Abstract

Pyoverdine isoelectric focusing analysis and pyoverdine-mediated iron uptake were used as siderotyping methods to analyze a collection of 57 northern and central European isolates of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans.” The bacteria, isolated from cultivated Agaricus bisporus or Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom sporophores presenting brown blotch disease symptoms, were identified according to the white line test (W. C. Wong and T. F. Preece, J. Appl. Bacteriol. 47:401–407, 1979) and their pathogenicity towards A. bisporus and were grouped into siderovars according to the type of pyoverdine they produced. Seventeen P. tolaasii isolates were recognized, which divided into two siderovars, with the first one containing reference strains and isolates of various geographical origins while the second one contained Finnish isolates exclusively. The 40 “P. reactans” isolates divided into eight siderovars. Pyoverdine isoelectric focusing profiles and cross-uptake studies demonstrated an identity for some “P. reactans” isolates, with reference strains belonging to the P. fluorescens biovars II, III, or V. Thus, the easy and rapid methods of siderotyping proved to be reliable by supporting and strengthening previous taxonomical data. Moreover, two potentially novel pyoverdines characterizing one P. tolaasii siderovar and one “P. reactans” siderovar were found.

Pseudomonas tolaasii, the causal agent of brown blotch disease on cultivated mushrooms, is responsible of significant crop losses in mushroom growing houses. The pathogen has been reported on Agaricus bisporus, Agaricus bitorquis, Agaricus campestris, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Pleurotus eryngii (2, 35). It has been classified in RNA-DNA homology group I (31) and, more precisely, as closely related to biovar V of Pseudomonas fluorescens (10, 17). However, it is easily distinguished from P. fluorescens strains or other fluorescent pseudomonads by two main features, which are (i) the pathogenicity to mushrooms (13, 30) and (ii) the white line reaction (37). The white line reaction is the result of a specific interaction between two diffusible lipodepsipeptides, the tolaasin toxin produced by P. tolaasii (3, 7, 28, 29, 33) and the so-called white line inducing principle (26), which is produced by some pseudomonads associated with mushrooms and referred to as “Pseudomonas reactans” (37). “P. reactans” has been considered a strictly saprophytic bacterial component in the microflora of the cultivated mushrooms (32), and the white line inducing principle has effectively been described as having no pathogenic properties on mushroom tissues (34). However, some light pathogenic symptoms have been recently observed for some of these strains (36). Taxonomy studies on “P. reactans” isolates already revealed a great heterogeneity as observed from DNA-DNA hybridizations (17) and from phenotypic characterizations which, moreover, demonstrated that some of them belonged to P. fluorescens biovar III and that some others belonged to P. fluorescens biovar V (36). On the contrary, P. tolaasii strains are considered phenotypically and genomically homogeneous (17, 36), although presenting phenotypic variations: old colonies develop sectors which correspond to phenotypic variants described as nonpathogenic and white line negative (8, 18).

Siderotyping (short for siderophore typing) has been recently proposed as a rapid and efficient bacterial typing method for the discrimination of fluorescent pseudomonad strains (24). It is mainly based on the recognition of the different types of pyoverdine (PVD), which is the typical fluorescent pigment and powerful siderophore of the fluorescent Pseudomonas (11, 22). More than 30 structures of PVDs, differing mainly in their peptide chain, have been so far described (4). These differences in structure for PVD have a tremendous effect on the biological activity of the siderophore since, as a general rule, a fluorescent Pseudomonas recognizes exclusively the ferric complex of its own PVD (19, 23). The combination of several siderotyping methods, such as PVD isoelectric focusing (PVD-IEF) and the PVD-mediated iron uptake method, was shown to be very effective for the identification of well-defined P. aeruginosa strains into three different groups, or siderovars, according to the type of PVD produced by the strains. The use of the second method, PVD-mediated iron uptake, was particularly necessary for analyzing strains having a defect in PVD synthesis but still expressing the ferripyoverdine outer membrane receptor (24). Siderotyping also proved to be an interesting way to phenotypically discriminate the two recently proposed new species, Pseudomonas brassicacearum and Pseudomonas thivervalensis (1). Moreover, IEF analysis allowed a rapid screening of numerous fluorescent Pseudomonas and permitted a rapid detection of structurally original PVDs. Thus, the method has proved to be an interesting preceeding step before chemical characterization of new PVDs (5, 16, 25).

The goal of the present study was to analyze through siderotyping a collection of natural isolates belonging to the P. tolaasii species or to the taxonomically heterogeneous “P. reactans” group for testing the discriminative power and usefulness of the method in bacterial identification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Most of the bacterial strains described in the present study were isolated over a period of 18 months from brown blotch disease-affected A. bisporus or P. ostreatus mushrooms, kindly supplied by different northern and central European farms. Isolates are listed in Table 1 as well as their geographical origin. Strains whose designations begin with PS were collected from A. bisporus mushrooms; strains whose designations begin with PL were collected from P. ostreatus mushrooms. One strain, PS22.2, was isolated from a wild Agaricus sp. mushroom sporophore. Strain PS8.14V was isolated as a phenotypic variant which spontaneously arose after streaking the wild-type strain PS8.14 on an agar plate. Reference strains were P. tolaasii LMG 2342T (also known as NCPPB 2192T and ATCC 33618T), P. tolaasii LMG 6641, and “P. reactans” LMG 5329, obtained from the Belgian Collection, Ghent. P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692, P. fluorescens ATCC 13525, and P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 were from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va. Pseudomonas monteilii CFML 90.54 (12) and other strains of the Collection de la Faculté de Médecine de Lille (CFML), P. fluorescens 51W (25), P. fluorescens 12 (15), and P. fluorescens 18.1 (6) were kindly provided by D. Izard (Université de Lille 2, Lille, France), S. Shivaji (Center of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India), H. Budzikiewicz (Universität zu Köln, Cologne, Germany), and M. Champomier-Verges (INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France), respectively.

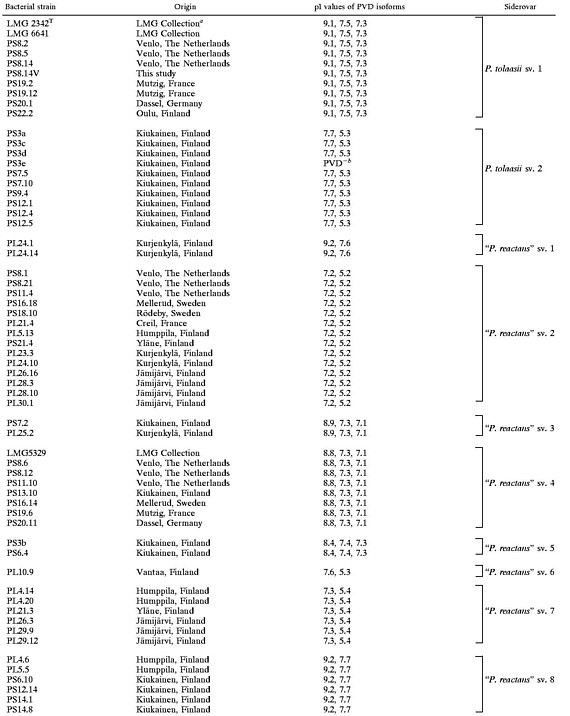

TABLE 1.

pI values of PVDs of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” strains and grouping of the strains into siderovars

|

LMG Collection, Laboratory of Microbiology, Ghent, Belgium.

The PVD-deficient strain PS7.5 was grouped in P. tolaasii sv. 2 according to its PVD-mediated iron uptake specificity (see Table 2).

Isolation and growth conditions.

Blotched outer layer tissues of affected mushrooms were recovered and suspended with vigourous shaking in sterile water. Fifty microliters of an appropriate serial dilution was spread on King's B agar medium (Difco Laboratories), and one of each of the phenotypically different colonies developing a fluorescent halo after 48 h of incubation at 25°C was further purified by streaking it on the same medium. Routine growth was in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or King's B liquid medium. Strains were preserved by mixing overnight LB culture with 50% glycerol (1:1, vol/vol) and storage at −80°C. Iron-poor liquid growth medium was the Casamino Acid (CAA) medium, consisting of (per liter) 5 g of low-iron Bacto Casamino Acid (Difco), 1.54 g of K2HPO4 · 3H2O, and 0.25 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, and was mainly used for PVD-IEF analysis and PVD purification through the Amberlite XAD-4 (XAD) procedure as described previously (25). Another iron-deficient medium used for PVD-mediated iron incorporation experiments was the synthetic succinate medium (21). Media were distributed in capped test tubes (180 by 18 mm; 7.5 ml) or 100-ml flasks containing 40 ml of medium or in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 500 ml of medium. Light inoculations were done with sterile wood sticks dipped in an overnight preculture in the same medium, and the cultures were incubated on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 25°C.

White line and pathogenicity tests.

The white line test was performed according to the method of Wong and Preece (37), using the collection strains P. tolaasii LMG 2342T or P. tolaasii LMG 6641 and “P. reactans” LMG 5329 as reference strains. On King's B agar, bacterial patches of strains to be tested (3 μl of 1/10-diluted overnight LB cultures) were placed at a distance of 1 cm from each other, on a line located between lines of P. tolaasii LMG 2342T (or P. tolaasii LMG 6641) and “P. reactans” LMG 5329 patches. The appearance of the precipitate forming the white line in between patches was examined after 72 h of incubation at 25°C. Pathogenicity tests were performed as a modification of the method described by Olivier et al. (30): 20 μl of bacterial suspensions at 108 CFU per ml or 20 μl of sterile water as control was deposited at the surface of A. bisporus mushroom caps maintained at 16°C in a saturated-humidity chamber (27). Brown discoloration around the inoculation spot within 72 h was considered a positive reaction. Healthy mushrooms for this test were provided by Mykora Ltd., Kiukainen, Finland.

IEF analysis of PVDs.

The model 111 mini-IEF cell from Bio-Rad was used. Casting of the gels (5% polyacrylamide containing 2% Bio-Lyte 3/10 ampholytes) and electric focusing were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. One-microliter samples of PVDs (aqueous XAD-purified solutions [6.5 mg/ml]), or of culture supernatants (40-h CAA-grown culture supernatant concentrated 20-fold by lyophylization) were used. PVD bands in the gel were visualized under UV light at 365 nm and photographed just after focusing. Their respective isoelectric pH values (pI values) were determined according to a calibration curve constructed by slicing the electrophoresed gel into 0.5-cm bands, which were incubated in 2 ml of 10 mM KCl during 30 min before measuring the pH (Beckman pHmeter equipped with a minielectrode). Repeated experiments on different gels with different ampholine commercial samples demonstrated a standard deviation of 0.1 for pI values above pH 6.0 or 0.2 for pI values below pH 6.0. Therefore, the expected identity in PVD-IEF profiles was controlled by performing a comigration of the concerned PVDs on the same gel.

PVD-mediated iron uptake.

Bacterial cells from 40-h cultures in succinate medium were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with distilled water, and resuspended at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.33 in an incubation medium made of succinate medium with the nitrogen source omitted. Label mix containing 59Fe-PVD complex consisted of 5 μl of the commercial 59Fe3+ solution (iron chloride in 0.1 M HCl; specific activity, 110 to 925 MBq/mg of iron; Amersham) diluted first with 100 μl of water and then mixed with 10 μl of a 6.5-mg/ml XAD-purified PVD solution. The final volume of the label mix was adjusted after 30 min of incubation at room temperature to 1 ml with incubation medium. Thirty five structurally different PVDs, listed in the legend of Fig. 2, were used. Bacterial suspension (1.8 ml) was mixed at time zero with 0.2 ml of label mix. After 20 min of incubation with gentle shaking in a water bath at 25°C, 1 ml of each bacterial suspension was rapidly filtered through a Whatman nitrocellulose filter (0.45-μm pore size), and the filters were washed twice with 2 ml of fresh incubation medium. Each filter was then wrapped in aluminium foil and radioactivity counts were determined in a Gamma 4000 Beckman counter. The remaining 1-ml bacterial suspension was directly counted to determine the total amount of radioactivity present in the assay. Control assays without bacteria were performed to verify the complete solubility of labeled iron through PVD complexation. Uptake data expressed in the tables or figures are average values of at least duplicate independent experiments.

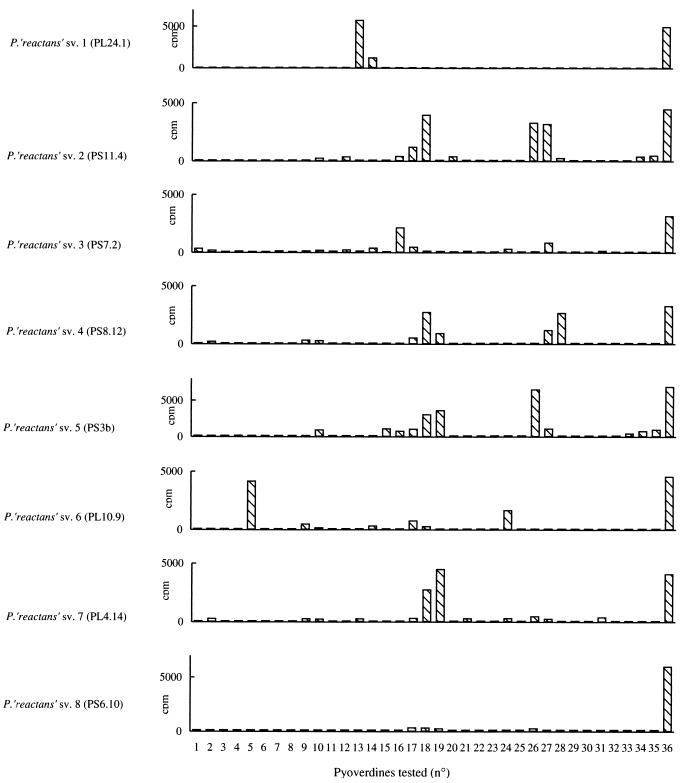

FIG. 2.

Heterologous PVD-mediated 59Fe incorporation by “P. reactans” strains belonging to the eight siderovars. Ordinate values correspond to 59Fe radioactivity expressed in counts per minute as measured after 20 min of incubation (see Materials and Methods). Abscissa numbers 1 to 36 correspond to the structurally different PVDs tested, originating from the following bacterial strains (PVD numbers are given in parentheses): Pseudomonas strain E8 (1), P. syringae ATCC 19310 (2), P. fluorescens 9AW (3), P. putida ATCC 12633 (4), P. fluorescens 51W (5), P. aeruginosa Pa6 (6), P. fluorescens CCM 2798 (7), P. fluorescens CHA0 (8), P. tolaasii NCPPB 2192 (9), P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (10), P. fluorescens ii (11), P. fluorescens SB8.3 (12), P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 (13), P. fluorescens 1.3 (14), Pseudomonas strain 267 (15), P. fluorescens ATCC 13525 (16), P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692 (17), P. fluorescens strain 18.1 (18), P. fluorescens 12 (19), P. fluorescens CFBP 2392 (20), Pseudomonas strain L1 (21), Pseudomonas sp. strain ATCC 15915 (22), P. putida WCS358 (23), P. monteilii CFML 90-54 (24), “P. mosselii” CFML 90-77 (25), P. rhodesiae CFML 92-104 (26), P. veronii CFML 92-124 (27), Pseudomonas sp. strain CFML 90-33 (28), Pseudomonas sp. strain CFML 90-51 (29), Pseudomonas sp. strain CFML 90-52 (30), Pseudomonas sp. strain CFML 95-307 (31), Pseudomonas sp. strain 2908 (32), Pseudomonas sp. strain A214 (33), P. fluorescens PL7 (34), P. fluorescens PL8 (35), and the PVD synthesized by the strain under investigation (36). The counts per minute were corrected for the blank values obtained in assays without bacteria.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Raising of the collection of natural isolates of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” through white line and pathogenicity tests.

Numerous studies have ascertained that the white line test together with a pathogenicity test (37) is an accurate screening method for the isolation and recognition of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” strains (14, 17, 20, 34, 36–38). Thus, these methods were used to isolate a collection of such bacteria from blotched A. bisporus or P. ostreatus mushroom sporophores provided by 14 farms located in Finland, France, Germany, The Netherlands, and Sweden (Table 1).

Seventeen P. tolaasii strains were isolated from eight samples of blotched A. bisporus sporophores originating from Finland, France, Germany, and The Netherlands. None was detected on P. ostreatus during the course of this study. The isolates were retained based on a positive white line test response to “P. reactans” LMG 5329 (37). Moreover, all P. tolaasii isolates gave a typical brown blotch symptom when the pathogenicity test (27, 30) was performed on healthy A. bisporus sporophores with the exception of strain PS8.14V. This strain, isolated as a phenotypic variant of P. tolaasii PS8.14, did not react in the white line test and was nonpathogenic (results not shown), in accordance with the literature (8, 18).

Forty “P. reactans” isolates were selected after they responded positively to P. tolaasii LMG 2342T in the white line test. They were isolated from A. bisporus as well as from P. ostreatus mushrooms. Most of the isolates, when subjected to the pathogenicity test, gave negative responses. A few of them, however (for example, strain PS7.2), induced a weak discoloration when tested on A. bisporus sporophores (data not shown).

Characterization of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” PVDs by IEF.

Electrophoresis of PVDs on ampholine-containing polyacrylamide gel (PVD-IEF) results in the separation of the different molecular forms of PVD present in the supernatant of an iron-starved fluorescent pseudomonad culture. Thus, the method allows an easy discrimination between strains producing structurally different PVDs (24). Most often, for a given strain, these different molecular forms are succinic, succinamide, malate, maleide, or α-ketoglutarate forms (isoforms) of an otherwise identical molecule (4). PVD isoforms appear on the electrophoresed IEF gel exposed to UV light as fluorescent bands with various intensities, depending on the respective concentrations they reached in the culture supernatant during the bacterial growth. Each band could be characterized by the pH value measured at the place on the gel where the PVD isoform localizes (pI).

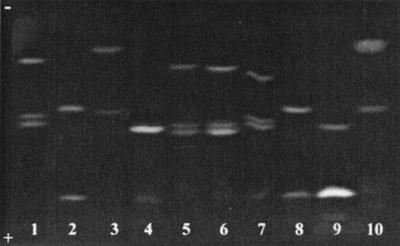

As shown in Fig 1, 10 different PVD-IEF patterns were observed upon analyzing the culture supernatants of the P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” strains grown under iron-deficient conditions (CAA medium). Strains developing an identical PVD-IEF profile were grouped together to form a so-called siderovar. Table 1 indicates the pI values, obtained for all the PVD-producing natural isolates and for the three P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” LMG reference strains, and their grouping into 10 siderovars.

FIG. 1.

IEF profiles of PVDs synthesized by P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” strains representatives of the 10 siderovars. Lane 1, P. tolaasii LMG 2342 (sv. 1); lane 2, P. tolaasii PS3a (sv. 2); lane 3, “P. reactans” PL24.1(sv.1); lane 4, “P. reactans” PS11.4 (sv. 2); lane 5, “P. reactans” PS7.2 (sv. 3); lane 6, “P. reactans” PS8.12 (sv. 4); lane 7, “P. reactans” PS3b (sv. 5); lane 8, “P. reactans” PL10.9 (sv. 6); lane 9, “P. reactans” PL4.14 (sv. 7); lane 10, “P. reactans” PS6.10 (sv. 8).

P. tolaasii strains subdivided into two siderovars (Table 1; Fig. 1). P. tolaasii siderovar (sv.) 1 contains the reference strains LMG 6641 and LMG 2342T, as well as six natural isolates, all isolated from A. bisporus sporophores cultivated in three different countries (Table 1). The PVD-IEF profile of these strains, as illustrated in Fig. 1, lane 1, for strain LMG 2342T, consisted of three well-separated bands which very likely should correspond to the three recognized isoforms (succinamide, succinate, and α-ketoglutaric acid forms) of the structurally known PVD of P. tolaasii NCPPB 2192T (LMG 2342T) (9). The same P. tolaasii sv. 1 PVD-IEF pattern was also observed for the Finnish strain PS22.2, isolated from a wild Agaricus sp. mushroom sporophore, and for strain PS8.14V, a nonpathogenic variant which, thus, was confirmed as belonging to the same siderovar as the corresponding wild-type organism PS8.14.

Another PVD-IEF pattern characterized the nine fluorescent P. tolaasii strains representing P. tolaasii sv. 2 (Table 1; Fig. 1). These strains originated exclusively from A. bisporus sporophores harvested from Finnish mushroom farms located in Kiukainen area. Another P. tolaasii isolate of identical origin, PS7.5, was not typeable by the IEF method because of its inability to produce PVD under all three tested iron-starved growth conditions (CAA medium, succinate medium, or liquid King's medium).

The 40 “P. reactans” strains presented eight different PVD-IEF profiles, most of which were well differentiated from the PVD-IEF profiles of the two P. tolaasii siderovars (Fig. 1). Thus, the “P. reactans” strains were grouped into eight siderovars (“P. reactans” sv. 1 to “P. reactans” sv. 8) (Table 1). Fourteen strains, isolated from A. bisporus (six isolates) or P. ostreatus (eight isolates) originating from nine different geographical areas (Table 1), formed a major siderovar (“P. reactans” sv. 2) (Table 1). “P. reactans” sv. 1 (two strains) and “P. reactans” sv. 8 (six strains) were each characterized by a similar although distinguishable PVD-IEF pattern (Table 1), with the band at pI 9.2 systematically more pronounced for the strains belonging to the “P. reactans” sv. 8 (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 10). The six isolates of “P. reactans” sv. 7 were characterized by a very pronounced PVD band at pI 5.4, which allowed us to easily distinguish them from the “P. reactans” sv. 2 strains (Fig 1, lanes 9 and 4, respectively). The PVD-IEF patterns of the strains belonging to “P. reactans” sv. 3 and “P. reactans” sv. 4 were very similar (Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6) and required a comigration of the respective PVDs to ascertain their classification. Strain PL10.9 showed a PVD-IEF pattern very close to the PVD-IEF pattern of P. tolaasii sv. 2 strains (Fig. 1, lanes 8 and 2, respectively) but unique among “P. reactans” strains. Thus, it was recognized as the unique representative of “P. reactans” sv. 6.

Discrimination of P. tolaasii and “P. reactans” siderovars by PVD-mediated iron uptake.

In order to ascertain the classification reached by PVD-IEF, all the strains were analyzed for their capacity to incorporate iron under the form of a PVD-iron complex. The PVD produced by one representative of each siderovar was purified by the XAD filtration procedure (4) and tested for its capacity to mediate 59Fe iron uptake in each of the strains belonging to the corresponding siderovar. Table 2 reports that the PVD of strain LMG 2342T (P. tolaasii sv. 1) efficiently mediated iron incorporation in all the strains belonging to P. tolaasii sv. 1. Conversely, the PVD of strain PS3a (P. tolaasii sv. 2) was well recognized by the strains belonging to P. tolaasii sv. 2. The PVD of P. tolaasii PS3a was also recognized by strain PS7.5 (a PVD-deficient isolate) (Table 2). Accordingly, this strain could then be classified in siderovar 2. Table 2 indicates also that the P. tolaasii PVDs should be considered siderovar specific since none of the strains was able to use both compounds efficiently as an iron transporter.

TABLE 2.

PVD-mediate iron incorporation in P. tolaasii strains

| Strain | Siderovar | Iron incorporationa as mediated by PVD of strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LMG 2342 (sv. 1) | PS3a (sv. 2) | ||

| LMG 2342 | 1 | 481 | 27 |

| LMG 6641 | 1 | 287 | 19 |

| PS8.2 | 1 | 404 | 18 |

| PS8.14 | 1 | 396 | 23 |

| PS19.2 | 1 | 177 | 15 |

| PS19.12 | 1 | 169 | 18 |

| PS20.1 | 1 | 107 | 14 |

| PS3a | 2 | 0 | 176 |

| PS3c | 2 | 11 | 198 |

| PS3d | 2 | 0 | 119 |

| PS3e | 2 | 20 | 144 |

| PS7.5 | 2 | 15 | 182 |

| PS7.10 | 2 | 14 | 201 |

| PS9.4 | 2 | 0 | 128 |

| PS12.1 | 2 | 6 | 169 |

| PS12.4 | 2 | 3 | 241 |

| PS12.5 | 2 | 3 | 215 |

Expressed in picomoles of 59Fe incorporated within a 20-min incubation per milligram (dry weight) of cells. Values of <30 are not significant.

Intrasiderovar efficiency was also conclusive for the PVDs produced by the “P. reactans” strains previously grouped into eight siderovars (Table 1). Each strain belonging to a defined siderovar, according to its IEF profile, was able to use the corresponding siderovar-specific PVD, at an efficiency identical or very close to that of the PVD producer strain. Parts of these data are shown in Table 3 for the two strains belonging to “P. reactans” sv. 1 and for the six strains of “P. reactans” sv. 7. Unlike P. tolaasii, some cross-recognitions between different “P. reactans” siderovars and their respective PVDs were observed, but the highest iron incorporation was always reached in the homologous system. This was particularly evident for the four siderovars “P. reactans” sv. 2 to 5 (Table 4). As an example, strain PS20.11 of “P. reactans” sv. 4 was able to use the PVD of strain PL5.13 (“P. reactans” sv. 2) at half efficiency compared to its own PVD. The reciprocity of cross-recognition was effective for this couple of strains but was not a general rule, as illustrated in Table 4 for strains PL5.13 and PS3b or strains PL10.9 and PL4.14.

TABLE 3.

Heterologous PVD-mediated iron incorporation in “P. reactans” isolates and some reference strains

| Strain | Iron incorporationa as mediated by PVD of strain:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL24.1 (sv. 1) | P. fluorescens 17400 | PL10.9 (sv. 6) | P. fluorescens 51W | P. monteilii CFLM 90.54 | PL4.14 (sv. 7) | P. fluorescens 12 | P. fluorescens 18.1 | PS7.2 (sv. 3) | P. fluorescens 13525 | |

| PL24.1 (“P. reactans” sv. 1) | 100 | 96 | ||||||||

| PL24.14 (“P. reactans” sv. 1) | 105 | 97 | ||||||||

| P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 | 97 | 100 | ||||||||

| PL10.9 (“P. reactans” sv. 6) | 100 | 102 | 18 | |||||||

| P. fluorescens 51W | 108 | 100 | 18 | |||||||

| P. monteilii CFLM 90.54 | 4 | 1 | 100 | |||||||

| PL4.14 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 100 | 93 | 68 | |||||||

| PL4.20 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 99 | 90 | 60 | |||||||

| PL21.3 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 102 | 88 | 65 | |||||||

| PL26.3 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 103 | 86 | 67 | |||||||

| PL29.9 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 97 | 92 | 62 | |||||||

| PL29.12 (“P. reactans” sv. 7) | 96 | 85 | 59 | |||||||

| P. fluorescens 12 | 106 | 100 | 67 | |||||||

| P. fluorescens 18.1 | 21 | 22 | 100 | |||||||

| PS7.2 (“P. reactans” sv. 3) | 100 | 73 | ||||||||

| P. fluorescens ATCC 13525 | 75 | 100 | ||||||||

Expressed as a percentage of the value in the homologous system.

TABLE 4.

PVD-mediated iron incorporation in “P. reactans” strains

| “P. reactans” strain | Siderovar | Iron uptakea as mediated by the PVD of “P. reactans” strain:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL24.1 sv. 1 | PL5.13 sv. 2 | PS7.2 sv. 3 | PS20.11 sv. 4 | PS3b sv. 6 | PL10.9 sv. 6 | PL4.14 sv. 7 | PS6.10 sv. 8 | ||

| PL24.1 | 1 | 223 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| PL5.13 | 2 | 7 | 192 | 76 | 141 | 159 | 7 | 0 | 3 |

| PS7.2 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 554 | 124 | 125 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| PS20.11 | 4 | 0 | 172 | 22 | 322 | 10 | 0 | 80 | 5 |

| PS3b | 5 | 3 | 0 | 89 | 186 | 618 | 0 | 158 | 4 |

| PL10.9 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 13 | 247 | 298 | 575 | 205 | 6 |

| PL4.14 | 7 | 8 | 127 | 0 | 278 | 3 | 0 | 561 | 2 |

| PS6.10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 29 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 519 |

Expressed in picomoles of 59Fe incorporated in 20 min by 1 mg of cells (dry weight). Values of <30 are not significant.

On the contrary, a high specificity of recognition characterized the strains and the PVDs synthesized by isolates belonging to “P. reactans” sv. 1 and “P. reactans” sv. 8, for which only the homologous system was efficient in iron incorporation. Even though the PVD of strain PL10.9 (“P. reactans” sv. 6) was highly specific to its producing strain, the strain was also able to use, at a lower efficiency, however, the PVDs of “P. reactans” sv. 4, 5, and 7 (Table 4). Moreover, strain PL10.9 was unable to use the PVD of the P. tolaasii sv. 2 strains, and conversely, no uptake was detected for strain PS3a (P. tolaasii sv. 2) when tested with PVD(PL10.9) (data not shown). Although they have similar IEF patterns (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 8), these two PVDs should, therefore, be different in structure.

Altogether, the data reached by PVD-mediated iron uptake studies well confirmed the siderovar grouping first reached by PVD-IEF. IEF of PVDs appears, thus, to be the method of choice for siderotyping fluorescent pseudomonads, especially because of its rapidity, allowing also the simultaneous analysis of as many as 15 strains in one run. However, the uptake method was necessary for the siderotyping of strain PS7.5, which was able to incorporate iron through PVD but presented a defect in PVD biosynthesis and, therefore, was nontypeable by IEF. Furthermore, the method is required for discriminating strains having similar IEF patterns and, therefore, should be used to assess the grouping of strains as reached by PVD-IEF.

Attempts for taxonomical recognition of “P. reactans” strains through siderotyping.

Siderotyping, by discriminating eight siderovars among the “P. reactans” strains, already supported the taxonomic diversity recognized for such bacteria by previous investigations (17, 36) which, furthermore, identified some “P. reactans” strains as being closely related to P. fluorescens biovar III and P. fluorescens biovar V (36). Therefore, we tested one strain of each “P. reactans” siderovar for 59Fe iron incorporation mediated by a collection of PVDs of different bacterial origin. The 35 compounds tested, referred to as the heterologous PVDs, have been obtained from strains representative of a wide variety of fluorescent Pseudomonas species—among them, strains belonging to P. fluorescens biovar III or biovar V—and were characterized each by a particular peptidic structure (most structures of these 35 PVDs have been already published [see references 4 and 23 for a compilation], while some others are presently under investigation).

As shown in Fig. 2, each “P. reactans” siderovar type strain had a specific pattern of heterologous PVD recognition. Strain PS6.10, the representative of “P. reactans” sv. 8, presented the most restricted pattern since none of the 35 heterologous PVDs was recognized. Strain PL24.1 (“P. reactans” sv. 1) and strain PL10.9 (“P. reactans” sv. 6) each well recognized a single heterologous PVD, respectively, the PVD of P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 (Fig. 2 [PVD 13]) and the PVD of P. fluorescens 51W (Fig. 2 [PVD 5]). These two PVDs were not recognized by any of the other “P. reactans” siderovars. The representatives of siderovars 2 to 5 and siderovar 7 were able to recognize two or more of the PVDs produced by the following Pseudomonas strains (Fig. 2) P. fluorescens ATCC 13525 (PVD 16), P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692 (PVD 17), P. fluorescens 18.1 (PVD 18), P. fluorescens 12 (PVD 19), P. rhodesiae CFML 92.104 (PVD 26), P. veronii CFML 92.124 (PVD 27), and Pseudomonas sp. CFML 90.33 (PVD 28). In some cases, the efficiencies of iron uptake mediated by these heterologous PVDs were close, if not identical, to the one reached by the homologous PVD, suggesting a structural identity in between those of the PVDs of concern, i.e., the PVDs of P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 and “P. reactans” PL24.1 (sv. 1), P. fluorescens 18.1 and “P. reactans” PS11.4 (sv. 2), P. fluorescens 51W and “P. reactans” PL10.9 (sv. 6), or P. fluorescens 12 and “P. reactans” PL4.14 (sv. 7) (Fig. 2). Therefore, we analyzed the capacities of some of the reference strains to incorporate the corresponding “P. reactans” PVDs. IEF patterns of the PVDs of concern were compared as well. As shown in Table 3, P. fluorescens ATCC 17400 recognized the PVD of “P. reactans” PL24.1 (sv. 1) as well as its own PVD. P. fluorescens 51W and “P. reactans” PL10.9 (sv. 6) both reacted similarly. On the contrary, P. monteilii CFML 90.54, whose PVD was also efficient in mediating iron uptake in strain PL10.9 (sv. 6) but was less efficient than PVD(51W) (Fig. 2, PVDs 5 and 24), was unable to efficiently use PVD(51W) or PVD(PL10.9) as illustrated in Table 3.

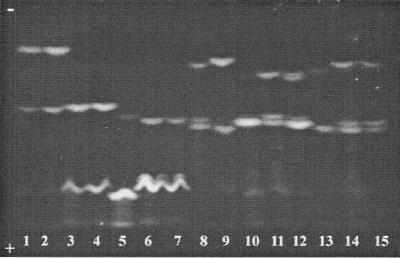

The comparison of the IEF patterns of the considered pyoverdines was in full agreement with a structural identity for PVD(PL24.1) and PVD(17400) (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2), PVD(PL10.9) and PVD(51W) (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4), PVD(PL4.14) and PVD(Pfl12) (Fig. 3, lanes 6 and 7), or PVD(PS7.2) and PVD(13525) (Fig. 3, lanes 14 and 15). Figure 3 also indicates that P. monteilii CFML 90.54 is producing a PVD with a particular IEF pattern (Fig. 3, lane 5) and which, therefore, and in agreement with the incorporation data, should be different in structure from the PVD of strain PL10.9 (Fig. 3, lane 3). It could also be deduced from the comparison of the IEF patterns that strains PS3b (sv. 5), PS11.4 (sv. 2), and PS8.12 (sv. 4) are producing specific PVDs, structurally different from the heterologous PVDs capable of mediating iron uptake in these strains, i.e., the PVDs of P. fluorescens 18.1 (Fig. 2, PVD 18; Fig. 3, lane 8), P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692 (Fig. 2, PVD 17; Fig. 3, lane 9), P. rhodesiae CFML 92.104 (Fig. 2, PVD 26; Fig. 3, lane 12), P. veronii CFML 92.124 (Fig. 2, PVD 27; Fig. 3, lane 13), and Pseudomonas sp. CFML 90.33 (Fig. 2, PVD 28; two bands with pI values of 4.2 and 3.8 [data not shown]).

FIG. 3.

IEF profiles of PVDs for some “P. reactans” isolates and some other pseudomonads having similar uptake efficiencies. PVDs originated from the indicated strains: lane 1, “P. reactans” PL24.1 (sv. 1); lane 2, P. fluorescens ATCC 17400; lane 3, “P. reactans” PL10.9 (sv. 6); lane 4, P. fluorescens 51W; lane 5, P. monteilii CFML 90.54; lane 6, “P. reactans” PL4.14 (sv. 7); lane 7, P. fluorescens 12; lane 8, P. fluorescens 18.1; lane 9, P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692; lane 10, “P. reactans” PS11.4 (sv. 2); lane 11, “P. reactans” PS3b (sv. 5); lane 12, P. rhodesiae CFML 92.104; lane 13, P. veronii CFML 92.124; lane 14, “P. reactans” PS7.2 (sv. 3); lane 15, P. fluorescens ATCC 13525.

Thus, siderotyping identified four of the eight “P. reactans” PVDs as being identical in structure to well-characterized PVDs, some of them being produced by taxonomically well-defined strains. Therefore, a correlation is suggested between the “P. reactans” sv. 1 strains and P. fluorescens biovar III (to which belongs P. fluorescens ATCC 17400) and between strain PL10.9 of “P. reactans” sv. 6 and P. fluorescens biovar V (to which belongs P. fluorescens 51W). Some uncertainty remains for the “P. reactans” sv. 3 strains, which could be related to P. fluorescens ATCC 13525, the type strain of the P. fluorescens biovar I, but also to the P. chlororaphis species since P. chlororaphis ATCC 9446 produces the same PVD as P. fluorescens ATCC 13525 (4). P. fluorescens 12 is a natural isolate whose precise taxonomic assignment among the P. fluorescens biovars remains unknown. However, it could be tentatively linked to the P. marginalis group belonging to P. fluorescens biovar II, since P. marginalis CFBP 4044 has been shown by siderotyping and structural identification to produce the same PVD as P. fluorescens 12 (R. Fuchs, J. M. Meyer, and H. Budzikiewicz, unpublished results).

Indeed, these correlations between “P. reactans” strains and more- or less-defined fluorescent Pseudomonas strains need to be confirmed by phenotypic and genomic taxonomy studies. It should be mentioned, however, that siderotyping has already been successfully used for a rapid and convenient identification of P. aeruginosa isolates (24). It has also already proved to be a reliable method for the discrimination of numerous Pseudomonas species recently described, e.g., P. brassicacearum, P. thivervalensis, P. monteilii, P. rhodesiae, P. veronii, P. jessenii, and P. mandelii (1; V. Coulanges, L. Gardan, D. Izard, P. Lemanceau, and J. M. Meyer, Abstr. 5° Congr. Soc. Fr. Microbiol. 1998, abstr. 47, 1998). Moreover, the fact that some of the correlations suggested in the present work well corresponded to previous taxonomic assignments (36) supports siderotyping as a powerful method for taxonomy studies within fluorescent Pseudomonas strains. The usefulness of the method is well demonstrated in the present study by the rapid identification of strain PS8.4V. Because of the loss of the white line and pathogenicity phenotypic features, PS8.14V would not be so easily identifiable, unless a rather time-consuming study based on classical taxonomic methods were undertaken. Thanks to siderotyping, PS8.14V was recognized as a P. tolaasii isolate within a few hours following growth completion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We deeply acknowledge N. J. Palleroni for critical reading of the manuscript. P. M. is grateful to S. Lakovaara for providing excellent research facilities and to J.-C. Hubert for training provided in his laboratory. M.-M. Kytöviita is acknowledged for the gift of the wild Agaricus sp. sporophore. MYKORA Ltd. (Finland) is thanked for kindly providing the mushrooms used in the pathogenicity tests.

P.M. is grateful to the Runar Bäckström Foundation for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achouak W, Sutra L, Heulin T, Meyer J M, Fromin N, Degreave S, Christen R, Gardan L. Description of Pseudomonas brassicacearum sp. nov. and Pseudomonas thivervalensis sp. nov., root-associated bacteria isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica napus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:9–18. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradbury J F. CMI descriptions of pathogenic fungi and bacteria. Set 90, no. 891–900. CAB International Mycological Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodey C L, Rainey P B, Tester M, Johnstone K. Bacterial blotch disease of the cultivated mushroom is caused by an ion channel forming lipodepsipeptide toxin. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:407–411. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budzikiewicz H. Siderophores of fluorescent pseudomonads. Z Naturforsch Sect C. 1997;52:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budzikiewicz H, Kilz S, Taraz K, Meyer J M. Identical pyoverdines from Pseudomonas fluorescens 9BW and from Pseudomonas putida 9BW. Z Naturforsch Sect C. 1997;52:721–728. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champomier-Verges M-C, Richard J. Anti-bacterial activity among Pseudomonas strains of meat origin. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole A L J, Skellerup M V. Ultrastructure of the interaction of Agaricus bisporus and Pseudomonas tolaasii. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1986;87:314–316. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutri S S, MacAuley B J, Roberts W P. Characteristics of pathogenic non-fluorescent (smooth) and non-pathogenic fluorescent (rough) forms of Pseudomonas tolaasii and Pseudomonas gingeri. J Appl Bacteriol. 1984;57:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demange P, Bateman A, Mertz C, Dell A, Piémont Y, Abdallah M. Bacterial siderophores: structures of pyoverdins Pt, siderophores of Pseudomonas tolaasii NCPPB 2192, and pyoverdins Pf, siderophores of Pseudomonas fluorescens CCM 2798. Identification of an unusual natural amino acid. Biochemistry. 1990;29:11041–11051. doi: 10.1021/bi00502a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vos P, Goor M, Gillis M, De Ley J. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistron similarities of phytopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:169–184. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott R P. Some properties of pyoverdine, the water-soluble pigment of the Pseudomonas. Appl Microbiol. 1958;6:241–246. doi: 10.1128/am.6.4.241-246.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elomari M, Coroler L, Verhille S, Izard D, Leclerc H. Pseudomonas monteilii sp. nov., isolated from clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:846–852. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandy D G. A technique for screening bacteria causing brown blotch of cultivated mushrooms. Rep Glasshouse Crops Res Inst. 1967;1967:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandy D G. Proceedings of the Bacterial Blotch Symposium. Littlehampton, United Kingdom: International Society for Mushroom Science; 1982. Bacterial blotch: nature of the disease and its causal organisms; pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geisen K, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H. Neue Siderophore des Pyoverdin-Typs aus Pseudomonas fluorescens. Monatsh Chem. 1992;123:151–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgias H, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H, Geoffroy V, Meyer J M. The structure of the pyoverdin from Pseudomonas fluorescens 1.3. Structural and biological relationships of pyoverdins from different strains. Z Naturforsch Sect C. 1999;54:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goor M, Vandamme R, Swings J, Gillis M, Kersters K, De Ley J. Phenotypic and genotypic diversity of Pseudomonas tolaasii and white line reacting organisms isolated from cultivated mushrooms. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2249–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grewal S I S, Han B, Johnstone K. Identification and characterization of a locus which regulates multiple functions in Pseudomonas tolaasii, the cause of brown blotch disease of Agaricus bisporus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4658–4668. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4658-4668.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohnadel D, Meyer J M. Specificity of pyoverdine-mediated iron uptake among fluorescent Pseudomonas strains. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4865–4873. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4865-4873.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu F P, Young J-M, Fletcher M J. Preliminary description of biocidal (syringomycin) activity in fluorescent plant pathogenic Pseudomonas species. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:365–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer J M, Abdallah M A. The fluorescent pigment of Pseudomonas fluorescens: biosynthesis, purification and physicochemical properties. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;107:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer J M, Hornsperger J M. Role of pyoverdinePf, the iron-binding fluorescent pigment of Pseudomonas fluorescens, in iron transport. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;107:329–331. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer J M, Stintzi A. Iron metabolism and siderophores in Pseudomonas and related species. In: Montie T C, editor. Biotechnology handbooks, vol. 10. Pseudomonas. New York, N. Y: Plenum Publishing Co.; 1998. pp. 201–243. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer J M, Stintzi A, De Vos D, Cornelis P, Tappe R, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H. Use of siderophores to type pseudomonads: the three Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine systems. Microbiology. 1997;143:35–43. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer J M, Coulanges V, Shivaji S, Voss J A, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H. Siderotyping of fluorescent pseudomonads: characterization of pyoverdines of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida strains from Antarctica. Microbiology. 1998;144:3119–3126. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortishire-Smith R J, Nutkins J C, Packman L C, Brodey C L, Rainey P B, Johnstone K, Williams D H. Determination of the structure of an extracellular peptide produced by the mushroom saprotroph Pseudomonas reactans. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:3645–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munsch P. Lutte biologique contre la tache bactérienne du champignon de Paris au moyen de bactériophages. Doctoral thesis, no. 229. Pau, France: Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nair N J, Fahy P C. Toxin production by Pseudomonas tolaasii Paine. Aust J Biol Sci. 1973;26:509–512. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nutkins J C, Mortishire-Smith R J, Packman L C, Brodey C L, Rainey P B, Johnstone K, Williams D H. Structure determination of tolaasin, an extracellular lipodepsipeptide produced by the mushroom pathogen Pseudomonas tolaasii Paine. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2621–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olivier J M, Guillaumes J, Martin D. Study of a bacterial disease of mushroom caps. 1978. pp. 903–916. . Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, Angers, France. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palleroni N J. Gram negative aerobic rods and cocci, family I: Pseudomonadaceae. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1984. pp. 141–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preece T F, Wong W C. Quantitative and scanning electron microscope observations on the attachment of Pseudomonas tolaasii and other bacteria to the surface of Agaricus bisporus. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1982;21:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rainey P B, Brodey C L, Johnstone K. Biological properties and spectrum of activity of tolaasin, a lipodepsipeptide toxin produced by the mushroom pathogen Pseudomonas tolaasii. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;39:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rainey P B, Brodey C L, Johnstone K. Biology of Pseudomonas tolaasii, cause of brown blotch disease of the cultivated mushroom. Adv Plant Pathol. 1992;8:95–117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tolaas A G. A bacterial disease of cultivated mushrooms. Phytopathology. 1915;5:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells J M, Sapers G M, Fett W P, Butterfield J E, Jones J B, Bouzar H, Miller F C. Postharvest discoloration of the cultivated mushroom Agaricus bisporus caused by Pseudomonas tolaasii, P. ‘reactans’, and P.1 ‘gingeri’. Phytopathology . 1996;86:1098–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong W C, Preece T F. Identification of Pseudomonas tolaasii: the white line in agar and mushroom tissue block rapid pitting tests. J Appl Bacteriol. 1979;47:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zarkower P A, Wuest P J, Royse D J, Myers B. Phenotypic traits of fluorescent pseudomonads causing bacterial blotch of Agaricus bisporus mushrooms and other mushroom-derived fluorescent pseudomonads. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:360–367. [Google Scholar]