Abstract

Family engagement empowers family members to become active partners in care delivery. Family members increasingly expect and wish to participate in care and be involved in the decision‐making process. The goal of engaging families in care is to improve the care experience to achieve better outcomes for both patients and family members. There is emerging evidence that engaging family members in care improves person‐ and family‐important outcomes. Engaging families in adult cardiovascular care involves a paradigm shift in the current organization and delivery of both acute and chronic cardiac care. Many cardiovascular health care professionals have limited awareness of the role and potential benefits of family engagement in care. Additionally, many fail to identify opportunities to engage family members. There is currently little guidance on family engagement in any aspect of cardiovascular care. The objective of this statement is to inform health care professionals and stakeholders about the importance of family engagement in cardiovascular care. This scientific statement will describe the rationale for engaging families in adult cardiovascular care, outline opportunities and challenges, highlight knowledge gaps, and provide suggestions to cardiovascular clinicians on how to integrate family members into the health care team.

Keywords: AHA Scientific Statements, cardiovascular, family engagement, patient– and family–centered care

Subject Categories: Statements and Guidelines

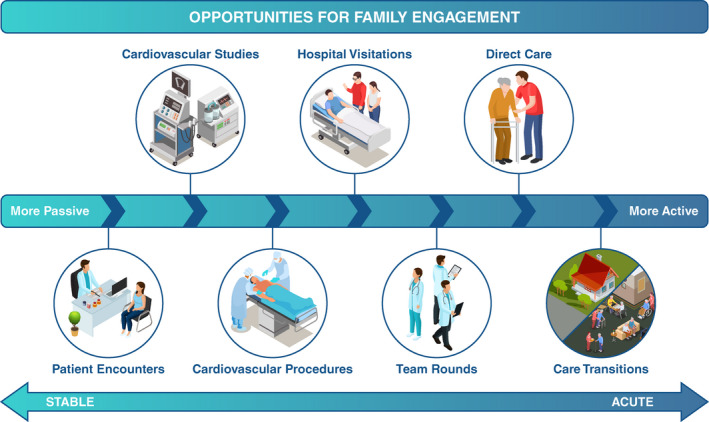

Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally, with more than 18.6 million deaths in 2019, and it is estimated that nearly half of adults in the United States have some type of cardiovascular disease. 1 Many individuals living with cardiovascular disease have an illness trajectory that can span over years, including multiple transitions in care. These transitions encompass outpatient management, home care, acute hospitalizations, and end of life care during times of medical stability as well as acute exacerbations (Figure 1). As the individual living with cardiovascular disease traverses the illness trajectory, so do their family members.

Figure 1. Opportunities for family engagement in cardiovascular care.

There is a growing body of evidence on the significant impact that illness has on family members of people living with cardiovascular disease. Patient and family engagement in care is an approach to improve experiences and to achieve better outcomes for both the person living with an illness and their family members. Engagement is the active participation of patients, families, and health care professionals as essential and active partners in health care delivery. Family engagement is conceptualized as taking action with people as opposed to for people, in which patients, families, and health care professionals actively work together to support involvement of both parties in health care and decision making. 2 Family is defined as any person(s) whom the patient wants involved in their care. 3

Engaging families in care is a means to achieve family‐centered care. The concept of family‐centered care gained traction when the Society of Critical Care Medicine introduced the first guidelines in 2007. 4 Those guidelines were updated with the most current evidence in 2017 and provide recommendations for a family‐centered approach across all age groups in the intensive care setting. 5 Family‐centered care, as a framework to guide care, received national recognition in 2011 when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement released the white paper Achieving an Exceptional Patient and Family Experience of Inpatient Hospital Care. 6 These seminal papers were the impetus for a growing body of studies evaluating the benefits of family‐centered care and have expanded beyond the acute care setting.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the positive benefits of implementing family engagement in care, primarily in intensive care units, and there is a growing body of evidence on the role of families in care in cardiac settings. Evidence supports family engagement in care as a strategy to improve both the patient and family experience and outcomes. Interventions promoting family engagement in the intensive care setting have demonstrated increased satisfaction with care, improved medical goal achievement, and superior patient and family psychological recovery and well‐being. 7 , 8 , 9

In this scientific statement, the evidence pertaining to family engagement in cardiovascular care is synthesized to describe (1) a structural framework of family engagement, (2) family engagement in the acute and outpatient cardiac settings, (3) caring for the caregiver, (4) family engagement during times of crisis, (5) family engagement in special population groups, (6) the role of the family in the transition from pediatric to adult cardiovascular care, (7) knowledge gaps and future directions, and (8) suggestions for clinical practice.

STRUCTURAL FRAMEWORK

Principles of Family Engagement

There is a role for engaging families in patient care across all age groups. Among groups generally not considered autonomous decision makers, such as children or adults with significant cognitive impairment, there is a tacit societal acceptance for family to be more involved in care. However, some may consider family engagement optional or even unnecessary for adults with decision‐making capacity. 10 Yet many adults want family to participate in their care, and many family members wish to engage in the care process. The effort to include family in care must be balanced against the patient’s right to autonomy; some patients may not wish to have their family members engaged in their care or they may have desired limits on the degree of engagement. During an acute crisis, when a patient is unable to communicate, it may be difficult to evaluate the patient’s desires in their family engagement when there is no power of attorney in place. The health care professional should assess and support family engagement in suitable aspects of care to the extent of the patient’s wishes, if known or previously expressed.

Structural Framework

Various conceptualizations for family engagement in care exist. One practical framework involves categorizing care engagement along a continuum of involvement from most passive to most active (Figure 1). 11 The most passive involvement includes allowing family presence during patient encounters, cardiac investigations, procedures, and health care team discussions. More active involvement includes communication between the family and the care team, meeting the care needs of the family member, and acting as a surrogate decision maker or as part of the shared decision‐making process. The most active involvement involves direct care contribution by the family member, such as provision of basic care needs (ie, feeding and hygiene), assisting with mobilization, fall prevention, detecting delirium, administering medications, bringing patients to appointments, and monitoring vital signs.

Scope of Family Engagement

Beyond participating in the care of their relative, family members have much to offer as partners in care at multiple organizational levels. At the institutional level, family members can participate in administrative groups to ensure that organizational policies reflect core principles of family engagement and to support engagement initiatives. Family members can also partner with key stakeholders to advocate for family engagement in health care delivery on a regional health system or a national scale. Family members may also actively participate in the design of research, education, and quality‐of‐care initiatives. Family member involvement in these endeavors should reflect a true partnership rather than mere tokenism. 12

Family Members Themselves May Benefit From Being Engaged in Care

There is emerging evidence that family members themselves benefit from being engaged in their relative’s care. Person‐ and family‐centered interventions have been shown to improve family satisfaction with care and family mental health outcomes, such as symptoms of depression and anxiety. 13 Family‐centered interventions may also improve cardiovascular risk factor management. 14 Thus, when circumstances prohibit the physical presence of family members during patient encounters, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic or socioeconomic stressors of the family member, clinicians should look for innovative approaches to engage family members. 15 Health care professionals should recognize that their care extends beyond the patient to the family and even to their larger community.

ACUTE CARDIAC CARE SETTING

Supporting a family member through an acute care admission is a stressful experience. Patients and families often feel helpless and experience a high level of anxiety during and after hospitalization. The goal of family engagement in acute cardiac care is to improve the care experience for both patients and family members and to decrease the residual trauma that can be associated with these hospitalizations (Supplemental Material).

Providing increased access to visitation by family members can reduce the social isolation patients often experience during acute care hospitalization. Liberal visitation policies, which can allow family members to visit for up to 24 hours per day, are associated with reduced anxiety and depression in family members compared with more restrictive visitation policies. 16 Importantly, increased visitation flexibility did not appear to increase infection rates or health care professional burnout, although this evidence comes from the pre–COVID‐19 era. 16 Family members may also benefit from being present during resuscitation efforts and invasive procedures. Offering family members the option to witness resuscitation efforts is associated with lower rates of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder–related symptoms in family members 1 year after the event without a deleterious impact on resuscitation characteristics, clinician stress, or patient survival. 17 Family members who were present during invasive procedures report feeling like they were active participants in care and provided comfort to their relatives. 18 The presence of family members during interdisciplinary team rounds has also been shown to improve communication, reduce rounding time, and improve health care professional satisfaction, while allowing adequate opportunity for teaching the house staff. 19 A pilot study of virtual rounding demonstrated the feasibility of using technology to engage family members during inpatient rounds. 20

Providing patients and family members with relevant written or online materials about the patient’s condition and upcoming tests can improve comprehension and family satisfaction. 21 There is a need to ensure adequate communication between family members and clinicians about decision making and care plans, particularly for vulnerable groups who are more likely to require family input. Phone and virtual meetings may be especially useful when in‐person visitation is limited or for family members who cannot be present. Electronic patient and family portals have also been used to improve the patient–family–clinician communication axis. 22

Many patients who are critically ill cannot advocate for themselves, and therefore family members are called upon to make medical decisions in their place. Acting as a surrogate decision maker can be difficult for distressed family members. Efforts to improve communication with surrogate decision makers include specialized training for physicians and allied health team members, informational leaflets, spiritual care support, and palliative care consultations where indicated. 23

Family members may wish to directly contribute to daily care of their loved ones. Direct care includes basic hygiene, feeding, assistance with mobilization, and delirium detection. The manner in which family members engage with the patient and care team may change throughout the acute illness trajectory. In addition, not all families wish to be engaged in care, and the expectation to do so may be more stressful. Successfully engaging families in acute cardiac care requires flexible and adaptable care teams who can tailor their approach to the patient and family’s comfort level.

Acute care hospitalization of a relative is also an opportune time to address family health. Family members are highly willing to be referred for cardiovascular risk factor screening at the time of their relative’s hospitalization for acute cardiovascular disease. 24 Interventions targeting family following a relative’s hospitalization have been shown to be effective at improving the cardiovascular risk factors and modifying health behaviors of family members. 14

OUTPATIENT CARE SETTING

The challenge of living with chronic cardiac disease in a stable state, with the goal of avoiding hospitalizations, is inextricably linked to reliance on the unpaid support from caregivers. 25 , 26 Caregivers can include the patient’s family, friends, religious group support members, or neighbors. Advances in the treatment of cardiovascular disease have improved survival, but this often means living longer with the consequences of the syndrome itself, which include, but are not limited to, symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue, arrhythmias, psychological consequences, and the financial consequences of chronic cardiovascular disease. 27 The specific tasks of the caregiver vary widely based on the individual’s needs, cultural background, and the age of the affected patient. 28

Most reports that have explored family engagement in patient care have been initiated with the given that the support has already been elicited and agreed upon. Few have explored how individuals became caregivers and what it took to obtain their approval and engagement. Common to most studies is that the caregiver requires and wishes to become an integral part of the care team obtaining communications in parallel to the patient to reduce ambiguity in the plans of care and the follow‐up needed. 29 , 30 Others have felt inadequately armed with knowledge of the waxing and waning of symptoms and their acceptance as part of the chronic cardiac condition. Most studies have focused on patients living with chronic heart failure (HF) syndromes, and there is a limit to the knowledge base of issues related to caregivers for other chronic cardiac conditions. 28 There is a need for studies exploring the role of caregivers in other cardiac conditions.

Thus, engaging caregivers in the longitudinal care of their family member's chronic cardiac conditions is a responsibility of the cardiac team; this can be achieved by including caregivers as part of the health care team and including them in all discussions about care protocols. To better understand the disease itself, cardiac care education should be tailored to the caregivers by using lay language or language commensurate to the caregivers’ experience and level of training. Caregiver preparedness and understanding of the family member's disease condition can be helpful in working through shared decision‐making options with long‐term implications and risks (eg, decision to implant a destination therapy left ventricular assist device). 27 , 29

CARING FOR THE CAREGIVER

There is increasing recognition that patients’ acute or chronic illnesses adversely affect the health of caregivers. 27 , 31 , 32 Among patients with cardiovascular disease, conditions such as HF are often accompanied by frequent hospitalizations, whereas others such as chronic ischemic heart disease may require multiple revascularization procedures. Beyond the burden of acute care, cardiovascular patients may experience chronic symptoms with daily activities such as fatigue, dyspnea, or angina. Furthermore, the majority of patients with cardiovascular disease are older adults, and comorbidities are therefore common; these may increase caregiver burden, especially if cognitive impairment is present. Caregiver responsibilities can range from hospital visitation and support through an acute illness to coordination of outpatient care, transportation to medical visits, emotional support, medication management, and with more advanced disease, assistance with basic activities (eg, feeding, dressing, ambulation). 27 Given changing US demographics, the total burden of informal cardiovascular disease caregiving (and its concurrent costs) is projected to increase considerably in the next 2 decades. 33 As such, the health of the caregiver is paramount.

Studies to date of caregivers have documented considerable stress, especially in the setting of acute hospitalization, where caregivers have been shown at risk for obesity, lower physical activity, and less healthy dietary behaviors at long‐term follow‐up. 31 , 32 Psychosocial stresses are also common among caregivers for patients with cardiovascular disease. These stresses include financial strain, sleep disturbance, and feelings of being overwhelmed. 31 , 32 Notably, the majority of caregivers for patients with cardiovascular disease are women, and many are more than 65 years of age. 34 Especially at older ages, caregivers may have their own health needs that are neglected because of time demands. 27 , 34

Relatively few interventions have been developed and tested to support caregivers. for patients with cardiovascular disease. 27 , 34 HF is the best studied condition to date, given its chronic and progressive nature with traditionally high caregiver involvement. To date, HF caregivers have reported multiple needs unmet by the current health care system, including being unprepared for managing medications and devices, balancing home and work responsibilities, engaging in their own self‐care, and handling emergencies. 34 Interventions directed at HF caregivers have ranged from face‐to‐face nurse psychoeducational support of patient–caregiver dyads to mobile health support for self‐care, and although a select number of these studies have shown a reduction in caregiver burden, to date a consistent effect has not been demonstrated. 34 Investigators have recommended that future studies adopt larger sample sizes and longer duration of follow‐up, incorporate objective measures, leverage technology, and focus on understudied populations (eg, younger, underrepresented minorities from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, nonspouses, and non‐English speakers). 27 , 34

FAMILY ENGAGEMENT DURING TIMES OF CRISIS

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had a considerable impact on family engagement in care. At the onset, many health care institutions strictly limited visitor entry because of concern for infection spread and inadequate personal protective equipment supply. 15 The pandemic response also shifted the priorities of health care delivery and led to the overstretching of resources in many care settings. As a result, efforts aimed at engaging families in care have been severely curtailed. 35

A restrictive visitor policy is associated with risks to patients and family members. 7 Inadequate family access can lead to social isolation, emotional distress, and mental health issues for both patients and family members. Vulnerable populations, such as those with cognitive impairment, underlying mental health conditions, or a language barrier, are likely to suffer the greatest consequences from the lack of family support. Flexible visitation policies have been shown to strengthen communication and trust between the health care team and family members, particularly for vulnerable patient populations. 36

During a pandemic response, there is a crucial need to balance the concerns of the health care system with the potential impact on the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of the patient and family. If future events require restrictions on family presence, a strict no‐visitor policy should be avoided whenever possible. A potential approach is to allow one designated essential family member per patient per hospital stay, particularly for people with cognitive deficits or delirium, and for those who have language barriers, psychiatric issues, or are receiving end‐of‐life care. Family members who are allowed to visit can be provided with information and training on infection control, physical distancing, and being screened for exposure. There is a need for studies to assess the safety of family presence in terms of infection risk to the patient, family, and health care team during a pandemic. Family members may be used as health care team extenders by assisting with appropriate tasks, such as hygiene, feeding, mobilization, and orientation, which can reduce burden on the medical staff while providing support to the patient. There is also a need to consider the disproportionate impact that the COVID‐19 pandemic has had on women, who more frequently act as the primary caregiver for the cardiac patient. Additional psychosocial resources could be provided to support caregivers during challenging times.

If family members cannot be present at the hospital, there should be a concerted effort by the health care professional to maintain regular and structured communication using secure video communication tools. Virtual family presence during team rounds can be integrated into the routine workflow. A family support liaison can also facilitate communication between the care team and families. Tools such as video communication should be given to patients so they may communicate often with family members to prevent social isolation. Once conditions permit, family members should be allowed back into hospitals and clinics.

SPECIAL POPULATION GROUPS

The presence of a supportive family positively impacts the likelihood that a patient will adhere to a medication regimen, consent to an invasive procedure, and keep follow‐up appointments. Recent data suggest that the presence of a family member at the bedside after open heart surgery may reduce objective measures of patient stress, including circulating cortisol levels. 37 Yet in certain communities, the same social determinants of health that lead to a greater burden of incident cardiovascular disease can have a negative impact on the level of family support.

A relative’s ability to be present for a family member’s office visit or medical procedure is influenced by their own socioeconomic status. Just like Black and Hispanic workers were less likely than others to be able to work remotely during the COVID‐19 pandemic because of their overrepresentation in essential service occupations, they likely find it more difficult to secure time off to attend a loved one’s appointment. 38 This presents a challenge to recruiting family members as allies in the care of patients from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

Studies have suggested that underrepresented groups benefit from telehealth appointments to improve adherence to prescribed medical therapy and self‐care regimens. 39 Although the impact of telehealth to encourage family support in patient care has not been studied extensively, leveraging technology may also be an important tool for these families. Furthermore, many mobile, cell‐phone–based applications help motivated patients track indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, and fluid intake. If patients transmit this information to a trusted family member in addition to the doctor, the relative could support the patient to help them achieve their goals and later provide valuable information in conference with the physician.

Ethnic and cultural differences may play an important role in decision making and end of life discussions. Health care professionals should be sensitive and open to patient and family needs of different identity groups. However, clinicians should not generalize ethnic and cultural differences in the decision‐making process; different perspectives should be anticipated, not presumed.

Underserved populations tend to reside in multigenerational households and, where Hispanic and non‐English speaking families are involved, young family members and teenagers may be more proficient in the English language and in American culture than the senior members of the household. Leveraging the higher language and cultural competency of the younger generation to enhance patient engagement in self‐care and health‐promoting strategies might be an underused strategy. A novel approach recruited bilingual Hispanic teenagers to serve as messengers about influenza vaccinations for internet and radio messages to the Hispanic community. 40 This resulted in a significant increase in middle‐aged and elderly Hispanic individuals attending a drive‐through event to receive vaccinations distributed by an academic medical center. This could easily serve as a model in which younger members of the household are not only used as occasional language translators, but as trusted members of the patient’s health care team to reduce vaccine hesitancy and reluctance to participate in clinical trials.

As America ages and life expectancy increases, caring for an older adult and being engaged in their care brings other challenges. With aging comes the increased incidence of senile dementia, which impacts everyone in the care circle, making adherence and the need for caregiver involvement in everyday decisions and care vital. 41 Health care professionals should see the older adult and caregiver group as one unit for framing plans of care. Older adult visits are also those that may benefit from telehealth if transportation is difficult. Should an older patient need day care or residential living, communication by the facility medical staff and family/caregivers must be maintained and advanced directives be clearly delineated.

Nontraditional family units should also be embraced as an untapped resource for bidirectional communication between the patient and physician, using technology, honest discussion, and compassion to enhance trust.

TRANSITION OF CARE FROM PEDIATRIC TO ADULT

The families, and particularly parents, of individuals who are born with or develop cardiovascular disease early in life have unique challenges in managing their child’s condition, including possibly facing multiple surgeries/procedures that can disrupt schooling and peer interactions, as well as result in financial strain. Parents must digest complicated information about their child’s diagnosis and collaborate with health care professionals to educate the patient and promote disease self‐management behaviors when developmentally appropriate. Transitioning from a pediatric care model (ie, parents make medical decisions and assume responsibility for disease management) to the adult care model (ie, the patient assumes the lead role in disease self‐management) is vital for ensuring the best long‐term health outcomes. Family engagement is essential for a successful transition.

Successful transition includes several components of disease self‐management, such as understanding the nature of one’s cardiac condition (ie, diagnosis, implications for future health), appropriately managing medications and cardiac follow‐up appointments, asking questions of health care professionals, and eventually transferring care from pediatric to adult clinicians. Formal transition education should begin between 13 and 16 years of age, using the adolescent’s maturity as a guide for initiation, 42 and would occur over several years. Education designed to address these components of successful transition may start in the clinic but should proceed at home with parents echoing the messages delivered by health care professionals.

Research has highlighted the important role of parents in this transition of care, including reinforcing information about diagnosis and proper disease self‐management. Parental knowledge is associated with their adolescent’s knowledge, which in turn is predictive of increased self‐reported disease management 43 and better understanding about transition. 42 Furthermore, parents discussing transfer of care with their adolescent is associated with increased self‐management skills. 43 However, parents and their adolescents differ in their perceptions of transition readiness during the process. Parents may overestimate their adolescent’s knowledge, and adolescents may perceive themselves as better able to engage in self‐management behaviors than their parents. 44 Although these discrepancies are unsurprising, it suggests that engaging the family in the transition process and encouraging communication in the home will aid successful transition.

Several barriers to involving families in transition have been qualitatively documented, including overprotection because of parents viewing their child as more vulnerable than healthy peers, discrepancies between parents and youth on perceptions of maturity, as well as caregiving exhaustion. 45 However, a sense of partnership with health care professionals, a clearly communicated timeline for acquiring disease self‐management skills and transfer of care, and providing informational tools that can be used in the home may go a long way in helping recruit parents as strong allies.

One tool that can enhance communication between health care professionals, parents, and adolescents in clinic is the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire, which comprises 20 items with 5 subscales, including managing medications, appointment keeping, tracking health issues, talking with clinicians, and managing daily activities (eg, helping to prepare meals, cleaning one’s room). 46 The questionnaire was designed to be given to both parents and youth to assess readiness for assuming these responsibilities. Discrepancies can be addressed during transition education visits and used to provide homework to families in between visits that can carry forth the discussion of transition at home.

KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

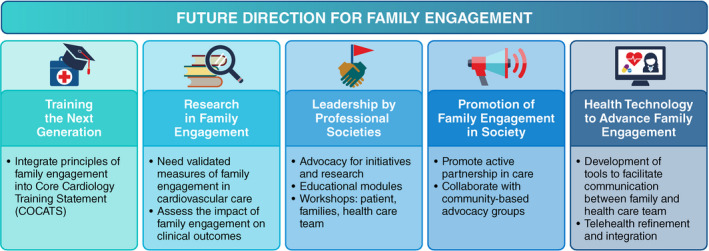

Family engagement in cardiovascular care is evolving. The existing knowledge gaps should be addressed to improve family engagement in cardiovascular care (Figure 2). Approaches to doing so include training health care professionals, furthering research specifically in the cardiovascular care setting, and establishing leaders within the medical community to promote these endeavors. Importantly, developing family‐focused communication methods through platforms such as digital applications may improve understanding between health care teams and families.

Figure 2. Future directions for family engagement.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

The integration of patient engagement into cardiovascular care results in improved quality of care. Embedded in patient‐centered care is patient–caregiver engagement, creating an environment where the patient, family, and health care team come together as partners to improve the quality of care, both in the hospital and outpatient settings. Family members or any designated caregiver should be viewed as collaborative partners in patient care.

There are limited data relating to the effectiveness of caregivers on the overall health and outcomes of patients living with cardiac disease, whether newly diagnosed or a chronic condition (Table). There is a lack of a conceptual model for how to best integrate family as a partner in the care of any given specific cardiac condition. There remain critical research gaps in the role of family, specifically their impact on outcomes for patients living with chronic cardiac disease and the cost or saving to the health care system and society, in addition to the psychological and physical health of the family member. There are significant gaps in research related to multiple caregivers. We recommend further research be done in this area. To date, the majority of the literature has focused on patients living with HF. 27 Ultimately, closing these gaps will require more research, given that it may have the potential to reduce hospitalization and urgent care visits, and ultimately the costs and burdens to our health care systems.

Table 1.

Suggestions for Clinical Practice

| Skills training | For caregivers of patients with chronic cardiac conditions, including application‐based training in problem solving; goal setting; medication, symptom, and device management; and communication |

| For the health care team, with additional research to determine how to best incorporate the caregiver into the cardiology health care team | |

| Development of remote technology | To assist caregivers with the clinical management of cardiac conditions, which include telehealth feedback among the health care team, family, and patient; to assist in the remote management of medical therapies, devices, and changes in symptoms |

| Psychosocial resources | Providing psychosocial resources to family members of patients with chronic cardiac conditions (ie, peer support groups, referrals for behavioral health professionals) |

| Advocacy | Advocate for policies to support caregivers, including government‐mandated leave to support caregivers (ie, Family Medical Leave Act). In the United States, the last legislation passed to support caregivers was the 2018 RAISE (Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage) Family Caregivers Act (S.1028/H.R.3759) |

| Research | Addressing research gaps, including the impact of the role of the family on outcomes of people living with chronic cardiac disease and family member psychological and physical health |

| Reimbursement | Reimbursement for health care systems and team members who promote and provide family‐based care, including caring for multiple members of a family, may also encourage family engagement efforts |

To date, there are no data to understand the use of family in risk factor modification, medication interventions for blood pressure control, and other preventative interventions. Innovative approaches to family‐based cardiovascular risk factor modification, similar to the community support model in hypertension control, can be developed. 47 There also remain significant gaps in physician education for how to engage the patient and family member, including how to incorporate family in telehealth visits.

Disclosures

Writing Group Disclosures

| Writing group member | Employment | Research grant | Other research support | Speakers’ bureau/honoraria | Expert witness | Ownership interest | Consultant/advisory board | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael J. Goldfarb | Jewish General Hospital | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Martha Gulati | University of Arizona | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Christine Bechtel | Self‐employed, X4 Health | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Quinn Capers IV | University of Texas Southwestern | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Ann de Velasco | WomenHeart of Miami Support Network | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| John A. Dodson | New York University School of Medicine | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Jamie L. Jackson | Nationwide Children’s Hospital | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Lisa Kitko | Penn State University College of Nursing | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Ileana L. Piña | Detroit Medical Center | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Erin Rayner‐Hartley | University of British Columbia (Canada) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Nanette K. Wenger | Emory University School of Medicine | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

This table represents the relationships of writing group members that may be perceived as actual or reasonably perceived conflicts of interest as reported on the Disclosure Questionnaire, which all members of the writing group are required to complete and submit. A relationship is considered to be significant if (1) the person receives $10 000 or more during any 12‐month period, or 5% or more of the person’s gross income; or (2) the person owns 5% or more of the voting stock or share of the entity, or owns $10 000 or more of the fair market value of the entity. A relationship is considered to be modest if it is less than significant under the preceding definition.

Reviewer Disclosures

| Reviewer | Employment | Research grant | Other research support | Speakers’ bureau/honoraria | Expert witness | Ownership interest | Consultant/advisory board | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan C. Lopez‐Mattei | University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Sharon L. Mulvagh | Mayo Clinic–Rochester | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Shelley Zieroth | University of Manitoba (Canada) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

This table represents the relationships of reviewers that may be perceived as actual or reasonably perceived conflicts of interest as reported on the Disclosure Questionnaire, which all reviewers are required to complete and submit. A relationship is considered to be significant if (1) the person receives $10 000 or more during any 12‐month period, or 5% or more of the person’s gross income; or (2) the person owns 5% or more of the voting stock or share of the entity, or owns $10 000 or more of the fair market value of the entity. A relationship is considered to be modest if it is less than significant under the preceding definition.

Supporting information

The American Heart Association makes every effort to avoid any actual or potential conflicts of interest that may arise as a result of an outside relationship or a personal, professional, or business interest of a member of the writing panel. Specifically, all members of the writing group are required to complete and submit a Disclosure Questionnaire showing all such relationships that might be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest.

This statement was approved by the American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee on November 16, 2021, and the American Heart Association Executive Committee on December 14, 2021. A copy of the document is available at https://professional.heart.org/statements by using either “Search for Guidelines & Statements” or the “Browse by Topic” area.

The American Heart Association requests that this document be cited as follows: Goldfarb MJ, Bechtel C, Capers Q 4th, de Velasco A, Dodson JA, Jackson JL, Kitko L, Piña IL, Rayner‐Hartley E, Wenger NK, Gulati M; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Hypertension; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Engaging families in adult cardiovascular care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025859. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.025859

The expert peer review of AHA‐commissioned documents (eg, scientific statements, clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews) is conducted by the AHA Office of Science Operations. For more on AHA statements and guidelines development, visit https://professional.heart.org/statements. Select the “Guidelines & Statements” drop‐down menu, then click “Publication Development.”

References

- 1. Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldfarb M, Bibas L, Burns K. Patient and family engagement in care in the cardiac intensive care unit. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown SM, Rozenblum R, Aboumatar H, Fagan MB, Milic M, Lee BS, Turner K, Frosch DL. Defining patient and family engagement in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:358–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1936LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, Spuhler V, Todres ID, Levy M, Barr J, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient‐centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, et al. Guidelines for family‐centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balik B, Conway J, Zipperer L, Watson J. Achieving an exceptional patient and family experience of inpatient hospital care. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Institute for Health Care Improvement; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldfarb MJ, Bibas L, Bartlett V, Jones H, Khan N. Outcomes of patient‐ and family‐centered care interventions in the ICU: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1751–1761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Black P, Boore JR, Parahoo K. The effect of nurse‐facilitated family participation in the psychological care of the critically ill patient. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:1091–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huffines M, Johnson KL, Smitz Naranjo LL, Lissauer ME, Fishel MA, D'Angelo Howes SM, Pannullo D, Ralls M, Smith R. Improving family satisfaction and participation in decision making in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2013;33:56–69. doi: 10.4037/ccn2013354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cené CW, Johnson BH, Wells N, Baker B, Davis R, Turchi R. A narrative review of patient and family engagement: the "foundation" of the medical "home". Med Care. 2016;54:697–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S, Schmitt MH, Puntillo K, Kitto S. Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2016;19:1183–1202. doi: 10.1111/hex.12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Majid U. The dimensions of tokenism in patient and family engagement: a concept analysis of the literature. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:1610–1620. doi: 10.1177/2374373520925268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, Foster M. Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family‐centered care in adult critical care. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18:543–552; quiz 553. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Castiel J, Chen‐Tournoux A, Thanassoulis G, Goldfarb M. A patient‐led referral strategy for cardiovascular screening of family and household members at the time of cardiac intensive care unit admission. CJC Open. 2020;2:506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldfarb M, Bibas L, Burns K. Family engagement in the cardiovascular intensive care unit in the COVID‐19 era. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1327.e1–1327.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosa RG, Falavigna M, da Silva DB, Sganzerla D, Santos MMS, Kochhann R, de Moura RM, Eugenio CS, Haack T, Barbosa MG, et al. Effect of flexible family visitation on delirium among patients in the intensive care unit: the ICU visits randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:216–228. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oczkowski SJ, Mazzetti I, Cupido C, Fox‐Robichaud AE. The offering of family presence during resuscitation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:41. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0107-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyers TA, Eichhorn DJ, Guzzetta CE, Clark AP, Klein JD, Taliaferro E, Calvin A. Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation: the experience of family members, nurses, and physicians. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2004;26:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cao V, Tan LD, Horn F, Bland D, Giri P, Maken K, Cho N, Scott L, Dinh VA, Hidalgo D, et al. Patient‐centered structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds in the medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:85–92. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tallent S, Turi JL, Thompson J, Allareddy V, Hueckel R. Extending the radius of family‐centered care in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit through virtual rounding. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021;34:205–212. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Jourdain M, Bornstain C, Wernet A, Cattaneo I, Annane D, Brun F, Bollaert PE, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown SM, Bell SK, Roche SD, Dente E, Mueller A, Kim TE, O'Reilly K, Lee BS, Sands K, Talmor D. Preferences of current and potential patients and family members regarding implementation of electronic communication portals in intensive care units. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:391–400. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-638OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bibas L, Peretz‐Larochelle M, Adhikari NK, Goldfarb MJ, Luk A, Englesakis M, Detsky ME, Lawler PR. Association of surrogate decision‐making interventions for critically ill adults with patient, family, and resource use outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e197229. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldfarb M, Slobod D, Dufresne L, Brophy JM, Sniderman A, Thanassoulis G. Screening strategies and primary prevention interventions in relatives of people with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noonan MC, Wingham J, Taylor RS. 'Who cares?' The experiences of caregivers of adults living with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary artery disease: a mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020927. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fivecoat HC, Sayers SL, Riegel B. Social support predicts self‐care confidence in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17:598–604. doi: 10.1177/1474515118762800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kitko L, McIlvennan CK, Bidwell JT, Dionne‐Odom JN, Dunlay SM, Lewis LM, Meadows G, Sattler ELP, Schulz R, Stromberg A. Family caregiving for individuals with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e864–e878. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Stromberg A. Changing needs of heart failure patients and their families during the illness trajectory: a challenge for health care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15:298–300. doi: 10.1177/1474515116653536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vellone E, Biagioli V, Durante A, Buck HG, Iovino P, Tomietto M, Colaceci S, Alvaro R, Petruzzo A. The influence of caregiver preparedness on caregiver contributions to self‐care in heart failure and the mediating role of caregiver confidence. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;35:243–252. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iovino P, Lyons KS, De Maria M, Vellone E, Ausili D, Lee CS, Riegel B, Matarese M. Patient and caregiver contributions to self‐care in multiple chronic conditions: a multilevel modelling analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;116:103574. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mochari‐Greenberger H, Mosca L. Caregiver burden and nonachievement of healthy lifestyle behaviors among family caregivers of cardiovascular disease patients. Am J Health Promot. 2012;27:84–89. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110606-QUAN-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aggarwal B, Liao M, Christian A, Mosca L. Influence of caregiving on lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors among family members of patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0852-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dunbar SB, Khavjou OA, Bakas T, Hunt G, Kirch RA, Leib AR, Morrison RS, Poehler DC, Roger VL, Whitsel LP. Projected costs of informal caregiving for cardiovascular disease: 2015 to 2035: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e558–e577. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nicholas Dionne‐Odom J, Hooker SA, Bekelman D, Ejem D, McGhan G, Kitko L, Strömberg A, Wells R, Astin M, Metin ZG, et al. Family caregiving for persons with heart failure at the intersection of heart failure and palliative care: a state‐of‐the‐science review. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:543–557. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9597-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hwang DY, Zhang Q, Andrews A, LaRose K, Gonzalez M, Harmon L, Vermoch K. The initial impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on ICU family engagement: lessons learned from a collaborative of 27 ICUs. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3:e0401. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hurst H, Griffiths J, Hunt C, Martinez E. A realist evaluation of the implementation of open visiting in an acute care setting for older people. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:867. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4653-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koyuncu A, Yava A, Yamak B, Orhan N. Effect of family presence on stress response after bypass surgery. Heart Lung. 2021;50:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams JC, Anderson N, Holloway T, Samford E III, Eugene J, Isom J. Reopening the United States: Black and Hispanic workers are essential and expendable again. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1506–1508. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trief PM, Izquierdo R, Eimicke JP, Teresi JA, Goland R, Palmas W, Shea S, Weinstock RS. Adherence to diabetes self care for white, African‐American and Hispanic American telemedicine participants: 5 year results from the IDEATel project. Ethn Health. 2013;18:83–96. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.700915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. KTVT . Doctors set up free drive‐up flu shot clinic in underserved community. 2021. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://localnews8.com/news/2020/10/27/doctors‐set‐up‐free‐drive‐up‐flu‐shot‐clinic‐in‐underserved‐community

- 41. Im J, Mak S, Upshur R, Steinberg L, Kuluski K. 'The Future is Probably Now': understanding of illness, uncertainty and end‐of‐life discussions in older adults with heart failure and family caregivers. Health Expect. 2019;22:1331–1340. doi: 10.1111/hex.12980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clarizia NA, Chahal N, Manlhiot C, Kilburn J, Redington AN, McCrindle BW. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease: perspectives of the patient, parent and health care provider. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e317–e322. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70145-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stewart KT, Chahal N, Kovacs AH, Manlhiot C, Jelen A, Collins T, McCrindle BW. Readiness for transition to adult health care for young adolescents with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:778–786. doi: 10.1007/s00246-017-1580-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harrison D, Gurvitz M, Yu S, Lowery RE, Afton K, Yetman A, Cramer J, Rudd N, Cohen S, Gongwer R, et al. Differences in perceptions of transition readiness between parents and teens with congenital heart disease: do parents and teens agree? Cardiol Young. 2021;31:957–964. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120004813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delaney AE, Qiu JM, Lee CS, Lyons KS, Vessey JA, Fu MR. Parents' perceptions of emerging adults with congenital heart disease: an integrative review of qualitative studies. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:362–376. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wood DL, Sawicki GS, Miller MD, Smotherman C, Lukens‐Bull K, Livingood WC, Ferris M, Kraemer DF. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ): its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx‐Drew D, et al. A cluster‐randomized trial of blood‐pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1291–1301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials