Abstract

Introduction:

Patients undergoing surgery are anxious owing to the surgery, anesthesia, and unfamiliar environment of the operation theater. This anxiety can hamper the health and recovery of the patients. Among various nonpharmacologic modalities available, music can be used as a coping strategy to change uncomfortable conditions to the pleasant ones.

Aims:

To evaluate the role of music on perioperative anxiety, hemodynamic parameters, and patient satisfaction in patients undergoing orthopedic surgeries under spinal anesthesia.

Settings and design:

Tertiary care hospital, randomized control trial.

Materials and methods:

The study was conducted after approval by Hospital Ethical Committee on 70 adult patients of either gender scheduled to undergo lower limb surgeries under spinal anesthesia. In group M (n = 35), patients listened to standard relaxation music, and in group C (n = 35), patients listened to standard operation theater noise tape through noise canceling headphones. The intraoperative hemodynamic parameters were recorded. Perioperative anxiety was assessed using visual analog scale for anxiety. Sedation score was observed using observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation scale. Patient’s satisfaction was also assessed in both the groups.

Statistical analysis:

Student t test, Chi-squared test, and paired sample t test.

Results:

In group M, heart rate was lower when compared with group C. The difference was statistically significant at 10 minutes of assessment (P = 0.003) and statistically highly significant (P < 0.001) for rest of the time period. Statistically significant lower respiratory rate was there in group M when compared with group C (P = 0.05). Patients were more satisfied in the music group when compared with control group.

Conclusion:

The potential of music therapy can be used to allay patient anxiety, stabilize hemodynamics, and improve patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Anxiety, hemodynamics, music, spinal anesthesia

Key Messages: Music is an inexpensive nonpharmacologic method that can be used effectively to allay patient’s perioperative anxiety with improved patient satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

The perioperative period is one of the unpleasant and stressful psychologic experience for the patient.[1] Patients are worried about the pain, outcomes of surgery, and recovery after surgery. Unfamiliar environment of operation theater (OT) along with noise of monitors, surgical instrumentation, and doctors/staff conversations add on to the anxiety of the patient.[2]

Anxiety leads to activation of the sympathetic nervous system. It causes release of stress hormones which can cause delayed wound healing and hence delayed recovery.[3] Stress has also been shown to be associated with delayed gastric emptying, increase in the metabolism and oxygen consumption, as well as the chances of thromboembolic events. Hence, anxiety can ultimately lead to increased pharmacologic interventions and sometimes cancellation of procedures and patient dissatisfaction.[4]

Regional anesthesia technique is usually preferred over general anesthesia due to its inherent benefits.[5] However, patients undergoing regional anesthesia are usually awake during surgery and are exposed to multiple anxiety provoking visual and auditory stimuli.[6] Patients even sometimes refuse regional anesthesia because they do not want to “hear” their surroundings.[7] Strain of the sick patient listening to a conversation that may be concerning them is also one of the major ethical issues. OT noises can add on to this effect.

Florence Nightingale stated that “Unnecessary noise is that which hurts a patient” in her Notes on Nursing in 1859.[8] Noise is defined as any unwanted or undesirable sound which is annoying or disruptive. Noise is now labeled as the third pollution.[9] It itself has several detrimental effects on humans such as alterations in endocrine, cardiovascular, and auditory systems along with psychologic effects such as annoyance, irritability, headaches, and tiredness.

Noise levels in hospitals sometimes increase to an extent that they become harmful to both patients and personnel. The average noise level in the operating room is in the range of 60 to 65 decibels (dB, A), but it may even exceed 90 dB (A) in certain situations, which is the maximum level of noise permissible in 8 hours according to Occupational Safety and Health Administration, United States America.[10]

Various studies have found that orthopedic surgeries are associated with highest level of noise owning to the use of hammers and drills. The sound of an oscillating saw can even reach up to 105 dB.[11]

To negate the effect of anxiety and noise in OT, a calm, quiet, and tranquil environment for patient can be achieved by both pharmacologic as well as nonpharmacologic methods. Pharmacologic methods include use of sedatives and anxiolytic drugs. They are regularly administered before and during surgery but they can cause undesirable dose-dependent central nervous system and cardiorespiratory system depression. Nonpharmacologic methods include acupressure, hypnosis, therapeutic suggestions, white noise, and music. They all have been tried in different medical setups with varied success rate with an aim to decrease the harmful effects of pharmacologic agents.[12,13]

Although the supportive evidence exists regarding the benefits of music in various health care settings but data supporting its use in OTs are still in paucity. Hence, present study was planned to study the effect of music on perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing orthopedics surgeries under spinal anesthesia.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the department of anesthesiology, in a tertiary care hospital, after approval by Institutional Ethical Committee and Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI/2019/04/018842).

Patients undergoing elective surgeries under spinal anesthesia with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades I and II and age group 18 to 60 years of either gender were involved in study. Patients with any contraindication to spinal anesthesia, patients with hearing impairment, and known psychiatric or memory disorder were excluded from study. A written and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

A total of 70 patients were randomly divided into two groups of 35 patients each. The sample size was calculated by considering 80% power (20% beta error) and 5% significance level (alpha error) to detect a mean difference of State Trait Anxiety Inventory State test (STAI-SA) scores between music and control group as 4.2. This was based on study in which mean ± standard deviation (SD) of STAI-SA scores in music group was 28.0 ± 6.2 and in control group was 32.2 ± 4.6. By using the above parameters, the estimated sample size was 27 in each group.[14] For possible drop outs, 35 patients were included in each group.

A thorough preanesthetic checkup was conducted preoperatively. All patients were investigated. During the preanesthetic checkup, the patients were explained about the purpose of study. They were familiarized with the use of visual analog scale for anxiety (VAS-A) for the assessment of anxiety and observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation (OAA/S) scale for the assessment of level of sedation/alertness. All the patients were explained that noise cancelling headphones will be applied to their ears during surgery and it may contain music or standard OT noise.

Selection to music or no-music group was carried out using computer-generated randomization into group M (music) and group C (control, i.e., no music). Group M listened to standard relaxation music, whereas group C listened to standard OT noise tape through noise cancelling headphones.

Due to the nature of intervention planned, patient involved in the study could not be blinded for the group allocation. The surgeons, designated anesthesiologist for data collection, and the staff nurses present in the OT were blinded for the study.

The baseline anxiety by VAS-A and level of sedation/alertness by OAA/S were recorded preoperatively [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Visual analog scale for anxiety

| Score | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 8–10 | Out-of-control behavior, hitting, rhyming voices |

| 6–7 | Strong agitation, pacing |

| 5 | Moderate worry, physical agitation |

| 3–4 | Mild fear and worry |

| 1–2 | Slight fear and worry |

| 0 | Absence of symptoms |

Table 2.

Observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation scale

| Score | Responsiveness |

|---|---|

| 5 | Responds readily to name spoken in normal tone |

| 4 | Lethargic response to name spoken in normal tone |

| 3 | Responds only after name is called loudly and/or repeatedly |

| 2 | Responds only after mild prodding or shaking |

| 1 | Responds only after painful trapezius squeeze |

| 0 | No response after painful trapezius squeeze |

In OT, baseline hemodynamic parameters, that is, heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP), saturation (SpO2), and respiratory rate (RR) were noted. An 18-gauge intravenous cannula was secured and infusion of crystalloid solution was started.

Spinal anesthesia was administered with 3 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% heavy. After confirmation of an adequate dermatomal level of anesthesia, all patients received an intravenous dose of midazolam (25 μg/kg).

After randomization and before surgery, the designated member, not included in the study, placed the dedicated music player in an opaque box specially constructed to assure blindness and connected the headphones to music player. He placed the headphones on the patients’ ear and the assigned intervention was delivered. The relaxation music was started for the group M patients and the sound level was maintained at the level the patient indicated as most comfortable. It was same music for all the patients. Group C received standard OT tape sounds. Inside the OT, team of anesthesiologists was strictly instructed to not touch the headphones or examine it for presence or absence of sounds.

Vital parameters and noise level (in dB) of OT were assessed initially every 5 minutes for first 30 minutes, then every 10 minutes till 60 minutes and subsequently every 15 minutes till the completion of surgery. Anxiety (VAS-A) and sedation score (OAA/S) were assessed every half hourly. Music player was temporarily turned off before each OAA/S assessment to assure blindness. At the end of surgery, the headphones were removed after switching off the music player.

A drop of more than 20% in SBP relative to the baseline indicated hypotensive state and was treated with bolus of 100 mL fluid and if uncorrected, injection mephentermine 3 mg bolus, intravenously, was given. HR of less than 50 per minute was considered as bradycardia and was treated with an intravenous bolus of injection atropine 0.6 mg.

Postoperatively the blinded member assessed the anxiety by VAS-A. Patient satisfaction score was noted at the end of 24 hours using patient satisfaction score as 1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = undecided, 4 = dissatisfied, and 5 = very dissatisfied.

After completion of the study, the results were compiled and entered in MS Excel. Analysis was carried out using SPSS 21.0 version statistical program for Microsoft Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2012, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Continuous variables were presented as mean and SD, whereas categorical variables were presented as percent. The quantitative variables were compared using the unpaired Student t test. To compare paired quantitative variables, paired t test was performed. The qualitative/categorical data were compared using the Chi-squared test. P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and <0.001 as highly significant.

RESULTS

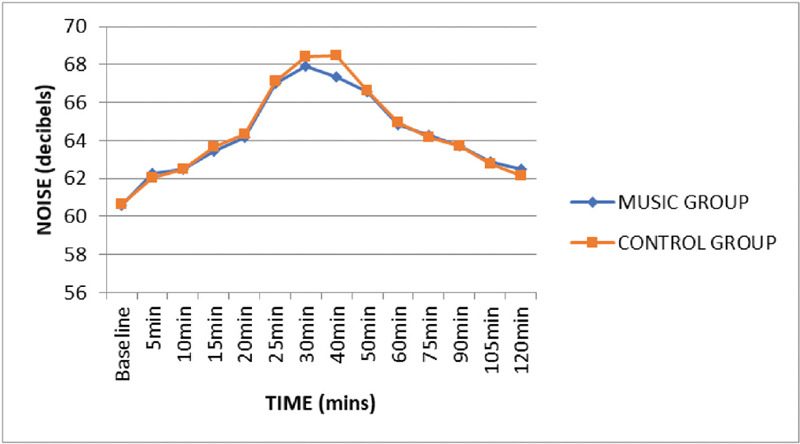

Both the groups were comparable in terms of age, weight, height, body mass index, gender, ASA status, duration of surgery [Table 3] and noise levels in OT [Figure 1].

Table 3.

Demographic parameters and duration of surgery

| Parameter | Group M | Group C | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.66 ± 11.67 | 36.97 ± 12.06 | 0.810 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.11 ± 4.94 | 68.89 ± 4.91 | 0.847 |

| Height (cm) | 163.69 ± 5.56 | 165.11 ± 5.11 | 0.267 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.82 ± 1.86 | 25.30 ± 1.93 | 0.252 |

| Gender (male:female) | 26:9 | 28:7 | 0.569 |

| ASA grade (I:II) | 20:15 | 21:14 | 0.808 |

| Duration of surgery in minutes | 81.14 ± 11.64 | 79.00 ± 12.94 | 0.469 |

P > 0.05, not significant. BMI, body mass index.

Figure 1.

Mean perioperative noise levels (in decibels) of operation theatre at various time intervals..

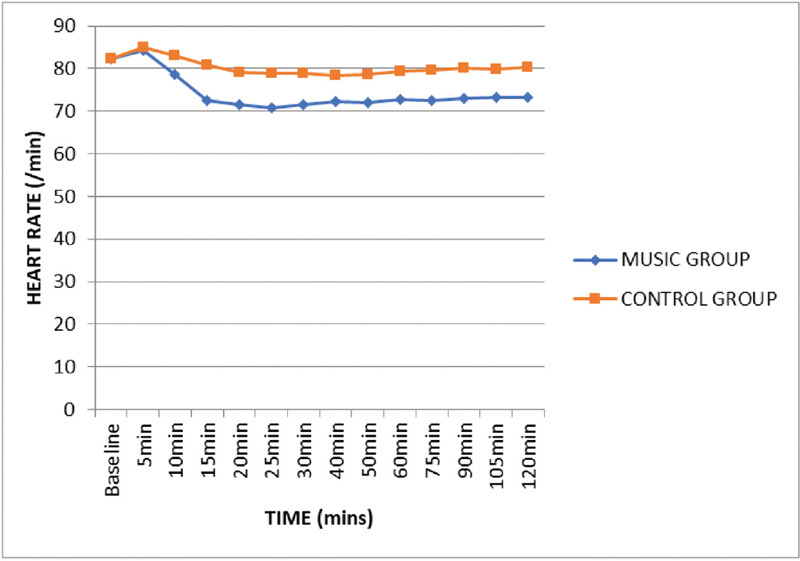

The HR was comparable in both music (M) and control (C) groups at baseline and 5 minutes of assessment. Thereafter, HR was lower in group M throughout the perioperative time period. The difference was statistically significant at 10 minutes of assessment (P = 0.003) and statistically highly significant (P < 0.001) for rest of the time period [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Mean perioperative heart rate (/minute) at various time intervals.

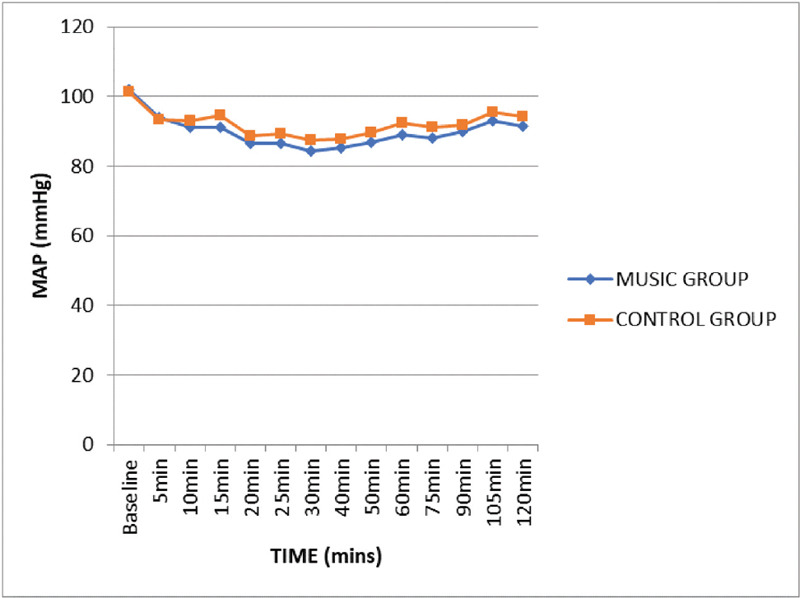

Baseline MAP was comparable in groups M and C (P > 0.05). In the present study, no appreciable difference was noted MAP at all time intervals (P > 0.05) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Mean perioperative mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) at various time intervals.

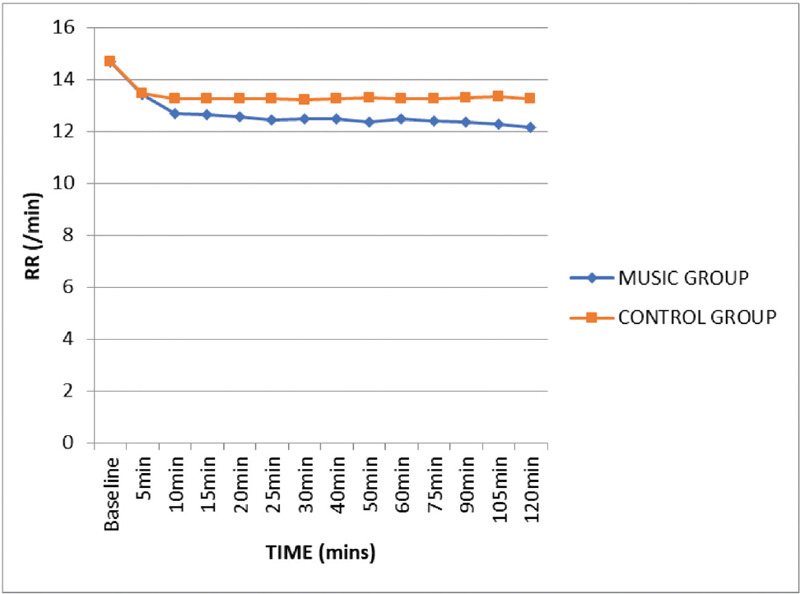

Baseline RR was comparable in both groups M and C with P-value being 0.916. After 5 minutes of intervention, we noticed statistically significant lower RR in group M when compared with group C (P < 0.05) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Mean perioperative respiratory rate (/minute) at various time intervals.

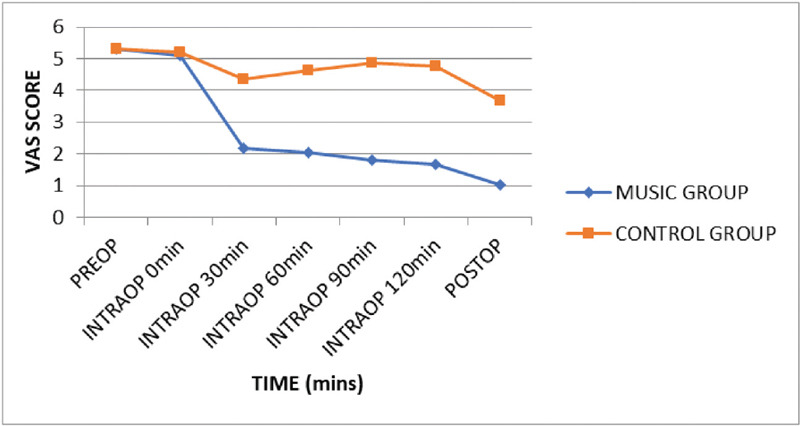

The VAS-A score was comparable in both the groups at preoperative time and before anesthesia induction. VAS score was lower for group M for rest of the intraoperative assessment and at postoperative time period (P < 0.001) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Mean visual analog scale (VAS) score for anxiety at various time intervals.

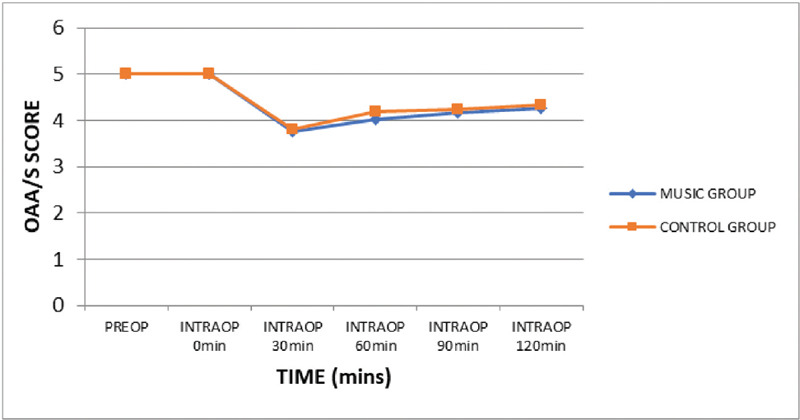

The OAA/S score was comparable in both the groups throughout the preoperative and intraoperative assessments (P > 0.05) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Comparison of mean observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation (OAA/S) score at various time intervals.

Patient satisfaction score was better in group M when compared with group C (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Patient satisfaction score in study groups

| Satisfaction score | Music group(n = 35) | Control group(n = 35) | Chi-squared testP-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| 1 (Very satisfied) | 27 | 77.1 | 3 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| 2 (Satisfied) | 7 | 20.0 | 23 | 65.7 | |

| 3 (Undecided) | 1 | 2.9 | 9 | 25.7 | |

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 | |

DISCUSSION

Anxiety is defined as an emotional human reaction accompanied by an autonomic response. It is basically a vague uneasy feeling of discomfort or dread that signals the individual to take measures to deal against it.[15]

The present study was conducted on 70 patients scheduled to undergo lower limb surgeries under spinal anesthesia. Both the groups were comparable in terms of duration of surgery and noise levels in OT [Table 3, Figure 1]. It is usually reported that as duration of surgery increases under regional anesthesia, the patient’s anxiety may continue to increase and there is increased requirement of sedative drugs as well.[16]

Noise levels of the OT (in dB) were comparable between the two groups (P > 0.05). The level of noise in the operating room can vary owing to different sources of noise, that is, related to surgical activity such as suction not in use (73 dB(A)), suction in use (75–80 dB(A)), dropping instruments into bowl (75 dB(A)), knocking stainless steel bowls (80–85 dB(A)), anesthetic-related activity such as automatic BP machine inflation (45–53 dB(A)), ventilator disconnect alarm (75 dB(A)), ECG alarm (74–78 dB(A)), pulse oximeter (60–70 dB(A)), communication in OT (60–66 dB(A)), removing the pin (65 dB(A)), arthroscopy (77 dB(A)), plating (67 dB(A)), and Kuntscher interlock (79 dB(A)).[10,17]

In the present study, baseline HR was comparable in groups M and C with P-value being 0.955. Group M showed a drop in HR intraoperatively. No appreciable difference was noted in MAP at all time intervals (P > 0.05) [Figure 2]. Statistically significant lower RR was noted at all the time intervals in group M when compared with group C (P < 0.05). In the present study, there was statistically highly significant difference in anxiety score between both the groups (P < 0.001) throughout the perioperative assessment.

These hemodynamic effects of music can be explained by the fact that music causes decrease in the levels of several hormones and biochemical markers of stress such as cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine, etc., due to neural interconnections of the auditory pathway with the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and the reticular activating system and also due to mental distraction and diminished unpleasant noises of OT.[6,18] Auditory interconnections within the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and the reticular activating system attenuate the release of excitatory neurotransmitters which are responsible for relaxing and sedative effects of music.[19] It distracts one’s attention from negative stimuli and focuses the patient’s awareness on the music.[14] Music contains delightful beats and melodies which help individuals to achieve a peaceful state, ease patient’s discomfort and maintain and promote body and mind health.[15]

Music affects the limbic system which regulates deep emotions and many autonomic parameters. It has been postulated that music causes the body to release its own endorphins, hence decreasing pain and analgesic requirements. [19]

The decrease in anxiety can be due to the release of endorphins in the brain which produce an atmosphere of peace and tranquility. Further, it has been studied that brain and heart beats synchronize with the rhythm and beats of music which leads to entrainment phenomenon. This relaxes and calms the body.[16]

Beneficial effect of music is also reported by study carried out by Sarkar et al.[20] on pregnant patients, by Bansal et al. [6] on patients undergoing abdominal, urologic, and lower extremity surgeries, and Syal et al. [21] on patients under spinal anesthesia. Syal et al. showed highly significant (P < 0.001) reduced anxiety levels in patients who received music therapy (1.76 ± 0.59) than control group (2.92 ± 0.52) after music intervention.[21]

In intensive care setting also, music has proven to be an effective nonpharmacologic intervention. Chan et al. found that patients who listened to music in intensive care units when undergoing a C-clamp procedure after percutaneous coronary interventions had statistically significant decrease in HR and SBP.[22]

Music along with routine postoperative care is found to be effective in the study by Lee et al. on 100 patients in the postanesthesia care unit. They observed statistically significant difference in HR, BP, and RR in both the groups. Patients with music intervention significantly lowered anxiety when compared with the control group.[15]

Our results were similar with the findings by Ilkkaya et al. who studied the effect of music (group M), white noise (group B), and ambient noise (group O) on patients scheduled for surgical procedures under spinal anesthesia. They used both VAS and STAI-TA/SA scales to evaluate the effect of music on anxiety. They found that during the preoperative period which included prespinal and postspinal periods (before surgery) till 30 minutes, VAS values in group M were significantly lower than in groups B and O (P = 0.004 and 0.006, respectively). Similarly, during the intraoperative period, VAS values in group M were significantly lower than in groups B and O (P = 0.005 and 0.004, respectively).[14] Kukreja et al. and Sarkar et al. also shown decreased anxiety levels in patients in music group.[5,20]In our study, it was found that there was no significant difference between the two groups in regards to sedation score (P > 0.05). In a study carried out by Kukreja et al. studying the effect of music therapy in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia found that compared to the control group, music therapy did not reduce propofol requirements according to bispectral index (BIS) monitor target range for moderate sedation.[5] However, there are few studies who have demonstrated that music decreases the sedative requirements intraoperatively.[6]

Patients were more satisfied in group M than in group C. Hence, this study demonstrates the effective role of music in perioperative period in terms of decreased anxiety, stable hemodynamics, and improved patient satisfaction. As a familiar and aesthetic medium, music offers auditory stimuli that can mask adverse sound stimuli. It is an inexpensive, noninvasive and safe nonpharmacologic method that can aid to decrease anxiety.[16]

This study was a small attempt to demonstrate the beneficial effect of music on anxiety in patients undergoing lower limb surgeries under spinal anesthesia. But this study has few limitations such as due to the type of intervention patient could not be blinded which could be a source of bias. The music therapy, if extended, into the preoperative and postoperative periods could have further helped to evaluate the effect of music on patients. The use of BIS monitoring to assess sedation level and use of more complex or objective questionnaires to assess anxiety could have added to the significance of results of present study. Keeping in mind these limitations, further studies can be conducted to verify the results of present study.

CONCLUSION

Music is a noninvasive, nonpharmacologic, nonhazardous, and cost-effective intervention, which can be a useful adjuvant with multifold benefits during perioperative period in patients undergoing surgeries under spinal anesthesia. It allays patient anxiety, stabilize hemodynamic profile and improve patient satisfaction.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen S, Svensson M, Nilsson U. Calm or not calm: the question of anxiety in the perianesthesia patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23:237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell M. Patient anxiety and modern elective surgery: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:806–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thoma M, Marca R, Bronnimann R, Finkel L, Ehlert U, Nater U. The effect of music on the human stress response. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetter D, Barth J, Uyulmaz S, et al. Effects of art on surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:704–13. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kukreja P, Talbott K, Macbeth L, et al. Effects of music therapy during total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia: a prospective randomized controlled study. Cureus. 2020;12:1–9. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bansal P, Kharod U, Patel P, Sanwatsarkar S, Patel H, Kamat H. The effect of music therapy on sedative requirements and haemodynamic parameters in patients under spinal anaesthesia: a prospective study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2010;4:2782–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graff V. Role of music in the perioperative setting. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;17:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson B, Raymond S, Goss J. Perioperative music or headsets to decrease anxiety. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27:146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro R, Berland T. Noise in the operating room. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:1236–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197212142872407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kam P, Kam A, Thompson J. Noise pollution in the anaesthetic and intensive care environment. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:982–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson J, Hamer A. How noisy are total knee and hip replacements? J Perioper Pract. 2017;27:292–5. doi: 10.1177/175045891702701204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Good M, Stanton-Hicks M, Grass J, et al. Relief of postoperative pain with jaw relaxation, music and their combination. Pain. 1999;81:163–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson U, Rawal N, Unestahl L, Zetterberg C, Unosson M. Improved recovery after music and therapeutic suggestions during general anesthesia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:812–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045007812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilkkaya N, Ustun F, Sener E, et al. The effects of music, white noise and ambient noise on sedation and anxiety in patients under spinal anaesthesia during surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2014;29:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee W, Wu P, Lee M, Ho L, Shih W. Music listening alleviates anxiety and physiological responses in patients receiving spinal anesthesia. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma V, Premendran B, Dongre H, Domkondwar U. The efficacy of music in lowering intra-operative sedation requirement and recall of intra operative processes. IOSR J Pharma. 2012;2:569–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giv M, Sani K, Alizadeh M, Valinejadi A, Majdabadi A. Evaluation of noise pollution level in the operating rooms of hospitals: a study in Iran. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2017;9:61–6. doi: 10.1556/1646.9.2017.2.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur H, Shukla V, Bansal G, Harsh H, Joseph A, Bharadwaj M. Extra note of music in anaesthesia. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7:3219–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalyani N, Poonam G, Shalini K. Impact of intraoperative music therapy on the anesthetic requirement and stress response in laproscopic surgeries under general anesthesia. Ain-Shams J Anaesthesiol. 2015;8:580–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar D, Chakrabarty K, Bhadra B, Singh R, Mandal U, Ghosh D. Effects of music on patients undergoing caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Int J Recent Trends Sci Tech. 2015;13:633–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syal K, Singh D, Verma R, Kumar R, Sharma A. Effect of music therapy in relieving anxiety in patients undergoing surgery. IJARS. 2017;6:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan M, Wong O, Chan H, et al. Effects of music on patients undergoing a C-clamp procedure after percutaneous coronary interventions. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:669–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]