Abstract

Background:

Most persons with dementia have multiple chronic conditions; however, it is unclear whether co-existing chronic conditions contribute to health-care use and cost.

Methods:

Persons with dementia and ≥2 chronic conditions using the National Health and Aging Trends Study and Medicare claims data, 2011 to 2014.

Results:

Chronic kidney disease and ischemic heart disease were significantly associated with increased adjusted risk ratios of annual hospitalizations, hospitalization costs, and direct medical costs. Depression, hypertension, and stroke or transient ischemic attack were associated with direct medical and societal costs, while atrial fibrillation was associated with increased hospital and direct medical costs. No chronic condition was associated with informal care costs.

Conclusions:

Among older adults with dementia, proactive and ambulatory care that includes informal caregivers along with primary and specialty providers, may offer promise to decrease use and costs for chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, depression, and hypertension.

Keywords: dementia, health utilization, longitudinal study, multiple chronic conditions, National Health and Aging Trends study, public health

1 |. INTRODUCTION

There is a growing body of evidence that persons with dementia have a higher burden of chronic conditions.1–3 Most persons with dementia have an average of 2.1 (standard deviation [SD] 1.9) other chronic conditions.4,5 Not surprisingly, as the number of other chronic conditions increases, so do their costs compared to older adults without dementia.1,2,6 For acute care (hospital, skilled nursing facility, and home health), the relationship is exponential among individuals identified as having dementia through claims data versus cognitively intact individuals.2

In 2010, 13% of Medicare beneficiaries had two or three chronic conditions and incurred ≥1 hospitalization, with total costs of more than $57 billion (19% of Medicare spending). Among the 14% of Medicare beneficiaries with ≥6 chronic conditions, costs were >$140 billion (46% of Medicare spending).7 Poor management of multiple chronic conditions increases the risk of hospitalization2,8,9 and dependence in functional activities.10,11 Acute hospital admissions are an indicator of poor health and serve as valuable markers to assess the quality of chronic disease management and care coordination.12–16 Persons with multiple chronic conditions are vulnerable to exacerbations of, and complications from, their underlying disease, and are susceptible to other acute illnesses, some of which may be potentially averted.2,12,17 For persons with dementia, the rate ratio of all-cause hospitalization (incidence rate in persons with dementia divided by the incidence rate of people who are cognitively intact) is 41% greater than for cognitively intact older adults. Moreover, persons with dementia experience worse physical function after hospitalization.18,19

A recent systematic review3,20 identified 55 gaps in the literature evaluating the effect of dementia on disease management, mobility, and mortality. The expert panel identified as “highest priority for future research: service utilization-hospitalizations, disease-specific outcomes, diabetes, chronic pain, cardiovascular disease, depression, falls or fractures, stroke, and multiple chronic conditions (the presence of moderate-to-severe dementia and more than two other chronic conditions).”3 Parsing out use and costs associated with common chronic comorbid conditions is particularly important because for persons with dementia: (1) it is unknown which chronic conditions are associated with higher rates of hospitalizations, (2) it is unknown which chronic conditions incur higher costs, and (3) it can direct future research to manage these chronic conditions, which may include new interventions with clinicians in primary and specialty ambulatory care, homecare, and caregivers of persons with dementia. This study aims to address these identified gaps using a longitudinal, nationally representative dataset to examine the association of chronic conditions with hospitalization and costs among persons with dementia and two or more comorbidities.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data sources

Four annual waves of National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) were merged with Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Claims Data from 2011 to 2014.21 The NHATS is an ongoing nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries designed to understand trends and trajectories of late-life disability.21 Annually, it conducts interviews assessing participants’ physical functioning, social support, and demographic information.

Medicare claims that were linked to the NHATS included validated chronic conditions; emergency outpatient visits; hospital, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, hospice, and home health use; and costs.22

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Yale IRB (HIC# 1510016585). All human subjects provided informed consent.

2.2 |. Study population

The study population included NHATS respondents who were 65 and older who were Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries and whose NHATS’ data were linked to CMS.21 Medicare managed care enrollees were excluded because no claims data were available. For the current study, we included 810 NHATS participants with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other related disorders based on the CMS definition7,23 that had at least two other chronic conditions between 2011 and 2014. We chose chronic conditions based on the definition of “conditions that last a year or more and require ongoing medical attention and/or limit activities of daily living.”3,24,25

2.3 |. Measures

We used the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse algorithm “Alzheimer’s disease and other related disorders or senile dementia” to create our cohort population. Valid International Classification Diagnosis (ICD) −9 and −10 codes, Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition / or The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes include: DX 331.0, 331.1, 331.11, 331.19, 331.2, 331.7, 290.0, 290.10, 290.11, 290.12, 290.13, 290.20, 290.21, 290.3, 290.40, 290.41, 290.42, 290.43, 294.0, 294.1, 294.10, 294.11, 294.8, 797 in at least one data claim files such as: inpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health agency, hospital outpatient, or Carrier claim using a 3-year reference period.26 This 3-year reference period includes the indicated year (eg, 2011) plus the two previous years (eg, 2009 and 2010), which did not require full Medicare fee-for-service coverage.

Sixteen time-varying chronic conditions from Chronic Condition Data Warehouse between 2011 and 2014 were acute myocardial infarction, asthma, atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, diabetes, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, ischemic heart disease, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, and stroke or transient ischemic attack.22 A description of the methodology to ascertain each chronic condition can be found at the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse website.26 Briefly, validity of each chronic condition from the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse is based on algorithms that include a reference period to accumulate ICD-9, Current Procedural Terminology (4th Edition), and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (Level II) codes, and the number and types of claims.26 Thus, the claims data depend on service delivery and accurate coding of the reason for treatment.

Using the above definitions, when a NHATS participant met the criteria for dementia and two chronic conditions during 2011–2014, they were included in the analytic cohort. We evaluated the correlation of all 16 chronic conditions and there was minimal correlation, with the highest between heart failure and ischemic heart disease (ρ = 0.35) with a ρ < 0.1; thus, we did not expect variance estimation problems. Not all potential chronic condition combinations occurred; there were 375 unique combinations at baseline.

Baseline fixed demographic characteristics considered for all models included the following: age band (5 years incremental variable, starting at 65 years), sex, race (non-Hispanic white vs other), education (less than high school vs high school or greater), environment (urban vs rural), residence type (community vs residential care), and activities of daily living (ADL) score (a count of needing help or unable to perform: eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, transferring from bed, getting around inside one’s home).

2.4 |. Hospitalizations and total costs

The primary outcomes were an annual count of hospitalizations, hospital costs, annual direct medical costs, informal care hours’ costs, and annual societal costs. The number of hospitalizations per year was matched to the initial NHATS interview date. Hospital costs include all costs accrued per calendar year from the Medicare inpatient file. Direct medical costs from 2011 to 2014 were extracted from Medicare files by calendar year and adjusted to 2017 United States dollars using the Consumer Price Index. These costs included: hospital care, skilled nursing facility stays, home health, hospice care, physician services, outpatient care, and non-institutional claims (eg, physicians, assistants, medical support staff, free-standing ambulatory surgical center, and durable medical equipment). The direct medical costs reflect the total amount due to the provider; therefore, they include payments from Medicare, the beneficiary, and third parties (eg, commercial private health insurance). Societal costs are defined as the sum of indirect non-health-care costs that include informal caregivers’ time and direct medical costs. Participants were asked about days and hours in the last month each helper spent doing mobility, self-care activities, and household activities; providing transportation; and helping with medical-care related activities.27 The total time spent caring was updated annually. Sensitivity testing was performed using the federal minimum wage ($11) as the base costs and ($7.25) for the sensitivity analysis, that covers 45 states.28 The total number of hours per month was multiplied by the federal minimum wage and scaled to annual costs per person to reflect total annual societal costs.

2.5 |. Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed in Stata v1529 with two-sided tests of significance. Descriptive statistics compared baseline demographics of the cohort using survey-adjusted statistics to allow generalization to the population.30 To address non-response over time in the NHATS-CMS merged data, we fit response propensity models (using survey logistic regression) that predicted response in the 2014 wave using baseline 2011 characteristics associated with a P-value of <0.20.31,32 The 2011 survey weights were used to estimate the response propensity parameters; then, we computed predicted probabilities of response based on the weighted parameter estimates.31,33 The 2011 survey weights were then multiplied by the inverses of the mean estimated response probabilities within deciles of the response probabilities. Deceased persons’ costs and number of visits in years after death were set to zero.31 For the longitudinal analysis, we multiplied the NHATS analytical weights by the inverse probability of response in 2014 to adjust for non-response and included the stratum as a covariate.31 Total number of annual hospitalizations were modeled using a weighted generalized eEstimating equations (GEE) Poisson regression to account for the repeated measures; this resulted in adjusted risk ratios (aRR). Rates using the margins command in Stata were calculated.29 Direct medical and total societal costs were similarly modeled using a weighted GEE model with a Gaussian family and identity link. The distribution was determined by plotting residuals and the predicted response probabilities to determine the best fit. Each model’s covariance structure was determined by the lowest quasi-information criterion. This study used an unstructured covariance structure for number of hospital visits and an exchangeable covariance structure for cost outcomes. We used a weighted generalized estimating equation panel–data (XTGEE) model with robust standard errors and the adjusted analytical weight. All models included the 16 time-varying chronic conditions and were adjusted for sex, age band, education, race, and urban environment. Residence type and activities of daily living were multiply correlated with chronic conditions, and thus were not included in the models. To adjust for five inference tests on the chronic conditions, we applied a Bonferroni correction (0.05/5 = 0.01) method.

3 |. RESULTS

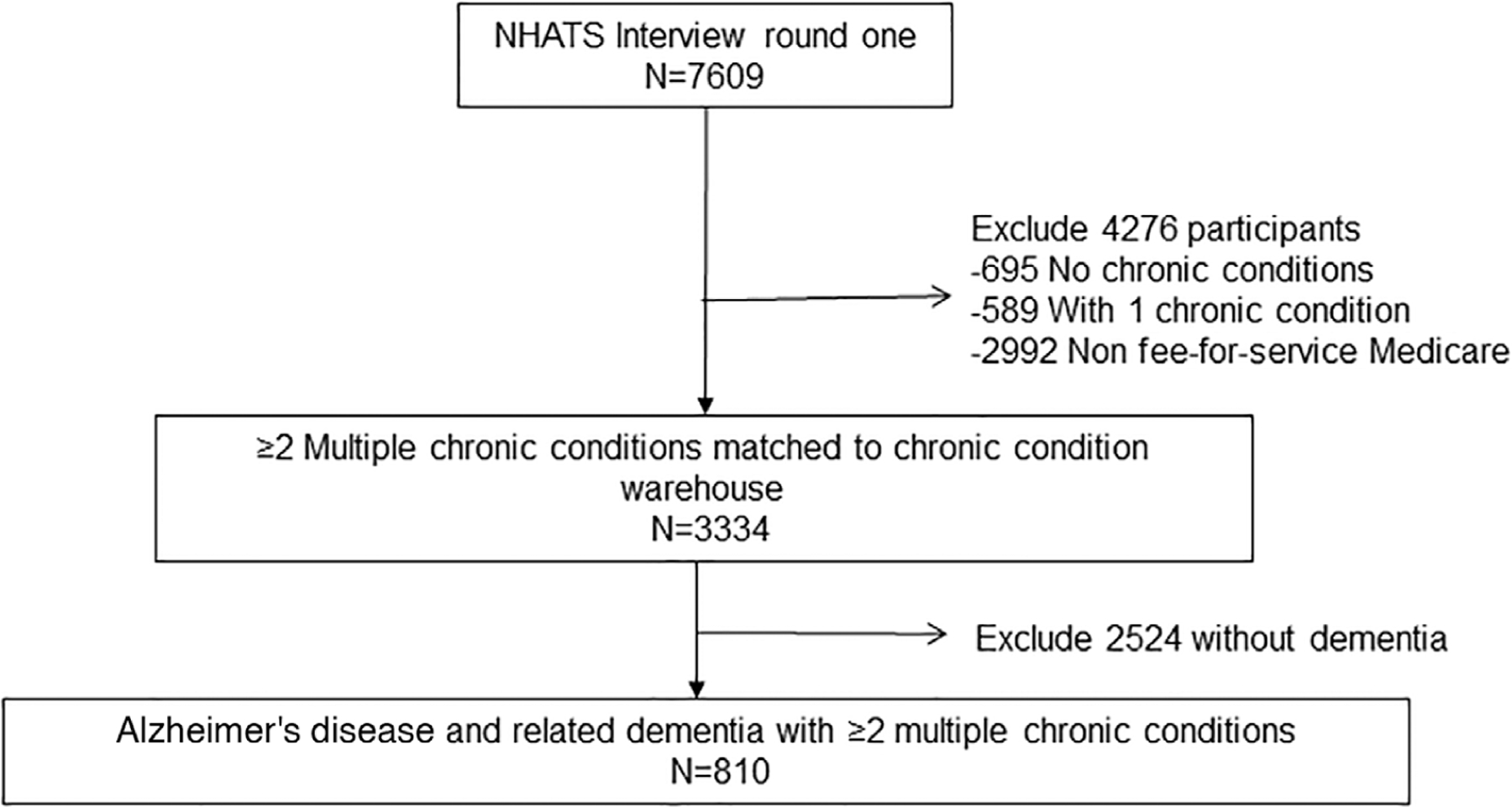

A total of 810 NHATS participants met eligibility criteria and were included in analyses (Figure 1); of these 126 (15.56%) discontinued follow-up and 433 (53.46%) died prior to the end of the study period (2014). The average follow-up was 2.7 waves of data (out of four waves). The median duration of follow-up was 27 months (interquartile range [IQR], 13–38 months).

FIGURE 1.

Consort diagram of persons identified with “Alzheimer’s Disease, related disorders, senile dementia” (n = 810) by Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (2011) merged with the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS)

3.1 |. Demographic characteristics of the NHATS sample

The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The cohort generalizes to approximately 2.9 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries living with dementia with at least two chronic conditions during 2011 to 2014. As expected, cardiovascular conditions were the most prevalent with 86.4% having hypertension, 66.8% having hyperlipidemia, and 54% having ischemic heart disease; 37.5% had ≥6 conditions. Notably, more than 40% were ≥85 years old, 92.4% had ≥1 informal caregiver, and 74.2% had a medically supportive care partner.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with dementia identified between 2011 and 2014 with two or more chronic conditions, participating in the National Health and Aging Trends Study

| Characteristics | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Estimated sample population | 2,965,842 |

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age band | |

| 65–69 | 5.2 |

| 70–74 | 15.2 |

| 75–79 | 17.8 |

| 80–84 | 21.6 |

| 85–89 | 25.9 |

| 90+ | 14.8 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36.3 |

| Female | 63.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 81.3 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9.0 |

| Hispanic | 6.2 |

| Other | 3.4 |

| Education | |

| ≥ High school | 68.8 |

| <High school | 31.1 |

| Residencea | |

| Community | 79.7 |

| Residential care | 20.3 |

| Paid caregivers | |

| No | 77.9 |

| Yes | 22.1 |

| Presence of a medically supportive care partnerb | |

| No | 25.8 |

| Yes | 74.2 |

| Number of informal caregivers | |

| 0 | 7.6 |

| 1–2 | 65.3 |

| 3+ | 27.1 |

| Activities of daily living score (0–6)c | |

| 0 | 55.5 |

| 1 | 13.4 |

| 2 | 8.8 |

| 3 | 6.1 |

| 4 | 3.4 |

| 5 | 4.9 |

| 6 | 7.7 |

| Chronic conditionsd | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.6 |

| Asthma | 6.6 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 17.7 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 11.1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 24.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 29.4 |

| Depression | 27.8 |

| Diabetes | 39.6 |

| Heart failure | 38.3 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 66.8 |

| Hypertension | 86.4 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17.6 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 54.0 |

| Osteoporosis | 16.0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 53.9 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 11.5 |

| # of chronic conditionse | |

| 2–3 conditions | 27.2 |

| 4–5 conditions | 35.2 |

| 6+ conditions | 37.5 |

Residential care is a retirement community that offers meals, and helps with medications or self-care. This could be a stepped-care facility, a group home, supervised care housing facility, or an assisted living facility.

The definition of a medically supportive caregiver is someone who goes to physician appointments and/or helps person with dementia with prescription medication.

The definition of disability is a deficit in eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, transferring from bed, getting around inside one’s home. Higher scores indicate greater disability.

Chronic conditions were based on Chronic Condition Data Warehouse.

Chronic condition was the sum score of listed 16 conditions.

3.2 |. Costs breakdown of the NHATS sample in 2011

Table 2 reports the 2011 breakdown of unadjusted costs. Hospital costs covered by Medicare were the highest average costs for direct medical costs. Total cost for hours of informal care spent on activities of daily living were similar to total direct medical costs.

TABLE 2.

Breakdown of 2011 costs per beneficiary (95% confidence intervals) for persons with dementia and at least two chronic conditions using fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the National Health and Aging Trends Study

| Total group | Costs paid by Medicare | Costs paid by beneficiary | Costs paid by primary payer other than Medicarea | Total costs paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital costs | 6,480 (5,458; 7,502) | 653 (541; 765) | 230 (−125; 586)b | 7,364 (6,319; 8,408) |

| Nursing home costs | 3,189 (2,542; 3,836) | 551 (386; 715) | 3,470 (2,957; 4,523) | |

| Hospice costs | 434 (217; 651) | 434 (217; 651) | ||

| Home health | 2,700 (2,213; 3,187) | 2,700 (2,213; 3,187) | ||

| Outpatient costs | 2,161 (1,871; 2,453) | 570 (492; 650) | 16 (1; 32) | 2,749 (2,383; 3,115) |

| Non-institutional provider costsc | 4,299 (3,903; 4,696) | 1,176 (1,074; 1,278) | 6 (−2;13) | 5,480 (4,984; 5,975) |

| Direct medical equipment | 481 (346; 616) | 136 (102; 169) | 616 (448; 785) | |

| Total direct medical costs | 19,748 (17,677; 21,818) | 3,086 (2,755; 3,417) | 252 (−107; 6111) | 23,085 (20,846; 25,323) |

| Total cost of informal IADL and ADL hoursd | 21,718 (19,113; 24,324) | |||

| Total societal cost | 44,786 (40,935; 48,639) |

Notes: Based on a subpopulation of 810, these estimates extrapolate to 2.9 million fee-for-service beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias and at least two chronic conditions. Estimates are calculated with 2011 balanced repeated replicates and Fay’s modification factor based on National Health and Aging Trends Study guidelines.

A primary payer other than Medicare represents the amount a primary payer (eg, the Veterans Administration or TRICARE) paid for services on behalf of the beneficiary.

When claims have a negative payment the beneficiary deductible and coinsurance exceeded the total payment amount due to the provider.36

These are costs identified in the Carrier file containing claims data for non-institutional providers (eg, physicians, physician assistants, clinical social workers, nurse practitioners, independent clinical laboratories, ambulance providers, and free-standing ambulatory surgical centers).36

Participants were asked about days and hours in the last month each helper spent doing mobility, self-care activities, household activities, providing transportation, and helping with medical-care related activities.27 We used the minimum wage ($11) as the base costs.28 The total number of hours per month was multiplied by the federal minimum wage and scaled to annual costs per person.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living

3.3 |. Hospital costs and adjusted rates (per 100 person-years) for the annual number of hospitalizations

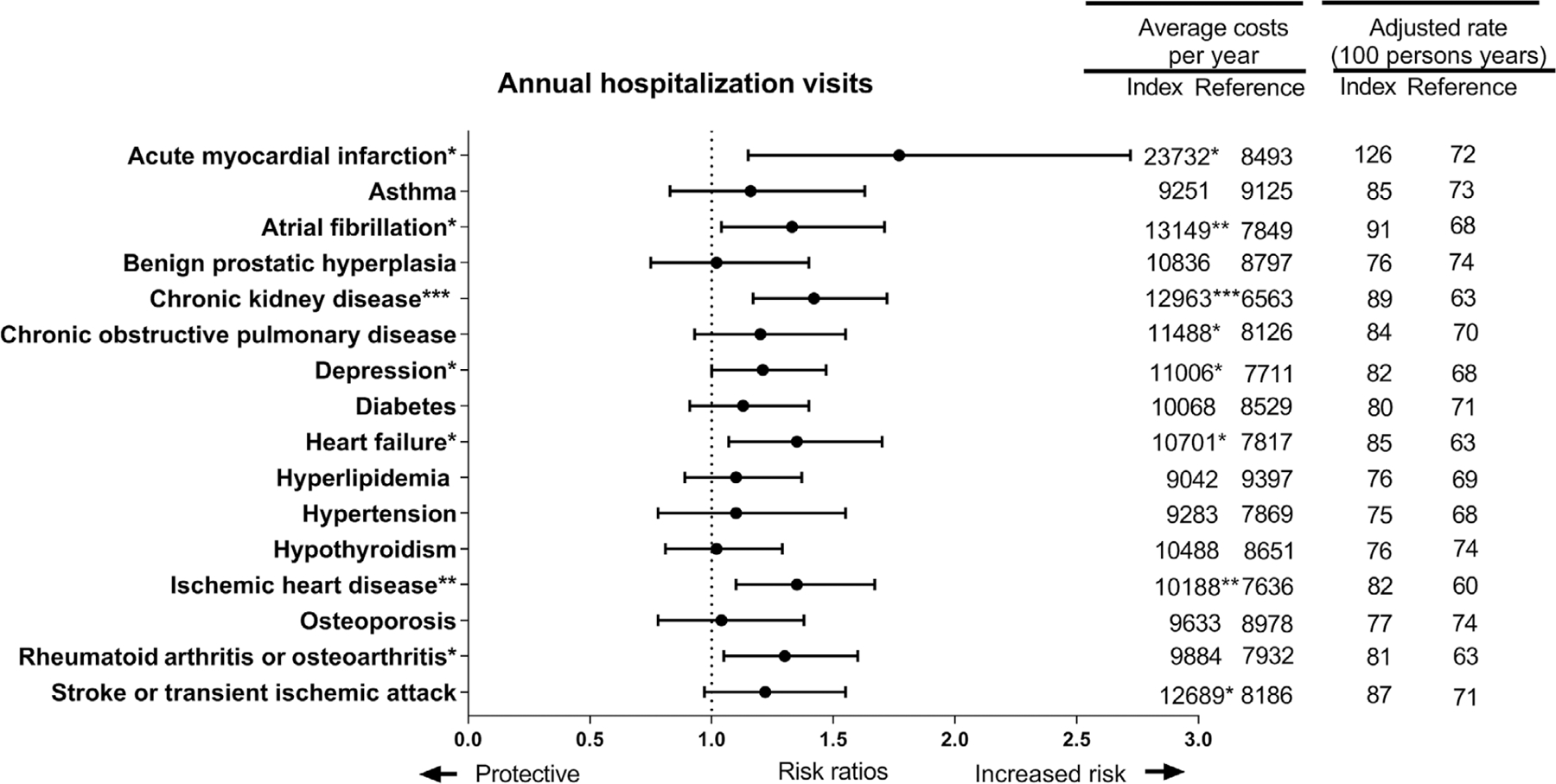

Figure 2 shows aRR, annual average hospital cost, and adjusted rates per 100 person-years for the annual number of hospitalizations for the presence of each specific chronic condition compared to the absence of the specific chronic condition. After adjusting for the multiple comparisons, chronic kidney disease and ischemic heart disease were associated with the highest annual number of hospitalizations and had higher costs. Atrial fibrillation was associated with higher hospital costs.

FIGURE 2.

Risk, rates, and costs of hospitalization for multimorbid persons with dementia among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2011 to 2014. The figure shows adjusted risk ratios from a weighted generalized estimating equations Poisson regression and rates. Hospitalization cost estimates are based on weighted generalized estimating equations regression with Gaussian distribution. Regression models included all 16 chronic conditions, sex, age band, education, race, urban environment, and were weighted for drop-out. * indicates that the marginal weighted estimate was significant at P < 0.05; ** is a P < 0.01, the significance level adjusted for multiple comparisons; and *** is a P < 0.0001

Prior to the multiple comparison adjustment, acute myocardial infarction, depression, and heart failure were associated with an increased annual number of hospitalizations and had higher hospital costs. Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis was associated with a higher number of hospitalizations and stroke or transient ischemic attack was associated with high hospital costs.

Conditions associated with the highest hospital costs and aRR of hospitalization visits were acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and chronic kidney disease.

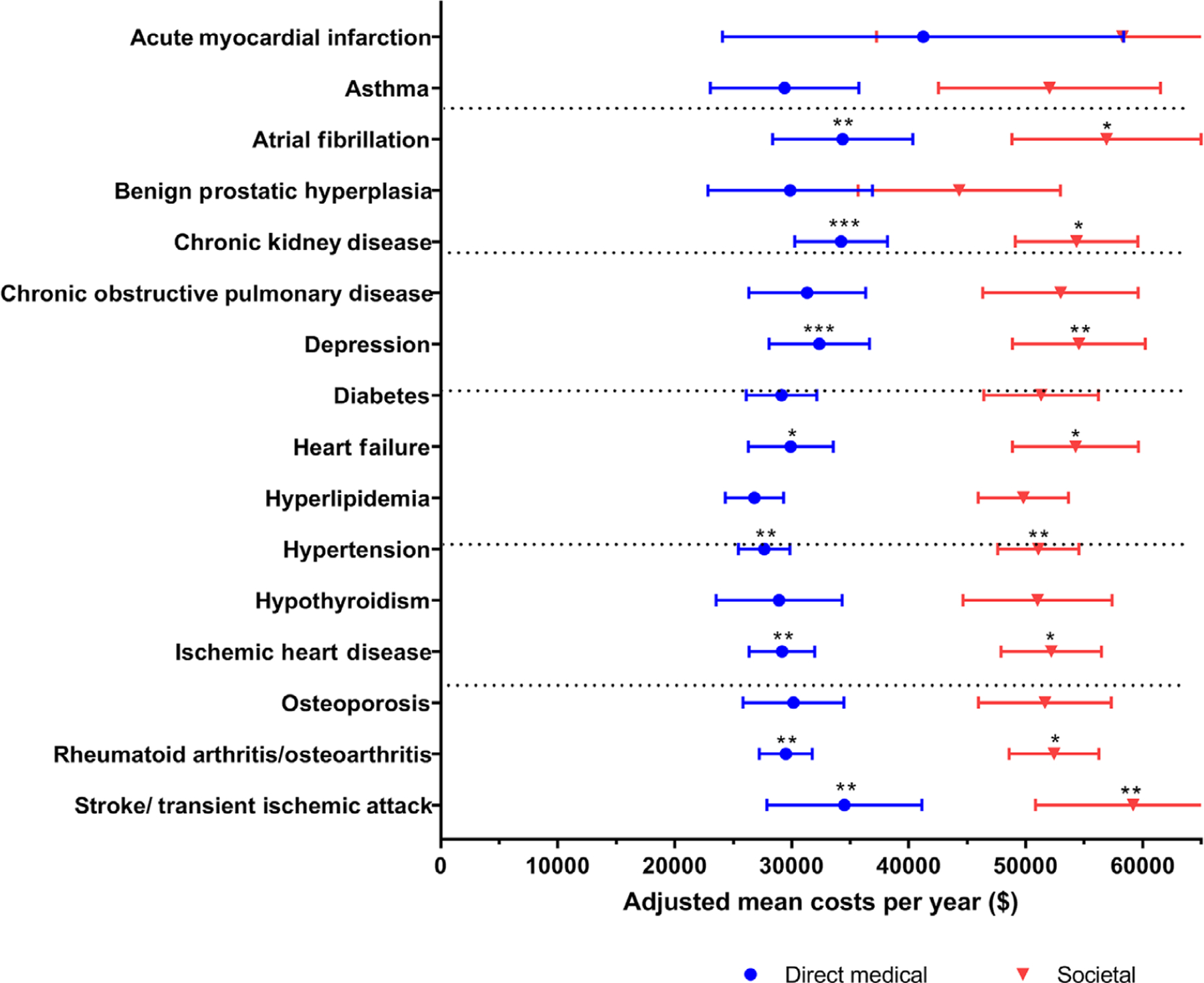

3.4 |. Annual direct medical, informal care, and societal costs

Figure 3 shows adjusted mean annual direct medical and societal costs. After adjustment of multiple testing, direct medical and societal costs were significantly higher for people with depression, hypertension, and stroke or transient ischemic attack (Figure 3). People with atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis were also associated with higher direct medical costs. There were no chronic conditions associated with informal care hours after adjusting for the multiple comparisons.

FIGURE 3.

Predicted annual average direct medical costs and societal costs for multimorbid persons with dementia among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2011 to 2014. The figure shows predicted annual average costs based on three weighted generalized estimating equations regressions: (1) direct medical costs; (2) societal cost model, which is the sum of the direct medical costs and informal care costs. Regressions included all 16 chronic conditions, sex, age band, education, race, urban environment, and were weighted for drop-out.* indicates a P < 0.05, ** indicates that the marginal weighted estimate was significant after adjusting for multiple testing, *** P-value < 0.01. The bars in the figure represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean costs

Prior to multiple comparison adjustment, adjusted mean annual direct medical and societal costs were significantly higher in atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was associated with higher direct medical costs. Hypertension was associated with increased informal care hours.

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Main findings and interpretation

This research investigates use patterns for persons with dementia and multiple chronic conditions, which was previously identified as a high priority evidence gap.3 In this nationally representative, longitudinal, prospective study of multimorbid older adults with dementia, chronic kidney disease and ischemic heart disease were significantly associated with increased aRR in annual hospitalizations, hospitalization costs, and direct medical costs. Depression, hypertension, and stroke or transient ischemic attack were associated with direct medical and societal costs while atrial fibrillation was associated with increased hospital and direct medical costs. The chronic conditions with the highest significant direct medical costs were atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. No chronic condition was associated with informal care costs. It is important to note that 53% of the study population died during follow-up.

Dementia occurs frequently in people with chronic kidney disease.34–38 A substantial proportion of this population cohort (29%) had chronic kidney disease. Dementia is associated with an increased risk of death in individuals with end stage renal disease39 and in dialysis patients.37 Hospitalization is often required for older adults with glomerular diseases due to comorbidity and higher risk of cardiovascular complications. When indicated, an antihypertensive regimen, diuretics, and strict dietary salt restriction is recommended; however, for persons with dementia this may be difficult to perform unaided.38 Closer ambulatory monitoring by a primary care physician or a nephrologist may be impactful in reducing hospitalizations and costs.

Halling and Berglund40 found that patients treated for ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, or heart failure had a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment and a higher risk of developing early cognitive impairment. In this study population, 54% had ischemic heart disease at baseline. A previous review assessed the association between dementia and heart disease, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, and heart failure.41 The authors stressed that several of these conditions were preventable and treatable. In addition to medical therapies such as anti-hypertensive drugs, lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise may delay the onset of dementia. European guidelines on treatment of ischemic heart disease recommend a wide-ranging management approach, including “pharmacotherapeutic and invasive or surgical therapies, professional lifestyle interventions based on behavioral models of change, with different strategies from more basic, family-based to more structured and complex modalities, depending on the cardiovascular risk assessment and on concomitant diseases.”42 Physical activity advice, psychosocial support, and appropriate prescription of and adherence to cardio-protective drugs are deemed integral to maintaining and improving quality of life.42 In this study, persons with dementia and ischemic heart disease had high use and costs. Proactive targeting of this population could potentially reduce costs and use. However, treatment and monitoring may be more difficult in this population. For example, implementing an exercise regimen in persons with dementia and apathy may be difficult for informal caregivers and psychosocial support may not be realistic due to cognitive impairment. Closer monitoring by a primary care physician or cardiologist, as well as regular communication with family or informal caregivers, may be helpful in identifying a feasible, effective regimen based on individual patient characteristics.

Depression was associated with increased costs. There are treatments that are recommended to prevent complications. A previous review article43 summarized current treatment options for depression in people with dementia. A successive approach to the treatment is advocated including: (1) close observation for mild symptoms, (2) psychosocial interventions, (3) medication trial if symptoms more severe or psychosocial interventions fail, and (4) consideration of electroconvulsive therapy for extreme or refractory symptoms.43 However, effective treatment requires greater proactive care.

Dementia is of practical significance in clinical management as it may interfere with self-care, active decision making to maintain health, dealing with incident disease, and changing personal behaviors or seeking treatment if necessitated by worsening symptoms. Deficits in cognition may be related also to increased mortality, higher rates of hospital admission, and functional impairment.44 Although we did not have data on the management of these chronic conditions, potential explanations for the findings can be postulated. Symptom reporting or manifestations may differ in persons with dementia or depression, so the worsening of ischemic heart disease or chronic kidney disease may be undetected until a later stage, prompting emergency department visits resulting in hospitalizations.5,45 Better training of caregivers to detect signs and symptoms of worsening of underlying disease or adverse medication effects, may facilitate earlier detection, thus, allowing management in an ambulatory setting, rather than requiring hospitalization. Although this may increase use of ambulatory visits, this could be less expensive and/or less traumatic to patients and their families, than hospitalizations.

Kuo et al46 compared total medical costs for patients with AD (n = 25,109) with a demographically matched, cognitively intact control group using Medicare and private insurance data. They found cardiorespiratory arrest, hematological disorders, and diabetes to have the highest cost. Kuo et al46 evaluated 184 conditions in a cross-sectional study, while this study longitudinally evaluated 16 co-occurring chronic conditions, which did not include hematologic disorders nor found diabetes to have significantly higher costs among multimorbid older adults with dementia.

No chronic condition was associated with informal costs. This may be due to how the informal care costs were calculated, which was based on the number of hours a caregiver spent on (instrumental) activities of daily living (IADL).47 Previous literature found that informal care costs increased based on ADL disability; however, the study did not control for other chronic conditions.48 With a diagnosis of dementia, the dementia itself may be the dominant influence on costs and not these chronic conditions. Certain complications of dementia, like risk of falls or urinary incontinence, may result in further ADL or IADL difficulties.49

Strengths and limitations

This is a nationally representative longitudinal cohort that accounted for drop-out by adjusted, survey sampling weights. Not at random missing data leads to biased results; however, our research study used multiple methods to address missingness.31 Moreover, this study used a range of participant characteristics including time-varying covariates, annual visits over 5 years, and validated dementia and chronic condition measures. Using the Medicare data, end of life medical costs would also have been captured. We used the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse algorithm for AD and other related disorders or senile dementia26 allowing the results to have implications for population health and interventions at the health systems level, as this population is easier to identify using claims or medical records. However, it limits our results to older adults having a diagnostic code within the past 3 years.50 We are unaware of other studies that have used a nationally representative cohort to examine the association of individual comorbidities in a dementia population with at least two chronic conditions.

This study has some limitations. The CMS data linked to NHATS were specific to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries as data were not available for study participants covered under Medicare Advantage plans, but weighting allows for estimates to be generalized to the fee-for-service population. Second, the CMS cost data did not include the costs of assisted living facilities or paid caregivers, which are typically borne by the person or their family; thus, our estimates are likely conservative. Third, we did not include opportunity costs of informal caregivers, although we used two wage estimates. Fourth, we did not separately model prevalent versus incident conditions; however, at baseline 28.5% had six of more prevalent conditions. Last, we present associations with health-care use, which do not imply causation.

4.2 |. Potential implications for researchers, clinicians, planners, and policy makers

Previous research evaluating dementia, comorbidities, and health services use has recommended increased ambulatory care management.2 Geriatricians could have greater involvement with the co-management of persons with dementia who have complex comorbidity, as exemplified by evidence-based programs, such as collaborative transdisciplinary team dementia care approaches.14,51 However, reducing health-care use, particularly hospitalization, and costs for persons living with dementia are challenges that many evidence-based strategies and models of care have yet to achieve. Thus, use of care management alone may not necessarily decrease use and costs unless strategies are refined to better target these goals. Identifying chronic conditions that increase risk of use and higher cost is essential to developing more effective strategies.

As multiple chronic conditions are common in persons with dementia, it is important that we identify informal caregivers that are assisting not only with activities of daily living, but with the medically supportive tasks of attending medical appointments and helping with prescription medication.52 In this study, at baseline 74.2% had someone who performed one or both medically supportive tasks. This is important because many informal caregivers may be taking on medical care tasks, yet few informal caregivers have any medical training.53 Recently, as reported by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, caregiving tasks have expanded to providing self-care tasks, being a surrogate medical decision maker, and providing specialized medical care.54 They further report that 65% of high-need older adults require help with medication management, 20% need help with medical tasks, and 35% need help with wound care. Yet they found that “availability and preparedness of caregivers can affect the quality and course of care recipients’ post-hospitalization care and that caregivers are often underequipped.”54 Training informal caregivers in tailored, daily-care management strategies and to detect symptom exacerbation of chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, depression, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and stroke or transient ischemic attack may lead to reductions in hospitalizations and/or costs. The potential benefits of appropriately trained caregivers are possible prevention of hospitalization due to better home-care management, early identification of symptoms or adverse events, and prompt medical attention for either.

4.3 |. Conclusion

Among multimorbid older adults with dementia, the presence of ischemic heart disease and chronic kidney disease were associated with increased annual hospitalizations, hospital costs, and direct medical costs. These findings highlight patient populations with specific chronic diseases that might be targeted by ambulatory care for closer monitoring, proactive management, or caregiver training. Proactive and ambulatory care that includes informal caregivers along with primary and specialty providers may offer promise to decrease use and costs for chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, depression, and hypertension.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

1. Systematic review:

The authors reviewed the literature using PubMed for articles and cross-referencing citations, identifying reports from governmental and non-governmental organizations, and interacting with medical professionals to support our aims. A recent systematic review based on a call for action to understand the effect of cognitive impairment on disease management identified gaps in the literature evaluating dementia and other chronic conditions.

2. Interpretation:

Our findings are supported by peer-reviewed publications in the public domain that specific symptomatic chronic conditions, which may be ambulatory and home-care sensitive, are associated with increased hospitalization and costs. We extend these findings in a nationally representative cohort of multimorbid persons with dementia using longitudinal survey methodology.

3. Future directions:

The manuscript proposed proactive and ambulatory care that includes informal caregivers along with primary and specialty providers, may offer promise to decrease use and costs for chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, depression, and hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging grant (R01 AG047891–01A1, P50AG047270 and P30AG021342–16S1 [H.G.A and J.L.M.V.], and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30AG021342). This work was additionally supported by a James Hudson Brown-Alexander Brown Coxe fellowship (J.L.M.V.). The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Funding sources were not involved in the creation of this work.

We acknowledge with much gratitude the following people for their invaluable help: Brent Vander Wyk for his data management expertise and Steven Heeringa for his advice on the survey weights. Publicly available data were obtained from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS).

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: R01 AG047891–01A1, P50AG047270, P30AG021342–16S1; James Hudson Brown-Alexander Brown Coxe fellowship

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hill JW, Futterman R, Duttagupta S, Mastey V, Lloyd JR, Fillit H. Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias increase costs of comorbidities in managed Medicare. Neurology 2002;58:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bynum JP, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snowden MB, Steinman LE, Bryant LL, et al. Dementia and co-occurring chronic conditions: a systematic literature review to identify what is known and where are the gaps in the evidence? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;32:357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerritsen AA, Bakker C, Verhey FR, de Vugt ME, Melis RJ, Koopmans RT. Prevalence of comorbidity in patients with young-onset Alzheimer disease compared with late-onset: a comparative cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, Marin D, Neumann PJ. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M173–M177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N EnglJ Med 2013;369:489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries Baltimore, MD;2012:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donze J, Lipsitz S, Bates DW, Schnipper JL. Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2013;347:f7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso-Moran E, Nuno-Solinis R, Onder G, Tonnara G. Multimorbidity in risk stratification tools to predict negative outcomes in adult population. Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA 2010;304:1919–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA 2004;292:2115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine S, Steinman BA, Attaway K, Jung T, Enguidanos S. Home care program for patients at high risk of hospitalization. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:e269–e276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang NJ, Wan TT, Rossiter LF, Murawski MM, Patel UB. Evaluation of chronic disease management on outcomes and cost of care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Policy 2008;86:345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sommers LS, Marton KI, Barbaccia JC, Randolph J. Physician, nurse, and social worker collaboration in primary care for chronically ill seniors. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2195–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littleford A, Kralik D.Making a difference through integrated community care for older people. J Nurs Health Chronic Ill 2010;2:178–186. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA 2012;307:165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzheimer’s Association (AA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013–2018 Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasper JD, Freedman VA.Findings from the 1st round of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS): introduction to a special issue. J GerontolB Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69(Suppl 1):S1–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope GC, Ellis RP, Ash AS, et al. Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category Models for Medicare Risk Adjustment Health Economics Research, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare data file descriptions; 2014.

- 24.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions-A Strategic Framework: Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions Washington, DC;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warshaw G Introduction: advances and challenges in care of older people with chronic illness. Generations 2006;30:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Chronic Conditions data warehouse: Condition Categories; 2019.

- 27.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and Care Needs of Older Americans by Dementia Status: An Analysis of the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Department of Labour. Minimum Wage

- 29.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman B, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. NHATS Technical Paper #2 Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heeringa S, BT W, BA B. Applied Survey Analysis 2nd ed.Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valliant R, Dever JA, Kreuter F. Practical Tools for Designing and Weighting Survey Samples New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wun LM, Ezzati-Rice TM, Diaz-Tena N, Greenblatt J. On modelling response propensity for dwelling unit (DU) level non-response adjustment in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Stat Med 2007;26:1875–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post JB, Jegede AB, Morin K, Spungen AM, Langhoff E, Sano M. Cognitive profile of chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients without dementia. Nephron Clin Pract 2010;116:c247–c255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elias MF, Elias PK, Seliger SL, Narsipur SS, Dore GA, Robbins MA. Chronic kidney disease, creatinine and cognitive functioning. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:2446–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madan P, Kalra OP, Agarwal S, Tandon OP. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;22:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurella M, Mapes DL, Port FK, Chertow GM. Correlates and outcomes of dementia among dialysis patients: the dialysis outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:2543–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian Q, Nasr SH.Diagnosis and treatment of glomerular diseases in elderly patients. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014;21:228–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molnar MZ, Sumida K, Gaipov A, et al. Pre-ESRD dementia and Post-ESRD mortality in a large cohort of incident dialysis patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2017;43:281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halling A, Berglund J.Association of diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus and heart failure with cognitive function in the elderly population. Eur J Gen Pract 2006;12:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Justin BN, Turek M, Hakim AM. Heart disease as a risk factor for dementia. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pellegrino LD, Peters ME, Lyketsos CG, Marano C. Depression in cognitive impairment. Current psychiatry reports 2013;15(9):1–8. 10.1007/s11920-013-0384-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hapca S, Guthrie B, Cvoro V, et al. Mortality in people with dementia, delirium, and unspecified cognitive impairment in the general hospital: prospective cohort study of 6,724 patients with 2 years follow-up. Clin Epidemiol 2018;10:1743–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dodson JA, Truong T-TN, Towle VR, Kerins G, Chaudhry SI. Cognitive impairment in older adults with heart failure: prevalence, documentation, and impact on outcomes. Am J Med 2013;126:120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuo TC, Zhao Y, Weir S, Kramer MS, Ash AS. Implications of comorbidity on costs for patients with Alzheimer disease. Med Care 2008;46:839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freedman Vicki A., Spillman Brenda C., Kasper J. Hours of Care in Rounds 1 and 2 of the National Health and Aging Trends Study. NHATS Technical Paper #7 Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2001;56:S219–S228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:770–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor DH Jr., Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis 2009;17:807–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galvin JE, Valois L, Zweig Y. Collaborative transdisciplinary team approach for dementia care. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2014;4:455–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff JL, Spillman B.Older adults receiving assistance with physician visits and prescribed medications and their family caregivers: prevalence, characteristics, and hours of care. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69(Suppl 1):S65–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.AARP Public Policy Institute, National Alliance for Caregiving. 2015. Research Report: Caregiving in the U.S: AARP Public Policy Institute and the NAC; 2015:1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America Washington, DC: National Academies Press;2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]