Abstract

The aim of this scoping review initiated by the Education, Implementation and Teams Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation was to identify faculty development approaches to improve instructional competence in accredited life support courses. We searched PubMed, Ovid Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify studies published from January 1, 1966 to December 31, 2021 on approaches to improve faculty development for life support courses. Data on participant characteristics, interventions, design, and outcomes of included studies were extracted. Of the initially identified 10 310 studies, we included 20 studies (5 conference abstracts, 1 short communication, 14 full‐length articles). Among them, 12 studies aimed to improve instructors/candidates’ teaching ability in basic life support courses. A wide variety of interventions were identified. The interventions were categorized into 4 themes: instructor qualification/training (n=9), assessment tools (n=3), teaching skills enhancement (n=3), and additional courses for instructors (n=5). Most studies showed that these interventions improved specific teaching ability or confidence of the instructors and learning outcomes in different kinds of life support courses. However, no studies addressed clinical outcomes of patients. In conclusion, the faculty development approaches for instructors are generally associated with improved learning outcomes for participants, and also improved teaching ability and self‐confidence of the instructors. It is encouraged that local organizations implement faculty development programs for their teaching staff of their accredited resuscitation courses. Further studies should explore the best ways to strengthen and maintain instructor competency, and define the cost‐effectiveness of various different faculty development strategies.

Keywords: cardiac arrest, faculty development, instructor training

Subject Categories: Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Quality and Outcomes

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ALS

advanced life support

- BLS

basic life support

- EIT

Education, Implementation, and Teams

- ERC

European Resuscitation Council

- ILCOR

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- TTT

train‐the‐trainer

Cardiac arrest affects millions of patients worldwide and patients with cardiac arrest have high mortality rate and poor outcomes. 1 As early delivery of high‐quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has a significant impact on survival, it is pivotal to train the public and health care professionals to perform correct resuscitation skills, including basic and advanced life support. 2 A key variable supporting the acquisition and retention of resuscitation skills is the quality of education delivered by resuscitation instructors. 3 , 4

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) proposed the concept of the formula for survival and regarded educational efficiency as 1 of 3 factors which would affect survival. 5 Many strategies have been proposed to develop comprehensive cost‐effective training programs, and to improve survival. 4 These strategies focused on training courses for adult and pediatric life support providers, either laypeople or health care professionals. The instructors, who motivate the learners and deliver resuscitation knowledge and skill instructions in the courses, play an essential role in improving educational efficiency. Therefore, organizations, such as the American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) have developed training programs for instructor candidates. Improved instructional competence is associated with a change in behavior, the true definition of learning a psychomotor activity, which may correlate with favorable outcomes from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. 5 In a recent scientific statement, the American Heart Association proposed that faculty development for resuscitation instructors is a central variable driving educational efficiency and local implementation. 4 Unfortunately, certified instructors do not always assess CPR skills of the course participants properly which may have negative influences on the learning outcomes. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9

To our knowledge, no reviews have addressed faculty development approaches to improve instructional competence in life support programs. The Education, Implementation, and Teams (EIT) Task Force of ILCOR ranked this question in their discussion as important and agreed it was necessary to perform a scoping review to ascertain what has been published in the field. Therefore, the aim of this review is to identify interventions to support instructors to optimize course participants’ learning in life support courses.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We report this scoping review, in accordance with the checklist of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews. 10 We included studies investigating any faculty development approach to improve instructional competence in accredited life support courses, approved by professional organizations (eg, ERC, AHA). The population of the scoping review included both instructor candidates and certified instructors in life support courses. Interventions including instructor training, retraining or recertification courses were eligible. The outcomes of interest included both educational and clinical outcomes. Educational outcomes included: (1) skill performance of trainees of the instructors in actual resuscitation; (2) knowledge, instructional skills, and attitudes of instructors at the end of instructor training course and some period of time after the end of instructor training course; (3) confidence of instructors to teach trainees at the end of instructor training course and some period of time after course completion; (4) knowledge, skill performance, attitudes, willingness, and confidence of trainees of the instructors immediately at end of the provider course or some period of time after course completion. Clinical outcomes represented outcomes of patients resuscitated by trainees who were taught by the instructors, including survival with favorable neurological outcome at discharge, survival to hospital admission or discharge, and return of spontaneous circulation.

Our search strategy included all years from the date of inception of the database, and all languages, as long as there was an English abstract. Study types consisted of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized studies, including nonrandomized controlled trials, interrupted time series, controlled before‐and‐after studies, cohort studies, case‐control studies. Unpublished studies (eg, conference abstracts, trial protocols), letters, editorials, comments, case series, and case reports were also included. Interventions with nonaccredited life support courses and life support courses as part of curriculum development in other medical educational courses were excluded.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

For this scoping review, we searched the literature in PubMed, Ovid Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials up to December 31, 2021. No grey literature was searched. The time range was set from 1966 because the AHA published the first guidelines for CPR in 1966. 11 Reference lists of identified studies were checked for additional relevant articles. The searching strategies were initially created by a librarian (Hsin‐Ping Chiu) of the National Taiwan University Medical Library and then were reviewed by Task Force scoping review team members (M.J.H., Y.C.K., A.C., K.G.L., and T.L.S.). The detailed search strategy is shown in Data S1.

Study Selection

Titles were screened independently by 2 reviewers (Y.C.K. and M.J.H.) after duplicates were removed. The process was followed by title and abstract screening, and full‐text assessment was conducted if the article was deemed to be potentially relevant until December 31, 2021. The 2 reviewers and 2 additional reviewers (A.C. and K.G.L.) launched a discussion and reached a consensus if different opinions developed during the selection process.

Data Charting Process, Data Items, and Synthesis of Results

After determining the final included articles, a spreadsheet specifically adapted for this review was created by 1 reviewer (Y.C.K.) to chart extracted data from the articles. The extracted data were checked for accuracy by another reviewer (M.J.H.). The content included details of author(s), publication year, country, study design, identity of the participants, evaluation methods, and key outcomes. The extracted information was used during review team meetings to obtain an overall perspective from the literature. Disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

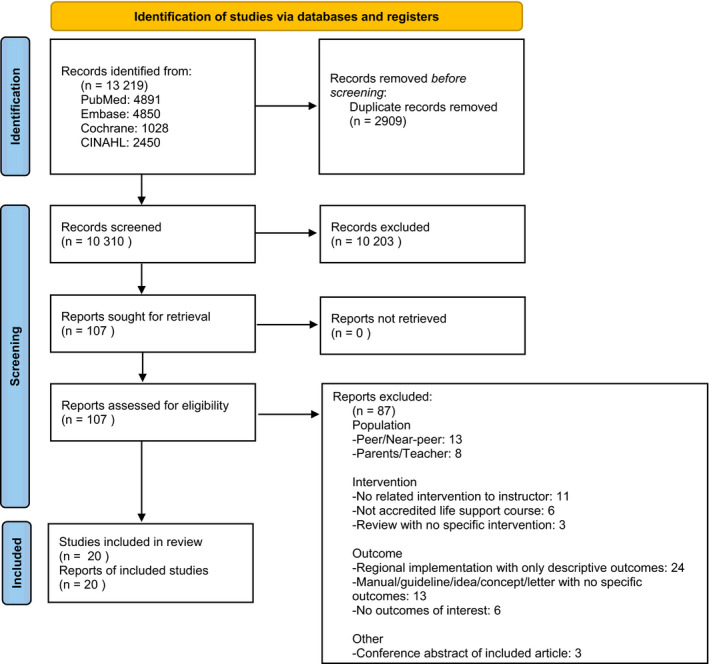

A search of the databases identified a total of 13 219 records. After removing 2909 duplicates, 10 310 records were screened by reviewing the titles and abstracts; 107 potentially relevant records were included in the full‐text assessment and a total of 20 studies, 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 including 5 conference abstracts, 15 , 21 , 25 , 26 , 31 1 short communication 29 and 14 full‐length articles,† were included in the final analysis. A flow diagram of the reviewing process is shown in Figure. There were 6 randomized controlled trials, 12 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 20 12 nonrandomized studies, 15 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 and 2 descriptive surveys. 13 , 23 Interventions in the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Figure .

Flow diagram of included studies. CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Article type | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Comparisons | Outcomes | Course | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instructor qualification/training | |||||||

|

Einspruch EL et al 18 (United States, 2011) |

Article | RCT |

Instructor candidates (N=24) |

Internet‐based AHA Core Instructor Course (CIC) (n=11) |

Traditional classroom‐based AHA CIC (n=13) |

Primary outcome: candidates’ scores on their pretest and posttest ratings (given by expert rater and study coordinator). No difference in pretest and posttest scores/ratings. Candidates in the Online group had significantly higher adjusted posttest scores (P=0.035). | BLS |

|

Feltes M et al 19 (United States, 2019) |

Article | Non‐RCT | Faculty and chief residents in anesthesiology, pediatrics, and emergency medicine |

First PALS course (Group1): PALS with train‐the‐trainer programs, included 4 interactive presentations on learner‐focused teaching methods (n=9). Second PALS course (Group2): 28 additional residents trained by the newly trained ‘‘trainers.’’ |

Compare pass rate, test score and questionnaire response among 2 groups. | The pass rate (>80% on the posttest) was 67% for group 1 and 79% for group 2. Both groups showed improvement in their comfort level in caring for sick children after the PALS course. Both groups showed improvement in their comfort level in caring for sick children after the PALS course. | PALS |

|

Rajapakse BN et al 27 (Australia, 2013) |

Article | Non‐RCT | Non‐specialist doctors from selected rural hospital in Sri Lanka |

First phase: 2‐day instructor course with train‐the‐trainer model (include knowledge of the resuscitation syllabus and instructor workshop) (n=8) Second phase: sending the “trained trainers” to deliver 8 resuscitation training workshops (BLS/ALS), including 57 participants. |

N/A | Primary outcome: assess resuscitation knowledge and skill endpoints (pre‐test/posttest/6‐wk/12‐wk) among the peripheral hospital doctors taught by the “trained trainers”. (Knowledge assessment: MCQ test. Skills assessment: performance in a cardiac arrest scenario.) Mean MCQ scores significantly improved over time (P<0.001), and a significant improvement was noted in specific resuscitation skills. | ALS |

| Ismail A et al 22 (Palestine, 2019) | Article | Non‐RCT | Medical students from Al Azhar University‐Gaza (N=117) | BLS and CPR instructor course (12 hr practical BLS and CPR skills+4 hr communication and didactical skills) (material based on the ERC 2015 guidelines) | N/A |

95 medical students completed the online questionnaire. Students reported to be motivated to participated the course for building the capacity of the community (n=29), contributing to better coping with the tense situation the recurrent incursions (n=22). Nearly two‐thirds (n=61, 64.2%) described a sense of belonging and duty to the community as their most important inspiration. 58 training sessions with 1312 lay participants were completed after the 58 training sessions with 1312 lay participants were completed (so far). |

BLS |

|

Benthem Y et al 15 (Netherlands, 2012) |

Conference Abstract | Non‐RCT | Senior student attending DRC train‐the ‐trainer course (n=10) | 2‐days train the trainer course for BLS (in‐service training+train the trainer) held by DRC | Student control instructors (in‐service training only)(n=14) |

350 students were randomized to receive training from either a control instructor (n=202) or DRC‐instructor (n=148). 1. DRC‐instructors scored significantly higher on the practical training of BLS (P=0.008). 2. Control instructors performed significantly better on parts of the theoretical BLS training (P=0.001). 3. The type of instructor had no effect on the result of the final exam of the first‐year students (P=0.949). |

BLS |

|

Pollock L et al 26 (UK, 2011) |

Conference Abstract | Non‐RCT | Senior health care workers from 25 hospitals in 18 Malawian health care districts (N=79) | 4‐day train the trainer course including local ETAT implementation planning workshop | N/A | Pre and postcourse knowledge tests (n=79) showed improvement in both individual and overall scores (overall mean score pre: 10.27 post: 12.48 P=<0.001). Eleven hospitals had obtained funding for participants to train colleagues: a further 272 health care workers had been trained in triage skills. | Pediatric resuscitation (WHO ETAT) |

|

López‐Herce J et al 24 (Spain, 2021) |

Article | Non‐RCT | Participants from different professional groups in 24 pediatric and neonatal CPR instructor courses held over 21 years (1999 to 2019). (N=516) | Pediatric and neonatal CPR instructor courses (26–28 h distributed over 3–4 days; 2 phases: an initial preparation phase and a phase involving face‐to‐face sessions) | N/A |

Theoretical evaluation by multiple‐choice questions (score 1–10); practical evaluation score ranging from 1 to 5. (Criteria for passing: theory >6.5 and practice >3.5). 554 passed theory and practice tests (98.9%). Mean (SD) score in theory tests was 9.2 (0.8) out of 10. The mean score obtained in all practice tests was >3.5 out of 5. |

PBLS |

|

Wada M et al 30 (Japan, 2015) |

Article | Non‐RCT | Participants in instructor course of neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation included lectures and instruction practice. (N=232) | New instructor course included lectures, instruction practice and resuscitation scenarios developed by the participants (n=143) |

Conventional instructor training course with practicing using the text in advance (n=89) |

Participants in new course have more confidence to teach neonatal CPR (>90% vs 50%–60%, P<0.001), could instruct on resuscitation procedures and practice (63.6% vs 38.2%, P<0.001). Significantly more participants in new course work as instructors 6 mo after certification (60% vs 34%, P<0.001). | NRP |

|

Kim EJ et al 23 (Korea, 2019) |

Article | Descriptive survey study | Sampling of Korean BLS instructors. (N=213) | Web‐based questionnaire survey with a 29 item Competence Importance–Performance scale | N/A | Factor analysis identified several important factors for the competence of instructors: assessment, professional foundations, planning and preparation, educational method and strategies and evaluation. The importance and performance analysis matrix showed that training priorities for novice instructors were communication with learners and instructors, learner motivation, educational design, and qualifications of instructors, whereas checking equipment status and educational environment had the highest training priority for experienced instructors. | BLS |

| Assessment tools | |||||||

|

Al‐Rasheed RS et al 12 (United States, 2013) |

Article | RCT |

Recruited BLS CPR‐I/Cs (N=30) |

Phase 1: All participants performed compression 2‐minute simulation, then reviewed 6 videos of simulated CPR performances. Phase 2: Repeat the protocol, participants in the experimental group were provided with real‐time compression feedback. |

Phase 1. Determine the chest compression quality and the accuracy of CPR‐I/C chest compression assessment Phase 2. Determine CPR quality and assessment skills through cardiac arrest simulations with objective in‐scenario performance feedback |

For CPR quality: All CPR‐I/C subjects compressed suboptimally at baseline. Real‐time manikin feedback improved the proportion of subjects with more than 77% correct compressions to 0.53 (P<0.01). For chest compression assessment: Video review data revealed persistently low CPR‐I/C assessment accuracy. Correlation between subjects’ correctness of compressions and their assessment accuracy remained poor regardless of interventions. |

BLS |

|

Yamahata Y et al 31 (Japan, 2014) |

Conference Abstract | Non‐RCT | Experienced instructors (n=14) and fresh instructors (n=10) | Evaluate the accuracy of chest compressions, and the self‐learning ability with recorded chest compression by motion capture camera. | Compare assessment of chest compression quality among novice/experienced instructors and motion camera |

1. Score between experienced instructors and the device is similar (2.67 of 4–2.58 of 4). 2. Fresh instructors tend to give higher score than the device (2.57 of 4–2.26 of 4), and sometimes give certification to inappropriate performances. 3. Ability of fresh instructors after self‐training is improved, but cannot catch up to experienced instructors. |

Not mentioned (BLS/CPR) |

|

Nallamilli S et al 25 (UK, 2012) |

Conference Abstract | Non‐RCT | Accredited instructors were asked to deliver BLS training using Skillmeter manikins | Accredited instructors were asked to deliver BLS training using Skillmeter manikins | N/A | 97% of BLS instructors within our course regarded the program to be useful, with the majority stating that Skillmeter –based training was better delivered by themselves, rather than course directors (59% vs 38%). | BLS |

| Teaching skills enhancement | |||||||

|

Baldwin LJL et al 14 (UK, 2015) |

Article | Randomized crossover study | ERC BLS instructors (N=58) | Teach BLS using either the learning conversation structured methods or sandwich feedback technique | Crossover study, compare with alternative method |

1. Scores (VAS) assigned to use of the learning conversation structured methods by instructors were significantly more favorable than for the sandwich technique across most domains relating to instructor perception of the feedback technique, and all skills‐based domains. 2. No difference was seen in either assessment pass rates (80.9% sandwich technique vs. 77.2% learning conversation structured methods; OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.85–1.84; P=0.29). |

BLS |

|

Cheng A et al 17 (Canada, 2013) |

Article | RCT | Novice instructors participates in Examining Pediatric Resuscitation Education Using Simulation and Scripted Debriefing network simulation programs from 2008 to 2011(N=90) |

For novice instructors to use (1) non‐scripted debriefing and low physical‐realism simulator (n=23), (2) scripted debriefing and low physical‐realism simulator (n=22), (3) non‐scripted debriefing and high physical‐realism simulator (n=23), (4) scripted debriefing and high physical‐realism simulator (n=22). |

Compare with the alternative intervention | Students’ performance in scripted debriefing showed greater improvement in knowledge (mean MCQ‐PPC, 5.3% vs 3.6%; P=0.04) and team leader behavioral performance (median BAT‐PPC, 16% vs 8%; P=0.03). PPC: postintervention vs preintervention comparison | PALS |

|

Herrero P et al 21 (Spain, 2010) |

Conference Abstract | Non‐RCT | Instructor candidates in BLS / AED instructor courses and one ALS instructors course. (N=180) | New training tool consisting in a tape recording and a later critical viewing of a lecture | N/A | All candidates (100%) considered interesting to compare the subjective impression with the objectivity viewing, and the opinion was positive on 100% of trainers who used this tool. | BLS/AED, ALS |

| Additional course for instructors | |||||||

|

Goldman SL et al 20 (United States, 1986) |

Article | RCT | Candidates enrolled from 2 successive Wisconsin Heart Association ACLS Instructor Courses in 1985. (N=92) | Specific educational program to teach instructors to evaluate team leader performance in cardiac arrest simulations (reviewed commonly observed errors and critical error identification) | No formal educational program |

Each group of instructor candidates then reviewed and rated the 3 video tape team leader performances. The experimental group identified more critical errors (P=0.006), more correct grade assignments (P=0.026), and more observed errors (P=0.0001). |

ALS |

|

Thorne CJ et al 29 (UK, 2013) |

Short communication | Non‐RCT | ERC accredited instructors (N=18) | Additional training through the Assessment Training Program (ATP) (assessors) (n=9) | Standard ERC instructor training (n=9) and ERC instructor trainer (n=6) | Seventy‐three candidate assessments were undertaken. Instructors (49.3%) had lower raw pass rates than assessors (67.1%) and instructor trainers (64.4%). There was a significant difference in overall decisions between instructors and instructor trainers (P=0.035), and instructors and assessors (P=0.015). Instructors were more prone to incorrectly failing candidates than assessors (sensitivities of 80.5% and 63.8%, P=0.077). | BLS/AED |

|

Thorne CJ et al 28 (UK, 2015) |

Article | Non‐RCT |

ERC instructor course candidates (n=47) and qualified ERC BLS/AED instructors (n=20) |

Instructors undertook Assessment Training Program (ATP) as additional training, focuses on decision making in equivocal situations. (n=20) | Candidates attending an ERC BLS/AED instructor course. (n=47) |

Primary outcome: Assessment confidence over ten‐point Visual Analogue Scales collected by pre‐ and post‐course questionnaires. Overall confidence on the ERC BLS/AED instructor and ATP assessors course rose from 5.9 (SD 1.8) to 8.7 (SD 1.4) (P<0.001) and from 8.2 (SD 1.4) to 9.6 (SD 0.5) (P<0.001), respectively. Assessors (mean 9.6, SD 0.5) were significantly more confident at assessing than instructors (mean 8.7, SD 0.5) (P<0.001). |

BLS/AED |

|

Amin HJ et al 13 (Canada, 2013) |

Article | Descriptive survey study | Experienced NRP instructors or instructor trainers participating neonatal resuscitation workshop (N=17) |

Pre‐ and post‐test questionnaire to determine perceptions over the neonatal resuscitation Workshop (lectures; scenario development and enactment; video recording and playback; and debriefing). |

N/A | Pre‐ and post‐test comparisons showed significant improvements in participants’ perceptions of their ability to: conduct (as an instructor) a simulation (P<0.05); participate in a simulation (P<0.05); recognize cues (P<0.05); and debrief (P<0.05). | NRP |

|

Breckwoldt J et al 16 (Germany, 2014) |

Article | RCT | Clinical teachers (N=18) from emergency medicine and anaesthesiology in a university teaching hospital | Two‐day clinical teacher training, content including “role of the teacher,” “needs of learners,” “providing feedback,” “structure of session,” “defining learning objectives,” “activating learners,” “teaching of skills,” “teaching with patients” (n=9) | No clinical teacher training (n=9) |

Student’s outcome: Students taught by untrained teachers performed better in the SCE domains “alarm call” (P<0.01) and “ventilation” (P=0.01). No significant difference in chest compression and use of AED. Teachers’ outcome: Teaching quality was rated significantly better by students of untrained teachers (P=0.05). |

BLS+EM course |

ACLS indicates advanced cardiovascular life support; AED, automated external defibrillator; AHA, American Heart Association; ALS, advanced life support; ATP, Assessment Training Program; BAT, Behavioral Assessment Tool (team leader performance); BLS, basic life support; CIC, Core Instructor Course; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DRC, Dutch Resuscitation Council; EM, emergency medicine; ERC, European Resuscitation Council; ETAT, Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment; EXPRESS, Examining Pediatric Resuscitation Education Using Simulation and Scripted Debriefing; I/Cs, instructors/coordinators; MCQ, multiple choice question; NRP, neonatal resuscitation program; PALS, pediatric advanced life support; PBLS, pediatric basic life support; PPC, post‐intervention vs preintervention comparison; and RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Results of Individual Studies and Synthesis of Results

A thematic analysis was conducted following review of the articles and discussed among the authors. After the studies were extracted, meetings of the ILCOR EIT Task Force were held, and a consensus was reached to classify the interventions reported in the included articles into 4 themes: instructor qualification/training, assessment tools, teaching skills enhancement, and additional courses for instructors. Key characteristics and outcomes of included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interventions to Improve Instructional Competence

| Intervention | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Instructor qualification/training | ||

| Internet‐based AHA CIC for BLS 18 | Comparing internet‐based AHA CIC (Core Instructor Course) with traditional classroom‐based AHA CIC | No difference for instructors in pretest and posttest practical scores between classroom‐based and Internet‐based CIC. Candidates in the online group had significantly higher adjusted posttest scores. |

| Train‐the‐trainer course 15 , 19 , 22 , 26 , 27 | Instructor course with train‐the‐trainer model, sending the “trained trainers” to deliver further resuscitation training. | Train‐the‐trainer programs may be effective in improving resuscitation knowledge and skills, and are important for developing local expertise. |

| System‐wide instructor training program24 | Retrospective analysis of 24 pediatric and neonatal CPR instructor courses certificated by SPNRG held between 1999 and 2019. | Specific pediatric and neonatal CPR instructor course is an adequate method for sustainable training health professionals to teach pediatric resuscitation. |

| Modified instructor course with lectures, instruction practice and self‐developed resuscitation scenarios 30 | Comparing new instructor course with conventional instructor training. The new course included lectures and instruction practice, and was characterized by using a scenario they had developed themselves to provide instructions. | Participants are more confident teaching neonatal CPR when participating a new course when compared with the traditional course. |

| Web‐based questionnaire survey for instructors 23 | Web‐based survey with a 29 item Competence Importance Performance scale to identify several important factors for the competence of instructors. | Several important factors for the competence of instructors identified by factor analysis. |

| 2. Assessment tools | ||

| Assessment for chest compression with real‐time compression feedback 12 | To determine the chest compression quality and the accuracy of CPR‐I/C (instructor/coordinator) chest compression assessment, with/without real‐time compression feedback. | Real‐time compression feedback during simulation improved CPR‐I/C’s chest compression performance skills, without comparable improvement in chest compression assessment skills in video review. |

| Assessment for chest compression with self‐learning 31 | To determine the ability of instructors to evaluate the accuracy of chest compressions, and the self‐learning ability with recorded chest compression by motion capture camera. | Ability of novice instructors to assess chest compressions after self‐training is improved, but cannot catch up to experienced instructors. |

| Deliver BLS training using fully body sensor‐equipped manikins 25 | Accredited instructors were asked to deliver BLS training using sensor‐equipped manikins. | Instructors feel useful and confident when delivering course and may be beneficial to trainer’s perception. |

| 3. Teaching skills enhancement | ||

| Different feedback method 14 | Compare the sandwich technique and learning conversation structured methods of feedback delivery in BLS training. | Using learning conversation structured methods by instructors were significantly more favorable than using the sandwich technique, and may give instructors more confidence. |

| Using standardized script by novice instructors to facilitate team debriefing 17 | To determine whether use of a scripted debriefing by novice instructors and/or simulator physical realism affects knowledge and performance in simulated cardiopulmonary arrests. | The use of a standardized script to debrief by novice instructors improves students’ acquisition of knowledge and team leader behavioral performance during subsequent simulated cardiopulmonary arrests. |

| Tape recording and a later critical viewing of a lecture 21 | Record the lecture provided by BLS/AED or ALS instructor candidates with a tape, a later video review and oral self‐assessment. | Candidates considered interesting and feel positive to compare the subjective impression with the objectivity viewing. |

| 4. Additional course for instructors | ||

| Educational program to teach ACLS instructors to evaluate team leader performance 20 | Educational program to review commonly observed errors and to identify critical errors in particular. | Trained instructors identified more critical errors, and gave more correct grade assignments. |

| ATP 28 , 29 | Instructors undertook ATP as additional training, focusing on decision making in equivocal situations. | Trained instructors were less prone to incorrectly failing candidates. (Thorne CJ, 2013). Instructors with additional training were significantly more confident at assessing. (Thorne CJ, 2015). |

| Neonatal resuscitation workshop 13 | 2‐day neonatal resuscitation workshop (content: lectures; scenario development and enactment; video recording and playback; and debriefing) to enhance teaching abilities. | Pre‐ and post‐test comparisons showed significant improvements in participants’ perceptions of their teaching ability. |

| Clinical teacher training course/workshop (enhance teaching skills and methods) 16 | 2‐day BLS and emergency medicine teacher training program (content: “role of the teacher”, “needs of learners”, “providing feedback”, “structure of session”, “defining learning objectives”, “activating learners”, “teaching of skills”, “teaching with patients.) | Students taught by untrained teachers performed better in some domains. Teaching quality was rated significantly better by students of untrained teachers. |

ACLS indicates advanced cardiovascular life support; AED, automated external defibrillator; AHA, American Heart Association; ALS, advanced life support; ATP, Assessment Training Program; BLS, basic life support; CIC, Core Instructor Course; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; I/Cs, instructors/coordinators; and SPNRG, Spanish Pediatric and Neonatal Resuscitation Group.

Instructor Qualification/Training

There were 9 studies identified that were associated with new or modified courses to improve instructor qualification/training. 15 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 30

In 1 study, a modified instructor course for neonatal life support instructors contained lectures, instruction practice, and introduced scenarios developed by the instructor candidates themselves. Participants in this modified instructor course were more confident to teach neonatal CPR and to instruct resuscitation procedures and practice (>90% versus 50%–60%, P<0.001), as compared with instructor candidates who participated in training courses, in which more time was spent on text‐based lecturing and predesigned scenarios. 30 Another study compared an internet‐based instructor course to a classroom‐based instructor course and found no difference in posttest practical scores between the 2 groups of the instructor candidates, but candidates in the online group had significantly higher adjusted posttest scores. 18

There were 5 studies identified with a train‐the‐trainer (TTT) design for instructor courses, including 3 full‐length articles, 19 , 22 , 27 and 2 conference abstracts. 15 , 26 Two of them were in pediatric life support 19 , 26 and 3 of them in adult life support courses. 15 , 22 , 27 An abstract using a pre‐post study design for pediatric life support found that the knowledge score of the students was improved after the pediatric TTT training program of Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (overall mean score, pre versus post, 10.27 versus 12.48, P<0.001), and also showed retained improvement compared with pre‐course scores after 6 months (mean score: 11.81, P=0.001). 26 In the other pre‐post study on pediatric life support, both newly trained “trainers” (instructors) and their students showed improved comfort level in caring for sick children after the advanced pediatric life support TTT course. 19 In a pre‐post study on adult life support courses, students of the newly “trained trainers” in advanced life support (ALS) had significantly improved multiple choice questions score, and improved resuscitation skills. 27 In another study, the novice instructors hoped the training would improve their community’s response to emergencies and described a sense of belonging and duty to the community. 22 The remaining abstract reported a study where first‐year medical students were randomized to 2 types of BLS instructor training courses, “in‐service instructor training with certified TTT course” or “in‐service instructor training” only. 15 The participants in the former group scored significantly higher on the practical training of BLS (P=0.008) whereas the noncertified instructors (in‐service training only) performed better on parts of the theoretical BLS training (P=0.001). 15

An analysis of a system‐wide pediatric basic life support instructor training program was performed in one study 24 with 24 pediatric basic life support accredited instructor courses held over 21 years. The study revealed a pass rate of 98.9% in evaluation of the candidates in theoretical and practical tests, and the participants had overall positive ratings of the course.

In 1 study, a web‐based survey with a 29‐item competence importance performance scale identified the educational needs of BLS instructors, followed by a factor analysis. 23 The result showed that training priorities for novice instructors were communication with learners and instructors, learner motivation, educational design, and qualifications of instructors, whereas the priorities were checking equipment status and educational environment for the experienced instructors. 23

Assessment Tools

We identified 3 studies focusing on using assessment tools to improve the assessment skills and confidence of the instructors. 12 , 25 , 31 In 1 study, real‐time compression feedback devices were introduced to AHA‐certified CPR instructor/coordinators to determine chest compression quality and the accuracy. It was shown that all included CPR instructor/coordinators performed suboptimal chest compressions at baseline but improved after real‐time feedback, while assessment accuracy remained poor after using real‐time compression feedback. 12 In another study, BLS instructors regarded the use of sensor‐equipped manikins as useful to deliver BLS training. 25 In the other study, a motion capture camera was used to evaluate the ability of instructors to assess chest compressions and the recorded videos were also used to improve the self‐learning ability. 31 The result showed that novice instructors are able to improve the assessment of chest compression after self‐training, but remain below the level of experienced instructors. 31

Teaching Skills Enhancement

We identified 3 studies associated with new methods to enhance teaching skills. One randomized crossover study 14 compared the feedback sandwich technique with the learning conversation methods for instructors to deliver structured feedback in BLS training and found that the learning conversation was generally preferred by instructors over the sandwich feedback technique. No difference was seen in students’ pass rates regardless of the feedback methods (80.9% sandwich technique versus 77.2% learning conversation, P=0.29). 14 One randomized controlled trial compared debriefing with a standardized script by novice instructors with non‐scripted debriefing, and the standardized script used by novice instructors improved students’ acquisition of knowledge (multiple choice questions: mean [95% CI], 5.3% [4.1%–6.5%] versus 3.6% [2.3%–4.7%]; P=0.04) and the performance of team leader behavior (Behavioral Assessment Tool score: median [interquartile range], 16% [7.4%–28.5%] versus 8% [0.2%–31.6%]; P=0.03) during subsequent simulated cardiopulmonary arrests. 17 In the other study, all participating instructor candidates found that using videotaping and a subsequent critical view of a lecture was interesting, as they appreciated the possibility to compare their subjective impression with the objectivity recordings of teaching, thus improving their teaching skills. 21

Additional Courses for Instructors

Five studies were identified with interventions of additional courses or programs aiming to enhance specific skills of instructors.

In one study, 20 ALS instructors were randomized to an educational program with a session on how to identify common errors committed by team leaders during cardiac arrest simulations or to the control group of no intervention. The instructors in the educational program found more critical errors (1.70 versus 1.10, P=0.006), made more correct grade assignments (2.35 versus 2.0, P=0.026), and documented more errors that were emphasized in the educational program (3.61 versus 2.25, P=0.0001) compared with the control group. 20 Another RCT 16 compared whether an additional 2‐day BLS and emergency medicine teacher training program course for instructors influenced the outcomes of students. The study found that students taught by untrained teachers performed better in the structured clinical exam when compared with students taught by instructors who had completed the teacher training program. In addition, some domains of specific resuscitation skills and teaching quality was rated significantly better by students of untrained teachers. 16

In 2 studies, 28 , 29 an additional instructor program known as “Assessment Training Program” was held to improve the assessors’ decision making over equivocal situations in BLS and automated external defibrillator courses. Instructors of the Assessment Training Program were less prone to incorrectly failing candidates and were significantly more confident in their assessments. 28 , 29

In an instructor program for neonatal resuscitation composed of lectures, scenario development, video reviewing and debriefing, participating instructors improved their self‐perceived ability to conduct simulation, to recognize warning signs (eg, baby’s cry, expiratory grunting, reduced tone), and debriefing. 13

Discussion

Our review investigating faculty development approaches to improve instructional competence in life support courses found modified courses of instructor qualification or training, using assessment tools such as real‐time feedback and motion capture camera, new methods to enhance specific teaching skills of instructors, and adding another session after conventional instructor courses could improve teaching ability and self‐confidence of the instructors and course participants’ learning outcomes. Qualification of instructors is the foundation of delivering curricular knowledge and skills because it ensures that every instructor reaches a certain degree of teaching ability set by the governing organization. When this is achieved, learners can receive a comparable standard of training. However, different jurisdictions and areas have different cultures, environments and resources of learning and training. These differences create different needs. In addition, the instructor training program and content of the program will depend on who the learner is and the skill instructors need to teach. Therefore, it is impossible to use one‐size‐fit‐all model to prepare new instructors. Some organizations used generic instructor courses, whereas others opted to design their own specific ones. 3 , 30 , 32 , 33 For rural areas, train‐the‐trainer models were proposed. 26 , 27 Lack of training opportunities in the rural hospital setting was identified as a barrier to develop local expertise, and it was suggested that the TTT models may be effective in these specific contexts. These courses in different areas may not be comparable, as every area faces its own challenges. 3 , 34

A recent AHA scientific statement on resuscitation education suggested initial instructor training should include content on improving the key competencies of the instructors, including knowledge and skills in resuscitation education, incorporation of feedback devices, ability to effectively debrief, contextualization of content and enhancing teamwork training skills. 4 In our review, several interventions associated with the key competencies were identified. By using assisting tools, predefined debriefing script, scenario, or specific feedback method, novice instructors may increase confidence and have a positive reinforcement in teaching. 14 , 17 , 25 Apart from aiding devices and approaches for teaching, additional courses had been proposed to enhance specific ability for assessing, and 4 out of 5 included articles with additional training programs had a positive effect on their instructional competences. 13 , 20 , 28 , 29 As instructors, they should not only focus on the process of knowledge delivery but also be able to deal with various learner groups and make appropriate adaptation. Most of the current instructor courses as well as additional programs were delivered by workshops or seminars, whereas various approaches of training method and innovative educational strategies have been introduced in resuscitation provider training. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 In our review, 1 study found the effect of an internet‐based instructor course on the practical scores of the instructor candidates was no different from that of a classroom‐based instructor course. 18 It hints that the development of innovative instructor course is promising. Different instructional methods such as using high‐fidelity simulation or gamified learning may be integrated into instructors training programs as these candidates would be familiar with these materials and able to feel comfortable coaching during provider training. Also, with the implementation of the new educational paradigms such as self‐training with resuscitation quality improvement tools and e‐learning, the role of instructors will evolve. In the future, peers, parents, the internet, or novel learning platforms may serve as teachers in learning CPR. 39 , 40 , 41 Increased confidence of instructors might improve students’ learning and involvement during the training course. 42 Communication skills and learner motivation were regarded as part of important core competence of novice instructors in one descriptive survey. 23 However, it is difficult to quantify instructors’ ability of contextualizing teaching content and triggering learners’ motivation, and eventually increase learners’ willingness to perform CPR. Therefore, objective measurement of core competence of instructors needs to be determined as well as its assessment in the future.

Our scoping review did not identify any recertification programs, although continuous lifelong learning to retain the teaching and practicing skill is crucial for instructors. Some studies found that the instructors’ ability to perform and assess chest compression skill of learners was not as good as expected. 6 , 7 To some extent, the reason why some instructors had inadequate performance might be lack of solid and effective retraining or recertification programs. They might overestimate their assessment ability without reinforcement courses, as health providers usually have suboptimal accuracy of self‐assessment. 43 , 44 Instructors should also need to be well‐acquainted with updated knowledge and innovative teaching methods, and organizations should promote valid recertification program and support instructors becoming self‐directed, lifelong learners. 4

From the scoping review, several knowledge gaps in the literature were also identified: (1) the most appropriate life support instructor training strategy is not defined; (2) objective measurement of core competence of instructors needs to be determined as well as its assessment; (3) no study describes a strategy for an effective recertification or retraining program for life support course instructors; (4) it is unclear which feedback method or debriefing strategy is effective and how to teach the instructors in using a debriefing method successfully in life support instructor training; (5) it remains unknown whether continuous assessment and feedback of instructors from others, such as senior instructors or course directors, improve instructor competence and learning outcomes for the course participants; (6) the effect on patient outcome of instructor training was not addressed, thus highlighting a need for future research to establish links or associations between faculty development initiatives, learner outcomes, and patient outcomes.

Limitations

There were some limitations in our review. First, many studies only described how to implement regional instructor programs but did not report the outcomes of interest in our review. 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 Therefore, these studies were excluded from our review. Second, high heterogeneity among studies was found, and the result has insufficient evidence to prompt a new systematic review, thus highlighting significant gaps in the research evidence, especially for retraining and recertification program. Third, many of the studies were pre‐post studies and had an inherent large risk of bias. Finally, because of various cultures and resources among different areas, some faculty development approaches found in our review are not able to be applicable to all regions and should be modified to adapt different environment.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate faculty development for instructors remains an indispensable element to improve teaching outcomes for accredited life support courses. Different approaches, including instructor training courses, TTT programs, content to teach instructors how to use assessment tools, and additional training on how to integrate feedback devices into instruction, may optimize learning outcomes. It is encouraged that local organizations implement faculty development programs for their teaching staff of their accredited resuscitation courses. Future research should explore the best ways to strengthen and maintain instructor competency, and define the cost‐effectiveness of various different faculty development strategies.

Appendix

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation Education, Implementation and Teams (EIT) Task Force (Collaborators)

Janet Bray, Jan Breckwoldt, Jonathan P. Duff, Kathryn Eastwood, Elaine Gilfoyle, Yiqun Lin, Andrew Lockey, Tasuku Matsuyama, Kevin Nation, Catherine Patocka, Jeffrey L. Pellegrino, Sebastian Schnaubelt, Chih‐Wei Yang, Joyce Yeung, and Judith Finn.

Sources of Funding

The article was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 109‐2314‐B‐002‐155) and National Taiwan University Hospital (111‐X0031). This funding source had no role in the design of this study and had not any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Disclosures

This scoping review was part of the ILCOR continuous evidence evaluation process, which is guided by a rigorous conflict of interest policy (see www.ilcor.org). Robert Greif is ERC director of Guidelines and ILCOR, and ILCOR EIT task force Chair. Adam Cheng is ILCOR EIT task force Vice‐Chair. Janet Bray is Executive Member of the Australian Resuscitation Council and ILCOR BLS task force Chair. Andrew Lockey is President of Resuscitation Council UK. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance provided by Hsin‐Ping Chiu, the librarian of the National Taiwan University Medical Library for building up the searching strategy. The following ILCOR EIT Taskforce Members are acknowledged as collaborators on this scoping review: Janet Bray, Jan Breckwoldt, Jonathan P. Duff, Kathryn Eastwood, Elaine Gilfoyle, Yiqun Lin, Andrew Lockey, Tasuku Matsuyama, Kevin Nation, Catherine Patocka, Jeffrey L. Pellegrino, Sebastian Schnaubelt, Chih‐Wei Yang, Joyce Yeung, Judith Finn. We would like to thank Peter Morley (Chair ILCOR Science Advisory Committee) for his valuable contributions.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Ming‐Ju Hsieh, Email: erdrmjhsieh@gmail.com.

the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation Education, Implementation, Teams (EIT) Task Force:

Janet Bray, Jan Breckwoldt, Jonathan P Duff, Kathryn Eastwood, Elaine Gilfoyle, Yiqun Lin, Andrew Lockey, Tasuku Matsuyama, Kevin Nation, Catherine Patocka, Jeffrey L Pellegrino, Sebastian Schnaubelt, Chih‐Wei Yang, Joyce Yeung, and Judith Finn

References

- 1. Nolan JP, Maconochie I, Soar J, Olasveengen TM, Greif R, Wyckoff MH, Singletary EM, Aickin R, Berg KM, Mancini ME, et al. Executive summary 2020 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation. 2020;156:A1–A22. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Hoeyweghen RJ, Bossaert LL, Mullie A, Calle P, Martens P, Buylaert WA, Delooz H. Quality and efficiency of bystander CPR. Belgian cerebral resuscitation study group. Resuscitation. 1993;26:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(93)90162-j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greif R, Lockey A, Breckwoldt J, Carmona F, Conaghan P, Kuzovlev A, Pflanzl‐Knizacek L, Sari F, Shammet S, Scapigliati A, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: education for resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2021;161:388–407. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng A, Nadkarni VM, Mancini MB, Hunt EA, Sinz EH, Merchant RM, Donoghue A, Duff JP, Eppich W, Auerbach M, et al. Resuscitation education science: educational strategies to improve outcomes from cardiac arrest: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e82–e122. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Søreide E, Morrison L, Hillman K, Monsieurs K, Sunde K, Zideman D, Eisenberg M, Sterz F, Nadkarni VM, Soar J, et al. The formula for survival in resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen C, Bang C, Stærk M, Krogh K, Løfgren B. Certified basic life support instructors identify improper cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills poorly: instructor assessments versus resuscitation manikin data. Simul Healthc. 2019;14:281–286. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaye W, Rallis SF, Mancini ME, Linhares KC, Angell ML, Donovan DS, Zajano NC, Finger JA. The problem of poor retention of cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills may lie with the instructor, not the learner or the curriculum. Resuscitation. 1991;21:67–87. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90080-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wynne G, Marteau T, Evans TR. Instructors–a weak link in resuscitation training. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1992;26:372–373. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90052-E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stærk M, Vammen L, Andersen CF, Krogh K, Løfgren B. Basic life support skills can be improved among certified basic life support instructors. Resusc plus. 2021;6. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 1966;198:372–379. doi: 10.1001/jama.1966.03110170084023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al‐Rasheed RS, Devine J, Dunbar‐Viveiros JA, Jones MS, Dannecker M, Machan JT, Jay GD, Kobayashi L. Simulation intervention with manikin‐based objective metrics improves CPR instructor chest compression performance skills without improvement in chest compression assessment skills. Simul Healthc. 2013;8:242–252. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31828e716d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amin HJ, Aziz K, Halamek LP, Beran TN. Simulation‐based learning combined with debriefing: trainers satisfaction with a new approach to training the trainers to teach neonatal resuscitation. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:251. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baldwin LJL, Jones CM, Hulme J, Owen A. Use of the learning conversation improves instructor confidence in life support training: an open randomised controlled cross‐over trial comparing teaching feedback mechanisms. Resuscitation. 2015;96:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benthem Y, van de Pol E, van Goor H, Tan E. Effects of train the trainer course on the quality and feedback in a basis life support course for first year medical students – A randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2012;83:e103. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.08.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Breckwoldt J, Svensson J, Lingemann C, Gruber H. Does clinical teacher training always improve teaching effectiveness as opposed to no teacher training? A randomized controlled study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng A, Hunt EA, Donoghue A, Nelson‐McMillan K, Nishisaki A, LeFlore J, Eppich W, Moyer M, Brett‐Fleegler M, Kleinman M, et al. Examining pediatric resuscitation education using simulation and scripted debriefing: a multicenter randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:528–536. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Einspruch EL, Lembach J, Lynch B, Lee W, Harper R, Fleischman RJ. Basic life support instructor training: comparison of instructor‐led and self‐guided training. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2011;27:E4–E9. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e318217b421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feltes M, Becker J, McCall N, Mbanjumucyo G, Sivasankar S, Wang NE. Teaching how to teach in a train‐the‐trainer program. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:202–204. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-01014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldman SL, Thompson B, Whitcomb J. A new evaluation method for instructors of advanced cardiac life support. Resuscitation. 1986;14:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(86)90121-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herrero P, Baron M, Sojo J, Abad F, Lopez‐Messa J. Introducing a new training tool for instructors courses. Resuscitation. 2010;81:S106. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ismail A, AlRayyes M, Shatat M, Hafi RA, Heszlein‐Lossius H, Veronese G, Gilbert M. Medical students can be trained to be life‐saving first aid instructors for laypeople: a feasibility study from Gaza. Occupied palestinian territory. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34:604–609. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X19005004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim EJ, Roh YS. Competence‐based training needs assessment for basic life support instructors. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21:198–205. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López‐Herce J, Carrillo A, Urbano J, Manrique G, Mencía YS, y Grupo Madrileño de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos . Evaluation of the pediatric life support instructors courses. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:71. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02504-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nallamilli S, Alderman J, Ainsley K, Jones C, Hulme J. Introduction and perceived effectiveness of a novel skillmeter training programme for training in basic life support. Resuscitation. 2012;83:e40. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pollock L, Jefferis O, Dube Q, Kadewa R. 'I am the nurse who does io!': impact of a 'training of trainers' paediatric resuscitation training programme in Malawi. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:A75. doi: 10.1136/adc.2011.212563.175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rajapakse BN, Neeman T, Dawson AH. The effectiveness of a 'train the trainer' model of resuscitation education for rural peripheral hospital doctors in Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thorne CJ, Jones CM, Coffin NJ, Hulme J, Owen A. Structured training in assessment increases confidence amongst basic life support instructors. Resuscitation. 2015;93:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thorne CJ, Jones CM, Harvey P, Hulme J, Owen A. An analysis of the introduction and efficacy of a novel training programme for ERC basic life support assessors. Resuscitation. 2013;84:526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wada M, Tamura M. Training of neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructors. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:629–632. doi: 10.1111/ped.12683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamahata Y, Ohta B, Irie J, Takebe K. Instructors must be trained the ability to evaluate chest compressions. Resuscitation. 2014;85:S49. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.03.125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finn JC, Bhanji F, Lockey A, Monsieurs K, Frengley R, Iwami T, Lang E, Ma M‐M, Mancini ME, McNeil MA, et al. Part 8: education, implementation, and teams: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation. 2015;95:e203–e224. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. López‐Herce J, Carrillo A, Rodriguez A, Calvo C, Delgado MA, Tormo C. Paediatric life support instructors courses in Spain. Resuscitation. 1999;41:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheng A, Magid DJ, Auerbach M, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, Blewer AL, Dainty KN, Diederich E, Lin Y, Leary M, et al. Part 6: resuscitation education science: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S551–S579. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Balian S, McGovern SK, Abella BS, Blewer AL, Leary M. Feasibility of an augmented reality cardiopulmonary resuscitation training system for health care providers. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02205. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boada I, Rodriguez‐Benitez A, Garcia‐Gonzalez JM, Olivet J, Carreras V, Sbert M. Using a serious game to complement CPR instruction in a nurse faculty. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakanishi T, Goto T, Kobuchi T, Kimura T, Hayashi H, Tokuda Y. The effects of flipped learning for bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation on undergraduate medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:430–436. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5a2b.ae56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodgers DL, Securro S Jr, Pauley RD. The effect of high‐fidelity simulation on educational outcomes in an advanced cardiovascular life support course. Simul Healthc. 2009;4:200–206. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181b1b877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beck S, Issleib M, Daubmann A, Zöllner C. Peer education for BLS‐training in schools? Results of a randomized‐controlled, noninferiority trial. Resuscitation. 2015;94:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moule P, Albarran JW, Bessant E, Brownfield C, Pollock J. A non‐randomized comparison of e‐learning and classroom delivery of basic life support with automated external defibrillator use: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14:427–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Panchal AR, Norton G, Gibbons E, Buehler J, Kurz MC. Low dose‐ high frequency, case based psychomotor CPR training improves compression fraction for patients with in‐hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2020;146:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harder BN, Ross CJ, Paul P. Instructor comfort level in high‐fidelity simulation. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:1242–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blanch‐Hartigan D. Medical students' self‐assessment of performance: results from three meta‐analyses. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self‐assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anantharaman V. The National Resuscitation Council, Singapore, and 34 years of resuscitation training: 1983 to 2017. Singapore Med J. 2017;58:418–423. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2017069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boo NY, Pong KM. Neonatal resuscitation training program in Malaysia: results of the first 2 years. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:118–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Couper ID, Thurley JD, Hugo JFM. The neonatal resuscitation training project in rural South Africa. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5:459. doi: 10.22605/RRH459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. González E, Sánchez M, Zeballos G, Aguayo J, Burón E, Salguero E. Neonatal resuscitation instructors courses by Spanish society of neonatology. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:62. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.679162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hosono S, Tamura M, Isayama T, Sugiura T, Kusakawa I, Ibara S, Ishikawa G, Okuda M, Sekizawa A, Tanaka H, et al. Neonatal resuscitation committee Japan society of perinatal neonatal medicine. Neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation project in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2019;61:634–640. doi: 10.1111/ped.13897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kang S, Seo H, Ho BD, Nguyen PTA. Implementation of a sustainable training system for emergency in Vietnam. Front Public Health. 2018;6:4. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. López‐Herce J, Matamoros MM, Moya L, Almonte E, Coronel D, Urbano J, Carrillo Á, del Castillo J, Mencía S, Moral R, et al. Red de Estudio Iberoamericano de estudio de la parada cardiorrespiratoria en la infancia (RIBEPCI) . Paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation training program in Latin‐America: the RIBEPCI experience. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:161. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1005-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seraj MA, Harvey PJ. 15 years of experience with cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a critical analysis. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1999;14:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smith MK, Ross C. Teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a developing country: using Nicaragua as a model. Crit Care Nurs Q. 1997;20:15–21. doi: 10.1097/00002727-199708000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Strömsöe A, Andersson B, Ekström L, Herlitz J, Axelsson A, Göransson KE, Svensson L, Holmberg S. Education in cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Sweden and its clinical consequences. Resuscitation. 2010;81:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1