Dear Editor,

Since emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) in late December 2019, a few new threats developed chief of which are novel variants of SARS-CoV-2 [1,2] that have a potential immune escape. In addition, the Russo-Ukraine war, acute severe hepatitis in children of unknown origin and, recently, monkeypox virus (MPXV) in non-endemic areas like Europe and Latin America which further affects the social, mental, and economic status globally. Unquestionably, the Russo-Ukraine war can help the spread of viral pathogens due to war-related immigration, adding to the tendency in non-war regions of many people gathering after pandemic-related curfew and home isolation. Social isolation, face mask-wearing, and hygiene are the only feasible preventives measures against the COVID-19 pandemic [3] in light of the relative lack of definitive therapy and effective vaccines. Historically, diseases find their way under the shadow of wars, conflicts, and natural disasters [4]. Therefore, in addition to the ongoing Russo-Ukraine war and refugee displacement [4,5], male gender, deforestation, climate change, demographic shifts, and population movement have been suggested as potential risk factors for monkeypox resurgence [6,7].

Over 1300 monkeypox confirmed cases (https://www.monkeypoxmeter.com/) have emerged in at least 40 non-African countries in Europe, Latin America, and Asia as of June 10, 2022 (Fig. 1 ). The culprit in the current monkeypox outbreak is the West African clade (case fatality rate or CFR; less than 4%), compared to another clade found in Central Africa (CFR; up to 10%), with no evidence on any genetic changes in the virus. The World Health Organization has warned that the spread of monkeypox outside of Africa may only be the tip of the iceberg. The first case of monkeypox was recorded in the United Kingdom in early May, and since then, monkey pox has been reported in several countries. People who had lately traveled from an African country were usually implicated in the recent emergence of monkeypox in non-African countries. Health agencies have said that the majority of infections were found in gay men and bisexual men or men who have sex with men. It is the largest ever outbreak outside of Africa and is concentrated among men who have sex with men, a phenomenon never seen before.

Fig. 1.

The map shows the cases on which they were confirmed by a test against the monkeypox virus as of June 9, 2022. The most affected areas are Europe, the Americas, and Australia.

Human illnesses affect men and women differently. In general, both the proportion of individuals infected and the severity of the infection are higher in males than females for viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic diseases [8,9]. Male-to-male transmission has not been explained enough in terms of infectious diseases. The most commonly routes of transmission are the vertical (mother to child) and horizontal transmission (male-to-female or female-to-male transmission) of pathogens. With the advent of some countries admitting homosexuality as personal freedom, we need to focus on infectious agents that can highly-spread through this kind of transmission and the potential factors for occurrence. However, some countries are forbidden from homosexuality (homophobia) due to their beliefs and religions, such as Islamic and African countries [10], and that could explain the most common route of transmission of monkeypox in the real world. It definitively helps us to adopt the right preventive strategies in tandem with proposed therapeutic and vaccination strategies.

Heskin et al. [11] reported the first case of MPXV infection with documented transmission through sex. Sexual intercourse transmission may become more widespread than previously thought; therefore, sexually active people of all demographics are likely to be affected. Strikingly, most confirmed cases in the monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria in 2017 were among adults, whose ages ranged from 21 to 40 years, with male to female ratio of 2.5:1 [12]. In studying murine gammaherpesvirus as a standard lab model for human herpesviruses, Erazo and colleagues found that male-to-male transmission was the highest [13]. Male-to-male transmission has been reported in viral pathogens, such as the ZIKV virus, HIV, and Hepatitis B. Identification and investigation of cases of sexual transmission of monkeypox virus in non-endemic areas present valuable opportunities to inform recommendations to prevent transmission of monkeypox virus via sexual contact.

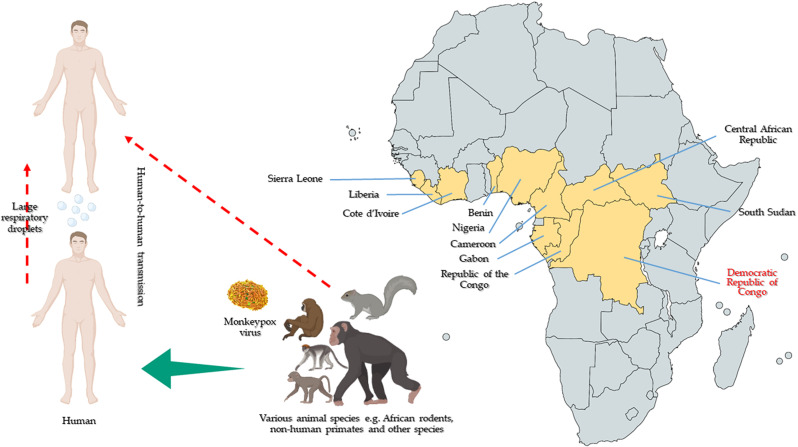

Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease for which the animal reservoir is unknown [14]. Since Monkeypox emergence and it is endemic in 11 West and Central African countries (Fig. 2 ). Monkeypox is a typical example of the potentially volatile combination of zoonotic spillover and anthropogenic factors that makes up the majority of the world's epidemic potential [15]. Monkeypox is usually self-limiting, but because the virus has not been detected in non-endemic populations, there is unlikely to be much immunity. Scientists are afraid that this virus could establish a long-term foothold in Europe or North America, allowing it to infect some animal hosts. Once the virus is circulating among these animals, it can continue jumping back into humans who might come into contact with infected animals.

Fig. 2.

The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo during a period of intensified effort to eliminate smallpox. Since 1970, human cases of monkeypox have been reported in 11 African countries: Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone and South Sudan. There are two strains of monkeypox are the Congo Basin clade with CFR at about 10%, whereas the West African clade with CFR less than 4%, that was observed to be much higher in HIV patients.

Ultimately, a deeper understanding of viral transmission will allow the development of a sex-based approach to disease screening and treatment. Also, containing the virus in the human population could be a fake success if the virus is established in the wild population, such as rodents.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, internally peer-reviewed.

Ethical approval

This article does not include any human/animal subjects to acquire such approval.

Sources of funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

AbdulRahman A. Saied: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - review & editing. Asmaa A. Metwally: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - review & editing. Priyanka: Writing - review & editing. Om Prakash Choudhary: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - review & editing. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Research registration Unique Identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry:

Unique Identifying number or registration ID:

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):

Guarantor

AbdulRahman A Saied, Researcher, National Food Safety Authority (NFSA), Aswan, Egypt and Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Aswan, Egypt. Email: saied_abdelrahman@yahoo.com.

Availability of data and materials

The data in this correspondence article is not sensitive in nature and is accessible in the public domain. The data is therefore available and not of a confidential nature.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106745.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Saied A.A., Metwally A.A., Alobo M., Shah J., Sharun K., Dhama K. Bovine-derived antibodies and camelid-derived nanobodies as biotherapeutic weapons against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants: a review Article. Int. J. Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maulud S.Q., Hasan D.A., Ali R.K., Rashid R.F., Saied A.A., Dhawan M., et al. Deltacron: apprehending a new phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Surg. 2022;102 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priyanka O.P.C., Singh I., Patra G. Aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2: the unresolved paradox. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhary O.P., Saied A.A., Priyanka Ali RK., Maulud S.Q. Russo-Ukrainian war: an unexpected event during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022;48 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhawan M., Choudhary O.P., Saied A.A. Russo-Ukrainian war amid the COVID-19 pandemic: global impact and containment strategy–Correspondence. Int. J. Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhawan M., Emran T Bin, Islam F. The resurgence of monkeypox cases: reasons, threat assessment, and possible preventive measures. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen E., Kantele A., Koopmans M., Asogun D., Yinka-Ogunleye A., Ihekweazu C., et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2019;33:1027–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein S.L. The effects of hormones on sex differences in infection: from genes to behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000;24:627–638. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts C.W., Walker W., Alexander J. Sex-associated hormones and immunity to protozoan parasites. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:476–488. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.476-488.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Klinken A.S., Chitando E. Routledge Abingdon; 2016. Public Religion and the Politics of Homosexuality in Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heskin J., Belfield A., Milne C., Brown N., Walters Y., Scott C., et al. Transmission of monkeypox virus through sexual contact–A novel route of infection. J. Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowotade A., Fasuyi T.O., Bakare R.A. Re-emergence of monkeypox in Nigeria: a cause for concern and public enlightenment. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2018;19:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erazo D., Pedersen A.B., Gallagher K., Fenton A. Who acquires infection from whom? Estimating herpesvirus transmission rates between wild rodent host groups. Epidemics. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2021.100451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCollum A.M., Damon I.K. Human monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakoune E., Olliaro P. Waking up to monkeypox. BMJ. 2022:377. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data in this correspondence article is not sensitive in nature and is accessible in the public domain. The data is therefore available and not of a confidential nature.