Abstract

Aging-related decline in immune functions, termed immunosenescence, is a primary cause of reduced protective responses to vaccines in the elderly, due to impaired induction of cellular and humoral responses to new antigens (Ag), especially if the response is T cell dependent. The result is more severe morbidity following infection, more prolonged and frequent hospitalization, and a higher mortality rate than the general population. Therefore, there is an increasing need to develop vaccination strategies that overcome immunosenescence, especially for aging-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here we report a new vaccination strategy harnessing memory-based immunity, which is less affected by aging. We found that aged C57BL/6 and 5xFAD mice exhibit a dramatic reduction in anti-Amyloid-β (Aβ) antibody (Ab) production. We aimed to reverse this process by inducing memory response at a young age. To this end, young mice were primed with the vaccine carrier Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). At an advanced age, these mice were immunized with an Aβ1–11 fused to HBsAg. This vaccination scheme elicited a markedly higher Aβ-specific antibody titer than vaccinating aged unprimed mice with the same construct. Importantly, this vaccine strategy more efficiently reduced cerebral Aβ levels and altered microglial phenotype. Overall, we provide evidence that priming with an exogenous Ag carrier can overcome impaired humoral responses to self-antigens in the elderly, paving the route for a potent immunotherapy to AD.

Keywords: Immunosenescence, Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid-β, Vaccine, Priming, Microglia

Introduction

Immunosenescence is a key obstacle to effective immunization at old age [1–3]. In humans, an aging-related decrease in immune function leads to a higher incidence of infections, neoplasia, and autoimmune diseases [2]. The hallmarks of immunosenescence include a reduced response to new antigens (Ags), accumulation of antigen-experienced memory B and T cells, and chronic low-grade inflammation, termed inflammaging. These are manifested by a progressive reduction of the ability to trigger effective humoral and cellular responses, especially to previously unencountered Ags [3].

Humoral immunity is impaired in the elderly due to (a) a reduced number of CD4 T cells and (Ig)-producing B cells because of micro-environmental defects, and (b) decreased diversity and affinity of Ig due to disrupted germinal center formation [2]. This is accompanied by a number of innate immunity deficits that compromise Ag-presentation [1–3] and reduced T cell functionality, which result in aberrant T cell/B Cell interaction [2].

Vaccination efficacy decreases with aging, resulting in higher infection-related morbidity and mortality in the elderly. For example, older adults remain increasingly susceptible to pneumococcal infections after vaccination due to reduced B and T cell responses, impaired functions of IgG Abs, and decreased opsonization by neutrophils [3]. To circumvent these problems, repeated vaccinations, e.g. against influenza with the same viral strains, are needed to achieve a protective response in the elderly [3]. Potential approaches also include immune check-point inhibition, high-dose vaccines, booster vaccinations, different immunization routes, and the development of novel adjuvants. Another strategy is immune priming, i.e. repetitive challenges by the same Ag during the host lifetime, which results in an improved response [4], presumably using advantages of increased memory/effector T cells in aging [3].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent dementia of the elderly [5], is associated with Amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation in the brain. Based on the Amyloid-cascade hypothesis, Aβ is not only a pathologic hallmark of AD [6, 7], but also could be a causative factor of AD [6, 8–10]. We previously reported that vaccination with AβCoreS DNA vaccine induces Aβ-specific antibodies capable of reducing Aβ-induced neurodegenerative pathology in aged 3xTg-AD mice, a model of AD-like pathology [11]. AβCoreS vaccine is designed to express human Aβ1–11 (a B cell epitope) on the surface of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface Ag (HBsAg), a primary component of the HBV vaccine [12], together with T-helper epitopes of HBV capsid Ag (HBcAg) to facilitate more potent Ab production [11]. Unlike vaccines expressing full-length protein Aβ1–42 [13], AβCoreS vaccine is not only a more potent inducer of antibody to Aβ, but also appears to be safer. AβCoreS does not elicit a potentially harmful Aβ-specific T cell responses in the brain due to the lack of T cell epitope in the Aβ1–11 fragment [11]. In 3xTg-AD mice that model AD and Ts65Dn mice that express triplicated murine Aβ to model Down syndrome [14], AβCoreS immunization delayed cognitive decline by respectively reducing human and murine Aβ oligomers in the brain [11, 15].

Here we devised a novel strategy for inducing Aβ-specific antibody responses in aged mice that model AD by first priming with a vaccine carrier when the mice were young. We hypothesized that priming would establish a memory response that could be boosted at older, immunosenescent age. We demonstrate that the deficit in the induction of humoral responses in 18m-old WT C57BL/6J and 12m-old 5xFAD mice, an early-onset AD (EOAD) model, was indeed reversed if the mice were primed with HBsAg alone and then boost-immunized at an older age with AβCoreS. Compared with unprimed AD mice, the prime in young and boost in old strategy resulted in more efficient control of AD-related neuropathology.

Materials and methods

Animals.

The 5xFAD mouse model of EOAD (Jackson Laboratories #34840), which encompasses five AD-related mutations within the APP and PSEN1 genes [16], generously provided by Michal Schwartz (The Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, Israel), was used in this study. C57BL/6J mice were used as healthy controls (Jackson Laboratories #000664). Animal care and experimental procedures followed the ARRIVE guidelines and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This study was approved by the Bar-Ilan University Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with institutional guidelines.

AβCoreS vaccine.

AβCoreS is based on the pVAX1 expression vector [11] and encodes the N-terminus-Aβ1–11 fragment fused to a Hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) and the Hepatitis-B capsid antigen (HBcAg), which act to facilitate Ab production [17]. As priming, an expression vector (pUC19, New England Biolabs) containing HBsAg was used.

Vaccine administration to C57BL/6J mice.

DNA vaccination was administered to WT mice using the gene-gun method. Mice were vaccinated at three time-points (14-day intervals) with 1µg of DNA per vaccination episode. Briefly, the mice’s abdomen skin was shaved, cleaned with ethanol (70%), and dried. DNA was delivered to the mice’s abdomen skin using the Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad) attached to a compressed helium tank of grade 4.5 (>99.995%), at 300 psi, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Vaccine administration to 5xFAD mice.

DNA vaccination was administered to 5xFAD mice using the electroporation method. The mice were intramuscularly injected at three time-points (14-day intervals) with 25µg DNA (50µl), and electroporation was administered immediately to the area of the injection using a two-needle array electrode, 10mm (BTX, 45–0167), and an ECM830 electroporator (BTX, 45–2052). Electroporation configuration: one pulse of 450V/cm, 2 repetitions, duration=0.05ms, interval=0.125s following a second pulse of 110V/cm, 8 repetitions, duration=10ms, interval=0.125s [11].

Serum collection.

Blood was extracted from the facial vein using a glass cannula and incubated for 30min at RT to clot. Samples were then centrifuged at 1500×g for 8min at 4°C, and clear serum was stored at −20°C for further analysis.

Antibody titer.

The anti-Aβ1–11 and anti-HBsAg Ab production was quantified by a standard indirect ELISA. 96-well high binding microplates (655061, Greiner bio-one) were covered with 50µl of recombinant mouse Aβ1–11 (custom synthesis, Adar-Biotech) or HBsAg (Ab167754, Abcam) peptides in carbonate/bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) at a concentration of 3µg/ml. Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed 3 times with 0.1% PBS-Triton, and blocked with 2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, A7906, Sigma) for 1h at RT. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS-T followed by serum incubation at dilutions of 1:100–1:12,500 for 1h at RT. A standard curve was carried out using known concentrations of primary rabbit anti-Aβ Aβ1–14 Ab (50–500ng/ml, ab2539, Abcam). Plates were washed 3 times in PBS-T and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary Abs diluted at 1:5,000 (115–035-003, Peroxidase AffiniPure, Jackson Immunoresearch) or goat anti-rabbit secondary Ab for standard curve wells (111–035-003, Peroxidase AffiniPure, Jackson Immunoresearch) for 1h at RT. Plates were washed 3 times in PBS-T, and 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (00–4201-56, Affymetrix eBioscience) was applied. The colorimetric reaction was stopped by adding 50μl of 2M H2SO4 solution (339741, Sigma-Aldrich). OD was measured at 450nm using a spectrophotometer.

Immunoglobulin isotyping.

IgG isotyping was conducted using a similar indirect ELISA protocol with the addition of specific anti-mouse-immunoglobulin Abs (ISO-2, Sigma-Aldrich) diluted at 1:1000, incubated for 30min at RT. Next, donkey anti-goat secondary Ab (705–035-003, Peroxidase AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Goat IgG, Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted at 1:5,000 was applied for 1h at RT. Anti-Aβ IgG2c levels were measured by indirect ELISA using an HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG2c secondary antibody (115–035-208, Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, Fcγ subclass 2c specific, Jackson Immunoresearch), diluted at 1:5,000, as described above.

Immune-complex dissociation.

HBsAg ICs were measured as previously described [18]. Briefly, the same ELISA protocol described above was used with sera pre-treated with 0.1M glycine (pH=2.5, at a ratio of 2:1 sample:glycine) for 5min at RT with gentle agitation for dissociation of ICs. Treated and untreated sera were applied to the ELISA plate. Glycine-treated samples were neutralized with 0.25M TRIS-HCl (pH=8.8, at a ratio of 3:1, sample-glycine:Tris-HCl) 5min after the addition of samples. Samples were incubated for 1h. IC level was calculated as ΔOD (treated-untreated samples), as dissociation of ICs results in higher levels of free IgG Abs that can bind to the coated ELISA plate.

Short-term object recognition memory.

Short-term memory was assessed using the novel object recognition (NOR) test as previously described [19, 20]. Briefly, mice were placed in a 40×40cm arena with two different objects. Illumination was kept at 20lux. In an acquisition trial, mice were allowed to explore their environment. In the following test trial, one of the objects was replaced by a novel object. Time spent near each of the objects was measured. A preference index was calculated as the difference between time spent in the novel and familiar objects, divided by the total time spent near both objects. Analysis of animal behavior in this task and the following tasks was conducted using the Anymaze software (Stoelting).

Anxiety assessment.

Anxiety-related behavior was monitored using the elevated zero maze (EZM), a ring-shaped 65cm-high table divided into closed and opened sections. The ring is 7cm wide and has an outer diameter of 60cm. The closed sections are confined by 20cm-high walls and a semi-transparent ceiling, whereas the opened sections have 0.5cm high curbs at the edges. Illumination was kept at 1300lux, and the trial duration was 5 minutes [21].

Exploratory behavior.

Exploratory behavior was recorded using a 40×40cm open field (OF) arena. The outer 8cm were defined as the area periphery and the 24×24cm inner square as the center. Illumination was kept at 1300lux. Mice were allowed to freely explore the arena for 5min [22].

Brain Sample collection.

Mice were anesthetized using Ketamine-Xylazine (100mg/kg, Vetoquinol, 10mg/kg, Eurovet) and perfused with PBS. For Histology, hemibrains were transferred to 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C for 48h. Following fixation, tissues were transferred to a gradient of 20% and 30% sucrose aqueous solutions for 24h each. Hemibrains were then dissected into 40μm-thick slices using a microtome and stored in a cryoprotectant solution (30% glycerol and 35% ethylene glycol) at −20°C. For biochemical analysis, the cerebral cortex and hippocampi were separated, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C.

Measuring Aβ40/42 levels using sELISA.

Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the cortex were measured using a modification of a previously published sandwich-ELISA protocol [23], with a pellet containing insoluble Aβ resuspended in 70% formic acid instead of TFA. Samples were incubated on ice for 30m, then centrifuged at 17,000g for 2h. Formic acid-soluble supernatant was separated and neutralized using 1M Tris (pH=11, 1:20, formic acid solution:Tris 1M) and stored at −20°C.

Immunofluorescence.

40μm-thick hemibrains were rinsed 5 times in 0.1% PBS-Triton for 5min. Nonspecific bindings were blocked using 20% normal horse serum in PBS-T for 1h at RT. For Aβ staining, antigen retrieval was conducted using incubation with 75% formic acid for 2min at RT. Abs for the following antigens were applied and incubated overnight at 4°C: Aβ (clone 4G8, 800701, Biolegend, 1:2000), Iba1 (019–19741, Wako, 1:1000), and CD68 (ab53444, Abcam, 1:2,500). Next, sections were rinsed five times in PBS-T for 5min, and fluorescence-tagged secondary Abs (AlexaFluor 488/568, Invitrogen) were applied for 1h at RT. Slices were then stained with Hoechst 33342 (H3570, Invitrogen) diluted at 1:1,000, followed by five 5-minute rinses with PBS-T.

Aβ Plaque size measurements.

The size of Aβ plaques in coronal sections located −2.055 and −2.55mm from Bregma was quantified computationally using blob detection tools in MATLAB (MathWorks). Small blobs, sized <80 μm2, were regarded as artifacts and were filtered out. Briefly, montage immunofluorescence images of the hippocampus and cortex were obtained using the x20 objective of a Leica DM6000 microscope (Leica Microsystems), coupled to a controller module, a high sensitivity 3CCD video camera system (MBF Biosciences), and an Intel Xeon workstation (Intel). Automated imaging was implemented using the Stereo Investigator software package (MBF Biosciences). Images were then loaded to a pre-validated plaque detection algorithm.

Quantification of microglial markers.

IF images of Iba1+, CD68+ microglia, and Aβ plaques were taken using the x40 objective. Hippocampi were outlined according to the Paxinos atlas of the mouse brain. Single-cell Iba1 and CD68 fluorescence intensity were filtered for noise and calculated using MATLAB (MathWorks).

Statistical analysis.

The data presented as mean ± SEM were tested for significance in one-way ANOVA, repeated measures (RM) two-way ANOVA, and Kruskal Wallis analysis. Post-hoc tests were conducted using the Tukey, Bonferroni, or Dunn corrections. All error bars represent SEM were calculated as for numeric variables. Outliers were identified using the robust regression and outlier removal (ROUT) method with coefficient Q=1% [24]. Significant results were marked according to conventional critical P-values: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Results

Priming at a young age improves anti-Aβ humoral response in aged WT mice.

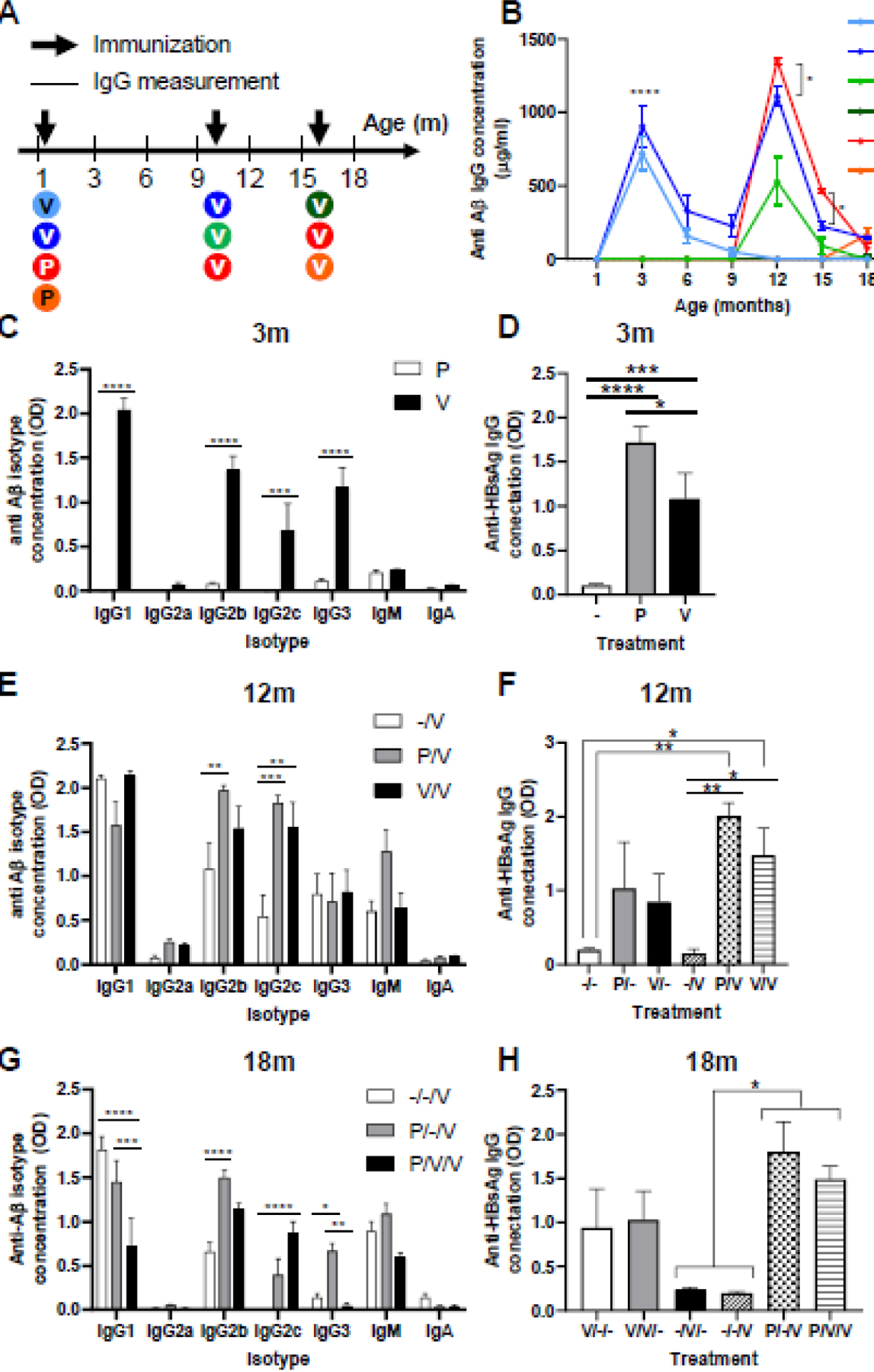

Achieving an adequate humoral immune response to vaccinations in the elderly is challenging due to immunosenescence [25], especially when immunizing against self-Ags [26], such as Aβ. To overcome this challenge, we hypothesized that induction of immune memory at an early age against HBsAg, a viral epitope, would promote an effective humoral immune response to vaccines expressing Aβ exposed on HBsAg at old age. To test this idea, we vaccinated WT male mice (n=5 males per experimental group) at 1, 10, and 16-month of age (Fig. 1A) with different combinations of AβCoreS vaccine (marked with V), HBsAg vaccine (priming vaccine, marked with P), or no vaccine (marked with -), using the gene-gun method. Baseline measurement revealed no anti-Aβ IgG in WT mice (Fig. 1B). As expected, P did not elicit anti-Aβ antibodies, unlike V (0±0 vs. 721.06±116.94, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 1B). Aβ-specific IgG levels decreased to baseline 3 months after vaccination (156±31, light-blue curve, 0±0µg/ml, green and light-green curves, respectively, P=0.2, Fig. 1B). The predominant IgG isotypes in vaccinated mice were IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, and IgG3, with no change observed in IgG2a, IgM, and IgA production (Fig. 1C). P produced a higher amount of anti-HBsAg antibody than V when immunized at 1m (P<0.05, Fig. 1D), potentially due to competition between Aβ and HBsAg epitopes. Following immunization with V at 10m, the humoral response was quantified at 12m. As expected, V/V/- mice elicited a higher antibody response than mice receiving a single vaccine dose (-/V/-) at 10m (1109.1±67.1, blue curve, 529.58±162µg/ml, light-green curve, respectively, P<0.0001 Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, P/V/V mice, which received priming with P at a young age and then re-immunized with V at 10m, generated a significantly higher levels of Aβ-specific IgG than V/V/- (1351.25±17.08, red curve, 1109.1±67.1µg/ml, blue curve, respectively, P<0.05, Fig. 1B), indicating that priming with a xenogenic vaccine carrier (P) can replace early immunization with AβCoreS (V). The P/V-strategy preferentially induced IgG2b response to Aβ compared with -/V (1.96±0.05 and 1.08±0.29OD, respectively, P<0.01, Fig. 1E) and IgG2c response to Aβ compared with -/V (1.82±0.08, 0.54±0.23OD, respectively, P<0.001, Fig. 1E). The V/V strategy also induced a high IgG2c response compared with -/V (1.54±0.28, 0.54±0.23OD, respectively, P<0.01, Fig. 1E), which was not statistically different from P/V (P=0.99, Fig. 1E). Both P/V and V/V vaccines induced a robust secondary anti-HBsAg response in 12m-old mice with no significant differences between them (P=0.31, Fig. 1F). However, -/V generated much less anti-HBsAg Abs than P/- and V/- (0.19±0.01, 1.71±0.17, 1.08±0.28OD, respectively, Fig. 1D, F), presumably suggesting that the mice show suppressed vaccine responses by 10–12m of age. Overall, these results suggest that priming with HBsAg at a young age and vaccinating later with AβCoreS can elicit higher titers of anti-Aβ Abs in older mice.

Fig. 1. Priming at an early age with the HBsAg vaccine facilitates anti-Aβ humoral response in aged WT mice.

(A) C57BL mice (n=5 males per group) were vaccinated at 1, 10, and 16 months of age with different combinations of the HBsAg priming (P) and Aβ1–11 vaccine (V) constructs. Blood was taken every three months for IgG measurement. (B) Anti-Aβ IgG levels throughout the experiment, arrows indicate vaccination time points. (C) Anti-Aβ IgG isotypes following the first vaccination (3m). (D) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the first vaccination. (E) Anti-Aβ IgG isotypes following the second vaccination (12m). (F) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the second vaccination. (G) Anti-Aβ IgG isotypes following the third vaccination (18m). (H) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the third vaccination. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, repeated measures two-way ANOVA, one-way ANOVA; data is presented as mean±SEM.

Next, we tested immunization at 15m. -/-/V only yielded minute-levels of Aβ-specific IgG that did not significantly differ from the background measurement (18.63±4.54, green curve, 0±0 µg/ml, green curve, respectively, P>0.99, Fig. 1B), reflecting that mice at this age are fully immunosenescent. In contrast, age-matched P/-/V mice produced higher Aβ-specific antibody (167.92±45.85, orange curve, 18.63±4.54µg/ml green curve, respectively, P<0.01, Fig. 1B), indicating that HBsAg response induced at a young age is sufficient to boost anti-Aβ vaccine response in aged mice. When immunoglobulin isotypes were tested at 18m, -/-/V and P/-/V elicited comparable high IgG1 levels than P/V/V (1.81±0.14, 1.45±0.24, 0.71±0.32OD, P<0.0001, P<0.001, respectively, Fig. 1G). However, P/-/V produced markedly more Aβ-specific IgG2b than -/-/V and more IgG3 than P/V/V (P<0.0001 and P<0.01, respectively, Fig. 1G). Interestingly, levels of anti-Aβ IgG2c were undetectable in -/-/V mice, demonstrating an aging-related reduction in the production of this Ig isotype (0.003±0.001OD, Fig. 1G). However, P/V/V vaccinated mice exhibit increased production of IgG2c compared with -/-/V (0.87±0.12, 0.003±0.001OD, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 1G). P/-/V mice also produced higher IgG2c levels than -/-/V; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.08, Fig. 1G). Nevertheless, P/-/V and P/V/V produced higher levels of anti-HBsAg IgG Abs compared with -/-/V (1.8±0.33, 1.49±0.15, 0.19±0.22OD, respectively, P<0.05, Fig. 1H). Thus, these results suggest that the induction of potent antibody response to self-antigens (Aβ) in middle-aged mice (see 12m, Fig. 1B) may impair the efficacy of a booster immunization in aged mice, presumably due to induction of tolerance. However, immunization with a xenogenic vaccine carrier (HBsAg) in young and then vaccination with AβCoreS in old (the strategy from hereon as termed as xeno-prime-boost) elicits high levels of Aβ-specific humoral response.

Priming at an early age facilitates anti-Aβ humoral response in adult 5xFAD mice.

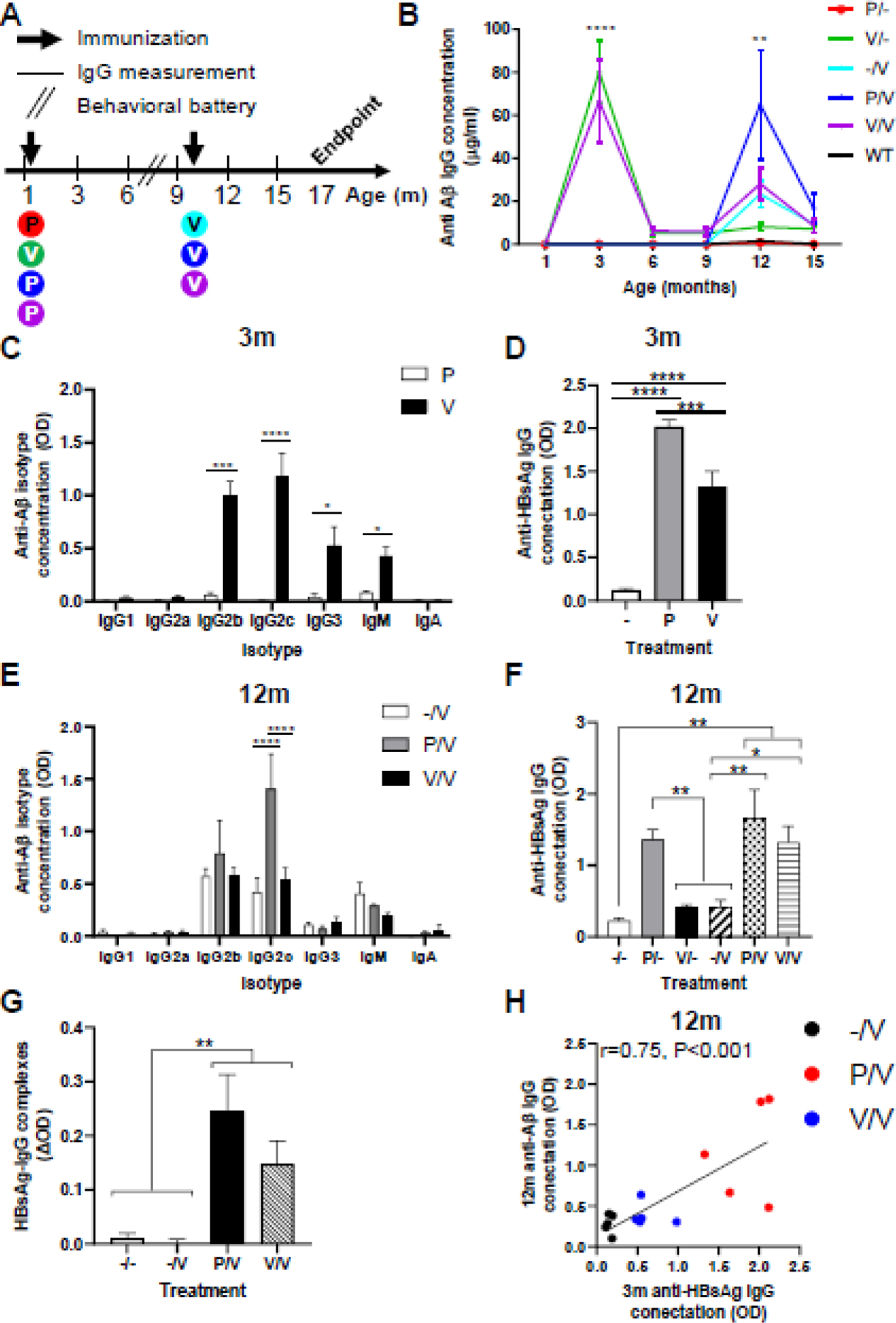

Although the human Aβ1–11 fragment of AβCoreS is homologous to murine Aβ (differs in amino acids R5G and Y10F), it could still be xenogeneic in WT mice. We therefore tested the efficacy of the xeno-prime-boost strategy in 5xFAD mice, which accumulates Aβ in the brain due to the overexpression of mutated human APP. 5xFAD mice at 1 and 10 months of age were DNA immunized as above but using the electroporator method (n=5, Fig. 2A). Baseline measurement taken at 1m of age indicated no anti-Aβ IgG presence in 5xFAD males (Fig. 2B). 3m-old V/- mice exhibited elevation in anti-Aβ IgG levels compared with P/- mice (80.1±14.58, green curve, 0±0µg/ml, red curve, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2B), which decreased to baseline within 3m following vaccination. V/- preferentially upregulated Aβ-specific IgG2b compared to P/- (0.99±0.14, 0.05±0.23OD, respectively, P<0.001, Fig. 2C), IgG2c (1.18±0.21, 0.003±0.001OD, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2C), IgG3 (0.52±0.17, 0.04±0.02OD, respectively, P<0.05, Fig. 2C), and IgM (0.42±0.08, 0.08±0.008OD, respectively, P<0.05, Fig. 2C). Compared to -/-, both P and V -immunized 1m-old mice produced anti-HBsAg IgG (2.09±0.08, 1.32±0.17, 0.12±0.01OD, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2D). As in WT, immunization with P again elicited a higher level of anti-HBsAg antibody than V (P<0.001, Fig. 1D). The -/V treated mice exhibited lower Aβ-specific IgG at 12m compared with V/- at 3m (23.33±6.03 cyan curve, 80.1±14.58, green curve, µg/ml, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2B), presumably reflecting either tolerance to self-antigens and/or age-related immunodeficiency. This response was not markedly increased in V/V mice (Purple curve, Fig. 2B), suggesting that the booster immunizations with the same vaccine do not improve impaired vaccine responses in aged hosts (66.63±19.27µg/ml at 3m and 28.14±7.55µg/ml at 12m, p<0.01, Fig. 2B). Importantly and as in WT mice, 12m P/V-vaccinated 5xFAD mice (i.e. P at 1mo and V at 10mo) produced higher titers of Aβ-specific IgG than V/V (64.92±25.53, blue curve, 23.33±6.03µg/ml, purple curve, respectively, P<0.01, Fig. 2B), implying that priming with xenogenic vaccine carrier can overcome a poor vaccine response to self-antigens. Indeed, IgG2c levels were higher in P/V vaccinated mice, compared with -/V mice (1.4±0.33, 0.43±0.13OD, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2E). Interestingly, IgG2c production was lower in V/V than in P/V mice (0.53±0.11, 1.4±0.33OD, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 2E), implying that repeated exposures to the AβCoreS construct do not favor the production of this Ig isotype in 5xFAD mice. As was also noted in aged WT mice (Fig. 1F), we did not detect an immunization-associated decrease of antibody to HBsAg in 12m mice (Fig. 2F), suggesting that unlike self-antigen (Aβ), the response to xenogenic antigens is unaffected at 12m mice.

Fig. 2. Priming at an early age with the HBsAg vaccine facilitates anti-Aβ humoral response in aged 5xFAD mice.

(A) 5xFAD mice (n=5 males per group) were vaccinated at 1 and 10 months of age with different combinations of the HBsAg priming (P) and Aβ1–11 vaccine (V) constructs. Blood was taken every three months for IgG measurement; a behavioral battery was conducted at 8m of age. (B) Anti-Aβ IgG levels throughout the experiment, arrows indicate vaccination time points. (C) Anti-Aβ IgG isotypes following the first vaccination (3m). (D) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the first vaccination. (E) Anti-Aβ IgG isotypes following the second vaccination (12m). (F) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the second vaccination. (G) Immune complex (IC) formation in the P/V and V/V groups, but not in -/- and -/V groups. (H) Anti-HBsAg IgG levels at 3m predict anti-Aβ IgG levels at 12m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, repeated measures two-way ANOVA, one-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation, linear regression; data is presented as mean±SEM.

To assess whether anti-HBsAg IgG Abs and the HBsAg particles form immune complexes (ICs) that could facilitate anti-Aβ Abs production at 12m, we treated sera for dissociation of ICs and re-measured anti-HBsAg IgG Abs. As expected, sera from P/V and V/V contained higher levels of HBsAg ICs compared with -/- and -/V (0.24±0.06, 0.14±0.04, 0.01±0.008, 0.0002±0.009 ΔOD, respectively, P<0.01, Fig. 2G). The immune response to HBsAg after immunization of young mice with P positively associated (i.e. predicted) with high anti-Aβ IgG response upon AβCoreS immunization in 12m mice (r=0.75, P<0.01, Fig. 2H), demonstrating the contribution of immune memory formation to a vaccine carrier in subsequent vaccine responses at an older age. Altogether, these data suggest that the xeno-prime-boost strategy prevents induction of tolerance to self-antigen-expressing vaccines (AβCoreS) and thereby helps to elicit high levels of Aβ-specific antibody in old hosts.

Vaccination with AβCoreS rescues a short-term memory impairment in 5xFAD mice.

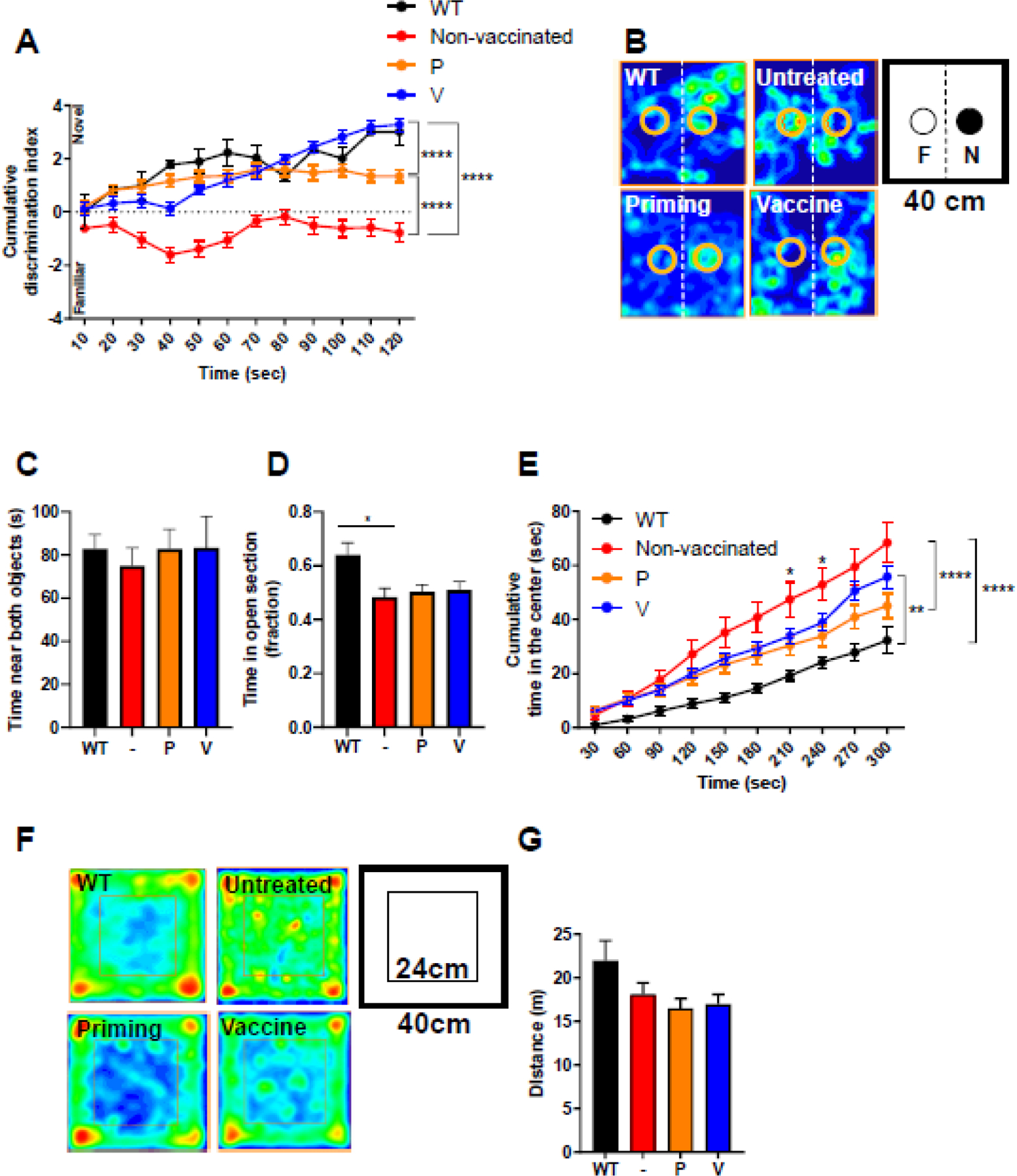

Because Aβ accumulation in the brain impairs short-term memory, we tested whether AβCoreS immunization reverses it, using the novel object recognition test in 5xFAD mice after symptoms onset (at 8m of age). AβCoreS-immunized (V) 5xFAD mice indeed exhibited a higher tendency to explore the novel object compared with untreated (3.28±0.25, −0.77±0.34 cumulative discrimination index, P<0.0001, respectively, Fig. 3A–B) and HBsAg-only-immunized mice (P) (3.28±0.25, 1.34±0.24 cumulative discrimination index, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 3A–B). Their performance did not differ from that of WT controls (3.28±0.25, 3.008±0.51 cumulative discrimination index, respectively, P=0.93, Fig. 3A–B), suggesting that AβCoreS restores an impaired short-term memory ability in 5xFAD mice. Interestingly, P-treated mice exhibited partial recovery of short-term memory abilities compared with unvaccinated 5xFAD controls (1.34±0.24, −0.77±0.34 cumulative discrimination index, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 3A–B), presumably due to alterations in microglial phenotype, mediated by non-Aβ IgGs, as was reported following the administration of the Influenza vaccine [27]. Additionally, influenza and pneumonia vaccines were recently associated with a lower prevalence of AD [28, 29]. This hypothesis is supported by a recent finding of NF-кB suppression by HBsAg, leading to downregulation of innate immune responses [30]. On the other hand, there was no difference in time exploring both objects between groups (P=0.94, Fig. 3C), suggesting no exploration-related confound. We also tested anxiety-like behavior using the elevated zero maze. 5xFAD mice tend to spend less time within the open anxiogenic section of the maze than WT mice (Fig. 3D), which was not reversed regardless of the vaccination state (P=0.88, Fig. 3D). However, untreated mice differed from WT mice, showing reduced time in the open section (0.48±0.03, 0.63±0.04 fraction of time in zone, respectively, P<0.05, Fig. 3D). Next, exploratory behavior and anxiety were assessed using the open-field test. WT mice exhibited lower time in the center of the arena, demonstrating the anxiety level of healthy mice (Fig. 3E–F). In contrast, untreated 5xFAD mice spent more time in the center than WT mice (68±7.31, 32.32±4.96s, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 3E–F), demonstrating reduced anxiety. P- and V-treated mice exhibited a partial correction of the anxiety threshold, although V-treated mice showed a non-significant improvement compared with P-treated mice (45.007±4.68, 55.85±4.23s, respectively, P=0.12, Fig. 3E–F). Walking distance did not differ between groups (P=0.12, Fig. 3G), implying that exploratory behavior is not impaired in 5xFAD mice.

Fig. 3. Vaccination with AβCoreS rescues short-term memory capacity in 5xFAD mice.

Cognition was tested in 5xFAD (n=10 for non-vaccinated, n=15 for P-treated, and n=17 for V-treated) and WT (n=5) mice at 8m of age. Vaccinated mice exhibit restoration of short-term memory in the novel object recognition (NOR) test, (A) Discrimination index in the NOR, (B) mice occupancy plot, and (C) total object exploration time. (D) Time in the open anxiogenic section of the elevated zero maze did not differ between groups. Exploratory behavior was assessed in the open field arena. (E) Time in the center of the arena, (F) mice occupancy plot, and (G) walking distance in the open field arena. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001, repeated measures two-way ANOVA; one-way ANOVA, data is presented as mean±SEM.

Early vaccine administration reduces Aβ42 levels in protein extracts from the 5xFAD mice’s cortex.

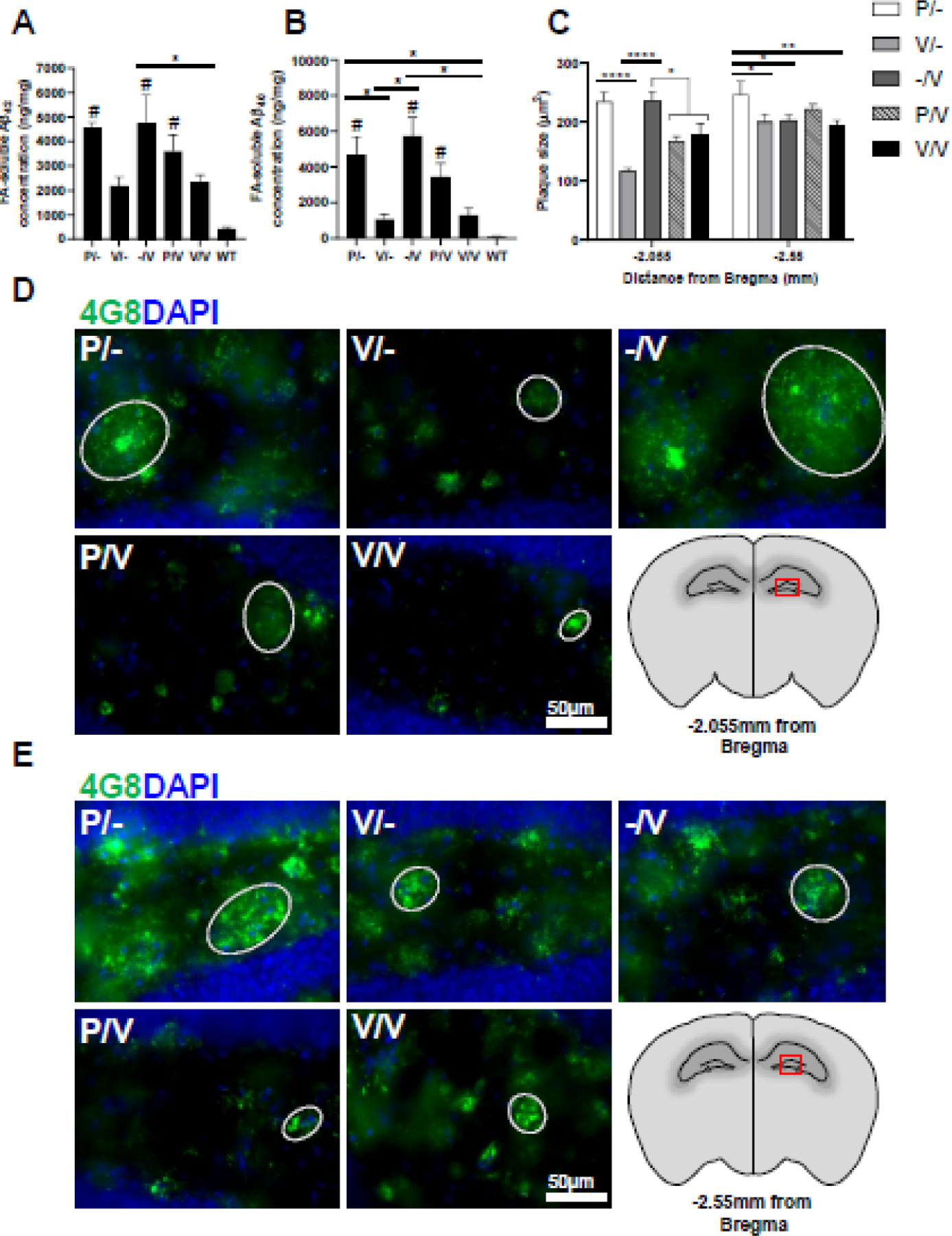

To assess the effect of vaccination timing on cerebral Aβ-related pathology, 5xFAD mice were sacrificed at 17m of age, and brain tissues were collected. Cortical Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were quantified using a modification of a previously described sandwich ELISA (sELISA) protocol [23] in insoluble (FA-soluble) protein extracts [31]. Consistent with the differential ability of AβcoreS to induce the generation of Aβ-specific Abs in young vs. old mice (Fig. 2B), immunization at a young age (V/-) markedly reduced cortical insoluble Aβ peptides, while -/V mice (vaccinated at old age) failed to do so, similarly to control P-treated mice (Fig. 4A, B). However, P/V-immunized mice showed a non-significant reduction in cortical insoluble Aβ peptides compared with -/V (Fig. 4A, B), suggesting that inefficient vaccine response in old mice can be reversed by vaccinating with a xenogeneic carrier. Compared with P-mice, the V/-, P/V, and V/V strategies markedly reduced insoluble Aβ42 in the cortex, with the V/- group exhibiting the most effective reduction (Fig. 4A). For insoluble Aβ40, elevated levels were observed in P/- compared with V/- vaccinated mice (P<0.05, Fig. 4B) and V/V vaccinated mice (1290±423.3ng/ml, P<0.05, Fig. 4B). Similarly, -/V also exhibited elevated insoluble Aβ40 compared with V/- and V/V early-vaccinated mice (P<0.05, Fig. 4B), suggesting that early anti-Aβ immunization is protective at 17m of age. Additionally, averaged plaque size in coronal sections located −2.055mm from Bregma was reduced as a result of the V/-, P/V, and V/V strategy, but not by the -/V strategy (Fig. 4C–D). In coronal sections located −2.55mm from Bregma, -/V, V/- and V/V strategies reduced averaged plaque size (Fig. 4C, E).

Fig. 4. Early vaccine reduces Aβ42 levels in protein extracts from the 5xFAD mice’s cortex.

5xFAD mice were sacrificed at 17m of age (n=5 males per group) to assess cerebral Aβ pathology. Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) were measured in the insoluble (FA-soluble) fraction of cortical protein homogenates using sandwich ELISA. Comparisons to a WT group are marked with #. (C) Hippocampus plaque size was measured in X20 microscope images of Aβ-labeled IF brain sections located at (D) −2.055 and (E) −2.55mm from Bregma. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.01, ****P<0.0001, # was used to indicate comparison to WT mice, in the same manner, Kruskal-Wallis test, one-way ANOVA; data is presented as mean±SEM.

Early HBsAg and late AβCoreS vaccinations mediate activation of plaque-adjacent microglia.

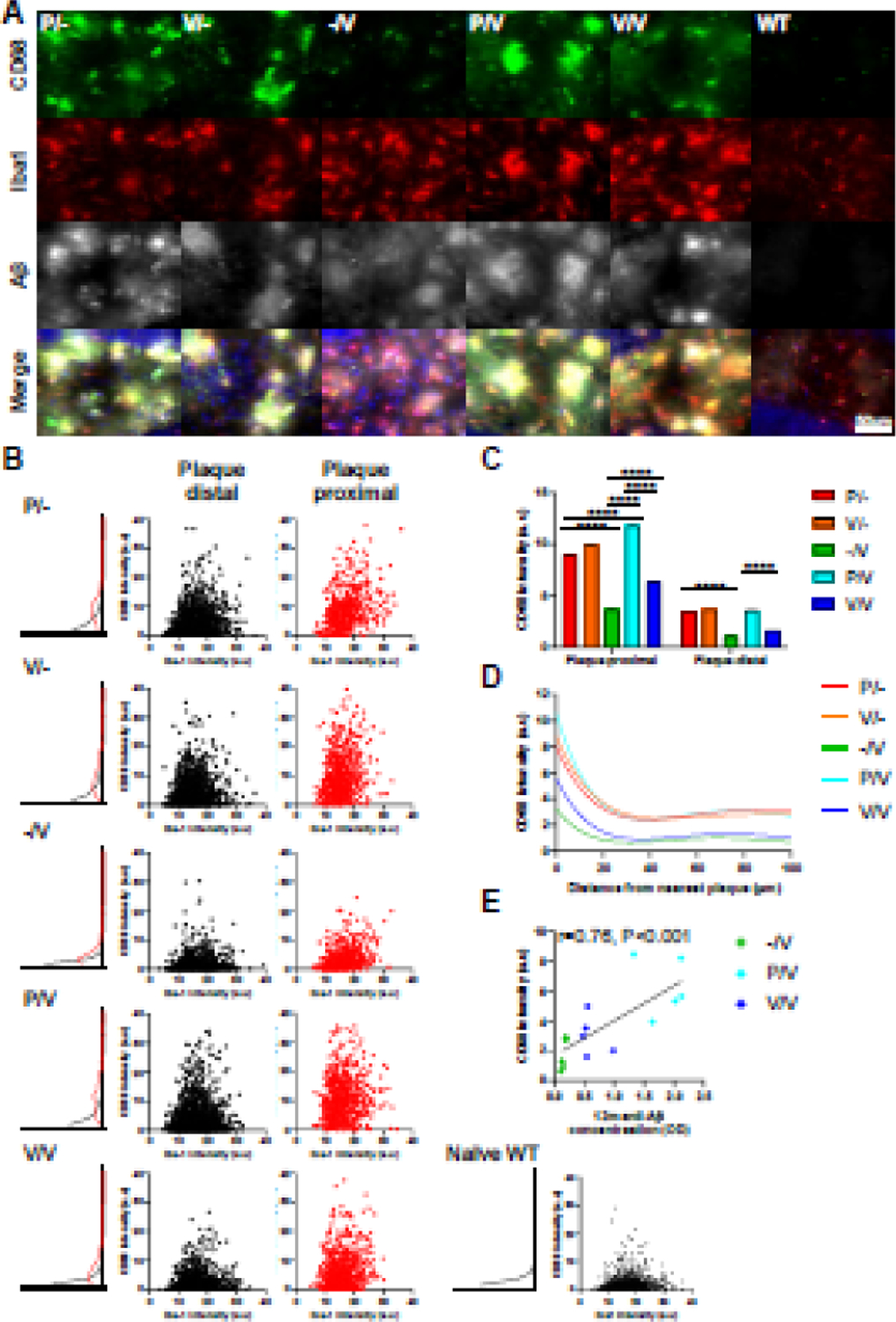

To further study the consequence of the AβCoreS vaccine administered at different ages with and without priming with the HBsAg construct, we conducted a quantification of microglial markers immunofluorescent signal (Fig. 5A–D). Total microglia were stained for Iba1, a pan-microglial marker, and for CD68, a lysosomal protein expressed in macrophages and activated microglia. Additionally, brain slices were stained for Aβ using the 4G8 antibody, and CD68 signal intensity was assessed as a function of microglial proximity from the nearest Aβ plaque. Proximal cells were defined as microglia within 0–1µm from the nearest plaque; all other cells were defined as distal microglia. Plaque-associated microglia exhibited a significant elevation in CD68 expression (CD68 signal intensity in arbitrary units – a.u) in all groups, compared with plaque-distal microglia (P<0.0001, Fig. 5A–C, Fig. S1), reflecting a higher activation state in these cells. CD68 expression was lower in proximal microglia from -/V treated mice compared with P/- mice (3.63±0.005, 8.92±0.012 a.u, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 5A–C), implying that vaccine administration at 10m is insufficient in activating microglial cells towards Aβ phagocytosis. However, mice vaccinated at 1m of age exhibited elevated expression of microglial CD68 (9.88±0.007, Fig. 5A–C). Furthermore, proximal microglia from P/V mice exhibited the highest CD68 expression compared with both P/- and -/V (11.75±0.007, 8.92±0.012, 3.63±0.005 a.u, respectively, P<0.0001, Fig. 5A–C), suggesting that early administration of HBsAg and a later vaccination with AβCoreS elicit a notable microglial activation. Lower CD68 expression was measured in V/V mice (6.33±0.005 a.u, P<0.0001, compared with P/V, Fig. 5A–C). Similar effects were observed in distal microglia (Fig. S1). Next, we modeled microglial activation using a six-order polynomial fit of CD68 intensity as a function of microglia proximity to plaques, and found a higher CD68 expression in plaque-adjacent microglia among all groups (Fig. 5D). While CD68 expression was lower in microglia from -/V and V/V vaccinated mice, the anti-Aβ IgG level at 12m positively correlated with microglial activation (r=0.76m P<0.01, Fig. 5E), implying Ab-mediate effect on microglia functionality. Altogether, these results suggest that early administration of HBsAg and a later vaccination with AβCoreS elicit microglial activation that may facilitate Aβ clearance.

Fig. 5. Early HBsAg and late AβCoreS vaccinations mediate activation of plaque-adjacent microglia.

CD68 expression levels of Iba+ cells were measured in triple-stained hippocampal sections labeled for Iba1, CD68, and Aβ. Iba+ cells were divided into plaque distal (1µm < distance from nearest plaque) and plaque proximal (1µm ≥ distance from nearest plaque). (A) Exemplar of plaque-associated hippocampal microglia stained for CD68 (green) and Iba1 (red), Aβ staining shown in white and cell nuclei in blue. (B) Scatter plot of Iba1 and CD68 expression in plaque-distal and plaque-proximal microglial cells and distribution of CD68 expression. (C) Averaged CD68 expression in Iba+ plaque distal/proximal cells. (D) CD68 expression as a function of microglia distance from the nearest plaque. (E) CD68 expression is associated with Anti-Aβ IgG level at 12m of age. Expression level presented as signal intensity in arbitrary units (a.u). Two-way ANOVA, ****P<0.0001; data is presented as mean±SEM.

Discussion

The poor humoral response to vaccines in the elderly can be improved by booster immunizations, which presumably overcome age-related immune dysfunction. Old age affects the number and diversity of T and B cells, Ig isotypes, and receptor repertoire leading to decreased humoral immune responses against new extracellular pathogens [1]. However, the frequency of memory/effector T cells increases with age [3]. This explains why the immune response to our DNA vaccine, which encodes HBsAg expressing Aβ1–11 [11] in C57BL/6J and 5xFAD mice, is drastically reduced after the age of 10m.

Here we tested an alternative strategy, such as whether induction of immunity to vaccine carrier can also enhance antibody response to self-antigen-expressing vaccine delivered at old age. Young mice were immunized with a DNA vaccine expressing HBsAg, and when mice became old, they were immunized with HBsAg vaccine expressing Aβ1–11. To our surprise, this strategy–Xeno-prime-boost–was superior even when compared with priming and boosting with the same antigen/vaccine, suggesting that induction of memory response to vaccine carrier at a young age can circumvent some dysfunctions of immunosenescent mice.

Unlike anti-Aβ Abs, which decreased to baseline by 3m following vaccination, the anti-HBsAg Abs were present in the sera for much longer, possibly due to higher immunogenicity of HBsAg to that of Aβ1–11. The presence of anti-HBsAg IgG Abs enabled the formation of ICs upon re-exposure to the HBsAg vaccine at an advanced age. Indeed, anti-HBsAg IgG levels following the first vaccination were predictive of anti-Aβ IgG production following the second vaccination.

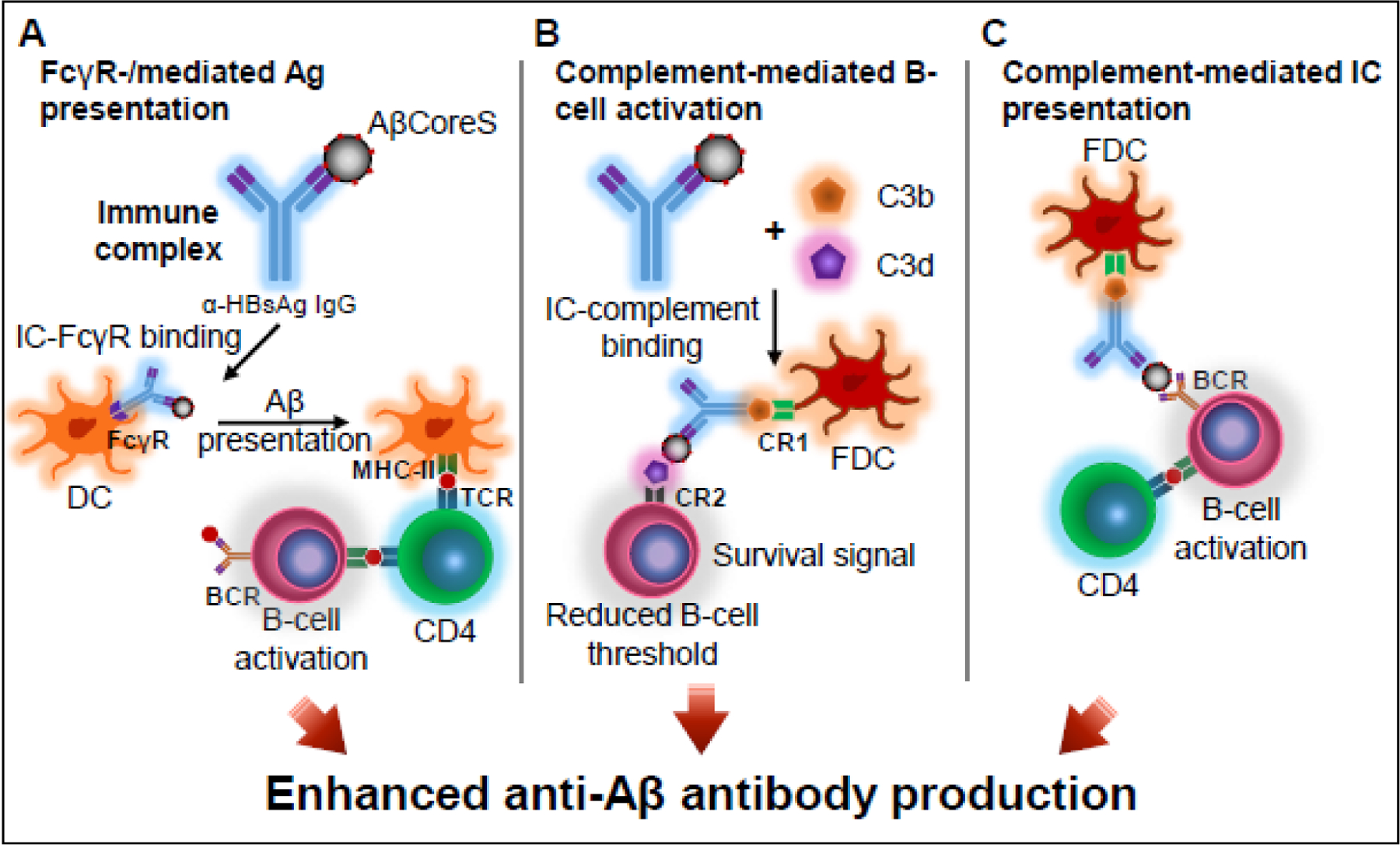

It appears that a long-term circulating anti-HBsAg Ab, or its ICs with the HBsAg, or/and induction of memory B and T cell response to vaccine carrier (HBsAg) were to enhance the anti-Aβ response. ICs yield a more potent secondary Ab response than Ag alone as they play a key role in the formation of germinal centers and stimulate memory formation with increased kinetics [32, 33]. In DCs, internalization of ICs following binding to FcγR leads to cell activation and increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules. In turn, this results in increased antigen-presentation ability that subsequently promotes Ab production (Fig. 6A) [34]. Senescence of innate immunity is characterized by impaired Ag presentation ability, featuring a lower expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and imbalanced cytokine secretion [1, 2]. Dendritic cells (DC) from aged individuals are impaired in their capacity to secrete TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-12 in response to TLR stimulation, implicated in the reduced humoral response to influenza vaccine [3]. Therefore, the presence of IgG-HBsAg ICs during the primary response to the Aβ vaccine may boost antigen presentation under innate-immunosenescence conditions (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Priming with HBsAg vaccine enhances primary response to AβCoreS at 12m of age and is associated with IC formation.

Proposed mechanisms for enhanced anti-Aβ IgG production observed following priming with HBsAg in otherwise immunosenescent mice. (A) Compared with a primary response, pre-existing anti-HBsAg IgG and newly introduced HBsAg particles form immune complexes (ICs). ICs bind to FcγR on dendritic cells to yield enhanced Ag presenting ability and subsequently higher Abs production. (B) Upon complement activation, C3b and C3d bind to ICs. C3b binds CR1 expressed on follicular DC (FDC), and C3d binds to CR2 on B cells, resulting in amplification of BCR signaling, reduced B cell activation threshold, and induction of a unique signal for B cell survival in the germinal centers, enhancing B cell response. (C) ICs bind to FDC via CR1 to present naïve antigen to germinal center B cells.

Additionally, ICs enhance the activation of complement cascade [35]. Upon C3 degradation, C3b participates in a transacylation reaction with nucleophilic groups present on ICs, and C3d interacts with Ags. Since complement receptor type 2 (CR2, CD21, C3d receptor) is part of the B cell co-receptor complex, complement activation amplifies BCR signaling, reduces the threshold for B cell follicular survival, and provides a unique signal for survival in the germinal centers, enhancing B cell response (Fig. 6B) [36–38]. Also, ICs bind to follicular dendritic cells (FDC) via CR1 to present naïve antigen to germinal center B cells (Fig. 6C) [38, 39]. By these mechanisms, the secondary response to HBsAg appears to potentiate the primary response to Aβ.

The AβCoreS vaccine restored short-term memory abilities in cognitively impaired mice to those observed in WT mice, in accordance with a previous report in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome, which expresses an additional copy of mouse APP [15]. However, we also noted a partial amelioration of short-term memory capacity in HBsAg-vaccinated compared with untreated mice (Fig. 3A). This might be explained by a shift in microglia gene-expression profile as viral processing pathway is enhanced in microglia from AD patients and is associated with HBV infections [40]. It is therefore possible that the HBsAg vaccine induces alterations in the microglial transcription profile. Microglia, the innate immune cells of the CNS, are heavily implicated in the pathogenesis of AD [41, 42], serving as a two-edged sword, as chronic pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype promotes disease progression and is hazardous to neurons. CD68, a heavily glycosylated type I transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in monocytes and tissue macrophages, belongs to the lysosome-associated membrane protein family and is indicative of phagocytic activity [43, 44]. In the brain, CD68 is mostly expressed in phagocytic microglia [45]. Here we showed that plaque-associated microglia express higher levels of CD68 and that mice immunized with the P/V strategy exhibit elevated CD68 expression. This finding suggests enhanced engagement of microglia from P/V mice in phagocytic activity. Furthermore, we have previously shown that maternal anti-Aβ vaccination increases the phagocytic activity of microglia, through activation of the FcγR/Syk/Cofilin pathway associated with increased cortical CD68 transcription and expression in microglia [46]. Indeed, immunization with the P/V combination yielded high plaque-associated microglial activation that may promote Aβ clearance. Interestingly, re-exposure to the AβCoreS vaccine did not elicit a similar effect, implying microglial tolerance to AβCoreS [47].

Late-onset AD (LOAD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects individuals aged 65 and above [48], characterized by the accumulation of extracellular Aβ deposits and intraneuronal hyperphosphorylated tau protein tangles [9, 49–51]. Our findings indicate that although the xeno-prime-boost strategy successfully overcomes age-related decline in response to a new Ag, Aβ clearance is significantly more evident in mice that received an early, pre-onset anti-Aβ immunization. The superiority of early interventions for AD lies in the fact that upon the emergence of clinical symptoms, a significant neuronal loss had already occurred [52]. Moreover, with the disease progression, the effect of immunotherapies may decrease, as microglia, among other cells, are exhausted [53]. Of note, the 5xFAD is a model of EOAD, in which the disease appears much earlier than the age-related reduction in antibody production. In human LOAD, on the other hand, both clinical signs and immunosenescence occur in the late stages of life. Thus, the xeno-prime-boost strategy is theoretically more suitable for the human course of disease and aging of the immune system than for those of mice.

Several other DNA vaccines that target Aβ were previously proposed to slow down disease progression in preclinical trials. For example, Qu and colleagues tested DNA vaccines encoding monomeric or trimeric full-length Aβ1–42 in conjunction with the Gal4/UAS or CMV system elements [54]. Xing and coworkers developed a DNA vaccine encoding ten tandem repeats of Aβ3–10 fused to mouse IL-4 [55]. Aiming to target a wide range of Aβ species, Matsumoto and colleagues tested the IgL-Aβx4-Fc-IL-4 (YM3711) vaccine consisting of Aβ repeats fused to human Fc portion of Ig and human IL-4 [56]. Davtyan and colleagues assessed the immune response in macaques and mice following vaccination with the AV-1955 vaccine [57] and its modified version AV-1959 [58]. AV-1955 and AV-1959 encode three copies of Aβ1–11, the pan DR-biding epitope (PADRE), and 8 or 11 promiscuous Th epitopes from various pathogens, respectively. Both of these constructs contain HBsAg [58–60]. Lambracht-Washington and colleagues compared the efficacy of vaccinating aged (18m) mice with an Aβ1–42 peptide vaccine and a trimeric Aβ1–42 DNA vaccine. The investigators also assessed the contribution of priming peptide-vaccinated mice with the DNA vaccine and priming DNA-vaccinated mice with the peptide vaccine. Their results indicate an increase of up to 17-fold in antibody production in peptide-vaccinated or primed mice, compared with DNA-vaccinated mice. The investigators found no difference in antibody titer between adult (8–10m) and aged (18–22m) DNA-immunized mice, raising the possibility that this construct overcomes immunosenescence [61]. However, since no vehicle control was tested, the increase in antibody production from baseline is unknown. Lambracht-Washington also reported that the full-length trimeric DNA vaccine produces a good antibody titer in New Zealand White rabbits [62] and rhesus macaques [63].

Indeed, vaccinating at an early age and maintaining functional levels of IgG Abs throughout the entire life may prevent the accumulation of Aβ before clinical signs emerge. However, lifelong exposure to autoantibodies (e.g. antibodies against Aβ) may induce autoimmune responses [64]. The HBV vaccine, on the other hand, is generally accepted by the medical and scientific communities as a safe vaccine [65], and is routinely in practice [66]. Therefore, priming with HBsAg at a young age combined with vaccination against a fused Aβ-HBsAg fragment at advanced ages will be a safer alternative for enhancing the humoral response in the elderly. Finally, the xeno-prime boost strategy may pave the route for potent and aging-tailored immunotherapies of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Exemplar of plaque-distal hippocampal microglia stained for CD68 (green) and Iba1 (red), Aβ staining shown in white and cell nuclei in blue.

Highlights.

Aged mice exhibit reduced production of Amyloid-β antibodies following vaccination.

Priming with a xenogenic vaccine carrier enhances anti-Amyloid-β humoral response.

A xeno-prime-boost vaccine strategy reduces cerebral Amyloid-β levels.

This strategy alters microglial phenotype in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yael Laure for editing this manuscript.

Funding Source

This study was conducted in the Paul Feder laboratory of Alzheimer’s disease research and was supported by the Clore Israel Foundation and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study and MATLAB codes are freely available upon request.

References

- [1].Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, et al. Immunosenescence and Its Hallmarks: How to Oppose Aging Strategically? A Review of Potential Options for Therapeutic Intervention. Frontiers in immunology 2019;10:2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology 2007;120:435–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Garcia D, Blomberg BB. B Cell Immunosenescence. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 2020;36:551–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dhinaut J, Chogne M, Moret Y. Immune priming specificity within and across generations reveals the range of pathogens affecting evolution of immunity in an insect. The Journal of animal ecology 2018;87:448–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang YW, Thompson R, Zhang H, Xu H. APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular brain 2011;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, et al. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nature structural & molecular biology 2010;17:561–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Illouz T, Okun E. No ECSIT-stential evidence for a link with Alzheimer’s disease yet (retrospective on DOI 10.1002/bies.201100193). BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 2015;37:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lansbury PT, Lashuel HA. A century-old debate on protein aggregation and neurodegeneration enters the clinic. Nature 2006;443:774–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2004;430:631–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rueda N, Florez J, Martinez-Cue C. Mouse models of Down syndrome as a tool to unravel the causes of mental disabilities. Neural plasticity 2012;2012:584071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Olkhanud PB, Mughal M, Ayukawa K, Malchinkhuu E, Bodogai M, Feldman N, et al. DNA immunization with HBsAg-based particles expressing a B cell epitope of amyloid beta-peptide attenuates disease progression and prolongs survival in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Vaccine 2012;30:1650–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhao Q, Wang Y, Freed D, Fu TM, Gimenez JA, Sitrin RD, et al. Maturation of recombinant hepatitis B virus surface antigen particles. Human vaccines 2006;2:174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, Laurent B, Puel M, Kirby LC, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology 2003;61:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gupta M, Dhanasekaran AR, Gardiner KJ. Mouse models of Down syndrome: gene content and consequences. Mamm Genome 2016;27:538–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Illouz T, Madar R, Biragyn A, Okun E. Restoring microglial and astroglial homeostasis using DNA immunization in a Down Syndrome mouse model. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2019;75:163–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci 2006;26:10129–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pyrski M, Rugowska A, Wierzbinski KR, Kasprzyk A, Bogusiewicz M, Bociag P, et al. HBcAg produced in transgenic tobacco triggers Th1 and Th2 response when intramuscularly delivered. Vaccine 2017;35:5714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Carvalho CA, Partata AK, Hiramoto RM, Borborema SE, Meireles LR, Nascimento N, et al. A simple immune complex dissociation ELISA for leishmaniasis: standardization of the assay in experimental models and preliminary results in canine and human samples. Acta tropica 2013;125:128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lueptow LM. Novel Object Recognition Test for the Investigation of Learning and Memory in Mice. J Vis Exp 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leger M, Quiedeville A, Bouet V, Haelewyn B, Boulouard M, Schumann-Bard P, et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nature protocols 2013;8:2531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shepherd JK, Grewal SS, Fletcher A, Bill DJ, Dourish CT. Behavioural and pharmacological characterisation of the elevated “zero-maze” as an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seibenhener ML, Wooten MC. Use of the Open Field Maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp 2015:e52434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Illouz T, Madar R, Griffioen K, Okun E. A protocol for quantitative analysis of murine and human amyloid-beta1–40 and 1–42. J Neurosci Methods 2017;291:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC bioinformatics 2006;7:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Crooke SN, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA, Kennedy RB. Immunosenescence and human vaccine immune responses. Immunity & ageing : I & A 2019;16:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Saupe F, Huijbers EJ, Hein T, Femel J, Cedervall J, Olsson AK, et al. Vaccines targeting self-antigens: mechanisms and efficacy-determining parameters. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2015;29:3253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yang Y, He Z, Xing Z, Zuo Z, Yuan L, Wu Y, et al. Influenza vaccination in early Alzheimer’s disease rescues amyloidosis and ameliorates cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting regulatory T cells. Journal of neuroinflammation 2020;17:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu JC, Hsu YP, Kao PF, Hao WR, Liu SH, Lin CF, et al. Influenza Vaccination Reduces Dementia Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine 2016;95:e2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ukraintseva S, Yashkin A, Duan M, Akushevich I, Arbeev K, Wu D, et al. Repurposing of existing vaccines for personalized prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: Vaccination against pneumonia may reduce AD risk depending on genotype. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2020;16:e046751. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Deng F, Xu G, Cheng Z, Huang Y, Ma C, Luo C, et al. Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Suppresses the Activation of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Pathway via Interaction With the TAK1-TAB2 Complex. Frontiers in immunology 2021;12:618196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Steinerman JR, Irizarry M, Scarmeas N, Raju S, Brandt J, Albert M, et al. Distinct pools of beta-amyloid in Alzheimer disease-affected brain: a clinicopathologic study. Archives of neurology 2008;65:906–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goins CL, Chappell CP, Shashidharamurthy R, Selvaraj P, Jacob J. Immune complex-mediated enhancement of secondary antibody responses. Journal of immunology 2010;184:6293–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. Germinal center initiation, variable gene region hypermutation, and mutant B cell selection without detectable immune complexes on follicular dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 2000;192:931–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Regnault A, Lankar D, Lacabanne V, Rodriguez A, Thery C, Rescigno M, et al. Fcgamma receptor-mediated induction of dendritic cell maturation and major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen presentation after immune complex internalization. The Journal of experimental medicine 1999;189:371–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hair PS, Enos AI, Krishna NK, Cunnion KM. Inhibition of Immune Complex Complement Activation and Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation by Peptide Inhibitor of Complement C1. Frontiers in immunology 2018;9:558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carroll MC. The complement system in B cell regulation. Molecular immunology 2004;41:141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Carroll MC. The role of complement in B cell activation and tolerance. Advances in immunology 2000;74:61–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kulik L, Laskowski J, Renner B, Woolaver R, Zhang L, Lyubchenko T, et al. Targeting the Immune Complex-Bound Complement C3d Ligand as a Novel Therapy for Lupus. Journal of immunology 2019;203:3136–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kranich J, Krautler NJ. How Follicular Dendritic Cells Shape the B-Cell Antigenome. Frontiers in immunology 2016;7:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mastroeni D, Nolz J, Sekar S, Delvaux E, Serrano G, Cuyugan L, et al. Laser-captured microglia in the Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s brain reveal unique regional expression profiles and suggest a potential role for hepatitis B in the Alzheimer’s brain. Neurobiology of aging 2018;63:12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2017;169:1276–90 e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 2017;47:566–81 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Korzhevskii DE, Kirik OV. Brain Microglia and Microglial Markers. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology 2016;46:284–90. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Walker DG, Lue LF. Immune phenotypes of microglia in human neurodegenerative disease: challenges to detecting microglial polarization in human brains. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 2015;7:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fu R, Shen Q, Xu P, Luo JJ, Tang Y. Phagocytosis of microglia in the central nervous system diseases. Molecular neurobiology 2014;49:1422–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Illouz T, Nicola R, Ben-Shushan L, Madar R, Biragyn A, Okun E. Maternal antibodies facilitate Amyloid-beta clearance by activating Fc-receptor-Syk-mediated phagocytosis. Communications biology 2021;4:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wendeln AC, Degenhardt K, Kaurani L, Gertig M, Ulas T, Jain G, et al. Innate immune memory in the brain shapes neurological disease hallmarks. Nature 2018;556:332–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2018;14:367–429. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Alhajraf F, Ness D, Hye A, Strydom A. Plasma amyloid and tau as dementia biomarkers in Down syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Dev Neurobiol 2019;79:684–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ghiso J, Tomidokoro Y, Revesz T, Frangione B, Rostagno A. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Hirosaki Igaku 2010;61:S111–S24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Goedert M NEURODEGENERATION. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Abeta, tau, and alpha-synuclein. Science 2015;349:1255555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wisniewski T, Konietzko U. Amyloid-beta immunisation for Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology 2008;7:805–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Streit WJ, Khoshbouei H, Bechmann I. Dystrophic microglia in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 2020;68:845–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Qu BX, Lambracht-Washington D, Fu M, Eagar TN, Stuve O, Rosenberg RN. Analysis of three plasmid systems for use in DNA A beta 42 immunization as therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Vaccine 2010;28:5280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xing X, Sha S, Li Y, Zong L, Jiang T, Cao Y. Immunization with a new DNA vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease elicited Th2 immune response in BALB/c mice by in vivo electroporation. Journal of the neurological sciences 2012;313:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Matsumoto Y, Niimi N, Kohyama K. Development of a new DNA vaccine for Alzheimer disease targeting a wide range of abeta species and amyloidogenic peptides. PloS one 2013;8:e75203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Evans CF, Davtyan H, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Hannaman D, et al. Epitope-based DNA vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease: translational study in macaques. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2014;10:284–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Cribbs DH, et al. The MultiTEP platform-based Alzheimer’s disease epitope vaccine activates a broad repertoire of T helper cells in nonhuman primates. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2014;10:271–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Davtyan H, Bacon A, Petrushina I, Zagorski K, Cribbs DH, Ghochikyan A, et al. Immunogenicity of DNA- and recombinant protein-based Alzheimer disease epitope vaccines. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2014;10:1248–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Harahap-Carrillo IS, Davtyan H, Antonyan T, Chailyan G, et al. Characterization and preclinical evaluation of the cGMP grade DNA based vaccine, AV-1959D to enter the first-in-human clinical trials. Neurobiology of disease 2020;139:104823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lambracht-Washington D, Rosenberg RN. A noninflammatory immune response in aged DNA Abeta42-immunized mice supports its safety for possible use as immunotherapy in AD patients. Neurobiology of aging 2015;36:1274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lambracht-Washington D, Fu M, Wight-Carter M, Riegel M, Rosenberg RN. Evaluation of a DNA Abeta42 Vaccine in Aged NZW Rabbits: Antibody Kinetics and Immune Profile after Intradermal Immunization with Full-Length DNA Abeta42 Trimer. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2017;57:97–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lambracht-Washington D, Fu M, Frost P, Rosenberg RN. Evaluation of a DNA Abeta42 vaccine in adult rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta): antibody kinetics and immune profile after intradermal immunization with full-length DNA Abeta42 trimer. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 2017;9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Suurmond J, Diamond B. Autoantibodies in systemic autoimmune diseases: specificity and pathogenicity. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015;125:2194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Geier MR, Geier DA, Zahalsky AC. A review of hepatitis B vaccination. Expert opinion on drug safety 2003;2:113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Das S, Ramakrishnan K, Behera SK, Ganesapandian M, Xavier AS, Selvarajan S. Hepatitis B Vaccine and Immunoglobulin: Key Concepts. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology 2019;7:165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Exemplar of plaque-distal hippocampal microglia stained for CD68 (green) and Iba1 (red), Aβ staining shown in white and cell nuclei in blue.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the findings of this study and MATLAB codes are freely available upon request.