Abstract

Salicylic acid (SA) acts as a signaling molecule to perceive and defend against pathogen infections. Accordingly, pathogens evolve versatile strategies to disrupt the SA-mediated signal transduction, and how plant viruses manipulate the SA-dependent defense responses requires further characterization. Here, we show that barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) infection activates the SA-mediated defense signaling pathway and upregulates the expression of Nicotiana benthamiana thioredoxin h-type 1 (NbTRXh1). The γb protein interacts directly with NbTRXh1 in vivo and in vitro. The overexpression of NbTRXh1, but not a reductase-defective mutant, impedes BSMV infection, whereas low NbTRXh1 expression level results in increased viral accumulation. Similar with its orthologs in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), NbTRXh1 also plays an essential role in SA signaling transduction in N. benthamiana. To counteract NbTRXh1-mediated defenses, the BSMV γb protein targets NbTRXh1 to dampen its reductase activity, thereby impairing downstream SA defense gene expression to optimize viral cell-to-cell movement. We also found that NbTRXh1-mediated resistance defends against lychnis ringspot virus, beet black scorch virus, and beet necrotic yellow vein virus. Taken together, our results reveal a role for the multifunctional γb protein in counteracting plant defense responses and an expanded broad-spectrum antibiotic role of the SA signaling pathway.

Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein impairs thioredoxin h-type 1 reductase activity and dampens downstream salicylic acid-related gene expression to facilitate viral cell-to-cell movement.

Introduction

Salicylic acid (SA) is a key hormone for plants to defend against biotrophic and semi-biotrophic pathogens (Ding and Ding, 2020; Zhao and Li, 2021). Upon pathogen invasion, redox status in plant cell changes and activates thioredoxins (TRXs). Consequently, NONEXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE 1 (NPR1), a master regulator of SA-mediated defense pathway (Cao et al., 1997), is translocated to nucleus where activates downstream defense genes expression in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Mou et al., 2003). Besides its role as transcriptional coactivator, NPR1 is also involved in a series of defense events such as callose deposition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and systemic-acquired resistance activation (Peng et al., 2021).

TRXs are ubiquitous, low-molecular mass proteins with two cysteines in their conserved active site WC(X)PC, which are involved in numerous biochemical processes in cells and widely distributed in plants, animals, bacteria, and yeasts (Mata-Pérez and Spoel, 2019; Kumari et al., 2021). The subcellular localization of TRXs isoforms varies greatly in organelles. Thioredoxin h-type proteins (TRXhs), which constitute the largest TRXs subfamily, are primarily distributed in the cytoplasm (Kang et al., 2019). In Arabidopsis, AtTRXh3 and AtTRXh5 are required for catalyzing the conversion of NPR1 oligomers to monomers and subsequent NPR1 translocation to nucleus (Tada et al., 2008). Besides the investigation on their roles in reducing the oxidized thiols in NPR1, AtTRXh5 also acts as a selective protein-S-nitrosothiol reductase and regulates SA-responsive genes expression in plant immunity (Kneeshaw et al., 2014). Importantly, NPR1 from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) differs from AtNPR1 on lacking the conserved residues for cytoplasmic oligomer-nuclear monomer exchange and SA-dependent transcriptional activation (Maier et al., 2011); thus, whether TRXhs in Nicotiana benthamiana function in SA signaling pathway is still unknown.

Given the essential role of SA in plant immunity, many pathogens-derived effectors have been identified to dampen SA-mediated immunity response via different strategies (Lorang et al., 2012; Mukaihara et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017; Qi et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2020; Medina-Puche et al., 2020). In terms of plant viruses, the C4 protein from the geminivirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus re-localizes from the plasma membrane to chloroplasts to disturb SA biosynthesis upon activation of defense (Medina-Puche et al., 2020). Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) replicase interacts with A. thaliana NAC domain transcription factor 2 (ATAF2) to suppress SA-related genes expression as a means to promote systemic virus infection (Wang et al., 2009). Also, SUMOylation of turnip mosaic virus Nuclear inclusion b protein suppresses the NPR1-mediated immune response via interactions with small ubiquitin-like modifier3 (Cheng et al., 2017). Although some progress has been made revealing the battle between plant viruses and SA defense pathway, more in-depth research remains to be done.

Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) is a positive-strand RNA virus containing three genome RNA segments designated RNAα, RNAβ, and RNAγ. RNAα and RNAγ are sufficient for viral replication in plants; RNAβ is required for virion assembly and movement process (Jiang et al., 2021). Recent advances give us a more complete understanding of the versatile roles of the γb protein in viral pathogenesis and the molecular interactions between the virus and the host. BSMV γb interacts with viral replicase αa to promote BSMV replication (Zhang et al., 2017), and interacts with movement protein triple gene block 1 (TGB1) to enhance viral cell-to-cell movement (Jiang et al., 2020). In addition, BSMV γb protein subverts autophagy-mediated antiviral defenses by impeding the interaction between autophagy key factors autophagy protein7 (ATG7) and ATG8 (Yang et al., 2018), suppresses the peroxisomal-derived ROS bursts by interacting with glycolate oxidase (Yang et al., 2018), inhibits host RNA silencing and cell death responses through protein kinase A (PKA)-like kinase-mediated phosphorylation (Zhang et al., 2018), and disrupts chloroplast antioxidant defenses by targeting NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase C (NTRC) (Wang et al., 2021) to facilitate virus infection. Intriguingly, we also found plant counter–counter–defense strategy as serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase STY46 interacts with and phosphorylates γb to defend against BSMV infections (Zhang et al., 2021).

In this study, we revealed that BSMV infection interferes with SA antiviral defenses pathway. The γb protein targets NbTRXh1 protein and suppresses SA-mediated plant resistance by weakening the NbTRXh1 reductase activity, thereby inhibiting downstream defense genes expression, such as pathogenesis-related gene 1 (PR1) and PR2, to optimize BSMV cell-to-cell movement. We also found that NbTRXh1 plays a general antiviral role against plant viruses within different genera. Our results reveal a role of the multifaceted γb protein in SA-mediated antiviral responses to BSMV infection, and these findings substantially deepen our understanding of co-evolutionary arms race between plant defenses and viral counter defense.

Results

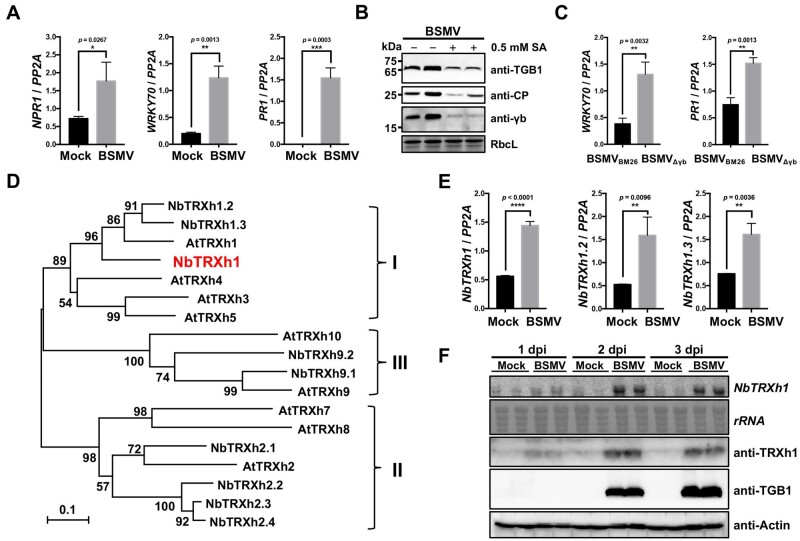

γb protein counteracts BSMV-induced SA defense responses

We previously found that SA signaling pathway respond to BSMV infections (Zhang et al., 2018). To systematically investigate the role of the SA-mediated defense pathway in BSMV infection, we measured the transcript level of SA-related marker genes during BSMV infections. These results showed that NPR1 (Cao et al., 1994), WRKY70 (Li et al., 2004), and PR1 (Alexander et al., 1993) transcripts were significantly upregulated in BSMV-infected N. benthamiana plants compared with those in mock-inoculated plants (Figure 1A). Moreover, 0.5-mM SA treatment dramatically decreases BSMV proteins accumulation (Figure 1B). These results suggest that BSMV infection activates SA antiviral defense pathway.

Figure 1.

BSMV γb suppresses the SA signaling pathway during viral infection. A, RT-qPCR analysis of the transcript levels of SA pathway-related genes in mock-inoculated or BSMV-infected N. benthamiana plants. The protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) gene was used as internal control. Values represent ± se of the mean from three biological replicates. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). B, Immunoblot analysis of BSMV-encoded proteins accumulation in N. benthamiana with or without 0.5-mM SA treatment. The antibodies used for western blot are shown on the right of the image. RbcL served as the loading control. C, RT-qPCR analysis of the transcript levels of SA pathway-related genes in BSMVBM26- or BSMVΔγb-infected N. benthamiana plants. Values represent ± se of the mean from three biological replicates. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test (**p < 0.01). D, Phylogenetic analysis of TRXh proteins from N. benthamiana (NbTRXh) and A. thaliana (AtTRXh). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbor-joining method, with the bootstrap analyses of 1,000 cycles. The TRXh proteins were divided into three major subgroups I, II, and III as indicated. Bar represents sequence divergence of 0.1 amino acids. E, RT-qPCR analysis of the transcript levels of NbTRXh1, NbTRXh1.2, and NbTRXh1.3 in mock-inoculated or BSMV-infected N. benthamiana plants. Values represent ± se of the mean from three biological replicates. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test (**p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). F, Time course analysis of the transcript level and protein accumulation of NbTRXh1 in mock-inoculated or BSMV-infected N. benthamiana plants by northern blot assay at 1 dpi, 2 dpi, and 3 dpi, respectively. Actin was used as the loading control. CP: coat protein.

Since γb protein is a determinant of BSMV pathogenesis (Donald and Jackson, 1994; Bragg et al., 2004), we posited that the activation of SA pathways maybe associated with γb protein. However, owing to the substantially decreased viral accumulation of BSMVΔγb mutant (remove the whole γb open reading frame; Zhang et al., 2017), compared with the wild-type virus (Supplemental Figure S1), the comparison of the two viruses cannot correctly reflect the effect of γb on SA stimulation. Instead, we used a BSMVBM26 mutant of which the viral accumulation is similar to that of BSMVΔγb (Supplemental Figure S1). BSMVBM26 mutant contains two basic motif mutations within γb (25RK26 → 25QN26) that abolish the RNA-binding activity (Donald and Jackson, 1996). BSMVBM26 or BSMVΔγb were inoculated into N. benthamiana by agroinfiltration and SA marker genes were analyzed by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR) at 3 dpi. The results showed that γb can suppress the SA defense pathway as verified by the remarkable downregulation of the transcript levels of WRKY70 and PR1 in BSMVBM26-infected N. benthamiana plants (Figure 1C). Altogether, these data indicate an additional role of γb in inhibition of virus-triggered SA defense responses.

BSMV infection upregulates NbTRXh1 expression

To investigate how γb disturbs SA defense pathway, we performed a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screen using BSMV γb protein as a bait against a mixed cDNA library from three Nicotiana species (N. tabacum, N. benthamiana, and N. glutinosa) plants as described previously (Zhang et al., 2021). N. benthamiana thioredoxin h-type 1 (NbTRXh1, GenBank accession: GQ354821) was identified as a potential γb-interactor. The full-length cDNA of NbTRXh1 was cloned based on the updated N. benthamiana genome database (https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:f34c90af-9a2a-4279-a6d2-09cbdcb323a2; Kourelis et al., 2019), and the amino acid sequence of TRXhs from N. benthamiana and A. thaliana were analyzed. These proteins shared a conserved motif WC(X)PC, while contained variable N- and C-terminus, suggesting that these proteins might execute versatile functions in plant cells (Supplemental Figure S2). Intriguingly, nine putative NbTRXh paralogs were identified from updated N. benthamiana genome data set (Kourelis et al., 2019; Table 1). Subsequently, we generated a phylogenetic tree including the N. benthamiana NbTRXhs and Arabidopsis AtTRXhs assigning corresponding names for NbTRXhs based on the AtTRXhs putative orthologs. NbTRXh1 are clustered into the same subgroup with AtTRXh1, AtTRXh3, and AtTRXh5 (Figure 1D). A previous study has demonstrated that AtTRXh3 and AtTRXh5 catalyze SA-induced NPR1 oligomer-to-monomer switch (Tada et al., 2008), alluding to the functional link of NbTRXh1 with SA defense pathway in N. benthamiana.

Table 1.

General information of NbTRXhs

| Gene name | Gene IDa | Type | CDSb (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NbTRXh1 | NbD046153.1 | I | 369 |

| NbTRXh1.2 | NbD034443.1 | I | 354 |

| NbTRXh1.3 | NbD029648.1 | I | 351 |

| NbTRXh2.1 | NbD052469.1 | II | 426 |

| NbTRXh2.2 | NbD015627.1 | II | 390c |

| NbTRXh2.3 | NbE03054613.1 | II | 408 |

| NbTRXh2.4 | NbD015628.1 | II | 420 |

| NbTRXh9.1 | NbD027853.1 | III | 456 |

| NbTRXh9.2 | NbD031089.1 | III | 417 |

The source where these IDs were taken.

Full-length coding sequence.

Partial sequence.

Subsequently, to elucidate whether BSMV infection upregulates the expression of NbTRXhs in subgroup I, the transcript levels of NbTRXh1, NbTRXh1.2, and NbTRXh1.3 were tested by RT-qPCR analyses. All the three genes were significantly upregulated in the context of BSMV infection (Figure 1E). Since the NbTRXh1 shares a high similarity with NbTRXh1.2 and NbTRXh1.3 (89.43%), we focused our further investigation on NbTRXh1. To elucidate the dynamics of the expression pattern of NbTRXh1 during BSMV infection, NbTRXh1 mRNA and protein levels were analyzed at 1-day post-inoculation (dpi), 2 dpi, and 3 dpi, respectively. The results showed that the expression of NbTRXh1 was induced as early as 1 dpi, reaching a maximum at 2 dpi, and maintaining a high level at 3 dpi (Figure 1F), suggesting that NbTRXh1 could respond to virus infection at an early stage.

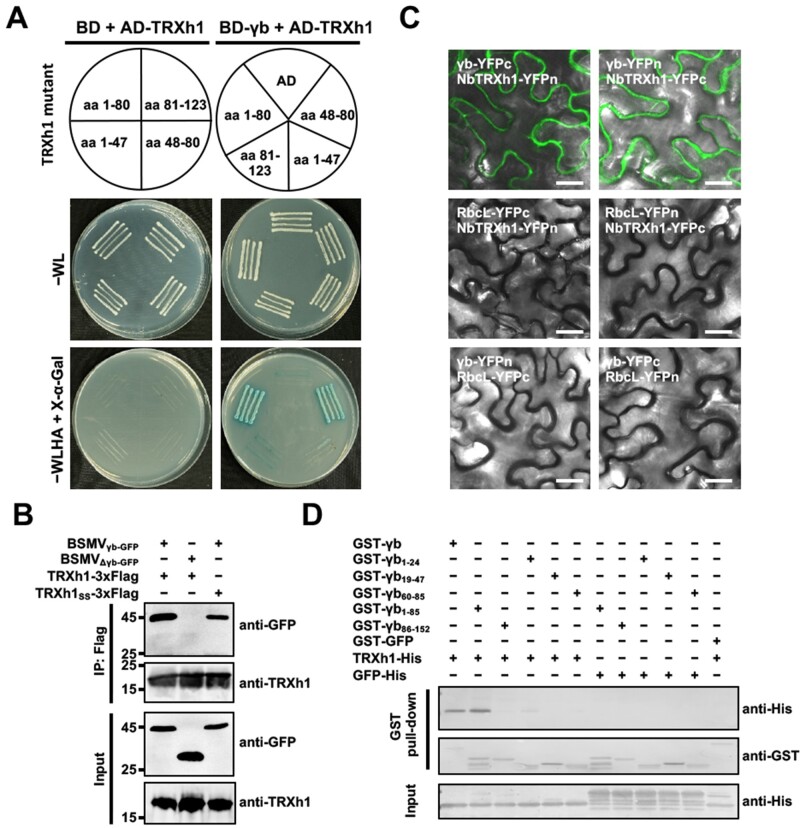

BSMV γb interacts physically with NbTRXh1

To confirm the results from the previous screen, Y2H assays were performed to test the interaction between γb and NbTRXh1. Despite the wild-type version of the NbTRXh1 protein failed to interact with γb, we found that a truncated mutant NbTRXh148–80, lacking the catalytic center, was sufficient to bind to γb (Figure 2A). To clarify whether the catalytic center (42WCGPC46) of NbTRXh1 is required for its interaction with γb, NbTRXh1-3xFlag or its enzymatic-defective mutant NbTRXh1SS-3xFlag (42WCGPC46 → 42WSGPS46) were expressed in BSMVγb-GFP or BSMVΔγb-GFP-infected N. benthamiana plants (Zhang et al., 2017). The co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) result showed that the γb-GFP co-precipitated with both NbTRXh1 and NbTRXh1SS proteins, but not with GFP alone (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

BSMV γb interacts with NbTRXh1. A, Y2H assay to investigate the interaction of γb with NbTRXh1 and its truncated mutant. B, Co-IP analysis to confirm the interaction between γb and NbTRXh1. Nicotiana benthamiana leaves infiltrated with different constructs were collected at 3 dpi. Total protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads and analyzed by western blot with anti-GFP and anti-TRXh1 antibodies. C, Bimolecular fluorescent complementation assay to test the in vivo interaction between γb and NbTRXh1 in N. benthamiana. The reconstructed YFP signal was visualized by confocal microscope at 3 dpi and depicted as a false-green color. RbcL-YFPn and RbcL-YFPc were used as negative controls. Bars, 20 μm. D, GST pull-down assay to analyze the in vitro γb and NbTRXh1 interaction. Purified GST-γb or a series of γb truncated proteins were incubated with NbTRXh1-His or GFP-His. After being immunoprecipitated with glutathione-sepharose beads, the proteins were detected by western blot with anti-His and anti-GST antibodies.

Next, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay was performed and the results showed that reconstructed YFP fluorescence signal appeared in N. benthamiana leaves co-infiltrated with γb-YFPc/NbTRXh1-YFPn and γb-YFPn/NbTRXh1-YFPc pairs, whereas the RuBisCo large subunit (RbcL, negative control) failed to interact with neither γb nor NbTRXh1 (Figure 2C). Protein accumulation was confirmed by western blot analysis (Supplemental Figure S3). Furthermore, we found that BSMV γb has no effect on the nucleo-cytoplasmic subcellular localization pattern of NbTRXh1 (Supplemental Figure S4).

To investigate the physical interaction between γb and NbTRXh1 in vitro, GST pull-down assay was carried out by using recombinant proteins purified from Escherichia coli. The results showed that NbTRXh1 was specifically pulled down by GST-γb and GST-γb1–85 truncated derivative, and a faint shadow was seen in γb1–24 truncation mutant lane, whereas other truncations of γb did not (Figure 2D). In addition, we further indicated that γbBM26 protein, a crucial control protein in this study, can also interact with NbTRXh1 in GST pull-down assay (Supplemental Figure S5). Collectively, these data suggest that γb physically interacts with NbTRXh1 in cytoplasm and the catalytic center of NbTRXh1 is not required for the interaction.

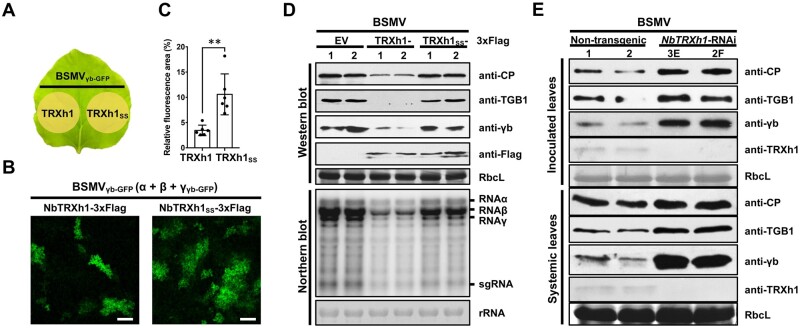

NbTRXh1 inhibits BSMV local and systemic infection in N. benthamiana

To understand the function of NbTRXh1 during BSMV infection, N. benthamiana leaves were co-infiltrated with Agrobacterium harboring a BSMVγb-GFP infectious clone and NbTRXh1-3xFlag or NbTRXh1SS-3xFlag (Figure 3A). At 3 dpi, the proportion of GFP-positive cells in the regions expressing NbTRXh1-3xFlag was significantly lower than that in the regions expressing NbTRXh1SS-3xFlag (Figure 3, B and C). Furthermore, viral proteins and RNA accumulations were substantially decreased in plants expressing NbTRXh1-3xFlag compared with those expressing NbTRXh1SS-3xFlag or empty vector (EV)-inoculated plants (Figure 3D), suggesting that the reductase activity of NbTRXh1 is essential to inhibit BSMV infection.

Figure 3.

NbTRXh1 reductase activity reduces BSMV accumulation in N. benthamiana. A, Schematic diagram of the half-leaf method used in Figure 3B. B, Effects of NbTRXh1-overexpression on BSMV infection. BSMVγb-GFP was agroinfiltrated into N. benthamiana together with TRXh1-3xFlag or TRXh1SS-3xFlag reductase-defective mutant. The GFP fluorescence indicates BSMV-infected cells and was photographed by confocal microscope at 2.5 dpi. Bars, 20 μm. C, Quantification of the GFP fluorescent area in Figure 3B by using ImageJ. Values represent ± se of the mean (n = 6). Data were statistically analyzed by Student’s t test (**p < 0.01). D, BSMV accumulation was detected by western and northern blotting in N. benthamiana leaves agroinfiltrated with EV, NbTRXh1-3xFlag, or NbTRXh1SS-3xFlag. Antibodies were shown on the right of the panel. Experiments were repeated twice. E, Western blot showing BSMV accumulation in nontransgenic or NbTRXh1-knockdown N. benthamiana plants. BSMV was agroinoculated. Local and systemic infected leaves were collected at 2 dpi and 6 dpi, respectively. Antibodies were shown on the right of the panel. Experiments were repeated three times. CP: coat protein; sgRNA: subgenomic RNA.

To confirm the anti-BSMV role of NbTRXh1, a short-hairpin RNA-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) vector (NbTRXh1-RNAi) was constructed, and then the stable transgenic N. benthamiana plants downregulating NbTRXh1 expression were generated. Intriguingly, compared with the nontransgenic plants, the NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic plants displayed leaf mosaic developmental phenotype and the accumulation of endogenous NbTRXh1 protein was almost undetectable in the two transgenic RNAi lines 3E and 2F analyzed (Supplemental Figure S6, A and B). Then, BSMV was inoculated to NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic and nontransgenic plants by agroinfiltration. The protein gel results showed that the accumulation of viral-encoded TGB1, coat protein, and γb proteins were increased in NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic plants compared with those in nontransgenic plants (Figure 3E), suggesting that NbTRXh1 negatively regulates BSMV infection.

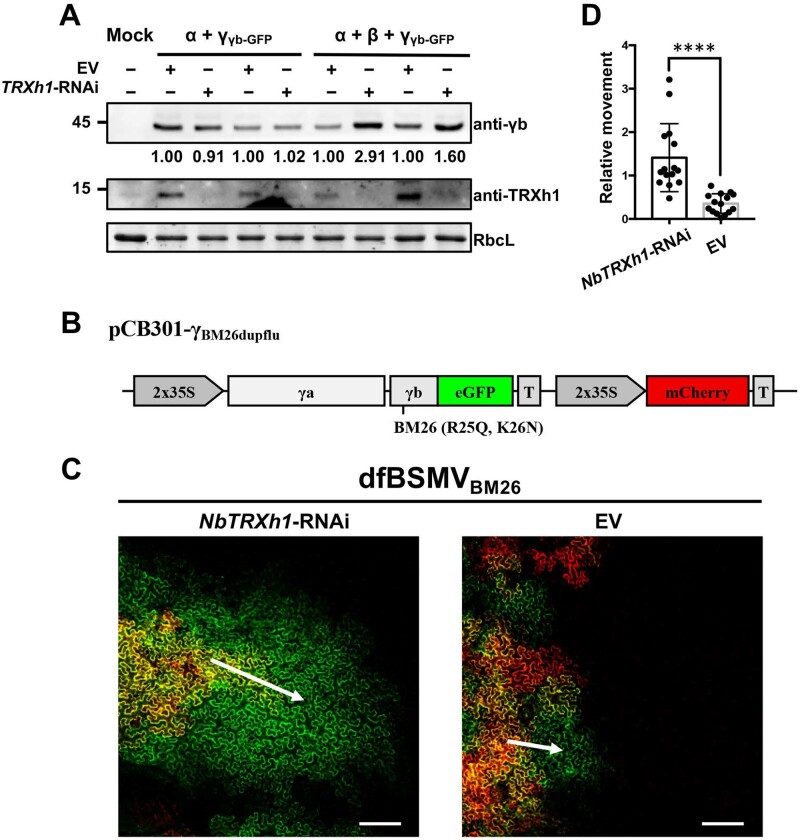

NbTRXh1 specifically suppresses BSMV cell-to-cell movement

To determine whether the BSMV replication or cell-to-cell movement were impeded by NbTRXh1, we inoculated BSMVγb-GFP (RNAα + RNAβ + RNAγγb-GFP) or its movement-deficient mutant (RNAα + RNAγγb-GFP, specifically initiate replication) into N. benthamiana plants which transiently overexpressed NbTRXh1-RNAi construct or EV using half-leaf method. The protein gel results showed that NbTRXh1 interferes with viral cell-to-cell movement instead of replication as evidenced by the similar accumulation of γb proteins in movement-deficient mutant virus-inoculated plants, whereas higher protein accumulation was detected in BSMVγb-GFP-inoculated NbTRXh1-RNAi plants (Figure 4A). Given that BSMV replicase αa recruits γb to chloroplasts replication sites for robust viral replication (Zhang et al., 2017; Jin et al., 2018), we also test the effect of NbTRXh1 on the interaction between γb and αa. The results showed that NbTRXh1 protein did not affect the stability of the γb–αa replication complex (Supplemental Figure S7), which is consistent with the lack of impact of NbTRXh1 on BSMV replication.

Figure 4.

NbTRXh1 inhibits specifically BSMV cell-to-cell movement. A, Western blot of BSMV accumulation in NbTRXh1-RNAi- or mock-inoculated N. benthamiana plants. Agrobacterium harboring the corresponding binary vectors were infiltrated into N. benthamiana plants by half-leaf method on the first day. BSMV RNAα and RNAγγb-GFP or BSMV RNAα, RNAβ, and RNAγγb-GFP were further inoculated into the previously agroinfiltrated leaves. Three days later, protein accumulation level of BSMV γb and endogenous NbTRXh1 was analyzed by using specific antibodies indicated on the right. RbcL was used as loading control. Experiments were repeated twice. B, Schematic representation of pCB301-γBM26dupflu used for the dfBSMVBM26 reporter system. C, Analysis of the effect of NbTRXh1 on BSMV movement. Images were captured at 2.5 dpi and the most representative images were displayed. The red signal shows primary agroinfiltrated area and the GFP signal outside the red region identifies secondary tissue invasion, which reflect the viral movement capacity. Bars, 200 μm. Arrows indicate the direction of viral cell-to-cell movement. D, Quantification of BSMV movement shown in Figure 4C. The areas of green and red fluorescence were measured by ImageJ software. To quantify the relative movement ability, the GFP only area was divided by the corresponding red fluorescent area, and the results were analyzed by Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001). Values represent ± se of the mean (n = 15). T: terminator.

Next, we further used BSMV duplex fluorescence (dfBSMV) reporter system (Li et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2020) to confirm the effect of NbTRXh1 on BSMV cell-to-cell movement. Since the viral suppressor of RNA silencing (VSR) activity of γb affects the silencing efficiency of hairpin RNA-mediated RNAi, a VSR-deficient dfBSMVBM26 mutant (pCB301-α + pCB301-β + pCB301-γBM26dupflu, Figure 4B) was co-infiltrated with NbTRXh1-RNAi construct or EV into N. benthamiana by using half-leaf method. The results revealed that the viral cell-to-cell movement was significantly enhanced in NbTRXh1-silenced leaves compared with EV-infiltrated leaves (Figure 4, C and D).

Altogether, these results indicate that NbTRXh1 interacts with γb targets, specifically the viral cell-to-cell movement phase, to inhibit BSMV infection.

NbTRXh1 has no distinct effect on VSR activity of γb

BSMV γb is a well-characterized VSR that is of vital importance in viral pathogenesis (Donald and Jackson, 1994; Bragg and Jackson, 2004; Jiang et al., 2021). To test if NbTRXh1 impairs the BSMV infection by interfering with γb VSR activity, NbTRXh1 was co-expressed with γb and a positive-sense GFP (sGFP; Zhang et al., 2018) in N. benthamiana leaves. At 3 dpi and 6 dpi, similar GFP fluorescence signal and GFP protein accumulation were observed in tissues expressing NbTRXh1 or EV (Supplemental Figure S8, A and B), demonstrating that NbTRXh1 does not affect VSR activity of γb protein.

A previous work has shown that NbTRXh2 (renamed as NbTRXh9.2 in Figure 1D) targets Bamboo mosaic virus (BaMV) TGB2 protein in N. benthamiana, which results in a restricted BaMV movement (Chen et al., 2018). Together with our results, we speculate that the molecular mechanisms of NbTRXh1-mediated antiviral defense might not directly compromise the pro-viral functions of the γb protein per se, but rather a plant antiviral defense process.

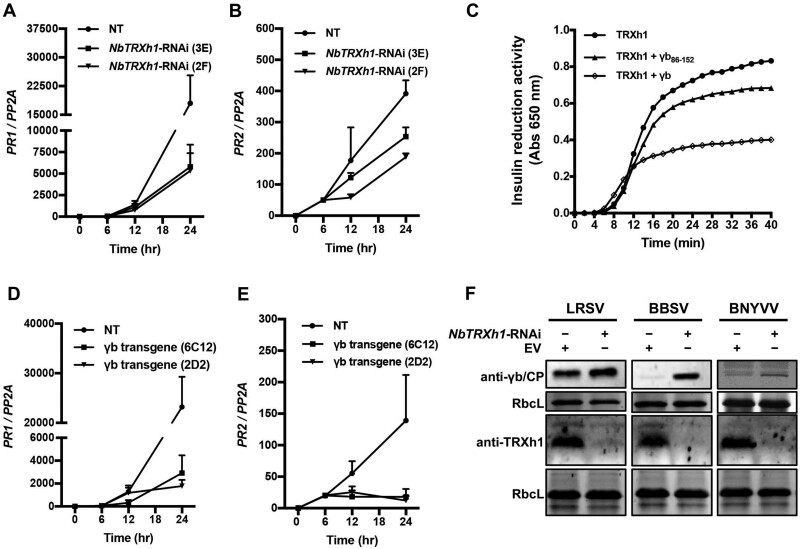

γb diminishes SA antiviral pathway via suppressing NbTRXh1 reductase activity

Since the reductase activity of NbTRXh1 is required for an antiviral strategy against BSMV (Figure 3, B and D), we hypothesized that anti-BSMV role of NbTRXh1 might be functionally linked with SA-mediated defense in N. benthamiana. To verify whether NbTRXh1 is involved in SA-mediated signaling pathway, six-leaf stage of NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic or nontransgenic N. benthamiana plants were treated with 0.5-mM SA. The results showed that the transcript levels of PR1 and PR2 were substantially decreased in NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic plants, indicating that NbTRXh1 is involved in SA-mediated defense pathway (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

γb interferes with NbTRXh1-mediated defense. A and B, NbTRXh1 is involved in SA defense pathway in N. benthamiana plants. Total RNA was extracted for RT-qPCR analysis of transcript levels of PR1 and PR2 in NT and NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic (lines 3E and 2F) N. benthamiana plants after 0.5-mM SA treatment at 0 hpi, 6 hpi, 12 hpi, and 24 hpi, respectively. Values represent the average of three independent experiments, and error bars indicate se. C, γb compromises NbTRXh1 reductase activity. A 20-μM NbTRXh1 protein was used in this assay and insulin reduction activity was measured by reading absorbance at 650 nm. Experiments were performed thrice with similar tendency. D and E, γb suppresses the expression of NPR1 downstream defense genes. Total RNA was extracted for RT-qPCR analysis of transcript levels of PR1 and PR2 in NT and γb-transgenic N. benthamiana plants (lines 6C12 and 2D2) upon 0.5-mM SA treatment at 0 hpi, 6 hpi, 12 hpi, and 24 hpi, respectively. Values represent the average of three independent experiments, and error bars indicate se. F, Western blot analysis of LRSV γb, BBSV CP, and BNYVV CP proteins accumulation in NbTRXh1-silenced or empty vector (EV)-inoculated N. benthamiana plants at 3 dpi. RbcL was used as loading control. Experiments for each viral protein were repeated at least twice. NT: nontransgenic.

Next, we performed an in vitro insulin reduction assay (Holmgren, 1979) and the result showed that the recombinant NbTRXh1-His possesses reductase activity in vitro as evidenced by substantially increased absorbance values over time (Supplemental Figure S9). To verify whether γb subverts the SA defense pathway by disturbing the enzymatic activity of NbTRXh1, the reductase activity of recombinant NbTRXh1-His were measured in the presence of GST-γb or GST-γb86–152 (a mutant that abolish NbTRXh1 binding capacity) proteins (Supplemental Figure 10). As expected, the result showed that the full-length γb protein, but not γb86–152, can suppress the NbTRXh1 reductase activity in vitro (Figure 5C).

Previous studies showed that the reductase activity of AtTRXh3 and AtTRXh5 orchestrate the PR gene expression to initiate plant defense in Arabidopsis (Kinkema et al., 2000; Tada et al., 2008). To further investigate whether γb affects the SA downstream defense genes expression, the γb-transgenic N. benthamiana plants (Yang et al., 2018) were treated with 0.5-mM SA and the transcript levels of PR1 and PR2 were analyzed at 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h after treatment. The RT-qPCR results showed that γb dramatically inhibited the SA downstream defense genes expression (Figure 5, D and E).

Together, these data suggest that γb can compromise the SA downstream defense genes expression by directly inhibiting NbTRXh1 reductase activity.

NbTRXh1-mediated defense responses against diverse plant viruses

To investigate whether NbTRXh1-mediated defense responses may be shared among members of highly diverged classes of plant viruses, we selected lychnis ringspot virus (LRSV, genus Hordeivirus; Jiang et al., 2018), beet black scorch virus (BBSV, genus Betanecrovirus; Wang et al., 2018), and beet necrotic yellow vein virus (BNYVV, genus Benyvirus; Jiang et al., 2019) to test the effect of NbTRXh1 on these viruses infections in NbTRXh1-RNAi construct- or EV-infiltrated N. benthamiana by half-leaf method. The results showed that the accumulation of these viruses increased in NbTRXh1-silenced half-leaves compared with those EV-inoculated one (Figure 5F). Intriguingly, previous studies has shown that the CaTRXh1-cicy suppresses the geminivirus infection in pepper (Capsicum annuum; Luna-Rivero et al., 2016), the NtTRXh3 protein also negatively regulates TMV and cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) infection in N. tabacum (Sun et al., 2010), the NbTRXh2 inhibits BaMV cell-to-cell movement in N. benthamiana (Chen et al., 2018); together with our results, we suggest that h-type TRXs have general roles to defend against both RNA and DNA virus infections in planta.

Discussion

To successfully establish infections, pathogens have to battle with host defense system all the time. SA defense signaling pathway is one of the most important part of the plant immunity network to defend against biotrophic and hemi-biotrophic pathogens (Ding and Ding, 2020). Most plants maintain low SA levels during normal growth and development; however, upon pathogen infection, SA is rapidly synthesized via two independent pathways through phenylalanine ammonia lyase and isochorismate synthase; subsequently, NPR1, NPR3, and NPR4 perceive SA concentration changes and activate plant immunity (Peng et al., 2021). In this study, we found that BSMV infection activate SA defense pathway in N. benthamiana; exogenous SA treatment substantially inhibits BSMV accumulation (Figure 1). These results indicate that SA defense pathway is also involved in plant to defend against BSMV.

Upon recognition of pathogens, TRXs proteins sense the cytosolic redox status change and quickly switch the NPR1 oligomers-to-monomers (Tada et al., 2008); then, the monomers will be transported into nucleus and act as transcriptional coactivators to initiate downstream defense genes expression (Kinkema et al., 2000). Therefore, TRXhs-catalyzed NPR1 nuclear translocation process is an essential step in the SA defense pathway. Owing to the important role of TRXhs in plant immune system, several bacterial and fungal effectors have been identified to hijack TRXhs to evade plant defense system. For example, Ralstonia solanacearum employs an effector protein, RipAY, which exploits cytosolic TRXh proteins for self-activation and subsequent suppression of pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (Mukaihara et al., 2016). A necrotrophic pathogen, Cochliobolus victoriae, confers host susceptibility by hijacking a TRXh5-dependent NB-LRR resistance pathway (Lorang et al., 2012). Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae effector Xanthomonas outer protein I (XopI) disrupts NPR1-mediated resistance via proteasomal degradation of OsTRXh2 in rice (Oryza sativa; Ji et al., 2020). Likewise, in our study, we also found that viral encoded proteins could subvert TRXh-mediated plant defense. We provide direct evidences to indicate that NbTRXh1 inhibits BSMV infection through its reductase activity (Figures 3 and 4); more importantly, BSMV γb directly interacts with NbTRXh1 to weaken its reductase activity and optimize BSMV infection performance (Figures 2 and 5). Since NbNPR1 differs from AtNPR1 (Maier et al., 2011), whether NbTRXh1 is functionally linked to NbNPR1 and how NbTRXh1 regulates the SA signaling transduction need to be further investigated.

Replication and movement are two important steps on viral infection (Heinlein, 2015). To survival, plants have evolved versatile defense strategies to impair viral replication and/or movement phase. Several studies found that SA hormone has defense roles in both viral replication and movement stages. For example, SA treatment interferes with TMV RNA accumulation by cell-type-specific effects on TMV replication and movement (Chivasa et al., 1997) (Murphy and Carr, 2002); in addition, SA inhibits the binding of cytosolic glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein to the negative RNA strand of tomato bushy stunt virus, thereby suppressing viral replication (Tian et al., 2015). In this study, we provide direct evidence to show that BSMV γb protein targets NbTRXh1 to block SA signaling transduction, which in turn specifically optimize viral cell-to-cell movement phase (Figure 4), indicating a negative role of SA in BSMV cell-to-cell movement. Since SA is a crucial molecular signal in the regulation of callose biosynthesis and deposition at plasmodesmata (PD; Zavaliev et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2021) as well as pathogen-induced PD closure, it is possible that NbTRXh1 inhibits the BSMV intercellular movement via SA-mediated PD closure but this needs further investigation. Considering distinct movement patterns for the same virus in monocot and dicot plants (Lawrence and Jackson, 2001), future research should also include whether homologous TRXh1 proteins function in the same way to block BSMV cell-to-cell movement in monocot plants. Our results also demonstrate that NbTRXh1 reduces the accumulation of some other RNA viruses such as LRSV, BBSV, and BNYVV (Figure 5F). Although the specific infection process in which NbTRXh1 participates remains unclear, it suggests that TRXs could be a potential targets hijacked by different plant viruses. This study reveals that BSMV γb protein promotes viral movement in N. benthamiana via dampening the key plant SA defense pathway; however, whether other plant viruses also encode γb-like proteins to subvert these signaling pathways are still unclear.

Strikingly, we recently identified a NTRC involved in chloroplast antioxidant defense responses to disturb BSMV replication at chloroplasts replication sites (Wang et al., 2021). Intriguingly, the NTRC protein contains a thioredoxin domain (Trx-D) at its C-terminus, which also plays a negative role in BSMV replication when fused with a chloroplast transit peptide. Given that TRXs and Trx-D-containing proteins are also widely distributed in different organelles of the cell, such as chloroplasts, mitochondria, etc. (Mata-Pérez and Spoel, 2019; Kumari et al., 2021), and which usually are co-opted by different viruses at viral replication sites (Netherton and Wileman, 2011), it opens a question whether other TRXs or Trx-D containing proteins also have similar antiviral functions in plant defense system.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The BSMV-related plasmids used in this study were described previously (Zhang et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2020).

Full-length coding sequence (CDS) of NbTRXh1 was amplified from cDNA of N. benthamiana and cloned into different expression vectors. Briefly, NbTRXh1 was amplified by specific primers TRXh1-F and TRXh1-R, and inserted upon pET-30a plasmid digestion using same restriction enzymes for insulin reduction activity assay. For BiFC assay, the CDS of TRXh1 was amplified with TRXh1-F2 and TRXh1-R2 containing BamHI and XhoI sites and inserted into pSPYCE and pSPYNE digested with the same restriction enzymes. For co-IP assay, the CDS of TRXh1 was amplified with TRXh1-F3 and TRXh1-R3 containing BamHI and SpeI sites and inserted into pMDC32 to generate pMDC32-TRXh1-3xFlag. For pull-down assay, the full-length CDS of TRXh1 were amplified by corresponding primers with BamHI and XbaI sites and inserted into pMAL-c2x to generate prokaryotic expression vectors.

For TRXh1SS mutant, site-directed mutagenesis with TRXh1SS-F and TRXh1SS-R primers were used to generate TRXh1SS sequence and then inserted into different vectors (the same restriction enzymatic sites with TRXh1). To generate a plasmid construct that exogenously expresses hairpin RNAs targeting NbTRXh1, the gene-specific insert was constructed to transcribe a hairpin structure consisting of a 233-bp sequence from the target transcript with a spacer of 234 bp of random sequence for the hairpin loop, followed by the reverse complement of the original 233 bp. The fragment was integrated into pSK-In vector at KpnI/SalI and PstI/SpeI sites, respectively, and then the fragments containing the forward and reverse NbTRXh1 sequences were amplified and inserted into pMDC32 vector at KpnI and SpeI sites.

All the primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplemental Table S1, the correctness of all the plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Insulin reduction assay

The full-length CDS of NbTRXh1 was cloned into pET-30a to obtain purified NbTRXh1-his recombinant protein. The recombinant protein was used to perform insulin reduction assay as described previously with little modification (Holmgren, 1979). Briefly, different amounts of NbTRXh1 fusion proteins were added to the reaction buffer containing 25-mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 1-mM EDTA, 200-μM bovine insulin, and 0.5-mM DTT. The reduction activity was monitored at 650 nm at room temperature by using a spectrophotometer.

Northern blotting

Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 2017). Approximately 15-μg RNA and 4-μg RNA were loaded for endogenous NbTRXh1 gene hybridization and viral RNA hybridization, respectively.

Pull-down assay

Approximately 3-μg protein was incubated in binding buffer [25-mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.7), 150-mM NaCl, 0.2% (v/v) glycerol, 0.6% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1x cocktail (Roche, Cat. # 11697498001)] containing 30-μL GST beads in a total volume of 600 μL. After 3-h incubation at 4°C, beads were centrifugated and washed with washing buffer [20-mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.7), 250-mM NaCl, 0.2% (v/v) glycerol, 0.6% (v/v) Triton X-100] at 4 for six times. Then sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) loading buffer was added and the beads were boiled for 10 min before subjected to western blotting.

Agroinfiltration

All binary vectors used were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 as described previously (Cao et al., 2015). In transient expression assays, suspensions of Agrobacterium carrying NbTRXh1 or its mutant constructs were infiltrated at optical density (OD)600 = 0.5. For hairpin RNA-mediated RNA interference approaches, the Agrobacterium harboring the NbTRXh1-RNAi construct was infiltrated at OD600 = 0.5. For co-IP, Agrobacterium containing each construct were infiltrated at OD600 = 0.4. For BSMV and LRSV inoculation, the OD600 of Agrobacterium containing each RNA segment is 0.3. For BBSV inoculation, the OD600 of the inoculum was 0.3; and for BNYVV RNA1, RNA2, and RNA4 is 0.05 for each construct.

BiFC assays

BiFC assays were carried out as described previously (Jiang et al., 2020), the samples were harvested and observed with a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope at 3 dpi. YFP signals were excited at 514 nm.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

The leaf samples were observed with a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope. GFP, YFP, and mCherry were visualized at 488 nm, 514 nm, and 543 nm, respectively. A line sequential scanning mode was used for image capture at a 1024 × 1024 pixel resolution. The value of gains was set to 600–900.

Co-IP assays

Co-IP assays were performed as described previously (Jiang et al., 2022). Briefly, plant tissue expressing different proteins was collected at 3 dpi and extracted in extraction buffer [25-mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150-mM NaCl, 1-mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1protease inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Cat. # 11697498001), 10-mM dithiothreitol]. The crude extracts were centrifuged at 8,000g for 30 min and the supernatants were collected and incubated with FLAG beads (Sigma). After 4-h incubation at 4°C, the beads were collected by centrifugation at 800g for 1 min and washed six times with IP buffer [25-mM Tris–HCl, 150-mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20] at 4°C during 10 min per wash. The pelleted beads were boiled for 10 min and analyzed by western blotting.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR analyses were performed as described previously (Jiang et al., 2020). Notably, both oligo(dT)20 and specific PR2-R primers were added into the reaction buffer when generating cDNA. Primers used for RT-qPCR analyses were listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Y2H assay

The constructs containing DNA activation domain and DNA binding domain were transformed into yeast strain AH109 and Y187, respectively, and then mated for 1 day at 30°C on a shaker at 45 r/min. Subsequently, the yeast cells were plated onto supplement dropout medium lacking tryptophan and leucine (−WL) or tryptophan, leucine, adenine, and histidine containing 40-μg mL−1 X-α-Gal (−WLHA + X-α-Gal). Yeast cells were cultured at 30°C for about 3 days.

RNA silencing suppression experiments

RNA silencing suppression experiment was performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 2018). Equal volumes of A. tumefaciens cultures harboring different plasmids were mixed and co-infiltrated into 5-week-old N. benthamiana leaves. The agroinfiltrated leaves were illuminated under a long-wavelength UV lamp (UVP, Upland, USA) and photographed with camera under a yellow filter at 3 dpi and 6 dpi.

Statistical analysis

The intensity of the protein bands (Figure 4A) and relative fluorescence area (Figure 3C) were measured and analyzed by ImageJ software. The RT-qPCR results were analyzed by Student’s t test. All bar charts and line charts were made with Prism 7 software. To quantify the relative cell-to-cell movement abilities, the area of red and green fluorescent were measured by ImageJ software. For each image, the red fluorescent area was subtracted from the green fluorescent area, and then divided by the red fluorescent area. The value was used as the relative movement ability of the virus. A total of 15 images were analyzed and the bar chart (Figure 4D) was made by Prism 7 software.

Sequence alignment

Sequence alignment in Supplemental Figure S2 was analyzed by using DANMAN software.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of TRXhs from N. benthamiana and A. thaliana was performed by MEGA6 software with neighbor-joining method.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this work can be found in updated N. benthamiana database (https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:f34c90af-9a2a-4279-a6d2-09cbdcb323a2) (Kourelis et al., 2019) or the Arabidopsis Information Resource (www.Arabidopsis.org) under the following accession numbers: NbTRXh1 (NbD046153.1), NbTRXh1.2 (NbD034443.1), NbTRXh1.3 (NbD029648.1), NbTRXh2.1 (NbD052469.1), NbTRXh2.2 (NbD015627.1), NbTRXh2.3 (NbE03054613.1), NbTRXh2.4 (NbD015628.1), NbTRXh9.1 (NbD027853.1), NbTRXh9.2 (NbD031089.1), AtTRXh1 (AT3G51030), AtTRXh2 (AT5G39950), AtTRXh3 (AT5G42980), AtTRXh4 (AT1G19730), AtTRXh5 (AT1G45145), AtTRXh7 (AT1G59730), AtTRXh8 (AT1G69880), AtTRXh9 (AT3G08710), and AtTRXh10 (AT3G56420).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Viral accumulation of BSMV, BSMVBM26, and BSMVΔγb at 3 dpi.

Supplemental Figure S2. Sequence alignment of TRXhs from N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S3. Western blot to confirm protein accumulation in the BiFC assay.

Supplemental Figure S4. BSMV γb protein does not affect the subcellular localization of NbTRXh1 during viral infection.

Supplemental Figure S5. GST pull-down assay to analyze the in vitro γbBM26 and NbTRXh1 interaction.

Supplemental Figure S6. Developmental phenotype and molecular analysis of NbTRXh1-RNAi transgenic lines.

Supplemental Figure S7. The effect of NbTRXh1 on the γb–αa interaction.

Supplemental Figure S8. NbTRXh1 impacts on the VSR activity of BSMV γb.

Supplemental Figure S9. In vitro analysis of reductase activity of the recombinant NbTRXh1 protein.

Supplemental Figure S10. Input proteins used for insulin reductase assay in Figure 5C.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Laura Medina-Puche (Centre for Plant Molecular Biology, Eberhard Karls University, Germany) for critical reading and thorough editing of this manuscript. We thank the members of Li lab for their helpful discussions and suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830106 and 39170147), the National Science & Technology Specific Projects of China (2016ZX08003001), and Beijing Outstanding University Discipline Program.

Conflict of interest statement. All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Zhihao Jiang, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Xuejiao Jin, State Key Laboratory of Subtropical Silviculture, College of Forestry and Biotechnology, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou 311300, PR China.

Meng Yang, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Qinglin Pi, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Qing Cao, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Zhenggang Li, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Yongliang Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Xian-Bing Wang, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Chenggui Han, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Jialin Yu, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

Dawei Li, State Key Laboratory of Agro-Biotechnology, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, PR China.

D.L., Z.J., X.J., and M.Y. conceived and designed the experiments with assistance of Q.P., Q.C., and Z.L.; Y.Z., X-B.W., C.H., and J.Y. discussed and interpreted the data; Z.J., X.J., M.Y., and D.L. wrote the paper.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) are: Dawei Li (Dawei.Li@cau.edu.cn) and Zhihao Jiang (zhihaojiang@cau.edu.cn).

References

- Alexander D, Goodman RM, Gut-Rella M, Glascock C, Weymanni K, Friedrichi L, Maddoxi D, Ahl-Goy P, Luntzi T, Ward E, et al. (1993) Increased tolerance to two oomycete pathogens in transgenic tobacco expressing pathogenesis-related protein la. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7327–7331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg JN, Jackson AO (2004) The C-terminal region of the Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein participates in homologous interactions and is required for suppression of RNA silencing. Mol Plant Pathol 5: 465–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg JN, Lawrence DM, Jackson AO (2004) The N-terminal 85 amino acids of the Barley stripe mosaic virus γb pathogenesis protein contain three zinc-binding motifs. J Virol 78: 7379–7391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Bowling SA, Gordon AS, Dong XN (1994) Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired-resistance. Plant Cell 6: 1583–1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Glazebrook J, Clarke JD, Volko S, Dong XN (1997) The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene that controls systemic acquired resistance encodes a novel protein containing ankyrin repeats. Cell 88: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jin X, Zhang X, Li Y, Wang C, Wang X, Hong J, Wang X, Li D, Zhang Y (2015) Morphogenesis of endoplasmic reticulum membrane-invaginated vesicles during Beet black scorch virus infection: role of auxiliary replication protein and new implications of three-dimensional architecture. J. Virol 89: 6184–6195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chen J, Li M, Chang M, Xu K, Shang Z, Zhao Y, Palmer I, Zhang Y, McGill J, et al. (2017) A bacterial type III effector targets the master regulator of salicylic acid signaling, NPR1, to subvert plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe 22: 777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IH, Chen HT, Huang YP, Huang HC, Shenkwen LL, Hsu YH, Tsai CH (2018) A thioredoxin NbTRXh2 from Nicotiana benthamiana negatively regulates the movement of Bamboo mosaic virus. Mol Plant Pathol 19: 405–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Xiong R, Li Y, Li F, Zhou X, Wang A (2017) Sumoylation of Turnip mosaic virus RNA polymerase promotes viral infection by counteracting the host NPR1-mediated immune response. Plant Cell 29: 508–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivasa S, Murphy AM, Naylor M, Carr JP (1997) Salicylic acid interferes with Tobacco mosaic virus replication via a novel salicylhydroxamic acid-sensitive mechanism. Plant Cell 9: 547–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding P, Ding Y (2020) Stories of salicylic acid: a plant defense hormone. Trends Plant Sci 25: 549–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald R, Jackson AO (1994) The Barley stripe mosaic virus γb gene encodes a multifunctional cysteine-rich protein that affects pathogenesis. Plant Cell 6: 1593–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RGK, Jackson AO (1996) RNA-binding activities of Barley stripe mosaic virus γb fusion proteins. J Gen Virol 77: 879–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein M (2015) Plant virus replication and movement. Virology 479: 657–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A (1979) Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J Biol Chem 254: 9627–9632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Li S, Li Z, Li H, Song W, Zhao H, Lai J, Xia L, Li D, Zhang Y (2019) A Barley stripe mosaic virus-based guide RNA delivery system for targeted mutagenesis in wheat and maize. Mol Plant Pathol 20: 1463–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Liu D, Zhang Z, Sun J, Han B, Li Z (2020) A bacterial F-box effector suppresses SAR immunity through mediating the proteasomal degradation of OsTrxh2 in rice. Plant J 104: 1054–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Zhang C, Liu JY, Guo ZH, Zhang ZY, Han CG, Wang Y (2019) Development of Beet necrotic yellow vein virus-based vectors for multiple-gene expression and guide RNA delivery in plant genome editing. Plant Biotechnol J 17: 1302–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Li Z, Yue N, Zhang K, Li D, Zhang Y (2018) Construction of infectious clones of Lychnis ringspot virus and evaluation of its relationship with Barley stripe mosaic virus by reassortment of genomic RNA segments. Virus Res 243: 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Yang M, Cao Q, Zhang Y, Li D (2022) A powerful method for studying protein–protein interactions in plants: Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay. InWang A, Li Y, eds, Plant Virology: Methods and Protocols. Springer US, New York, NY, pp 87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Yang M, Zhang Y, Jackson AO, Li D (2021) Hordeiviruses (Virgaviridae). InBamford DH, Zuckerman M, eds, Encyclopedia of Virology, Vol 3. Academic Press, Oxford, pp 420–429 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Zhang K, Li Z, Li Z, Yang M, Jin X, Cao Q, Wang X, Yue N, Li D, et al. (2020) The Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein promotes viral cell-to-cell movement by enhancing ATPase-mediated assembly of ribonucleoprotein movement complexes. PLoS Pathog 16: e1008709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Jiang Z, Zhang K, Wang P, Cao X, Yue N, Wang X, Zhang X, Li Y, Li D, et al. (2018) Three-dimensional analysis of chloroplast structures associated with virus infection. Plant Physiol 176: 282–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Qin T, Zhao Z (2019) Thioredoxins and thioredoxin reductase in chloroplasts: a review. Gene 706: 32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkema M, Fan W, Dong X (2000) Nuclear localization of NPR1 is required for activation of PR gene expression. Plant Cell 12: 2339–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneeshaw S, Gelineau S, Tada Y, Loake Gary J, Spoel Steven H (2014) Selective protein denitrosylation activity of thioredoxin-h5 modulates plant immunity. Mol Cell 56: 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourelis J, Kaschani F, Grosse-Holz FM, Homma F, Kaiser M, van der Hoorn RAL (2019) A homology-guided, genome-based proteome for improved proteomics in the alloploid Nicotiana benthamiana. BMC Genomics 20: 722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari P, Gupta A, Yadav S (2021) Thioredoxins as molecular players in plants, pests, and pathogens. InSingh IK, Singh A, eds, Plant-Pest Interactions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Chemical Ecology. Springer, Singapore, pp 107–125 [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DM, Jackson AO (2001) Requirements for cell-to-cell movement of Barley stripe mosaic virus in monocot and dicot hosts. Mol Plant Pathol 2: 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Brader Gn, Palva ET (2004) The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. Plant Cell 16: 319–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Jiang Z, Jin X, Zhang K, Wang X, Han C, Yu J, Li D (2018) Hijacking of the nucleolar protein fibrillarin by TGB1 is required for cell-to-cell movement of Barley stripe mosaic virus. Mol Plant Pathol 19: 1222–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorang J, Kidarsa T, Bradford CS, Gilbert B, Curtis M, Tzeng SC, Maier CS, Wolpert TJ (2012) Tricking the guard: exploiting plant defense for disease susceptibility. Science 338: 659–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Rivero MS, Hernandez-Zepeda C, Villanueva-Alonzo H, Minero-Garcia Y, Castell-Gonzalez SE, Moreno-Valenzuela OA (2016) Expression of genes involved in the salicylic acid pathway in type h1 thioredoxin transiently silenced pepper plants during a begomovirus compatible interaction. Mol Genet Genomics 291: 819–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata-Pérez C, Spoel SH (2019) Thioredoxin-mediated redox signalling in plant immunity. Plant Sci 279: 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier F, Zwicker S, Huckelhoven A, Meissner M, Funk J, Pfitzner AJ, Pfitzner UM (2011) NONEXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED PROTEINS1 (NPR1) and some NPR1-related proteins are sensitive to salicylic acid. Mol Plant Pathol 12: 73–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Puche L, Tan H, Dogra V, Wu M, Rosas-Diaz T, Wang L, Ding X, Zhang D, Fu X, Kim C, et al. (2020) A defense pathway linking plasma membrane and chloroplasts and co-opted by pathogens. Cell 182: 1109–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Z, Fan W, Dong X (2003) Inducers of plant systemic acquired resistance regulate NPR1 function through redox changes. Cell 113: 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaihara T, Hatanaka T, Nakano M, Oda K (2016) Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector ripAY is a glutathione-degrading enzyme that is activated by plant cytosolic thioredoxins and suppresses plant immunity. mBio 7: e00359–00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AM, Carr JP (2002) Salicylic acid has cell-specific effects on Tobacco mosaic virus replication and cell-to-cell movement. Plant Physiol 128: 552–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherton CL, Wileman T (2011) Virus factories, double membrane vesicles and viroplasm generated in animal cells. Curr Opin Virol 1: 381–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Yang J, Li X, Zhang Y (2021) Salicylic acid: biosynthesis and signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol 72: 761–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi G, Chen J, Chang M, Chen H, Hall K, Korin J, Liu F, Wang D, Fu ZQ (2018) Pandemonium breaks out: disruption of salicylic acid-mediated defense by plant pathogens. Mol Plant 11: 1427–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Ren H, Liu R, Li B, Wu T, Sun F, Liu H, Wang X, Dong H (2010) An h-type thioredoxin functions in tobacco defense responses to two species of viruses and an abiotic oxidative stress. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 23: 1470–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada Y, Spoel SH, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K, Mou ZL, Song JQ, Wang C, Zuo JR, Dong XN (2008) Plant immunity requires conformational changes of NPR1 via S-nitrosylation and thioredoxins. Science 321: 952–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Sasvari Z, Gonzalez PA, Friso G, Rowland E, Liu XM, van Wijk KJ, Nagy PD, Klessig DF (2015) Salicylic acid inhibits the replication of Tomato bushy stunt virus by directly targeting a host component in the replication complex. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 28: 379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cao X, Liu M, Zhang R, Zhang X, Gao Z, Zhao X, Xu K, Li D, Zhang Y (2018) Hsc70-2 is required for Beet black scorch virus infection through interaction with replication and capsid proteins. Sci Rep 8: 4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Goregaoker SP, Culver JN (2009) Interaction of the Tobacco mosaic virus replicase protein with a NAC domain transcription factor is associated with the suppression of systemic host defenses. J Virol 83: 9720–9730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jiang Z, Yue N, Jin X, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang Y, Wang X-B, Han C, Yu J, et al. (2021) Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein disrupts chloroplast antioxidant defenses to optimize viral replication. EMBO J 40: e107660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li X, Fan B, Zhu C, Chen Z (2021) Regulation and function of defense-related callose deposition in plants. Int J Mol Sci 22: 2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Li Z, Zhang K, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang X, Han C, Yu J, Xu K, Li D (2018) Barley stripe mosaic virus γb interacts with glycolate oxidase and inhibits peroxisomal ROS production to facilitate virus infection. Mol Plant 11: 338–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhang Y, Xie X, Yue N, Li J, Wang XB, Han C, Yu J, Liu Y, Li D (2018) Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein subverts autophagy to promote viral infection by disrupting the ATG7-ATG8 interaction. Plant Cell 30: 1582–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaliev R, Ueki S, Epel BL, Citovsky V (2011) Biology of callose (beta-1,3-glucan) turnover at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 248: 117–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Zhang Y, Yang M, Liu S, Li Z, Wang X, Han C, Yu J, Li D (2017) The Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein promotes chloroplast-targeted replication by enhancing unwinding of RNA duplexes. PLoS Pathog 13: e1006319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Dong K, Xu K, Zhang K, Jin X, Yang M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Han C, Yu J, et al. (2018) Barley stripe mosaic virus infection requires PKA-mediated phosphorylation of γb for suppression of both RNA silencing and the host cell death response. New Phytol 218: 1570–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang X, Xu K, Jiang Z, Dong K, Xie X, Zhang H, Yue N, Zhang Y, Wang XB, et al. (2021) The serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase STY46 defends against hordeivirus infection by phosphorylating γb protein. Plant Physiol 186: 715–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Li Y (2021) Current understanding of the interplays between host hormones and plant viral infections. PLoS Pathog 17: e1009242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.