Abstract

We have developed a DNA-based assay to reliably detect brown rot and white rot fungi in wood at different stages of decay. DNA, isolated by a series of CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) and organic extractions, was amplified by the PCR using published universal primers and basidiomycete-specific primers derived from ribosomal DNA sequences. We surveyed 14 species of wood-decaying basidiomycetes (brown-rot and white-rot fungi), as well as 25 species of wood-inhabiting ascomycetes (pathogens, endophytes, and saprophytes). DNA was isolated from pure cultures of these fungi and also from spruce wood blocks colonized by individual isolates of wood decay basidiomycetes or wood-inhabiting ascomycetes. The primer pair ITS1-F (specific for higher fungi) and ITS4 (universal primer) amplified the internal transcribed spacer region from both ascomycetes and basidiomycetes from both pure culture and wood, as expected. The primer pair ITS1-F (specific for higher fungi) and ITS4-B (specific for basidiomycetes) was shown to reliably detect the presence of wood decay basidiomycetes in both pure culture and wood; ascomycetes were not detected by this primer pair. We detected the presence of decay fungi in wood by PCR before measurable weight loss had occurred to the wood. Basidiomycetes were identified to the species level by restriction fragment length polymorphisms of the internal transcribed spacer region.

Wood is an important renewable and biodegradable natural resource with a multitude of uses. Wood is used extensively as a structural material for buildings, wharves, telephone poles, and furniture due to its high strength per unit weight, its versatility, and its variety. Wood also serves as the industrial raw material for the manufacture of paper and paper products, wood composites, and other products made from cellulose, such as textiles and cellophane. In many parts of the world wood is used as a fuel for heating and cooking.

The primary biotic decomposers of wood are basidiomycete decay fungi, which can attack and degrade both wood in the forest and wood in service. In the forest ecosystem wood decay fungi play an important role in carbon and nitrogen cycling and help to convert organic debris into the humus layer of the soil. Some fungi attack living trees; others invade downed timber and slash on the forest floor, lumber, and wood in service. Wood decay basidiomycetes colonize and degrade wood using enzymatic and nonenzymatic processes. Brown-rot fungi preferentially attack and rapidly depolymerize the structural carbohydrates (cellulose and hemicellulose) in the cell wall leaving the modified lignin behind. White-rot fungi can progressively utilize all major cell wall components, including both the carbohydrates and the lignin. As decay progresses the wood becomes discolored and loses strength, weight, and density. Decay and discoloration caused by fungi are major sources of loss in both timber production and wood use, with losses of 15 to 25% marketable wood volume in standing timber and of 10 to 15% in wood products during storage and conversion. Each year ca. 10% of the timber cut in the United States is used to replace wood in service that has decayed, resulting in the expenditure of hundreds of millions of dollars for raw materials, labor, and liability (22).

Brown rots rapidly and drastically reduce wood strength early in the decay process, while white rots cause a slower progressive decrease in wood strength. Brown-rot fungi can reduce wood strength by as much as 75% at less than 5% weight loss of the wood (22). For this reason it is important to develop methods which can detect wood decay very early, at the incipient stage prior to the occurrence of significant strength loss. Techniques which have been used to detect incipient decay include isolation and culturing of fungi, chemical staining, nuclear magnetic resonance, and electrical resistance, as well as serological methods, such as immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (3). ELISA has been found to be a sensitive method for detecting incipient decay (4, 11), but the assay sensitivity can be inhibited by wood extractives (12). Optimal methods for early detection of decay for wood in service have not been developed.

The development of the DNA-based PCR (14) and taxon-specific primers (2, 6, 7, 16, 17) is making it increasingly feasible to detect and study fungi in their natural substrates. A DNA-based method to detect the presence of wood decay fungi would potentially use only small amounts of wood, thus allowing for nondestructive sampling. The extreme sensitivity and potential specificity of the assay would theoretically allow for the detection of fungal decay agents at an incipient stage enabling remedial biocidal treatments to be applied before significant strength loss had occurred. Detection of specific decay agents is also a necessary prerequisite to allow evaluation of fungal colonization and proliferation in preservative-treated woods undergoing remediation. Specific and sensitive assay procedures would aid in the monitoring and development of successful fungus-based bioremediation technologies.

For our DNA-based detection method, we selected the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region (ITSI, the 5.8S ribosomal DNA [rDNA], and ITSII) as the target sequence for amplification for three reasons. The ITS region is present at a very high copy number in the genome of fungi, as part of the tandemly repeated nuclear rDNA; this, coupled with PCR amplification, should produce a highly sensitive assay. The DNA sequences of the ITSI and ITSII are highly variable; this feature can be exploited to generate restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns to identify wood decay fungi or to design taxon-specific primers. The European Armillaria species Armillaria cepistipes, A. gallica, A. borealis, A. ostoyae, and A. mellea are clearly delimited by RFLPs of rDNA (18). RFLPs generated by restriction digestion of the PCR-amplified ITS region have been used successfully to study intraspecific variation in A. ostoyae (17), to identify ectomycorrhizal fungi to the genera and/or species level (5, 7, 8, 9, 10), and to identify intersterility groups of Heterobasidion annosum (6). In designing an assay to detect fungi by PCR amplification using total DNA isolated from infected plant material as the template, it is important to be able to discriminate between DNAs of fungal and plant origin. Primers which specifically amplify the ITS region from only fungal DNA (7) and not plant DNA are available. These fungus-specific primers were originally designed to identify fungal symbionts directly from ectomycorrhizae and to identify rusts, which are obligate parasites, in the host tissue (7). More recently, these primers have been used to study the community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a pine forest (8) and the genetic structure of a natural population of Suillus pungens (2).

The objectives of our study were (i) to rigorously test the specificity of the basidiomycete-specific primer (7) by surveying a large number of wood decay basidiomycetes, as well as wood-inhabiting ascomycetes (pathogens, endophytes, and saprophytes); (ii) to optimize the PCR assay conditions for specific detection of brown-rot and white-rot fungi in wood; (iii) to identify the PCR-detected fungi to species via RFLPs of the amplified internal transcribed spacer region; and (iv) to develop a DNA-based method to detect incipient stages of wood decay, thus allowing remedial treatments to be applied to wooden structural members before substantial strength loss has occurred.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal culture.

The fungi used in this study and their sources are given in Table 1. Cultures were grown on plates of malt agar at room temperature for use in DNA isolation or as inocula for soil block jars.

TABLE 1.

Amplification of ITS region from DNA isolated from pure fungal cultures

| Species | Isolate | Sourcea | Ecologyb | PCR amplificationc with primer pair:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1-F–ITS4 | ITS1-F–ITS4-B | ||||

| Basidiomycetes | |||||

| Coniophora puteana | Fp-90099-Sp | b | Brown rot, C | + | + |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | K8sp | This lab | Brown rot, C | + | + |

| Gloeophyllum sepiarum | 10-BS2-2 | h | Brown rot, C | + | + |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | This lab | Brown rot, HCS | + | + | |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | Mad-617-R | b | Brown rot, HCS | + | + |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | ATCC 11539 | a | Brown rot, HCS | + | + |

| Leucogyrophana pinastri | i | Brown rot, C | + | + | |

| Postia placenta | This lab | Brown rot, C | + | + | |

| Postia placenta | Mad-698-R | b | Brown rot, C | + | + |

| Serpula lacrimans | Harm-888-R | b | Brown rot, CS | + | + |

| Serpula lacrimans | ATCC 36335 | a | Brown rot, CS | + | + |

| Irpex lacteus | KTS 003 | g | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Irpex lacteus | ATCC 60993 | a | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Lentinula edodes | 117=1t(d) | b | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | This lab | White rot, H | + | + | |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | ATCC 24725 | a | White rot, H | + | + |

| Resinicium bicolor | HHB-8850-sp | b | White rot, C | + | + |

| Resinicium bicolor | ATCC 44175 | a | White rot, C | + | + |

| Resinicium bicolor | ATCC 64897 | a | White rot, C | + | + |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | MB-1880-sp | b | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | ATCC 44178 | a | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | ATCC 64896 | a | White rot, CH | + | + |

| Trametes versicolor | This lab | White rot, H | + | + | |

| Trametes versicolor | Fp-101664-Sp | b | White rot, H | + | + |

| Trichaptum abietinum | 1247 MJL | b | White rot, C | + | + |

| Pisolithus tinctorius | ATCC 38054 | a | Ectomycorrhiza | + | + |

| Rhizoctonia solani | 1AP | c | Pathogen of herbaceous plants | + | + |

| Ascomycetes | |||||

| Aureobasidium pullulans | ATCC 34621 | a | Saprophyte, CH | + | − |

| Ceratocystis pilifera | ATCC 60758 | a | Wood stain, CH | + | − |

| Cytospora eutypelloides | CMI 140798 | c | Canker | + | − |

| Diatrypella favacea | c | Dead wood, H | + | − | |

| Diatrypella prominens | c | Canker, H | + | − | |

| Hormonema dematiodes | c | Endophyte, C | + | − | |

| Hormonema dematiodes | Scots pine MI | c | Endophyte, C | + | − |

| Leucostoma cincta | Ontario/Biggs | c | Canker, R | + | − |

| Leucostoma cincta | Lp66 | c | Canker, R | + | − |

| Leucostoma kunzei | c | Canker, C | + | − | |

| Leucostoma persoonii | LCN | c | Canker, RH | + | − |

| Ophiostoma ulmi | ATCC 32439 | a | Dutch elm disease | + | − |

| Pestalotiopsis sp. | c | Endophyte, C | + | − | |

| Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii | ATCC 24725 | c | Needle blight, C | + | − |

| Phialocephala fusca | ATCC 62326 | a | Softrot, C | + | − |

| Phialophora mutabilis | ATCC 42792 | a | Softrot, H | + | − |

| Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii | Spruce MI | c | Needle blight, C | + | − |

| Scleroderris lagerbergii | 1877 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Scleroderris lagerbergii | 28379 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Sirococcus conigenus | c | Canker, C | + | − | |

| Sphaeropsis sapinea | A411 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Sphaeropsis sapinea | A472 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Sphaeropsis sapinea | B416 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Sphaeropsis sapinea | B468 | c | Canker, C | + | − |

| Trichoderma reesei | ATCC 26921 | a | Saprophyte, CH | + | − |

| Trichoderma viride | ATCC 32630 | a | Saprophyte, CH | + | − |

| Valsa ceratophora | c | Canker, H | + | − | |

| Valsa germanica | c | Canker, H | + | − | |

| Valsa nivea | c | Canker, H | + | − | |

| Valsa sordida | c | Canker, H | + | − | |

| Xenomeris abietis | c | Canker, C | + | − | |

| Chaetomium globosum | d | Cosmopolitan | + | − | |

| Sordaria sp. | f | Dung | + | − | |

a, American Type Culture Collection; b, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wis.; c, Gerard Adams, Michigan State University; d, Barry Goodell, University of Maine, Orono; e, Dilip Lakshman, University of Maine, Orono; f, David Lambert, University of Maine, Orono; g, Kevin Smith, University of New Hampshire; h, Swedish Agricultural University, Uppsala, Sweden; i, Paul I. Morris, Forintek Canada Corp., Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

C, conifers; H, hardwoods; R, Rosaceae; S, wood in service.

Primer ITS1-F is specific for higher fungi, primer ITS4 is a universal primer, and primer ITS4-B is specific for basidiomycetes.

Soil block culture.

Modified ASTM soil block jars (1) were set up as follows. A soil mix (1:1:1 by volume) was prepared by mixing equal volumes of potting soil, sphagnum moss, and vermiculite and then moistened with deionized distilled water. About 1 cup of the mix was placed in each pint-sized Mason jar, and water was allowed to absorb overnight. The next day, 20 ml of water was added per jar so that the soil mix was moist and a little free water was present. Two pieces of birch tongue depressor were placed on the soil surface to serve as feeder strips. Lids were inverted to prevent sealing and screwed onto the jars with rings. Jars were autoclaved for 30 min. Two days later the jars were again autoclaved for 30 min.

The feeder strips in each jar were inoculated with culture blocks (ca. 0.5 cm3) of the appropriate fungal isolate, and one culture block was placed at each end of each feeder strip. In uninoculated control jars, blocks of sterile malt agar were used. Jars were incubated at room temperature to allow fungal colonization of feeder strips.

Radial or longitudinal sections of spruce sapwood (1 by 1 by 0.25 in. [1 in. = 25.4 mm]) cut from the same tree were oven dried at 100°C for 48 h, weighed, and then autoclaved for 30 min enclosed in glass petri dishes. After cooling, the wood blocks were added aseptically to the jars at one block per jar. Each experiment used wood blocks cut from only radial sections or from only longitudinal sections. Wood blocks cut from radial sections were placed so that a transverse face contacted the top of the colonized feeder strips. Wood blocks cut from longitudinal sections were placed so that a longitudinal face contacted the top of the colonized feeder strip. Jars were incubated at room temperature to allow colonization of the spruce blocks.

After the appropriate colonization time, the wood blocks were harvested aseptically, observing precautions to prevent cross-contamination of the samples at all steps of processing. Mycelia on the surface of the block were removed by gently scraping them with a razor blade, a new blade being used for each block. The fresh weight was recorded. The block was cut in half vertically, i.e., perpendicular to the face of the block that had contacted the colonized feeder strip. One-half was placed in a small plastic sample bag, labeled, and stored at −70°C for DNA isolation. The fresh weight of the other half block was recorded, after which it was oven dried at 100°C for 48 h, and its dry weight recorded to allow calculation of the final dry weight of the whole block at harvest based on the following ratio: total fresh weight/calculated total dry weight = partial fresh weight/partial dry weight. Wood decay was estimated as the percent dry weight loss as follows: percent weight loss = [1 − (final dry weight/initial dry wt)] × 100.

DNA isolation.

DNA was isolated from fresh mycelia taken from the surface of plate cultures, from lyophilized mycelia, or from infected wood by extraction with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol, followed by organic extractions and isopropanol precipitation of the DNA. Our method is based on those of Taylor et al. (19) and Wilson (21). For fresh mycelia a 2× CTAB extraction buffer (2% [wt/vol] CTAB; 100 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0; 1.4 M NaCl; 20 mM EDTA; 0.2% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol) was used, with the β-mercaptoethanol being added just prior to use. For lyophilized mycelia or dry tissues such as wood samples, a 1× CTAB extraction buffer (diluted 2× buffer) was used. It is especially important to use the 1× CTAB extraction buffer for wood samples; otherwise, the aqueous and organic phases invert due to rehydration of the wood when the 2× CTAB extraction buffer is used.

Wood blocks were sampled by drilling through noninoculated wood surfaces. Precautions were observed during drilling of the wood blocks to prevent cross-contamination of samples. Both the work table and gloves were swabbed with 70% ethanol to surface sterilize them and to collect any bits of sawdust before and after drilling each sample. A rechargeable cordless drill was used because it has less surface area, fewer crevices, and no cord to collect dirt and sawdust, and a molded housing which can be easily wiped clean with 70% ethanol. Drill bits were carefully cleaned with laboratory detergent, rinsed, soaked in 95% ethanol, and flame sterilized. A drill bit was inserted through a cone of filter paper (new for each sample), positioned so as to cover the chuck and prevent sawdust from entering it. We drilled through each wood block, on a line perpendicular to the face of the block that had contacted the colonized feeder strip, with a 1/8-in. diameter bit to generate a fine sawdust from which DNA could be isolated directly; no further grinding of the sawdust was needed to achieve good DNA extraction. Once a prepared drill bit was used to drill a wood sample, it was not reused until it had been recleaned and resterilized by the procedure described above. Fresh or lyophilized mycelia was simply ground to a fine powder with liquid nitrogen in a mortar and pestle for use in DNA extraction.

Ground or drilled material (100 to 200 μl) was transferred to a sterile microfuge tube. Then, 600 μl of the appropriate CTAB extraction buffer was added, and the sample was mixed to resuspend the powdered tissue in the buffer and incubated at 65°C for 2 h. The sample was extracted with 1 volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and a 1/10 volume of 10% (wt/vol) CTAB in 0.7 M NaCl was added. After mixing, the sample was incubated at 65°C for 1 h. Once again the sample was extracted with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol) and centrifuged as described above. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and extracted with 1 volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and the DNA was precipitated by the addition of 0.6 volume of ice-cold isopropanol. After incubation at −20°C for 30 min, the DNA precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed twice with ice-cold 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and dried. The pellet was resuspended in DNA storage buffer (6 mM Tris HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA; pH 7.5); 100 μl was used for DNA isolated from mycelia, and 50 μl was used for DNA isolated from wood samples. Incubation at 65°C speeded up resuspension of the DNA.

PCR amplification.

The ITS region was amplified by PCR from DNA isolated from pure cultures of each of the fungi listed in Table 1 and from wood blocks colonized by individual isolates of wood decay basidiomycetes or wood-inhabiting ascomycetes. Primers ITS1-F (CTT GGT CAT TTA GAG GAA GTA A), which is specific for the higher fungi (7), and ITS4 (TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC), the universal primer (20), were used together as a positive control for amplification, since they would be expected to amplify the ITS region from both ascomycetes and basidiomycetes. The primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B (CAG GAG ACT TGT ACA CGG TCC AG), which is specific for basidiomycetes (7), were used to specifically amplify the ITS region from only basidiomycetes.

Amplifications were performed in 50-μl reactions of PCR buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.3; 50 mM KCl; 0.001% [wt/vol] gelatin [Perkin-Elmer]), 200 μM concentrations of each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, and 200 nM concentrations of each of the appropriate primers, with nonacetylated bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma A-7906) at 250 ng/μl, total DNA isolated from a pure fungal culture or from a wood decay sample, 0.056 μM TaqStart antibody (Clontech), and 0.002 μM AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), i.e., 2 U per 50-μl reaction. The TaqStart antibody and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase were mixed together and preincubated prior to being added to the rest of the reaction components as per the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). Samples were overlaid with mineral oil and amplified in a MJ Research Thermocycler Model PTC-100. PCR reactions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min 25 s, 35 cycles of amplification, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min; each cycle of amplification consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 35 s, annealing for 55 s (at 55°C for reactions with ITS1-F and ITS4 and at 60°C for reactions with ITS1-F and ITS4-B), and extension at 72°C for 1 min.

Weakly positive or negative amplifications were reconfirmed as positive or negative by taking an aliquot of the PCR reaction and reamplifying it with the primer pair used in the original reaction. Aliquots of the PCR reaction using template DNA isolated from wood and the primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B were also reamplified to ensure ample amplicon DNA for multiple restriction digestions; this allowed us to identify the fungus present in the wood, even when there were few to no physical signs of decay.

PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels in 1× TBE (89 mM Tris-borate, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA) with ethidium bromide (EtBr) at 100 ng/ml in the gel and running buffer; DNA bands were visualized by the fluorescence of the intercalated EtBr under UV light and photographed.

Restriction digestion of PCR products.

PCR reaction products were digested directly without further purification with restriction endonucleases to obtain RFLPs; each sample was digested with AluI, HaeIII, TaqI, or RsaI in single-enzyme digests, as well as in a double digest with TaqI and HaeIII. Per each 20-μl restriction digest, 10 μl of unpurified, amplified PCR reaction was mixed with the appropriate restriction reaction buffer and 10 U of the appropriate enzyme and then incubated for 6 h at 37°C for the AluI, HaeIII, or RsaI digests or at 65°C for the TaqI digests.

Restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) and 2.5% (wt/vol) Sepharide Gel Matrix (Gibco-BRL) in 1× TAE (40 mM Tris acetate, 1 mM sodium EDTA) with EtBr at 100 ng/ml in the gel and running buffer. DNA bands were visualized by fluorescence under UV light and photographed.

RESULTS

DNA isolation from decayed wood.

CTAB extraction in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol followed by organic extractions and isopropanol precipitation of the DNA yielded DNA clean enough to amplify by PCR regardless of whether the starting material was fungal mycelia or decayed wood. The more decayed the wood, the more pigmented was the DNA-containing aqueous phase. Subsequent extractions with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol removed some of the pigmented by-products of wood decay, and more remained behind in the aqueous isopropanol phase upon precipitation of the DNA. However, substances inhibitory to PCR could carry through the purification procedure. For example, in preliminary experiments when DNA was isolated from replicate sets of drilled samples from highly decayed wood blocks (60% plus weight loss), the aqueous phase of samples in which the initial CTAB extraction had lasted overnight were much more strongly pigmented than those initially extracted for only 2 h, as in the standard protocol (see Materials and Methods); we would expect more by-products of wood decay to be extracted in an overnight versus a 2-h incubation. All of the 2-h CTAB-extracted DNA preparations were amplified by PCR; however, several of the overnight CTAB-extracted DNA preparations did not amplify, probably due to a higher concentration of compounds inhibitory to PCR remaining after purification.

Optimization of PCR assay conditions for detection of basidiomycetes.

The primers ITS1-F (higher fungus specific) and ITS4 (universal primer) amplified only one band (500 to 1,300 bp, depending on the fungal species) from DNA isolated from pure cultures of both ascomycetes and basidiomycetes via an ordinary PCR protocol, i.e., no hot start was needed. However, when we amplified the ITS region with the primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B (basidiomycete specific) from total DNA isolated from pure cultures, we obtained a number of minor amplification bands in both basidiomycetes and ascomycetes with the published amplification protocol that used an annealing temperature of 55°C (7). Although the main product (850 to 1,460 bp, depending on the fungal species) was not amplified from ascomycetes, a small band amplified very strongly in certain species of ascomycetes, e.g., a 210-bp band from Phialocephala fusca and a 330-bp band from Ophiostoma ulmi, in addition to the other minor bands. We tested a series of incrementally higher annealing temperatures and found that 60°C gave the cleanest results. The other minor bands were no longer produced in amplifications from basidiomycetes and ascomycetes, but the small strong band was still amplified from P. fusca and O. ulmi; the addition of a hot start to the PCR protocol eliminated this band. The primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B amplify a product from only basidiomycetes when a hot start and an annealing temperature of 60°C are used. Substitution of the TaqStart antibody system for the traditional hot start method produced the same amplification results. The TaqStart antibody system mimics a traditional hot start and yet is much simpler to use for processing large numbers of samples at one time and with less risk of introducing contaminating DNA.

In order to achieve specific amplification of DNA isolated from decayed wood, further adjustments to the PCR protocol were needed. Addition of nonacetylated BSA to PCR reactions, which is known to relieve inhibition of amplification by humic acids, fulvic acids, and organic components of soils and manure (13), allowed some amplification to occur from samples containing inhibitory wood decay by-products; but this amplification was often nonspecific. Additionally, a hot-start protocol, either the traditional method or the TaqStart antibody system, was required to obtain specific amplification of DNA isolated from wood decay samples.

We adopted as our standard PCR amplification conditions the inclusion of nonacetylated BSA at 250 ng/μl and the use of a hot start, the TaqStart antibody system for all reactions regardless of the tissue source of template DNA or primers used. These conditions are described in detail in Materials and Methods.

Fungal species survey.

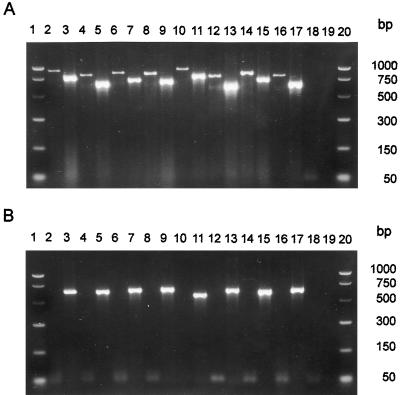

We surveyed a total of 43 species (60 isolates) of fungi. These included 16 species of basidiomycetes, 14 of which are wood decay fungi, both brown rot and white rot, and 27 species of ascomycetes, 25 of which are wood inhabiters (pathogens, endophytes, and saprophytes). For the initial survey (Table 1), PCR amplifications were performed using total DNA isolated from pure cultures of the fungi as the DNA template. Primers ITS1-F and ITS4 amplified the ITS region from all of these fungi, both ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, as expected. Primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B amplified the ITS region from only the basidiomycetes (Fig. 1, Table 1).

FIG. 1.

PCR amplification of nuclear rDNA from total DNA isolated from pure cultures of basidiomycetes (A) and ascomycetes (B). Electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) agarose in 1× TBE. The two outer lanes contain molecular weight markers. Inner even-numbered lanes contain samples amplified by the primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B, and the odd-numbered lanes contain samples amplified by primers ITS1-F and ITS4. (A) Lanes 2 to 9 contain brown-rot fungi, and lanes 10 to 17 contain white-rot fungi. Lanes 1 and 20, PCR markers (Promega); lanes 2 and 3, Coniophora puteana Fp-90099-Sp; lanes 4 and 5, Gloeophyllum trabeum Mad-617-R; lanes 6 and 7, Postia placenta Mad-698-R; lanes 8 and 9, Serpula lacrimans Harm-888-R; lanes 10 and 11, Lentinula edodes 117=1t(d); lanes 12 and 13, Resinicium bicolor ATCC 64897; lanes 14 and 15, Scytinostroma galactinum ATCC 64896; lanes 16 and 17, Trametes versicolor Fp-101664-Sp; lanes 18 and 19, no template DNA (i.e., negative controls). (B) Lanes 1 and 20, PCR markers (Promega); lanes 2 and 3, Aureobasidium pullulans ATCC 34621; lanes 4 and 5, Hormonema dematiodes; lanes 6 and 7, Pestalotiopsis sp.; lanes 8 and 9, Leucostoma kunzei; lanes 10 and 11, Scleroderris lagerbergii 1877; lanes 12 and 13, Sirococcus conigenus; lanes 14 and 15, Sphaeropsis sapinea B468; lanes 16 and 17, Xenomeris abietis; lanes 18 and 19, no template DNA (i.e., negative controls).

Detection of decay fungi in wood.

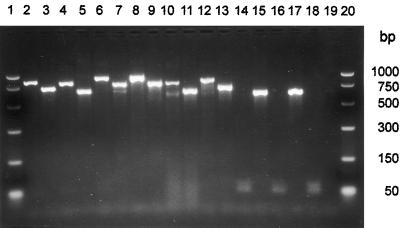

The next step was to see if we could detect fungi in spruce wood by PCR amplification (Fig. 2, Table 2) using total DNA isolated from colonized wood blocks as the DNA template. We surveyed 30 species of fungi colonizing spruce wood. Two replicate jars were set up and inoculated, as described in Materials and Methods, for each of the wood-decaying basidiomycete species listed in Table 1 (excluding Fomitopsis pinicola and Trichaptum abietinum) and for each of the following wood-inhabiting ascomycetes: Ceratocystis pilifera ATCC 60758, Ophiostoma ulmi ATCC 32439, Phialocephala fusca ATCC 62326, Phialophora mutabilis ATCC 42792, Trichoderma reesei ATCC 26921, Trichoderma viride ATCC 32630, Aureobasidium pullulans, Hormonema dematiodes, Pestalotiopsis sp., and Xenomeris abietis. Wood blocks cut from radial sections of spruce were added to the colonized feeder strips and harvested after 8 months of colonization.

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification of nuclear rDNA from total DNA isolated from wood blocks colonized by wood decay fungi or endophytes. Electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) agarose in 1× TBE. The two outer lanes contain molecular weight markers. Inner even-numbered lanes contain samples amplified by the primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B, and the odd-numbered lanes contain samples amplified by primers ITS1-F and ITS4. Lanes 2 to 7, brown-rot basidiomycetes; lanes 8 to 13, white-rot basidiomycetes; lanes 14 to 17, endophytic ascomycetes. Lanes 1 and 20, PCR markers (Promega); lanes 2 and 3, Postia placenta Mad-698-R; lanes 4 and 5, Gloeophyllum trabeum Mad-617-R; lanes 6 and 7, Leucogyrophana pinastri; lanes 8 and 9, Lentinula edodes 117=1t(d); lanes 10 and 11, Trametes versicolor; lanes 12 and 13, Scytinostroma galactinum ATCC 64896; lanes 14 and 15, Hormonema dematiodes; lanes 16 and 17, Pestalotiopsis sp.; lanes 18 and 19, no template DNA (i.e., negative controls).

TABLE 2.

Wood decay and detection of fungal species in wood blocks after 8 months of colonization

| Species | Isolate | Mean % wt loss of wood ± SDa | PCR amplificationb with primer pair:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1-F–ITS4 | ITS1-F–ITS4-B | |||

| Uninoculated control wood | 0.1 ± 0.3 | ++ | −− | |

| Brown-rot basidiomycetes | ||||

| Coniophora puteana | Fp-90099-Sp | 0.1 ± 0.3 | ++ | ++ |

| Postia placenta | Mad-698-R | 65.5 ± 1.2 | ++ | ++ |

| Postia placenta | 65.8 ± 1.4 | ++ | ++ | |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | 67.3 ± 3.3 | ++ | ++ | |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | Mad-617-R | 69.6 ± 1.8 | ++ | ++ |

| Gloeophyllum sepiarum | 10-BS2-2 | 68.1 ± 0.9 | ++ | ++ |

| Leucogyrophana pinastri | 68.1 ± 4.8 | ++ | ++ | |

| Serpula lacrimans | Harm-888-R | 67.5 ± 1.9 | ++ | ++ |

| White-rot basidiomycetes | ||||

| Lentinula edodes | 117=1t(d) | 3.0 ± 1.7 | ++ | ++ |

| Trametes versicolor | 35.1 ± 13.6 | ++ | ++ | |

| Trametes versicolor | Fp-101664-Sp | 0.0 ± 0.1 | ++ | ++ |

| Irpex lacteus | KTS 003 | 40.1 ± 12.1 | ++ | ++ |

| Resinicium bicolor | HHB-8850-sp | 10.4 ± 0.9 | ++ | ++ |

| Resinicium bicolor | ATCC 44175 | 3.7 ± 3.6 | ++ | ++ |

| Resinicium bicolor | ATCC 64897 | 12.1 ± 5.7 | ++ | ++ |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | MB-1880-sp | −0.8 ± 0.5 | ++ | ++ |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | ATCC 64896 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | ++ | ++ |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | ATCC 44178 | −0.2 ± 0.7 | ++ | ++ |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 9.9 ± 11.8 | ++ | ++ | |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | ATCC 24725 | 14.2 ± 5.7 | ++ | ++ |

| Wood-inhabiting ascomycetes | ||||

| Phialophora mutabilis | ATCC 42792 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | ++ | −− |

| Trichoderma reesei | ATCC 26921 | −0.2 ± 0.4 | ++ | −− |

| Trichoderma viride | ATCC 32630 | −0.1 ± 0.1 | ++ | −− |

| Hormonema dematiodes | 0.4 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− | |

| Pestolotiopsis sp. | 0.6 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− | |

| Xenomeris abietis | 0.5 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− | |

| Aureobasidium pullulans | ATCC 34621 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− |

| Phialocephala fusca | ATCC 62326 | −0.2 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− |

| Ceratocystis pilifera | ATCC 60758 | 2.7 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− |

| Ophiostoma ulmi | ATCC 32439 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | ++ | −− |

Mean of two replicate spruce wood blocks.

Primer ITS1-F is specific for higher fungi, primer ITS4 is a universal primer, and primer ITS4-B is specific for basidiomycetes. Each plus or minus sign represents the amplification results for an individual wood block.

Wood blocks with ascomycetes had a negligible weight loss, the majority by less than 0.5%, and seemed unchanged in appearance. The weight losses of wood blocks with white-rot fungi were very variable and ranged from negligible to approximately 40%; there was little to no change in the color of the wood, but some of the more decayed ones, e.g., replicate blocks colonized by one of the isolates of Trametes versicolor had become stringy in texture. Wood blocks with brown-rot fungi had decayed the most and were very brown in color; all but one isolate had caused a weight loss of 65 to 70%, the exception being Coniophora puteana isolate Fp-90099-Sp. In all of the wood block treatments, we had weight losses ranging between 0 and 70%. Primers ITS1-F and ITS4 amplified DNA from all of the samples, including the uninoculated control blocks. Primers ITS-1F and ITS4-B amplified DNA from wood blocks that had been inoculated with only basidiomycetes, i.e., the brown-rot isolates and white-rot isolates; ITS1-F and ITS4-B did not amplify DNA from uninoculated control blocks nor from any of the wood blocks inoculated with wood-inhabiting ascomycetes. The unknown contaminant fungus detected in the uninoculated control blocks is probably an ascomycete, since no amplification occurs when the basidiomycete-specific primer ITS4-B is present in the PCR reaction; we suspect it may be a mold known to survive in wood upon repeated autoclaving. We could reliably detect the presence of wood decay fungi by PCR with the primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B in spruce blocks exhibiting a range of degradation states.

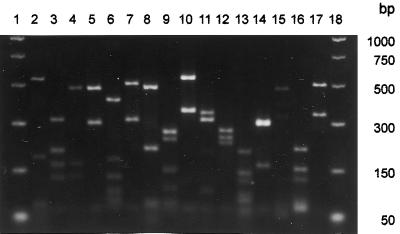

Fungal identification.

In order to identify the basidiomycetes detected by PCR, we generated RFLPs of the ITS region, the product amplified by primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B, by restriction digestion with RsaI, AluI, HaeIII, TaqI, or TaqI-HaeIII. RsaI was not very useful because it did not cut the amplicon from 10 out of the 14 species of wood-decaying basidiomycetes tested nor that from the ectomycorrhizal Pisolithus tinctorius and the soil-borne Rhizoctonia solani, which do not decay wood. The other restriction endonucleases generated more fragments per digest, so that each basidiomycete could be identified to the species level from the combination of its RFLP profiles (Fig. 3, Table 3). The majority of RFLP profiles generated for any given enzyme were unique for each fungal species. The two Gloeophyllum species, however, had identical AluI RFLP profiles and identical HaeIII RFLP profiles; G. trabeum and G. sepiarum could be separated by their TaqI RFLP profiles and their TaqI-HaeIII RFLP profiles. Different isolates of a given fungal species usually had identical RFLP profiles for a particular restriction endonuclease; this was true for each enzyme for isolates of G. trabeum, Irpex lacteus, Postia placenta, Resinicium bicolor, and Serpula lacrimans. For other fungi, some enzymes would generate RFLP profiles which separated isolates at the species level and other enzymes would generate RFLP profiles which separated isolates at the subspecies level. For example, isolates of Scytinostroma galactinum had identical AluI RFLP profiles and identical HaeIII RFLP profiles, but the isolates could be distinguished from each other by their respective TaqI RFLP profiles and TaqI HaeIII RFLP profiles.

FIG. 3.

TaqI restriction digests of the PCR product amplified by the primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B from DNA isolated from pure cultures of basidiomycetes. Electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) Sepharide Gel Matrix (Gibco-BRL) in 1× TAE. The two outer lanes contain molecular weight markers. Each inner lane contains a different fungal species; lanes 2 to 8 contain brown-rot fungi, and lanes 9 to 15 contain white-rot fungi. Lanes 1 and 18, PCR markers (Promega); lane 2, Coniophora puteana Fp-90099-Sp; lane 3, Fomitopsis pinicola K8sp; lane 4, Gloeophyllum sepiarum 10-BS2-2; lane 5, Gloeophyllum trabeum Mad-617-R; lane 6, Leucogyrophana pinastri; lane 7, Postia placenta Mad-698-R; lane 8, Serpula lacrimans Harm-888-R; lane 9, Irpex lacteus KTS 003; lane 10, Lentinula edodes 117=1t(d); lane 11, Phanerochaete chrysosporium ATCC 24725; lane 12, Resinicium bicolor ATCC 64897; lane 13, Scytinostroma galactinum ATCC 64896; lane 14, Trametes versicolor Fp-101664-Sp; lane 15, Trichaptum abietinum 1247 MJL; lane 16, Pisolithus tinctorium ATCC 38054, an ectomycorrhiza; lane 17, Rhizoctonia solani 1AP, a pathogen of herbaceous plants.

TABLE 3.

RFLPs of ITS regions for basidiomycetes

| Species and isolate(s)a | RFLPs (bp) obtained with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AluI | HaeIII | TaqI | TaqI-HaeIII | Uncut ampliconb | ||

| Brown-rot basidiomycetes | ||||||

| Coniophora puteana | 500 | 470 | 530 | 247 | ||

| Fp-90099-Sp | 187 | 242 | 185 | 197 | ||

| 170 | 114 | 71 | 182 | |||

| 91 | 59 | 69 | ||||

| 23 | 59 | |||||

| 41 | ||||||

| 23 | ||||||

| Total | 948 | 908 | 786 | 813 | 970 | |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | 380 | 545 | 310 | 248 | ||

| K8Sp | 200 | 127 | 203 | 165 | ||

| 90 | 98 | 165 | 107c | |||

| 52 | 62 | 130 | 62 | |||

| Total | 722 | 832 | 870 | 796 | 930 | |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | 435 | 670 | 500 | 420 | ||

| This lab | 155 | 107 | 318 | 215 | ||

| Mad-617-R | 105 | 72 | 72 | 107 | ||

| ATCC 11539 | 86 | 72 | ||||

| Total | 781 | 849 | 890 | 814 | 890 | |

| Gloeophyllum sepiarum | 435 | 670 | 500 | 420 | ||

| 10-BS2-2 | 155 | 107 | 170 | 140 | ||

| 105 | 72 | 140 | 107 | |||

| 86 | 72 | 72 | ||||

| Total | 781 | 849 | 882 | 739 | 890 | |

| Leucogyrophana pinastri | 580 | 320 | 400 | 245 | ||

| This lab | 300 | 245 | 180 | 127 | ||

| 100 | 170 | 127 | 95 | |||

| 140 | 95 | 72 | ||||

| 63 | 78 | 63 | ||||

| 55 | 63 | 37 | ||||

| Total | 980 | 993 | 943 | 639 | 1,050 | |

| Postia placenta | 448 | 610 | 530 | 445 | ||

| This lab | 240 | 110d | 335 | 115d | ||

| Mad-698-R | 100 | 72 | 72 | 72 | ||

| Total | 788 | 902 | 937 | 747 | 930 | |

| Serpula lacrimans | 810 | 800 | 485 | 485 | ||

| Harm-888-R | 100 | 108 | 215 | 215 | ||

| ATCC 36335 | 81 | 77 | ||||

| 68 | 68 | |||||

| 50 | 39 | |||||

| Total | 910 | 908 | 899 | 884 | 930 | |

| White-rot basidiomycetes | ||||||

| Irpex lacteus | ||||||

| KTS 003 | 500 | 425 | 270 | 245 | ||

| ATCC 60993 | 105 | 345 | 245 | 140 | ||

| 93 | 105 | 150 | 108 | |||

| 61 | 108 | 77 | ||||

| 77 | 61 | |||||

| 61 | ||||||

| Total | 698 | 936 | 911 | 631 | 960 | |

| Lentinula edodes | 515 | 860 | 540 | 540 | ||

| 117=lt(d) | 235 | 102 | 355 | 255 | ||

| 105 | 50 | 60 | 102 | |||

| 60 | ||||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 515 | 705 | 385 | 385 | ||

| This lab | 165 | 98 | 315 | 220 | ||

| 94 | 50 | 98 | 98 | |||

| 65 | 65 | |||||

| Total | 774 | 853 | 863 | 768 | 850 | |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 515 | 705 | 330 | 330 | ||

| ATCC 24725 | 165 | 98 | 300 | 208 | ||

| 94 | 50 | 98 | 98 | |||

| 59 | 59 | |||||

| 32 | 32 | |||||

| Total | 774 | 853 | 819 | 727 | 850 | |

| Resinicium bicolor | 380 | 800 | 270 | 270 | |

| HHB-8850-sp | 150 | 50 | 245 | 245 | |

| ATCC 44175 | 98 | 215 | 215 | ||

| ATCC 64897 | 69 | 60 | 60 | ||

| Total | 697 | 850 | 790 | 790 | 850 |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | 595 | 540 | 315 | 315 | |

| MB-1880-sp | 204 | 268 | 200 | 137 | |

| 94 | 60 | 164 | 116 | ||

| 75 | 75 | ||||

| 60 | 60 | ||||

| 50 | |||||

| Total | 893 | 868 | 814 | 753 | 930 |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | 595 | 540 | 220 | 220 | |

| ATCC 44178 | 204 | 268 | 200 | 137 | |

| 94 | 60 | 116 | 116 | ||

| 91 | 91 | ||||

| 75 | 75 | ||||

| 60 | 60 | ||||

| 50 | |||||

| Total | 893 | 868 | 762 | 749 | 930 |

| Scytinostroma galactinum | 595 | 540 | 200 | 137 | |

| ATCC 64896 | 204 | 268 | 137 | 116 | |

| 94 | 60 | 116 | 91 | ||

| 91 | 75 | ||||

| 75 | 60 | ||||

| 60 | 50 | ||||

| Total | 893 | 868 | 679 | 529 | 930 |

| Trametes versicolor | 360 | 300d | 320 | 260 | |

| This lab | 146 | 105 | 172 | 135 | |

| 93 | 70 | 74 | 108 | ||

| 74 | 74 | ||||

| 58 | 50 | ||||

| Total | 731 | 775 | 566 | 627 | 910 |

| Trametes versicolor | 360 | 300d | 320 | 255 | |

| Fp-101664-Sp | 146 | 210 | 172 | 205 | |

| 93 | 70 | 74 | 135 | ||

| 74 | 113 | ||||

| 58 | 74 | ||||

| 50 | |||||

| Total | 731 | 880 | 566 | 832 | 910 |

| Trichaptum abietinum | 405 | 900 | 470 | 335 | |

| 1247 MJL | 365 | 310 | 335 | 145 | |

| 215 | 145 | 53 | 62 | ||

| 155 | 53 | ||||

| 50 | |||||

| Total | 1,190 | 1,408 | 858 | 542 | 1,460 |

| Ectomycorrhiza | |||||

| Pisolithus tinctorius | 435 | 605 | 208 | 208 | |

| ATCC 38054 | 182 | 170 | 150 | 127 | |

| 165 | 59 | 127 | 100 | ||

| 87 | 76 | 69 | |||

| 59 | 59 | ||||

| 23 | 44 | ||||

| 23 | |||||

| Total | 869 | 834 | 643 | 630 | 890 |

| Soil-borne pathogen of herbaceous plants | |||||

| Rhizoctonia solani | 415 | 620 | 500 | 335 | |

| 1AP | 245 | 260 | 335 | 260 | |

| 98 | 59 | 242 | |||

| 83 | 59 | ||||

| Total | 841 | 880 | 894 | 896 | 970 |

All isolates of a species which have identical RFLP profiles per restriction endonuclease for all enzymes are listed together. If different isolates of a species have different RFLP profiles for at least one of the restriction endonucleases, then those isolates are listed separately.

Amplicon of the ITS region amplified by primers ITS1-F (specific for higher fungi) and ITS4-B (specific for basidiomycetes).

This fragment is a triplet, as reflected in the fragment total.

This fragment is a doublet, as reflected in the fragment total.

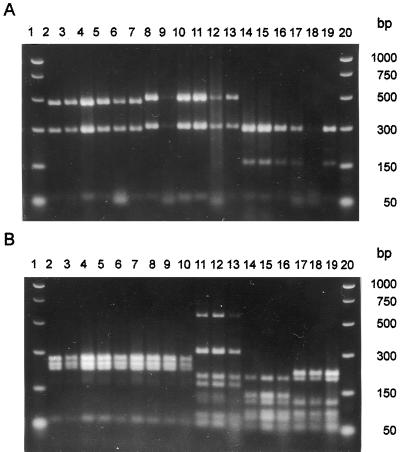

The identities of basidiomycetes detected by PCR from colonized spruce wood blocks were confirmed by comparing the RFLPs of the product amplified by primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B from DNA isolated from wood blocks to that from the respective pure culture of the fungus. Figure 4 demonstrates that the TaqI RFLP profile for any one wood block matches that of the TaqI digest of the amplicon obtained from DNA from a pure culture of that particular fungal isolate; analogous results were also obtained with AluI, HaeIII, and TaqI-HaeIII digestions.

FIG. 4.

TaqI restriction digests of the PCR product amplified by the primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B from DNA isolated from wood decay basidiomycetes. Electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) Sepharide Gel Matrix (Gibco-BRL) in 1× TAE. The two outer lanes contain molecular weight markers. Each group of three inner lanes represents the TaqI digests for one fungal isolate amplified from DNA isolated from each of two different wood blocks and a pure culture from left to right, respectively. (A) Lanes 1 and 20, PCR markers (Promega); lanes 2 to 4, Gloeophyllum trabeum; lanes 5 to 7, Gloeophyllum trabeum, Mad-617-R; lanes 8 to 10, Postia placenta; lanes 11 to 13, Postia placenta Mad-698-R; lanes 14 to 16, Trametes versicolor; lanes 17 to 19, Trametes versicolor Fp-101664-Sp. (B) Lanes 1 and 20, PCR markers (Promega); lanes 2 to 4, Resinicium bicolor; lanes 5 to 7, Resinicium bicolor ATCC 44175; lanes 8 to 10, Resinicium bicolor ATCC 64897; lanes 11 to 13, Scytinostroma galactinum; lanes 14 to 16, Scytinostroma galactinum ATCC 64896; lanes 17 to 19, Scytinostroma galactinum ATCC 44178.

Time course studies.

In order to determine how early we could detect wood decay fungi in wood, we ran two time course studies with the brown-rot fungi Postia placenta isolate Mad-698-R and Gloeophyllum trabeum isolate Mad-617-R. Soil block jars were set up and inoculated as described in Materials and Methods. For each time course experiment, three replicate jars were inoculated for each combination of time and fungal isolate, as well as for a time-zero uninoculated control and an 8-month-incubated uninoculated control. The first time course used wood blocks cut from radial sections of spruce sapwood, and the second time course used wood blocks cut from longitudinal sections. Wood blocks were harvested after 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks and after 4 and 8 months of colonization.

Wood decay progressed more rapidly in wood blocks cut from radial versus longitudinal sections of spruce sapwood, as evidenced by the change in percent weight loss of the wood over time (Table 4). A few samples from the first time course and several from the second time course amplified weakly or not at all with primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B; the positive or negative nature of each was confirmed by reamplification of an aliquot of the original PCR reaction. Gloeophyllum trabeum and P. placenta, both brown-rot basidiomycetes, could be detected in wood by PCR amplification using primers ITS1-F (higher fungus specific) and ITS4-B (basidiomycete specific) after 1 week of colonization, the shortest colonization period used in the study. G. trabeum was detected in all replicates of all samples from all colonization times in both cuts of wood and could be detected at a 0.3% mean weight loss of the wood. P. placenta was detected in all of the samples from all of the wood blocks cut from radial sections but not in all of those cut from longitudinal sections. After 1 week of colonization (0.5% mean weight loss), P. placenta could be detected in only one of three of the wood blocks cut from longitudinal sections, but by 2 week (3.0% mean weight loss), it could be detected in three of three blocks; detection was also variable at later time points.

TABLE 4.

Time courses of wood decay and detection of brown-rot basidiomycetes

| Expt and species | Time | Mean % wt loss of wood ± SDa | PCR amplificationb with primer pair:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1-F–ITS4 | ITS1-F–ITS4-B | |||

| Expt 1 (wood blocks cut from radial sections of spruce) | ||||

| Uninoculated control | 0 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | +−− | −−− |

| Uninoculated control | 8 mo | 0.4 ± 0.3 | +++ | −−− |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum Mad-617-R | 1 wk | 0.7 ± 1.6 | +++ | +++ |

| 2 wk | 15.5 ± 4.2 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 wk | 34.1 ± 2.0 | +++ | +++ | |

| 8 wk | 64.7 ± 1.9 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 mo | 70.1 ± 1.0 | +++ | +++ | |

| 8 mo | 69.3 ± 2.3 | +++ | +++ | |

| Postia placenta Mad-698-R | 1 wk | 2.6 ± 0.4 | +++ | +++ |

| 2 wk | 11.7 ± 2.8 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 wk | 44.2 ± 9.7 | +++ | +++ | |

| 8 wk | 61.9 ± 0.8 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 mo | 66.3 ± 0.5 | +++ | +++ | |

| 8 mo | 67.6 ± 0.6 | +++ | +++ | |

| Expt 2 (wood blocks cut from longitudinal sections of spruce) | ||||

| Uninoculated control | 0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | −−− | −−− |

| Uninoculated control | 8 mo | 0.03 ± 0.1 | +++ | −−− |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum Mad-617-R | 1 wk | 0.3 ± 0.4 | +++ | +++ |

| 2 wk | 1.9 ± 1.2 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 wk | 13.5 ± 2.1 | +++ | +++ | |

| 8 wk | 34.5 ± 2.7 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 mo | 63.7 ± 8.0 | +−+ | +−+ | |

| 8 mo | 70.7 ± 6.5 | +++ | +++ | |

| Postia placenta Mad-698-R | 1 wk | 0.5 ± 0.4 | +++ | −−+ |

| 2 wk | 3.0 ± 0.7 | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 wk | 14.8 ± 3.1 | +++ | +−+ | |

| 8 wk | 38.7 ± 8.1 | +++ | ++− | |

| 4 mo | 59.8 ± 3.7 | +++ | ++− | |

| 8 mo | 60.7 ± 6.1 | +++ | +++ | |

Mean of three replicate spruce wood blocks.

Primer ITS1-F is specific for higher fungi, primer ITS4 is a universal primer, and primer ITS4-B is specific for basidiomycetes. Each plus or minus sign represents the amplification results for an individual wood block.

DISCUSSION

Although our procedure for DNA isolation and purification may be longer than desired to routinely screen large numbers of wood samples, we thought it best to begin the process of assay development with a method highly likely to yield DNA amplifiable by PCR, since many by-products of wood decay, if present at too high a concentration in the reaction, would inhibit amplification of the DNA template. When setting up PCR reactions with wood samples that have very low DNA concentrations, diluting out the inhibitors could also mean diluting out the DNA past the threshhold of detection. So it is better to start with a DNA preparation from which one has removed as much of the inhibitory materials as possible. With the minipreparation procedure described in the Materials and Methods, one person can drill and isolate DNA from 24 wood samples in one work day, observing all the necessary precautions both during drilling of the wood and DNA isolation to prevent any cross-contamination of samples.

Avoiding cross-contamination of samples is critical. Early on, we found that preparation of the wood for DNA isolation is the step at which cross-contamination can most easily occur due to the inherent properties of sawdust. For example, a Wiley mill is not a good choice for grinding samples for PCR work. It is very difficult to clean out all of the crevices in which sawdust can be caught and, even after disassembly, careful brushing out of remaining debris, reassembly, and running through several volumes of clean fungus-free wood, and recleaning all the surfaces and crevices with a cotton swab, there is still carryover from one wood decay sample to the next; furthermore, this whole process takes an unacceptably long time. A drill is a much better choice. A rechargeable cordless drill has fewer crevices and surfaces to collect dirt and debris and can be more easily cleaned than a Wiley mill. Drill bits are easy to clean and flame sterilize and are relatively inexpensive, so one can have many of them ready to use. One can prepare wood samples for DNA isolation very rapidly with a drill and at far less risk of sample cross-contamination via sawdust. It is also important to wear gloves and to keep the work area clean, i.e., it is advisable to swab both your gloves and work surface with 70% ethanol to collect any bits of sawdust between drilling each sample. By observing these precautions, as described in detail in Materials and Methods, we have not detected any cross-contamination in samples prepared by drilling and so have adopted this procedure for routine use.

We have developed a DNA-based method to reliably detect brown-rot and white-rot fungi in spruce wood using the published (7) primers ITS1-F (higher fungus specific) and ITS4-B (basidiomycete specific) to amplify the ITS region. We have optimized the reaction conditions for PCR with these primers for template DNA isolated from both pure culture and spruce wood and can detect brown-rot and white-rot fungi from incipient through advanced stages of wood decay. Some late-stage brown-rot samples appeared to have weaker amplification signals than less-decayed samples (data not shown). This could be due to carryover of by-products of wood decay inhibitory to PCR, degradation of DNA in the late stages of wood decay, or a combination of the two. Currently, our assay is only qualitative; more work needs to be done to make it quantitative. The ability to detect decay fungi in other species of wood, preservative-treated wood, and wood composites should also be examined. The differing chemical compositions of both the undecayed and decayed forms of these substrates could introduce new kinds of PCR-inhibitory compounds that may or may not be eliminated or neutralized by our current methodology.

While the primer pair ITS1-F and ITS4-B will detect only basidiomycetes, it will detect any basidiomycete present. For example, if the wood sample were taken from a root, there might be mycorrhizae present that would also be detected. Identity of the basidiomycete present can be achieved by restriction digestion of the PCR product. We could distinguish wood decay basidiomycetes at the species level by comparing the RFLP profiles obtained by TaqI digestion of the ITS region amplified by ITS1-F and ITS4-B or by comparing the combination of different RFLP profiles generated from this amplicon by a number of different restriction endonucleases. Gardes et al. (8) identified 20 taxa of ectomycorrhizal fungi to the species or species group level from the RFLP profiles of the ITS region amplified by these primers using DNA from mycorrhizae and basidiocarps. Using this method to identify all of their samples, these researchers were able to create a snapshot of the community structure of these ectomycorrhizal fungi both above and below ground in natural stands of Pinus muricata.

Although PCR amplification followed by digestion with restriction endonucleases worked fine for samples containing only one fungus, field samples could pose a greater challenge and contain more than one species of wood decay basidiomycete. As the number of different wood decay basidiomycetes contained in a wood sample increases, it would become correspondingly more difficult to identify them all to the species level based on RFLPs. For a more specific and one-step assay for a particular basidiomycete species, it would be better to develop a species-specific PCR primer based on a suitably informative area of the DNA sequence of the ITS region of that species. This concept could be extended to develop an assay in which a number of different species could be identified concurrently in one PCR reaction. Recently, Schmidt and Moreth (16) developed species-specific primers based on the DNA sequence of ITSII for the indoor rot fungi Serpula lacrimans and Serpula himantioides. We are currently designing species-specific primers for other brown-rot fungi.

We are also looking at DNA sequences of enzymes thought to be involved in wood decay to see if it is possible to design primers that would specifically detect only wood decay basidiomycetes and not other basidiomycetes. It would be useful to be able to detect several wood decay species concurrently in samples where other non-wood-decaying species are likely to occur, e.g., tree roots and forest soils. However, for the purposes of detecting wood decay fungi in branches, tree trunks, harvested timber, or wood in service, where the probability of nondecay basidiomycetes colonizing the internal wood is very low, the assay we developed using the published primers ITS1-F and ITS4-B is potentially very useful. The very lack of specificity which limits the direct identification of the fungus to species can be an advantage in developing a broad-based assay. Previous workers have used PCR amplification in conjunction with RFLP analysis to identify wood decay fungi (15, 23), but their work has focused on identification of the fungi in culture or fungal material present on the wood versus the direct identification of early stages of decay within the wood. By focusing our efforts on the development of an assay that can sample directly from wood, we hope to eventually eliminate the need to culture the decay fungi as a first step, so that detection would not be limited by the ability to culture them from a specific wood sample. Although our current PCR method is broad based for basidiomycetes, if used in combination with species-specific primers, one could detect a particular wood decay species of interest and also be alerted to the presence of other basidiomycetes, i.e., other potential decay fungi, in the wood sample.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant number 95-34158-1347 from the USDA and by the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station.

Footnotes

This work is contribution no. 2407 from the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station, Orono, Maine.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society for Testing and Materials. 1994 annual book of ASTM standards, section 4. 04.10. Philadelphia, Pa: American Society for Testing and Materials; 1994. Standard method of accelerated laboratory test of natural decay resistance of woods (D 1413-76) pp. 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonello P, Bruns T D, Gardes M. Genetic structure of a natural population of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus pungens. New Phytol. 1998;138:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clausen C A. Immunological detection of wood decay fungi—an overview of techniques developed from 1986 to the present. Int Biodeterioration Biodegrad. 1997;39:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clausen C A, Green III F, Highley T L. Early detection of brown-rot decay in southern yellow pine using immunodiagnostic procedures. Wood Sci Technol. 1991;26:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erland S, Henrion B, Martin F, Glover L A, Alexander I J. Identification of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Tylospora fibrillosa Donk by RFLP analysis of the PCR-amplified ITS and IGS regions of ribosomal DNA. New Phytol. 1994;126:525–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbelotto M, Ratcliff A, Bruns T D, Cobb F W, Ostrosina W J. Use of taxon-specific competitive-priming PCR to study host specificity, hybridization, and intergroup gene flow in intersterility groups of Heterobasidion annosum. Phytopathology. 1996;86:543–551. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardes M, Bruns T D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol Ecol. 1993;2:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardes M, Bruns T D. Community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi in Pinus muricata forest: above- and below-ground views. Can J Bot. 1996;74:1572–1583. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardes M, White T J, Fortin J A, Bruns T D, Taylor J W. Identification of indigenous and introduced symbiotic fungi in ectomycorrhizae by amplification of nuclear and mitochondrial ribosomal DNA. Can J Bot. 1991;69:180–190. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henrion B, Le Tacon F, Martin F. Rapid identification of genetic variation of ectomycorrhizal fungi by amplification of ribosomal RNA genes. New Phytol. 1992;122:289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1992.tb04233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jellison J, Goodell B. Immunological detection of decay in wood. Wood Sci Technol. 1988;22:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jellison J, Goodell B. Inhibitory effects of undecayed wood and the detection of Postia placenta using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Wood Sci Technol. 1989;28:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreader C A. Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin of T4 gene 32 protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullis K B, Faloona F A. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt O, Moreth U. Genetic studies on house rot fungi and a rapid diagnosis. Holz Roh Werkstoff. 1998;56:421–425. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt O, Moreth U. Species-specific PCR primers in the rDNA-ITS region as a diagnostic tool for Serpula lacrymans. Mycol Res. 2000;14:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze S, Bahnweg G, Moller E M, Sandermann H., Jr Identification of the genus Armillaria by specific amplification of an rDNA-ITS fragment and evaluation of genetic variation within A. ostoyae by rDNA-RFLP and RAPD analysis. Eur J For Pathol. 1997;27:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulze S, Bahnweg G, Tesche M, Sandermann H., Jr Identification of European Armillaria species by restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms of ribosomal DNA. Eur J For Pathol. 1995;25:214–223. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor B H, Manhart J R, Amasino R M. Isolation and characterization of plant DNAs. In: Glick B R, Thompson J E, editors. Methods in plant molecular biology and biotechnology. Ann Arbor, Mich: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White T J, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidmand J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zabel R A, Morrell J J. Wood microbiology: decay and its prevention. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaremski A, Ducousso M, Prin Y, Fouquet D. Characterization of tropical wood decaying fungi by RFLP analysis of PCR amplified rDNA. International Research Group on Wood Preservation series, document 98-10251. Stockholm, Sweden: International Research Group on Wood Preservation; 1998. [Google Scholar]