Abstract

Among outpatients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to the severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) δ (delta) variant who did and did not receive 2 vaccine doses at 7 days after symptom onset, there was no difference in viral shedding (cycle threshold difference 0.59, 95% CI, −4.68 to 3.50; P = .77) with SARS-CoV-2 cultured from 2 (7%) of 28 and 1 (4%) of 26 outpatients, respectively.

Until the emergence of the severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) ο (omicron) variant, the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant of concern (VOC) was dominant worldwide. The SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant is more transmissible than ancestral SARS-CoV-2 and appears to cause more severe disease. 1 Our evaluation of the viral shedding trajectory of non-VOC SARS-CoV-2 prior to vaccine availability demonstrated that immunocompetent individuals attained a maximum viral load at 2–3 days following symptom onset and remained capable of transmission for ∼9 days. 2–4 Whether this trajectory is different for infections with the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant or how viral kinetics are altered by vaccination remains unclear.

Information about the duration of shedding of different SARS-CoV-2 VOCs and the impact of vaccination is crucial to informing recommendations to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines are very effective in preventing severe manifestations of COVID-19, but breakthrough infections after 2 doses of mRNA vaccines increase in frequency as vaccine efficacy wanes. Although a faster initial decline in viral load has been observed in breakthrough infections, it is unclear whether it translates into a reduced risk of transmission. 5,6 We assessed the SARS-CoV-2 viral load in vaccinated and unvaccinated outpatients with COVID-19 due to the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant at 7 days following symptom onset.

Methods

Study setting

In Ontario, the available COVID-19 vaccines were Comirnaty, Spikevax, and Vaxzevria. By September 2021, nearly 90% of adults had had 2 vaccine doses, and the estimated seroprevalence of prior COVID-19 was 5.9% (https://www.covid19immunitytaskforce.ca/results-blood-donation-organizations/). From week 33 (August 15) to week 48 of 2021, >98% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario were the δ (delta) variant (https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/nCoV/epi/covid-19-sars-cov2-whole-genome-sequencing-epi-summary.pdf?sc_lang=en).

Study population

Eligible participants were consecutive adults (aged 18 years or older) who presented to outpatient COVID-19 assessment centers at a single hospital in Toronto between August 24 and September 20, 2021, and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were within 7 days of symptom onset (or test date if asymptomatic) and provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Michael Garron Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Specimen collection

Participants were provided instructions on how to self-collect a combined oral–nasal swab on day 7 following symptom onset (or 7 days following the test in asymptomatic participants). Each participant self-swabbed the back of the tongue, buccal mucosa, and the anterior aspect of both nares. 7 All specimens were placed into viral transport medium (Copan Diagnostics, Murrieta, CA), were refrigerated until processed (within 24 hours), and were then frozen at −80°C until they were cultured.

Laboratory analysis

A 160-μL aliquot of viral transport media was extracted on the MGISP-960 automated workstation using the MGI Easy Magnetic Beads Virus DNA/RNA Extraction Kit (MGI Technologies, Shenzhen, China). Detection of SARS-CoV-2 E gene and 5-UTR and the internal control (RNase P) were performed using the Luna Universal Probe One-Step RT-qPCR kit (New England Biolabs, Whitby, Ontario) on the CFX96 Touch real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection system (BioRad, Mississauga, Ontario) as previously described. 7 Whole-genome sequencing was attempted from the initial specimen from all participants, and virus isolation was attempted from day 7 specimens of the 25 with the lowest E-gene cycle threshold (Ct) values (range, 16.9–26.6). Both were performed as previously described. 8

Analysis

Demographic information was presented with medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. The primary outcome was the difference in E-gene Ct values on day 7 between participants who had received 2 COVID-19 vaccine doses to participants who had not. All analyses were performed in R version 4.1.2 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

From August 24 until September 20, 2021, 357 adults tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 265 were eligible for study inclusion. Overall, 59 participants were enrolled and 54 submitted day 7 specimens; 28 of these had received 2 COVID-19 vaccine doses, 13 received 1 dose, and 13 were unvaccinated. We successfully completed whole-genome sequencing on the original specimens from 43 participants, all of which were the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant (most commonly AY.25 or AY.74). The median age of participants was 41 years (interquartile range [IQR], 30–52 years), 32 (59%) of 54 were female, 51 (94%) of 54 were symptomatic (median, 2 days; IQR, 1–3 from symptom onset). The most common comorbidity was hypertension in 4 (7%) of 54 (Supplementary Table 1 online). Of the 28 participants with 2 COVID-19 vaccine doses, 21 (75%) received 2 mRNA vaccines, 5 (18%) received 2 viral-vector vaccines, and 2 (7%) received different vaccine types. All 13 participants with 1 dose received an mRNA vaccine. In participants infected after 2 doses of vaccine, the median time from the second dose to symptom onset was 75 days (IQR, 62–82).

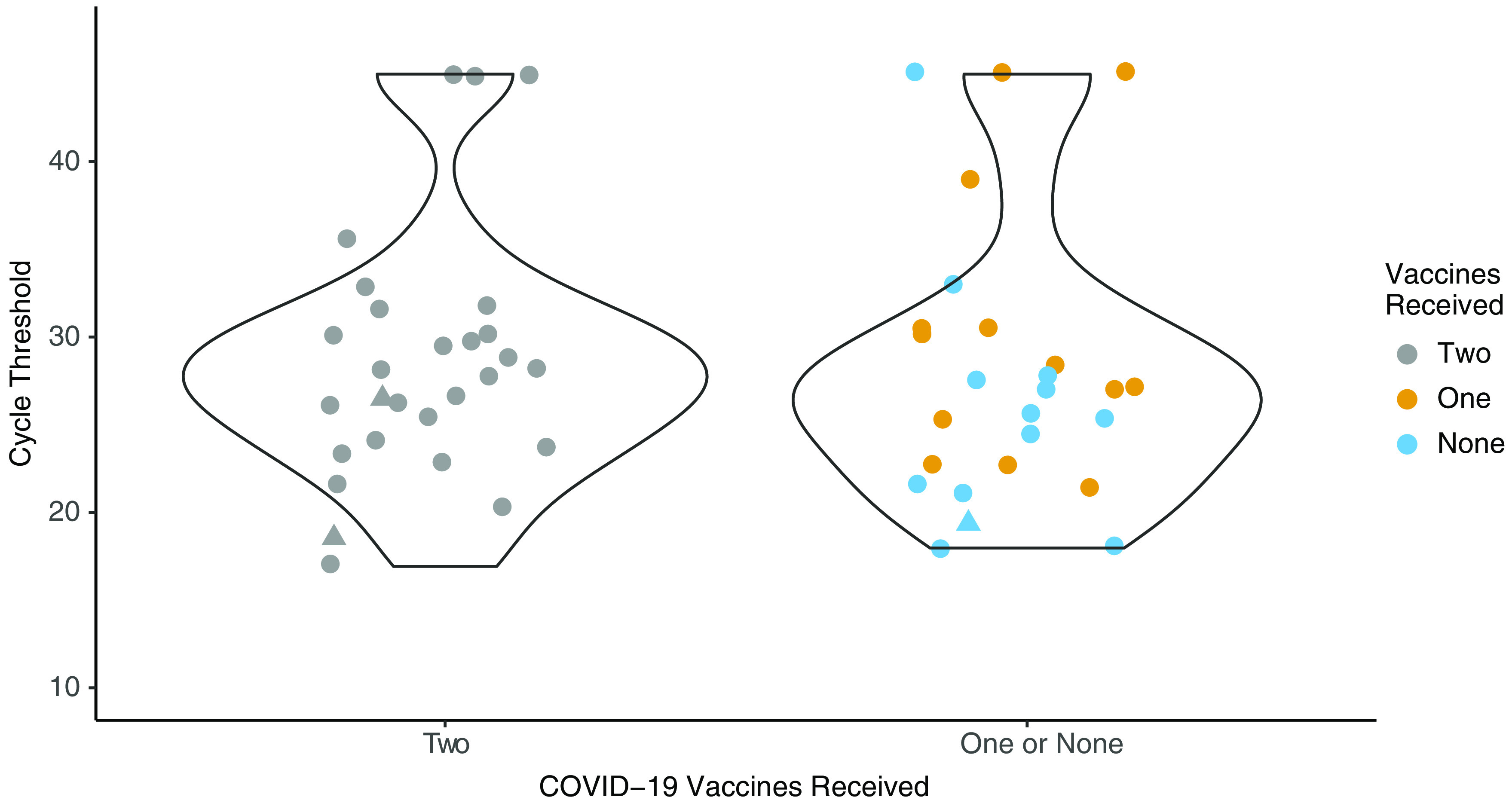

Eighty-nine percent of participants in both groups (25 of 28 and 23 of 26, respectively) had detectable SARS-CoV-2 at day 7. There was wide variation in the Ct values at day 7 (Fig. 1). Participants infected after 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccine had a median Ct value for the E gene of 26.6 (IQR, 23.8–29.8), and those who were unvaccinated or had received a single vaccine dose had a median Ct of 25.7 (IQR, 22.1–28.1; difference 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], −4.68 to 3.50; P = .77). Virus was cultured on day 7 specimens from 3 (5.6%) of 54 participants: 2 who had received 2 vaccine doses (1 with both viral vector and 1 with both mRNA) and 1 who was unvaccinated. The cycle thresholds were 18.4, 26.4, and 19.3, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Cycle threshold values from a self-collected oral–nasal swab at day 7 following symptom onset for the SARS-CoV-2 E-gene separated by vaccine doses. The triangles denote the specimens where SARS-CoV-2 could be cultured of the 25 with the lowest cycle thresholds that were evaluated.

Discussion

In our study of outpatients with COVID-19 due to the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant, we did not detect a difference in viral shedding at day 7 based on vaccination status. Our findings suggest that, for the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant, shorter isolation periods may not be indicated for individuals who have received two doses of vaccine.

At least 3 studies describing the viral kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) variant have identified more rapid clearance among those who are vaccinated compared with those who are unvaccinated. 5,6,9 These results are not, however, incompatible with ours. In one study, viral clearance was faster in participants who were vaccinated, but differences only occurred after day 7. 9 In another, the effect of vaccination on the viral kinetics for individual VOCs by vaccine doses was not evaluated, and apparent differences were not statistically significant. 6 In the third study, a comparison of viral loads at specific time points after symptom onset was not reported. 5 Thus, speed of clearance may not closely correlate with viral shedding on a particular day after symptom onset.

The Ct values of samples from which infectious virus could be isolated varied, which supports the observations of Puhach et al, 10 who reported a low correlation between genome copies of virus in nasopharyngeal swabs and infectious viral titers. Similar to our results, they observed only a small difference in RNA genome copies in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients; however, vaccinated patients had lower infectious viral titers. 10

Our study had several limitations. Participants were young and without immunocompromising conditions, and our results may not be generalizable to other populations. We used Ct values to approximate viral load, and we did not attempt to culture specimens with Ct values >30. Most breakthrough infections in our study occurred 2–3 months after the patient’s second vaccine dose, and results may differ >2–3 months after the last vaccine dose. Our sample size was small, and infectious virus was isolated from too few participants to warrant assessing differences in infectious titers.

Our data suggest that unvaccinated people and people whose second vaccine dose was >2 months prior to contracting the SARS-CoV-2 δ (delta) VOC have a similar probability of having communicable virus 7 days following symptom onset. Thus, healthy persons who have received 2 vaccine doses may remain as likely to transmit infection as those who were not vaccinated or who had received 1 dose. Additional studies are needed to assess the risk following third vaccine doses and other circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the ο (omicron) variant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff and patients of the COVID-19 assessment centres at the Michael Garron Hospital, without whose support and participation this study was not possible.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.124.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

A.M. and S.M. received grant support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Drs. McGeer (grant no. 465038) and Mubareka (grant no. 466984). R.K. received support from an Ontario Together grant from the province of Ontario as well as a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant no. 440385).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1. Fisman DN, Tuite AR. Evaluation of the relative virulence of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants: a retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2021;193:E1619–E1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kissler SM, Fauver JR, Mack C, et al. Viral dynamics of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and applications to diagnostic and public health strategies. PLoS Biol 2021;19:e3001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walsh KA, Jordan K, Clyne B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 detection, viral load and infectivity over the course of an infection. J Infect 2020;81:357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021;2:e13–e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singanayagam A, Hakki S, Dunning J, et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22:183–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kissler SM, Fauver JR, Mack C, et al. Viral dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 variants in vaccinated and unvaccinated persons. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2489–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kandel CE, Young M, Serbanescu MA, et al. Detection of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in outpatients: a multicenter comparison of self-collected saline gargle, oral swab, and combined oral-anterior nasal swab to a provider collected nasopharyngeal swab. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021;42:1340–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotwa JD, Jamal AJ, Mbareche H, et al. Surface and air contamination with SARS-CoV-2 from hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Toronto, Canada, March–May 2020. J Infect Dis 2022;225:768–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chia PY, Xiang Ong SW, Chiew CJ, et al. Virological and serological kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 delta variant vaccine-breakthrough infections: a multi-center cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022;28:612.e1–612.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Puhach O, Adea K, Hulo N et al. Infectious viral load in unvaccinated and vaccinated patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 WT, delta and omicron. Nat Med 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.124.

click here to view supplementary material