Abstract

Background

Team‐based models of cardio‐obstetrics care have been developed to address the increasing rate of maternal mortality from cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovascular clinician and trainee knowledge and comfort with this topic, and the extent of implementation of an interdisciplinary approach to cardio‐obstetrics, are unknown.

Methods and Results

We aimed to assess the current state of cardio‐obstetrics knowledge, practices, and services provided by US cardiovascular clinicians and trainees. A survey developed in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology was circulated to a representative sample of cardiologists (N=311), cardiovascular team members (N=51), and fellows in training (N=139) from June 18, 2020, to July 29, 2020. Knowledge and attitudes about the provision of cardiovascular care to pregnant patients and the prevalence and composition of cardio‐obstetrics teams were assessed. The widest knowledge gaps on the care of pregnant compared with nonpregnant patients were reported for medication safety (42%), acute coronary syndromes (39%), aortopathies (40%), and valvular heart disease (30%). Most respondents (76%) lack access to a dedicated cardio‐obstetrics team, and only 29% of practicing cardiologists received cardio‐obstetrics didactics during training. One third of fellows in training reported seeing pregnant women 0 to 1 time per year, and 12% of fellows in training report formal training in cardio‐obstetrics.

Conclusions

Formalized training in cardio‐obstetrics is uncommon, and limited access to multidisciplinary cardio‐obstetrics teams and large knowledge gaps exist among cardiovascular clinicians. Augmentation of cardio‐obstetrics education across career stages is needed to reduce these deficits. These survey results are an initial step toward developing a standard expectation for clinicians’ training in cardio‐obstetrics.

Keywords: cardio‐obstetrics, continuing medical education, medical knowledge, pregnancy

Subject Categories: Quality and Outcomes

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVT

cardiovascular team

- FIT

fellow in training

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The growing burden of cardiovascular disease in adults, who are trying to become and who are pregnant, places them at risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Cardio‐obstetrics knowledge and practice patterns of the cardiovascular workforce and fellows in training have not yet been described.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Cardiovascular clinicians receive little formal training and report large knowledge gaps in cardio‐obstetrics.

Along with the standardization and amplification of cardio‐obstetrics team‐based care, the survey results highlight the need to increase available educational opportunities for practicing clinicians and trainees.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is not only the leading cause of death in the United States, but also the primary cause of pregnancy‐related mortality. 1 , 2 Approximately two thirds of all maternal deaths are from CVD, and most of these are preventable. 1 , 3 Among industrialized countries, the United States has the highest rate of maternal mortality, and this alarming trend has continued to increase since the early 2000s. 4 The urgent need for efforts to reduce maternal mortality has recently been highlighted by the US Surgeon General and the Department of Health and Human Services. 5 , 6

The care of pregnant women with or at risk for CVD covers a wide clinical spectrum, including preconception counseling, management of CVD during pregnancy and postpartum, and counseling and preventative care for women with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes who are at heightened risk for subsequent CVD. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 To address the complexities of providing care to these pregnant women, comprehensive cardio‐obstetrics team‐based approaches have been developed at several centers. 15 , 16 , 17 Despite the field’s existence for several decades and a growing evidence base to guide the care of patients, 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 16 the current state of cardio‐obstetrics knowledge and practices of cardiologists, fellows in training (FITs), and cardiovascular team (CVT) members, as well as the prevalence and composition of formal cardio‐obstetrics programs, is unknown. To answer these questions, we performed a cross‐sectional survey with a deliberate sampling design to provide results that are representative of the US membership of the American College of Cardiology (ACC).

METHODS

Study Sample

This was a cross‐sectional electronic survey sent via e‐mail to a targeted, representative group of 5091 US ACC member clinicians, including adult and pediatric cardiologists, FITs, and CVT members (nurse practitioners, pharmacists, physician assistants, and registered nurses). The survey was conducted from June 18, 2020, to July 29, 2020, and a maximum of 3 reminders were sent. The surveyed clinicians were sampled through a random stratified sampling technique to be representative of the range of clinical settings, subspecialties, career stage, and geography encountered across the United States. This study was approved by the ACC institutional review board, and a waiver of written informed consent was granted. The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article (and its online supplementary files).

Survey Design

Survey questions were developed and refined through an iterative process involving experts in cardio‐obstetrics with oversight from an ACC staff member with expertise in survey design and implementation. The final instrument included 24 items, covering the following topics: care of pregnant/postpartum women; personal competency in managing heart disease in pregnant and nonpregnant patients; presence and composition at the respondent’s institution of a dedicated cardio‐obstetrics team; prior training/education in cardio‐obstetrics; and desired educational needs and resources. There were slight modifications of survey questions administered to practicing clinicians (physicians and CVT members) and trainees (FITs); the full surveys are available in Data S1.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0; Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

A total of 311 cardiologists, 139 FITs, and 51 CVT members completed the survey, for a response rate of 10%. The Table describes the demographics and characteristics of the respondents. The minority of cardiologists (26%) and FITs (37%) identify as women, compared with 84% of CVT members, and most of the respondents in all 3 groups were White race (50%–77%). Table S1 illustrates the representative nature of respondents compared with the overall ACC membership at the time of survey distribution.

Table 1.

Demographics and Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Variable | Cardiologists (N=311) | CVT members (N=51) | FITs (N=139) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 26 | 84 | 37 | |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||

| White | 58 | 77 | 50 | |

| Asian | 25 | 10 | 31 | |

| Black | 4 | 2 | 7 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Other/decline | 8 | 6 | 7 | |

| Practice characteristics | Trainee characteristics | |||

| Time in practice, y | Year of training | |||

| ≤7 | 21 | 49 | First‐year clinical fellow | 25 |

| 8–14 | 17 | 18 | Second‐year clinical fellow | 30 |

| 15–21 | 19 | 16 | Third‐year clinical fellow | 33 |

| ≥22 | 42 | 18 | First‐year research fellow | 3 |

| Other | 9 | |||

| Practice setting | No. of fellows in program | |||

| Cardiovascular group practice | 49 | 47 | 1–10 | 25 |

| Medical school | 25 | 10 | 11–20 | 32 |

| Government hospital | 6 | 4 | 21–30 | 26 |

| Nongovernmental hospital | 7 | 24 | 31–40 | 11 |

| Multispecialty group | 7 | 8 | 41–50 | 4 |

| Solo practice | 5 | 0 | >50 | 2 |

| Insurance company/other | 1 | 6 | Planned area of specialization | |

| Region | Adult cardiology | 29 | ||

| South | 41 | 41 | Invasive/interventional | 29 |

| Northeast | 24 | 28 | Electrophysiology | 13 |

| Midwest | 20 | 18 | Heart failure | 9 |

| West | 14 | 14 | Imaging | 9 |

| Board certification | Other | 5 | ||

| Adult cardiology | 91 | NA | Adult congenital | 3 |

| Interventional cardiology | 25 | NA | Undecided | 2 |

| Electrophysiology | 9 | NA | Critical care | 1 |

| Pediatric cardiology | 6 | NA | ||

| Heart failure/transplant | 6 | NA | ||

| Adult congenital | 4 | NA | ||

| Nuclear medicine | 3 | NA | ||

| Surgery | <1 | NA | ||

Data are given as percentage of respondents. CVT indicates cardiovascular team; FIT, fellow in training; and NA, not applicable.

Other includes individuals who self identify as Native American/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, or Other.

Care of Pregnant and Postpartum Women

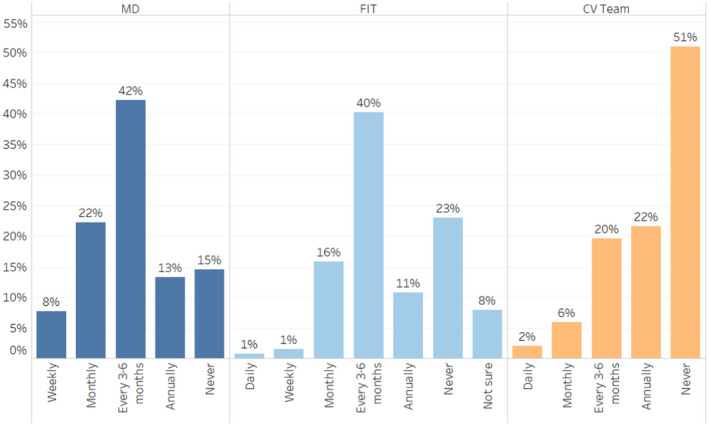

In 64% of institutions, the acute care of pregnant and recently postpartum women is staffed by the on‐call consulting cardiologist, whereas in 29% it is by a select group of individuals, with most of these institutions having 1 to 2 cardiologists with a special focus in cardio‐obstetrics. Fewer than one third of clinicians reported that they evaluate a pregnant or lactating patient at least monthly. Most cardiologists (42%) and FITs (40%) see such patients only every 3 to 6 months, whereas 51% of CVT members are never involved in the care of a pregnant or postpartum woman (Figure 1). One third of FITs reported evaluating a pregnant woman 0 to 1 time per year. In rank order, the 5 most common reasons for consultation across all respondents were as follows: (1) hypertension, (2) arrhythmia history/management, (3) valvular heart disease, (4) heart failure, and (5) preeclampsia. Less common indications included simple and complex congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease, and connective tissue disorders.

Figure 1. Reported frequency of evaluation of a pregnant or lactating patient by survey group.

Reported frequency of evaluation of a pregnant or lactating patient for the 3 surveyed groups: cardiologists (MDs), fellows in training (FITs), cardiovascular team (CV Team) members.

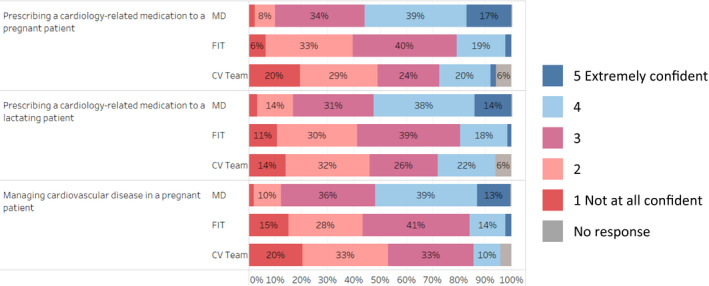

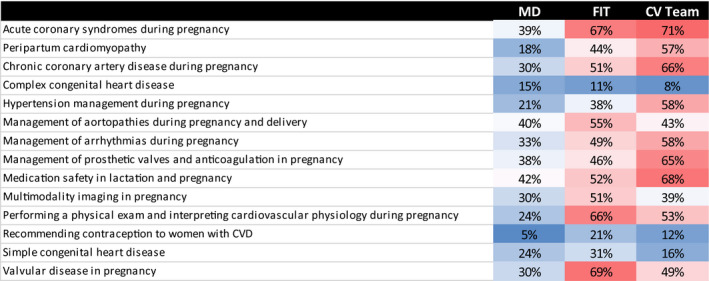

Slightly more than half of cardiologists are very or extremely confident prescribing a cardiovascular medication to a pregnant (56%) or lactating patient (52%) and managing CVD in pregnancy (52%). FITs and CVT members are much less confident in these general areas (Figure 2). We further queried for clinicians’ comfort level managing a variety of cardiovascular conditions in pregnant and nonpregnant patients, and for each topic, a gap in comfort level was calculated as the difference between the level of comfort caring for a pregnant versus a nonpregnant patient with the same condition (Figure 3 and Figures S1 and S2). Compared with FITs and CVT members, cardiologists reported higher confidence levels for treating all cardiovascular conditions and the lowest gaps in comfort between treating pregnant and nonpregnant patients with the same condition. Cardiologists reported the lowest levels of confidence recommending contraception to women with CVD and treating complex congenital heart disease in both pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Similar trends were seen for FITs and CVT members.

Figure 2. Self‐reported confidence in treating pregnant or lactating patients by survey group.

Self‐reported confidence in treating pregnant or lactating patients for the 3 surveyed groups: cardiologists (MDs), fellows in training (FIT), cardiovascular team (CV Team) members.

Figure 3. Gaps in comfort level for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in pregnant vs nonpregnant adults.

Larger gap percentage indicates greater level of discomfort treating pregnant patients compared with nonpregnant patients with a similar condition. CV Team indicates cardiovascular team; FIT, fellow in training; and MD, physician MD.

Existing Cardio‐Obstetrics Teams

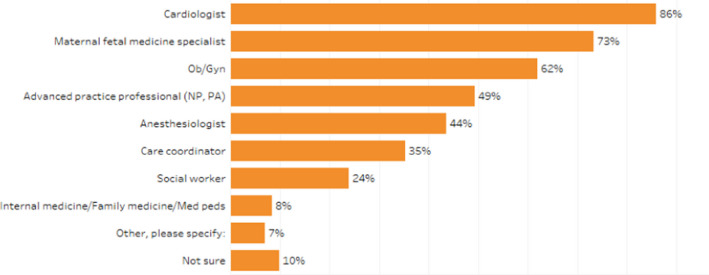

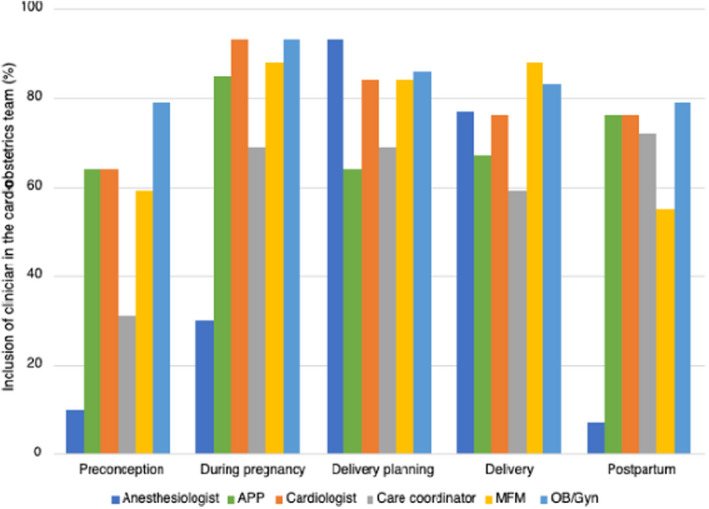

Most cardiology physician (76%) and CVT member (63%) practices do not have a dedicated cardio‐obstetrics team. Consistent with this finding, only 10% of cardiologists and 2% of CVT member respondents are a part of the cardio‐obstetrics team in their practice setting. Of the 71 respondents with knowledge of a cardio‐obstetrics team at their facility, 54% practice at a medical school, 37% are part of a cardiovascular or multispecialty group, 6% are at a nongovernment and 3% at a government hospital, and only 1% are in solo practice. The composition of these teams is shown in Figure 4. For the timing of their involvement in the cardio‐obstetrics team, more than half of cardiologists (64%) are involved in prepregnancy/preconception, with a greater percentage involved during pregnancy (93%), delivery planning (84%), and similar level of involvement during delivery hospitalization and postdischarge (76%) (Figure 5). Before conception, obstetricians (79%), cardiologists (64%), and advanced practice professionals (64%), followed by maternal fetal medicine specialists (59%), are the most frequently included members of the cardio‐obstetrics team. During pregnancy, 93% of cardio‐obstetrics teams contain a cardiologist and an obstetrician, 88% also involve a maternal fetal medicine specialist, and most include a social worker (75%) and/or care coordinator (65%). Anesthesiologists are predominantly involved in delivery planning (93%) and during the delivery hospitalization (77%). After discharge, most cardio‐obstetrics teams are composed of obstetricians (79%), advanced practice professionals (76%), cardiologists (76%), social workers (75%), and care coordinators (70%).

Figure 4. Composition of the cardio‐obstetrics teams.

Composition of the cardio‐obstetrics teams reported by respondents whose institutions/practices have a cardio‐obstetrics team. NP indicates nurse practitioner; OB/Gyn, obstetrician gynecologist; and PA, physician assistant.

Figure 5. Composition of cardio‐obstetrics teams as reported across the span of pregnancy from preconception through the postpartum period, by clinician type.

APP indicates advanced practice professional; MFM, maternal fetal medicine specialist; and OB/Gyn, obstetrician gynecologist.

Past and Present Training in Cardio‐Obstetrics

Of the practicing clinicians surveyed, 66% of cardiologists and 94% of CVT members received no formal cardio‐obstetrics didactics during their training. For the 29% of cardiologists who reported some formalized training, 85% have been in practice <14 years and only 13% believed their clinical exposure to pregnant women with CVD while training was adequate. Current FITs also report limited training and didactic experience in cardio‐obstetrics. Slightly more than half of FITs (55%) had attended a lecture/conference on cardio‐obstetrics in the past year, with 86% of that group reporting 1 to 5 hours and 9% reporting 6 to 10 hours over the course of a year dedicated to cardio‐obstetrics didactic learning. Of the FIT responders, more than three quarters (83%) report they do not have a cardio‐obstetrics training module in their training program. The 12% (n=16) of FITs who do have formal training tend to be at larger‐sized programs (≥20 fellows), and of the programs with a formal module, only 13% require participation in the rotation.

The vast majority, 92% of respondents, thought positively about the inclusion of cardio‐obstetrics in the ACC repertoire of educational products. Midcareer cardiologists and CVT members were most likely to believe this is an extremely important offering. Almost half (46%) of FITs believe it is important for training in cardio‐obstetrics to be included in the Core Cardiovascular Training Statement requirements.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this survey suggest that although 30% of cardiologists evaluate a pregnant patient at least monthly and 86% at least annually, a large proportion of the cardiology workforce feels uncomfortable providing care to these patients. Key findings include the following: (1) most respondents (76%) lack access to a dedicated cardio‐obstetrics team; (2) only 29% of practicing cardiologists received cardio‐obstetrics didactics during training; and (3) 83% of current FITs report no formal cardio‐obstetrics training in their fellowship program. The results also highlight a large self‐perceived deficit in the clinical knowledge and competency base for both cardiovascular clinicians in practice and those in training across the spectrum of cardio‐obstetrics topics. This shortfall is seen in conjunction with reports of limited formal training in cardio‐obstetrics by physicians in practice and training as well as CVT members. Our study is the first to assess and highlight the challenges in the cardio‐obstetrics knowledge base and the competencies of a diverse cardiovascular workforce. Although the team‐based field of cardio‐obstetrics has developed to provide specialized care to women with and at risk for CVD in pregnancy, most practices and thus patients do not have access to such a team. When present, there is marked variability in the cardio‐obstetrics teams’ makeup and involvement of team members at different time points from preconception through delivery and postdischarge. These inconsistencies are particularly important given the recommendations for preconception counseling for women with underlying CVD and the growing recognition that the postpartum period is a high‐risk time for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. 10 , 11 , 12 , 18

Practicing Cardiologists

For all topic areas investigated, practicing cardiologists reported the highest level of comfort managing both nonpregnant and pregnant patients, and with the exception of congenital heart disease, cardiologists also reported the smallest gap in comfort level between treating a pregnant and nonpregnant patient with the same condition. Although 56% of practicing cardiologists reported they were very or extremely confident in prescribing a medication to pregnant women, the largest gaps in cardiologists’ comfort level caring for pregnant compared with nonpregnant patients pertain to medication safety in pregnancy and lactation, followed by the management of aortopathies and acute coronary syndromes during pregnancy and delivery. The gap in comfort level was smallest for the provision of contraception, which arose from a global low level of confidence with the topic for all women with CVD, rather than a high level of comfort recommending contraception to women with CVD who are pregnant or postpartum.

CVT Members

In general, CVT members reported similar patterns of self‐perceived strengths and weaknesses by topic area as practicing cardiologists, but with a higher relative gap in comfort for any given topic. CVT members have the potential to make important contributions to the cardio‐obstetrics care team, particularly during the fourth trimester when cardiovascular complications are common and long‐term risk modification and counseling is essential. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 19 , 20 Future opportunities for the use of CVT members as part of the cardio‐obstetrics team include telehealth and remote vital sign monitoring. With proven efficacy, validity, and improved patient satisfaction, CVT telehealth visits and remote monitoring lead to increased compliance with recommendations and follow‐up for all demographics of women. 21 , 22 , 23

Fellows in Training

Similar to CVT members, most FITs do not feel comfortable treating pregnant/lactating patients. One of the largest gaps was seen in valvular heart disease for FITs, with 88% feeling extremely/somewhat comfortable managing this condition in the nonpregnant patient, whereas only 19% felt the same in pregnant patients, a gap of 69%. A total of 90% of FITs felt extremely/somewhat comfortable managing hypertension in the nonpregnant patient, whereas only 52% felt the same in pregnant patients, even though hypertension is the most common cardiac condition for consultation. These findings are particularly relevant given that left‐sided valvular stenosis is one of the highest‐risk cardiovascular conditions in pregnancy, and the prevalence of hypertensive disorders is increasing among pregnant women and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. 2 , 24 , 25 , 26 Furthermore, only 2% of FITs felt extremely confident in prescribing a cardiovascular medication to a pregnant or lactating patient, an essential skill for prompt and effective treatment of cardiovascular disorders in pregnant and lactating women.

Opportunities for Educational Initiatives

Along with standardization and amplification of cardio‐obstetrics team‐based care, the survey results highlight a large need to increase the available educational opportunities for practicing clinicians and FITs. Maternal mortality reviews have identified that issues related to clinical care, including a failure to promptly diagnose and deliver effective treatment, are often the largest contributors to maternal cardiovascular deaths. 1 Increased broad knowledge of cardio‐obstetrics topics within the specialty of cardiology in addition to the education of other groups of clinicians, such as those providing emergency medicine and primary care who are often the first to evaluate these women, are needed. The survey responses indicate that these educational efforts would be well received.

These findings clearly demonstrate multiple gaps in current (and prior) training standards, offering potential opportunities for growth for cardiovascular FITs. 18 , 27 In addition to enhancing and expanding their didactic curriculum, trainees could benefit from increased exposure to this patient population. Current self‐reported exposure of FITs to pregnant or lactating women is low, with 11% evaluating a pregnant or lactating patient annually and 23% never over the course of their fellowship to date. This historical and ongoing shortfall likely contributes to the gaps reported by practicing clinicians as well as FITs; there is clearly a higher level of comfort for managing heart disease in the nonpregnant patient compared with the pregnant patient for all groups. Ensuring exposure to this complex patient population and adequate interdisciplinary didactic training for all cardiovascular trainees will be important for reducing knowledge gaps and improving maternal outcomes.

Similar opportunities exist to improve upon current CVT member training. Current nurse practitioner/physician assistant programs are mostly divided by Family Practice (which encompasses obstetrics and postpartum care) and Acute Care Practice (cardiovascular specialties), creating few chances during graduate‐level education to marry the 2 topics, but innovative combination programs at cardio‐obstetrics centers of excellence could be developed. For practicing CVT clinicians (nurse practitioners/physician assistants/registered nurses), training varies greatly based on the clinical setting; and although a Practice Transition Accreditation Program pathway currently does not exist, one could be constructed to merge the currently isolated obstetrics and cardiology curricula into dedicated cardio‐obstetrics training.

Although the field of cardio‐obstetrics has existed for several decades, survey respondents report a paucity of formalized programs at their institutions, with most existing in affiliation with a medical school. Although data supporting a maternal morbidity and mortality benefit for women with CVD who are cared for by a cardio‐obstetrics team are limited, they suggest better outcomes for patients cared for by an integrated, multidisciplinary program compared with national data for the usual care. 15 Although the general care of pregnant and postpartum women is an essential skillset, it is unnecessary for every practice setting to have a dedicated cardio‐obstetrics team. Referral‐based access to an expert collaborative cardio‐obstetrics team should be available for all women when needed, following the model used for patients with complex congenital heart disease. To match the current and projected population of cardio‐obstetrics patients, the cardio‐obstetrics team model must also expand in a way that is proven to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. Cardio‐obstetrics core competencies and best practices must be developed to monitor outcomes and track programs’ effectiveness. 18 This survey’s documentation of the variability in cardio‐obstetrics teams represents an important first step forward, but more work is needed to develop and test models of care that provide benefit and can be easily replicated and expand knowledge around best practices.

There are some limitations of our findings that should be noted. The survey instruments used for this undertaking have not been validated. Although only 10% of the approached individuals completed the survey, the survey was specifically designed to be nationally representative and reflective of the ACC’s member base. Unfortunately, data on nonrespondents’ cardio‐obstetrics knowledge and training are not available for comparison with responders, although we hypothesize that individuals who completed the survey may have been more confident or interested in the subject, thus potentially skewing the results to be biased toward overestimating exposure and training in cardio‐obstetrics.

Despite the increasing wave of cardiovascular maternal morbidity and mortality, there is a significant gap in knowledge and confidence among cardiovascular clinicians and trainees pertaining to the care of pregnant and postpartum women with CVD. Although all surveyed groups recognize cardio‐obstetrics as a vital area of our field and are interested in education on the topic, most cardiologists, FITs, and CVT members do not feel confident managing CVD in pregnant or lactating women. Few centers currently have formalized multidisciplinary cardio‐obstetrics teams, and training for cardiovascular fellows is inadequate, providing us with a legacy of suboptimally trained clinicians. This survey substantiates the need for developing new standards for training and educating members of the cardiology workforce to optimize the care provided to pregnant and lactating women with CVD, and to facilitate the expansion of dedicated cardio‐obstetrics centers. 16 These efforts will improve the care we provide to women with CVD who are planning or experiencing pregnancy and help reverse the alarming increase in rates of maternal morbidity and mortality experienced in this country.

Sources of Funding

Dr Bello receives funding from National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: K23 HL136853 and R01HL153382.

Disclosures

Dr Park receives grant funding from Abbott. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1

Table S1

Figures S1–S2

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Rzeszut from the American College of Cardiology for her assistance with survey design, implementation, and analysis.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.024229

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

Contributor Information

Natalie A. Bello, Email: natalieann.bello@cshs.org.

Ki Park, Email: ki.park@medicine.ufl.edu.

References

- 1. D'Oria R, Downs K, Trierweiler K. Report from maternal mortality review committees: a view into their critical role. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/files/upload/pdf/MMRIAReport.pdf. Accessed 9/5/2020, 2020.

- 2. Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Mayes N, Johnston E, Syverson C, Seed K, Shapiro‐Mendoza CK, Callaghan WM, et al. Vital signs: pregnancy‐related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy‐related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366–373. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Trends in pregnancy‐related mortality in the United States: 1987–2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal‐mortality/pregnancy‐mortality‐surveillance‐system.htm#trends. Accessed September 5, 2020.

- 5. Office of the Surgeon General (OSG) . The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health [Internet]. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/call‐to‐action‐maternal‐health.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy women, healthy pregnancies, healthy futures: action plan to improve maternal health in America. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/aspe‐files/264076/healthy‐women‐healthy‐pregnancies‐healthy‐future‐action‐plan_0.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 7. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella‐Tommasino J, Forman DE, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd‐Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e563–e595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis MB, Walsh MN. Cardio‐obstetrics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005417. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis MB, Arendt K, Bello NA, Brown H, Briller J, Epps K, Hollier L, Langen E, Park K, Walsh MN, et al. Team‐based care of women with cardiovascular disease from pre‐conception through pregnancy and postpartum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1763–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindley KJ, Merz CNB, Asgar AW, Bello NA, Chandra S, Davis MB, Gomberg‐Maitland M, Gulati M, Hollier LM, Krieger EV, et al. Management of women with congenital or inherited cardiovascular disease from pre‐conception through pregnancy and postpartum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1778–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park K, Merz CNB, Bello NA, Davis M, Duvernoy C, Elgendy IY, Ferdinand KC, Hameed A, Itchhaporia D, Minissian MB, et al. Management of women with acquired cardiovascular disease from pre‐conception through pregnancy and postpartum. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1799–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bello NA, Bairey Merz CN, Brown H, Davis MB, Dickert NW, El Hajj SC, Giullian C, Quesada O, Park KI, Sanghani RM, et al. Diagnostic cardiovascular imaging and therapeutic strategies in pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1813–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindley KJ, Merz CNB, Davis MB, Madden T, Park K, Bello NA. Contraception and reproductive planning for women with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1823–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magun E, DeFilippis EM, Noble S, LaSala A, Waksmonski C, D'Alton ME, Haythe J. Cardiovascular care for pregnant women with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2102–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daming TNB, Florio KL, Schmidt LM, Grodzinsky A, Nelson LA, Swearingen KC, White DL, Patel NB, Gray RA, Rader VJ et al. Creating a maternal cardiac center of excellence: a call to action. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;34(24):4153–4158. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1706474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strickland RA, Oliver WC Jr, Chantigian RC, Ney JA, Danielson GK. Anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, and the pregnant patient. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:411–429. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60666-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehta LS, Warnes CA, Bradley E, Burton T, Economy K, Mehran R, Safdar B, Sharma G, Wood M, Valente AM. et al. Cardiovascular considerations in caring for pregnant patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e884–e903. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharma G, Zakaria S, Michos ED, Bhatt AB, Lundberg GP, Florio KL, Vaught AJ, Ouyang P, Mehta L. Improving cardiovascular workforce competencies in cardio‐obstetrics: current challenges and future directions. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015569. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith GN, Louis JM, Saade GR. Pregnancy and the postpartum period as an opportunity for cardiovascular risk identification and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:851–862. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ACOG committee opinion no. 736 summary: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:949–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoppe KK, Williams M, Thomas N, Zella JB, Drewry A, Kim K, Havighurst T, Johnson HM. Telehealth with remote blood pressure monitoring for postpartum hypertension: a prospective single‐cohort feasibility study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;15:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hauspurg A, Lemon LS, Quinn BA, Binstock A, Larkin J, Beigi RH, Watson AR, Simhan HN. A postpartum remote hypertension monitoring protocol implemented at the hospital level. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:685–691. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalafat E, Benlioglu C, Thilaganathan B, Khalil A. Home blood pressure monitoring in the antenatal and postpartum period: a systematic review meta‐analysis. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;19:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Roos‐Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomstrom‐Lundqvist C, Cifkova R, De Bonis M, Iung B, Johnson MR, Kintscher U, Kranke P, et al.; Group ESCSD . 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165–3241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drenthen W, Boersma E, Balci A, Moons P, Roos‐Hesselink JW, Mulder BJ, Vliegen HW, van Dijk AP, Voors AA, Yap SC, et al. Predictors of pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2124–2132. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cameron Natalie A, Molsberry R, Pierce Jacob B, Perak Amanda M, Grobman William A, Allen Norrina B, Greenland P, Lloyd‐Jones Donald M, Khan SS. Pre‐pregnancy hypertension among women in rural and urban areas of the united states. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2611–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sharma G, Lindley K, Grodzinsky A. Cardio‐obstetrics: developing a niche in maternal cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1355–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Table S1

Figures S1–S2