Abstract

Context

Thyroid hormones are associated with birth weight in singleton pregnancy. Twin pregnancies need more thyroid hormones to maintain the normal growth and development of the fetuses compared with single pregnancy.

Objective

We aimed to investigate the association of thyroid hormones and birth weight in twins.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study in a Chinese population. Pregnant women who received regular antenatal health care and delivered live-born twins from 2014 to 2019 were included (n = 1626). Linear mixed model with restricted cubic splines and logistic regression models were used to estimate the association of thyroid hormones with birth weight and birth weight discordance in twins.

Results

We observed that both thyrotropin (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) were not associated with birth weight in twins overall, while when stratifying on fetal sex or chorionicity, there were nonlinear association between FT4 levels and birth weight in boys (Pnonlinear < .001) and in dichorionic (DC) twins (Pnonlinear = 0.03). Women with levels of FT4 lower than the 10th percentile had a higher risk of birth weight discordance in their offspring than women with normal FT4 levels (range, 2.5 to 97.5 percentiles) (odds ratio = 1.58; 95% CI, 1.05-2.33).

Conclusion

Our study suggests there was an association of FT4, but not TSH, with birth weight and birth weight discordance varied by sex and chorionicity. These findings could have implications for obstetricians to be aware of the importance of FT4 levels in preventing birth weight discordance in twin pregnancy.

Keywords: thyroid function, twin pregnancy, birth weight, birth weight discordance

Thyroid hormone is essential to the normal growth and development of the fetus, especially the development of nervous system (1, 2). It is indicated that primary thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of negative pregnancy outcomes (3-5) and various diseases in the offspring (6, 7). Previous studies have shown that underactive maternal thyroid dysfunction has a continuous influence on birth weight (8, 9). A recent meta-analysis indicated that increased free thyroxine (FT4) concentration was associated with lower birth weight (–21 g) and increased risk of small gestational age in singletons (6). A series of studies have confirmed an association between maternal thyroid dysfunction and birth weight in single pregnancy (10-12). There has been, however, a lack of researches in twin pregnancy. In addition, birth weight discordance is common (13) and is related to an increased risk of intrauterine death in twins compared with singletons (14). Studies have shown that human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels among women with twins were twice as high as in singleton pregnancy at 11 to 13 weeks of gestation (15, 16). The changes in thyroid hormone in twin pregnancy were also different from that in singleton pregnancy (17, 18). Consequently, the prevalence of thyroid dysfunction is also more common among twin pregnancy, as hCG acts as a thyrotropin (TSH)-like agonist on the thyroid gland in the context of pregnancy (19). In this study we aimed to examine the associations of thyroid function with birth weight and risk of birth weight discordance in twin pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Study Population

This was a hospital-based, retrospective cohort study. Women delivering live-born twins between January 2014 to December 2019 were included in the study (n = 2165). Women with unknown gestational age (n = 17), with history of thyroid diseases or prior use of thyroid-interfering drugs (n = 118), without thyroid function screening during pregnancy (n = 222), with endocrine system diseases before pregnancy (n = 54), with diagnosis of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (n = 31), or pregnancy achieved by assisted reproductive techniques (n = 97) were excluded from the study. A total of 1626 women with 3252 newborns were included in the final analysis.

A maternal peripheral blood sample was collected at the first antenatal visit and was centrifuged (10 minutes with rethawing cycles at 3000 rpm) to obtain serum. Serum FT4, TSH, and thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) (Fitzgerald Industries International catalog No. 70R-9760, RRID:AB_11200097) were measured by fluorescence and chemiluminescence immunoassays using ADVIA Centaur instruments and kits (Siemens) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Measurements for TPOAb were performed in a subset of 1529 women, and considered elevated if levels were 60 U/mL or greater according to the manufacturer-defined cutoff.

Birth weight was extracted from the electronic medical records. Birth weight discordance is defined with the larger twin as the standard of growth and is calculated by the following equation: (larger estimated or actual weight – smaller estimated or actual weight)/larger estimate or actual weight. Birth weight discordance was defined as a difference in birth weight of more than 20% in this study according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG recommendations (20).

The following variables were collected by retrospective chart review: residence of origin (Shanghai, others), parity (nulliparous or parous), ethnicity (majority [Han], minority), pregnancy weight, height, chorionicity (dichorionic [DC], monochorionic [MC]), fetal sex (boy, girl), and pregnancy complications (yes, no). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight (kg) divided by square of height (meters), and then classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24), overweight (BMI 24-< 28), or obesity (BMI ≥ 28).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted for demographic information. Mean (SD) was used for continuous variables, and count (percentage) was used for categorical variables. Concentrations of TSH and FT4 were reported as medians and interquartile range (IQR) as their skewed distribution. Ln-transformed TSH and FT4 levels were used in all analyses. First, linear mixed regression model with restricted cubic splines (RCS) was used to examine the potential nonlinear relationship of TSH and FT4 levels with birth weight. Three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of TSH or FT4 levels were set in the model. When the nonlinearity was nonsignificant, the RCS option was taken out from the models and linear models were used to estimate the relationship of TSH and FT4 levels with birth weight. The study population of 1626 twin pregnancies included 3252 newborns. Linear mixed model with robust estimates of SEs to account for clustering of the birth weight within twin-pairs were used to estimate the adjusted coefficient. Birth weight for every newborn was set as the outcome variable and thyroid hormones (TSH and FT4) were set as explanatory variables, respectively. The nonindependence within twin pairs was taken into account by using repeated statement with subject option of SAS (version 9.4). Multivariable adjusted logistic regression model was used to estimate the association of TSH or FT4 levels with the risk of birth weight discordance in twins.

We tested for the possible effect modification of the association of TSH and FT4 with birth weight by fetal sex or chorionicity by adding product terms of fetal sex or chorionicity and TSH or FT4 concentrations (17, 18). Meanwhile, we performed analyses stratified by fetal sex and chorionicity, respectively, according to biological plausibility. It was reported that FT4 levels lower than the 10th percentile was related to a series of negative health outcomes in singleton pregnancy (17, 18). Hence, we performed analyses by treating FT4 levels as categorical variable (< 10th percentile, ≥ 90th percentile, 10th-90th percentile) in the present study. We also examined the association of subclinical hypothyroidism and hypothyroxinemia with birth weight. A total of 1543 twin-pairs were included in this part of analysis after excluding women diagnosed with other thyroid diseases (n = 83 pregnancies).

All covariates were included a priori in the final model according to previous studies, including parity (parous, nulliparous), fetal sex (boy, girl), chorionicity (DC, MC), maternal age at pregnancy (< 35 years, ≥ 35 years), prepregnancy BMI categories (underweight, optimal weight, overweight or obesity), trimester of thyroid function assessment (first, second, third trimester), and TPOAb status (positive, negative). To assess the robustness of our results, we also reran the analyses by refining to women with negative TPOAb, women who had thyroid function examined during the first trimester, or women without main pregnancy complications, including diagnosis of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational diabetes mellitus.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R statistical software version 4.0.3 (package “rms” and “visreg”). All tests were 2-sided and P less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Table 1 presents the characteristic of the study population. The majority of the women were younger than 35 years (81.1%), of Han ethnicity (97.8%), of Shanghai origin (66.0%), and nullipara (86.5%). A total of 282 (17.4%) women were prepregnancy overweight or obesity. More than half of the mothers had thyroid function assessment in the first trimester (64.1%). The median (IQR) concentrations of TSH and FT4 were 0.85 mU/L (0.20-1.69 mU/L) and 16.79 pmol/L (14.83-19.20 pmol/L), respectively. A total of 169 (10.4%) mothers were TPOAb positive (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at pregnancy, y | |

| ≥ 35 | 307 (18.9) |

| < 35 | 1319 (81.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Majority (Han) | 1579 (97.8) |

| Minority | 36 (2.2) |

| Prepregnancy BMI | |

| Underweight | 285 (17.5) |

| Optimal weight | 1059 (65.1) |

| Overweight | 227 (14.0) |

| Obesity | 55 (3.4) |

| Residence of origin | |

| Other areas | 553 (34.0) |

| Shanghai | 1073 (66.0) |

| Parity | |

| Multiparous | 220 (13.5) |

| Nulliparous | 1406 (86.5) |

| Gestational wk of TSH assessment, trimester | |

| First | 1042 (64.1) |

| Second | 533 (32.8) |

| Third | 51 (3.1) |

| TSH (median [IQR]), mIU/L | 0.85 (0.20-1.69) |

| FT4 (median [IQR]), pmol/L | 16.78 (14.83-19.20) |

| TPOAb status | |

| Negative | 1457 (89.6) |

| Positive | 169 (10.4) |

| Hypertension disorders during pregnancy | 202 (12.4) |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 145 (8.9) |

| Chorionicity | |

| Dichorionic | 1178 (72.4) |

| Monochorionic | 448 (27.6) |

| Birth weight (mean [SD]), g | 2416 (473) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FT4, free thyroxine; IQR, interquartile range; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TSH, thyrotropin.

Association of Birth Weight With Thyrotropin and Free Thyroxine Levels

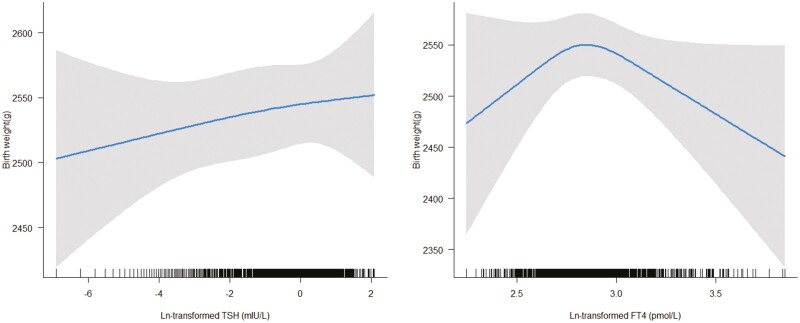

The mean birth weight was 2416 g(SD = 473 g) for all newborns. Linear mixed model with RCS did not indicate a nonlinear association of birth weight with FT4 levels (P for nonlinearity = .06), and TSH level (P for nonlinearity = .88) after excluding the outliers (n = 8) (Fig. 1). Linear regression analysis also showed that there was no association of TSH (β = 5.32; 95% CI, –3.43 to 14.07) of FT4 (β = –29.80; 95% CI, –111.69 to 52.09) with birth weight.

Figure 1.

Association of thyrotropin (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) levels with birth weight. Linear mixed model with restricted cubic splines did not indicate a nonlinear association of birth weight with TSH level (P for nonlinear = .88 [left]) and FT4 levels (P for nonlinear = .06 [right]) after excluding the outliers (n = 8).

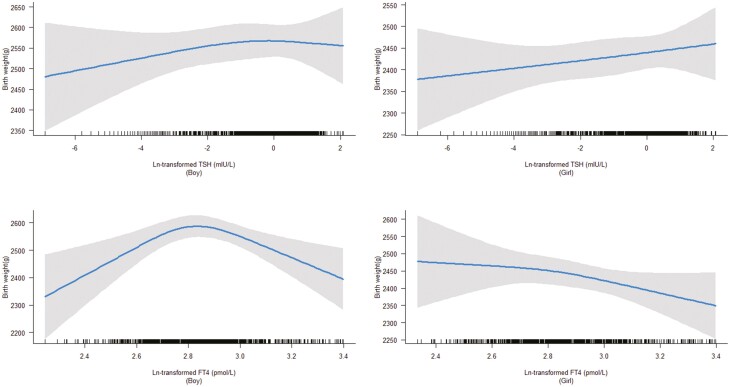

Although there was no indication of effect modification by fetal sex (P for interaction of sex and TSH = .57, and P for interaction of sex and FT4 = .86), we did observe an inverted U-shaped association between FT4 levels and birth weight in boys (P < .001), but not in girls (P = .56). There was no association of TSH levels with birth weight in boys or in girls (both P > .05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Association of thyrotropin (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) levels with birth weight stratified by fetal sex. We observed that there was a nonlinear association between FT4 levels and birth weight in boys (P < .001), but not in girls (P = .56), and there was no association of TSH levels with birth weight both in boys and girls (P > .05).

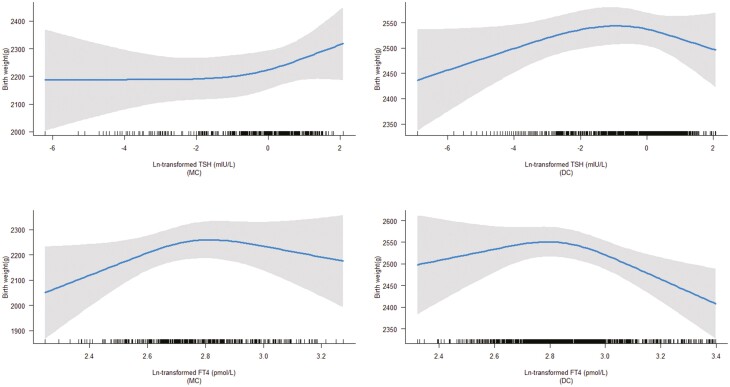

Similarly, there were no associations of TSH levels with birth weight both in MC and DC twins (P for interaction = .97), while the association of FT4 with birth weight differed according to chorionicity (P for interaction < .001). Specifically, there was an inverted U-shaped association of FT4 levels with birth weight in DC twins (P = 0.03), but not in MC twins (P > .05) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Association of thyrotropin (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) levels with birth weight stratified by chorionicity. We observed that there were no associations of TSH and FT4 levels with birth weight in monochorionic (MC) twins (P > .05), while there was a nonlinear association of FT4 levels with birth weight in dichorionic (DC) twins (P = 0.03).

Association of Birth Weight Discordance With Thyroid Function

The prevalence of birth weight discordance was 16.48% (268/1626) in the study population. When FT4 levels were treated as a continuous variable, we observed that there was an inverse association between FT4 levels and the risk of birth weight discordance. The odds ratio (OR) was 0.47 (95% CI, 0.25-0.87) (Table 2). When the population was divided into 3 groups according to the percentiles of FT4 levels, we observed that women with levels of FT4 lower than the 10th percentile had a higher risk of birth weight discordance than women with optimal FT4 levels (OR = 1.58, 95% CI, 1.05-2.33) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of free thyroxine levels and risk of birth weight discordance in twins

| No. (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSH levels (continuous) | 1.03 (0.96-1.11) | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) | |

| FT4 levels (continuous) | 0.38 (0.19-0.69) | 0.47 (0.25-0.87) | |

| 10th-90th percentile | 209 (16) | Reference (1.00) | Reference (1.00) |

| < 10th percentile (13.29) | 40 (25) | 1.74 (1.17-2.55) | 1.58 (1.05-2.33) |

| ≥ 90th percentile (22.40) | 19 (12) | 0.69 (0.41-1.11) | 0.75 (0.44-1.21) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FT4, free thyroxine; OR, odds ratio; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TSH, thyrotropin.

a Adjusted for parity, chorionicity, maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, trimester of thyroid function assessment, and TPOAb status.

In addition, women were categorized as having subclinical hypothyroidism (low TSH [< 2.5 percentile], normal FT4 [2.5-97.5 percentile]), hypothyroxinemia (normal TSH [2.5-97.5 percentile], lower FT4 [< 2.5 percentile]), and euthyroid, respectively. We observed an increased risk of birth weight discordance in women diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia compared with euthyroid women, although the CI included the null due to limited sample size (subclinical hypothyroidism: OR = 1.32; 95% CI, 0.38-3.63; hypothyroxinemia: OR = 1.60; 95% CI, 0.73-3.24) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia and risk of birth weight discordance in twins

| No. (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euthyroid | 242 (16.3) | Reference (1.00) | Reference (1.00) |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 4 (19.1) | 1.20 (0.34-3.29) | 1.32 (0.38-3.63) |

| Hypothyroxinemia | 10 (25.0) | 1.71 (0.78-3.42) | 1.60 (0.73-3.24) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody.

a Adjusted for parity, chorionicity, maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, trimester of thyroid function assessment, and TPOAb status.

When we reran the analyses by refining to categories women with negative TPOAb, women whose thyroid function was examined during the first trimester, women without diagnosis of preeclampsia, eclampsia, or gestational diabetes mellitus, the association patterns did not change substantially (data available on request).

Discussion

In the present study, we showed an inverted U-shaped association of FT4 levels with birth weight in boys and in DC twins. We also observed that decreased FT4 levels during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of birth weight discordance. We did not observe a statistically significant association of TSH concentrations with birth weight or birth weight discordance in twins.

Maternal thyroid hormones play an important role in fetal development. There is abundant evidence that hCG is a weak thyrotropin agonist. Compared with singletons, hCG concentration is higher in early pregnancy in twins, which may cause significantly decreased TSH levels and a more pronounced physiologic suppression (15, 17, 21). Ogueh et al (22) found that FT4 significantly related to the number of fetuses. The circulating concentrations of FT4 in multifetal pregnancies decreased progressively after fetal reduction to twins. It has been well elucidated that maternal FT4 rather than TSH could cross the placental barrier and be transmitted to the fetus to maintain fetal development in early pregnancy (23-25). A previous study indicated that higher FT4 in euthyroid women was correlated with lower maternal glucose and triglycerides levels, which might result in decreased glucose transferred to the fetus and consequent fetal weight gain (26). There were also some studies showing a trend of association between elevated maternal TSH levels and low birth weight in singletons (27, 28).

Evidence on the relationship between thyroid function and birth weight in twin pregnancy remains limited. Our study indicated there was no relationship between TSH and birth weight in twins. The formation and maturation of the neonatal hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis begins in utero, and fetal circulating TSH concentration remains very low until approximately 18 to 20 weeks of gestation. The negative feedback in the fetal pituitary gland is still immature, and the increase of FT4 has little inhibitory effect on TSH secretion. Actually, the HPT axis does not fully function until 1 to 2 months after birth, which could partly explain the reason for no correlation between TSH level and birth weight.

It has been reported that the birth weight in twin pregnancy is lower in women with TPOAb positivity than in those with negative TPOAb (29). The results, however, did not change substantially in our study when confining analyses to women with negative TPOAb status. A study from Rotterdam showed that TPOAb positivity was not associated with birth weight, and a review of thyroid autoimmunity and pregnancy outcomes also suggested that TPOAb positivity was not associated with birth weight (29), which also partly supported our results. Our study showed that maternal FT4 level was positively associated with birth weight in boys but not in girls, which is consistent with another study (30). One study in singleton pregnancy indicated that the placentas of mothers carrying a female fetus have a higher reserve capacity and adaptability compared with those of a male fetus (31). In addition, in a review article of animal and human studies, researchers indicated that placentas of mothers carrying males and females may be sensitive to stressors at different periods of gestation (32). In same-sex male twins, the difference in placental thickness and surface area was positively associated with the difference of birth weight. However, in same-sex female twins, the link weakened. Therefore, these differences suggest that the growth of males is more dependent on placental transport than that of females (33), which supported our result about the association of FT4 with birth weight in boys.

When stratifying by chorionicity, there was an association of FT4 levels and birth weight in DC twins, but not in MC twins. A previous study reported that cord TSH levels tended to be higher in MC twins, and birth weight discordance was associated with a significantly higher cord blood TSH levels (34). In DC twins, the 2 fetuses have independent placentas. It is well known that maternal thyroid hormones are mainly transmitted to the fetus through the placenta; because DC twins have 2 placental units, therefore, the metabolism of thyroid hormones by the placenta should be increased accordingly. Therefore, the fetal development of DC twins may need more thyroid hormone, and may also be more sensitive to thyroid hormone changes. However, the underlying mechanism still needs further study.

Birth weight discordance is considered to be the final common way of various physiological and pathological processes affecting twins’ intrauterine growth, including structural differences in growth potential between twin-pairs, sex differences, inconsistencies in placental function in utero, and genetic abnormalities. At present, a considerable number of studies have shown that thyroid function during pregnancy is closely related to the occurrence of gestational hypertension and a recent study suggests that mothers of twins with inconsistent weight have a higher risk of preeclampsia and are positively associated with the degree of weight inconsistency between twin-pairs (35). Maternal nutrition, hypertension, and diabetes affect the maternal growth factor axis, reducing placental nutrient transfer and ultimately compromising the fetal growth factor axis and prenatal growth. In our study, the decrease of FT4 level led to an increased risk of birth weight discordance. Blickstein et al conducted a study based on a large database of twin births from the United States, Poland, and Israel, proposing that total twin birth weight may be considered as a measure for the uterine capacity for fetal growth, and the more favorable the uterine milieu for carrying twins, the smaller the likelihood that twins show high degrees of discordant growth (36). Therefore, our result that decreased FT4 levels were associated with an increased risk of birth weight discordance was reasonable in this sense. The underlying mechanism warrants further study.

To our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association of thyroid function in twins by chorionicity and fetal sex, and we report an association of FT4 levels with birth weight mainly in DC twins. Our result should be interpreted with caution. First, this study was performed in single hospital in Shanghai. However, nearly one-fifth of babies in Shanghai have been delivered in the study institute in the past 8 years. We believe, therefore, that the study population is a good representative sample of Shanghai and developed areas in China. Second, there is no specific reference range for thyroid dysfunction in twin pregnancy at present. We used the normal reference range of TSH and FT4 levels for singletons for the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism and hypothyroxinemia in the present study. Third, as an observational study, we reported an association, rather than causal relationship, between FT4 and birth weight in twin pregnancy.

In conclusion, our study suggests there is an association of FT4, but not TSH, with birth weight and birth weight discordance varies by fetal sex and chorionicity. These findings could have implications for obstetricians to be aware of the importance of FT4 levels in the prevention of birth weight discordance in twin pregnancy. Nevertheless, the evidence of our study was modest and this finding needs to be confirmed in a larger cohort.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- DC

dichorionic

- FT4

free thyroxine

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- HPT

hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid

- IQR

interquartile range

- MC

monochorionic

- OR

odds ratio

- RCS

restricted cubic splines

- TPOAb

thyroid peroxidase antibody

- TSH

thyrotropin

Contributor Information

Xiao Song Liu, Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Xiu Juan Su, Clinical Research Center, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Guo Hua Li, Department of Reproductive Immunology, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Shi Jia Huang, Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Yang Liu, Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Han Xiang Sun, Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Qiao Ling Du, Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Pu-dong Health and Family Planning Committee (grant No. PW2019D-9) and the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (grant No. 20Y11907900).

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: X.S.L., G.H.L., and Q.L.D.; acquisition of data: X.S.L., S.J.H., Y.L., and Q.L.D.; analysis and interpretation of data: X.J.S., G.H.L., X.S.L., and Q.L.D.; preparation of manuscript: X.S.L., X.J.S., G.H.L., H.X.S., and Q.L.D.; critical revision: X.J.S., G.H.L., H.X.S., X.S.L., and Q.L.D. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

All data sets generated during and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kampouri M, Margetaki K, Koutra K, et al. Maternal mild thyroid dysfunction and offspring cognitive and motor development from infancy to childhood: the Rhea mother-child cohort study in Crete, Greece. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(1):29-35. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giannocco G, Kizys MML, Maciel RM, de Souza JS. Thyroid hormone, gene expression, and central nervous system: where we are. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2021;114:47-56. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schneuer FJ, Nassar N, Tasevski V, Morris JM, Roberts CL. Association and predictive accuracy of high TSH serum levels in first trimester and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3115-3122. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shinohara DR, Santos TDS, de Carvalho HC, et al. Pregnancy complications associated with maternal hypothyroidism: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(4):219-230. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Idris I, Srinivasan R, Simm A, Page RC. Maternal hypothyroidism in early and late gestation: effects on neonatal and obstetric outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(5):560-565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Derakhshan A, Peeters RP, Taylor PN, et al. Association of maternal thyroid function with birthweight: a systematic review and individual-participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):501-510. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30061-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swamy RS, McConachie H, Ng J, et al. Cognitive outcome in childhood of birth weight discordant monochorionic twins: the long-term effects of fetal growth restriction. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(6):F512-F516. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schulte S, Gohlke B, Schreiner F, et al. Thyroid function in monozygotic twins with intra-twin birth weight differences: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. J Pediatr. 2019;211:164-171.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korevaar TIM, Chaker L, Jaddoe VWV, Visser TJ, Medici M, Peeters RP. Maternal and birth characteristics are determinants of offspring thyroid function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(1):206-213. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karagiannis G, Ashoor G, Maiz N, Jawdat F, Nicolaides KH. Maternal thyroid function at eleven to thirteen weeks of gestation and subsequent delivery of small for gestational age neonates. Thyroid. 2011;21(10):1127-1131. doi:10.1089/thy.2010.0445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang X, Wu P, Chen Y, et al. Does maternal normal range thyroid function play a role in offspring birth weight? Evidence from a mendelian randomization analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:601956. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.601956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Cantonwine DE, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD, McElrath TF. Subclinical changes in maternal thyroid function parameters in pregnancy and fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(4):1349-1358. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jahanfar S, Lim K, Oviedo-Joekes E. Stillbirth associated with birth weight discordance in twin gestations. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(1):52-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D’Antonio F, Odibo AO, Prefumo F, et al. Weight discordance and perinatal mortality in twin pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52(1):11-23. doi: 10.1002/uog.18966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grün JP, Meuris S, De Nayer P, Glinoer D. The thyrotrophic role of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) in the early stages of twin (versus single) pregnancies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;46(6):719-725. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2011011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krassas G, Karras SN, Pontikides N. Thyroid diseases during pregnancy: a number of important issues. Hormones (Athens). 2015;14(1):59-69. doi: 10.1007/BF03401381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashoor G, Muto O, Poon LCY, Muhaisen M, Nicolaides KH. Maternal thyroid function at gestational weeks 11-13 in twin pregnancies. Thyroid. 2013;23(9):1165-1171. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Šálek T, Dhaifalah I, Langova D, Havalová J. Maternal thyroid-stimulating hormone reference ranges for first trimester screening from 11 to 14 weeks of gestation. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32(6):e22405. doi:10.1002/jcla.22405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen Z, Yang X, Zhang C, et al. Thyroid function test abnormalities in twin pregnancies. Thyroid. 2021;31(4):572-579. doi:10.1089/thy.2020.0348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morin L, Lim K. No. 260-Ultrasound in twin pregnancies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(10):e398-e411. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dashe JS, Casey BM, Wells CE, et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone in singleton and twin pregnancy: importance of gestational age-specific reference ranges. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):753-757. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175836.41390.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ogueh O, Hawkins AP, Abbas A, Carter GD, Nicolaides KH, Johnson MR. Maternal thyroid function in multifetal pregnancies before and after fetal reduction. J Endocrinol. 2000;164(1):7-11. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1640007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andersen SL, Andersen S, Vestergaard P, Olsen J. Maternal thyroid function in early pregnancy and child neurodevelopmental disorders: a Danish nationwide case-cohort study. Thyroid. 2018;28(4):537-546. doi:10.1089/thy.2017.0425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lecorguillé M, Léger J, Forhan A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with preexisting thyroid diseases: a French cohort study. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2021;12(5):704-713.doi:10.1017/S2040174420001051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Springer D, Jiskra J, Limanova Z, Zima T, Potlukova E. Thyroid in pregnancy: from physiology to screening. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54(2):102-116. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2016.1269309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun X, Liu W, Zhang B, et al. Maternal heavy metal exposure, thyroid hormones, and birth outcomes: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(11):5043-5052. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee SY, Cabral HJ, Aschengrau A, Pearce EN. Associations between maternal thyroid function in pregnancy and obstetric and perinatal outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(5):e2015-e2023. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen GD, Pang TT, Lu XF, et al. Associations between maternal thyroid function and birth outcomes in Chinese mother-child dyads: a retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:611071. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.611071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang N, Chen L, Lian Y, et al. Impact of thyroid autoimmunity on in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes and fetal weight. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:698579. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.698579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vrijkotte TGM, Hrudey EJ, Twickler MB. Early maternal thyroid function during gestation is associated with fetal growth, particularly in male newborns. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):1059-1066. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Thornburg K, Barker DJP. Boys live dangerously in the womb. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22(3):330-335. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freedman AA, Hogue CJ, Marsit CJ, et al. Associations between features of placental morphology and birth weight in dichorionic twins. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(3):518-526. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalisch-Smith JI, Simmons DG, Dickinson H, Moritz KM. Review: sexual dimorphism in the formation, function and adaptation of the placenta. Placenta. 2017;54:10-16. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan LYS, Chiu PY, Lau TK. Cord blood thyroid-stimulating hormone level in twin pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(1):28-31. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.820105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qiao P, Zhao Y, Jiang X, et al. Impact of growth discordance in twins on preeclampsia based on chorionicity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):572.e1-572.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blickstein I, Goldman RD, Smith-Levitin M, et al. The relation between inter-twin birth weight discordance and total twin birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):113-116. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00343-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data sets generated during and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.