney injury per se. Rather, the observed increases in urinary biomarkers are interpreted to examine the risk of kidney injury, which have no clinical threshold for diagnosing injury in the context of our study (57). According to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Guidelines (KDIGO) (58), acute kidney injury is clinically diagnosed when serum creatinine increases by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 h and/or urine flow rate is reduced to ≤0.5 mL·min−1 for 6 or more hours. In the present study, there was no change over time in serum creatinine in either trial, although serum creatinine was greater in the 34°C trial compared with the 31°C trial at 8 h (Fig. 1B). That stated, one subject during the 34°C trial had a 0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine meeting the KDIGO criteria. Urine flow rate declined throughout each trial but was not different between trials. Moreover, average urine flow rate did not decline under 0.5 mL·min−1 until 8 h in the 34°C trial, but is it unknown whether this reduction was sustained for 6 or more hours. Collectively, therefore, there was little evidence to support a potential clinical diagnosis of kidney injury based on changes in kidney function, even despite profound increases in urinary [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2].

Interestingly, creatinine clearance did not change throughout each trial. A recent review found that the impact of passive heat stress on glomerular filtration rate is inconsistent in the literature, with some studies showing reductions and others a maintenance (6). The maintenance of creatinine clearance in the present study may highlight the role of the glomerular filtration rate reserve, which describes the ability of the kidneys to recruit additional nephrons to increase the filtration capacity, because not all nephrons are active when the kidneys are unstressed (59). Thus, if glomerular filtration rate were to be challenged during a stressor, such as the prolonged heat exposure, the glomerular filtration rate reserve would provide a mechanism by which the kidneys are able to maintain filtration capacity (6). However, this remains speculative, as the impact of heat stress and/or dehydration on glomerular filtration rate reserve has never been explored. Nevertheless, this is the first study to document an increased risk of kidney injury in the absence of consistent reductions in kidney function (i.e., reductions in glomerular filtration rate and/or elevations in serum creatinine). This is important because it provides evidence that the stability of kidney function should not always be interpreted as benign during heat stress and likely casts doubt on the validity of conclusions drawn from studies that have interpreted reductions in kidney function during and after heat stress as a marker of kidney injury.

Considerations

There are a number of experimental considerations that warrant mentioning. The experimental considerations mostly stem from the fact that this experiment was not designed a priori to assess kidney injury risk. Rather, the study was primarily designed to assess the thermoregulatory and hydration responses to prolonged exposure to warm and very humid environments in healthy young men (10). First, we do not have a time control trial (e.g., 8 h resting in a temperate environment) that would permit examination of the role of fluid restriction in the absence of heat stress. Second, in contrast to previous work from our laboratory (12), we did not collect blood and urine samples after a recovery period after subjects had been removed from heat stress. This is worth highlighting because Chapman et al. (12) observed peak urinary kidney injury biomarker responses (e.g., NGAL, IGFBP7) ∼90 min after exercise heat stress. Therefore, it is possible that peak increases in urinary biomarkers were missed in the present study (11–13). Moreover, the timing of sample collection to elucidate the relative risk of kidney injury is likely important particularly in occupational and clinical settings (6, 14, 60). We also did not collect blood and urine samples before 4 h of exposure, so we are unable to elucidate the onset or required duration of exposure to elicit kidney injury risk for exposures under 4 h. Third, despite high external validity regarding the Twet conditions, drinking and cool-seeking behavior were not permitted. Thus, the present study does not represent an entirely realistic situation during an extreme heat event unless there was a collapse in infrastructure (i.e., power outages, inaccessible potable water). Therefore, our primary findings represent a worst-case scenario by which to inform public health recommendations during extreme heat events. Finally, because of the nature of the original investigation (i.e., with specificity to the US Navy), our findings are limited to young, healthy men. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether this increased risk of kidney injury is modified or exacerbated by sex, age, and/or chronic disease (e.g., obesity, hypertension, diabetes, etc.).

Perspectives

To our knowledge, we are the first to experimentally examine the risk of kidney injury during an extreme heat event scenario that parallels the Twet experienced during current and projected extreme heat events. There is urgency and importance in our findings because kidney injury is a leading cause of excess hospital admissions during extreme heat events (1, 44, 61), especially in vulnerable populations (e.g., older adults) (5, 62). Current public health recommendations encourage at-risk populations to seek cooling and drink cool water to reduce the likelihood of hyperthermia and dehydration. Indeed, mitigating hyperthermia and dehydration likely reduces the risk of kidney injury, as highlighted in our 31°C trial. However, a rise in the overall kidney injury risk (i.e., [IGFBP7 · TIMP-2]) persisted in the 31°C trial. This potentially highlights the role of exposure duration in kidney injury risk, which is an important consideration during heat waves [i.e., periods of unusually hot weather lasting 2 or more days (63)], and may help inform countermeasures to minimize exposure duration (e.g., cooling centers). In this regard, it must be noted that although the conditions utilized here were extreme, there are many populations throughout the globe, including the United States, that have limited resources or opportunities to seek cooling and/or access to potable water during extreme heat events (e.g., low socioeconomic status, certain rural or dense urban settings, etc.) (64). Thus, these worst-case scenario data may truly reflect real-world challenges to many of the most vulnerable populations (65–67). Finally, in relation to the present study (i.e., single heat stress exposure), it was recently reported that a single heat injury (i.e., heat stroke) can result in acute kidney injury and subsequently elevates the risk for the development of chronic kidney disease (∼4-fold) and the risk of end-stage renal disease (∼9-fold) (68). Ultimately, safeguarding at-risk populations against hyperthermia and dehydration during extreme heat events is of upmost importance in reducing the risk of kidney injury and potentially the development of chronic kidney disease.

In addition to extreme heat events, individuals who are regularly exposed to heat stress (e.g., outdoor laborers) are also at risk of kidney injury. This risk was first identified in global hot spots (e.g., agricultural workers in Central America) (69, 70) after the observed rise in chronic kidney disease of nontraditional origin (CKDnt) (i.e., in the absence of traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity), which is a growing concern in the United States (71–73). The findings from the present study likely inform the etiology of kidney injury risk in occupational heat stress settings and provide information that can be used for the assessment of kidney injury risk and development of countermeasures to mitigate the rise in core temperature (e.g., environmental exposure limits, work-to-rest ratios), stave off dehydration (e.g., rehydration schedule, fluid beverage type), or alleviate oxidative stress and/or inflammation (e.g., nutra- or pharmaceutical interventions). It is important to note, however, that caution should be made when generalizing between exercise and passive heat stress scenarios. Although there is no difference in the primary etiological hypothesis (i.e., heat stress mediated), there has been no direct comparison between passive and exercise heat stress that elicits similar magnitudes of hyperthermia and/or dehydration. There are many factors that could exacerbate kidney injury risk during exercise heat stress (i.e., muscle damage, metabolic heat production), although recent evidence has shown that only exercise in the heat increases the risk of kidney injury compared with exercise in temperate conditions (74). However, it remains unknown whether the impact of the combination of exercise and heat stress is additive or synergistic as it relates to mediating kidney injury risk.

Conclusions

The present study provides evidence that 8 h of exposure to Twet experienced during current extreme heat events (31°C) under resting conditions increases the risk of kidney injury and that the risk of kidney injury is worsened by Twet exposures expected during future extreme heat events (34°C). These data also reveal that the increased risk of kidney injury is likely of both renal proximal and distal tubule origins and is at least partially due to the development of oxidative stress and likely inflammatory activation.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6456210.

GRANTS

This work was supported by awards from Naval Sea Systems Command (N00024-18-C-4316, to D.H. and Z.J.S.), the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (R01OH011528, to Z.J.S.), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK063114, to D.P.B.; T32DK120524-01, to J.C.M.), and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR002529, to Z.J.S and D.P.B).

DISCLAIMERS

This article’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, or the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

Z. J. Schlader has received consultant fees from Otsuka Holdings Co., Ltd. No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the other authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.W.H., B.D.J., D.H., and Z.J.S. conceived and designed research; H.W.H., J.J.S., T.B.B., C.L.C., R.R.P., J.C.M., D.P.B., D.H., and Z.J.S. performed experiments; H.W.H., T.B.B., and J.C.M. analyzed the data; H.W.H., C.L.C., B.D.J., R.R.P., J.C.M, D.P.B., D.H., and Z.J.S. interpreted results of experiments; H.W.H. prepared figures; H.W.H. and Z.J.S. drafted manuscript; H.W.H., J.J.S., T.B.B., C.L.C., B.D.J., R.R.P., J.C.M, D.P.B., D.H., and Z.J.S. edited and revised manuscript; H.W.H., J.J.S., T.B.B., C.L.C., B.D.J., R.R.P., J.C.M, D.P.B., D.H., and Z.J.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the subjects for participating in our study. Additionally, we thank the Center for Research and Education in Special Environments (CRESE) research technicians and other students for assistance during data collection. We also thank Joel Greenshields for statistical assistance. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender and is published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basu R, Samet JM. Relation between elevated ambient temperature and mortality: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiol Rev 24: 190–202, 2002. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye X, Wolff R, Yu W, Vaneckova P, Pan X, Tong S. Ambient temperature and morbidity: a review of epidemiological evidence. Environ Health Perspect 120: 19–28, 2012. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffel ED, Horton RM, de Sherbinin A. Temperature and humidity based projections of a rapid rise in global heat stress exposure during the 21st century. Environ Res Lett 13: 014001, 2018. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaa00e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM.. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobb JF, Obermeyer Z, Wang Y, Dominici F. Cause-specific risk of hospital admission related to extreme heat in older adults. JAMA 312: 2659–2667, 2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman CL, Johnson BD, Parker MD, Hostler D, Pryor RR, Schlader Z. Kidney physiology and pathophysiology during heat stress and the modification by exercise, dehydration, heat acclimation and aging. Temperature (Austin) 8: 108–159, 2021. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2020.1826841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung SS, McLellan TM, Tenaglia S. The thermophysiology of uncompensable heat stress. Physiological manipulations and individual characteristics. Sports Med 29: 329–359, 2000. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200029050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny GP, Jay O. Thermometry, calorimetry, and mean body temperature during heat stress. Compr Physiol 3: 1689–1719, 2013. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouillet A, Rey G, Wagner V, Laaidi K, Empereur-Bissonnet P, Le Tertre A, Frayssinet P, Bessemoulin P, Laurent F, De Crouy-Chanel P, Jougla E, Hémon D. Has the impact of heat waves on mortality changed in France since the European heat wave of summer 2003? A study of the 2006 heat wave. Int J Epidemiol 37: 309–317, 2008. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlader ZJ, Johnson BD, Pryor RR, Stooks J, Clemency BM, Hostler D. Human thermoregulation during prolonged exposure to warm and extremely humid environments expected to occur in disabled submarine scenarios. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 318: R950–R960, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00018.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman CL, Johnson BD, Sackett JR, Parker MD, Schlader ZJ. Soft drink consumption during and following exercise in the heat elevates biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 316: R189–R198, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00351.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman CL, Johnson BD, Vargas NT, Hostler D, Parker MD, Schlader ZJ. Both hyperthermia and dehydration during physical work in the heat contribute to the risk of acute kidney injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 128: 715–728, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00787.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlader ZJ, Chapman CL, Sarker S, Russo L, Rideout TC, Parker MD, Johnson BD, Hostler D. Firefighter work duration influences the extent of acute kidney injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 49: 1745–1753, 2017. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlader ZJ, Hostler D, Parker MD, Pryor RR, Lohr JW, Johnson BD, Chapman CL. The potential for renal injury elicited by physical work in the heat. Nutrients 11: 2087, 2019. doi: 10.3390/nu11092087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endre ZH, Pickering JW. Acute kidney injury: cell cycle arrest biomarkers win race for AKI diagnosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 683–685, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans RG, Ince C, Joles JA, Smith DW, May CN, O’Connor PM, Gardiner BS. Haemodynamic influences on kidney oxygenation: clinical implications of integrative physiology. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 40: 106–122, 2013. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1503–1520, 2006. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Andres-Hernando A, Jensen T, Tolan DR, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Newman LS, Butler-Dawson J, Sorensen C, Glaser J, Miyazaki M, Diaz HF, Ishimoto T, Kosugi T, Maruyama S, Garcia GE, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Increase of core temperature affected the progression of kidney injury by repeated heat stress exposure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 317: F1111–F1121, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00259.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bain AR, Jay O. Does summer in a humid continental climate elicit an acclimatization of human thermoregulatory responses? Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 1197–1205, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1743-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS, American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 377–390, 2007. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCullough E, Jones B, Huck J. A comprehensive data base for estimating clothing insulation. ASHRAE Trans 91: 29–47, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson J, Ganio MS, Seifert T, Overgaard M, Secher NH, Crandall CG. Pulmonary artery and intestinal temperatures during heat stress and cooling. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 857–862, 2012. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823d7a2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardy JD, Du Bois EF, Soderstrom GF. The technic of measuring radiation and convection. J Nutr 15: 461–475, 1938. doi: 10.1093/jn/15.5.461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyner JL, Parikh CR. Clinical utility of biomarkers of AKI in cardiac surgery and critical illness. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1034–1042, 2013. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05150512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichimura T, Bonventre JV, Bailly V, Wei H, Hession CA, Cate RL, Sanicola M. Kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up-regulated in renal cells after injury. J Biol Chem 273: 4135–4142, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prozialeck WC, Vaidya VS, Liu J, Waalkes MP, Edwards JR, Lamar PC, Bernard AM, Dumont X, Bonventre JV. Kidney injury molecule-1 is an early biomarker of cadmium nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 72: 985–993, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson AC, Zager RA. Mechanisms underlying increased TIMP2 and IGFBP7 urinary excretion in experimental AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2157–2167, 2018. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018030265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emlet DR, Pastor-Soler N, Marciszyn A, Wen X, Gomez H, Humphries WH 4th, Morrisroe S, Volpe JK, Kellum JA. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2: differential expression and secretion in human kidney tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F284–F296, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00271.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehrotra P, Patel JB, Ivancic CM, Collett JA, Basile DP. Th-17 cell activation in response to high salt following acute kidney injury is associated with progressive fibrosis and attenuated by AT-1R antagonism. Kidney Int 88: 776–784, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehrotra P, Sturek M, Neyra JA, Basile DP. Calcium channel Orai1 promotes lymphocyte IL-17 expression and progressive kidney injury. J Clin Invest 130: 1052, 2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI135716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen JE, Sutherland TE, Rückerl D. IL-17 and neutrophils: unexpected players in the type 2 immune response. Curr Opin Immunol 34: 99–106, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu H, Craft ML, Wang P, Wyburn KR, Chen G, Ma J, Hambly B, Chadban SJ. IL-18 contributes to renal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2331–2341, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Wang Z, Edelstein CL, Devarajan P, Patel UD, Zappitelli M, Krawczeski CD, Passik CS, Swaminathan M, Garg AX, TRIBE-AKI Consortium. Postoperative biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and poor outcomes after adult cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1748–1757, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashani K, Cheungpasitporn W, Ronco C. Biomarkers of acute kidney injury: the pathway from discovery to clinical adoption. Clin Chem Lab Med 55: 1074–1089, 2017. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maatman RG, Van Kuppevelt TH, Veerkamp JH. Two types of fatty acid-binding protein in human kidney. Isolation, characterization and localization. Biochem J 273: 759–766, 1991. doi: 10.1042/bj2730759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parikh CR, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Garg AX, Kadiyala D, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Edelstein CL, Devarajan P, Patel UD, Zappitelli M, Krawczeski CD, Passik CS, Coca SG; TRIBE-AKI Consortium. Performance of kidney injury molecule-1 and liver fatty acid-binding protein and combined biomarkers of AKI after cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1079–1088, 2013. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10971012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto T, Noiri E, Ono Y, Doi K, Negishi K, Kamijo A, Kimura K, Fujita T, Kinukawa T, Taniguchi H, Nakamura K, Goto M, Shinozaki N, Ohshima S, Sugaya T. Renal L-type fatty acid–binding protein in acute ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2894–2902, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vodošek Hojs N, Bevc S, Ekart R, Hojs R. Oxidative stress markers in chronic kidney disease with emphasis on diabetic nephropathy. Antioxidants (Basel) 9: 925, 2020. doi: 10.3390/antiox9100925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kishimoto C, Shioji K, Nakamura H, Nakayama Y, Yodoi J, Sasayama S. Serum thioredoxin (TRX) levels in patients with heart failure. Jpn Circ J 65: 491–494, 2001. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasuno K, Shirakawa K, Yoshida H, Mori K, Kimura H, Takahashi N, Nobukawa Y, Shigemi K, Tanabe S, Yamada N, Koshiji T, Nogaki F, Kusano H, Ono T, Uno K, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Muso E, Iwano M. Renal redox dysregulation in AKI: application for oxidative stress marker of AKI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F1342–F1351, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00381.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol 37: 247–248, 1974. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wesson LG Jr, Anslow WP Jr.. Effect of osmotic and mercurial diuresis on simultaneous water diuresis. Am J Physiol 170: 255–269, 1952. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1952.170.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tybout A, Sternthal B, Keppel G, Verducci J, Meyers-Levy J, Barnes J, Maxwell S, Allenby G, Gupta S, Steenkamp J-B. Can I test for simple effects in the presence of an insignificant interaction? J Consum Psychol 10: 5–10, 2001. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basu R, Pearson D, Malig B, Broadwin R, Green R. The effect of high ambient temperature on emergency room visits. Epidemiology 23: 813–820, 2012. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7f97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radigan LR, Robinson S. Effects of environmental heat stress and exercise on renal blood flow and filtration rate. J Appl Physiol 2: 185–191, 1949. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1949.2.4.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCance RA, Widdowson EM. The secretion of urine in man during experimental salt deficiency. J Physiol 91: 222–231, 1937. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1937.sp003554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith JH, Robinson S, Pearcy M. Renal responses to exercise, heat and dehydration. J Appl Physiol 4: 659–665, 1952. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1952.4.8.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyamoto M. Renal cortical and medullary tissue blood flow during experimental hyperthermia in dogs. Jpn J Hyperthermic Oncol 10: 78–89, 1994. doi: 10.3191/thermalmedicine.10.78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hope A, Tyssebotn I. The effect of water deprivation on local renal blood flow and filtration in the laboratory rat. Circ Shock 11: 175–186, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roncal Jimenez CA, Ishimoto T, Lanaspa MA, Rivard CJ, Nakagawa T, Ejaz AA, Cicerchi C, Inaba S, Le M, Miyazaki M, Glaser J, Correa-Rotter R, González MA, Aragón A, Wesseling C, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ. Fructokinase activity mediates dehydration-induced renal injury. Kidney Int 86: 294–302, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doucet A. Function and control of Na-K-ATPase in single nephron segments of the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 34: 749–760, 1988. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer LG, Schnermann J. Integrated control of Na transport along the nephron. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 676–687, 2015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12391213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roncal-Jimenez C, García-Trabanino R, Barregard L, Lanaspa MA, Wesseling C, Harra T, Aragón A, Grases F, Jarquin ER, González MA, Weiss I, Glaser J, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ. Heat stress nephropathy from exercise-induced uric acid crystalluria: a perspective on Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 20–30, 2016. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao J, Zhang X, Fu C, Yang Q, Xie Y, Zhang Z, Ye Z. Impaired Na+-K+-ATPase signaling in renal proximal tubule contributes to hyperuricemia-induced renal tubular injury. Exp Mol Med 50: e452, 2018. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sánchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Santamaría J, Avila-Casado C, Soto V, Nepomuceno T, Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Johnson RJ, Herrera-Acosta J. Mild hyperuricemia induces vasoconstriction and maintains glomerular hypertension in normal and remnant kidney rats. Kidney Int 67: 237–247, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.García-Arroyo FE, Cristóbal M, Arellano-Buendía AS, Osorio H, Tapia E, Soto V, Madero M, Lanaspa MA, Roncal-Jiménez C, Bankir L, Johnson RJ, Sánchez-Lozada LG. Rehydration with soft drink-like beverages exacerbates dehydration and worsens dehydration-associated renal injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R57–R65, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00354.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Dorman NM, Christiansen SL, Hoorn EJ, Ingelfinger JR, et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int 97: 1117–1129, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 120: c179–c184, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jufar AH, Lankadeva YR, May CN, Cochrane AD, Bellomo R, Evans RG. Renal functional reserve: from physiological phenomenon to clinical biomarker and beyond. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 319: R690–R702, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00237.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chapman CL, Schlader ZJ. Assessing the risk of acute kidney injury following exercise in the heat: timing is important: Comment on: Chapman, C.L., Johnson, B.D., Vargas, N.T., Hostler, D, Parker, M.D., and Schlader, Z.J. Hyperthermia and dehydration during physical work in the heat both contribute to the risk of acute kidney injury, J Appl Physiol (1985), 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00787.2019. Temperature (Austin) 7: 304–306, 2020. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2020.1741333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim YH, So R, Lee C, Hong YC, Park M, Kim L, Yoon HJ. Ambient temperature and hospital admissions for acute kidney injury: a time-series analysis. Sci Total Environ 616-617: 1134–1617, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hopp S, Dominici F, Bobb JF. Medical diagnoses of heat wave-related hospital admissions in older adults. Prev Med 110: 81–85, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.NOAA. National Weather Service: Heat Wave. https://w1.weather.gov/glossary/index.php?letter=h. [2021].

- 64.Benz SA, Burney JA. Widespread race and class disparities in surface urban heat extremes across the United States. Earth's Future 9: e2021EF002016, 2021. doi: 10.1029/2021EF002016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chuang WC, Gober P. Predicting hospitalization for heat-related illness at the census-tract level: accuracy of a generic heat vulnerability index in Phoenix, Arizona (USA). Environ Health Perspect 123: 606–612, 2015. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, Lavigne E, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Tobias A, Tong S, Rocklöv J, Forsberg B, Leone M, De Sario M, Bell ML, Guo YL, Wu CF, Kan H, Yi SM, de Sousa Zanotti Stagliorio Coelho M, Saldiva PH, Honda Y, Kim H, Armstrong B. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 386: 369–375, 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hondula DM, Kuras ER, Betzel S, Drake L, Eneboe J, Kaml M, Munoz M, Sevig M, Singh M, Ruddell BL, Harlan SL. Novel metrics for relating personal heat exposure to social risk factors and outdoor ambient temperature. Environ Int 146: 106271, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tseng MF, Chou CL, Chung CH, Chen YK, Chien WC, Feng CH, Chu P. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with heat injury: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One 15: e0235607, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson RJ, Wesseling C, Newman LS. Chronic kidney disease of unknown cause in agricultural communities. N Engl J Med 380: 1843–1852, 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1813869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hansson E, Mansourian A, Farnaghi M, Petzold M, Jakobsson K. An ecological study of chronic kidney disease in five Mesoamerican countries: associations with crop and heat. BMC Public Health 21: 840, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10822-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chapman CL, Hess HW, Lucas RA, Glaser J, Saran R, Bragg-Gresham J, Wegman DH, Hansson E, Minson CT, Schlader ZJ. Occupational heat exposure and the risk of chronic kidney disease of non-traditional origin in the United States. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 321: R141–R151, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00103.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dahl K, Licker R. Too Hot to Work: Assessing the Threats Climate Change Poses to Outdoor Workers. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists, 2021. doi: 10.47923/2021.14236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dahl K, Licker R, Abatzoglou JT, Declet-Barreto J. Increased frequency of and population exposure to extreme heat index days in the United States during the 21st century. Environ Res Commun 1: 075002, 2019. doi: 10.1088/2515-7620/ab27cf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Z, McKenna Z, Fennel Z, Nava RC, Wells A, Ducharme J, Houck J, Morana K, Mermier C, Kuennen M, Magalhaes FC, Amorim F. The combined effects of exercise-induced muscle damage and heat stress on acute kidney stress and heat strain during subsequent endurance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 122: 1239–1248, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00421-022-04919-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6456210.