Abstract

The Affordable Care Act has extended coverage for uninsured and underinsured Americans, but it could exacerbate existing problems of access to primary care. Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are one way to improve access and increase practice productivity, but few studies have examined the patient’s perspective on participation in SMAs. To understand patient experiences, 5 focus group sessions were conducted with a total of 30 people in the San Francisco Bay Area. The sessions revealed that most participants felt that they received numerous tangible and intangible benefits from SMAs, particularly enhanced engagement with other patients and physicians, learning, and motivation for health behavior change. Most importantly, participants noted changes in the power dynamic during SMA visits as they increasingly saw themselves empowered to impart information to the physician. Although SMAs improve access, engagement with physicians and other patients, and knowledge of patients’ health, they also help to ease the workload for physicians.

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides coverage for millions of uninsured and underinsured Americans.1 However, the ACA does not solve the existing problem of primary care access, which will only intensify with an estimated 32 million additional individuals becoming insured by 2019.1,2 Further strain on primary care is also expected as baby boomers become Medicare eligible at the rate of 10,000 per day through 2029,1 totaling between 71 million and 80 million by 2030.1,2 Older patients also require more health care resources and have more chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.2

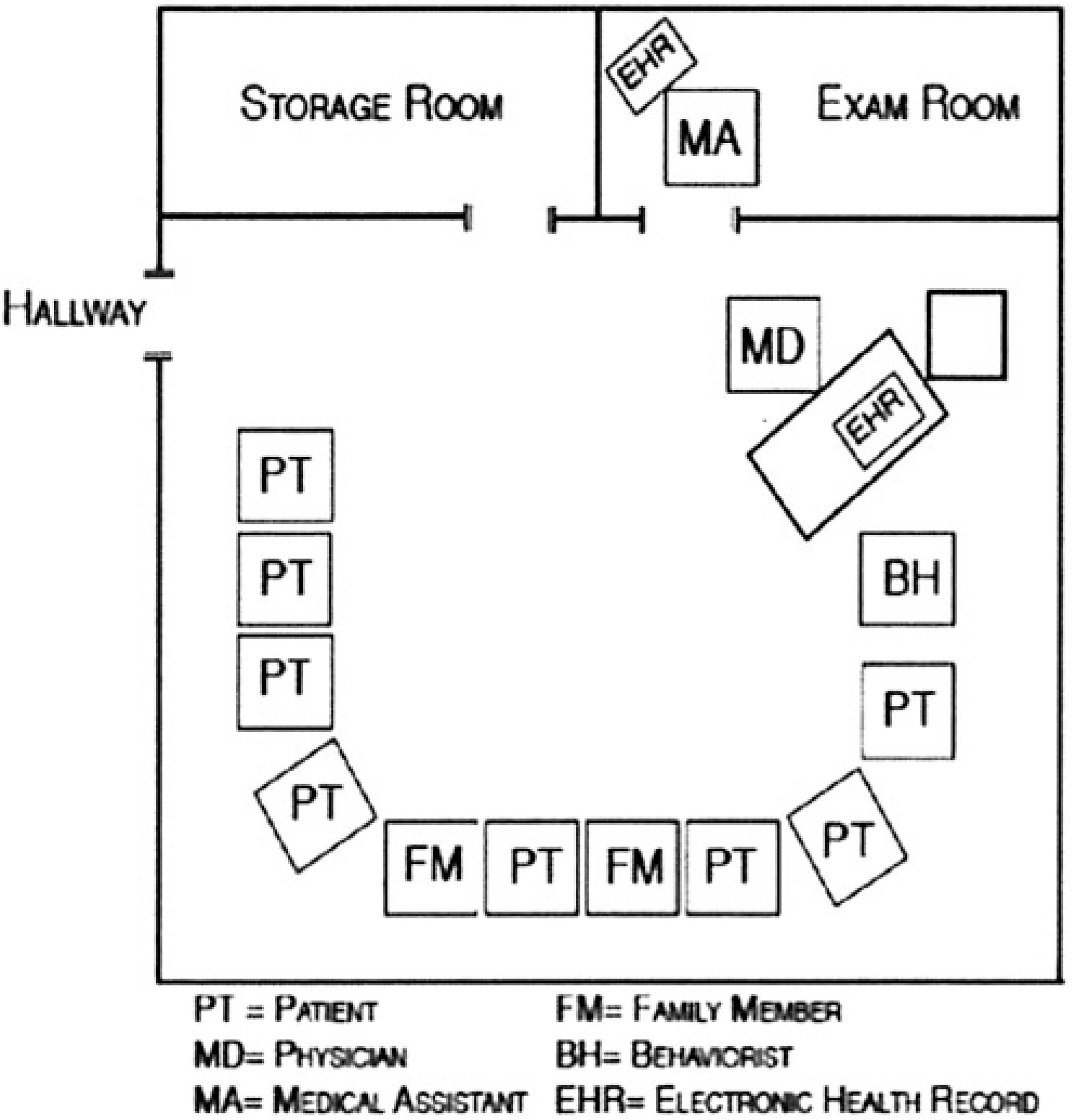

One solution that has been touted as a “primary care system change” to overcome the challenges of rushed visits, underused self-management education,3 and physician shortages4 is shared medical appointments (SMAs). SMAs or group visits are medical visits wherein multiple patients are seen simultaneously in a group setting by a physician.5 A sample spatial arrangement of an SMA is shown in Figure 1. Given that patient participants are sharing health concerns, all participants sign a confidentiality agreement prior to the SMA indicating that they consent to have their medical issues discussed before others and that they agree not to identify other attendees or share information about their concerns once the session is over.5 SMAs have been documented to improve patient access and increase productivity in the clinic.4,6 But the benefits of SMAs extend beyond simply improving clinic efficiency. SMAs also have numerous important benefits for patients including overall satisfaction,4,7,8 weight loss,9 reduced hospital admissions,3,10 improved hemoglobin A1c,3,11–13 and improved blood pressure control.3,11–14 However, to the research team’s knowledge, few studies have examined SMAs from the patient’s perspective.15

FIG. 1.

Example of a shared medical appointment spatial arrangement.

Methods

Setting

The present study took place in a large, nonprofit group practice in northern California that serves 4 counties and more than 850,000 patients. The results presented herein were gathered from November 2011 to January 2012 as part of a larger mixed-methods study of primary care transformation at this group practice.16,17 The focus group portion of the study was designed based on previous research on SMAs,9,13,18 as well as key informant interviews with individuals involved in the SMA process.

Data collection

The research team employed the focus group format because of its ability to stimulate and generate ideas from the responses of others, the opportunity to ask follow-up questions and probe answers, and the generation of a greater number of viewpoints in a shorter time period than with individual interviews.19 Focus groups have limitations19 and can be subject to social bias such as conforming to one perspective and being unwilling to raise dissenting opinions. However, because the research team investigated SMAs, the team determined that the group interview process would best approximate the interactions of the actual SMA in that participants would be sharing their perspectives with the researcher and other participants. In order to help maximize patient participation, the focus group leaders assured participants that their anonymity would be protected. Additionally, the facilitators strove to be encouraging, accepting, and inclusive of all participants. The protocol was approved by the group practice’s Institutional Review Board.

Potential participants were those who were scheduled to attend the SMA 3 weeks before the actual SMA. The focus groups were conducted immediately following the SMA to maximize potential participation. A total of 48 individuals were sent direct mail invitations to participate in the focus group after their SMA. After 2 weeks, participants were contacted by phone to ascertain their attendance at the focus group. In all, 30 individuals participated in one of the 5 focus groups. All focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were reviewed after each focus group. After 5 focus groups had been completed, the research team noticed that similar comments and themes were discussed at each focus group, and concluded that “thematic saturation” had been achieved—additional data served to reinforce existing conceptual constructions, but did not reveal new findings. From more than a dozen different SMA topics, the team selected the following topics as a representative sample of the topics offered by the group practice for the study focus groups: (1) prediabetes management, (2) type 2 diabetes management, (3) a 3-part SMA entitled Successful Aging that covered issues of concern for seniors (memory, falls, and depression), (4) mind-body management, and (5) men’s physicals. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. Patients were paid $50 for their participation.

The focus group questions were designed to investigate patients’ overall reactions to SMAs, as well as the benefits and shortcomings of the SMA format, privacy issues, comparing the SMA to a traditional office visit, and the impact of SMA attendance on health behaviors.

Analysis

All transcripts were analyzed in Atlas.ti 6.2 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The research team met biweekly to discuss study progress, emergent themes, and purposeful sampling strategy. Based on the study aims, an inductive codebook was developed by the research team to identify emergent themes from the data and was modified iteratively based on input from the coders and project team. Transcripts were coded at the paragraph level. Videos were used to annotate transcripts with participants’ behaviors to incorporate nonverbal communication. Disagreements in thematic coding were discussed until consensus was reached.

Results

Of the 48 SMA members who were contacted, 30 participated in the focus groups. Participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age of participants was 70. More than half of the participants were male and married, the majority were white, and 53.3% were college graduates or had postgraduate training. Additionally, participants were largely retired, and more than half had income greater than $75,000 and health insurance covered by a government program. Similar themes emerged across the 5 focus groups, despite differences in SMA topics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in Focus Groups Regarding Shared Medical Appointments

| Characteristic | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| AGE | ||

| Mean age, years | 70 | NA |

| Median age, years | 71 | NA |

| Minimum age, years | 52 | NA |

| Maximum age, years | 93 | NA |

| No answer | 1 | NA |

| SEX | ||

| Female | 10 | 33.3 |

| Male | 17 | 56.7 |

| No answer | 3 | 10.0 |

| MARITAL STATUS | ||

| Never Married | 4 | 13.3 |

| Separated | 1 | 3.3 |

| Divorced | 5 | 16.7 |

| Married | 17 | 56.7 |

| Widowed | 1 | 3.3 |

| Living as Married | 1 | 3.3 |

| No answer | 1 | 3.3 |

| ETHNICITY | ||

| African American | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 | 6.7 |

| White | 26 | 86.7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 3.3 |

| Native American | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 |

| No answer | 1 | 3.3 |

| EDUCATION | ||

| Less than 8th Grade | 0 | 0.0 |

| 8th Grade Graduate | 0 | 0.0 |

| High School Graduate | 1 | 3.3 |

| Some College | 11 | 36.7 |

| College Graduate | 7 | 23.3 |

| Some Graduate School | 2 | 6.7 |

| Completed Postgraduate | 7 | 23.3 |

| No answer | 2 | 6.7 |

| CURRENT EMPLOYMENT STATUS | ||

| None | 4 | 13.3 |

| Retired | 18 | 60.0 |

| Yes, Part Time | 2 | 6.7 |

| Yes, Full Time | 5 | 16.7 |

| No answer | 1 | 3.3 |

| ANNUAL INCOME | ||

| No income | 1 | 3.3 |

| ≤ $15,000 | 4 | 13.3 |

| $15,001–$25,000 | 2 | 6.7 |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 1 | 3.3 |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 2 | 6.7 |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 2 | 6.7 |

| $75,001–$99,999 | 6 | 20.0 |

| ≥ $100,000 | 10 | 33.3 |

| No answer | 2 | 6.7 |

| HEALTH INSURANCE COVERAGE | ||

| Currently Do Not Have | 0 | 0.0 |

| Employer (Self/Spouse) | 5 | 16.7 |

| Government Program (Medicare, Medicaid) | 17 | 56.7 |

| Military benefits | 0 | 0.0 |

| Self-Pay | 2 | 6.7 |

| Other | 1 | 3.3 |

| Combination Government & Self-Pay | 3 | 10.0 |

| Combination Employer & Government | 1 | 3.3 |

| No answer | 1 | 3.3 |

NA, not applicable

Main benefits of SMAs

Participants expressed many benefits to their participation in SMAs, as illustrated by the emergent themes of engagement with the physician and other patients, enhanced learning, and motivation for health behavior change.

Engagement with physicians and other patients.

Several participants expressed that they felt a change in the power dynamic between themselves and the physician after the SMAs. One reason suggested for the shift was the physician acknowledging an error in perspective or action: “He doesn’t have problems with admitting that he made a change in his thinking, or that maybe the folks that he’s offered before weren’t quite so helpful.” This resulted in putting the patient “at ease” so that they could then admit when they “screwed up.” Another participant felt less “intimidated” by his SMA physician because he was no longer “talking at” the patient but wanted to “learn from” the patient:

He doesn’t talk down to you—doesn’t act like he’s got this ego, that he knows so much and you know nothing. He’s actually trying to learn from us as well as we learn from him. So it’s more of we’re all on an even keel. (Female, 52 years old, mind-body management SMA)

Some participants felt that the additional “time” with the physician allowed them to “relax a little bit,” as the physicians were generally “so rushed”:

I find that nobody looks at their watch when they’re in here [SMA]. That’s an important issue. Sometimes when you have an appointment with the doctor on a one-on-one basis, you kinda get that feeling that you’re allowed so many minutes and then, next one. But in here I don’t feel that way. When we’re going through each individual person talking to the doctor, he’s able to devote that time directing his questions and finding out how you are doing individually. (Male, 66 years old, type 2 diabetes SMA)

Other participants reported new or strengthened emotional bonds with the physician as a result of their participation in SMAs. Many participants expressed that their participation in SMAs altered their relationship with their physician. Some said that they viewed their doctor as being more “human” after sharing information from the physician’s personal life:

The little details, like the fact that he’s teaching his son how to drive—this would not come out normally in a 15- to 20-minute, [laughter] but it makes him very, very human, which makes it easier to deal. (Male, 72 years old, mind-body management SMA)

One participant expressed that by getting to see this human side of her physician, she now felt more at ease for future visits:

You know him better after being with the three [SMA] sessions, and you’re more comfortable going in to see him after that because you feel you know him a little better as a person, as well as, of course, appreciating his expertise. That’s important for patients. (Female, 70 years old, successful aging SMA)

Arguably more important, participants also felt that the SMA provided an emotional connection to others with concomitant support for their health experience as they realized that they were “not the only one going through this.” One of the participants revealed, “I was isolated for two years, and I thought that nobody else was going through what I was going through. How can anyone possibly live through this kind of pain...it was the first time I’ve ever been in a group. It’s very good.” (Female, age 40–65, mind-body management SMA)

Enhanced learning.

Participants expressed increased educational opportunities coming from the physician, printed materials, and each other.

Many participants stated that they learned “a great deal more” about their health and well-being from the SMA as compared to a regular 15- or 20-minute visit. “So much more information” and “more time” meant that the physician was able to “enlighten you onto new ideas” and “expand your mind, so that you have greater understanding.”

Participants also liked being able to refer to printed copies of the information presented, which they felt were more available than at a traditional visit:

All the stuff that’s up there that he’s going over, it’s printed out. If some of you want to go back, it’s there, that you can go back later on and look at it and refresh....If you’re going to a doctor’s appointment, they’re not giving you all—there’s no way. (Male, 66 years old, mind-body management SMA)

Besides knowledge gained from the physician, participants liked that they were able to “learn from others.” Hearing other SMA participants’ experiences provided a “diversity of solutions” that “one physician cannot supply,” as was repeatedly emphasized by one participant:

They [the group] come up with an amazing variety of proposed solutions to the problems...it gives you a perspective that is a lot greater and frankly, in many cases, a lot more helpful than just a one-on-one visit with your own doctor. (Male, 78 years old, prediabetes SMA)

Hearing from multiple individuals “magnified” the information and “made it better,” resulting in a “synergy”: “I just knew that there was some power or benefit to being able to have the support of and hear the experiences of other people that are facing the same challenges” (Male, age 40–65 years, type 2 diabetes SMA).

Motivation for health behavior change.

Focus group participants also reported that participation in the SMA helped to increase their motivation to make changes to their health behaviors. Attending a recurring SMA helped to create “strong accountability” for one participant regarding his type 2 diabetes.

Others felt that SMA attendance helped to keep them “honest” about their actions. Another type 2 diabetes participant expressed that you “have...to come to these meetings [SMAs]...and be honest with yourself—‘Hey, I’ve been going off the wagon”’ (Female, age 40–65 years, type 2 diabetes SMA). Although missteps still occur, as noted by another participant, attending SMAs increased accountability:

Mostly I come...to keep me honest. I know that somebody’s gonna weigh me three months from now. That’s in the back of my mind...It keeps me trying anyway, whether it’s successful or not. (Male, 78 years old, prediabetes SMA)

As a result of knowledge gained from the SMA, some participants reported adopting lifestyle modifications, specifically preventing falls and maintaining memory. One participant added “adaptive devices” of bars and a few straps to assist with standing and sitting in his home. Another continued taking Tai Chi classes after learning at the successful aging SMA how it provides stability to help keep one from falling. One other participant told how “saying out loud” and/or making notes about an action, such as where he had put his keys, “helped” with memory retrieval. After hearing other participants’ coping strategies, a former military officer described how his internal paradigm shifted, leading to his behavior change:

[T]here was just an attitude that changed how I conducted my life. When I was walking, I took a little more time rather than just striding out there like I used to. I was more careful in how I went about my walking. So it’s [SMAs] very important, and it made quite a difference. (Male, 84 years old, successful aging SMA)

Other participants expressed planned behavioral modifications, such as one patient who said that he will, “...definitely cut back on those things [cereal and flax seed breads]” but in a way that fits his lifestyle: “But I’m still gonna have my peanut butter sandwich once in a while...It’s just it won’t happen every day” (Male, 69 years old, men’s physical SMA). Another felt that “the kind of stuff I learned here...will prevent me from having to see him [his physician] as often” (Male, 64 years old, mind-body management SMA).

Exposure to others with the similar issues provided normalization of their situation:

In my own case, I’m getting to the point where I start forgetting things, so it was nice to have the group around. Everybody else forgets things. By the end of the SMA meeting, I was feeling that I was pretty average. I’m not Alzheimer’s yet. (Male, 82 years old, successful aging SMA)

Improved satisfaction and reliance on the delivery organization.

Participants reported high degrees of satisfaction with comments like, “I really enjoyed [it]” and, “It works and I get a hell of a return on my investment.” One participant summarized,

I think it does enhance the relationship between me and the medical group. It tends to make me rely more on them; it increases my respect for them and my inclination to come back for whatever the next problem is. I think it’s a positive addition to the services that the medical group renders. (Male, 78 years old, prediabetes SMA)

Participants concerns and fears about SMAs

Despite the numerous benefits of SMAs, several participants acknowledged that there were situations when they might not attend an SMA based on the topic, and there were mixed sentiments about attachment to their primary care providers.

Fear of loss of privacy.

A few participants expressed that they would not participate in an SMA if it was a “real personal topic”—one that they would “not want to address in front of a number of people.” When probed about what constitutes a “personal topic,” one participant revealed:

Years ago, I have some problems, and I need to see a psychiatrist here. They said well, we have a group practice going on here. You can join, and you can talk to anybody, and I flatly refused. I don’t want to talk about what is bothering me with a group of strangers...But just—there are some things that makes me uncomfortable to talk with a group of people I don’t know very well. (Female, 75 years old, successful aging SMA)

But one participant expressed that this fear of sharing could potentially change given someone else sharing their experience:

I just noticed that, listening to the other people, they brought up some things that may have related to me that I felt were my weaknesses or things that I did that I wouldn’t wanna disclose because I might feel a bit of shame or embarrassment, but after hearing other people be open and honest, I think it gives me—or just allows you to be more honest yourself because you’ve already heard other people expose themselves or be honest. (Male, approximately 60 years old, type 2 diabetes SMA)

Fear of worst case scenario.

A first time SMA attendee who had prostate cancer expressed that he would probably not attend another prostate cancer SMA because of the possibility of hearing discouraging stories that would not aid his recovery:

The meetings...can be very, very productive, or they can be really, really negative...Some of the guys that are in there, it’s just so horrific what’s happened to them...here’s guys that were—had progressed, let’s say, ten years past where you are now. Would you want to go to that meeting and see those guys and what you might have to be like then? You just don’t want to go. (Male, 68 years old, men’s physical SMA)

Varying degrees of attachment to primary care physician.

Several participants reported that their attendance was based on their personal physician leading the SMA and wanting to show their support: “Well, I came mainly because I wanted to support Dr. X, in the sense that he started this. I’ve been to most of them and would hate to see it go away for lack of attendance.” One stated that they attended the SMA because it’s “something that he’s sort of recommending, why not do it?”

When questioned about how they would feel about going to an SMA led by a doctor they didn’t know, one participant replied, “I wouldn’t do it...no, I wouldn’t. Why would I go and see a new guy, when I spent ten years with [my doctor] and he knows me pretty well?” (Male, 69 years old, men’s physical SMA). However, one participant said that “...it wouldn’t make a difference” who was leading the SMA because “...if somebody else can come in and do as good a job as Dr. A, that’d be fine with me” (Male, 78 years old, prediabetes SMA).

Discussion

The majority of SMA participants felt that they received numerous tangible and intangible benefits from them, particularly the enhanced engagement with physicians, learning, motivation for health behavior change, and the value of connecting with others, which is similar to the benefits from a focus group of US military veteran SMA participants.15

The research team was surprised by the extent to which patients felt that the SMA altered their relationship with their physician. Most importantly, the power dynamic between patient and physician was redistributed as the patient now viewed himself or herself as being able to impart information to the physician. Being able to see the more “human” side of their physician helped patients to feel more comfortable at future visits. This confirms what has been noted by other researchers, that SMAs “shift the responsibility away from the provider...as expert” to the patient “taking an active role in the process.”3,20 SMAs provide a concrete strategy for patient engagement and partnership in the care process.6

Several patients reported that they liked the aspect of “learning from others,” which has been shown to be “instrumental in facilitating positive lifestyle and behavioral changes.”3 What remains unknown and needs further research is the extent to which SMAs actually alter health behaviors beyond the initial self-reported enthusiasm. Some participants noted that current and future lifestyle modifications as a result of SMA attendance included changes in diet or walking to prevent falls. A few patients thought that SMA participation decreased their number of visits to their physician. A more quantitative analysis is necessary, involving examining medical records to determine if measurable clinical changes result from SMA participation. Additional measurements also should be taken of cognition, stability, and mood, so that the impact of the Successful Aging SMAs can be assessed. Other areas for future research include understanding the perspectives of those individuals who chose not to participate in an SMA as well as further understanding of the perspectives of primary care physicians on SMAs. Health plans also might want to compare quantitative patient satisfaction outcomes for SMAs versus usual care.

One of the main limitations of the study is the potential for selection bias for both those who chose to participate in an SMA and the focus groups. It is possible that participants who had a more positive view toward SMAs may have been more likely to agree to participate in the study. Another possible limitation is that those participants who did harbor dissenting views from those expressed in the focus group felt uncomfortable stating their perspective. But, given the open and frank comments the research team received, this is unlikely to be a serious drawback. Finally, these results might not generalize to other patients from other socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds as the study participants were mainly older, highly educated, and white, with more than half of participants earning more than $75,000.

Given the unfolding ACA and the existing primary care shortage, SMAs provide a way to improve access,4,6 improve relationships with physicians, and increase patients’ knowledge of their health; they also help ease the patient load for physicians. An earlier expansion of health insurance coverage, the 2006 Massachusetts health reform, showed that the primary care workforce was unable to meet the new demand for services,2,21 suggesting that “expanding health insurance coverage without expanding access to providers can lead to more problems than solutions.”2 Significantly expanding the use of SMAs is an innovative solution that can improve efficiencies, better use the scarce resource of primary care physicians, increasingly engage patients to learn from and teach one another, and connect more with their physician,3,4 and by extension, develop stronger affinities with the Accountable Care Organization where their physicians practice.

Acknowledgment

A previous version of this paper was presented at the HMO Research Network 2014 Conference, held in Phoenix, Arizona, in April 2014.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Stults, Frosch, Hung, Cheng, and Tai-Seale, and Ms. McCuistion declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant R18 HS019167 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

References

- 1.Schwartz MD. Health care reform and the primary care workforce bottleneck. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:469–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaissi A Primary care physician shortage, healthcare reform, and convenient care: challenge meets opportunity? South Med J. 2012;105:576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke RE, O’Grady ET. Group visits hold great potential for improving diabetes care and outcomes, but best practices must be developed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012; 31:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stempniak M Try shared medical appointments to help relieve MD shortage. Hospitals & Health Networks. 2013; 87:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noffsinger EB. Running Group Visits in Your Practice. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson B Shared appointments improve efficiency in the clinic. Manag Care. 2003;12:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartley KB, Haney R. Shared medical appointments: improving access, outcomes, and satisfaction for patients with chronic cardiac diseases. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaber R, Braksmajer A, Trilling J. Group visits: a qualitative review of current research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:276–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palaniappan LP, Muzaffar AL, Wang EJ, Wong EC, Orchard TJ. Shared medical appointments: promoting weight loss in a clinical setting. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:326–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin A, Cavendish J, Boren D, Ofstad T, Seidensticker D. A pilot study: reports of benefits from a 6-month, multidisciplinary, shared medical appointment approach for heart failure patients. Mil Med. 2008;173:1210–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Gierisch JM, Nagi A, Williams JW. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langwell KM, Moser JW. Strategies for Medicare health plans serving racial and ethnic minorities. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;23:131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: A quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman D, Fredrickson SK, Melnyk SD, et al. Medical clinics versus usual care for patients with both diabetes and hypertension: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 152:689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Hartley S, Mavi J, Vest B, Wilson M. Veteran experiences related to participation in shared medical appointments. Mil Med. 2012;177:1287–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohan D, McCuistion M, Frosch D, Hung D, Tai-Seale M. Recognition as a patient-centered medical home: fundamental or incidental? Ann Fam Med. 2013;11 suppl 1:S14–S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCuistion MH, Stults CD, Dohan D, Frosch DL, Hung DY, Tai-Seale M. Overcoming challenges to adoption of shared medical appointments. Pop Health Manag. 2014;17:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine MD, Ross TR, Balderson BH, Phelan EA. Implementing group medical visits for older adults at group health cooperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:168–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schensul JJ. Focused group interviews. In: Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD, Nastasi BK, Borgatti SP, eds. Enhanced Ethnographic Methods: Audiovisual Techniques, Focused Group Interviews, and Elicitation Techniques. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press; 1999:51–114. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emerson RM. Power-dependence relations. Am Sociol Rev. 1962;27(1):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenheimer T, Pham H. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]