Abstract

In the era of antimicrobial resistance, the identification of new compounds with strong antimicrobial activity and the development of alternative therapies to fight drug-resistant bacteria are urgently needed. Here, we have used resveratrol, a safe and well-known plant-derived stilbene with poor antimicrobial properties, as a scaffold to design several new families of antimicrobials by adding different chemical entities at specific positions. We have characterized the mode of action of the most active compounds prepared and have examined their synergistic antibacterial activity in combination with traditional antibiotics. Some alkyl- and silyl-resveratrol derivatives show bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria in the same low micromolar range of traditional antibiotics, with an original mechanism of action that combines membrane permeability activity with ionophore-related activities. No cross-resistance or antagonistic effect was observed with traditional antibiotics. Synergism was observed for some specific general-use antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides and cationic antimicrobial peptide antibiotics. No hemolytic activity was observed at the active concentrations or above, although some low toxicity against an MRC-5 cell line was noted.

The increasing number of antimicrobial resistance occurrences together with the decrease in the number of antimicrobial agents approved for human usage constitutes one of the most challenging problems for global health. Thus, new drugs with enhanced antimicrobial activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR) as well as new therapeutic targets and/or new mechanisms of action are urgently needed.1,2 However, and despite the effort being made by the WHO and the research community, the number of new antibiotic drugs approved during the last decades fulfilling these characteristics is low. These newly approved drugs are very often variants of already known antibiotics, offering only a temporary therapeutic solution, since the mechanisms of resistance against them are already established in the pangenome of the bacterial populations.3,4

Natural phenolic compounds have been proposed as potential templates to develop new antimicrobials.5,6 These chemically diverse molecules are part of the natural plant defense systems against pathogens and could provide an extraordinary source of new antimicrobials because of their variability and the possibilities to design and prepare new chemical derivatives.7−10 Moreover, these phenolic compounds could also be used as adjuvants in synergy with traditional antibiotics enhancing their activity against pathogenic bacteria or even sensitizing the bacteria to thus far inactive antibiotics.11 In fact, drug combinations are currently exploited as one of the most promising strategies to extend the life of antibiotics in the antimicrobial resistance era.12,13

Resveratrol (RES, 1), a natural phenolic stilbene, is a well-known molecule with potential as a therapeutic agent in several clinical applications such as anticancer, neuroprotector, cardioprotector, and anti-inflammatory agent or for controlling glycemic levels in diabetes or the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.14−16 Recently, it has also been investigated as an antimicrobial agent.17,18 Its activity against bacteria is quite limited, with MIC values in the mM range.17,19,20 Synergism of resveratrol with some traditional antibiotics such as aminoglycosides has also been reported. However, the observed synergism is weak and does not result in the complete eradication of pathogenic bacteria.20,21 The role of resveratrol in combination with other antibiotics is still controversial, since antagonistic activity or bacterial growth promotion has been observed in some cases.22,23 Information about the mechanism of action of resveratrol against bacteria is quite scarce, but it has been related to cell growth inhibition due to suppression of FtsZ expression or ATP synthase activity inhibition.21,24 In the case of other natural related stilbene derivatives with a varied number of OH groups, such as pinosylvin and piceatannol,25,26 or with methylated groups, such as pinostilbene (PIN) and pterostilbene (PTER),26−28 the observed antimicrobial activity was higher than for RES alone or RES in combination with traditional drugs. Moreover, PTER is capable of enhancing the antibiotic activity of known drugs such as gentamicin or polymixin B.29,30 Several RES derivatives including methylated31 and halogenated/acetylated RES derivatives,32 hybrids of RES and pterostilbene,33,34 and RES analogues with a furane ring substituting one of the phenol rings of RES35 or modifications of the central alkene bond to a triazolyl ring36 have been reported to improve RES antimicrobial activity. These data suggest that RES is a versatile scaffold to design new families of antimicrobial drugs.

In this work, we describe the antibacterial activity of several

RES derivatives against a broad panel of Gram-negative and Gram-positive

pathogens. The modifications we have examined on RES include glucosyl-acyl,

alkyl, alkyl-sulfate, silyl, and silyl-acyl derivatives together with

two RES metabolites. We have also evaluated the antibacterial activity

of derivatives of PIN and PTER modified with glucosyl-acyl and glucuronosyl

groups. After a first screening, we synthesized and assayed several

newly designed silyl sulfate RES derivatives and silyl RES derivatives,

which had an unprecedented potent activity. Finally, we investigated

the mechanism of action of the RES derivatives with the best antibacterial

activity.

Results and Discussion

Preparation of RES Derivatives

A variety of compounds used or designed for noninfectious diseases have shown later to display in vitro antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria.37−39 On the basis of that finding, we tested a miscellaneous group of RES, PIN, and PTER derivatives (1–30), previously designed to treat noncommunicable pathologies, against a panel of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.40−43 The examined compounds incorporate either one chemical group in the hydroxyl groups of the stilbene scaffold (glucosyl, acyl, alkyl, sulfate, glucuronate, or silyl) or a combination of two or three of these groups.

Glucosyl-acyl RES derivatives 2–6 were prepared from piceid (3-O-glucosyl-resveratrol) by enzymatic acylation following the synthetic procedure previously reported.40 Resveratrol 3,4′-disulfate (7) was synthesized from RES by partial TBDMS protection, sulfation with SO3·NMe3 and Et3N under microwave irradiation, and final silyl deprotection using KF44 and purified as previously described.41 Resveratrol-3-glucuronate (8) was prepared as reported previously.45 Briefly, 3,4′-diTBDMS-resveratrol was reacted with a pivaloyl-protected glucuronate trichloroacetimidate donor followed by silyl deprotection using HF·pyridine in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and final acyl deprotection with Na2CO3 in MeOH/H2O. PIN and PTER glucuronates 29 and 30 were similarly synthesized.46 Methyl, ethyl, and butyl resveratrol derivatives 9–12 were also prepared.47,48 Random alkylation of RES was carried out using K2CO3 and the corresponding 1-iodoalkane, followed by chromatographic separation of the mono-, di-, and trialkyl resveratrol derivatives. Butyl sulfate RES derivatives 13–15 were prepared from the corresponding butyl RES derivatives by sulfation with SO3·NMe3 and Et3N under microwave irradiation.42 Glucosyl acyl PTER derivatives 26 and 27 as well as the regioisomer 28 were synthesized as previously described.42 3,4′-Dimethyl resveratrol, obtained by random methylation of RES, was glycosylated with peracetylated glucosyl trichloroacetimidate donor and BF3·Et2O as a catalyst. The corresponding product was deprotected with NaOMe in MeOH and acylated at the primary hydroxyl group using Novozym 435 and vinyl octanoate to yield compound 28. The same synthetic strategy was applied to PTER to prepare compounds 26 and 27.

Finally, silyl RES derivatives 16–22 were synthesized from RES by random silylation using the corresponding silyl chloride and imidazole in THF followed by separation of the different products using silica gel column chromatography.43 The silyl acyl RES derivative 23 was synthesized by direct enzymatic acylation of 3,5-ditriethylsilyl resveratrol using Novozym 435 and vinyl octanoate as previously reported.41 The synthesis of compound 24 followed a similar strategy to that used to prepare compounds 26–28. Glycosylation of 3,4′-ditriisopropylsilyl resveratrol with peracetylated glucosyl trichloroacetimidate donor and BF3·Et2O as catalyst, followed by selective acylation using Novozym 435 and vinyl octanoate, yielded compound 24.41 Silyl ethyl carbamate RES derivative 25 was synthesized by reacting 3,5-ditriisopropylsilyl resveratrol with ethyl isocyanate and Et3N.41

A stability study was carried out on the four more relevant compounds (15, 17, 32, and 33) together with resveratrol (1) as control. The incubation was done in the bacterial Muller-Hinton broth (M-H broth) for 24 h and in the Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) cell media for 72 h at 5 μM concentration of each compound. The results indicate that all compounds were much more stable in DMEM than in M-H broth, with percentages of compound remaining in DMEM higher than in M-H broth in all cases, even though the incubation time in DMEM is longer (Supporting Figure 1). Additionally, it can be observed that the stability of silyl RES derivatives (17 and 32), in both DMEM and M-H broth, was less than RES itself and the alkyl-sulfated-RES derivative (15). In any case, a minimum of 70% of compound remaining in DMEM and 40% in M-H broth is detectable at the final incubation time of each bioassay.

Antimicrobial Activity of the First Library of RES Derivatives

No antibacterial activity was observed against Gram-negative bacteria for the RES, PIN, or PTER derivatives in the range examined (128 to 2 μM). On the other hand, several RES and PTER derivatives were active in the low micromolar range against Gram-positive bacteria (Table 1). Among the glucosyl-acyl RES derivatives (also named piceid acylated derivatives), compound 4 containing a medium-size dodecanoyl chain showed good antibacterial activity, especially against Bacillus and Staphylococcus strains (8 or 16 μM). Interestingly, the activity decreased with smaller acyl chains (compounds 2 and 3) and also with larger acyl chains (compounds 5 and 6), although piceid stearate 6 showed some activity against Enterococcus strains, especially strong against E. faecium. This family of piceid acylated derivatives has been reported to inhibit the adhesion of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes Scott A to Caco-2 and HT-29 colonic cells by 60%, 40%, and 20%, respectively,49 although no direct antimicrobial activity was indicated. When glucosyl-acyl modifications were introduced in PIN, PTER, or 3,4′-dimethyl resveratrol (compounds 26–28), only compound 28 showed weak antibacterial activity.

Table 1. Minimal Inhibition Concentration (MIC) Observed for the Different RES Derivatives against a Panel of Aerobic and Anaerobic Gram-Positive Bacteriaa.

| compound | chemical modification | B. cereus ATCC10987 | B. cereus ATCC14579 | E. faecalis LMG08222 | E. faecalis LMG16216 | E. faecalis V583 | E. faecium LMG11423 | E. faecium LMG16003 | S.aureus LMG8224 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | glucosyl-acyl RES | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 |

| 4 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | 16 ± 0 | |

| 6 | - | - | 16 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | - | |

| 9 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | |

| 10 | alkyl RES | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | 64 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 0 | 42.6 ± 10.6 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 10.6 ± 2.6 | - | |

| 14 | alkyl sulfate RES | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 |

| 15 | 8 ± 0 | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | |

| 16 | silyl RES | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 |

| 17 | 8 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | |

| 19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 28 | Glc-acyl PTER | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 128 ± 0 |

| 30 | GlcAc Pter | 16 ± 0 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 64 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | - | - | 32 ± 0 |

| vancomycin | 6 ± 2 | nd | nd | nd | 9.8 ± 2.7 | nd | >32 | 10.7 ± 2.7 | |

| ciprofloxacin | 10.7 ± 2.7 | nd | nd | nd | 26.7 ± 5.3 | nd | 32 | 20.8 ± 4.8 | |

| gentamicin | 4 ± 0 | nd | nd | nd | >32 | nd | 12.57 ± 1.61 | 1 ± 0.35 |

| compound | chemical modification | S.aureus LMG10147 | S.aureus LMG15975 | C. beijerinckii B504 | C. botulinum CECT551 | C. difficile CECT531 | C. ihumii AP5 | C. perfringens CECT376 | C. tetani CECT4629 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | glucosyl-acyl RES | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 21.3 ± 5.3 |

| 4 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | - | |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 9 | 64 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | |

| 10 | alkyl RES | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | 128 ± 0 | - | 42.6 ± 10.6 | 32 ± 0 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | 32 ± 0 | 85.3 ± 21.3 | 8 ± 0 | |

| 14 | alkyl sulfate RES | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 |

| 15 | 8 ± 0 | 10.6 ± 2.6 | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 0 | |

| 16 | silyl RES | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 16 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 32 | 32 | 6.6 ± 1.3 |

| 17 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 10.6 ± 2.6 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 16 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | |

| 19 | - | - | 32 ± 0 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | - | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | |

| 28 | Glc-acyl PTER | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 85.3 ± 21.3 | 64 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 |

| 30 | GlcAc Pter | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 10.7 ± 2.6 | 4 ± 0 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 8 ± 0 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 4 ± 0 |

| vancomycin | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.25 ± 0.75 | nd | 0.18 ± 0.06 | nd | |

| ciprofloxacin | nd | nd | nd | nd | >32 | nd | 0.5 ± 0 | nd | |

| gentamicin | nd | nd | nd | nd | >32 | nd | >32 | nd |

The concentrations are expressed in μM. Compounds 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 18, 20–27, and 29 are not shown since they were not active under the conditions examined. - means not active under the conditions examined. nd means not determined.

The RES, PTER, and PIN metabolites 7, 8, 29, and 30 did not show antibiotic activity except PTER glucuronate 30 against Bacillus cereus, Clostridium strains, and Clostridioides difficile with MIC values below 16 μM.

Among the alkyl RES derivatives, the butyl RES compounds 9 and 11 displayed the best MIC values. The 1:1 mixture of 3,5-dibutyl and 3,4′-dibutyl resveratrol compounds 11 resulted in the range between 8 μM for E. faecium and C. tetani to 128 μM for some Staphylococcus. The 3-butyl resveratrol 9 also showed antibacterial activity but to a lesser extent than the dibutyl resveratrol mixture 11. Interestingly, when the hydroxyl groups were replaced with sulfate groups (compounds 13–15), important changes in antibacterial activity were observed. In fact, 3,4′-dibutyl-5-sulfate resveratrol 13 did not exhibit any antibiotic activity, whereas monobutyl disulfate resveratrol derivatives 14 and 15 were active against all Gram-positive bacterial strains examined. At the same time, the position where the sulfates are located is also relevant. In fact, 3-butyl-4′,5-disulfate resveratrol 15 showed MIC values of 8 μM against Bacillus and Staphylococcus strains and 16 μM against Enterococcus and Clostridium strains. However, the regioisomer 4′-butyl-3,5-disulfate resveratrol 14 exhibited higher MIC values for most bacterial strains than those obtained for compound 15.

According to Table 1, the compounds with the best antibacterial activity in this first screening were among the family of silyl RES derivatives (16–22). 3-tert-Butyldimethylsilyl resveratrol 16 and 4′-tert-butyldimethylsilyl resveratrol 17 exhibited MIC values ranging from 4 to 21 μM and from 8 to 32 μM, respectively, against Gram-positive bacterial strains examined. In contrast, another monosilyl RES derivative, the 3-triethylsilyl resveratrol 20, showed no activity, which may be due to the potential lability of these silyl groups in weak acid or basic conditions. At the same time, the disilyl and trisilyl RES derivatives (18, 19 and 21, 22) were not active or displayed very low antibacterial activity such as compound 19 against Clostridium strains. Further modifications on silyl RES derivatives with acyl, glucosyl-acyl, or carbamate (23–25) did not improve antibacterial activity for any strain examined. It must be added that the activities found for the RES derivatives were much better than those described previously for RES alone, which are usually in the mM or high μM range.17,19

RES Derivative Redesign and Antibacterial Potency

After the first screening, silyl RES derivatives 16 and 17 together with 3-butyl-4′,5-disulfate resveratrol 15 showed the best antibacterial activity. Based on these results, a second set of compounds was prepared to try to improve their bioactivity. Thus, another three monosilyl RES derivatives (31–33), as well as new silyl sulfate RES derivatives combining the two best chemical groups able to increase RES antibiotic activity, sulfates and silyl groups (34–36), were synthesized.

The synthesis of

monosilyl RES derivatives 31–33 was

carried out following the procedure described above. Silyl sulfate

RES derivatives 34–36 were synthesized

by sulfation of the corresponding TBDMS or TIPS RES derivatives with

SO3·NMe3 and Et3N under microwave

irradiation followed by silica gel column chromatography purification

in hexane/EtOAc mixtures.

The RES derivative containing the triethylsilyl group at a new position in the stilbene scaffold (31) was not active, pointing to the potential reasoning about its lability (Table 2). In contrast, tri-isopropylsilyl monosubstituted RES derivatives 32 and 33 resulted in quite active compounds, with MIC values for 32 from 4 to 8 μM against Bacillus, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus strains and from 8 to 16 μM against the Gram-positive anaerobic strains.

Table 2. Minimal Inhibition Concentration (MIC) Observed for the Different RES Derivatives against a Panel of Aerobic and Anaerobic Gram-Positive Bacteriaa.

| compound | Chemical modification | B. cereus ATCC10987 | B. cereus ATCC14579 | E. faecalis LMG08222 | E. faecalis LMG16216 | E. faecalis V583 | E. faecium LMG11423 | E. faecium LMG16003 | S.aureus LMG8224 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | silyl | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | |

| 33 | 32 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 0 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 128 ± 0 | |

| 34 | silyl sulfate | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 35 | 16 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 8 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | |

| 36 | - | - | 128 ± 0 | - | 128 ± 0 | - | - | - |

| compound | Chemical modification | S.aureus LMG10147 | S.aureus LMG15975 | C. beijerinckii B504 | C. botulinum CECT551 | C. difficile CECT531 | C. ihumii AP5 | C. perfringens CECT376 | C. tetani CECT4629 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | silyl | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 10.7 ± 2.6 | 8 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | |

| 33 | 128 ± 0 | 128 ± 0 | 21.3 ± 5.3 | 10.7 ± 2.6 | 16 ± 0 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | |

| 34 | silyl sulfate | - | - | 32 ± 0 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | - | 128 | 128 | 5.3 ± 1.3 |

| 35 | 21.3 ± 05.3 | 16 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | 64 ± 0 | |

| 36 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

The concentrations are expressed in μM. - means not active under the conditions examined.

The introduction of sulfates in positions 3 and 5 of compound 17, resulting in compound 34, almost abolished the antimicrobial activity. Only Gram-positive anaerobic strains were sensitive to 34, especially C. tetani, which suggests a positional effect of the sulfate groups that could be related to their antibacterial efficacy (Table 2). When sulfates were located at positions 3 and 4′, as in compound 15, with a tri-isopropylsilyl group instead of a butyl group at position 5 (35), we observed antibacterial activity against all examined bacterial strains, with MIC values ranging from 8 to 64 μM. However, testing the silyl sulfate RES derivatives did not improve the antibacterial activity observed for the monosilyl RES derivatives 16, 17, 32, and 33 or for the alkyl sulfate RES derivative 15. As before, none of the new set of compounds (31–36) was active against Gram-negative bacteria in a similar way to that observed for RES and PTER derivatives 2–30.

The Gram-negative Outer Membrane Acts as a Permeability Barrier

Although some of the designed RES derivatives showed strong antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria (Tables 1 and 2), none were active against Gram-negative pathogens. Infections produced by Gram-negative bacteria represent one of the greatest challenges faced by global health. Their high resistance to a high range of antimicrobials is due, among other reasons, to the presence of the external membrane that acts as a true permeability barrier for these antimicrobials.50 For this reason, we investigated if the outer membrane prevents RES derivatives from entering the cells. Thus, we permeabilized the outer membrane of E. coli LMG8223 using the outer-membrane-perturbing peptide L-1151 and tested eight selected RES derivatives active against Gram-positive bacteria (4, 15, 17, 30, 32, 33, 35, and 37). The MIC values measured for these compounds in the presence and absence of 4 μM of L-11 are listed in Table 3. Permeabilized E. coli cells were sensitive to RES derivatives in the range of concentrations found for Gram-positive bacteria. These data suggest that the target(s) for these drugs is(are) also present in Gram-negative bacteria, but the outer membrane prevents these compounds from reaching their targets.

Table 3. Antimicrobial Activity of Selected RES Derivatives against E. coli LMG8224 in the Presence or Absence of L-11 Outer-Membrane-Perturbing Peptide.

| MIC

(μM) |

||

|---|---|---|

| L-11 |

||

| compound | + 0 μM | + 4 μM |

| 4 | >128 | 6.6 ± 1.3 |

| 15 | >128 | 10.6 ± 2.6 |

| 17 | >128 | 13.3 ± 2.6 |

| 30 | >128 | 16 ± 0 |

| 32 | >128 | 8 ± 0 |

| 33 | >128 | 21.3 ± 5.3 |

| 35 | >128 | 21.6 ± 5.3 |

| 37 | >128 | 16 ± 0 |

Bactericidal/Bacteriostatic Activity of RES Derivatives

We selected four compounds among those showing the best antibacterial activity to investigate their mechanism of action. Three of them were monosilyl RES derivatives 17, 32, and 33, and the fourth was 3-butyl-4′,5-disulfate resveratrol 15. First, we tested the killing kinetics to measure the potential bactericidal or bacteriostatic effect of the selected RES derivatives. B. cereus ATCC 10987, E. faecalis V583, E. faecium LMG 16003, and S. aureus LMG 8224 were cultivated in cationic-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth medium (cMHB) in the presence of 2-fold the MIC during 24 h. At different times, a sample of the culture was withdrawn and decimal-serially diluted, and the CFU/mL was calculated. As indicated in Figure 1A, overall, the compounds showed bactericidal activity in a few hours against the four tested bacteria, except derivative 15, which was bacteriostatic when Enterococcus strains were tested (Figure 1A). To confirm the bactericidal/bacteriostatic effect, the minimal bactericidal concentration was determined. After a first MIC test at different concentrations of the compounds (128 to 2 μM) in a 96-well plate for 20 h, a new cMHB medium was added to the 96-well plate, and it was inoculated at 10% using the previous one as inoculum. Under these conditions, the absence of bacterial growth indicates a bactericidal effect. Unlike resveratrol, for which bacteriostatic activity has been previously reported,21,52,53 the antimicrobial activity of these compounds was mainly bactericidal except for compound 15, which was bacteriostatic for Enterococcus strains (Figure 1B). In this case, and although the MIC for this derivative was around 32 μM for these bacteria, the bacteria grew after the treatment at 128 μM (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Bactericidal/bacteriostatic effect analysis. (A) Killing kinetics for resveratrol (RES) and the different selected RES derivatives, compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33, at 2-fold the MIC concentration. The data represent the average of CFU/mL ± SEM. (B) Bactericidal/bacteriostatic activity of RES and the different selected RES derivatives, compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33. Neg: negative control (nontreated cells). MICA indicates the MIC obtained for the bacteria after a first MIC test ± SEM. MICB indicates the minimal bactericidal concentration ± SEM. > indicates that the bacteria grew above this concentration for the tested compounds. All the tests were performed in triplicate.

RES Derivatives Act on Bacterial Membranes Inducing Membrane Permeabilization and Hyperpolarization

According to the previous results and considering that RES in high dosage and some others RES derivatives have been previously described as bacterial membrane disruptive agents,34,54 we tested if the RES derivatives selected were able to lyse the cells. B. cereus ATCC10987 was selected as a model, and compounds at 2×, 1×, and 0.5× the MIC concentration were added at the middle of the exponential growth phase. Subsequently, the OD values were recorded for several hours. Gramicidin S was used as a positive control and resveratrol as a negative control. Figure 2 shows that all the compounds act as lytic compounds in a dose-dependent manner. Compounds 32 and 33 were the most effective derivatives lysing the cells, while compounds 15 and 17 were bacteriostatic at the MIC concentration and bactericidal at 2× the MIC (as observed in Figure 1A and 1B). Overall, the obtained data suggest that the antimicrobial target of the RES derivatives could be the bacterial membrane. Thus, we measured membrane integrity, as well as membrane polarization.

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial effect of resveratrol (RES) and the different selected RES derivatives, compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33 on actively growing cells. The % of growth was calculated with respect to the negative control, and it is expressed as the average ± SEM. The concentration of the compounds used is expressed in μM. * indicates compound additions. Gramicidin S (GRA) was used as a positive control. Neg: negative control (nontreated cells).

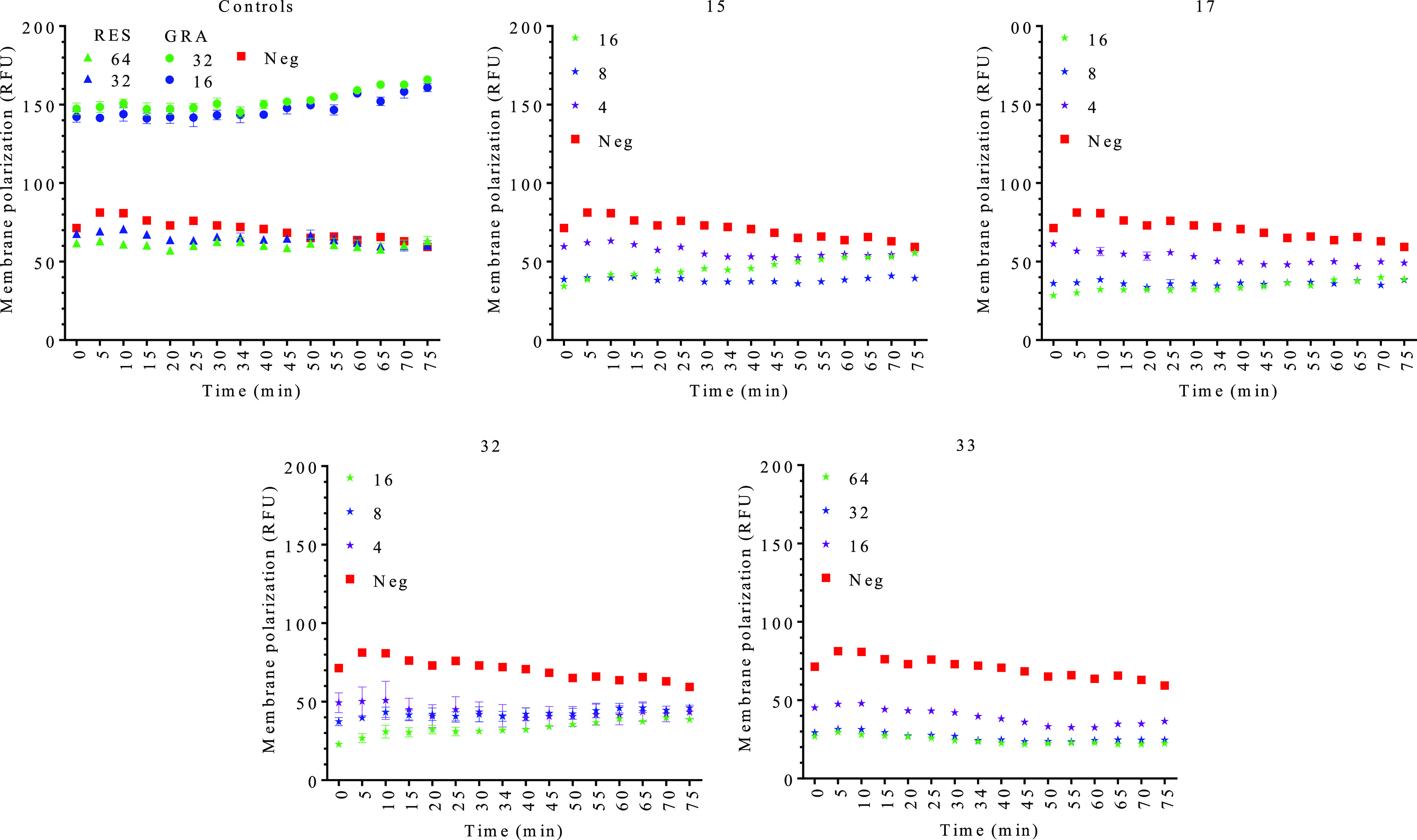

First, we evaluated the integrity of the membrane using the propidium iodide uptake test. This dye is fluorescent when binding to DNA, being nonfluorescent when is not able to cross the intact bacterial membranes and cannot reach the bacterial DNA.55 As can be seen in Figure 3, all selected RES derivatives induced membrane permeabilization in a dose-dependent manner, while RES did not induce any effect on membrane permeability.21 These data support the previous observation (Figures 1A,B and 2) and suggest that the mechanism of action of these derivatives could be related to lysis of the cells by membrane permeabilization. Since membrane permeabilization is usually related to membrane depolarization, the membrane potential was also measured using the membrane potential-sensitive dye DiSC3(5).56

Figure 3.

Propidium iodide membrane permeabilization test for resveratrol (RES) and the different selected RES derivatives, compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33. The data are expressed as the average of random fluorescent units (RFU, fluorescence normalized with the OD600) ± SEM. The concentration of the compounds is expressed in μM. Gramicidin S (GRA) was used as a positive control. Neg: negative control (nontreated cells).

As shown in Figure 4, RES did not induce any membrane potential change at the tested conditions, while the positive control (gramicidin S) induced a strong membrane depolarization. None of the RES derivatives tested induced membrane depolarization, but instead caused hyperpolarization (Figure 4). Although membrane hyperpolarization has been described for other flavonoids,57 membrane permeabilization and hyperpolarization is a phenomenon rarely described in the literature. In fact, and unlike what we observed for the RES derivatives, hyperpolarized cells showed no uptake of propidium iodide.57 This result suggests a dual activity of the RES derivatives tested, which is similar to that observed in some compounds such as the human skin fatty acid cis-6-hexadecenoic acid58 and 3-p-trans-coumaroyl-2-hydroxyquinic acid.59 Altogether, these data suggest that the RES derivatives could act as ionophores inducing the membrane hyperpolarization by one side and, at the same time, perturbing membrane integrity during the interaction by forming pores and finally lysing the cells.

Figure 4.

DiSC3(5) membrane potential detection for resveratrol (RES) and the different selected RES derivatives, compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33. The data are expressed as the average of normalized RFU ± SEM. The concentration of the compounds is expressed in μM. All the tests were performed in triplicate. Gramicidin S (GRA) was used as a positive control. Neg: negative control (nontreated cells).

RES Derivatives Impair Bacterial Respiration and Intracellular ATP Levels

Cell membrane dysfunction, as evidenced by the cell membrane hyperpolarization, impairs bacterial critical processes such as the respiratory chain and decreases ATP intracellular concentration.60,61 The effect on the respiratory chain was measured by the reduction of resazurin to resofurin, which is commonly used to determine respiratory dysfunction.62,63 As we can see in Figure 5A, incubation with RES derivatives diminished the reductive capacity of B. cereus ATC10987 cells, which is indicative of strong inhibition of the electron transport chain in a dose-related manner. For some derivatives, such as compound 32, and also for some doses of the other three compounds, the effect was comparable to or even higher than that of the proton ionophore decoupler of the electron transport chain CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone). No effect was observed for RES at the tested concentrations. Thus, the data suggest that RES derivatives could affect both the maintenance and generation of the proton motive force.

Figure 5.

(A) Activity of the respiratory chain for RES (resveratrol), CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone), and compounds 15, 17, 32, and 33, measured by reduction of resazurin (RSC) to resofurin ± SEM. The concentration of the compounds is expressed in μM. (B) Intracellular ATP levels expressed as % with respect to the negative control ± SEM. All the tests were performed in triplicate. Neg: negative control (nontreated cells).

Finally, we analyzed if the ATP production could also be impaired by the RES derivatives. We measured the intracellular ATP using BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay kit (Promega). The bacteria were incubated for 120 min with 32 μM of the compounds (100 μM for CCCP) at 37 °C, and we measured the ATP levels at 30, 60, and 120 min. As it can be seen in Figure 5B, RES did not statistically affect the ATP levels with respect to the control, whereas a time reduction of these levels was observed for the positive control CCCP. A similar outcome was observed for the RES derivatives, especially for compound 32, which reduced dramatically the ATP levels inside the cells. Overall, the results suggest that the RES derivatives can produce an uncoupling of the proton gradient established during the normal electron transfer chain process given the membrane hyperpolarization and respiration impairment. Besides, RES has been proposed to inhibit ATP synthase activity reducing the intracellular levels of ATP,21 so we may not dismiss a stronger effect of the designed derivatives on this enzyme. Low ATP intracellular levels and membrane hyperpolarization are related also to membrane permeabilization,61 inducing the lysis of the cell and the bactericidal effect observed. With respect to the electron transfer chain, no effect of RES has been proved. In fact, it could be used as a coenzyme Q precursor, a lipid essential for electron and proton transport in the respiration process.64 These data suggest a completely alternative mechanism of action for the designed RES derivatives compared to the original RES molecule.

Alkyl Sulfate RES Derivative 15 Shows a Synergistic Effect with Traditional Antibiotics

One of the most desirable characteristics of new antimicrobials is that they should not act antagonistically or generate cross-resistance with traditional antibiotics.65 The development of synergism that enhances the biocidal potential of the combination is currently one of the most promising research lines to fight multidrug-resistant bacteria. In fact, it is considered as a powerful alternative to elongate the half-life of traditional antibiotics, since the booster potential of the combinations aims for the total eradication of the pathogenic bacteria, avoiding the development of bacterial resistance.12 For this reason, we have explored the potential of 3-butyl-4′,5-disulfate resveratrol 15 and monosilyl derivative 17, in combination with 24 traditional antibiotics against E. faecium LMG16003 and S. aureus LMG82224. These organisms are listed in the priority list of the WHO for which new drugs and/or alternative therapeutic treatments are urgently needed. Among the tested antibiotics, no antagonism was observed, and only a few drugs were able to show synergism. In the case of the silyl RES derivative 17, an additive effect was mainly observed, while the alkyl sulfate derivative 15 showed strong synergistic effects. For the six best antibiotics, the reduction in the MIC values and the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) calculation are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. MIC Reduction for Combinations of Antibiotics and Two Sub-MIC Concentrations of the RES Derivativesa.

|

E.

faecium LMG16003 |

S. aureus LMG8224 |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab | RES |

15 |

17 |

Ab | RES |

15 |

17 |

|||||||||

| CT→ | 8 | 4 | 8 | FICI | 2 | 4 | FICI | 4 | 2 | 4 | FICI | 2 | 4 | FICI | ||

| Ami | >32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 ± 0 | 8 ± 0 | 2 ± 0 | 0.5 ± 0 | 0.31 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.60 |

| Bac | >32 | >32 | 16 ± 0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.27* | 32 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | 0.75* | >32 | >32 | 26.6 ± 3.7 | 4 ± 0 | 0.31* | 10.6 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 0.41* |

| Gen | 32 ± 0 | 32 ± 0 | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 0.41 | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 0.66 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 0.5 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.37 | 0.3 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.58 |

| Kan | >32 | - | - | - | - | - | 32 ± 0 | 1* | 4 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 2 ± 0 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.41 | 2 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 0.75 |

| Pol | >32 | >32 | 21.3 ± 3.7 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.27* | - | - | - | >32 | >32 | 8 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 0.25* | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 0.45* |

| Str | 32 ± 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 | - | - | - | 8 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | 0.75 |

Concentrations are expressed in μM. Ab, antibiotic alone. CT, concentration of the compounds used in the synergism. Ami, Bac, Gen, Kan, Pol, and Str correspond to the antibiotics amikacin, bacitracin, gentamicin, kanamycin, polymyxin B, and streptomycin. FICI was calculated and interpreted as described by EUCAST.66 For scores ≤0.5 synergism, <0.5 additive effect, ≤1 and >1 indifferent, ≤2 and >2 antagonistic. - means not active under the conditions examined. * means relevant FICI values.

The reductions in MIC values observed for the combinations of 15 and 17 with aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin), especially against S. aureus, were quite remarkable since these antibiotics are not prone to act synergistically with other drugs.50 This effect is surprising since it is widely accepted that membrane voltage potentiates aminoglycoside activity67 and the RES derivatives tested disrupt it. However, it has been recently described that, in the absence of voltage, aminoglycosides enter cells and exert bacteriostatic effects by inhibiting translation.68 After that, cell killing is instantaneous upon repolarization. Membrane hyperpolarization and alteration in the ATP levels are two parameters observed for the compounds that are directly involved in such an effect.68 It has been described that RES also enhances the efficacy of aminoglycosides against S. aureus, which has been related to ATP synthase inhibition.21 In the case of RES, these effects were additive and obtained at concentrations 0.5× the MIC (about 560 μM), a concentration much higher than that observed for the alkyl RES derivative examined.21

It was also quite remarkable to observe the sensitization of polymyxin B produced by compounds 15 and 17. Polymyxin B is a Gram-negative outer-membrane disruptive antibiotic that is almost inactive against Gram-positive bacteria. It has been previously observed that RES enhanced the antimicrobial effect of polymyxin B on Gram-negative bacteria but, similarly to the synergism with aminoglycosides, is observed at high dosages.69 The observed synergy could be related to an enhancement of the alternative mechanism of action described for this antibiotic.70 It could also be due to the low intracellular ATP levels induced by the RES derivatives. ATP synthase inhibition has been related to the elimination of the intrinsic polymyxin resistance in S. aureus and also sensitizes this bacterium to cationic antimicrobial peptides. This mechanism of action could also be responsible for the synergism observed for the cationic bacitracin.71,72 Bacitracin is a topically used antibiotic because of its toxicity, but its use as an oral drug to fight vancomycin-resistant enterococci has been considered.73 These combinations provide a boost of the antimicrobial activity against both E. faecium and S. aureus, which would contribute to reducing the toxicity of bacitracin and increase its applicability using new routes of administration.

Hemolytic Activity and Cytotoxicity of RES Derivatives

Finally, we also examined the cytotoxicity and the hemolytic activity of some representative RES derivatives in human fibroblast MRC5 cells (Table 4) and human purified erythrocytes (Figure 6). Butyl sulfate RES derivative 15 was among the least toxic compounds (IC50 = 24.9 μM), yielding a 1.5- to 3-fold selectivity index (SI = IC50 MRC5/MIC) for several B. cereus, S. aureus, E. faecalis, and C. tetani strains. In the case of the silyl RES derivatives, compound 17 showed toxicity in the same range as 15, with SI values between 2.0- and 3.8-fold for all Bacillus, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus strains tested. However, the rest of the silyl RES derivatives turned out to be quite toxic with IC50 values between 1.8 and 2.8 μM (compounds 16, 32, and 33) or less toxic but with no antibacterial activity (compounds 20 and 31).

Figure 6.

Hemolytic activity of resveratrol (RES) and selected resveratrol derivatives, compounds 15, 16, 17, 20, 31, 32, and 33. Percent of hemolysis was calculated with respect to the positive control (Triton X-100) ± SEM.

The tested compounds showed low hemolytic activity except at the highest concentration tested (128 μM). In this case, the derivative 32 was able to lyse 76% of the cells (Figure 6), while the derivatives 16, 17, and 33 lysed only 18.4%, 12.7%, and 13.6% of the red cells, respectively. No lysis was observed for RES and 15. Overall and except for 32, the lysis was below 5% for all the tested derivatives at the second highest concentration tested (64 μM, Figure 6). These data suggest that, in principle, the toxicity observed by the RES derivatives against eukaryotic cells may be caused by specific pathways non-membrane-damage-related as observed before for other stilbene-based resveratrol analogues.74

Table 5. Cellular Cytotoxicity for MRC5 Cells after 72 h Incubation Reported as IC50 Values (μM) Using MTT to Assess Cellular Metabolisma.

| compound |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES | 15 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 31 | 32 | 33 | |

| IC50 value | 56.6 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 4.0 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 15.5 ± 1.3 | 21.3 ± 5.9 | 32.1 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

Values expressed as mean ± standard error (n = 4–8).

In conclusion, among the potential health benefits provided by RES, its possible use as an effective antimicrobial is secondary and marginal since the high doses required prevents its implementation in the clinic. However, RES constitutes an excellent scaffold, as a starting point to design new compounds with increased antimicrobial activities in the range of traditional antibiotics. We have investigated the antimicrobial activity of a wide range of RES derivatives (glucosyl-acyl, alkyl, alkyl-sulfate, silyl, and silyl-acyl), observing good antimicrobial activity for specific compounds with some of these modifications, especially in the case of alkyl-sulfate RES and silyl RES derivatives. On the basis of these results, we designed and examined a set of new molecules combining the best chemical groups on RES, as well as newly designed silyl RES derivatives. We confirmed that not only the chemical group attached to the stilbene core but also the position of the group inside the molecule is important for the activity. Finally, we have investigated the mechanism of action for the best RES derivatives. We have observed a bactericidal mode of action and activity at the membrane level, where an unusual mode of action seems to be displayed involving membrane permeabilization and hyperpolarization, similarly to ionophore compounds. As a result of this activity, both the respiration chain and the ATP synthesis are impaired, which enhances the antimicrobial activity of these drugs. This observed mechanism of action is completely different from the one observed previously for RES and suggests a new route to kill Gram-positive bacteria. Activity against Gram-negative strains is low, since the outer membrane prevents these molecules from reaching the inner membrane in Gram-negative bacteria. Finally, we have discarded cross-resistance with traditional antibiotics. We also observed a synergistic activity with aminoglycosides and cationic antimicrobial peptide antibiotics against Gram-negative pathogens. However, preliminary toxicity data suggest a possible toxicity of these molecules against some cell lines, which justifies further efforts into optimizing the druggability of these compounds and performing in vivo studies.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

All solvents and chemicals were obtained from chemical suppliers and used as purchased without further purification. RES (1) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All reactions were monitored by TLC on F254 precoated silica gel 60 plates (Merck) and detected by heating after staining with H2SO4/EtOH (1:9, v/v) or Mostain (500 mL of 10% H2SO4, 25 g of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 1 g of Ce(SO4)2·4H2O). Products were purified by flash chromatography with silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh). Eluents are indicated for each particular case. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Advance 400 or 500 MHz NMR spectrometers at room temperature for solutions in CDCl3 or MeOH-d4. Chemical shifts are referred to the partially deuterated residual solvent signal. Two-dimensional experiments (COSY, TOCSY, ROESY, and HMQC) were carried out when necessary to assign the new compounds. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on an ESI/quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Acquity H Class).

Synthesis of Compounds

Compounds 2–6,407,418,459–12,47,4813–15,4216–25,4326–28,4129 and 30,46 and 31–3343 were synthesized and fully characterized according to the literature.

General Procedure for Silylation

In a round-bottom flask under agitation resveratrol (1 equiv) and imidazole (2.5 equiv) were suspended in dimethylformamide (DMF) (3 mL/mmol of resveratrol) and cooled to 0 °C. The corresponding silyl chloride (1.4–1.55 equiv) was added dropwise in a two-step process while stirring, half of the amount at t = 0 h and the rest at t = 3 h. The reaction was stirred for another 6 h at room temperature The reaction mixture was filtered, diluted with H2O, and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with MgSO4 and then filtered, concentrated, and added to a silica gel column eluting with gradient concentrations of hexane/EtOAc.

General Procedure for Sulfation

In a 25 mL round-bottomed flask the silyl resveratrol derivative to be sulfated (1 equiv) and SO3·Et3N complex (10 equiv) were dissolved in anhydrous MeCN (ca. 10 mL). Et3N (20 equiv) was then added. The reaction took place under agitation in a microwave (150 W, 60 °C, 1 h). After completion, the mixture was filtered and concentrated. The product was resuspended in i-PrOH, filtered, and purified in a silica gel column using hexane/EtOAc mixtures as eluents.

3,5-Disulfate-4′-tert-butyldimethylsilyl resveratrol (34):

Yield = 75%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.35 (2H, d, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.20–7.12 (3H, m), 7.01 (1H, d, J = 16.3 Hz), 6.85 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 1.02 (9H, s, 3 × CH3), 0.24 (6H, s, 2 × Si-CH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 155.57, 153.15, 139.42, 130.64, 129.24, 127.59, 125.40, 119.97, 115.17, 113.31, 53.79, 24.76, 17.69, −5.68; TOF MS ES m/z 501.0721 [M – H]− (calcd mass for C20H24O9S2Si, 501.0709).

3,4′-Disulfate-5-triisopropylsilyl resveratrol (35):

Yield = 31%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 7.38 (2H, dd, J = 8.6, 3.3 Hz), 6.97 (1H, dd, J = 16.2, 5.8 Hz), 6.88–6.74 (3H, m), 6.64–6.44 (2H, m), 6.27 (1H, t, J = 2.2 Hz), 1.33–1.25 (3H, m, 3 × Si-CH), 1.18–1.06 (18H, m, 6 × CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 158.20, 157.13, 157.04, 156.97, 139.86, 128.92, 128.27, 127.54, 127.46, 125.43, 115.17, 115.16, 109.19, 105.80, 53.84, 48.24, 44.17, 17.07, 17.03, 16.86, 12.55, 12.27, 11.64; TOF MS ES–m/z 543.1166 [M – H]− (calcd for C23H31O9S2Si2–, 543.1179).

3-Sulfate-4′,5-diisopropylsilyl resveratrol (36):

Yield = 84%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 7.68 (2H, ddd, J = 39.7, 5.7, 3.4 Hz), 7.42 (2H. t, J = 5.8 Hz), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz), 6.94–6.84 (2H, m), 6.57 (1H, d, J = 26.4 Hz), 6.29 (1H, s), 1.19–1.07 (36H, m, 12 × CH3), 0.98–0.90 (6H, m, 6 × Si-CH); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOH-d4) δ 167.93, 132.20, 131.00, 130.61, 128.47, 127.88, 127.40, 119.72, 105.94, 67.70, 38.77, 30.23, 28.74, 23.55, 22.64, 17.04, 16.99, 13.01, 12.54, 12.51, 10.02; TOF MS ES– m/z 619.2942 [M – H]− (calcd for C32H52O6SSi2, 619.2945).

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Acinetobacter baumannii LMG1041, Klebsiella aerogenes LMG2094, K. pneumoniae LMG20218, Enterobacter cloacae LMG2783, Escherichia coli LMG8223, Pseudomonas aeruginosa LMG6395, and Salmonella enterica LMG7233 as well as the Gram-positive bacteria Bacillus cereus ATCC10987 and B. cereus ATCC14579 were routinely grown in LB medium, shaking at 37 °C. Enterococcus faecalis V583,75E. faecalis LMG8222, E. faecalis LMG16216, E. faecium LMG11423, E. faecium LMG16003, Staphylococcus aureus LMG8224, S. aureus LMG10147, and S. aureus LMG15975 were grown in M17 medium plus 0.5% glucose (GM17) at 37 °C. C. botulinum CECT551, C. tetani CECT4629, C. perfringens CECT376, and Clostridioides difficile CECT531 were grown in reinforced clostridium medium (RCM) at 37 °C in anaerobiosis in Coy Lab’s vinyl anaerobic chambers, which provide a strict anaerobic atmosphere of 0–5 ppm (ppm) using a palladium catalyst and hydrogen gas mix of 5%. Agar at 1.2% was added for solid media if necessary. LMG strains were obtained from the Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms, ATCC strains from the American Type Culture Collection, and the CECT from the Spanish Type Culture Collection.

Determination of the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Test

Each resveratrol derivative was diluted in a 10 mM DMSO stock solution and assayed at concentrations ranging from 128 to 2 μM against target bacteria using the broth microdilution method according to the CLSI guideline.76 The resveratrol derivatives were serially diluted in cMHB (BD Difco) in 96-well microplates. Plates were then inoculated with the indicator bacteria at a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. In the case of the anaerobic bacteria (Clostridium and Clostridioides), the test was performed following the recommendation of CLSI for anaerobes77 but using RCM medium instead of cMHB. The cultures were cultivated inside an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C for 24 h. All the tests were performed in triplicate.

Time Killing Kinetic and Bactericidal/Bacteriostatic Effect Determination

For the killing kinetic, an actively growing culture was diluted to an OD600 in cMHB to get about 105–106 CFU/mL. After that, 2× the MIC of the compounds 15, 17, 32, 33, and RES were added and the cultures were grown at 37 °C for 24 h. At 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h a sample of each treated culture was removed and decimal-serially diluted for CFU/mL counting. To confirm bactericidal/bacteriostatic activity, the minimal bactericidal concentration was calculated. For that, a MIC test was performed at concentrations from 128 μM to 2 μM. After that, the bacteria were inoculated at 10% in a new cMHB medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The absence of growth in the same range as the MIC indicated bactericidal activity, while the presence of growth indicated the bacteriostatic effect. The tests were performed in triplicate.

Outer Membrane Permeabilization Test

To check if the outer membrane acts as a permeability barrier that protects Gram-negative bacteria against the resveratrol derivatives, E. coli LMG8223 was permeabilized with the outer-membrane-disturbing peptide L-11. Briefly, a MIC test in cMHA was performed for the different resveratrol derivatives in the presence of 4 μM of this peptide, which forms pores in the outer membrane. After that, the bactericidal/bacteriostatic effect was also tested as described before. The test was performed in triplicate.

Activity on the Bacterial Membrane

Effect of the Compounds on Actively Growing Bacteria

To test if the compounds act bacteriolytically, B. cereus ATTC10987 was used as a model. Briefly, the strain was inoculated at 2% in cMHB medium and incubated at 37 °C in an Infinite 200Pro incubator (TECAN) monitoring the OD600 every 5 min during 8 h. At the middle of the logarithmic growth phase, the compounds at three different concentrations (2×, 1×, and 0.5× MIC) were added. A clear reduction in the OD600 value was related to cell lysis. Gramicidin S at 16 and 8 μM was used as a positive control. The test was performed in triplicate.

Membrane Integrity Assay

B. cereus ATTC10987 was grown in LB with shaking at 37 °C for 18 h. After that, the cells were centrifuged and washed in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) plus 5 mM glucose (G-HEPES buffer) three times, adjusted to an OD600 of 0.5 in the same buffer plus 10 μg/mL of propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. This is a nonfluorescent dye impermeable to the bacterial membranes, but, if the membranes are disturbed, the dye can enter by binding the DNA, providing a strong fluorescent signal. In a 96-well plate, the different compounds to be tested were plated at 2× the desired concentration (2×, 1×, and 0.5× the MIC) in G-HEPES buffer. Once the cells were saturated with the dye, they were mixed 1:1 with the resveratrol derivatives. The fluorescence was monitored at 535/615 nm every 5 min during 75 min in a Varioskan Flash incubator (Thermo Scientific) at 37 °C. Gramicidin S (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive control. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Membrane Potential Assay

B. cereus ATCC10987 was cultured at 37 °C in LB medium to an OD600 of 1. The cells were washed three times with G-HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) and suspended in the same buffer at a final OD600 of 0.5. 3,3-Dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide, DiSC3(5) (Sigma-Aldrich), was added to the cells to a final concentration of 2 μM, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min to set the basal fluorescence. As before, the resveratrol derivatives to be tested were plated in a 96-well plate at 2× the desired concentration (2×, 1×, and 0.5× the MIC) in G-HEPES buffer. Once the cells were loaded with the dye, they were mixed 1:1 with the resveratrol derivatives and the fluorescence was monitored at 622/670 nm every 5 min during 75 min in a Varioskan Flash incubator (Thermo Scientific) at 37 °C. Gramicidin S (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive control for the cell permeabilization, and nontreated cells and just medium with the dye as negative controls. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Activity of the Respiratory Chain

The effect of the resveratrol derivatives on the B. cereus ATCC10987 respiratory chain was measured by the reduction of resazurin to the fluorescent resorufin. The bacteria were cultured in LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 of 1. Then, the cells were washed three times in cMHB and resuspended in this medium at a final OD600 of 0.2. Resazurin at 100 μg/mL was added to the cells that were distributed in a 96-well plate. The different resveratrol derivatives to be tested were added to the plate at the indicated concentrations, and the conversion of resazurin to resorufin was measured each 5 min at an excitation/emission of 550/590 nm during 125 min in a Varioskan Flash (Thermo Scientific). CCCP, which uncouples the respiratory chain from the proton gradient at 400, 200, and 100 μM, was used as a positive control. No treated cells and just MHB medium with resazurin were used as negative controls. All the tests were performed in triplicate.

Intracellular ATP Level Quantification

The intracellular ATP levels were determined using a BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay (Promega) kit. B. cereus ATCC10987 was cultured in LB medium at 37 °C until an OD600 of 1. Under these conditions, the cells were washed three times with G-HEPEs and suspended in cMHB at a final OD600 of 0.25. The cells were treated with the resveratrol derivatives at a 32 μM concentration at 37 °C, and after 30, 60, and 120 min 100 μL was removed, mixed with 100 μL of BacTiter-Glo reagent, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After that, the luminescence was measured in an Infinite 200Pro incubator (TECAN). CCCP (100 μM) was used as a positive control, and nontreated cells as negative control. The OD600 was determined before the ATP levels were measured, and the relative ATP levels were calculated by the OD600 with respect to the control. All the tests were performed in triplicate.

Combined Action with Antibiotics

The combined activity of the best RES derivatives and antibiotics was tested. The MIC was calculated initially for amikacin, ampicillin, bacitracin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, coumermycin A1, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, linezolid, meropenem, minocycline, nalidixic acid, novobiocin, oxacillin, pentamidine, polymyxin B, rifampicin, streptomycin, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and vancomycin against E. faecium and S. aureus. Once the MIC was known, a second MIC value was measured in the presence of sub-MIC concentrations of the desired RES derivatives. For the synergistic antibiotics, a large checkerboard test was performed78 and the intensity of the combinatorial relation was determined by calculation of the FICI. FICI was calculated and interpreted as described by EUCAST.66 For scores ≤0.5 synergism, <0.5 additive effect, ≤1 and >1 indifferent, ≤2 and >2 antagonistic.

Hemolytic Activity and Cytotoxicity

Human blood of healthy individuals was obtained from Sanquin (certified Dutch organization responsible for meeting the needs in healthcare for blood and blood products, https://www.sanquin.nl/). For the erythrocyte isolation, 10 mL of blood was centrifuged at 1000g at 4 °C for 10 min, and the yellow supernatant removed. After that, the cells were washed five times with a NaCl 0.9% solution (10 mL) in the same conditions and finally resuspended in the same volume of buffer (10 mL). In a 96-well plate, the resveratrol derivatives were added in a volume of 40 μL of NaCl 0.9%, and 160 μL of 10-fold diluted red cells was added to get a final concentration of the compounds ranging between 128 and 1 μM. Triton X-100 at 1% was used as positive lysis control. The mix was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After that, samples were centrifuged (1000g, at 4 °C for 10 min) to remove the intact erythrocytes, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 96-well plate. The release of hemoglobin absorbance was measured at OD540, and the % of hemolysis was calculated as [(HA – H0)/(H+ – H0)] × 100 where HA is the absorbance at OD540 of the samples, H0 is that for the negative control, and H+ is that for the positive control.

Cellular Cytotoxicity on MRC5 Cells

The protocol was carried out as follows: MRC-5 cells (human lung fibroblasts) were grown in monolayer (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity) in DMEM medium (1 g/L glucose), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured according to ATCC recommendations and were used for the experiments while in the exponential growth phase. Cytotoxicity was measured through the MTT assay (ThermoFisher Scientific). Briefly, 5 × 103 MRC-5 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates (100 μL/well) in the presence of increasing concentrations of compounds. After 72 h of incubation at 37 °C, 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and cells were reincubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Then, cell media was aspirated, and 100 μL of DMSO was added to each well to solubilize the formazan crystals obtained. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for an extra hour, and then the absorbance at 570 nm was measured at the Infinite F200 plate reader (TECAN Austria, GmbH). The results are expressed as the concentration of compound that reduces cell growth by 50% versus untreated control cells (EC50) using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software) to fit the data to a sigmoidal curve. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent measurements all conducted in triplicate conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Junta de Andalucía (FQM-7316) and the Dutch Research Council (NWA-Idea Generator project NWA.1228.191.006). R.C. was supported by the Ramon-Areces Foundation and the NWO-NACTAR program.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01107.

Spectra of compounds 34–36 (PDF)

Author Contributions

# R.C. and Q.L. have contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics; WHO, 2017.

- WHO . Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Theuretzbacher U.; Bush K.; Harbarth S.; Paul M.; Rex J. H.; Tacconelli E.; Thwaites G. E. Critical Analysis of Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18 (5), 286–298. 10.1038/s41579-020-0340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. S.; Paterson D. L. Antibiotics in the Clinical Pipeline in October 2019. Journal of Antibiotics 2020, 73 (6), 329–364. 10.1038/s41429-020-0291-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wang W.; Xiong H.; Song D.; Cao X. Natural Phenolic Derivatives Based on Piperine Scaffold as Potential Antifungal Agents. BMC Chemistry 2020, 14 (1), 24. 10.1186/s13065-020-00676-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtsev K. V.; Bentley M. L.; McCafferty D. G. Probing of the Cis-5-Phenyl Proline Scaffold as a Platform for the Synthesis of Mechanism-Based Inhibitors of the Staphylococcus Aureus Sortase SrtA Isoform. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17 (7), 2886–2893. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R. A. Natural Products and Plant Disease Resistance. Nature 2001, 411 (6839), 843–847. 10.1038/35081178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawara H. Possible Drugs for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections in the Future: Anti-Virulence Drugs. Journal of Antibiotics 2021, 74 (1), 24–41. 10.1038/s41429-020-0344-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli G.; Giacomini D. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities for Natural and Synthetic Dual-Active Compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 158, 91–105. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.; Georgiev M. I.; Cao H.; Nahar L.; El-Seedi H. R.; Sarker S. D.; Xiao J.; Lu B. Therapeutic Potential of Phenylethanoid Glycosides: A Systematic Review. Medicinal Research Reviews 2020, 40 (6), 2605–2649. 10.1002/med.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchino S. A.; Butassi E.; Liberto M. D.; Raimondi M.; Postigo A.; Sortino M. Plant Phenolics and Terpenoids as Adjuvants of Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs. Phytomedicine 2017, 37, 27–48. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M.; Wright G. D. Drug Combinations: A Strategy to Extend the Life of Antibiotics in the 21st Century. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17 (3), 141–155. 10.1038/s41579-018-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejim L.; Farha M. A.; Falconer S. B.; Wildenhain J.; Coombes B. K.; Tyers M.; Brown E. D.; Wright G. D. Combinations of Antibiotics and Nonantibiotic Drugs Enhance Antimicrobial Efficacy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7 (6), 348–350. 10.1038/nchembio.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso G.; Cassader M.; Gambino R. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: Emerging Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (4), 249–274. 10.1038/nrd.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur J. A.; Sinclair D. A. Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: The in Vivo Evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5 (6), 493–506. 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A. Y.; Motechin R. A.; Wiesenfeld M. Y.; Holz M. K. The Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: A Review of Clinical Trials. NPJ. Precis Oncol 2017, 1, 35. 10.1038/s41698-017-0038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard M.; Ingmer H. Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Resveratrol. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53 (6), 716–723. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D. S. L.; Tan L. T.-H.; Chan K.-G.; Yap W. H.; Pusparajah P.; Chuah L.-H.; Ming L. C.; Khan T. M.; Lee L.-H.; Goh B.-H. Resveratrol-Potential Antibacterial Agent against Foodborne Pathogens. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 102. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulo L.; Ferreira S.; Gallardo E.; Queiroz J. A.; Domingues F. Antimicrobial Activity and Effects of Resveratrol on Human Pathogenic Bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26 (8), 1533–1538. 10.1007/s11274-010-0325-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skroza D.; Šimat V.; Možina S. S.; Katalinić V.; Boban N.; Mekinić I. G. Interactions of Resveratrol with Other Phenolics and Activity against Food-Borne Pathogens. Food Sci. Nutrition 2019, 7 (7), 2312–2318. 10.1002/fsn3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nøhr-Meldgaard K.; Ovsepian A.; Ingmer H.; Vestergaard M. Resveratrol Enhances the Efficacy of Aminoglycosides against Staphylococcus Aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52 (3), 390–396. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosato M. G.; Schilardi P. L.; de Mele M. F. L.; Thomas A. H.; Miñán A.; Lorente C. Resveratrol Enhancement Staphylococcus Aureus Survival under Levofloxacin and Photodynamic Treatments. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51 (2), 255–259. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt Z.; Minoia M.; Spain J. C. Resveratrol as a Growth Substrate for Bacteria from the Rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84 (10), e00104–18. 10.1128/AEM.00104-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D.; Lim Y.-H. Resveratrol Antibacterial Activity against Escherichia Coli Is Mediated by Z-Ring Formation Inhibition via Suppression of FtsZ Expression. Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 10029. 10.1038/srep10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K.; Lee H. J.; Min H. Y.; Park E. J.; Lee K. M.; Ahn Y. H.; Cho Y. J.; Pyee J. H. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Pinosylvin, a Constituent of Pine. Fitoterapia 2005, 76 (2), 258–260. 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakova T.; Rondevaldova J.; Bernardos A.; Landa P.; Kokoska L. The Relationship between Structure and in Vitro Antistaphylococcal Effect of Plant-Derived Stilbenes. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 2018, 65 (4), 467–476. 10.1556/030.65.2018.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorkova E.; Zakova T.; Landa P.; Novakova J.; Vadlejch J.; Kokoska L. Growth Inhibitory Effect of Grape Phenolics against Wine Spoilage Yeasts and Acetic Acid Bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 161 (3), 209–213. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-C.; Tseng C.-H.; Wang P.-W.; Lu P.-L.; Weng Y.-H.; Yen F.-L.; Fang J.-Y. Pterostilbene, a Methoxylated Resveratrol Derivative, Efficiently Eradicates Planktonic, Biofilm, and Intracellular MRSA by Topical Application. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1103. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. X.; Basri D. F.; Ghazali A. R. Bactericidal Effect of Pterostilbene Alone and in Combination with Gentamicin against Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Molecules 2017, 22 (3), 463. 10.3390/molecules22030463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Liu S.; Wang T.; Li H.; Tang S.; Wang J.; Wang Y.; Deng X. Pterostilbene, a Potential MCR-1 Inhibitor That Enhances the Efficacy of Polymyxin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62 (4), e02146–17. 10.1128/AAC.02146-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalal M.; Klinguer A.; Echairi A.; Meunier P.; Vervandier-Fasseur D.; Adrian M. Antimicrobial Activity of Resveratrol Analogues. Molecules 2014, 19 (6), 7679–7688. 10.3390/molecules19067679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D.; Mendonsa R.; Koli M.; Subramanian M.; Nayak S. K. Antibacterial Activity of Resveratrol Structural Analogues: A Mechanistic Evaluation of the Structure-Activity Relationship. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 367, 23–32. 10.1016/j.taap.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righi D.; Huber R.; Koval A.; Marcourt L.; Schnee S.; Le Floch A.; Ducret V.; Perozzo R.; de Ruvo C. C.; Lecoultre N.; Michellod E.; Ebrahimi S. N.; Rivara-Minten E.; Katanaev V. L.; Perron K.; Wolfender J.-L.; Gindro K.; Queiroz E. F. Generation of Stilbene Antimicrobials against Multiresistant Strains of Staphylococcus Aureus through Biotransformation by the Enzymatic Secretome of Botrytis Cinerea. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83 (8), 2347–2356. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattio L. M.; Dallavalle S.; Musso L.; Filardi R.; Franzetti L.; Pellegrino L.; D’Incecco P.; Mora D.; Pinto A.; Arioli S. Antimicrobial Activity of Resveratrol-Derived Monomers and Dimers against Foodborne Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9 (1), 19525. 10.1038/s41598-019-55975-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso F.; Mendoza L.; Castro P.; Cotoras M.; Aguirre M.; Matsuhiro B.; Isaacs M.; Rossi M.; Viglianti A.; Antonioletti R. Antifungal Activity of Resveratrol against Botrytis Cinerea Is Improved Using 2-Furyl Derivatives. PLoS One 2011, 6 (10), e25421. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaradja E.; Bentabed-Ababsa G.; Scalabrini M.; Chevallier F.; Philippot S.; Fontanay S.; Duval R. E.; Halauko Y. S.; Ivashkevich O. A.; Matulis V. E.; Roisnel T.; Mongin F. Deprotometalation–Iodolysis and Computed CH Acidity of 1,2,3- and 1,2,4-Triazoles. Application to the Synthesis of Resveratrol Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23 (19), 6355–6363. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyski S. Non-Antibiotics--Drugs with Additional Antimicrobial Activity. Acta Polym. Pharm. 2003, 60 (5), 401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadinou M.; Onisor M. O.; Rigas A.; Musetescu D.-V.; Gkentzi D.; Assimakopoulos S. F.; Panos G.; Marangos M. Antimicrobial Properties on Non-Antibiotic Drugs in the Era of Increased Bacterial Resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9 (3), 107. 10.3390/antibiotics9030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.; Naseri M.; He Y.; Xu C.; Walsh L. J.; Ziora Z. M. Non-Antibiotic Antimicrobial Agents to Combat Biofilm-Forming Bacteria. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2020, 21, 445–451. 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrosa M.; Tomé-Carneiro J.; Yáñez-Gascón M. J.; Alcántara D.; Selma M. V.; Beltrán D.; García-Conesa M. T.; Urbán C.; Lucas R.; Tomás-Barberán F.; Morales J. C.; Espín J. C. Preventive Oral Treatment with Resveratrol Pro-Prodrugs Drastically Reduce Colon Inflammation in Rodents. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (20), 7365–7376. 10.1021/jm1007006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falomir E.; Lucas R.; Peñalver P.; Martí-Centelles R.; Dupont A.; Zafra-Gómez A.; Carda M.; Morales J. C. Cytotoxic, Antiangiogenic and Antitelomerase Activity of Glucosyl- and Acyl- Resveratrol Prodrugs and Resveratrol Sulfate Metabolites. Chembiochem 2016, 17 (14), 1343–1348. 10.1002/cbic.201600084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñalver P.; Belmonte-Reche E.; Adán N.; Caro M.; Mateos-Martín M. L.; Delgado M.; González-Rey E.; Morales J. C. Alkylated Resveratrol Prodrugs and Metabolites as Potential Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 123–138. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte-Reche E.; Peñalver P.; Caro-Moreno M.; Mateos-Martín M. L.; Adán N.; Delgado M.; González-Rey E.; Morales J. C. Silyl Resveratrol Derivatives as Potential Therapeutic Agents for Neurodegenerative and Neurological Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 223, 113655. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino J.; Park E.-J.; Kondratyuk T. P.; Marler L.; Pezzuto J. M.; van Breemen R. B.; Mo S.; Li Y.; Cushman M. Selective Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Sulfate-Conjugated Resveratrol Metabolites. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (13), 5033–5043. 10.1021/jm100274c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas R.; Alcantara D.; Morales J. C. A Concise Synthesis of Glucuronide Metabolites of Urolithin-B, Resveratrol, and Hydroxytyrosol. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344 (11), 1340–1346. 10.1016/j.carres.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñalver P.; Zodio S.; Lucas R.; de-Paz M. V.; Morales J. C. Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Pterostilbene Metabolites in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y and RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68 (6), 1609–1620. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puksasook T.; Kimura S.; Tadtong S.; Jiaranaikulwanitch J.; Pratuangdejkul J.; Kitphati W.; Suwanborirux K.; Saito N.; Nukoolkarn V. Semisynthesis and Biological Evaluation of Prenylated Resveratrol Derivatives as Multi-Targeted Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 71 (4), 665–682. 10.1007/s11418-017-1097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini F.; Verotta L.; Lecchi M.; Restano R.; Curia G.; Redaelli E.; Wanke E. Resveratrol Derivatives and Their Role as Potassium Channels Modulators. J. Nat. Prod 2004, 67 (3), 421–426. 10.1021/np0303153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selma M. V.; Larrosa M.; Beltrán D.; Lucas R.; Morales J. C.; Tomás-Barberán F.; Espín J. C. Resveratrol and Some Glucosyl, Glucosylacyl, and Glucuronide Derivatives Reduce Escherichia Coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Listeria Monocytogenes Scott A Adhesion to Colonic Epithelial Cell Lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60 (30), 7367–7374. 10.1021/jf203967u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNair C. R.; Brown E. D. Outer Membrane Disruption Overcomes Intrinsic, Acquired, and Spontaneous Antibiotic Resistance. mBio 2020, 11 (5), e01615–20. 10.1128/mBio.01615-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Cebrián R.; Montalbán-López M.; Ren H.; Wu W.; Kuipers O. P. Outer-Membrane-Acting Peptides and Lipid II-Targeting Antibiotics Cooperatively Kill Gram-Negative Pathogens. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4 (1), 31. 10.1038/s42003-020-01511-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S.; Domingues F. The Antimicrobial Action of Resveratrol against Listeria Monocytogenes in Food-Based Models and Its Antibiofilm Properties. J. Sci. Food Agric 2016, 96 (13), 4531–4535. 10.1002/jsfa.7669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euba B.; López-López N.; Rodríguez-Arce I.; Fernández-Calvet A.; Barberán M.; Caturla N.; Martí S.; Díez-Martínez R.; Garmendia J. Resveratrol Therapeutics Combines Both Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Properties against Respiratory Infection by Nontypeable Haemophilus Influenzae. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 12860. 10.1038/s41598-017-13034-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.; Lee D. G. Resveratrol Induces Membrane and DNA Disruption via Pro-Oxidant Activity against Salmonella Typhimurium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 489 (2), 228–234. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepp O.; Galluzzi L.; Lipinski M.; Yuan J.; Kroemer G. Cell Death Assays for Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10 (3), 221–237. 10.1038/nrd3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Winkel J. D.; Gray D. A.; Seistrup K. H.; Hamoen L. W.; Strahl H. Analysis of Antimicrobial-Triggered Membrane Depolarization Using Voltage Sensitive Dyes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016, 4, 29. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D.; Hurdle J. G.; Lee R.; Lee R.; Cushman M.; Pezzuto J. M. Evaluation of Flavonoid and Resveratrol Chemical Libraries Reveals Abyssinone II as a Promising Antibacterial Lead. ChemMedChem. 2012, 7 (9), 1541–1545. 10.1002/cmdc.201200253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartron M. L.; England S. R.; Chiriac A. I.; Josten M.; Turner R.; Rauter Y.; Hurd A.; Sahl H.-G.; Jones S.; Foster S. J. Bactericidal Activity of the Human Skin Fatty Acid Cis-6-Hexadecanoic Acid on Staphylococcus Aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58 (7), 3599–3609. 10.1128/AAC.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Bai J.; Zhong K.; Huang Y.; Qi H.; Jiang Y.; Gao H.. Antibacterial Activity and Membrane-Disruptive Mechanism of 3-p-Trans-Coumaroyl-2-Hydroxyquinic Acid, a Novel Phenolic Compound from Pine Needles of Cedrus Deodara, against Staphylococcus Aureus. Molecules 2016, 21 ( (8), ), 1084. 10.3390/molecules21081084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Wang S.; Li J.; Bai F.; Yang Y.; Xu Y.; Liang S.; Xia X.; Wang X.; Shi C. The Antimicrobial Activity of Coenzyme Q0 against Planktonic and Biofilm Forms of Cronobacter Sakazakii. Food Microbiology 2020, 86, 103337. 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhauteghem D.; Janssens G. P. J.; Lauwaerts A.; Sys S.; Boyen F.; Cox E.; Meyer E. Exposure to the Proton Scavenger Glycine under Alkaline Conditions Induces Escherichia Coli Viability Loss. PLoS One 2013, 8 (3), e60328. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeloh D.; Tipmanee V.; Jim K. K.; Dekker M. P.; Bitter W.; Voravuthikunchai S. P.; Wenzel M.; Hamoen L. W. The Novel Antibiotic Rhodomyrtone Traps Membrane Proteins in Vesicles with Increased Fluidity. PLOS Pathogens 2018, 14 (2), e1006876. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Amero K. K.; Bosley T. M. Detection of Mitochondrial Respiratory Dysfunction in Circulating Lymphocytes Using Resazurin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005, 129 (10), 1295–1298. 10.5858/2005-129-1295-DOMRDI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L. X.; Williams K. J.; He C. H.; Weng E.; Khong S.; Rose T. E.; Kwon O.; Bensinger S. J.; Marbois B. N.; Clarke C. F. Resveratrol and Para-Coumarate Serve as Ring Precursors for Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis[S]. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56 (4), 909–919. 10.1194/jlr.M057919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuretzbacher U.; Outterson K.; Engel A.; Karlén A. The Global Preclinical Antibacterial Pipeline. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18 (5), 275–285. 10.1038/s41579-019-0288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Dieases (ESCMID). EUCAST Definitive Document E.Def 1.2, May 2000: Terminology Relating to Methods for the Determination of Susceptibility of Bacteria to Antimicrobial Agents. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000, 6 ( (9), ), 503–508 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause K. M.; Serio A. W.; Kane T. R.; Connolly L. E. Aminoglycosides: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016, 6 (6), a027029. 10.1101/cshperspect.a027029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni G. N.; Kralj J. M. Membrane Voltage Dysregulation Driven by Metabolic Dysfunction Underlies Bactericidal Activity of Aminoglycosides. eLife 2020, 9, e58706. 10.7554/eLife.58706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Yu J.; Shen X.; Cao X.; Zhan Q.; Guo Y.; Yu F. Resveratrol Enhances the Antimicrobial Effect of Polymyxin B on Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Escherichia Coli Isolates with Polymyxin B Resistance. BMC Microbiology 2020, 20 (1), 306. 10.1186/s12866-020-01995-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]