Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the association between older and more recent online physician ratings and the implications for optimizing the trade-off between reliability and incentives.

When choosing a physician, patients frequently turn to online 5-star ratings, which often contain relevant quality information and can substantially affect patient decisions.1,2 Most physician-rating websites in the US and around the world display a mean of all available ratings on each physician’s profile page, irrespective of the age of these ratings. Pooling all available ratings has some advantages, including improving the reliability of reported ratings. However, it may also result in outdated information if a physician’s ratings change over time, thereby potentially weakening physician incentives to improve. To our knowledge, this cross-sectional study represents the first investigation examining the association between older and more recent online physician ratings and the implications for optimizing the trade-off between reliability and incentives.

Methods

All data in this study are from publicly published data and do not have identified patient data. Therefore, the University of Maryland institutional review board determined that it is exempted from review and the need for informed consent.

We conducted an automated Google Web Search for 1 141 176 active physicians in the US, identified on 4 major physician rating websites where a physician’s displayed profile rating is the simple mean of all available ratings. We retrieved all online ratings posted before August 1, 2021.

We compared a physician’s mean rating based on reviews in the last 3 years and the displayed profile rating based on all reviews. We considered a 0.5-star difference in rating as plausibly influential on patient choice of physicians. We used a linear mixed model (LMM) to examine the existence of meaningful differences between the recent ratings and prior ratings, which can indicate whether pooling all ratings for the profile rating is appropriate.3 Details are included in the eAppendix in the Supplement. We used Python statistical software version 3.8.3 (Anaconda) for data processing and R statistical software version 4.1.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing) for data analysis.

Results

Of the 1 141 176 physicians, 587 562 (51.49%) had at least 1 rating on the 4 commonly used rating websites, with a total of 8 693 563 ratings: Healthgrades (2 120 982 ratings), Vitals (6 056 497 ratings), RateMDs (295 674 ratings), and Yelp (220 400 ratings). Across the 4 websites, online ratings for the 587 562 physicians were a mean (SD) of 5.30 (2.95) years old by August 1, 2021. A total of 2 027 319 ratings (23.32%) were from the most recent 3 years.

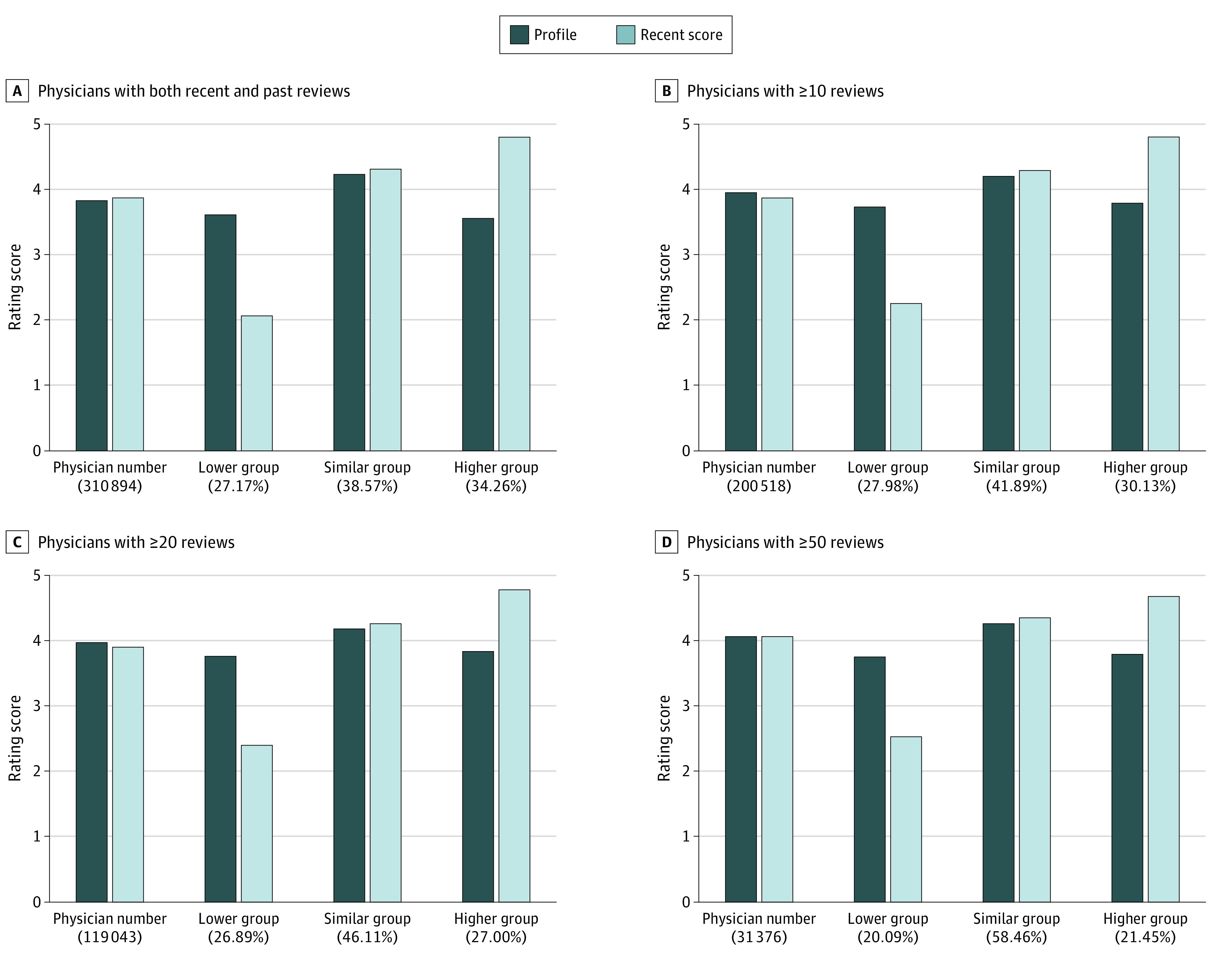

We also found substantial differences between recent 3-year ratings and the displayed profile ratings (Figure). Among the 31 376 physicians who had at least 50 reviews across recent and prior periods, 6302 (20.09%) had recent ratings that were at least 0.5 star lower than their profile ratings (mean [SD], 2.54 [0.84] vs 3.75 [0.61]), and 6731 (21.45%) had ratings that were at least 0.5 star higher (mean [SD], 4.67 [0.44] vs 3.79 [0.56]). Overall, 13 033 physicians (41.54%) had recent ratings that differed from overall profile ratings by at least 0.5 star.

Figure. Profile Ratings Using the Mean of All Ratings vs Mean Ratings From the Recent 3 Years.

The proportion of physicians whose ratings changed by less than 0.5 star over time increased from 38.6% (119 908 of 310 894 physicians) to 58.5% (18 343 of 31 376 physicians) after limiting the sample to physicians with 50 or more ratings available, suggesting that much of the temporal change in ratings was due to sampling error (Figure). The LMM estimated a moderate correlation (r = 0.61), suggesting substantial differences between the recent and older ratings after accounting for the contribution of sampling error (Table).

Table. Correlation Between Recent Ratings and Past Ratings, Controlled for Sampling Errorsa.

| Platforms and physician sample | Physicians, No. | Reviews, No. | Reviews per physician, mean No. | Estimated correlation of recent and past ratings, r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All platforms | ||||

| All physicians | 310 849 | 7 262 161 | 23.36 | 0.55 |

| Physicians with ≥10 reviews | 190 135 | 6 577 268 | 34.60 | 0.56 |

| Physicians with ≥20 reviews | 113 301 | 5 422 074 | 47.86 | 0.58 |

| Physicians with ≥50 reviews | 30 197 | 2 800 649 | 92.75 | 0.61 |

| HealthGrades | 168 130 | 1 748 293 | 10.40 | 0.54 |

| Vitals | 209 710 | 4 143 315 | 19.76 | 0.44 |

The sample is composed of physicians who have reviews in both the recent 3 years (August 1, 2018, to August 1, 2021) and prior (before August 1, 2018). To further examine the correlation between recent and past ratings, we used the linear mixed random effect mode to control for error from small sample size. A linear random mixed effect model is used to estimate the correlation between the physician random effects in recent ratings and past ratings. A small value of estimated correlation indicates the large discrepancy between the recent and past reviews. Because patients might submit reports to more than 1 platform, which could bias the correlation downward, we reexamined whether documented effects across all platforms we repeat the above analysis separately on the 2 major platforms, HealthGrades and Vitals.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, online physician ratings were, on average, 5.30 years old. In 41.54% of cases, physician ratings based on the most recent 3 years were meaningfully different from the displayed rating based on all available years. There are trade-offs between including all ratings (for more reliable measures) and more recent ratings (to recognize improvement). Although, compared with systematic surveys, online ratings are patient initiated, making it difficult to link the observed changes in ratings over time to true changes in physician quality, the current approach of including all ratings (old and new) may be suboptimal and represents a limitation of this study. One potential solution to achieving a better balance between reliability and recency is to incorporate both older and more recent information but to increase the weight given to more recent ratings, especially for physicians whose ratings change over time.3,4 Our results suggest that more scientific reporting methods are needed to make the online ratings more useful to patients and physicians.5,6

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eReference

Reference

- 1.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014;311(7):734-735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranard BL, Werner RM, Antanavicius T, et al. Yelp reviews of hospital care can supplement and inform traditional surveys of the patient experience of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):697-705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Malley AJ, Landon BE, Zaborski LA, et al. Weak correlations in health services research: weak relationships or common error? Health Serv Res. 2022;57(1):182-191. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz AL. Accuracy versus incentives: a trade-off for performance measurement. Am J Health Econ. 2021;7(3):333-360. doi: 10.1086/714374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlesinger M, Grob R, Shaller D, et al. Taking patients’ narratives about clinicians from anecdote to science. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(7):675-679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1502361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant RM, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Learning by listening-improving health care in the era of Yelp. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2483-2484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eReference