Abstract

Truncating variants in TTN (TTNtvs) are the most common known cause of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), but how TTNtvs cause disease has remained controversial. Efforts to detect truncated titin proteins in affected human DCM hearts have failed, suggesting that disease is caused by haploinsufficiency, but reduced amounts of titin protein have not yet been demonstrated. Here, we leveraged a collection of 184 explanted posttransplant DCM hearts to show, using specialized electrophoretic gels, Western blotting, allelic phasing, and unbiased proteomics, that truncated titin proteins can quantitatively be detected in human DCM hearts. The sizes of truncated proteins corresponded to that predicted by their respective TTNtvs; the truncated proteins were encoded by the TTNtv-bearing allele; and no degradation fragments from protein encoded by either allele were detectable. In parallel, full-length titin was less abundant in TTNtv+ than in TTNtv− DCM hearts. Disease severity or need for transplantation did not correlate with TTNtv location. Transcriptomic profiling revealed few differences in splicing or allelic imbalance of the TTN transcript between TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts. Studies with isolated human adult cardiomyocytes revealed no defects in contractility in cells from TTNtv+ compared to TTNtv− DCM hearts. Together, these data demonstrate the presence of truncated titin protein in human TTNtv+ DCM, show reduced amounts of full-length titin protein in TTNtv+ DCM hearts, and support combined dominant-negative and haploinsufficiency contributions to disease.

One-sentence summary:

Truncating mutations in TTN result in both truncated titin proteins and reduced full-length titin in patient hearts.

Editor’s Summary: Tracking titin in dilated cardiomyopathy

Truncating variants in TTN, the gene encoding the titin protein, underlie 15 to 25% of cases of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), but whether the disease is caused by haploinsufficiency or the presence of truncated titin proteins is not yet clear. Here, using tissues from the hearts of patients with DCM and TTN-truncating variants as well as human induced pluripotent stem cells differentiated into cardiomyocytes, Fomin et al. and McAfee et al. identified both the presence of truncated titin proteins and less-abundant full-length titin protein. These findings suggest that the presence of truncated titin proteins as “poison peptides” and titin haploinsufficiency both contribute to the pathogenesis of disease and should support the investigation of targeted therapies to treat DCM caused by TTN-truncating variants.

INTRODUCTION

Titin, encoded by the gene TTN, is a large protein that spans the entire sarcomere, from the Z-disk to the M-band, and that is essential for sarcomere integrity and function (1). Heterozygous variants in TTN that are predicted to lead to truncated titin proteins (TTN-truncating variants or TTNtvs) can be found in 10 to 20% of patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), compared to a population prevalence of ~1% (2–6), making TTNtvs the most common known cause of DCM. More recent studies have also shown a high prevalence of TTNtvs in cardiomyopathy induced by alcohol (7), pregnancy (8), and cancer therapies (9), suggesting that TTNtv-bearing individuals are susceptible to cardiomyopathy in response to numerous insults.

How TTNtvs mechanistically give rise to disease has remained controversial. Various hypotheses have been proposed, ranging from haploinsufficiency, whereby insufficient titin protein is generated from the intact allele to compensate for the TTNtv allele (a process that might be aggravated by cardiac insults requiring accelerated titin production, for example, alcohol toxicity, cardiotoxic drugs, or pregnancy) to “poison peptide,” whereby TTNtv protein, the protein encoded by the TTNtv-bearing allele, incorporates into the sarcomere, causing dysfunction (2, 10). Determining whether TTNtv proteins are present in adult human DCM hearts is paramount to distinguishing between these mechanisms and to understanding how TTNtvs cause heart disease. TTNtv proteins can be detected in immature induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) (11), as well as in skeletal muscle of some patients bearing TTNtvs (12), and work with polysomes has demonstrated that mRNA originating from the TTNtv allele can be found associated with ribosomes, suggesting that the allele can be translated (13). However, to date, repeated efforts to detect TTNtv proteins in affected human DCM hearts have failed (2, 4, 14). Moreover, proteomic studies in a rat model bearing an A-band TTNtv demonstrated complete absence of protein encoded by the TTNtv-bearing allele (13). The current leading theory is thus that haploinsufficiency of titin, rather than dominant-negative actions of the truncated peptide, leads to heart disease (2). However, reduced amounts of titin mRNA or protein expression in TTNtv human hearts have not been observed to date (2, 4, 14), challenging this theory.

In addition, the functional impact of TTNtvs on cardiomyocyte function has also remained undefined. Work with iPSC-CMs has demonstrated that mutant titin protein results in sarcomere insufficiency and impaired responses to stress (11), yet the extent to which these findings in immature iPS cells reflects the impact of TTNtvs on adult cardiomyocytes remains unclear. To better understand the impact of TTNtvs on human hearts, we leveraged access to a large collection, accumulated over the past 20 years, of hearts collected after transplantation, as well as an ongoing procurement of such hearts, to evaluate the impact of TTNtvs on cardiac TTN mRNA and protein and on intact adult cardiomyocyte contractility.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of TTNtvs in posttransplant DCM hearts

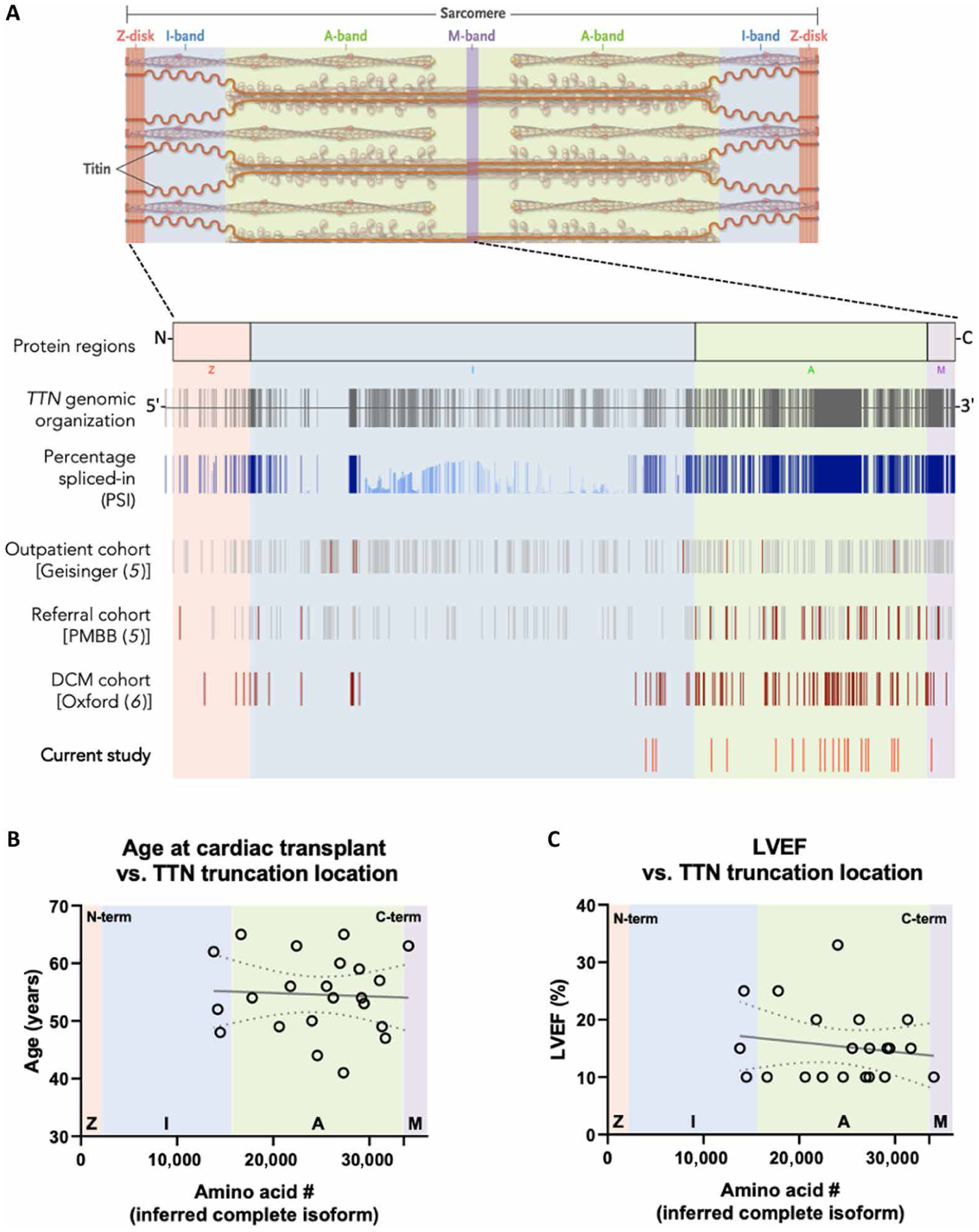

To evaluate the impact of TTNtvs on human hearts, we analyzed 184 hearts explanted from patients with nonischemic DCM and 14 nonfailing (NF) discarded donor hearts. Capture-based exome sequencing of TTN revealed 25 truncating variants in the DCM hearts (11 nonsense, 9 frameshift, and 5 splice site; table S1). Previous work demonstrated that, of the 364 exons encoded by TTN, only TTNtvs located in exons predicted to be spliced into the adult TTN transcripts [percentage spliced-in (PSI) >0.9, or hiPSI] are likely pathogenic (4, 5). Of the 25 TTNtvs identified above, 22 were located in hiPSI exons (12% prevalence, P < 2 × 10−23 compared with 0.5% prevalence of hiPSI TTNtvs in the reference gnomAD population). This prevalence is comparable to that reported in other DCM cohorts not requiring cardiac transplantation (4, 6). Seven of the TTNtvs (all hiPSI) were identical to variants annotated as pathogenic, or probably pathogenic, for DCM in the ClinVar database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar). DNA from the 14 NF hearts encoded no TTNtvs. No demographic differences or differences in cardiac morphology or hemodynamics were apparent between TTNtv− and TTNtv+ patients (Table 1). All 22 hiPSI TTNtvs were located in the C-terminal region of the I-band, A-band, or M-band region (Fig. 1A), akin to the distribution seen in DCM not requiring cardiac transplantation (Fig. 1A) (5, 6). Moreover, neither the age of the patient at time of transplant (Fig. 1B) nor pretransplant left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; Fig. 1C) correlated with the location of the TTNtv in the protein, suggesting that the location of the TTNtv does not influence severity of disease.

Table 1.

Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of 22 hiPSI TTNtv+ versus 158 TTNtv− patients with DCM.

| Patient statistics | TTNtv−DCM (n = 158) | TTNtv+DCM (n = 22) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.77 ± 11.06 | 54.59 ± 6.62 | 0.25 |

| Male (%) | 93 (59) | 16 (73) | 0.21 |

| African American (%) | 71 (45) | 6 (27) | 0.12 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.52 ± 17.28 | 84.56 ± 20.43 | 0.14 |

| Height (cm) | 171.46 ± 10.53 | 174.43 ± 10.62 | 0.22 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.56 ± 4.67 | 27.67 ± 5.38 | 0.31 |

| Heart weight (g) | 504.56 ± 148.24 | 475.73 ± 96.00 | 0.38 |

| History of comorbidity | |||

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 69 (44) | 13 (59) | 0.18 |

| VT/VF (%) | 77 (49) | 10 (45) | 0.75 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 41 (26) | 5 (23) | 0.77 |

| Hypertension (%) | 89 (56) | 10 (45) | 0.34 |

| Echocardiography | (n = 108) | (n = 18) | |

| LVEF (%) | 16.26 ± 7.40 | 15.38 ± 6.25 | 0.60 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 6.68 ± 1.35 | 6.77 ± 1.06 | 0.80 |

| LVESD (cm) | 6.10 ± 1.22 | 5.99 ± 1.03 | 0.73 |

For echocardiographic data, n represents the number of patients with complete echocardiography records. BMI, body mass index; VT/VF, ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic dimension.

Fig. 1. Genomic characteristics of 22 hiPSI TTNtvs, and associated clinical phenotypes, in patients with DCM who underwent cardiac transplantation.

(A): Top: Titin is an integral part of the cardiac sarcomere, spanning from Z-disk to M-line. Bottom: Regions of the TTN gene and protein are designated according to their spatial distribution in the sarcomere: Z-disk, I-band, A-band, and M-band. The 364 exons of the TTN gene and their associated percentage spliced-in (PSI) are shown, followed by the distribution of truncating variants in those exons identified in the Geisinger cohort (a general outpatient population) (5), in the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB) cohort (a tertiary care referral population) (5), a cohort of 1040 patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) from London and Singapore (6), and the variants identified in the current study. For the latter two, only hiPSI variants are noted. Variants found in patients with DCM are designated in red. (B and C) Lack of association between location of TTNtv and either age (B) or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; C) at the time of cardiac transplantation. Dotted lines indicate a 95% confidence interval about a linear regression, indicated by a solid line.

Impact of TTNtvs on TTN mRNA allelic balance and splicing, and genomic mRNA expression

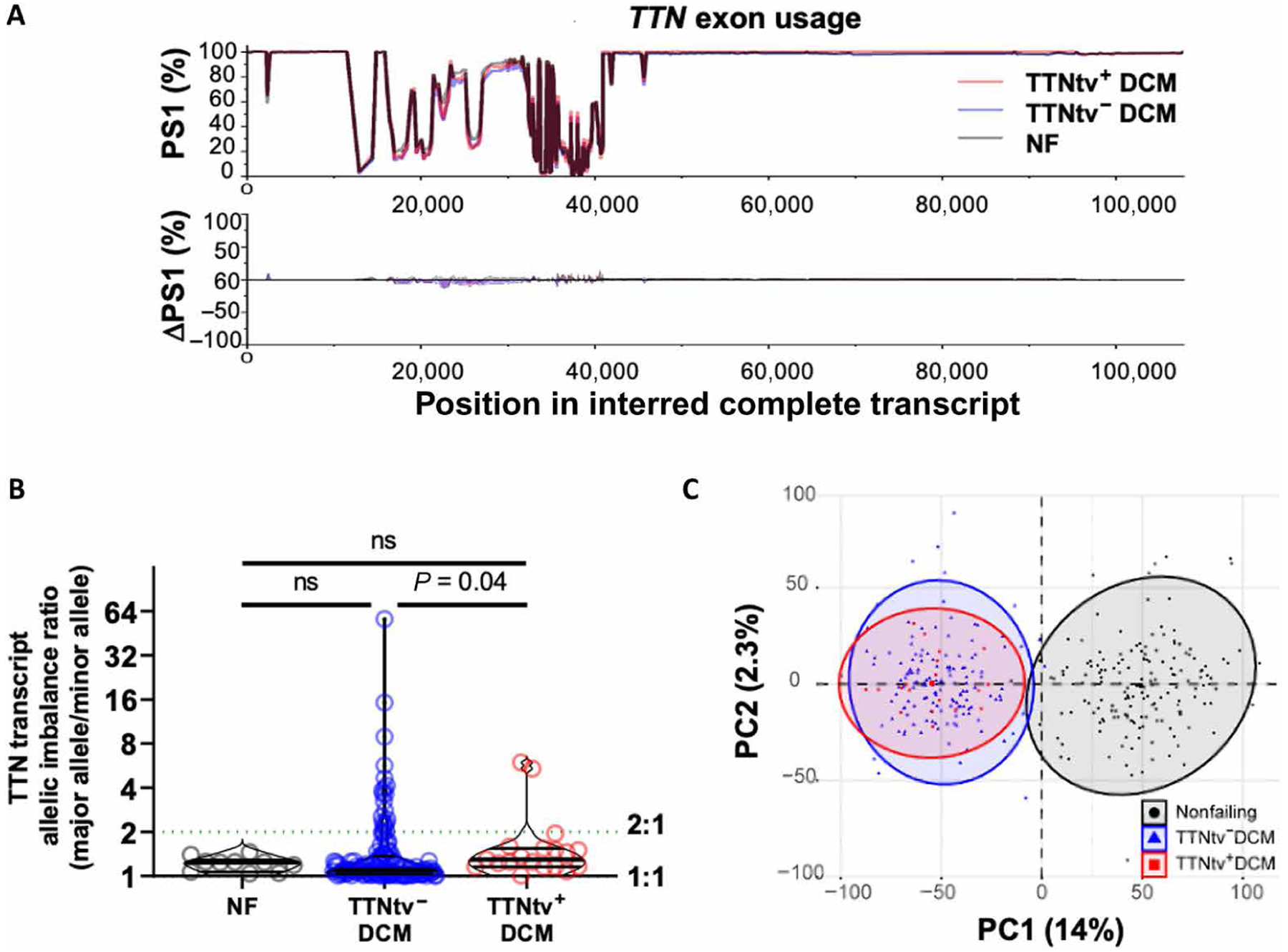

To investigate the impact of TTNtvs on mRNA expression, we examined genome-wide RNA sequencing of myocardium from 138 of the 184 DCM hearts, of which 19 had hiPSI TTNtvs and 10 were NF hearts. As noted above, the 364 exons of TTN are variably spliced, and alterations in TTN splicing caused by the presence of TTNtvs could, in principle, cause disease. However, we identified no differences in TTN exon usage between TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts (Fig. 2A), suggesting that TTN alternative splicing is not an important driver of TTNtv-induced pathology. We next tested whether the presence of a TTNtv affected allelic balance, for example, by leading to nonsense-mediated decay of the truncated transcript. To do this, we reconstructed each of the two individual alleles for each patient on the basis of the results of exome sequencing and by phasing known haplotypes (see Materials and Methods section). We detected no evidence of allelic imbalance in DCM, compared with NF hearts, and only marginal allelic imbalance in TTNtv+ DCM hearts compared with TTNtv− DCM hearts (Fig. 2, B and C). The little allelic imbalance in TTNtv+ DCM hearts did not correlate with age at transplant, ejection fraction, or location of truncation in TTN (fig. S1A). Thus, the presence of TTNtvs appeared to have little impact on the expression or splicing of TTN.

Fig. 2. Transcriptomic evaluation of hiPSI TTNtv+ versus TTNtv− posttransplant DCM hearts.

(A): Top: Minimal changes in TTN percentage spliced-in (PSI) exons between TTNtv+ DCM (n = 19), TTNtv− DCM (n = 119), and nonfailing (NF) hearts (n = 10). Bottom: Change in PSI (ΔPSI) compared between types. Red shading: TTNtv+ DCM minus NF. Blue shading: TTNtv− DCM minus NF. Gray trace: TTNtv+ DCM minus TTNtv− DCM. Of note, splicing patterns of TTN do differ in Black versus White populations (5). (B) Mildly increased allelic imbalance in TTNtv+ versus TTNtv− DCM heart (P = 0.04, n = 10, 129, and 19 in NF, TTNtv− DCM, and TTNtv+ DCM, respectively), shown as allelic imbalance expressed as the ratio of the more common allele over the less common allele. P value determined by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. Error bars report median and interquartile ranges: NF, 1.24 (1.06 to 1.29), TTNtv− DCM (1.03 to 1.37), TTNtv+ DCM (1.15 to 1.54). (C) Global transcriptomic profiling PCA separated NF (n = 166) from DCM hearts, but not TTNtv+ (n = 19) from TTNtv− DCM (n = 143) hearts. ns, not significant.

We next investigated the impact of TTNtvs on global mRNA expression. Principal components analysis of the RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets differentiated both TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts from NF hearts but did not differentiate between the two forms of DCM (Fig. 2D). After Bonferroni correction, only one gene (TPM3; tropomyosin α−3 chain) (fig. S1B) was significantly altered in TTNtv+ compared to TTNtv− DCM hearts. Of the top 20 most highly expressed genes, which mainly encode sarcomeric proteins, only TTN expression was nominally significantly reduced in TTNtv+ compared to TTNtv− DCM hearts (fig. S1C). This mild reduction in TTN transcript may reflect the impact of mild allelic imbalance. Thus, no gross transcriptional differences were apparent between TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts.

Impact of TTNtvs on human adult cardiomyocyte contractile function

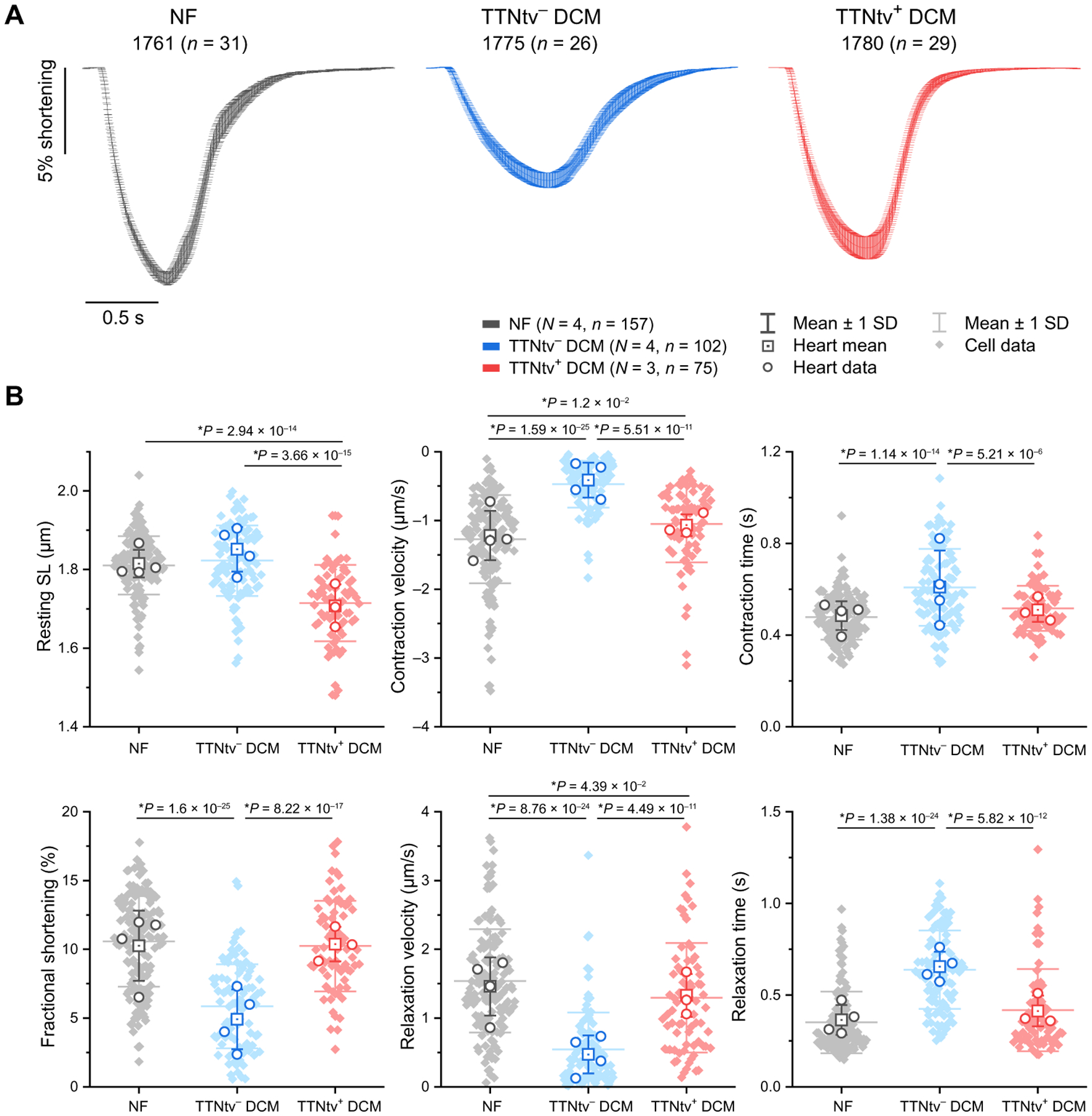

Experimental data with iPSCs have indicated that TTNtvs cause impairment of sarcomerogenesis (11), leading to the hypothesis that TTNtvs may impair the ability to maintain or restore sarcomeres damaged by stresses such as pregnancy, alcohol, or chemotherapy (2, 8, 9). To identify putative defects of sarcomere function in adult DCM hearts with TTNtvs, we isolated adult left ventricular cardiomyocytes (ACMs) from three patients with DCM with hiPSI TTNtvs via collagenase perfusion at the time of transplant, as described previously (15), and compared to a group of similarly treated TTNtv− DCM and NF controls (Fig. 3). Consistent with previous results (15), TTNtv− DCM ACMs showed impaired contractile function upon electrical stimulation when compared to NF controls. Unexpectedly, ACMs from TTNtv+ DCM hearts had at least equal or better fractional shortening, contraction and relaxation velocities, and contraction and relaxation times compared with TTNtv− DCM hearts, more closely approximating the values of NF ACMs (Fig. 3). TTNtv+ ACMs had shorter resting sarcomere lengths than either TTNtv− or NF ACMs. These data thus suggest that TTNtvs do not impair sarcomerogenesis in adult human hearts, in contrast to the case in iPSCs (11).

Fig. 3. Contractility of intact adult cardiomyocytes isolated from TTNtv+, TTNtv−, and NF human hearts.

ACM unloaded shortening was assessed from four NF donor hearts, four TTNtv− posttransplant hearts, and three hiPSI TTNtv+ posttransplant hearts. (A) Representative average ACM fractional shortening upon 0.5 Hz electrical stimulation from an NF, a TTNtv−, and a TTNtv+ heart. Patient ID is followed (in parenthesis) by n = number of myocytes assessed per heart, and data presented as mean shortening ± SD. (B) Quantification of the indicated contractile parameters of pooled data from all assessed hearts. N = number of hearts per group, n = number of cells evaluated per group. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni comparisons between myocytes (closed diamonds). Between-heart comparisons (open circles) were also performed, yielding similar results, and are reported in data file S2, along with full contractility parameters for each individual heart. SL, sarcomere length.

In light of this absence of overt worsening of contractility in TTNtv+ ACMs, we also sought to investigate whether other pathways were differentially affected between TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts. Alterations in autophagy have been suggested to contribute to disease progression in TTNtv+ DCM, including the observations of increased lipidated microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B-II) and p62 proteins, markers of activated autophagy, in rat models of TTNtv+ DCM (16, 17). However, Western blotting studies of proteins and posttranslational modifications involved in autophagy demonstrated no convincing differences in LC3, p62, or other proteins in TTNtv+ DCM compared to TTNtv− DCM hearts (fig. S2). Thus, alterations in autophagy that occur in DCM appear not to be specific to TTNtv+ DCM.

Detection of abundant peptides encoded by the TTNtv-bearing allele in TTNtv hearts

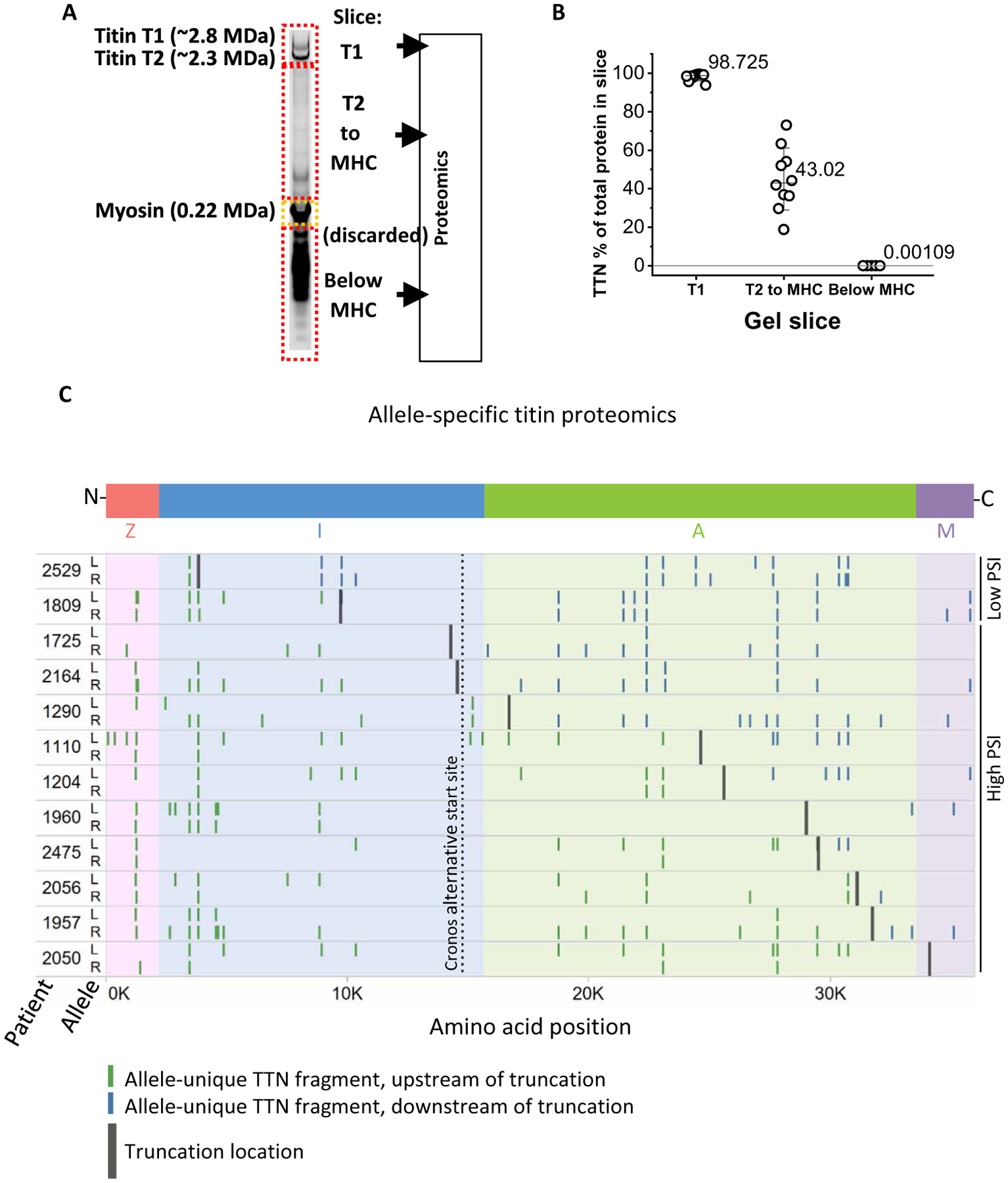

The observed alterations in resting sarcomere length in TTNtv+ versus TTNtv− hearts suggested that truncated titin proteins may be present and affecting cardiomyocyte function. To date, however, efforts at detecting truncated titin protein in human TTNtv+ DCM hearts have failed (4, 5, 14). Thus, existing evidence has been taken to support the paradigm that DCM induced by TTNtvs is caused by haploinsufficiency and not the dominant-negative actions of a truncated peptide (2). To probe more deeply into this question, we used proteomics to detect titin protein in TTNtv+ human DCM hearts. Proteins were prepared from 10 hiPSI and 2 loPSI TTNtv+ DCM hearts, separated by SDS–agarose gel electrophoresis, extracted from the gel [excluding the highly abundant myosin heavy chain (MHC) band], subjected to trypsin or chymotrypsin fragmentation, and analyzed by unbiased proteomics (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Proteomic detection of truncated titin proteins encoded by the allele bearing TTNtv in TTNtv heretozygous DCM hearts.

(A) Experimental scheme. Modified electrophoresis was used to excise three slices (labeled T1, T2-to-MHC, and below MHC), discarding the abundant myosin heavy chain (MHC) protein. Slices were then subjected to proteomic evaluation. (B) Relative abundance of peptides mapped to the TTN inferred complete isoform in each slice. (C) Mapping of identified TTN peptides to the titin protein predicted to be encoded by either allele (arbitrarily labeled L and R), using haplotype phasing and captured genomics sequences (one allele bears the TTNtv but cannot be ascribed to L or R based on phasing). Patients 2529 and 1809 bear nonpathogenic loPSI TTNtvs; the remainder are hiPSI TTNtvs. The Cronos alternative transcriptional start site is indicated.

We first tested the hypothesis that truncated titin may be actively cleaved or degraded into fragments that cause cellular proteotoxicity. However, we detected no titin peptides among proteins smaller than 200 kDa (about the size of myosin) in six of the samples and less than 1 in 100,000 peptides mapped to titin in the remaining samples (Fig. 4B). No difference in abundance of such peptides was seen in pathogenic hiPSI versus nonpathogenic loPSI TTNtv+ DCM hearts.

We next tested whether truncated titin could be detected among the larger proteins. The presence of heterozygous missense single nucleotide variants (SNVs) allowed assignment of peptide fragments to one allele or the other of each patient (arbitrarily labeled L and R alleles; Fig. 4C). Of note, there was a nonsignificant trend for higher total number of TTN missense variants per individual, and number of rare (<1%) missense variants, in TTNtv versus non-TTNtv individuals (13.5 versus 11.4, P = 0.07; and 5.6 versus 4.4, P = 0.07, respectively). Here, we used the missense variants as markers to identify the allelic source of detected peptides. Reconstruction of each complete TTN allele in each patient was achieved by phasing of the missense SNVs (see Materials and Methods). We identified 10 hiPSI TTNtv samples with sufficient number of missense variants to allow separate detection of proteins encoded by the two parental alleles. We also included two loPSI TTNtv samples to test the widely accepted notion that the reason loPSI variants are not pathogenic is because full-length protein is readily made by skipping the affected exon. In all 12 hearts, including all 10 samples with hiPSI TTNtv, peptide fragments could be assigned to both alleles, demonstrating that the TTNtv-bearing alleles are translated into protein (Fig. 4C). In 7 of the 10 hiPSI hearts, fragments downstream of the truncations could only be assigned to one allele, consistent with translation proceeding up to and stopping at the truncation site. The frequency of detection of peptides assigned to the allele bearing the TTNtv in these seven hearts was roughly half that assigned to the non-TTNtv allele upstream of the truncating site (4.1 versus 9.4 per sample, P = 0.007), indicating that the truncated protein was less abundant than full-length titin (note that the TTNtv could not be mapped to the L or R allele and that assignment of the allele that bears the TTNtv is thus inferred). In 1 of the 10 hiPSI hearts (#2050), with the most C-terminal TTNtv, no peptides were detected downstream of the truncation in either allele, although in this case as well, one allele mapped 42% as many peptides upstream of the truncation site as the other allele, again suggesting that the truncated protein is less abundant than full-length titin. In the remaining 2 of the 10 hiPSI cases (#1725 and #2164), peptides could be assigned to both alleles even downstream of the predicted truncation, and in both these cases, the TTNtv occurred 5′ to Cronos, a known alternative transcriptional start site for TTN (Fig. 4C), suggesting that these peptide fragments may be generated from the Cronos transcript. Last, in the two cases with a loPSI TTNtv (#2529 and #1809), fragments were detected from both alleles, both upstream and downstream of the truncation site, and at equivalent frequency, consistent with exclusion of the truncation-encoding exon. Together, these proteomic data indicate that fragments of truncated titin, encoded from the allele bearing a TTNtv, are present and abundant in TTNtv+ DCM hearts.

Detection of intact TTNtv protein in TTNtv+ hearts

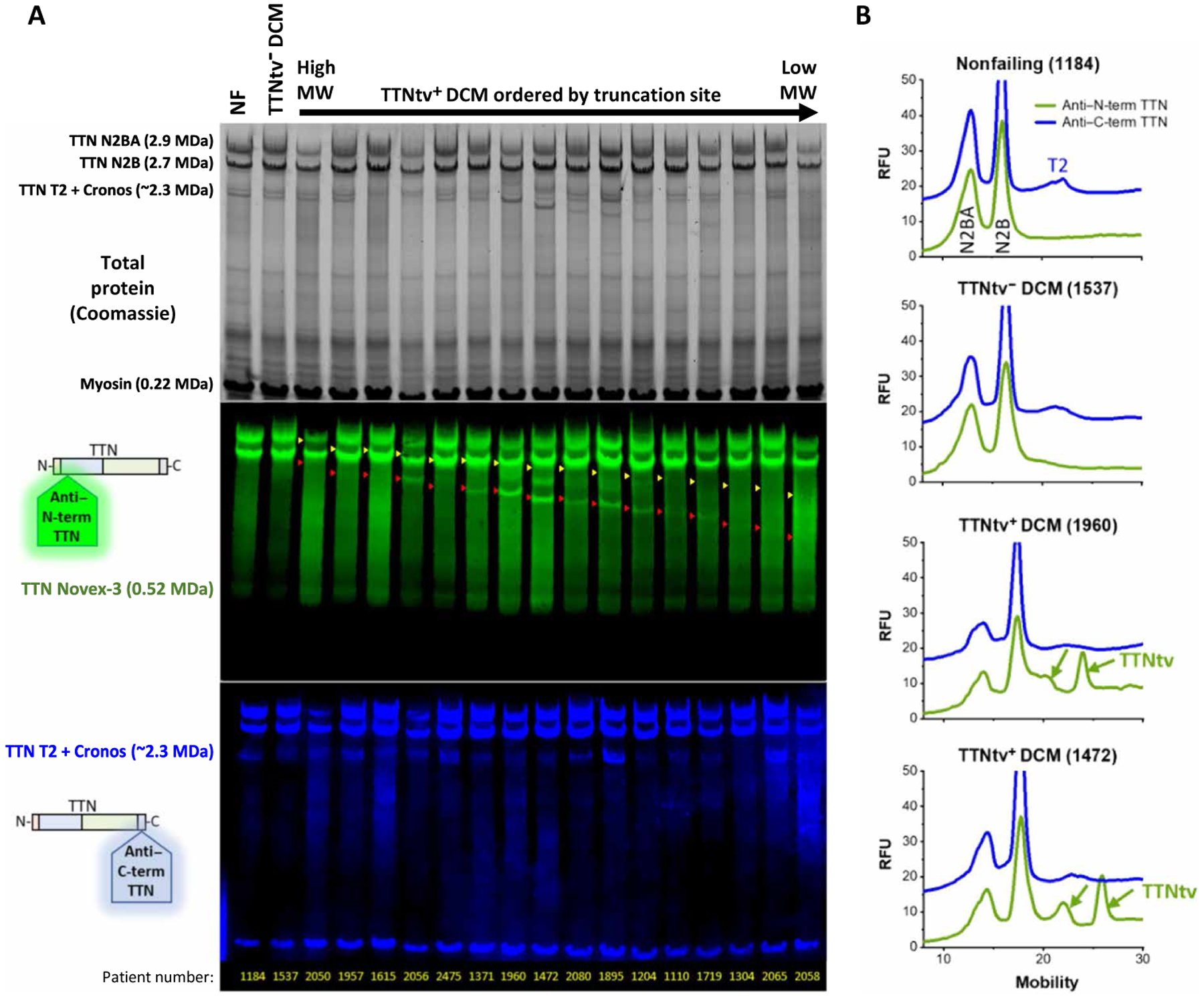

The proteomic data above demonstrated the presence of titin at a molecular weight >200kD (that is, in the gel slices containing proteins larger than myosin) but could not be used to infer the presence of intact titin. Therefore, to determine whether intact TTNtv protein was present in TTNtv+ DCM hearts, as well as to confirm the presence of TTNtv protein by methods orthogonal to proteomics, we size separated protein from TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts, using modified SDS–agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by protein detection using either Coomassie blue staining or two-color fluorescence immunoblotting. Cardiac titin is typically detected in Coomassie stains as three clear bands: N2BA (2.9 MDa), N2B (2.7 MDa), and a Cronos-derived protein (2.3 MDa) (18). In most samples from TTNtv+ hearts, additional bands were clearly visible (Fig. 5A, top). Immunoblotting with antibodies targeting the N- and C-terminal regions of titin demonstrated that all of these shorter titin proteins contained the N terminus (Fig. 5A, middle), whereas none of them contained the C terminus (Fig. 5A, bottom). Moreover, the observed bands migrated with a predicted size closely corresponding to the predicted molecular weight of the N2B isoform bearing the respective TTNtv (Fig. 5A, middle, red arrowheads). The more slowly migrating bands did not as reliably correspond to the predicted N2BA molecular weights, suggesting different processing of these isoforms. No distinct N terminus–containing proteins were detected in any sample below the predicted N2B TTNtv molecular weight, with the exception of Novex-3, a known 0.6-MDa cardiac titin isoform present in all samples. The intensity of the readily quantifiable lower N2B-derived TTNtv bands was considerably lower than that of full-length TTN proteins, ranging from 35% of the sum of N2B + N2BA to nearly undetectable (average 4%), indicating the abundance of TTNtv proteins is less than that of intact titin (fig. S3). Upper N2BA-derived TTNtv bands, if present, were not quantified, due to overlap with full-length isoforms, and therefore, some TTNtv band intensity was unaccounted for in this analysis. These data demonstrate the presence of TTNtv proteins, at the predicted size, in TTNtv+ DCM hearts.

Fig. 5. Detection of truncated titin proteins at predicted locations in TTNtv+ DCM hearts by gel electrophoresis and simultaneous two-color Western blotting.

(A) Total protein Coomassie staining (top), and Western blotting with antibodies directed against the N terminus (middle, green) and C terminus (bottom, blue) of titin protein, of 16 TTNtv+ DCM hearts, ordered by genetically predicted molecular weight (MW) of truncated titin protein. A nonfailing (NF) and a TTNtv− DCM heart are shown for comparison. TTN Novex: Protein encoded by an alternatively spliced isoform that does not contain the epitope recognized by the C-terminal antibody. TTN Cronos: A TTN isoform encoded by the transcript originating at the alternative start site Cronos, which does not contain the epitope recognized by the N-terminal antibody. Threshold and gamma are adjusted per channel for clarity of display. Yellow and red arrowheads represent the predicted mobilities for truncated N2BA and N2B, respectively, on the basis of the truncation site location within the genome. The lowermost band in the blue TTN C-terminal channel is nonspecific binding (NSB) to MHC. (B) Traces of Western blot lane fluorescence intensities with N-terminal (green) and C-terminal (blue) antibodies with control NF and TTNtv− DCM hearts (top two) and two sample TTNtv+ DCM hearts (bottom two). RFU, relative fluorescent units.

TTNtv proteins loosely associate with sarcomere-containing cellular fractions

To begin to address where in the cell TTNtv proteins can be found, we devised a method (fig. S4A) whereby cryopreserved cardiac tissue was first physically crushed on liquid nitrogen into a grossly cell-scale (~20 to 100 μm) powder (fig. S4B). The frozen powder was then added to relaxing buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, thus skinning cardiomyocytes and liberating soluble and membrane-bound proteins, but leaving large sarcomeric complexes intact and sedimentable by gentle centrifugation. Nonsarcomeric proteins, such as glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), subjected to this protocol were found in the supernatant, whereas sarcomeric or sarcomere-associated proteins, such as MHC, desmin, and full-length titin, as well as Cronos titin, were found in the pellet (fig. S4C). A total of 99.7% of full-length titin partitioned to the sarcomere-associated fraction. In three evaluated TTNtv+ DCM hearts, TTNtv protein was largely (~80%) found in the pellet (fig. S4, C and D), suggesting active incorporation of truncated titin into the sarcomere, although it could not be ruled out that truncated titin is instead in nonsarcomeric aggregates that are also found in the pellet. Despite >80% of truncated titin protein being retained in the sarcomere-containing fraction, TTNtv proteins were 49-fold more likely than full-length titin to dissociate from the sarcomere-containing fraction and partition to the soluble fraction. Thus, if truncated titin proteins do incorporate into the sarcomere, they are more loosely bound there than either full-length titin or Cronos titin. These data also demonstrated the consistent presence of appreciable quantities of Cronos titin protein in adult myocardium and that Cronos titin is tightly associated with sarcomere-containing fractions, consistent with its incorporation into the sarcomere.

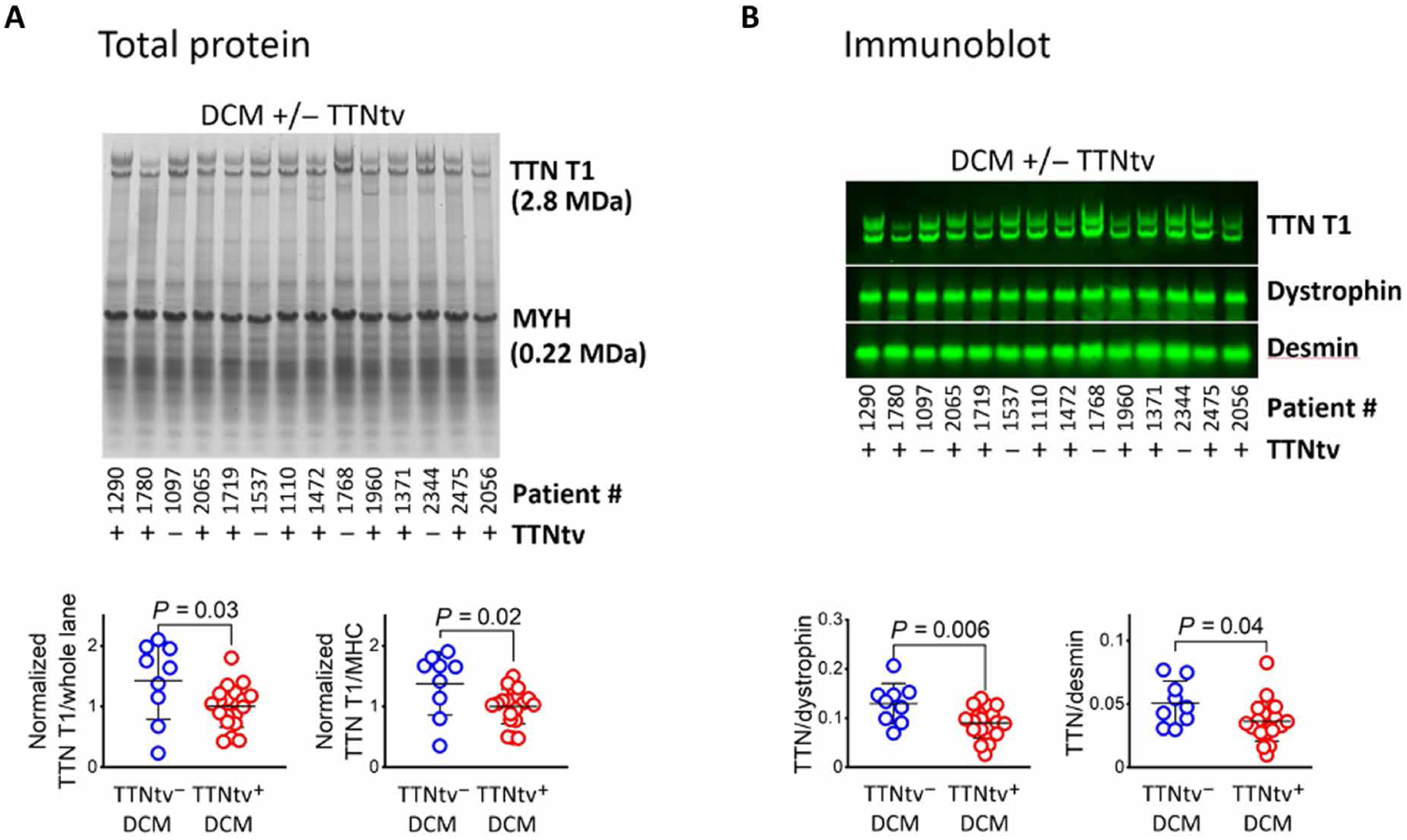

Evidence of reduced full-length TTN protein expression in TTNtv+ hearts

Last, we sought to address the question of whether TTNtv+ patients demonstrated evidence of reduced total TTN protein expression. In other words, to what extent does full-length titin, encoded by the nontruncating allele, compensate quantitatively for the absence of full-length titin translated from the TTNtv allele, despite observed equivalent transcription of both alleles and active translation from the transcript that encodes the TTNtv? We therefore quantified full-length titin proteins in TTNtv+ hearts, measured from Coomassie-stained gels or Western blots (Fig. 6 and fig. S5). The sum of full-length N2A and N2B isoforms was about 30% lower in TTNtv+ hearts, compared to TTNtv− hearts (Fig. 6 and fig. S5). This reduction was apparent whether detected TTN protein amounts were normalized to total tissue protein or to individual intracellular structural proteins (MHC, dystrophin, or desmin). Thus, full-length titin protein, expressed from the non–TTNtv-bearing allele, does not fully compensate for truncated titin in TTNtv+ DCM hearts.

Fig. 6. Evidence of reduced titin protein in TTNtv+ DCM myocardium.

Sample SDS–agarose gel and immunoblot of LV myocardium total protein samples from DCM hearts with and without TTNtv. (A) SDS–agarose gel stained with Coomassie blue, with total protein fluorescence detected at 700 nm. TTN relative abundance is expressed as normalized TTN total protein (T1, N2BA + N2B) band intensity divided by either whole lane or MHC (MYH) band intensity. (B) Immunoblot of replica gel of samples presented in (A), probed for titin, dystrophin, and desmin. TTN relative abundance is expressed as TTN total protein (T1, N2BA + N2B) band intensity divided by dystrophin or desmin band intensity. Quantifications of (A) and (B) are from gels displayed in this figure and additional gels present in fig. S5. For both gels and blots, there are a total of 8 TTNtv− and 20 TTNtv+ hearts. Image gamma was adjusted for clarity of display. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc Tukey correction.

DISCUSSION

We show here, using independent orthogonal methods including unbiased proteomics, modified gel electrophoresis, and immunological detection, that truncated titin proteins, encoded by the allele containing a TTNtv, are present and relatively abundant in hearts from TTNtv+ DCM patients. The presence of truncated titin protein might suggest that a dominant negative or poison peptide mechanism contributes to DCM in these patients. We also provide quantitative evidence of reduced amounts of titin protein in TTNtv+ hearts. Work performed in parallel by Linke and co-workers (19) revealed similar evidence of both the presence of truncated titin protein and of reduced amounts of total titin protein in TTNtv+ hearts. We thus propose that disease initiation may be multifactorial, involving both haploinsufficiency, as a consequence of reduced amounts of titin protein, and poison peptide mechanisms.

At least two possible poison peptide mechanisms can be envisioned: First, incorporation of the truncated proteins into the sarcomere, as suggested by our fractionation studies (fig. S4), may directly lead to sarcomeric dysfunction. We showed here that the size of the truncated protein does not appear to impact disease severity, as reflected in the need for transplantation (typically reflecting more severe disease), or LVEF or age at time of transplantation (Fig. 1). Thus, if integration of the truncated protein into the sarcomere contributes to disease, it can be inferred that integration of the N terminus is important and that the loss of structures associated with the M-line is sufficient to cause disease. The C terminus of titin encodes a putative kinase domain, mutations which are thought to cause skeletal muscle disease (12) and the absence of which in TTNtv protein could also be contributing to disease (2). On the other hand, integration of TTNtv protein into the sarcomere may not occur or may not be required for disease as suggested by the intact contractility of TTNtv+ ACMs (Fig. 3). For example, the TTNtv protein may be actively targeted for cleavage by the many proteases known to target titin, leading to disrupted protein homeostasis. Arguing against this model, however, is the absence of detectable small titin fragments in TTNtv+ hearts (Fig. 4A) or of substantially altered signatures of protein clearance such as macroautophagy in TTNtv+ hearts compared with TTNtv− hearts (fig. S2). The disease penetrance of TTNtvs is low, suggesting that pathogenicity requires additional “hits” in addition to a TTNtv. We have previously shown, in a large outpatient population, that 95% of subjects with TTNtvs, including some annotated as pathogenic in ClinVar, showed no signs of cardiomyopathy (5). This concept is consistent with observations by us and others that TTNtvs are also prominently found in cohorts of pregnancy-induced, alcohol-induced, and oncotherapy-induced cardiomyopathies (7–9), all representing potential “second hits.” How these various cardiac stressors mechanistically interact with TTNtvs to cause disease remains unclear, but it is possible that they may synergize with a poison peptide mechanism, for example, by altering proteostasis.

We also showed here that the presence of TTNtvs appears to have little to no effect on mRNA processing. We used allelic phasing to show that there is little to no TTN allelic imbalance in excess to that seen in TTNtv− hearts or any evidence for substantial alternative splicing of TTN in TTNtv+ hearts. In light of the lower detection of TTNtv protein compared to full-length titin, these observations imply that either mRNA transcripts that contain TTNtvs are translated less efficiently, or there is increased degradation of TTNtv protein. Ribosome profiling studies have suggested that translation of the TTNtv-bearing mRNA is intact (13), supporting the notion that TTNtv proteins are actively degraded.

TTNtv+ ACMs appeared to more closely preserve an NF contractility profile when compared to TTNtv− ACMs. These data differ from data acquired in TTNtv+ iPSC-derived CMs (11), in which contractility was affected, and more closely approximate data seen with isolated myofilaments from human TTNtv+ hearts (14), in which myofilament kinetics were more similar to NF than TTNtv− samples. We did note a uniquely decreased resting sarcomere length in TTNtv+ ACMs. This could be due to structural changes to the sarcomere, increased diastolic calcium concentrations, or elevated myofilament calcium sensitivity, the latter of which would be consistent with the increased fractional shortening observed in these cells relative to TTNtv− ACMs. Loss of ejection fraction in the context of seemingly preserved contractility could reflect other contextual factors, such as after-load, preload, and extracellular milieu. We also note that contractility was assessed in unloaded myocytes and thus may be insensitive to potential effects of TTNtvs on load-dependent regulation of myofilament function. The data also underscore the imperative to study adult cardiomyocytes.

Our data also support the conclusion that the presence of TTNtvs does not increase the likelihood of more severe disease, compared to patients with TTNtv− DCM. No differences in demographic or echocardiographic characteristics were apparent in TTNtv+ versus TTNtv− patients undergoing cardiac transplant. The 12% prevalence of hiPSI TTNtvs in our transplant cohort was no higher than that seen in cohorts of predominantly nontransplanted patients [for example, 11% in both a primary outpatient clinic DCM cohort and a secondary diagnostic referral DCM cohort (6)], indicating that TTNtvs do not increase the likelihood of undergoing transplantation, an indicator of disease severity. Last, global transcriptomic profiling revealed almost no substantial differences between TTNtv+ and TTNtv− DCM hearts. Together, these data demonstrate that TTNtvs contribute to disease progression but suggest that a common pathogenic pathway is shared between most forms of DCM, regardless of their TTNtv genetic status.

Limitations of our study include the limited number of hearts available. For example, we did not have tissue from hearts bearing TTNtvs in the N-terminal hiPSI exons, which are also likely pathogenic. The high variability, for example, in the observed amount of truncated titin protein, also renders some analyses underpowered. In addition, as noted above, the fact that all hearts are in end-stage heart failure precludes conclusions about the early stages of pathogenesis and may introduce ascertainment bias. Another limitation of these studies is that mRNAs were acquired from terminally failing hearts, affected by a range of medications and devices, which may lead to the null effects by introducing large variability. Two important limitations to our ACM studies are the possibility of cell ascertainment bias, if, for example, the presence of TTNtvs accelerated the demise of poorly functioning cells during the cellular isolation procedure and the fact that we did not perform cellular challenges, for example, with imposed mechanical load or adrenergic stimulation. Further studies in loaded, intact myocardial tissue preparations from TTNtv+ hearts will complement these single-cell and myofilament examinations. Last, it is also important to note that all of these cells and mRNAs were acquired from terminally failing hearts, and the pathophysiology of advanced heart failure may have masked earlier differences in the pathogenicity of TTNtv− versus TTNtv+ cardiomyopathy.

DCM is a multifactorial disease, for which to date no disease-specific therapies exist. Neurohormonal blockade and volume control remain the mainstays of therapy, but the prognosis of patients with DCM remains poor, with 5-year mortality approaching 50%. Our data, demonstrating the presence of truncated titin proteins in TTNtv+ DCM hearts, suggest that, in the subset of DCM patients with TTNtvs, targeting the truncated titin protein may provide a therapeutic opportunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The overall goal of the study was to evaluate transcriptomic and proteomic differences between human failing hearts bearing truncating variants in the gene TTN and those not bearing truncating titin variants. Failing human hearts were acquired after orthotropic transplantation, and all available hearts underwent genomic sequencing to identify hearts bearing truncating variants in TTN. No hearts were excluded from the analysis. Sample size was determined by number of available cases of hearts with TTNtvs. All subsequent studies were performed blind to genotype. No randomization was performed. For the RNA studies, previously published RNA-seq data from a large subset of this collection of hearts were analyzed, with no exclusions. For the adult cardiomyocyte functional studies, we retrospectively analyzed data that had been acquired from fresh cell isolations, blind to genotype. For the protein studies, protein was prepared from hearts identified as bearing TTNtvs and evaluated by proteomics, gel electrophoresis, and Western blotting.

Procurement and characterization of human hearts

Procurement of human myocardial tissue was performed under protocols and ethical regulations approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pennsylvania and the Gift-of-Life Donor Program (PA, USA) and as previously described (15). Briefly, failing human hearts of nonischemic origin were procured at the time of orthotropic heart transplantation at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania after informed consent from all participants. Only hearts from patients with nonischemic DCM were included; exclusion criteria included coronary artery disease, valvular disease, toxic agents, and anatomical abnormalities. NF hearts were obtained at the time of organ donation from cadaveric donors. In all cases, hearts were arrested in situ using ice-cold cardioplegia solution and transported on wet ice. TTNtv hearts were identified by genomic sequencing, and DCMs were classified by clinical diagnosis. The values reported for LVEF for patients with DCM in Table 1 are the last recorded LVEF measurement before heart transplant. These are derived via echocardiography. The most frequently used measurement approach is the modified Simpson’s method (biplane method of disks).

Human left ventricular myocyte isolation and contractility measurements

Human left ventricular myocytes were isolated as described previously (15). For this study, myocytes were isolated from 11 hearts (4 NF, 4 TTNtv− DCM, and 3 hiPSI TTNtv+: patients 1725, 1780, and 1719) for functional studies. Isolated myocytes were also used as part of separate, unrelated experiments that required short-term (48 hours) culture and viral transduction with a control or experimental adenovirus; in this study, only cells transduced with control virus were used for analysis. Culture medium consisted of F-10 (1×) Nutrient Mixture (Ham) [+] l-glutamine (Life Technologies, 11550-043) supplemented with insulin-transferrin selenium-X (Gibco, 51500-056), 20 mM HEPES, Primocin (1 μg/μl; InvivoGen, ant-pm-1), 0.4 mM extra CaCl2, 5% fetal bovine serum, and 25 μM cytochalasin D (Cayman, 11330). Viable myocytes were concentrated by gravity, and medium was added in culture so that neighboring cells were not in direct contact. Control viral constructs were permitted to express for 48 hours with a multiplicity of infection = 100 to 200.

Assessment of contractility by unloaded shortening was performed as in (15). Briefly, before contractility measurement, cultured human myocytes were transferred to fresh warm medium without cytochalasin D. Contractility was measured in a custom-fabricated cell chamber (IonOptix) mounted on an LSM Zeiss 880 inverted confocal microscope using either a 40× or 63× oil 1.4 numerical aperture objective and transmitted light camera (IonOptix MyoCam-S). Experiments were conducted at room temperature, and field stimulation was provided at 0.5 Hz with a cell stimulator (MyoPacer, IonOptix). After 10 to 30 s of pacing to achieve steady state, five traces were recorded and analyzed. Sarcomere length was measured optically by Fourier transform analysis (IonWizard, IonOptix). All experiments were performed and analyzed blind to genotype.

Tissue DNA and RNA-seq

DNA was extracted using Qiagen’s Gentra Puregene kit. DNA (1 μg) was sheared with a Diagenode BioRuptor for 30 min set on high with 30 s on/off. Sheared DNA underwent library prep using Agilent’s SureSelect XT2 kit. Barcoded exomes were enriched for DCM-associated genes using the Seidman DCM version 5.2 bait panel, which includes all 364 exons of TTN. Libraries were run on an Illumina NextSeq, and variants were called using Agilent’s SureCall. Total RNA was extracted using Qiagen MiRNeasy kit with DNAse on-column treatment; quality of RNA was verified by Agilent Bioanalyzer. RNA (1 μg) underwent library prep using Illumina’s TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit. RNA-seq libraries were run on an Illumina HiSeq2000. Reads were aligned using STAR and normalized with surrogate variable analysis. Variants were identified with the use of the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) HaplotypeCaller tool on the basis of GATK Best Practices. All but one identified hiPSI truncating variant, a 5–base pair (bp) deletion in patient 2065, were confirmed by means of Sanger sequencing. A close review of NextGen sequencing results of patient 2065 showed extensive coverage (>100) at that site, with >40% prevalence of the 5-bp deletion, suggesting that the failure to confirm by Sanger sequencing resulted from amplification artifact. This case was therefore included in subsequent analyses.

DNA exome sequencing phasing and TTN allelic imbalance analysis

To discriminate TTN alleles on maternal and paternal chromosomes, we phased the genomes of 210 subjects using EAGLE2 (version 2.4.1) provided by the Sanger Institute (https://sanger.ac.uk/science/tools/sanger-imputation-service) (20). Because of the lack of intron information, we used a reference-based phasing method using the haplotype reference consortium, which consists of 64,976 haplotypes at 39,235,157 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (http://haplotype-reference-consortium.org/). Only phased heterozygous SNPs were used for the subsequent analyses. In the allelic counting step, RNA-seq reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg19, and Samtools (version 1.10) mpileup (http://htslib.org/doc/samtoolsmpileup.html) was used to generate a “pileup” of RNA-seq bases (or indels) aligned on each given heterozygous SNP on TTN. A customized script was then used to parse the heterozygous variations and compute how many reads were aligned to each haplotype (allele_0 and allele_1) on TTN. For each heterozygous SNP, the allelic imbalance was computed as number_of_bases_matched _on_allele0/(number_of_bases_matched_on_allele0 + number_of_bases_matched_on_allele1). An allelic imbalance equal to 0.5 indicates exact 1:1 allelic ratio.

Myocardial protein isolation and gel electrophoresis

Previously frozen tissue samples stored at −80°C were handled on dry ice or liquid nitrogen. Roughly crushed fragments of myocardium free of epicardial fat of about 10 to 15 mg in mass were selected and further crushed on liquid nitrogen into a fine powder using a stainless steel rod as a pestle and a 2-ml stainless-steel microfuge tube as a mortar. Cryo-powdered heart tissue was resuspended in 40 volumes of titin homogenization buffer prepared according to (21, 22) and containing 8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 3% SDS, 50 mM tris (pH 6.8), a small amount of phenol red, and 75 mM freshly added dithiothreitol. The tissue was then homogenized with a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer until no fragments were visible, diluted 1:1 with 50:50 glycerol with 2× Roche cOmplete Mini protease inhibitor tablets, and briefly homogenized again. Samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and then spun at ~20,000g for 5 min at 10°C, and the pellet was discarded. Supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. For use, samples were thawed, briefly vortexed, and electrophoresed.

For SDS–agarose electrophoresis, total myocardial protein prepared as above was separated according to (22) with modifications according to a protocol provided by the Granzier laboratory. The running buffer was 50 mM tris, 0.384 M glycine (pH 8.3). Gels were cast from running buffer containing 1% Sea-Kem Gold agarose (Lonza) plus 30% glycerol. The gel was retained within the plates by a folded segment of nylon mesh placed between the plates. Fresh 2-mercaptoethanol was added to the upper buffer chamber at a dilution of 1:1000 just before sample loading. The gel apparatus was nearly completely filled with prechilled running buffer and placed in a slurry of ice during the run, which was conducted at a constant current of ~16 mA per gel. For total protein staining of SDS–agarose electrophoresis gels, gels were stained with GelCode blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and imaged on an Odyssey CLX (LiCor) infrared imager at 700 nm.

For immunoblotting of titin from SDS–agarose gels, protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a Bio-Rad semidry transfer apparatus with a discontinuous buffer system according to a protocol provided by the Granzier laboratory. The anode I solution contained 20 mM tris, 0.05% SDS, and 10% methanol (pH 10.4). Anode II solution contained 25 mM tris, 0.05% SDS, 10% methanol (pH 10.4), and the cathode buffer solution contained 25 mM tris, 0.05% SDS, 10% methanol, 40 mM CAPS (pH 10.4), each with 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol added just before assembly. The gel was soaked for 20 min before transfering in cathode buffer plus 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were transferred at 1.3 mA per square centimeter of gel for 1 hour. Gels were stained after transfer with GelCode blue to verify absence of detectible untransferred protein, and membranes were stained with Ponceau S to verify even transfer. Membranes for fluorescence imaging were blocked and probed using Intercept (Li-Cor) blocking buffer and standard blotting methods. Fluorescent blots were imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey FC infrared imager. Fluorescent gels and blots were quantified using ImageStudio (Li-Cor).

For routine SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis and Western blotting of nontitin proteins, proteins prepared as for titin gels were run on standard 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, stained for total protein using Ponceau S for transfer verification, probed according to standard immunoblotting methods, treated with chemiluminescent substrate, and exposed to film. Band quantifications were made using Image Studio or Empiria (Li-Cor) and normalized to indicated internal controls.

Myofibrillar physical isolation and immunohistochemistry

Cryo-crushed human myocardial tissue powder produced as described above was weighed in frozen form and then directly combined with 20 volumes (w/v) of modified skinning/relaxing buffer (23) composed of 20 mM imidazole (pH 7.0), 7.8 mM Na adenosine 5′-triphosphate, 12 mM magnesium propionate, 97.6 mM potassium propionate, and 0.5% Triton X-100, as well as Roche cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets used at twofold indicated concentration. After brief agitation, the mixture was incubated for about 15 min on ice and then spun at 5000g for 5 min to partition soluble components to the supernatant and insoluble myofibrillar and other components to the pellet. A ~300-μm pore size nylon mesh was used to exclude oversize fragments. The pellet was washed in the same buffer, and both supernatant and pellet were solubilized in titin-solubilizing buffer, bringing the final volume to 80-fold the original tissue input mass in titin solubilization buffer and 50:50 (v/v) glycerol, as described above. Complete partitioning of soluble (GAPDH) and insoluble markers (TTN T1, desmin, and myosin) were used to evaluate separation of soluble from insoluble components.

For cryo-crush immunofluorescence, cryo-crushed myocardium was added directly to neat methanol at −20°C and incubated for 8 min, quickly spun to pellet myocardial fragments, and resuspended in Seablock (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for continued processing for immunofluorescence staining, mounting, and imaging using standard methods.

Protein sequence analysis by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

Hearts included in proteomic analysis were chosen by sample availability and preference for the largest number missense mutations to facilitate sensitive detection by proteomics and separation of proteins encoded by the two parental alleles. Excised gel bands were cut into about 1 mm3 pieces. Gel pieces were then subjected to a modified in-gel trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion procedure (24). Gel pieces were washed and dehydrated with acetonitrile for 10 min, followed by removal of acetonitrile. Pieces were then completely dried in a speed-vac. Rehydration of the gel pieces was with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution containing modified sequencing-grade trypsin (12.5 ng/μl; Promega) at 4°C. After 45 min, the excess trypsin solution was removed and replaced with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution to just cover the gel pieces. Samples were then placed in a 37°C room overnight. Peptides were later extracted by removing the ammonium bicarbonate solution, followed by one wash with a solution containing 50% acetonitrile and 1% formic acid. The extracts were then dried in a speed-vac (~1 hour). The samples were then stored at 4°C until analysis.

Proteomics was performed by the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility. On the day of analysis, the samples were reconstituted in 5 to 10 μl of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) solvent A (2.5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid). A nanoscale reverse-phase HPLC capillary column was created by packing 2.6-μm C18 spherical silica beads into a fused silica capillary (100-μm inner diameter by ~30-cm length) with a flame-drawn tip (25). After equilibrating the column, each sample was loaded via a Famos autosampler (LC Packings) onto the column. A gradient was formed, and peptides were eluted with increasing concentrations of solvent B (97.5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid).

As peptides eluted, they were subjected to electrospray ionization and then entered into an LTQ Orbitrap Velos Pro ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were detected, isolated, and fragmented to produce a tandem mass spectrum of specific fragment ions for each peptide. Peptide sequences (and hence protein identity) were determined by matching protein databases with the acquired fragmentation pattern by the software program Sequest (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (26). All databases include a reversed version of all the sequences, and the data were filtered to between a 1 and 2% peptide false discovery rate. Files containing raw proteomic have been uploaded to the PRIDE Database.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro, GraphPad Prism, or Excel, except for bioinformatics, as noted. Multiple comparisons were made using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Tukey or Bonferroni multiple comparisons correction. In Fig. 2, multiple comparisons were made using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Gift-of-Life Donor Program, Philadelphia, PA, who helped provide NF heart tissue from unused donor hearts for this research, and the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility, Cell Biology Department, Harvard Medical School, for proteomics. We would like to thank H. Granzier and Z. Hourani (University of Arizona) for protocols for titin immunoblotting. Biorender was used to create the cryo-crush schematic.

Funding:

This work was supported by funding from NHLBI R01-HL133080 to B.P. and R01-HL126797 to Z.A., NIAMS T32 (AR 53461-12) to Q.M., the Gund Family Fund to K.M., and Department of Defense W81XWH18-1-0503 to Z.A. Human heart tissue was procured via support from the following grants: R01 AG17022, R01 HL089847, and R01 HL105993 to K.M. and R01 HL133080 to B.P.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials, with the exception of files containing raw proteomic data, which have been uploaded to the PRIDE Database.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Linke WA, Hamdani N, Gigantic Business: Titin properties and function through thick and thin. Circ. Res 114, 1052–1068 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yotti R, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Advances in the genetic basis and pathogenesis of sarcomere cardiomyopathies. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 20, 129–153 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MRG, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, Conner L, Depalma SR, McDonough B, Sparks E, Teodorescu DL, Cirino AL, Banner NR, Pennell DJ, Graw S, Merlo M, Di Lenarda A, Sinagra G, Bos JM, Ackerman MJ, Mitchell RN, Murry CE, Lakdawala NK, Ho CY, Barton PJR, Cook SA, Mestroni L, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med 366, 619–628 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AM, Ware JS, Herman DS, Schafer S, Baksi J, Bick AG, Buchan RJ, Walsh R, John S, Wilkinson S, Mazzarotto F, Felkin LE, Gong S, MacArthur JA, Cunningham F, Flannick J, Gabriel SB, Altshuler DM, Macdonald PS, Heinig M, Keogh AM, Hayward CS, Banner NR, Pennell DJ, O’Regan DP, San TR, de Marvao A, Dawes TJ, Gulati A, Birks EJ, Yacoub MH, Radke M, Gotthardt M, Wilson JG, O’Donnell CJ, Prasad SK, Barton PJ, Fatkin D, Hubner N, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Cook SA, Integrated allelic, transcriptional, and phenomic dissection of the cardiac effects of titin truncations in health and disease. Sci. Transl. Med 7, 270ra6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggerty CM, Damrauer SM, Levin MG, Birtwell D, Carey DJ, Golden AM, Hartzel DN, Hu Y, Judy R, Kelly MA, Kember RL, Kirchner HL, Leader JB, Liang L, McDermott-Roe C, Babu A, Morley M, Nealy Z, Person TN, Pulenthiran A, Small A, Smelser DT, Stahl RC, Sturm AC, Williams H, Baras A, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Dewey FE, Verma A, Zhang X, Correa A, Hall ME, Wilson JG, Ritchie MD, Rader DJ, Murray MF, Fornwalt BK, Arany Z, Genomics–First evaluation of heart disease associated with titin-truncating variants. Circulation 140, 42–54 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzarotto F, Tayal U, Buchan RJ, Midwinter W, Wilk A, Whiffin N, Govind R, Mazaika E, De Marvao A, Dawes TJW, Felkin LE, Ahmad M, Theotokis PI, Edwards E, Ing AY, Thomson KL, Chan LLH, Sim D, Baksi AJ, Pantazis A, Roberts AM, Watkins H, Funke B, O’Regan DP, Olivotto I, Barton PJR, Prasad SK, Cook SA, Ware JS, Walsh R, Reevaluating the genetic contribution of monogenic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 141, 387–398 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JS, Amor-Salamanca A, Tayal U, Govind R, Serrano I, Salazar-Mendiguchía J, García-Pinilla JM, Pascual-Figal DA, Nuñez J, Guzzo-Merello G, Gonzalez-Vioque E, Bardaji A, Manito N, López-Garrido MA, Padron-Barthe L, Edwards E, Whiffin N, Walsh R, Buchan RJ, Midwinter W, Wilk A, Prasad S, Pantazis A, Baski J, O’Regan DP, Alonso-Pulpon L, Cook SA, Lara-Pezzi E, Barton PJ, Garcia-Pavia P, Genetic etiology for alcohol-induced cardiac toxicity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 71, 2293–2302 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JS, Li J, Mazaika E, Yasso CM, Desouza T, Cappola TP, Tsai EJ, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kamiya CA, Mazzarotto F, Cook SA, Halder I, Prasad SK, Pisarcik J, Hanley-Yanez K, Alharethi R, Damp J, Hsich E, Elkayam U, Sheppard R, Kealey A, Alexis J, Ramani G, Safirstein J, Boehmer J, Pauly DF, Wittstein IS, Thohan V, Zucker MJ, Liu P, Gorcsan J III, McNamara DM, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Arany Z; IMAC-2 and IPAC Investigators, Shared genetic predisposition in peripartum and dilated cardiomyopathies. N. Engl. J. Med 374, 233–241 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Pavia P, Kim Y, Restrepo-Cordoba MA, Lunde IG, Wakimoto H, Smith AM, Toepfer CN, Getz K, Gorham J, Patel P, Ito K, Willcox JA, Arany Z, Li J, Owens AT, Govind R, Nunez B, Mazaika E, Bayes-Genis A, Walsh R, Finkelman B, Lupon J, Whiffin N, Serrano I, Midwinter W, Wilk A, Bardaji A, Ingold N, Buchan R, Tayal U, Pascual-Figal DA, de Marvao A, Ahmad M, Garcia-Pinilla JM, Pantazis A, Dominguez F, Baksi AJ, O’Regan DP, Rosen SD, Prasad SK, Lara-Pezzi E, Provencio M, Lyon AR, Alonso-Pulpon L, Cook SA, DePalma SR, Barton PJR, Aplenc R, Seidman JG, Ky B, Ware JS, Seidman CE, Genetic variants associated with cancer therapy–induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation 140, 31–41 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tharp CA, Haywood ME, Sbaizero O, Taylor MRG, Mestroni L, The giant protein titin’s role in cardiomyopathy: Genetic, transcriptional, and post-translational modifications of TTN and their contribution to cardiac disease. Front. Physiol 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinson JT, Chopra A, Nafissi N, Polacheck WJ, Benson CC, Swist S, Gorham J, Yang L, Schafer S, Sheng CC, Haghighi A, Homsy J, Hubner N, Church G, Cook SA, Linke WA, Chen CS, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Titin mutations in iPS cells define sarcomere insufficiency as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Science 349, 982–986 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerull B, Gramlich M, Atherton J, McNabb M, Trombitás K, Sasse-Klaassen S, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Granzier H, Labeit S, Frenneaux M, Thierfelder L, Mutations of TTN, encoding the giant muscle filament titin, cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet 30, 201–204 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Heesch S, Witte F, Schneider-Lunitz V, Schulz JF, Adami E, Faber AB, Kirchner M, Maatz H, Blachut S, Sandmann C-L, Kanda M, Worth CL, Schafer S, Calviello L, Merriott R, Patone G, Hummel O, Wyler E, Obermayer B, Mücke MB, Lindberg EL, Trnka F, Memczak S, Schilling M, Felkin LE, Barton PJR, Quaife NM, Vanezis K, Diecke S, Mukai M, Mah N, Oh S-J, Kurtz A, Schramm C, Schwinge D, Sebode M, Harakalova M, Asselbergs FW, Vink A, De Weger RA, Viswanathan S, Widjaja AA, Gärtner-Rommel A, Milting H, Remedios CD, Knosalla C, Mertins P, Landthaler M, Vingron M, Linke WA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Rajewsky N, Ohler U, Cook SA, Hubner N, The translational landscape of the human heart. Cell 178, 242–260.e29 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vikhorev PG, Smoktunowicz N, Munster AB, Copeland ON, Kostin S, Montgiraud C, Messer AE, Toliat MR, Li A, Dos Remedios CG, Lal S, Blair CA, Campbell KS, Guglin M, Richter M, Knöll R, Marston SB, Abnormal contractility in human heart myofibrils from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy due to mutations in TTN and contractile protein genes. Sci. Rep 7, 14829 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CY, Caporizzo MA, Bedi K, Vite A, Bogush AI, Robison P, Heffler JG, Salomon AK, Kelly NA, Babu A, Morley MP, Margulies KB, Prosser BL, Suppression of detyrosinated microtubules improves cardiomyocyte function in human heart failure. Nat. Med 24, 1225–1233 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schafer S, De Marvao A, Adami E, Fiedler LR, Ng B, Khin E, Rackham OJL, Van Heesch S, Pua CJ, Kui M, Walsh R, Tayal U, Prasad SK, Dawes TJW, Ko NSJ, Sim D, Chan LLH, Chin CWL, Mazzarotto F, Barton PJ, Kreuchwig F, De Kleijn DPV, Totman T, Biffi C, Tee N, Rueckert D, Schneider V, Faber A, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Linke WA, Kovalik J-P, O’Regan D, Ware JS, Hubner N, Cook SA, Titin-truncating variants affect heart function in disease cohorts and the general population. Nat. Genet 49, 46–53 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou J, Ng B, Ko NSJ, Fiedler LR, Khin E, Lim A, Sahib NE, Wu Y, Chothani SP, Schafer S, Bay B-H, Sinha RA, Cook SA, Yen PM, Titin truncations lead to impaired cardiomyocyte autophagy and mitochondrial function in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet 28, 1971–1981 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaunbrecher RJ, Abel AN, Beussman K, Leonard A, Von Frieling-Salewsky M, Fields PA, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Yang X, Macadangdang J, Kim D-H, Linke WA, Sniadecki NJ, Regnier M, Murry CE, Cronos titin is expressed in human cardiomyocytes and necessary for normal sarcomere function. Circulation 140, 1647–1660 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fomin A, Gärtner A, Cyganek L, Tiburcy M, Tuleta I, Wellers L, Folsche L, Hobbach AJ, von Frieling-Salewsky M, Unger A, Hucke A, Koser F, Kassner A, Sielemann K, Streckfuß-Bömeke K, Hasenfuss G, Goedel A, Laugwitz K-L, Moretti A, Gummert JF, dos Remedios CG, Reinecke H, Knöll R, van Heesch S, Hubner N, Zimmermann WH, Milting H, Linke WA, Truncated titin proteins and titin haploinsufficiency are targets for functional recovery in human cardiomyopathy due to TTN mutations. Sci. Transl. Med 13, eabd3079 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loh P-R, Danecek P, Palamara PF, Fuchsberger C, Reshef YA, Finucane HK, Schoenherr S, Forer L, McCarthy S, Abecasis GR, Durbin R, Price AL, Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat. Genet 48, 1443–1448 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu C, Guo W, Detection and quantification of the giant protein titin by SDS-agarose gel electrophoresis. MethodsX 4, 320–327 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren CM, Krzesinski PR, Campbell KS, Moss RL, Greaser ML, Titin isoform changes in rat myocardium during development. Mech. Dev 121, 1301–1312 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivas-Pardo JA, Li Y, Mártonfalvi Z, Tapia-Rojo R, Unger A, Fernández-Trasancos Á, Herrero-Galán E, Velázquez-Carreras D, Fernández JM, Linke WA, Alegre-Cebollada J, (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2019).

- 24.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M, Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem 68, 850–858 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng J, Gygi SP, Proteomics: The move to mixtures. J. Mass Spectrom 36, 1083–1091 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR, An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 5, 976–989 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials, with the exception of files containing raw proteomic data, which have been uploaded to the PRIDE Database.