Abstract

Background

Periodontitis is a highly prevalent, chronic inflammation that causes damage to the soft tissues and bones supporting the teeth. Conventional treatment is quadrant scaling and root planing (the second step of periodontal therapy), which comprises scaling and root planing of teeth in one quadrant of the mouth at a time, with the four different sessions separated by at least one week. Alternative protocols for anti‐infective periodontal therapy have been introduced to help enhance treatment outcomes: full‐mouth scaling (subgingival instrumentation of all quadrants within 24 hours), or full‐mouth disinfection (subgingival instrumentation of all quadrants in 24 hours plus adjunctive antiseptic). We use the older term 'scaling and root planing' (SRP) interchangeably with the newer term 'subgingival instrumentation' in this iteration of the review, which updates one originally published in 2008 and first updated in 2015.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effects of full‐mouth scaling or full‐mouth disinfection (within 24 hours) for the treatment of periodontitis compared to conventional quadrant subgingival instrumentation (over a series of visits at least one week apart) and to evaluate whether there was a difference in clinical effects between full‐mouth disinfection and full‐mouth scaling.

Search methods

An information specialist searched five databases up to 17 June 2021 and used additional search methods to identify published, unpublished and ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) lasting at least three months that evaluated full‐mouth scaling and root planing within 24 hours, with or without adjunctive use of an antiseptic, compared to conventional quadrant SRP (control). Participants had a clinical diagnosis of (chronic) periodontitis according to the International Classification of Periodontal Diseases from 1999. A new periodontitis classification was launched in 2018; however, we used the 1999 classification for inclusion or exclusion of studies, as most studies used it. We excluded studies of people with systemic disorders, taking antibiotics or with the older diagnosis of 'aggressive periodontitis'.

Data collection and analysis

Several review authors independently conducted data extraction and risk of bias assessment (based on randomisation method, allocation concealment, examiner blinding and completeness of follow‐up). Our primary outcomes were tooth loss and change in probing pocket depth (PPD); secondary outcomes were change in probing attachment (i.e. clinical attachment level (CAL)), bleeding on probing (BOP), adverse events and pocket closure (the number/proportion of sites with PPD of 4 mm or less after treatment). We followed Cochrane's methodological guidelines for data extraction and analysis.

Main results

We included 20 RCTs, with 944 participants, in this updated review. No studies assessed the primary outcome tooth loss. Thirteen trials compared full‐mouth scaling and root planing within 24 hours without the use of antiseptic (FMS) versus control, 13 trials compared full‐mouth scaling and root planing within 24 hours with adjunctive use of an antiseptic (FMD) versus control, and six trials compared FMS with FMD.

Of the 13 trials comparing FMS versus control, we assessed three at high risk of bias, six at low risk of bias and four at unclear risk of bias. We assessed our certainty about the evidence as low or very low for the outcomes in this comparison. There was no evidence for a benefit for FMS over control for change in PPD, gain in CAL or reduction in BOP at six to eight months (PPD: mean difference (MD) 0.03 mm, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.14 to 0.20; 5 trials, 148 participants; CAL: MD 0.10 mm, 95% CI –0.05 to 0.26; 5 trials, 148 participants; BOP: MD 2.64%, 95% CI –8.81 to 14.09; 3 trials, 80 participants). There was evidence of heterogeneity for BOP (I² = 50%), but none for PPD and CAL.

Of the 13 trials comparing FMD versus control, we judged four at high risk of bias, one at low risk of bias and eight at unclear risk of bias. At six to eight months, there was no evidence for a benefit for FMD over control for change in PPD or CAL (PPD: MD 0.11 mm, 95% CI –0.04 to 0.27; 6 trials, 224 participants; low‐certainty evidence; CAL: 0.07 mm, 95% CI –0.11 to 0.24; 6 trials, 224 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The analyses found no evidence of a benefit for FMD over control for BOP (very low‐certainty evidence). There was no evidence of heterogeneity for PPD or CAL, but considerable evidence of heterogeneity for BOP, attributed to one study. There were no consistent differences in these outcomes between intervention and control (low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence).

Of the six trials comparing FMS and FMD, we judged two trials at high risk of bias, one at low risk of bias and three as unclear. At six to eight months, there was no evidence of a benefit of FMD over FMS for change in PPD or gain in CAL (PPD: MD –0.11 mm, 95% CI –0.30 to 0.07; P = 0.22; 4 trials, 112 participants; low‐certainty evidence; CAL: MD –0.05 mm, 95% CI –0.23 to –0.13; P = 0.58; 4 trials, 112 participants; low‐certainty evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between FMS and FMD for BOP at any time point (P = 0.98; 2 trials, 22 participants; low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence). There was evidence of heterogeneity for BOP (I² = 52%), but not for PPD or CAL.

Thirteen studies predefined adverse events as an outcome; three reported an event after FMD or FMS. The most important harm identified was an increase in body temperature.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for most comparisons and outcomes as low because of design limitations leading to risk of bias, and the small number of trials and participants, leading to imprecision in the effect estimates.

Authors' conclusions

The inclusion of nine new RCTs in this updated review has not changed the conclusions of the previous version of the review. There is still no clear evidence that FMS or FMD approaches provide additional clinical benefit compared to conventional mechanical treatment for adult periodontitis. In practice, the decision to select one approach to non‐surgical periodontal therapy over another should include patient preference and the convenience of the treatment schedule.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Anti-Infective Agents, Local; Anti-Infective Agents, Local/therapeutic use; Chronic Periodontitis; Chronic Periodontitis/drug therapy; Tooth Loss

Plain language summary

Treating all teeth (full mouth) within 24 hours for gum disease (periodontitis) in adults

Background

Long‐lasting gum disease (periodontitis) is a common chronic inflammatory disease that causes damage to soft tissues (gums) and bone around teeth, and can result in tooth loss. Non‐surgical treatments are used to stop and control the disease. These are based on 'subgingival instrumentation', that is, the mechanical removal of bacteria below the gums from the infected root surfaces of the teeth.

Conventional treatment is carried out in two to four sessions over several weeks, scaling a different section (or 'quadrant') of the mouth each time. This has traditionally been known as 'scaling and root planing' (SRP). An alternative approach is to treat the whole mouth within 24 hours in one or two sessions (known as full‐mouth scaling (FMS)). When an antiseptic agent (like chlorhexidine) is added to FMS, the intervention is called full‐mouth disinfection (FMD). The rationale for using these full‐mouth approaches is to reduce the likelihood of re‐infection in already treated sites.

Review question

This review, produced within Cochrane Oral Health, is the second update of one we originally published in 2008. It evaluates the effectiveness of full‐mouth treatments within 24 hours (FMS and FMD) compared to conventional treatment over a number of weeks, and whether there is a difference between FMS and FMD. The evidence is current up to June 2021.

Study characteristics

The included studies were randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) that evaluated a full‐mouth approach to subgingival instrumentation, with at least three months of monitoring (follow‐up). Both FMS and FMD were compared to conventional quadrant SRP (control). Participants had a clinical diagnosis of chronic periodontitis and we excluded studies of people with aggressive periodontitis, systemic disorders (affecting other part of the body) or who were taking antibiotics.

We included nine new studies in this update and we excluded one trial that had been included in the previous version of the review. In total, the review now includes 20 studies that involved 944 participants.

Key results

Treatment effects of FMS and FMD are modest and there are no clear implications for periodontal care. Neither treatment was superior to the usual treatment of scaling and root planing a quarter of the mouth at a time.

The most important harm identified was an increased body temperature after FMS or FMD treatments, reported in three out of 13 studies.

In practice, the decision to select one approach over another will be based on preference and convenience for patient and dentist.

Certainty of the evidence

Our confidence in the results is low for most comparisons and outcomes, due to the small number of studies and participants involved, and limitations in study designs. The addition of nine studies has not changed the findings of our previous version of this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Full‐mouth scaling compared to control for periodontitis in adults.

| FMS compared to control for periodontitis in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults with periodontitis Setting: university dental departments Intervention: FMS Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with FMS | |||||

| Tooth loss | None of the studies comparing FMS vs control reported tooth loss. | |||||

| Change in PPD: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in PPD was 0.27 mm to 1.80 mm | MD 0.03 mm higher (0.14 lower to 0.20 higher) | — | 148 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Similar results at 3–4 months. Subgroup analyses of 6‐ to 8‐month data were undertaken for:

See Table 2; Table 3; Table 4. There was no consistent evidence of a benefit for FMS. |

| Change in CAL: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in CAL was 0.19 mm to 1.10 mm | MD 0.1 mm higher (0.05 lower to 0.26 higher) | — | 148 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | |

| Change in BOP: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in BOP was 23% to 58% | MD 2.64% higher (8.81 lower to 14.09 higher) | — | 80 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BOP: bleeding on probing; CAL: clinical attachment level; CI: confidence interval; FMS: full‐mouth scaling; MD: mean difference; mm: millimetres; PPD: probing pocket depth; RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for risk of bias (three trials at high risk of detection bias and one at unknown risk of bias). bDowngraded one level for inconsistency ‐ some concern about unexplained heterogeneity. cDowngraded two levels for risk of bias (two trials at high risk of detection bias). dDowngraded one level for design limitations and imprecision.

1. Full‐mouth scaling versus control: change in probing pocket depth.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 6 (177) | –0.05 (–0.19, 0.09); P = 0.47 | P = 0.97; I² = 0% |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 7 (193) | –0.04 (–0.29, 0.21); P = 0.77 | P = 0.66; I² = 0% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (88) | –0.14 (–0.45, 0.18); P = 0.39 | P = 0.85; I² = 0% |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 4 (104) | –0.16 (–0.60, 0.28); P = 0.48 | P = 0.41; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 0.63 (0.29, 0.97); P = 0.0002 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (69) | 0.16 (–0.01, 0.32); P = 0.06 | P = 0.89; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (53) | 0.26 (–0.21, 0.73); P = 0.27 | P = 0.64; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 1.00 (0.41, 1.59); P = 0.0008 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (69) | 0.21 (–0.14, 0.55); P = 0.24 | P = 0.06; I² = 64% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (53) | 0.18 (–0.26, 0.62); P = 0.42 | P = 0.42; I² = 0% |

CI: confidence interval.

2. Full‐mouth scaling versus control: change in clinical attachment level.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 4 (111) | 0.02 (–0.19, 0.23); P = 0.85 | P = 0.90; I² = 0% |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 5 (127) | 0.09 (–0.22, 0.41); P = 0.57 | P = 1.00; I² = 0% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (89) | 0.22 (–0.05, 0.49); P = 0.11 | P = 0.87; I² = 0% |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 4 (105) | 0.05 (–0.64, 0.74); P = 0.89 | P = 0.005; I² = 77% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 0.41 (–0.00, 0.82); P = 0.05 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (40) | 0.04 (–0.19, 0.27); P = 0.71 | P = 0.50; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (24) | 0.47 (–0.37, 1.31); P = 0.27 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 1.11 (0.45, 1.77); P = 0.0009 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (40) | 0.00 (–0.34, 0.34); P = 1.00 | P = 0.19; I² = 41% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (24) | 0.38 (–0.28, 1.04); P = 0.26 | Not applicable |

CI: confidence interval.

3. Full‐mouth scaling versus control: change in bleeding on probing.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 3 (61) | –8.05 (–30.25, 14.16); P = 0.48 | P = 0.02; I² = 80% |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 4 (77) | –0.33 (–7.70, 7.04); P = 0.93 | P = 0.51; I² = 0% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 1 (20) | –6.10 (–24.12, 11.92); P = 0.51 | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (36) | 10.22 (–0.59, 21.03); P = 0.06 | P = 0.92; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 3.00 (–2.43, 8.43); P = 0.28 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (45) | –3.06 (–10.47, 4.35); P = 0.42 | P = 0.27; I² = 18% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (29) | –4.00 (–20.17, 12.17); P = 0.63 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 7.00 (4.54, 9.46); P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (45) | 2.38 (–2.95, 7.71); P = 0.38 | P = 0.50; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (29) | –4.00 (–23.29, 15.29); P = 0.68 | Not applicable |

CI: confidence interval.

Summary of findings 2. Full‐mouth disinfection compared to control for periodontitis in adults.

| FMD compared to control for periodontitis in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults with periodontitis Setting: university dental departments Intervention: FMD Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with FMD | |||||

| Tooth loss | None of the studies comparing FMD vs control reported tooth loss. | |||||

| Change in PPD: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in PPD was 0.26 mm to 1.54 mm | MD 0.11 mm higher (0.04 lower to 0.27 higher) | — | 214 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Similar results were found at 3–4 months. Subgroup analyses were undertaken for:

See Table 6; Table 7; Table 8. There was no consistent evidence of a benefit for FMD. |

| Change in CAL: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in CAL was 0.16 mm to 1.05 mm | MD 0.07 mm higher (0.11 lower to 0.24 higher) | — | 214 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | |

| Change in BOP: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in BOP was 3.11% to 49.18% | MD 9.54% higher (2.24 lower to 21.32 higher) | — | 92 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BOP: bleeding on probing; CAL: clinical attachment level; CI: confidence interval; FMD: full‐mouth disinfection; MD: mean difference; mm: millimetres; PPD: probing pocket depth; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias (two trials at high risk of detection bias and three trials at unknown risk of bias). bDowngraded one level for design limitations and imprecision. cDowngraded one level for inconsistency – some concern with unexplained heterogeneity. dDowngraded one level for risk of bias (one trial at high risk of detection bias and two at unknown risk of bias).

4. Full‐mouth disinfection versus control: change in probing pocket depth.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 2 (56) | 0.50 (–0.33, 1.33); P = 0.24 | P = 0.02; I² = 83% |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 3 (72) | 0.32 (–1.22, 1.85); P = 0.69 | P < 0.0001; I² = 91% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 1 (28) | 0.88 (0.20, 1.56); P = 0.01 | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (44) | –0.10 (–0.47, 0.26); P = 0.58 | P = 0.46; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 3 (50) | 0.28 (–0.59, 1.15); P = 0.52 | P = 0.0005; I² = 87% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 2 (34) | 1.28 (–0.48, 3.04); P = 0.15 | P = 0.03; I² = 78% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 5 (103) | 0.41 (0.11, 0.70); P = 0.006 | P = 0.01; I² = 70% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 4 (87) | 0.78 (–0.01, 1.57); P = 0.05 | P = 0.03; I² = 67% |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 3 (50) | 0.18 (–0.79, 1.15); P = 0.72 | P = 0.003; I² = 83% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 2 (34) | 1.28 (0.44, 2.11); P = 0.003 | P = 0.92; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 5 (103) | 0.21 (–0.12, 0.53); P = 0.21 | P = 0.03; I² = 62% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 4 (87) | 0.56 (–0.23, 1.34); P = 0.16 | P = 0.04; I² = 65% |

CI: confidence interval.

5. Full‐mouth disinfection versus control: change in clinical attachment level.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (28) | 0.18 (–0.21, 0.57); P = 0.37 | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 2 (44) | –0.39 (–1.32, 0.54); P = 0.42 | (P = 0.06); I² = 71% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (16) | –0.16 (–0.41, 0.09); P = 0.20 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 2 (40) | 0.08 (–0.87, 1.04); P = 0.86 | (P = 0.04); I² = 75% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 1 (24) | 1.90 (0.73, 3.07); P = 0.001 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (64) | 0.14 (0.00, 0.28); P = 0.05 | (P = 0.48); I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (48) | 0.72 (–0.94, 2.37); P = 0.40 | (P = 0.03); I² = 79% |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 2 (40) | 0.27 (–1.21, 1.75); P = 0.72 | (P = 0.001); I² = 90% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 1 (24) | 1.30 (0.20, 2.40); P = 0.02 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (64) | 0.12 (–0.17, 0.41); P = 0.43 | (P = 0.07); I² = 62% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (48) | 0.52 (–1.30, 2.34); P = 0.57 | (P = 0.005); I² = 87% |

CI: confidence interval.

6. Full‐mouth disinfection versus control: change in bleeding on probing.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | –5.00 (–11.70, 1.70); P = 0.14 | Not applicable |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (16) | 2.00 (–7.83, 11.83); P = 0.69 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 5.00 (1.97, 8.03); P = 0.001 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (45) | 4.83 (1.86, 7.80); P = 0.001 | P = 0.60; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (29) | 14.00 (–2.17, 30.17); P = 0.09 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (16) | 2.00 (0.38, 3.62); P = 0.02 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (45) | 8.72 (–2.61, 20.06); P = 0.13 | P = 0.22; I² = 34% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (29) | –8.00 (–25.00, 9.00); P = 0.36 | Not applicable |

CI: confidence interval.

Summary of findings 3. Full‐mouth scaling compared to full‐mouth disinfection for periodontitis in adults.

| FMS compared to FMD for periodontitis in adults | ||||||

| Population: adults with periodontitis Setting: university dental departments Intervention: FMS Comparison: FMD | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with FMD | Risk with FMS | |||||

| Tooth loss | None of the studies comparing FMS vs FMD reported tooth loss. | |||||

| Change in PPD: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in PPD was 0.57 mm to 1.73 mm | MD 0.11 mm lower (0.3 lower to 0.07 higher) | — | 112 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Similar results were found at 3–4 months. Subgroup analyses were undertaken for:

See Table 10; Table 11; Table 12. There was no consistent evidence of a benefit for either intervention. |

| Change in CAL: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in CAL was 0.43 mm to 1.07 mm | MD 0.05 mm lower (0.23 lower to 0.13 higher) | — | 112 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | |

| Change in BOP: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth Follow‐up: 6–8 months | The mean change in BOP was 23% to 56.4% | MD 0.2% lower (13.27 lower to 12.87 higher) | — | 42 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BOP: bleeding on probing; CAL: clinical attachment level; CI: confidence interval; FMD: full mouth disinfection; FMS: full mouth scaling; MD: mean difference; mm: millimetres; PPD: probing pocket depth; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for design limitations and imprecision. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias (two trials at high risk of detection bias and one trial at unknown risk of bias). cDowngraded one level for moderate imprecision. dDowngraded one level for risk of bias (one trial at unknown risk of detection bias).

7. Full‐mouth scaling versus full‐mouth disinfection: change in probing pocket depth.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 2 (57) | –0.52 (–1.34, 0.30); P = 0.22 | P = 0.01; I² = 84% |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 3 (75) | –0.05 (–1.84, 1.73); P = 0.95 | P < 0.00001; I² = 94% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 1 (30) | –0.88 (–1.53, –0.23); P = 0.008 | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (48) | –0.50 (–2.00, 0.99); P = 0.51 | P = 0.03; I² = 80% |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.25); P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (70) | –0.10 (–0.40, 0.20); P = 0.52 | P = 0.02; I² = 76% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (52) | –0.03 (–0.48, 0.41); P = 0.88 | P = 0.55; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 1.37 (0.81, 1.93); P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 3 (70) | 0.04 (–0.16, 0.25); P = 0.68 | P = 0.63; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 2 (52) | 0.05 (–0.38, 0.47); P = 0.83 | P = 0.29; I² = 9% |

CI: confidence interval.

8. Full‐mouth scaling versus full‐mouth disinfection: change in clinical attachment level.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (27) | –0.05 (–0.50, 0.40); P = 0.83 | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 2 (45) | 0.41 (–0.45, 1.27); P = 0.35 | P = 0.17; I² = 47% |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (18) | –0.51 (–1.24, 0.22); P = 0.17 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 0.71 (0.31, 1.11); P = 0.0005 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (42) | –0.09 (–0.30, 0.11); P = 0.38 | P = 0.44; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (24) | 0.56 (–0.37, 1.49); P = 0.24 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 1.53 (0.89, 2.17); P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (42) | –0.02 (–0.53, 0.49); P = 0.93 | P = 0.06; I² = 73% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (24) | 0.74 (0.17, 1.31); P = 0.01 | Not applicable |

CI: confidence interval.

9. Full‐mouth scaling versus full‐mouth disinfection: change in bleeding on probing.

| Tooth type: single‐ or multi‐rooted, or both | Baseline pocket depth (mm) | Time (months) | Number of studies (participants) | Mean difference (95% CI) (random‐effects meta‐analysis) | Heterogeneity |

| Both | 5–6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 7.00 (0.43, 13.57); P = 0.04 | Not applicable |

| Both | 5–6 | 6/8 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Both | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (18) | 8.00 (1.18, 14.82); P = 0.02 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 2.00 (–3.27, 7.27); P = 0.46 | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Single‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (46) | –6.69 (–12.18, –1.19); P = 0.02 | P = 0.45; I² = 0% |

| Single‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (28) | –18.00 (–30.83, –5.17); P = 0.006 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 3/4 | 1 (18) | 5.00 (2.93, 7.07); P < 0.00001 | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 3/4 | 0 (0) | Not estimable | Not applicable |

| Multi‐rooted | 5–6 | 6/8 | 2 (46) | –4.16 (–8.72, 0.39); P = 0.07 | P = 0.68; I² = 0% |

| Multi‐rooted | > 6 | 6/8 | 1 (28) | 4.00 (–13.37, 21.37); P = 0.65 | Not applicable |

CI: confidence interval.

Background

Description of the condition

Periodontitis is understood as a chronic multi‐factorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic dental plaque biofilm, affecting the tissues surrounding the teeth characterised by clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss, presence of periodontal pocketing and gingival bleeding (Papapanou 2018; Sanz 2020a). Some 10% to 12% of the population have severe periodontitis (Kassebaum 2017), though mild to moderate periodontitis affects the majority of adults (AAP 2005; Billings 2018; Oliver 1991).

Periodontitis is seen as resulting from a complex interplay of bacterial infection and host response, modified by behavioural and systemic risk factors (Papapanou 2018). In people with periodontitis, key pathogens such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia have been found to colonise nearly all niches in the oral cavity, such as the tongue, mucosa, saliva and tonsils (Beikler 2004). Translocation of these pathogens may occur rapidly and a recently instrumented deep pocket might be re‐colonised from remaining untreated pockets or from other intraoral niches before a less pathogenic ecosystem can be established.

Description of the intervention

Conventional treatment involves subgingival instrumentation, formerly known as scaling and root planing (SRP), which is performed at several appointments over a period of weeks. This is now understood as second step of periodontal therapy following step one (Sanz 2020a). The first step of therapy targets adequate self‐performed oral hygiene practices as well as a professional mechanical removal of supragingival plaque and calculus and elimination of local retentive factors (Sanz 2020a). There is considerable evidence to support SRP as an effective procedure for the treatment of infectious periodontal diseases (Heitz‐Mayfield 2002; Sanz 2020a; van der Weijden 2002), provided that the procedures included in the first step of therapy have been successfully implemented (Sanz 2020a). However, based on the risk of the recolonisation hypothesis, a full‐mouth disinfection (FMD) approach, which consists of SRP of all pockets in two visits within 24 hours, in combination with adjunctive chlorhexidine treatments of all oral niches, has been proposed (Quirynen 2006). This was first evaluated in a series of studies by the same research group (Bollen 1998; Mongardini 1999; Vandekerckhove 1996). A later report indicated that this full‐mouth treatment approach resulted in superior clinical outcomes and microbiological effects than conventional quadrant SRP (control), regardless of the adjunctive use of chlorhexidine (Quirynen 2000). However, more‐recent studies from other research centres have not been able to demonstrate an advantage of full‐mouth scaling (FMS) within 24 hours over the control regimen (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Babaloo 2018; Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Loggner Graff 2009; Pontillo 2018; Predin 2014; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010).

How the intervention might work

It is thought that the comprehensive reduction of bacteria from several oral niches by application of antiseptics within 24 hours will reduce the recolonisation of already treated sites leading to reductions of probing pocket depth (PPD) and bleeding on probing (BOP), and gains in clinical attachment.

Why it is important to do this review

This is the second update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2008 (Eberhard 2008a). Three systematic reviews were conducted to assess the evidence for full‐mouth treatment modalities (Eberhard 2008b; Farman 2008; Lang 2008). A review article was published by the advocates of the full‐mouth treatment concept (Teughels 2009), who disagreed with the results of these systematic reviews. Since then, more reviews have been published (Eberhard 2015; Fang 2016; Pockpa 2018; Suvan 2020; Zhao 2020). Our present systematic review is an update from 2015 (Eberhard 2015), and includes the most recent studies on this topic to ensure the evidence base for this important clinical question is up to date. The reason for the second update is the increased number of publications since 2015, more than doubling the number of included participants.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effects of full‐mouth scaling or full‐mouth disinfection (within 24 hours) for the treatment of periodontitis compared to conventional quadrant subgingival instrumentation (over a series of visits at least one week apart) and to evaluate whether there was a difference in clinical effects between full‐mouth disinfection and full‐mouth scaling.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with at least three months of follow‐up. We excluded trials with a split‐mouth or cross‐over design due to potential carryover effects.

Types of participants

Although the new classification of periodontal diseases no longer distinguishes between chronic or aggressive forms of periodontitis (Papapanou 2018), this will take some time to filter through to research studies, and so we retained our inclusion criteria of people with a clinical diagnosis of 'chronic periodontitis' based on the International Classification of Periodontal Diseases (Armitage 1999), and excluded studies of people with 'aggressive periodontitis'. We also excluded studies of participants with systemic disorders, and people taking antibiotics.

Types of interventions

Full‐mouth scaling (FMS), comprising subgingival instrumentation of all quadrants within 24 hours.

Full‐mouth disinfection (FMD), comprising subgingival instrumentation of all quadrants within 24 hours along with adjunctive antiseptic treatments (such as chlorhexidine), which could include rinsing, pocket irrigation, spraying of the tonsils and tongue brushing.

Quadrant subgingival instrumentation (SRP) (control), comprising SRP of each quadrant at a separate session, each session separated by an interval of at least one week.

The comparisons were: FMS versus control, FMD versus control and FMS versus FMD.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Tooth loss.

Change in probing pocket depth (PPD) after three to four months and six to eight months.

Secondary outcomes

Change in clinical attachment level (CAL) after three to four months and six to eight months.

Change in bleeding on probing (BOP) after three to four months and six to eight months.

Adverse events.

Pocket closure (number/proportion of sites with PPD of 4 mm or less after treatment).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (searched 17 June 2021) (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (searched 17 June 2021) (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 17 June 2021) (Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 17 June 2021) (Appendix 4);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 17 June 2021) (Appendix 5).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. A filter to limit the search to RCTs was not used as the yield was low.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trial registries for ongoing studies (see Appendix 6 for the search strategy):

US National Institutes of Health Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov) (to 17 June 2021);

World Health Organization Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.aspx) (to 17 June 2021).

Incomplete information and ambiguous data were researched further by contacting the author or researcher (or both) responsible for the study directly. For unpublished material, we searched the conference proceedings of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) up to June 2021. We sought relevant 'in press' manuscripts from the Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Journal of Periodontology, Journal of Dental Research and Journal of Periodontal Research and by contact with the journal editors.

We handsearched the following journals:

Journal of Periodontology (1980 to 17 June 2021);

Journal of Clinical Periodontology (1980 to 17 June 2021);

Journal of Periodontal Research (1980 to 17 June 2021).

We searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews for further studies.

We checked that none of the included studies in this review were retracted due to error or fraud.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used, we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts were downloaded to EndNote 9 software. The search was designed to be sensitive and include controlled clinical trials; these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. For this update, three review authors (PS, JE and SJ), independently and in duplicate, carried out the selection of papers and made decisions about eligibility. They resolved any disagreements by discussion. We recorded reasons for studies that were rejected at full‐text stage in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Four review authors (PS, HW, JE and SJ) extracted and entered data into a computer. Review authors who were authors on an included study did not extract data from that study. We extracted the following data.

General study characteristics: year of the study, country of origin, authors, funding, university/private practice based.

Specific trial characteristics: population, diagnosis of chronic periodontitis, gender, age, severity of periodontal disease, inclusion and exclusion criteria not already stated.

Primary outcomes: tooth loss, PPD (after three and six months if available, otherwise the nearest assessment time point evaluation).

Secondary outcomes: CAL and BOP before and after different treatment modalities (after three and six months if available, otherwise the nearest assessment time point evaluation), and adverse events.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (PS, HW and SJ) assessed the methodological quality of included studies mainly using the risk of bias components shown to affect study outcomes, including method of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of examiners. We also examined completeness of outcome reporting, selective outcome reporting and other potential threats to validity. Risk of bias was used in sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the conclusions but was not used to exclude studies qualifying for the review. We used the definitions of risk of bias (RoB 1 tool) categories from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 7). Review authors who were authors on an included study did not assess the risk of bias for that study.

To examine overall risk of bias for each study, we used all the domains of risk of bias. If all domains were at low risk, the study was deemed at low risk of bias. If any domains had an unclear risk, then the study was classed as having an unclear risk of bias; however, if one or more domains was assessed at a high risk of bias, then so was the study. We did not score performance bias of the operator as it is impossible to blind the therapist as they perform quadrant‐wise or full‐mouth instrumentation.

Measures of treatment effect

We used change scores for the secondary outcomes as this is how the data were generally presented in these trials. If studies presented only post‐scores or covariance adjusted means, we included these and conducted a subgroup analysis for the different outcome measures. For continuous outcomes, we used mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to summarise the data for each group. For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed the estimates of effect of an intervention as risk ratios with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

Whole‐mouth, single‐rooted teeth and multi‐rooted teeth outcomes were the basis for data analysis, and we calculated means for all the primary and secondary outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

We calculated missing standard deviations using the methods in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Prior to each meta‐analysis, we assessed heterogeneity by inspection of a graphical display of the estimated treatment effects from trials, along with Cochran's test for heterogeneity, and I² statistics.

Assessment of reporting biases

We considered the different types of reporting bias that might have been present in this review. If there had been more than 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis, we would have created a funnel plot to detect possible publication bias, although an asymmetrical funnel plot may be due to other factors. However, no single comparison of the present review included more than 10 studies.

Data synthesis

Where there were studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures, we performed a meta‐analysis. We combined risk ratios for dichotomous data, and MDs for continuous data, using the random‐effects model.

We categorised teeth into the following groups for the meta‐analysis, as these categories are thought to have clinical relevance: whole mouth (all teeth), teeth that had moderate pocket depth at baseline and teeth that had deep pocket depth at baseline. These analyses were repeated for single‐rooted and multi‐rooted teeth separately for all outcomes, and for two outcome assessment times: three to four months and six to eight months after treatment. Based on current treatment concepts, we categorised the pocket depth of 4 mm to 6 mm as moderate and 7 mm or more as deep. This is described in more detail for each study in the Results section.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for different outcome measures (post‐treatment, change, covariance adjusted). The following factors were recorded to assess the clinical heterogeneity of outcomes across studies.

Plaque levels.

Time allowed for treatment.

Age of participants.

Initial probing depth.

Smoking status.

Risk of bias.

There were insufficient studies in any one comparison to use subgroup analyses to investigate any clinical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses by analysing only studies assessed at low risk of bias. We had also planned, if appropriate, to conduct sensitivity analyses by excluding unpublished literature.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We summarised the findings of the main comparisons and outcomes in summary of findings tables. These included:

Tooth loss.

Change in PPD.

Change in CAL.

Change in BOP.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence, using GRADE criteria, as high, moderate, low or very low, explaining rationale for our judgements in footnotes. We assessed the GRADE domains using GRADEpro GDT (Schünemann 2020). We assessed the following domains.

Study design: any limitations in design or execution of the study.

Inconsistency: unexplained heterogeneity of the results.

Indirectness: indirect comparisons or differences in participants, interventions or outcomes of interest.

Imprecision: studies including small numbers of participants with wide CIs.

Publication bias: we had planned to assess this using funnel plots.

To make our decisions about the certainty of the evidence, we followed the same guideline as in the first update of this review in 2015 (Schünemann 2011), but used data from six to eight months of follow‐up for the summary of findings tables rather than data from three to four months (see Differences between protocol and review).

Results

Description of studies

Our original review, Eberhard 2008a, included seven studies (Apatzidou 2004; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006). In our first update, which was published in 2015 (Eberhard 2015), we added another five studies (Del Peloso 2008; Knöfler 2007; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Zijnge 2010). In the present (second) update, we reconsidered these studies and determined that one should be excluded (Knöfler 2007). We included nine new studies from the updated searches (Afacan 2020; Babaloo 2018; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Pontillo 2018; Predin 2014; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015).

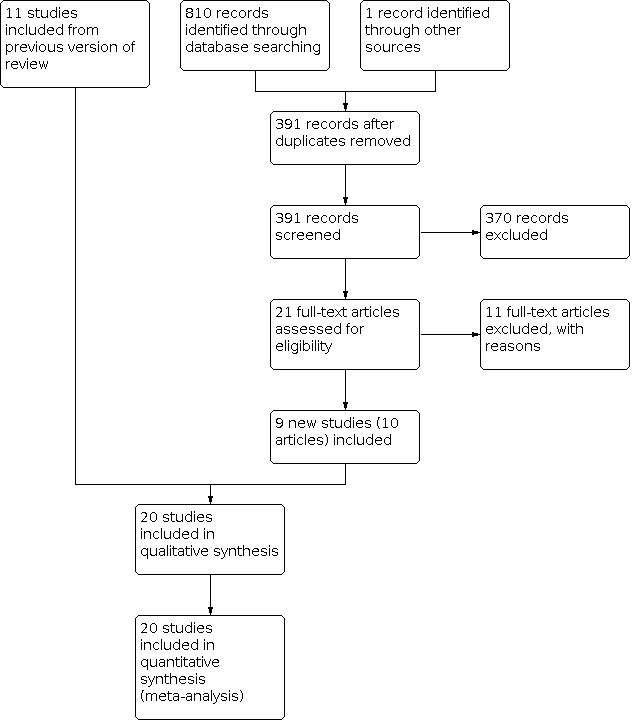

Results of the search

For this review update, we screened 391 titles and abstracts and rejected 370. We obtained the full text for 21 potentially eligible articles. Of these, we excluded 11 articles (10 studies). In addition, we excluded one article formerly awaiting assessment (Zhao 2005) and one formerly included RCT (Knöfler 2007); see information above under Description of studies. Therefore, in total, the review includes 20 trials reported in 23 articles (Mongardini 1999 was reported in three articles and Babaloo 2018 was reported in two). The 20 included trials are: Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Babaloo 2018; Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010. See Figure 1 for a diagrammatic representation of the selection of included studies.

1.

Study flow chart.

Included studies

Design

The 20 included studies were all parallel‐group RCTs of between three and 12 months' duration. Most studies had two or three arms. One paper relating to Mongardini 1999 referred to an FMS group ('FRp group') that was not randomised and so was not part of the review. In addition, four studies involved randomised arms that we did not include: Fonseca 2015 (one FMD arm using an alternative protocol and two SRP arms that included antiseptics); Pontillo 2018 (one control arm that consisted of people without periodontitis); Quirynen 2000 (two FMD arms using alternative antiseptic protocols); and Soares 2015 (one FMD arm and one SRP arm that included tongue scraping as part of the intervention).

Setting

Ten studies were conducted in Europe; seven in Brazil; and one each in Japan (Koshy 2005), Iran (Babaloo 2018), and Turkey (Afacan 2020).

Participants

In total, the 20 studies included 944 adults with periodontitis. Participants were aged 23 to 77 years (one study did not specify the age range (Graziani 2015)). Seven studies involved only non‐smokers (Afacan 2020; Del Peloso 2008; Koshy 2005; Pontillo 2018; Roman‐Torres 2018; Soares 2015; Zijnge 2010); 10 studies involved a mix of smokers and non‐smokers, and three studies were unclear about smoking status (Babaloo 2018; Santuchi 2015; Zanatta 2006). The number of participants enrolled in the included studies ranged from 10 to 230. Eleven trials had no dropouts and the other trials had dropouts ranging from 2% to 17%.

Interventions

Six studies included more than one comparison. The comparisons included in the trials were:

FMS versus control (13 trials): Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010;

FMD versus control (13 trials): Afacan 2020; Babaloo 2018; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018; Quirynen 2006; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Zanatta 2006;

FMS versus FMD (six trials): Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Zanatta 2006.

Outcomes

Nineteen studies provided whole‐mouth data, with one study only providing partial‐mouth scores (Quirynen 2006).

None of the studies provided information on the primary outcome 'tooth loss'.

Thirteen studies provided full information on the primary outcome 'change in PPD', as well as on the secondary outcomes 'change in attachment loss' (CAL) and 'change in BOP'. Five studies reported only PPD and CAL (Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Predin 2014; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015). One study reported only PPD and BOP (Zijnge 2010); and one study reported only PPD (Vandekerckhove 1996). All studies provided change scores and we were able to use these in all analyses.

Eleven studies provided data for the comparison of single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth between FMS and control three or four (in the following, designated as 3/4) months after baseline (Afacan 2020; Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010). Seven studies provided these data after six or eight (in the following, designated as 6/8) months (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Fonseca 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009). Two studies performed retreatment after three months (Del Peloso 2008; Wennström 2005). These two studies were included in the meta‐analysis, but only data measured before retreatment were used for the comparisons.

Ten studies provided data for the comparison between FMD and control 3/4 months after baseline (Afacan 2020; Babaloo 2018; Fonseca 2015; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Roman‐Torres 2018; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Zanatta 2006); nine studies showed such data after 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018; Quirynen 2006; Santuchi 2015; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996). Six studies compared the three different treatment modalities after 3/4 and 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Zanatta 2006). Five studies separated the data into the subcategories 'single‐rooted' or 'multi‐rooted' teeth in terms of PPD (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996).

With regard to 'moderate' pocket depth, two studies defined this as 4 mm to 5.5 mm (Fonseca 2015; Quirynen 2006); two studies defined it as 4 mm to 6 mm (Swierkot 2009; Zijnge 2010); one study defined it as 6 mm or less (Del Peloso 2008); while seven studies classified pocket depths of 5 mm to 6 mm as moderate (Apatzidou 2004; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Vandekerckhove 1996; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006). Ten studies defined 'deep' pockets as being 7 mm or more (Apatzidou 2004; Del Peloso 2008; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010), and two studies defined deep pockets as 6 mm or deeper (Fonseca 2015; Quirynen 2006). Three studies provided data from the first quadrant only (Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Vandekerckhove 1996); the other studies generated the data from the whole mouth (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Babaloo 2018; Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Pontillo 2018; Predin 2014; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006; Zijnge 2010).

Excluded studies

We excluded 22 studies for the reasons below (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

Type of disease (aggressive periodontitis, data not split regarding classification of periodontitis) (Bollen 1998).

Results of subgroups for QRP (quadrant‐wise subgingival SRP) (with and without use of chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX)) and FMS (with and without use of CHX) were not split into subgroups. The clinical data of QRP and FMS were presented as two groups only (Cortelli 2015).

Intervention after 24 hours (Eren 2002).

No control group (Jothi 2009).

No randomisation (Lee 2009).

Retreatment of participants prior to outcome assessment at six months (Loggner Graff 2009).

Data only available as figures; no reply from authors to request for supplemental data (Meulman 2013).

Participants in all arms received azithromycin (Oliveira 2019).

Participants in all arms received chlorhexidine rinse (Knöfler 2007; Preus 2013; Preus 2015a; Preus 2015b; Preus 2017a; Preus 2017b) or chlorhexidine gel (Silveira 2017).

Commentary on Preus 2013; Preus 2015a; Preus 2017a; Preus 2017b (Devji 2017).

Length of follow‐up was less than three months (Quirynen 1995; Serrano 2011).

Same group as presented in Santuchi 2015, but outcomes presented insufficiently (Santuchi 2016).

Several retreatments prior to outcome assessment at 18 months (Tomasi 2006).

Immunological study, lack of clinical data (Ushida 2008).

Still preliminary results only; was awaiting classification in 2015 version of this review (Zhao 2005).

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall risk of bias

Based on all domains, we assessed five studies at high risk of bias (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996), and six at low risk of bias (Del Peloso 2008; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Wennström 2005; Zijnge 2010), with the remaining nine being at unclear risk of bias. The risk of bias for each domain for each study is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Overall, we assessed 11 studies at low risk of selection bias (Del Peloso 2008; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Santuchi 2015; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zijnge 2010).

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Eleven trials described the method of randomisation, which was performed using a computer (Afacan 2020; Del Peloso 2008; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Wennström 2005; Zijnge 2010) or sealed numbered envelopes (Fonseca 2015; Santuchi 2015). In three trials, the method of randomisation was a coin toss (Babaloo 2018; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009). In six trials, the method of randomisation was uncertain or not stated (Apatzidou 2004; Pontillo 2018; Roman‐Torres 2018; Soares 2015; Vandekerckhove 1996; Zanatta 2006).

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Five trials performed concealment using sealed opaque envelopes (Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Koshy 2005; Santuchi 2015; Wennström 2005). Six trials provided adequate information about allocation concealment (Del Peloso 2008; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Zijnge 2010). In four studies, the concealment was unclear (Roman‐Torres 2018; Soares 2015; Vandekerckhove 1996; Zanatta 2006). The remaining five trials gave no comments about concealment (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Babaloo 2018; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018).

Blinding

We did not score performance bias of the operator as it was impossible to blind the therapist as they perform quadrant‐wise or full‐mouth instrumentation.

Thirteen trials blinded the outcome assessor to the treatment groups. Two trials gave no information about blinding and were at unclear risk of detection bias (Roman‐Torres 2018; Soares 2015), and five trials did not blind the outcome assessor (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996).

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen studies adequately described the completeness of follow‐up (the number of participants who entered the study and subsequently finished it) (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Del Peloso 2008; Graziani 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996; Wennström 2005; Zijnge 2010). Five studies did not describe timing or reason for dropout, which we judged at unclear risk of attrition bias (Fonseca 2015; Predin 2014; Quirynen 2006; Soares 2015; Zanatta 2006). We also judged Babaloo 2018 as unclear because, although the study implied all participants were included in follow‐up assessments, it did not explicitly state this.

Selective reporting

Outcome reporting bias

All studies reported their data on all primary and secondary outcomes.

Publication bias

We did not assess publication bias using funnel plots as the comparisons included fewer than 10 studies with data at 6/8 months. Due to the small number of studies in each comparison, publication bias was difficult to assess.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged 15 studies at low risk of any other potential biases. Five studies were unclear: the baseline balance for smoking was unclear in four studies (Babaloo 2018; Fonseca 2015; Santuchi 2015; Zanatta 2006), and there was insufficient information to make a judgement about other potential risks of bias in one study (Roman‐Torres 2018).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 5; Table 9

It must be stated that studies defined whole‐mouth evaluation differently. Fourteen studies carried out evaluation on all pockets (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Babaloo 2018; Fonseca 2015; Graziani 2015; Koshy 2005; Pontillo 2018; Predin 2014; Roman‐Torres 2018; Santuchi 2015; Soares 2015; Swierkot 2009; Wennström 2005; Zanatta 2006); one study evaluated only pockets initially greater than 3 mm (Zijnge 2010); one study evaluated only pockets initially greater than 5 mm (Jervøe‐Storm 2006); one study presented only results in the subcategories initially moderate or deep pockets (Del Peloso 2008); one study only reported results in the subcategories single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth (Quirynen 2006); and two studies evaluated only pockets of the upper right quadrant (Mongardini 1999; Vandekerckhove 1996).

Full‐mouth scaling versus control

The results for evaluations at 6/8 months are reported below and summarised in Table 1. Results for evaluations at 3/4 months are found in Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; and Analysis 1.3.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Full‐mouth scaling (FMS) versus control, Outcome 1: Change in probing pocket depth: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Full‐mouth scaling (FMS) versus control, Outcome 2: Change in clinical attachment level: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Full‐mouth scaling (FMS) versus control, Outcome 3: Change in bleeding on probing: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

Tooth loss

None of the studies comparing FMS versus control reported tooth loss.

Change in probing pocket depth

Whole‐mouth data on PPD are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 1.1).

Five studies (three at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) compared whole‐mouth scores in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMS, when compared with control, results in little to no difference in change in PPD for whole‐mouth scores (MD 0.03 mm, 95% CI –0.14 to 0.20; P = 0.70; Chi² = 2.56, 4 degrees of freedom (df), P for heterogeneity (Phet) = 0.63, I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence).

Sensitivity analysis for probing pocket depth

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken for low risk trials only for PPD at 6/8 months; the MD was 0.24 mm (95% CI –0.09 to 0.57; heterogeneity not applicable, Koshy 2005), which is consistent with the overall finding of no evidence of a difference.

Change in clinical attachment level

Whole‐mouth data on CAL are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 1.2).

We included five studies (three at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis for whole‐mouth scores in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Apatzidou 2004; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in CAL when compared with control for whole‐mouth data comparisons (MD 0.10 mm, 95% CI –0.05 to 0.26; P = 0.18; Chi² = 3.78, 4 df, Phet = 0.44, I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). There was no evidence of heterogeneity for whole‐mouth recordings.

Change in bleeding on probing

Whole‐mouth data on BOP are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 1.3).

We included three studies (two at high and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis after 6/8 months for single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth combined (Apatzidou 2004; Koshy 2005; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in BOP when compared with control for the whole‐mouth evaluation (MD 2.64%, 95% CI –8.81 to 14.09; P = 0.65; Chi² = 3.97, 2 df, Phet = 0.14, I² = 50%; very‐low‐certainty evidence). There was some evidence of heterogeneity for whole‐mouth recording.

Subgroup analyses full‐mouth scaling versus control

Results for 3/4‐months subgroup analyses are found in Table 2; Table 3; and Table 4.

Change in probing pocket depth

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

We included four studies (two at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis for moderate (Apatzidou 2004; Fonseca 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006) and deep pockets (Apatzidou 2004; Fonseca 2015; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Swierkot 2009) in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Table 2). The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in PPD when compared with control for moderate pockets (5 mm to 6 mm) (MD –0.14 mm, 95% CI –0.45 to 0.18; P = 0.39; Chi² = 0.33, 2 df, Phet = 0.85, I² = 0%). The same applied for the deep pockets (greater than 6 mm) (MD –0.16 mm, 95% CI –0.60 to 0.28; P = 0.48; Chi² = 2.91, 3 df, Phet = 0.41, I² = 0%).

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

We included three studies (one at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis for single‐rooted teeth alone after 6/8 months. The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in PPD when compared with control for moderate (MD 0.16 mm, 95% CI –0.01 to 0.32; P = 0.06; Chi² = 0.24, 2 df, Phet = 0.89, I² = 0%; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009) or deep pockets in single‐rooted teeth (MD 0.26 mm, 95% CI –0.21 to 0.73; P = 0.27; Chi² = 0.21, 1 df, Phet = 0.64, I² = 0%; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006).

The same three studies (one at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) were included in the meta‐analysis for multi‐rooted teeth alone after 6/8 months. The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in PPD when compared with control for moderate (MD 0.21 mm, 95% CI –0.14 to 0.55; P = 0.24; Chi² = 5.60, 2 df, Phet = 0.06, I² = 64%; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009) or deep pockets in multi‐rooted teeth (MD 0.18 mm, 95% CI –0.26 mm to 0.62 mm; P = 0.42; Chi² = 0.65, 1 df, Phet = 0.42, I² = 0%; Koshy 2005; Quirynen 2006).

Change in clinical attachment level

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

We included four studies in the meta‐analysis for moderate and deep pockets in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth (Apatzidou 2004; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009) after 6/8 months. The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in CAL when compared with control for moderate (MD 0.22 mm, 95% CI –0.05 to 0.49; P = 0.11; Chi² = 0.29, 2 df, Phet = 0.87, I² = 0%; Apatzidou 2004; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Quirynen 2006) or deep pockets (MD 0.05 mm, 95% CI –0.64 to 0.74; P = 0.89; Chi² = 12.89, 3 df, Phet = 0.005, I² = 77%; Apatzidou 2004; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009). There was no evidence of heterogeneity for moderate pockets, but evidence of substantial heterogeneity for deep pockets (Table 3).

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

Only two studies (one at high and one at low risk of bias) provided data after 6/8 months for single‐rooted or multi‐rooted teeth alone (Koshy 2005; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in CAL when compared with control for moderate pockets in single‐rooted (MD 0.04 mm, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.27; P = 0.71; Chi² = 0.46, 1 df, Phet = 0.50, I² = 0%) and multi‐rooted teeth (MD 0.00 mm, 95% CI –0.34 to 0.34; P = 1.00; Chi² = 1.71, 1 df, Phet = 0.19, I² = 41%) as for deep pockets in single‐ (MD 0.47 mm, 95% CI –0.37 to 1.31; P = 0.27; heterogeneity not applicable) and multi‐rooted teeth (MD 0.38 mm, 95% CI –0.28 to 1.04; P = 0.26; heterogeneity not applicable) (Table 3).

Change in bleeding on probing

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

The evidence suggests that at 6/8 months FMS results in little to no difference in change in BOP when compared with control for moderate (MD –6.10%, 95% CI –24.12 to 11.92; P = 0.51; heterogeneity not applicable; Jervøe‐Storm 2006) or for deep pockets (MD 10.22%, 95% CI –0.59 to 21.03; P = 0.06; Chi² = 0.01, 1 df, Phet = 0.92, I² = 0%; Jervøe‐Storm 2006; Swierkot 2009). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (Table 4).

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

Only two studies (with high and unclear risk of bias) provided data at 6/8 months for single‐rooted alone and multi‐rooted teeth alone (Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMS results in little to no difference in change in BOP after 6/8 months when compared with control for moderate pockets (single‐rooted: MD –3.06%, 95% CI –10.47 to 4.35; P = 0.42; Chi² = 1.22, Phet = 0.27, I² = 18%; multi‐rooted: MD 2.38%, 95% CI –2.95 to 7.71; P = 0.38; Chi² = 0.45, 1 df, Phet = 0.50, I² = 0%; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009), or deep pockets (single‐rooted: MD ‐4.00%, 95% CI –20.17 to 12.17; P = 0.63; heterogeneity not applicable; multi‐rooted: MD ‐4.00%, 95% CI –23.29 to 15.29; P = 0.68; heterogeneity not applicable; Quirynen 2006) (Table 4).

Full‐mouth disinfection versus control

The results are summarised in Table 5. Results for 3/4‐month evaluation are found in Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; and Analysis 2.3.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Full‐mouth disinfection (FMD) versus control, Outcome 1: Change in probing pocket depth: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Full‐mouth disinfection (FMD) versus control, Outcome 2: Change in clinical attachment level: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Full‐mouth disinfection (FMD) versus control, Outcome 3: Change in bleeding on probing: whole mouth, single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

Tooth loss

None of the studies comparing FMD versus control reported tooth loss.

Change in probing pocket depth

Whole‐mouth data are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 2.1).

Six studies (two at high, three at unclear and one at low risk of bias) compared whole‐mouth scores in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Pontillo 2018; Santuchi 2015; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMD when compared with control results in little to no difference in change in PPD for whole‐mouth scores (MD 0.11 mm, 95% CI –0.04 to 0.27; P = 0.14; Chi² = 2.68, 5 df, Phet = 0.75, I² = 0%).

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook a sensitivity analysis for low risk of bias trials only for change in PPD at 6/8 months. The MD was 0.23 mm (95% CI –0.15 to 0.61; heterogeneity not applicable, Koshy 2005), which is consistent with the overall finding of no evidence of a difference.

Change in clinical attachment level

Whole‐mouth for 6/8‐month comparisons are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 2.2).

We included six studies (two at high, three at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis for whole‐mouth scores in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Afacan 2020; Fonseca 2015; Koshy 2005; Pontillo 2018; Santuchi 2015; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMD when compared with control results in little to no difference in change in CAL for whole‐mouth scores (MD 0.07 mm 95% CI –0.11 to 0.24; P = 0.47; Chi² = 1.14, 5 df, Phet = 0.95, I² = 0%). There was no evidence of heterogeneity.

Change in bleeding on probing

Whole‐mouth data for 6/8‐month comparisons are shown in a forest plot (Analysis 2.3).

We included four studies (two at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis after 6/8 months for single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth combined (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Pontillo 2018; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMD results in little to no difference in change in BOP for whole‐mouth scores when compared with control (MD 9.54%, 95% CI –2.24 to 21.32; P = 0.11; Chi² = 14.68, 3 df, Phet = 0.002, I² = 80%). There was evidence of considerable heterogeneity for the whole‐mouth findings.

Subgroup analyses full‐mouth disinfection versus control

Results for 3/4‐month subgroup analyses are found in Table 6; Table 7; and Table 8.

Change in probing pocket depth

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

Only two studies at unclear and high risk of bias were included for moderate and deep pockets in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth after 6/8 months (Fonseca 2015; Swierkot 2009; Table 6). The evidence suggests FMD reduces PPD more than control for moderate pockets (MD 0.88 mm, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.56; P = 0.01; heterogeneity not applicable; Fonseca 2015). The evidence suggests that FMD results in little to no difference in change in PPD when compared with control for deep pockets (MD –0.10 mm, 95% CI –0.47 to 0.26; P = 0.58; Chi² = 0.56, 1 df, Phet = 0.46, I² = 0%; Fonseca 2015; Swierkot 2009). The outcome for moderate pockets was based on one trial with unclear risk of bias and the numbers of participants were low (18).

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

We included five studies (three at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis after 6/8 months for single‐rooted teeth alone (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996). The evidence suggests FMD reduces PPD more than control for moderate (MD 0.41 mm, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.70; P = 0.006; Chi² = 13.13, 4 df, Phet = 0.01, I² = 70%; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996) and deep pockets (MD 0.78 mm, 95% CI –0.01 to 1.57; P = 0.05; Chi² = 9.41, 3 df, Phet = 0.03, I² = 67%; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Vandekerckhove 1996). However, there was substantial heterogeneity for both analyses. Three studies for these analyses had a high risk of detection bias. In all three studies, the same person performed treatment and assessment. One study had unclear risk of bias because the rate of dropouts was 15.7%.

We included five studies (three at high, one at unclear and one at low risk of bias) in the meta‐analysis for multi‐rooted teeth alone after 6/8 months (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009; Vandekerckhove 1996). The evidence suggests that FMD results in little to no difference in change in PPD when compared with control for moderate (MD 0.21 mm, 95% CI –0.12 to 0.53; P = 0.21; Chi² = 10.56, 4 df, Phet = 0.03, I² = 62%) or deep pockets (MD 0.56 mm, 95% CI –0.23 to 1.34; P = 0.16; Chi² = 8.52, 3 df, Phet = 0.04, I² = 65%). There was evidence of substantial heterogeneity for both comparisons.

Change in clinical attachment level

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

No studies provided data for moderate pockets after 6/8 months. Only one study reported data for deep pockets in single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth (Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMD results in little to no difference in change in CAL when compared with control for deep pockets without evidence of heterogeneity (MD –0.16 mm, 95% CI –0.41 to 0.09; P = 0.20; heterogeneity not applicable; Table 7). However, this outcome was generated from one study at high risk of bias. The concern was about blinding of assessment of data, as the same person performed treatment and assessment. Additionally, data were generated in 16 participants (FMD: nine; control: seven), reaching a difference of 0.16 mm, which is unlikely to be clinically relevant.

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

Three studies (two at high and one at low risk of bias) provided data after 6/8 months for single‐rooted teeth alone (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests FMD may result in a small difference in CAL compared with control for moderate pockets (MD 0.14 mm; 95% CI 0.00 to 0.28; P = 0.05; Chi² = 1.45, 2 df, Phet = 0.48, I² = 0%). For deep pockets, the MD was 0.72 mm (95% CI –0.94 to 2.37; P = 0.40; Chi² = 4.66, 1 df, Phet = 0.03, I² = 79%) with considerable heterogeneity. Outcomes were based on three trials, two with high risk of bias. The concerns for both high‐risk studies were blinding of assessment of data, as the same person performed treatment and assessment. Additionally, the difference, based on the comparison of 55 participants versus 57 participants, between the two treatment modalities was 0.14 mm, which is unlikely to be clinically relevant.

Three studies (two at high and one at low risk of bias) provided data after 6/8 months for multi‐rooted teeth (Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009). The evidence suggests that FMD results in little to no difference in change in CAL when compared with control for moderate (MD 0.12 mm, 95% CI –0.17 to 0.41; P = 0.43; Chi² = 5.32, 2 df, Phet 0.07, I² = 62%; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999; Swierkot 2009) or deep pockets (MD 0.52 mm, 95% CI –1.30 to 2.34; P = 0.57; Chi² = 7.79, 1 df, Phet = 0.005, I² = 87%; Koshy 2005; Mongardini 1999), both with evidence of considerable heterogeneity.

Change in bleeding on probing

Single‐ and multi‐rooted teeth

There were no data for moderate pockets. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of FMD at 6/8 months for deep pockets (MD 2.00%, 95% CI –7.83 to 11.83; P = 0.69; heterogeneity not applicable). However, this outcome was generated from one study at high risk of bias (Swierkot 2009). The concern was about blinding of assessment of data, as the same person performed treatment and assessment. Additionally, the difference of 2% is not clinically relevant and the level of evidence for BOP was very low.

Single‐ or multi‐rooted teeth

Two studies (one at high and one at unclear risk of bias) provided data after 6/8 months for single‐rooted teeth (Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009). FMD reduced BOP slightly compared with control (MD 4.83%, 95% CI 1.86 to 7.80; P = 0.001; Chi² = 0.28, 1 df, Phet = 0.60, I² = 0%). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of FMD in deep pockets at 6/8 months (MD 14.00%, 95% CI –2.17 to 30.17; P = 0.09; heterogeneity not applicable; Quirynen 2006). A difference in BOP of 4.83% or 14% is probably not clinically relevant. The results must be seen in the context of the risk of bias assessed for both studies. One study had concerns with detection blinding; the other with the rate of dropouts (15.7%). Reasons and time point for dropouts were unclear and not declared. The level of evidence for BOP was very low certainty.

Two studies (one at high and one at unclear risk of bias) provided data after 6/8 months for multi‐rooted teeth (Quirynen 2006; Swierkot 2009). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of FMD at 6/8 months for moderate pockets (MD 8.72%, 95% CI –2.61 to 20.06; P = 0.13; Chi² = 1.52, 1 df, Phet = 0.22, I² = 34%) or deep pockets (MD –8.00%, 95% CI –25.00 to 9.00; P = 0.36; heterogeneity not applicable; Quirynen 2006). There was evidence of moderate heterogeneity for moderate pockets.